#antoine de baecque

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

From Jean-Luc Godard’s Archive What We Leave Behind Photographs by Stéphan Crasneanscki

Foreword by Patti Smith Conversation with Abel Ferrara Essay by Antoine de Baecque

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Random question, but has anyone read renaissance man Antoine de Baecque’s vampire novel set in the FR, Les Talons Rouges? If it’s as good as his history…

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mais d’où vient ce regard, cette intensité frontale ? De l'Histoire, directement […] C'est l'Histoire du siècle qui a inventé le cinéma moderne.

>>>Alfred Hitchcock, Under Capricorn, 1949; Roberto Rossellini - Europa '51, 1952; Antoine de Baecque - "Des femmes qui nous regarden", Cahiers du cinéma n° 26 Hors série, novembre 2000<<<

**Expanded Version**

1 note

·

View note

Video

vimeo

Salon international du livre de montagne de Passy - rencontre littéraire du 22 07 2023 from Godefroy de MAUPEOU on Vimeo.

Rencontre littéraire au Jardin des Cimes le 22 07 2023 Avec Antoine de Baecque, Anne Barrioz, Guillaume Desmurs, Patrick Ollivier-Eliott, Pierre-Louis Roy Un partage d’expériences sur la vie des vallées alpines et l’avenir de leurs équipements.

0 notes

Text

Book Recommendations on the French Revolution (the "short" list version)

(For some reason, the original anonymous ask and answer I thought I had saved in my drafts has disappeared? Did I accidentally delete it? Who knows with Tumblr. Anyway, good thing I screenshotted it, I guess.)

Since I am STILL working on my extremely long post series going in depth into recommendations, I guess I should really just answer this ask and give a plain and simple list, as it was requested -_- (Don't worry, the extremely long post series is still going to happen.)

First of all, let’s just say, again (and it really must be insisted on), that most Anglophone historiography is… not very good. There are exceptions, but not many. At least, not enough to satisfy me. Fortunately, some good French books have been translated to English – so that’s great news!

So here are my main recommendations:

Sophie Wahnich’s La liberté ou la mort. Essai sur la Terreur et le terrorisme (2003) which was translated to In Defence of the Terror: Liberty Or Death in the French Revolution with a foreword by Slavoj Zizek in 2012.

This essay basically changed my life, and led me to take the path I have walked since as a historian. Zizek’s foreword is very good in summarizing the ideological oppositions to the French Revolution (until he rambles the way he usually does).

It opens with a quote from Résistant poet René Char which perfectly sets the tone:

“I want never to forget how I was forced to become – for how long? – a monster of justice and intolerance, a narrow-minded simplifier, an arctic character uninterested in anyone who was not in league with him to kill the dogs of hell.”

Keep in mind that when I first read it, in 2003, the very notion of anything like the Charlottesville rally happening was still in the realm of pure fantasy.

Marie-Hélène Huet’s Mourning Glory: The Will of the French Revolution (1997). One of the rare books in my list that was originally written in English (!). I think a lot of it might be available to read via Google Books, but it’s worth buying.

This book is hard to categorize: it talks of historiography and ideology, and it’s overall a fascinating book.

It feels a lot like Sophie Wahnich’s first essay – it was also similarly influential on my research. It inspired a lot of my M.A. thesis. I’ve recently found my book version of it, and this book was annotated like I’ve rarely annotated a book. It was quite impressive.

Dominique Godineau’s Citoyennes Tricoteuses: Les femmes du peuple à Paris pendant la Révolution française (1988) which was translated to The Women of Paris and Their French Revolution (1998).

It’s the best book on women’s history during the French Revolution IMO. I really don’t have much more to say about it: it’s excellent. It talks of working class women, it talks of the conflicts between different women groups, it talks of what happened after Thermidor and the Prairial insurrections, and the women who were arrested. No book has compared to it yet.

Jean-Pierre Gross’s Fair Shares for All: Jacobin Egalitarianism in Practice (1997). You can download it for free via The Charnel House (link opens as pdf).

Another rare book that was originally written in English, and later translated to French, though the author is French! (I think some French authors have picked up that the real battlefield is in Anglophonia…) It’s very important to understand social rights, a founding legacy of the French Revolution.

François Gendron’s essential book on the Thermidorian Reaction: first published in Québec as La jeunesse dorée. Episodes de la Révolution française (1979) (The Gilded Youth. Episodes of the French Revolution). It was then published in France as La jeunesse sous Thermidor (The Youth During Thermidor). As I explained here, its publication history is quite controversial (though it seems no one noticed?). It was thankfully translated to English as The Gilded Youth of Thermidor (1993). However, the English translation follows Pierre Chaunu’s version – which didn’t alter the content per se, but removed the footnotes and has a terribly reactionary foreword – so be careful with that. If anything, that’s a very good example of all the problems in historiography and translations.

Much like Godineau’s book on women, no book can compare. In the case of women’s history during the French Revolution, it’s because most of it is abysmally terrible; in the case of the Thermidorian reaction, it’s because no one talks about it. And it’s not surprising once you start reading about it.

(You might notice that Gendron’s translated book, much like many others, are prohibitively expensive. I do own some of these so if you ever want to read any, send me a message and we’ll work it out!)

Antoine de Baecque’s The Body Politic. Corporeal Metaphor in Revolutionary France, 1770-1800 (1997), which is a translation of Le Corps de l’histoire : Métaphores et politique (1770-1800) (1993). (Here’s the table of contents.) It’s a peculiar book belonging to a peculiar field, and it can be a bit complicated/advanced in the same way most of Sophie Wahnich’s books are, but I still recommend them. See also: La gloire et l’effroi, Sept morts sous la Terreur (1997) and Les éclats du rire : la culture des rieurs aux 18e siècle (2000), but I don’t think either have been translated. Le Corps de l’histoire and La gloire et l’effroi also are nice complements to Marie-Hélène Huet’s book.

If you can read French, I really recommend the five essays reunited in Pour quoi faire la Révolution ? (2012), especially Guillaume Mazeau’s on the Terror (La Terreur, laboratoire de la modernité) – which I might try to eventually translate or at least summarize in English coz it’s really worth it.

The following books are extremely important to understand the historiographical feud and the controversies that surrounded the Bicentennial of the French Revolution in 1989 (and both have been translated to French so that’s cool too):

First, Steven L. Kaplan’s two volumes called Farewell, Revolution: Disputed Legacies (1995) and The Historians’ Feud (1996).

Then, Eric Hobsbawm’s Echoes of the Marseillaise: Two Centuries Look Back on the French Revolution (1990) which gives you the Marxist perspective on the debate. If you want to look for the non-Marxist perspective: look at literally any other book written on the French Revolution and its historiography (I’m not kidding). For example, you can read the introduction by Gwynne Lewis (1999 book edition; 2012 online edition) to Alfred Cobban’s The Social Interpretation of the French Revolution (1964), the founding “revisionist” book.

Again, if you can read French, I recommend Michel Vovelle’s Combats pour la Révolution française (1993) and 1789: L’héritage et la mémoire (2007). I have not read La bataille du Bicentenaire de la Révolution française (2017) but it might recycle parts of the previous two books, so I’d look that up first.

Marxist historiography is near inexistant in Anglophonia, because of reasons best explained in this short historiographical recap on Anglophone historiography and specifically Alfred Cobban (link opens as pdf), but there was Eric Hobsbawm, who wrote a series of very important books on “The Ages of…”:

The Age of Revolution: 1789-1848

The Age of Capital: 1848-1875

The Age of Empire: 1875-1914

The Age of Extremes: 1914-1991

Some of Albert Soboul’s works have been translated as well:

A Short History of the French Revolution, 1789-1799 (1977)

The Sans-Culottes: The Popular Movement and Revolutionary Government, 1793-1794 (1981)

Understanding the French Revolution (1988), which is a collection of various essays translated to English (here’s the table of contents)

While we’re on the subject of classics: I do need to re-read R. R. Palmer’s The Twelve Who Ruled (1941) to see if I still like it, but I believe it’s still positively received? I’ve never actually read C. L. R. James’ The Black Jacobins. Toussaint Louverture and the San Domingo Revolution (1963) but I’m going to rectify that this summer.

That’s a good way to segue into a final part.

Here is a list of books I technically have not read yet (I skimmed through them), but would still recommend because I trust the authors:

Michel Biard and Marisa Linton’s The French Revolution and Its Demons (2021) which was originally published in French as Terreur ! La Révolution française face à ses demons (2020). It looks like an excellent summary of all the controversies surrounding the Terror: Robespierre’s black legend, how the Terror was “invented”, the conflicts between different political factions and clubs, the Vendée, and stats on who actually died by the guillotine (no, there was no “noble purge”). (Here’s the table of contents.)

Peter McPhee wrote several good syntheses, the most recent being Liberty or Death: The French Revolution (2017). Others he wrote: Living the French Revolution, 1789-99 (2006) and A Social History of France, 1789-1914 (1992, reedited in 2004). Why 1914? The 19th century was defined by Hobsbawm (see above) as “the long 19th century” (by contrast with “the short 20th century”), or “the cultural and political 19th century”, which is regarded as lasting from the fall of Napoléon Bonaparte to the First World war.

Eric Hazan’s A People’s History of the French Revolution (2014) and A History of the Barricade (2015), which are translations (Une histoire de la Révolution française, 2012, and La barricade: Histoire d’un objet révolutionnaire, 2013). If you can read French, check out his essay published by La Fabrique: La dynamique de la révolte. Sur des insurrections passes et d’autres à venir (2015).

Just as a final note: this post is the equivalent of four half single-spaced pages in Times New Roman 12 pts. It also took two hours to write and format (and make the side-posts with table of contents) even though most of it is already written in several drafts – i.e. the long post series of in-depth recommendations, so that gives you an idea of why that other series of posts is taking so long to write.

I’m going to go lie down now. -_-

ETA: Corrected some typos and a link that didn't quite go to the right place.

#historiography#frev historiography#sophie wahnich#marie helène huet#antoine de baecque#michel vovelle#michel biard#marisa linton#eric hazan#peter mcphee#c. l. r. james#r. r. palmer#albert soboul#eric hobsbawm#françois gendron#francois gendron#dominique godineau#steven l. kaplan#jean pierre gross#alfred cobban#slavoj žižek#slavoj zizek#this post almost killed me

394 notes

·

View notes

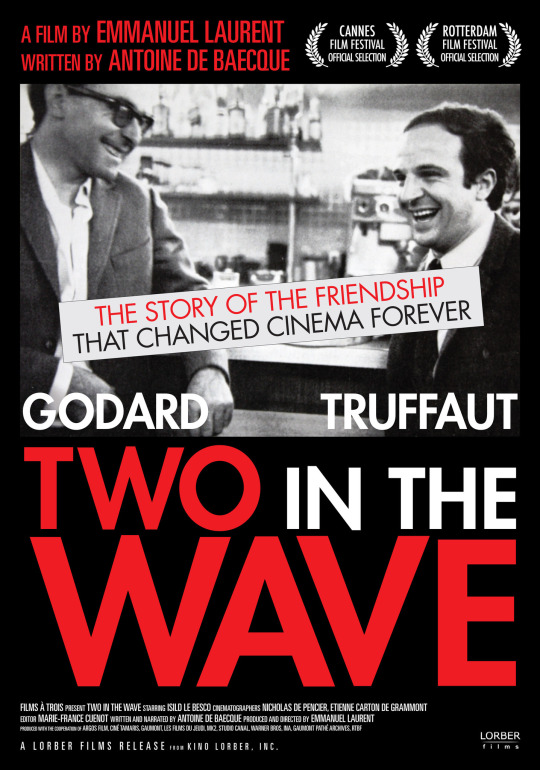

Photo

#emmanuel laurent#antoine de baecque#2010#2010s#france#documentary#movie documentary#nouvelle vague#François Truffaut#friendship#jean-luc godard#kino lorber

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Francois Truffaut by Antoine de Baecque, Serge Toubiana

#francois truffaut#antoine de baecque#serge toubiana#film#cinema#movies#french film#french cinema#french new wave#new wave#new wave cinema

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Je peux retenir dix-huit idées parallèles quelques heures durant (A. de Baecque)

Ce journal réunit une série de réflexions que la marche suscite et accueille avec générosité, que je me remémore le soir à l’étape après avoir fait usage de certaines mnémotechniques particulières mises au point depuis une dizaine d’années - par un double système de numérotation et d’abécédaire, je peux retenir dix-huit idées parallèles quelques heures durant. Je les consigne d’abord sur un cahier de notes itinérant avant de les retranscrire informatiquement quelques semaines plus tard, puis de les développer, pour certaines, à la lecture d’ouvrages complémentaires ou à la vue d’images ajoutées, réflexions frottées d’archives également ou comme remises dans le contexte de leur surgissement à la surface de ma conscience lors de ma marche solitaire. Il s’agit d’un processus de pensée et d’écriture par notations, transcriptions, décantation, ajouts, que j’associe pleinement à la marche: une méthode pédestre, intellectuelle et scripturaire.

(Ma transhumance. Carnets de routo, p.124-125)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Love Among the Ruins: Roberto Rossellini's "Journey to Italy"

In Roberto Rossellini's classic of modernist cinema, Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders are surprised by death among the ruins of Pompeii. And then they are surprised by grace.

Alex (George Sanders) and Katherine (Ingrid Bergman) on the road to Naples.

Alexander: “Where are we?” Katherine: “Oh, I don’t know exactly.”

— Opening lines of Journey to Italy

The first shot of Roberto Rossellini’s 1954 film, Journey to Italy, is through the windshield of a speeding Bentley on an open stretch of country road. It is an image of pure velocity, revealing neither…

View On WordPress

#"Journey to Italy" film#Antoine de Baecque#Dante Inferno#George Sanders#Ingrid Bergman#Iris Murdoch#James Quandt#Jean-Luc Godard#Julian of Norwich#Laura Mulvey#Naples#Paul S. Fiddes#Pompeii#Roberto Rossellini#Rossellini&039;s Voyage trilogy#Samuel Fuller#Vesuvius

0 notes

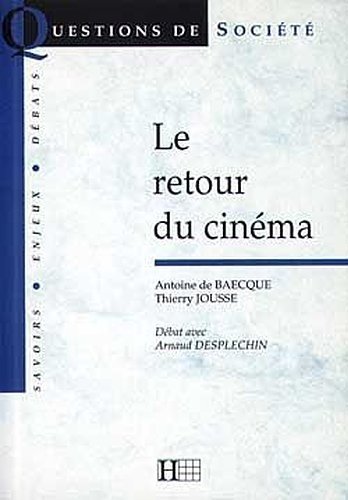

Photo

http://lemiroirdesfantomes.blogspot.com/2019/07/le-retour-du-cinema-les-metamorphoses.html?view=magazine

0 notes

Photo

Two weighty new biographies of two of the greatest masters of French cinema: Jean Renoir: A Biography, by Pascal Merigeau, from Ratpac Press, and Eric Rohmer: A Biography, by Antoine de Baecque and Noel Herpre, from Columbia University Press. Vive le cinéma!

#books#biography#cinema#film#film director#jean renoir#eric rohmer#france#french cinema#pascal merigeau#antoine de baecque#noel herpe#columbia university press#ratpac press#new books#new releases

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

What We Leave Behind by Stephan Crasneanscki with ...

" Subsequent to a commissioned sound composition for Deutschlandradio, multidisciplinary artist Stéphan Crasneanscki further examines his significant opus What We Leave Behind, on French film director Jean-Luc Godard's archive, into book form. The book is divided into four comprehensive sections: boxes, collages, still lifes and notes.

When invited to explore the archive of the seminal film director, Crasneanscki photographed Godard's personal collection of shot film, reel-to-reels and historical ephemera. The notes and references in the book attest to the passing of time, yet being saved from oblivion; as a fragmented creative map of a master film director's artistic thought process. In addition to working with someone’s personal belongings and its cultural heritage, Crasneanscki also adds his own interpretation and admiration to the material’s constellation of ideas of identity, traceability, temporality, space, memory, existence, materiality and historicity.

The book contains a foreword by musician, author and poet Patti Smith, a conversation with filmmaker Abel Ferrara and an essay written by film critic, historian and editor Antoine de Baecque. "

#Stéphan Crasneanscki#Jean-Luc Godard's archive#Jean-Luc Godard#RIP#film history#archive#photo book#photo books

26 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Three films a day, three books a week & records of great music would be enough to make me happy to the day I die.

François Truffaut, Truffaut: A Biography by By Antoine de Baecque, Serge Toubiana (University of California Press, September 4, 2000)

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

#9 Impact and influence on French cinema

The controversies that arose from Maurice Pialat's harsh filming methods on a set have recently resurfaced with Abdellatif Kechiche's La Vie d'Adèle. The Franco-Tunisian director pushed his actresses, Adèle Exarchopoulos and Léa Seydoux, to the limit, without hesitating to use manipulation and excess. As with Pialat, this violence, though reprehensible, is never gratuitous and is always intended to serve the film and the actors by giving them the opportunity to bring out the best in themselves.

As the historian Antoine de Baecque points out, the two directors have in common that they succeed in getting the "juice" from the actors, that hidden part of themselves that they never show in other directors. For him, Pialat's greatest influence on Kechiche is found in La Graine et le Mulet, released in 2007. We find there the search for the truth of words and forms of improvisation.

In fact, we could describe many films as "pialesques" in their search for moments of truth. It is then clear that the cinema of Maurice Pialat has marked several generations.

But perhaps the most "pialesque" character we have seen in recent cinema is that of the professor in Entre les murs, winner of the Palme d'Or in 2008. This character embodies all the fragilities, ambiguities and sensitivities of a human being. He is reminiscent of the teacher in La Maison des Bois, played by...Maurice Pialat!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Antoine de Baecque’s The Body Politic. Corporeal Metaphor in Revolutionary France, 1770-1800 (1997)

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Libération du mardi 29 octobre 2002. Paolo Roversi. Propos recueilli par Antoine de Baecque et Brigitte Ollier. Extrait : Comment en arrivez-vous à une photo unique? Pour moi, le plus excitant c’est l’instant même où je fais la photo. C’est cela, d’abord, qui est unique. Je ne prépare pas beaucoup avant la prise. Rien n’est dessiné, élaboré, je laisse faire l’équipe pour l’éclairage, le maquillage, la coiffure, le décor. Et ce qui se passe après m’intéresse peu... Je ne suis pas un technicien. Il n’y a qu’un moment d’émotion, d’excitation, de concentration, mais aussi de hasard, d’accident. Tout le mystère de la photographie tient dans la prise de vue. Je cherche toujours à être ému quand je prends une photo: la découverte, puis le choix de la photo sont quasi immédiats. C’est un instantané où tout se réunit, mon humeur, celle du mannequin, de l’équipe.Tout rentre dans l’image, la chanson que j’ai écoutée le matin comme le chagrin d’amour de la fille. Comme un coup de pinceau, un seul.

14 notes

·

View notes