#michael hardt

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Lauren Berlant:

…

“I often talk about love as one of the few places where people actually admit they want to become different. And so it’s like change without trauma, but it’s not change without instability. It’s change without guarantees, without knowing what the other side of it is, because it’s entering into relationality.

The thing I like about love as a concept for the possibility of the social, is that love always means non-sovereignty. Love is always about violating your own attachment to your intentionality, without being anti-intentional. I like that love is greedy. You want incommensurate things and you want them now. And the now part is important.

The question of duration is also important in this regard because there are many places that one holds duration. One holds duration in one’s head, and one holds duration in relation. As a formal relation, love could have continuity, whereas, as an experiential relation it could have discontinuities.

When you plan social change, you have to imagine the world that you could promise, the world that could be seductive, the world you could induce people to want to leap into. But leaps are awkward, they’re not actually that beautiful. When you land you’re probably going to fall, or hurt your ankle or hit someone. When you’re asking for social change, you want to be able to say there will be some kind of cushion when we take the leap. What love does as a seduction for this is, and has done historically for political theory, is to try to imagine some continuity in the affective level. One that isn’t experienced at the historical, social or everyday level, but that still provides a kind of referential anchor, affectively and as a political project.“

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Imperial racism, or differential racism, in the society of control integrates others with its order and then orchestrates those differences in a system of control. Fixed and biological notions of peoples thus tend to dissolve into a fluid and amorphous multitude, which is of course shot through with lines of conflict and antagonism but none which appear as fixed and eternal boundaries. The surface of the imperial society of control continuously shifts in such a way that it destabilizes any notion of place.

– Michael Hardt, "The Global Society of Control" (1998)

#Michael Hardt#Marx#Society of Control#Deleuze#Malaise#Theory#Deleuze and Guattari#Words#Quote#Writing#Text#Reading#Books#⛓️

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

<<Indudablemente es cierto que, en concordancia con los procesos de globalización, la soberanía de los Estados-nación, si bien continúa siendo efectiva, ha ido decayendo progresivamente. Los factores primarios de producción e intercambio -el dinero, la tecnología, las personas y los bienes- cruzan cada vez con mayor facilidad las fronteras nacionales, con lo cual el Estado-nación tiene cada vez menos poder para regular esos flujos y para imponer su autoridad en la economía. Ya ni siquiera deberíamos concebir a los Estados-nación más dominantes co- mo autoridades supremas y soberanas, ni fuera de sus fronteras ni tampoco dentro de ellas. La decadencia de la soberanía de los Estados-nación no implica, sin embargo, que la soberanía como tal haya perdido fuerza. Durante todo el tiempo en que se produjeron las transformaciones contemporáneas, tanto los controles políticos y las funciones del Estado como los mecanismos reguladores continuaron gobernando el ámbito de la producción y el intercambio económico y social. Nuestra hipótesis básica consiste en que la soberanía ha adquirido una forma nueva, compuesta por una serie de or- ganismos nacionales y supranacionales unidos por una única lógica de dominio. Esta nueva forma global de soberanía es lo que llamamos “imperio”.>>

Michael Hardt y Antonio Negri: Imperio. Editorial Paidós, págs. 13-14. Barcelona, 2002.

#hardt y negri#hardt#negri#michael hardt y toni negri#michael hardt#toni negri#imperio#globalización#estado-nación#estados-nación#soberanía#decadencia#dominio#dominación#lógica del dominio#regulación#intercambio#intercambio económico#intercambio social#filosofía política#teo gómez otero#economía#antonio negri

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

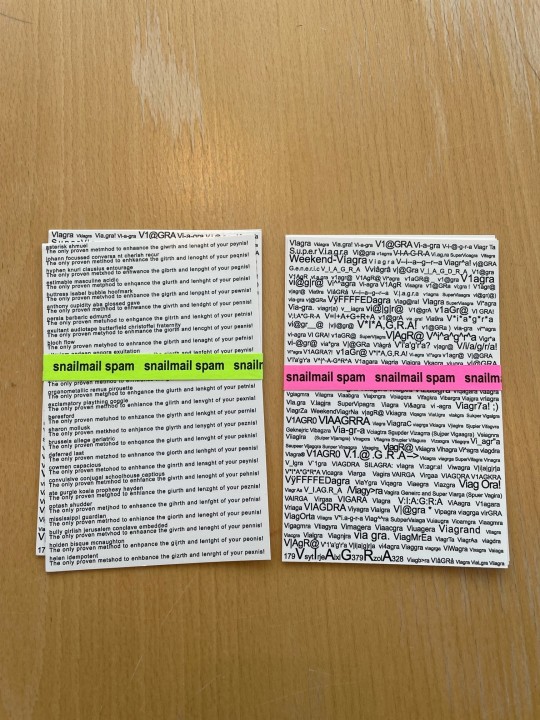

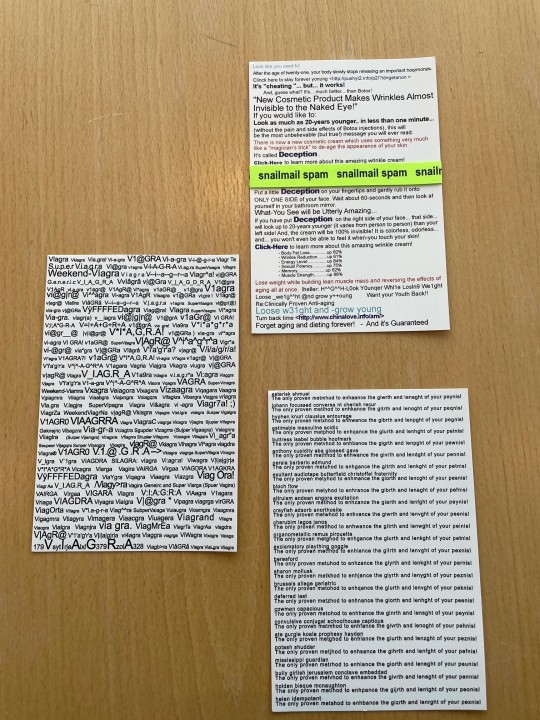

Una vida examinada. Colección de 3 zines

3 zines para tocar, oler y mirar, para pensar y sentir.

3 pensadores estadounidenses contemporáneos: Judith Butler, Michael Hardt y Cornel West.

3 conversaciones traducidas por primera vez al español como introducción posible —y accesible— a su pensamiento, basadas en el documental y en el libro Una vida examinada (Astra Taylor, 2008), en el que se intenta mostrar que la filosofía también puede ser una práctica de pensamiento vital y un arte de hacer preguntas con fuerza para despabilarnos.

3 conceptos diferentes para pensar la época en que vivimos: interdependencia, revolución y verdad.

¿A qué queda reducida la izquierda si abandona el concepto de revolución? ¿Tiene sentido seguir hablando de revolución hoy? Michael Hardt sostiene que sí, pero a condición de que la repensemos —y vivamos— como una práctica de transformación subjetiva-colectiva cuyo fin es la democracia y que sólo puede realizarse si la empezamos a ejercitar aquí y ahora, donde sea que estemos. ¿Pero quiénes están dispuestxs a transformarse a sí mismxs para devenir capaces de horizontalidad y de una verdadera democracia? Judith Butler, por su parte, cuestiona con su particular lucidez la idea de individuos autosuficientes para pensar lo humano como un sitio de interdependencia. Somos madejas de relaciones cambiantes —a veces capaces de muchas cosas, a veces frágiles— y estamos indisolublemente ligadxs a lxs otrxs. ¿Por qué no partir de la constatación de nuestra común interdependencia y de nuestra común necesidad de cuidados para construir sociedades en las que todxs podamos vivir y florecer, cualesquiera sean nuestros cuerpos, nuestra edad, nuestro deseo…? ¿Y qué contribuciones pueden hacer los estudios de la discapacidad y del género para cuestionar las normas de productividad y autosuficiencia que aprisionan los cuerpos? Por fin, Cornel West, autodefiniéndose como un hombre del blues en el mundo de las ideas, propone partir de la catástrofe y no quedarnos esperando románticamente una totalidad que jamás existió y jamás va a existir, un ideal de completud que sólo nos deja sumidxs en el lenguaje de la decepción y del fracaso. Pero si nuestro punto de partida es la catástrofe ya consumada, ¿qué herramientas nos quedan para transitarla? Ahí es donde la verdad —provisoria, con minúscula— puede jugar un papel, entendida de un modo existencial y ligada al ejercicio de virtudes como el coraje.

3 zines autogestivos para que las ideas salgan a pasear por las calles de la ciudad y sean leídas en los contextos más dispares (en el subte, en la sala de espera, en el parque, en la marcha), multiplicando las preguntas, los diálogos y los horizontes.

3 lugares de CABA donde pueden conseguirse:

1) Ratita Libros. Suipacha 925, local 6, CABA @ratitalibros

2) La libre – Cooperativa de libros y cultura. Chacabuco 917, CABA

3) Migra – Feria de arte impreso. Centro Cultural Plaza Defensa, Defensa 535, 5 & 6 de abril, CABA

3 caminos que nos salvarán: horizontalidad + cooperativismo/autogestión + ética del cuidado

¡Ojalá les entusiasme!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Michael Hardt – Yıkıcı Yetmişler (2024)

Michael Hardt, yetmişlerdeki devrimci hareketleri alışılagelenden bambaşka bir bakış açısıyla yorumluyor. Ona göre bu hareketler altmışlarda doruk noktasına ulaşan sol hareketin bitişini ve yenilgisini ifade etmez. Aksine, bir yandan devrimci hareketlere yönelik şiddet ve baskının arttığı, öte yandan merkezcil ve hiyerarşik sol söylemin artık işe yaramadığı bir dönemde, yetmişlerdeki hareketler,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

karin hardt und viktor staal: via mala, josef von báky 1945

*

simone prüfer, pressekonferenz abrissarbeiten carolabrücke dresden, ard mediathek 09/13/24

#via mala#josef von báky#1945#karin hardt#viktor staal#carolabrücke#dresden#pressekonferenz#abrissarbeiten#tiefbauamt#simone prüfer#feuerwehr#michael klahre#pressesprecherin#barbara knifka#mdr#ard#mediathek

0 notes

Text

Creating a golem is dangerous business, as versions of the legend increasingly emphasize in the medieval and modern periods. One danger expressed particularly in medieval versions is idolatry. Like Prometheus, the one who creates a golem has in effect claimed the position of God, creator of life. Such hubris must be punished. In its modern versions the focus of the golem legend shifts from parables of creation to fables of destruction. The two modern legends from which most of the others derive date from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In one, Rabbi Elijah Baal Shem of Chem, Poland, brings a golem to life to be his servant and perform household chores. The golem grows bigger each day, so to prevent it from getting too big, once a week the rabbi must return it to clay and start again. One time the Rabbi forgets his routine and lets the golem get too big. When he transforms it back he is engulfed in the mass of lifeless clay and suffocates. One of the morals of this tale has to do with the danger of setting oneself up as master and imposing servitude upon others.

The second and more influential modern version derives from the legend of Rabbi Judah Loew of Prague. Rabbi Loew makes a golem to defend the Jewish community of Prague and attack its persecutors. The golem’s destructive violence, however, proves uncontrollable. It does attack the enemies of the Jews but also begins to kill Jews themselves indiscriminately before the rabbi can finally turn it back to clay. This tale bears certain similarities to common warnings about the dangers of instrumentalization in modern society and of technology run amok, but the golem is more than a parable of how humans are losing control of the world and machines are taking over. It is also about the inevitable blindness of war and violence. In H. Leivick’s Yiddish play, The Golem, for instance, first published in Warsaw in 1921, Rabbi Loew is so intent on revenge against the persecutors of the Jews that even when the Messiah comes with Elijah the Prophet the rabbi turns them away. Now is not their time, he says, now is the time for the golem to bathe our enemies in blood. The violence of revenge and war, however, leads to indiscriminate death. The golem, the monster of war, does not know the friend-enemy distinction. War brings death to all equally. That is the monstrosity of war.

Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire, 2004

231 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Spy in Black Dir. Michael Powell 1939

I was going to combine this and Dark Journey in one post, but I ended up writing way more about The Spy in Black than I thought I would. I'm so, so glad I came back to this film. Rereading my initial thoughts after my first viewing, I realize clearly missed a lot because I was too hyperfocused on Connie being the way he is. But I did rewatch Dark Journey recently, and ended up liking that movie a whole lot less the second time around, so I'm not really in any hurry to post about it.

...

The Spy in Black feels worlds away from the grand, technicolor masterpieces of Powell and Pressburger. Despite the whole final act taking place at sea with the U-boats and battleships firing at one another, the film doesn't come close to the opulence of what are perhaps The Archers' most well-known and beloved films. The Spy in Black is minimalist by comparison, and yet it doesn’t feel out of place when considered among their other works.

Set mostly in the Orkney Islands, a damp and cold feeling permeates the film. That's something The Archers are exceptionally good at as filmmakers -- creating a multisensory experience for the viewer just through their visuals and sound design. Whether it's their wind battered Himalayan monastery in Black Narcissus, or the ever present rain and closeness of the sea to the little schoolhouse in The Spy in Black, Powell and Pressburger films are undeniably immersive. Atmosphere and a sense of place are key defining factors in their films even in this, their earliest work together.

The filmmakers also of course were aware of Conrad Veidt's prestige and wanted to make sure the look of the film paid homage to Connie's past work. There are scenes with deep, angular shadows for Hardt to disappear into and creep out of like in Caligari or Orlac. The title of the film has been bugging me, but now I think it's not so much about what Hardt wears as it is about him lurking in the shadows. (There's also a cute story about Michael Powell and Connie's first meeting where Powell was more than a little star struck; I believe he went on and on about Connie's deep blue eyes and his purring voice, which is understandable.)

The writing suits their actors so perfectly. Compared to Dark Journey where everyone is so painfully British when they aren't supposed to be, there's something in the writing and direction that differentiates the nationalities in The Spy in Black. So even Marius Goring, who is British as can be, when playing a German naval officer isn't quite AS British as Sebastian Shaw and Valerie Hobson, if that makes any sense. It's a subtle difference, but there's something about the performances in this film compared to Dark Journey that allow for a greater suspension of disbelief.

And it's funny! Maybe not as obviously funny as Contraband, but The Spy in Black has some really finely crafted comedic moments that don't feel out of step with the rest of the film. It's not a comedy by any means; it's a drama with room for humor, kind of like real life… just with better looking people. When Hardt is wrestling his motorbike up a hill and is startled by a bunch of sheep, he baas back at them! It's a little moment that feels random at the same time it feels relatable. And it humanize Hardt, who doesn't really need the help -- he's already at this point in the movie completely endeared to the audience (or should be if you have a heart and eyes to see him). Most of the humor in the movie comes from Hardt being put in Situations.

The whole butter thing is so delightfully stupid. They establish Hardt early on as a foodie and a glutton, if only because he's been deprived of good food for great lengths of time. So when he arrives at the schoolhouse rendezvous and is checking each room to make sure it's safe, when the camera catches him in closeup staring with extreme intensity at something off screen. We're to think he suddenly sees something dangerous. The camera cuts to Miss Burnett/Fräulein Thiel/Mrs Blacklock looking confused and concerned. The music builds dramatically as they cut back to Hardt who is creeping towards the table. He reaches down, grabs something, the music crescendos, he lifts the thing to his face -- it's a giant block of butter.

It's delightful, it speaks to anyone who loves food, or at least just to me. Hardt then proceeds to eat most of the butter and, like, half a ham before collapsing but not without first lighting what are clearly supposed to be post-coitalesque cigarettes for himself and Thiel. Even though they spend most of the middle of the film flirting like goddamn pros, sharing a decadent meal is the closest they get to anything explicitly sexual.

Production began towards the end of 1938 and the film was released in the spring of 1939. While England didn't officially enter the war until the following fall, one would have to imagine the threat of conflict was making the general population anxious. The Spy in Black is a WWI film, set in 1917, but unlike other cinematic narratives of the 1930s centered around past wars, this film doesn’t really go out of its way to glorify the military or present a particularly nationalistic story. All the characters are heroic, all the characters are flawed, none more so than the man at the center of the film, Captain Ernst Hardt, a German U-boat captain. The balls they had to make a film with this kind of protagonist at this time. Yet the film doesn't claim to make any kind of sweeping judgement, positive or negative, about Germans. It seems more likely that with the war looming, Hardt is less of a statement about Germans in general and more like Dark Journey's Von Marwitz: both characters seem to be informing the British audience that this outsider, Conrad Veidt, this man you mainly know as a screen villain, is a good man. He's one of us, it seems to suggest.

This film, perhaps uniquely for its time, focuses on the individuals rather than the nations they represent. It seems more focused on how each of the main characters are personally affected by their actions. While the acts of espionage are played out with slick intrigue, by the end of the movie Hardt and Mrs Blacklock are both full of regret. Everything they've done has done little more than lead to the deaths of people who had lives, families, people who loved them. No amount of honor and devotion to one's country in wartime can wash the blood from their hands. In Mrs Blacklock's case, I don't believe her heart was really in it. She breaks down on the captured ferry and says, "You’re in the hands of a man who cares nothing for his life or yours. And it's all my fault. I forgot we were at war, forgot that war means that it kills every fine, decent human feeling." And Hardt himself, for all his good intentions and humanity extended to his prisoners on the ferry, loses every one of his crew, men who may have been the only people he truly cared about in the entire world. And having lost them, having not been able to protect them from the fatal depth charge that struck their U-boat, he has nothing left to live for. The machine of war, or more accurately the psychology of war, claims Hardt as yet another victim. The real villain of The Spy in Black is not the German naval captain nor his men, but rather the war itself. The Spy in Black is at its heart, under all the sexually suggestive dialogue and clever cinematography, an anti-war movie masquerading as a standard espionage thriller.

Valerie Hobson apparently was hired to replace Vivien Leigh and, honestly, thank god. A hundred thousand Vivien Leigh fans would swarm my house with torches and pitchforks if they ever read this, but Valerie Hobson is a better actor and more charismatic, SORRY. She has more range and better comedic timing than Leigh (who went on to do Gone With The Wind anyway, so good for her I guess). Val is maybe more fun in Contraband, but I love that she and Connie got on so well, on screen and off, with each other and with Powell and Pressburger that they all got back together to make a second film. Watching The Spy in Black again, Contraband definitely feels like the more self-indulgent film, but I don't care. And here we get to see the beginning of that collaboration, see the sparks fly as Val and Connie expertly handle the dialogue and direction. I love their dynamic on screen; Hardt deferring to this woman that he thinks is his superior, the way she corrects his English (which was something Val did to Connie in real life that adorably carried over into the film), the way she barks at him to pick up his motorbike and go to bed, the way she looks at him at the end of the film with heartbreak in her eyes but can't bring herself to apologize or say anything at all. UGH. UUUUUGGHHHH. She and Connie have so many great moments together in this film, it's impossible to pick a favorite.

(Powell and Pressburger dared to put Connie and Val nose to nose and have him say to her, "It is evening and I am grown up, " knowing full well what this would do to unsuspecting audiences, only to -- just one year later -- go "hold my beer" and make give him even worse lines in Contraband. GOATed.)

Connie genuinely seems like he's having 10x more fun on this film than Dark Journey. For one thing, he's welcomed back to England after a couple flops and a stopover in France with a more interesting, more fully realized character, one where he's allowed to bring in more of his own opinions and creative choices. Captain Hardt feels more like a real guy, he's less perfect than Von Marwitz. On this rewatch, I realized I'd forgotten how gruff and grumpy Hardt is (which, like Andersen in Contraband, I chalk up to him being hangry). As captain, he's no-bullshit but endures lighthearted teasing from his shipmates. He's allowed to have a friend! Schuster and Hardt clearly have history, they aren't new to one another, they speak (comedically) in unison, after all. I mean, Hardt brings Schuster a block of butter later in the film! That's real friendship.

Hardt makes it known that he loves food, even simple things like bread and butter. This may have more to do with the military rations being beyond bad than a pre-existing character trait of Hardt's, but it gives him color and humanity. And Hardt is just as smooth as the Von Marwitz; when the fiancé of the real Miss Burnett shows up and sees the medal ribbon on his uniform, Hardt slyly and proudly states that it's the "Iron Cross, second class." And when Miss Burnett's fiancé assumes Hardt must be a prisoner of war, the Captain replies, slowly drawling his pistol, "No… you are." And all with the most perfect, calm confidence. He's a Bad MF, no lie.

So many interesting little things get revealed about Hardt pretty early on in the film. There are multiple exchanges about cigarettes being unavailable and someone offering him a pipe to which he says, "I never smoke a pipe." (As far as I see it, and I'm not complaining, but one of the only character differences between Hardt and Captain Andersen in Contraband is that Andersen does smoke a pipe lol) There are a handful of possibly queer coded things they throw in too: Schuster finds it humorous that Hardt would be reciting poetry in the dark to the lady spy he's to meet, to which Hardt says, "You think it's so funny, you know what you can do with it!" And earlier, when someone is looking for the captain, they're told, perhaps with an implied wink, that he might be found at the Turkish baths. Then there's the whole thing with Hardt literally pulling the cigar away from Schuster's mouth. I'm not saying definitively that Hardt is bi… but isn't he, though??

He is ultimately a reluctant spy; when he receives his orders to meet the German agent in Scotland, he's more annoyed than excited. He grumpily accepts his orders, but as a decorated military officer, doing spy stuff is beneath him. He insists on wearing his uniform even at the schoolhouse when he's supposed to be in hiding, because if he should die in service of his duties, he'd rather meet his end as Captain Hardt, not as an assumed identity.

Hardt is so wrapped up in his identity as a military officer that it ends up killing him. His end is tragic, nearly Shakespearean. He is not without honor, in fact he's positively full of it. He seems born and bred to follow orders, to whatever end they may have. And yet he is not a bad man. He commands authority but does not wield it with cruelty. He tells his crew to shoot any of the prisoners on the captured ferry who make noise, "with one exception" for a crying infant, and he allows the prisoners to escape on the lifeboats when the ship is sinking. Hardt cannot stop his own men from firing on the ferry, what they think is an enemy ship -- they have no way of knowing Hardt's taken over command of the ferry. Even his desperate and helpless cries and signals can't carry over the water to reach them in time. As the ship slowly sinks and everyone, including the ferry's original captain and crew, disembarks, Hardt elects to stay behind -- as his U-boat's commanding officer and with his entire crew lost and his captured ship sunk, Hardt makes the decision, in his mind the only decision, to die a captain's death at sea. The last time we see Hardt in closeup, he has tears in his eyes. We don’t see him drown, but we watch as an abandoned lifejacket floats across the frame. It's heartbreakingly tragic; we've gotten to know him, maybe even love him, over the course of the film.

I know I'm going on and on about this one, and I'm almost done, but I have a few more things to say.

People loved to get on Connie's case for his English pronunciation and his supposedly heavy German accent, but he sounds amazing in this film. He plays up some German pronunciation of certain words for comedic effect (Exhibit A: "Bütter"), but his natural accent is so inoffensive here (not that it's ever that bad, even in Rome Express or FP1 imo), and it sounds like he even tried to play it down even more than usual. And if I've said it once I've said it a hundred times, he's such a fucking master of vocal delivery. Hardt's voice sits almost in the same pocket that Von Marwitz's does but Hardt is allowed to be more expressive in his range. I feel like I have a whole separate post in me strictly about Connie's use of his voice. He's a master technician vocally, and yet for as studied as his film speaking voice in English may have been, it never sounds to my ears anything other than effortless and natural.

To wrap things up: Powell, Pressburger, Connie and Val Hobson really are the dream team. The Spy in Black is yet another movie I immediately wanted to watch again the second it was over. It's a 10.

#my writing#conrad veidt#the spy in black#hardt + bütter is my profile pic so i had to write about this movie at some point

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zack Hardt by Michael Stokes

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joy and the Spinozan current

To reduce these problems to a complete and final analysis would be to miss the point. The best thing would be an informal discussion capable of bringing about the subtle magic of wordplay.

It is a real contradiction to talk of joy seriously.

—Alfredo Bonanno[5]

Pursuing these questions took us on a long detour through a minor current of Western philosophy associated with Baruch Spinoza. Against the grain of European thought that sought to subdue life through rigid dualisms and classifications, Spinoza conceptualized a world in which everything is interconnected and in process.

This worldview meant that Spinoza was despised by most of his contemporaries, but his ideas have influenced numerous currents of radical theory and practice, including anarchism, autonomous Marxism, affect theory, deep ecology, psychoanalysis, post-structuralism, queer theory, and even neuroscience. We are drawing on a current that runs from Spinoza through Friedrich Nietzsche, Gustav Landauer, Michel Foucault, and Gilles Deleuze to contemporary radicals like the Invisible Committee, Colectivo Situaciones, Lauren Berlant, Michael Hardt, and Antonio Negri. What we have found exciting about this current is the focus on processes through which people become more alive, more capable, and more powerful together. For Spinoza, the whole point of life is to become capable of new things, with others. His name for this process is joy.

Joy? What? Doesn’t joy just mean happiness, with some vaguely Christian undertones? Later we’ll be more precise about joy, but for now we want to be clear that it is not the same thing as happiness. A joyful process of transformation might involve happiness, but it tends to entail a whole range of feelings at once: it might feel overwhelming, painful, dramatic and world-shaking, or subtle and uncanny. Joy rarely feels comfortable or easy, because it transforms and reorients people and relationships. Rather than the desire to exploit, control, and direct others, it is resonant with emergent and collective capacities to do things, make things, undo painful habits, and nurture enabling ways of being together.[6]

Moreover, Spinoza’s concept of joy is not an emotion at all, but an increase in one’s power to affect and be affected. It is the capacity to do and feel more. As such, it is connected to creativity and the embrace of uncertainty. Within the Spinozan current, there is no way to determine what is right and good for everyone. It is not a moral philosophy, with a fixed idea of good and evil. There is no recipe for life or struggle. There is no framework that works in all places, at all times. What is transformative in one context might be useless or stifling in another. What worked once might become stale, or, on the other hand, the recovery of old memories and traditions might be enlivening. So does this mean anything goes? People just do what they want? Rejecting universal arbiters like morality and the state doesn’t mean falling into “chaos” or “total relativity.” The space beyond fixed and established orders, structures, and morals is not one of disorder: it is the space of emergent orders, values, and forms of life.

#joy#anarchism#joyful militancy#resistance#community building#practical anarchy#practical anarchism#anarchist society#practical#revolution#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

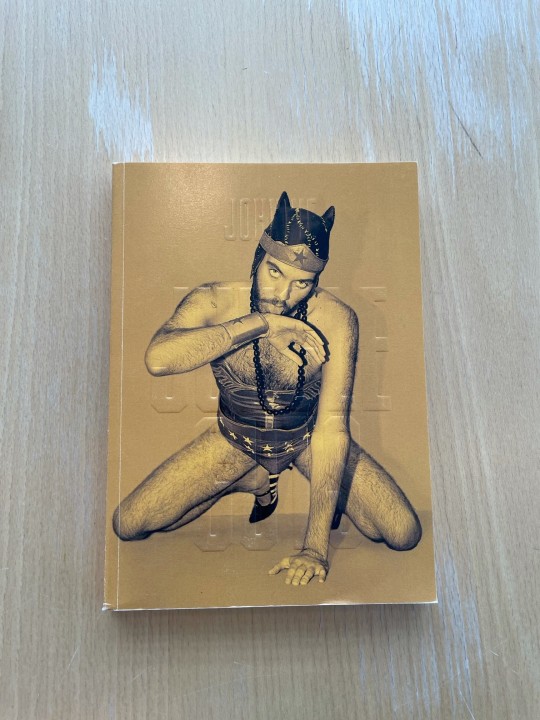

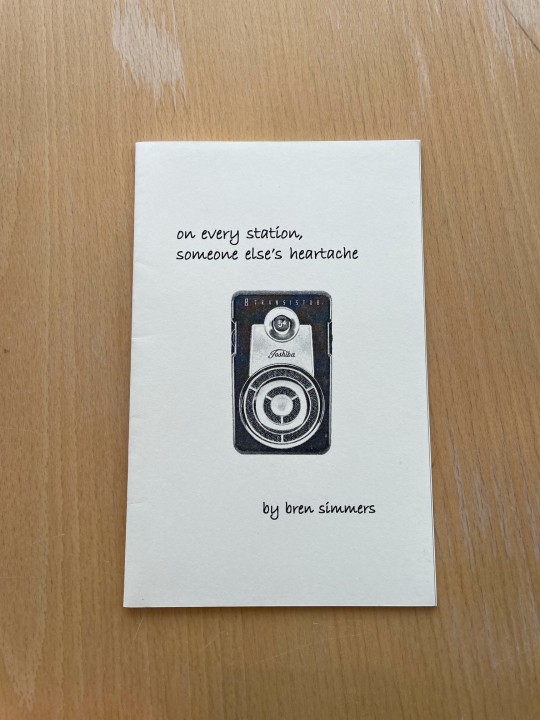

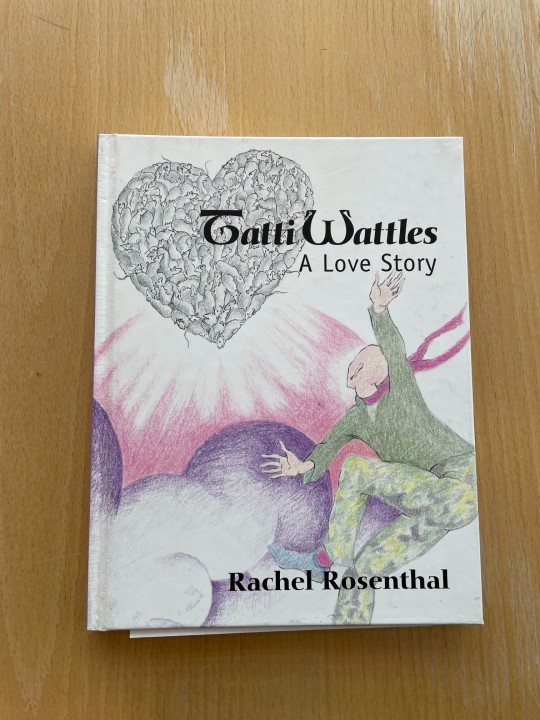

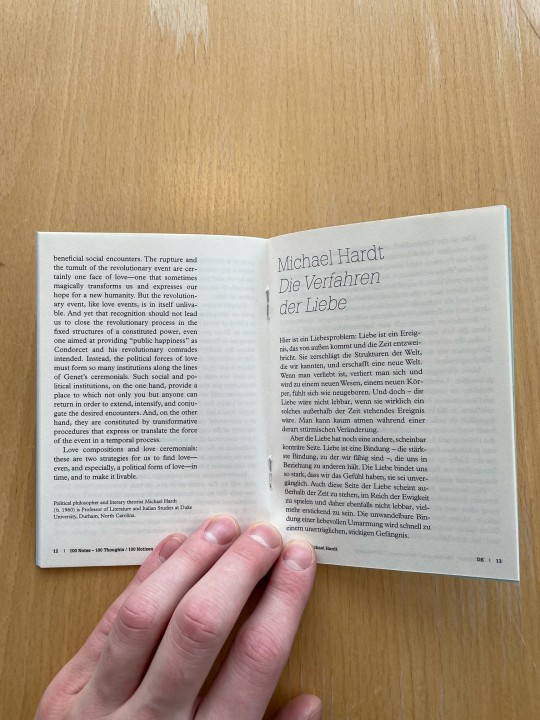

❤️FEBRUARY ARTIST BOOK DISPLAY❤️

Love poem. Kathy Slade, Michael Joseph Phillips. Vancouver, BC : Publication Studio Vancouver, 2015. Love Letter to Anatolia. Tanya Evanson. Vancouver, BC : Mother Tongue Media, 2012.

Johnny Jungleguts : Life, Sex Fandom: Collected Writings. Jonny Jungleguts, Leslie Dick. Closing, 2017.

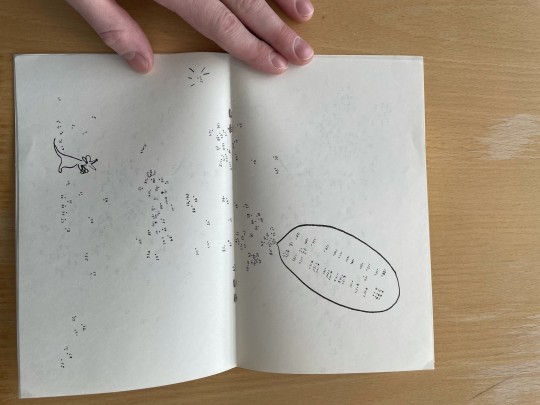

Loveland. Charles Stankievech. Berlin : K. Verlag, 2011.

The P*rnographic Connect-the-dots Book. Michael Riley. Paranoid Productions, 1974.

This is Still a Love Story: (The Twos). Emilee Nimetz. Canada : Emilee Nimetz, 2014.

On Every Station, Someone Else's Heartache. Bren Simmers. Victoria, BC : Rubber Boot Rodeo, 2002.

Tatti Wattles : A Love Story. Rachel Rosenthal. Santa Monica, CA : Smart Art Press, 1996.

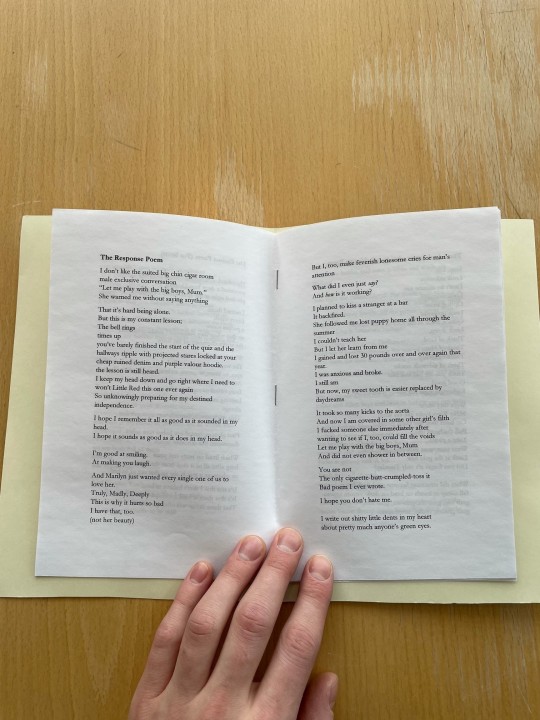

The Procedures of Love. Michael Hardt. Ostfildern : Hatje Cantz, 2012.

Relationship Stories from Tunnel Mountain. Andrea deBrujin. Banff, AB: The Banff Centre, 2015.

Everybody Deserves Love, Even You. Lynne Heller. Toronto : Lynne Heller, 2004.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Furthemore, genetic modifications has led to a flood of patents that transfer control from the farmers to the seed corporations. This functions as a key lever in the concentration of control over agriculture that we discussed earlier. The primary issue, in other words, is not that humans are changing nature but that nature is ceasing to be common, that it is becoming private property and exclusively controlled by its new owners.

Multitude: War and Democracy in Age of Empre by Antonio Negri, Michael Hardt

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why do you accept being treated like an inmate?

— Michael Hardt & Antonio Negri, Declaration

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Epígrafes de Imperio (2000), Antonio Negri y Michael Hardt.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Losurdo's Western Marxism with Gabriel Rockhill

youtube

In this episode Gabriel Rockhill returns to the show to discuss the publication of Domenico Losurdo's book, 'Western Marxism: How it was Born, How it Died, How it can be Reborn.' Which was recently published in English for the first time on Monthly Review Press.

From the MR book description:

"Western Marxism: How It Was Born, How It Died, How It Can Be Reborn is a paradigm-shifting book that provides a trenchant critique of the Western left intelligentsia. It reveals how its dominant ideological orientation—characterized by defeatism, utopianism, and anti-communism—is rooted in the political economy of imperialism. Internationally acclaimed theorist Domenico Losurdo thus provides a fresh and challenging perspective on purportedly radical thinkers who have been widely promoted in the imperial core, including those affiliated with the Frankfurt School, French Theory, and operaismo, as well as Hannah Arendt, Giorgio Agamben, Michael Hardt, and Slavoj Žižek, among others. His critique also has wide-reaching implications for trend-setting discourses inspired by this coterie of intellectuals, from postcolonial and decolonial theory to subaltern studies and beyond. Far from being a negative undertaking, however, this book is grounded in the positive project of reigniting anti-imperialist Marxism.

As a complement to the Italian edition of Western Marxism, this first-ever English translation also features the unprecedented publication of a major lecture that demystifies “Western Marxism” and its role in imperialists’ efforts to denigrate the achievements of actually existing socialism. Raising the stakes of what it means to produce critical theory, Western Marxism will surely provoke wide debate and a reevaluation of hallowed canons."

Gabriel Rockhill is a philosopher and activist who has published nine books. He is the Founding Director of the Critical Theory Workshop and Professor of Philosophy at Villanova University.

You can find many videos, interviews, and lectures with Gabriel Rockhill on the Critical Theory Workshop's Youtube Page: @criticaltheoryworkshop5299

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A third mode now appears, which may be labeled poetic in that it combines an aesthetic of coherence with a politics of incoherence. This regime is seen often in certain brands of modernism, particularly the highly formal, inward-looking wing known as “art for art’s sake” but also, more generally, in all manner of fine art. It is labeled “poetic” simply because it aligns itself with poesis, or meaning-making in a general sense. The stakes are not those of metaphysics, in which any image is measured against its original, but rather the semiautonomous “physics” of art, that is, the tricks and techniques that contribute to success or failure within mimetic representation as such. Aristotle was the first to document these tricks and techniques, in his Poetics, and the general personality of the poetic regime as a whole has changed little since. In this regime, lie the great geniuses of their craft (for this is the regime within which the concept of “genius” finds its natural home): Alfred Hitchcock or Billy Wilder, Deleuze or Heidegger, much of modernism, all of minimalism, and so on. But you counter: “Certainly the work of Heidegger or Deleuze was political. Why classify them here?” The answer lies in the specific nature of politics in the two thinkers and the way in which the art of philosophy is elevated over other concerns. My claim is not that these various figures are not political but simply that their politics is incoherent. Eyal Weizman has written of the way in which the Israeli Defense Forces have deployed the teachings of Deleuze and Félix Guattari in the field of battle. This speaks not to a corruption of the thought of Deleuze and Guattari but to the very receptivity of the work to a variety of political implementations (that is, to its “incoherence”). To take Deleuze and Guattari to Gaza is not to blaspheme them but to deploy them. Michael Hardt and Negri, and others have shown also how the rhizome has been adopted as a structuring diagram for systems of hegemonic power. Again this is not to malign Deleuze and Guattari but simply to point out that their work is politically “open source.” The very inability to fix a specific political content of these thinkers is evidence that it is fundamentally poetic (and not ethical). In other words, the “poetic” regime is always receptive to diverse political adaptations, for it leaves the political question open. This is perhaps another way to approach the concept of a “poetic ontology,” the label Badiou gives to both Deleuze and Heidegger. While for his own part, Badiou’s thought is no less poetic, he ultimately departs from the “poetic” regime thanks to an intricate—and militantly specific—political theory.

Alexander R Galloway. “The Unworkable Interface.” New Literary History 39, no. 4 (2008)

#reading#have been thinking about this one basically non stop since i read it#actually read this text before like over a year ago just never read this part bc i wasnt writing abt politics lol

4 notes

·

View notes