#michał poniatowski

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Galician campaign of 1809

Today let me tell you a little bit about the Galician campaign of the Austro-Polish war of 1809, which proved to be a great success for the Duchy of Warsaw.

After the battle of Raszyn there happened the series of small battles, which prevented Austrians from crossing the Vistula, thus leaving the initiative on the right bank of the river firmly with the Poles. So, the Polish forces under Poniatowski’s command moved along Vistula to the South-East, to the lands Austria seized during the latest partition of Poland.

On the 14th of May the Polish Army entered Lublin:

Konstanty Gorski, "Prince Józef Poniatowski enters conquered Lublin in 1809, showered with flowers by ladies"

As Kajetan Koźmian recalls in his memoirs, Poniatowski and his men were greeted with "joy and elation", and in the evening "... the city and the citizens gave a great ball <...> in the house in Korce. Prince Józef honored them with his presence starting the ball."

The next city on the way of the Polish Army was Sandomierz, and after a short siege it was taken on the 18th of May.

Siege of Sandomierz in 1809.

Michał Stachowicz, a scene from the battles in Galicia ("The Capture of Zamość")

Then there was Zamość, where the Polish trooped entered on the 20th of May.

Siege of 1809, M. Adamczewski Entry of Prince Poniatowski to Zamość (postcard)

On the 27th of May the Polish advanced forces even reached the city of Lwów, but prince Józef wasn’t among them.

Meanwhile the Austrians under command Archduke Ferdinand realized the precariousness of their position in the center of Poland, and on the 1st of June left Warsaw for the south.

Poniatowski, for his part, decided not to engage with the Austrian, focusing instead on "liberating” as much Galician land as possible.

Prince Józef Poniatowski seeks information from local peasants in Galicia in 1809, a photo of Stanisław Bagieński's painting

On the 3rd June there appeared the third participant of the events - Russian forces crossed the Austrian border to Galicia as well. And though formally they were acting as Napoleon’s ally, as was prescribed in the Tilsit Treaty, their real goal was to prevent the Poles from taking too much of the Austrian-held territories.

So, to outwit the Russians prince Józef was taking Galician cities not in the name of the Duchy of Warsaw, but in the one of emperor of the Frenchmen. Like the proclamations were being made in the name of Napoleon, the eagles on the coats-of-arms replacing the Austrian ones were not Polish and French etc.

Lancers lead Austrian prisoners of war near Kraków in 1809, in front of Prince Józef Poniatowski, a photo of Stanisław Bagieński's painting

Then, in the outer theater of war on the 6th of July the French defeated the Austrians at the Battle of Wagram. And according Franco-Austrian truce signed five days later the land division was to take place along the line where the troops were at the time of receiving news of the truce, not at the time its signing.

The Austrian army leaves Wawel, a postcard based on the painting of Wojciech Kossak

And so began the race between Russians and Poles, to advance to as farther as possible.

In the middle of July both armies reached Kraków.

PRINCE JOSEPH'S ENTRY TO KRAKOW. A drawing by Jan Feliks Piwarski.

And there the clash of the interest took place.

Poniatowski approached the city from the side of St. Florian's Gate, but it turned out that the Austrians, wanting more comfortable terms of capitulation, had already let Russian troops into Kraków.

The Russians, namely the Cossacks of General Sievers, wanted to deny Poniatowski passage. But Prince Józef, as Dezydery Chłapowski recalls in his memoirs, "draw his broadsword and with together his staff galloped into the gate through the Cossacks". The Polish infantry followed its commander "in a double step <...> so that the Cossacks were pressed against the walls of the gate." Seeing this, Mariampol's hussar regiment, which was stationed at that time in the market square, make a decision to put up resistance and due to this, the whole Polish army was able to enter the city.

Michał Stachowicz, The entry of Prince Józef Poniatowski into Krakow on July 15, 1809

Then, as Ambroży Grabowski recalled, when prince Józef’s troops reached the market square, “in front of the church of St. Wojciech, the magistrate went out to meet the prince, to give him the keys of the city”.

Józef Poniatowski in the Cathedral after Kraków was taken from the Austrians, an image by Stanisław Tondos and Wojciech Kossak

Most probably prince Józef visited the Wawel cathedral during his sojourn in Kraków that time. (In a small voice: little did he know that in 8 years he’ll be buried there...)

And after exactly a month since the Polish troops entered Kraków, there was a ball arranged in the Cloth-hall, the image depicting it I have already posted here.

#Poniatowski#Jozef Poniatowski#józef poniatowski#1809#Galicia#Lublin#Sandomierz#Zamość#Kraków#Austro-Polish War#Konstanty Gorski#Michał Stachowicz#Stanisław Bagieński#Wojciech Kossak#Feliks Piwarski#Kajetan Koźmian#Dezydery Chłapowski#ambroży grabowski

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

U.S. President Joe Biden led tributes to 18th-century Polish General Casimir Pulaski ahead of commemorations marking the 245th anniversary of his death.

Alternatively known as ‘the Soldier of Liberty’ and ‘the Father of the American Cavalry’, Pulaski fought with distinction during the American Revolutionary War and is credited with saving the life of George Washington. In a lengthy statement issued by the White House, Biden wrote: “Today, we pay tribute to General Casimir Pulaski, a Polish immigrant who served alongside American soldiers in the Revolutionary War and made the ultimate sacrifice for our Nation.” Biden also poured praise on the Polish Americans who had given so much to America and the wider world: “And we honor the culture and contributions of all our Nation’s Polish Americans who follow his legacy, standing up for the cause of freedom at home and around the world,” he added. Continuing, Biden credited Polish immigrants for helping drive America forward: “General Pulaski’s story and service are just one example of how much Polish Americans have shaped our Nation’s history and our future. Our country’s Polish American communities have helped create new possibilities for all of us—leading in every sector, powering our economy, and enriching our culture.”

Touching on Poland’s critical support of Ukraine, Biden noted: “Since Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine, the people of Poland have courageously stood up for freedom, liberty, and justice, rallying around the Ukrainian people and offering them safety and light in their darkest moments.”

This unequivocal backing, wrote Biden, exemplified the Polish spirit: “No one knows better than the people of Poland that, in moments of great upheaval and uncertainty, what you stand for is important and who you stand with makes all the difference.”

Drawing parallels between Pulaski’s values and Poland’s own moral codes, Biden finished with a flourish: “Today, we celebrate General Casimir Pulaski, who decided to stand with our Nation to fight for our freedoms. And we honor all the Polish Americans, who continue to push our Nation forward and fight for a future based on our most fundamental values: dignity, liberty, and opportunity.”

Who was General Pulaski?

Born in Warsaw in 1745, Pulaski was christened Kazimierz Michał Władysław Wiktor Pułaski, a name that would be later Anglicized when he went into exile.

The son of Polish nobility, he embarked on a military career in 1762 and six years later served as one of the commanders of the Bar Confederation, an association of Polish and Lithuanian aristocrats who launched an uprising to curtail Russia’s influence over the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth.

Enjoying a reputation as a free-thinking, loose cannon, his heart often ruled his head. The historian and diarist Jędrzej Kitowicz described him as: “short and thin, pacing and speaking quickly, and uninterested in women or drinking.”

Instead, he devoted his energies to battle: “He enjoyed fighting against the Russians above everything else and was daring to the extent that he forgot about his safety in battles, resulting in his many failures on the battlefield,” added Kitowicz.

Despite these defeats, Pulaski was known as an adroit commander who masterminded such triumphs as the successful defense of Jasna Góra.

Even so, he enjoyed a distant and even fractious relationship with other commanders, and when Poland was partitioned in 1772, he fled westward, stripped of all titles after being implicated in a plot to kidnap Poland’s King Stanisław August Poniatowski (who had supported Russia’s suppression of the Bar Confederation).

In and out of French prison for debt, Pulaski’s life had seemingly hit rock bottom. This, though, would change when he met Marquis de Lafayette, a French nobleman fighting for George Washington’s Continental Army. Pulaski needed little convincing to join the American cause, and Benjamin Franklin personally wrote to George Washington to recommend his recruitment: “Count Pulaski of Poland, an officer famous throughout Europe for his bravery and conduct in defense of the liberties of his country against the three great invading powers of Russia, Austria and Prussia... may be highly useful to our service,” wrote Franklin. In actuality, he would prove more than just “highly useful.” Landing in America in June,1777, his knowledge of lightning guerilla tactics was invaluable, and he was even credited with saving the life of George Washington after a bold cavalry charge secured the safe retreat of the man that would become America’s first president. Hailed for reforming the cavalry, Pulaski led his unit on a string of victorious campaigns. His bravery, however, was his downfall. Leading a charge against the British in Savannah, he was fatally wounded by grapeshot and passed away two days later on board a brig called the Wasp.

His heroism has never been forgotten. In 1929, Congress passed a resolution honoring October 11, the date of his death, as General Pulaski Memorial Day. This is just one of many honors bestowed upon him. Celebrated via numerous parades and the subject of several statues and street names, Pulaski was made an honorary American citizen in 2009 by Barack Obama. That he remains relevant to this day has not been lost on Joe Biden: “General Pulaski dedicated his life to the pursuit of liberty—not just for himself or his country but for all of us.” To all intents and purposes, he remains the ultimate freedom fighter.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meet the contestants!

I thought I would give you a list of the actual contestants before the tournament starts. I have delineated my criteria in the pinned post, but just a quick reminder - below are all crowned rulers of Poland who held power single-handedly, as attested to by contemporary sources, and also Bona, excluding princes from Rozbicie Dzielnicowe:

Mieszko I

Bolesław Chrobry

Mieszko II

Bezprym

Kazimierz Odnowiciel

Bolesław Śmiały

Władysław Herman

Bolesław Krzywousty

Przemysł II

Wacław II

Władysław Łokietek

Kazimierz Wielki

Ludwik Węgierski

Jadwiga Andegaweńska

Władysław Jagiełło

Władysław Warneńczyk

Kazimierz Jagiellończyk

Jan Olbracht

Aleksander Jagiellończyk

Zygmunt Stary

Bona Sforza

Zygmunt August

Henryk Walezy

Anna Jagiellonka

Stefan Batory

Zygmunt III Waza

Władysław IV

Jan Kazimierz

Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki

Jan Sobieski

August II Mocny

Stanisław Leszczyński

August III Sas

Stanisław August Poniatowski

Car Aleksander I

Car Mikołaj I

askbox is open to propaganda or suggestions, but the bracket will be arranged by me, manually. may the best/most iconic monarch win!

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Michał Stachowicz (14 August 1768, in Kraków – 26 March 1825, in Kraków) was a Polish painter and graphic artist in the Romantic style.

His father was a printer, bookbinder and bookseller. In 1782, he was enrolled in classes at the Painter's Guild, where he studied with Franciszek Ignacy Molitor, a Czech painter working at the Royal Court, and Kazimierz Mołodziński (?–1795), a religious painter. In 1787, he became a Master in the guild. From 1817 until his death, he was a teacher at Saint Barbara's gymnasium and, for many years, was a member of the Kraków Scientific Society

In 1816, he received a major commission from Bishop Jan Paweł Woronicz [pl] to do wall paintings at the Bishop's Palace, which took two years to complete. Only thirty-two years later, they were destroyed by a fire. In 1820, he was given another major commission from the architect, Sebastian Sierakowski, to paint a mural at the Collegium Maius depicting the history of the Jagiellonian University

His best known works depicted contemporary historical events, many of which he witnessed, such as "Kościuszko's Oath on the Market Square" and "The Entrance of Prince Józef Poniatowski into Kraków". He also did genre scenes, portraits, and religious paintings; notably the Stations of the Cross at the Church of St. Casimir the Prince and images for two side altars at the church in Jangrot. He also worked as a lithographer and illustrated the Monumenta regum Poloniae Cracoviensia (Tombs of the Kings of Poland in Kraków)

-wiki

0 notes

Text

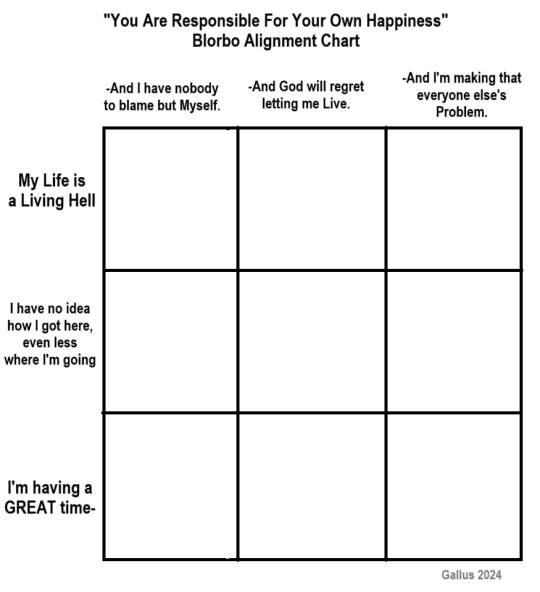

My life is a living hell and I have nobody to blame but myself - Jan II Kazimierz Waza

My life is a living hell and god will regret letting me live- Mieszko II Lambert

My life is a living hell and I'm making that everyone else's problem - Sigismundus II Augustus

I have no idea how I got here even less where I'm going and I have nobody to blame but myself - Stanisław August Poniatowski

I have no idea how I got here even less where I'm going and god will regret letting me live - Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki (that fucking cunt)

I have no idea how I got here even less where I'm going and I'm making that everyone else's problem - Sigismund III Vasa

I'm having a GREAT time and I have nobody to blame but myself - Jogaila (we call him Władysław II Jagiełło)

I'm having a GREAT time and god will regret letting me live - Bolesław II the Bold

I'm having a GREAT time and I'm making that everyone else's problem - Bolesław I the Brave, our first king ever

New Meme Alignment Chart came to me in a fit of Mania this morning. Have fun kids!

19K notes

·

View notes

Text

I wanted to start a thread: places, pieces of culture, literature, festivals, events in history, people from Eastern-European and Balkan countries (any ethnicity). I'll put a lot of countries in tags which I hope is okay.

Since for so long we were focused on western countries, we grew blind to the gems our countries are. We are tired of our politics and politicians but our countries are so much more than that.

Disclaimer: no nationalism here. You can love your country/culture without being a nationalist. LGBT friendly. No sexism. No racism. No xenophobia.

I'll start: although vampires are associated with Romania, their origins are Jewish and introduced to Polish and Ukrainian culture by rabbis living there.

The name vampire don't have origins in Polish or Ukrainian, tho. It comes from Serbian, because this belief traveled down to Serbia, Romania, Hungary, etc. In Polish it was upiór (closest translation to English would be ghoul), wieszczy (used mostly in Ukraine) or strzygoń. In polish words are flexible and differs when changing from singular to plural so I'll stick to English way. Also, since I am Polish, I'll probably stick to Polish versions of names which I am sorry for but sometimes it's difficult to google and translate such obscure subject.

These entities are related to cholera epidemic, so very places of origin of upiórs may be pointed as Tuchla (Тухля) and Sławsko (Славське).

As Łukasz Kozak from University of Poznań states, upiór could be of any gender (I will bring it up later) and at first it wasn't them drinking blood. People who killed someone believing it was an upiór, were drinking upiór's blood to be immunized to becoming one and to sicknesses in general. A lot of people killed "for being an upiór" were Catholic priests – one of the oldest reports of such event was judgment of priest Michał of Grabownica and it's dated on 16th century. Which leads us to another important note: upiórs were not in the legends only. There are court reports stating people were sentenced to death for not being human.

While upiór and wieszczy and strzygoń are the same name for one entity, it is believed first ones often were mischievous whole strzygoń often came "back" to the family they had when alive and acted very normal, farmed and could even conceive a child.

The last king of Poland, Stanisław August Poniatowski lived in Grodno (Гродна) after his abdication and his letters are full of reports of villagers killing each others for being upiórs. It was in 18th century, mind you.

Given the fact one of the most important polish author, Władysław Reymont, wrote a novel called "Vampire" (his stories were only about everyday life of villagers, since he was one himself, educated on his own, so it's a fantasy horror novel but taking a lot from his native folklore), published in 1911, it seems the belief in upiórs was strong in former Kingdom of Poland (Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania, but I'm not sure about these beliefs being strong in Lithuania) in 19th and 20th century.

What could be very interesting, upiórs had two souls, which made it possible to them to change their gender. Was that weird in Slavic folklore? Not at all. Huculszczyzna (ukr. Гуцу́льщина) folklore mention that boy can turn into a girl or girl turn into a boy if they stand on a place where the rainbow touch the ground:

"веселка (rainbow; here written in polish as wesełycia) drinks water and if at that exact place it touch the ground a boy stands, he will turn into a girl and if a girls stand there, she will be turned into boy (Rożeń Mały/Малий Рожин – place of origin of this legend).

#poland#polska#ukraine#україна#slavic folklore#belarus#lithuania#serbia#romania#polish folklore#ukrainian folklore#vampire#strzygoń#upiór#wieszczy#slovakia#czech republic#moldavia#croatia#jewish folklore#Slovenia#kosovo#bulgaria#česká republika#bosna i hercegovina#bosnia#hungary#folklore#eastern europe#balkans

275 notes

·

View notes

Photo

PL:

Pałac Ogińskich w Siedlcach

Pałac murowany został wybudowany przez Kazimierza Czartoryskiego przed 1730 r. Powstał na miejscu dworów drewnianych. W latach 1769-1770 gruntowny remont pałacu przeprowadził Michał Fryderyk Czartoryski, syn Kazimierza.

W 1775 r. Aleksandra Ogińska odziedziczyła pałac wraz z dobrami siedleckimi. W latach 1779-1781 przebudowała go według planów Stanisława Zawadzkiego. W centralnej części została dobudowana górna kondygnacja wraz z nową elewacją frontową. Po bokach dobudowano dwa skrzydła poprzeczne. Całość budynku nabrała charakteru klasycznego.

W pałacu - 20 lipca 1783 i ponownie w 1793 r. - gościł bliski krewny księżnej Aleksandry, król Stanisław August Poniatowski. Po swojej pierwszej wizycie król skorygował plany górnych apartamentów, co było związane z niedogodnościami, jakich doznał. Gościem w pałacu był również Tadeusz Kościuszko. Tworzyli tu również poeci oświecenia: Franciszek Karpiński, Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz oraz Franciszek Dionizy Kniaźnin.

Od 1774 r. księżna Aleksandra zaczęła wystawić w pałacu sztuki teatralne, odbywały się w nim również festyny dworskie, wieczory poetyckie i koncerty. Widowiska te uświetniały okolicznościowe uroczystości.

Po śmierci Aleksandry Ogińskiej w 1798 r. właścicielem stała się Izabela Czartoryska, która wymieniła dobra siedleckie na dobra rządowe na Lubelszczyźnie. W związku z tym od 1807 Siedlce stały się miastem rządowym, a pałac obiektem użyteczności publicznej.

Od 1921 r. pałac był rezydencją biskupa siedleckiego i siedzibą kurii diecezjalnej. W 1924 r. mieściło się w nim Gimnazjum Biskupie im. św. Rodziny, które funkcjonowało do 1939 r.

Od początku II wojny światowej do 1944 r. pałac był siedzibą Wermachtu, następnie zaś został spalony i odbudowany w 1950 r. Od tego roku służył jako siedziba władz i administracji państwowej i samorządowej.

W maju 2001 r. właścicielem pałacu stał się Uniwersytet Przyrodniczo-Humanistyczny w Siedlcach (ówczesna nazwa Akademia Podlaska), który w I kwartale 2005 r. rozpoczął projekt rewaloryzacji Pałacu Ogińskich.

EN:

Ogiński Palace in Siedlce, Poland

The brick palace was built by Kazimierz Czartoryski before 1730. It was built on the site of wooden manors, which were mentioned in 1698. In the years 1769-1770, a thorough renovation of the palace was carried out by Michał Fryderyk Czartoryski, Kazimierz's son.

In 1775, Aleksandra Ogińska inherited the palace and the Siedlce estate. In the years 1779-1781, she rebuilt it according to the plans of Stanisław Zawadzki. In the central part, an upper storey was added along with a new front elevation. Two transverse wings were added on the sides. The entire building took on a classic character.

A close relative of Princess Aleksandra, King Stanisław August Poniatowski, visited the palace on July 20, 1783 and again in 1793. After his first visit, the king revised the plans for the upper apartments due to the inconvenience he experienced. Tadeusz Kościuszko was also a guest in the palace. Poets of the Enlightenment also wrote here: Franciszek Karpiński, Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz and Franciszek Dionizy Kniaźn.

In 1774, Princess Alexandra began to stage plays in the palace, and court festivals, poetry evenings and concerts were also held there. These shows added splendor to the occasional celebration.

After the death of Aleksandra Ogińska in 1798, Izabela Czartoryska became the owner and exchanged the Siedlce estate for government property in the Lublin region. Therefore, from 1807, Siedlce became a government city and the palace became a public utility facility.

From 1921, the palace was the residence of the Bishop of Siedlce and the seat of the diocesan curia. In 1924, it housed the Bishop's Junior High School. Saint A family that operated until 1939.

From the beginning of World War II until 1944, the palace was the headquarters of the Wehrmacht, then it was burned down and rebuilt in 1950. From that year on, it served as the seat of state and local government and administration.

In May 2001, the owner of the palace became the University of Natural Sciences and Humanities in Siedlce (then called University of Podlasie), which in the first quarter of 2005 started the project of revalorization of the Ogiński Palace.

#pałac#siedlce#zima#poland#polska#palace#mazowsze#podlasie#akademia podlaska#uniwersytet w siedlach#ogiński

0 notes

Text

I can tell Mr Berry nothing more of our Russian war, but that it is most exceedingly unpopular, and that it is supposed Mr Pitt will avoid it if he possibly can. You know I do not love Catherine Petruchia Slayczar, yet I have no opinion of our fleet dethroning her. An odd adventure has happened. The Primate of Poland has been here, the King's brother. He bought some scientific toys at Merlin's, paid fifteen guineas for them in the shop, and was to pay as much more. Merlin pretends he knew him only for a foreigner who was going away in two days, and literally had his Holy Highness arrested and carried to a sponging-house; for which the Chancellor has struck the attorney off the list—but hear the second part. The King of Poland had desired the Primate to send him some English books, who for one sent The Law of Arrests. The King wrote, 'This is not so useless a book to me, as some might think; for when I was in England, I was arrested.’

Horace Walpole to Mary Berry, 10 April 1791 (Note accompanying reminds that no evidence of S’s arrest has been found.)

#Michał Poniatowski#Stanisław August Poniatowski#Polish history#18th century#catherine the great#Horace Walpole

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The battle of Zieleńce (1792)

On occasion of the battle of Zieleńce, which took place during the Polish–Russian War of 1792 (War in Defence of the Constitution) let me show you some images related.

Aleksander Orłowski "Prince Józef Poniatowski in the battle of Zieleńce”

The battle took place on the 18th of June, 1792. By that time the war has been going on for a month already, and since its beginning the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth Army had been in retreat. On the eve of that day, on the 17th of June, Poniatowski, the commander of the of the Kingdom of Poland's Crown Army, finally received the long awaited reinforcements. And the next day the Poles defeated one of the Russian formations of general Irakly Morkov.

Wojciech Kossak "After the Battle of Zieleńce" (Józef Poniatowski together with Tadeusz Kościuszko are reviewing the parade of Polish troops)

Besides Poniatowski other Polish commanders like Tadeusz Kościuszko, Michał Lubomirski, Stanisław Mokronowski and Józef Wielhorski took part on the battle.

Jean Pierre Norblin, “The battle of Zieleńce”

That victory over Russian was the first Polish one since John III Sobieski, and to honor it the king Stanisław Augustus created the War Order called Virtuti Militari. Prince Józef was among the first people decorated with it.

Star to the Grand Cross of Virtuti Militari which belnged to Prince Józef Poniatowski

#józef poniatowski#poniatowski#1792#Polish-Russian war#the battle of Zieleńce#aleksander orłowski#wojciech kossak#jean pierre norblin#tadeusz kościuszko#virtuti militari

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Józef Poniatowski’s family album.

Part II. Grandparents, uncles, cousins (or 3 Stanisławs, 2 Konstncjas, Kazimierz and Michał )))

This week let’s continue talking about prince Józef relatives. In the previous post on the topic I wrote (and showed portraits) of Pepi’s parents and sister. So today there will be images and some information about others.

Let’s start with the grandparents. (Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to find much about Poniatowski’s maternal ancestors, so this post will be about relatives from his father's side...)

This fancy gentleman is the father of prince Anrdzej and the progenitor of the family - Stanisław Poniatowski.

Portrait of Stanisław Poniatowski, unknown painter, 18th century

He was born in 1676, as a son of a petty nobleman from Lesser Poland. And died in 1762, having achieved the highest rank possible for a civil servants in the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth - the castellan of Kraków. (Speaking in modern terms Stanisław Poniatowski can be called a self-made man.)

Of course, the life of such a man was full of ups and downs. That is why telling you about him I would like to focus only on things, which IMHO had some similarities with the destiny of Stanisłasw’s grandson, prince Józef.

During the Great Northern War Stanisław took the side of the Swedish king Charles XII and the latter’s protégé - as a king of Poland - Stanisław Leszczyński. (On the other side there were Peter The First of Russia and August II of Saxony, who had been elected as a Polish king.)

To the misfortune of the first party, one of the decisive battles of that war, the one Poltava in 1709, was lost, but this wasn’t a reason for Poniatowski to turn his back on Charles. On the contrary, Stanisław then saved life of his suzerain, and after that help him to flee to Turkey. And remained faithful the Swedidh king to the very end, till Charles’ death 10 years later. (Although for this reason Stanisław had to spend all these years abroad, taking care of various matters of the latter.)

Marcello Bacciarelli, Portrait of Stanisław Poniatowski, after 1758, National Museum in Warsaw

And only after Charles passing away, Poniatowski went to Poland and asked pardon from August II. And having received it, remaining a faithful servant of that ruler till the Saxon king’s death in 1732.

During the next interregnum, however, Stanisław supported again the candidacy of Stanisław Leszczyński, the former protégé of Charles II. And only under the pressure of circumstances (one of his youngest sons, his namesake Stanisław, the future last king of Poland, was kidnapped by the adversaries of the opposite, Saxon party, to forced Poniatowski to join them) he switched sides.

As for Stanisław’s private life - it was also not without complications. In 1710 he married Teresa Jasieniecka, a widow of a Lithuanian nobleman Ogiński. But shortly the wedding it turned out that Teresa’s financial state was not so well as expected, instead of money she possessed debts only. And it looks like it was the reason for Poniatowski to leave her. (Some sources even say that the couple eventually divorced).

Anyway, whatever happened with Teresa later, in 1720 Stanisław seemed to be eligible again, because that very year he married again, this time to Konstancja Czartoryska.

Per Krafft the Elder: Portrait of Konstancja Czartoryska, circa 1768, National Museum Kraków

Being born circa 1700 Konstancja was about 20-25 years younger than Stanisław’s, but this didn’t prevent the the marriage from being successful. The reason might have been that, though for Poniatowski this was again a kinda “strategic marriage” (because the Czartoryski family was very powerful), the bride was really in love with her groom. To such an extent that she married him despite her father’s will.

Marcello Bacciarelli, Portrait of Konstancja Czartoryska, 18th century

And, in general, Konstancja was so stubborn and willful, that in the family she was called “Chmura gradowa” (hail cloud).

As an example of her adherence to principles there might be recalled the story of her son Kazimierz duel with Adam Tarło. First she forced Kazimierz to challenge Tarło - though even by the standards of that time the reason doesn’t seem justified enough. An then, when the shooting happened with no harm to both sides and young men reconciled, the mother made the son to challenge his former adversary twice. And that time the duel ended with a death, fortunately to her - not of her son.

And such a story was not a unique one. (And something prompts me that had Konstancja been alive in 1761, when her son Andrzej, prince Józef’s future father, was about to marry a Czech noblewoman Teresa Kinska, the princess Poniatowska might not have agreed to that union. But the latter died already in 1758, so it wasn’t hard for Andrzej to get agreement from his very old and ailing father...)

Now, let us move to the next generation of Poniatowskis. The most known of them (and who, btw, was the favorite son of his mother) is Stanisław Antoni. Because in 1763 he was elected to become the king of the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth (and, ascending the throne, changed his second name to “August”).

Johann Baptist von Lampi the Elder: Portrait of Stanislaus Augustus in a dressing-gown, between 1788 and 1789, National Museum in Warsaw

Do you remember that the second name of prince Józef was “Antoni”? Yes, he got it in honor of that uncle of his!

And later Stanisław August had a lot of influence on his nephew, taking care on young Pepi and his older sister Teresa after their father’s death in 1773.

But in my opinion it won’t be correct to call prince Józef the favorite of king Stanisław, the person whom the latter saw as his possible successor on the Polish throne. Why? Because there also was the oldest of Stanisław’s siblings children, the son of the above mentioned Kazimierz and the king’s namesake - one more Stanisław. (More about him - a little bit below.) And only for the short period from 1791, when that Stanisław withdrew from public life and emigrated to Italy, till 1795 Pepi’s candidature might have seriously been seemed as a possible royal successor.

Ok, now let’s look at Kazimierz. In addition to participating in that infamous duel the oldest of survived sons of the Poniatowskis was known for leading a rather riotous life. Having married a wealthy bride Apolonia Ustrzycka he had a lot of money and spent them freely and sometimes rather eccentrically. In his greenhouses, for example, there were grown... pineapples! And he also brought to Poland from Africa a bunch of monkeys (though all they died shortly because of the cold Polish climate (( )

Unidentified painter, Portrait of Kazimierz Poniatowski, second half of 18th century, Palace Museum in Wilanów

In his private life prince Kazimierz was also a real child of his time - he had several mistresses. And one of them he even drove around Warsaw naked - so that everyone could "see" her charms. (You see, prince Józef had people among his uncles to take examples from ))) And I must also mention, that Kazimierz had a loving affection for his nephew. And in the last decade of the 18th century, when Pepi was already living in Warsaw, the uncle willingly invited the nephew to his place and even supported him financially.

And despite that notorious style of life prince Kazimierz outlived all his younger brothers and died in 1800, being almost 80 years old.

And now a little bit information about Michał, the youngest of prince Józef uncles. He was destined by his parents for the clergy, and in the church hierarchy he “climbed” to the highest Polish rank - the Primate of Poland. (Though, as many sources state, prince Michal was a priest just in the spirit of his age - having mistresses and possible even illegitimate children.)

Marcello Bacciarelli, Portret of Michał Jerzy Poniatowski, National Museum in Poznań, 18th century

And the circumstances of his death in 1794, in the age of 57 years only, still aren’t clear enough. That was the time, as you may remember, of Kościuszko’s Uprising, and Michał was among supporters of the king and the latter’s pro-Russian politics. So, when the primate became seriosly ill and then died there appeared rumors, that that might have been a suicide, in fear for being hanged, as those members of Targowica Confederation who weren’t lucky to flee.

In relation with prince Józef I can name only one significant thing of Michał’s biography - it was who from him Pepi inherited Jabłonna village under Warsaw with its famous palace.

For the record I should also mention that the Poniatowskis-senior had also 2 daughters, Ludwika Maria and Izabela, but they didn’t seem to play significant roles in their nephew’s life.

And now let’s look at the third generation - Pepi’s cousins, children of prince Kazimierz.

This is the very prince Stanisław, whom I mentioned above:

Angelica Kauffman, Portrait of Stanisław Poniatowski (1754-1833), 1786

Very well educated and economically talented, he carried out a lot of reforms in his vast estates in Ukraine, and made these land prosper. Being interested in art, he founded a painting school in Warsaw. More than once a member of the Sejm, elected marshal of the knighthood of the Permanent Council, member of the confederation of the Four-Year Sejm and... not a popular figure among the the nobility (szlachta).

Because of the latter reason in 1790 there arose a conflict between prince Stanisław and his adversaries, after which the prince resigned from all his post and abroad.

Portrait of Stanisław Poniatowski (1754–1833), attributed to Johann Baptist von Lampi the Elder, 18th century

He settled in Italy, where he owned estates, and unlike his cousin Józef, never returned to public life.

As for Stanisław’s private life - well, it also looked like a suitable plot for a romance novel. The prince met his future wife in Rome, when he was already in his fifties. She was thirty years younger than him and... a wife of his neighbor.

Her name was Cassandra Luci, and she was a common woman, beaten by her cruel husband. And one day, trying escape from an attack, she knocked on prince Poniatowski’s door, was allowed to enter his residence, and stayed with the latter forever.

First, of course, Cassandra served in Stanisław’s residence just as servant, becoming the housekeeper. But soon she answered his feelings, and... by 1816 the couple had already 5 children - 2 sons and 3 daughters. And when in 1830 Cassandra’s husband died, Stanisław was finally able to marry her.

And all the Poniatowskis living now in France are descendants of this couple. Or, to be more precise, of their second son Joseph Michael.

Relating to prince Józef - it looks like his cousin Stanisław didn’t have much affection on him. They met a couple of times before Pepi moved to Warsaw in 1788, definitely had chances to see each other between that time and the year when Stanisław emigrated, but that’s all. And much more close prince Józef was with his other “probably” cousins - the sons of king’s mistress, Elżbieta Grabowska. (But this definitely goes out the topic of this post.)

So, let’s move to the last person of today’s article, prince Stanisław’s younger sister princess Konstancja.

Marcello Bacciarelli, Portrait of Konstancja Tyszkiewicz, nee princess Poniatowska, circa 1775

And, I have to admit, she didn’t play any significant role in Pepi’s life either. (Though her daughter, Anetka, might have had - but about the latter I will write later, when the time comes to publish next post of prince Józef women.) But the reason I am writing about this Konstancja now is that her husband’s surname was Tyszkiewicz, just like the surname of the Pepi’s sister Teresa’s husband.

If you ask me whether those two Tyszkiewiczs were relative, I would answer you that they were very distant ones, because last common ancestor was the progenitor of the Tyszkiewicz family, named Tyszka, who lived in the 15th century.

As for why the king decided to marry both his nieces to the Tyszkiewicz family - on this question I don’t either have an answer. But I can quote you a verse which was written in Poland that time:

Tyszkiewicza

Król policzą

Między bliskich swoje

Dał jednemu

Dał drugiemu

Swych synowic dwoje

(Translation: The king counts the Tyszkiewiczs among his relatives, he gave to one of them and to another two of his nieces)

And because of these two Tyszkiewiczs, and the fact that Anetka Potocka née Tyszkiewicz is sometimes called prince Józef’s niece (though in fact they were first cousins once removed) Teresa Poniatowska, Pepi’s sister is, in these cases, called her mother, which is not at all true. And eery time I write such a statement it that makes me cringe. That is why I felt I ought to write about Konstancja, for the people know that there was one more Mrs. Tyszkiewicz, and that she was Anetka’s real mother.

Well, that’s all for today. and I hope I didn’t make you much tires with untangling all these family ties? ))

#józef poniatowski#the poniatowskis#poniatowski#stanisław poniatowski#stanisław august poniatowski#polish history#konstancja poniatowska#kazimierz poniatowski#michał poniatowski

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prince Józef’s “frenemies”

Good day, dear friends, and let the topic of this week’s post be Józef Poniatowski’s “frenemies“ (or, in longer words, people from Poland and France - fellow countrymen and representatives of allies - with whom prince Józef wasn’t in good terms).

Yes, as any other man Poniatowski didn’t have good relations with each and every person. In his youth, for example, he was dislike by some people for the gallant lifestyle; in times when Warsaw used to be a Prussian provincial city Poniatowski and his close circle were criticized for preferring the French Theater to the one, where performances were played in Polish.

(Maybe be one day I’ll write more on the topic, but because most of you are interested more in Napoleonic epoch, let’s start today from people and events related to the Duchy of Warsaw).

So, the first conflict happened already in January 1807, when prince Józef was chosen over generals Dąbrowski and Zajączek to become the Director of War (in October of 1807 the position was renamed to the “Minister of War”) of the Duchy. And, if to have a look to biographies of both of them we’ll see that each had enough reasons to expect that the position would become his.

Jan Henryk Dąbrowski

Let us start with Jan Henryk Dąbrowski.

Unidentified Polish painter, Portrait of Jan Henryk Dąbrowski, 19th century

He was 8 years older (born in 1755) than Poniatowski. And, same as prince Józef, Jan Henryk grew up not in Poland, but in a German speaking country. In Dąbrowski’s case it was Saxony, where his father served in the Saxon Army. And Jan Henryk himself started his military career there.

In the beginning of 1790ies, however, Dąbrowski followed the appeal of Great Sejm and returned to his motherland, where participated both in Polish-Russian War of 1792 and the Kościuszko Uprising.

After the Third Partition of Poland general Dąbrowski turned his attention to France - the country which, having abolished its monarchy, was seen by many Poles as the only country who might have helped them. And there, indeed, with support of Napoleon Bonaparte, the Polish Legions were created.

Of course, Dąbrowski commanded only one of the Legions (among other commanders there were, for example, Karol Kniaziewicz and Józef Wybicki), but it was his name which was mentioned in the Legions’ anthem. So, when the Legions, where many a Poles joined hoping this would have brought freedom to their country, in 1806 finally entered the former Polish territory, it was more than expected that just general Dąbrowski would be made the head of the army of the future Polish country.

Jan Gładysz, Jan Henryk Dąbrowski's entry to Poznań, ci. 1809

But the choice, as we all know, was made for Poniatowski. (So, as you can see, Jan Henryk Dąbrowski' had enough reasons to have a grudge against prince Józef.) But I can’t help mentioning that when the situation was really serious, like in 1809 or 1812-13, both generals Dąbrowski and Poniatowski were able to forget their disagreements and to join their efforts in serving their motherland together.

Btw, there is one more thing (though a totally speculative one) I feel I must write about Dąbrowski.

As I wrote above, he participated in Napoleon’s German campaign of 1813, and in the battle of Leipzig itself. Furthermore, there, in Leipzig, there was present his second wife, Barbara, who, btw, was more than 25 years younger than Jan Henryk. (They married in 1807.)

Feliks Sypniewski, The wedding of Jan Henryk Dąbrowski and Barbara Chłapowska (fragment), 19th century

So, if imagine, for a moment, that not but Poniatowski but Dąbrowski would have been killed at Leipzig... and taking into account all the above-mentioned romantic background (and the fact that the Legions’ anthem is now the anthem of Poland)... who knows, a monument to whom would have stayed now in front of the Presidential Palace in Warsaw.

But history, as we know, knows no ‘what if’s. So let me finish this part with a shrt description of general Dąbrowski‘s later years. Becoming the commander in chief of the all remaining Polish forces soon after prince Józef’s death he followed Napoleon to Paris, but in 1815, after creation the Kingdom of Poland as a Russian satellite state offered his services to this new power. The proposition to become the Viceroy (Namestnik) of the Kingdom of Poland was made for him, but Dąbrowski declined it. At the end of 1815 he retired from military service, and three years later died in his estate in the lands which that time belonged to Prussia.

That was all about Jan Henryk Dąbrowski, and now let us switch to the person who did accept the proposition of becoming the Namestnik and who also was prince Poniatowski’s frenemy.

So, please meet the general Józef Zajączek.

Józef Zajączek

Anonymous painter, portrait of a general Józef Zajączek, 19th century

Being born in 1752 Zajączek was older even than Dąbrowski. And before 1792, when during the Polish-Russian war his path crossed with the one of prince Józef, Zajączek had a kind of military and diplomatic career behind him. He visited Paris and Istanbul as a member of Polish diplomatic missions. He fought in the War of the Bar Confederation, and for some time served in French Army. And though he supported the newly accepted constitution in 1791, he didn’t like the king Stanisław August himself.

And it looks like that from that antipathy towards Poniatowski-king Zajączek’s dislike for his namesake for Poniatowski-prince grew from.

But, apart from this, in 1792 there happened a real conflict between two Józefs (and not without “participation” of Stanisław August). Because when in summer of that year the Polish king, having decided that there was no more sense in fighting Russians, ordered his troops to capitulate, the Polish military chiefs weren’t ready to accept such a command at once (because after weeks of retreat the Polish Army that time finally began to overcome the Russians).

Access of Stanisław August Poniatowski in to Targowicka confederation July 24 1792

So, not wanting to surrender, some high officers decided they should go to Warsaw, kidnap the king and force him to cancel the shameful order. Józef Zajączek was among them. Józef Poniatowski was totally against it.

And though the kidnapping didn’t occur, two Józef’s animosity was flared up.

Like Poniatowski, general Zajączek participated in Kościuszko’s uprising in 1794. And like Kościuszko himself, he was captured. But caught he was by Austrians, and after a year only in prison - released.

Then Zajączek went to France, where he joined the French Army, in 1797 Napoleon recognized him as an active general in the French Service (Zajączek didn’t join the Legions, because many a Poles from there remembered him from the times of 1794 Uprising and blamed for the massacres the Russian troops did in Warsaw’s suburb named Praga).

So Zajączek served in French Army as a French general, participated in Napoleon’s Egyptian expedition, then in the War of the Third Coalition in 1805.

André Dutertre, portrait of a general Józef Zajączek during the Egyptian campaign, between 1798 and 1801

Next year, 1806, in the War of the Fourth Coalition, he was assigned to command one of the Legions entering former Polish territory, and then to create another legion from the Poles already there. So not surprisingly he as well expected to become the Director of War (the position was later renamed to “Minister“) of the newly created Duchy of Warsaw.

And when his longtime foe Józef Poniatowski got the position Zajączek was more than dissatisfied. He refused to obey Poniatowski’s orders, and wrote in answer:

I am a French officer, I have command over the Poles, because this is what the emperor wanted, I do not depend on you at all... I expect nothing from the Polish government, I owe everything to the French Emperor... I warn you once and for all that I do not want to have anything more with you to do...

However, like Dąbrowski, in 1809 and 1812 Zajączek had to subdue ambitions and cooperate with Poniatowski. But, in comparison with the former, Zajączek didn’t participate in 1813 campagne. Because was wounded in the battle of Berezina in November 1812 (Dominique Larrey had to amputate his leg) and then captured by Russians.

Fording the Berezina River by January Suchodolski, ca. 1859

What happened next? After being almost 2 years in prison Zajączek return to Poland, and in 1815 tsar Aleksander, crowned as a new Polish King, proposed him the post of the Viceroy. Which position the namesake of prince Józef hold more than 10 years, till his death in 1826. In 1818 he even got a title of prince from the tsar, so since that time he might also be called “prince Józef”.

Ok, and what about Zajączek’s private life? You’ll be surprised, but in this area there were some similarities between him and Józef Poniatowski. Because first Józef’s sweetheart, Aleksandra Pernet, was of a French origin (though she was born in Poland). And married when they met. But that’s all, because, in comparison with Henriette de Vauban Aleksandra was 2 years younger than her Józef. And, what’s more, Zajączek was able to help divorce her husband, and in 1786 these two were able to marry.

Louis-François Marteau, Portrait of Aleksandra Pernett, ci. 1780

And - can’t help but mention, Zajączek’s wife was known for her beauty, which she was able to keep till the very old age.

And we’ll move now to the next person, whom prince Józef was in bad terms with. Namely - general Michał Sokolnicki.

Michał Sokolnicki

And, in comparison with Dąbrowski and Zajączek, Poniatowski and Sokolnicki’s conflict happened quite late, in 1809.

Being almost a peer of prince Józef (born in 1760), Michał Sokolnicki participated both in Russian-Polish war, and in Kościuszko Uprising, was a member of the Polish legions, and transferred to the Army of the Duchy of Warsaw in 1807.

Jan Gładysz, portrait of a general Michał Sokolnicki, 1815

The problems started, as I mentioned before, during the Polish Austrian War of 1809. Because Sokolnicki, who participated in battles of Raszyn, Grochów, Góra Kalwaria and Sandomierz, and was decorated with the Polish Order Virtuti Military and the French Legion of Honour, still felt he was underestimated.

So in 1810 he asked for a leave - saying he needed to fix his health - and went to Paris. And when Sokolnicki didn’t return to Poland in time prince Józef had to remove him from the active service (in December 1811). Full of resent, Sokolnicki then joined the French service and, staying by Napoleon's side, intrigued against Poniatowski.

And it is highly probable that due Sokolnicki’s effort prince Poniatowski, in 1812, acquired the next (this time a French one) “enemy”.

And this “frenemy” was none other than... the Emperor’s own brother, Jérôme Bonaparte.

Jérôme Bonaparte

The youngest Napoleon’s brother (born in 1784) belonged rather not to prince Józef’s generation, but to the next one. And definitely wasn’t so military talented as the Emperor himself. And preferred luxury life style even on march, in the campain of 1812, when every minute and hour was crucial.

Sophie Lienard, portrait of Jérôme Bonaparte

So no wonder that part of the Grand Armeé Jérôme commanded allowed Russian troops to leave unscathed. But the responsibility for this, not without assistance of the above mentioned general Sokolnicki, was shifted to the shoulders of... prince Józef. (Why Sokolnicki needed this - well, it is highly probable he counted on Poniatowski’s dismission which would have made prince Józef’s position opened to Sokolnicki himself) And Napoleon - as diarists recall - did not accept any excuses and subjected prince Joseph's to very harsh criticism. Which, in turn, might have been the reason why Napoleon didn’t listen to Poniatowski after the battle of Smolensk, when the latter pleaded the emperor to turn the army south instead of going east.

But this is another speculation.

What I am pretty sure - though I have to admit I never read direct mentions about it - is that after such a military failure (and following tongue-lashing) Józef Poniatowski and Jérôme Bonaparte could not have been in good terms anymore.

That’s all for today, thanks for reading!

#Poniatowski#Jozef Poniatowski#Napoleon Bonaparte#Napoleonic Wars#dąbrowski#Jan Henryk Dąbrowski#Józef Zajączek#Michał Sokolnicki#jérôme bonaparte

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Polish duel during the battle of Smolensk

There is one more story related with the Poles and the battle of Smolensk I would like to share with you. And it’s about a duel.

And here are the duelists:

On the left there is Michał Grabowski, in August of 1812 he was a general, and in command of the 18th brigade of the Vth (Polish) corps of the Grand Armée. (One more interesting thing about Michał is that he was a son of Elżbieta Grabowska, a mistress of the last Polish king, Stanisław August Poniatowski. Some historian even state that Michał was a son of the king himself!)

On the right there is Grabowski’s subordinate, colonel and commander of the 2nd Infantry Regiment (at that time) Jan Krukowiecki.

There are different versions on how the quarrel between these two started, during the march to Russia. Either Krukowiecki, taking into account how little the combat experience of General Grabowski was, declined to obey commands of the latter. Another version is that the colonel, known for his sharp tongue, told publicly that he himself would accept Grabowski even as a corporal in his regiment.

Anyway, Grabowski challenged Krukowiecki, but because of the state of war their colleagues managed to persuade adversaries to postpone the duel till the end of campaign’s first battle. And this battle, as you all know, happened to be at Smolensk.

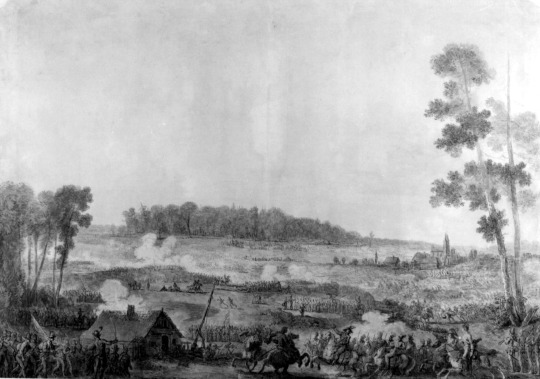

The battle of Smolensk (presumably - an illustration to the story from Napoleon.org.pl)

But then, when the battle started, one of the duelists changed his mind. According one version it was general Grabowski who, leading his men to battle called on colonel Krukowiecki to accompany him in the attack. The other version states that Grabowski first had not wanted to participate in the attack himself, sending Krukowiecki and his unit to fight, but, having been summoned by the colonel, had to join them.

Anyhow, both of duelists had to prove their bravery participating in the battle and their fate was thus sealed.

General Grabowski… was killed. He fell pierced with several bullets and "trampled so much by the enemy army that even his body was not found". Colonel Krukowiecki, in his turned, was heavely wounded, but successfully taken out of the battlefield. And lived for almost 40 years more, becoming a general himself (and participating in November uprising - but this is another story…)

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Józef Poniatowski’s family album

Part I. Parents and sister

Because in one of the previous posts I touched a little bit the topic of prince Józef relatives (closest and more distant ones) let’s now talk (and look at portraits) of his family.

To start I would like with his parents and sister.

Pepi’s father, Andrzej Poniatowski, was the penultimate son of Stanisław Poniatowski, the castellan of Kraków. He was born in 1734 in Gdańsk, where the Poniatowski’s resided during the time of the War of the Polish succession.

Having chosen the military career Andrzej had to join the Austrian Army, where he reach the ranks of general and then field-marshal.

Unfortunately, not very many portraits of prince Józef’s father survived till our days (maybe because of his early death, in 1773). So I was able to find only these two (which, withal, look like copies of each other):

Left: by unknown French painter, circa 1750-1775. Right: a copy from a pastel attributed to Louis Marteau, before 1770

Now let’s switch prince Józef’s mother. Of her portraits, fortunately, to our-days survived more.

Her name was Teresa Maria Herula countess Kinsky von Weichnitz und Tettau and she was 6 years younger than Andrzej.

A portrait of princess Poniatowska made by unknown author, circa 1770

Teresa Herula met her future husband in Vienna, and everything indicates that their union was a love marriage. (Or, at least, that Andrzej had some feelings for the countess von Kinski, because it was he himself who chose her as his wife to be, though the Kinsky’s were not very rich that time.)

A miniature portrait by unknown author.

After the wedding the Poniatowski’s stayed to live in Vienna, where both of their children, the oldest - daughter, and the youngest - son were born. But during Andrzej’s life they visited Poland several times.

Per Krafft the Elder, Portrait of Teresa Kinsky von Weichnitz und Tettau, 1767

However, though, as I wrote above, Poniatowski’s marriage was a love-match there were facts that might have indicated that not everything was fine between these two.

First, it might have been that Andrzej had an illegitimate son. At least, some diarists of that time thought that a person named Michał Michałowski was mentioned in prince Józef’s will not without a reason, that Michał was in fact Pepi’s half-brother.

Per Krafft the Elder, Countess Teresa Kinska Poniatowska, 1765

Ok, having children out of wedlock was kinda ok that times. But in one book I read that Teresa Herula, in her turn, also cheated on her husband. With Nickolay Repnin, that time Russian ambassador in Warsaw. (However, I wasn’t able the source of that statement so I am not sure whether we should believe it.)

Pierre-Joseph Lion, Teresa Poniatowska née Kinska, 1764 (Doesn’t it seem to you that this portrait of her looks like a pair to the second one of Andrzej?)

And what happened with Teresa Herula after Andrzej died? When she widowed the princess Poniatowska was only 30… But she never remarried again. And during her later life preferred to stay in Austria, where her family had real estates. And died in 1806, just a couple of month before Napoleon’s entrance to Warsaw, which brought so significant changes in her son’s life.

Ok, and now let’s look at portraits of Teresa the youngest. (As for her biography details - I mentioned a lot of them in one of the previous posts, so with your permission I’ll skip them this time. The most known portrait of the countess Tyszkiewicz can also be found there.

Maria Teresa Poniatowska as a teenager, unknown author

Fryderyk Dubois, Portrait of Maria Teresa Tyszkiewicz née Poniatowska, circa 1785

Portrait of Maria Teresa Tyszkiewicz, the 18th century miniature

4 notes

·

View notes