#meta wolff

Text

Intergenerational lag between generations of clones is most apparent in the variety and type of songs they make up and sing on Kamino. First Gen clones are the originators of the mnemonic tunes they used as study aids, which they then passed down to later generations. Second gens and younger created lullabies to sing to their younger siblings.

This means that after deployment, there is a slim knowledge gap between the Gen 1s and later generations. The concept and use of a lullaby may or may not have been known to the older generations. On top of that, training structures didn't have them interacting with younger generations of clones to the extent that any would need to be sung to sleep. After a series of changes in interactions with civilians, access to the Holonet (plenty of non-regulation uses of the Holonet on Kamino), and changes in training and interaction structure, you get gens came to know and produce their own lullabies. What's unique about the lullabies is that they make no mention of weaponry, warfare, battle, or soldiering of any kind. They have absolutely nothing to do with war. These are the only songs clones have whose main and sole purpose is to comfort.

#ch posts#meta#the clone wars#clone trooper headcanon#star wars#star wars the clone wars#captain rex#commander wolffe#swtcw#all the bros#rex heads a shiny singing a new song and he goes ?? wheres that from#familiar bc theres always a Way that clone songs work that regular songs dont#but he couldnt place it#clone culture

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

THOSE PANTS.

I NEED MORE CONTENT OF HIM WEARING THOSE PANTS. LIKE NOW.

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

wolffe being something of a fashionista and keeping up an impeccable and spotless armor during the clone wars vs. the armor becoming and remaining scratched and stained while serving the empire as wolffe no longer bothers to keep up a flawless appearance because of the chip's influence / because the wolfpack is gone / because plo koon is dead / because his batchmates are gone or AWOL / because there's no one left to remember what the armor's design and color stood for / because the war is over and the republic is gone but brothers are still dying / because something had to slip as his subconscious strains to not fall apart from the guilt, the losses, the grief, the fear, the desolation / because he's not himself / because he hasn't been himself since order 66 / because his mind and body was ripped from him and everything he'd fought and bled for crumbled to dust

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

workshopping clone selkies

Hmmm, how do we think a selkie au might work for the clones?

I don't think I'd want them to all be one thing, animal forms are different according to personality or w/e, but from a 'we are making these people into soldiers' cloning a selkie would not necessarily make sense? Like that's a huge weak spot right there.

Maybe the Kaminoans just took the skins from the start? Mean route would be to destroy them, but maybe they just have silos or warehouses full of animal skins. Some of them are really unique or rare - it's just good recycling to sell off the skins of clones who die.

Or maybe they carry their skins with them, there's a compartment in their armor/kit to put them in. Maybe they leave them on the ships while they go to battle? Maybe the skins are a huge secret and the clones go to great lengths to keep the knowledge from their commanding officers. A more gentle version of the Kaminoans having them - maybe the Jedi are in charge of their clones' skins, and there are halls in the Temple where they're carefully and reverently kept safe.

Is this just a blatant excuse for Palpatine to have a beautiful vulptex skin hanging in his office that he encourages all of his visitors to admire but for some reason makes all of the Coruscant Guard clones stiff and uncomfortable and one time when Plo Koon has the misfortune of having to meet with the Chancellor he's extremely surprised when Commander Wolffe sees the skin and goes absolutely fucking feral?

...MAYBE SO.

#tcw#tcw meta#clone troopers#commander fox#commander wolffe#there was some beautiful fanart of those two I meant to reblog but lost track of with them and their respective animals#all of the baby cadets: choose/are given names that have no relation to their pelts to keep something of themselves secret#fox and wolffe: lol#anyway if people have ideas i would love to hear em!#selkie clones would be a terrible idea but by god i wanna see it anyway

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Admittedly, I'm a little skeptical—okay, intensely skeptical—Clone Force 99 was too defective to get medical care?

They were a highly valued tactical unit that received some of the most specialized and highly qualified equipment. Tools and weaponry that the average Clone didn't have access to.

Commander Wolffe entirely lost his eye. It was rendered non-functional with Ventress's lightsaber. As I see it, it may come down to whether Wrecker's vision has sufficient acumen to perform his job (which is to be a human wrecking ball) or if it is a matter of Wolffe's specific job required him to have 20/20 vision (very likely, considering what we see the Wolf Pack do).

However, I don't believe it would be necessarily be common knowledge. Might be common and popular fanon.

Might be partly because Wolffe and his eye is a near and dear thing for me, as I did a completely unnecessary level of research into him. :wheeze:

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Tech-genda

I haven't written meta in a long time, but I just have so much to say about Infiltration and Extraction:

I'm sure there will be a ton of these, but my two cents as to how X is actually Tech (or Tex, as @nightfall-1409 calls him).

The POV of the show relied heavily on this new assassin, and that means he's a Special boy. Not like the assassin we saw in the trailer who died this episode arc. This is the boy we see on Pabu. That other assassin was a throwaway, maybe to get us off the scent.

And this is the big one for me, Tex fought like each of the OG Batch, including himself. Detonations, hacking, sniper rifle, vibroblade. His hobby of recording everything makes me think he either has eidetic memory, or he's an excellent copycat of what he's observed, especially something he would see on a daily basis.

Tex breaking out old tools. The pad on his arm almost like his old comm device/datapad. The grappling hook down the shaft. An evil little baby Marauder.

Falling and surviving (again). Maybe re-broke or simply re-injured that old broken femur. Conveniently, Tex hunches over a little so we can’t see how tall he is compared to other clones like Wolffe (they probably use the same model for all the Clone X assassins so this might be delusional on my part, but I think it would be a nice touch).

Also, the lighting this season is supposed to be a Big Deal, right.

This pulled back shot after Tex comes out of the hideout, he’s limping and injured, and there’s darkness all around him. He’s walking through this shaft of light, like a spotlight or a beacon, and I’m just like. Wow. Why such emotional shots for a random bad guy huh.

That was my same issue with the big season 3 trailer. When we get a shot of Clone X on Pabu, the music swells in an emotional, dramatic arc. You wouldn't waste that on some random guy. At least, I wouldn't.

Last but not least, Tex's reaction to drowning Crosshair, and Crosshair gently grabbing at his shoulder before he falls unconscious. He pulls back a little and pants heavily. I genuinely can't tell if Tex is reacting to the touch, Crosshair fading away, or both.

I also don't need to go into the imagery of Crosshair and Tech being mirrors of each other through the water, and that Tex is the Imperial agent that Crosshair failed to be. We've seen two methods of the Empire's control: reconditioning and the inhibitor chip. Seems the Empire is learning from its mistakes when it comes to the failing chips.

Note: There is much more I could go into, like despite the fact his voice is heavily modulated, Tex sounds exactly like his old self when he's grunting/panting. There's still so much to uncover, but I thought this was a nice start.

Sources: I write and have music/video editing experience, and these are things that make sense to me.

Addendum: Folks saying this is "bad writing" (an opinion, not a fact) are missing the point.

The question is not: Is it bad writing? The question is, can I masturbate to it? The answer, in this case, is yes.

Anyway that’s my Tech-genda thanks for listening.

#tbb#tbb spoilers#tbb season 3#tech#meta#clone x#tech meta#winter soldier tech#i know it's a lot to read but the end is worth it ;)

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

The House of Koon II by scent.2002 || Meta

Plo Koon, Duchess (my oc), and Commander Wolffe

#♝#dukeoftheblackstar#plo koon#duchess#oc#commander wolffe#wolffe#ρℓσ∂υ¢н#plo koon x oc#oc duchess#oc duch#star wars#the clone wars#tcw#tcw wolffe#jedi plo koon#jedi master plo koon

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Songs (tagged)

Hi everyone !!

Thanks for the several songs tagging during the summer @mctna2019 @rhaenys-queenofkhyrulzz and @pashminabitch :) (and so I'm sort of replying to all of you at once?)

I'm generally more into soundtrack/classics than songs and I don't really use spotify but make my own MP3 playlists for in the car (i'm so old), so instead of the usual spotify shuffle i'm giving you the top 5 instrumentals I listen the most to lately?

-Time of JungHyuk for Seri (CLOY OST / Nam Hye Seung, Park Sang Hee)

-River Flower / Garden of God / The Warrior / Kingdom / Sword of the stranger / Lost Castle / My Country / Battlefield, selfmade mix with my favourites cut bits (i prefer listening to the whole titles whenever I can, but without the quiet parts you can't really hear above the engine/traffic noises is just better suited and safer when driving without having to fumble with the volume all the time) (MCTNA OST, Rain Wolff - and then choose the tracks)

-The Day and My Love and… (TKEM OST 1 2 / Lee Geon Yeong, Gaemi)

-Moonlight Sonata I & III (Beethoven)

-No Time for Caution aka Epic Docking Scene (Interstellar OST, Hans Zimmer)

But if you actually want to know about actual SONGS, I'd go with those 'character meta-ish' songs in my MCTNA folder (which is the one I currently listen the most to, so...)

-Shake it out, Florence & The Machine

-Nothing, The Vassar Devils - thanks to that perfect @nubreed73 MCTNA vid

-Dynasty, MIIA (MCTNA vids https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e-inZf-p1dE and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fozuKNpv8sc)

-Train Wreck, James Arthur (MCTNA vid)

-Believer, Imagine Dragons (MCTNA vid)

(And special mention for the crackiest yet meta-ish crack vid I always come back to whenever I need a laugh (even though I cry at the end), even if I do not listen to the song in the car - again and forever, thank you so much for this golden one, always @nubreed73 :))

But to be honest again the actual SONGS i might have heard the most lately are those from our family Eurovision best of folder my kids didn't stopped asking for on repeat on our drive back home from holidays :)

-Alessandra - Norway - Queen of Kings 2023 (btw we voted for Lureen this year (because she was in our opinion the best singer (there is POWER in her voice, okay) - tumblr, don't hate us, please), but this one was a huge favorite song too. third (and atypical winner of the year in our hearts indeed) was Finland Käärijä - Cha Cha Cha)

-The Roop - On Fire - Lithuania 2020

-Italy - Mahmood - Soldi 2019

-Alexander Rybak - Fairytale - Norway 2009 (still such an iconic catchy tune)

-Iceland - Hatari - Hatrið mun sigra 2019 (each year we give a special award out of our own - 'atypical winner of the year')

(PS: any european pretending not to enjoy eurovision is a liar who lies :) (or not - anyone is free to like it or not of course i'm just joking, but in my family it is actually a year milestone tradition: that's how i grew up and that's what i passed on to my kids : gather all in front of the tv with snacks, and someone keeps the votes of everyone on a chart song by song:))

Tagging EVERYONE as usual and please tag me back so I can see it all :)

#mctna#my country: the new age#my country the new age#mostly#tags#personal#songs#music#i love you all#vids#@mctna2019#@rhaenys-queenofkhyrulzz#@pashminabitch#@nubreed73#eurovision

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every Noise Has a Note

“Every Noise Has A Note”: New Music and Leftist Radicalism

by Felix Klopotek

I.

In the 1960s and 1970s, New Music underwent a political radicalization analogous to its process of musical radicalization. It was a leftist radicalization, owing much to the times, without being completely absorbed in them. The concern of composers in that moment was serious.

Young composers, colleagues or students of Karlheinz Stockhausen or John Cage in the 1950s, developed—partially in open dissociation from one another—models of music, or, more exactly, music making, which broached social themes, and which conceptualized sound as an expression of the social. It was a matter of Totality: they abandoned the concept of the composer in favor of collective, folk, improvisational, and non-musical methods of working. Which means nothing less than that they attempted their own self-negation and abolition.

Groups like the Scratch Orchestra and AMM, Musica Elettronica Viva, Gruppo die Improvisazzione Nuova Consonanza, and composers and meta-musicians such as Frederic Rzewski, Eddie Prévost, Keith Rowe, Cornelius Cardew, Franco Evangelisti, Christian Wolff, and Takehisa Kosugi reflected in their musical praxis the point of interaction between composition as an aesthetic expression of critique and utopia and the social, the direct societal field of class struggle. The precariousness of this interaction consisted of the fact that, in its ultimate ramifications, the musical should be absorbed by the social, which was no longer seen as something separate.

Compositional praxis, musical praxis period, should abolish and transcend [aufheben] itself. The premises that determined what one understood as composition or performance should be thwarted to the point where it would be possible to understand a musical praxis as genuinely social.

“Every noise has a note,” the statement of AMM-percussionist Eddie Prévost, something between a demand and an observation, expresses this: that noise, which in the sense of the educated, polite bourgeoisie is non-musical, has a regularity underlying it and thus like music can be traced back to a creative ordering principle, which implies a mediation between “noise” and “music,” between noise and note. The activation/generation and derivation of a noise are determined by social praxis. Environmental noises are not to be considered as separate from the social actors moving within this environment.

A consequence of this is the transcendence of the separation between performer (composer/musician) and listener. Looking back in retrospect at this period in the 1960s, when AMM first surfaced with this demand, Prévost writes: “It is a tribute to our early supportive audiences that they could respond to our work and reinforce the validity of our activity; these were immensely valuable responses given the newness and uncertainties which accompanied the music.”[1]

However, in the moment where the social and the conceptions of the composer are shown to be disinterested and the working class is not inspired to undertake the final conflict by the deconstruction of the classical concert situation, in the moment where the jump into reality remains absent and the separation between avant-garde and audience is confirmed and reproduced ad infinitum, the concept of the “composer,” which should have been transcended, becomes reified.

The very thing that this generation of composers opposed—for example, that Stockhausen’s once revolutionary technique had fossilized into an invocation of god and proved to be well-suited for a domination-affirming de-subjectivization in music and the cult of the genius in the culture industry—repeated itself in the instant when the grounding of a postulated unification of musical theory and social praxis failed.

As the aforementioned composers returned to a classical form of composing and the larger groups dissolved themselves or, like AMM, hibernated in an almost mythically idealized method of production, the movement disappeared, and with it, the overall idea of the collective. Herein lays the reason why this part of the history of the New Left—particularly in the New Left’s own consciousness itself—is completely lost.

Concomitant with this, the protagonists of this movement, who in the meantime became established composers, have engaged in a critical settling of accounts with their past (without making the “long march through the institutions” with the rest of the 1968 generation) without, however, broaching the issue in such a way as to make it communicable with regard to current debates.

II.

“Does group direction, or authority, depend on the strength of a leading personality, whose rise or fall is reflected in the projected image, or does the collation of a set of minds mean the development of another authority independent of all members but consisting of all of them?”

AMMMusic liner notes

As familiar as the implied egalitarian attitude might seem today, having been established through Free Jazz or politicized pop groups—collective methods of working were not originally on the agenda for the New Music of the 1950s.

In Europe, the highest priority was the composition of music organized on a sufficiently rational basis. This praxis took up the tradition of Schönberg, whose twelve-tone music ordered tonal pitches in rows, that is, rationally. Schönberg’s post-war followers, the Serialists, went one step further: all tonal dimensions, such as duration, volume, and timbre, were to be ordered in rows, with the intent of creating an “integral work of art.”

One early critic who recognized the streak of delusional fetishism and barely concealed affirmation of dominance in this pretense was Adorno: “With curiously infantile faith, the material is invested with the potential to create musical meaning of its own accord. Astrological trickery asserts itself as the relations of intervals according to which the twelve tones are ordered are cheerlessly worshiped as cosmic formulas. The self-constructed law of rows thus becomes a veritable fetish.” [2]

As if to confirm this, Stockhausen blustered about “tuning in to the cosmic whole.” The publishing organ of the Stockhausen circle, Die Reihe (sic!), celebrated the dehumanization and de-subjectification of music in favor of a cosmic order: “In fact, such music has a cosmic character. Lost in reverie, galactic distances removed from the subjective sphere of emotion; in the alienating, new, in many ways terrifying forms of this music, forms arise which are not merely superhuman, but extra-terrestrial.”[3]

In principle, the role of the composer is thus devalued. The composer merely executes the logic of an external principle. However, at the same time, the composer can still celebrate his own genius, which has been endowed by the cosmic order, to which Adorno responds: “An order which proclaims itself is nothing but a cover-up for chaos.”[4]

Thus, the attempt that began with Schönberg as a planned, rational structuring of musical material and an order no longer subject to the whims of nature, and which in the ideal situation represented a method of working not based upon the repressive, mediating logic of valorization consummated the dialectic of enlightenment. Order degenerated into a second nature. “Having thus barely escaped “total” domination (National Socialism [F.K.[5]), the younger generation submitted to the total imperative of the ‘integral work of art.’”[6]

On the other hand, the libertarian variants of the American avant-garde, the works of the New York School centered around John Cage, Morton Feldman, Earle Brown, and Christian Wolff, also did not aim for the liberation of the interpreter, nor for improvisation. However, instead of embarking as God’s prophet on a Serialist ascension to heaven, in these compositions the composer bid farewell in a more sublime and ironic manner.

The New Yorkers developed models of indeterminacy whose guiding principle, for all intents and purposes, was the question of how controlling fanaticism and the intention to domination over musical material could be transcended. They attempted aleatoric procedures based upon principles of chance, which limited the influence of the composer to the setting of a framework and initial conditions. Cage’s most famous piece, “4:33’,” which specifies the non-playing of instruments for this period of time, means nothing other than this: that in the moment, when no musical activity emanates from the musicians, noises, coughs in the audiences, noise from the street, and the creaking of chairs attain a level of meaning that was previously repressed or ignored.

Another compositional principle consisted of the working out of graphic notation, which suspended the intended tonal control parameters of classical notation in order to leave a greater freedom of space for interpretation. Alexander Calder’s mobiles were an important source of inspiration in this context.

This withdrawal of the concept of the composer nonetheless raised a question which was not originally considered by Cage or Feldman: that of the freedom of the interpreter. The disappearance of the composer in no way meant the exaltation of the performer—improvisation was strictly prohibited. The music itself was not to be understood as a social experiment.[7]

Nonetheless, the New York School had “created” a vacuum. Whereas this vacuum would remain unoccupied in Cage’s further activity, in the sense of a winking Zen Buddhism, the occupation of this vacuum seemed obvious from the perspective of the other side, that of the actors (interpreters, musicians, audience). That is, an understanding of environmental sound not only as an immanent broadening of the concept of music but predominantly as something created by humans.

It was already evident in the overcoming of Serialism through Indeterminacy, whose activist component was the early Fluxus movement at the beginning of the 1960s, that this was not an exclusively musical process.

The concerts and actions that took place from 1960-1962 in the atelier of Cologne artist Mary Bauermeister, and which also established the Fluxus movement in Germany, were Happenings, which were loaded with a subversive intent: “There was a clear trend which predominantly determined the selection of repertoire and hardly admitted the works of the Cologne school (the circle around Stockhausen [F.K.]) although the atelier series was closely connected with its composers. It was pieces such as Cage’s ‘Cartridge Music’ and ‘Water Music,’ Busotti’s ‘Pearson Piece,’ and Paik’s action pieces, which stood at the spiritual center of the series—pure live works, which were to be experienced with all of one’s senses, and of an inescapable presence. The specifically un-American aspect of the atelier concerts was the integration of the Cage circle’s ideas with massively socially critical, dialectically, and ideologically flanked European thought, specifically that of the Cologne avant-garde (meaning the authors and critics Hans G. Helms and Klaus-Heinz Metzger [F.K.]). Cage’s Zen-influenced, Confuscianist works were misinterpreted as socially critical, or laden with a new framework of ideas.”[8]

Be that as it may, the enthusiasm for Indeterminacy was met with an increasing ideology-critical sense of discontent with one’s own musical socialization by former Stockhausen adepts such as Cornelius Cardew and Franco Evangelisti.

III.

Decisive triggers for the final breakthrough of collectivism were the developments taking place in Jazz, which by the mid-1960s at the latest had aggregated into Free Jazz.

Up to that point, Jazz and New Music had existed in mutual exclusivity. It is true that there were efforts made within “Third Stream Jazz” to connect to the formal language of twelve-tone music, but this fusion proved to be hardly productive—despite all the elegant music that came out of it. The mediation seemed too superficial, the alternation between the music of Schönberg and Thelonious Monk too indecisive. From the side of the composers, one spoke only disparagingly of Jazz, if at all. Cage and Feldman rejected improvisational attitudes. When the Fluxus movement protested against Stockhausen’s 1964 New York visit—“The first cultural task is to publicly expose and FIGHT the domination of white, European-US ruling class art! (…) Stockhausen, patrician ‘Theorist’ of white supremacy: go to hell!”—the actions had also been motivated by Stockhausen’s discriminatory comments about Jazz (the authenticity of which however, has not yet been sufficiently proven).

With Free Jazz, improvised music entered a phase that left behind the classical Blues and song schemas as foundations for improvisation. No longer bound by fixed harmonic-melodic material, and dissolving 4/4 time into a multi-directional pulse, the Free Jazzers won their own entry into noise as an integrated part of playing. This act of production was practiced and thought of as a decisively group process—music-making as a social act was already realized. Free Jazz (re-)introduced collective improvisation into Jazz.

In 1965, Cardew, 29 years old and, after a few years as an assistant to Stockhausen, now a teacher himself, looked for a young, open-minded Jazz combo that was ready and willing to realize his masterpiece, “Treatise,” an extensive, openly-structured graphic composition which emphasized the role of the performer. One could no longer speak of mere “interpretation.” More important for Cardew than the question of what the performers would play was that of how they communicated with each other and how they could collectively realize the graphically set element. As opposed to his teacher, Cardew was not concerned with the sacredness of sound but rather with the difficult construction of an egalitarian form of social cooperation. In the 1960s, he could only imagine this within the medium of advanced sonic research.[9]

Cardew found his Jazz performers in the group AMM, in which, for example, the Pop-Art painter and guitarist Keith Rowe had decided to stop tuning his guitar and began to conceive of it as an entirely new instrument, laid out on a table and mauled by steel springs, files, rubber balls, or contact microphones. Among the curiosities of this period was that AMM had the same management as and played concerts with Pink Floyd and was able to release their first record on a major label.

Cardew was so swept away by his encounters with the group, for whom reflections about the meaning of music were just as important as playing it, that he became a member and an adherent of improvisational praxis. At the end of the 1960s he wrote an ethics of improvisation. Counted among the seven virtues that a musician could develop were simplicity, integrity, selflessness, tolerance, preparedness, identification with nature, and acceptance of death (Cardew was a Buddhist and would later become a Maoist).[10]

AMM’s improvisations during this period were a harsh, inexorable racket: the intent was to prohibit the ability to determine which instrument was the source of a particular sound. The group performed as a group—even if they emphasized the importance of individual voices in the process of sound generation, they played no role in the larger picture. The group performed in darkened spaces, the concerts lasted a number of hours and incorporated long periods of silence.

Cardew was not an individual case: Frederick Rzewski, like Cardew, a virtuoso pianist and one-time prodigy, founded Musica Elettronica Viva (MEV) with dissident colleagues Alvin Curran and Richard Teitelbaum. Here, as well, the broadening of the concept of music to include noise crossed-over with improvisation.

Franco Evangelisti stopped composing altogether and called into life the Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza. Ennio Morricone was present, along with Rzewski. The group Ongaku and later the Taj Mahal Travelers operated in Japan, with the violinist Takehisa Kosugi, an important Cage interpreter and Fluxus activist, playing in both groups.

The differences between the various groups consisted in their way of dealing with the concept of the “work.” Whereas AMM took a principally anti-institutional attitude and accused the other groups of belonging to the establishment, Nuova Consonanza rejected this as out-of-bounds: the music remained a composition, even if it was developed in an impromptu manner in which all musicians participated with equality. MEV, on the other hand, mutated into a nomadic commune and integrated their everyday identity into the group and its performances, in which the audience was a participant.

Frederick Rzewski would soon detach himself from the practice of direct improvisation and begin to write political works. The pieces “Coming Together” and “Attica” (both from 1971) had as their thematic material the massacre committed by New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller and New York State Police against the inmate uprising at the Attica prison complex. Along with recited letters from the prisoners, Rzewski develops a dense but nonetheless catchy tonal sound surface. The compositions have agitation as their intent, without completely dispensing with the experience of improvisation: the works are realized by Jazz performers and contain extensive improvisational passages. Rzewski’s most well-known composition is his thirty-six variations on the revolutionary Chilean song “The People United Will Never Be Defeated” (1978). This is a work that demands a high level of virtuosity from the performer because Rzewski designed the variations as more and more complicated and elevated permutations of the original folk music material in homage to the creativity of the masses.

IV.

On July 1st, 1969, the Scratch Orchestra was founded. It was initiated at the suggestion of Cornelius Cardew and a number of other composers and students of Cardew’s. The list of composers, who count today among England’s most prominent, is still impressive: Michael Nyman, John White, Gavin Bryars, Michael Parsons, Howard Skempton or Brian Eno. What was decisive, however, was that the group was oriented explicitly toward non-musicians.[11] In the Orchestra’s constitution—it was actually called that—among other things the following is written:

A Scratch Orchestra is a large number of enthusiasts pooling their resources (not primarily material resources) and assembling for action (music-making, performance, edification).

Note: The word music and its derivatives are here not understood to refer exclusively to sound and related phenomena (hearing, etc.). What they do refer to is flexible and depends entirely on the members of the Scratch Orchestra.

[…]

Popular Classics

Only such works as are familiar to several members are eligible for this category. Particles of the selected works will be gathered in Appendix 1. A particle could be: a page of score, a page or more of the part for one instrument or voice, a page of an arrangement, a thematic analysis, a gramophone record, etc. The technique of performance is as follows: a qualified member plays the given particle, while the remaining players join in as best they can, playing along, contributing whatever thev can recall of the work in question, filling the gaps of memory with improvised variational material.[12]

At the inaugural meeting in Autumn of 1968, seventy musicians and activists met. Cardew solved the problem of a democratic organization of such a large heterogeneous group by giving everyone present a date on which he or she could perform a concert according to their own criteria. In its first year of existence, the orchestra played over fifty concerts. No other group dealt so seriously in a consistent manner with all of the implications that the young composers had deduced from their experiences with Fluxus, Free Jazz, and Hippie-Marxism.

Roger Sutherland, who came into the group as a non-musician and is active today in the noise-improvisation group Morphogenesis, describes the performance of one of many scores:

The score was called “Anima Two” and simply instructed: “Carry out every action as slowly as possible.” Everyone in the Orchestra could realize that however they liked. One sat at the organ and played a single chord from Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D-Minor. He held the chord for the entire duration of the performance, as if it would last forever. I interpreted the score by going from one end of the stage to another, in unbelievably slow motion. I had practiced that for weeks. One could hardly see that I was moving. (…) Cornelius Cardew sat there like a statue with his cello case, and he began to open the case very slowly. He took two hours to do that. Those were all very quiet activities. The only thing one could hear continuously was the static organ chord. There were also a few other sounds, but the main effect was that fifty people carried out unbelievably slow actions, so that the impression arose that time had somehow been abolished.[13]

These days, one is touched by the energy and enthusiasm with which such a large group was together able to realize concepts that were just as obvious as they were completely unworldly. How did they find the time and money?

The members probably did not waste a single thought on the notion that such concepts at some point would congeal into methods. The group broke up a few years later, but not because the composers wanted to impose their educated bourgeois claims against the non-musicians. Looking back, Roger Sutherland comments upon the creeping disintegration:

What happened was rather unexpected. Around 1971, Cornelius Cardew and a few others, particularly Keith Rowe and (the pianist [F.K.]) John Tilbury began bringing ideological and political texts and reading them aloud for hours on end. We all didn’t like that. That alienated the people who weren’t interested in politics. Cardew was about to convert to a sort of Chinese socialism. He thought that the most important tasks were political revolution and socialism. If musicians wouldn’t subordinate themselves to that, then they were counter-revolutionaries. That was rather primitive logic. Music, regardless by whom, whether by Cage, Stockhausen, or Cardew himself, that didn’t express a socialist ideology, and very emphatically, and which furthermore was capable of convincing people about socialism, he considered reactionary, negative, and so on and had to be rejected. And Cardew did the unbelievable thing of rejecting all of his previous work. He began writing songs and piano pieces that were transcriptions of Irish or Chinese revolutionary songs. With regard to harmony and rhythm, they were very simply constructed. The discussions about the function of music, whether music was political or not, split the orchestra. What happened, for example, was that we were now supposed to suddenly learn how to play instruments conventionally. There were even classes where one received instruction in rhythm or playing violin. I didn’t join the Scratch Orchestra for that. I wanted to experiment with sound, not play conventional music. I could have done that somewhere else.[14]

In 1974, the activity of the Scratch Orchestra petered out for good.

AMM also split. The quartet actually managed to disintegrate into an anarchist wing with Eddie Prévost and the saxophonist Lou Gare, and a Maoist one consisting of Rowe and Cardew. They still went on a tour of Europe together in 1973 but performed separately. Rowe and Cardew played noisy improvisations to songs and news broadcasts from Radio Tirana (!), which were supposed to reflect the alienation of the proletariat in everyday factory life. This was a bittersweet example of the decline of both the protest movement and the at one time so advanced musical praxis. Only in the late 1970s did AMM form as a united group once again.

Back to the Scratch Orchestra: the process of democratization was supposed to lead to the construction of a musical cadre party. That failed. Cardew, who in a dramatic essay accused his teacher Stockhausen of imperialism and was not above castigating himself for his earlier enthusiasm for Cage, also drew practical consequences. As a member of a British New Communist group, he provided musical accompaniment at demonstrations, agitated on picket lines, etc. When he became composer in residence of the Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin in 1973, he distributed leaflets against the Künstlerhaus and advocated instead for establishing a children’s polyclinic in its place.

In 1981, Cardew was fatally wounded in a traffic accident that was never solved. From the middle of the 1970s on, he played individual “secret concerts” with AMM, unannounced concerts under fake names. Cardew had, according to Keith Rowe, never given up his passion for the avant-garde

No recordings of the Scratch Orchestra are available today.[15]

V.

The politicization of new music failed due to its own radical standards. The social question took such a central place within the musical activity that the absence of the supposed logical consequence (revolution) robbed the music of its foundation. It became obsolete, entangled in ludicrous battles (Scratch Orchestra, AMM), or became kitschy (not dissimilar to current, silly Stockhausen performances).

What remains is the high level of engagement with the material. Precisely in the ruthless thematization and incorporation of the social field, which did not occur at the expense of the music,[16] there could be a path that leads beyond the dichotomy of music as social effect vs. music as technique. There’s a difference between understanding music in a truncated way as derived from concrete social circumstances or, as those composers did (of course failing to recognize their own privileged backgrounds) as a genuine social praxis.

It’s just as interesting to observe how the composers and musicians have engaged with their own survival. As a consequence of failure, AMM (namely Eddie Prévost) has conceived a “meta-music” intended to make getting through the winter possible.[17]

Every utterance, rustle and nuance is pregnant with meaning. To make a meta-music is to hypothesize, to test every sound. To let a sound escape unnoticed before coming to know what it represents or can do is carelessness. Each aural emission can be unlocked to show its origins and intentions. […] If humanization is our ultimate goal, “art for art’s sake” can only be justified as a tactical withdrawal. No sound is innocent—musicians are therefore guilty if they collude with any degeneration or demoralization of music.[18]

Just as before, the point is to decode sounds as social events and thus integrate them consciously into a social nexus. This consists, however, in the music-making collective itself—for lack of a real correspondence. “Meta-music” is music that reflects upon its own concrete conditions of emergence, through itself as a medium. A perpetuum mobile. “The reason for playing is to find out what I want to play.”[19] Any form of fixed pre-determination is forbidden: “Organizing sound limits it potential.” The music can only be realized as a spontaneous, common effort.

The concept of the social is only expressed through music—regardless of how emphatically AMM stresses this linkage, it no longer manages to become an expression that constitutes community, which is just the logical conclusion of the 1960s. Back then, improvisation, as an idea and as praxis, was taken as surface for the projection of universal utopias. The egalitarian collective of players anticipates an egalitarian society. Eddie Prévost probably wouldn’t assert anything else, ultimately; however, his own praxis is wiser, because it is the constant critical interrogation of one’s own activity, and thus it works out a set of rules that can only be applied to one’s own music.

As a listener, one can deduce what one wishes from that. These days, AMM, who no longer play as loud as they used to, but are just as breathtakingly lost in reverie, are celebrated as pioneers of industrial and ambient music, and there’s no trace of their former Maoism.

All deductions are one thing; the music is another. As improvised music, it remains fleeting, in principle unpredictable, without giving up its obligation to the movement in which it’s played and—beyond this—to the collective.

Thus, the subversive potential in the music has withdrawn into a theory that, because it is identical with its praxis, is hard to decode, utterly ensnared in its own decades-spanning history. As I said, very little remains for practical application.

But in contrast to thirty years ago, AMM would welcome this state of affairs.

[1] From the liner notes to the first AMM LP, AMMMusic, issued in 1966 and still available as a CD (Recommended Recordings). Prévost continues: “An AMM performance has no beginning or ending. Sounds outside the performance are distinguished from it only by individual sensibility.” AMMMusic is such a statement: the group does not play improvised music, or New Music (thus fulfilling no genre criteria), but rather music that develops the criteria for its own verifiability and transparency from within itself.

[2] Theodor W. Adorno, Philosophie der Neuen Musik, Suhrkamp: Frankfurt, 1958 (107).

[3] Quoted in Gottfried Eberle, “Neue Musik in Westdeutschland nach 1945” in Heister, Hanns-Werner and Dietrich Stern: Musik der 50er Jahren, Argument-Sonderband AS 42, Hamburg 1980 (47). Hanns Eisler also formulated a trenchant critique, writing, with regard to Stockhausen’s composition “Gesang der Jünglinge” (1953): “Stockhausen for example has created an electronic—or whatever you call it—piece of music over many years, after the section of the Bible, “Three Men in a Furnace.” In Luther’s translation, this Bible passage is a delightful piece linguistically, a report of prehistoric resistance. What does Stockhausen turn it into? The text is made intentionally inscrutable through manipulation of the tape, and thus the actual social meaning of this Bible passage is swept away. What remains is: ‘Great God, we praise you.’ It’s as if the musical squad of the ‘Königin Luise’ club were brought into the next village church by means of rocket aircraft” (quoted in Heister and Stern 78)

[4] Adorno, Philosophie der Neuen Musik 6

[5] [In various quotes used in the original German version of this text, Klopotek inserted brief parenthetical comments. These are denoted in the present translation by his initials in square brackets: [F.K.]—Tr.]

[6] Eberle, “Neue Musik in Westdeutschland nach 1945.”

[7] However, in this tradition there are also unmistakable, but very intricately rendered political statements. “King of Denmark,” a composition by Feldman from 1964 for solo percussion, demands extreme sensitivity towards the instrument on the part of the performer. The performer is not allowed to use mallets and can only work with his or her hands, arms, etc. This very quiet piece of music (standing in demonstrative contrast to rather loud percussion music) is an homage to the Danish king Christian X., under whose rule the Jewish population of Denmark was saved from the Wehrmacht by being evacuated to Sweden, and who publicly wore a yellow star as a sign of solidarity.

[8] Robert von Zahn, “Refüsierte Klänge. Musik im Atelier Bauermeister,” in Das Atelier Mary Bauermeister in Köln 1960-1962 (117). This volume provides a rather complete picture of the primordial soup of the cultural Left, which includes everyone from Adorno to Cardew, Bauermeister herself, Stockhausen, Jam June Paik, LaMonte Young, Klaus-Heinz Metzger, and Hans G. Helms.

[9] A performance claiming to be complete can be found on Cornelius Cardew’s Treatise album on the Swiss HatArt label.

[10] Peter Niklas Wilson Hear and Now: Gedanken zur improvisierten Musik, Wolke Verlag: Hofheim, 1999 (11).

[11] The American composer Christian Wolff—son of the legendary publisher Kurt Wolff, who emigrated with his family to the USA in the 1930s, where Christian, having just turned 16, met John Cage and joined his “school”—began to compose for non-musicians. The score of Stones (1968) consists exclusively of a poem, which in a few lines provides instructions on how sounds can be created with stones: “Make sounds with stones, draw sounds out of stones, / using a number of sizes (and colours); / for the most part discretely; sometimes in rapid / sequences. For the most part striking stones with / stones, but also stones on other surfaces (inside / the open head of a drum, for instance) or other than / struck (bowed, for instance, or amplified). Do not / break anything.” (From Prose Collection 1968-74). Interestingly enough, at the same time Cardew was also working on a piece, The Great Learning, that also contained (improvisational) passages played exclusively with stones. Concerning Wolff’s series of compositions Excercises, the performer Eberhard Blum writes: “For the performers, the point of orientation is the act of playing in unison, but they are free to decide about tempo, dynamics, articulation, the manner of playing, and the length of pauses, as well as, at any time, whether or not they want to play, i.e., about instrumentation. All of that is decided in the course of the performance, meaning that all of these aspects of the performance are improvised, other than the fact that playing in unison, regardless of how far it might be, is always a point of orientation to which a player must return when straying too far. In other words: every performer is free to the extent that he or she succeeds in time in acquiring the agreement of others for his or her own special manner of performance.” (liner notes to: Excercises 1973-1975, hat ART CD) In his work, Wolff contrasts “parliamentary participation,” which allows interpreters to be free in shaping the reduced compositional instructions, to the “monarchical authority” of the composer, which he wants to see abolished.

[12] Cornelius Cardew, “A Scratch Orchestra: Draft Constitution,” The Musical Times 110:1516, 125th Anniversary Issue (Jun. 1969): 617-619

[13] Quoted in Hanno Ehrler: Radikale Demokratie: Das Londoner Scratch-Orchestra in Musiktexte 75 (August 1998): 52.

[14] Quoted in Ehrler, p. 57

[15] At least, no authorized ones. An unwritten Scratch law states that issuing a record requires the approval of all living members of the group. That will never be the case—that’s at least one point on which the still-divided Scratchers agree (even disregarding the aesthetic implications of issuing a record—what does it mean to choose one concert, and not another, from the mass of recorded material—there are also legal issues: who gets the royalties? Ultimately, the works of the Scratch Orchestra and its composers are regarded by the (copyright) collecting societies as classical music, and the respective royalty payments to individuals—group and collective compositions hardly count at all—might be correspondingly high. Nonetheless, in the year 2000 the California label Organ of Corti issued the CD Cornelius Cardew/The Scratch Orchestra: The Great Learning. It was a reissue of an album that was released in 1971 on the classical label Deutsche Grammophon. The Great Learning, a reference to the classical Confucian canon, is a vocal work consisting of seven paragraphs. In each paragraph, a section of the Confucian canon is declared. The composition, which Cardew worked on between 1968 and 1970—three paragraphs were finished before the group was founded, so they cannot be identified with the praxis of the Scratch Orchestra, even if he dedicated them to the group—is regarded, along with Treatise, as Cardew’s masterpiece. However, The Great Learning is not exemplary of the work of the Scratch Orchestra. In that sense, the reissue, supplemented by a performance of the first paragraph from the year 1982, is more of a Cardew CD than a Scratch one.

[16] Even in cases where the music retreated into the background, as with Cardew, it was a radical step. He did not water down his avant-garde compositions with tonal elements but rather devoted himself completely to simple workers’ songs.

[17] Edwin Prévost, No Sound is Innocent: AMM and the Practice of Self-Invention, Meta-musical narratives, Essays. Essex: Copula, 1995. If one is not further disturbed by its pathos, this book can be recommended as an introduction full of rich material

[18] Ibid., 33f. Prévost has adopted this moralism from Cardew.

[19] From the liner notes to AMMMusic

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

For Mari:

What plot points would change due to the inclusion of your character in canon?

Besides your face/voiceclaim, who do you think would be cast as your character?

What fan-material would exist for your character in fandom?

Is your character the subject of ‘imagines’ or ‘x reader’ style blogs?

What is the wildest crackship you can imagine for your character, whether in-universe or in crossover?

META ASKS: If Your OC Was Canon

HI BBY💕 I will answer these for Mari as much as I can.

What plot points would change due to the inclusion of your character in canon?

Well obviously what happens to Rex in his life would change. He would have someone to go to for help after order 66 and someone who would always be with him for the rest of his life. He'd have kids, a little jedi son..he would've gotten to live a more full life than he was denied in canon.

Besides your face/voiceclaim, who do you think would be cast as your character?

Hmmmm...I'd really have to think on this because I just LOVE my faceclaim for Mari so much. Possibly Maya Jama could work. Overall vibe of her as a person is right hehehehe.

What fan-material would exist for your character in fandom?

Oh dude there'd be quite a lot I think. I think just based on how much she so deeply loves Rex people would be obsessed with them as a couple. But I wouldn't be surprised if people shipped her with Padme or other clones she's close with like Fox or Fives...or even ones she does not get along with like Wolffe.

Probably lots of pin up art drawn of her too because shes quite the dynamo of a woman and shes so outspoken I could see people wanting to draw her likeness quite a bit.

Is your character the subject of ‘imagines’ or ‘x reader’ style blogs?

HAHA yeah probably. She's just so pretty and sexy I could totally see her drawing that kind of attention.

What is the wildest crackship you can imagine for your character, whether in-universe or in crossover?

I said a little bit above but the wildest ones I could think of would be:

Mari and Padme - They work so well together I could see people liking this haha.

Mari and Wolffe - They are kinda like....enemies at first. They don't like each other but they're both super slutty....there's a very deliciously compelling story that could be told there.

Mari and Fives - Again because they're both slutty and charming and playful in the best way. They would've had a lot of fun together.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

there's surprisingly very little about clones that is determined by genetics. height, weight, fat/muscle distribution, stamina, and some aspects of mental fortitude definitely are, but a common flaw is for one to believe that anything a clone does or doesn't do, or thinks or doesn't think, is the direct result of genetic tampering. little to nothing is credited to the powerful force of upbringing. nurture. culture. ideology.

as a general rule of thumb, clones don't like fish. this isn't because there's a set of taste bud genes that the Kaminoans played around with, and it doesn't stem from Jango in particular. the clones don't like fish because they didn't grow up eating it, and they didn't grow up eating it (it is theorized, at least) because the Kaminoans themselves are vegetarian and eat a lot of seaweed. THIS is because the catastrophic event that wiped out most of their species also destroyed many of the prey they naturally fed on, forcing the remaining Kaminoans to subsist on more plant matter than they used to.

this is an example of unintended Kaminoan lifestyle influence on the clone's lives and interests. While the Kaminoan scientists most certainly brought in expert nutritionists, whoever was primarily in charge of building the menu would not have thought to add fish or fish products to the menu. this is the same reason why the majority of older generations of clones are lactose intolerant to some degree. Not only was Jango lacking the crucial gene, the Kaminoans would not have thought to supplement the clones' diet with dairy products because they themselves cannot digest it and the human species, while mammalian, gets weaned at about one and a half years old. That is the plan the Kaminoans followed. There are other, stronger sources of calcium that the Kaminoans put into the clones' diet to ensure proper bone development.

(in fact, the majority of clones' food was supplemented with nutritional additives rather than the nutrients being part of the meal itself, initially. Their diets are so strictly controlled that the Kaminoans would rather give the clones dried fruit flavored fiber sticks than fresh fruit. Fresh fruit was rare.)

Multiple things got more dairy and a wider variety of foods in general into the clones' diet:

Bounty Hunter and Drill Sergeant influence.

They brought parts of their cultures or personal influences to Kamino. They had special orders of the things they enjoyed, including icecreams, snacks, cheeses, etc. The "nicer" instructors would sometimes let a clone they liked sample a piece of food. This is also how it was discovered that every single clone was deathly allergic to the space version of a cashew nut (a flaw swiftly handled by the scientists via both allergen therapy shots for already-born clones and a change to the standard clone template).

2. Returning clone influence.

Clones coming back from deployment brought a plethora of goodies (illicit and not) with them. Foods, snacks, candies, miscellaneous ingredients, stories of what amazing meals could be had if you were savvy enough or adventurous enough lucky enough. There are rumors of a GAR galactic candy trading system that stretches all the way back to Kamino, though evidence of it is sparse. Even Captain Rex is reported to have brought back gummy worms when called to Kamino to give a training lecture to rising CCs. Though the bag was allegedly "family sized", it is unclear if the goods were actually shared.

3. Experimentation.

[This is actually canon lol] The Kaminoans found that clones were more enthusiastic about mealtimes and getting their calories in when the food actually tasted good and had more variety. Taking the previous two influences, the clones' diet on Kamino improved in both taste and texture -- but there's still no fish.

#ch posts#star wars#the clone wars#captain rex#fives#all the bros#clone wars#tcw#star wars the clone wars#swtcw#commander wolffe#commander cody#clone culture#star wars meta#kamino#headcanon#clone trooper#meta

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

EL CINE NAZI (V): EL TRISTE CASO DE JOACHIM GOTTSCHALK

PLACA DONDE MURIÓ

A lo largo de más de 100 años el mundo del cine nos ha dado numerosas estrellas, pero al mismo tiempo hemos visto casos muy desgraciados por diferentes causas, que han cortado de raíz la trayectoria de directores o actores: bien por accidente (James Dean, William Holden, Carole Lombard, Bruce Lee, Natalie Wood, en nuestro país Claudio Guerin Hill); bien como el final de la deriva de una vida sin límites que los llevó a la más absoluta ruina o al suicidio (James Whale, Jean Seberg, Robin Williams, Marilyn Monroe); bien por perecer asesinada como el triste caso de Sharon Tate o incluso el turbio caso en el que se vio involucrado Fatty Arbuckle. La represión política ha sido fuente de cárcel y exilio en muchos casos (más de 100 cineastas españoles se exiliaron en Méjico tras la guerra del 36 y más de 2000 alemanes marcharon a Norteamérica durante la etapa nazi). La Caza de Brujas en Estados Unidos significó también el fin de muchas carreras, cuando no la cárcel, de algunos directores y guionistas de Hollywood. Pero el caso que hoy nos ocupa es extremo por las circunstancias y el trágico final que tuvo.

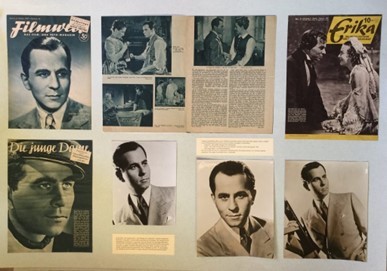

Al menos muchas de estas estrellas siguen disfrutando de la fama internacional y su nombre permanece en lo más alto del firmamento cinematográfico. Otros, sin embargo, que gozaron de gran fama durante unos años han perdido su estela y su nombre con el paso del tiempo. Este es el caso del actor a quien hoy dedicamos este capítulo y que tiene en su haber uno de los más tristes episodios de la historia del cine. Vamos a hablar de JOACHIM GOTTSCHALK.

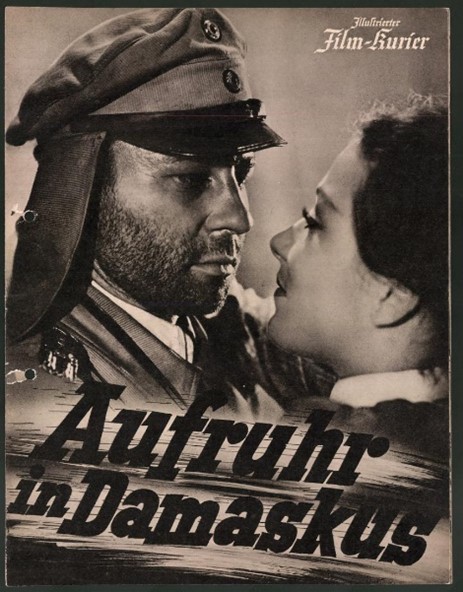

Seguramente este nombre no le diga absolutamente nada a nadie hoy día; sin embargo, su fama fue enorme dentro del cine europeo de los años 30 y especialmente en el teatro y el cine alemán. Joachim Gottschalk nació en Berlín en 1904. Pronto se inició y adquirió gran fama en el teatro y en la década de los años 30 participó en numerosas películas alemanas de gran éxito (le llamaban el Leslie Howard alemán). Formó pareja cinematográfica con la también famosa actriz Brigitte Horney en películas como Tú y yo, Alboroto en Damasco, La chica de fano o la dirigida por Arthur María Rabenalt en 1939, Escape en the Dark que fue prohibida tras la II Guerra Mundial. Su última película fue El ruiseñor sueco, de 1941.

Gottschalk era una estrella del cine nazi y recibía atenciones constantes por parte de la cúpula del poder. Lo que no podía prever era que una decisión suya de 1930 iba a convertirse en una gran tragedia. En 1930 Gottschalk se casó con la actriz judía Meta Wolff con la que tuvo un hijo en 1933. Con la llegada de los nazis al poder los actores tenían que entregar un certificado de raza aria lo que significaba la prohibición para la actividad profesional de su esposa. No obstante, los nazis mantuvieron una cierta relajación durante los primeros años con aquellos actores de fama que eran judíos o tenían familiares de esa raza (los nombraban “arios de honor”) y de esa forma el matrimonio pudo esquivar las leyes antisemitas. Gottschalk pasó del éxito en el teatro al cine en 1938 y no dejó de hacer películas hasta su muerte. Gottschalk y Horney eran la pareja de éxito en el cine durante aquellos años.

Pero en 1941 creyéndose amparado por su fama ante las autoridades nazis, Gottschalk se hizo acompañar por su mujer a una recepción cuando ya estaba en marcha la II Guerra Mundial. A la fiesta asistían numerosos jerarcas nazis que le fueron presentados a la actriz y cuando Goebbels se enteró que una judía había participado en esa reunión exclusiva de los nazis decretó que el actor debía divorciarse de su mujer; Gottschalk se negó y el ministro de Propaganda decidió que la actriz y su hijo de 8 años fuesen internados en un campo de concentración. Se presionó de nuevo al actor para que se separase de la actriz judía con la amenaza de en caso contrario no volvería a actuar, pero Gottschalk volvió a oponerse y se decantó por acompañar a su mujer y a su hijo al campo de concentración. La ira de Goebbels fue tal que decidió la movilización y militarización inmediata del actor en la Wehrmacht y el traslado inmediato de su mujer y su hijo al campo de Theresienstadt (sobre este campo existe un conocido corto documental con ese mismo nombre dirigido por Kurt Gerron en 1944 con el que los nazis pretendían dar una visión positiva ante el mundo de estos centros del horror).

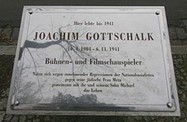

El 6 de Noviembre de 1941 cuando estaban en su casa esperando la llegada de la Gestapo y tras sedar a su hijo, Joachim y Meta abrieron la espita del gas de su cocina falleciendo los tres. El régimen trató de silenciar la muerte y las circunstancias de la misma y de hecho solo después del final de la guerra millones de alemanes se enteraron de la tragedia de su admirado actor y su familia. Lo que no pudo evitar el régimen, a pesar de sus amenazas es que al entierro de los tres acudiesen varios famosos profesionales del cine con Brigitte Horney, su pareja de varias películas, a la cabeza.

Dos años después de finalizar la guerra, Kurt Maetzig dirigió Marriage the shadows, un melodrama en el que se narra esta triste historia. Hoy, el nombre de Joachim Gottschalk no figurará en el olimpo de las estrellas del cine, pero por encima de su tragedia quedará para siempre la dignidad de esta pareja que pagó con su vida su oposición al fascismo.

Hasta aquí este somero repaso al cine del régimen nazi. Del III Reich hemos conocido una gran cantidad de historias tanto en ensayos, novelas de ficción y sobre todo en películas de muy variable calidad; hemos conocido el ascenso de Hitler al poder, su política de expansión, el desarrollo de la II Guerra Mundial y especialmente la Shoah. Pero es muy poco lo que hemos visto, por razones ética, del cine que se hizo en aquellos 12 nefastos años. Obras maestras del documental (Leni Riefenstahl) y grotescas películas antisemitas (Veit Harlan) es lo que mejor hemos conocido; sin embargo, por medio quedan cerca de 1.000 películas de todos los géneros a las se ha podido acceder en escasas ocasiones. Todo fue obra del régimen y de los profesionales que por diferentes circunstancias se quedaron en Alemania esos años (unos 2.000 se exiliaron) y que como Marco da Costa señala en el monográfico sobre este tema de Febrero de 2018 en Dirigido por… fueron: “Mujeres y hombres que con su trabajo formaron parte del imaginario colectivo alemán y cuya principal función fue la de entretener y adoctrinar durante 12 años al espectador de la época. Colaboracionistas pasivos, oportunistas, arribistas o simplemente advenedizos, todos, sin excepción, se pusieron al servicio de un tipo de cine que ayudaría en muchos casos a narcotizar al ciudadano alemán de todo lo que ocurría a su alrededor, desde el boicot inicial a los negocios regentados por judíos hasta su exterminio final en los campos de concentración”.

Deseemos por el bien del arte y sobre todo de la Humanidad que no vuelvan a darse las condiciones para que se repita esta historia.

3/6/2023

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

add it to YOUR Spotify playlist now...... fresh, smooth, rough, soulful, funked-up jazz-rock crossover guitar

#spotify#playlist#new#release#december1st#prebooking#fresh#rough#soulful#trippy#funkedup#jazzrock#crossover#guitar#retrovibes#twisted#grooves#spotifyuk#spotifynetherlands#spotifyusa#spotifydenmark#spotifysweden#spotifyfrance#spotifyspain#spotifyitaly#spotifycanada#spotifyaustralia#spotifyswiss

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

me: for many, many reasons, i don’t plan on actually using much mando’a in any mandalorian/tcw writing i might do

also me: same, however cody being the only one in fanon to get a mandalorian name is Extremely Rude and also i have an hour of my life to waste

#tcw#tcw meta#undoubtedly forgot some#tried to match up first letter as much as possible#but some were too fitting#also considered werde (darkness) or werdla (stealthy/invisible) for wolffe#bold numbers are non-canon#as for how the numbers were chosen#well#iykyk

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"¡LO QUE NO TE CUENTAN! Las Revelaciones de los Equipos en la Práctica del Viernes - Gran Premio Emilia-Romagna 2024 ¡IMPERDIBLE!" ¡Hola amigos! Hoy vamos a hablar de lo último en el mundo de la Fórmula 1. ¿Listos? ¡Arrancamos! Después de leer lo que los equipos tuvieron que decir sobre las prácticas del viernes en Imola, es obvio que todos están jugando un juego duro. Y a eso, yo digo - ¡vamos! #F1 Si miramos hacia Mercedes, Lewis Hamilton no parecía estar de humor festivo después de lo que él llama una 'dura' primera práctica. Sabemos que Toto Wolff y su equipo han estado trabajando incansablemente durante todo el invierno para mantener su supremacía, pero parece que las cartas podrían estar empezando a caer en otros lugares. Red Bull, por otra parte, viene pisando fuerte. ¡Hola a todos, estoy aquí, y como ven, este equipo no está jugando! Max Verstappen ha estado muy pendiente y no tiene miedo de mostrar su confianza. Pero chicos, no olviden su peculiar problemilla con el diferencial trasero. No es un tema de seguridad, pero esa fiabilidad es cuestionable. Mientras tanto, en el campo de Aston Martin, las cosas no podrían ser más diferentes. Están luchando con problemas de equilibrio en el monoplaza, el cual "se siente raro" según Lance Stroll. Habiendo estado en la parte inferior de las tablas durante todo el día, el equipo verde tiene mucho trabajo por delante. ¡Pero cuidado con los muros, chicos, no son tu amigo! Mi amor platónico, Alfa Romeo, está luchando con sus neumáticos blandos. El equipo tuvo un comienzo prometedor con Antonio Giovinazzi al volante (¡viva Italia!), pero su compañero Kimi Räikkönen se ha quedado atrás. El equipo necesita capitalizar en el ritmo que tiene su coche y trabajar en tener un buen bloqueo. Haas, por otro lado, más parece una obra de teatro griega. Nikita Mazepin ha estado hundido en su mediano ritmo mientras Mick Schumacher lucha valientemente. No pinta bien para el equipo americano, pero como siempre digo, la primera vuelta es larga en la F1. En resumen, los equipos de Fórmula 1 han estado ocupados como abejas en el viernes de prácticas en Imola. ¡Pero eso es lo que amamos de este deporte, no? No se trata solo de quién atraviesa primero la línea de meta, se trata de toda la emoción, la estrategia, los ajustes de último momento, el trabajo en equipo y la increíble destreza que se pone en cada vuelta. Recuerda, nadie dijo que la Fórmula 1 fuera un paseo por el parque. Y para terminar este post, voy a soltar una bomba polémica. #ControversialOpinion: Max Verstappen va a desbancar a Hamilton esta temporada. Sí, amigos, he dicho lo que dije. Verstappen tiene hambre, tiene velocidad, tiene un equipo detrás de él que está trabajando como un reloj suizo...y creo que esta podría ser su temporada. ¿Estás de acuerdo? ¡Hablemos en los comentarios!

0 notes

Note

hi, i was wondering if you might be able to help me sort out what is actually canon (or rather, what actually turns up in any kind of published sw media) about clone batches? like, do we have any indication who of the named clones was in a batch together? or how the batches on kamino worked?

Ooof heya!

I'm not too educated on that front either, however I'm pretty sure any and all Clone Batches talked about in fanfiction aside from Domino Squad and the Bad Batch are completely made up.

ie. the popular command batch, consisting of Cody, Wolffe, Bly and Fox (and sometimes Ponds) isn't actually canon as far as we know. They may be in the same batch but they also may not be.

I'll refer you to lumi @/gffa who is in my experience by far the most educated on all things star wars and kindly has put together many meta posts about various topics on their blog. You may find more about this if you search their tags or you could dive into their inbox and ask if they're willing to help you out more :)

0 notes