#mendez v westminster

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

When farmers Gonzalo and Felicitas Mendez sent their children to a local California school in 1945, school officials said they had to go to a separate facility reserved for Mexican American students. Angered by this discrimination, the Mendez family recruited other immigrant parents for a federal court case challenging the school segregation.

On this day 77 years ago, a Circuit Court made a final ruling in their favor — stating segregated education denied the Mexican American students their equal protection rights under the 14th Amendment.

The Mendez v. Westminster decision paved the way for the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case in 1954, and is a clear example of Mexican Americans fighting for their rights — and winning. 🙌🏽

#mendez v westminster#brown v board of education#california#14th amendment#fourteenth amendment#mexican americans#immigrant rights#mexican american rights#school segregation#segregation#history

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Big Lit Meets the Mexican Americans: A Study in White Supremacy

HarperCollins tells us: “We publish content that presents a diversity of voices and speaks to the global community. We promote industry and company initiatives that represent people of all ethnicities, races, genders and gender identities, sexual orientations, ages, classes, religions, national origins and abilities.” The New York Times proclaims its dedication to building a “culture of inclusion,” while the University of Arizona’s MFA program commits itself “to proactively fostering diversity and inclusion throughout its curriculum, admissions, hiring, and day-to-day practices.”

Some of these statements may reflect actual practices while others are simply corporate boilerplate. Whether they are sincere or not, the fact remains that most books agented, sold, reviewed, and distributed are mostly written by white people and are, moreover, mostly agented, sold, reviewed, and distributed by other white people. (In fact, the term “diversity,” as used in such statements, seems to reinforce rather than confront the notion that white, cisgender people are the norm and everyone else is a big, indistinguishable mass of otherness. But that’s a different essay.)

Big Lit is virtually a whites-only country club. Everyone knows this. The lack of racial diversity among the people who populate Big Lit is an open secret. The Big Five — Penguin Random House, Hachette, Macmillan, Simon and Schuster, and HarperCollins — is still where it’s at in terms of getting maximum exposure, resources and mainstream acceptance. Big Lit can consign to near invisibility the work of entire communities of writers it decides not to take up.

This essay is a kind of case study of the Mexican-American literary community, a community whose writers Big Lit rarely takes up. But I don’t mean to offer another lecture about Big Lit’s lack of diversity (well, not entirely). Rather, I want to examine how the ideology of white supremacy works to brand an entire population of nonwhite people — here, Mexican Americans — as inherently inferior to whites, how that message is reinforced by means both legal and extra-legal, how it seeps into literary culture, and, how, ultimately, literary culture (i.e., Big Lit) consciously or unconsciously views this population through the lens of those white-supremacist beliefs.

This ingrained and complex racism can’t be ameliorated by platitudes about diversity or tokenistic representations of “diverse” populations.

Part One

When Donald Trump called Mexican immigrants “rapists” during the announcement of his 2016 presidential bid, he was strumming a very old chord in white America’s consciousness. Since the mid-19th century, the denigration of Mexicans and, by extension, Mexican Americans has been an ongoing project of white America. The pivotal point was the US invasion of 1848 and the forcible appropriation of half the territory that comprised the nascent Mexico. Then as now, Mexico saw the war for what it was: an unprovoked and unprincipled land grab. As a Mexican newspaper at the time thundered: “A government […] that starts a war without a legitimate motive is responsible for all its evils and horrors. The bloodshed, the grief of families, the pillaging, the destruction. […] Such is the case of the U.S. Government, for having initiated the unjust war it is waging against us today.”

Fueled by the almost religious conviction that the United States was destined to occupy the entire North American continent, Anglo America embarked on the near extermination of indigenous people and the conquest of Mexico. From the outset, Manifest Destiny was a racialist doctrine.

As one historian observes:

By 1850 the emphasis was on the American Anglo-Saxons as a separate, innately superior people who were destined to bring good government, commercial prosperity, and Christianity to the American continents and to the world. This was a superior race, and inferior races were doomed to subordinate status or extinction.

America’s true motives were laid bare in a contemporary North American periodical, the American Whig Review: “Mexico was poor, distracted, in anarchy and almost in ruins — what could she do to stay the hand of our power, to impede the march of our greatness? We were Anglo-Saxon Americans; it was our ‘destiny’ to possess and to rule this continent — we were bound to it.” (Mid-19th-century Mexico was a troubled, unstable polity but still: If your neighbor’s house is on fire, is the morally appropriate response to break in and steal everything of value you can lay your hands on?)

At the end of the war, over 100,000 Mexicans were trapped on what was now the American side of the border. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo guaranteed that these captive people would become naturalized American citizens, with all the rights and privileges thereof, and that their property rights would be respected. Those promises evaporated almost as soon as the ink was dry on the treaty. The promised enfranchisement, it turned out, was only federal, not state citizenship. This ploy allowed the states that were carved out of annexed territory to limit citizenship to something called “white Mexicans.” As for the property right guarantee, Mexican property owners became bankrupt in American courts when fighting off American predators and squatters who would trespass and forcefully stay on their private property.

Arising at the same time was Western genre fiction, emerging first in the form of dime novels. This genre provided the most popular and widely distributed representations of Mexicans and Mexican Americans from the mid-19th century well into the 20th. Its practitioners included writers like Zane Gray, O. Henry, and Stephen Crane, as well as countless pulp writers. Film and, later, television perpetuated these representations and gave them even wider currency. Central to the Western genre was the theme of Mexican racial inferiority, which these narratives used to justify the invasion and conquest of Mexico; indeed one author called it, "conquest fiction."

Much of early Western fiction originated or was set in Texas, always a hotbed of particularly virulent anti-Mexican sentiment. Mexico had initially welcomed Anglo settlement in Texas, but the Anglos who arrived tended to be slave-owning Southerners with reactionary views about the purported inferiority of darker-skinned people. Mexico abolished slavery in 1829. This contributed to the Anglo-led secession of Texas from Mexico and the founding of the Texas Republic; basically, the white Texans wanted to maintain slavery.

Their attitudes toward their erstwhile Mexican hosts was summed up by Texas patriot Stephan Austin, who on one occasion described Mexicans as a “mongrel Spanish-Indian and negro race,” and on another as “degraded and vile; the unfortunate race of Spaniard, Indian, and African is so blended that the worst qualities of each predominate.”

Antebellum pulp Westerns with titles like Mexico versus Texas, Bernard Lile: An Historical Romance, and Piney Woods Tavern; or, Sam Slick in Texas created a set of Mexican stereotypes that prevailed well into the 20th century, among them the lazy peon, the evil bandido, and the licentious señorita. In these works most Mexican males are “segregated into two distinctly inferior types: peon servants and mestizo bandidos. As “half-breeds,” the mestizo bandidos are “a cut above the peons,” but “have no moral scruples. […] When the American heroes finally ‘unmask’ these poseur gentlemen and expose their wickedness, they either kill them or hurl them back across the color line into ‘brownness’ and disgrace.” The distaff side is represented by “Mexican woman […] graced with voluptuous figures but burdened by loose moral principles.”

Higher-brow publications like The Atlantic and Scribner’s Magazine were no less derogatory. An 1899 article in The Atlantic entitled “The Greaser” portrayed its Mexican-American subject as “the mestizo, the Greaser, half-blood offspring of the marriage of antiquity and modernity.” A travel piece in an 1894 issue of Scribner’s Magazine described the borderland between Texas and Mexico as “The American Congo”; the piece is a veritable encyclopedia of racist stereotyping, including this Trumpian observation: “The Rio Grande Mexican is not a law-breaker in the American sense of the term; he has never known what law was and he does not care to learn; that’s all there is to it.”

These caricatures of Mexican Americans were amplified and even more widely distributed as early moviemakers discovered the appeal of Westerns. Mexicans were, once again, cast as the dark-skinned foils to upright Anglo heroes as summarized by an author:

[F]ilm titles and advertising made open use of the word greaser, at least up to the 1920’s: The Greaser’s Gauntlet, The Girl and the Greaser, Broncho Bill and the Greaser, The Greaser’s Revenge, Guns and Greasers, or, bluntly, The Greasers. The artistic and cultural sensitivity of these films match their titles. If adventure stories, they feature no-holds-barred struggles between good Americans and bad Mexicans. The cause of the conflict is often vaguely defined. Some greasers meet their fate because they are greasers. Others are on the wrong side of the law. Others violate Saxon moral codes. All of them rob, assault, kidnap, and murder with the same wild abandon as their dime-novel counterparts.

These silent-era representations continued into the talkies.

Brownness, stupidity, laziness, cowardice, lawlessness, and sexual immortality: these became the signifiers of Mexicans in white America’s consciousness, reinforcing the notion that Mexicans are inferior to white people. This inferiority was race-based — that is, Mexicans were presumed to be inherently and in some inchoate sense biologically less intelligent, capable, and moral than white people.So deeply embedded are these cultural images that, after the death of the Western as a popular genre in books, movies, and TV, they simply shape-shifted into more contemporary versions.

Instead of the bandidos of yore, Mexican-American men transformed into gangbangers and drug dealers; the lazy peons became grocery-cart-pushing homeless people and hapless drug addicts; the flashing-eyed señoritas now tottered around suggestively on Fuck Me Pumps uttering heavily accented malapropisms. Often, however, these stereotypes don’t speak at all. In movies and on TV, you see brown people silently pushing laundry carts, pruning rose bushes, or stacking dishes into an industrial dishwasher, a sepia background against which the whiteness — and, thus, the superiority — of the real heroes and heroines gleams all the more brightly.

Part Two

Before Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, there was Mendez v. Westminster in 1946, the first federal court decision striking down school segregation. Let me explain.

California’s Orange County had set up “Mexican schools,” which all children of Mexican descent were required to attend from first to fourth grade. The ostensible reason was that they couldn’t speak English, but all Mexican-American children were forced into these schools regardless of their fluency. By the time the Mendez and five other families sued, these schools had 5,000 students. In the then-prevalent racial binary of black versus white, Mexicans were grudgingly considered “white.” This meant the plaintiffs couldn’t allege racial discrimination. Instead, they argued that the segregation of public schools impermissibly discriminated against their children based on ancestry and presumptive language deficiency.

In short, Orange Country’s segregation scheme wasn’t authorized by state law; thus, by extension, neither were other forms of segregation imposed on Mexican Americans in California by a comprehensive set of statewide Jim Crow–like laws. To summarize the situation: By the 1920s, many Southern California communities had established ‘Mexican schools’ along with segregated public swimming pools, movie theaters, and restaurants.” (On a personal note, I can testify that my mother remembers being turned away from a Sacramento public swimming pool sometime in the late 1940s because she was — and is — undeniably mestiza in appearance.)

From the mid-19th to the mid-20th centuries, whites used a combination of discriminatory legal and terroristic extra-legal tactics against Mexican Americans. Mexican Americans were disenfranchised, faced residential and education segregation, were denied the use of public facilities, and were in danger of being lynched. Yes, lynched — 571 ethnic Mexicans were lynched between 1848 and 1928; in addition, the Texas Rangers summarily executed at least another 500 Mexicans without trial.

As has repeatedly been the case, these discriminatory legal measures and extra-judicial assaults corresponded to high tides of Mexican immigration. In this time of history, Mexican immigration was between 1900 and 1930 - many, like my great-grandparents, refugees. Nativist whites such as Madison Grant, author of the influential The Passing of the Great Race, deplored this invasion by a “mongrel race.” White America’s attitudes toward Mexican immigration have always been both exploitative and ambivalent. On the one hand, these immigrants are useful because they serve as a cheap source of agricultural labor in the West; however, because they are members of an inferior “mongrel race,” they have to be closely monitored and firmly kept in place.

The ease with which bare tolerance could shift to active hostility was dramatically illustrated during the Great Depression. During this period, an estimated 400,000 Mexican Americans, 60 percent of them American citizens by birth or by naturalization, were forcibly repatriated to Mexico. The pretexts given were that Mexican Americans were taking scarce jobs away from white Americans and were a drain on government relief assistance. (Sound familiar?)

In a frenzy of anti-Mexican hysteria, wholesale punitive measures were proposed and taken by government officials at the federal, state, and local levels. Laws were passed depriving Mexicans of jobs in the public and private sectors. Immigration and deportation laws were enacted to restrict emigration and hasten the departure of those already here. Contributing to the brutalizing experience were the mass deportation roundups and reparation drives. […] An incessant cry of “get rid of the Mexicans” swept the country.

Mexican Americans never passively consented to their victimization by white Americans. Following the end of the Mexican-American War, they fought the unlawful seizure of lands guaranteed to them under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in American courts many being unsuccessful and losing their private property and homes to Americans who illegally squatted on their land and protested the decisions by California, Texas, and Arizona to limit citizenship to “white Mexicans.” In the 1930s, long before the establishment of the United Farm Workers, Mexican agricultural workers organized themselves into unions and went on strike in California, Arizona, Idaho, Washington, and Colorado; they were met with brutal suppression. “[w]ith scarcely an exception, every strike in which Mexicans participated in the borderlands in the thirties was broken by the use of violence and followed by deportations. In most of these strikes, Mexican workers stood alone, that is, they were not supported by organized labor.”

The 1960s and ’70s saw the birth of the Chicano Movement — emphasizing racial pride and resistance to racism. That movement also gave birth to a body of literature that is now acknowledged to contain many of the ur-texts that form the basis of Chicano/a and Latinx studies programs.

And now? Who are these Mexican Americans? While their numbers continued to be greatest in the western states, there are Mexican-American communities in every state in the union, with a significant presence in the Midwest and a growing presence in the South. In contrast to the aging white population, a 2007 survey revealed only six percent of “Hispanic Americans” to be 65 or older; the comparable percentage for whites was 15 percent. Thus, a brown workforce increasingly supports white retirees.

Contrary to the stereotype that most Americans of Mexican descent are recent immigrants, the majority of Mexican Americans are native-born. That percentage will only increase because Mexican immigration — even before Obama’s massive deportations and Trump’s war against immigrants — has been steadily decreasing, as a 2015 Pew Research Poll shows. That poll also dispels another stereotype, showing that almost 90 percent of native-born Mexican Americans are proficient in English. Moreover, Pew Research has also established that 83 percent of all Latinos and 91 percent of Latino millennials (including, of course, Mexican Americans) get their news in English.

The Department of Education reported a 126 percent jump in Latino students entering college between 2000 and 2015.

In short, Mexican Americans comprise a youthful, increasingly well-educated, largely native-born and English-proficient, aspirational community.

Yet, despite all this, Mexican-American representation in mainstream American culture, when it appears at all, remains either tokenistic, stereotypical, or both. In film, television, and books this emergent community is still largely ignored.

Part Thee

As part of my research for this essay, I looked at the course syllabi for a half-dozen courses in Latinx or Chicano literature from colleges across the nation, in order to see which Mexican-American works and writers scholars deem canonical. This is the list I came up with (virtually all these books were taught at more than one school):

Americo Paredes, George Washington Gómez (written in mid-’30s; published 1990)

Tomás Rivera, … y no se lo tragó la tierra/and the earth did not devour him (1971)

Rudolfo Anaya, Bless Me, Ultima (1972)

Sandra Cisneros, The House on Mango Street (1984)

Arturo Islas, The Rain God (1984)

Ana Castillo, The Mixquiahuala Letters (1986)

Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987)

Alejandro Morales, The Rag Doll Plagues (1991)

Helena Maria Viramontes, Under the Feet of Jesus (1995)

Norma Elia Cantú, Canícula (1995)

Reyna Grande, Across a Hundred Mountains (2006)

What most of these books have in common is that, with two exceptions, none were published by the Big Five or their predecessors; instead, almost all were originally published by small presses. While some were later picked up by Big Five publishers for paperback editions, most are still being kept in print by independent or university presses. Even The House on Mango Street, now generally recognized as a classic work of American fiction was originally published by Arte Público Press.

What this illustrates is Big Lit’s long history of ignorance or indifference to Mexican-American writers and the Mexican-American experience in this country. Yet to read any of these books is to experience a vision of America at once unique and familiar, for each in its own way tells a quintessentially American story. It’s just not a white American story. Yet very few Mexican-American writers find a place in Big Lit.

Big Lit is a very, very white place. White people overwhelmingly populate the Big Five; as the now-famous publishing diversity study by Lee & Low Books reported, 79 percent of people employed in the industry in 2015 were white and only six percent Latino.

A 2019 salary survey of the publishing industry undertaken by Publishers Weekly put the percentage of white employees at 84 percent.

Librarians, who are crucial to the sale and dissemination of literary texts, are also overwhelmingly white. A February 2013 editorial in The Library Journal entitled “Diversity Never Happens” observed that “Hispanics are some of the strongest supporters of libraries, and yet they continue to be thinly represented among the ranks of librarians.” ”The editorial cites statistics showing that, while Latinos/as are more likely to use libraries on a monthly basis than whites, only eight percent of the 118,666 credentialled librarians were Latino/a. A 2017 statistical study reports that “89 percent of librarians in leadership or administration roles were white and non-Hispanic.”

Similar demographic information for other realms of Big Lit appears to be unavailable. No one seems to be keeping any record of what percentage of the writers who are reviewed — or the reviewers who review — in The New York Times Book Review, Publishers Weekly, or Booklist, for example, are white. In a 2012 study of book reviews published by The New York Times, it was found that 90 percent of the books reviewed in 2011 were by white writers. White writers are vastly and disproportionately overrepresented both as reviewers and subjects of reviews in comparison to writers of color.

There are over 1,300 literary agents in the United States, most of them in New York, but I could find no statistics about their racial demographics. I did find an anecdotal study from the late 1990s, in an article called “Dearth of Hispanic Literary Agents Frustrates Writers.” The asserted that neither the literary agencies canvassed in The Literary Market Place nor the roster of agents in the Association of Authors’ Representatives listed a single Latino/a agent. The number is now likely greater than zero, but I have no doubt that the profession remains at least as white as publishing.

Similarly, there are, to my knowledge, no statistics about the racial composition of students and faculty at the many MFA programs around the country. There are, however, plenty of anecdotal accounts of how students of color are received in these programs. The essay “The Student of Color in the Typical MFA Program” powerfully summarizes these experiences. According to the essay, if a student of color objects to a racist depiction in a work by a white student, she or he risks being accused of censorship, or else the objection is dismissed as a political argument outside the bounds of literary analysis. Moreover, the student’s objection often triggers guilt or anger in white students and teachers because it challenges their cherished beliefs that they are not racist, and so they respond by branding their colleague a troublemaker.

The whiteness of Big Lit has practical consequences for Mexican-American writers. If virtually every agent, editor, book reviewer, and librarian is white, then such writers will have a much harder time finding representation, getting published, being reviewed and recommended. Therefore, there will be fewer Mexican-American voices in the literary culture. And this, in turn, means that there will be fewer counterbalances to the racist depictions of Mexican Americans in mainstream culture — portrayals that allow Trump and other white supremacists to continue to vilify a large segment of the American population.

White progressives in Big Lit may lament this situation, but they take no responsibility for the perpetuation of white privilege, if not white supremacy, in literary culture. Why? Because that privilege benefits them.

Part Four

The obvious issue is this: the white people who make up Big Lit live in a culture whose history and practice enshrines the belief that Mexican Americans are inherently inferior to whites, and fundamentally they’re okay with that.

The standard American university education continues to emphasize the primacy of white writers and their experience. To achieve a literary culture that truly reflects America’s multiracial society first requires an acknowledgment that Big Lit’s views regarding the putative universality of white experience are rooted in the ideology of white supremacy.

Other commentators have noted that the Big Five apply a double standard when acquiring and retaining writers of color. Writers of color aren’t allowed to fail the same way white writers are allowed to. If one book by a white author doesn’t sell, no one at the publishing house says they shouldn’t acquire any books by white authors the next season. But if a book by a Mexican, for example, doesn’t sell, the publisher may take its sweet time in “taking a risk” on another.

But aren’t disappointing sales a good reason to not continue publishing a particular writer or kind of book? That would be an acceptable explanation if the same standard applied across the board. To amplify the point above, however, if a white novelist from Brooklyn fails to make back her advance, that doesn’t mean her publisher won’t acquire other white Brooklyn novelists or even refuse to publish that particular author’s next book. Moreover, and here’s where the argument really falls apart, most books fail to make money, at least initially. The editor-in-chief at One World noted at the LARB/USC publishing workshop in July 2019 that 10 percent of books published by the Big Five support the remaining 90 percent. If most books are a risk, why is that risk disproportionately attributed to work by writers of color?

“Hispanics don’t read.” Whether a Big Five editor ever actually uttered those words, it is widely believed by the Latino/a community to be a sentiment Big Lit harbors about us. According to a nationally syndicated columnist after a day or two after a book's release, she got a call from a New York Times reporter asking her how well the book would sell. The reporter jumped in to the first question: ‘Why don’t Latinos read?’”

The Big Five, like the larger media culture, are not representative of the U.S. but of the limited tastes of the elite of Manhattan and certain areas of Brooklyn. These cultural gatekeepers — publishers, editors, agents — are simply unfamiliar with Latinos. A bias seeps into their decision making, based again on the unwarranted assumption that Latinos don’t read.

The notion that Mexican Americans and other Latinos/as don’t read is clearly rooted in assumptions of racial inferiority — e.g., immigrant, poor, less educated, less intelligent.

In short, the ideology of white supremacy is at the root of Big Lit’s “diversity problem.” The reason Big Lit doesn’t seek out, encourage, publish, and promote Mexican-Americans writers is because the people who work in it don’t really believe that Mexican Americans are the intellectual or creative equals of — or that their stories have the same value as those of — white writers.

Hey Big Lit: You think the Mexican-American experience can be expressed in a handful of stereotypes, most of which emphasize the intellectual and moral inferiority of Mexican Americans. While we’ve had to figure out white people, you’ve never had to think past your stereotypes of us. While we’ve been paddling upstream against the current of your white-supremacist assumptions, you’ve been lazily drifting along in them. You know nothing of our historical experience, while all of us have had the false narrative of white American triumphalism forced down our throats. And while you mouth your support for “diversity,” any such initiatives that you control will be, at best, tokenistic. Indeed, the concept of “diversity” itself may simply be an attempt on your part to deflect attention away from white-supremacist assumptions by turning the issue of race into a discussion about mere representation.

There can be no real diversity without a real and meaningful redistribution of power.

It’s almost impossible to imagine that the white people who compose somewhere north of 79 percent of Big Lit would ever voluntarily and actively agree to — and work toward — an industry where their percentage slipped below 50 percent. When it comes right down to it, Big Lit, you’re much more invested in maintaining your privilege, and passing it down to your white heirs, than in helping to create a literary culture that genuinely represents the fullness of the American project — warts, near-genocides, invasions, lynchings, and all.

Of course, we’ll keep on calling you out, because you do respond sometimes — out of guilt, if nothing else. Maybe you’ll publish a few more Mexican-American writers, review a book or two about the Mexican-Americans experience, hire a Mexican-American writer to teach in your MFA program, highlight the works of Mexican Americans in your bookstore when it’s not “Hispanic Heritage Month.” We will also will continue to remind you that you will find yourself listed among the collaborators, right up there with the Scribner’s Magazine editor who commissioned “The American Congo.”

Source

#🇲🇽#usa#united states#racism#discrimination against Mexicans#imperialism#colonization#colonialism#history#mexican history#mexico#mexican american war#remember the alamo#texas#movies#books#representation#tv shows#segregation#Mendez v. Westminster #california#lynching#texas rangers#white supremacy#eugenics#immigration#mexican revolutiom#great depression#arizona#idaho

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Invention of Hispanics: What It Says About the Politics of Race

America’s surging politics of victimhood and identitarian division did not emerge organically or inevitably, as many believe. Nor are these practices the result of irrepressible demands by minorities for recognition, or for redress of past wrongs, as we are constantly told. Those explanations are myths, spread by the activists, intellectuals, and philanthropists who set out deliberately, beginning at mid-century, to redefine our country. Their goal was mass mobilization for political ends, and one of their earliest targets was the Mexican-American community.

These activists strived purposefully to turn Americans of this community (who mostly resided in the Southwestern states) against their countrymen, teaching them first to see themselves as a racial minority and then to think of themselves as the core of a pan-ethnic victim group of “Hispanics”—a fabricated term with no basis in ethnicity, culture, or race.

This transformation took effort—because many Mexican Americans had traditionally seen themselves as white. When the 1930 Census classified “Mexican American” as a race, leaders of the community protested vehemently and had the classification changed back to white in the very next census. The most prominent Mexican-American organization at the time—the patriotic, pro-assimilationist League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC)—complained that declassifying Mexicans as white had been an attempt to “discriminate between the Mexicans themselves and other members of the white race, when in truth and fact we are not only a part and parcel but as well the sum and substance of the white race.”

Tracing their ancestry in part to the Spanish who conquered South and Central America, they regarded themselves as offshoots of white Europeans.

Such views may surprise readers today, but this was the way many Mexican Americans saw their race until mid-century. They had the law on their side: a federal district court ruled in In Re Ricardo Rodríguez (1896) that Mexican Americans were to be considered white for the purposes of citizenship concerns. And so as late as 1947, the judge in another federal case (Mendez v. Westminster) ruled that segregating Mexican-American students in remedial schools in Orange County was unconstitutional because it represented social disadvantage, not racial discrimination.

At that time Mexican Americans were as white before the law as they were in their own estimation.

The process would only work if Mexican Americans “accepted a disadvantaged minority status,” as sociologist G. Cristina Mora of U.C. Berkeley put it in her study, Making Hispanics (2014). But Mexican Americans themselves left no doubt that they did not feel like members of a collectively oppressed minority at all. As Skerry noted, “[the] race idea is somewhat at odds with the experience of Mexican Americans, over half of whom designate themselves racially as white.” Even in the early 1970s, according to Mora, many Mexican-American leaders retained the view that “persons of Latin American descent were quite diverse and would eventually assimilate and identify as white.” And yet “Spanish/Hispanic/Latino” is now a well-established ethnic category in the U.S. Census, and many who select it have been taught to see themselves as a victmized underclass. How did this happen?

In other words, a distinctive set of beliefs, customs, and habits supported the American political system. If the Cajun, the Dutch, the Spanish—and the Mexicans—were to be allowed into the councils of government, they would have to adopt these mores and abandon some of their own. It is hard to argue that this formula has failed. Writing in 2004, political scientist Samuel Huntington reminded us that

“Millions of immigrants and their children achieved wealth, power, and status in American society precisely because they assimilated themselves into the prevailing culture.”

Indeed, merely calling Mexican-Americans a ‘minority’ and implying that the population is the victim of prejudice and discrimination has caused irritation among many who prefer to believe themselves indistinguishable [from] white Americans…. [T]here are light-skinned Mexican-Americans who have never experienced the faintest…discrimination in public facilities, and many with ambiguous surnames have also escaped the experiences of the more conspicuous members of the group.”

Even worse, there was also “the inescapable fact that…even comparatively dark-skinned Mexicans…could get service even in the most discriminatory parts of Texas,” according to the report. These experiences, so different from those of Africans in the South or even parts of the North, had produced

a long and bitter controversy among middle-class Mexican Americans about defining the ethnic group as disadvantaged by any other criterion than individual failures. The recurring evidence that well-groomed and well-spoken Mexican Americans can receive normal treatment has continuously undermined either group or individual definition of the situation as one entailing discrimination.

It is incumbent on us to pause and note exactly what these UCLA researchers were bemoaning. Their own survey was revealing that Mexican-Americans’ lived experiences did not square with their being passive victims of invidious, structural discrimination, much less racial animus. They owned their own failures, which—their experience told them—were remediable through individual conduct, not mass mobilization. Their touchstones were individualism, personal responsibility, family, solidarity, and independence—all cherished by most Americans at the time, but anathema to the activists.

The study openly admitted that reclassification as a collective entity serves the “purposes of enabling one to see the group’s problems in the perspective of the problems of other groups.” The aim was to show “that Mexican Americans share with Negroes the disadvantages of poverty, economic insecurity and discrimination.” The same thing, however, could have been said in the late 1960s of the Scots-Irish in Appalachia or Italian Americans in the Bronx. But these experiences were not on the same level as the crushing and legal discrimination that African Americans had faced on a daily basis. That is why the survey respondents emphasized “the distinctiveness of Mexican Americans” from Africans and “the difference in the problems faced by the two groups.” The UCLA researchers came out pessimistic: Mexican Americans were “not yet easy to merge with the other large minorities in political coalition.”

Thereafter, militants from La Raza, MALDEF, and other organizations put pressure on the Census Bureau to create a Hispanic identity for the 1980 Census—in order, as Mora puts it, “to persuade them to classify ‘Hispanics’ as distinct from whites.”

The Hispanic category was a Frankenstein’s monster, an amalgam of disparate ethnic groups with precious little in common.

The 1970 Census had included an option to indicate that the respondent was “Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Central or South American, [or] Other Spanish.” But re-categorizing Mexican Americans and lumping them in with other residents of Latin American descent under a “Hispanic American” umbrella was a necessary move, Mora writes, because “this would best convey their national minority group status.”

The law states that “a large number of Americans of Spanish origin or descent suffer from racial, social, economic, and political discrimination and are denied the basic opportunities that they deserve as American citizens.” The very thing that defined Hispanics was victimhood.

IT IS SHOWN THAT THE HUMAN CATEGORY "WHITE" WAS BUILT UPON THE IDEA OF THAT BRITISH AS WHITE, CHRISTIAN, OF THEIR ESSENCE FREE,AND DESERVING OF RIGHTS AND PRIVILEGES FROM WHICH THOSE INSUFFICIENTLY BRITISH -LIKE COULD BE DENIED. JACQUELINE BATTALORA "BIRTH OF A WHITE NATION.

#hispanics#latina#afro latina#curvy latina#latin girls#latinx#sexy latina#thick latina#latino#kemetic dreams#brownskin#brown skin#mexican#mexicana#mexico#mexique#mextagram#white#black and white#white house#census data#censura#qsmp census bureau#u.s. census bureau#tumblr censure#the invention of the Hispanic#african#afrakan#afrakans#africans

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

🌈✨📚Childrens Books Banned For Inclusivity📚✨🌈

Separate Is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez & Her Family's Fight For Desegregation

By: Duncan Tonatiuh

"When her family moved to the town of Westminster, California, young Sylvia Mendez was excited about enrolling in her neighborhood school. But she and her brothers were turned away and told they had to attend the Mexican school instead. Sylvia could not understand why—she was an American citizen who spoke perfect English. Why were the children of Mexican families forced to attend a separate school?

Unable to get a satisfactory answer from the school board, the Mendez family decided to take matters into its own hands and organized a lawsuit. In the end, the Mendez family’s efforts helped bring an end to segregated schooling in California in 1947, seven years before the landmark Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education ended segregation in schools across America."

~Alice 🌌

1 note

·

View note

Text

Education

New Year, New U: A Look at New State Laws Affecting Education in 2025

New California state laws will protect the privacy of LGBTQ+ students, ensure that the history of Native Americans is accurately taught and make it more difficult to discriminate against people of color based on their hairstyles.

These and other new pieces of legislation will be in effect when students return to campuses after winter break.

Schools can’t require parental notification

Assembly Bill 1955, signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom in July, forbids California school boards from passing resolutions that require school staff, including teachers, to notify parents if they believe a child is transgender.

The Support Academic Futures and Educators for Today’s Youth, or SAFETY Act, also protects school staff from retaliation if they refuse to notify parents of a child’s gender preference. The legislation, which goes into effect on Jan. 1, also provides additional resources and support for LGBTQ+ students at junior high and high schools.

The legislation was created in response to the more than a dozen California school boards that proposed or passed parental notification policies in just over a year. The policies require school staff to inform parents if a child asks to use a name or pronoun different from the one assigned at birth, or if they engage in activities and use facilities designed for the opposite sex.

“Politically motivated attacks on the rights, safety and dignity of transgender, nonbinary and other LGBTQ+ youth are on the rise nationwide, including in California,” said Assemblymember Chris Ward, D-San Diego, author of the bill, in a media release. “While some school districts have adopted policies to forcibly out students, the SAFETY Act ensures that discussions about gender identity remain a private matter within the family.”

Opponents of the bill, including Assemblymember Bill Essayli, R-Riverside, indicated that the issue will be settled in court.

Accurate Native American history

Building a Spanish mission — out of Popsicle sticks or sugar cubes — was once a common assignment for fourth-grade students in California. The state curriculum framework adopted in 2016 says this “offensive” assignment doesn’t help students understand this era, particularly the experiences of Indigenous Californians subject to forced labor and deadly diseases from Spanish colonizers.

But supporters of a new law that goes into effect on Jan. 1 say that there are still grave concerns that the history of California Native Americans — including enslavement, starvation, illness and violence — is still misleading or completely absent from the curriculum.

AB 1821, authored by Assemblymember James Ramos, D-San Bernardino, aims to address this. When California next updates its history-social science curriculum — on or after Jan. 1 — it asks that the Instruction Quality Commission consult with California tribes to develop a curriculum including the treatment and perspectives of Native Americans during the Spanish colonization and the Gold Rush eras.

“The mission era of Spanish occupation was one of the most devastating and sensitive periods in the history of California’s native peoples and the lasting impact of that period is lost in the current curriculum,” according to a statement from the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians, one of the supporters of the legislation.

Teaching about desegregation in California

Another law that also goes into effect this year also requires the state to update its history-social science curriculum. AB 1805 requires that the landmark case Mendez v. Westminster School District of Orange County be incorporated into the history social-science curriculum updated on or after Jan. 1.

The case, brought in 1945, challenged four districts in Orange County that segregated students. The plaintiffs in the case were Mexican-American parents whose children were refused admission to local public schools. The case led to California becoming the first state to ban public school segregation — and it set a precedent for Brown v. Board of Education, which banned racial segregation in public schools.

The Mendez case is referenced in the history-social science curriculum that was last adopted in 2016 for fourth- and 11th-grade students, as well as the Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum, as an example of inter-ethnic bridge-building.

The Westminster School District wrote a statement in support of the law to ensure that the case is “properly recognized and rightfully incorporated into the state’s education curriculum.”

Protecting against hair discrimination

Assembly Bill 1815 makes it more difficult to discriminate against people of color, including students, based on their hairstyle. Although this type of discrimination is already prohibited by the CROWN Act, it has not extended to amateur and club sports.

The new legislation also clarifies language in the California Code, eliminating the requirement that a trait be “historically” associated with a race, as opposed to culturally, in order to be protected.

“(This bill) addresses an often-overlooked form of racial discrimination that affects our youth — bias based on hair texture and protective hairstyles, such as braids, locks, and twists,” stated a letter of support from the ACLU. “By extending anti-discrimination protections within amateur sports organizations, this bill acknowledges and seeks to dismantle the deep-rooted prejudices that impact children and adolescents of color in their sports activities and beyond.”

Protection for child content creators

Newsom signed two pieces of legislation in September that offer additional protection to children who star in or create online content.

The new laws expand state laws that were meant to protect child performers. Senate Bill 764 and Assembly Bill 1880 require that at least 15% of the money earned by children who create, post or share online content, including vloggers, podcasters, social media influencers and streamers, be put in a trust they can access when they reach adulthood.

“A lot has changed since Hollywood’s early days, but here in California, our laser focus on protecting kids from exploitation remains the same,” Newsom said in a statement. “In old Hollywood, child actors were exploited. In 2024, it’s now child influencers. Today, that modern exploitation ends through two new laws to protect young influencers on TikTok, Instagram, YouTube, and other social media platforms.” *Reposted article from EdSource by Diana Lambert on January 5, 2025

0 notes

Text

Wishing all the fantastic women out there changing the world! This year's theme is "Inspire Inclusion" as we celebrate diversity and empowerment.

- Renowned poet and civil rights activist.

- Known for her literary works addressing themes of feminism, race, and social justice.

- Advocated for Puerto Rican independence and women's rights.

- Instrumental in the landmark Mendez v. Westminster case, which challenged segregation in California schools in the 1940s.

- The case laid the groundwork for the desegregation of schools across the United States.

- Played a pivotal role in the Jones-Shafroth Act of 1917, which granted U.S. citizenship to Puerto Ricans.

- Advocate for Puerto Rican civil rights and suffrage.

- Award-winning actress, singer, and dancer.

- First Latina to win an Academy Award for her role in "West Side Story" (1961).

- Achieved EGOT status, winning an Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony Award.

- Central figure in the landmark Mendez v. Westminster case, challenging segregation in California schools.

- Advocate for educational equity and civil rights.

- First Puerto Rican woman elected to the New York State Assembly.

- Advocate for education, housing, and civil rights in the Bronx community.

- Physicist who worked for NASA.

- Recognized for her contributions to the development of the Space Shuttle program.

- The first Hispanic, and the first Latina to serve on the Supreme Court

- Advocate for the rights of defendants and criminal justice reform, and is known for her impassioned dissents on issues of race, ethnicity, and gender identity, including in Schuette v. BAMN, Utah v. Strieff, and Trump v. Hawaii

Do you know or have heard of some of these amazing women? Did you know some of them were Puerto Rican?

Please note that this content is sponsored by Adobe Express!

#PuertoRicanWomenLeaders

#InternationalWomensDay

1 note

·

View note

Text

Yesterday was the first day of Latin@ Heritage Month 2023!! It was also the kickoff for our Latin@ Leaders Coalition Latin@ Heritage Month Speaker Series! Thank you to everyone who came to our event! It was great to be in community with everyone while celebrating our wonderful culture, heritage, and amazing civil rights leader! A shout out to our coalition members! Everyone worked really hard to get this off the ground, I am proud to be amongst committed and passionate leaders changing the world!

For the next month we will host a different speaker or two every Friday night with the exception of the last week of September. This week we hosted the wonderful Señora Sylvia Mendez. We also had delicious Mexican food catered and sponsored by Celia's Mexican Restaurant in San Mateo, DJ El Mago on the turntables during cocktail hour, the super talented students of SSFUSD Alma de Mexico Ballet Folklórico.

Señora Sylvia Mendez is a Civil Rights Activist and retired nurse who along with her parents fought against the segregation and discrimination of Mexican students in the schools in Westminster: Mendez v. Westminster. In 1946 federal court ruled in favor that the school segregation of Latin@ children was unconstitutional. Mendez vs Westminster paved the way for Brown vs Board of Education. In 2011 President Barack Obama presented Señora Sylvia Mendez with the Medal of Freedom.

Next week 9/22 at the San Mateo Performing Arts Center, 5:45 p.m. we will host, Founder and CEO of DREAMers Roadmap, Sarahí Espinoza Salamanca, and Executive Officer of IXL, Inc. Dr Richard Carranza. Food will be catered by Cuban kitchen in San Mateo, DJ El Mago will be on the turntables, and a performance by La Cumbiamba Colombiana!

🎉🎉🎉🎉🎉🎉🎉🎉🎉🎉🎉🎉

¡¡Ayer fue el primer día del Mes de la Herencia Latin@ 2023!! ¡También fue el inicio de nuestra serie de oradores del Mes de la Herencia Latina de la Coalición de Líderes Latinos! ¡Gracias a todos los que vinieron a nuestro evento! ¡Fue lindo estar en comunidad con todos mientras celebramos nuestra maravillosa cultura, herencia y nuestro increíble líder de derechos civiles! ¡Un saludo a los miembros de nuestra coalición! Todos trabajaron duro para que esta serie se realizará. ¡Estoy orgullosa de estar entre líderes comprometidos y apasionados cambiando el mundo!

Durante el próximo mes, tendremos uno o dos oradores diferentes todos los viernes, a excepción de la última semana de septiembre. Esta semana tuvimos la maravillosa Señora Sylvia Méndez. También tuvimos deliciosa comida mexicana patrocinada por el restaurante Mexicano Celia's en San Mateo, DJ El Mago tocó la música durante la hora de comer, los súper talentosos estudiantes del Ballet Folklórico Alma de México del SSFUSD bailaron.

La Señora Sylvia Méndez es una activista de derechos civiles y enfermera jubilada que junto con sus padres luchó contra la segregación y discriminación de los estudiantes mexicanos en las escuelas de Westminster: Méndez v. Westminster. En 1946, un tribunal federal falló a favor de que la segregación escolar de los niños latinos era inconstitucional. Méndez vs Westminster le brindó el camino a Brown vs Junta de Educación. En 2011, el presidente Barack Obama entregó a la señora Sylvia Méndez la Medalla de la Libertad.

La próxima semana 22/9 en el San Mateo Performing Arts Center, 5:45 p.m. tendremos a la fundadora y directora ejecutiva de DREAMers Roadmap, Sarahí Espinoza Salamanca, y al director ejecutivo de IXL, Inc., el Dr. Richard Carranza. La comida será patrocinada por el restaurante Cuban Kitchen en San Mateo, DJ El Mago estará tocando música y ¡una actuación de La Cumbiamba Colombiana!

0 notes

Text

Honestly, rushing shit out was how we got a lot of what everyone hated about FATWS. As a fan of Peggy AND Sam AND Bucky, I'd rather wait a while and get something decent than promptly be handed slop (feel free to look at the last few years of appearances of my favorite characters for some primo examples of slop).

For what it's worth, the best indicator from where I'm standing that Sam is a going concern is that Disney put a live SamCap performer in a California park, despite that incarnation of the character having only one poorly received outing so far. I live close enough to Disneyland that I can set my watch by the fireworks, and I've known a lot of people who worked at the resort, including multiple face performers. The amount of vetting and training and rehearsal involved in debuting one of those--ESPECIALLY a Black character, ESPECIALLY ESPECIALLY a Black Captain America because you KNOW he'll get shit from certain guests--is frankly insane. That's pretty serious money being poured into that character. I haven't seen a walkaround Captain Carter or Bucky Barnes in the parks, but Sam is there. You don't have to trust Disney's good intentions (I certainly don't), but they're generally pretty reliable about doing what they think will turn a profit. Sam is an expensive investment, both in terms of the character's lower historic profile and the additional costs of debuting a Black man as Captain America in Orange fucking County. (For context: Anaheim, the city where Disneyland is located, is locally known as "Klanaheim" because of its history of white supremacist terrorism. This county produced Mendez v. Westminster, one of the school segregation cases that got folded into Brown v. Board. There is a long, vicious history of violent racism in this area, and Disney is aware of it; I've seen resort security "escorting" angry bigots off-property. Disneyland also has a large number of local annual passholders, so it's much less of a tourist park than Disney World is. Local shit matters at Disneyland.)

They still think spending on Sam Wilson, even in Anaheim, will turn them a profit. They're not going to back down from a Sam movie unless Anthony Mackie dies or gets charged with a felony. I can't promise that movie will be good--we all know the risks there--but Disney thinks Sam will make them money, and that alone is promising in my eyes.

I'm very happy that What If season two came out but the "Why is there more Peggy if Sam is Cap" slander is back on Tiktok and it's unbearable.

Peggy is the main focus of What If... Sam is getting a film, Sam will be in multiple films, he is Captain America. Peggy isn't Captain America, she is Captain Carter. Give Peggy an animated show and a five issue comic series, Sam literally has been in comics as C.A. for years and will be billed as a headliner for the next few phases.

Also, tbh, and I really love Hayley Atwell, but I have a feeling she's more available for a tv show than Anthony Mackie. He's a bigger star than she is.

55 notes

·

View notes

Photo

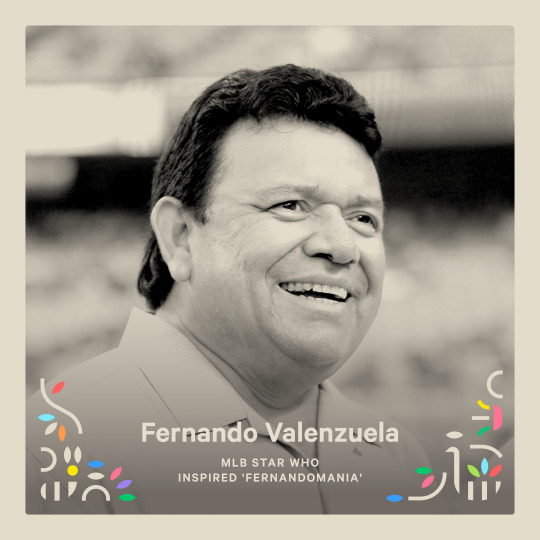

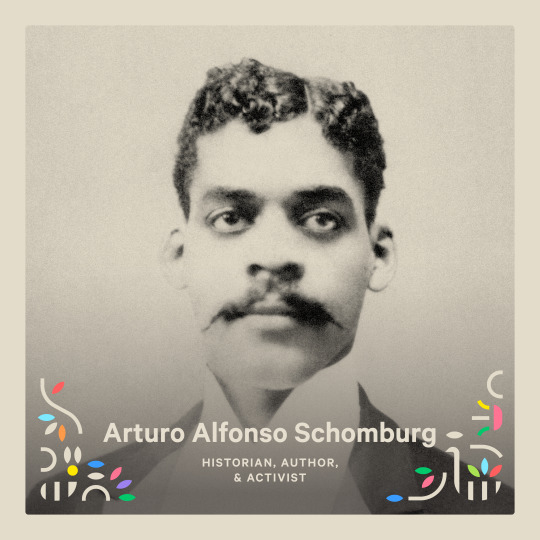

September 15 begins Hispanic Heritage Month — we’re kicking off the month by honoring a number of figures who historically have blazed a trail for the Hispanic American community

Fernando Valenzuela is a former MLB pitcher most famous for his time with the Los Angeles Dodgers from 1980-90. A Mexican immigrant, Valenzuela’s raw talent & colorful personality made him an instant hit with the Dodgers’ significant Latinx fanbase. The ensuing media frenzy became known as ‘Fernandomania’ and represented one of the first times in MLB history that a Hispanic player was a face of baseball. Valenzuela retired in 1997. In 2015, he became a naturalized American citizen.

Sonia Sotomayor is the first Latinx Supreme Court justice in U.S. history, having served since 2009. The daughter of Puerto Rican-born Americans, Sotomayor spent the bulk of her childhood being raised by a single mom in the Bronx, NY. Sotomayor graduated summa cum laude from Princeton in 1976 and earned a law degree from Yale Law School in 1979. Prior to being appointed to the Supreme Court by President Barack Obama, she was a federal judge for 17 years. Her SCOTUS tenure has been characterized by decisions emphasizing criminal justice reform and the civil rights of both defendants and minority communities.

Sylvia Mendez was just 8 years old when she became a civil rights icon. Growing up in 1940s California as the daughter of Mexican & Puerto Rican immigrants, Mendez was a central figure in the landmark 9th Circuit Court of Appeals case Mendez v. Westminster. The decision found that segregating Mexican American students into separate schools in California was unconstitutional and led to the desegregation of all public schools in the state. The arguments used in Mendez v. Westminster later served as a precursor for the 1954 landmark SCOTUS segregation case Brown v. Board of Ed. After childhood, Mendez went on to work as a nurse & a public speaker, and she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2011.

In 2015, Raffi Freedman-Gurspan made history as the first openly transgender person to serve in the White House in U.S. history. A longtime activist & expert on matters pertaining to LGBTQ+ civil rights and gender equality, Freedman-Gurspan was born in Honduras and raised by adoptive parents in Massachusetts. After graduating college in 2009, she pursued activism on the state level in MA for a few years before being hired as a policy adviser at the National Center for Transgender Equality. Her work focused on a number of issues impacting trans Americans, including homelessness, immigration, & incarceration. From there, she served 2 years in the Obama admin, first as an outreach & recruitment director and then as the White House’s LGBT liaison.

Ellen Ochoa is an icon for Latinx women in STEM. An engineer, astronaut, and former director of the Johnson Space Center, Ochoa made history in 1993 when she became the first Hispanic woman to travel to space while aboard the space shuttle Discovery. In her career as an astronaut, Ochoa logged approx 1,000 hours in space across 4 missions. Ochoa, who is a recipient of NASA's Distinguished Service Medal, was inducted into the U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame in 2017.

Arturo Alfonso Schomburg (1874-1938) was an author, historian, activist, and leading intellectual of the Harlem Renaissance. Schomburg was an Afro Latino of Puerto Rican, Black, and German heritage. Over his career, he worked tirelessly to identify, document, and preserve elements of Black history & culture, including art, manuscripts, slave narratives, and other artifacts. The works he amassed are now a collection in the New York Public Library at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem. Schomburg was once quoted as saying, ‘Pride of race is the antidote to prejudice.’

At 88 years young, Rita Moreno remains a treasure of the stage and screen. She is the only Hispanic actor in history to complete the hallowed EGOT, having won an Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony award between 1962 and 1977. Her Oscar win, for the supporting role of Anita in 1961’s ‘West Side Story,�� remains her most iconic part. In recent decades, Moreno is perhaps best known for starring in the Netflix reboot of ‘One Day at a Time.’ In addition to her acting awards, Moreno has also been a Kennedy Center honoree and was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2004.

Sylvia Rivera was an American icon of the early LGBTQ+ liberation movement, with a specific focus on activism for LGBTQ+ people of color and LGBTQ+ people experiencing homelessness. Together with her friend Marsha P. Johnson, Rivera was a fixture in New York City’s radical activist and cultural scene in the 1970s and ‘80s. Rivera & Johnson founded STAR (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries), a local collective that provided housing and aid to young LGBTQ+ New Yorkers at the time. Rivera, who was of Venezuelan & Puerto Rican descent, died in 2002 at the age of 50. In 2005, the corner of Hudson & Christopher streets in NYC’s Greenwich Village was renamed Sylvia Rivera Way.

follow @nowthisnews for daily news videos & more

725 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I was right and everyone else was right in saying that conservatives will use CRT as a buzzword and extend it to mean “literally anything”. The Republican Texas Senate is trying to amend a bill that, if passed, would remove the following from school curriculum.

The history of the Native Americans.

The writings of anyone who isn’t directly a founding father, including their contemporaries, families, and the slaves who were owned by them.

Frederick Douglas’ newspaper, “The North Star”.

The Book of Negroes.

The Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1840.

The Indian Removal Act.

Thomas Jefferson’s “Letter to the Danbury Baptists”.

William Still’s Underground Railroad Records.

Historical documents related to the civic accomplishments of marginalized populations, including documents related to...

The Chicano Movement.

Women’s Suffrage and Equal Rights.

The Civil Rights Movement.

The Snyder Act of 1924.

The American Labor Movement.

The history of white supremacy, including but not limited to the institution of slavery, the eugenics movement, and the Ku Klux Klan, and the ways in which it is morally wrong.

The history and importance of the Civil Rights Movement, including the following documents...

Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail“ and “I Have A Dream” speech.

The United States Supreme Court’s decision in “Brown v. Board of Education”.

The Emancipation Proclamation.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments.

Mendez v. Westminster.

Frederick Douglas’ “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave“.

The life and work of Cesar Chavez.

The life and work of Dolores Huerta.

The history and importance of the women’s suffrage movement, including the following documents...

The Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The 15th, 19th, and 26th Amendments.

Abigail Adam’s letter “Remember the Ladies”.

The works of Susan B. Anthony.

The Declaration of Sentiments.

The life and works of Dr. Hector P. Garcia.

The American GI Forum.

The League of United Latin American Citizens.

Hernandez v. Texas.

Also says that teachers are not compelled to discuss current events, and if they do, they must not give deference to any one perspective. Which sounds benign, until you realize that this means we’re going to have to “both sides” on stuff like “is COVID real” and “did this black man deserve to be executed by the police”.

None of this should be a surprise to anyone. The CRT backlash was always an astroturf and always an excuse to ban any discussion of or even acknowledgement of racism in America. The only surprising element should be in how bold they decided to be about it. Despite adoring the aesthetic of MLK Jr. they secretly hate him, always hated him even when he was alive, but I never would have imagined that they’d actually try to exeunt him from Texas schoolbooks, nor would they bold-facedly try to scrub the Civil Right’s Movement or even the Emancipation Proclamation from the textbooks.

For those who say “oh, they aren’t being banned, they’re just being removed from the curriculum, teachers can still teach them if they want”, I remind you that textbooks are written based off the state curriculum. If MLK isn’t in the Texas curriculum, he isn’t going to be in the Texas textbooks. If you want to argue “why should these need to be taught”, I ask you why they shouldn’t need to be. We all know the saying “those who do not know their history are doomed to repeat it”, so I ask why Texas is trying to make it such that the younger generations won’t be able to know their history specifically concerning the oppression of women and racial minorities, slavery, and the KKK, among other things.

My thing is, conviction and lack of conviction can both be used to intuit where someone’s principles lie. “I think we should teach kids about MLK” is pretty good. “I don’t really care one way or the other about teaching MLK” is pretty bad, because you’re basically saying you’re ambivalent to the Civil Rights movement and just really don’t see what’s so important, man. But I can’t even make the “lack of convictions” argument because there’s a group of people out there whose convictions are apparently “we don’t need people knowing about Civil Rights, or MLK, or women’s rights, or slavery, or” YOU GET IT, RIGHT? This bill doesn’t explicitly say “fuck women, fuck brown people, fuck civil rights, and fuck you”, but I’ve outlined the effects above. None of these will be in the textbooks, and it’s much more likely that they won’t be taught, or taught as extensively as everything else is taught. It would basically eradicate civil rights education, or at least cripplingly kneecap it, which I don’t even think I need to elaborate on why that’s bad. To deny that this would harm civil rights education and to argue “this is harmless, not racist, and morally neutral” is essentially “he brings up racial IQ and crime statistics a lot and he keeps mentioning ‘cultural insurgents’ a lot and he’s constantly going on about ‘reclaiming the fatherland’ but he doesn’t have an armband on so how can we really know he’s a nazi” meme being applied to STATE LEGISLATION CONCERNING SCHOOL EDUCATION.

#oh no renardie is posting#this is what erasing history actually looks like by the way#not removing confederate statues#long post#infoxicated

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

April 14, 1947: Mendez v. Westminster Court Ruling

When Gonzalo and Felicitas Mendez, two California farmers, sent their children to a local school, their children were told that they would have to go to a separate facility reserved for Mexican American students. The Mendez family recruited similarly aggrieved parents from local school districts for a federal court case challenging school segregation.

Unlike the later Brown case, the families did not claim racial discrimination, as Mexicans were considered legally white (based on the preceding Roberto Alvarez v. the Board of Trustees of the Lemon Grove School District above), but rather discrimination based on ancestry and supposed “language deficiency” that denied their children their Fourteenth Amendment rights to equal protection under the law.

On March 18, 1946, Judge Paul McCormick ruled in favor of the plaintiffs on the basis that the social, psychological, and pedagogical costs of segregated education were damaging to Mexican American students. The school districts appealed, claiming that the federal courts did not have jurisdiction over education, but the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ultimately upheld McCormick’s decision on April 14, 1947, ruling that the schools’ actions violated California law. [Zinn]

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

http://latinousa.org/2017/03/17/no-mexicans-allowed-school-segregation-southwest/

315 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Title: Separate is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez and Her Family’s Fight for Desegregation

Author: Duncan Tonatiuh

Illustrator: Duncan Tonatiuh

Published: May 6th, 2014 by Harry N. Abrams

Genre & Format: Nonfiction, Picture Book, Early Reader

Key Themes: Activism, Bilingual, Bullying, Civil Rights, Education, Family, History, Latinx Stories, Multicultural, People & Places, Racism, School, Social Issues

Reading Level: First Grade, Second Grade, Third Grade, Fourth Grade

Language: English, Spanish

ISBN: 9781419710544

Content Warnings:

Bullying

Racism

Publisher’s Synopsis:

“Seven years before Brown v. Board of Education, the Mendez family fought to end segregation in California schools. Discover their incredible story in this picture book from award-winning creator Duncan Tonatiuh.

A Pura Belpré Illustrator Honor Book and Robert F. Sibert Honor Book!

When her family moved to the town of Westminster, California, young Sylvia Mendez was excited about enrolling in her neighborhood school. But she and her brothers were turned away and told they had to attend the Mexican school instead. Sylvia could not understand why—she was an American citizen who spoke perfect English. Why were the children of Mexican families forced to attend a separate school? Unable to get a satisfactory answer from the school board, the Mendez family decided to take matters into its own hands and organize a lawsuit.

In the end, the Mendez family’s efforts helped bring an end to segregated schooling in California in 1947, seven years before the landmark Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education ended segregation in schools across America.

Using his signature illustration style and incorporating his interviews with Sylvia Mendez, as well as information from court files and news accounts, award-winning author and illustrator Duncan Tonatiuh tells the inspiring story of the Mendez family’s fight for justice and equality.”

Review: Latinx’s in Kid Lit

“Kudos to Duncan Tonatiuh for shining a bright spotlight on a consequential, but often overlooked chapter of American civil rights, and bringing this true story of Latinos fighting for racial justice to young readers. The book features Tonatiuh’s trademark, award-winning illustration and his retelling of the facts.

[...]

“Tonatiuh’s account highlights the exemplary character of Mr. and Mrs. Mendez. Every movement for justice has its heroes and pioneers, and the Mendez family richly deserves that level of recognition. Taking up the fight involved considerable personal risk. They used their life savings to kickstart the legal fund. Eventually, they received wider support. Leading the charge took Mr. Mendez away from the farm for long stretches, leaving Mrs. Mendez to perform farming tasks that her husband normally would have handled. As the story shows, many Mexican families in the community declined to join the lawsuit, for fear of economic retribution. “No queremos problemas,” they said.

“The California campaign for educational equality, spearheaded by the Mendez case, ultimately led to the 1954 ruling on Brown v. Board of Education. The victory illuminated by Separate is Never Equal belongs in a clear line of prominent milestones of American civil rights. How fortunate that someone with Tonatiuh’s skill has brought it out of the shadows.”

Additional Resources:

Purchase

Video Read-Along

Educator’s Guide

#seperate is never equal#sylvia mendez#duncan tonatiuh#2014#nonfiction#picture book#activism#bilingual#bullying#civil rights#family#latinx stories#multicultural#racism#school#education#social issues#cw:bullying#cw:racism#grade 1#grade 2#grade 3#grade 4

1 note

·

View note

Text

Mendez V. Westminster

By Vanessa Gutierrez, George Mason University Class of 2023

April 7, 2021

The Brown v. Board of Education came to the conclusion that separate but equal educational facilities for racial minorities is inherently unequal, violating the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.[1] Under these circumstances, all students of different races should be able to go to public schools without the need of segregation.

In 1947, Gonzalo and Felicitas Mendez tried to enroll their children Silvia, Gonzalo Jr., and Jerome in the local school, they were told that the school was for "whites only", "no Mexicans allowed".[2] Like the Silvia, Gonzalo Jr., and Jerome, many Hispanic and Latinx students across the nation had to attend “Mexican” schools.

The school board argued that Mexicans were inferior to whites and couldn't speak English.[3]

In February 1946, Judge Paul J. McCormick ruled in favor of the Mendez family arguing that segregation was unconstitutional, creating inequality where there was none. Separate is not equal.[4]

This case was later used in the Brown v. Board of Education to argue that separate but equal violated the 14th Amendment. The Mendez v. Westminster undoubtable created a legacy that fought for the desegregation which applied to more than one marginalized group of students with a different race and background.

The United States has a history of racial discrimination and with cases such as Mendez v. Westminster and Brown v. Board of Education, these cases were the first step taken to establish a more just society within the education system.

The Mendez v. Westminster has not been talked about much and it is a very significant case that has had an impact on the lives of many Hispanic and Latinx students across the United States and later with the Brown v. Board of Education, African American students.

The highlight of this case was that Silvia, Gonzalo Jr., and Jerome’s parents, Gonzalo and Felicitas Mendez took their case to court to fight and seek justice to allow not just their children go to school without being denied and turned away by the color of their skin which enabled the nation to do the same, which is to desegregate schools.

Now, in 2021, the fight for DACA and Dreamers have been to provide aid and more opportunities to not be affected by their immigration status. In most cases, what stops these students from being successful is not being able to afford college because of their status. The case of Mendez v. Westminster influenced a new perspective that led to a new challenge.

The case of Mendez v. Westminster also gives hope to many Hispanic and Latinx students who find comfort in knowing that they can use a case such as this one to continue to use resources and communicate with elected officials to push bills to help one have a better chance to be successful in the United States.

______________________________________________________________

[1] "Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1)." Oyez, www.oyez.org/cases/1940-1955/347us483. Accessed 21 Mar. 2021.

[2] Delgado, O. “9-Year-Old Sylvia Mendez Fought ‘No Mexicans Allowed’ - And Won.” LatinLife, www.wearelatinlive.com/article/13656/9-year-old-sylvia-mendez-fought-no-mexicans-allowed-and-won.

[3] Delgado, O.

[4] Delgado, O.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sylvia Mendez

Sylvia Mendez was born in 1936 in Santa Ana, California. When Mendez was a child, she was denied enrollment at an all-white school, and attended a segregated school for Mexican students. Her family successfully challenged this in the landmark case Mendez et. al v Westminster School District of Orange County, a decision that laid the groundwork for the integration of schools in California, and helped pave the way for the landmark Brown v Board ruling. Mendez went on become a pediatric nurse, but after retirement, devoted herself to civil rights education, traveling the country to discuss the importance of the Mendez case. In 2011, she received the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Felicitas Gómez Martínez de Mendez (February 5, 1916 – April 12, 1998) was a Puerto Rican activist in the American civil rights movement. In 1946, Mendez and her husband Gonzalo led an educational civil rights battle that changed California and set an important legal precedent for ending de jure segregation in the United States. Their landmark desegregation case, known as Mendez v. Westminster, paved the way for meaningful integration and public school reform.

1 note

·

View note