#matania

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Man by Fortunio Matania

“Barcley Owens notes that in All the Pretty Horses, after humans have turned their backs on him, "John Grady will return to his love of horses, as they prove more reliable and less complicated than other dreams. His love for horses marks him as a traditional cowboy hero, in love with the cowboy's wandering, rustic life ... [and] horses represent his hope for a meaningful life ... the life of his grandfather who pioneered Comanche country" (72-3). Owens' overly romantic assessment of Cole's romantic notions is partially correct, for in scene after scene, Cole is left disappointed by human beings, but horses, most often in travel, and in work and in battle, support him. Additionally, from the onset of the text, McCarthy secures Cole to the Comanche Indian past, and thus, posits the horse in the slot of warrior, for the Comanche were history's greatest warrior horsemen, and their horses, too, were warriors. Further, the text is a lament on the passing of the horse's status as warrior, for as the Comanche have been annihilated and relocated by the late nineteenth century, by the mid-twentieth century, the horse-riding cowboy is exceedingly rare, even in Texas. Cole is a man out of time, and his romantic idealism promotes the past and his love of horses over men. As such, McCarthy frames the text with scenes that evoke the Indian past and present, scenes that include Cole and his warrior equine, Redbo.

In the first scene that invokes the Comanche past and calls to the reader's attention the role of the horse as warrior, Cole and Redbo ride the soon-to-be-sold Grady ranch, and Cole seeks out an old Comanche travel route:

At the hour he'd always choose when the shadows were long and the ancient road was shaped before him in the rose and canted light like a dream of the past where the painted ponies and the riders of that lost nation came down out of the north with their faces chalked and their long hair plaited and each armed for war which was their life and the women and children and women with children at their breasts all of them pledged in blood and redeemable in blood only. When the wind was in the north you could hear them, the horses and the breath of the horses and the horses' hooves that were shod in rawhide and the rattle of lances and the constant drag of the travois poles in the sand like the passing of some enormous serpent and the young boys naked on wild horses jaunty as circus riders and hazing wild horses before them and the dogs trotting with their tongues aloll and footslaves following half naked and sorely burdened and above all the low chant of their traveling song which the riders sang as they rode, nation and ghost of nation passing in a soft chorale across that mineral waste to darkness bearing lost to all history and all remembrance like a grail the sum of their secular and transitory and violent lives [5].

This dreamy two-sentence passage serves a number of rhetorical purposes. First, the passage is a lament on an ancient nation of people whe way of life is now extinct, the Comanche. For as the Anglo settled Texas and land was parceled off, the Comanche were overwhelmed by the sheer numbers of settlers and the U. S. Cavalry and were unable to stop tl onslaught of civilization upon their ancient lands. Analogously, in autumn of 1949, the cowboy way of life is also becoming extinct. With reference to Cole, as his mother is going to sell the Grady homestead his specific cowboy life is coming to a close. Notice as well, the Comanche are riding south, and as Cole is conjoined in this passage with the Indians and the Indian past, their ghostly visitation is an invitation and a foreshadowing of Cole's imminent journey south into Mexico—to Cole, unchartered, uncivilized warrior territory. Of course, the Comanche men are armed and ready for war, "which was their life." For these people are a warrior race, and all debts are redeemable "in blood only." Moreover, even the women and breast-suckling infants are "pledged in blood." As such, one can safely assume the whole of the Comanche nation exists in a unified and constant state of war, and from birth, the Comanche children are trained and taught the manners of battle and the skills of war. The presence of footslaves indicates the Comanche determinism to conquer and kill or capture all whom they encounter. And of course, as members of the Comanche nation, the horses of the warriors are themselves warriors.

M. Oldfield Howey indicates that in times prior to the onslaught of the Anglo, when horses were plenty, "the Comanches, in Texas [would] kill and bury the horses of their dead comrades, so that the dead may ride them to the Happy Hunting-grounds ... [and] the manes and tails of the horses of the tribe are cut off as a testimony of grief" (201). This death ritual indicates that a warrior and a warrior horse should be together in death as well as in life, and the McCarthy passage also shows a particular warrior kinship between horse and man, for the warriors are chalked and painted for war, as are the ponies. This duality of war decoration unites the warrior human with the warrior equine, and the bond is one that will exist in the afterlife. A Comanche warrior and his warrior pony will live and wage war, in life and in death, and the Indian warrior is spiritually shackled to his warrior horse. Clearly, McCarthy is arguing the horse as a warrior animal, a warrior whose time is passing and soon to be past. And clearly, McCarthy is hitching Cole and Redbo to the Comanche and his warrior pony; as Cole's father states, "We're like the Comanches was two hundred years ago. We don't know what's goin to show up here come daylight" (25-6). That is, the times are changing, and we are unable to stop the onslaught of change, just as the Comanche were unable to stop the onslaught of Anglo driven change. Conjoining Cole and Redbo to the Comanche past, and their extinct way of life, is an attempt to show that the warrior equine—whose role now is cattle horse in Texas—will soon be absolutely extinct in the United States, regardless of the animal's deterministic abilities. But before extinction, the warrior horse and his rider travel to old Mexico, where a warrior equine is a handy partner in a cowboy's survival. As such, Redbo proves himself a warrior under fire, and further, one of McCarthy's characters specifically articulates the horse's position as warrior animal.

One of the defining characteristics of a warrior is that a captured warrior is worth the life risk of rescuing, and on more than one occasion in the text, a captured horse, or horses, are rescued—or re-stolen—by Cole and his compatriots Lacey Rawlins and Jimmy Blevins. In the first example, Blevins loses his fine bay horse in a lightning storm, and Cole, Rawlins and Blevins, at much risk, rescue the captured warrior, who is being held in the Mexican pueblo of Encantada. Prior to the rescue, Redbo anticipates the battle, "John Grady leaned forward and spoke to the horse and put his hand on the horse's shoulder. The horse had begun to step nervously and it was not a nervous horse" (82). The horse, as a warrior and no longer a cow horse, can sense that battle is about to be waged, and he is right, for Blevins re-steals his horse, and the three boy warriors and their three warrior horses must make a hasty retreat from the town:

Rawlins pulled his horse around and the horse stamped and trotted and he whacked it across the rump with the barrel of the gun ... and Blevins in his underwear atop the big bay horse... exploded into the road ... and there were three pistol shots from somewhere in the dark ... [and] before they reached the turn at the top of the hill there were three more shots from the road behind them (83).

The horses three have passed their first trial by fire, but the boys are the ones who will eventually pay for this battle—Blevins with his life and Rawlins and Cole with their blood and innocence. But at this point in the text, all three warrior horses are united in their first successful battle and their courage under fire, and the author has shown that in Mexico, the horse remains a warrior.” - Wallis R. Sanborn III, ‘Animals in the Fiction of Cormac McCarthy’ (2006) [p. 123 - 126]

#mccarthy#cormac mccarthy#animals#horses#matania#fortunino matania#all the pretty horses#border trilogy

1 note

·

View note

Text

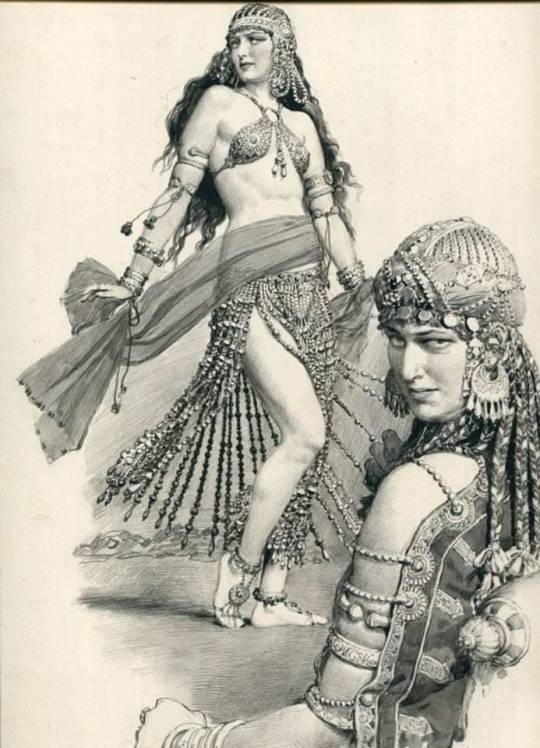

'Paulina in the Temple of Isis' by Fortunino Matania, c. 1939

552 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pegasus, the Winged Horse by Fortunino Matania

#pegasus#art#fortunino matania#mythical creatures#greek mythology#winged horse#wings#horse#horses#mythology#ancient greece#ancient greek#classical antiquity#europe#european#bellerophon#perseus#mythological#religion

259 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the Hareem by Fortunino Matania (1881-1963)

265 notes

·

View notes

Text

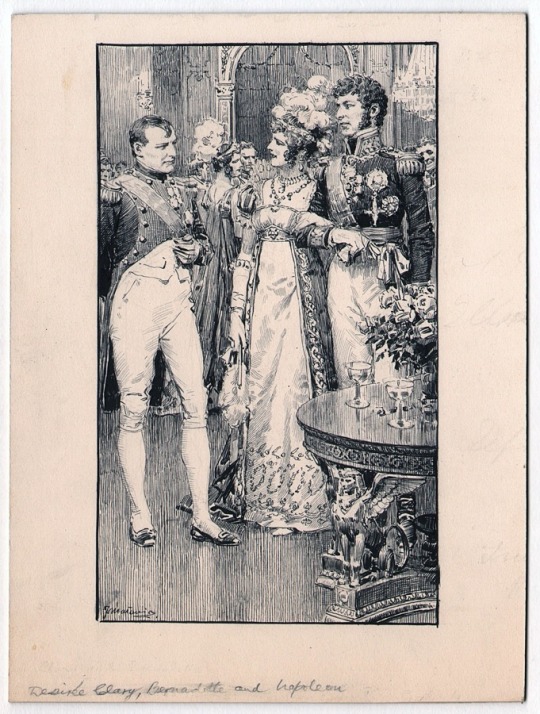

More of Fortunino Matania’s illustrations of Napoleon. He draws him so well! 😚💗

The Princess Caraboo story is so hilariously ridiculous though. So she is an English lady (Mary Willcocks) who pretended to be a princess from some unknown island and she managed to fool everyone in Gloucestershire. When she finally got exposed, she was sent to Philadelphia. Along the journey, the ship was caught in a storm near St. Helena and Princess Caraboo apparently got on a boat and rowed ashore by herself. This somehow impressed Napoleon so much that he wanted to marry her 😭 Of course, this story is probably bollocks but it’s fun to think about!

Pics in order:

Princess Caraboo and Napoleon

Napoleon and Josephine

Napoleon With His Officers in an Encampment

Bernadotte and Napoleon

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

Goodbye, Old Man. A British soldier bids farewell to his dying horse on the road to a battery position in Southern Flanders. Painting by Fortunino Matania. It was commissioned by The Blue Cross Fund in 1916 to raise money to help relieve the suffering of horses and I've read the original painting is in the Blue Cross Victoria Animal Hospital.

I've seen another version of this. it has the soldier's head tilted the other way, holding the left side of his face against his companion's head. Possible Matania did two paintings of it. Either way it's a very poignant piece of work.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

"With the field guns on the Western Front". A visit to a British battery - published in 1916 for Tatler and Sphere. Chevalier Fortunino Matania (16 April 1881 – 8 February 1963) was an Italian artist noted for his realistic portrayal of World War I trench warfare.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fortunino Matania

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

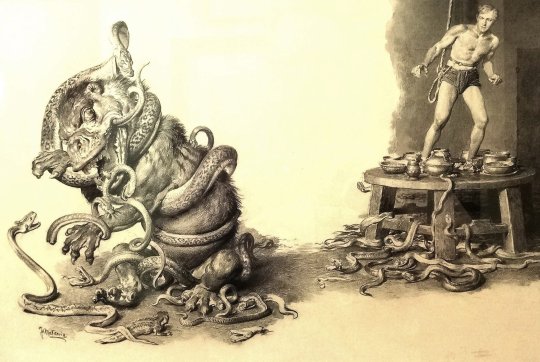

Presently the tharban ceased its offensive and began to back away. I watched the weaving, undulating head of the great snake following every move of its antagonist. The lesser snakes swarmed over the body of the tharban; it seemed not to notice them. Then, suddenly, it wheeled and sprang for the entrance to the corridor that led to its lair. This, evidently, was the very thing for which the snake had been waiting. It lay half coiled where it had been fighting; and now like a giant spring suddenly released it shot through the air; and, so quickly that I could scarcely perceive the action, it wrapped a dozen coils about the body of the tharban, raised its gaping jaws above the back of the beast's neck, and struck!

Art for Edgar Rice Burroughs' Lost on Venus by Fortunino Matania.

This particular segment, the Room of the Seven Doors, is one of those amazingly over-the-top pulpy Situations.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fortunino Matania (1881-1963)

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Viking Duel by Fortunino Matania

#fortunino matania#art#duel#single combat#duelling#combat#vikings#viking#europe#european#history#germanic

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

Totteridge Gallery

An illustration for The London Magazine, published in January 1928, which accompanied a story written by Frederick Britten Austin.

Thanks to @largecucumber for including this in a post and knowing the name of the artist!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Goddess Who Saved a City by Fortunino Matania (1933)

205 notes

·

View notes