#marie de coucy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

ROYALTY MEME | Granddaughters of Edward III & Philippa of Hainault (part one)

through their children: Lionel of Antwerp, John of Gaunt, and Isabella of England

#historyedit#historicwomendaily#philippa plantagenet#philippa of lancaster#elizabeth of lancaster#marie de coucy#philippa de coucy#edward iii#philippa of hainault#history#women in history#weloveperioddrama#cortegiania#userperioddrama#perioddramaedit#userbennet#perioddramasource#onlyperioddramas#*royalty meme#my edit

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mother and daughter

Mothers and daughters, too, could have fundamentally different life courses despite nominal similarities. Helvide of Dampierre (ca. 1172-ca. 1225) and her daughter Marie of Montmirail (ca. 1205-72) , for example, both were third daughters who were married in their mid-teens to distinguished castle lords (Montmirail, Coucy) . Both had lengthy marriages (twenty-five and twenty-three years), several children (six and five), and were widowed at about thirty-seven. But their marriages were quite different. Helvide, who was no more than five or six years younger than her husband Jean of Montmirail, shared his lordship during marriage (1185-1210), jointly sealing letters with him for a decade before he abandoned her for the cloister. She continued to exercise lordship over his lands, over her own dowry, and over her dower lands until their eldest surviving son succeeded. Her second career as lordly widow was simply an extension of her first career as lordly wife. As her children came of age, she gave up the various Montmirail properties and withdrew to her dower castle at Montmirail, which she held for more than a decade (1212-ca.1225), exercising lordship just as she had shared it with Jean I during their marriage. In fact, Helvide had exercised lordship during her entire adult life. Her daughter Marie, by contrast, did not. As the third wife of the considerably older Enguerran III of Coucy, she did not share lordship with him during their twenty-three-year marriage (1219-42), nor did she assume the lordship of his lands after his death, since her two sons inherited immediately. Marie's thirty-year widowhood (1242-72), twice as long as her mother's, would have proved entirely uneventful had she not outlived all five of her siblings, none of whom left heirs. As it turned out Marie, at fifty-eight, became sole heiress of the entire collection of her parents' castle lordships and titles. Whereas her mother Helvide had overseen the division of the Montmirail properties among her children, Marie, the youngest of six children, purely by chance reconstituted her father's entire collection of properties. There was one further difference. Helvide, having been much aggrieved by Jean I's taking the religious habit and leaving her with underaged children, chose to be buried at Vaucelles in Picardy. Marie, who had a strong tie to her father, commissioned a great tomb for him and obtained permission from the monks of Longpont to be buried next to him; the tomb was inscribed: "daughter of a most worthy knight and most devoted monk Jean, former lord of Montmirail, and mother of Enguerran [IV] of Coucy."

Theodore Evergates- The Aristocracy in the County of Champagne - 1100-1300

#xii#xiii#theodore evergates#the aristocracy in the county of champagne: 1100-1300#helvide de dampierre#marie de montmirail#enguerrand iii de coucy#enguerrand iv de coucy#jean i de montmirail#history of champagne

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

On July 6th 1249 King Alexander II died on the island of Kerrera.

The kings of Scots of the old Celtic line were plagued in the thirteenth century by a persistent inability to breed male heirs. William the Lion, whose reign lasted fifty years till his death in 1214, was well into his middle fifties when his son and heir, the future Alexander II, at last arrived. Alexander was sixteen when he took his place on the hallowed coronation stone at Scone.

Alexander was at once threatened by his relatives, the MacWilliams, descended from King Duncan II, who had been murdered in 1094. They believed they had a better right to the throne than the incumbents, had already made attempts to attain it, and had no shortage of male heirs. Now, in 1215, Donald Bane, a great-grandson of King Duncan, rose in the north, but he and his supporters were quelled by a powerful Celtic lord, Farquhar MacTaggart, who sent Alexander the severed heads of the rebels as a present. Alexander was less Norman-oriented and more Celtic in his sympathies than his father and this support from a Celtic lord was significant.

It was a brutal age and in the 1220s Alexander would have the hands and feet of eighty men of Caithness cut off to punish them for roasting their bishop alive, while another challenge from the MacWilliams in 1230 would end with the brains of the challenger’s baby daughter being beaten out against the market cross in Forfar.

Alexander meanwhile had no baby of his own. He had married Joan, the eldest sister of Henry III of England, but the years went by and there were no children. The nearest male heir was Alexander’s cousin, John, Earl of Huntingdon, but he died in 1237, childless. The English kings had already laid claim to being Scotland’s suzerains and the situation was so threatening that, apparently, it was decided that if Alexander died without a son, his successor would be Robert Bruce, lord of Annandale, as the nearest male in line. Or so the Bruces were to claim.

When Queen Joan died in 1238 on a visit to England, Alexander took the opportunity to marry again. He chose a French lord’s daughter, Marie de Coucy, and in 1241, to what must have been the huge relief of them both, she presented him with an heir, the future Alexander III, who was to be their one and only child. The king, who had extended his effective sway to both Galloway and Argyll, with assistance from Farquhar MacTaggart, now set out to buy the Western Isles from their ruler, Haakon IV of Norway. The offer was not accepted and in 1249 Alexander gathered an invasion fleet. He had got as far as the island of Kerrera, across the water from Oban, when he fell sick of a fever and died.

The heir, Alexander III, was a boy of seven, and was ten when he was married to Henry III’s eleven- year-old daughter, Margaret. He grew up to be one of the best kings of his line, but all his children died in his own lifetime and when he himself was killed in a riding accident in 1286 his successor was his baby granddaughter, known as the Maid of Norway. She died only four years later and the way was wide open for the ruthless Edward I of England to intervene, claiming to be Scotland’s overlord, and to sort out the succession. The intervention was unsuccessful in the end, but it led to centuries of intermittent war, and Scots in later times looked back to the reigns of Alexander II and Alexander III as a golden age.

Alexander II has the honour of being the only Scottish king to take his invasion force all the way to the south coast of England.

Whilst still a teenager, Alexander backed a rebellion of northern English barons against the King of England, John I. Hoping to secure the territories of Northumberland, Alexander and his army invaded England. They reached the port of Dover where, while waiting to join a French invasion force, the invasion failed. The death of John I saw the English barons change their allegiances. Alexander left empty-handed.

The third pic is Gylen Castle on Kerrera.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ages of English Princesses at First Marriage

I have only included women whose birth dates and dates of marriage are known within at least 1-2 years, therefore, this is not a comprehensive list. The average age at first marriage among these women was 16.

This list is composed of princesses of England when it was a sovereign state, prior to the Acts of Union in 1707.

Eadgyth (Edith) of England, daughter of Edward the Elder: age 20 when she married Otto the Great, Holy Roman Emperor in 930 CE

Godgifu (Goda) of England, daughter of Æthelred the Unready: age 20 when she married Drogo of Mantes in 1024 CE

Empress Matilda, daughter of Henry I: age 12 when she married Henry, Holy Roman Emperor, in 1114 CE

Marie I, Countess of Boulogne, daughter of Stephen of Blois: age 24 when she was abducted from her abbey by Matthew of Alsace and forced to marry him, in 1136 CE

Matilda of England, daughter of Henry II: age 12 when she married Henry the Lion in 1168 CE

Eleanor of England, daughter of Henry II: age 9 when she married Alfonso VIII of Castile in 1170 CE

Joan of England, daughter of Henry II: age 12 when she married William II of Sicily in 1177 CE

Joan of England, daughter of John Lackland: age 11 when she married Alexander II of Scotland in 1221 CE

Isabella of England, daughter of John Lackland: age 21 when she married Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, in 1235 CE

Eleanor of England, daughter of John Lackland: age 9 when she married William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke in 1224 CE

Margaret of England, daughter of Henry III: age 11 when she married Alexander III of Scotland in 1251 CE

Beatrice of England, daughter of Henry III: age 17 when she married John II, Duke of Brittany in 1260 CE

Eleanor of England, daughter of Edward I: age 24 when she married Henry III, Count of Bar in 1293 CE

Joan of Acre, daughter of Edward I: age 18 when she married Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester in 1290 CE

Margaret of England, daughter of Edward I: age 15 when she married John II, Duke of Brabant in 1290 CE

Elizabeth of Rhuddlan, daughter of Edward I: age 15 when she married John I, Count of Holland in 1297 CE

Eleanor of Woodstock, daughter of Edward II: age 14 when she married Reginald II, Duke of Guelders in 1332 CE

Joan of the Tower, daughter of Edward II: age 7 when she married David II of Scotland in 1328 CE

Isabella of England, daughter of Edward III: age 33 when she married Enguerrand VII, Lord of Coucy in 1365 CE

Mary of Waltham, daughter of Edward III: age 16 when she married John IV, Duke of Brittany in 1361 CE

Margaret of Windsor, daughter of Edward III: age 13 when she married John Hastings, Earl of Pembroke in 1361 CE

Blanche of England, daughter of Henry IV: age 10 when she married Louis III, Elector Palatine in 1402 CE

Philippa of England, daughter of Henry IV: age 12 when she married Eric of Pomerania in 1406 CE

Elizabeth of York, daughter of Edward IV: age 20 when she married Henry VII in 1486 CE

Cecily of York, daughter of Edward IV: age 16 when she married Ralph Scrope in 1485 CE

Anne of York, daughter of Edward IV: age 19 when she married Thomas Howard in 1494 CE

Catherine of York, daughter of Edward IV: age 16 when she married William Courtenay, Earl of Devon in 1495 CE

Margaret Tudor, daughter of Henry VII: age 14 when she married James IV of Scotland in 1503 CE

Mary Tudor, daughter of Henry VII: age 18 when she married Louis XII of France in 1514 CE

Mary I, daughter of Henry VIII: age 38 when she married Philip II of Spain in 1554 CE

Elizabeth Stuart, daughter of James VI & I: age 17 when she married Frederick V, Elector Palatine in 1613 CE

Mary Stuart, daughter of Charles I: age 10 when she married William II, Prince of Orange in 1641 CE

Henrietta Stuart, daughter of Charles I: age 17 when she married Philippe II, Duke of Orleans in 1661 CE

Mary II of England, daughter of James II: age 15 when she married William III of Orange in 1677 CE

Anne, Queen of Great Britain, daughter of James II: age 18 when she married George of Denmark in 1683 CE

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anne of Austria (1601-1666) and her two children, the future Louis XIV, and Philippe, Cardinal Mazarin: Former Chief minister of France & François de Bourbon-Vendôme, son of César de Bourbon-Vendôme and Françoise de Lorraine, is a grandson of Henri IV. He is the first cousin of King Louis XIV. He remains single and dies without issue.

Louis XIV

King of France

Louis XIV, also known as Louis the Great or the Sun King, was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the longest of any sovereign.

Born: September 5, 1638, Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye

Died: September 1, 1715, Palace of Versailles, Versailles

Spouse: Françoise d'Aubigné, Marquise de Maintenon (m. 1683–1715), Maria Theresa of Spain (m. 1660–1683)

Children: Louis, Grand Dauphin, Louis Auguste, Duke of Maine, MORE

Grandchildren: Philip V of Spain, Louis, Duke of Burgundy, MORE

Parents: Louis XIII, Anne of Austria

Nicknames: Louis the Great, Sun King

Anne of Austria

Queen of Navarre

Anne of Austria was an infanta of Spain who became Queen of France as the wife of King Louis XIII from their marriage in 1615 until Louis XIII died in 1643. She was also Queen of Navarre until that kingdom was annexed into the French crown in 1620.

Born: September 22, 1601, Valladolid, Spain

Died: January 20, 1666, Val-de-Grâce Hospital, Paris

Grandchildren: Louis, Grand Dauphin, MORE

Children: Louis XIV, Philippe I, Duke of Orléans

Spouse: Louis XIII (m. 1615–1643)

Siblings: Philip IV of Spain, Maria Anna of Spain

Parents: Philip III of Spain, Margaret of Austria, Queen of Spain

Philippe I, Duke of Orléans

Brother of Louis XIV.

Monsieur Philippe I, Duke of Orléans, was the younger son of King Louis XIII of France and his wife, Anne of Austria. His elder brother was the "Sun King", Louis XIV. Styled Duke of Anjou from birth, Philippe became Duke of Orléans upon the death of his uncle Gaston in 1660.

Born: September 21, 1640, Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye

Died: June 9, 1701, Parc St cloud, Saint-Cloud

Children: Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, Marie Louise d'Orléans, MORE

Great grandchildren: Louis XV, Marie Antoinette, MORE

Spouse: Elizabeth Charlotte, Madame Palatine (m. 1671–1701), Henrietta of England (m. 1661)

Siblings: Louis XIV

Grandchildren: Marie Adélaïde of Savoy, Louis, Duke of Orléans, MORE

Cardinal Mazarin

Former Chief minister of France

Jules Cardinal Mazarin, born Giulio Raimondo Mazzarino or Mazarini, was an Italian cardinal, diplomat and politician who served as the chief minister to the Kings of France Louis XIII and Louis XIV from 1642 to his death. In 1654, he acquired the title Duke of Mayenne and in 1659 that of 1st Duke of Rethel and Nevers.

Born: July 14, 1602, Pescina, Italy

Died: March 9, 1661, Vincennes

Nationality: French, Italian

Place of burial: Collège des Quatre-Nations, Paris

Full name: Giulio Raimondo Mazzarino

Siblings: Girolama Mazzarini, Michele Mazzarino

Organization founded: Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture

François de Vendôme, duc de Beaufort

Cousin of King Louis XIV

François de Vendôme, duc de Beaufort was the son of César, Duke of Vendôme, and Françoise de Lorraine. He was a prominent figure in the Fronde, and later went on to fight in the Mediterranean.

Born: January 16, 1616, Coucy Castle, Coucy-le-Château-Auffrique

Died: June 25, 1669, Heraklion, Greece

Great-grandparents: Antoine of Navarre, Jeanne d'Albret, MORE

Grandparents: Henry IV of France, Gabrielle d'Estrées, MORE

Parents: César, Duke of Vendôme, Françoise of Lorraine, Duchess of Vendôme

Uncle: Louis XIII

Louis, Anne, Philippe, Mazarin, Beaufort, and most importantly, Pistache

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

sunday snippet

So it turns out I am writing a sequel to a chance that doth redeem all sorrows (my AU fic where Anne of Bohemia survives the plague). I’d been batting around the idea for a while and @nuingiliath gave me a couple of ideas so I figured, why not? It’s going to be set a few years after the original fic and will have a lot of focus on the Lancasters--the first fic leaves Henry in a really sad place so I’m going to let him remarry. Which is going to freak his older kids out a lot, since they are the only ones who really remember Mary, which is necessary context for the following bit. (Hal is about 11 or 12 here; I haven’t decided exactly when it’s set.)

*

"Since I was ill, I get tired easily," the Queen says, lowering her eyes. "Would it be all right if I took your arm while we walk?"

Hal smiles and offers his arm. He is taller than she is—he'd never noticed that before, although it wasn't true last time he saw her, either; it was before she had become ill.

"Thank you," she says, and smiles back.

The apple trees in the orchard are indeed in bloom, fragrant clouds of pink and white just flecked with green, bees floating lazily by. His mother would have loved it—she loved her gardens as much as Queen Anne does.

"Are you going to tell his Highness what Thomas said?" he says.

"I tell him most things," the Queen replies, "but I do not think I need to tell him that."

"Thank you, your Highness," Hal says. "Thomas is stupid, but I don't want him to get in trouble. At least, not for this."

"I understand," the Queen says. "My own brothers can be very stupid."

"But your brother is the Emperor," Hal says.

"And my other brother is the King of Hungary," the Queen says, "and he would point out that our elder brother is only Emperor-elect. And they can both be very, very stupid. Not all the time, of course, but often enough." She raises a surprisingly mischievous eyebrow at Hal, and he finds himself grinning in response, although he doesn't know how to reply; it doesn't seem quite polite to agree with her, even though she's trying to make him feel better. "But your brother is only a boy, after all," she continues. "And it is not stupid to miss one's mother. Even years later." She pats his arm with her free hand. "I still miss my mother, you know, even as a grown woman. She died not long before your mother did—I had not seen her in ten years even then."

"I'm sorry," Hal says, and means it. Of course everyone knows the basics, that her father was the Emperor and her brother is the Emperor-elect and her other brother is the King of Hungary, but it's never really occurred to him to think of the Queen as someone with a family hundreds of miles away that she'll never see again.

"She is with God now, of course," the Queen says, "as your mother is, and we will both see them again one day, yes?"

"Of course," Hal says. He feels as though he should make the sign of the cross, but the Queen is still holding his right arm and it doesn't feel right to pull it away. God will understand, he hopes. "You knew my mother, right?"

Queen Anne nods. "Not as well as I would have liked," she says, "but I always considered her my friend, even when our husbands were at odds—and they were always at odds." She gives Hal that look again, the one which makes him think there's something she doesn't want to tell him about. "I think she was much happier up north, with you and your brothers and sister, then she was at court. You made her so happy, Harry—whenever I saw her with one of you, I nearly wept for it." She breaks off then, looking a little like she wants to weep now. Hal wonders if it's because she has no children herself. "She loved you so much," she says.

Hal swallows hard, and nods. "I know," he says, watching his feet. He wants to go home, except not really. He wants to go home five years ago.

#sunday snippet#i'm gonna hook henry up with philippa de coucy#they can bond over their mutual hatred of philippa's ex-husband#also thomas has just kinda lashed out at anne#because she had the freaking black death and survived#mary was having a baby which is a perfectly normal thing and she died#fic#the plague survival au

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Black Prince had received the best education available. He was taught by the scholar and astrologer Dr Walter Burghley, and was expected to excel as the future King of England. This served him well for he gleaned a sense of his own majesty from an early age: at seven he was even accoutred with his own suit of armour. Whilst his parents were in Flanders, the year before John of Gaunt's birth, the Prince opened Parliament on behalf of the King.'

Before he was ten, the Prince led an elite entourage, greeting the envoys of the Pope at the gates of the City of London (in the fourteenth century London was still encased inside a large defensive wall, with around seven gates that allowed access from north to south of the City).

Aged ten, the Prince represented his father as the head of state, and even served as head of the realm whilst Edward Ill was in Antwerp around the time of John of Gaunts birth. Thrust onto centre stage, the Black Prince's ability to work the crowd came from ample experience at a young age in the public eye. Alongside his glittering public image, the Black Prince managed extensive land and property in Cheshire and Cornwall, overseeing local administration, and cultivating loyalty from his tenants.

When John of Gaunt lived with his brother he was expected to learn the skills required for leadership military and domestic. This period of fraternal bonding forged an enduring closeness between the two boys, despite the ten-year age difference between them.

The military victories of Prince Edward were legendary. He went on to be the hero of Poitiers, and his reputation was that of a chivalrous prince, albeit an arrogant one. During the Battle of Poitiers, the Black Prince captured the French King, John II. That night, he served his royal captive on bended knee as a page.

Isabella Plantagenet, born two years after the Black Prince and named after the dowager Queen, was equally as indulged by Edward Ill as her older brother. She ran up vast debts due to her extravagant lifestyle. (…) She eventually fell in love with, and married, one of the King’s hostages from Poitiers, Enguerrand de Coucy, a French aristocrat. During the war, Councy (…) refused to fight for either England or France.

Princess Joan was five years older than John of Gaunt, followed by William of Hatfield who died in infancy, and was subsequently buried in York. His death was followed by the birth of another prince, Lionel, who would grow to be the giant of the Plantagenet family, an improbable seven feet tall according to chronicler John Hardyng. After John, came four younger surviving siblings: Edmund, Mary, Margaret and Thomas, filling the royal nursery.

Aged fourteen, Edward's ‘dearest daughter' Joan left England to marry Pedro of Castile, cementing an Anglo-Castilian alliance crucial to Edward's military agenda. As her ship drew into the harbour at Bordeaux, her retinue were unaware of the horror they were about to face: the relentless and devastating Black Death now spreading quickly throughout Europe. The royal party fled to Loremo, a small village in ordeaux, but the Princess could not outrun the disease. Joan died unwed on I July 1348, with no family around her. His sister's death had a lasting impact on John of Gaunt; in 1389 he endowed an obit - an intimate religious service - for her at the Cathedral of St André at Bordeaux, where she was buried.”

Carr, Helen. The Red Prince.

#plantagenet dynasty#plantagenets#house of plantagenet#edward iii#plantagenet#John of Gaunt#Edward the black prince#Isabella Plantagenet#Mary Plantagenet#Joan Plantagenet#Margaret plantagenet#Thomas of Gloucester#Thomas of Woodstock#Lionel of Clarence#Lionel of Antwerp#Lionel Plantagenet#John#John Plantagenet#Philippa of Hainault

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The ladies-only banquet was one of many events organized in the days that immediately followed the ceremony held on June, 5th 1313, where the three sons of the King of France Philippe IV, along with some 200 noble young men from the most prestigious families in the kingdom, were officially knighted.

At the second table, were seated: Yolande of Dreux, Dowager Duchess of Brittany, her sister-in-law Pernelle de Sully, the Dowager Countess of Dreux, her mother Marguerite de Beaumez, Blanche of Brittany, sister of Mahaut of Artois, Jeanne of and Marie of Artois, her daughters, Isabelle de Rumigny, Dowager Duchess of Lorraine, Elisabeth of Austria, Duchess of Lorraine and daughter of Emperor Albert I; the cousins of Marguerite of Burgundy Marie of Hainaut, Jeanne d'Argies, Countess of Soissons, perhaps Béatrice, Princess of Hungary and Dauphine of Viennois, Marie of Flander, Countess of Boulogne, Isabelle of Lorraine, Countess of Vaudémont, Agnès de Brienne, Countess of Joigny, her daughter Jeanne of Joigny, Eleonore of Savoy, Countess of Forez, Louise de Beaumetz, Countess of Sancerre, Marie, Countess of Roussis, Jeanne de Gîgne, Countess of Eu, perhaps Béatrice of Burgundy, Dowager Countess of La Marche, Marguerite of Burgundy's aunt, Isabeau de Coucy, sister of Mahaut de Châtillon-Saint Pol; the ladies of Jeanne of Burgundy: Alix de Joinville, lady of Beaufort, wife of John of Lancaster, Alix de Clermont-Nesle, lady of Nesle, Jeanne de Tancarville, Vicountess of Melun, Isabelle de Forez, wife of the governor of Lyon, Jeanne de Dampierre, Jeanne de Vendôme.

A third table was counting at least: Marie de Vaucemain, lady of Chey, a lady of Marguerite's, Alips de Mons, wife of Enguerrand de Marigny, Roberte de Beaumetz, her daughter-in-law and a cousin of the Countess of Sancerre, Jeanne de Machot, lady of Viarmes, daughter of Saint Louis' chamberlain and the wife of Philippe IV's chamberlain, Marguerite des Bars, wife of another chamberlain of Philippe IV's, Isabeau of Burgundy, wife of a chamberlain of Louis, King of Navarre, Isabeau de Rosny, her mother-in-law, Marguerite de la Roüe, Jeanne de Courpalay and Béatrix, widow of Nogaret. Wives of other clerks were also in attendance, potentially along female members of the bourgeoisie. — Gaëlle Audéont, Philippe le Bel et l'Affaire des Brus, 1314

320 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every English Princess Ever

You’ve heard of Every Queen of England Ever, now I present to you another product that proves I have way too much time on my hands! If you notice any mistakes, please point them out to me kindly. I am sorry I do not know everything, but there is no reason to be rude. 😁

Æthelswith - Daughter of Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh. She married King Burgred of Mercia in 853, making her the Queen of Mercia.

Æthelflæd - Daughter of Alfred the Great and Ealhswith. When her husband Æthelred, Lord of Mercians died in 911, she became Lady of the Mercians, and reigned for seven years.

Æthelgifu - Daughter of Alfred the Great and Ealhswith. When Alfred founded Shaftesbury Abbey in 890, he made her its first abbess.

Ælfthryth - Daughter of Alfred the Great and Ealhswith. Her marriage to Baldwin II, Count of Flanders made her Countess of Flanders.

Eadgifu - Daughter of Edward the Elder and his second wife Ælfflæd. She was Queen of West Francia by her marriage to Charles III.

Eadhild - Daughter of Edward the Elder and his second wife Ælfflæd. She married Hugh, Duke of the Franks in 937.

Eadgyth - Daughter of Edward the Elder and his second wife Ælfflæd. She married Otto in 930, who became Otto I, King of Germany in 936, also making her Queen of Germany.

Eadburh - Daughter of Edward the Elder and his third wife Eadgifu. She lived her life as a nun.

Godgifu - Daughter of Æthelred the Unready and his second wife Emma of Normandy. Her marriage to Eustace II, Count of Boulogne made her Countess of Boulogne.

Gunhilda - Daughter of Cnut the Great and his second wife Emma of Normandy. She became Queen of Germany when she married Henry III.

Gytha - Daughter of Harold II and Edith Swanneck. She was Princess of Rus from her marriage to Vladimir II Monomakh.

Adeliza - Daughter of William the Conqueror and Matilda of Flanders.

Cecilia - Daughter of William the Conqueror and Matilda of Flanders. She was entered into the Abbey of the Holy Trinity of Caen at a young age, and became Abbess in 1112.

Constance - Daughter of William the Conqueror and Matilda of Flanders. She became Duchess of Brittany when she married Alan IV, Duke of Brittany.

Adela - Daughter of William the Conqueror and Matilda of Flanders. She was Countess of Blois by her marriage to Stephen, Count of Blois, and was regent of Blois two times.

Empress Matilda - Daughter of Henry I and Matilda of Scotland. She became Holy Roman Empress in 1114, and acted as Queen of England from 1141 to 1148, but was disputed.

Marie I - Daughter of Stephen and Matilda I, Countess of Boulogne. When her brother William I, Count of Boulogne died childless in 1159, Marie succeeded him as the Countess of Boulogne.

Matilda - Daughter of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. She was Duchess of Saxony and Bavaria from her marriage to Henry the Lion.

Eleanor - Daughter of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. She became Queen of Castile and Toledo when she married Alfonso VIII.

Joan - Daughter of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. She was Queen of Sicily by her marriage to William II until his death in 1189, and became Countess of Toulouse when she married Raymond VI in 1196.

Joan - Daughter of John and Isabella of Angoulême. She was Queen of Scotland by her marriage to Alexander II.

Isabella - Daughter of John and Isabella of Angoulême. She was Holy Roman Empress and Queen of Sicily and Germany by her marriage to Frederick II.

Eleanor - Daughter of John and Isabella of Angoulême. She was Countess of Pembroke by her first marriage to William Marshal, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, and Countess of Leicester by her second marriage to Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester.

Margaret - Daughter of Henry III and Eleanor of Provence. She was Queen of Scotland by her marriage to Alexander III.

Beatrice - Daughter of Henry III and Eleanor of Provence. (Her wikipedia says she was Countess of Richmond, which I’m not sure is true or not. Her husband was the Duke of Brittany, but it is possible she somehow inherited the title in her own right).

Katherine - Daughter of Henry III and Eleanor of Provence. She passed away at the age of three.

Eleanor - Daughter of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile. She was Countess of Bar by her marriage to Henry III, Count of Bar.

Joan of Acre - Daughter of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile. She was Countess of Hertford and Gloucester by her first marriage to Gilbert de Clare, 7th Earl of Gloucester and 6th Earl of Hertford.

Margaret - Daughter of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile. She was Duchess of Brabant, Lothier and Limburg by her marriage to John II.

Mary of Woodstock - Daughter of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile. She was a nun at Amesbury Priory.

Elizabeth of Rhuddlan - Daughter of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile. She was Countess of Holland by her first marriage to John I, and Countess of Hereford by her second marriage to Humphrey de Bohun, 4th Earl of Hereford.

Eleanor of Woodstock - Daughter of Edward II and Isabella of France. She was Duchess of Guelders by her marriage to Reginald II, and was regent of Guelders while her son was still young.

Joan of the Tower - Daughter of Edward II and Isabella of France. She got her name from being born in the Tower of London. Joan was Queen of Scotland by her marriage to David II.

Isabella - Daughter of Edward III and Philippa of Hainault. She was Countess of Bedford and Lady of Coucy by her marriage to Enguerrand VIII, and was made a Lady of the Garter in 1376.

Joan - Daughter of Edward III and Philippa of Hainault. She died during the Black Death at the age of fourteen.

Mary of Waltham - Daughter of Edward III and Philippa of Hainault. She was Duchess of Brittany by her marriage to John IV, Duke of Brittany, and was made a Lady of the Garter in 1378. She died young at the age of sixteen.

Margaret of Windsor - Daughter of Edward III and Philippa of Hainault. She was Countess of Pembroke by her marriage to John Hastings, 2nd Earl of Pembroke. Margaret died young at the age of fifteen.

Blanche of Lancaster - Daughter of Henry IV and Mary de Bohun. She was Electress Palatine by her marriage to Louis III, Electress Palatine.

Philippa of Lancaster - Daughter of Henry IV and Mary de Bohun. She was Queen of Denmark, Sweden and Norway by her marriage to Eric III, VIII & XIII.

Elizabeth of York - Daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. She was Queen of England by her marriage to Henry VII.

Mary of York - Daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. She died at the age of fourteen.

Cecily of York - Daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. She was First Lady of the Bedchamber to her sister, Elizabeth of York, from 1485 to 1487. Cecily was Viscountess Welles by her marriage to John Welles, 1st Viscount Welles.

Margaret of York - Daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. She died at just eight months old.

Anne of York - Daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. She was First Lady of the Bedchamber to her sister, Elizabeth of York, from 1487 to 1494.

Catherine of York - Daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. She was Countess of Devon by her marriage to William Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon.

Bridget of York - Daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. She was a nun at Dartford Priory.

Margaret Tudor - Daughter of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York. She was Queen of Scotland by her marriage to James IV of Scotland.

Elizabeth Tudor - Daughter of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York. She died at the age of three.

Mary Tudor - Daughter of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York. She was Queen of France by her first marriage to Louis XII of France, and Duchess of Suffolk by her second marriage to Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk.

Mary I - Daughter of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon. She was Queen of England from 1553 to 1558, and Queen of Spain by her marriage to Philip II of Spain.

Elizabeth I - Daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn. She was Queen of England from 1558 to 1603.

Elizabeth Stuart - Daughter of James VI & I and Anne of Denmark. She was Electress Palatine and Queen of Bohemia by her marriage to Frederick V.

Margaret Stuart - Daughter of James VI & I and Anne of Denmark. She died at the age of one year old.

Mary Stuart - Daughter of James VI & I and Anne of Denmark. She died at the age of two years old.

Sophia Stuart - Daughter of James VI & I and Anne of Denmark. She lived for just one day.

Mary - Daughter of Charles I and Henrietta Maria. She was Princess of Orange and Countess of Nassau by her marriage to William II, Prince of Orange.

Elizabeth Stuart - Daughter of Charles I and Henrietta Maria. She died at the age of fourteen.

Anne Stuart - Daughter of Charles I and Henrietta Maria. She died at the age of three.

Henrietta - Daughter of Charles I and Henrietta Maria. She was Duchess of Orléans by her marriage to Philippe I, Duke of Orléans.

Mary II - Daughter of James II & VII and Anne Hyde. She was Queen of England from 1689 to 1694.

Anne - Daughter of James II & VII and Anne Hyde. She was Queen of England and Great Britain from 1702 to 1714.

Louisa Maria Stuart - Daughter of James II & VII and Mary of Modena. She died at the age of nineteen.

Sophia Dorothea of Hanover - Daughter of George I and Sophia Dorothea of Celle. She was Queen of Prussia and Electress Brandenburg by her marriage to Frederick William I of Prussia.

Anne - Daughter of George II and Caroline of Ansbach. She was Princess of Orange by her marriage to William IV, Prince of Orange.

Amelia of Great Britain - Daughter of George II and Caroline of Ansbach.

Caroline Elizabeth of Great Britain - Daughter of George II and Caroline of Ansbach.

Mary of Great Britain - Daughter of George II and Caroline of Ansbach. She was Landgravine of Hesse-Kassel by her marriage to Frederick II, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel.

Louise of Great Britain - Daughter of George II and Caroline of Ansbach. She was Queen of Denmark and Norway by her marriage to Frederick V of Denmark.

Charlotte - Daughter of George III and Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. She was Duchess, Electress and Queen of Württemberg by her marriage to Frederick I of Württemberg.

Augusta Sophia - Daughter of George III and Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz.

Elizabeth - Daughter of George III and Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. She was Landgravine of Hesse-Homburg by her marriage to Frederick VI, Landgrave of Hesse-Homburg.

Mary - Daughter of George III and Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. She was Duchess of Gloucester and Edinburgh by her marriage to Prince William Frederick, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh.

Sophia - Daughter of George III and Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz.

Amelia - Daughter of George III and Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz.

Charlotte of Wales - Daughter of George IV and Caroline of Brunswick. She was their only child, and died before both of them.

Charlotte Augusta Louisa of Clarence - Daughter of William IV and Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen. She died shortly after birth.

Elizabeth Georgiana Adelaide of Clarence - Daughter of William IV and Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen. She died shortly after birth.

Victoria - Daughter of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. She was German Empress and Queen of Prussia by her marriage to Frederick III, German Emperor.

Alice - Daughter of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. She was Grand Duchess of Hesse and Rhine by her marriage to Louis IV, Grand Duke of Hesse.

Helena - Daughter of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. She was Princess of Schleswig-Holstein by her marriage to Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein.

Louise - Daughter of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. She was Duchess of Argyll and Viceregal of Canada by her marriage to John Campbell, 9th Duke of Argyll.

Beatrice - Daughter of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. She was Princess of Battenberg by her marriage to Prince Henry of Battenberg.

Louise of Wales - Daughter of Edward VII and Alexandra of Denmark. She was Duchess of Fife by her marriage to Alexander Duff, 1st Duke of Fife.

Victoria of Wales - Daughter of Edward VII and Alexandra of Denmark.

Maud of Wales - Daughter of Edward VII and Alexandra of Denmark. She was Queen of Norway by her marriage to Haakon VII of Norway.

Mary of York - Daughter of George V and Mary of Teck. She was Countess of Harewood by her marriage to Henry Lascelles, 6th Earl of Harewood.

Elizabeth II - Daughter of George VI and Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon. She is Queen of the UK from 1952 to present.

Margaret Rose of York - Daughter of George VI and Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon. She was Countess of Snowdon.

Anne of Edinburgh - Daughter of Elizabeth II and Prince Philip.

#british history#historical women#empress matilda#elizabeth of york#margaret tudor#mary i#elizabeth i#british royal family

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daughters of the Breton Dukes, part II

Mari, comtesse de Saint-Pol. Daughter of Yann II, dug Breizh and Beatrice of England, Countess of Richmond. Mother of Mahaut de Châtillon, comtesse de Valois; Beatrice de Châtillon, dame de Crèvecœur; Isabeau de Châtillon, dame de Coucy; Marie de St Pol, Countess of Pembroke; Éléonore de Châtillon, dame de Granville; and Jehanne de Châtillon, dame de Maisy.

Blanche, dame de Conches. Daughter of Yann II, dug Breizh and Beatrice of England. Mother of Marguerite d’Artois, comtesse d’Évreux; Jehanne d’Artois, comtessa de Fois; Marie d’Artois, Markgrafin van Namen; and Jehanne d’Artois, comtesse d’Aumale.

Eleonora, abbesse de Fontevraud. Daughter of Yann II, dug Breizh and Beatrice of England.

Beatriks, dame de Laval. Daughter of Arzhur II, dug Breizh and Yolande de Dreux. Mother of Catherine de Laval, dame de Villemomble,

Janed, dame de Cassel. Daughter of Arzhur II, dug Breizh and Yolande de Dreux. Mother of Yolande de Flandre, comtesse de Bar.

Alis, comtesse de Vendôme. Daughter of Arzhur II, dug Breizh and Yolande de Dreux. Grandmother of Catherine de Vendôme, comtesse de La Marche.

Janed, dugez Breizh. Daughter of Guy VII, kont Pentevr and Jehanne d’Avaugour. Mother of Marc’harid Bleaz, comtesse d’Angoulême and Mari Bleaz, duchesse d’Anjou.

Janed, Baroness Drayton. Daughter of Yann Moñforzh and Jehanne de Flandre, dugez Breizh.

Marc’harid Bleaz, comtesse d’Angoulême. Daughter of Janed, dugez Breizh and Charles de Blois.

Mari Bleaz, duchesse d’Anjou. Daughter of Janed, dugez Breizh and Charles de Blois. Grandmother of Marie d’Anjou, reine de France and Yolande d’Anjou, comtesse de Montfort. Great-grandmother of Yolande d’Anjou, duchesse de Lorraine and Marguerite d’Anjou, Queen of England.

#historyedit#house of dreux#bretoned#medieval#french history#european history#women's history#history#royalty aesthetic#nanshe's graphics

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Philippe I, Duc d'Orléans (Philippe de France)

Philippe I, duc d'Orléans was born on September 21, 1640 in Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France. His parents were King Louis XIII [1601-1643] and Queen Anne of Austria [1601-1666]. He had one elder brother, King Louis XIV [1638-1715].

In 1661 he married Henrietta Anne of England [1644-1670]. Together they had four [4] children: Marie Louise d'Orléans [1662-1689], Philippe Charles d'Orléans, Duc de Valois [1664-1666], stillborn daughter [July 09, 1665], and Anne Marie d'Orléans [1669-1728]. After Henrietta's death, Philippe married Princess Elisabeth Charlotte of the Palatinate [1652-1722] in 1671. Together they had three [3] children: Alexandre Louis d'Orléans, Duc de Valois [1673-1676], Philippe II, Duc d'Orléans [1674-1723] and Élisabeth Charlotte d'Orléans [1676-1744].

Philippe was styled the Duke of Anjou from birth. He became the Duc d'Orléans in 1660 after the death of his Uncle Gaston. In 1661 he also received the dukedoms of Valois and Chartres, and the lordship of Montargis. Following his victory in battle in 1671, Louis XIV gave him the dukedom of Nemours, the marquisates of Coucy and Folembray, and the countships of Dourdan and Romorantin. Upon the death of Mademoiselle in 1693, Philippe acquired the dukedoms of Montpensier, Châtellerault, Saint-Fargeau and Beaupréau. He also became the prince of Joinville, Count of Mortain, Bar-sur-Seine, and Viscount of Auge and Domfront. Philippe was also given the nickname of "the grandfather of Europe."

He was a successful military commander during the War of Devolution in 1667. In 1676 and 1677 he took part in the sieges in Flanders, and was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant General. The most impressive victory won under Philippe's command took place on April 11, 1677: the Battle of Cassel against William III, Prince of Orange.

Philippe de France died on June 09, 1701 (aged 60) in Château de Saint-Cloud, France. The cause of death was from a fatal stroke. He was laid to rest on June 21, 1701 at the Basilica of Saint-Denis, France

#french history#history#royalty#personal life#philippe i duke of orléans#philippe of france#duc d'orléans#duke of orleans#philippe I#titles#military#world history

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saturday 26 May 1838

8

12 ¼

fine morning F61 ½° at 8 ½ am A- went to the cathedral about 8 or after to sketch the interior and returned at 9 35 – I sat writing till 10 – then breakfast – changed our room – from the small one to the next adjoining a large very good room and breakfasting and moving our things till 12 – our garçon Paul Voisin a nice civil good countenanced unmarried aetatis 31 man from Lyons – does not like here – would be glad to be in a private house again – would be glad to go with us – lived 15 years with la marquise de Montague – was then in the army – then not getting a good place at Lyons came to Paris and from there here – in bed at 12 or 2 and up at 4 – so hard a place, nobody could stay long – he makes 800fr. a year – but would rather have less in a different place – had 350 fr. a year with the marquise de M- and livery – she lived in the r. de la université, but is not now in Paris – lives in the country – A- and I out at 12 35 – took a commissionaire to shew us the way, and then sent him home – Mr. Mumm or somebody, a very civil young man, protestant it seemed, and speaking English very fairly – a German shewed us over the cellars, and afterwards shewed us into a large good salon, and gave us champagne and biscuits – the wine Mousseux and very fair but not so good as Moets’ of Epernay in 1833. should I have as good of Moet at 3/. a bottle? ordered a dozen of his 1ere qualité at 4/50 per bottle to be sent off on Monday and would be in Paris on Tuesday or Wednesday to my address rue St. Victor n° 27 à Paris – thought we might get this dozen over to England for Lady Stuart – en petite cadeau – about an hour at the cellars (at Mr. Mumms’) underground and above – 3 stories of cellars to the depth of 36 to 40 ft. ventilated by grates communicating from the bottom cellar to the top – each story divided into separate vaults perhaps the loftiest 7 or 8ft. high in the centre – perhaps 4 or 5 yards wide and 20+ long – in the lowest story 3 men corking – one filling up the bottles – another putting in the cork, and driving it down with a machine (has only had it about 15 months) on the principle of a corn or button-stamping machine, and the 3rd man tying down the corks, (the tightness gained by a small steel thing round which the string is turned and held fast while the other end is pulled tight) – It is not long since everybody left off gaudon (rosin) and covered the corks with lead-paper – a great improvement

Monday 28 May 1838. no good wine in champagne says our landlord of the Ecu at Epernay since the year 1834.

asked for champagne tranquille – cannot have it now – not till next year – not ripe enough now – that of 1834 will not be ripe till next year – taken with the double-incline clearing racks the bottles ranged in an angle = about 25°? require turning twice a day for 2 or 3 weeks till all the sediment has sunk down to the cork – then the cork taken out (a difficult operation saw it done) and with the cork out gushes the sediment in the froth that escapes and the bottle being refilled is immediately re-corked – vintage in October – wine remains in cash till April May or June – about 6 months – Mr. Mumm has no vineyards of his own – buys the grapes – shewed us his great ton = 19,000 bottles = 70 such casks as we saw lying about – sends wine to America in boxes containing 12 bottles and 50 ditto has a house in London, Francfort and Cologne – Inquired respecting the ventilation of cellars – he said wine should have good pure air – Madeira should be kept warm and may do without air, but good air cannot do it any harm if the temperature be attended to – the breakage of champagne = 50p.c. the time of year now coming on – best to order champagne for a years’ consumption – should not be kept too long – he owned that the Bordeaux wines (Claret) for the English market were mixed with hermitage and brandy – on leaving Mr. Mumms’ at 1 55 sauntered in the little Jardin des Plantes – nothing particular in it – 2 or 3 little serres, not much in them – then to the Cours the very nice shaded promenades – then Champs Elysées of Rheims – very pretty cool and pleasant (hot and very fine sun today) sat there writing in pencil in my rough note book all the above of today till now 2 ¾ - and then to the cemetery close by – i.e. close by the Porte de Mars leading to Flanders (the gate by which we entered yesterday) and the ‘Mission’ i.e. croix de la mission erected in 1825, and now turned to a monument to the memory of the brave who died fighting for the liberty of France (viz. the revolutions of the 3 days of July 1830) – sometime in the cemetery spite of boiling sun – among the tombeaux and epitaphs one of the latter by a father to the memory of his daughter, Marie Antoniette Sophie l’Inglois decêdée Thursday 5 December 1822 dans sa 21me année – after 10 foregoing lines ends thus

‘ô mon chere enfant, attends en paix

ce père malheureux ! attends-le sous cette terre

Qui d’après un homme religieux et sensible,

‘n’est que la cendre des morts pétrie avec les larmes

de vivans’ pretty idea

not aware at this moment that the ancien porte de Mars (arc de triomphe of the Romans) was so near

from the cemetery thro’ the streets and marché to the palais archiépiscopale

the archbishop M. le cardinal de Couci set off to Paris a day or 2 before the outburst of the revolution of July 1830, and has never been here since – at Goritz with the ex-royal family – the bishop of Numidie does the duties of the archbishop – the archbishop much regretted – a very good man – did a great deal of good –the palais worth seeing the grande salle surrounded by the pictures of the king crowned here from Clavis downwards very handsome – pity that damp is spoiling some of the pictures e.g. Louis XVI. at the end of the salle – Charles X. taken away – the picture still in the palais but his place in the salle vacant, and several fleurs de lis here and there defaced – (as also the fleurs de lis on the shield of Louis 15 in the Place royale – how puerile!) – the grande salle 130x36 pieds and height = about 36 pieds up to the square – ceiling domed – large poutres (beams) across the room partly gilt with 2 rings in each beam towards the side of the room for suspending 2 chandeliers – 4 windows on each side the great entrance door by flight of steps from without – 4 doors on the opposite side of the room – the great fire-place at the end of the room and over it St. Remy crowning Clovis – shewn into what Charles x intended turning into the chapel – the painted glass windows put in – but all stopt by the revolution – this place was the palais de justice after the revolution of 1789 and 3 stories of prisonniers were in this very spot – the duke of Orelans was lately at our hotel (the Lyon d’or) but did not see the Palace – no! said I, he is still a Bourbon, and the sight could not be agreeable – from here went home at 4 ½ for A- to have wine and biscuit and then out again at 4 52 and off to the church of St. Remy – a 20 minutes walk and there at 5 ¼ - under repair – expected to be done in 2 years from this time – very curious old church – the whole of the nave boarded off – had been new roofed and now full of workmen – 2 stories of double aisle round the apsis and choir and a narrow gallery above the upper story immediately under the painted windows – do not remember to have seen this sort of 2 storied double-aisle – went up to the upper story – same dimensions apparently even as high as the story below – the vitreaux – (painted glass) – very ancient – date not known – supposed to be as old as the church – evidently very ancient – all the ceilings of aisles and choir stone-work plastered and painted in imitation of brick-work – the new vaulting (new roof of the nave) done in wood – the old stone roof too heavy on the walls – the 2 stories of double aisle run all round the nave too – see as we return, that the new roof is not quite so steep as the old one – as seen from the old walls of the town the eves are all in one line but the ridge of the old roof of the choir is about 3ft. higher than the ridge of the new roof of the nave – just peeped into the nave after having seen the high altar and chasse containing the relies of St. Remy – the chasse of solid silver before the revolution of 1789 – now of cuivre argenté – the relies exposed to the faithful

SH:7/ML/E/21/0110

for 9 days in October every year – the figures round the high altar not finished sculptured at the back because stood originally against a wall – done under the orders of a cardinal of Lorraine 300 or 400 years ago – interesting as representing in marble statues the 6 ecclesiastical and 6 lay paises de France and their officers who assisted at the sacres (coronations) of the kings of France – looking towards the altar

the left

‘Duke de Bourgogne’ holding the crown

D. de Normandie – a standard

D. de Aquitaine – a standard

Comte ‘de champagne’ – a standard

C. de Flandre – the sword

C. de Toulouse – the spurs

the right

archduke de Rheims holding sa croix

Ev. duke de Laon – a crosier et l’ampoule

Ev. d. de Langres – a crosier et containing the oil and sceptre

Ev. comte de Beauvais – a crosier

Ev. c. de Chalons – a crosier and the ring

Ev. c. de Noyon – a crosier et la selle the kings’s saddle

immediately at the back of the altar in the space between the last Evêque and last court is a St. Remy seated in his archiepiscopal robes and mitre teaching Clovis kneeling at his feel and a Diacre or assistant holding the cosier and an open book – Left the church (much interested) at 6 20 – sauntered back along the boulevard very lately planted with young elms – cart road in the middle and 2 allées (promenades) (old rampart) the Vesle river running close along its foot on the other side the old wall – on our right towards the town, great deal of garden ground – pépinières and sale vegetable gardens – delighted with our walk back – nowhere such good views of the exterior of the cathedral – too short – too lumping as a whole – wants the lantern tower the lengthiness of York minster, and its freedom from flying buttresses at the east end which look like steps to graduate the high roof gently down to the ground – the effect of this is bad – as if the building could not support its height at that end – never travel without a view of York minster – take it all in all, has it an equal in the world? when very near our hotel at 7 the light so beautiful on the cathedral turned into a courtyard for a better view – the gentleman of the house civilly asked us in and the wife shewed us in the garden – she said the effect would be still better in about an hour – she regretted the great numeros of pigeons jackdaws, crows etc that inhabited the exterior of the building – to us these birds give life to the scene and improve the picturesque – she said the crows assembled on the wire all along the ridge of the roof so as sometimes to form an almost continuous line from end to end, and all regularly flew away to les champs at 9pm – as good as a clock for 9pm we inquired about Mr. Mumm as to the street in which he lived – she did not know the name – supposed we had seen the cellars of Mr. Muller or Mr. Roeder (a German we said he spoke English well and was a protestant) – asked who was really the most renommé négociant en vins in Reims – Madame Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin- I said the town was full of dyers – yes! but only 6 or 7 great dyers in the town – It turned out her husband was a dyer and also a wine merchant – she said we ought to see les filatures en laine (woollen spinning mills) – it seems they have power looms here – she says trade has been very bad, but is now reviving or revived and pretty goof again – Had ordered dinner at 7 – not in till 7 ½ - dinner immediately but the lateness an excuse for a bad dinner – no épinards – nothing left – I sent for one mutton cutlet for I had literally nothing but cold fish not eating the bit of beef or the little redone overdone poulet or asparagus – sat over dinner and dessert till 10 – then wrote till 11 – very fine day – F67° at 11 pm

1 note

·

View note

Text

On September 29th 1240 Margaret of England, daughter of Henry III of England and Eleanor of Provence, was born at Windsor Castle to King Henry III of England and his wife, Eleanore of Provence.

The second of five children, the first few years of Margaret’s life were spent quietly in the care of what has been described as an affectionate and close family. Her first appearance in historical record came when she was three years old and she took part in a royal event in London with her brother, the future Edward I, aye him of Longshanks infamy.

Margaret’s paternal aunt, Joan, had been married to King Alexander II of Scotland before she died in 1238 and so, as former brothers-in-law, Henry III and Alexander II had a good relationship and were quite fond of one another. When Alexander II welcomed the birth of a son with his second wife, Marie of Coucy, in September 1241 it was only natural that the possibility of a marriage between the young heir to the Scottish throne and Henry III’s eldest daughter be discussed. Margaret and Alexander III were betrothed when she was just four years old.

Alexander became King of Scotland at the age of seven when his father died in 1249 and Margaret became Queen of Scots at the age of eleven on 26 December 1251 when she was officially married Alexander II at York Minster. The marriage was the third youngest of monarchs in British history.

Removed to the harsh climate of Edinburgh and kept quite separate from her husband Margaret became lonely and homesick, she wrote often to her parents and mentioned she was being treated poorly. This created tension between England and Scotland and it was not until 1255 that this was eventually settled and the young Queen was given an opportunity to reunite with her parents at Wark. The visit vastly improved Margaret’s spirits and she returned to Edinburgh feeling much revived.

In 1257 Margaret and Alexander III were held captive by the powerful Comyn family, who demanded the expulsion of all foreigners from Scotland it was only through the intervention of Margaret’s father and the regency council that they were freed. They went on to have three children: Margaret, Alexander and David. Margaret was the only one to live a full life, the boys died aged 20 and 19 respectively. She gave birth to The Maid of Norway, from a previous post this week.

Though her life was quiet there is some scandal which remains unresolved to this day. Margaret had in her employ a young courtier – given to her by her brother – who claimed to have killed her uncle, Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester. One day, while walking with a group of ladies and courtiers along the River Tay Margaret is said to have become annoyed with the courtier and either pushed, or had him pushed, into the river. Playful laughter quickly turned to shock, however, when the man was swept to his death by the powerful current. Margaret was said to have been saddened by the event but we will never know exactly what part she played and how she truly felt.

Margaret died at the age of thirty-four on 26 February 1275 at Cupar Castle after falling ill while visiting Fife. She is buried at Dunfermline Abbey in Fife.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nicolas Oudinot & Eugénie de Coucy (1/2)

[...] De tout temps les parvenus riches et glorieux ont été bien accueillis dans les antiques familles dont le blason se dédore. Sans doute, les fils de la Révolution n’étaient plus, auprès de leurs épouses, de la première jeunesse. Leur renom de bravoure, le prestige de leurs cicatrices, l’éclat de leurs titres, y suppléaient. Quel beau rêve, pour des adolescentes à peine libérées du pensionnat, que d’être recherchées par de brillants conquérants connus et redoutés de toute l’Europe! La maréchale Oudinot, duchesse de Reggio, a raconté comment, au moment de quitter sa plus intime camarade d’études, elle échangea avec elle une promesse qui révèle toute l’étendue des perspectives alors ouvertes aux jeunes personnes de son monde. Les deux jeunes filles, Eugénie de Coucy et Pauline de Montendre, se promenaient en devisant sur leur avenir. “Promets-moi, dit cette dernière, de m’annoncer ton mariage comme je te préviendrai du mien, par le simple envoi d’un anneau d’or: les détails viendront après.” Eugénie accepta d’enthousiasme: “ Oui, renchérit-elle, mais, si ton futur ou le mien est décoré de la Légion d’Honneur, il faudrait mettre une étoile à l’anneau. - C’est bien, mais deux étoiles s’il est baron - Alors, trois s’il est comte. - Et s’il est duc ? - Ah! alors, ce sera par un jonc de diamant que l’on annoncerait la nouvelle.” Mademoiselle de Coucy riait de bon coeur en bâtissant ce château en Espagne, mais deux ans plus tard ce fut elle qui envoya le jonc de diamant. Elle n’avait pas vingt ans lorsqu’elle fut remarquée par son compatriote, le maréchal Oudinot, qui songea d’abord à en faire la femme de son fils aîné Victor. Bientôt séduit pour son propre compte, et d’ailleurs désireux de recréer un foyer malgré ses quarante-quatre ans et ses six enfants du premier lit, le duc de Reggio demanda, à la fin de 1811, la main d’Eugénie de Coussy ou Coucy, qui lui fut accordée avec empressement. Le mariage fut célébré en janvier 1818. La jeune femme, âgée de vingt ans et parfaitement élevée à la mode provinciale, fut très fière, malgré la noblesse de sa propre famille, de se voir soudain duchesse de l’Empire et femme d’un héros couturé de blessures. Elle prit vite de l’ascendant sur ce mari très amoureux qui adoucissait pour elle les angles de son rude caractère.

Louis Chardigny, Les Maréchaux de Napoléon, Bibliothèque Napoléonienne, P. 221-223

“The rich and glorious upstarts have always been welcomed in ancient families whose coat of arms needs some gilding. No doubt, the sons of the Revolution were no longer young, compared with their wives. Their renown for bravery, the prestige of their scars, the luster of their titles, made up for it. What a beautiful dream, for adolescent girls barely released from boarding school, to be sought after by brilliant conquerors known and feared all over Europe! The maréchale Oudinot, Duchess of Reggio, related how, when leaving her most intimate fellow student, she exchanged with her a promise which revealed the full range of perspectives then open to young people in her world. The two young girls, Eugénie de Coucy and Pauline de Montendre, were walking around, talking about their future. "Promise me," said the latter, "to announce your marriage to me as I will warn you about mine, just by sending a gold ring: the details will come later." Eugénie accepted with enthusiasm: “Yes, she adds, but, if your husband-to-be or mine is decorated with the Légion d’Honneur, you should put a star on the ring. -That's fine, but two stars if he's a baron. - So, three if he's a count. - What if he's a duke? - Ah! then the news will be announced by a diamond ring. " Mademoiselle de Coucy laughed heartily when building this castle in the sky, but two years later it was she who sent the diamond ring. She was not yet twenty when she was noticed by her compatriot, Marshal Oudinot, who first thought of making her marry his eldest son Victor. Soon seduced on his own account, and moreover eager to make himself a new home despite his forty-four years and his six children from a first marriage, the Duke of Reggio asked, at the end of 1811, for Eugenie de Coussy (or Coucy)’s hand in marriage, which was eagerly granted to him. The marriage was celebrated in January 1818. The young woman, aged twenty and perfectly brought up in the provincial fashion, was very proud, despite the nobility of her own family, to see herself suddenly Duchess of the Empire and wife of a wounded hero. She quickly gained control over this very besotted husband who softened for her the angles of his harsh temper.”

#napoleonic#louis chardigny#les maréchaux de napoléon#nicolas oudinot#eugénie de coucy#marshals and wives

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝒮𝑒𝓇𝓋𝒾𝒸𝑒 𝒮𝓊𝓃𝒹𝒶𝓎: Not Finished!

𝐻𝑜𝓃𝑜𝓇

The Most Noble Order of the Garter

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

𝐻𝑜𝓃𝑜𝓇 𝑅𝒶𝓃𝓀

The Most Senior Order of Knighthood in the British Honors System. This honor outranks The Victoria Cross & The George Cross,

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

𝐹𝑜𝓊𝓃𝒹𝑒𝓇

King Edward III of England in 1348

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

𝐻𝒾𝓈𝓉𝑜𝓇𝓎 𝑜𝒻 𝓉𝒽𝑒 𝐻𝑜𝓃𝑜𝓇

𝒯𝒽𝑒 𝒞𝓇𝑒𝒶𝓉𝒾𝑜𝓃

The Order of the Garter was created on April 23rd, 1344 & was created to help King Edward’s claim to the French throne. The Order is dedicated to Saint George because he is the Patron Saint of England. The Most Noble Order of the Garter was inspired by the Spanish Order of the Band, which was created in 1330.

𝑀𝑒𝓃𝓉𝒾𝑜𝓃𝓈 𝑜𝒻 𝒯𝒽𝑒 𝒢𝒶𝓇𝓉𝑒𝓇 𝒾𝓃 𝐹𝒶𝓂𝑜𝓊𝓈 𝒲𝓇𝒾𝓉𝓉𝑒𝓃 𝒫𝒾𝑒𝒸𝑒𝓈

(Joanot Martorell)

(John of Gaunt Duke of Aquitaine)

(Countess Isabella of Bedford)

The earliest mention of The Most Noble Order of the Garter was mentioned in Tirant to Blanch by Joanot Martorell, a chivalric romance piece of literature (A literary genre of high culture), which was written in Catalan (Now called Valencian Language) in 1490. King Edward III’s wardrobe shows that Garter habits first issued in 1348. The Middle English poem “Sir Gawain & the Green Knight,” which was written in the late 14th century, mentions The Most Noble Order of the Garter. In the poem, a girdle is very similar to a garter (in an erotic way). The poem also mentions a different version of the Order’s motto which is written “Corsed worth cowarddyse and couetyse bope,” which translates to “Cursed be both cowardice and coveting.” The author of the poem is argued by scholars but there is a connection between two candidates: John of Gaunt Duke of Aquitaine & Enguerrand VII de Coucy. Enguerrand was married to King Edward III’s daughter Countess Isabella of Bedford & was received the Order of the Garter on their wedding day.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

𝐿𝑒𝑔𝑒𝓃𝒹𝓈

(King Richard 1 of England)

Various stories & legends surround the origin of The Most Noble Order of the Garter.

The most popular story involves Catherine (Grandison) Montagu The Countess of Salisbury. It is said, that the countess’s garter slipped off from her leg, while she was dancing at a court ball that took place in Calais, France. When the garter slipped from the countess’s leg, courtiers laughed & just watched the scene happen. The King saw what had happen & returned the garter to the Countess exclaiming “Honi soit qui mal y pense!" Which translates in English to “Shame on him who thinks ill of it!” This is saying that is written on the The Most Noble Order of the Garter.

The earliest written story dates back to the 1460′s. A garter in the mid-14th century, was seen mostly as a item of male attire. Looking back on the story, the garter (that was seen as item of female underclothing), actually has the garter stated as a symbol of a band of knights.

A 2nd story is connected to King Richard I of England. In the 12th century, King Richard was inspired by St. George the Matyr, while he was fighting in the Crusades (A series of religious wars in Western Asia & Europe between the 11th & 17th century). The king tied garters around the legs of his knights, who won the battle. King Edward, recalled the story of King Richard during the 14th century when founding the The Most Noble Order of the Garter. This story is actually recounted in a letter to the Annual Register (A long-established reference work, written and published each year, which records and analyses the year's major events, developments and trends throughout the world) that was written in 1774.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

𝒟𝑒𝓈𝒾𝑔𝓃 𝑜𝒻 𝒯𝒽𝑒 𝐸𝓂𝒷𝓁𝑒𝓂

The emblem for The Most Noble Order of the Garter is a garter with a written Middle French Moto that says "Honi soit qui mal y pense” which means “Shame on him who thinks evil of it” & the motto is written in gold lettering. The motto refers to King Edward’s claim to the French throne. The use of the garter with the emblem, derived from straps that are used to fasten armor & was chosen because of the tight-knit “band/bond” of Edward’s knightly cause supporters.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

𝑅𝑒𝒸𝑒𝒾𝓋𝒾𝓃𝑔 𝓉𝒽𝑒 𝐻𝑜𝓃𝑜𝓇

𝒯𝒽𝑒 𝒞𝒽𝑜𝑜𝓈𝒾𝓃𝑔 𝒫𝓇𝑜𝒸𝑒𝓈𝓈

Each member would nominate 9 candidates who have the rank of either Earl or higher (3 members), have the rank of Baron or higher (3 members), & have the rank of Knight or higher (3 members). The Sovereign then personally chooses as many nominees that as necessary to fill any vacant spots in the current Order of the Garter. But with the nominees comes a decision. The Sovereign (He or She), are not obliged to choose the nominees who received the most nomination counts. This practice ended in 1860. Today, before receiving the The Most Noble Order of the Garter, an appointment is made with the Sovereign (A.K.A: The Queen) at sole discretion.

𝒯𝒽𝑒 𝒞𝒽𝑜𝑜𝓈𝒾𝓃𝑔 𝒫𝓇𝑜𝒸𝑒𝓈𝓈 𝐻𝒾𝓈𝓉𝑜𝓇𝓎

(The Right Honorable Clement Attlee 1st Earl of Attlee)

(The Right Honorable Sir Winston Churchill)

During the 18th century, the Sovereign would choose those to serve on The Most Noble Order of the Garter, by the advice of the current Government. In 1946, membership of the United Kingdom’s highest ranking orders of Chivalry (The Most Illustrious Order of Saint Patrick, The Most Noble Order of the Garter, & Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle) became a personal choice of the Sovereign once again, with the joint agreement of Prime Minister The Right Honorable Clement Attlee 1st Earl of Attlee & The Leader of the Opposition The Right Honorable Sir Winston Churchill.

The person being appointed to the Order is announced on April 23rd which is known as St. George’s Day. When created, it was said that the original status required that each member of the Order already be a knight (now referred to as a Knight Bachelor). The initial members were knighted the year, the order was created.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

𝒪𝓇𝒾𝑔𝒾𝓃𝒶𝓁 𝑀𝑒𝓂𝒷𝑒𝓇𝓈

(Each Members photo will be below their name)

Male members of The Most Noble Order of the Garter are titled “Knights Companion.”

♕ Sir Sanchet D’Abrichecourt

♕ Edward, The Black Prince, Prince of Wales

♕ Henry of Grosmont, 1st Duke of Lancaster

♕ Thomas de Beauchamp, 11th Earl of Warwick

♕ Jean III de Grailly, Capital de Buch

♕ Ralph Stafford, 1st Earl of Stafford

♕ William de Montagu, 2nd Earl of Salisbury

♕ Sir Roger de Mortimer, 2nd Earl of March

♕ John de Lisle, 2nd Baron Lisle of Rougemony

♕ Bartholomew Burghersh, 2nd Baron Burghersh

♕ Admiral of the Fleet Sir John Paveley de Beauchamp, 1st Baron Beauchamp de Warwick

♕ John (V) de Mohun, 2nd Baron Mohun

♕ Sir Hugh Courtenay

♕ Thomas Holland, 1st Earl of Kent

♕ John de Grey, 2nd Baron Grey de Rotherfield

♕ Sir Richard Fitz-Simon

♕ Sir Miles Stapleton of Bedale

♕ Sir Thomas Wale

♕ Sir Hugh Wrottesley

♕ Sir Neil Loring

♕ Sir John Chandos, Viscount of Saint-Sauveur

♕ Sir James Audley

♕ Sir Otho Holand

♕ Sir Henry Eam

♕ Sir Sanchet D'Abrichecourt

♕ Sir Walter Paveley

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

𝒯𝓎𝓅𝑒𝓈 𝑜𝒻 𝑀𝑒𝓂𝒷𝑒𝓇𝓈

𝐿𝒶𝒹𝒾𝑒𝓈 𝒞𝑜𝓂𝓅𝒶𝓃𝒾𝑜𝓃 𝑜𝒻 𝓉𝒽𝑒 𝒢𝒶𝓇𝓉𝑒𝓇

(Each members photo will be under their names)

(King Henry VII of England)

(Lady Margaret Beaufort)

(Her Majesty Queen Alexandra)

(His Majesty King Edward VII)

(His Majesty King George V)

(Her Majesty Queen Mary)

(His Majesty King George VI)

(Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother)

After The Most Noble Order of the Garter was founded, like men, women were appointed Ladies of the Garter but were not companions. Ladies of the Garter included: Lady Margaret Beaufort (Mother to King Henry VII of England), Her Majesty Queen Alexandra (Wife of His Majesty King Edward VII: She was named Lady of the Garter by her husband), Her Majesty Queen Mary (Wife to His Majesty King George V: She was named Lady of the Garter by her husband), & Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother (Wife to His Majesty King George VI: She was named Lady of the Garter by her husband). This practice though, was put to a stop by King Henry VII of England in 1488. Although beginning in the 20th century, women began to be re-associated with the The Most Noble Order of the Garter, but were again not made companions. In 1987, under the statue of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, it became possible to install “Ladies Companion of the Garter.”

𝒪𝒻𝒻𝒾𝒸𝑒𝓇𝓈

(Each members photo will be under their names)

(Timothy John Dakin)

(James Hamilton, The 5th Duke of Abercorn)

(Thomas Woodcock)

(Sarah Clarke)

(The Right Reverend Bishop David Conner, The Dean of Windsor)

(Patric Laurence Dickinson)

The Most Noble Order of the Garter has 6 different types of Officers:

1. The Prelate: This position will always belong to The Bishop of Winchester. Currently - Timothy John Dakin (Since 2012).

2. The Chancellor: Responsible for the Seal & Its Use: Currently - James Hamilton The 5th Duke of Abercorn (Since 2012)

3. The Register: Currently - The Right Reverend Bishop David Conner, The Dean of Windsor

4. The Garter Principal King of Arms: The Officer has jurisdiction over England, Wales, & Northern Ireland (With exception of Canada). Responds to the Earl Marshal for the running of the College & is the Principal Advisor to the Sovereign of the United Kingdom. This officer announces the New Monarch, after the current monarch has died. Currently - Thomas Woodcock (Since April 2010).

5. The Gentleman/Lady Usher of the Black Rod: Responsible for controlling access to and maintaining order within the House of Lords & its precincts, as well as for ceremonial events within those precincts. The officer is also the Usher & Doorkeeper at Order of the Garter Meetings & the personal attendant of the Sovereign. This officer has many other positions & duties as well. Currently - Sarah Clarke (Since February 13th, 2018)

6. The Secretary: Currently - Patric Laurence Dickinson (Since September 1st, 2010)

𝒮𝓊𝓅𝑒𝓇𝓃𝓊𝓂𝑒𝓇𝒶𝓇𝓎 𝑀𝑒𝓂𝒷𝑒𝓇𝓈

(Each members photo will be under their names)

Along with the Founder, Ladies Companion of the Garter, & The Original Members of the The Most Noble Order of the Garter, there is another group of members who receive this honor. These members are called Supernumerary Members & they are the members who do not count towards the limit of the 24 Living Family Members/Companions but are in association of the Order. These members can also be referred to Royal Knights & Ladies of the Garter.

(His Majesty King George I of Great Britain)

(His Majesty King George II of Great Britain)

(His Majesty King George III of The United Kingdom)

(His Imperial Majesty Emperor Alexander I of Russia)

These titles were created by His Majesty King George III of The United Kingdom in 1786 but didn’t create the statute of Supernumerary Members until 1805. He created the title of Supernumerary Members, so that his sons didn’t count toward the 24 companion limit. King George created the statute of members, so that any descendant of His Majesty King George II of Great Britain, could not be installed in The Most Noble Order of the Garter as such a member. 8 years later in 1813, during the reign of His Imperial Majesty Emperor Alexander I of Russia, a membership of being a supernumerary member was extended to foreign monarchs. These members were known as Stranger Knights & Ladies of the Garter. The Statute of Supernumerary Members was put back into play in 1831 & extended to all descendants of His Majesty King George I of Great Britain. In 1954, each installation into The Most Noble Order of the Garter, required an enactment of the statute. The statute authorizes the regular admission of Stranger Knights & Ladies of the Garter without further special enactments.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

𝒞𝓊𝓇𝓇𝑒𝓃𝓉 𝑀𝑒𝓂𝒷𝑒𝓇𝓈 𝑜𝒻 𝓉𝒽𝑒 𝐻𝑜𝓃𝑜𝓇

*Fact: The Most Noble Order of the Garter is only allowed to The Sovereign/Monarch, The Heir to the Throne, 24 Living Family Members/Companions, & Various Supernumerary (not belonging to a regular staff but engaged for work) Members. The Monarch alone can also grant membership.*

(Each Member will have their photo below their name)

♕ Her Majesty The Queen: Sovereign of The Most Noble Order of the Garter

♕ His Royal Highness Prince Philip

♕ His Royal Highness Prince Charles: Royal Knight Companion of The Most Noble Order of the Garter

♕ His Royal Highness Prince William

♕ His Royal Highness Prince Andrew

♕ His Royal Highness Prince Edward

♕ Her Royal Highness Anne The Princess Royal

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

𝒟𝑒𝑔𝓇𝒶𝒹𝒶𝓉𝒾𝑜𝓃 𝑜𝒻 𝒶 𝑀𝑒𝓂𝒷𝑒𝓇

The Degradation of a Member of the The Most Noble Order of the Garter is a big issue, but can be done by the current Sovereign. This began in the late 15th century.

𝒯𝒽𝑒 𝒟𝑒𝑔𝓇𝒶𝒹𝒶𝓉𝒾𝑜𝓃 𝒫𝓇𝑜𝒸𝑒𝓈𝓈

During the 15th century, The Degradation of a Member of the The Most Noble Order of the Garter was a formal ceremony. The Garter King of Arms is accompanied by the rest of the members at St. George’s Chapel. The Garter of Arms reads aloud the reason for degradation as a member climbs up a ladder to remove the former knights banner, crest, helm, & sword into the choir. The other members then lead the degraded knight down the length of the chapel, out the doors, & into the castle ditch.

𝐿𝒾𝓈𝓉 𝑜𝒻 𝒟𝑒𝑔𝓇𝒶𝒹𝑒𝒹 𝑀𝑒𝓂𝒷𝑒𝓇𝓈

During World War 1, a total of 8 knights were degraded from their positions: 2 Royal Knights & 6 Stranger Knights. These knights were rulers, monarchs, or princes of enemy nations in 1915.

(Each Member will have their photo below their name)

♕ 1915: His Highness The Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha: Broke off relations with his family in the Belgian & British Courts to support the German Empire. He was stripped of his honor by His Majesty King George V.

♕ 1915: Crown Prince Ernest Augustus of Hanover, 3rd Duke of Cumberland and Teviotdale: World War 1 created conflict between the British Royal Family & the Hanoverian Cousins. He was stripped of his honor by His Majesty King George V.

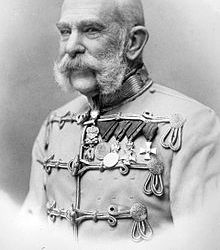

♕ 1915: His Imperial and Royal Apostolic Majesty Franz Joseph I The Emperor of Austria & Apostolic King of Hungary: Besides being stripped of his position in The Most Noble Order of the Garter, he was also stripped of his Royal Victorian Chain Award.

♕ 1915: His Royal Highness Prince Henry of Prussia: Besides being stripped from his position in The Most Noble Order of the Garter, he was also stripped of his position from The Most Honourable Order of the Bath & stripped of his Royal Victorian Chain Award.