#anne of bohemia is my forever girl

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

🌹!

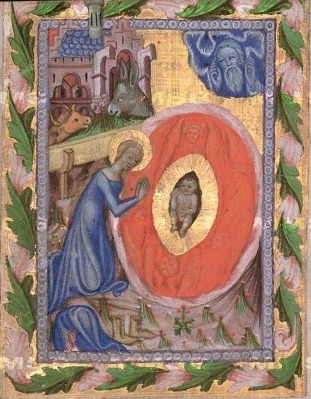

Anne turns the leaf and is faced with an image of the Blessed Virgin kneeling before the Christ child, emerging from a golden nimbus surrounded by red, and then pink—it's clearly evocative of precisely how he came into the world, only drawn by a celibate monk who would never know the pain of childbirth. She touches the tiny image of the baby and a noise escapes her throat that's caught partway between a giggle and a sob.

(from my bonus fic for the bad pregnancy timing au. I know you know but for those who don't: the manuscript image described here is real and here it is)

#fic babble#the bad pregnancy timing au#anne of bohemia is my forever girl#send a rose get some prose

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Adding tags from @skeleton-richard because they pass peer review:

Queenship only tends to become visible as a political position when queens come into conflict either with other factions at court or with their own husbands, but it's an inherently political job. As Kristen Geaman has argued, queens were expected to be partners in ruling as well as just being wives and mothers of heirs, and the fact that Anne has the reputation she does despite the clear evidence of her involvement in court life (both as an intercessor and as a cultural figure; she was coming from the glittering center of Europe to the edge of nowhere) suggests that political activity by queens was unremarkable in and of itself.

(She also didn't introduce the sidesaddle or the peaked headgear--the sidesaddle was in use in England at least since the twelfth century, since Gerald of Wales remarks on Irish women riding astride like it's weird, and the tall headdresses didn't really take off until the fifteenth century)

Anne of Bohemia

Anne of Bohemia was born to Charles IV, the Holy Roman Emperor, and his fourth wife, Elizabeth of Pomerania. She was the first daughter of Elizabeth, however she had three older half-sisters from her father's previous marriages. Anne had four younger brothers, two of them did not live long, and a younger sister. She also had four half-brothers, though only Wenceslaus (the future Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia) from Charles' third marriage survived past infancy, and three half-sisters. She had been born on the May 11, 1366 in Prague, in the Kingdom of Bohemia. She was mainly brought up at Prague Castle, and was fluent in several languages.

When Anne was eleven or twelve, her father, Charles, died and her brother Wenceslaus became King Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia. It was her brother who negotiated the marriage between Anne and King Richard II of England. Anne brought no dowry to England but Richard gave 20,000 florins (about £4,000,000 in today's value) in payment to Wenceslaus IV. She arrived in England in December 1381 after having been delayed by storms, and her ships were smashed to pieces as soon as she disembarked.

Anne and Richard were married in Westminster Abbey on January 20, 1382, and her coronation followed on January 22. It is said that their marriage, though arranged and at the young ages of fifteen, the two were in love and devoted to one another.

Anne ordered the Gospels in English to help her learn the language. She was credited with introducing the high-peaked horn headdress and the side-saddle to England. It is said she had little interest in politics.

Anne fell ill at Sheen Manor and died of the plague on June 7, 1394. Richard was so grief-stricken that he demolished Sheen Manor. She was only 28 years old. In the twelve years of her marriage to Richard, their union remained childness. She was known as "Good Queen Anne". She is buried in Westminster Abbey beside her husband.

#anne of bohemia is my forever girl#i wholeheartedly recommend geaman's bio of anne btw#full disclosure she is a friend of mine and i am in the acknowledgments#but it's genuinely really good#and you learn a lot about medieval queenship and what it entailed#she's a pretty good baseline for late medieval queenship because she wasn't *especially* controversial most of the time#although richard was#and of course there was always some controversy with immigrant queens#because xenophobia

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

fic writer self-recs

@titleleaf tagged me in this and I'm not gonna miss a chance for self-promotion, so here you go.

Fic authors self rec! When you get this, reply with your favourite five fics that you've written, then pass on to at least five other writers.

The Kindest Use a Knife (2014, Richard II, Richard/Aumerle, E, 11k words)

This is, to date, still my most popular fic and I'm still proud of it even though I'm a better writer than I was ten years ago (how was this ten years ago? What the fuck, passage of time). It's based specifically on the RSC production with David Tennant and was born out of a general sense of confusion over how the Stabby Aumerle ending seemed to work okay despite it making no sense in the context of the production and the ways the characters were played. I figured Stabby Aumerle in this production would only really make sense if Aumerle were under the impression it was the most loving option under the circumstances, and this was the result. Also, this fic made me realize I love writing the Yorks (the Duchess in particular just kind of charged into this fic). Fun trivia: my depiction of Exton owes a lot to Arthur Darvill's Mephistopheles (because I did love Doctor Faustus even before Hot Faust Summer).

Jesu dulcis memoria (2014, 14th-c RPF, Richard II + family, G, 1k words)

This was a Yuletide treat--one of those instances where someone's request lines up with something you'd been thinking of writing for ages anyway and the prompt makes you get off your butt and do it. It's centered on the creation of the Wilton Diptych from the viewpoint of the painter (who is fictional, since we don't really know much about who actually painted it) and focuses on the idea that the painting is not only a statement about kingship but also a memorial to Richard's (many) dead loved ones. Also there's one simile in there that everyone seems to love and so now I think about it every time I encounter gold leaf (which is a lot. I'm a manuscript librarian, although I wasn't when I wrote this).

Andělíčku rozkochaný (2019, 14th-c RPF, Richard II/Anne of Bohemia, E, 9k words)

Anne of Bohemia is, as you all know, my forever girl, and I'm still proud of this character study of her and her marriage to Richard and their approach to their infertility. I wrote a lot of stuff on this basic theme around the time I was writing this fic; maybe it was because turning 40 was getting to me on a subconscious level. The first scene of the fic is one of those things that came to me pretty much fully formed, while the last scene is another one of those things I'd had in my head for a while and finally had a reason to write down. (This is, therefore, another fic that has part of its genesis in a shiny historical artifact.)

not half so fair as thou (2023, Doctor Faustus, Faustus/Mephistopheles, E, 6k words)

We have arrived at Hot Faust Summer! The premise of this one came out of my pondering a line not from Marlowe's play but from Berlioz's La Damnation de Faust, which I was in last May and have not yet shut up about, but long story short, it set me thinking about productions where Faust(us) and his shadow-self Mephistopheles look similar (not unheard-of in Marlowe productions--the 2011 Globe one low-key did it and the 2016 RSC high-key did it--though I can't think of any operatic versions off the top of my head) and eventually I arrived at the premise of this fic. Which was a complete party to write. It was perhaps a little unsettling to realize that Faustus POV came to me extremely naturally but hey. That's academics for you.

none but thou shall be my paramour (2024, Doctor Faustus, Faustus/Mephistopheles, Faustus/Helen of Troy, M, 7.5k words)

It's the Codependent Faustopheles Manifesto! With boring academic dinner parties and sexy contract renewal! This is my most recent work (although it took me kind of forever to write; the tumblr post in which I proclaim my intentions to write it is here) and I'm really proud of it. It's weird, kind of gross, and has some massive tonal shifts in it, but I think it came off all the same. Plus I got to put some of my elaborate headcanons in there and I think I did a really good job with the "sex scene that is not actually sex but is definitely still a sex scene" trope.

Anyway, yeah! Go read my fic. I'm going to tag @skeleton-richard, @oldshrewsburyian, @themalhambird, @misskriemhilds, @heartofstanding, and anyone else who feels like doing this.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

I feel like I need to share this with all of you

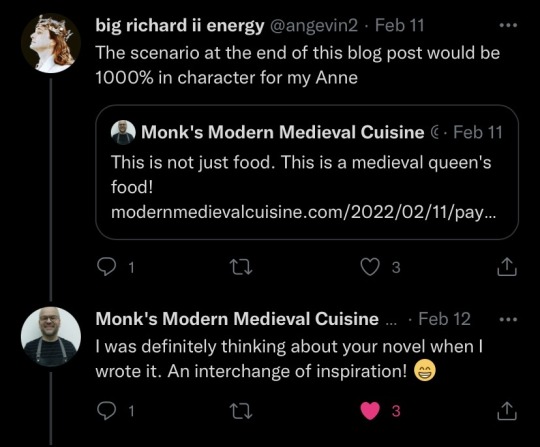

This is from a passage on Chaucer’s Legend of Good Women from Marion Turner’s biography of Geoffrey Chaucer (she’s talking about the context of the poem within Richard’s court, which is full of young people, men criticized as “knights of Venus rather than Bellona,” and a lot more women than was usual at medieval royal courts). I tried to track down the Nicola McDonald article cited, but it’s in an edited collection of articles rather than a journal and Google Books only showed a few pages of it, so I was unable to find the full context for this quote and now it’s going to haunt me forever.

From what I could piece together from Turner’s quotation and from the first couple of pages of McDonald’s article, she seems to be arguing that LGW participated in a genre of courtly pastime that included a lot of question-and-answer games about love and sex (I’ve actually taken advantage of that same trope in the novelthing, where I used it to set up a threesome). Apparently some manuscripts of LGW include the poem with texts dealing with this sort of game and other poems that resonate with the pastimes and interests of horny young courtiers, including courtly ladies.

The visible pages from McDonald that Google Books did include contain the riddle alluded to above, though. This is it:

It was probably funnier in the 1380s.

Before I double-checked the original French I thought there might have been some wordplay going on, maybe there’s a word for penis in Middle French that sounds like “piglet,” but it actually works better in English in that respect! But I think the power of the joke comes from the context: the ability of female speakers/listeners to signal their familiarity with penises and how they work would surely have given more of a frisson in the fourteenth century than it does today. A lot of scholars who have written about LGW fret about its tone: is it a serious effort to please a queenly patron who loved stories of pious women, abandoned because of the poet’s lack of interest (and her death), or a misogynist joke at her expense as Lydgate thought? What I can see of McDonald’s reading suggests an effort to cut the Gordian knot; we do know that Chaucer wrote some things explicitly meant to inspire courtly love debate (e.g., the Franklin’s Tale with its closing question) and I could see LGW fitting into that tradition. Obviously I’m not claiming for certain that this is where McDonald’s reading goes, but based on her premise, that’s where I’d take it. We know that Anne was both a pious lady and a sexually active married woman at the center of a court that enjoyed that sort of courtly love game.

I dunno what her experience with piglets was though.

#anne of bohemia#anne of bohemia is my forever girl#chaucer#richard ii#mildly nonworksafe text#oh bother

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

sunday snippet

So I’ve been working on Richard’s confrontation with the Lords Appellant in the Tower after Christmas of 1387, and one thing that’s surprised me a lot is how Richard’s been handling it. I think the narrative that Richard did essentially cease to rule for a few days after the meeting is basically accurate—obviously he wasn’t formally deposed because that requires more actions than the Appellants were able to take, and in my depiction of the meeting it ends on a note of “we’re gonna put you under house arrest while we decide what we’re going to do, but don’t be surprised when we overthrow you.” But the surprising part is that, while I expected Richard to have a breakdown once he got out of the meeting, he’s actually gone into strategy mode. I’ve been setting up the faultlines within the appellant coalition, and Richard is very aware of them. The meeting with Bolingbroke and Mowbray he mentions in this scene actually did happen and is attested by Walsingham and Knighton (although I don’t think either one has both men present, but hey. Dramatic license). So that’s gonna be fun and awkward but it’s gonna work.

Anyway, having Richard put up more of a fight in 1387 allows for a nice contrast with his actual deposition in 1399: I think he feels, at this point, that he has more to fight for. Anne is still alive, after all, and is an important part of his strategy here (which is why the appellants bar her from their meeting with Richard). Plus, and this is an extremely important point, the Merciless Parliament hasn’t happened yet and that’s where the trauma REALLY kicks in.

--

Anne is sitting by the fire, when Richard arrives with the guards beside him, a half-embroidered strip of linen in her lap, which she pokes at absently with her needle as she stares into the flames; she has even uncovered her hair, but when she hears the door open, she starts, dropping her needle and scrambling to pin her veil back on before the guards see her. A look of relief passes across her features when she sees Richard, followed by a look of concern—and then, as soon as the door is closed behind him and the guards are out of sight, she leaps to her feet and runs to him, throwing her arms around him, and Richard wraps his arms around her and presses her close.

After a long moment, she draws back far enough to clasp his face with both hands. “Are you all right?” she breathes.

“I don’t know,” Richard admits, and shakes his head. “They let me stay here with you, at least.”

“What happened?” Anne says. “Did you get them to see reason? They are not going to depose you, are they? They cannot, surely—”

“I don’t know, Anne,” Richard says. “Thomas and Arundel, at least, are utterly merciless. I believe Thomas wants to make himself king.”

“Pane Bože,” Anne moans, pressing her hands to her mouth. “He cannot—if he does not fear his king, surely—” She shakes her head, in turn. “If we could only get a message to John of Gaunt in time,” she says. “I know you do not trust him, but if they waited until he was away…”

“Right now, I would be willing to cast myself on his mercies,” Richard says, “rather than Thomas’s. Or, God forbid, Arundel’s. It would never get to Spain in time, though.”

“Do you think they would see me?” Anne says. “Even if they would not let me stay by your side, they might hear me out—you could not plead for mercy, as a king. But as a queen—as a woman—it is what I was made for. If I could speak to Thomas—perhaps he would listen? I know being around you makes him furious, but if I spoke to him alone, he might be calmer.”

“I don’t know,” Richard says. “He does seem to like you well enough. Remember what I told you the first time we met? He has a soft spot for pretty girls.”

For a moment, Anne beams; then, remembering the gravity of their situation, she is somber again. “I will write to him and ask for a meeting,” she says. “Right away.” She turns toward the little table in the room but stops when Richard lays a hand on her shoulder.

“You may be able to do better than that,” Richard says. With his hand on her back, he walks her back to the settle to sit by the fire. It is, after all, a cold evening. “Do you think you could convince Henry Bolingbroke and Thomas Mowbray to listen to you?”

Anne smiles again. “I think they would be easier to persuade than Thomas,” she says. “But do you think they would be able to convince Thomas of anything? Or Arundel?”

“I’m not sure,” Richard admits. “But they’re the ones having supper with us tonight, so right now they’re our best chance.”

“They are having supper with us?” Anne blinks and immediately begins adjusting her veil again.

“Not for a few hours,” Richard says. “Before compline. You’ll have plenty of time to get ready.”

“All right,” Anne says, running her hands over her head anyway to smooth the wrinkles in her veil, and not having much success. “How did you get them to agree to meet with us? I am amazed that Thomas and Arundel allowed it!”

“To be honest,” Richard says, “I am too. But I think that’s why the two of them decided to come, and I think that’s our best hope of getting out of this.”

Anne nods, but her eyes are wide and her expression is confused. “What do you mean?”

“I said before that I think Thomas wants to make himself king,” Richard says. “Despite the fact that the Mortimers, Henry, York and his sons, and, worst of all, John of Gaunt, are all ahead of him in the line of succession. He kept hinting at it throughout the meeting. And Henry definitely noticed. He may not care what happens to us, but I think he’ll be damned before he sees Thomas of Woodstock sitting on the throne. And I don’t think he’ll seize the throne for himself, no matter how badly he wants it. Not while his father lives.”

#sunday snippet#the novelthing#richard ii#anne of bohemia is my forever girl#otp: my derlyng is a bundel of myrre to me#i'm really surprised at richard's ability to pull himself together here#but not in a bad way#right now he's just trying to get through this with his life and his crown#and i think seeing the five of them be all smug has really lit a fire under him#unfortunately the next part is 'saving his friends' and that's gonna crush him#btw after this anne has a little speech about imperial elections#but this is long enough so i left it out here

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

I mean Michael Hicks kinda needs to stfu about women just generally (he's also Very Weird about Anne Neville) so I imagine he'd come down pretty hard on her too!

As someone whose interest in the Middle Ages is set in the pre-WOTR eras, I occasionally read scholarship on it and sit there blinking because like. wow. wow. this is what being lost in the sauce is like. Historians are really so attached to their ideas of what people are like they've lost all sense of context

Like, I read Michael Hicks going on about how Elizabeth Woodville pursuing Sir Thomas Cook for queen's gold was evidence of harassment and an attempt to punish him twice even though Elizabeth's pursuit of queen's gold was hardly unusual. It also makes me wonder what Hicks would say about Anne of Bohemia pursuing William Courtenay, Archbishop of Canterbury for queen's gold to the point of having the sheriff of Kent distraining him (seizing his goods) until Courtenay complained to the king (and this is apparently despite the parliament declaring the month before Courtenay's complaint that queen's gold did not apply to payments made to enter archbishoprics).

I mean, the issue is reputation - Anne of Bohemia is "good queen Anne", typically depicted as passive and meek, while Elizabeth Woodville's reputation typically runs to the gold-digging, ambitious femme fatale and bad queen.

#this is honestly one of my favorite anne of bohemia facts tbh#when this happened she was 16 and had only been queen for like a year#of course she is not going to let anyone walk all over her#but yeah going after queen's gold was common because nobody wanted to pay it#anne of bohemia is my forever girl

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

“…Now, if people are taught anything at all about medieval history it often is English medieval history. People with absolutely no other frame of reference can often tell you when the Norman Conquest of England took place, or the date of the signing of Magna Carta even if they don’t know exactly why these things are important. (TBH Magna Carta isn’t important unless you were a very rich dude at the time, sooooo.) If you ask people to name a medieval book they’ll probably say Beowulf even if they’ve never read it.

Here’s the thing though – England was a total backwater in terms of the way medieval people thought and was not particularly important at the time. How much of a backwater? Well, when Anne of Bohemia, daughter of my man Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV (RIP, mate. Mourn ya til I join ya.) married King Richard II of England in the fourteenth century there was uproar in Prague. How could a Bohemian imperial princess be sent to London? How would she survive in the hinterlands? The answer was she was sent along with an entire cadre of Bohemian ladies in waiting to give her people with whom she could have a sophisticated conversation.

This ended up completely changing fashion in England. Anne is the girl who introduced those sweet horned headdresses you think of when you think of medieval ladies, riding side-saddle, and the word “coach” to England, (from the Hungairan Kocs, where the cart she arrived at court the first time came from). Sweetening her transition to English life was the fact that she didn’t have to pay a dowry to get married. Instead, the English were allowed to trade freely with Bohemia and the Holy Roman Empire and allowed to be around a Czech lady. That was reward enough as far as the Empire was concerned. That’s how much England was not a thing. (The English took this insult very badly, and hated Anne at first, but since she was a G they got over it. Don’t worry.)

If England was unimportant why do we know about English medieval history and nothing else? Same reason you’re reading this blog in English right now, homes. I’m not sure if you know this, but in the modern period, the English got super super good at going around the world an enslaving anyone they met. When you’re busy not thinking about German imperial atrocities in the nineteenth century it’s because you’re busy thinking about British imperial atrocities, you feel me? So we all speak English now and if we harken back to historical things it gives us a grandiose idea of English history.

Say, then, you are trying to establish a curriculum for schools that bigs up English history, as is our want. Ask yourself – are you gonna want to dwell on an era where England was so unimportant that Czechs were flexing on it? Answer: no. You gonna gloss right over that and skip to the early modern era and the Tudors who I am absolutely sure you know all the fuck about. The second colonial-imperialist reason for not learning about medieval history is that medieval history doesn’t exactly aggrandise the colonial-imperialist system.

Yes, there are empires in medieval Europe. In addition to the Holy Roman Empire there’s the Eastern Roman Empire, aka the Byzantine Empire, whose downfall is often pointed to as one of several possible bookends to the medieval period. You also have opportunists like the Venetians who set up colonies around the Adriatic and Mediterranean, or the Normans who defo jump in boats and take over, well, anything they could get their hands on.

Notably, when these dudes got where they were going, they didn’t end up enslaving a bunch of people, committing genocide, and then funnelling all resources back to a theoretical homeland. The Normans settled down where they were eventually creating distinctive court cultures, and the Venetian colonies enjoyed a seriously high level of trade and quality of life without major disruption to local customs. Force was certainly used to take over at the outset, but it wasn’t something that resulted in the complete subjugation and deaths of millions halfway around the world from where the aggressors started.

No, the European middle ages are a lot more about local areas muddling along with smaller systems of rule. That’s why you have distinctive areas like say, Burgundy or Sicily calling their own shots and developing their own styles and fashions. Hell, even within imperial systems like the Holy Roman Empire Bavarians or Bohemians saw themselves as very much distinct peoples within an imperial system, not necessarily imperial subjects first and foremost.

You know where you would go to find some history that justifies huge imperial systems that require constant conquest and an army of slaves to keep them afloat? Ancient Rome. Remember how you got taught how great Rome was? How it was a democracy? How they had wonderful technology and underfloor heating, and oh isn’t that temple beautiful? Yeah, that’s because you were being inculcated to think that the ends of imperial violence justifies mass enslavement and disenfranchisement.

In reality, Rome wasn’t some sort of grand free democracy. Only a tiny percentage of Romans could actually vote. Women of any station certainly could not, and even men who were lucky enough to be free weren’t necessarily Roman citizens. Freedom here is particularly important because by the 1 century BCE 35 – 40% of the population of the Italian peninsula were slaves. Woo yeah democracy. I love it. And that’s not even taking into account all those times when an Emperor would suspend voting altogether.

Those slaves were busy building all the grand buildings your high school history teacher was dry jacking it about, stuffing the dormice that the rich people were reclining to eat, and basically keeping the joint running. Those slaves also necessitated the ridiculously huge army that Rome kept going because you had to get slaves from somewhere after all, so warfare had to be continuous. How uplifting.

Eagle-eyed readers will notice that this Roman nonsense is pretty much exactly what was going on during the modern colonial imperial age. You can say whatever the fuck you want about how free and revolutionary America was, for example. That doesn’t change the fact that only a handful of white property owning men could vote, and that the entire project required the mass enslavement of Africans and the genocide of Native Americans. That’s why you’ve been taught Rome is great. It helps you sleep well at night on stolen land because, really, haven’t all great societies done this? I mean without a forever war against anyone you can find, how will you keep a society going?

Our imperialist ideas about history lead to some weird historical takes. People love to tell you that no one bathed in the medieval period when medieval people had pretty much exactly the same sort of bathing culture as Romans. People laugh at medieval people believing in medical humoral theory despite the fact that Romans believed exactly the same thing and get a total pass on that front. The Roman ban on dissection is often taught as a medieval ban, shifting Roman superstition onto the shoulders of medieval people.

On-going Roman warfare is reported in glowing terms with emphasis on the “brilliance” of Roman military technique, while inter-kingdom warfare in the medieval period is portrayed as barbaric and ignorant. The Roman people who were encouraged to worship emperors as literal gods are used as an example of theoretical religion-free logical thinking, while medieval Christians are cast as ignorant for believing in God even when they are studiously working on the same philosophical queries as their predecessors. None of this makes any fucking sense.

But here’s the thing – it doesn’t need to. In a colonial imperialist society we have positioned Rome as a guiding light no matter what it’s actual practices and that’s not a mistake. It’s a design that helps to justify our own society. Further, this mindset requires us to castigate the medieval period when rule was more localised and systems of slavery had taken a precipitous dive. If only there had been more slavery, you know? Things might have been so much better.

Historical narratives and who controls them are always in flux. That old adage “history is written by the winners” comes to mind here, but that’s not exactly true. What the winners do is decide which histories are promoted, taught, and broadcasted. You can write all the history you want and if no one reads it, then it doesn’t really matter. That’s the gap that medieval history has fallen into. Colonial imperialism hasn’t figured out how to weaponise it yet, so it’s ignored. You could write this off as a “so what”, of course. Sure, maybe teaching the Roman Empire as a goal is a negative, but is ignoring medieval history really that bad a thing? You will be unsurprised to learn that I definitely think it is a bad thing, yes.

Ignorance about the medieval period is one of the things that is allowing the current swelling ranks of fascists to claim medieval Europe as some sort of “pure” white ideal. Spoiler: it was not. However, if you don’t know anything about medieval society how are you gonna argue with some chinless douche with a fake viking rune tattoo?History is always political. We use it to understand our world, but more than that we also use it to justify our world. Ignoring it helps us prop up our worst impulses, so let’s not.”

- Eleanor Janega, “On colonialism, imperialism, and ignoring medieval history.”

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

sunday snippet (sex and candy edition)

(There’s not really any sex except for two sentences at the end that aren’t explicit)

Having finished drafting Richard’s coronation scene, I thought I’d go back and work on Anne’s while I still have the Liber Regalis pdf out. Not that I used it at all for this particular scene.

On a somewhat related note: I’m a big fan of Christopher Monk’s “Modern Medieval Cuisine” blog, in which he’s cooking his way through the Forme of Cury in preparation for a book about it, and the most recent blog post (which is about candy, hence the connection) actually concludes with a bit of what I’m just gonna call NOVELTHING FANFIC.

--

It has been dark for hours when Anne is finally finished with the banqueting, and when Richard comes to her chamber she has been dressed for bed and is sitting on the bed with two of her ladies, the tall thin one with sandy hair and the shorter one with black curls (Richard is still working on learning their names). All three of them are giggling, eating comfits and sipping wine. Clearly, she’s feeling better than he did after his own coronation, a good sign certainly. The ladies both leap to their feet, curtsying, and Richard motions to them to straighten up. Anne says something to them in their language—they all giggle some more, and the two ladies curtsy to Anne as well before leaving the chamber.

“Agnes and Margaret have been teasing me since the day of our wedding,” Anne says, picking up the bowl of comfits and patting the mattress invitingly. “But they will get married eventually and then they will see.” She grins brightly as Richard sits beside her, and feeds him a piece of candied ginger; the sweet spicy heat makes his eyes water. “Their husbands will not be quite so wonderful as mine, though,” she adds, and draws him in to kiss his lips.

Richard laughs. “I’ll find someone nice to introduce them to.” He reaches into the bowl of comfits to snag a few more—a few cinnamon pastilles and a piece of candied orange peel. “I’m glad to see you still have an appetite,” he says. “After my own coronation I thought I’d never want to eat again. I couldn’t even look at the after-dinner sweets!”

“Poor Richard,” Anne says, reaching for a sugared almond. “Thank you for coming to see me today.” She wriggles closer to him, and he wraps an arm around her as she smiles up at him. “It was a little frightening—I know why you could not come properly, but I knew you were there and that made it much easier.”

“You looked radiant,” Richard says, giving her a tight squeeze and kissing her hair. They have been married for only two days, and already it feels perfectly natural, snuggling in bed with his new wife, relaxing and eating comfits and talking about their day, even when the day involves a once-in-a-lifetime event.

Anne leans into him, resting her head on his shoulder and putting the bowl down to drape an arm around his waist. “It was frightening,” she says, “but it was also exciting. I do not know how it is for boys, and of course it is different when you are the heir to the throne, but if you are one of several sisters, you are hardly ever the center of attention. Unless someone is asking for your hand, and that does not come with a feast most of the time, and if it does you spend it worrying about not being good enough, and whether you are going to marry someone you will actually like. But now that is all over with, and I have found a wonderful husband, and I am a queen.” She looks up at him with a grin, and adds, “I think I liked it.”

Richard grins back at her. “You deserve to be the center of attention,” he says. “You certainly have mine.” He picks up the comfit bowl and feeds her a piece of candied orange peel; she takes it delicately in her mouth and captures his fingertips between her lips for a moment. Richard can feel himself flush, but in a nice way.

“You are sweet,” Anne says. “Sweeter than anything in this bowl.” She reaches up to draw him into a kiss.

“Do you know what part of the coronation ceremony I especially liked?” Richard murmurs. Anne shakes her head with an anticipatory smile. “I liked the part where he talked about the chastity of royal wedlock, or whatever it was.”

Anne giggles. “It is almost as holy as being a virgin,” she says. “My saintly ancestors will have no reason to be ashamed of me.” She rests her head on his shoulder again and cuddles close to him. “I think lying together in holy matrimony must be like a sacrament itself,” she says. “When I am close to you, I know I am close to God as well.” She stifles a yawn, without much success. “I would like to sleep a little, first, though. Before we make love. If that is all right with you?”

Richard smiles and presses a kiss to her forehead. He can smell the chrism in her hair. “Anne,” he says, “when I was crowned, Sir Simon had to carry me out of the church, and then they delayed the banquet so I could sleep. And then I threw up at the end of the night. I’m amazed by your stamina as it is.”

Anne giggles sleepily. “You were just a little boy, though,” she says. “And a king. I am sure the ceremonies are much longer for kings than they are for queens.”

“Oh, probably,” Richard says. “But if you need rest, you need rest.” He kisses Anne’s forehead again, collects the comfit bowl and puts it on the table, and then climbs back into bed to wrap his arms around her.

Later that night, between first and second sleep, Anne kisses him awake, and then climbs on top of him. They do it again in the morning.

#the novelthing#sunday snippet#richard ii#anne of bohemia is my forever girl#otp: my derlyng is a bundel of myrre to me#note also the obvious foreshadowing early on#anyway they are cute and i love them#...that was already in my tags OH WELL

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

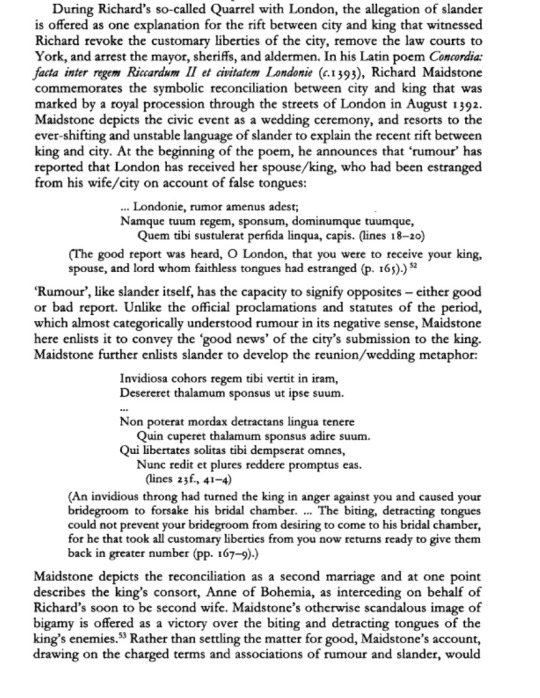

This isn’t a terribly uncommon reading of Maidstone’s Concordia—Sylvia Federico makes a similar one where she suggests that Maidstone has pretty much accidentally written Richard as a bigamist (or patron of sex workers) and Anne as a madam, so actually he ended up with a subversive poem—and I always think it’s weird. Marriage between the king and the realm is a longstanding trope, after all; I don’t think it would read as scandalous to a contemporary reader unless they were really determined. Anne’s intercession as described in the poem reads less to me as procuring an entirely separate marriage for her husband and more as essentially identifying herself with the city, taking its offenses onto herself if you will. Her intercession allows for Richard’s relationship with his subjects to be realigned with his happy and loving marriage; she’s not stepping aside so he can cheat on her with the city of London or something.

(cf. also Sebastian Sobecki’s reading of Apollonius of Tyre, which has one of the cutest endings of a scholarly article ever)

I think all of this falls into the “Anne is mostly a literary construct rather than a real person and any discussion of her is really about the male poet’s agenda” category, but also: it’s weird.

#or am i weird?#i realize i have an atypically positive reading of the concordia as far as academic takes on it go#richard ii#anne of bohemia#anne of bohemia is my forever girl#anne is not in fact a literary construct jsyk#she was a real person we just don't know too much about because of the distance of centuries#and one really hostile chronicler

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

A girl’s natural habitat is in a bed with many blankets and pillows and it’s inhumane to remove her from her natural habitat

95K notes

·

View notes

Text

wip wednesday (bohemian rhapsody edition)

I’m letting the Peasants’ Revolt section sit in the fridge for a bit to let the flavors meld, and also I felt like writing some Richard/Anne content, so here, have some. I think I already have more Czech cultural references than any other fictional depiction of Anne of Bohemia ever. The story she tells here is pretty accurate to the most famous version of the legend (as told by Alois Jirásek in 1894), because idk where to find the text of Cosmas of Prague’s Chronica Boemorum, which is more period-appropriate. Anyway, it’s framed here for maximum foreshadowing. You’ll know it when you see it.

--

Richard has not been to Nottingham in some time, but he has always enjoyed residing there: the magnificent deer park beside the castle, with its beautiful forests and orchards, plentiful deer, fishing ponds, falconry, and rabbit warren, is one of his favorite places. He’s been eager to visit with Anne, who is still learning the realm in their second year of marriage. Since the happy resolution of last summer’s tumultuous events, hunting and falconry have been a way for the two of them to spend time with Robert, and for Anne and Robert to grow closer to one another. Anne has shown a particular love for falconry—after all, she is, Richard had teased her, an imperial eagle. Last summer, the Duke and Duchess of York had given her the gift of a beautiful female merlin, which she had given the unusual (as far as he understood things) name of Libuše.

“She was my ancestor,” Anne had explained, when Richard asked her about it. “She was a queen, back in the pagan days, and she built the city of Prague. She was the youngest of three daughters, but her father chose her as his heir, because she was also the wisest, and she could see visions of the future. She was especially skilled at settling disputes in court. But her subjects grew angry. One man who had lost his court case stirred them up against her. He said that women cannot reason, that the people needed a strong man to rule them, and many other men agreed with him. They did not want to be ruled by a woman any longer. They insisted that she marry. But Libuše did not want these men to tell her what to do. It made her angry that they objected to her compassionate rule, and all because of her sex. So she insisted on choosing her own husband, and she had fallen in love with a plowman called Přemysl.”

“She married down!” Richard exclaimed. “Like the Emperor’s daughter who married the King of England, I suppose,” he teased her.

Anne giggled, then. ���She married for love,” she said. “But Libuše knew that one day her husband would become a stern ruler, who treated his people harshly. She had the gift of prophecy, remember. If that was what they wanted, she thought, they could have it! So she told them to saddle her horse, and let it wander until it found a man plowing his fields, wearing a broken sandal, and bring him to her, for she would marry only that man. Of course, she already knew where to find him, and her horse did too. But her council did not know that. They did as she told them, and her horse went straight to Přemysl. So they brought him back as Libuše had ordered, and they were married. And the house of Přemysl—my father’s house—endures to this day.”

Richard smiled. “Bohemian women have always been remarkable, I see,” he said. “What happened to the two of them?”

“Eventually, she died,” Anne said, “but she had been right. She and Přemysl had ruled well for many years. But after she died, he became the stern and harsh ruler she had prophesied.”

“It’s a sad story, then,” Richard said. “He must have loved her so much—perhaps he couldn’t rule well without her.” He’d smiled, and kissed Anne. “They were your ancestors, you say? I think you must take after her.” And Anne had giggled and kissed him back.

#the novelthing#anne of bohemia is my forever girl#wip wednesday#otp: my derlyng is a bundel of myrre to me#české věci#extremely subtle foreshadowing

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

fic: smale fowles maken melodye (1350 words, rated G)

This fic was inspired by this fantastic drawing by @sekihamsterdiestwice! I had one particular headcanon about Richard that I felt would make for a very amusing juxtaposition with the picture, and I decided: why not write about it?

--

"Where did you even get that thing?" Robert exclaims, wincing at the discordant sounds coming from the small gittern Richard is tunelessly strumming. He is lounging with Anne on a small cushioned bench in their small enclosed garden, beneath a trellis covered in roses, a crown of roses on his head and a single rose in Anne's hair—a lovely sight, if you could somehow contrive to disengage your ears. Perhaps Anne has just such a skill, as she is leaning on his shoulder, smiling blissfully and making no sign that she's bothered by her husband's cold-blooded torture of an innocent stringed instrument. Robert makes a note to himself to ask her to teach him. Of course, she's wearing her hair in thick braids coiled over her ears and held in place by a golden hairnet, so perhaps that mitigates the worst of the effects.

"Didn't you take music lessons as a boy?" Richard says, his fingers pausing mercifully on the strings.

"Of course I did!" Robert says. "Mine actually worked, though."

"Unlike your lessons in tact and courtly manners, I see." Richard grins and punctuates his remark with another sound that might, if you were generous, be called a chord. "Are you going to come and sit with us, or aren't you?"

"We all have our strengths and weaknesses," Robert says, flopping down on the soft grass at Richard's feet.

"I think it is sweet, anyway," Anne says. "Has he never serenaded you?"

"No, thank God," Robert says, scooting out of the way just in time to avoid Richard's foot.

"A grievous oversight, on my part," Richard says. "I'll have to remedy it immediately." He resumes his strumming, accompanying himself as he sings in a light, clear tenor:

"Gais et jolis, liés, chantant et joieus..."

It would be quite lovely, really, if it could adhere to a melody for more than a few notes, and unfortunately this particular melody is a winding thread that, in Richard's mouth, quickly tangles and loses track of itself, not helped by Richard's on-the-fly efforts to modify the lyrics for a male beloved. All three are giggling when Richard breaks off after a few lines. Robert leans over to rest his head in Richard's lap, and Richard drapes an arm over his shoulder.

"Well, you tried your best," Robert says.

"That is the important part," Anne adds, leaning in and kissing Richard on the cheek.

Richard strokes Robert's hair. "Nobody tell Henry Bolingbroke, though," he says, although his good mood remains unbroken—Robert can hear the smile in his voice. Anne and himself are the only people allowed to tease Richard this way, and they both know that Richard likes it when they do. It makes him feel like a normal person, being surrounded by people he loves, who love him—whom he trusts, enough even to let his carefully-guarded dignity slip. He takes Richard's hand and presses it to his lips.

Anne leans in and half-whispers, "Mary was telling me about how she sings with her husband," and Robert mouths oh, I see and nods his head. Henry is reputedly a talented musician, although Robert finds it a little hard to believe, given that he is visibly and wholeheartedly committed to his own image as a rugged warrior, rather than some artsy-fartsy courtier-poet type, and then wonders why Richard doesn't especially enjoy his company. If he's got a softer side his wife is allowed to see, Robert is honestly relieved on her behalf.

"Maybe if we tried something simpler," he says aloud, sitting up straight. He reaches out toward Richard. "Hand me the gittern, won't you?"

Richard does so, grinning. "Ah, so you're going to serenade me then? I approve."

"Even better," Robert says, plucking a simple ostinato on the gittern. "I think you know this one, Richard. Anne, I'm guessing you don't, so I'll sing it for you first. It's a round, so we'll sing it on top of each other, eventually." He waggles his eyebrows, and Richard and Anne both giggle, Anne's cheeks turning a fetching shade of pink. When they've settled down, he begins.

"Sumer is icumen in, Lhude sing cuccu! Groweth sed and bloweth med and springth the wode nu, Sing, cuccu!"

When he's finished, Richard and Anne applaud and beam at him, and he makes the closest simulation of a bow he can when sitting cross-legged on the ground. "Let's try it together now," he says. "I'll start, and when I point to you, start singing the melody, all right?"

"Wait, wait," Anne exclaims, throwing her hands up. "This song has many words, and they are all English words, and I will never remember them all."

Anne has only been in England for a few years, and Robert knows she has been working diligently on her English, with her husband's help and sometimes his own as well. Still, he can't imagine it's an easy language to pick up, especially when you already speak five others like she does. He's heard her speak her native language before and neither he nor Richard could make even a scrap of sense of it.

"We can go over them again," Robert says, strumming a chord on the gittern. "I'll sing each line and you two repeat after me."

He begins the song again, stopping after each line so Anne (and Richard) can sing it back to him; Richard's ability to carry a tune not much improved when it's a simpler tune, and Anne's clear, warm singing voice stumbling over the unfamiliar words. But it is an old song. Nobody speaks English this way anymore, anyway.

"Why are we singing about deer farts?" Anne exclaims, after Richard has explained a particularly vexatious line, and both Richard and Robert laugh.

"Why not sing about deer farts?" Robert says. "Especially in the presence of the White Hart?"

"Hey!" Richard shoves him with his foot, and Anne giggles. "It's a spring song! With lots of—seed. And things, you know, blowing." Robert snorts, and Anne giggles even more. "Like flowers!" Richard adds. "And cuckoos! Naughty little birds, they are."

At last they're ready to try it as a round: Robert plays the ostinato on the gittern and sings the melody as though he's clinging to it for dear life. Anne comes in second, handling the melody beautifully but replacing most of the words with nonsense syllables. Finally there's Richard, who knows the words but only bounces off the melody occasionally while his voice wanders around somewhere else entirely. Every few measures they break down in giggles.

It's strangely beautiful, nevertheless.

After a few repetitions the round finally limps to a close with Richard caroling "Sing cuccu, nu!" in a way that would probably terrify a real cuckoo. Neither Robert nor Anne, however, is a cuckoo, and the two of them applaud.

"Come sit up here with us!" Richard says, afterward, taking Robert's hand and pulling him up to join them on the bench, and Robert abandons the gittern to sit beside them. Richard wraps one arm around his waist and the other around Anne's before turning to kiss first Anne and then Robert on the lips, and then the three of them sit contentedly, leaning on one another, enjoying the quiet that's occasionally broken by actual (and much more melodious) birdsong.

"Why are English poems and songs so obsessed with cuckoos, anyway?" Anne asks, after a bit.

"I told you, they're naughty little birds!" Richard says. "Like in that poem Sir John Clanvowe wrote for you."

"It's because in English it sounds like 'cuckold,'" Robert says. "Men are constantly harping on the idea of their wives cheating on them, after all."

"Surely not Sir John, though," Anne says. "He doesn't even have a wife!"

Richard and Robert both grin. "And he's true to Sir William," Richard adds, "just as you both are to me."

Robert leans in to kiss Anne's hand, and then Richard's cheek. "We all live in harmony," he says, raising an eyebrow to grin back at Richard. "Well. Figuratively."

--

Notes

I usually translate Middle English lyric into modern English, but I thought this one was too hard (and way too famous). Just assume that everything else here is "really" in French. Including the French lyrics that I kept in French. Look, what do you want from me, consistency? This is sheer fluff and I wrote it in a day.

I am assuming anyone reading this fic knows "Sumer is icumen in." My favorite version of it is this one. The other song Richard attempts is Machaut's "Gais et jolis." I tried to work in a reference to Machaut's service to Anne's grandfather, John the Blind (King of Bohemia 1323–46, and the star of Machaut's poem Jugement du roy de Behaigne) but it got too clunky, since Machaut is never actually named in the text.

An amusing summary of the debate over the meaning of bucke verteth can be read here.

#fic#richard ii#anne of bohemia is my forever girl#the exceedingly queer robert de vere#ot3: 'tis two rogues i love#my fic is not as good as the picture that inspired it but that's okay

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

One result of the schism of 1378 is that the Roman pope, Urban VI, wanted to create alliances among important members of Team Rome and also keep the HRE off of Team Avignon (since Charles IV and his son and successor Wenceslaus IV had distinct Francophile leanings), and thus he encouraged Richard II to marry Wenceslaus' younger half-sister Anne of Bohemia, who did not come with a dowry but did come with a lot of cultural cachet and shiny things, so Richard was absolutely on board with this move even though he had to subsidize Anne's travel across Europe, which was an unpopular decision politically but a very good life choice for him (and Anne) since they fell in love and were very happy together.

Anne also brought with her a cultural background of vernacular piety -- her brother is the same Wenceslaus who commissioned the German-language Wenceslaus Bible, and there are at least two Czech-language devotional texts associated with her and her retinue -- so proto-reformists such as John Wyclif quickly seized upon her as an example of someone whose possession of non-Latin devotional materials did not make a heretic. This was true, as far as it went; there's no particular evidence that her religious practices were anything but orthodox (she is known to have been devoted to her namesake saint, for instance) and it wasn't uncommon for elites, who had confessors and chaplains to guide their reading, to own vernacular prayerbooks and even bibles. However, other Bohemians in England did jump onto the Wycliffite wagon and ultimately brought his ideas back home where they were a major influence on Jan Hus and through him other continental reformers.

As a result, early English histories of the Reformation such as John Foxe tend to present Anne as sort of a founding mother of reform, as support for the larger argument that there was a varyingly-underground True Church present in England all along. It's very common to see that kind of maternal language used specifically: she didn't have any biological children but her real offspring was the Reformation, a claim that probably would have horrified the historical Anne -- I doubt she would have wanted the credit she is sometimes still given for promoting reform! It is, however, the case that her presence in England indirectly contributed to the spread of ideas that developed into the later Reformation, and that this is one of the ways in which an effort to bolster one side of the 1378 schism contributed to the later fracturing of "Latin Christendom."

Also, Anne was much cuter than Wyclif clearly so she's definitely the one you'd want as the face of your movement.

have a quiz where i assign you a dissertation topic

#there actually is a dissertation that basically makes this argument#it later became the book 'from england to bohemia' by michael van dussen#it's a good book#this is not to say that anne did not personally have any cultural impact#she did just not in this manner#anne of bohemia is my forever girl

635 notes

·

View notes

Text

wip wednesday (you get guilt! and you get guilt! edition)

Didn’t do a sunday snippet this week because I’d just posted a fic on Saturday (you should go read it! It’s here!) so here’s an extra-long WIP Wednesday excerpt. This takes place during the Appellant Crisis—Richard has just had an extremely threatening meeting with the five of them, but he’s been able to persuade Henry Bolingbroke and Thomas Mowbray to have supper with him and Anne that evening (I’ve posted a few bits of that scene before). In this scene, Richard and Anne have been strategizing, but at the moment they’re mostly just kind of bummed out.

I’ve written a lot in this space about my Richard’s guilt about the Peasants’ Revolt, so I don’t think I need to belabor the point further.

CW for discussion of pregnancy loss, so I’ve put the cut in early. Dedicated readers of my fiction writing (if any) may recognize the hypothetical scenario Anne describes early in this passage.

--

She covers his hand with her own, where it rests against her belly, and they sit together in silence for a while. Then Anne sighs, deep and heartfelt, and interlaces her fingers tightly with Richard’s, clasping his hand in both of hers.

“Are you all right?” Richard says.

“I cannot help thinking,” Anne says. “Richard, if I had given you a child by now—” She swallows hard. “I have lost three babies, since we were wed. And if one of them had lived—” She presses her lips tightly together, shakes her head. “You would have an heir. And the appellants would try to use him against you, as your great-grandmother used your grandfather against your great-grandfather. And they cannot do that, and it is because all of our children have died in my womb, before they were fully formed in body or soul.” She looks up at him again, and her eyes are wet. “I know that whatever happens is the will of God,” she continues, “and I try to submit myself to it, whatever he allows to happen. But if I were to lose you—” She presses his hand more tightly in hers. “I do not know how I would go on. I would sit and weep endlessly, like Niobe. Who lost all of her children!” She shakes her head, releasing Richard’s hand, and turns her eyes heavenward. “It is a cruel mercy He has shown us,” she says. “Perhaps we should do penance, when this is over, when we are safe.”

Richard wraps his arms around Anne, pulling her close and resting his cheek against her hair. “Perhaps this is my penance,” he says. “Not yours. You haven’t caused any of this, Anne.”

“I have been complicit in securing a divorce under false pretenses,” Anne says, “on behalf of someone who is a friend. I can see that it was a sin, but I thought it was all for the best. Robert did not love Philippa, but he does not love Agnes either, not in the way he loves you. Perhaps not even in the way he loves me.” She shakes her head. “I could not abandon my dear friends to shame and disgrace, and so I helped to wrong Philippa. And now Philippa is rid of her husband, and she has every right to be glad of it, and the entire English nobility taking up her cause.” She straightens up, agitated, and Richard releases her. At a loss for something to do with her hands, she picks up her discarded embroidery from the settle and examines it for a moment, fishing for her needle among the cushions. When she finds it, she stabs it into the cloth, piercing the heart of a blackwork imperial eagle. “And—God forgive me, but it is all so much!” she cries, at last. “So much punishment, and we meant so little wrong, to have our lives ruined.”

“Anne,” Richard says, “you don’t need to take the blame for this onto yourself. God knows I have my own sins, my own failings—though they’re not the ones the Appellants accuse me of. I suppose that’s the worst of it. The lords are just as guilty of those sins as I am.”

Anne takes his hands again and looks up at him. “What do you mean?” she says.

“I’ve told you before,” Richard says, “that in the days when the commons rose up against us all, they looked to me for redress of the wrongs the lords had done—including my own forefathers. They had a watchword, you know: ‘King Richard and the true commons.’ And I heard their words, and I knew what the Lord had put me here to do: I was here to free my people from bondage.”

“I remember,” Anne says. “You were so brave. You are still brave, miláčku.”

“Everyone looked to me, then—the nobles and the councils and the great men of the city were too afraid to act, and the commons saw me as the only person who could help them. And I wanted to help them, Anne, I truly did. And then, once the crowds had dispersed and the smoke had cleared and the leaders of the rebellion were swinging from the gallows or looking down upon the city from poles, the nobles and the councils and the great men of the city swept back in and revoked all my promises for me. I suppose I knew that I would be punished for it, someday, and I suppose this must be it. I failed the least of my people, and now I’m facing retribution at the hands of the greatest, the same men who caused me to break my promises in the first place.” He sighs a little, shaking his head in disgust. “I suppose I did the same, when I tried to use my lord Tresilian against my enemies, knowing how vicious he had been in persecuting the commons. I thought—” He looks at Anne, who is still holding his hands, although her face is impassive, non-judgmental. “I thought it was for the best,” he says. “I only wonder—does the Lord mean for me to be chastened, or overthrown altogether?”

“Perhaps He is working through Bolingbroke and Mowbray,” Anne says. “It may be through them that you will keep the throne.”

Richard nods, and then snorts. “What a perfectly humiliating situation,” he says. “Henry Bolingbroke is going to preen about this for the rest of our lives, probably. Do you suppose the Lord has a sense of humor, that this is all some sort of incomprehensible joke? It’s beginning to feel like it.”

Anne straightens and reaches up to stroke his cheek. “It is all right,” she says. “If there is a need to humble ourselves before them, I will do so. It is no shame for a woman to plead. Even a queen.”

Richard bends in to press his forehead to hers. “If I have hope that the Lord will not destroy me entirely,” he says, “it’s because He sent you to me. I can’t think of a greater sign of His favor.” He cups her face gently, and kisses her lips, and Anne wraps her arms around his waist and kisses him back.

“I love you,” Anne whispers, “whatever happens. Let us be ready for them.”

#wip wednesday#the novelthing#richard ii#anne of bohemia is my forever girl#otp: my derlyng is a bundel of myrre to me#johan the mullere hath ygrounde smal smal smal

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

sunday snippet (young and sweet, only seventeen edition)

(okay, in this snippet our dancing queen has not yet reached the ABBA-approved age, since she’s actually only 15, but CLOSE ENOUGH)

Anyway I’ve been writing a lot of grim Peasants’ Revolt stuff but all the same I thought I’d post a happier moment from six months later, albeit not one completely free of awkwardness.

--

Whenever she has the chance, Anne reaches under the table and squeezes Richard’s hand, and he squeezes back and rubs his thumb over her knuckles. It always makes her giggle. She is beaming throughout the feast, her cheeks rosy and her eyes shining. Richard wonders how everything stands up to the imperial court, if what passes for splendor in England would be ordinary in her homeland—they have no trouble making conversation, but while Anne is usually eager to talk about her father’s and brother’s glittering court back in Prague, she refrains from making comparisons today, when it’s the most splendor she’s ever seen in England. But perhaps it doesn’t matter: whenever she lays eyes on him her expression is one of sheer bliss. In moments when the diners seem to be mostly distracted, Richard catches Anne’s hand and kisses it. There’s never a moment where nobody is looking, though; it draws affectionate laughs from the assembled crowd every time. Once he catches Robert’s eye, where he is seated with Philippa. Philippa smiles brightly at Richard and Anne; Robert nods briefly, enough to fulfill his duty of obeisance to his lord, and then averts his eyes. Richard frowns for an instant—now that he is married himself, he doesn’t see why Robert is so glum about the state of matrimony. Philippa has always seemed agreeable enough, after all, though of course she can’t possibly be as wonderful as Anne, who distracts him from this rather unsettling reverie by motioning to him and then feeding him a piece of candied quince.

It is well into the evening when the feasting is over, and the tables are cleared away and then there’s dancing in the hall: stately caroles and lively saltarellos and robust estampies. Anne may be sturdily built, but she is light on her feet nevertheless. Richard can scarcely take his eyes off her as they step and twirl and hop and clap, her face flushed with excitement and exertion and her hair swinging out behind her. Whenever they begin a circle dance her hand slips into his eagerly, no matter how sweaty his palms are. They are, perhaps, fortunate: they only miss their steps once or twice while caught up in one another, and Henry of Derby manages to avoid crashing directly into the two of them as a result, thanks to an effort of strength and balance heroic enough that Richard can’t be too angry at him, not at his wedding, not with Anne’s hand clasping his own. Richard, once again, ignores the stray tittering from the wedding guests and vows to build new dancing chambers in all of their palaces, just so he can see her like this as often as possible for as long as they both live.

#the novelthing#richard ii#anne of bohemia is my forever girl#sunday snippet#otp: my derlyng is a bundel of myrre to me#i love them so much#poor robert though#it's okay they will all work things out

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

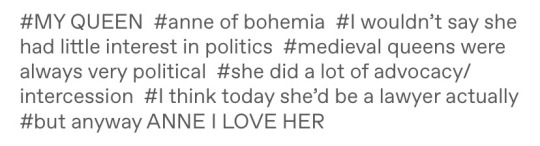

She's wearing Anne of Bohemia's badges! (The headgear is more Anne Neville though.)

Lady Queen Anne , illustration ‘ from Old Kings Cole’s Book of Nursery Rhymes, by John Byam Liston Shaw, 1901

594 notes

·

View notes