#marasuchus

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Archovember Day 6 - Lewisuchus admixtus

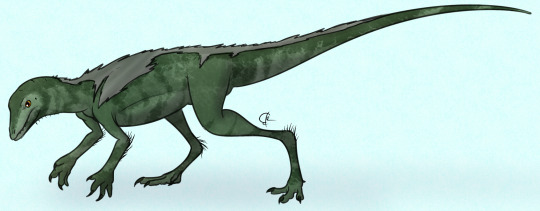

Lewisuchus admixtus was a silesaurid, a type of Triassic archosaur closely related to dinosaurs. Silesaurids all had the same general body plan: a long neck, long legs, and a mostly quadrupedal stance. However, they seem to have all filled a variety of niches. The white-tailed deer-sized Silesaurus was an insectivore. The collie-sized Kwanasaurus was an herbivore. But the smaller, earlier silesaur Lewisuchus was a carnivore, with teeth unique among silesaurids. In fact, its teeth and other anatomical features are so unique that some consider it to be a basal dinosauriform, coming before the silesaurids and dinosaurs split into two groups. It was also found with a single row of osteoderms down its back, something that other silesaurids don’t seem to have. Either way, it was a tiny, unique predator that paved the way for its strange, long-legged cousins.

Living in Late Triassic Argentina, Lewisuchus could have shared habitat with (and probably been hunted by) yesterday’s species, Herrerasaurus. But in the slightly older Chañares Formation, it was more likely to come across Proterochampsids such as Chanaresuchus, Tropidosuchus, and Gualosuchus, and probably competed with them for food. It would have also lived alongside other early dinosauriforms such as Marasuchus, early pterosauromorphs such as Lagerpeton, and the tiny pseudosuchian Gracilisuchus. Cynodonts were plentiful here, and Lewisuchus could have hunted small ones such as Probainognathus.

#my art#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#Lewisuchus#Lewisuchus admixtus#silesaurs#silesaurids#??#archosaurs#archosauromorphs#reptiles#Archovember#Archovember2023

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tarjadia and Marasuchus.

Photoshop

94 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#ArchosaurArtApril Day 2 - #marasuchus . I'm trying to get more creative with the poses. It's surprisingly hard to not do a side view when all the references are like that. Anywau, I saw some interpretations of marasuchus with feathers and I can't say no to a good fluffy boy. . . . . #archosaur#sketch #sketchbook #smltart #paleoart #animalart#animals #animalartist #drawing #pencildrawing#pencilart #traditionaldrawing #traditionalartist#traditionalart #dailydrawing #dailyart #instart#instartist #artistsoninstagram https://www.instagram.com/p/Bvwy0O0JEZ-/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=up216kiy2pkw

#archosaurartapril#marasuchus#archosaur#sketch#sketchbook#smltart#paleoart#animalart#animals#animalartist#drawing#pencildrawing#pencilart#traditionaldrawing#traditionalartist#traditionalart#dailydrawing#dailyart#instart#instartist#artistsoninstagram

42 notes

·

View notes

Note

Were dinosaurs in the early-middle triassic just a bunch of nondescript eoraptor-esque critters or were some already starting to get bigger and weirder despite the current domination of pseudosuchians and therapsids?

As far as we know, yeah they would've all been small scurrying guys. Thing is though, we have no definitive evidence of any true dinosaurs in the middle or early Triassic, except for the very un-definitive Nyasasaurus.

What we do have though are dinosauromorphs, the group of small dinosaur-y things that aren't quite yet dinosaurs! Even so, most of these also come from the late Triassic (like the fantastically leggy Marasuchus), and ones from the middle Triassic like Asilisaurus kongwe from Tanzania were absolutely part of the Tiny Little Guy genre. Like this is just a weird dog:

Image ID: Digital illustration of the small four-legged dinosauromorph Asilisaurus, in a half-crouched posture facing to the right. Its head is upright and alert, its mouth slightly open. Its body is covered in protofeathers, and mottled light brown fading to light and dark stripes on the tail. The snout is dark grey and the face has a red wattle of skin below the yellow eye. End ID.

We don't see any larger than this until the late Triassic, when dinosaur fossils seem to suddenly burst into the fossil record about 233 million years ago with Staurikosaurus and then they're everywhere!

Image ID: Size diagram of Asilisaurus and the earliest definitive dinosaur Staurikosaurus next to a light grey human silhouette. The Asilisaurus' head comes to the mid thigh of the human, and the Staurikosaurus' head comes to the human's hip. End ID.

380 notes

·

View notes

Text

A sample of Triassic terrestrial fauna, from Early to Late Triassic. From left to right: Lystrosaurus murrayi, Proterosuchus fergusi, Galesaurus planticeps, Erythrosuchus africanus, Shringasaurus indicus, Batrachotomus kupferzellensis, Dinodontosaurus turpior, Teleocrater rhadinus, Marasuchus lilloensis, Silesaurus opolensis, Hyperodapedon gordoni, Ornithosuchus woodwardi, Postosuchus kirkpatricki, Pseudochampsa ischigualastensis, Hesperosuchus agilis, Poposaurus gracilis, Blikanasaurus cromptoni, Desmatosuchus spurensis, Caelestiventus hanseni, Smilosuchus gregorii and Megazostrodon rudnerae.

#paleoart#triassic#paleoblr#paleoillustration#palaeontology#dinosaurs#palaeoblr#archosaur#therapsid#illustration#animals#palaeoart

473 notes

·

View notes

Note

What is Tawa (dinosaur)

Tawa hallae is a pretty nifty little theropod from the Late Triassic! For starters, we’ve got a couple fairly complete skeletons of it to work with, along with several bones from other individuals in the same quarry, so it’s anatomy is well known:

(Source, Scott Hartman)

But Tawa is significant though not just because it’s complete, but because it appears to be intermediate in shape and anatomy between earlier diverging predatory dinosaurs like herrerasaurs and Eoraptor and the ‘proper’ theropods like coelophysoids at the base of Neotheropoda (the ‘core’ theropods, if you will).

See, Neotheropoda is a pretty consistent group, all the major clades within it (e.g. coelophysoids, megalosauroids, allosauroids, coelurosaurs) are agreed to belong together and their relationships are considered pretty solid.

Triassic dinosaurs like herrerasaurs, Eoraptor and so on are less stable and have been more prone to jumping between positions at the base of Dinosauria because of how “primitive” they are, for a lack of better word. Eoraptor for instance has hopped around as an early sauropodomorph, theropod and outside those two all together:

(Source, Scott Hartman. Again.)

Tawa has some of the characteristics shared by neotheropods (at least initially), implying that Tawa is a close relative of them, branching off before the common ancestor of neotheropods acquired all of their traits. Other traits however are more like those of the earlier predatory dinosaurs, so it has a weird combination of ‘primitive’, ancestral traits and some of the ‘advanced’, derived traits found in neotheropods.

In that sense, it’s an intermediate between those early predatory dinosaurs and the neotheropods, both in terms of its anatomy and its evolutionary relationships. As much as the term is discouraged, I’m going to describe it as almost a textbook example of a transitional fossil, a species that diverged during the process of the evolution of a new group from an ancestral stock with a series of intermediate traits between the two.

(Source, originally from Sues et al. 2011)

The cladogram above shows herrerasaurs, Eoraptor and Daemonosaurus (misspelled with an ‘i’) and Tawa as successive branches on the line leading to neotheropods.

As is the way of things though, a lot of the early predatory dinosaurs have continued to bounce around. If you’re familiar with The Befrickening that was Ornithoscelida, you’ll know how that analysis found herrerasaurs to be related to the sauropodomorphs, rather than a true theropod, for example. But in each case, Tawa has consistently remained as the closest relative to neotheropods, so its relationship to them seems like a solid deal.

Tawa demonstrates then that neotheropods probably rose from this stock of early predatory dinosaurs somewhere, albeit if we’re not quite sure which ones yet. It at least means that it’s very unlikely the early predatory dinosaurs represent a totally distinct group of dinosaurs from the core theropods, which in the mess early dinosaur relationships currently are, is major step forward!

(Hayden Quarry dinosauromorphs, by Donna Braginetz for Issue 5836 of Science magazine.)

Tawa is also very interesting ecologically too! The fossils were discovered in Hayden Quarry in New Mexico, part of the Late Triassic Chinle Formation known for the likes of Coelophysis, Postosuchus, and Placerias of Walking With Dinosaurs fame. At this time of the Triassic, it was presumed early relatives of the dinosaurs, dinosauromorphs like Lagerpeton, Marasuchus and silesaurids, and early dinosaurs like herrerasaurs were already extinct, wiped out by their more advanced relatives. But Hayden Quarry has several of these older, ‘primitive’ groups living alongside more derived dinosaurs, including Tawa.

Tawa co-existed with Chindesaurus, a predator typically grouped with herrerasaurs, and coelophysoids. So the ancestral stock, intermediate ‘transitional species’ and the ‘advanced’ descendent forms were all still kicking about at the same time as each other. It tells us that the evolution of predatory dinosaurs, as well as dinosaurs as a whole, wasn’t as simple as the ‘advanced’ dinosaurs out competing their older, less successful antecedents, but that they lived alongside each for millions of years.

There’s plenty to say, but I think I’ve prattled on about Tawa for long-enough of a post, but I think that about covers the gist of it! Yeah, Tawa hallae, very lovely little theropod.

249 notes

·

View notes

Photo

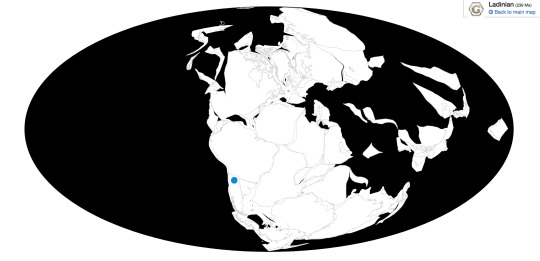

Marasuchus lilloensis

Argentina, Ladinian Age of the Middle Triassic (Chañares Formation)

A small dinosauromorph archosaur (only about 40 cm long), Marasuchus lived in the shadows of larger animals and frequent volcanic activity. Relatives of Marasuchus, the dinosaurs themselves, would go on to dominate terrestrial ecosystems for millions of years.

Read more about Marasuchus, dinosauromorphs, and the Chañares Formation at Earth Archives.

#Marasuchus#lilloensis#Lagosuchus#triassic#Ladinian#Argentina#ornithodiran#Archosaur#dinosauromorphs#dinosauriformes#dinosauromorpha#Mesozoic#illustration#natural history#Nathan E. Rogers#Earth Archives#ornithodira#Chañares Formation#volcano#volcanic ash#dinosaur#Middle Triassic#science#paleontology#paleoart#evolution

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

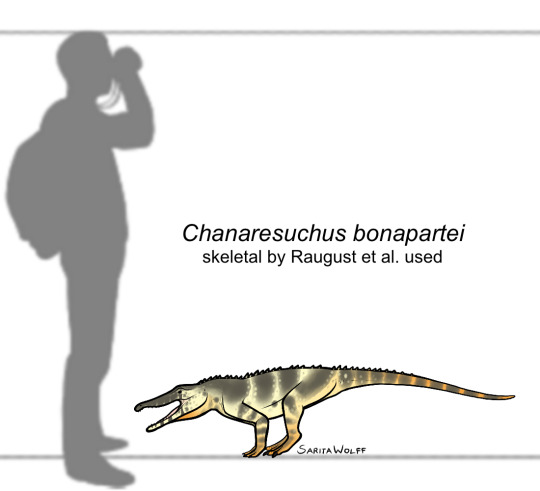

#Archovember Day 26 - Chanaresuchus bonapartei

The proterochampsians were early archosauriforms from the Triassic period. Of them, Chanaresuchus bonapartei was fairly large, living in Late Triassic Brazil. It had a long, narrow snout. Unlike many other early archosauriforms, it had very little body armour, and just a single row of small osteoderms down the back. It is hypothesized that Chanaresuchus lived a similar lifestyle to pseudosuchians and phytosaurs due to its upward facing nostrils and eyes. However, there is a distinct lack of aquatic animal fossils in the Chañares Formation, suggesting that the area was dry and arid.

Chanaresuchus would have lived alongside dicynodonts like Dinodontosaurus, cynodonts like Probainognathus and Massetognathus, silesaurs like Lewisuchus, the lagerpetid Lagerpeton, the basal dinosauriform Marasuchus, the pseudosuchians Gracilisuchus and Luperosuchus, and fellow proterochampsian Gualosuchus.

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tarjadia and Marasuchus, work in progress.

113 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Marasuchus

This is not actually a dinosaur but rather comes under the broader category of dinosauriform. Tricky!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Marasuchus lilloensis

By José Carlos Cortés on @quetzalcuetzpalin-art

PLEASE SUPPORT US ON PATREON. EACH and EVERY DONATION helps to keep this blog running! Any amount, even ONE DOLLAR is APPRECIATED! IF YOU ENJOY THIS CONTENT, please CONSIDER DONATING!

Name: Marasuchus lilloensis

Name Meaning: Mara Crocodile

First Described: 1994

Described By: Sereno & Arcucci

Classification: Avemetatarsalia, Ornithodira, Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes

Marasuchus is our first Dinosauriform! Dinosauriformes differed from the more early-derived Dinosauromorphs by having shortened forelimbs, and more of a hole in their hip socket, which would lead to a full hole in Dinosaurs proper that would allow for the fully-upright movement for which they are so famous. Marasuchus, however, would have been almost indistinguishable from Dinosaurs, very upright in its stature and extremely active in its lifestyle, as well as probably covered in filamentous integument.

By Michael B. H., CC BY-SA 3.0

Interestingly enough, Marasuchus didn’t have a hole in its hip socket, which may indicate a difference in lifestyle from other Dinosauriformes, though it did have other characteristics of this group such as an elongated pubis. Marasuchus lived about 236 to 234 million years ago, in Ladinian to Carnian ages of the Middle to Late Triassic. It was about 30 to 40 centimeters long and was decidedly bipedal, based on the structure of its arms and legs. It was found in the Los Chañares Formation of Argentina, known from every portion of the skeleton except for the skull.

Source:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marasuchus

Shout out goes to @redherringjeff!

#marasuchus#marasuchus lilloensis#dinosauromorph#dinosauriform#palaeoblr#redherringjeff#dinosaur#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#factfile#דינוזאור#Dìneasar#डायनासोर#ديناصور#ডাইনোসর#risaeðla#ڈایناسور#deinosor#恐龍#恐龙#динозавр

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

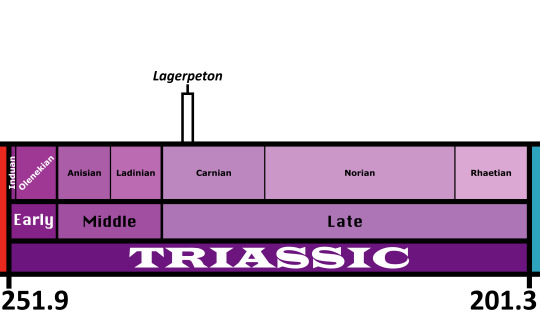

Lagerpeton

By Tas

Etymology: Rabbit Reptile

First Described By: Romer, 1971

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Osteichthyes, Sarcopterygii, Rhipidistia, Tetrapodomorpha, Eotetrapodiformes, Elpistostegalia, Stegocephalia, Tetrapoda, Reptiliomorpha, Amniota, Sauropsida, Eureptilia, Romeriida, Diapsida, Neodiapsida, Sauria, Archosauromorpha, Crocopoda, Archosauriformes, Eucrocopoda, Crurotarsi, Archosauria, Avemetarsalia, Ornithodira, Dinosauromorpha, Lagerpetidae

Referred Species: L. chanarensis

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: About 235 to 234 million years ago, in the Carnian of the Late Triassic

Lagerpeton is known from the Chañares Formation in La Rioja, Argentina

Physical Description: Lagerpeton was named as the Rabbit Reptile, and for good reason - in a lot of ways, it represents a decent attempt by reptiles in trying to do the whole hoppy-hop thing. You might think that it resembles Scleromochlus in that way, and you’d be right! Scleromochlus and Lagerpeton are close cousins, but one is on the line towards Pterosaurs - Scleromochlus - and the other is on the line towards dinosaurs - Lagerpeton. So, hopping around was an early feature that all Ornithodirans (Dinosaurs, Pterosaurs, and those closest to them) shared. Lagerpeton itself was about 70 centimeters in length, with most of that length represented as tail; it was slender and lithe, built for moving quickly through its environment. It had a small head, a long neck, and a thin body. While it had long legs, it also had somewhat long arms, and while it may have been able to walk on all fours it also would have been able to walk on two legs alone. It was digitigrade, walking only on its toes, making it an even faster animal. Its back was angled to help it in hopping and running through its environment, and its small pelvis gave it more force during hip extension while jumping. In addition to all of this, it basically only really rested its weight on two toes - giving it even more hopping ability! As a small early bird-line reptile, it would have been covered in primitive feathers all over its body (protofeathers), though what form they took we do not know.

By Scott Reid

Diet: As an early dinosaur relative, it’s more likely than not that Lagerpeton was an omnivore, though this is uncertain as its head and teeth are not known at this time.

Behavior: Lagerpeton would have been a very skittish animal, being so small in an environment of so many kinds of animals - and as such, that hopping and fast movement ability would have aided it in escaping and moving around its environment, avoiding predators and reaching new sources of food (and, potentially, chasing after smaller food itself). Lagerpeton may have also been somewhat social, moving in small groups, potentially families, to escape the predators and chase after prey together, given its common nature in its environment. As an archosaur, Lagerpeton was more likely than not to take care of its young, though we don’t know how or to what extent. The feathers it had would have been primarily thermoregulatory, and as such, they would have helped it maintain a constant body temperature - making it a very active, lithe animal.

By José Carlos Cortés

Ecosystem: Lagerpeton lived in the Chañares environment, a diverse and fascinating environment coming right after the transition from the Middle to Late Triassic epochs. Given that the first true dinosaurs are probably from the start of the Late Triassic, this makes it a hotbed for understanding the environments that the earliest dinosaurs evolved in. Since Lagerpeton is a close dinosaur relative, this helps contextualize its place within its evolutionary history. This environment was a floodplain, filled with lakes that would regularly flood depending on the season. There were many seed ferns, ferns, conifers, and horsetails. Many different animals lived here with Lagerpeton, including other Dinosauromorphs like the Silesaurid Lewisuchus/Pseudolagosuchus and the Dinosauriform Marasuchus/Lagosuchus. There were crocodilian relatives as well, such as the early suchian Gracilisuchus and the Rauisuchid Luperosuchus. There were also quite a few Proterochampsids, such as Tarjadia, Tropidosuchus, Gualosuchus, and Chanaresuchus. Synapsids also put in a good show, with the Dicynodonts Jachaleria and Dinodontosaurus, as well as Cynodonts like Probainognathus and Chiniquodon, and the herbivorous Massetognathus. Luperosuchus would have definitely been a predator Lagerpeton would have wanted to get away from - fast!

By Ripley Cook

Other: Lagerpeton is one of our earliest derived Dinosauromorphs, showing some of the earliest distinctions the dinosaur-line had compared to other archosaurs. Lagerpeton was already digitigrade - an important feature of Dinosaurs - as shown by its tracks, called Prorotodactylus. These tracks also showcase that dinosaur relatives were around as early as the Early Triassic - and that their evolution, and the rapid diversification of archosauromorphs in general, was a direct result of the end-Permian extinction.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Arcucci, A. 1986. New materials and reinterpretation of Lagerpeton chanarensis Romer (Thecodontia, Lagerpetonidae nov.) from the Middle Triassic of La Rioja, Argentina. Ameghiniana 23 (3-4): 233-242.

Arcucci, A. B. 1987. Un nuevo Lagosuchidae (Thecodontia-Pseudosuchia) de la fauna de los Chañares (Edad Reptil Chañarense, Triasico Medio), La Rioja, Argentina. Ameghiniana 24: 89 - 94.

Arcucci, A., C. A. Mariscano. 1999. A distinctive new archosaur from the Middle Triassic (Los Chañares Formation) of Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 19: 228 - 232.

Bittencourt, J. S., A. B. Arcucci, C. A. Marsicano, M. C. Langer. 2014. Osteology of the Middle Triassic archosaur Lewisuchus admixtus Romer (Chañares Formation, Argentina), its inclusivity, and relationships amongst early dinosauromorphs. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology: 1 - 31.

Brusatte, S. L., G. Niedzwiedzki, R. J. Butler. 2011. Footprints pull origin and diversification of dinosaur stem lineage deep into Early Triassic. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 278 (1708): 1107 - 1113.

Ezcurra, M. D. 2006. A review of the systematic position of the dinosauriform archosaur Eucoelophysis baldwini Sullivan & Lucas, 1999 from the Upper Triassic of New Mexico, USA. Geodiversitas 28(4):649-684.

Ezcurra, M. D. 2016. The phylogenetic relationships of basal archosauromorphs, with an emphasis on the systematics of proterosuchian archosauriformes. PeerJ 4: e1778.

Fechner, R. 2009. Morphofunctional evolution of the pelvic girdle and hindlimb of DInosauromorpha on the lineage to Sauropoda (Thesis). Ludwigs Maximillians Universita.

Fiorelli, L. E., S. Rocher, A. G. Martinelli, M. D. Ezcurra, E. Martin Hechenleitner, M. Ezpeleta. 2018. Tetrapod burrows from the Middle-Upper Triassic Chañares Formation (La Rioja, Argentina) and its palaeoecological implications. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 496: 85 - 102.

Kammerer, C. F., S. J. Nesbitt, N. H. Shubin. 2012. The first Silesaurid Dinosauriform from the Late Triassic of Morocco. Acta Palaeontological Polonica 57 (2): 277.

Kent, D. V., P. S. Malnis, C. E. Colombi, A. A. Alcober, R. N. Martinez. 2014. Age constraints on the dispersal of dinosaurs in the Late Triassic from magnetochronology of the Los Colorados Formation (Argentina). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111: 7958 - 7963.

Irmis, R. B., S. J. Nesbitt, K. Padian, N. D. Smith, A. H. Turner, D. T. Woody, and A. Downs. 2007. A Late Triassic dinosauromorph assemblage from New Mexico and the rise of dinosaurs. Science 317:358-361.

Jenkins, F. A. 1970. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. VII. The postcranial skeleton of the traversodontid Massetognathus pascuali (Therapsida, Cyondontia). Breviora 352: 1 - 28.

Langer, M. C., S. J. Nesbitt, J. S. Bittencourt, R. B. Irmis. 2013. Non-dinosaurian Dinosauromorphs. Geological Society London, Special Publications. 379 (1): 157 - 186.

Marsh, A. D. 2018. A new record of Dromomeron romeri Irmis et al., 2007 (Lagerpetidae) from the Chinle Formation of Arizona, U.S.A. PaleoBios 35:1-8.

Marsicano, C. A., R. B. Irmis, A. C. Mancuso, R. Mundil, F. Chemale. 2016. The precise temporal calibration of dinosaur origins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of AMerica 113 (3): 509 - 513.

Martz, J. W., and B. J. Small. 2019. Non-dinosaurian dinosauromorphs from the Chinle Formation (Upper Triassic) of the Eagle Basin, northern Colorado: Dromomeron romeri (Lagerpetidae) and a new taxon, Kwanasaurus williamparkeri (Silesauridae). PeerJ 7:e7551:1-71.

Nesbitt, S. J., R. B. Irmis, W. G. Parker, N. D. Smith, A. H. Turner and T. Rowe. 2009. Hindlimb osteology and distribution of basal dinosauromorphs from the Late Triassic of North America. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29(2):498-516.

Nesbitt, S. J. 2011. The early evolution of archosaurs: relationships and the origin of major clades. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 353:1-292.

Perez Loinaze, V. S., E. I. Vera, L. E. Fiorelli, J. B. Desojo. 2018. Palaeobotany and palynology of coprolites from the Late Triassic Chañares Formation of Argentina: implications for vegetation provinces and the diet of dicynodonts. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 502: 31 - 51.

Rogers, R. R., A. B. Arcucci, F. Abdala, P. C. Sereno, C. A. Forster, C. L. May. 2001. Paleoenvironment and taphonomy of the Chañares Formation tetrapod assemblage (Middle Triassic), northwestern Argentina: spectacular preservation in volcanogenic concretions. Palaios 16: 461 - 481.

Romer, A. S. 1966. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. I. Introduction. Breviora 247: 1 - 14.

Romer, A. S. 1966. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. II. Sketch of the geology of the Rio-Chañares-Rio Gualo Region. Breviora 252: 1 - 20.

Romer, A. S. 1967. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. III. Two new gomphodonts, Massetognathus pascuali and M. teruggii. Breviora 264: 1 - 25.

Romer, A. S. 1968. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. IV. The dicynodont fauna. Breviora 295: 1 - 25.

Romer, A. S. 1969. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. V. A new chiniquodontid cynodont, Probelesodon lewisi - cynodont ancestry. Breviora 333: 1 - 24.

Romer, A. S. 1970. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. VI. A chiniquodont cynodont with an incipient squamosal-dentary jaw articulation. Breviora 344: 1 - 18.

Romer, A. S. 1971. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. VIII. A fragmentary skull of a large thecodont, Luperosuchus fractus. Breviora 373: 1 - 8.

Romer, A. S. 1971. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. IX: The Chanares Formation. Breviora 377: 1 - 8.

Romer, A. S. 1971. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. X. Two new but incompletely known long-limbed pseudosuchians. Breviora 378:1-10.

Romer, A. S. 1971. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XI. Two new long-snouted thecodonts, Chanaresuchus and Gualosuchus. Breviora 379: 1 - 22.

Romer, A. S. 1972. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XII. The post cranial skeleton of the thecodont Chanaresuchus. Breviora 385: 1 - 21.

Romer, A. S. 1972. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XIII. A fragmentary skull of a large thecodont, Luperosuchus fractus. Breviora 389: 1 - 8.

Romer, A. S. 1972. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. Lewisuchus admixtus, gen. et sp. Nov., a further thecodont from the Chañares beds. Breviora 390: 1 - 13.

Romer, A. S. 1972. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XV. Further remains of the thecodonts Lagerpeton and Lagosuchus. Breviora 394: 1 - 7.

Romer, A. S. 1972. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XVI. Thecodont classification. Breviora 395:1-24.

Romer, A. S. 1972. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XVII. The Chañares gomphodonts. Breviora 396: 1 - 9.

Romer, A. S. 1973. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XVIII. Probelesodon minor, a new species of carnivorous cynodont; family Probainognathidae nov. Breviora 401: 1 - 4.

Romer, A. S., and A. D. Lewis. 1973. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XIX. Postcranial materials of the cynodonts Probelesodon and Probainognathus. Breviora 407: 1 - 26.

Romer, A. S. 1973. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XX. Summary. Breviora 413: 1 - 20.

Sereno, P. C., and A. B. Arcucci. 1994. Dinosaurian precursors from the Middle Triassic of Argentina: Marasuchus lilloensis, gen. nov. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 14(1):53-73.

#Lagerpeton#Dinosaurmorph#Lagerpetid#Triassic#Palaeoblr#Triassic Madness#Ornithodiran#Triassic March Madness#South America#Omnivore#Prehistoric Life#Prehistory#Palaeontology#Lagerpeton chanarensis#dinosaur#paleontology#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#factfile

365 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lagosuchus talampayensis

By José Carlos Cortés

Etymology: Rabbit Crocodile

First Described By: Romer, 1971

Classification: Dinosauromorpha

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: About 238 million years ago, in the Ladinian age of the Middle Triassic

Lagosuchus is found in the Chañares Formation of Argentina

Physical Description: Lagosuchus was an early Dinosauromorph, aka the group that includes dinosaurs and all their closest relatives. Thus, Lagosuchus is one of many early archosaurs that showcase the origins of all dinosaurs! Lagosuchus isn’t known from particularly good remains, but it does show it was a lightly built, agile animal, which was probably bipedal and spent most of its times on its toes. At about 30 centimeters in length, it was around the size of a ferret. Its legs were amazingly long, and its toes were too, giving it good speed. It had an almost-erect posture - without the open hip sockets of dinosaurs proper, it couldn’t hold its legs directly underneath its body, but it almost could. Its forelimbs are a bit more murky, though it seems likely that Lagosuchus moved on all fours most of the time, switching to two legs when it needed to move quickly from place to place. Being an early dinosauromorph, it would have had some covering of protofeathers, though how much is a bit of question.

Diet: Lagosuchus was probably an omnivore, given the fact that early dinosaurs probably came from omnivorous origins

Behavior: Lagosuchus would have been a moderately active animal - close to a warm-blooded metabolism but not quite. As such, it probably would have spent most of its time on the move, hunting for food or searching for grubs and possibly plants it could have eaten. Lagosuchus could have used its speed to run away from predators, which were very common in its environment; and, of course, running after its own food!

It is uncertain if Lagosuchus was a social animal, or if it took care of its young; but it seems likely for the latter at least.

By Ripley Cook

Ecosystem: The Chañares Formation was a middle triassic microcosm of the explosion of evolution occurring in the Triassic, showcasing a wide variety of animals evolving in the aftermath of the Permian mass extinction. This was a low lying lake system, filled with horsetails, ferns, and some nearby conifer trees. It was also very warm, though not as warm as locations closer to the equator. There were many kinds of animals - large predatory pseudosuchians that would have hunted Lagosuchus such as Gracilisuchus, Luperosuchus, and Tarjadia; other Avemetatarsalians such as Marasuchus, Pseudolagosuchus, Lewisuchus, and Lagerpeton; the carnivorous almost-mammals Probainoganthus and Chiniquodon; the herbivorous almost-mammal Massetognathus; giant Dicynodont herbivores like Dinodontosaurus and Jachaleria; and finally the vaguely-crocodile-like Proterochampsids Gualosuchus, Chanaresuchus, and Tropidosuchus. A fascinating community indeed!

Other: Lagosuchus isn’t a particularly well known dinosauromorph; fossils assigned to it at one point that are well known, Marasuchus, have been given their own genus. It is possible that Lagosuchus is, thus, closer to dinosaurs in relationship than we think just on its own without evidence from Marasuchus. More studying of these fossils is necessary to come to better conclusions.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Arcucci, A.B. 1987. Un nuevo Lagosuchidae (Thecodontia-Pseudosuchia) de la fauna de Los Chañares (Edad Reptil Chañarense, Triasico Medio), La Rioja, Argentina. Ameghiniana 24. 89–94.

Arcucci, A., and C.A. Marsicano. 1999. A distinctive new archosaur from the Middle Triassic (Los Chañares Formation) of Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 19. 228–232.

Bittencourt, Jonathas S.; Andrea B. Arcucci; Claudia A. Marsicano, and Max C. Langer. 2014. Osteology of the Middle Triassic archosaur Lewisuchus admixtus Romer (Chañares Formation, Argentina), its inclusivity, and relationships amongst early dinosauromorphs. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology _. 1–31.

Fiorelli, Lucas E.; Sebastián Rocher; Agustín G. Martinelli; Martín D. Ezcurra; E. Martín Hechenleitner, and Miguel Ezpeleta. 2018. Tetrapod burrows from the Middle–Upper Triassic Chañares Formation (La Rioja, Argentina) and its palaeoecological implications. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 496. 85–102.

Jose, B. 1975. "Nuevos materiales de Lagosuchus talampayensis Romer (Thecodontia-Pseudosuchia) y su significado en el origen de los Saurischia: Chañarense inferior, Triásico medio de Argentina." Acta Geológica Lilloana. 13 (1): 5–90.

Kent, Dennis V.; Paula Santi Malnis; Carina E. Colombi; Oscar A. Alcober, and Ricardo N. Martínez. 2014. Age constraints on the dispersal of dinosaurs in the Late Triassic from magnetochronology of the Los Colorados Formation (Argentina). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111. 7958–7963.

Marsicano, C. A., R. B. Irmis, A. C. Mancuso, R. Mundil, F. Chemale. 2016. "The precise temporal calibration of dinosaur origins". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (3): 509–513.

Nesbitt, S.J. 2011. "The Early Evolution of Archosaurs: Relationships and the Origin of Major Clades" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 352: 189.

Romer, A. S. 1971. "The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. X. Two new but incompletely known long-limbed pseudosuchians". Breviora. 378: 1–10.

Romer, A. S. 1972. "The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XV. Further remains of the thecodonts Lagerpeton and Lagosuchus". Breviora. 394: 1–7.

Palmer, D., ed. 1999. The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 97.

Paul, G. 1988. Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. Simon & Schuster.

Perez Loinaze, V. S., E. I. Vera, L. E. Fiorelli, J. B. Desojo. 2018. Palaeobotany and palynology of coprolites from the Late Triassic Chañares Formation of Argentina: implications for vegetation provinces and the diet of dicynodonts. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 502: 31 - 51.

Pontzer, H., V. Allen, J. R. Hutchinson. 2009. "Biomechanics of Running Indicates Endothermy in Bipedal Dinosaurs". PLoS ONE. 4 (12): e7783.

Rogers, R.R.; A.B. Arcucci; F. Abdala; P.C. Sereno; C.A. Forster, and C.L. May. 2001. Paleoenvironment and taphonomy of the Chañares Formation tetrapod assemblage (Middle Triassic), northwestern Argentina: spectacular preservation in volcanogenic concretions. Palaios 16. 461–481.

Sereno, P. C., A. B. Arcucci. 1994. "Dinosaurian precursors from the Middle Triassic of Argentina: Marasuchus lilloensis, gen. nov". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 14 (1): 53–73.

#Lagosuchus#Lagosuchus talampayensis#Dinosauromorph#Prehistoric Life#Paleontology#prehistory#Outside Saurischia & Ornithischia#Triassic#South America#Omnivore#Mesozoic Monday

215 notes

·

View notes