#manhattan melodrama

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Myrna Loy presents a birthday cake to Director W.S. Van Dyke II on the set of the 1934 film Manhattan Melodrama.

Van Dyke went on to direct Myrna in another film in 1934, The Thin Man!

Manhattan Melodrama was the first film pairing of William Powell and Myrna Loy.

Besides The Thin Man, Van Dyke also directed Powell and Loy in After The Thin Man (1936), Another Thin Man (1939), I Love You Again (1940), and Shadow of The Thin Man (1941). Known for his rapid directing style, he was known as "One take Woody." After being diagnosed with heart disease and cancer, Van Dyke committed suicide in February 1943, aged 53.

#Myrna and cake#Myrna Loy and cake#myrna loy#w s van dyke#manhattan melodrama#old hollywood#1934#Woodbridge Strong Van Dyke II#One take Woody

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

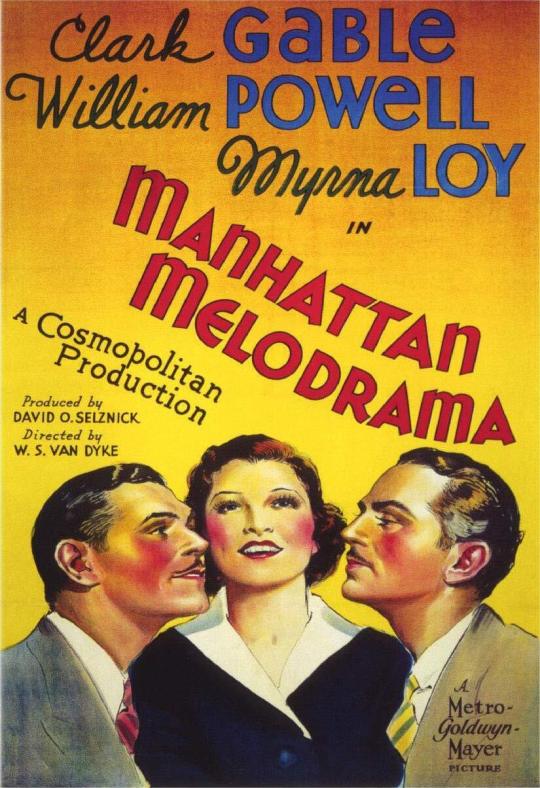

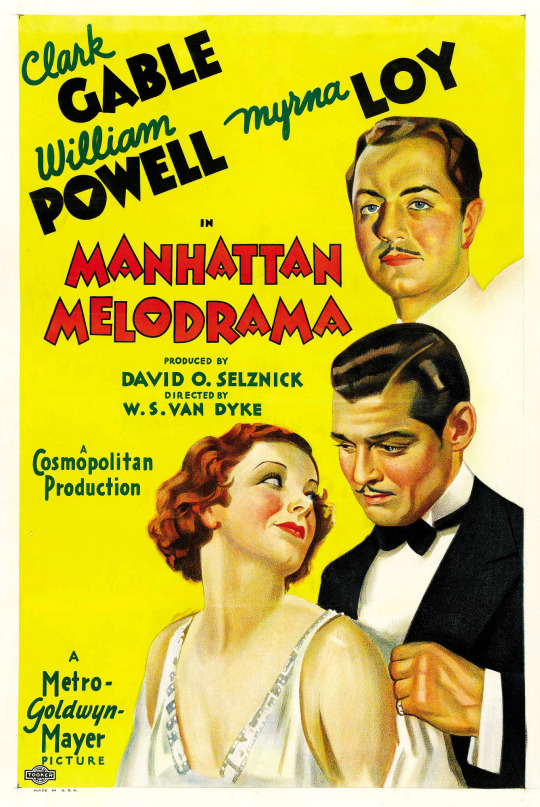

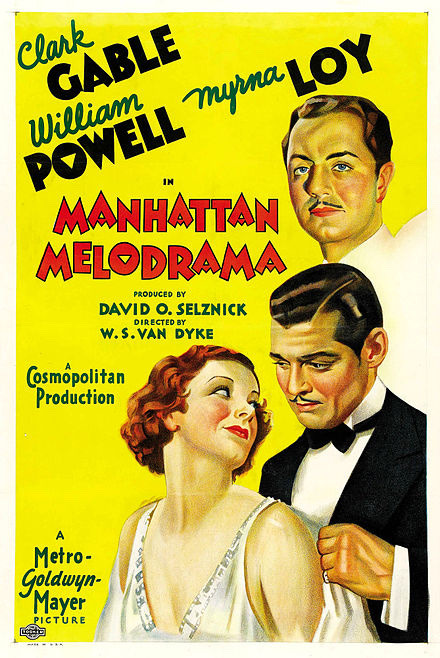

Manhattan Melodrama (1934) W.S. Van Dyke

April 14th 2024

#manhattan melodrama#1934#w. s. van dyke#clark gable#myrna loy#william powell#nat pendleton#leo carrillo#isabel jewell#muriel evans#pre-code#PreCodeApril

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

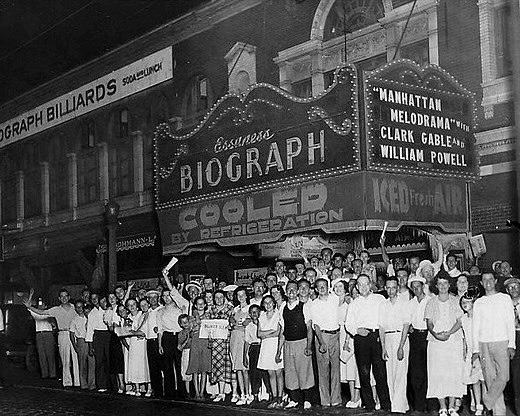

On July 22, 1934, “Public Enemy No. 1″ John Dillinger is killed in a hail of bullets fired by federal agents outside Chicago’s Biograph Theatre. Dillinger and friend Anna Sage, who cooperated with the FBI, were there to see W.S. Van Dyke’s MANHATTAN MELODRAMA. #OnThisDay

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Manhattan Melodrama (1934)

#manhattan melodrama#pre code hollywood#clark gable#william powell#myrna loy#old hollywood#classic hollywood

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sketch of Judge Andrew Crane in 1881 before the police turned him into Donkey.He had legally ordered Rev.Charles Darwin to be sent to the Nimitz Mental Institution after Rev. Charles Darwin was caught turning his congregation into Monkey and Gorilla.

#GIFER#movies#clark gable#myrna loy#william powell#manhattan melodrama#gif#gifs#DeathOfJudgeAndrewCrane

1 note

·

View note

Text

Oh cool, I wanted to see what year it was in case they didn't actually name the Garbo picture, and the film posters confirm mid-1934 at earliest

The Prime English subtitles disappeared for this episode, so I've no idea what the Mandarin audio actually said

I wonder if it's The Painted Veil? It's the right year and it's a Garbo film set in China, so seems appropriate

#she done him wrong is 1933 but it could have taken a while to get to Shanghai or stayed in theaters if successful#it is a great film#miss s#Miss s detective agency#miss fisher's murder mysteries#remake cdrama#she done him wrong#Manhattan melodrama#the painted veil#Greta Garbo#if it is the painted veil that makes this November 1934 or later

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Donde el Destino Decida Llevarnos (on Wattpad) https://www.wattpad.com/story/271668789-donde-el-destino-decida-llevarnos?utm_source=web&utm_medium=tumblr&utm_content=share_myworks&wp_uname=badezimmr&wp_originator=%2BOgzW4Z0R%2BnU7Wzry3PamQaCXyKyFrZUVFbBST2NXDbP4TluNr00V%2FjYANgiTfsA2K1u32wKu%2BsUCww1VENCmKLFmYdlymZaQ62s7WFPzESrJXXnjG2SKAFoABzW18RR La vida parece ser un sueño, un sentimiento inefable que de un instante a otro puede dar un giro drástico. Eloane St Aymour es una neoyorquina con una vida despreocupada, su único dilema es decidir qué rumbo darle a su futuro. Después de una anticipada decepción al graduarse de la preparatoria, entra a la universidad menos imaginada. Nuevos amigos, despedidas inesperadas y la constante culpa de no poder cuidar a las personas que ama la acompañan en el camino. Ese era el comienzo de todo lo que Eloane tenía que experimentar para descubrir los secretos que la habían llevado hasta el abismo, pero todo parece ser parte de un sueño del cual eventualmente despertará.

#amor#college#comienzos#depresion#desamor#destino#drama#esperanza#finalinesperado#girosinesperados#insomnio#manhattan#melodrama#misterio#nuevocomienzo#oniria#secretos#sueos#universidad#universitarios#books#wattpad#amwriting

1 note

·

View note

Text

Jimmy Butler (1920-1945) in No Greater Glory (1934)

Jimmy Butler (1920-1945) in Manhattan Melodrama (1934)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Propaganda

Mbissine Thérèse Diop (Black Girl)—She’s a Senegalese actress known for starring in Black Girl, one of the first African films to receive international attention/acclaim. So much of the movie relies on her ability to convey her character’s sense of isolation/loneliness, she’s so amazing, I really wish she had acted more. However, she just recently appeared in the film Cuties!

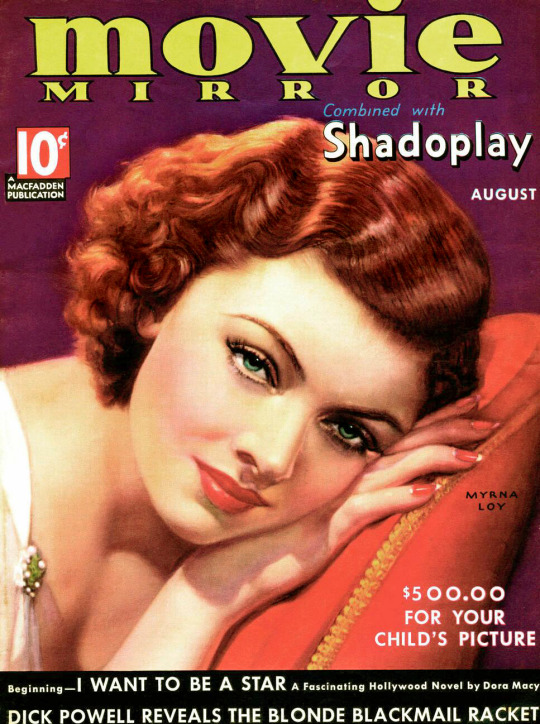

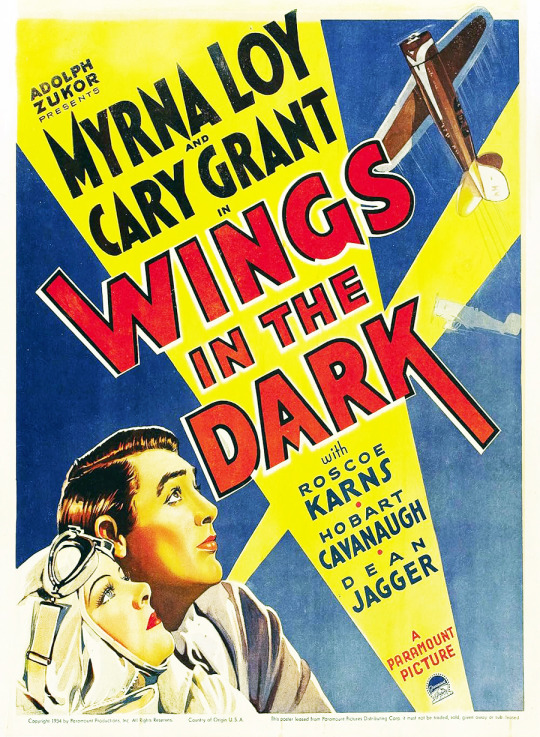

Myrna Loy (The Thin Man, Manhattan Melodrama, Mr Blandings Builds his Dream House)—Started out a slinky silent screen vamp. Became a screwball lead who had a blast drinking, being married to William Powell, solving mysteries, and taking her dog everywhere in the Thin Man Movies. Broke our hearts in The Best Years of Our Lives and played a string of dream wives. Remained hot the entire time. Decades of hotness.

This is round 3 of the tournament. All other polls in this bracket can be found here. Please reblog with further support of your beloved hot sexy vintage woman.

[additional propaganda submitted under the cut.]

Mbissine Thérèse Diop:

Myrna Loy:

Myrna Loy excelled at playing coy women, so common in screwball comedies in the 40s. She batted her lashes, and shrugged with grace, and made her costars look like foolish heels next to her. She charmed with sneaky elegance, well-placed pouting, and repartee. Besides, she was sultry AF.

While Myrna certainly looked hot in some her earlier vampy exotic bad girl roles, I think shes hottest when her comedic chops got to be displayed. Her dry wit, comedic timing, and subtle facial expressions make her the queen of deadpan snark.

She's just very Mother

So beautiful and popular she was crowned Queen of the Movies in 1936, Myrna Loy was also an amazing actress. She's best remembered for The Thin Man and sequels, where she gets to show off her comedy skills, adding irresistible impish charm to her classic beauty and dancer's figure.

THE SASS

One of the few actresses who managed to successfully transition from silent to talkies, never won an Oscar but was at one time the highest paid woman in Hollywood. Advocated for better roles and pay for Black actors in the 1930s, so passionately anti-Nazi in the 40s she made Hitler's blacklist, spoke out against Joseph McCarthy during the Red Scare, and advocated for fair housing in the 1950s and 1960s, all while being hot as fuck opposite William Powell, Clark Gable, Cary Grant, Spencer Tracy and a whole galaxy of the Hot Vintage Men Poll all-stars.

Cute as a button with so much RIZZ! She and whatsisname in The Thin Man are relationship goals.

She was literally called the Queen of Hollywood! She is so sassy and funny in the whole Thin Man series. Absolutely hot in those, and who doesn’t love a woman who can laugh? She had the sultriest gaze and that style! Also before she was a star she sat as the model for an iconic statue for a school (representing “Fountain of Education”).

the glamour!! the banter!! the comedy!!

She's got this cute kinda scrunched up face AND shes funny AND shes got a bangin body.

273 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fable

Manhattan, February 1774 - Part 2

“That was President Cooper’s house.” Alexander let the curtain slip from his fingers as the carriage trundled on with no apparent intention of stopping. “I- uhm, I think your driver’s missed it.”

“It’s not Cooper's house we’re visiting tonight.”

A mild answer and then silence, so Mister Mulligan was not going to explain further.

Alexander sat back in his seat, twisted his neck against the stiff-ribbed collar, pulled his sleeves down so they’d stop bunching under his arms. Mulligan’s shoe buckles, his powdered hair, his rings, the fraying paper lining the inside of his coach, he struggled to find anything worth fixing his gaze on. The wheels kept rumbling underfoot.

It had made sense to assume this dinner was with Miles Cooper. Alexander had spent all his time for the last few weeks on Cooper’s assignment, and Hercules’ brother, Hugh, had been his host in Boston for the trip. He had been adamant that Alex should volunteer. So, Alex had thought- perhaps they had discussed the whole trip in advance.

But, perhaps not.

“Stop fidgeting with that.”

Alex’s thumbnail was scratching at the hem of his cuff. He pushed his sleeve back to his wrist.

“Best manners tonight.”

Alex cocked his head in wry acquiescence.

It was a point that Mister Mulligan had impressed thoroughly. When he’d brought Alexander to his shop and put him on the step riser to fit him with a finely-embroidered waistcoat, Alex had assumed he was only doing this to support some business with the university president, perhaps another elite party he was angling to host, perhaps a new contract to provide the school with uniform designs, perhaps he was being propped up as his son's tutor in hopes of securing his future enrollment.

Obviously, he wasn’t here to impress Cooper tonight, but Alex was still dressed in ridiculous finery for a reason and if he was going to titillate for another man’s interests, it would help him to at least know whom he was dazzling and why. “You said to be prepared to discuss my essay about the tea party,” he said. “I brought my notes.”

“And we will discuss them,” Mulligan leaned to peer out the window anxiously- as if their voices might drift onto the streets as they passed. “But not with Miles Cooper.”

“Then who?”

After biting his lip another moment, the tailor finally seemed to decide they were far enough away from Broadway. He drew the curtain. “When you came to this city, you followed recommendations from the Creugers, the Livingstons, the Lees. My own brother insisted you were brilliant- the most-driven, most relentless person he’d ever met. Everyone I knew was telling me I should take care to guide your energies because you could be a force in society. I told you as much.”

Alexander was taken aback by the flattery, immediately suspicious. In truth, he had neglected countless opportunities with the university in favor of involving himself in petty local politics and debates. Despite the fancy new clothes and the arranged dinner with a mysterious friend in high society, Alexander was bracing for Mulligan to say he hadn’t lived up to his reputation.

Instead, Mulligan asked, “Do you remember what you said to me?”

Alex blinked.

“You said that you got lucky.” Mulligan smiled, a slow, slanted stretch that reached up to his brows as if the conversation still amused him.

Alex remembered it, vaguely, but he was sure, “I didn’t use that word.”

“No, you said something about destiny being kind to you...or something to that effect.” He grinned as if the melodrama in that also amused him, “And I agree. It’s fortunate that you’ve come here, and it’s fortunate that you did so now."

"So, you have some grand plans for my essay." Alex said, hoping for the point of this, "You could be straightforward with them. Just this once."

Mulligan's smile clearly said he would not. "Before I bring you into this fold, I need you to understand why I'm doing it. Out of all the rising stars in your class, all your Corsican friends and the young scions of business and law that come in and out of my shop, I'm recommending you because you understand that your success has been arbitrary. Half your friends are convinced it was their own hard work that got them there, but men more brilliant than either of us are starving to death in the gutters while we'll attend an invitation from men half as brilliant and twice as rich. It's all arbitrary. Luck."

"I didn't say luck," Alex repeated.

"Fine. Destiny. Whatever you call it, it cannot be earned or returned. Someone who knows that it was mere luck that granted them the chance to be a contender- they won't delude themselves to believe it's their own actions that grant them opportunities and power. They'll recognize it as a fleeting blessing and they won't squander it."

"It seems to me that the opportunity I'm obliged not to squander right now is my education..." Alexander said.

He was pleased with the roll of Mulligan's eyes. "We both know how much of your energy that requires."

It was true that Alex would find some other way to distract himself if not this, but, "You're encouraging me to a task that I haven't even heard yet," he said. "I appreciate everything you've done for me in the last few months, but I'm not your blunt instrument."

Mulligan's mouth pinched at that. "Hardly mine- as I said, I'm recommending you tonight," he leaned and peeked out the curtain again as the carriage started to slow. "But, you should know- we are all tools. Each of us with talents and skills that could benefit our communities and ourselves. Not many of us are lucky enough to be situated so close to someone who can use us properly.”

To use him properly, Alexander's eyes narrowed. He was no stranger to Mulligan's whiggish tendencies, and he had attended Mulligan's drawing room for enough after-dinner conversations to know whom he was referring to when he was raving over 'tools'.

"So, are we meeting with James Rivington? Preventing the publication or trying to secure the rights to final edits?"

It seemed like the obvious answer. President Cooper would arrange a publication regardless of what Alexander wrote, and the Royal Gazette would be a possibility. Moreover, it would be a forum prestigious enough to perhaps merit these ridiculous clothes, especially if Rivington was entertaining.

But, Alex quickly reconsidered- "No, this isn't about avoiding or nulling the work, you're suggesting I should make myself a tool to..."

The carriage stopped.

Alex's eyes widened.

They were at the end of John Street near Golden Hill. The list of names narrowed, and the sly quirk of Mulligan's mouth left only one answer.

"King Isaac..."

That earned a full-throated laugh.

Alex wanted to grab the guess out of the air and swallow it back down. But, there wasn't any unkindness on Mulligan's face, and Alexander knew he was right.

He knew that, before Hercules married Elizabeth, he'd been an active member of the Sons of Liberty, a steady friend to their leaders. He had not known whether those connections were still intact.

He was pleased to discover they were, but “When I hoped for a chance to be useful, I always imagined it as a sword rather than a pen,” he said.

Mulligan had the decency not to laugh.

Alex could've covered his mouth if his arms weren't so stiff in this coat. He hadn't meant to speak of his hopes. He felt the embarrassed flush in his own cold cheeks, keenly aware of how he looked- slender, paltry; how he carried himself- rangy and bookish at best. He was aware of how ridiculous it must sound, someone like him wanting to fight.

But, if the Sons of Liberty needed a reporter and they were recruiting, that meant that they were planning as well. It meant that action was coming to New York- perhaps to Manhattan- perhaps an action like that at Griffin's Wharf in Boston. An action which it seemed like Alexander was about to be asked to promote and defend in writing rather than participate in...

“Perhaps that opportunity will come," Mulligan said. "For now, I think it will be fine to seize this chance, help in the best way you can, and we can hope that fortune continues to favor you.”

Alex said nothing.

“You’re pouting.”

“I’m not pouting.”

“You are."

The carriage door opened and Cato lowered the step for them. Mulligan didn't move to get out though, watching Alexander's face for some implacable signal of recognition.

Finally, Alex couldn't stand it anymore. He grabbed his parcel of notes and turned to crawl out of the carriage first.

They were only about a mile away from Mulligan's shop, but the only time Alexander had ever been this far north in Manhattan was when he first arrived and made obligatory visits to the Beekman family and Crueger's associates.

The houses here would be more-aptly described as mansions. The one they'd pulled up to was elegantly lit, attended by a full staff of well-dressed slaves in high, stiff collars much like the one that was currently chaffing Alexander's neck, though maybe with even more lavish embroidery.

Mulligan's heels clacked primly behind him, careful steps to avoid slipping in the icy road until he reached the carpet laid out by their host. He offered up his arm for Alex to take and they walked up the front lawn towards the columned portico.

"Y'know, I think Excalibur was a lucky sword to be put in that stone," he said. "But it still had to wait to be drawn.”

Alex laughed. The noise shocked out of him, because it was oddly kind. A trifling and silly reference to a fanciful story, but inexplicably comforting. It made him willing to trifle back, so, “What does that make you then? King Arthur?”

"Heavens, no!" Mulligan chuckled, "You're right that Isaac's already laid claim to the title 'King' around here. Merlin, perhaps?” He twirled his hands as if he were conjuring something in the air around his head, a mockery of divination. “And I see great things ahead for you. But, let's not call him 'King' here- Mister Sears in tonight's company, yes?” He patted the back of Alex’s hand where it was curled around his arm. “Best manners."

Alex nodded even though he still didn't know precisely who 'tonight's company' entailed.

Part 2

#ficlet#title's reference to Gigi Perez song#1 of 2#shaking out the cobwebs#historical hamilton#hercules mulligan

36 notes

·

View notes

Note

From disney there was an animated series called Gargoyles from the 90s.

Goliath's narration in the opening: One thousand years ago, superstition and the sword ruled. It was a time of darkness. It was a world of fear. It was the age of gargoyles. Stone by day, warriors by night, We were betrayed by the humans we had sworn to protect, frozen in stone by a magic spell for a thousand years. Now, here in Manhattan, the spell is broken, and we live again! We are defenders of the night! We are gargoyles!

That series was noted for dark tone, complex story arcs and melodrama, the character arcs were through in the series, as were shakespearean themes.

That animation had received comparison from other series Cybersix, Batman: The Animated Series and X-men.

Oh I know about that one alright

It’s a classic XD

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Haunted Atlas

Biograph Theater - Chicago, Illinois, United States

41°55′35″N / 87°38′59″W

The Biograph Theater is located on the north side of town and gained fame when Dillinger was gunned down near the alley outside on July 22, 1934.

Dillinger (1903-1934) enjoyed a spectacular career as a robber, earning him the title of the first Public Enemy Number One. Born in Indianapolis in 1902, he started his crime life at a young age, when he linked with the Dirty Dozen gang and stole coal from the Pennsylvania Railroad.

In 1924, Dillinger's professional crime life began with the attempted robbery and assault of a grocer. He served nine years in prison in Mooresville, Indiana, and was released in 1933. His time in jail was well spent, for he got to know many bank robbers who later became his accomplices.

Once out of prison, Dillinger became a robber in earnest, moving from city to city. In the space of 11 months, he robbed between 10 and 20 banks, plus police arsenals. He seemed to be a magic escape artist, evading traps set for him, and once even escaping from jail armed with a phony wooden gun. He murdered 10 men and wounded many more. A $10,000 reward was offered for him, dead or alive.

Dillinger hid at the home of his waitress girlfriend, Polly Hamilton. He was betrayed by Anne Sage (real name Anne Cumpanis), Hamilton's roommate. Sage was in danger of being deported and struck a deal with the federal government to inform on Dillinger in exchange for staying in the United States.

The fateful night came on July 22, 1934, when Dillinger took Sage and Hamilton to the Biograph Theater to see Manhattan Melodrama, starring Clark Gable. Dillinger was well dressed and wearing a straw hat. Melvin Purvis, the head of the FBI in Chicago, set up a trap. Sage would identify herself by wearing a red dress (actually orange).

When Dillinger exited the theater at 10:40 P.M. with the two women, one in a reddish dress, Purvis signaled his waiting agents to draw their guns. He identified himself to Dillinger and ordered him to surrender. Dillinger turned and fled toward an alley. FBI agents fired on him. Two bullets hit his left side and one entered his back and exited through his right eye, tearing it to bits. Dillinger was killed instantly and collapsed just short of the alley. He was rushed to Alexian Brothers Hospital, even though he was already dead.

Sage, who became known as the "Lady in Red," was paid $5,000 by the federal government for her part—but was deported anyway.

According to lore, instant souvenir hunters dabbed handkerchiefs in Dillinger's blood at the scene, before his body was whisked away to the hospital. Others hunted for bullet fragments.

Since that violent night, passersby have reported seeing glimpses of a ghostly replay of the killing. A blue-gray silhouette of a man is seen leaving the theater, running toward the alley, falling, hitting the pavement, and then disappearing. A ghostly figure also is seen hovering near the spot where Dillinger fell dead. The alley is known as "Dillinger's Alley.” The Biograph has gained a reputation for being haunted too; visitors can sit in the same seat once occupied by Dillinger on the last night of his life.

Popular lore persists that the man killed that night was not Dillinger, but a small-time criminal. Dillinger himself is said to have gotten away and lived out his life under a new identity. Little evidence exists to support the belief, which seems to be rooted in a common romanticism that denies the deaths of famous-and infamous-figures.

Text from The Encyclopedia of Ghosts and Spirits, Third Edition by Rosemary Ellen Guiley (Checkmark Books - 2007)

#the haunted atlas#biograph theater#John Dillinger#chicago#illinois#ghosts#haunted locations#spirits#apparitions

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nini's Fic Masterlist

I mean you could also just go look at AO3 for this...

Nothing is ever fully abandoned, but yeah, some of these WIPs have been lingering for a few years. Sorry.

Cherik Fic

This far but no further & What stays and what fades away Mpreg melodrama followed by married couple shenanigans.

Is It Casual Now? Star Wars AU. Raven and Charles get into trouble and have to call Charles' ex, Erik, for help.

Can't Buy Me Love Maid in Manhattan AU. The part of Jennifer Lopez is played by Erik Lehnsherr.

The Boys All Love to Stare High school AU porn.

Hitting It Off Erik meets the perfect guy at the bar. Too bad Mr. Perfect is on a date with someone else...

On a Beach, With You (The Tel Aviv Remix) Charles Xavier meets Erik Lehnsherr on a beach in Israel.

Lucid Dreaming (The Just a Dream Remix) Charles is dreaming that Erik’s in his bed.

Office Hours Charles and Erik fuck in a bathroom.

Brimnes Erik helps Charles put together Ikea furniture.

Mint to Be Erik winds up in the ER with a candy cane stuck up his dick.

Running With You WIP Charles and Raven at Oxford.

------------------------------------------------

MCU Fic

Lucid Dreaming WIP The life Peter's been living ever since Endgame is all a lie.

A Thousand Lies (and a good disguise) Tony is responsible for creating the spider that gives Peter powers.

the long game Biodad au where Peter gets arrested for selling drugs, and that actually improves his life.

What's In a Name? Morgan starts calling Tony "Mr. Stark."

How to Get Banned from Monaco (again) Tony, Rhodey, and Peter go to Monaco for the grand prix.

the ghost at the back of your closet WIP Tony lives AU. The DODC charges both May and Tony with child endangerment for letting Peter go out as Spider-Man.

Extraction WIP Peter is kidnapped to a foreign country, and Tony is the contractor sent in to get him out.

The Simple Life The 8-year-old kid Tony didn't know he had turns up on his doorstep.

Since You've Been Gone Pepper solves a mystery.

Papa-Paparazzi The media thinks Tony is Peter's dad.

the one where Bucky kidnapped Peter Stark as a toddler SERIES Biodad AU where Peter was kidnapped and doesn't return home until he's 15.

Different Shapes and Sizes Aunt May meets the other Spider-Men.

Just Part of the Costume Peter wears a thong under his suit.

The Hottest Toy of the Season Uncle Ben is on a mission to find little Peter the Iron Man toy he wants.

The Best Thanksgiving Ever Tony' in-laws make some assumptions about his relationship with Peter. Also, they blow up a turkey.

A 10 Step Plan for Saving Your Mentor’s Life (a Guide by Peter Parker) WIP Tony takes Peter on a training mission that goes horribly wrong.

Tony Shark (doo doo do do do do) Undersea adventure.

I tamagot-chu (if you tamagot-me) Peter and Ned transfer Karen into a tamagotchi.

miles and miles to go (before I dream) The only chance of beating Thanos requires bringing Loki back from the dead.

------------------------------------------------

Captive Prince Fic

The Stowaway WIP Star Wars AU. Damen and Nikandros are pilots who find someone hiding in their ship's hold.

The Boyfriend Experience WIP Laurent's a hooker and Damen's the client who's in love with him.

All the Education (that I missed) Teacher!Damen and Student!Laurent, sort of.

Verisimilitude Auguste/Laurent. Laurent is intent on helping Auguste with a mission.

A Kansas City Shuffle FBI Agent!Damen and Criminal Consultant!Laurent. White Collar AU.

Frigid Huddling for warmth.

A Luxury Few Can Afford Laurent is undercover as the prince's pet when he meets Damen.

A Poorer Prospect Laurent is marrying a Patran princess, Damen attends the wedding.

Frisking Attempts at roleplay.

Sunburn Laurent burns easily.

Catalyst College AU. Damen makes a bet about being able to seduce Laurent.

------------------------------------------------

Lymond Fic

Cat Sitting Richard is tasked with babysitting his younger siblings.

Play to Win Lymond and Will get trapped in the Midculter cellar and decide to get drunk and play cards.

Inspection Duty On the eve of the Battle of Solway Moss, Jerott Blyth takes it upon himself to inspect the camp. He finds more than he expected.

------------------------------------------------

Star Wars Fic

relieved to lie in the wreckage Post-ROTS, Anakin is on the run.

------------------------------------------------

Glee Fic

Left in the Pieces Karofsky transfers to Dalton Academy.

5 Times Blaine was Slushied WISOTT

News Cycle The 24-hour news cycle doesn't allow time for grief.

I Don't Know How This Started, So I Won't Know When It's Done Kurt can't remember where he's been for the last three weeks. There's probably a good reason for that.

Just a Little Late Blaine would help Kurt, if he could just figure out how.

Nobody’s Business Finn calls Kurt in the middle of the night.

Earning the Right to My Silence There’s a line you don’t cross, even when you’re the one putting people in their place.

Don’t Let the Door Hit You on the Way Out Kurt just walked into a door. Really. Why won’t anyone believe him?

Baby, It’s Cold Outside (but not cold enough to wear that) Blaine's favorite party of the year is the annual ugly Christmas sweater party.

Tweety Kurt and Finn aren't allowed to have pets.

Manning Up "That's not a closeted guy hitting on you. That's sexual harassment."

The Way We Communicate Ten unconnected drabbles based on the random song meme that’s been going around.

The Boys All Love To Stare In which Kurt realizes that Blaine has a cheerleader fetish.

Sparkle Kurt has the perfect plan to get back at Principal Figgins for telling him what not to wear.

------------------------------------------------

Criminal Minds Fic

Checkmate AU of Memorium, featuring 4-year-old Reid.

The Forgetting Curve Spencer Reid has an eidetic memory. That doesn’t mean he remembers everything.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

#OnThisDay in 1934, public enemy no. 1, John Dillinger, was gunned down by federal agents as he exited Chicago’s Biograph Theatre where he’d gone to see his favorite actress, Myrna Loy in MANHATTAN MELODRAMA.

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Myrna Loy - The Queen of Hollywood

Myrna Loy (born Myrna Adele Williams in Helena, Montana on August 2, 1905 ) was an American actress who reigned as one of America’s leading movie stars in the 1930s and the 1940s. Millions of fans idolized her as ‘the perfect wife,’ a paragon of charm, sophistication and intelligence, earning her the title as "The Queen of Hollywood."

Of Welsh, Scottish, and Swedish ancestry, Loy moved to Culver City in her early teens. She first attended the exclusive Westlake School for Girls. When her teachers objected to her extracurricular participation in theater, her mother enrolled her in Venice High School.

To help the family, she wroked at Grauman's Egyptian Theatre, where she performed in prologues, musical sequences that served as preliminary entertainment before the feature film. This led to work as an extra in Hollywood productions in 1925 and then a contract with Warner Bros. in 1926.

With the advent of sound films, she then became associated with musicals, and when they began to lose popularity, her career slumped. In 1934, after Loy's move to MGM, John Dillinger was shot to death after leaving a screening of her film Manhattan Melodrama (1934). She received widespread publicity, with some newspapers reporting that she had been Dillinger's favorite actress.

Loy gained further fame from the box office hit, The Thin Man (1934), which spawned five sequels. This marked a turning point in her career, and she was cast in more important pictures and became one of Hollywood's busiest and highest-paid actresses,

With the outbreak of World War II, Loy focused on the war effort, becoming an active member of the Hollywood Chapter of 'Bundles for Bluejackets,' helping run a Naval Auxiliary Canteen, going on fundraising tours, and volunteering for the Red Cross.

In the coming decades, she continued acting alongside her activism work. She organized opposition to the House Unamerican Activities Committee in Hollywood through radio broadcasts and petitions, worked with the federal government, and served in UNESCO.

In 1975, Loy was diagnosed with breast cancer and underwent two mastectomies. She kept her diagnosis and subsequent treatment from the public. This resulted in her progressive retirement from acting; her last film performance was in 1980 and her last acting role on TV in 1982.

In failing health, Loy died at age 88 in a Manhattan hospital during surgery following a long, unspecified illness.

Legacy:

Received an Honorary Academy Award in 1991 in recognition of her life's work both onscreen and off

Bears the likeness of the 7-foot statue outside Venice High School, titled 'Inspiration," created in 1922 and has since become a symbol of the school and the community

Has a building named after her at Sony Pictures Studios, formerly MGM Studios, built in 1935

Named Queen of the Movies in a 1936 national poll by New York Daily News

Honored with a block in the forecourt of Grauman's Chinese Theatre in 1936

Listed by the Motion Picture Herald as one of America’s top-10 box office draws in 1937 and 1938

Served as the full-time assistant to the director of military and naval welfare for the Red Cross from 1941 to 1945

Became a member-at-large of the U.S. National Commission for UNESCO from 1949 to 1954, the first Hollywood celebrity to do so

Has been the namesake of Venice High School's annual speech and drama awards, the 'Myrnas' since 1953

Served as Co-Chair of the Advisory Council of the National Committee against Discrimination in Housing from 1961 to 1962

Became a founding board member of The American Place Theatre in 1963

Commemorated with a cast of her handprint and her signature in front of Theatre 80, on St. Mark's Place in New York City in 1971

Appeared in John Springer's "Legendary Ladies" series at The Town Hall in 1973

Presented with the 1979 Career Achievement Award by the National Board Review

Honored by the Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards in 1983 with the Career Achievement Award

Published an autobiography, Myrna Loy: Being and Becoming, in 1987

Was the winner of the 1988 Kennedy Center Honors

Honored by the Steel Pole Bath Tub with a song on their 1991 album Tulip that is both named after Loy and samples dialogue from one her film, The Thin Man Goes Home (1945).

Named by The Guardian named her one of the best actors never to have received an Academy Award nomination in 1991

Has been the namesake for The Myrna Loy Center for the Performing and Media Arts in downtown Helena since 1991

Honored as Turner Classic Movies Star of the Month for December 2016

Has a song named after her in Josh Ritter's 2017 album Gathering

Has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6685 Hollywood Blvd for motion picture

#Myrna Loy#The Queen of Hollywood#The Queen of Movies#Silent Films#Silent Era#Silent Film Stars#Golden Age of Hollywood#Classic Hollywood#Film Classics#Old Hollywood#Vintage Hollywood#Hollywood#Movie Star#Hollywood Walk of Fame#Walk of Fame#Movie Legends#hollywood legend#movie stars#1900s#28 Hollywood Legends Born in the 1900s

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remembering a childhood in the South Bronx.

As an aspiring actor, Pacino, seen here in 1972, would practice Shakespeare monologues while wandering the city streets.Photograph by Jerry Schatzberg / Trunk Archive

By Al Pacino August 26, 2024

My mother began taking me to the movies when I was a little boy of three or four. She worked at factory and other menial jobs during the day, and when she came home I was the only company she had. Afterward, I’d go through the characters in my head and bring them to life, one by one, in our apartment.

The movies were a place where my single mother could hide in the dark and not have to share her Sonny Boy with anyone else. That was her nickname for me. She had picked it up from the popular song by Al Jolson, which she often sang to me.

When I was born, in 1940, my father, Salvatore Pacino, was all of eighteen, and my mother, Rose Gerardi Pacino, was just a few years older. Suffice it to say that they were young parents, even for the time. I probably hadn’t even turned two when they split up. My mother and I lived in a series of furnished rooms in Harlem and then moved into her parents’ apartment, in the South Bronx. We hardly got any financial support from my father. Eventually, we were allotted five dollars a month by a court, just enough to cover our expenses at my grandparents’ place.

The earliest memory I have of being with both my parents is of watching a movie with my mother in the balcony of the Dover Theatre when I was around four. It was some sort of melodrama for adults, and my mother was transfixed. My attention wandered, and I looked down from the balcony. I saw a man walking around below, looking for something. He was wearing the dress uniform of an M.P.—my father served as a military-police soldier during the Second World War. He must have seemed familiar, because I instinctively shouted out, “Dada!” My mother shushed me. I shouted for him again: “Dada!” She kept whispering, “Shh—quiet!” She didn’t want him to find her.

He did, though. When the film was over, I remember the three of us walking down a dark street, the Dover marquee receding behind us. Each parent held one of my hands. Out of my right eye, I saw a holster on my father’s waist, a huge gun with a pearl-white handle sticking out of it. Years later, I played a cop in the film “Heat,” and my character carried a gun with a handle like that. Even as a child, I understood: That’s dangerous. And then my father was gone, off to the war. He eventually came back, but not to us.

My mother’s parents lived in a six‐story tenement on Bryant Avenue, in a three-room apartment on the top floor, where the rents were cheapest. Sometimes we would have as many as six or seven people living there at once. I slept between my grandparents or in a daybed in the living room, where I never knew who might end up camped out next to me—a relative passing through town, maybe my mother’s brother, back from his own stint in the war. He had been in the Pacific and would take wooden matchsticks and put them in his ears to drown out the explosions he couldn’t stop hearing.

My mother’s father was born Vincenzo Giovanni Gerardi, and he came from an old Sicilian town whose name, I would later learn, was Corleone. When he was four years old, he came to America, possibly illegally, where he became James Gerardi. By then, he had already lost his mother; his father, who was a bit of a dictator, had remarried and moved with his children and new wife to Harlem. My grandfather didn’t get along with his stepmother, so at nine he quit school and ran away to work on a coal truck. He didn’t come back until he was fifteen. He wandered around upper Manhattan and the Bronx—this was in the early nineteen-hundreds, when it was still largely farmland—doing apprentice jobs or working in the fields. He was the first real father figure I had.

When I was six, I came home from my first day of school and found him shaving in our bathroom. He was in front of the mirror, in a BVD shirt with his suspenders down at his sides. I was standing in the open doorway.

“Granddad, this kid in school did a very bad thing. So I went and told the teacher, and she punished that kid.”

Without missing a stroke, my grandfather said, “So you’re a rat, huh?” It was a casual observation, as if he were saying, “You like the piano? I didn’t know that.” His words hit me right in the solar plexus. I never ratted on anybody in my life again. (Although right now, as I write this, I guess I’m ratting on myself.)

His wife—my grandmother Kate—had blond hair and blue eyes, like Mae West, which was a rarity among Italians. We were the only Italians in our neighborhood, and she was known for her kitchen. When I’d be going out the door, she would stop me with a wet cloth, which always seemed to be in one of her hands, to say, “Wipe the gravy off your face. People will think you’re Italian.” America had just spent four years fighting Italy, and though many Italian Americans had gone overseas to help, others were labelled enemy aliens and put in internment camps. There was still a stigma against us.

Our little stretch between Longfellow Avenue and Bryant Avenue, from 171st Street up to 174th Street, was a mixture of nationalities and ethnicities. In the summertime, when we went on the roof of our tenement to cool off because there was no air-conditioning, you’d hear all kinds of languages and dialects. The farther north you went, the more prosperous the families were. We were not prosperous. We were getting by. My grandfather was a plasterer who worked during the week. Plasterers were highly sought after at the time. He had developed an expertise and was appreciated for what he did. He built the wall that separated our alleyway from the alleyway of the building next door for our landlord, who loved it so much that he kept our family’s rent at thirty-eight dollars and eighty cents a month for as long as we lived there.

I was an only child, and until I was six I wasn’t allowed out of the tenement by myself—the neighborhood was somewhat unsafe. My only companions, aside from my grandparents, my mother, and a little dog named Trixie, were the characters I brought to life from the movies. I had a little silent routine I did for my relatives from “The Lost Weekend”—starring Ray Milland as a self‐destructive alcoholic—in which I pretended to ransack an apartment, looking for booze. The grownups seemed to find it amusing. Even at five years old, I would think, What are they laughing at? This man is fighting for his life.

My mother was a beautiful woman, but she was emotionally fragile. She would occasionally visit a psychiatrist when Granddad had the money to pay for her sessions. I wasn’t aware that my mother was having problems until one day when I was six years old and getting ready to go out and play. I was sitting in a chair in the kitchen while my mother laced up my shoes and put a sweater on me to keep me warm, and I noticed that she was crying. I wondered what the matter was, but I didn’t know how to ask. She was kissing me all over, and right before I left she gave me a great big hug. It was unusual, but I was eager to get downstairs and meet up with the other kids, and I gave it no more thought.

We had been outside for about an hour when we saw a commotion in the street. People were running toward my grandparents’ tenement. Someone said to me, “I think it’s your mother.” I didn’t believe it, but I started running with them. There was an ambulance in front of the building, and there, coming out the front doors, carried on a stretcher, was my mother. She had attempted suicide.

This was not explained to me; I had to piece together what had happened. I knew that she had left a note and that she was sent to recover at Bellevue Hospital. That period is kind of a blank to me, but I do remember sitting around the kitchen table, where the grownups were discussing what to do. Years later, I made the film “Dog Day Afternoon,” and one of its final images, showing the actor John Cazale’s character, already dead, being taken away on a stretcher, made me think of the moment I saw my mother brought out to that ambulance. But I don’t think she wanted to die then, not yet. She came back to our household alive, and I went out into the streets.

As a kid, I ran with a crew that included my three best friends: Cliffy, Bruce, and Petey. We were on the prowl, hungry for life. To this day, one of my favorite memories is coming down the stairs and out onto the street in front of my tenement building on a bright Saturday morning in the spring. I couldn’t have been more than ten years old. I remember looking down the block, and there was Bruce, about fifty yards away. He turned and smiled, and I smiled, too, because we knew the day was full of potential.

Every few blocks were vacant lots where victory gardens had been planted at the height of the war. By then, they were wrecked and full of debris. Once in a while, when you looked down at the sidewalk along the lots, you’d see a blade of grass growing up out of the concrete. That’s what my friend, the acting teacher Lee Strasberg, once called talent: a blade of grass growing up out of a block of concrete.

One winter day, I was skating on the ice over the Bronx River. We didn’t have ice skates, so I was wearing a pair of sneakers, doing pirouettes, showing off for my friend Jesus Diaz, who was standing at the shore. One moment I was laughing and he was cheering me on, then suddenly I broke through the surface and plunged into the freezing water below. Every time I tried to crawl out, the ice broke further and I kept falling back in. I think I would have drowned if it wasn’t for Jesus Diaz. He found a stick twice his size, spread himself out as far as he could from the shore, and pulled me to safety.

Another day, I was walking on top of a thin, iron fence, doing my tightrope dance. It had been raining all morning, and, sure enough, I slipped and fell, and the iron bar hit me directly between my legs. I was in such pain that I could hardly walk. An older guy saw me groaning in the street, picked me up, and carried me to my aunt Marie’s apartment. She was my mother’s younger sister, and she lived on the third floor in the same building as my grandparents. The Samaritan threw me on a bed and said, “Take care, man.”

It was customary for doctors to go to people’s houses in those days. While my family waited for Dr. Tanenbaum to come, I lay there on the bed, with my pants down around my ankles as the three women in my life—my mother, my aunt, and my grandmother—poked and prodded at my penis in a semi-panic. I thought, God, please take me now.

Our South Bronx neighborhood was full of characters. There was a guy in his late thirties or early forties who wore a suit and a collared shirt with a loose, tattered tie. He looked like he had gone to a Sunday service and got ashes spilled all over him. He would quietly walk the streets by himself; when he spoke, the only thing he said was “You don’t kill time—time kills you.” That was it. Our instincts told us he was different than we were, but we just accepted him. There was more privacy back then, a certain propriety and distance that people gave one another.

When Cliffy, Bruce, Petey, and I got a little older, eleven or twelve, we spent hours lying flat on our stomachs as we fished through sewer gratings for lost coins. This was not an idle pursuit—fifty cents was a game changer. On Saturday nights, we would see guys just a few years older than us who had started to date, taking girls out to the movies or on the subway, and we’d get up on the storefront roofs and pelt them with trash. Sometimes we’d split up a head of lettuce and toss it at them. A string bean thrown from twenty feet away could really sting.

In the summer, we opened up the hydrants, which made us heroes to all the young mothers who let their small children play in the water. We hitched ourselves to the backs of buses, jumped over turnstiles in the subway. If we wanted food, we’d steal it. We never paid for anything.

We played the old street games, like kick the can, stickball, and ring-a-levio, which involved splitting up into two teams. If you could stick one foot in the circle that was the other team’s jail and shout “Free all!,” your whole gang would get sprung. Kids were known to jump off buildings just to get a foot in that circle.

We were always either chasing someone or being chased. When we’d see cops, we’d yell out, “Hey, what’s a penny made out of?” And then we’d all answer, “Dirty copper!” The cops would yawn or laugh or take off after us, depending on their mood. But we all knew the neighborhood cop on our beat; he kept an eye on us. I don’t know how much violence he stopped, but we grew to love him, and he got a kick out of us. I always thought the guy had a crush on my mother. He’d ask me questions about her, and even at age eleven I sort of knew why.

There were a few others in our little gang—Jesus Diaz, Bibby, Johnny Rivera, Smoky, Salty, and Kenny Lipper, who would go on to become the deputy mayor of New York City under Ed Koch. (I later did a film called “City Hall,” directed by Harold Becker, which was based on his experience.) But Cliffy, Bruce, Petey, and me were the top bananas. They called me Sonny, and Pacchi, their nickname for “Pacino.” They also called me Pistachio, because I liked pistachio ice cream. If we had to choose someone as our leader, it would be Cliffy or Petey. Petey was a tough Irish kid. Cliffy was a true original. Even at thirteen, he was never without a copy of Dostoyevsky in his back pocket. He had talent. He had looks. And he had four older brothers who beat the shit out of him every day. He was full of trickery. You never had to ask him, “What are we going to do today?” He always had a scheme.

Often, when I looked down from my apartment window, I would see my friends—a pack of wild, pubescent wolves with sly smiles—looking up at me from the alley, calling out, “Come on down, Sonny Boy! We got something for ya!” One morning, Cliffy showed up with a huge German shepherd. He yelled up, “Hey, Sonny, wanna look at my dog? He’s my new friend, and his name is Hans!” He had got it from somewhere. Cliffy wasn’t known for taking dogs. Cars were more his thing. Once, he stole a garbage truck. He also used to burglarize houses—at a certain point, he could no longer go to New Jersey because he was wanted by the police there. He would tease me because I never did any of the drugs that he was into. He’d say, “Sonny doesn’t need drugs—he’s high on himself!”

There was one thing that divided me from the rest of the gang. My grandfather had instilled a love of sports in me: he was a lifelong baseball and boxing fan. He grew up rooting for the New York Yankees before they were even the Yankees—as a poor kid, he would watch their games through holes in the fence at Hilltop Park. Later, the Yankees got their own stadium, known as the House That Ruth Built, after Babe Ruth. That stadium is in the background of a scene in “Serpico”—shot by Sidney Lumet with such beauty—in which my character, Serpico, meets with a crew of corrupt cops. It was filmed the same day the actress Tuesday Weld and I broke up, and, if you notice the look on my face, you can tell I was pretty sad.

My grandfather would sometimes take me to baseball games, and we’d sit way up in the grandstand—the cheap seats. I didn’t think of myself as being disadvantaged—the more expensive box seats were just another block in the neighborhood, another tribe. The difference between Cliffy and me was that Cliffy would see those same box seats and want to go down there. If there was a line to get into a movie, he’d cut in front of someone and just go right in. It was like nobody existed but him.

I played baseball for the Police Athletic League team in my neighborhood. Sports were of no interest to Cliffy and the other guys, so it was almost like I lived two lives: my life with the gang, and my life with my pal teammates. One day, as I was coming back from a game in a bad neighborhood, a group of four or five guys not much older than I was got the jump on me; they had knives and God knows what else, and they said, “Give us the glove.” They knew I had no money, and I knew I was losing my glove, which my grandfather had bought for me. I went home in tears. If only I’d had Cliffy, Petey, and Bruce with me. It wasn’t just comfortable for us to be together in our group—it was necessary.

At the edge of the Bronx River, about four blocks from our homes, sat the Dutch houses, or the Dutchies. Built by Dutch settlers, they were ancient buildings, now dilapidated but not quite abandoned. Herman Wouk wrote about them in his novel “City Boy,” describing the surrounding territory as an area of “odorous heaps.” When we felt really daring, we would venture out to those ruins, which were populated by wayward kids and runaways—Boonies, we called them, because they lived on Boone Avenue. Wild plants grew along the riverbanks, including bamboo that kids would cut down and carve into knives, bows, and arrows. The Boonies lived in shacks, and the lore was that they had poison on the ends of their homemade weapons.

One day, I was on Bryant Avenue and saw the rest of the gang limping back from the Dutchies, looking defeated. Cliffy was covered in blood. He noticed the expression on my face and shouted, “It’s not me! It’s Petey’s blood!” Behind him was Petey, blood gushing from his wrist. They had been making their way down a hill when Cliffy suddenly screamed, “Look out, there’s a Boony there!” He shouted out a name that was notorious in the area at the time. Even now I can’t bring myself to say it. Cliffy had only been kidding, but the other kids scrambled in every direction. Unfortunately, Petey stumbled and fell, landing hard on something sharp and jagged that sliced through his left wrist. The cut was so deep that it went all the way down to the nerves. It was horrible, all because of a dumb prank.

The doctors eventually stitched Petey up, but in a botched way, so he couldn’t move his hand correctly. Cliffy always blamed himself for what happened.

I’m taking a bath in my grandparents’ apartment when I hear a rumbling in the alleyway downstairs. From five stories below, the voices reach up to my bathroom window:

“Sonny!”

“Hey, Pacchi!”

“Sonn‐ayyyyyyyy! ”

These are my friends calling to me. But something is preventing me from leaping out of the tub, throwing on my clothes, and joining them. I don’t mean my conscience; I mean my mother. She is telling me I am not allowed. She says it’s late and tomorrow is a school day and any boys who come to shout in the alley at that time of night aren’t the sort of boys I should be spending my time with, and, anyway, the answer is no.

I hate her for this. These friends are everything in my life that means something to me. And then one day I’m fifty‐two, looking in the vanity mirror at my face, fat with shaving cream, wondering whom I should thank in an acceptance speech for an award I’m about to receive. I think back to that moment in the bath, and I realize that I’m still here because of my mother. Of course, that’s who I have to thank. She’s the one who parried me away from a path that led to delinquency and violence, to the heroin that eventually killed Petey, Cliffy, and Bruce. I lost all three that way. I was not exactly under strict surveillance, but my mother paid attention to where I was. I believe she saved my life.

Pacino’s nicknames as a kid included Sonny, Pacchi, and Pistachio, because he liked pistachio ice cream.Photograph courtesy the author / Mark Scarola

I was lucky that I had people who were looking out for me, even if I didn’t always appreciate it at the time. One of those people was my junior-high teacher Blanche Rothstein, who selected me to read passages from the Bible at our student assemblies. I didn’t come from a particularly religious family. My mother had sent me to catechism class, and I wore a little white suit for my first Holy Communion, and that was it. But when I read from the Book of Psalms in a big booming voice—“He that walketh uprightly, and worketh righteousness, and speaketh the truth in his heart”—I could feel how powerful the words were.

Soon I was performing in school plays like “The Melting Pot,” a pageant celebrating the many nations whose people had contributed to the greatness of America. I was there to represent Italy, along with a ten‐year‐old girl with dark hair and olive skin. Our class put on “The King and I,” and I was cast as Louis, the son of the heroine, Anna. I sang a song with the kid who played the young Prince of Siam, about being puzzled by how grownups behaved. I didn’t take acting very seriously at that point—it was just a way to get out my energy, and especially to get out of classes. But I somehow became the guy that you simply had to have in these school productions.

In eighth grade, we put on “Home Sweet Homicide,” and I was cast as a kid who helps his widowed mother solve a murder at the house next door. Before I went onstage, someone told me that both my parents were in the audience. It threw me off. To this day, I don’t want to know who’s in the audience on opening night.

Still, I felt at home onstage. I liked that people were paying attention to me. Right after the show, my mother and my father, who was now an accountant living in East Harlem with a new wife and child, took me out to Howard Johnson’s, and we all toasted my success. A feeling of warmth and belonging came over me. It was probably the first time in my entire life that I saw my parents talking to each other pleasantly, not arguing about anything. At one point, my father even touched my mother’s hand with his own—was he flirting with her? It all felt so easy and natural.

When I was fifteen, a troupe of actors, as if out of some bygone century, came to the Bronx’s old Elsmere Theatre, on Crotona Parkway, to put on a production of “The Seagull,” by Anton Chekhov. The ornate theatre seated more than fifteen hundred people, and an audience of about fifteen came to see the play. Two of those audience members were my friend Bruce and me.

I don’t know how much of the play I really understood, with all its unrequited romances and the tragic character of Konstantin, but I was riveted by the performances. I saw myself in the lives of those fictional characters.

From then on, I started carrying Chekhov’s works around with me, amazed at the idea that I could have access to his writing whenever I wanted. I had just got into the High School of Performing Arts in Manhattan, and so had Cliffy, who had also acted in middle school and was very good. In the mornings, we’d ride the train together from the Bronx and emerge at Forty‐second Street and Broadway. For the four blocks we walked up to P.A., we were mesmerized by the tourists and gawkers. One day, as we turned a corner, I saw Paul Newman, the movie star, walk by with someone, and I thought to myself, Wow, he’s a real person, with real friends he talks to when there are no cameras around.

On one train ride, Cliffy’s thoughts were focussed on the teacher of our voice-and-speech class. She was an intelligent and sophisticated woman whose claim to fame was that she had dated Marlon Brando. Cliffy said to me, “I’m going to feel her breasts.” From the way he said it, it was clear this was something he had been thinking about for a while. I said, “What?” He said, “Watch. You’ll see.”

The class began that morning as it normally did, with the teacher giving us our lesson in her deep, resonant voice. Before long, Cliffy got up. He said something to her, I don’t know what, and suddenly the two of them were tussling. Then Cliffy reached his arms around her from the back, turned her around to face the class, and there he was, behind her, with both hands on her breasts. He looked at me and smiled.

This was the act of someone with no propriety, no limitations, and no conscience. Most of the students were silent. I broke into laughter, as did a classmate named John. It was just an involuntary reaction to the shock of what Cliffy had done. I loved Cliffy, but I was genuinely horrified by this trespass. John and I got tossed out of the classroom for the day, which I spent in the principal’s office until my mother arrived and apologized on my behalf. Cliffy was thrown out of school, and then thrown out of his house. After that, he disappeared from my life for a while.

One afternoon, I went out for lunch at a coffee shop near school, and there, taking orders behind the counter, was one of the actors from the performance of “The Seagull” that I had seen in the Bronx. I was a little bit starstruck, and I said, “I saw you the other night! Oh, my God, you were so great!” I couldn’t believe I was talking to him. He seemed pleased to have a doting fan.

By day, he wore a waiter’s outfit, and by night he performed in a play. One was a job, and the other was his artistic calling. He was an actor moving from role to role and theatre to theatre, like actors have done for hundreds of years. This was how I came to understand acting as a profession. You did whatever work paid you so you could keep acting, and, if you could find a way to actually get paid for acting someday, all the better.

Just before I turned sixteen, my mother started seeing someone new. She would say to me, “You know, we may live in Texas or Florida,” meaning her and her husband‐to‐be. I was relieved in a way, but I didn’t see how I belonged in this arrangement. This man was around fifty; I thought, This guy probably doesn’t want me around, plus I wanted the apartment to myself. By now, my grandparents had moved farther uptown, to an apartment on 233rd Street, so it was just me and my mother living on Bryant Avenue.

Then their engagement was abruptly cancelled. The guy didn’t even have the decency to tell her in person. He sent her a telegram saying that he couldn’t go through with it. When she received it, she was sitting at our kitchen table, and I was leaning against the arch of our hallway. Four feet away was the door, which I was always aiming for.

When she told me the engagement was off, I actually said to her, “I knew that was too good to be true.” It was one of the most terrible things I ever said to her. How could I have? It bothered me that she was hurt. But it also bothered me that she wasn’t leaving.

My mother did not react well to the breakup. She was diagnosed with what the doctors called anxiety neurosis. She needed electroshock treatment and barbiturates. These were costly things that we didn’t have the money for. She encouraged me to quit school and go to work.

I stayed in school until I was sixteen, when I was legally old enough to quit. I was O.K. with it—I had never seen school as my place. At one point, P.A. had picked me to represent the student body in a photo accompanying an article in the New York Herald Tribune. At the last minute, I was replaced with another student, who was a dancer. She was tall and had red hair; I had my dark complexion and my Italian name. It crossed my mind that she represented a more mainstream version of beauty than I did; you didn’t see people like me in detergent commercials or on soap operas. But I didn’t think the school was being biased. Performing Arts was just trying to draw in more students, and this was the status quo at the time.

After I left, I went through various jobs, all short-lived. I spent a summer as a bicycle messenger. At seventeen, I had a successful stretch working for the American Jewish Committee and their magazine, Commentary. I said to the woman who interviewed me for the job, “I love sitting around offices. I love the sound of typewriters. I love switchboards.” I’m sure she saw right through my bullshit, but she hired me anyway. The people who worked there—people like Susan Sontag and Norman Podhoretz—were intellectual heavyweights, and, though they were very welcoming toward me, I never felt like I fit in. But, at an office party with a drink in my hand, I’d be able to talk to almost anyone.

At eighteen, I was nursing a fifteen‐cent beer at Martin’s Bar and Grill, on Twenty‐third Street and Sixth Avenue in Manhattan. It was a place where I’d sometimes go and have ketchup sandwiches: two saltine crackers with ketchup in the middle. The bar had a big picture window that looked across Sixth Avenue, where I could see the Herbert Berghof Studio, an acting school I was trying to get into. A friend had told me about the school, and a great teacher there named Charlie Laughton. I said, “The actor Charles Laughton?” He said, “No, no, different guy—his name is Charlie Laughton. He teaches sensory work.” I thought, I’m lost already.

I was pondering this when suddenly the bartender, who went by Cookie, got an angry look on his face. He got out from behind the bar and banged on the door of the men’s room. The next thing you know, he had hold of two scruffy young women by the collars of their leather jackets, and he was throwing them out. Cookie returned to his post at the bar, where seven or eight working stiffs were lined up, and the two women stood in front of that big, wide window in broad daylight and began passionately kissing. They were doing it so that everybody in the bar could see them. There was a rift I was witnessing right there between two separate worlds: the brazen young women outside who were the very essence of liberation, and the guys at the bar who were shell‐shocked by something they’d never seen in their lives. The sixties were coming.

I was introduced to Charlie Laughton at that same bar sometime later. The moment I set eyes on him, I thought, This guy is my kind of guy. He was about ten years older than me. He loved the poetry of William Carlos Williams, who came from Paterson, New Jersey, like he did. I enrolled at the Herbert Berghof Studio. I had no money, so I cleaned the hallways and the rooms where they had dance classes, and they gave me a scholarship.

By then, my mother had moved up to 233rd Street to live with her parents, and I had our apartment to myself. The rent was still thirty-eight dollars and eighty cents a month. But I had lost the Commentary job and I was broke. Charlie, who was married to an actress named Penny Allen, was broke, too, so he and I worked together as moving men. We moved office furniture and a lot of books. Our friend Matt Clark, who was in Charlie’s acting class, ran the moving operation. How does an actor prepare? He carries a refrigerator up the stairs.

In my free time, I became a voracious reader. Charlie turned me on to many novelists and poets I didn’t know. He would suggest various writers to check out and places to go, like the Forty‐second Street library for warmth and the Automat for sustenance. At the Automat, I could make a single cup of coffee last all morning, sitting there for five hours while I read my little books by the great authors. I would be reading “A Moveable Feast” and thinking, I don’t want to finish the pages, I like it here too much.

If the hour was late and you heard someone in your alleyway with a bombastic voice shouting iambic pentameter into the night, that was probably me, training myself on the famous Shakespeare soliloquies. I would bellow out monologues as I rambled through the streets of Manhattan. I’d do it by the factories, at the edges of town, places where no one was around. On those side streets, I didn’t need anyone’s permission to play Prospero, Falstaff, Shylock, or Macbeth. I grew to love Hamlet’s rogue-and-peasant-slave monologue so much that I started to use it at auditions. I would say to the director, “I know you have your pages that you want me to perform, but I have a little something that I’ve already prepared, if you don’t mind.” Usually they would give me a look that told me they were already finished with me.

Another young actor in Charlie’s class was a guy by the name of Martin Sheen. In one session, Marty did a monologue from “The Iceman Cometh,” and he blew the roof off. He was the next James Dean, as far as I was concerned. I got to be friends with him, and one day he said, “You know what my real name is, don’t you? Estevez.” He was half Spanish, and he came from Ohio, where he had a tough upbringing. He was one of ten kids in a working‐class family that was always struggling for money. He had tenacity and grit, and I could tell he was one of the best people I’d ever know.

Marty moved in with me in the South Bronx so we could split the rent. We worked together at the Living Theatre in Greenwich Village, where we cleaned toilets and laid down rugs for sets. The Living Theatre had been founded by Judith Malina and Julian Beck, two actors who started it in their living room in the nineteen-forties and eventually moved it to Fourteenth Street and Sixth Avenue. They did the kind of shows that made you go home afterward and lock yourself in your room and cry for two days, staring at the ceiling. They helped forge Off Broadway theatre, whose success paved the way for Off Off Broadway, which made possible some of the shows I was doing Off Off Off Off Broadway. When I appeared in “Hello Out There,” by William Saroyan, we would put on sixteen performances a week at Caffe Cino on Cornelia Street, and then we’d pass the hat to what little audience was there, hoping to come away with a few dollars for a meal. It was our Paris in the early nineteen-hundreds, our Berlin in the nineteen-twenties. That was the spirit of the scene.

The author, far right, with family in the South Bronx, including his grandfather, James Gerardi, far left, and his mother, Rose Gerardi Pacino, second from right.Photograph courtesy the author / Mark Scarola

Sometimes one of Marty’s brothers would stay over at the Bronx apartment, or this guy Sal Russo from acting class who was going with a woman named Sandra. Her best friend was a musician with long dark hair and piercing eyes named Joan Baez, who would occasionally drop in, sit cross‐legged in a corner, and play her guitar. She hadn’t linked up with Bob Dylan yet, but we knew Joan was going places. I don’t believe she and I even exchanged hellos.

I heard that Cliffy was back in the neighborhood again. Both he and Bruce had enlisted in the Army. Bruce made it as far as his induction ceremony, when he got second thoughts and threatened to jump out a window, so they let him go. Cliffy, on the other hand, served for a few months, but of course he got in trouble and was thrown into the brig before being discharged. I knew there was no risk that I’d be drafted myself, because I was supporting my mother. Anyway, could you imagine me, that boy I was, going around saying, “Hup‐two‐three‐four”? I can do it in a play.

Cliffy had come out of the Army in even worse shape than he went in. He was on the needle and doing and saying all kinds of crazy stuff. He said he had been in the same platoon as Elvis Presley, and it turned out he actually had. He said he went to Canada, got a Catholic girl pregnant, and converted from Judaism so that he could marry her. Every time he stopped by my apartment, he would go into the bathroom to shoot up, sometimes alone and sometimes in the company of other people he’d brought. Eventually I had to tell Cliffy he couldn’t come around anymore.

It was no surprise to anyone when he overdosed and died. It made me think of a story that he had told me. When he was in the brig, Cliffy said, he was watched by a guard, a Southerner who carried a .45 pistol. The guard would hold his pistol up just so and start saying ominous things about “the Jews.” In his Southern drawl, he would tell Cliffy, who was still Jewish at the time, “You know, I could just blow your head off and tell people you tried to escape. Would that be something to do?” He kept repeating it, day after day, until Cliffy finally turned to the guy and said, “Hey, man, you know what? You better kill me. Because if you don’t, when I get out of here, I’m gonna come back and kill you.” Cliffy may not have been the toughest guy I ever met, but he certainly was the most fearless.

It was Bruce who told me that my mother had overdosed. I came back to my apartment late one night to find a note on my door, saying that he had an urgent message for me. I went to his place; he lived with his parents in the building next door, and he took me into their kitchen and said, “Your mom’s in a lot of trouble. She’s really sick. You better go, man.” I jumped in a cab to 233rd Street.

Arriving at the building, I looked up and saw the lights on in my grandparents’ apartment. I went up the stairs, walked in the door, and there were my grandmother and grandfather, their eyes wet with tears. I was too late. My mother had died like Tennessee Williams would, choking while taking her own pills.

Some people thought that she had committed suicide, as she had tried to almost fifteen years earlier. But she left no note this time, nothing. She was just gone. That’s why I have always kept a question mark next to her death.

I’ll never forget the image of my grandfather the next morning, sitting in a folding chair in the middle of the room, nothing around him, crouched over with his head in his hands, almost between his legs. He just kept banging a foot on the floor. I’d never seen him that way. He didn’t speak, but I knew what he was saying. No.

I thought that maybe somehow I could have stopped it from happening. Therapy, financial security—these things could have helped my mother. I had known that one day I was going to be able to supply her with all that and more. It sounds like an Odets play, but it’s true.

here. Come with me.” I was stunned. But I didn’t go. I had moved out of the Bronx by that time and found a low‐rent rooming house in Chelsea for eight bucks a week. Something was driving me. I had to make it, because that was the only way I would survive this world. ♦

This is drawn from “Sonny Boy: A Memoir.”Published in the print edition of the September 2, 2024, issue, with the headline “Early Scenes.”

6 notes

·

View notes