#magnum pi anniversary

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

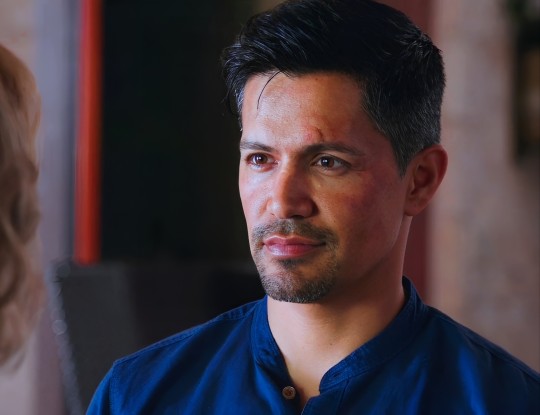

TV SHOWS' ANNIVERSARY 🩷

MAGNUM P.I. (2018 - 2024)

SIX YEARS OF MAGNUM P.I. 🤍

#magnum pi#thomas magnum#juliet higgins#rick wright#theodore calvin#sebastian nuzo#zeus and appollo#miggy#miggyedit#higgins x magnum#magnum x higgins#magnumpiedit#magnum pi series#magnum pi anniversary#magnum pi season 1#1x01#i saw the sun rise#tv shows anniversary

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

GIFS AND EDITS MASTERLIST POST 6

Previous masterlists: one || two || three || four || five

Mission Impossible

Ethan shooting Luther in Fallout: part 1 || part 2

Luther holding Ethan back + Benji winning the bet: part 1 || part 2 || part 3

Ethan and Luther gif in the boat

Boys and trust

Scared Ethan

Top Gun/Top Gun Maverick

July 29th anniversary gifset

Dogfight football beach scene: part 1 || part 2 || part 3

Rock of Ages

"Pour some sugar on me" by Def Leppard gifset: part 1 || part 2 || part 3 || part 4

Jack Reacher 2012

Jack gifset

Jack Reacher: Never Go Back

Jack and Susan at the motel: part 1 || part 2

Jack holding Sam

Reacher on Prime

Dancing little imp: part 1 || part 2

Shirtless Jack: part 1 || part 2

Jack and the medal

Reacher season 2 trailer gifs

Hit the road Jack video edit

OG Magnum PI

Scars of the past cover edit

Your softness is your strength cover edit

Squad goals

Exasperated Thomas

Detached

Delirium

Forever in time

Sleepy time Tom

Thomas and Rick edit (1x01)

Every sunrise

Thomas/TC edit

Port side

Troubled birds OG MPI characters edit

Troubled birds OG MPI edit

Did you see the sunrise video

Morning swim + comfort cover edit

Heads and aches

Limbo

The boys

Thomas and Jack AU edit

Thomas 6x09 edits

A boy

Klutzy Thomas

Persist and prevail cover edit

Smiley boy

Thomas and TC edit (John Denver - Looking for space)

Criminal Minds

Hotch gifs (1x08)

MacGyver 2016

Fluke AU edit (MacGyver 2016 and CSI)

Imp Mac gif

WK 3x08 edit 1

WK 3x08 edit 2

Mac and Jack edit (first version of the show)

Drugged and disoriented Mac video 2x04

Video 1x03 - Mac and Jack at the cemetery

Jack angsty edit

For your eyes only (AU) edits

Winged Mac fic edit

"Sorry" by Daughtry, Mac and Jack edit

Monte Walsh 2003

Anniversary gifset

Smallville

AC being hit with a dart

Born on the Fourth of July

Ron being carried by his father

Reacher on Prime

Boy getting undressed: part 1 || part 2

Reacher in every episode of season 1

Hawaii Five 0 (2010)

Steve and Freddie gifs - 3x20: part 1 || part 2

Fast X

Boy in Rio

TMNT 2003

The turtles and their weapons

Leo and flashback

Missing scene to 2x16 fic cover

Parallels

Thomas and Greg parallels (OG MPI and Black Sheep Squadron)

Jesse Stone and Thomas Magnum parallels (OG MPI and Jesse Stone: Thin Ice)

Jesse Stone and Thomas Magnum parallels, "Bedside vigils" (OG Magnum PI and Jesse Stone: Sea Change)

Shower parallels (Smalville and Reacher on Prime)

Parallels Bill Cage and Nick Morton

Cuffs parallels

Mission Impossible and MacGyver 2016 parallels: part 1 || part 2

Miscellaneous

Hugs (H50, MacGyver 2016, The Old Guard)

Fanfic writers appreciation day edit

Ari Levinson and Clay Appuzzo edits: edit 1 || edit 2

Mirror gifset + bonus gif

Ella Thomas birthday edit

Donnie Wahlberg birthday edit

#masterlist#gifs#edits#my gifs#my edits#og magnum pi#criminal minds#macgyver 2016#parallels#miscellaneous#rock of ages#mission impossible#smallville#reacher on prime#jesse stone#black sheep squadron#monte walsh 2003#top gun#top gun 1986#tom cruise#edge of tomorrow#jack reacher: never go back#american made#born on the fourth of july

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Imitation of Life

We watched an Elvis tribute show last night commemorating the 50th anniversary of a TV special. (Yes they will celebrate anything to get ratings) What struck my wife and I was how poor of a rendition most of the 'guest' performers executed. (especially with the lemon colored suit and the tattoos under and above his eyes. Elvis would have been proud) In my mind, and that is all that really matters, the best tribute would have been just to rerun the original special in its entirety. Not only would it have been better, but I would suspect the production costs would have been much lower, causing the profits to go way up. (Did I mention I was in business for a long time?) No one does an Elvis song as well as Elvis, so give it a rest. That means you guys in Vegas. Old Elvis, young Elvis, Asian Elvis, Black Elvis, and the Elvis that marries people. If you don't believe the tribute was lame, watch it, and tell me that Priscilla and Lisa-Marie seemed less than enthusiastic about their role in this debacle. The only interesting part was watching Mac Davis, who not only knew Elvis, but wrote some of his songs. Old guys rule!

This got me to thinking of some of the failed tributes, and remakes, I have had the misfortune of witnessing over the years. While technology has made some better (King Kong. The Peter Jackson one, not the 70's one with Jessica Lange) by and large the attempts to 'improve' on greatness generally falls short. I offer these examples.

- Ben Hur. While the 50's classic was in itself a remake (there I go educating you people again) the recent version was brutal. The actual movie was about half of the running time, and I believe what they cut out were the good parts. And the funny parts. You don't think there was humor? Rewatch the gay come on scene between Stephen Boyd and Charlton Heston. What makes it humorous was the fact that old Chuck was completely unaware of what was happening. Even the symbolism of handling each other's spears. (too deep? That's what he said)

- the 1990's tribute to Freddie Mercury. I still have nightmares of Liza Minelli singing 'We are the Champions'. Why? Why? Why? My testicles retreated into my body and did not resurface for three years.

- Magnum PI. Apparently in the last several years Higgins had a sex change operation. Who thought of this one? Not that there is anything wrong with that.

- They have remade Tarzan 463 times. The only things that get better are the apes.

- What Women Want. This one is a puzzler. They took a mediocre movie and remade it. It is like walking into a door, then saying 'that was fun. I'll try it with a different door'.

I get why Hollywood and the music industry does this. They want to engage a new generation, and they have also run out of original ideas. Remakes are seldom a good idea. Nothing wrong with replacing actors in sequels. (If they didn't we would currently have an 88 year old James Bond, and when he interacted with his colleagues it would look like a scene from Weekend at Bernie's).

There are some people/songs/movies that need to be left alone. Elvis, Fonzie, Mork, Stairway to Heaven, Star Wars, Queen, Aerosmith, Led Zepplin to name a few. Some songs were great not just because of the song, but the singer/arrangement. If the next generation wants to make a name for themselves, make a name for themselves. Don't ride the coat tails of previous greatness.

I'm just saying...

The opinions expressed in this blog, although they came out of my head, are undoubtedly shared by those of you not found clinically insane.

THOUGHT OF THE WEEK: New Coke disappeared quickly for a reason.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I been snooping through your blog. What would you say are your favorite characters from the NBC shows and CBS shows you listed on your anniversary post/survey? Also belated happy anniversary! - PSC gift exchange anon

Hi again! Ohhh that's a hard question, I have a lot of favourites. I was not sure if you meant everything for CBS, so I will just list anything I can think of 😅

Chicago Fire: The whole cast literally? Okay just to name a few: Sylvie Brett, Kelly Severide, Violet Mikami, Blake Gallo, Joe Cruz

Chicago PD: Kim Burgess, Kevin Atwater, Adam Ruzek

Chicago Med: Ethan Choi, Will Halstead, Maggie Lockwood

FBI: Once again, who isn't? But OA, Maggie, Jubal, Scola, Tiffany

FBI Most Wanted: Barnes, Hana, Crosby, Ortiz

Hawaii-Five-0: Chin Ho Kelly, Kono, Danny, Junior, Tani

SEAL Team: Literally the whole Bravo squad and also Lisa and Blackburn and the most important character of the show Cerberus 😂

Blue Bloods: Danny Reagan, Maria Baez, Eddie Janko

Magnum PI: Magnum, Higgins, TC, Rick, Gordon, Kumu, Lia, yeah basicly everyone 😅

I hope it was not too much, I am really excited to see what you will create and I will be really happy with anything!! 💚💚

1 note

·

View note

Photo

https://www.watchesandculture.org/forum/en/tom-selleck-never-without-my-rolex-gmt-master-pepsi/ May 2018 was the 30th anniversary of the end of the Magnum PI TV series, which ran from 1980 to 1988 and was notable for his @ferrari 308 GTS, a forerunner of the current top car: The Ferrari 812 GTS ‘Superfast’ 800 BHP V12 Naturally Aspirated Internal Combustion engine: https://www.ferrari.com/en-EN/auto/812-gts And his iconic @rolex GMT-Master ‘Pepsi’ 1675, the forerunner of the current white Gold ‘Pepsi’ model 126719BLRO: https://assets.rolex.com/watches/gmt-master-ii/m126719blro-0003.pdf And the stainless steel version, like the 1675: https://assets.rolex.com/watches/gmt-master-ii/m126710blro-0002.pdf https://www.instagram.com/p/CecObc8j-tE/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

Rufio and the Cooolkidz releases new singles ʻTrap Alphabet,' 'Days of the Week,' and 'Months of the Year.'

The songwriter and producer of children's hip-hop music known as Rufio and the Cooolkidz has released his latest official singles, ʻTrap Alphabet,', “Days of the Week” and “Months of the Year.” All three have been released with corresponding official music videos and proudly published as independent releases on Honolulu's Beautiful Emergence Records independent music label. Fun, vibrant, educational, and shining with aloha, “Days of the Week” introduces Rufio and the Cooolkidz as one of the most intriguing artists of the year so far.

GeorgiaRufio and the Cooolkidz are Jabez and Joseph Aurelio. Jabez cites as main artistic influences Jack Johnson, Blazer Fresh (and GoNoodle in general), Jack Hartmann, Mr. Rogers, Harry Kindergarten Music, Super Simple Songs, and KidsTV123, while Joe mentions Medasin, Carmack, and Kota the Friend. Their particular brand of children's music falls into the pop, hip hop, and electronic RnB categories, but the duo describe their music themselves as simply fun, chill, and educational.With an emphasis on bringing something useful to the home and classroom alike, “Days of the Week” and “Months of the Year” by Rufio and the Cooolkidz are sure to appeal to kids 2-7 everywhere, and then some.

Speaking of his motives for making original music, Jabez writes, “I am inspired by music’s ability to transcend the confinements of speech in the developing minds of young children, and I want to fuse my love for educating children with my love for creating and performing. I want to make learning fun through positive, entertaining/educational videos.”

Jabez, who lives on Oahu, has been playing ukulele since high school. Joe, a Kauaʻi native, has been playing music since childhood. Together, they are the co-creators of the CooolKidz YouTube channel.

Jabez has performed in front of sold-out audiences on the Kennedy Theater main stage, received and accepted the AADA scholarship offer to attend their prestigious program for a year, but declined their second-year proposition and chose to return to his family in Hawaiʻi. He has played roles in Hawaii 5-0 and Magnum PI, the Lifetime Channel’s “Anniversary Nightmare,” and has even played a war hero in the independent docudrama movie, “Go For Broke.”

Joe has made a name for himself as a DJ on Oahu with residency at various clubs and promotion companies playing for thousands at local venues and concerts. He has been composing, recording, performing and producing original music since 2011.“

“Trap Alphabet,” “Days of the Week” and “Months of the Year” by Rufio and the Cooolkidz on the Beautiful Emergence Records label is available from over 500 quality digital music stores online worldwide now. Get in early, cool kids.

– S. McCauley

Lead Press Release Writer

www.Octiive.com

Rufio and the Coool Kidz —

https://www.amazon.com/s?k=Rufio+And+The+Coool+Kidz

https://rufiothecooolkids.bandcamp.com/

0 notes

Photo

Hawaii 5-0 and Magnum PI at last night's 10th Anniversary Season premiere at Sunset on the Beach. #Jeonglorimikeohanalifepatterms #lifestylepatterns #mikewjeongphoto (at Waikiki Beach, Oahu Hawaii) https://www.instagram.com/p/B2prtJGDx6w/?igshid=gaphb0elzc33

0 notes

Text

Paradise Lost

The sign of a bad film is that it reduces to the text, be it screenplay or a piece of written fiction as source material. The sign of a good film is conversely its irreducibility to the text. Rather than just showing what happens or telling a tale, it is sometimes more appropriate to depict what happens or to depict a tale. For it is depiction, both visual and auditory, which is the primal means of cinema, whereas writing is of literature, song is of opera, rhyme is of poetry, and molding is of sculpture. The depiction of something can, however, as it often does in the case of cinema, manifest traces of all these means. In its depiction of a tale or merely the way things are, cinema can use words in dialogue or narration, cinema can use song and music in score or construction of milieu, and, above all, cinema can sculpt. Not only does one say in Tarkovskyan terms that cinema is sculpting in time but also that it sculpts time in the process. “Time is the material,” says Atom Egoyan [1] whose magnum opus, the eerie, enigmatic, and utterly unforgettable The Sweet Hereafter (1997) is celebrating its 20th anniversary this May since it competed for the prestigious Palme d’Or at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival.

Embracing the idea of time as the most vital material of cinema, Egoyan does not, of course, limit himself to the notion of cinematic sculpture. His most critically acclaimed film is also based on a novel, which it seems to have surpassed in more than one way (judging from a handful of reviews [2] since I have not read the Russell Banks novel of the same name myself), it makes use of both popular and folk music to a large extent, and it takes an allegorical framework from the poem The Pied Piper of Hamelin. But no one in their right mind could accuse writer-director Atom Egoyan for theft, borrowing, or lack of originality because it is precisely the blending of different means which makes The Sweet Hereafter the best film Egoyan has ever made. It is this unique combination which allows him to do what he does best: study the human experience of loss, desire, and obsession by sculpting in time and space, both of which are the primary characteristics of human experience.

The depicted tale in The Sweet Hereafter is undeniably special but it is anything but complex. It is a story about a small Canadian town where most of the children have been lost in a tragic school bus accident whose sole survivors are the childless school bus driver Dolores and Nicole, an adolescent crippled by the crash, a girl who dreams of becoming a rock star while her father, her musical benefactor, has also become her incestuous lover. Arriving to the town is a lawyer, played by Ian Holm, carrying his own burden of loss, who wishes to file a class action lawsuit with the townspeople against the bus company or anyone looking like a potential embodiment of guilt. The lawyer manages to rally up the townspeople, but during the last day of hearing for the lawsuit, Nicole surprises both the lawyer and her father by concocting a lie that destroys all possibilities for such a lawsuit: she claims that Dolores was driving too fast.

Had someone told me this story beforehand, I might have been, at best, slightly curious but would have expected nothing more than a visual book about people crying and overcoming grief. Fortunately, I had no prior knowledge of the film when I sat in front of the film screen three years ago and witnessed The Sweet Hereafter unfold in a screening at my local cinématheque. The important thing to notice is that the film was not what I expected because, to my mind, it is precisely the unexpected which characterizes the film throughout. Based on the above synopsis, one might expect a linear story where one first sees the townspeople before the accident, then sees the accident, and finally sees its aftermath. One might also expect a film utilizing a flashback structure, showing first the aftermath and then the accident as well as the events prior to it. One might even expect a quasi-Antonionian film where the accident would be shown at the very beginning after which the film delved into its post-impact on the community rather than studying the events before it. None of these expectations are true of Egoyan’s film, however. Having its kindred spirits in the great modernists, Egoyan’s The Sweet Hereafter breaks up Banks’ linear story structure and presents all the temporal levels simultaneously, tightly tied together, in an insightful fashion blending simultaneity and succession.

Egoyan had already mastered this kind of narration in his earlier film Exotica (1994), whose commercial success, new to Egoyan back in the day, enabled him to make his dream project, but a deeper raison d’être is found for it in The Sweet Hereafter. The reasons for the functionality of such narration in The Sweet Hereafter are quite simple. While Egoyan has always had an eye for an all-encompassing narration that embraces multiple temporal paths at once ever since the very first shots of his debut Next of Kin (1984), never before The Sweet Hereafter did he find a core strong enough to hold the diverging paths together, to cut their wings from flying too far, so to speak. This core is the emotion attached to the central event in the film’s story world (the school bus accident), but specific attention should be placed on the choice of words here: it is not the event itself that is the unifying core of the film but the emotion attached to the event; and it is this emotion that is articulated by Egoyan’s use of cinematic means.

Style as an Articulation of Loss

The emotion which Egoyan’s cinematic style articulates is, first and foremost, the emotion of loss. There is a lot to be said about all of the cinematic means utilized by Egoyan, but the best way to grasp Egoyan’s style in The Sweet Hereafter as a whole is perhaps the attempt to characterize them in general terms. From cinematography and editing to mise-en-scène and music, Egoyan’s cinematic style creates a serene aesthetics of tranquility which both exemplifies and expresses the human experience of loss.

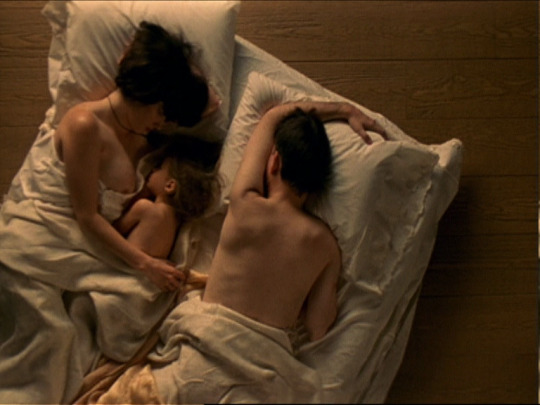

Above all, perhaps, the strikingly beautiful cinematography enhances a serenity and an enchantingly calm mood in The Sweet Hereafter. The camera moves slowly and the shots are, at times, strikingly long in duration. A long take, shot with a slowly tracking camera, starts the film as we see a wooden surface which turns out to be the floor of a summer cottage where a family of three is enjoying the bliss of their mutual existence. This is followed by another long take inside a car going through a car wash. In a later scene, there is a sequence shot introducing the character of Allison who sits next to the lawyer on a plane two years after the failed lawsuit. In a peculiar point of view shot, the camera tracks down the body of Dolores’ handicapped husband as the lawyer’s eye lingers on the man’s perished bodily existence. During the hearing of Dolores, the camera tracks slowly around the large table, reaching its target of Dolores in long medium shot. A similarly slow tracking shot recurs when Nicole is being heard: the camera slowly embraces all the characters one by one in the space and then goes by each one once more before switching to a calmly accelerating montage at the point when Nicole concocts the climactic lie, a pause to a dance, a denial of riches from those who do not believe in accidents.

In terms of camera movement in The Sweet Hereafter, the recurring upward movement of the camera turns into a visual motif. As the children arrive at the fair in a scene whose temporal distance to the accident remains unclear, the camera tilts up to a Ferris wheel. As the bus is curling in the narrow roads of the snowy landscape, the camera tracks to the sky in a beautiful aerial shot working as a shift to the airplane in a later temporal level where the lawyer and Allison are discussing. As Dolores breaks down after talking with the lawyer, the camera slowly tilts up to reveal a wall filled with the pictures of the deceased children above her solitude. As the lawyer’s wife lifts up Zoe, their daughter, in a field, the camera tilts up toward the sky. As Nicole shares a moment of incestuous romance with her father in a candlelit barn, the camera moves steadily upward in an eerie crane shot. In all of these examples, movement is a form of visual poetry. It is a line of temporal sculpture. It articulates something beyond words. It might bring depth or myth to the scenes but also challenge the characters in their self-constructed spaces of strange safety. In this sense, movement can articulate loss: it is as if the camera took departure from something that could no longer be retained, leaving those lost moments in their elusive distance. In the third example of the camera tilting to the pictures of the children on Dolores’ wall, this thematic dimension is emphasized by a striking use of rack focus as the pictures escape from the camera’s field of focus into an unknown realm beyond our reach.

If camera movement and optics are used to articulate the theme of loss in emphasizing the temporal distance between the different temporal levels, then juxtaposition of different shot scales is used to highlight spatial distance between different spatial locations. One of the first visual memories a spectator might recall from The Sweet Hereafter is its relentless use of breathtaking aerial shots of the school bus driving in the snowy landscape as if on a pre-determined path to destruction. Such large shot scales characterize the film throughout from the long shot of the lawyer walking from the house of one of the parents to his car to the long shot of Nicole leaving from Billy’s place to her father’s car about to take her to their secret place of incestuous love. Despite Egoyan’s emphasis on the distance between the camera and the character in these large shot scales, there are also some cases of intimacy between the camera and the character in extreme close-ups. There are two such cases and both feature close-ups of the mouth. One of these is a close-up of the mouth of Nicole’s father after he has witnessed his daughter concocting the lie, but for reasons of length emphasis shall be put on the other case.

It concerns one of the many phone calls the lawyer exchanges with his drug-addict daughter who is always calling for money from her father. The scene begins with a long shot of the lawyer standing by the damaged school bus after an intense confrontation with Billy, a parent who lost both his children in the accident after losing his wife some years before the accident. As the lawyer answers his phone, there is a cut to a long shot of the lawyer’s daughter, Zoe standing in a phone booth in the middle of multiple highways in an unnamed city. This is followed by a medium close-up of the lawyer from which there is a cut to a full shot of Zoe in the phone booth. Another medium close-up of the lawyer and then a long medium shot of Zoe. Yet another medium close-up of the lawyer and then a surprising cut to a close-up of Zoe as a baby in a point of view shot from the lawyer’s perspective in another temporal level. Then a return to the medium close-up of the lawyer. The scene concludes with two shots: first an extreme close-up of Zoe’s eyes but then the camera tilts slowly to her mouth, second an extreme close-up of the lawyer’s mouth but then the camera tilts slowly to his eyes.

There are many things to notice about Egoyan’s stylistic choices in this scene. The surprising cut to the flashback, which has been explained in an earlier scene where the lawyer told Allison how Zoe once came close to death when bitten by a spider as a child, occurs as Zoe gets angry, complaining how her father never believes her. The cut signifies distance between father and daughter. In an earlier scene, the lawyer told Billy about his daughter, saying that “something terrible has taken our children away,” referring to both the accident and his daughter’s condition. During this phone call, it is as if he escaped to the past, perhaps in part hoping for his daughter’s premature death so she could be better encapsulated in the unreal innocence of childhood, a perverse pleasure he might believe the town’s parents enjoy. Another thing to notice is the use of the same medium close-up of the lawyer throughout, while there is a continuous, analytical development of shot scales from larger to smaller in Zoe’s case. This is typical because the environment she is in has to be established for the spectator, but it also enhances the distance between the two characters. The final thing to notice is the juxtaposition of the two last extreme close-ups which are set against the two establishing long shots at the beginning of the scene. The camera movement in these shots is reverse: first downward and then upward. It further enhances the intimacy, on the one hand, and the distance, on the other, between the characters. During the moving extreme close-up of Zoe’s face she tells her father that she can hear him breathing to which her father responds that he can hear her breathing as well. As Zoe starts breaking down and says that she is afraid, there is a cut to the mobile extreme close-up of the lawyer’s face. While the camera lingers on his mouth, he says: “I love you Zoe.” As the camera starts tilting upward, he continues: “I’ll soon be there. I’ll take care of you, Zoe. No matter what happens, I’ll take care of you.” The poignancy of these lines lies in the fact that they are left echoing in the void since they receive no response from Zoe. What is more, she is never seen again in the film, but the latest temporal level in the film, that is, the flight two years after the accident, ensures us that nothing has changed since the lawyer is travelling to another clinic to see his daughter. Their distance remains insurmountable despite access to such technological achievements as telephones and airplanes.

By visually treating the themes of distance and intimacy in such a complex fashion, Egoyan is able to articulate loss by cinematic means. The lawyer has lost the connection to his daughter and can only have these ironic instances of connection through the airplane and the telephone which is a paradoxical device that both connects and separates people. This paradoxical nature is also captured in the use of shot scales and camera movement in the scene analyzed above. The characters are very far away from each other both spatially and emotionally which is enhanced by the different shot scales used to depict them in their respective spaces. The two final shots ironically both bring them together since the shots are in the same scale and pull them apart since the camera movement is reverse: the upward movement from the lawyer’s mouth to his petrified gaze as he mechanically delivers the lines to Zoe’s corresponding silence emphasizes their unresolved distance.

Given that Egoyan’s bravura is the aesthetic combination of different means, it is no surprise that his stylistic program in his magnum opus does not stop at the brilliant use of the camera. In fact, The Sweet Hereafter could be appreciated merely for its beautiful, lyrical mise-en-scène. Egoyan constructs spaces which vary from warm indoor spaces to cold outdoor spaces of gorgeous mountain landscapes in winter. The most striking visual conflict is experienced between the two temporal levels farthest from one another in chronological order: the sterile space of the airplane and the ethereal warmth of the summer cottage in the lawyer’s flashback, partly in the real past, partly in a fantasy of the past. Egoyan’s mellow, full-bodied mise-en-scène is characterized by strong yet pale colors with the color blue as peculiarly dominating from the bluish car wash and the club lights next to the phone booth from where Zoe first calls her father to the snow in the winter dusk, Nicole’s clothes and the curtains, the blanket, and the door in her new room after the crash.

Egoyan’s use of color, light, and space further articulate the theme of loss. The dominating color blue, characteristic of the entire atmosphere of the film, is the color of coldness and innocence, it is the color of melancholy, it is the nostalgic and romantic color of sweetness that is challenged, for one, by the bright redness of the blanket Nicole wraps herself into before sharing an intimate moment with her father in the candlelit barn. When the lawyer first arrives to town, he meets a couple who own the town motel in order to inquire who he should try to rally up for the lawsuit. In other words, he needs help to separate “the good people” from “the bad people”. The husband’s chips-munching behavior in the scene already underlines his arrogance and self-indulgence while he is trying to critique others for their actions. Egoyan yet further emphasizes the irony of such an attempt at separation by having the lawyer move to a different space to answer his drug-addicted daughter’s phone call while the motel-owning couple is left to argue on a deeper plane who of the townspeople are “the bad people”. In terms of lighting, Egoyan’s style is most apparent in the unforgettable ending of the film where a quick flash of bright light emerges before Nicole standing by a window. The peculiar thing about this device is not only its self-awareness, almost turning the spectator away from the diegetic world, but the fact that the scene takes place before the accident. Yet this succession is only diegetic; in the poetic space Egoyan has created, there is no such succession. Thus the flash of light appears as a cut, a cut to the sweetness that Nicole, among others, is about to lose.

In addition to more elusive elements of light and color, an integral role in Egoyan’s mise-en-scène is played, of course, by the school bus. The school bus is first seen in the film when the lawyer exits his car in the car wash as he seems to be stuck. When he exits the car wash, he ends up in Billy’s apartment from whose window he can see the damaged school bus by the road. Accompanied by eerie screams of the children from an off-screen space, and obviously from a diegetically earlier temporal level, the school bus becomes a symbol for a paradise lost, for the loss of sweetness in a fragile world created by its fragile inhabitants whose world can be cut open by a flash of bright light.

Besides cinematography and mise-en-scène, Egoyan’s masterpiece of blending material is unforgettable precisely due to its breathtaking use of music composed by Mychael Danna who is also responsible for the alluring music of Exotica. Danna’s music is simultaneously flamboyant and utterly tender, a seeming paradox that is born from the juxtaposition of the lighter sound of the flute and the heavier sounds of the other instruments. The music is thematic, since it is associated with The Pied Piper of Hamelin read by Nicole, but above all alienating. When Egoyan uses the music with the shots depicting the last journey of the school bus, the music does not work as a paraphrase (in the sense that it would accompany the diegetic events) nor does it really identify the spectator with the depicted events. On the contrary, Danna’s music seems to alienate the spectator, working as a higher level of discourse as if mythologizing the diegetic event of the accident. It brings the event forth, it puts it on an unreal pedestal of cosmic tragedy which shakes the core foundations of the townspeople’s fragile universe. It is important to notice that while Danna’s music does not accompany neither does it counterpoint. While music that sounds Eastern seems quite unfit for an ordinary Canadian town in the middle of nowhere, it does not feel to create a striking counterpoint to the diegetic events either (in the sense that it would be joyful while the events were sorrowful, for instance). The music shares something in mood to the diegetic events. They share a metaphysical bond. In this sense, Danna’s music used by Egoyan could be characterized as creating a parallel dimension, a parallel level of discourse which attains commentary contact with the diegetic world without fully fitting into it or fully opposing it either.

In addition to Danna’s Armenian flute music, Egoyan also uses popular music mainly sung by Canadian singer/actress Sarah Polley who plays the role of Nicole. This music is both diegetic, in the sense that Nicole really sings in the story world (at the fair in the beginning, for one), and non-diegetic, in the sense that the songs do not always directly belong to the story world. In general, however, it seems best to say that the use of the music in The Sweet Hereafter cannot be entirely appreciated by these kinds of categories. For example, when the song “Courage” is heard sung by Polley as Nicole’s father is taking his daughter to the hearing, there is no one in the story world singing the song, but at the same time it is as if Nicole -- or some higher level of discourse connecting to her -- was expressing her emotions. This becomes even more convincing when considering the fact that Nicole has just pointed out to her father how she is “a wheelchair girl now” and how it is “hard to pretend that” she is “a beautiful rock star,” a poignant reminder of the father’s guilt for his abuse of his daughter. Although the songs sung by Polley do not feel as contradictory to the milieu of the story world as Danna’s Armenian flute music, they too seem not to accompany or to counterpoint the diegetic events. Rather they too create a parallel, commentary dimension to the events witnessed by the camera as if enriching the experience. They serve as a reminder of something being lost, the lack of a primordial sense of connection.

As such, Egoyan’s style in The Sweet Hereafter articulates and expresses the human experience of loss by cinematic means. From the distance and movement of the camera as well as the juxtaposition of different shot scales and choices in editing to use of light, color, and music, Egoyan depicts a tale of loss, how the spatio-temporal human experience always entails a loss of something. At the beginning of this section it was mentioned that not only does Egoyan’s style express but also exemplify the experience of loss. This has become evident through the above analysis of the style of the film. Egoyan’s style bears a similar fragmentary quality and a sense of disconnection as his narration. The large shot scales and the complex compositions utilizing depth and many planes simultaneously coerce the spectator into experiencing loss: one must choose the objects of one’s visual and auditory attention in the process of which one loses something. As a result, according to Vivian M. May and Beth A. Ferri, the spectator becomes aware of the process of meaning making since meanings are not passive, enclosed and stable but, on the contrary, active and transient [3]. In this sense, already on the level of style in the sense of consistent use of cinematic means, Egoyan’s film exemplifies the experience of loss which is further elaborated by the fragmentary structure of his narration.

Fragmented Narration as a Shattered Mirror of Loss

As said above, it is the unexpected that characterizes Egoyan’s The Sweet Hereafter. If Danna’s music is at the very least surprising in the context of this particular story and the beginning shot of a wooden surface developing into a breathtaking sight of a dormant family on the floor of their summer cottage manages to catch the spectator off guard, so to speak, Egoyan’s narration as a whole in the film is even more challenging. Since it is challenging, it also draws the spectator’s attention to itself and as such becomes self-aware instead of being transparent in the classical sense of cinematic narration. I would argue, once again, that one remembers the film precisely for the way its story is told rather than the story itself: while one might certainly recall the school bus accident, the several interconnected stories fade in memory at the expense of the unique mode of narration. Like Egoyan’s cinematic means, so does his narration both express and exemplify the experience of loss.

It is time, as one of the two primal features of human experience, which is the material to Egoyan’s cinema, and narration, of course, is a temporal process of narrating something. Despite the fragmentary structure of narration in The Sweet Hereafter, its use of different temporal levels can be analyzed in distinct parts quite easily. In chronological order, there are five temporal levels. First, there is the summer when the lawyer’s daughter Zoe was bitten by a spider and her father had to rush her to the hospital, being constantly on the verge of cutting her throat open in case it would swell up. This includes the first shot in the film, the flashback shots when the lawyer tells of the incident to Allison as well as the cuts to these shots in some other scenes with the lawyer (as in the scene analyzed above with the lawyer’s last phone call with Zoe). Second, there is the time before the accident which contains the scenes at the fair, the night before the accident when Nicole reads The Pied Piper of Hamelin to Billy’s kids while Billy visits her secret lover at the motel after which Nicole is taken to the candlelit barn by her father. Third, there is the day of the accident (sometime in 1995). This contains the accident, the brief scene with Billy experiencing its aftermath as his children among others are put in body bags, and the final voyage of the school bus leading to the accident. Fourth, there is the time after the accident. This includes the scenes where the lawyer interviews the townspeople trying to rally them up for the lawsuit, the scenes with Nicole in the wheelchair at home and during the hearing. Fifth, there is the time two years after the accident (identified as the year 1997). This includes the scenes at the airplane where the lawyer talks with Allison, Zoe’s childhood friend, as well as the scene at the airport where the lawyer encounters Dolores, now working as the bus driver at the airport.

Relations between events within these distinguishable temporal levels may be themselves complex, but even more so with regards to the relations between the temporal levels. In a fashion reminiscent of avant-garde narration or lack of any narration, The Sweet Hereafter begins with an ambiguous blending of three different levels: first there is a shot of the lawyer’s family in their summer cottage (the first level), then there is a shot of the lawyer in the car wash having a telephone call with his daughter (the fourth level), and then a scene at the fair where Nicole is practicing with her band (the second level). The first time spectator has no idea what is going on and what the connections between these levels are. While the first scene can be dismissed as a vague event somewhere in the past, a background image for the opening credits, the scene at the fair remains of sheer ambiguity with regards to its temporal relation to the other diegetic events on the second level as well as to the other levels.

It is this ambiguity that lies at the core of Egoyan’s complex narration which operates essentially with the unexpected. For this peculiar opening is anything but exceptional in the whole of the film. Narration does have diegetic information regarding the events of the story world, but it communicates this information quite slowly to the spectator. Many informative gaps are left with regards to the temporal relations but also the content of the shots: the incestuous relationship between Nicole and her father is merely hinted at with one scene without any dialogue. It is this ambiguity which both expresses and exemplifies the experience of loss: the loss of an epistemic connection coincides with the loss of an existential connection.

A similar ambiguity can be noticed when trying to categorize the kind of narration in The Sweet Hereafter. First, one might try to categorize focalization in the film. While the film has no single narrator, Nicole does seem to gain an important position as her voice prevails on the soundtrack as voice-over. This begins with her reading The Pied Piper of Hamelin to Billy’s children, but towards the end especially her voice takes a stronger position as an intra-diegetic narrator when, as the lawyer sees Dolores at the airport, she says:

As you see her, two years later, I wonder if you realize something. I wonder if you understand that all of us - Dolores, me, the children who survived, the children who didn't - that we're all citizens of a different town now. A place with its own special rules and its own special laws. A town of people living in the sweet hereafter.

The way how Nicole articulates feelings of loss in this phrase deserves its own essay, but here it suffices to notice that she gains a higher place with regards to narration than any other character. Taking into consideration that she also represents a challenge to the lawyer and her father, who have sometimes been interpreted as an embodiment of a simpler, classical cause-and-effect narrative [4], this narrative device once again expresses and exemplifies the experience of loss; it is the loss of control over events. The lawyer proclaims that “there is no such thing as an accident” and believes that “something terrible has happened that has taken our children away from us,” but in contrast to Nicole’s melancholic acceptance of “the sweet hereafter”, the lawyer’s beliefs fall flat and merely represent an attempt to escape loss. The lawyer, Nicole’s father, and most of the townspeople try to find a reason for the accident, which coincides with an unconscious pursuit for a raison d’être for their existence, but Nicole denies them of this possibility in a similar manner as Egoyan’s narration denies the audience of a clear, classically structured plot, a stable meaning as an illusory reflection of the audience’s meaningful life. Instead, the audience is forced to stare at a shattered mirror, a poignant picture of their meaningless existence.

In addition to focalization, or the kinship between narration and the character of Nicole, one could, secondly, try to categorize Egoyan’s narration with the notions of diegetic and mimetic narration. Mainly used in literature theory, the two notions distinguish narration that merely shows what happens without drawing much attention to the act of showing (mimetic narration) and narration that tells what happens, making it more or less explicit that it is being told to someone by someone (diegetic narration). Cinema is the epitome of mimetic narration since it usually shows us things rather than tells them. This is not very true of The Sweet Hereafter, however. Narration lingers on not showing the central event of the story world, that is, the school bus accident, many things are left open, and, above all, the whole film draws attention to its narrative structure due to its peculiarity: it is as if someone was telling this tale to us, though it remains unclear who this someone is; the reason for this ambiguity is that someone is not telling us a tale but depicting it. It is noteworthy that this attention to structure does not draw the spectator away from the story world or hinder the spectator’s potential interest for the characters; Egoyan himself has noticed how he finally discovered an emotional core strong enough not to drive the spectator away from his non-linearly structured films [5].

It is generally thought in literature theory that the so-called free indirect discourse situates itself between diegetic and mimetic narration, which is the case in The Sweet Hereafter as well. While its narration could be characterized as diegetic, it also uses free indirect discourse especially in the quick cut to Zoe’s face in the first temporal level in the scene analyzed above where the lawyer has his last phone call with Zoe as well as in the scene where Billy experiences the horror of the school bus accident, witnessing a paradise sinking down to the bottom of an icy lake. Towards the end of this scene, there is a low-angle shot of Billy which is followed by a cut to a close-up of a body bag. The important thing to notice is that Billy is quite far from the scene of the accident. He is on the hill, whereas the body bags are located closer to the icy lake. It is as if the cut focalized into Billy’s perspective without really focalizing into it. This peculiar form of narration is known as free indirect discourse: saying, thinking, or narrating something through someone without embracing their perspective completely. It is even more striking that this scene is followed by a confusing cut to the shot of the lawyer’s family (which the first time spectator does not yet know to be the lawyer’s family) at their summer cottage before the lawyer goes on to tell about the incident to Allison. The juxtaposition of these two tragedies at the center of the film emphasizes the experience of loss. They remain unclear tragedies without clear focalization, as though escaping beyond our reach.

Another essential example of free indirect discourse in Egoyan’s narration in The Sweet Hereafter is the scene where the lawyer is interviewing Dolores, the school bus driver. As Dolores begins to tell about the day of the accident to the lawyer, there is a shift from the fourth level to the third level. At first glance, it might feel as if narration focalized into Dolores’ perspective since she is talking about the event, but the aerial shots as well as the scene with Billy analyzed above challenge this interpretation. The “flashback”, if it can even be called that, is motivated objectively, and narration in these scenes is better grasped as free indirect discourse. The Sweet Hereafter has an ambiguous narration to it which alternates between different perspectives as well as the lack of intra-diegetic perspectives in a fashion which both expresses and exemplifies the experience of loss: narration mythologizes the central event of the accident and creates both distance and intimacy to it.

A narrative device of paramount importance and worthy of specific attention in The Sweet Hereafter is, of course, the use of the Robert Browning poem The Pied Piper of Hamelin. As off-screen voice-over narration, the poem is first heard in the scene where Nicole’s father takes her to the candlelit barn. Nicole reads the part “one was lame / and could not dance the whole of the way” of the poem and repeats it in the beginning of the scene of the hearing towards the end of the film. The notion of “being lame” is associated not only with Nicole’s physical handicap due to the accident but also with her mental suffering due to incest. Thus her frustration for not being able to “dance the whole of the way” with others -- the townspeople with the lawsuit, on the one hand, and the children to death, on the other -- expresses loss. At the end of the latter scene, Nicole’s reading surpasses the poem and its lyrical form merges with her personal account of the events in voice-over: “As you see her, two years later...” The poem serves as an allegorical framework in which the lawyer represents the pied piper who summons the townspeople by his side, but it also expresses the experience of loss. It emerges as a mythological explanation for the accident, as an allegory for the “something terrible” that has taken the children away from the townspeople. Steven Dillon writes aptly that it

serves as a kind of myth or anti-myth for why all the children are away, for ‘why’ the children have been killed in the bus crash. As the children vanish into the sweet hereafter, the overheard poem serves as a kind of relentlessly unsatisfactory aesthetic explanation. Nicole uses the poem to read to sleep two children who will be killed; she holds the book over legs that will soon be crippled. The rhymes of the poem are clever, even soothing; the lines of the poem are strangely appropriate to the visual context; but the suffering is not diminished, not at all. The poetry takes us into impossible worlds, but worlds which do not help us escape. This lyricism is neither idyllic nor utopian. [6]

A narrative theme, so to speak, which comes up again and again when discussing narration in The Sweet Hereafter is, of course, time. There are different temporal levels in the film, the way how narration occurs in time influences the way one categorizes it, and the temporal relations between the different narrative elements play their part in the process of making meaning. In most of Egoyan’s films, specific emphasis is placed on the way how temporality constitutes subjectivity of character and how this constitution emerges temporally. In Exotica, an enigmatic web of different temporal levels creates a slowly unfolding revelation of the protagonist’s wounded subjectivity; in Family Viewing (1987), a man tries to re-constitute himself by erasing filmed footage of his past and replacing it with homemade pornography; in the beginning of Next of Kin, two parallel temporal levels compensate one another in articulating the protagonist’s loss of identity and his change of identity. In kindred spirit to Marcel Proust, Egoyan does not in The Sweet Hereafter try to do this either by taking a long period of time and several events or by portraying temporal chain of events in a linear, chronological fashion. By excluding these options, Egoyan embraces an aesthetic strategy, in philosophical proximity to Proust and other modernists, in which he takes individual moments that in connection to others slowly uncover the characters’ subjectivity; these individual moments are joined together -- their wings are cut in order to prevent them flying too far away -- by the emotion of loss attached to the central event, a temporal nexus for the scattered temporal levels. What is more, Egoyan’s reliance on non-linear and fragmentary narration emphasizes the lived dimension of time as the past, the present, and the future merge together as if in an existential epiphany where simultaneity and succession were blended as one.

Given the more or less formal approach of Egoyan’s cinema, specific attention should be placed on the rhythm of his narration. Dillon quite aptly notices that The Sweet Hereafter is more poetic than prose-like, despite having its source material in the latter [7]. This is not a mere analogy, which might find its inspiration from Egoyan’s insightful use of The Pied Piper of Hamelin, which is not featured in Banks’ novel, but a profound observation of the depth of Egoyan’s work. The Sweet Hereafter is a poetic film because its narration operates on the basis of images and associations rather than the laws of cause and effect. The shot with the lawyer looking at the damaged school bus as off-screen screams of the children are heard is followed by a cut to the scene where the children arrive at the fair some time before the accident. In this particular transition, it is not really the lawyer performing the association, as noted above in characterizing Egoyan’s narration as free indirect discourse, but narration performs the association partially through him. There is a serenely flowing rhythm at work in the film, a rhythm which ties different temporal levels together on the basis of the human experience of loss. This is evident also towards the end of the film where a fluent montage sequence covers a wide range of events and temporal levels: as Nicole’s voice-over is heard on the soundtrack, first the lawyer sees Dolores at the airport, which is then followed by a cut to another scene where Billy walks away from the damaged school bus which is now being carried away after the failed lawsuit, and then a cut takes us to the fair as the camera tilts from the Ferris wheel to Nicole in blue as she is looking up, which is followed by a cut to a shot of the outer side of another amusement park ride, and, finally, the sequence concludes with Nicole’s voice-over reaching its end as we see her closing the book and walking away from the children’s beds to a window where a brief flash of light emerges before her, possibly from the headlights of her father’s car.

This montage sequence is a pivotal moment for a film, a beautiful sealing conclusion, but, above all, an exemplification of the film’s rhythm. While Nicole’s voice-over talks about the townspeople now “living in the sweet hereafter” where everything is “strange and new,” the images seen do not belong solely to the third and fourth temporal levels, that is, the levels after the school bus accident. Egoyan’s relentless tendency to merge the levels together lies at the core of the film’s rhythm, a rhythm where images do not seem to clearly follow one another but seem to coalesce. If Andrei Tarkovsky is right in claiming that the rhythm of the film always reflects the director’s perception of time [8], then Egoyan’s reflects a phenomenological notion of subjective time-consciousness where the mental processes comprehending the width of presence, in the sense that the present moment contains more than what is immediately and presently given, merge simultaneity and succession into complementary notions. Like Exotica, The Sweet Hereafter ends with a seemingly random moment in the past (though in the latter case its dramatic significance is far clearer) which is, due to Egoyan’s peculiar rhythm and his perception of time, elevated into a moment of epiphany, a moment of the deepest kind of truth, the primordial truth of disclosure which is not experienced in court hearings.

It is also but one example of many instances where narration was as if halted. Since Egoyan’s narration flows as a serene stream of images and associations, narration in the traditional sense (telling a tale in a temporal process) becomes halted and challenged. These moments where narration in the traditional sense becomes halted are analogous to kinds of ellipsis. The surrealist scene where Nicole goes to the candlelit barn with her father lacks any dialogue or any form of narrative explanation since the voice-over reading of The Pied Piper of Hamelin by Nicole in another temporal level seems to have no apparent connection to the diegetic events in the screen space. As such, narration becomes halted. In a similar fashion, the final montage sequence analyzed above lacks narration in the traditional sense, consisting of a rhythm with its own special rules and laws. Another instance is the brilliant cut from the scene of the school bus accident to a slowly spinning high-angle, aerial shot of the lawyer’s family sleeping on the floor of their summer cottage. At first, this cut startles the spectator. It might have a seemingly soothing function as it takes narration away from an emotionally difficult subject matter, while it also alienates the spectator from the story world as narration clearly becomes self-aware at this point (meaning that the spectator pays attention to the editing contrary to the dogmas of classical transparent film narration), but this soothing turns out to be extremely transitory since the cut works as a transition to the scene where the lawyer tells about his own accident in the past where his daughter was about to die. There is only an emotional connection between these two scenes of accident, but since their connection is never articulated by any character, the cut between them remains a moment which halts narration in the traditional sense. Since the film goes along, narrating its way as it was supposed to, this might prove nothing but that Egoyan is not interested in narration in the traditional sense; his films are narrative but on another level.

Like Egoyan’s style in The Sweet Hereafter, so his narration both expresses and exemplifies the human experience of loss. The examples above of narration in the traditional sense becoming halted show how narration exemplifies loss in its loss of diegetic information. In the scene where Nicole concocts the climactic lie, narration is unable to point to any psychological motives in the character delineation of Nicole as to why she lied, though the editing (the cut from a medium close-up of Nicole’s face to an extreme close-up of her father’s mouth) accompanied by the off-screen voice-over reading of The Pied Piper of Hamelin by Nicole might implicitly suggest something. In the cut from the scene of the accident to the slowly spinning aerial shot, there is also a sense of narration losing control; it does not know how to cope with the accident nor does it at the moment provide the spectator with any insight as to why the image is being shown. In the final montage, finally, narration loses information about what happens afterwards and, accompanied by Nicole’s reading, as though spins to a space-time travel of the temporal levels, ending with the scene of the night before the day of the accident.

When it comes to narration exemplifying the experience of loss, several commentators have supported these claims above. To Patricia Gruben, Egoyan’s narration in The Sweet Hereafter by calling images such as the spinning aerial shot “fetishized images” which “are detached from the narrative, interrupting and displacing the dramatic trajectory of the story” [9]. Similarly, May and Ferri highlight how “The Sweet Hereafter is a collective of narratives that intersect and interrupt one another” [10]. According to them, “the film’s multiperspectival narrative structure resists the causal explanation and neat closure that the lawyer, the community, and even the viewing audience might desire.” [11]. Contrasting Egoyan’s film with Banks’ novel, Dillon has also emphasized how the film manages to embrace the theme of the lack of explanation better than the more conventional narrative-wise novel: “although the novel is founded on the crushing lack of explanation surrounding the accident, it might be said that the very form of the novel, in its presentation and manner of telling, refutes its own metaphysical pessimism. The book is its own ferocious lawyer, and creates a world, after all, with no accidents of narrative, but only accidents of event.” [12]. Dillon hits hard to the core by talking about “accidents of narrative” because that is precisely what has been described here: the film’s narration exemplifies the themes of the film and as such embraces them more completely. The lack of explanation prevalent in the diegetic world is also prevalent on the level of narration as it is coerced into finding its epistemic capabilities to be limited because the objects of its epistemic acts are themselves ambiguous.

Egoyan’s narration in The Sweet Hereafter is fragmentary and as such expressive and exemplificatory of the human experience of loss. Despite its fragmentary, elusive, and challenging nature, it does not estrange the spectator from the work of fiction. While the narration might be alienating, it is not alienating to the extent that the spectator loses their interest. In fact, Egoyan’s earlier films might have shown signs of such estrangement: all of his films from Next of Kin to Calendar (1993) present a surrealist narration which often does not form a clear-cut whole. Even though Exotica, the film preceding The Sweet Hereafter in Egoyan’s oeuvre, was not only a critical success but also a commercial hit, the latter was probably merely due to its erotic aspects and the possibility of watching it as an “erotic thriller”. The reason for the success of Egoyan’s narration in The Sweet Hereafter has been explained by the strength of character delineation and a clear central event in the story world [13]. Furthermore, it has been emphasized in this essay that the decisive factor in the film’s success is the strength of the emotion attached to the central event and to the characters involved in it. This is the emotion of loss. When all pieces of the film fall perfectly together with regards to this one theme, it doesn’t really matter for the average movie-goer whether they can identify with the characters. The film as a whole is the character one is most interested in.

The Many Meanings of Loss

Given that Egoyan’s cinematic style and narration in The Sweet Hereafter articulate, express, and exemplify loss, it seems appropriate to take a closer look at precisely what this loss is. Many have associated political meanings to the film’s style and narration, but upon viewing the film itself these meanings are conspicuous only by their absence. In the context of Egoyan’s style and narration, the film seems to be much better than a political analysis of the society. It is something much more universal as poetry, following Aristotle’s notion, always should be. It is a universal expression of the human experience of loss which is strongly a temporal experience; not only in the sense of temporality since all experience is temporal but also in the sense of the experience and subjective sense of temporality. The experience of loss cannot be comprehended without addressing time and, as seems appropriate in the present context, neither can time be comprehended without addressing loss.

The political interpretations of The Sweet Hereafter derive from a feminist reading. To May and Ferri, the film allows the spectator to become aware of subject formation and narratives of the subordinated (the woman, the handicapped) [14]. According to them, the character of Nicole represents a figure who opposes the social subordination by males which is reflected by the lawyer’s and the community’s hunger for a clear, cause-and-effect narrative of reality without accidents. Similarly Katherine Weese argues that as the lawyer tries concocting a cause-and-effect narrative of the accident and Nicole’s father tries to acquire financial gain for the loss of his sexy rock-star daughter, Nicole “sees a way to write herself out of both narratives” [15]. To Weese, Nicole represents a feminine perspective that threatens the masculine way of looking at things.

With all due respect to these scholars and their papers, it seems legitimate to challenge their unnecessary feminist interpretations of the film. In creating a naive, black-and-white distinction between feminine and masculine perspectives, the writers seem to fall to the precisely objective point of view they themselves are criticizing; that is, the objective point of view to the distinction between the two perspectives -- as if there were such a perspective. It is also noteworthy to add that the director-writer of the film is a male, let alone the fact that the author of the book is a man, both of whom, according to this interpretation, do not seem to share a characteristically masculine perspective. In addition, while the writers are right when they say that the lawyer does not believe in accidents, but rather claims that “something terrible has happened that has taken our children away”, wanting to find an embodiment for that “something,” they seem to ignore that all the town’s women (with the exception of Nicole) are ready to join the lawyer’s quest of finding out the “truth” as well. In fact, the only person besides Nicole who does not seem to believe in the lawyer’s quest is a male character, that is, Billy, a very typical male character, one might add, with his truck, mustache, and average Joe clothing. In one scene, Billy asks his mistress, the wife of the motel-owning couple, “do you believe that?” regarding the lawyer’s suggestion that either the bus or the fence by the road was faulty, to which she answers “I have to”. Later in the scene, she starts concocting her own cause-and-effect narrative by asking Billy why did he give the shirt of his deceased wife to Nicole, who wore it during the day of the accident, believing that such an act might have supernaturally caused the accident.

No one in their right mind should deduce from this that Egoyan’s film is criticizing the female character in the scene. On the contrary, The Sweet Hereafter seems very indifferent to gender. Although there might be no apolitical nor asexual spaces in any absolute sense in cinema (or in human social reality), and it is true that sexuality is an essential theme in Egoyan’s cinema, it still seems plainly unnecessary to locate gender into a film which seems to be about something else. I was, in fact, fairly surprised when I discovered that it was precisely the perspective of gender which was most dominant in academic articles written on the film. Fewer articles have been written regarding the film’s style and narration as such, a lack which this essay has been trying to compensate.

To my mind, The Sweet Hereafter can be appreciated merely by looking at its style and narration, but it is also true that the spectator often has a need to see meaning in the “what” as well as the “how” of the films they see. It might be argued that such meaning making is also the function of art in general. Therefore, there is absolutely no need to throw the notion of interpretation out the window, but see Egoyan’s film as a universal treatise on the experience of loss which is both expressed and exemplified by his style and narration. It should be added that there is no need to make the false claim that the above sections would have been free from interpretation. If anything, The Sweet Hereafter might prove how such a separation in the absolute sense is impossible.

An integral theme in the whole of Egoyan’s oeuvre is obsession. This obsession, I believe, is born from the experience of loss. When Egoyan’s characters feel that they lose control in reality, they start to create their own worlds where they have control once again. It is the fragility of these private worlds which Egoyan studies in his cinema. In The Sweet Hereafter, it is, of course, the accident which makes the people lose control and it is the clear cause-and-effect narrative of the accident which gives them an illusory feeling of control. Typically for Egoyan, their obsession shows itself in the form of photographic media. Dolores, the childless school bus driver, tells the lawyer how she used to see the children by the road as “berries waiting to be plucked,” berries to “put in my basket”. They are like berries, perfect, harmless creatures who she collects to the bus-basket of her artificial family which lasts for a daily bus journey. This pattern of behavior allows Dolores to believe in a clearly functioning, perfect world of harmony where she is in control. After the accident, she clearly repeats this pattern in collecting all of the children as photographs on her wall as if berries hanging from a tree. To the lawyer, on the other hand, the school bus turns into the concrete embodiment of the incident which he goes to secretly videotape in the night. The bus, and the accident for that matter, thus turns into a tangible, manageable object of research, a fetishized object of his mediate gaze. This scene is probably the scene which most clearly echoes Egoyan’s earlier films where people are obsessed with filming and looking at videotapes to achieve a control over their existence from the protagonist of Next of Kin who looks at the videotapes of another family’s therapy session to the woman in The Adjuster (1991) who records pornographic scenes on screen with her camera and Calendar where Egoyan himself plays a character obsessed with taking perfect photographs of Armenian churches at the expense of destroying his relationship.

Another interesting instance of trying to maintain the sense of control in The Sweet Hereafter is the character of Billy and his habit of driving behind the school bus to wave at his children sitting at its backseat. “Billy loved to see his kids in the bus,” Dolores explains to the lawyer. “It comforted him,” she claims. It is of special interest here that Billy is never seen with his children in the film. They are seen running toward the camera in an eerie shot, which can be interpreted as Billy’s flashback at the scene of the accident, and they are seen talking with Nicole as she reads to them. When Billy is driving behind the bus as it is about to crash, he is separated from a direct contact to them by two images or screens, if you will: the windshield of his car and the rear window of the school bus. The presence of these screens enhances the distance between the characters and the fetishist connotations entailed in the distance. Billy, as well as the other adult characters in the film, fetishizes his children into something pure and innocent that cannot be lost. Patricia Gruben has associated these themes with a psychoanalytic interpretation of the film: the adults try to gain a primal connection that has been lost and cannot be retrieved by mythologizing their children. Gruben writes that:

Three Egoyan films from the 1990s -- Exotica, The Sweet Hereafter, and Felicia’s Journey (1999) -- are driven by the longing of adults to penetrate the veil of child-hood and return to a state of remembered or imagined innocence. In each film, an adult, tortured by the pain of a life isolated from human contact, reaches out to a child or child-substitute for emotional intimacy. In each case, however, the longing is unfulfilled because the child is a surrogate for an earlier, more primal relationship that has ended in estrangement or death. Connected to this death, sometimes even the cause of it, the adult is psychically paralyzed, unable to atone or grieve and move on. [16]

The characters’ obsession to keep things in control shows itself in their relentless desire to turn reality into something tangible. While Egoyan does not condemn his characters in the least, his films often do portray people who are unable to let go of grief. Billy has not been able to stop grieving over his wife. The lawyer has been “divided into two parts” ever since the spider accident with Zoe. Neither of them are never seen in the same space with their children because there is no connection; they have lost it. It is this unsolved paradox of loss and control which lies at the core of this inability. In the end, Nicole becomes a fetishized object through which the lawyer among others tries to achieve control and the lost primal connection to childhood, but such a connection is denied from him; not only because of Nicole’s lie but also because of its utter impossibility.

What is being lost by the characters is best grasped as sweetness. Although the film’s title quite clearly comes from Nicole’s voice-over monologue in the final montage sequence, which suggests that the townspeople are now living in “the sweet hereafter”, the title can also be seen to emphasize the lost sweetness of the idealized past. The sweetness of their life in the material hereafter is bittersweet: they are haunted by loss but they can also enjoy the idealized sweetness of the past unlike the lawyer who is reminded of its unreal, idealized nature by his daughter’s constant problems. Thus The Sweet Hereafter is a tale of the loss of imagined sweetness. The past appears as idyllic, but it is also constantly implied that the sweetness of the past might not have been real. The degraded school bus is the symbol for the harsh reality in its damaged, rusted shape, the symbol for the destruction of sweetness that never really existed. As Nicole closes The Pied Piper of Hamelin, shuts the lights, and walks away from the children, she, too, steps into the world of the sweet hereafter, the world of the dead which is characterized by the absence of sweetness.

The reason why psychoanalytic and political readings of the film ought to be avoided, or considered unnecessary at least, is that even as a treatise on the experience of loss, The Sweet Hereafter is not a film about something particular. It is a film about the universal. It has an epic ethos which puts a relatively small incident into vast proportions. The Sweet Hereafter is like a gorgeous mural or a hypnotic symphony which tells about the greatest things of all: the loss of paradise, the fall of man and his banishment from the garden of Eden, the suicide of young Werther, and the death of us all. This alteration in proportion is due to Egoyan’s style and narration. Distance, duration, and movement in cinematography, color, light, and composition in mise-en-scène, and music, voice-over, and montage articulate the experience of loss. It is further expressed and exemplified by fragmented narration which coalesces several temporal levels together, bears epistemic ambiguity, focalizes into multiple perspectives without embracing any particular perspective, and halts narration in the traditional sense. In brief, the central event in the film becomes something larger than it is due to the expressed emotion attached to it. The interaction between the story world and the higher levels of discourse gives birth to a full-bodied, rich, and original epic of loss.

Although all human experience is temporal, the experience of loss is temporal in a peculiar sense. It is temporal in the sense that it is born from a reflection on the difference between temporal levels rather than just the passive, pre-reflective processes of anticipation and remembrance which characterize human experience. To Martin Heidegger, time is born from the experience of the distance between the present moment and the future moment of one’s death. In the same way one could argue that loss is born from the experience of the distance between the moment before loss, the moment of loss, and the moment after, all of which, essentially, coalesce in The Sweet Hereafter. While the experience of loss requires time, time seems to always entail loss: it is not possible for one to exist without always losing a moment, a chance, an alternative path, another set of possible outcomes. In both Exotica and The Sweet Hereafter, Egoyan presents a non-classical view of time and reality in which first the distinction between simultaneity and succession is obfuscated and second the reality itself is uncovered as ambiguous. The present either vanishes entirely and is replaced by the process of becoming or, alternatively, the present covers everything in time. In the former case, there is nothing but the process of becoming; reality is in a constant state of flowing as Heraclitus thought. The width of the presence -- the horizontal co-existence of the past, the present, and the future -- equals this process of becoming. As a result, reality itself becomes something ambiguous; rather than just saving the notion of ambiguity to human perception of reality, Egoyan’s ambitious project of articulating, expressing, and exemplifying the experience of loss seems to disclose reality as ambiguous in itself. This might, however, only be due to the fact that in the Egoyan universe there is no distinction between reality in itself, human perception, and what might be called the human reality.

If time is “the very foundation of cinema,” [17] as Andrei Tarkovsky argues, then Egoyan ventures into the essence of film. The Sweet Hereafter might be many things -- a beautiful parable, an elegy of grief, an epic of loss, an intellectually intriguing work of art, a moving tale, an example of original narration and cinematic intuition -- but it is perhaps, above all, an expression of the great powers and capabilities of the seventh art. Never coming close to the mere act of telling a tale, the film always reflects on itself and rather depicts a tale. It is this depiction, or sculpting in time, where lie the deepest truths of cinema. In synthesis of different forms of art (music, written fiction, poetry), cinema exceeds the mere act of combination and becomes something greater than the sum of its parts. The Sweet Hereafter never reduces into the text which is, at least, a sign of it being a good film.

When Nicole walks away from Billy’s children in the final scene of The Sweet Hereafter, executed with one long take, she steps out of the world of childhood onto the verge of a new world of destruction, which is also the moment when Egoyan’s film does something that escapes words and is completely unexpected. Rather than ending the film with the latest temporal level, perhaps showing the people overcoming their grief or learning to live with it, Egoyan has an essentially cinematic stroke of genius in returning to the night before the accident. Not a romantic flashback to the age of innocence, this decision comes across rather as a flash of the absence of sweetness, as an anticipation of things to come. As Nicole walks farther from the children, she stops by the window. In a brief moment, a bright light flashes before her, presumably from the car of her father who is coming to take her away to their secret place of incestuous love. Egoyan is able to charge extreme amount of emotion to this simple, mundane moment which becomes something surreal, something above the everyday level of things. It is as if the final shot carried grief for something that had not yet happened. It is a moment of temporal width, a moment when reality becomes and shows its vague depth. The past has become a part of the future and vice versa. The brief flash of light is as though a symbol for the suffering to come; it is a sign of death; it is the flash of the sweet hereafter. It is something irreducible and inexplicable. A message from the art of light. It is something truly cinematic and very worthy of anniversary celebration.

Notes:

[1] Atom Egoyan says this in the documentary Formulas for Seduction: the Cinema of Atom Egoyan (1999). The documentary, which is really weak as a whole (read: I am not recommending it), is available in the Artificial Eye Atom Egoyan Blu-Ray Box Set.

[2] See Dillon 2003, especially.

[3] May & Ferri 2002, 133-5.

[4] See Dillon 2003 and Weese 2002.

[5] Egoyan makes such a self-reflective observation in this interview.

[6] Dillon 2003, 228.

[7] Ibid. 227.

[8] Tarkovsky 1986, 121.

[9] Gruben 2007, 267.

[10] May & Ferri 2002, 132.

[11] Ibid. 133.

[12] Dillon 2003, 228.

[13] Gruben 2007, 271.

[14] May & Ferri 2002, 135-6.