#mademoiselle Moreau

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Villains with pink.

#one guy#poptropica#poptropica villains#poptropica dr. hare#dr. hare#24 carrot island#betty jetty#super power island#Gretchen Grimlock#poptropica cryptids island#mademoiselle moreau#mystery Train Island#poptropica scheherazade#arabian nights island#Poptropica little witchy#Poptropica fairy tale island#Poptropica red queen#poptropica home island

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eh why not share this old edit I did like two years ago along with the original

#poptropica#mademoiselle moreau#my edits#it was to make her colors slightly more nicer on the eyes#just a concept#also added eyeshadow for fun

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mademoiselle Frenchie Moreau!? Is that you?

#poptropica#mademoiselle moreau#? maybe#don’t take this seriously#mystery train island#since her existence is technically an old spoiler

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Which in-game Poptropica villain is your favorite >:)

You just had to spite me with "in-game". Nobody is ever beating Lieutenant Rogers in my heart. Ever.

ANYWAYS Mademoiselle Moreau girlboss

#ask#anonymous#Poptropica#Poptropica villains#mademoiselle Moreau#Mademoiselle Moreau Poptropica#mystery train island#lieutenant rogers poptropica#lieutenant rogers#poptropica graphic novels

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

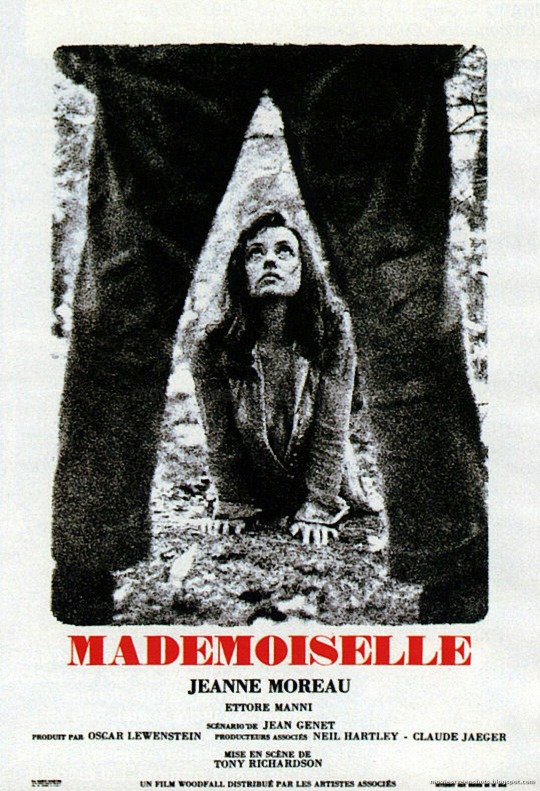

Mademoiselle (1966) dir. Tony Richardson

#mademoiselle#filmedit#movieedit#moviegifs#filmgifs#dailyflicks#fyeahmovies#classicfilmblr#classicfilmsource#uservienna#cinemaspast#dailyworldcinema#movies#film#mine#1960s#french cinema#jeanne moreau#keith skinner#tony richardson

569 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mademoiselle(Tony Richardson, 1966)

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

and when i say kevjean??? then what????

(second pic says “it is you who i love” last pic says “don’t be a fool about this” , “i love you” , & “you come with me”)

#mine#kevjean#kevin day#jean moreau#the foxhole court#the sunshine court#the golden raven#the raven king#the kings men#bastille#mademoiselle and the nunnery blaze#all for the game#aftg#tsc#nora sakavic

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

#gif#movie#mademoiselle#1966#tony richardson#jeanne moreau#ettore manni#snake#tentation#black and white movies#60s movies#60s aesthetic

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jeanne Moreau in "Mademoiselle" (1966) Directed by Tony Richardson

#jeanne moreau#tony richardson#film#cinema#movie stills#movie#film frames#cinematography#films#movies#david watkin

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hottest Poptropica villain

Because I'm an incredibly shameless person, I will put effort into answering this question.

This is why God left us /hj

Out of the female villains, I'm gonna say Daphne Dreadnaught.

Out of the male villains, I'm gonna say... it's a tie between Cactus von Garlic and Ringmaster Raven. Those two are complete opposites :p

#wowie wow wow#ask#poptropica#poll#poptropica spy island#director d#super power island#poptropica copy cat#Nabooti Island#vince graves#astro knights island#poptropica mordred#binary bard#poptropica black widow#counterfeit island#mystery train Island#mademoiselle moreau#ghost story island#daphne dreadnaught#vampire's curse island#cactus von garlic#monster carnival island#ringmaster raven#poptropica survival island#myron van buren#poptropicon island#tessa turncoat#poptropica octavian#poptropica graphic novels#poptropica rumpelstiltskin

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

“When I grow up, I know exactly how I want my hair to look. Like Anouk Aimee's in La Dolce Vita." From "Introducing Rock 'N' Roll's Lady Raunch: Patti Smith" by Amy Gross, Mademoiselle, September 1975

“I was so fucked-up-looking in school, but it just didn't matter. Besides me wanting to be an artist, I wanted to be a movie star. I don't mean like an American movie star. I mean like Jeanne Moreau or Anouk Aimee in La Dolce Vita. I couldn't believe her in those dark glasses and that black dress and that sports car. I thought that was the heaviest thing I ever saw. Anouk Aimee with that black eye. It made me always want to have a black eye forever. It made me want to get a guy to knock me around. I'd always look great. I got great sunglasses.” From “Patti Smith: Can You Hear Me Ethiopia?" by Scott Cohen, Circus Magazine, December 1976

Born on this day ninety-two years ago: that most feline and inscrutable of mid-twentieth century French actresses, Anouk Aimée (née Nicole Françoise Florence Dreyfus, 27 April 1932). She’s a haunting, sensual and Garbo-like presence in the glory days of European art cinema. My favourite performances by Aimée: Les Amants de Montparnasse (1958), La Tête contre les murs (1959), La Dolce Vita (1960) – unforgettable as the most elegant jaded rich nymphomaniac in cinema history (pictured)! – Lola (1961), Model Shop (1968) and Justine (1969). But hell, I also love Aimée as the cruel lesbian queen in trashy sword-and-sandal biblical epic Sodom and Gomorrah (1962), with her voice dubbed by an American actress! It’s fascinating to contemplate that at the height of her international fame in the sixties, Hollywood considered Aimée for two high profile roles: the part played by Faye Dunaway in The Thomas Crown Affair (1968) – and The Baroness in The Sound of Music (1965)!

#anouk aimée#anouk aimee#french actress#french cinema#european art cinema#la dolce vita#patti smith#nouvelle vague#french new wave#art cinema

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

17th November 1765 saw the birth of Étienne Jacques Joseph Alexandre MacDonald at Sedan France.

This is rather a long piece about, in my opinion, a very intersting Franco-Scot. The first photo is on display at The Palace of Versaille, showing how highly the French thought/think of him.

Scots have had a long history with France, and it did not end with the French Revolution, although no doubt some may very well have become victims of the era and lost their lives and lands, others like Franco-Scot, Étienne MacDonald, would go on to show that their devotion was to France rather than to the ruler.

In 1784 the British Parliament passed the Act of Amnesty which pardoned all Jacobites, but despite this, Étienne’s father Neil MacDonald, who helped Charles Edward Stuart escape to France after the ‘45, never returned to Scotland on account of his poor health and he died in poverty 4 years later.

By this time his son Jacques MacDonald, as he was known, had already begun a promising military career in the French army, and that he would later be central to the cataclysmic events of the French Revolution, Napoleonic Wars and Restoration of the Bourbon Monarchy in France..

MacDonald began his French military career in 1786 by joining the ‘Dillon Regiment’, which was primarily composed of Scottish and Irish Jacobite exiles. The regiment remained loyal to Louis XVI at the outbreak of the revolution in 1789, which led not only to its disbandment in 1791, but the execution of its Colonel, Arthur Dillon, by guillotine in 1794. MacDonald on the other hand was personally loyal to the revolution, marrying a Mademoiselle Jacob, whose father was an enthusiastic supporter of the changes that were taking place in French society.

At the outbreak of war in 1792 MacDonald continued to serve in the new army and was offered a prestigious position as aide-de-camp to General Dumouriez. He distinguished himself at the Battle of Jemappes,and he was also present alongside Dumouriez at the Battle of Valmy. The victory of the French volunteer army at Valmy was a significant turning point in the Revolutionary Wars and it compelled France to formally abolish the monarchy shortly afterwards. By 1793 MacDonald had risen to the rank of Colonel and then refused to desert the Revolutionary Army when Dumouriez defected to the enemy. As a reward for this loyalty he was given the command of a Brigade.

By 1797 he had become a General of a Division and joined the French Army in Italy. He occupied Rome, became the governor of the city, defeated the Austrian Army of General Mack before reorganising the Kingdom of Naples into the Parthenopaean Republic. In 1801 he became the French ambassador to Denmark but did not enjoy the politics of diplomacy and he later asked to be recalled.

After returning to France, it was clear the French Republic was in crisis. Its armies were being outfought by a coalition of empires determined to destroy revolutionary ideas. Internally, France had become politically unstable and a coup d’etat was planned to overthrow the government. It was decided that a general should be part of the coup to ensure the support of the army. The conspirators first choice, General Joubert, was killed in Italy before he could be asked. General Moreau was then asked, but he refused to be a figurehead of the coup. The decision then came to MacDonald himself, and like Moreau before him, he also refused. The next choice for the conspirators was Napoleon Bonaparte, who accepted the offer and took power backed by the army and MacDonald.

Following these events, MacDonald took command of the French Army of Switzerland, an important position that linked the French armies fighting in Germany with those in Northern Italy. He fell out of favour with Napoleon after associating with his rival, General Moreau. This led to Napoleon overlooking MacDonald in his first allocation of Marshals of France around 1805.

The Napoleonic Wars continued from 1805 but MacDonald still remained without a position in the French Army. It wasn’t until 1809 that Napoleon finally allocated command of a Corps to MacDonald, also giving him the responsibility of being a military adviser to Napoleon’s adopted son, Prince Eugene de Beauharnais, the Viceroy of Italy.

The highlight of MacDonald’s career soon followed at the Battle of Wagram in 1809. MacDonald was in command of the reserve corps, and at the height of the battle he was ordered to attack the Austrian centre to relieve pressure on the other parts of the French line. Forming his 8,000 soldiers into an unusual column formation that resembled a large hollow rectangle, MacDonald advanced and successfully held off three Austrian cavalry charges. Under concentrated Austrian cannon and musket fire his Corps suffered 50% casualties and could not advance any further. MacDonald recognised that the Austrians were now disorganised because of his attack, and he ordered the French Guard Cavalry to attack and seize the opportunity to destroy the Austrian centre. General Walther, commander of the Guard Cavalry, refused to take an order from anyone other than Napoleon himself and his cavalry remained stationary. This crucial delay resulted in a lost opportunity to capitalise on the gains that MacDonald had made. Both MacDonald and Napoleon were later furious with General Walther for this decision, Napoleon even being moved to say that it was the first time his cavalry had ever let him down.

Despite the failure of the Guard Cavalry, MacDonald’s attack had sufficiently occupied the attention of the Austrians to allow the French to successfully conduct a general attack on other parts of the line. The French had won the battle and Napoleon rode directly to MacDonald and upon embracing him said,

“General MacDonald, Let us be friends henceforth. You have behaved valiantly and have rendered me the greatest services throughout the entire campaign. On the battlefield of your glory, where I owe you so large a part of yesterday’s success, I make you a Marshal of France. You have long deserved it.”

MacDonald was the first French Marshal to be created on the field of battle and he graciously asked Napoleon to let the rewards be distributed equally among the men of his corps. Napoleon said that he could not refuse him and in further recognition of his services he soon afterwards awarded MacDonald the Grand Eagle of the Legion of Honor, the title of Duke of Taranto and 60,000 francs.

Following the Battle of Wagram, MacDonald was made the Governor of Gratz, a role which he undertook with such distinction that the city wanted to pay him 200,000 Francs when he left, an offer which he refused. MacDonald was then made the Commander of the French army in Catalonia, and also the Governor-General of the principality. MacDonald had serious objections to the manner in which the French were fighting the war in Spain, which had degenerated into a brutal war between French regulars and Spanish guerrilla fighters. Putting aside his objections, he took up the role and met with mixed success. He was defeated at the Battle of Pla in 1811, but later took Figueras after a 4 month siege. Both of these battles were typical of the Spanish War in which large numbers of French troops and resources were tied down by relatively small numbers of elusive Spanish troops. Following the siege of Figueras, MacDonald experienced a sever case of gout, followed by fever. He asked to be transferred and returned to Paris, unable to walk without the assistance of crutches.

MacDonald recovered in time to be present at the French invasion of Russia in 1812, in which he commanded the X Corps and the left wing of the Grand Army. This Corps was a multinational formation, comprising Poles, Bavarians, Westphalians and Prussians. Initially the invasion met with little resistance and MacDonald was able to defend the flank of Napoleon’s invasion by routing a Russian Army near Riga in present day Latvia. Despite his Prussian infantry playing a major part in the victory, MacDonald started to become suspicious of them after they less than enthusiastically undertook his order to pursue and capture the defeated Russians.

After a series of battles Napoleon went on to capture Moscow, which had been completely abandoned by the Russians. After Moscow had been under occupation for three days, the city was set alight by a handful of Russians who had stayed behind to prepare the trap. The resulting fire destroyed 80% of the mostly wooden city and came as a terrible shock to the morale of the French army. Tsar Alexander continued to ignore all calls for surrender from Napoleon and with the French army now camped in a ruined city Napoleon had no choice but to retreat, which the Grand Army began in October 1812.

In November 1812 Napoleon learned that there had been a coup against his rule in Paris. Leaving Marshal Murat in command he left the army had hurried back to Paris to deal with the political problems that had arisen. Marshal Murat also later abandoned the army to save his Kingdom of Naples, leaving Napoleon’s adopted son the Viceroy of Italy, Prince Eugène de Beauharnais in command. MacDonald had previously been a close colleague and military mentor to de Beauharnais and they had worked closely together to secure the French victory at Wagram two years previously.

The French Army had initially invaded Russia with an Army of 450,000 men, but now the remaining 150,000 had the unenviable task of retreating from Moscow through a vicious Russian winter and temperatures of -40c. As the pursuing Russians picked away at the remnants of what was once the largest army in European history, MacDonald was trying to deal with problems within his own Corps. During the retreat he was shocked to discover that General Yorck and the Prussians under his command had defected from MacDonald’s Corps en masse, secretly leaving the army during the night. MacDonald wrote contemptuously of these Prussian’s in his memoirs but he spoke highly of the Polish, Bavarian and Westphalian soldiers of his Corps, who he described as serving faithfully, courageously and with distinction.

During the final stages of the retreat, Marshal Murat requested the advice of MacDonald on how the French Army should proceed. MacDonald recommended abandoning all territory east of the Oder River, holding the line along the river and waiting for the fresh troops being assembled in France. His advice was ignored and the retreat would continue. The total losses during the whole campaign amounted to 380,000 men, with just 35,000 Frenchmen making it home from the initial force.

MacDonald eventually did make it back to France, despite having his travelling expenses of 12,000 francs stolen from him on his way through Prussia. He received a frosty reception from Napoleon when he eventually returned to Paris. The Emperor had been led to believe that the Prussians had deserted the army because MacDonald had treated them badly. In his memoirs MacDonald also suggests that this less than cordial meeting was because Napoleon felt resentment towards his plan of abandoning all territory East of the Oder River. MacDonald left the meeting bemused and with understandable disdain that his services and devotion were met with such a lack of appreciation. However some days later, news had reached Napoleon that the Prussian Government had fully accepted the actions of their soldiers, implying that the desertions had nothing to do with the way MacDonald treated them and everything to do with an imminent Prussian declaration of war against France. He was subsequently summoned by Napoleon, who admitted that he had been misled regarding MacDonald’s actions in Russia, and that he did in fact act wisely in his dealings with the Prussian soldiers of his command.

By 1813 MacDonald was back in the field, joining the 200,000 largely inexperienced soldiers that were sent to link up with the remnants of the French Army in central Europe. A new coalition of powers, including Prussia, had rallied together to defeat Napoleon following his disastrous invasion attempt of Russia.

In the aftermath of the Battle of Leipzig, MacDonald and Prince Poniatowski of Poland were given command of a desperate rear guard action. Hopelessly outnumbered, MacDonald and Poniatowski made a fighting withdrawal through Leipzig towards a bridge across the river Elster. Learning that the bridge had in fact been destroyed by the French in the confusion of the retreat, Poniatowski attempted to swim across the river on horse back. He made it across, but the bank was steep and his horse fell with exhaustion, drowning Poniatowski in the river. As the front disintegrated MacDonald found himself being followed by a crowd of his men desperate to escape the approaching enemy. Seized by his aide-de-camp, MacDonald found a makeshift bridge of wooden logs that had been hastily constructed by a resourceful French engineer. MacDonald dismounted and began walking across the flimsy construction, but as his men began to follow him the bridge began to shake, causing MacDonald to fall into the river. Luckily he fell close enough to the shore that his feet could reach the bottom of the river but he struggled to get out because of the loose soil and steep embankment. Enemy skirmishers fired on him at point blank range before they were scared off by French musket fire on the opposing river bank.

MacDonald barely escaped with his life and upon reaching the top of the riverbank he turned to see whole companies of his men falling into the river, crying out “Marshal! Save your men, save your children!” as they were swept away to their deaths. Overcome with rage and frustration at being unable to save his men, he sat on the riverbank and wept. MacDonald recalls in his memoirs that this scene traumatised him for years after the event and that he could often hear the voices of the screaming men ringing in his ear.

MacDonald was furious with Napoleon for allowing the whole disaster to happen and he initially refused to even meet with the Emperor. Rumors subsequently spread through the army that MacDonald had been killed while crossing the river, but he survived and eventually made his way to Cologne to rebuild his shattered Corps. He remained one of the central commanders of the now hopeless French efforts to keep the allied powers from entering France. Ultimately Paris was captured by the allies in 1814. As Napoleon raced to Fontainebleau it was clear the soldiers were no longer willing to follow Napoleon on what was obviously a lost cause. MacDonald was encouraged to approach Napoleon on behalf of the army, making him aware that the soldiers wanted peace. MacDonald made these points to Napoleon at Fontainebleau, expecting the Emperor to fly into a violent rage, but was surprised when Napoleon reacted quite calmly to the fall of Paris and the reality that the starving and worn out remnants of the army could no longer go on fighting. Napoleon hailed MacDonald as a “good and honorable man” for his frankness and openness. He then turned to all those in the room and announced that he would abdicate the throne in favour of his son. Napoleon sat and wrote out his abdication, rewriting the draft two or three times. Then as Napoleon dismissed them for the evening, he threw himself on the sofa, slapped his leg with his hand and proclaimed, “Nonsense, gentlemen! Let us leave all that alone and march tomorrow, we shall beat them!” No doubt bemused by this departure from reality, MacDonald reiterated everything he had already said about the perilous state of the army. The Marshals, led by Marshal Ney then decided to mutiny against Napoleon to prevent further pointless bloodshed. Napoleon eventually yielded to the inevitable and MacDonald, along with Caulaincourt and Ney, left to personally negotiate the terms of surrender with Tsar Alexander of Russia on behalf of Napoleon.

MacDonald was to write that Tsar Alexander was gracious in victory and spoke respectfully of the French. MacDonald notes in his memoirs that aside from Marshal Ney, who was unstable and aggressive, Tsar Alexander’s conciliatory tone was reciprocated by the French Marshals. The Prussians were far less accommodating and were quick to remind the French that they were the scourge of Europe, immediately demanding compensation and providing none of the compliments that the Tsar had generously offered the French army. The other main member of the allied coalition was Austria, who was willing to allow Napoleon’s wife and son to keep their titles, but on the condition that they were prohibited from ever attaining power in France. Britain refused to negotiate at all, claiming that they did not recognise Napoleon as a legitimate authority, which was probably just as well for Napoleon who half heartedly said that you could “never trust a MacDonald within sound of bagpipes.”

Following the exchange, the allied powers were keen to ensure that the Marshals submitted to the new order. This would guarantee that the French Army would also obediently submit to the provisional government. Marshal Ney immediately submitted, but MacDonald and Caulaincourt remained loyal to Napoleon until the formal ratification of the treaty, after which time MacDonald wrote a simple statement to the provisional government saying that “being released from my allegiance by the abdication of the Emperor Napoleon, I declare that I conform to the Acts of the Senate and the Provisional Government.” This act of dignified defiance infuriated the ever scheming French statesmen de Talleyrand, whose face was said to turn pale before almost bursting with rage when MacDonald politely refused to submit until the formal ratification of the treaty.

MacDonald returned to Fontainbleu to call upon Napoleon. On the morning of the 13th of March 1814, MacDonald entered to find a despondent Napoleon wearing his dressing gown and slippers, with his head buried in his hands and his elbows on his knees. He did not stir when MacDonald entered the room, but on prompting from Caulaincourt he appeared to wake from a dream and MacDonald found him to have a sickly yellow-green complexion. Napoleon apologised and said that he had been sick all night, later evidence suggests that it was likely Napoleon had taken an overdose of opium in an attempt to try and sleep after the emotionally exhaustive events of recent months.

Again, Napoleon sat in the room, remained silent for a period of time before turning to MacDonald and saying,

“Duke of Tarentum, I cannot tell you how touched and grateful I am for your conduct and devotion. I did not know you well; I was prejudiced against you. I have done so much for, and loaded with favours, so many others, who have abandoned and neglected me; and you, who owed me nothing, have remained faithful to me I appreciate your loyalty all too late, and I sincerely regret that I am no longer in a position to express my gratitude to you except by words.”

Napoleon noted that MacDonald had always had a generous manner, never accepting large amounts of money while being an impartial ruler who brought justice wherever he commanded. Napoleon then implored MacDonald to accept the sword of the former leader of the Mamelukes, Murad Bey, which had been captured in Egypt in 1798 and worn by Napoleon at the Battle of Mount Tabor in 1799. MacDonald accepted the gift as a sign of Napoleon’s friendship and the two commanders emotionally embraced each other. It was the last time that MacDonald and Napoleon would ever meet.

I think I’ve taken this as far as I want to for this lengthy post, but there is much more to read in part two just click here!

When he died in 1840 at the age of 70 he was given a state funeral and buried in the Pere Lachaise cemetery in Paris. Pere Lachaise is where the great and good of early nineteenth century Paris were buried. 14 of Napoleon’s 26 Marshals are buried there.

Somhairle MacGill-Eain/ Sorley MacLean, wrote a poem about Marshal Étienne Jacques MacDonald of France, I shall post that later.

There are more pics in the article I took this from here https://sonofskye.wordpress.com/.../marshal-etienne.../

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mademoiselle (1966)

#mademoiselle#filmedit#movieedit#jeanne moreau#ettore manni#keith skinner#tony richardson#moviegifs#filmgifs#fyeahmovies#dailyflicks#classicfilmblr#uservienna#cinemaspast#dailyworldcinema#1960s film#classic french film#french cinema#mine

229 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mademoiselle(Tony Richardson, 1966)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

its home is but a hovel in the mire of the reservoir, cavernous and echoing with the howls of its experiments and the mournful cries of itself. the wails of whales are not unlike its own. the sludge of its enzymes covers the walls in a thick and pulsating goo, some dripping from the ceilings into slimy stalactites. one would have to hold some sort of death wish to come here voluntarily. a screw loose. mad as a hatter. nutty as a fruitcake. it likes fruitcake. but the thought of guests nonetheless titillates moreau, so when the woman presents herself unannounced and thoroughly out of place in such a pitiful residence, it works double time to ensure her needs are met. not quite swanning around the tunnels but rather trudging at a hurried pace, the sounds of its feet like wet jelly slapping upon the rocky floor. ❛ c-can i interest you in tea ? ❜ it waves an amphibian paw over a steaming vessel, more vat than teapot, the brew inside pungent and bubbling. those weak of stomach, do not look too closely. perhaps recognising its beverage's inadequacy before it can be pointed out, beady eyes search frantically for a more suitable alternative. spotting its bedside television remnants of cheese, it deviates.

❛ or . . . or is le fromage more your taste ? ❜ it has the urge to say mademoiselle, recalling a past life trying to court beautiful women with arrays of gifts and delicacies. the memories pile thick in its throat and it guffaws, unsavourily depositing a phlegmy pile at its feet. it clasps its own hands in shame, head habitually lowered so as not to meet her gaze.

@sacrificialmaiid. ♡

#sacrificialmaiid#i feel i should tag this with a warning he's Foul...#erm i'm imagining maybe alcina sent her for an errand?? she needs something from him???#cause u know SHE's not setting foot in there lol but#if that doesn't work / you want to plot something else / i change some bits lmk!!!#tea party with moreau <3#╰ ✧ . * S. MOREAU. / loathsome locust eater. even a worm will turn.#MOREAU : WRITING.

3 notes

·

View notes