#luftwaffe glider

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

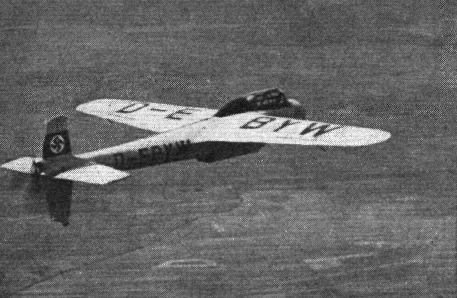

DFS 230 glider in flight over Italy, 1943, possibly on the Mussolini rescue mission. Junkers Ju 87D Stuka dive bomber in background. Glider is probably being towed by a Junkers Ju 52/3m. For more, see my Facebook group - Eagles Of The Reich

#germany#ww2#luftwaffe#ww2 aircraft#german glider troops#german glider#luftwaffe glider#ww2 gliders#junkers#ju 87#ju 87b#stuka#dfs 230#third reich#nazi germany#ju 52

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

14 September 1941. Messerschmitt Me321 heavy assault transport gliders of Staffel [GS] 1 were used for the first time in an operational air assault on Saaremaa Island in the Baltic, as part of an attempt to capture the fort of Kübarsaare.

@ron_eisele via X

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

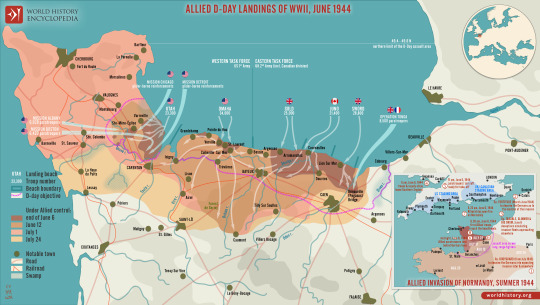

D-Day was 80 years ago today!

D-Day was the first day of Operation Overlord, the Allied attack on German-occupied Western Europe, which began on the beaches of Normandy, France, on 6 June 1944. Primarily US, British, and Canadian troops, with naval and air support, attacked five beaches, landing some 135,000 men in a day widely considered to have changed history.

Where to Attack?

Operation Overlord, which sought to attack occupied Europe starting with an amphibious landing in northwest France, Belgium, or the Netherlands, had been in the planning since January 1943 when Allied leaders agreed to the build-up of British and US troops in Britain. The Allies were unsure where exactly to land, but the requirements were simple: as short a sea crossing as possible and within range of Allied fighter cover. A third requirement was to have a major port nearby, which could be captured and used to land further troops and equipment. The best fit seemed to be Normandy with its flat beaches and port of Cherbourg.

The Atlantic Wall

The leader of Nazi Germany, Adolf Hitler (1889-1945), called his western line of defences the Atlantic Wall. It had gaps but presented an impressive string of fortifications along the coast from Spain to the Netherlands. Construction of gun batteries, bunker networks, and observation posts began as early as 1942.

Many of the German divisions were not crack troops but inexperienced soldiers, who were spending more time building defences than in vital military training. There was a woeful lack of materials for Hitler's dream of the Atlantic Wall, really something of a Swiss cheese, with some strong areas, but many holes. The German army was not provided with sufficient mines, explosives, concrete, or labourers to better protect the coastline. At least one-third of gun positions still had no casement protection. Many installations were not bomb-proof. Another serious weakness was naval and air support. The navy had a mere 4 destroyers available and 39 E-boats while the Luftwaffe's (German Air Force's) contribution was equally paltry with only 319 planes operating in the skies when the invasion took place (rising to 1,000) in the second week.

Neptune to Normandy

Preparation for Overlord occurred right through April and May of 1940 when the Royal Air Force (RAF) and United States Air Force (USAAF) relentlessly bombed communications and transportation systems in France as well as coastal defences, airfields, industrial targets, and military installations. In total, over 200,000 missions were conducted to weaken as much as possible the Nazi defences ready for the infantry troops about to be involved in the largest troop movement in history. The French Resistance also played their part in preparing the way by blowing up train lines and communication systems that would ensure the defenders could not effectively respond to the invasion.

The Allied fleet of 7,000 vessels of all kinds departed from English south-coast ports such as Falmouth, Plymouth, Poole, Portsmouth, Newhaven, and Harwich. In an operation code-named Neptune, the ships gathered off Portsmouth in a zone called 'Piccadilly Circus' after the busy London road junction, and then made their way to Normandy and the assault areas. At the same time, gliders and planes flew to the Cherbourg peninsula in the west and Ouistreham on the eastern edge of the planned landing. Paratroopers of the 82nd and 101st US Airborne Division attacked in the west to try and cut off Cherbourg. At the eastern extremity of the operation, paratroopers of the 6th British Airborne Division aimed to secure Pegasus Bridge over the Caen Canal. Other tasks of the paratrooper and glider units were to destroy bridges to impede the enemy, hold others necessary for the invasion to progress, destroy gun emplacements, secure the beach exits, and protect the invasion's flanks.

The Beaches

The amphibious attack was set for dawn on 5 June, daylight being a requirement for the necessary air and naval support. Bad weather led to a postponement of 24 hours. Shortly after midnight, the first waves of 23,000 British and American paratroopers landed in France. US paratroopers who dropped near Ste-Mère-Église ensured this was the first French town to be liberated. From 3.00 a.m., air and naval bombardment of the Normandy coast began, letting up just 15 minutes before the first infantry troops landed on the beaches at 6.30 a.m.

The beaches selected for the landings were divided into zones, each given a code name. US troops attacked two, the British army another two, and the Canadian force the fifth. These beaches and the troops assigned to them were (west to east):

Utah Beach - 4th US Infantry Division, 7th US Corps (1st US Army commanded by Lieutenant General Omar N. Bradley)

Omaha Beach - 1st US Infantry Division, 5th US Corps (1st US Army)

Gold Beach - 50th British Infantry Division, 30th British Corps (2nd British Army commanded by Lieutenant-General Miles C. Dempsey)

Juno Beach - 3rd Canadian Infantry Division (2nd British Army)

Sword Beach - 3rd British Infantry Division, 1st British Corps (2nd British Army)

In addition, the 2nd US Rangers were to attack the well-defended Pointe du Hoc between Utah and Omaha (although it turned out the guns had never been installed there), while Royal Marine Commando units attacked targets on Gold, Juno, and Sword.

The RAF and USAAF continued to protect the invasion fleet and ensure any enemy ground-based counterattack faced air attack. As the Allies could put in the air 12,000 aircraft at this stage, the Luftwaffe's aerial fightback was pitifully inadequate. On D-Day alone, the Allied air forces flew 15,000 sorties compared to the Luftwaffe's 100. Not one single Allied aircraft was lost to enemy fire on D-Day.

Packing Normandy

By the end of D-Day, 135,000 men had been landed and relatively few casualties were sustained – some 5,000 men. There were some serious cock-ups, notably the hopeless dispersal of the paratroopers (only 4% of the US 101st Air Division were dropped at the intended target zone), but, if anything, this caused even more confusion amongst the German commanders on the ground as it seemed the Allies were attacking everywhere. The defenders, overcoming the initial handicap that many area commanders were at a strategy conference in Rennes, did eventually organise themselves into a counterattack, deploying their reserves and pulling in troops from other parts of France. This is when French resistance and aerial bombing became crucial, seriously hampering the German army's effort to reinforce the coastal areas of Normandy. The German field commanders wanted to withdraw, regroup and attack in force, but, on 11 June, Hitler ordered there be no retreat.

All of the original invasion beaches were linked as the Allies pushed inland. To aid thousands more troops following up the initial attack, two artificial floating harbours were built. Code-named Mulberries, these were located off Omaha and Gold beaches and were built from 200 prefabricated units. A storm hit on 20 June, destroying the Mulberry Harbour off Omaha, but the one at Gold was still serviceable, allowing some 11,000 tons of material to be landed every 24 hours. The other problem for the Allies was how to supply thousands of vehicles with the fuel they needed. The short-term solution, code-named Tombola, was to have tanker ships pump fuel to storage tanks on shore, using buoyed pipelines. The longer-term solution was code-named Pluto (Pipeline Under the Ocean), a pipeline under the Channel to Cherbourg through which fuel could be pumped. Cherbourg was taken on 27 June and was used to ship in more troops and supplies, although the defenders had sunk ships to block the harbour and these took some six weeks to fully clear.

Operation Neptune officially ended on 30 June. Around 850,000 men, 148,800 vehicles, and 570,000 tons of stores and equipment had been landed since D-Day. The next phase of Overlord was to push the occupiers out of Normandy. The defenders were not only having logistical problems but also command issues as Hitler replaced Rundstedt with Field Marshal Günther von Kluge (1882-1944) and formally warned Rommel not to be defeatist.

Aftermath: The Normandy Campaign

By early July, the Allies, having not got further south than around 20 miles (32 km) from the coast, were behind schedule. Poor weather was limiting the role of aircraft in the advance. The German forces were using the countryside well to slow the Allied advance – countless small fields enclosed with trees and hedgerows which limited visibility and made tanks vulnerable to ambush. Caen was staunchly defended and required Allied bombers to obliterate the city on 7 July. The German troops withdrew but still held one-half of the city. The Allies lost around 500 tanks trying to take Caen, vital to any push further south. The advance to Avranches was equally tortuous, and 40,000 men were lost in two weeks of heavy fighting. By the end of July, the Allies had taken Caen, Avranches, and the vital bridge at Pontaubault. From 1 August, Patton and the US Third Army were punching south at the western side of the offensive, and the Brittany ports of St. Malo, Brest, and Lorient were taken.

German forces counterattacked to try and retake Avranches, but Allied air power was decisive. Through August 1940, the Allies swept southwards to the Loire River from St. Nazaire to Orléans. On 15 August, a major landing took place on the southwest coast of France (French Riviera landings) and Marseille was captured on 28 August. In northern France, the Allies captured enough territory, ports, and airfields for a massive increase in material support. On 25 August, Paris was liberated. By mid-September, the Allied troops in the north and south of France had linked up and the campaign front expanded eastwards pushing on to the borders of Germany. There would be setbacks like Operation Market Garden of September and a brief fightback at the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944, but the direction of the war and ultimate Allied victory was now a question of not if but when.

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

Erich Hartmann (1922 - 1993)

The most successful fighter pilot in history. In the span of 3 years, Erich "Bubi" Hartmann shot down 352 enemy aircraft.

Erich spend a part of his childhood in China, when things got too politically dangerous, his family moved back to Germany. His mother was one of the first women to pursue flying on glider planes and she often took Erich with him, igniting his love for flying.

After graduating school in 1940, he immediately joined the Luftwaffe and started training as a fighter pilot. In October 1942 he was sent to the Eastern Front, joining the war. Young and impulsive as he was, he didn´t stick to the rules at his first enemy encounter, resulting in a crashed plane. He was assigned as Rottenflieger of Walter Krupinski, another young but already experienced and successful fighter pilot who managed to teach Erich that working as a team is crucial for success and survival.

Within a year he shot down 90 victories, before being shot down himself, but managing to escape Soviet imprisonment.

Im March 1944 he shot down his 200th victory, by August his 300th.

In late 1944 he was pulled from the Eastern Front to train on the revolutionary new jet fighter Me-262, but in March 1945 he returned to his Geschwader. He declined Adolf Gallands offer to joing JV 44. On the day of the capitulation, 8th May 1945, he shot down his final victory, number 352.

He had the chance to espace to southern Germany but he refused to leave his comrades and the fleeing civilians behind. They started towards the German border on foot and surrendered themselves to US soldiers, but where handed over to the Russians. [There is an interesting comparison to Hans Ulrich Rudel (the most successful Stuka pilot) who also surrendered to Americans who were also supposed to hand him over to the Soviets but refused.]

Erich Hartmann, just 23 years old at the time, was sentenced to 20 years of hard labour under the accusation of war crimes (these "crimes" entailing destroying russian airplanes). Not being allowed a proper trial, there was little he could do to defend himself. He was shifted around to several labour camps (gulags).

During the endless interogations, the Russians tried to get all information about the Me-262, but Hartmann didn´t cooperate. In order to break him, they tried to extort him by not giving him the letters his wife, Ursula, wrote him. She faithfully wrote him everyday. In one of those letters, Hartmann learned that his son had died. But he did not break and he never lost hope.

After more than 10 years, Erich Hartmann was one of the last PoWs to return to Germany, to his wife.

He joined the Luftwaffe in 1956, not because he truly wanted to but because he felt like he had no other option. Erich had always wanted to become a doctor like his brother but all he knew was being a soldier, a pilot.

After his death he was cleared of all war crime accussations.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

WW2 GERMAN LUFTWAFFE TRANSPORT CLASP

WW2 German Luftwaffe Transport and Glider Flying Clasp. We pay top dollar for authentic WW2 German Badges.

#ww2germanbadges#ww2germandaggers#ww2#ww2germanhelmets#wwiigermancollectibles#ww2germanflags#ww2german#ww2germanmilitaria#ww2germanuniforms#ww2germanmedals

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

finnishgermanacesofwwii:

Erich Alfred Hartmann (1922-1993) was the highest scoring ace in the history of military aviation. He fought as a fighter pilot on the Eastern Front during World War II, shooting down 352 Soviet aircraft. Serving with the Luftwaffe, Hartmann flew 1,404 combat missions, engaged the enemy in combat 827 times and was never shot down. Known as “Bubi” or the “Blond Knight”, and to the Soviets as The Black Devil, he was an audacious and determined man with full control of himself and steel nerves. Erich Hartmann was born in Weissach, Württemberg, Germany, on April 19, 1922. His father was Alfred Erich Hartmann and his mother, Elisabeth Wilhelmine Machtholf. As his father was a physician and had been sent to work in China, Erich spent part of his childhood in the Far East. When the Chinese Civil War broke out, they returned to Germany in 1928. In the early 1930s, Erich Hartmann was taught to fly gliders by his mother, who was the first female pilot of Germany. Then, he joined the gliding training program of the future Luftwaffe. In 1939, Erich obtained his pilot’s license, which allowed him to fly powered aircraft. In October 1940, he joined the Luftwaffe where he learned combat techniques and gunnery skills. When his advanced pilot training was completed in January 1942, Hartmann was assigned to a Junkers Ju 87 Stuka at the fighter wing Jagdgeschwader 52 (JG 52), based at Maykop on the Eastern Front in the Soviet Union. Erich was placed under the supervision of some of the Luftwaffe’s most experienced fighter pilots, such as Walter Krupinski, Oberfeldwebel Edmund “Paule” Roßmann, and Alfred Grislawski. Hartmann flew his first combat mission on October 14, 1942, as Edmund “Paule” Roßmann’s wingman, flying a Messerschmitt Bf 109. By August 1944, Erich Hartmann had claimed 301 aerial victories and earned the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds. Erich Hartmann scored his last aerial victory, the 352th, on May 8, 1945. He and the remainder of JG 52 surrendered to United States Army forces and were turned over to the Red Army. In an attempt to pressure him into service with the Soviet-controlled East German air force, he was convicted of fabricated war crimes, a conviction posthumously voided by a Russian court as a malicious prosecution. Hartmann was sentenced to 25 years of hard labor and spent 10 years in various Soviet prison camps and gulags until he was released in 1955. In 1956, Hartmann joined the newly established West German Luftwaffe and became the first Wing Commander of Jagdgeschwader 71 “Richthofen”. Hartmann resigned from the Bundeswehr in 1970, largely due to his opposition to the F-104 Starfighter deployment in the Bundesluftwaffe and the resulting clashes with his superiors over this issue. Then, he worked as a flight instructor. Erich Hartmann died in 1993.

III./JG 52’s commander, Major Hubertus von Bonin, placed Hartmann under Oberfeldwebel Grislawski’s wings. The miner’s son Alfred Grislawski found a particular pleasure in teaching this newcomer the name of the game. He made a few mock combats with Hartmann. This relieved Hartmann of some of his ambitious ideas, but Grislawski had to admit that although Hartmann had a lot to learn about combat tactics, he was quite a talented pilot. The trouble began when they started flying combat missions together. Grislawski immediately noticed that the newcomer was one of those who thought they were going to “shoot together a Knight’s Cross” in no time. During one incident, Hartmann had barely started to leave his place behind Grislawski to go after an I-16, when his earphones seemed to explode: “You bloody idiot! What the hell do you think you’re doing? I’m your leader! Get back in place or I’ll shoot you down myself!” Grislawski kept cursing over the R/T all the way back to base, and when they had landed, the Oberfeldwebel gave the Leutnant a dressing down that he would never forget. Then, in front of the sweating Hartmann, Grislawski turned to his friend “Paule” Rossmann and said: “Oh man, this is too much! What a baby they have sent us! Just look at his face - like a cute little boy!” From then on, Grislawski never addressed Hartmann as anything but Bubi, “little boy”. Hartmann indeed proved to be extremely individualistic, and von Bonin definitely knew what he was doing when he assigned a vigorous and harsh worker’s son like Alfred Grislawski as his teacher. The men at Soldatskaya used to gather around the radio equipment and listen to the R/T communication with amusement when Grislawski and Hartmann were out on combat missions. “Are you so anxious to die, Bubi?” “I’m sorry, sir!” “Don’t you ‘sir’ me, look after your tail instead!” “I’ll nail you for this, Bubi!” “I’m sorry!” “Your mother will be sorry!”* -Erich Hartmann on Hauptmann Alfred Grislawski

“Once I was in a duel with a Red Banner flown Yak-9, and this guy was good, and absolutely insane. He tried and tried to get in behind me, and every time he went to open fire I would jerk out of the way of his rounds. Then he pulled up and rolled, and we approached each other head on, firing, with no hits either way. This happened two times. Finally I rolled into a negative G dive, out of his line of sight, and rolled out to chase him at full throttle. I came in from below in a shallow climb and flamed him. The pilot bailed out and was later captured. I met and spoke with this man, a captain, who was a likeable guy. We gave him some food and allowed him to roam the base after having his word that he would not escape. He was happy to be alive, but he was very confused, since his superiors told him that Soviet pilots would be shot immediately upon capture. This guy had just had one of the best meals of the war and had made new friends. I like to think that people like that went back home and told their countrymen the truth about us, not the propaganda that erupted after the war, although there were some terrible things that happened, no doubt.” -Erich Hartmann on his foes on the Eastern Front

“Once I attacked a flight of four IL-2s and shot one up. All four tried to roll out in formation at low altitude, and all four crashed into the ground, unable to recover since their bomb loads reduced their maneuverability. Those were the easiest four kills I ever had.

However, I remember the time I saw over 20,000 dead Germans littering a valley where the Soviet tanks and Cossacks had attacked a trapped unit, and that sight, even from the air was perhaps the most memorable of my life. I can close my eyes and see this even now. Such a tragedy! I remember that I cried as I flew low over the scene; I could not believe my eyes.

Another time was in May 1944 near Jassy, my wingman Blessin and I were jumped by fighters, he broke right and the enemy followed him down. I rolled and followed the enemy fighter down to the deck. I radioed to my wingman to pull up and slip right in a shallow turn so I could get a good shot. I told him to look back, and see what happens when you do not watch your tail, and I fired. The fighter blew apart and fell like confetti.

However, separate from Krupinski’s crash the day I met him, one event is clear and comical. My wingman on many missions was Carl Junger. He came in for a landing and a Polish farmer with horse cart crossed his path. He crashed into it, killing the horse and the fighter was nothing but twisted wreckage. We all saw it and began thinking about the funeral, when suddenly the debris moved and he climbed out without a scratch, still wearing his sunglasses. He was ready to go up again. Amazing!” -Erich Hartmann on memorable moments

“Then there was the American Mustangs that we both dreaded and anticipated meeting. We knew that they were a much better aircraft than ours; newer and faster, and with a great range. On 23 June 1944. In the defense of Ploesti, Bucharest, and Hungary when the bombers were coming in with heavy fighter escort and “Karaya 1” was commander of I/JG52. B-17s were attacking the railroad junction, and we were formed up. We did not see the Mustangs at first and prepared to attack the bombers. Suddenly four of them flew across us and below, so I gave the order to attack the fighters. I closed in on one and fired, his fighter coming apart and some pieces hit my wings, and I immediately found myself behind another and I fired, and he flipped in. My second flight shot down the other two fighters. But then we saw others and again attacked. I shot down another and saw that the leader still had his drop tanks, which limited his ability to turn. I was very relieved that this pilot was able to successfully bail out. I was out of ammunition after the fight. But this success was not to be repeated, because the Americans learned and they were not to be ambushed again. They protected the bombers very well, and we were never able to get close enough to do any damage. I did have the opportunity to engage the Mustangs again when a flight was being pursued from the rear and I tried to warn them on the radio, but they could not hear. I dived down and closed on a P-51 that was shooting up a 109, and I blew him up. I half rolled and recovered to fire on another of the three remaining enemy planes and flamed him as well. As soon as that happened I was warned that I had several on my tail so I headed for the deck, a swarm of eight Americans behind me. That is a very uncomfortable feeling I can tell you! I made jerking turns left and right as they fired, but they fired from too far away to be effective. I was headed for the base so the defensive guns would help me, but I ran out of fuel and had to bail out. I was certain that this one pilot was lining me up for a strafe, but he banked away and looked at me, waving. I landed four miles from the base; I almost made it. That day we lost half our aircraft; we were too outnumbered and many of the young pilots were inexperienced.” -Erich Hartmann on his encounter with American Pilots

“Goring could not believe the staggering kills being recorded from 1941 on. I even had a man in my unit, someone you also know, Fritz Oblesser, who questioned my kills. I asked Rall to have him transferred from the 8th Squadron to be my wingman for a while. Oblesser became a believer and signed off on some kills as a witness, and we became friends after that.” Goring wasn’t the only one who didn’t believe the claims coming out of Russia. The scores reported were so high, a very strict system was put into place to verify a claim. Not only were pilots required to sign off on their wingmate’s kills but independent ground confirmation was needed as well. When a pilot shot down a plane he would call out over the radio, “Horrido.” At this point pilots or ground crew in the area would look about and see if they saw the event. Most often on the eastern front, there were many on hand to see the victim smash into the ground, and thereby make the kill “official.” A few other things deserve to be mentioned here too… Shared kills were not individually counted by the pilots involved, but they did count toward the squadron’s score as a whole. You won’t see a score of 50.5, for example, for a German Ace. And, points were awarded depending on the number of engines a plane had that was destroyed. 1 point for a single engine, 2 for a twin, 4 for a four-engined bomber and so on. These points were added up and when a pilot achieved a certain number of points he was awarded a medal (the points required for a given medal was much higher on the eastern front than it was on the western front). These points are in no way related to a pilot’s total score of victories. Bringing down a 4-engined bomber may have gotten a pilot 4 points, but it only got him 1 victory. So make no mistake, Erich Hartmann’s score of 352 does not refer to engines but 352 individual planes shot down. -Erich Hartmann on his score.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

A German aviator watches ground crew prepare a glider for the attack on Crete at their airbase in Eleusis, near Athens - May 1941

Note the pile of life jackets being loaded in case of a forced landing over water.

#world war two#worldwar2photos#1940s#wwii#ww2#ww2colourphotos#invasion of Crete#gliders#luftwaffe#aviation

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Exercice de parachutistes allemands depuis un planeur DFS 230 - Campagne d’Italie - Italie - Septembre 1943

Photo : Dr. Stocker

© Bundesarchiv – Bild 101I-569-1579-14A

#WWII#Campagne d'Italie#italian campaign#Luftwaffe#Parachutistes#paratroopers#Entraînement#training#Planeur#glider#DFS 230#Italie#italy#09/1943#1943

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Messerschmitt Me 323 powered glider under attack off Cape Corse, Corsica, by a Martin Marauder Mark I, flown by the Commanding Officer of No. 14 Squadron RAF, Wing Commander W Maydwell. The aircraft crash-landed on the shore and disintegrated.

Source

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1943 09 12 Gran Sasso raid DFS 230 Luftwaffe Glider - Arkadiusz Wrobel

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Messerschmitt Me 321 Gigant (W2+??) heavy assault transport glider of Sonderstaffel GS 1. These were used for the first time in an operational air assault on Saaremaa Island, Estonia, as part of an attempt to capture the fort of Kübarsaare, 14 September 1941

#germany#ww2#luftwaffe#ww2 aircraft#messerschmitt#me 321#1941#estonia#german ww2 gliders#eastern front#Sonderstaffel gs 1

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

German Ju 87 Stuka dive bomber and DFS 230 gliders in flight over Italy, 1943

@Voicesof WW2 via X

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

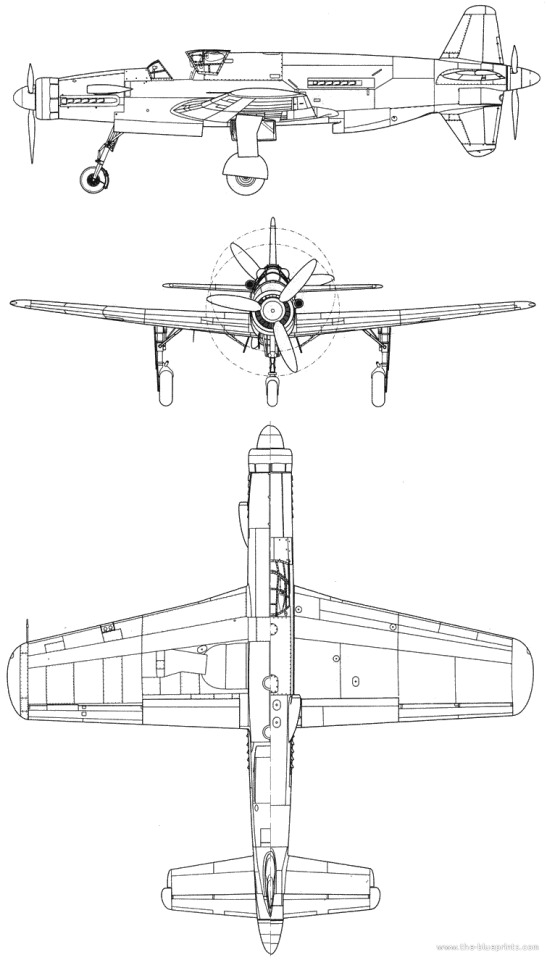

-A Dornier Do 335 Pfeil on a snowy runway, some time in 1944 or '45. | Photo: Luftwaffe

FLIGHTLINE: 181 - DORNIER DO 335 PFEIL ("ARROW")

Initially designed in response to a request for a Schnellbomber, the Do 335 was reconfigured into a multi-role aircraft, though only a few were completed before Germany surrendered.

Claude Dornier founded the Dornier Flugzeugwerke ("Aircraft factory") in 1914, and was renowned for building large, all-metal flying boats as well as land-based passenger aircraft between the Great War and WWII. These included the record-breaking Do 16 Wal ("Whale") of 1924, the Do X of 1929, and the Komet ("Comet") and Merkur ("Mercury"), a favorite of Lufthansa and SCADTA in Colombia, as well as several South American militaries. A feature of many Dornier aircraft were tandem engines, a tractor and a pusher motor placed back to back. This arrangement allowed an aircraft to enjoy the extra power of having multiple engines without the associated drag of having multiple tractor installations. It also alleviated the issue of asymmetric thrust in case of an engine failure.

-A Do X in flight, circa January 1932. This was one of a number of Dornier flying boats to have a tandem engine configuration. | Photo: German Federal Archives

DEUTSCHLAND PFEILE

What became the Do 335 originated in 1939, while Dornier was working on the P.59 Schellbomber ("high-speed bomber"), which would have carried and equivalent load to a Ju 88 or Me 410, but featured a tandem engine arrangement. Work on the P.59 was cancelled in 1940, but Dornier had already commissioned a test aircraft, the Göppingen Gö 9, to test the feasibility of connecting a pusher prop via an extended drive shaft. The Go 9 was based on the Do 17 bomber, but scaled down 40% and with a cruciform tail. The test plane validated Dornier's designs, though the eventual fate of the Go 9 is not known (likely though, it was destroyed by Allied bombing or recycled).

-The Göppingen Gö-9 motor glider, designed by Wolf Hirth. flying c.1941. | Photo: Flightglobal

The P.59's general design was resurrected in 1942 when the RLM requested a high-speed bomber with a 1,000kg payload. Dornier submission, designated the P.231, was awarded a development contract and the model number Do 335. Late in 1942, the requirements were changed from a Schnellbomber to a multirole fighter, which resulted in extensive delays while the designs were updated.

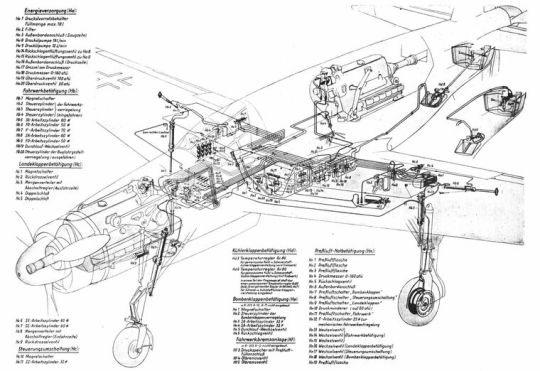

FLUGZEUGSPEZIFIKATIONEN

The Do 335 was 13.85m long, with a wingspan of 13.8m and a height of 5m. Empty, the plane weighed 7,260kg, while at max TO the weight was 9,600kg (10,000kg for the two-seat trainers and night fighter variants). Power was provided by two Daimler-Benz DB 603E-1 liquid-cooled V-12s developing 1,324kW each. Due to the situation in late-war Germany, the engines were fitted to run on 87 octane "B4" lignite-derived synthetic fuel, and MW50 boost was also available for additional speed. The basic fighter/bomber variant was armed with a singe 30mm MK 103 cannon firing through the spinner and two 20mm MG 151/20 autocannon mounted in the front engine cowl and synchronized to fire through the prop disc. A single 500kg bomb could be carried internally, and two pylons on the wings could be fitted with bombs, gun pods or drop tanks, with a total load of 100kg. During flight tests, the Do 335 hit 763kmh with boost (686kmh without), making it the fastest production fighter the Luftwaffe fielded during WWII. Under single-engine operations, the plane could still fly at 563kmh. Service ceiling was 11,400m, and under ideal conditions the plane could climb to 8,000m in 14 minutes 30 seconds. Due to concerns over a pilot striking the dorsal fin or the rear prop (a common concern in pusher designs before ejector seats became common), explosive charges would sever the fin and propeller before the pilot would bail out.

-Orthograph of the Do 335 A-1. | Illustration: Richard Ferriere

-Cutaway drawing of the Pfeil showing the engines, linkages, and landing gear actuators. | Illustration: Dornier

-Mounting locations of the 335's guns and associated equipment. | Illustration: Dornier

Maiden flight of the Do 335 V1 prototype was on 26 October 1943. A total of 27 flights were made with the V1, which uncovered a weakness in the landing gear, and issues with the main landing gear wheel-well doors saw them removed for the majority of the flights. The second aircraft, V2, first flew on 31 December 1943, and featured uprated DB 603A-2 engines as well as aerodynamic changes informed by the V1's test flights as well as wind tunnel tests. Maiden flight of the V3 pre-production aircraft was on 20 January 1944, which was fitted with DB 603G-0 engines, which produced 1,400kW at take off. The V3 was also fitted with two rear-view mirrors, alleviating blind spots caused by the location of the aft engine. A total of ten preproduction aircraft were then ordered, and in January the RLM ordered five more prototypes of the night fighter variant, later designated the A-6. By war's end, at least 16 prototypes of the Do 335 and related programs had flown, accumulating some 60 flight hours.

-The Do 335 V1 during testing in 1943 or '44. | Photo: Luftwaffe

Production of the Do 335 was given maximum priority under Hitler's Jägernotprogramm (Emergency Fighter Program), issued on 23 May 1944, and the competing He 219 Uhu ("eagle-owl") Nachtjäger theoretically freed up needed DB 603 engines for the Pfeil, but in practice Heinkel continued production of the 219A. Dornier's factories in Friedrichshafen and Munchen were anticipated to produce 120 and 2,000 Do 335s, of various configurations, by March 1946, but an Allied attack on Friedrichshafen destroyed tooling for the Pfeil, which resulted in a new line being set up in Oberpfaffenhofen. The first preproduction Do 335 A-0 model was delivered in July 1944, and construction of the first production A-1 model began in late 1944. As the war progressed, various models of the Do 335 proliferated (as happened often with late-war aircraft programs) as the Nazis sought to turn back the Allied forces:

Do 335 A-2: single-seat fighter-bomber aircraft with new weapon sights, later proposed longer wing and updated 1,471 kW (1,973 hp) DB603L engines.

Do 335 A-3: single-seat reconnaissance aircraft built from A-1 aircraft, later proposed with longer wing.

Do 335 A-4: single-seat reconnaissance aircraft with smaller cameras than the A-3

Do 335 A-5: single-seat night fighter aircraft, later night and bad weather fighter with enlarged wing and DB603L engines.

Do 335 A-6: two-seat night fighter aircraft, with completely separate second cockpit located above and behind the original.

Do 335 A-7: A-6 with longer wing.

Do 335 A-8: A-4 fitted with longer wing.

Do 335 A-9: A-4 fitted with longer wing, DB603L engines and pressurized cockpit.

Do 335 A-11/12: A-0 refitted with a second cockpit to serve as trainers.

-A Do 335 A-12 trainer, known as the Ameisenbär ("anteater"), late in the war. | Photo: Luftwaffe

Do 335 B-1: abandoned in development.

Do 335 B-2: single-seat destroyer aircraft. Fitted with 2 additional MK 103 in the wings and provision to carry two standard Luftwaffe 300 litre (80 US gal) drop tanks.

Do 335 B-3: updated B-1 but with longer wing.

Do 335 B-4: update of the B-1 with longer wing, DB603L engine.

Do 335 B-6: night fighter.

Do 335 B-12: dual-seat trainer version for the B-series aircraft.

Do 435: a Do 335 with the redesigned, longer wing. Allied intelligence reports from early May 1945 mention spotting a Do 435 at the Dornier factory airfield at Lowenthal.

Do 535: actually the He 535, once the Dornier P254 design was handed over to Heinkel in October 1944; fitted with jet engine in place of rear piston engine.

Do 635: twin-fuselaged long-range reconnaissance version. Also called Junkers Ju 635 or Do 335Z. Mock up only.

P 256: turbojet nightfighter version, with two podded HeS 011 turbojet engines; based on Do 335 airframe.

In April 1945 the Allies captured the Oberpfaffenhofen factory in late April 1945, capturing 11 A-1 fighter/bombers and 2 A-12 trainers. That same month, a flight of four RAF Hawker Tempests, led by French ace Pierre Clostermann, encountered an unknown model of Do 335 over northern Germany at low altitude. The Pfeil pilot began evasive maneuvers, but Clostermann opted to not give chase as the enemy plane displayed superior speed. At the time of the German capitulation in 1945, 22 Do 335A-0, A-1 and A-11/12 aircraft were known to have been completed.

-Dornier Do 335 aircraft on the runway at Oberpfaffenhofen just after the end of the Second World War. | Photo: USAAF

-A Do 335 after being captured by the US, with American markings painted over the Luftwaffe ones. | Photo: Charles Daniels Collection/SDASM Archives

At least two Do 335s were brought to the US under Operation LUSTY, with one, Do 335 A-0, designated A-02, with construction number (Werknummer) 240 102, and Stammkennzeichen ("factory radio code registration") VG+PH being claimed by the Navy for testing. The aircraft was transported on HMS Reaper along with other captured German aircraft, then shipped to the Navy's Test and Evaluation center at NAS Pax River. Another Pfeil was tested by the USAAF at Freeman Field in Indiana, but nothing is known about its fate. In 1961 VG+PH was transferred to the Smithsonian Institution, though it remained outside at NAS Oceana until 1974, when it was shipped back to the Dornier factory in Oberpfaffenhofen for restoration. Over the next year, volunteers from Dornier (some of whom worked on the aircraft originally) found that the explosive charges meant to sever the tail and aft prop were still installed and live, thirty years later. After work was completed the aircraft was placed on display at the Hannover Airshow from 1 to 9 May 1976, and afterwards it was on loan to the Deutsches Museum until 1988. The aircraft was shipped back the States after that, and is now on display at the Udvar-Hazy Center along with other German aircraft brought over during Lusty like the only known Ar 234 Blitz jet bomber and the partially restored He 219A Uhu.

#aircraft#aviation#avgeek#airplanes#airplane#aviation history#ww2 history#ww2 german aircraft#ww2 aircraft#ww2#ww 2 aircraft#ww 2#wwii history#wwii aircraft#wwiii#ww ii#ww ii aircraft#secret project#secret weapons of the Luftwaffe#luftwaffe#wonder weapons

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

• Hanna Reitsch

Hanna Reitsch was a German aviator and test pilot. Along with Melitta von Stauffenberg, she flight tested many of Germany's new aircraft during World War II and received many honors. She set more than 40 flight altitude records and women's endurance records in gliding and unpowered flight, before and after World War II.

Reitsch was born in Hirschberg, Silesia (today Jelenia Góra in Poland) on March 29th, 1912 to an upper-middle-class family. She was daughter of Dr. Wilhelm Willy Reitsch, who was ophthalmology clinic manager, and his wife Emy Helff-Hibler von Alpenheim, who was a member of the Catholic Austrian nobility. Hanna grew up with two siblings, her brother Kurt, a Frigate captain, and her younger sister Heidi. She began flight training in 1932 at the School of Gliding in Grunau. While a medical student in Berlin she enrolled in a German Air Mail amateur flying school for powered aircraft at Staaken, in a Klemm Kl 25. In 1933, Reitsch left medical school at the University of Kiel to become, at the invitation of Wolf Hirth, a full-time glider pilot/instructor at Hornberg in Baden-Württemberg. Reitsch contracted with the Ufa Film Company as a stunt pilot and set an unofficial endurance record for women of eleven hours and twenty minutes. In January 1934, she joined a South America expedition to study thermal conditions, along with Wolf Hirth, Peter Riedel and Heini Dittmar. While in Argentina, she became the first woman to earn the Silver C Badge, the 25th to do so among world glider pilots. In June 1934, Reitsch became a member of the Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Segelflug (DFS) and became a test pilot in 1935. Reitsch enrolled in the Civil Airways Training School in Stettin, where she flew a twin-engine on a cross country flight and aerobatics in a Focke-Wulf Fw 44. At the DFS she test flew transport and troop-carrying gliders, including the DFS 230 used at the Battle of Fort Eben-Emael.

In September 1937, Reitsch was posted to the Luftwaffe testing centre at Rechlin-Lärz Airfield by Ernst Udet. Her flying skill, desire for publicity, and photogenic qualities made her a star of Nazi propaganda. Physically she was petite in stature, very slender with blonde hair, blue eyes and a "ready smile". She appeared in Nazi propaganda throughout the late 1930s and early 1940s. Reitsch was the first female helicopter pilot and one of the few pilots to fly the Focke-Achgelis Fa 61, the first fully controllable helicopter, for which she received the Military Flying Medal. In 1938, during the three weeks of the International Automobile Exhibition in Berlin, she made daily flights of the Fa 61 helicopter inside the Deutschlandhalle. In September 1938, Reitsch flew the DFS Habicht in the Cleveland National Air Races. Reitsch was a test pilot on the Junkers Ju 87 Stuka dive bomber and Dornier Do 17 light/fast bomber projects, for which she received the Iron Cross, Second Class, from Hitler on March 28th, 1941. Reitsch was asked to fly many of Germany's latest designs, among them the rocket-propelled Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet in 1942. A crash landing on her fifth Me 163 flight badly injured Reitsch; she spent five months in a hospital recovering. Reitsch received the Iron Cross First Class following the accident, one of only three women to do so.

In February 1943 after news of the defeat in the Battle of Stalingrad she accepted an invitation from Generaloberst Robert Ritter von Greim to visit the Eastern Front. She spent three weeks visiting Luftwaffe units, flying a Fieseler Fi 156 Storch. On February 28th, 1944, she presented the idea of Operation Suicide to Hitler at Berchtesgaden, which "would require men who were ready to sacrifice themselves in the conviction that only by this means could their country be saved." Although Hitler "did not consider the war situation sufficiently serious to warrant them...and...this was not the right psychological moment", he gave his approval. The project was assigned to Gen. Günther Korten. There were about seventy volunteers who enrolled in the Suicide Group as pilots for the human glider-bomb. By April 1944, Reitsch and Heinz Kensche finished tests of the Me 328, carried aloft by a Dornier Do 217. By then, she was approached by SS-Obersturmbannführer Otto Skorzeny, a founding member of the SS-Selbstopferkommando Leonidas (Leonidas Squadron). They adapted the V-1 flying bomb into the Fieseler Fi 103R Reichenberg including a two-seater and a single-seater with and without the mechanisms to land. The plan was never implemented operationally, "the decisive moment had been missed."

In her autobiography Fliegen, mein Leben Reitsch recalled that after two initial crashes with the Fi 103R she and Heinz Kensche took over tests of the prototype Fi 103R. She made several successful test flights before training the instructors. "Though an average pilot could fly the V1 without difficulty once it was in the air, to land it called for exceptional skill, in that it had a very high landing speed and, moreover, in training it was the glider model, without engine, that was usually employed." In October 1944, Reitsch claims she was shown a booklet by Peter Riedel which he'd obtained while in the German Embassy in Stockholm, concerning the gas chambers. She further claims that while believing it to be enemy propaganda, she agreed to inform Heinrich Himmler about it. Upon doing so, Himmler is said to have asked whether she believed it, and she replied, "No, of course not. But you must do something to counter it. You can't let them shoulder this onto Germany." "You are right," Himmler replied. During the last days of the war, Hitler dismissed Hermann Göring as head of the Luftwaffe and appointed Reitsch's lover, von Greim, to replace him. Von Greim and Reitsch flew from Gatow Airport into embattled Berlin to meet Hitler in the Führerbunker, arriving on April 26th, as the Red Army troops were already in the central area of Berlin. Reitsch and von Greim had flown from Rechlin–Lärz Airfield to Gatow Airfield in a Focke Wulf 190, escorted by twelve other Fw 190s from Jagdgeschwader 26 under the command of Hauptmann Hans Dortenmann. In Berlin, Reitsch landed a Fi 156 Storch on an improvised airstrip in the Tiergarten near the Brandenburg Gate. Hitler gave Reitsch two capsules of poison for herself and von Greim. She accepted the capsule.

During the evening of April 28th, Reitsch flew von Greim out of Berlin in an Arado Ar 96 from the same improvised airstrip. This was the last plane out of Berlin. Von Greim was ordered to get the Luftwaffe to attack the Soviet forces that had just reached Potsdamer Platz and to make sure Heinrich Himmler was punished for his treachery in making unauthorised contact with the Western Allies so as to surrender. Troops of the Soviet 3rd Shock Army, which was fighting its way through the Tiergarten from the north, tried to shoot the plane down fearing that Hitler was escaping in it, but it took off successfully. Reitsch was soon captured along with von Greim and the two were interviewed together by U.S. military intelligence officers. When asked about being ordered to leave the Führerbunker on April 28th, 1945, Reitsch and von Greim reportedly repeated the same answer: "It was the blackest day when we could not die at our Führer's side." Reitsch also said: "We should all kneel down in reverence and prayer before the altar of the Fatherland." When the interviewers asked what she meant by "Altar of the Fatherland" she answered, "Why, the Führer's bunker in Berlin ..." She was held for eighteen months. Von Greim killed himself on May 24th, 1945. Evacuated from Silesia ahead of the Soviet troops, Reitsch's family took refuge in Salzburg. During the night of May 3rd, 1945, after hearing a rumour that all refugees were to be taken back to their original homes in the Soviet occupation zone, Reitsch's father shot and killed her mother and sister and her sister's three children before killing himself.

After her release Reitsch settled in Frankfurt am Main. After the war, German citizens were barred from flying powered aircraft, but within a few years gliding was allowed, which she took up again. In 1952, Reitsch won a bronze medal in the World Gliding Championships in Spain; she was the first woman to compete. In 1955 she became German champion. She continued to break records, including the women's altitude record (6,848 m (22,467 ft)) in 1957 and her first diamond of the Gold-C badge. During the mid-1950s, Reitsch was interviewed on film and talked about her wartime flight tests of the Fa 61, Me 262 and Me 163. In 1959, Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru invited Reitsch, who spoke fluent English, to start a gliding centre, and she flew with him over New Delhi. In 1961, United States President John F. Kennedy invited her to the White House. From 1962 to 1966, she lived in Ghana. The then Ghanaian President, Kwame Nkrumah invited Reitsch to Ghana after reading of her work in India. At Afienya she founded the first black African national gliding school, working closely with the government and the armed forces. The West German government supported her as technical adviser. Reitsch's attitudes to race underwent a change. "Earlier in my life, it would never have occurred to me to treat a black person as a friend or partner ..." She now experienced guilt at her earlier "presumptuousness and arrogance". She became close to Nkrumah. The details of their relationship are now unclear due to the destruction of documents, but some surviving letters are intimate in tone. In Ghana, some Africans were disturbed by the prominence of a person with Reitsch's past, but Shirley Graham Du Bois, a noted African-American writer who had emigrated to Ghana and was friendly towards Reitsch, agreed with Nkrumah that Reitsch was extremely naive politically. Throughout the 1970s, Reitsch broke gliding records in many categories, including the "Women's Out and Return World Record" twice, once in 1976 (715 km (444 mi)) and again, in 1979 (802 km (498 mi)), flying along the Appalachian Ridges in the United States. During this time, she also finished first in the women's section of the first world helicopter championships. Reitsch was interviewed and photographed several times in the 1970s, towards the end of her life, by Jewish-American photo-journalist Ron Laytner.

Reitsch died of a heart attack in Frankfurt at the age of 67, on August 24th, 1979. She had never married. She is buried in the Reitsch family grave in Salzburger Kommunalfriedhof. Former British test pilot and Royal Navy officer Eric Brown said he received a letter from Reitsch in early August 1979 in which she said, "It began in the bunker, there it shall end." Within weeks she was dead. Brown speculated that Reitsch had taken the cyanide capsule Hitler had given her in the bunker, and that she had taken it as part of a suicide pact with Greim. No autopsy was performed, or at least no such report is available.

#ww2#world war 2#second world war#world war ii#wwii#history#german history#biography#aviation#womens history#women in history#germany#airforce history#test pilot

46 notes

·

View notes

Video

Elliott EoN Primary 'AQQ' [G-ALPS / BGA580] by Alan Wilson Via Flickr: Owned and operated by the Shuttleworth Collection. c/n EON/P/003. Seen displaying at Old Warden during the 2013 Autumn Airshow. 06-10-2013 The details below are from the Shuttleworth Collection website:- After the Armistice had been signed in 1918, Germany was not allowed to have an air force. However gliding was not forbidden and this was a good way for pilot training to be undertaken. Several different designs were produced, however one of the most common was the Schneider SG38 glider. This was a development of earlier Zogling gliders and featured shock absorbers among other detail improvements. Many Luftwaffe pilots had their first experience of flying during bungee launches with an SG38 glider. This glider is actually a post-war EoN Primary glider. The Elliots of Newbury (EoN) Primary glider was a development of the similar German pre-war gliders and had many components which were the same as the German SG38 gliders of the 1930s. It has been finished to represent one of these gliders. The glider has been restored by Peter Underwood and a team of SVAS volunteers. The glider made its first bungee assisted flight on 16th April 2008 in the hands of Frank Chapman.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Skorzeny is seen here dressed in a Luftwaffe tropical uniform immediately after freeing Mussolini from his captors on the Gran Sasso. The daring landing by glider and the rescue of Hitler’s closest ally would be fully exploited by Goebbel’s Propaganda Ministry, and made Skorzeny a household name in Germany. Note that some Italian personnel seem quite happy to be included in the photo. (US National Archives)

Photo and caption featured in German Special Forces of World War II (Elite Book 177) by Gordon Williamson

12 notes

·

View notes