#luc sante

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

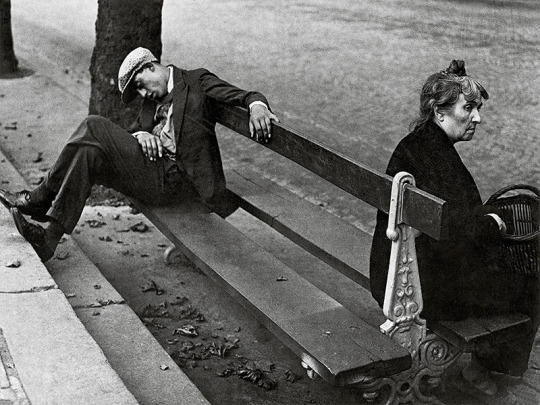

Youths of my generation learned about Brassaï from his eye-opening Secret Paris of the 30s. There were pictures of thugs, bums, prostitutes, brothels, drag balls, lesbian bars, interracial dances—who knew such things even existed forty years earlier? But then our fascinated naïveté was rewarded by further contemplation of the photographs, which were humane, sympathetic, endlessly inquisitive, beautifully composed, and drew every possible bit of poetry from the enveloping cloak of night.

– Luc Sante

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Factory Of Facts (1998)

Luc Sante / Lucy Sante

Pantheon Books

0 notes

Text

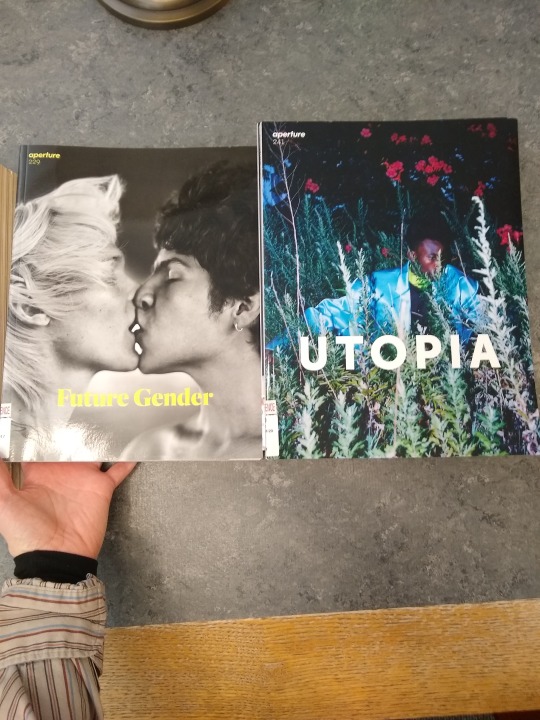

Highlights from the monthly Art Book Club at Milwaukee Public Library- Central. (next one is 2/26!)

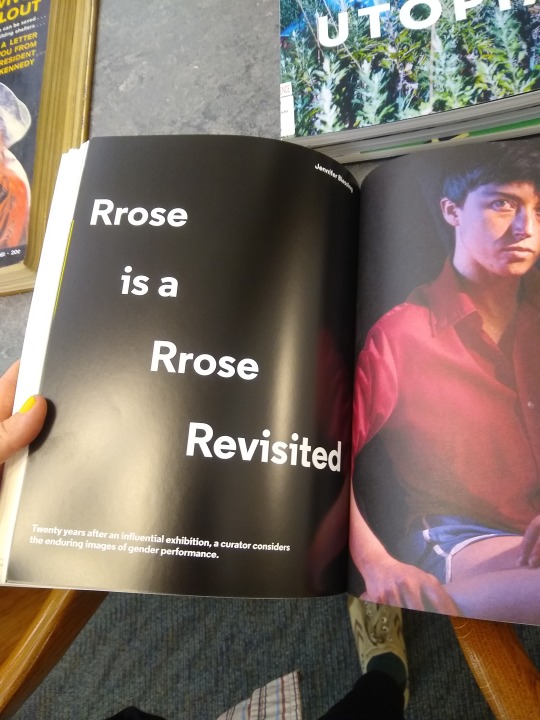

Images 1-2: Aperture 229 Winter 2017 (feat. Rrose is a Rrose is a Rrose revisited)/ Aperture 241 Winter 2020

Image 3: from The Spirited Earth: Dance, Myth, and Ritual from South Asia to the South Pacific by Victoria Ginn

Images 4-6: from Nan Goldin / I'll be Your Mirror

#gender performance#photography#art books#nan goldin#cindy sherman#luc sante#aperture#i'll be your mirror#milwaukee public library#art book club#masking#future gender

0 notes

Text

Cavaliers du froid et saints de glace

Cavallers del fred i sants de glaç Jean-Luc Modat Méfions-nous d’Avril avec ses extravagances nous réserve bien des surprises ! Une petite piqûre de rappel ou un vaccin s’imposent à tous car la confusion règne entre Cavaliers du froid et Saints de glace. Les cavaliers surgissent dés le 23 avril jusqu’au 6 mai ; les Saints s’illustrent à partir du 11 mai puis les 12, 13, 14 Mai…. Et un petit…

#ant Jordi (Saint Georges)#bookelis#Castelnou#Cavaliers du froid#Cavaliers du froid et saints de glace#Cavallers del fred i sants de glaç#Collioure#Jean-Luc Modat#livre#lune rousse et saints de glace#MA CUISINE CATALANE#Perpignan#Saints de glace

0 notes

Text

#jean luc godard#novelle vague#movies#film#anna karina#sante parole#love#vintage#vintage style#quotes#phylosophy#milo manara#comics#fumetti

1 note

·

View note

Text

Lit Hub: The Question of Homoeroticism in Whitman’s Poetry

Walt Whitman’s best poems demonstrate an almost unimaginable prescience; he and Dickinson, among 19th-century American poets, possess a nearly chilling self-consciousness, an acute self-analysis. Edward Carpenter, the British anarchist, writer, and champion of the Arts and Crafts movement whose life and romance were the model for E. M. Forster’s novel Maurice, wrote this elegant description of a visit with Whitman in 1877; the emphases are Carpenter’s own: “If I had thought before (and I do not know that I had) that Whitman was eccentric, unbalanced, violent, my first interview certainly produced quite a contrary effect. No one could be more considerate, I may almost say courteous; no one could have more simplicity of manner and freedom from egotistic wrigglings; and I never met any one who gave me more the impression of knowing what he was doing more than he did.” That there were words for homosexual behavior in Whitman’s day there can be no doubt. Social structures for enabling same-sex congress seem to have been a feature of life in the modern city at least since the later 18th century, when the “Molly houses” in London offered a zone of permission for transvestism. Herman Melville, in Redburn, carefully evokes the nattily dressed fellows who hang out in front of a downtown restaurant where opera singers perform; he means us to understand what these stylish outfits convey. Historian and theorist Luc Sante describes a 19th-century pamphlet that takes as its project the publication of the locations of various quite particular spots of diverse sexual practice in New York City—so that those informed of, say, the address of a bordello featuring willing boys can take special care to avoid this hazard. Trenchant evidence comes from Rufus Griswold’s review of the 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass: “We have found it impossible to convey any, even the most faint idea of style and contents, and of our disgust and detestation of them, without employing language that cannot be pleasing to ears polite; but it does seem that someone should, under circumstances like these, undertake a most disagreeable, yet stern duty. The records of crime show that many monsters have gone on in impunity, because the exposure of their vileness was attended with too great indelicacy. Peccatum illud horrible, inter Christianos non nominandum.” Which is all a way of saying that Whitman inscribes his sexuality on the frontier of modernity; he is writing into being—particularly in the “Calamus” poems of 1860, with their frank male-to-male loving, their assumption of equality on the part of the lovers—a new situation. He does not know how to proceed—he has no path —but he does it anyway. My guess is that he couldn’t have written “Calamus,” or the boldly homoerotic portions of the 1855 Leaves, even ten years later, as the advent of psychology increasingly led to a public perception of the normative, and imagery of the sacred family becomes the object of Victorian romance. As a category of identity—sodomite, invert, debauchee, pervert, Uranian—begins to emerge, so the poems with their claims of a loving, healthy, freely embraced same-sex desire become unwriteable, paradoxically, just as new language of homosexual identity begins to appear. Unwriteable, and, it would seem from Whitman’s later remarks, and some of his revisions, barely defensible. Carpenter and his readers were reaching for signposts of a gay identity when such a thing barely existed, but Whitman is ultimately a queer poet in the deepest sense of the word: he destabilizes, he unsettles, he removes the doors from their jambs. There is an uncanniness in “Song of Myself” and the other great poems of the 1850s that, for all his vaunted certainty, Whitman wishes to underscore. Again and again, he points us toward what, it seems, must remain folded in the buds beneath speech, since it cannot be brought to the surface. (Full article)

#mark doty#walt whitman#edward carpenter#poets#poetry#history#gay history#lgbt history#lgbtq history#gay#lgbt#lgbtq#lgbtqia#lit#literature#gay literature#lgbt literature#lgbtq literature#victorian#19th century

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

How “Peanuts” Created a Space for Thinking

Charles Schulz’s beloved comic strip invited readers to contemplate the big picture on a small scale.

By Nicole Rudick August 6, 2019

Illustration Courtesy Peanuts Worldwide

In “The Storyteller,” an essay from 1936, the German-Jewish philosopher and critic Walter Benjamin describes what he sees as the beginning of the end of the oral tradition in the West. The collective trauma of the First World War and its aftereffects were making the communication of shared experiences through the telling of tales a thing of the past. He writes, “A generation that had gone to school on a horse-drawn streetcar now stood under the open sky in a countryside in which nothing remained unchanged but the clouds, and beneath these clouds, in a field of force of destructive torrents and explosions, was the tiny, fragile human body.” At the heart of this historical process is a grim efflorescence of experience: the sense that one is adrift in an unfamiliar landscape, a feeling that would endure as a defining condition of the twentieth century, when the world was expanding and becoming delimited at the same time. A few decades after Benjamin published his essay, the writer Luc Sante and his parents immigrated to the United States from Belgium. Sante’s mother and father spoke very little English, and, “tinged with a certain bitter realism,” they observed the foreign culture that surrounded them from an intimidating distance, as Sante explains in his introduction to “Peanuts Every Sunday: 1961-1965.” “It wasn’t surprising, then,” Sante continues, “that my father, an intelligent, capable man who had been dealt a series of bad hands by life—poverty, war, a truncated education—should see himself reflected in Charlie Brown.” Though he would come to be domesticated and beloved by Americans of all stripes, Charles Schulz’s comic-strip boy spoke to the émigré’s sense of dislocation, tough luck, and calamity.

There may be no more tiny, fragile body than Charlie Brown’s—the abbreviated torso, economized limbs, and naked, vulnerable head. That head: with a modicum of lines, Schulz produced an untouched, capacious orb on which a world of expression could play. In the Sunday strip for October 15, 1961, the title panel shows Charlie Brown’s head as a table globe, imprinted with a grid of latitude and longitude. The strip spins out the joke: to illustrate to Linus the distance between two locations (the absurd pairing of Texas and Singapore), Lucy plots the points over the top of Charlie Brown’s bare, impassive pate.

Surrounding this vulnerable human form is a wider world: hostile, exhausting, potent in its occasions for failure. Untethered from the historical moment, Benjamin’s agents of change, those “torrents and explosions” (like Hamlet’s enduring “whips and scorns of time,” which extend even to include the intimate “pangs of despised love”) are here as perennial humiliations played out in a fathomably unfathomable universe. “Peanuts,” Schulz once said, “deals in defeat.” At its core, the comic parses existential angst, strip by strip—not Cold War anxiety, a cloud under which “Peanuts” developed and flourished, but the garden-variety anxieties found in everyday life. Charlie Brown is the comic’s everyman (“Of all the Charlie Browns in the world, you’re the Charlie Browniest,” Linus complains in a 1965 “Peanuts” TV film), adept at losing one day and still rising the next to see things through. And yet, as grounded in real life as it seems to be, “Peanuts” shows very little of the actual world. The comic is striking for its spare visual details, its generic, repetitious settings, and its constrained action. Although the early strips were busy with detail, Schulz soon developed a style that was formally minimal. There is little in the way of depth perspective—and the action in each panel moves right and left, as if on a stage.

Illustration Courtesy Peanuts Worldwide

I remember noticing, as a child, this circumscribed world in which Charlie Brown and the gang air their problems. It was so markedly different from that of another deeply felt, philosophical comic of my youth, “Calvin and Hobbes,” which visually and imaginatively bursts at the seams. In the “Peanuts” strip from Sunday, June 9, 1963, Charlie Brown and Sally admire the night sky as he explains the future movement of the stars that make up the Big Dipper. All eight panels depict the same scene: Charlie Brown and Sally atop a patch of earth, the dark sky engulfing their bodies. Nothingness surrounds them—both formally, on the page, and literally, in the black yawn of space. Nothing much happens here, yet, in its openness and conversation, the strip is alive with wonder, possibility, and humanity. Schulz does a lot with nothingness. In another Sunday strip, from November 19, 1961, the title panel sets Charlie Brown’s round head alongside the great round face of a clock (his anxious expression and bird’s nest of hair make his features a counterpoint to the clock’s uniformity). We are invited to consider the solitude of the school lunch hour, when Charlie Brown must sit with his thoughts, literally: each of the panels below the top row features the lone figure and a speech bubble giving voice to his interior monologue. The spareness of each frame rivals that of the stage set for Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot”: only a bench and a paper-bag lunch. It’s no accident that the evenly distributed, postage-stamp-size panels number twelve, like the hours on a clock. Each movement of Charlie Brown’s head—he looks out and down, then up and right—is activated by the reader’s eye moving in rhythm from panel to panel to panel, like the ticking of a second hand.

That rhythmic deliberateness—specifically its leisurely meter—is essential to the way that “Peanuts” functions as a space for thought. A “Peanuts” strip, even one seemingly packed with goings-on, unfolds patiently. The strip from Sunday, April 18, 1965, depicts a disagreement (sparked by Lucy, of course) on the pitcher’s mound. Lucy wants Charlie Brown, who’s pitching, to “brush this guy back,” but Charlie Brown refuses, and an argument about morality ensues. Charlie Brown’s qualms about throwing a beanball make him a world-historical hypocrite, according to the others. “What about the way the early settlers treated the Indians? Was that moral? How about the Children’s Crusade? Was that moral?” Each new panel brings a fresh participant and perspective to the mound, and accusations become colloquy. By the penultimate panel, ten players stand on or around Charlie Brown’s perch (a pulpit overrun by parishioners), and five speech balloons, thick with philosophical reasoning (“Define morality!”), fill the sky over their heads. But Schulz makes order out of this chaos, arraying his characters in a single line (the panel is unambiguously “Last Supper”–ish, with characters, except for Charlie Brown, grouped in threes). One reads the scene from left to right, both together with and independent of the dialogue—a tidy progression that can be taken in with a serene sweep of the eye. (The thoughtful pacing in “Peanuts” is reminiscent of that of “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.” The two also share a rejection of the violence and manic energy that characterize other children’s media of the time.) The rhythm of the larger Sunday strips is particularly effective, as they have more space in which to work. But the same effect plays out on a smaller scale in the dailies. In a four-panel baseball strip from August 5, 1972, Lucy harangues Charlie Brown from left field. The entire top half of the second panel is tightly packed with her rant, rendered in a thicket of bold type and punctuated at the end with an eye-catching, electrifying “BOOOOOOO!!” Her energy is palpable, but it cannot last. In the next panel, she sits on the ground, alone and silent, like a calm ocean, and the reader’s eye rests on her form and the open white space surrounding it for a surprisingly long time before moving on to the last, bitterly self-reflective panel.

Few comic strips feel more like a series of vignettes than “Peanuts,” especially when the already minimal scenery disappears in favor of empty white or monochrome backdrops, as though a thick curtain has descended to pull a character further out of time and into some more concentrated realm of feeling. The generous allotment of white space in the daily strips originated not from design but from necessity. As David Michaelis details in “Schulz and Peanuts: A Biography,” the comic strip was first sold as a potential space filler to be used in any section of a newspaper, even the classifieds. To draw the reader’s eye, Schulz opted for the less-is-more approach, aiming to “fight back” with white space to echo what he once called the strip’s “very slight incidents.” The usefulness of that simplicity became clear as Schulz’s writing deepened. “The more they developed complex powers and appetites while staying faithful to their cut-out, shadow-play simplicity,” Michaelis writes of the strip’s characters, “the easier it would be for Schulz to declare the hard things he was set on saying.” Had Schulz filled his panels with visual distractions, the business of examining interior problems might have proved less successful.

The formal qualities of “Peanuts” made it an outlier. As a boy, Schulz read comics that incorporated tight cross-hatching, deep vanishing points, and threadlike lines, and also the masterly modernism of Frank King’s “Gasoline Alley.” But such visual enrichment didn’t appeal to him as a practicing cartoonist—he was, by his own admission, “a great believer in the mild in cartooning.” What of his comic’s contemporaries? Mort Walker’s “Beetle Bailey” and Hank Ketcham’s “Dennis the Menace” began around the same time as “Peanuts.” “Beetle Bailey” is an uncomplicated gag-dependent strip drawn with what Michaelis calls “elastic visual exaggerations,” and “Dennis the Menace” relies on a wealth of visual details to deliver its absurdist situational humor. Both grew faster than “Peanuts” in readership and recognition, but neither has attained its broad cultural impact.

One can easily forget how unlikely this cultural ascendency might have seemed when “Peanuts” débuted. Schulz created an oddly shaped boy, an anthropomorphized dog, and a host of children who don’t behave or speak as children do, and he placed them in an efficient, nondescript setting—only on the surface of reality, you might say. The reader should be skeptical of this setup. And yet Charlie Brown’s emotional struggle is familiar, and the reader is roused by it. Bertolt Brecht would have approved of “Peanuts.” He sought the same “partial” illusion for the theatre, he said, “in order that it may always be recognized as an illusion.” Too complete an impression of naturalness and one forgets that this isn’t reality but art. Brecht would have us read not literally but critically and interpretively. Though “Peanuts” does not have all the same aims as a piece of didactic political theatre like Brecht’s “Mother Courage and Her Children,” it, too, is meant to be engaged with, not skimmed over. The strip “deals in intelligent things,” Schulz once said, “things that people have been afraid of.” He did not consider “Peanuts” a children’s comic; even in Snoopy, his most kid-friendly character, Schulz created a self-willed, occasionally anxious fantasist.

I wonder if Brecht would have loved Lucy best, as I do. Born into “Peanuts” as a “fussbudget,” she soon became a prime mover behind the strip’s conflict and Charlie Brown’s feelings of disillusionment. Lucy is assertive, nervy, confident, stubborn, and manipulative; she can moon over a beau and still excoriate him for his inattentiveness. And, despite her near-constant bluster, she is a person who feels profound pain. In the Sunday strip for June 30, 1963, she feels low and rages, “I’ve never had anything, and I never will have anything!” Linus patiently replies, “Well, for one thing, you have a little brother who loves you.” And Lucy, her reserves spent, cries in his arms. Her modernity is on display best in her psychiatrist’s booth, which offers a kind of glimpse behind the scenes—that break with illusion that Brecht insisted on. A parody of the semiseriousness of a kid’s lemonade stand, Lucy’s booth calls itself a psychiatrist’s practice but offers none of the customary trappings other than its desk—but this pared-down presentation (along with, perhaps, Lucy’s confident authority) allows Charlie Brown to recognize the setup’s purpose. The reader recognizes it, too, but sees what Charlie Brown does not (or chooses not to): the booth is a façade, in construction and intent. Unlike the naïve young analysand, we won’t be beguiled by Lucy’s blunt advice. Still, we turn it over in our minds as we read, struck by some bigger truth in counsel that we know to be ill-advised.

Yet another defining visual feature of “Peanuts” is a low wall at which the characters sometimes pause for conversation. Some daily strips take place entirely behind this wall, like the one from Tuesday, May 6, 1958, which has Charlie Brown and Lucy leaning on its even stonework, facing out at the reader, in all four panels. The wall strikes me as a decidedly theatrical element, as makeshift as any that could be wheeled out onto a stage. The panels’ lines make a neat proscenium arch. (It is so obvious a device that when I see it I think of Snout in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” who, playing the part of a wall in the play within a play, insists, “This loam, this roughcast, and this stone doth show / That I am that same wall. The truth is so.”) If Lucy’s booth divides characters, with one on each side of the desk, and gives her an air of dialogic authority, then the wall is more Socratic, a site that encourages coöperative deliberation and reflection. In the strip for Monday, March 17, 1969, Linus and Lucy are at the wall. “I have a lot of questions about life, and I’m not getting any answers!” she complains, adding, in the next two panels, “I want some real honest-to-goodness answers. . . . I don’t want a lot of opinions. . . . I want answers!” In the last panel, Linus offers an answer that isn’t an answer, one that is itself a question and can only elicit further questions: “Would true or false be all right?”

Illustration Courtesy Peanuts Worldwide

Through “Peanuts,” Schulz wanted to tell hard truths about, as he said, “intelligent things.” But the main truth he tells is that there are no answers to the big questions. In the long run, no one wins and no one loses; this isn’t drama—it’s life. The strip’s solace is that the reader isn’t alone in facing these fraught issues, and its gift is a space in which she is invited to think, to contemplate the big picture on a small scale, like soaking in the emotional ambience of a Rothko painting. It’s tempting, and desirable, perhaps, to think of “Peanuts” as a mirror in which the reader sees and is absorbed by her own reflection, but that view undermines the elegant simplicity of Schulz’s creation: powerfully complex characters who, together, represent the constituent parts of humanity and who operate in a shadow play, to borrow Michaelis’s term. Schulz created in Charlie Brown “a man who reflects about his part,” as Benjamin writes of the actor in Brecht’s concept of epic theatre. (And here, again, we are not so far from Hamlet.) The irony of the visual flatness and economy of “Peanuts” is that they engender a capacious space—room enough both for Charlie Brown’s reflection on Schulz’s hard truths and for the reader’s own consideration of these big ideas. The strip’s achievement, and a significant reason for its longevity, is its creation of a space of inquiry that is never closed off.

Very early in the comic’s history, Schulz didn’t fully know his characters, in the way that a novelist or playwright can invent a set of characters but then must follow those characters’ lead to understand where they are meant to go and what they are meant to do. One strip of “Peanuts” can be satisfying in the way a single, shining sentence of a novel can be satisfying; we pin it on the wall as a reminder of an idea or a feeling, and it can stand on its own in that way, but it is also always only a fragment of a more expansive tale. It isn’t enough to see Lucy pull the football out from under Charlie Brown once; the point is that she does it again and again and again. The repetition of the act, from strip to strip, autumn to autumn, produces the same question anew each time: Why does she do it, and how does he respond? And, each time, the answer is different. (Charlie Brown “loses in so many miserable ways,” Schulz observed in an interview with Al Roker on “Today,” in 1999.)

The thoughtfulness with which Schulz examines humanity does not expire and does not cease to provoke astonishment (much like Lucy’s ongoing charade with the football). In the Sunday strip from November 26, 1961, Snoopy spends a dozen wordless panels bounding through curtains of rain that slash vertically and violently through each scene. Schulz punctuates the beagle’s short bursts of speed, rendered on monochromatic backgrounds, with tenuous moments of peace, as he pauses in doorways and under umbrellas—small moments of reprieve amid a visual cacophony. The final panel finds him recumbent atop his doghouse: the rain still falls in brutal torrents, but he is able to cope with it, a tender body at rest in a familiar landscape at last.

This essay was drawn from the anthology “The Peanuts Papers: Writers and Cartoonists on Charlie Brown, Snoopy & the Gang, and the Meaning of Life,” edited by Andrew Blauner, which will be published this fall, by the Library of America.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exhibit A Guy Bourdin

Samuel Bourdin- Fernando Delgado

Foreword by Luc Sante, Essay by Michel Guerrrin

Bulfinch,/Little Brown Publ., Boston NY London 2001, 208 pages, 38x29cm, 81 four col. & 19 duotone phot., ISBN 0-812-266 9 X

euro 150,00

email if you want to buy [email protected]

Guy Bourdin's surreal and erotic imagery filled pages of international magazines throughout the 1970s. Within the medium of fashion photography, he gave shape to a dark and intriguing vision that exerted lasting influence on the international style scene and altered the contemporary aesthetic. Bourdin rarely allowed his work to appear outside the pages of the magazines, and there has never been a book published devoted to his remarkable legacy. He remained an enigma, shunning publicity and becoming reclusive. After his death the French government seized all his work for non-payment of taxes and it was thought a book would be impossible. However, published under the guidance of Bourdin's son, Samuel Bourdin (who put his affairs in order and enabled publication) and creative director Fernando Delgado, Exhibit A presents for the first time a comprehensive look at the range and depth of Bourdin's photographic work, from the mid-1950s until his death in 1991. The images herein represent the highlights of his career - including his work for Vogue Paris and his revolutionary advertising campaign for Charles Jourdan shoes. Bourdin is featured and canonized in every history of commercial photography for a style described by one historian as the 'look of an era, glamorous, hard-edged with implied narratives and strong, erotic undercurrents'. Vogue became a playground for him, the magazine's double-page spread allowing him to indulge his fantasies. He constructed narratives and small scenarios; inventive, shocking and erotic they only served to nurture his own macabre and dangerous persona. A biographical essay by Michel Guerrin, photography critic for Le Monde, will provide a long-overdue look at Bourdin's career. Writer Luc Sante (author of American Photography 1890-1965 and New York Noir) contributes a foreword. Exhibit A: Guy Bourdin is a landmark volume; these compelling images are as provocative today as they were over two decades ago, and they have left an indisputable mark upon contemporary photography and the visual arts.

19/10/24

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading One- Response

For the nature of photographs, I initially found the black and white photographs to be very interesting. Learning to understand the nature of photographs is intriguing. Very cool how we are taught that photos can be viewed on multiple levels. The physical and formal attributes of a photographic print being a photographers tools used to define and interpret their created content is something I had never heard before. I found this to be eye opening and considering this was written in 1936 feels like a far advanced perspective for the time. Prints having physical dimension is interesting while the nature of photographs have chemical and physical boundaries. Color plays a big role by giving descriptive information and transparency to an image. The color photos are beautiful. Tonal ranges are affected by the type of emulsion the print is made with. Stunning work by all of the artists.

For the interview of Stephen Shore by Luc Sante the three levels of a photograph are spoken on. So, the physical, depictive, and mental level are all seen by Stephen Shore to be the three broad sections of photographs. These photographic images have a picture plane according to Shore. The photo is embedded into the flat image. Photos simplify the world and give order to it. Luc calls it an analytical process. Shore says that builds the picture from the frame. The frame relates to what you’re paying attention to. Shore started using color because he found that he loved postcards and didn’t know why people weren’t using color. He closes the interview with a very profound thought: “illustration is aiming the camera at the direction of some content, while the photograph is making sense of it.” Shore is a very talented photographer, and his insights were intriguing to read.

Stephen Shore began his career by filling his photographs with attention. Like when an actor moves in a way that fills the theatre with attention. The video is of the photographer’s exhibition of his work at The MoMA. The exhibition entails about fifty years of his work. At 17 years old he met Andy Warhol and asked if he could go to his studio to take photos. So, he didn’t go to college and spent three years photographing at the Factory. He took pictures that we’re unburdened by visual conventions. He wanted to take pictures that seemed like seeing in one series. In another he wanted the photos to be of the descriptive power of the camera, creating a complex picture that the viewer moves their attention through. His landscape work took him time to make it look like deep receding space. He taught at Bard College without even a high school diploma.

0 notes

Text

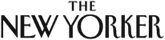

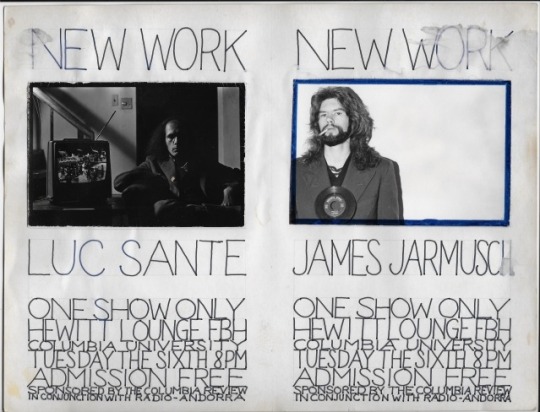

Flier for a reading at Columbia University featuring Luc Sante and Jim Jarmusch

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Final Images and Statement:

For this assignment, I knew that I wanted to build off my previous work by using architecture at the forefront of the manipulations. My original plan was to look at feelings of isolation through architecture and landscape, however, after some test manipulations I found that the work was not developing how I wanted it to, and I was not feeling excited about what I was making. This caused a change of plans, where I went back to my previous assignment and found that I liked how certain colours and types of buildings have connotations that when presented together, tell a specific story, or generate certain feelings, therefore, finding myself more drawn to warm lighting, and the emotional nostalgic response I got from it.

I have a deep appreciation for old architecture, and I often find myself imagining what life was like at the time of these buildings’ creation. This inspired me to explore the idea of nostalgia through architecture and landscape. Old photographs often have a sepia tone that people can recognise as being vintage, so I decided to create my own versions of vintage photographs by manipulating my images using a warm sepia/brown colour palette, alongside photographs of old houses and churches.

Within these 3 images, I have explored how specific lighting, combined with landscape and architecture, can generate a nostalgic emotional response. I cut out parts of my own photographs and merged them into 3 separate images that work within a set, exhibiting different perspectives and scenery. While manipulating these images, I thought about Jonas Bendiksen’s The Book of Veles, in which he manipulated fake photographs to trick the photographic community by playing into stereotypes of a drug-ridden European city. This was due to multiple cases of fake news and hacking coming out of Russia, causing him to fear that it would not be long until documentary photography could no longer be based in reality, but instead, fantasy from powerful digital tools. This interested me as I realised in some way, this is what I was doing. I was creating imaginary compositions and trying to make them look as though they were from hundreds of years ago.

These manipulations are intended to be seen in a book but if they were to be seen without context, would viewers believe that they were actually REAL vintage photographs? This made me work hard to try and get my photographs to feel as nostalgic and old, through the sepia tones and subject matter, as possible. To help myself achieve this, I researched other photographers who had taken and edited their photos to be sepia-toned or to showcase warm lighting such as Rick Keller, Daniel X. O’Neil, and Peter Fodor.

The ideas presented in Bendiksen’s Book of Veles were instrumental to my overall direction with my idea of nostalgia. My 3 image manipulations use vintage stereotypes and cliches of sepia tones, combined with photographs of old churches and houses, for the purpose of presenting them in a book as if they were real photographs. This reminded me of the important ethics surrounding photography and manipulation as the lines between what’s real and what’s fake slowly start to blur. I believe this project was beneficial to me through how creating my own manipulations taught me to always consider what is real and what is fake.

REFERENCES:

Miller, Jessica. Fake News: how Jonas Bendiksen hoodwinked the photographic community with The Book of Veles. 14 February 2022. https://amateurphotographer.com/book_reviews/fake-news-how-jonas-bendiksen-hoodwinked-the-photographic-community-with-the-book-of-veles/.

Sante, Luc. Colors/Sepia: Picturing Nostalgia. 2004. https://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/14/sante.php#:~:text=Viewed%20in%20this%20light%2C%20sepia,had%20become%20objects%20of%20nostalgia.

0 notes

Text

“One Health” ou la santé des trois règnes

“One Health”, nouveau concept issu de l'OMS depuis les années 2000 qui est mis en exergue pour le moment (1). La santé de la planète est unique, comme un Dieu unique, mais Dieu de l'Univers, un Démiurge (dont j'ai déjà touché mot) cher à Laurent Alexandre, un dieu de la matière issu de la gnose et du néoplatonisme. Je propose dès lors qu'elle soit trinitaire, composée des trois règnes : minéral, végétal et animal pour parfaire l'analogie. Ce délire mondialiste n'est possible qu'en mettant un place une “One Cloud” qui va tracer tout le vivant... et pour ce faire, notre consentement est requis. À bon conformiste : santé !

‣ ANSES, « One Health : une seule santé pour les êtres vivants et les écosystèmes », pub. 23 mars 2023, https://www.anses.fr/fr/content/one-health-une-seule-sante-pour-les-etres-vivants-et-les-ecosystemes (cons. 26 sept. 2023).

—

(1) Ce mardi 24 sept. Arnaud Ruysen recevait Jean-François Collet, chercheur à l’Institut de Duve et professeur à l’UCLouvain et Leïla Belkhir, infectiologue aux Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc et professeure à l’UCLouvain pour nous informer que “une récente étude dans la revue The Lancet estime qu’à l’horizon 2050, les bactéries résistantes aux antibiotiques pourraient causer la mort de 39 millions de personnes dans le monde” ; et qu'il est donc urgent de mettre cette politique “One Health” en pratique | RTBF, La Première, « Les clés », « Résistance aux antibiotiques : pourquoi est-ce un problème majeur de santé ? », pub. 24 sept. 2024, (via login et mdp) https://auvio.rtbf.be/media/les-cles-les-cles-3249567 (cons. 26 sept. 2024)

—

0 notes

Text

Issue #148: Lee Quiñones by Luc Sante

BOMB Magazine's Luc Sante shows us how prolific artist Lee Quiñones comes up with some of his famous creations.

0 notes

Text

He was also frightened of invertebrates, marine life in general, temperatures below freezing, fat people, people of other races, race-mixing, slums, percussion instruments, caves, cellars, old age, great expanses of time, monumental architecture, non-Euclidean geometry, deserts, oceans, rats, dogs, the New England countryside, New York City, fungi and molds, viscous substances, medical experiments, dreams, brittle textures, gelatinous textures, the color gray, plant life of diverse sorts, memory lapses, old books, heredity, mists, gases, whistling, whispering—the things that did not frighten him would probably make a shorter list. He evidently took pleasure in his fears

The Heroic Nerd by Luc Sante in The New York Review of Books, 2006 October 19

0 notes

Text

A l’occasion de la nouvelle année 2024, je présente à tous mes lecteurs et lectrices mes meilleurs vœux. Mais quels vœux ?

VOEUX DE SANTE ::

En ce début d’année, nous entendons souvent cette expression : « Bonne année, bonne santé ! » et l’on ajoute : « la santé, c’est le principal ». Il va de soi que l’on pense à la santé du corps. . Mais n’y a-t-il pas quelque chose de plus important que la santé du corps ? Le "principal", n’est-ce pas la santé de l’âme ? Lorsque nous nous rencontrons, nous posons cette question : « Comment allez-vous ? » Souvent la réponse est : « très bien, merci ! ». Si la question était : « comment va votre âme ? » que répondrions-nous ?

VOEUX DE PROSPERITE :

l’on présente les vœux ne manquent de rien, tout en se souvenant de cette parole du Seigneur Jésus : « Quelqu’un a beau être dans l’abondance, sa vie ne dépend pas de ses biens. » (Luc 12 v.15)

L’apôtre Paul recommande à ceux qui sont riches « de ne pas être orgueilleux et de ne pas mettre leur espérance dans l’incertitude des richesses, mais en Dieu qui nous donne tout en abondance pour en jouir » (1 Timothée 6 v.17)

En souhaitant la prospérité, pensons-nous aussi à celle de l’âme ? Pouvons-nous dire comme l’apôtre Jean à Gaïus : « Bien-aimé, je souhaite que tu prospères à tous égards et que tu sois en bonne santé, comme prospère ton âme » (3 Jean v.2) ? Le souhait de l’apôtre concerne à la fois la santé physique et la santé spirituelle de Gaïus.

VOEUX DE BONHEUR :

Le bonheur souhaité sur cette terre est éphémère et, même s’il dure, il se termine à la mort. Où donc trouver le vrai bonheur, le bonheur durable, éternel ?

Si tu veux le bonheur, le vrai bonheur,

Laisse entrer Jésus dans ton cœur !

Tes péchés il efface,

Il te fera la grâce

De transformer

Ton être tout entier,

Pour régner sur ton cœur !

Si tu veux le bonheur, le vrai bonheur,

Laisse entrer Jésus dans ton cœur !

VOEU LE PLUS GRAND :

Quel est le vœu le plus cher et le plus important ? Vœu qui n’est pas formulé seulement en début d’année, mais le vœu constant qui date de toute éternité :

Celui de « notre Dieu Sauveur qui veut que tous les hommes soient sauvés et viennent à la connaissance de la vérité » (1 Timothée 2 v.4)

Jésus dit : « Moi, je suis … la vérité » (Jean 14 v.6)

* * *

Cher lecteur, chère lectrice, avez-vous répondu au vœu de notre Dieu Sauveur ? Êtes-vous sauvé(e) ? Connaissez-vous Jésus, la Vérité ?

C’est le vœu le plus cher, le vœu du Dieu d’amour, ... et le nôtre.

* * *

[http://www.la-verite-sure.fr/page865.html](http://www.la-verite-sure.fr/page865.html?fbclid=IwAR2hRTBsihdYmqBy4lTh5-eJWUdayGrxb4xgwvMqxY23hvR5wrjWgCHhyNo)

0 notes