#love how this started just as a verse description and then my brain went wild

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Vale's Modern-ish/Fandomless Verse (PART 1)

Vale is 23 years old (Born on December 10th), and was born and raised in Orion, California, a (fictional) city with a good view of the beach, vibrant night life, and a fair amount of crime but it's fine, everything's okay. Vale has multiple jobs, trading their usual occupation of a 2077 mercenary for something a little closer to a mercenary of today's world: Delivery driver! Whenever Misty needs a little help at her store, Vale also covers at the esoterica.

Besides their job, Vale flourishes and thrives in their position as a little trouble maker in the city, giving cops a hard time as they do their urban exploring (trespassing wherever they please). The thing is, though, there's been some changes in their hometown, and Vale's not liking the change so much. The mayor wouldn't make any changes that help the people in need in the city, the mom and pop shops are getting bought out by bigger stores, and worst of all, the power plant on the outskirts of town was just put under new control of some CEO who was promising a newer, better form of power that could make nuclear look pitiful. The CEO offered less rolling blackouts, with no strings attached, it'd just cost a little more (that's what they always said, just a little more of your money until they ask for a little more).

No strings attached, but it smelled fishier than anything Vale had ever smelled before...and they lived by the beach! They smelled dead fish all the time! So that's what tipped them off, made them realize this deal had some greater plan going on behind it. And so they did what they knew best, broke into the CEO's penthouse, and found plans for testing, testing on live subjects. Testing that was approved by the mayor, some stooge in the pocket of that CEO. With a usb full of evidence in their pocket, Vale made a mad dash to get out of that penthouse before security finally got them. But of course, what good thief wouldn't take something for the road?

There had been a chunk of something, some cloudy, green crystal. Something that fit in their palm, something easy to take, something that felt like it was irradiating the air with its own buzzing aura, begging Vale to step closer and take it. It was their favorite color too, a clear sign they needed it. Even as the sound of the security guards' thudding boots got closer and closer, Vale felt themself rooted to the spot in the CEO's office, unable to look away from the captivating find.

And it was like lightning, the crystal was tucked under their arm as they sped through the halls of the penthouse. They dashed down the staircases, charged through fire exits, and even got to slide down the ladder on the fire escape. Sure, their hands got pretty scraped up, but it didn't matter. They made it out clean, and the busy, bright, loud city streets would keep them covered. But their cover wasn't foolproof, as their path-- guided by the street lamps and neon signs -- disappeared before their very eyes.

It started small, street lamps flickering. Then it got worse, neon signs shorting out. And it came to a climax, with the entire city's power supply wiped, and the streets were only brightened by car lights and the only sounds were questions of "Who turned out the lights?"

As citizens were asking questions to everyone they could see, calling 911, generally just starting a mass panic, Vale got to spend time with their solitary panic while they hid behind a parked bus. With people crowding the streets, calling the cops, and asking questions, there was a guarantee Vale was going to get arrested and thrown into prison for even breathing wrong in the direction of a rich person, let alone steal something from one! They hyperventilated, their heart pounded, their hands shook, and the crystal was glowing. All in all, pretty normal things to feel when--Wait...

"Why are you glowing?"

The question, asked through grit teeth, was the straw that broke the glowing camel's back. In a world full of darkness, all Vale could see was a piercing, green light, taking their vision and blinding them like a flashbang.

But the blindness faded. Colors returned to their sight. They breathed deep and heavy, air filling their lungs, filling them with an energy and power they had never felt before. Then they breathed out. And the alleyway around them glowed. It glowed brighter than any of the neon lights that would've been buzzing with electricity moments ago. Vale's freckles, which historically weren't bioluminescent, glowed under the darkness of the night sky, dark teal scales functioning as body-armor shimmering under their own light.

Huh. They wanted to give their body a second look, whatever dream they were dreaming seemed fun, so they might as well get a good look at--

Scales. Glowing. A tail. Claws. Sharp teeth. And the world was a hell of a lot shorter than it was before. With their world changed, there was only one way for Vale to react--

"FUCK YES! THIS IS THE BEST!"

Vale's joy was surely infectious, but maybe not for the people that were in the bus next to them. Where Vale was experiencing pure ecstasy, looking over their much more monstrous body, the people in the bus were experiencing a horror movie. Seeing an irradiated, 9ft beast rise to their feet and bellow human speech. People in the bus screamed, sending Vale's smile off to be turned into a confused frown, not entirely understanding why people were upset. They tried to raise their clawed hands, show they weren't a threat, but Vale's attempts at calm were quickly dashed away by the loud words of an unneeded stressor.

"OPD! Put your hands up where we can see them!"

"Aw. Dicks."

#AYYYYYY PART 1 POSTED#like I said we're taking a ride on the kaiju hybrid train#Verse: Modern#love how this started just as a verse description and then my brain went wild#and said it was action time

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Untitled Story - I

Just a little piece I’ve been toying around with at the moment - no plot, just writing for the sake of it.

*

It was Springtime when I first realised that I was lost.

I had tried to express this to Sami, my best friend, but he was too busy pacing forwards, turning, and pacing back again. He had this grand idea that a night bus would be soon to pick us up, and that we would be able to find a Bed and Breakfast in a town to get a good night’s sleep. I had already lay my jumper down in a tangle for my head to rest upon, lying flat on the bench. He relented, nonetheless.

Sami had a story behind him. His family, Spanish, moved here in a couple decades ago and worked their way to a comfortable home. He speaks both languages, and he just has this aura about him that I cannot transcribe. We became friends a while ago, I spoke a bit of Spanish, he spoke a bit of English, I helped him get about. It caused this dynamic where he would linger behind me, waiting for translation, rarely opening his mouth, and always watching with his squinted eyes. He felt like a shadow, quiet to everyone else and largely prominent with me. He would open up on these grand dialogues; his mind was trumpets and cymbals, a whole orchestra wild in his brain. He was practising getting his wild ideas into English on me, and this became habitual. The quiet guy all my acquaintances knew would be the excitable maniac I spent my nights with. We waited on.

I explained about us “being lost. It’s a state of mind more than anything”. I used my hands a lot in this description, I wasn’t sure what I was symbolising under the moon’s hazy gaze, but I could see Sami turn his eye in my direction as my hands animated themselves.

“It’s coming. Just wait a bit longer”, abruptly.

Sami has a story behind him, as I mentioned, I do not. I’m run-of-the-mill. I find it hard to communicate myself to others because I lack the foundations to make me stand tall. The world is full of dynamism and electricity and I’m an empty spark. I do, however, love to ignite others, I watch on quietly as Sami electrifies; people love to talk to me, but I rarely ever talk to them. They don’t see that of course.

The moon was washing the cold air with its soft light, stars would start their night shifts across the sky. They would flash out of the black and hang there slow, as my mind drifted off and my eyes became heavy.

***

“You missed out, again” Sami blocked the sun from my eye, the sky was cloudy and moved quickly beside his ears. “I’ve mentioned it before, but I will again, you miss out on a lot when you do stuff like that”.

I had fallen asleep. I felt grey bags pulling my eyes downwards and my mouth stung with dryness. I grabbed the metal bottle of water out of my bag.

“Ah well. It didn’t come, I waited all night for nothing. You missed a lot though. You have to stay awake and keep an eye out because it never stops, even when the stars are out” He had walked into the middle of the road and stared either way briefly during this utterance, he was now turning back towards me, sat up on the bench. “It’ll be here soon”.

I wiped my mouth and asked about what had happened over the night that made him so passionate.

A sigh, followed by a despondent, “Look, I’ll tell you when we’re sat on the coach. I’m still in process” came out of his equally dry mouth.

I could tell by his manner he felt dejected, so I hastened to try and take his mind elsewhere. Firstly, though, I went behind the bus stop to urinate. I looked onwards across the small, green hills. I was reasonably close to home, but those hills felt so far away. We had set off travelling because we had nothing better to do, and I knew it would have resulted in this. We were stranded more than ever; money was running low and the days were growing longer. Something was due to pick up for us and we were waiting eagerly for it. My view lifted from the Yorkshire plains to the cloudy sky above, they moved quickly and gave me hope for changes to come, even the sky couldn’t stay still.

Low rumbles of a bus drew our attention down the road. We weren’t waiting for a bus to stop on any particular side, in fact, any direction would be better than where we were. So, as soon as the sight of a bus appeared to be heading in the opposite direction to where we were stood, we gathered our bags and crossed the road in anticipation. Sami had already dug out all of the change in both our pockets ready to pay the driver, and his countenance became much more reassured as the bus approached.

It grew bigger on the road and it took the moment’s eternity to shatter before we could step through the cool air of the busses aisles and sit in the middle seat of the two rows to the disappointment of tired travellers.

Me and Sami talked briefly about the night until he grew withdrawn as more eyes turned our way. I meanwhile got into talk with the man sat next to me. He was set for his new job, all he had to do was “sign the contract, and I’ll be sorted me” in his slow, crawling accent.

He talked about his girlfriend, they had broken up, and now he had the job they would get back together. He was sure of this. He turned and with a twitch that registered his surprise that he was not alone in the conversation, asked me about my “misses”, “back at home”.

I made it up. I didn’t tell him about Jenny because there was no point. He had better live in fantasy than with the truth, because what would the truth ever get him. He’ll never know me, and I’ll never know him. Time will pull us apart and life will go on.

“Spending too much time on the road for a girl, I’ll find her one day though I’m sure”, I cleared my throat and watched the green hills blur outside, “I’m just too busy at the moment”.

This had spurred him to talk about his work again, and I listened, carefully. The world was going, moving forward like a shiny red ball; he was a dog, happily following along, tail wagging, eager to get it caught, but with no mind about whether it would ever stop. The stories went on and I let them flood my mind. Sami’s eyes cut to the left and I could tell his ears were wide open too.

We passed through town after town as the bus fluctuated with people. I waited for Sami to motion for us to depart. The excitable man next to me left shortly after his story had begun to repeat itself, and I scrambled to the window seat for Sami to move next to me.

His tired eyes scanned the bus as he moved across the aisle.

“We’ll be in Leeds soon my man. I asked him when we got on. I charged my phone too.” Each sentence was like a bullet flying by my ears. “We’re going to head to Tommo’s place and crash there for a night or two.”

This bullet landed between my eyes. I liked Sami because he led me into the future and further from the past, but everyone now and then the past would catch us up. Tommo was a university friend of ours, still living the student lifestyle despite university being far gone. His house was a den for late nights and even later mornings. Sami liked it though, it was one of the few environments where he could let himself loose to escape from his mind. Meanwhile I would be facing the very opposite effect, however sharing the same outcome.

I was staring out of the window at the approaching skyline when I felt Sami’s head slump onto my shoulder, drool hanging out of his mouth. I took this opportunity to likewise put my phone on charge and dig my notebook out of by bag. I scribbled some ingenuine verse that I knew would get published in the right places before I felt brave enough to switch my phone screen on.

Tommo had text me, ignored. My parents had too, I opened it whilst whilst massaging my temple with my empty hand.

“Hi Georgey. Hope all is well, just messaging to see how your trip is going. Your dad and I have been a bit worried, but we know you’ll be OK. We sent some money over anyhow. Lots of love xx’

I breathed a sigh of relief knowing I could eat for a bit longer and sent them a long-winded reply back that channelled my creative writing degree more than any poetry could. “What a wonderful time George is having” they would tell their friends over afternoon tea.

Leeds grew ever closer until the bus terminated in the centre of the city. Sami woke immediately and dragged me along, speaking to himself in Spanish. It was a still Spring day, the mild sun cancelled out the mild breeze. “Lunch is on you”, he said as he marched towards Tesco and I walked behind. “I’ll get us some stuff for tonight”. It was as if he saw the text from my parents.

‘Stuff’. I bought us two meal deals and waited outside watching the suits and ties pass by. The clean, white shirts reminded me of my own smelly, check shirt, reminding me to make full use of their washing machine as we got to Tommo’s.

Sami burst through the door and without pausing led the way towards the house. A bottle of rum balanced on top of a crate of beers as the offices turned into terraced houses around us.

“This is why we do it man. These kinds of nights, ohhhh it’s going to be wild”, his gaze was fixed forwards towards the hanging sun. “Tommo has invited everyone in Leeds, and Sheff too! Mike, Lewis and them lot, Anna, Jenny and Mia’s lot too. God knows who else will be there”. As his voice rode the waves of his words a bounce would be added to each step, a smirk wrapped around his cheeks.

0 notes

Text

some anecdotes, an odd poem, and incidental history

(1) some anecdotes

The other day, I was trying to find the text of an old childhood favorite poem of mine, and google just wasn’t turning it up.

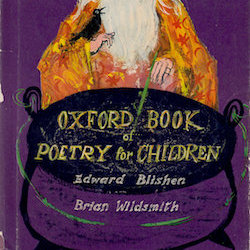

This happens to me pretty regularly. My early poetry was almost entirely from the Oxford Book of Poetry for Children, which is fantastic and gorgeously illustrated and full of the most eclectic selection of poems imaginable.

It’s got all sorts of nursery classics, of course, from Carroll (“...If seven maids with seven mops/Swept it for half a year...”) to Silverstein (“Nobody loves me/Nobody cares/Nobody picks me peaches and pears...”).

Then there’s the classics that maybe aren’t so obviously for children, like Dickinson (”I’m Nobody! Who are you? Are you -- Nobody -- Too?”) and Yeats (“The silver apples of the moon,/The golden apples of the sun”). Those seem reasonable enough once you put them with the others; “I’m Nobody! Who are you?” goes opposite Shel Silverstein’s “Nobody loves me,” with a cute silhouette of a little boy, and it seems as natural as anything to cut your teeth on Dickinson.

And then there’s the weird ones. These leave you wondering, as an adult, why someone put them into a book of poetry for children -- but as a child you don’t see anything strange about it, of course. And I tend to think it’s one of the great strengths of this book that it does include these; children have weird dark things going on inside their heads, and giving them words for those isn’t a bad thing. Still -- I wrote weird stuff, as a kid (like I don’t now, but), and it’s not hard to have some guesses why, once I look back on excerpts of what I was reading:

‘I wish the wind would blow through you,’ said Meet-on-the-Road. ‘Oh, what a wish! Oh, what a wish!’ said Child-as-it-Stood. ‘Pray, what are those bells ringing for?’ said Meet-on-the-Road. ‘To ring bad spirits home again,’ said Child-as-it-Stood. ‘Oh, then I must be going, child!’ said Meet-on-the-Road. ‘So fare you well, so fare you well,’ said Child-as-it-Stood.

‘The years passed like shooting stars, They melted and were gone, But the path itself seemed endless, It twisted and went on. ‘I followed it and thought aloud, “I’ll be found, wait and see.” Yet in my heart I knew by then The world had forgotten me.’ Frightened I turned homeward, But stopped and had to stare. I too saw that signpost with no name, And the path that led nowhere.

Yeah -- weird childhood. But fantastic -- both the childhood, and the poems. The latter really stuck with me. It didn’t hurt that they are all of genuinely excellent quality, though different kinds; obviously you can’t exactly compare Robert Louis Stevenson against Blake against “Solomon Grundy/Born on Monday...” head-to-head-to-head, but none of them are anything like bad at the thing they’re being.

Plus, it’s just really quotable poetry. Especially if your whole family’s grown up on it, so that everyone speaks the same language. I’m not sure a month of my life has gone by where I didn’t recite at someone --

Don’t Care didn’t care, Don’t Care was wild: Don’t Care stole plum and pear Like any beggar’s child. Don’t Care was made to care, Don’t Care was hung: Don’t Care was put in a pot And boiled till he was done.

(What can I say; nothing takes the wind out of a teenager’s sails like reciting that to them when they’re in the middle of a fit of pique.)

Or someone will get started off on nagging someone else with “A man of words and not of deeds/Is like a garden full of weeds/And when the weeds begin to grow/It’s like a garden full of snow,” and by the end the entire family will be reciting together for “And when your back begins to smart,/It’s like a penknife in your heart;/And when your heart begins to bleed,/O then you’re dead, and dead indeed.”

(I did mention it was weird poetry.)

There’s always late risers to be teased with “A potato clock, a potato clock/Has anybody got a potato clock?” Anyone tagging along at someone else’s heels can expect to hear “I have a little shadow that goes in and out with me/And what can be the use of him is more than I can see.” Breakfast is accompanied by the eggs poem, with quips for every way you can have them done (scrambled: “I eat as well as I am able,/But some falls underneath the table.”) Sleepy small children get “the Sugar-Plum Tree/In the garden of Shut-Eye Town” recited in full, if they’re lucky. And of course adorably bossy tiny people get tolerant recitations of “James James/Morrison Morrison/Weatherby George Dupree/Took great/Care of his Mother,/Though he was only three.”

All that to say, then: growing up in my house, this particular poetry gets under your skin. You find yourself thinking in it, at odd moments. You have quotes on the tip of your tongue and you’re not quite sure where they’re from.

So you go look them up, because it turns out that not everyone in the world knows what you’re on about when you start in on “The King asked/The Queen, and/The Queen asked/The Dairymaid...” And that one, it turns out, is Milne, and really everyone should know it; and later you discover that other poems are Blake or Lear or Yeats or Farjeon (and go “oh, that’s why I liked that one so much, no wonder”); and it’s weird and delightful to find out that these childhood poems of yours are actually the great classics of English literature.

So, yeah, half the time when you go look a poem up, yeah, it’s Auden or Wordsworth or someone, that would explain why it’s so good. (And, yeah, maybe this is why I find theories about ‘the canon is only considered so great because it is the canon’ less than compelling; for half the Great Authors out there I can remember finding them vastly, insistently fascinating well before their names meant anything to me.)

But then the other half of the time, you go look it up and it turns out there’s -- nothing. No one’s ever heard of that author. The full text of the poem isn’t even on google. And so you’re left with these lines that are written as deep in the quiet parts of your mind as this was the funeral of Hector, tamer of horses, only where you expect there to be a shared cultural construct: nothing.

The Terrible Path is one of those. It clung to my brain enough for me to end up making a setting inspired by it. It’s dark and eerie and bizarre, and the sum total the internet has to offer about it is a link from Trinity College that’ll let you download a PDF of the text. I’m not sure why it’s not better-known than it is; I’m no lit critic, but I really think it merits it.

It turns out, the one I was trying to find is another, though this one I at least have a bit of an explanation for.

(2) an odd poem

I ended up having to look it up in the same hard-copy book I read it in the first time, however long ago that was. (How twentieth-century of me, I know.) In this case, that wasn’t technically The Oxford Treasury of Children’s Poems, it was The Oxford Treasury of Story Poems, which has a slightly different selection but is much the same in spirit.

The title is Count Carrots; the author is Gerda Mayer; the one-line note says only from a Bohemian folk-tale called Rübezahl. It’s sandwiched in between Bishop Hatto (the exciting, child-friendly tale of the Wrath of God exacted in the form of the titular bishop being eaten alive by rats) and The Lady of Shalott (Tennyson, also surprisingly weird and dark).

The poem reads like a children’s poem; it’s written in a light, conversational tone. Free verse.

He’s the giant of the mountains; they call him Count Carrots. How he hates that nickname. Let me tell you how he came by it. Well -- there was that princess who -- Persephone-like -- had strayed from her companions. Perhaps you know the story.

(As far as I can tell, that right there? That’s the only place that’s been put online. This poem is nowhere.)

You can probably guess the basic outline of the narrative, just from that quote. The execution, though, is -- something else. The giant gets these odd little humanizing touches --

Some say he brought her gifts of precious stones to tempt her to love him. This is untrue, he was simpler than that. He brought her, I think, bilberries from the forest, baskets of raspberries, mushrooms, many sorts, which Bohemia excels in, and clumsy importunings, day after day.

And there are beautiful morsels of description, serving no purpose at all but to be there:

The fact is -- to paddle your feet in a mountain stream, shallow and fast and cold as molten ice, water which rushes and swirls over white pebbles, -- to paddle your feet in this on a hot day is pleasant and delightful: to wash in it, day after day, indubitably cold. So the princess had discovered.

The tone, already, is getting strange. This should be straightforward -- kidnapped princess, evil giant -- but there’s something bittersweet about every part of it: about the giant who’s really trying to please her, about the homesick princess, about her parents --

‘What shall we tell them at home?’ And who will comfort ever the queen in tears, the king in despair?

And then it gets weird.

The princess is lonely. The giant brings her a basketful of carrots from his garden, and explains that they’ll be magically transformed into “whomever, whatever, you wish.”

The princess wishes up her puppy and her friends and her retinue, and she’s happy again. (“She was gracious to the giant. She didn’t see much of him.”)

Then, on the third morning, they start to wilt -- her horse first, then her friends -- stumbling, their flesh shrunken, pale, complaining of headaches, dead in a ditch -- and, finally, carrots again.

(This is -- kind of horrifying, right? It’s not just me?)

The princess goes to the giant. The giant promises to bring her fresh carrots each day, to replace them as they wilt. This satisfies her for a while, but then she feels uneasy, so she comes up with a clever escape plan: she worries aloud that the giant might run out of carrots, and begs him to count them. While he’s distracted, she wishes up a pair of horses and a companion and rides home.

The ending is about as bittersweet and strange as you’d imagine from the rest:

Henceforth, the giant was called Count Carrots by all; a nickname he hates, as I told you at the beginning. Woe to him who so calls him in mischief. Let the impudent traveller, shouting his name, beware.

When I was small, I called his name into the forest: ‘Count Carrots! Count Carrots!’ then leapt into bed, half in fear. He didn’t come for me though. Could it be that perhaps he forgave me? He loves children, they say. -- May the forest stay green for him ever.

(3) incidental history

If you’re anything like me -- which, I acknowledge, is a bit of a leap -- this leaves you with two questions. One is: what was up with that poem? And two is: why has the internet never heard of it? (There are, after all, all sorts of poem archives online. Why does this one show up nowhere?)

I don’t have a really good answer to either question, but I have one answer, which split between them makes for maybe half an answer to each.

That answer is in the author. Gerda Mayer: Jewish, Czechoslovakian, born 1927.

It doesn’t take much to do that math. She was eleven in 1939, at the start of World War Two, whereupon Czechoslovakia was not such a good place to be a little Jewish girl. Gerda was (though one hates to use the word) lucky enough to find a place on a Kindertransport to England.

She’d stay in touch with her parents, writing them letters -- them still in Nazi-occupied territory, her off in England. Mayer, much later, writes about the experience:

I am on a raft and they are in a choppy sea. I am eleven, possibly just turned twelve, and they cry out to me -- though in the politest possible way -- ‘If you should happen to have a lifeline or lifebelt on the raft, if it is not too inconvenient...’ It is a forlorn hope. Their heads bob on the surface and the waves grow higher and higher.

Reading an excerpt from one of her mother’s letters, you can see what Mayer is talking about:

Under no circumstance do I want you to bother your benefactors who have already done so much for you; but if you should meet someone who strikes you as particularly kind...

Little Gerda never was able to find someone particularly kind. Her mother would die in Auschwitz; her father, in a camp somewhere in Russia. Mayer writes:

My father went hiking without pass- port or visa and was intercepted My sister went mad my mother went into that Chamber trusting in God God picked the bones clean they lie without imprint or name dear mother

By this time, at eleven-or-maybe-twelve, Gerda had already been writing poetry for some time, and shown a distinct talent (though notable, perhaps, only to her parents as yet). Her first poem was written at age four (as any number of biographies available online attest), and saved by said parents in a “Baby’s Diary”.

(None of the online sources include a copy of the poem, as far as I can tell, but full scans of the diary are available online via the Center for Jewish History Digital Collections. My German might be up to the task of translating a four-year-old’s poem, but unfortunately it is definitely not up to deciphering her father’s cursive. If anyone else wants to give it a shot, pages 117 to 124 are dated from 1931-2, when she would have been four, so it should be somewhere in there.)

In any case, Mayer herself says that her poetry suffered severely as a result of the change in language. In a letter written at the request of, and published in, a poetry magazine, she says:

I was born in the Sudeten, the once-German-speaking part of Czechoslovakia. I came over at the age of eleven and, as I was surrounded by English speakers, my reading had caught up with my own age group before three months were out. In any case, I was reading Browning’s Pied Piper to myself and, came the summer holidays, What Katy Did. Conversely, my mother, in a letter from Prague, fretted that my German was deteriorating. If I had caught up linguistically, poetically there was a time-lag. My first English poem, written at the age of twelve was no better than one I had composed (in my pre-literacy days) at the age of four (proud parents had entered this into my ‘Baby’s Diary’) and a poem I wrote at the age of sixteen was on a level with one I had written at the age of eleven, just before leaving home.

This seems to me the most satisfying explanation available for why Mayer never became more famous than she has. It really doesn’t seem to be a lack of skill; the introduction to her Wikipedia article has Britian’s poet laureate praising her as a fine poet “who should be better known.”

Rather, Mayer is limited by writing in a second language (and one she learned late, at that -- eleven is old to be learning a new language). She compensates for this to some degree for writing children’s, and childish, poetry, where maybe a gift for vivid imagery and tone can compensate for the linguistic handicaps of writing in a second language (poetry! in a second language! I can’t get over how impressive that is to do at all).

Hence we have Count Carrots, which is effective partly because it’s really an adult poet, writing about adult topics, but using the format of children’s poetry; hence also we have commentary on her repertoire like this from Peter Lawson:

Although some of Mayer’s poems are aimed specifically at children, other collections feature what Peter Porter describes as ‘children’s rhymes for grown-ups’. Such poems juxtapose, in the lilt of nursery rhymes, the tentatively self-assured perspectives of children with adult knowledge of the murder of innocents in the Holocaust.

And Mayer absolutely makes this work for her. A characteristic ‘children’s rhyme for grown-ups’:

Grandfather’s house rose up so tall, Its steps were like a waterfall It had a deep stairwell, as I recall.

And down the banisters slid my mother, And her sisters, and her brother, And many a child, many another.

The banisters wobbled and down fell all. Down down, down, and beyond recall. And so I was not born at all.

Better it is not to have been, Than to have seen what I have seen. So deck their graves with meadow-green.

Or again:

The children are the candles white, Their voices are the flickering light.

The children are the candles pale, Their sweet song wavers in the gale.

Storm, abate! Wind, turn about! Or you will blow their voices out.

Mayer gets compared to Plath (doing her an injustice, I think, but I’m not overly fond of Plath) and to Blake (much fairer, in my opinion). But she’s nothing like as famous as either -- will probably never be famous, except for her story -- and I think that can be chalked up to the linguistic hobbles she’s working under.

But those don’t prevent her from writing truly great children’s poetry -- and Mayer knows that, and the Oxford editors, evidently, knew that, because the strange beautiful haunting Count Carrots somehow made it into my book of children’s verse.

193 notes

·

View notes