#lord holdhurst

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

“#It's beginning to look like I'm right, #But that's absolutely nothing to do with my problem solving ability and everything to do with my natural paranoia and distrust, #Also ACD has a type, #We saw it in The Copper Beeches and in The Greek Interpreter, #Men who laugh too much and smile too easily”

The Naval Treaty pt 3

Yes, we apparently have got to the point where I'm memeing myself.

Right, last time, after Percy, Watson's old 'pal' from school failed magnificently at understanding how to protect confidential data, he followed an old woman into the night and the stress gave him a brain fever. Meanwhile, I'm still certain that Joseph Harrison, who has not been implicated in any way, is involved because I am a well-balanced and entirely reasonable person.

Mr. Joseph Harrison drove us down to the station

See! He's trying to get rid of you! 🤣🤣😂

“It's a very cheery thing to come into London by any of these lines which run high, and allow you to look down upon the houses like this.”

Last time we had Holmes looking out a train window: Ugh, look how terrible the countryside is! I can't bear it.

The contrast is palpable.

“The board-schools.” “Light-houses, my boy! Beacons of the future! Capsules with hundreds of bright little seeds in each, out of which will spring the wise, better England of the future. I suppose that man Phelps does not drink?”

Board schools are not the same as boarding schools, the internet tells me, but the first state run schools with no religious affiliation. I was about to be cynical about Holmes' view of children and Victorian educational standards, but I can't. He's right, those schools were important and really did pave the way for a brighter future.

And then a bit of mental whiplash as he snaps back to the case at hand, because he's Holmes.

In answer to the question, I can't say whether Percy drinks alcohol, but he definitely has a caffeine addiction that he should work on. If not for that, he wouldn't be in this mess.

Also, it was unreasonable of his uncle to expect him to copy so much text in a foreign language in one night. But even so, Percy needs to work harder on curbing his need for coffee.

"Then came the smash, and she stayed on to nurse her lover, while brother Joseph, finding himself pretty snug, stayed on too."

Oh, so he's just hanging around leeching off people, huh? Exactly as I suspected! This is just the beginning. Clearly, he's been a wrong'un all along and I will be vindicated.

"But to-day must be a day of inquiries.” “My practice—” I began. “Oh, if you find your own cases more interesting than mine—” said Holmes, with some asperity.

First of all, Watson does have a job, Holmes. I get that you want to play with him, but he does have responsibilities. You really shouldn't be bitchy about that.

Second, if Watson actually cares enough about his patients to ditch you, that would be the first time ever.

“I was going to say that my practice could get along very well for a day or two, since it is the slackest time in the year.”

See. No problem at all. Why would Watson ever do his actual job when he could be running around with Holmes? What a preposterous idea!

"...there is Lord Holdhurst.” “Lord Holdhurst!” “Well, it is just conceivable that a statesman might find himself in a position where he was not sorry to have such a document accidentally destroyed.” “Not a statesman with the honorable record of Lord Holdhurst?”

Oh Watson, my sweet summer child. Out there believing in unicorns and fairies and honourable politicians.

I discounted him because honestly, a political plot involving the politician uncle and corruption seemed too spy thriller. Also, the time frame of everything being nine weeks ago, I think discounts a political motive because if there were spy games going on, it would be far too late to do anything about it. Of course, it might be the case. These stories have surprised me a few times so far.

“£10 reward. The number of the cab which dropped a fare at or about the door of the Foreign Office in Charles Street at quarter to ten in the evening of May 23d. Apply 221b, Baker Street.”

The Bank of England inflation calculator tells me that's equivalent to approximately £1000 today, which is a pretty impressive reward for a little bit of information. Honestly, I'd expect people to be climbing out of the woodwork to say they saw Queen Victoria herself driving the cab and dropping off Jack the Ripper.

"Why yes, Mr Holmes, I saw a man with a long white beard and carrying a large sack. No, it was right odd, y'see: he didn't go in through the door. He climbed up on' roof and went down the chimney, that he did."

"And then, of course, there is the bell—which is the most distinctive feature of the case. Why should the bell ring?"

This is what I'm most interested in. What is up with that bell?

He sank back into the state of intense and silent thought from which he had emerged; but it seemed to me, accustomed as I was to his every mood, that some new possibility had dawned suddenly upon him.

Tell me! Tell me! I need to know. The bell is plaguing me.

a small, foxy man with a sharp but by no means amiable expression.

So Lestrade is a ferret and Forbes is a fox. Must all police officers be described as animals? This appears to be a pattern.

“You are ready enough to use all the information that the police can lay at your disposal, and then you try to finish the case yourself and bring discredit on them.” “On the contrary,” said Holmes, “out of my last fifty-three cases my name has only appeared in four, and the police have had all the credit in forty-nine. I don't blame you for not knowing this, for you are young and inexperienced, but if you wish to get on in your new duties you will work with me and not against me.” “I'd be very glad of a hint or two,” said the detective, changing his manner.

Forbes changes his tune pretty quickly here, so he seems open minded enough. Although it does seem a bit like he doesn't understand the purpose of Holmes. Yes, he's supposed to take all the evidence the police give him and try to solve the case. That's kind of how being a detective works. I get the emphasis here is on 'yourself', but still.

I like this exchange, because we've already seen in the stories that Holmes really doesn't care about the notoriety or the accolades - though he's more than willing to display gifts he's given in his own home - it's entirely the case and helping the people involved that he cares about.

Not sure he really needed to say that 'you are young and inexperienced' bit, though. Seems a tad direct.

“We have set one of our women on to her. Mrs. Tangey drinks, and our woman has been with her twice when she was well on, but she could get nothing out of her.”

OK, I thought it sounded unlikely that there were female police officers in the late 1800s, and it seems like the first female police officer in London was in 1919. But it definitely appears from this that they have women working for them - unless one of them has set his wife on a suspect, which... fair. Fascinating either way.

Also, Mrs Tangey has an alcohol problem, that could be an angle.

“What explanation did she give of having answered the bell when Mr. Phelps rang for the coffee?” “She said that he husband was very tired and she wished to relieve him.”

Alright, so it either was her, or she's involved in some way. Which I think we already suspected, but this clarifies that no one impersonated her without her knowledge, at least.

“Did you point out to her that you and Mr. Phelps, who started at least twenty minutes after he, got home before her?” “She explains that by the difference between a 'bus and a hansom.”

That's fair. Not everyone can afford their own taxi. Check your privilege, Holmes.

Standing on the rug between us, with his slight, tall figure, his sharp features, thoughtful face, and curling hair prematurely tinged with gray, he seemed to represent that not too common type, a nobleman who is in truth noble.

I may have rolled my eyes at this bit. Watson sometimes needs to back off on his earnest belief in the glory of England and its political and social systems. He's so classist it's actually painful at some points. Even if he's saying the type is 'not too common' it just makes me wrinkle my nose.

I also don't like Lord Holdhurst, but that's mainly because I believe hereditary nobility is immoral and also because he is a tory politician. There was never any hope of me liking him. I don't think he murders puppies, but I bet he'd pass legislation saying that murdering puppies is okay in certain circumstances if his old chum wanted to start a puppy murdering business and was a generous donor.

"I fear that the incident must have a very prejudicial effect upon his career.”

Yeah, that I do agree with.

“But if the document is found?” “Ah, that, of course, would be different.”

This, I do not agree with. Not after nine weeks, anyway. If it had been a couple of hours and the document was found to have fallen down the gap between the desk and the wall then he could probably just be given extra training and not allowed to touch confidential documentation without supervision for a few years. But it's been nine weeks. That treaty is lost. Even if it's returned, he still lost it for nine weeks.

“Did you ever mention to any one that it was your intention to give any one the treaty to be copied?” “Never.” “You are certain of that?” “Absolutely.”

OK. That cuts off that line of thinking, as Watson's insistence on him looking 'noble' clearly means we're supposed to believe him. But we already knew it wasn't him.

Because it's Joseph Harrison.

“If the treaty had reached, let us say, the French or Russian Foreign Office, you would expect to hear of it?” “I should,” said Lord Holdhurst, with a wry face.

Like I say, any political motivations would have been thoroughly completed by now, before Holmes was even called upon, so that's not likely.

“Of course, it is a possible supposition that the thief has had a sudden illness—” “An attack of brain-fever, for example?”

Given he called Holmes in, I sincerely doubt Percy's involved. Again, if this weren't a Sherlock Holmes story, there's a slim possibility it could be that his brain fever cause amnesia meaning that he doesn't remember taking the treaty and causing the whole problem, but that doesn't seem like a likely plot here.

“But he has a struggle to keep up his position. He is far from rich and has many calls. You noticed, of course, that his boots had been re-soled?"

OK so now we give him a motive, when you've all just gone on about how he's a 'fine fellow'? Are Lord Holdsworth's money problems going to be relevant to the plot? Maybe. We've heard nothing of Percy having any cousins, so as it stands he might be his uncle's heir. Not sure how that would lead to the treaty being stolen, but we'll bear it in mind.

Ah, and then Watson is racist again. Native Americans this time. These stories are really trying to spread the racism around, aren't they. This whole section is strange though, because it's about how Watson can't read Holmes' face, when multiple times (in this very story) he's said how he knows Holmes so well that he can instantly tell from his face what Holmes is thinking.

“God bless you for saying that!” cried Miss Harrison. “If we keep our courage and our patience the truth must come out.”

She and Watson should get together and have optimist meetings.

Although, it's definitely your brother, Miss Harrison. I don't know how, but it is. It's got to be. We're running out of suspects. Mrs Tangey seems like she might be involved, but I doubt she's the mastermind behind events.

Maybe Joseph just bribed her into trying to discredit Percy, she saw the paper and thought 'well this looks important' and took it not really knowing what it was.

But that doesn't explain the bell. Unless it's because she was drunk and she stumbled and grabbed it. Or she didn't really want to be doing it, so she pulled it in a weird attempt to get caught. Or she let Harrison in and then saw him stealing something and pulled the bell, only to be threatened if she said anything.

“Yes, we have had an adventure during the night, and one which might have proved to be a serious one.” His expression grew very grave as he spoke, and a look of something akin to fear sprang up in his eyes. “Do you know,” said he, “that I begin to believe that I am the unconscious centre of some monstrous conspiracy, and that my life is aimed at as well as my honor?”

He's probably right to be worried - maybe not for his life, but I'm pretty sure this entirely thing is aimed at him, not the treaty. But at the same time, this does not sound like the thinking of a mentally healthy person.

"A man was crouching at the window."

No. No, you see it could be him. Of course you're going to want to make it seem like it was someone from outside forcing their way in. To keep the suspicion off the people who live in the house. It has to be him. Has to be.

Did he have a knife, or was it just something that looked like a knife... like...

uh...

The thing he used to unlock the window?

"As it was, I rang the bell and roused the house. It took me some little time, for the bell rings in the kitchen and the servants all sleep upstairs. I shouted, however, and that brought Joseph down, and he roused the others."

Oh oh... convenient, being the first person on the scene, huh? Was that because you weren't in bed asleep at all? Mr Joseph Harrison?

(If I am by some miracle right about this, it will be entirely undeserved as literally the only reason I decided it was him is because he seemed too happy and his sister is getting married)

"There's a place, however, on the wooden fence which skirts the road which shows signs, they tell me, as if some one had got over, and had snapped the top of the rail in doing so."

Okay... well... well... that doesn't really fit with my theory at all, but maybe it's a coincidence. People climb over fences all the time. Maybe it happened ages ago. I bet they don't check the fences every day. Totally not a sign I'm wrong.

“Oh, yes, I should like a little sunshine. Joseph will come, too.”

Why?

No, seriously. Why? Percy says Joseph will come, but not his fiancee? That's weird. Is it because Joseph is stronger if Percy needs to be carried back?

"I should have thought those larger windows of the drawing-room and dining-room would have had more attractions for him.” “They are more visible from the road,” suggested Mr. Joseph Harrison.

And right here we have the classic Columbo moment. I know Sherlock Holmes came first, no need to send me angry messages. But this is something that happens in Every. Single. Columbo. It's part of his method, it's kind of his whole method. He makes a comment about 'I wonder why the murderer didn't do x' to the person he (and the audience) knows is the murderer and the villain, in an attempt to cover their own tracks, immediately presents an explanation.

“Do you think that was done last night? It looks rather old, does it not?” “Well, possibly so.”

Aw shucks, is Holmes not falling for your clever ruse? What a pity!

“Miss Harrison,” said Holmes, speaking with the utmost intensity of manner, “you must stay where you are all day. Let nothing prevent you from staying where you are all day. It is of the utmost importance.” “Certainly, if you wish it, Mr. Holmes,” said the girl in astonishment.

Not the weirdest thing Holmes has ever asked a person to do - still remember Watson pretzeling himself behind the headboard that one time - but still kinda weird. I hope she has some sort of enrichment in her enclosure. Tell me she has a bookcase at least.

“Why do you sit moping there, Annie?” cried her brother. “Come out into the sunshine!”

Look! LOOK! He's trying to get her out of the room. He hid the treaty in the room and now he's trying to get it back but he can't! All aboard the Joseph Harrison train, next stop: Vindication.

Got to assume that even though Joseph wasn't present when Holmes was speaking to Anne, or when he was speaking to Percy, he will be aware that Percy is not in the house. But he'll only be able to break into the room by the window again, so I guess that is the plan. To catch him red-handed.

#Literature#Sherlock Holmes#Letters From Watson#john watson#dr watson#percy phelps#lord holdhurst#joseph harrison#annie harrison#inspector forbes#mrs tangey

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

I hate hate hate Holmes adaptations that make him invincible Need I remind you:

"His words were cut short by a sudden scream of “Help! Help! Murder!” With a thrill I recognised, I rushed madly from the room on to the landing. The cries, which had sunk down into a hoarse, inarticulate shouting, came from the room which we had first visited. I dashed in, and on into the dressing-room beyond. The two Cunninghams were bending over the prostrate figure of Sherlock Holmes, the younger clutching his throat with both hands, while the elder seemed to be twisting one of his wrists. In an instant the three of us had torn them away from him, and Holmes staggered to his feet, very pale and evidently greatly exhausted." (Reigate Squires) "With this permission I stole into the darkened room. The sufferer was wide awake, and I heard my name in a hoarse whisper. The blind was threequarters down, but one ray of sunlight slanted through and struck the bandaged head of the injured man. A crimson patch had soaked through the white linen compress. I sat beside him and bent my head. “All right, Watson. Don’t look so scared,” he muttered in a very weak voice. “It’s not as bad as it seems."" (Illustrious Client) "Holmes’s quiet day in the country had a singular termination, for he arrived at Baker Street late in the evening with a cut lip and a discoloured lump upon his forehead, besides a general air of dissipation which would have made his own person the f itting object of a Scotland Yard investigation. He was immensely tickled by his own adventures, and laughed heartily as he recounted them." (Solitary Cyclist) "“My collection of M’s is a fine one,” said he. “Moriarty himself is enough to make any letter illustrious, and here is Morgan the poisoner, and Merridew of abominable memory, and Mathews, who knocked out my left canine in the waitingroom at Charing Cross, and, finally, here is our friend of to-night.”" (Empty House) "Well, he has rather more viciousness than I gave him credit for, has Master Joseph. He flew at me with his knife, and I had to grasp him twice, and got a cut over the knuckles, before I had the upper hand of him. He looked murder out of the only eye he could see with when we had finished, but he listened to reason and gave up the papers. Having got them I let my man go, but I wired full particulars to Forbes this morning. If he is quick enough to catch his bird, well and good. But if, as I shrewdly suspect, he finds the nest empty before he gets there, why, all the better for the government. I fancy that Lord Holdhurst for one, and Mr. Percy Phelps for another, would very much rather that the affair never got as far as a police-court" (Naval Treaty) ".... Of course I knew better, but I could prove nothing. I took a cab after that and reached my brother’s rooms in Pall Mall, where I spent the day. Now I have come round to you, and on my way I was attacked by a rough with a bludgeon. I knocked him down, and the police have him in custody; but I can tell you with the most absolute confidence that no possible connection will ever be traced between the gentleman upon whose front teeth I have barked my knuckles and the retiring mathematical coach, who is, I dare say, working out problems upon a black-board ten miles away...." (Final Problem) Plus he fought the boxer McMurdo (prior to the events of the Sign of Four) so he must have gotten hit then too

348 notes

·

View notes

Text

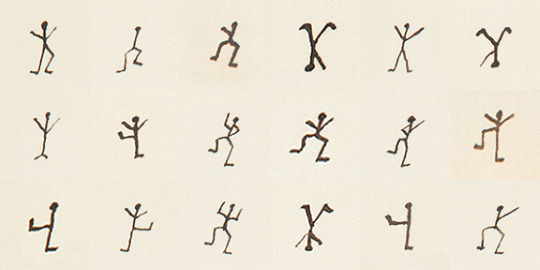

Left: “A nobleman.” Naval Treaty, Sidney Paget, The Strand Oct/Nov-Nov/Dec 1893 Characters: Holmes, Lord Holdhurst, Watson

Right: [The Dancing Men Cyphers] Dancing Men, ACD, The Strand Dec 1903

#acd holmes#sherlock holmes#tumblr bracket#sherlock holmes illustrations#polls#R1#fwiw technically sidney paget Also drew a lot of the dancing men for the actual quotes in the strand printing#but acd made the glyphs so#polls full bracket

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Letters from Watson: The Naval Treaty

Part 1: The Fun Bits

Watson cites The Second Stain as also occurring this month.

This almost lines up with my own conclusions regarding the date of The Second Stain, (I pegged it as prior to Watson's marriage, so 1988 at latest) but there are frankly a lot of similarities between the two cases.

Lord Holdhurst: Yet another fictitious noble, this time probably based on prime minister Robert Gascoyne-Cecil. again.

Brain fever is another diagnosis that covers all the ground in the world, as I covered in The Musgrave Ritual, but in this case I'm pretty confident that it's primarily covering Tad Phelps' mental health, despite the mention of physical weakness. His life is crumbling in front of his eyes. A stress related breakdown can also intensify anything else that might coincidentally be wrong with you, especially in a pre-antibiotic world full of industrial pollution and zero moderation in consuming tobacco or alcohol.

Also if you're experiencing a lot of panic attacks (probable given the cited "state of horrible suspense") exerting yourself in any way feels a hell of a lot like there's a new panic attack rolling in.

Between The Man with the Twisted Lip and this story, we get a picture of Mary as Mrs. Watson: fully supportive of anything her husband can do as either a friend or a doctor or an upstanding citizen to help just about anyone. Whether it's accompanying Holmes out to the countryside (and making sure that he isn't alone and trying to deal with a sick and anxious nobleman during the investigation) or late night trips to haul people out of opium dens.

Holmes' use of litmus paper is not going to become relevant to this case, but apparently commercial production of litmus paper had been occurring for several decades before 1888. It's also very possible to make your own from specific lichens.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

“#I've gotta be right eventually”

Oh, now that's a theory!

Although the fact he's saying it straight to Holdhurst's face makes me think it's a red herring. I think he's trying to make Holdhurst suspect Percy, so he can catch him (the lord) in the act.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Back to the Naval Treaty! Once again I LOVE the contrast that comes up between Holmes and Watson between a few lines:

“Well, it is just conceivable that a statesman might find himself in a position where he was not sorry to have such a document accidentally destroyed.”

“Not a statesman with the honorable record of Lord Holdhurst?”

“It is a possibility and we cannot afford to disregard it.”

And later, when Watson meets the man:

Standing on the rug between us, with his slight, tall figure, his sharp features, thoughtful face, and curling hair prematurely tinged with gray, he seemed to represent that not too common type, a nobleman who is in truth noble.

Watson is, once again, judging from appearances. Before they even start talking he’s decided that Lord Holdhurst is noble in character. Compare that to Holmes earlier, who shocks Watson by not excluding Lord Holdhurst just because of his reputation.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

We were fortunate in finding that Lord Holdhurst was still in his chambers at Downing Street, and on Holmes sending in his card we were instantly shown up.

"The Illustrated Sherlock Holmes Treasury" - Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

#book quotes#the adventures of sherlock holmes#sir arthur conan doyle#the adventure of the naval treaty#fortunate#john watson#sherlock holmes#chambers#downing street#introductions

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

There are a few passages from ACD that have nothing at all to do with Mycroft that give me strong BBC Mycroft vibes:

During my school-days I had been intimately associated with a lad named Percy Phelps, who was of much the same age as myself, though he was two classes ahead of me. He was a very brilliant boy, and carried away every prize which the school had to offer, finished his exploits by winning a scholarship which sent him on to continue his triumphant career at Cambridge. He was, I remember, extremely well connected, and even when we were all little boys together we knew that his mother’s brother was Lord Holdhurst, the great conservative politician. This gaudy relationship did him little good at school. On the contrary, it seemed rather a piquant thing to us to chevy him about the playground and hit him over the shins with a wicket. But it was another thing when he came out into the world. I heard vaguely that his abilities and the influences which he commanded had won him a good position at the Foreign Office[.] - Doyle, "The Naval Treaty" in The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes.

I was, of course, familiar with the pictures of the famous statesman, but the man himself was very different from his representation. He was a tall and stately person, scrupulously dressed, with a drawn, thin face, and a nose which was grotesquely curved and long. His complexion was of a dead pallor, which was more startling by contrast with a long, dwindling beard of vivid red, which flowed down over his white waistcoat with his watch-chain gleaming through its fringe. Such was the stately presence who looked stonily at us from the centre of Dr. Huxtable’s hearthrug. - Doyle, "The Adventure of the Priory School" in The Return of Sherlock Holmes.

OK the last one is not spot on and a bit generic but like, if you read the entire story it's clear that this is quite the ice man.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Granada TV Series Review: "The Naval Treaty" (S01 E03)

I would like to start this review off by stating (again) how much I love David Burke's portrayal of Watson in this first season of The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes! Right at the beginning, when he says, "You're interested!" the playful smile on his face makes me think that he has perfectly captured the excitement that makes Watson want to be Holmes's biographer. I was also pleased that the writers of the episode managed to keep some snippets from Watson's delightful introduction to the case:

...it seemed rather a piquant thing to us to chevy him about the playground and hit him over the shins with a wicket.

In the original story, this is a humorous line that Watson writes, but does not say out loud to Holmes. It made me smile to read it, and it made me smile even more to hear Watson say it. But I digress...

Another one of my favorite moments in the story is when Holmes and Watson meet Mr. Joseph Harrison. When Holmes deduces (without being told his name) that Mr. Harrison is not a member of the family, Harrison figures out immediately that Holmes had caught a glimpse of his JH monogram. Harrison, unlike most characters in the canon who are witness to the detective's ability to instantly make surprising deductions, is particularly unimpressed, remarking, "For a moment I thought you had done something clever." In the adaptation, Jeremy Brett responds to this criticism with the slightest raise of an eyebrow. It's a tiny detail, but I love it.

I'm afraid I can't help but be a bit entertained, reading the original story and watching this adaptation, by Percy Phelps's case of the good ol' Victorian plot device of "brain fever." I understand having a nervous breakdown because of an enormous setback in one's government job, but the sight of this posh British chap in his dressing gown succumbing to an attack of "the vapors" (as his fiancée dabs his brow) is more than a little comical. After all, the event had taken place two months ago, and the guy has been an invalid the whole time! Meanwhile, Holmes just looks on, almost completely unsympathetic.

Holmes's "flower monologue," after he has heard the details of Percy's case is an odd thing to read, but even more odd to see on screen. (The "flower cam" that show the flower from Holmes's point of view is unintentionally hilarious.) Miss Harrison is clearly not at all pleased with the great detective's seeming lack of interest in the case, a displeasure which is conveyed very clearly in the set of the actress's jaw. One can hardly blame her, I suppose...

The "flower cam" is not the only unusual shot in the episode. I was struck by the composition of this shot of Holmes and Watson discussing the case after leaving poor Percy.

"Hey, I've got an idea! Let's shoot the actors through a window, with two candle holders in the foreground. Won't that look great?" (Hint: it doesn't.) And that's not the only bizarre camera work in the episode: when Holmes and Watson are interviewing Lord Holdhurst, the camera inexplicably pans to a point of view where the actor is almost completely hidden by the chandelier. Later in the episode, Holmes's violent encounter with the villainous Mr. Harrison is filmed in a rather strange sort of slow-motion sequence. (Interestingly, Holmes can be seen to carry a sword concealed in his walking stick.) Very bizarre direction...

Still, despite some of the odd camera work, and some rather slow pacing, I am still incredibly impressed by how good Jeremy Brett and David Burke are in their roles. The camaraderie between the two characters, the little details each actor inserts into his portrayal, it all adds up to a delightful presentation of one of literature's most famous friendships. As usual for the Granada series, the costumes are top-notch, as are the overall production values.

Overall, it's not my favorite episode, but it was mostly enjoyable to watch. It's a decent adaptation of a lengthy story with a surprisingly anti-climactic ending. While it can't compare to a more exciting adventure (such as, say, "The Dancing Men"), it is still well worth watching, mostly in order to see Brett and Burke at the top of their game.

youtube

0 notes

Text

He was, I remember, extremely well connected, and even when we were all little boys together, we knew that his mother's brother was Lord Holdhurst, the great Conservative politician.

"The Illustrated Sherlock Holmes Treasury" - Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

#book quote#the adventures of sherlock holmes#sir arthur conan doyle#the adventure of the naval treaty#reminiscing#classmate#connections#uncle#family relations#conservative politics#politician

0 notes

Text

this is Very Accurate

The Naval Treaty episode isn’t about the story, it is about Jeremy Brett running around looking very dashing in a cream suit

#THE CREAM SUIT#Sherlock Holmes#Jeremy Brett#NAVA#(also the formal suit for meeting Lord Holdhurst was a Look; so quickly to be overshadowed by the legendary cream suit :D )#Granada Holmes

231 notes

·

View notes

Text

But it was a weary day for me. Phelps was still weak after his long illness, and his misfortune made him querulous and nervous. In vain I endeavored to interest him in Afghanistan, in India, in social questions, in anything which might take his mind out of the groove. He would always come back to his lost treaty, wondering, guessing, speculating, as to what Holmes was doing, what steps Lord Holdhurst was taking, what news we should have in the morning. As the evening wore on his excitement became quite painful. — ‘The Naval Treaty’

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

~Doctor Watson~

Doctor Watson : Prolegomena to the study of biographical problem, with a bibliography of Sherlock Holmes is a study written by S. C. Roberts first published in 1931 by Faber & Faber Ltd. (Criterion Miscellany No. 28).

Part I 'As in every phenomenon the Beginning remains always the most notable moment; so with regard to any great man, we rest not till, for our scientific profit or not, the whole circumstances of his first appearance in this Planet, and what manner of Public Entry he made, are with utmost completeness rendered manifest.' So wrote Carlyle, an author from whose voluminous works quotations would readily fall from the lips of Dr. Watson himself. But to render manifest the whole circumstances of Watson's first appearance in this planet is a task before which Boswell himself might well have quailed. Certainly Boswell might have run half over London and fifty times up and down Baker Street with very little reward for his trouble. Where were the friends or relatives who could have given him the information about Watson's early life? 'Tadpole' Phelps might have given a few schoolboy anecdotes; young Stamford might have been traced to Harley Street or some provincial surgery, and have talked a little about Watson at Bart.'s; his brother had been a skeleton in the family cupboard; his first wife, as seems probable, died some five or six years after marriage; Holmes himself might have deduced much but, except in the famous instance of the fifty-guinea watch, seldom concerned himself with Watson's private affairs. The young Watson, in short, is an elusive figure. 'Data, data, give us data,' as Holmes might have said. Since he took his doctor's degree at the University of London in 1878, Watson's birth may with a fair measure of confidence be assigned to the year 1852. [1] The place of his birth is wrapped in deeper mystery. At first sight the balance of evidence seems to point to his being a Londoner; much of his written work, at any rate, conveys the suggestion that he was most fully at home in the sheltering arms of the great metropolis: Baker Street, the Underground, hansom cabs, Turkish baths, November fogs — these, it would seem, are of the very stuff of Watson's life. On the other hand, when, broken in health and fortune, Watson stepped off the Orontes on to the Portsmouth jetty, he 'naturally gravitated to London, that great cesspool into which all the loungers and idlers of the Empire are irresistibly drained.' It is difficult to believe that Watson, in whose veins there flowed a current of honest sentiment, could thus have described his native city. On the whole, we incline to the view that he was born either in Hampshire or Berkshire; it was as he travelled to Winchester [2] ('the old English capital', as he nobly calls it) that he was moved by the beauty of the English countryside: 'the little white fleecy clouds... the rolling hills around Aldershot, the little red and grey roofs of the farm-steadings peeping out from amidst the light green of the new foliage'. 'Are they not fresh and beautiful?' he cried out to Holmes... Again, Watson chafed at an August spent in London. It was not the heat that worried him (for an old Indian campaigner, as he said, a thermometer at 90° had no terrors); it was homesickness: he 'yearned for the glades of the New Forest or the shingle of Southsea...' [3] Concerning his parents Watson preserves a curious silence. That his father (H. Watson) was or had been, in comfortable circumstances may fairly be inferred from his possession of a fifty-guinea watch, and from his ability to leave his elder son with good prospects and to send his younger son to a school whence young gentlemen proceeded to Cambridge and the Foreign Office. Watson's reticence about his elder brother is hardly surprising: squandering the legacy bequeathed to him by his father he lived in poverty, 'with occasional short intervals of prosperity'. Possibly he was an artist who occasionally sold a picture; more probably he was a gambler. In any event, he died of drink round about the year 1886. [4] Concerning Watson's boyhood two facts stand out clearly: he spent a portion of it in Australia, and he was sent to school in England. The reference to Australia is categorical. As he stood hand-in-hand with Miss Morstan in the grounds of Pondicherry Lodge, 'like two children', as he significantly says, the scenes of his own childhood came back to him: 'I have seen something of the sort on the side of a hill near Ballarat, where the prospectors had been at work'. In all probability, then, the period of Watson's Australian residence was before he reached the age of 13. [5] No reader of Watson's narrative can have failed to notice his curious treatment of his mother. [6] The explanation must surely lie in Mrs. Watson's early decease — probably very soon after her second son's birth. It is, perhaps, a little more fanciful — though not, surely, fantastic — to surmise that she was a devout woman with Tractarian leanings, and that before her death she breathed a last wish into her husband's ear that the child should be called John Henry, after the great Newman himself. Unable to face life in the old home, Watson père set out to make a new life in Australia, taking his two young children with him. Whether he had good luck in the gold-fields round Ballarat or in other spheres of speculative adventure, it is evident that he prospered. Of the influence of this Australian upbringing on the character of Doctor Watson we have abundant evidence: his sturdy common sense, his coolness, his adaptability to rough conditions on Dartmoor or elsewhere are marks of that tightening of moral and physical fibre which comes from the hard schooling of colonial life. Londoner as he afterwards became, Watson was always ready to doff the bowler hat, to slip his revolver into his coat pocket, and to face a mystery or a murder-gang with a courage which was as steady as it was unostentatious. But to return to Watson's boyhood: that he was sent to one of the public schools of England can hardly be doubted, since one of his intimate friends was Percy Phelps, 'a very brilliant boy' who, after a triumphant career at Cambridge, obtained a Foreign Office appointment. He was 'extremely well connected'. 'Even when we were all little boys together,' writes Watson, 'we knew that his mother's brother was Lord Holdhurst, the great Conservative politician.' But Watson's sturdy colonialism was proof against the insidious poison of schoolboy snobbery, and took little account of Phelps's 'gaudy relationship'. The boy was designated by no more dignified name than 'Tadpole', and his fellows found it 'rather a piquant thing' to 'chevy him about the playground and hit him over the shins with a wicket' — a sentence which suggests that Watson's school, like many others, preserved certain peculiarities of vocabulary, keeping the old term 'play-ground' for 'playing-field' and using 'wicket' in the sense of 'stump'. That it was a 'rugger' school there can be little doubt. How else would Watson have played three-quarter for Blackheath in later years? Characteristically, Watson never alludes to his prowess on the football field, until he is reminded of it by 'big Bob Ferguson', who once 'threw him over the ropes into the crowd at the Old Deer Park'. [7] In class-work we may conclude that Watson was able, rather than brilliant; he was two forms below 'Tadpole' Phelps, though of the same age; his school number was thirty-one. [8] Of Watson's student days we have but scanty record. At St. Bartholomew's Hospital he found himself in an atmosphere that has always been steeped in the tradition of the literary physician, [9] and it is clear that Watson was not of those who are content with the broad highway of the ordinary text-book. The learned and highly specialized monograph of Percy Trevelyan upon certain obscure nervous lesions, though something of a burden to its publishers, had not escaped the eye of the careful Watson; [10] nor was he unfamiliar with the researches of French psychologists. [11] With such interests in the finer points of neurological technique, it may at first sight seem strange that Watson should have chosen the career of an army surgeon, but after what has already been said of Watson's colonial background, it is clear that in the full vigour of early manhood he could not face the humdrum life of the general practitioner. The appeal of a full, pulsing life of action, coupled with the camaraderie of a regimental mess, was irresistible. Accordingly, we find him proceeding to the army surgeon's course at Netley. Whether he played 'rugger' for the United Services is uncertain; his qualification as a 'Club' three-quarter was a high one, but it is probable that at this period his passion for horses was developed. His summer quarters were near Shoscombe in Berkshire, and the turf never lost its attraction for him. Half of his wound pension, as he once, confessed to Holmes, was spent on racing. [12] But the scene was soon to be changed. At the end of his course Watson was duly posted to the Northumberland Fusiliers as Assistant Surgeon. With what zest may we picture him opening his account with Cox & Co. at Charing Cross, [13] and purchasing his tin trunk, pith helmet, and all the equipment necessary for Eastern service; with what quiet satisfaction must he have supervised the painting of the legend JOHN H. WATSON, M.D., upon his tin dispatch-box! But events were moving quickly; before Watson could join his regiment, the Second Afghan War had broken out. It was in the spring of 1880 that Watson embarked, in company with other officers, for service of our Indian dominion. At Bombay he received intelligence that his corps 'had advanced through the passes and was already deep in the enemy's country.' At Kandahar, which had been occupied by the British in July, [14] Watson joined his regiment, but it was not with his own regiment that he was destined to go into action: 'The Fifth marched back to Peshawar, and from there to Lawrencepore; and... in September they received orders for home... So they turned their backs on the tragedy of Maiwand.' [15] To Watson, however, the battle of Maiwand, fought on 27th July, 1880, was to become only too vivid a memory. He was removed from his own brigade and attached to the Berkshires (the 66th Foot), the story of whose heroic resistance at Maiwand has passed into military history. [16] Early in the course of the engagement, but not before he had, without loss of nerve, seen his comrades hacked to pieces, [17] Watson had been struck on the left shoulder by a Jezail bullet. The bone was shattered and the bullet grazed the subclavian artery; but, thanks to his orderly, Murray, to whose courage and devotion Watson pays a marked tribute, he was saved from falling into the hands of 'the murderous Ghazis', and after a pack-horse journey which must have aggravated the pain of the wounded limb, reached the British lines in safety. Of Watson's comrades-in-arms we know little; but seven years later we find his referring to his 'old friend Colonel Hayter' as having come under his professional care in Afghanistan. [18] Hayter is described as 'a fine old soldier who had seen much of the world', and it would seem fairly safe to identify him with the Major Charles Hayter who was director of Kabul Transport in the Second Afghan War. [19] The story of Watson's experiences in the base hospital at Peshawar, of his gradual convalescence, of his severe attack of enteric fever ('that curse', in his own graphic phrasing, 'of our Indian possessions'), of his final discharge, and of his return to England either late in 1880 or early in 1881, may be read in the pages of his own narrative. [20] With no kith or kin in England, with a broken constitution and a pension of 11s. 6d. a day, a man of weaker fibre than John H. Watson might well have sunk into dejection or worse. But Watson quickly realized the dangers of his comfortless and meaningless existence: even the modest hotel in the Strand he found to be beyond his means. Standing one day in the Criterion bar, 'as thin as a lath and as brown as a nut', he was tapped on the shoulder by young Stamford, who had been a dresser under him at Bart.'s. Overjoyed to see a friendly face, Watson immediately carried him off to lunch at the Holborn, where he explained his most pressing need — cheap lodgings. Young Stamford looked 'rather strangely' over his wine-glass. Had he some kind of intuition that he was to be one of the great liaison-officers of literary history, that he was shortly to bring about meeting comparable in its far-reaching influences with hat other meeting arranged by Tom Davies in Russell Street, Covent Garden, more than a hundred years before? Taking Watson with him to the chemical laboratory at St. Bartholomew's, young Stamford fulfilled his mission: 'Dr. Watson, Mr. Sherlock Holmes...' 'How are you?... You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive.' 'How on earth did you know that?...' Such was the initiatory dialogue. Holmes and Watson quickly agreed to share rooms [21], and the load of depression was lifted from Watson's mind. Life had a new interest for him; the element of mystery about his prospective fellow-lodger struck him as 'very piquant'; as he aptly quoted to young Stamford: 'the proper study of mankind is man...' The walls of No. 221B Baker Street [22] bear no commemorative tablet. It is doubtful indeed whether the house has survived the latter-day onslaught of steel and concrete. Yet Baker Street remains for ever permeated with the Watsonian aura. The dim figures of the Baker Street irregulars scuttle through the November gloom, the ghostly hansom drives away, bearing Holmes and Watson on an errand of mystery. For some time Holmes himself remained a mystery to his companion. But on the 4th March, 1881, he revealed him-self as a consulting detective ('probably the only one in the world'), and on the same day there came Inspector Gregson's letter relating to the Lauriston Gardens Mystery. After much hesitation Holmes decided to take up the case. 'Get your hat,' he called to Watson; and though Watson accompanied his friend to the Brixton Road with little enthusiasm, Holmes's brusque summons was in fact a trumpet-call to a new life for Watson. In the course of the adventure which is known to history as A Study in Scarlet, Watson's alertness as a medical man is immediately evident. His deduction of the solubility in water of the famous pill was quick and accurate; nor did he fail to diagnose an aortic aneurism in Jefferson Hope. 'The walls of his chest', he recorded in his graphic way, 'seemed to thrill and quiver as a frail building would do inside when some powerful engine was at work. In the silence of the room I could hear a dull humming and buzzing noise which proceeded from the same source.' At this stage the friendship between Watson and Holmes was only in the making: Holmes still addressed his companion as 'Doctor'. But it was in his first adventure that Watson found his true métier. 'I have all the facts in my journal and the public shall know them.' Between 1881 and 1883 (the year of The Speckled Band) we have little record of Watson's doings. Possibly he divided his time quietly between Baker Street and his club. More probably he spent a portion of this period abroad. His health and spirits were improving; he had no family ties in England; Holmes was at times a trying companion. Now in later years Watson refers to 'an experience of women which extends over many nations and three separate continents.' [23] The three continents are clearly Europe, India, and Australia. In Australia he had been but a boy; in India he can have seen few women except the staff-nurses at Peshawar. It is conceivable, though not likely, that he revisited Australia at this time. It is much more probable that Watson spent some time on the Continent and that, in particular, he visited such resorts as contained the additional attraction of a casino. Gambling was the ruling passion of the Watson family. Watson père had gambled on his luck as an Australian prospector — and won; his elder son gambled on life — and lost; the younger son (a keen racing man' [24] and a dabbler in stocks and shares [25]) no doubt won, and lost, at rouge et noir. By the time of The Speckled Band it is noteworthy that the intimacy between Watson and Holmes has very considerably developed. Watson is no longer 'Doctor' but 'My dear Watson'; Holmes's clients are bidden to speak freely in front of his 'intimate friend and associate'; if there is danger afoot, Watson has but one thought: Can he be of help? 'Your presence', Holmes told him in the case of the Speckled Band, 'might be invaluable."Then', comes the quick reply, 'I shall certainly come.' It is the old campaigner who speaks. The years 1884 and 1885 are again barren of detailed Watsonian record; and here again it is possible that Watson spent part of his time on the Continent. But with the year 1886 we approach one of the major biographical problems of Watson's career — the date of his first marriage. For a proper consideration of the problem it is necessary, first, to clear one's mind of sentiment. We may remember Holmes's own criticism of Watson's first narrative: 'Detection is, or ought to be, an exact science, and should be treated in the same cold and unemotional manner. You have attempted to tinge it with romanticism... The biographer, when he reaches the story of Watson's courtship, must necessarily endeavour to do justice to its idyllic quality, but, primarily, he is concerned with a problem. Let us review our data: (1) In The Sign of Four, Miss Morstan, according to Watson's narrative, used the phrase: 'About six years ago — to be exact, upon the 4th May, 1882...' This would appear to date the adventure between April and June, 1888. (2) A Scandal in Bohemia is specifically dated loth March, 1888, and evidently occurred a considerable time after Watson's marriage. Watson had drifted away from Baker Street, and Holmes had been far afield — in Holland and Odessa. (3) At the time of The Reigate Squires, April, 1887, Holmes and Watson were still together in Baker Street. (4) The adventure of The Five Orange Pips is dated September, 1887, and occurred after Watson's marriage (his wife was visiting her aunt and he had taken the opportunity to occupy his old quarters at Baker Street). A brief summary of this kind does not, of course, pretend to include all the available data, but is at least sufficient to indicate certain contradictions which Holmes himself would have found difficult to reconcile. Suppose, for instance, that we accept the traditional date for Watson's engagement to Miss Morstan — the year 1888. In that case the marriage cannot have taken place until the late summer or autumn of that year. What, then, becomes of the extremely precise dating of A Scandal in Bohemia and The Five Orange Pips? One thing is clear: Watson, careful chronicler as he is, cannot have been consistently accurate in his dates. The traditional assignment of The Sign of Four to the year 1888 rests upon Watson's report of Miss Morstan's conversation; the dates of The Reigate Squires and of The Five Orange Pips are first-hand statements of Watson himself. Now Watson, when he wrote the journal of The Sign of Four, cannot be said to have been writing in his normal, business-like condition. From the moment that Miss Morstan entered the sitting-room of No. 221B Baker Street, he was carried away by what he picturesquely calls 'mere will-o'-the wisps of the imagination'. He tried to read Winwood Reade's Martyrdom of Man, but in vain; his mind ran upon Miss Morstan — 'her smiles, the deep, rich tones of her voice, the strange mystery which overhung her life'. Further, the Beaune he had taken for lunch had, on his own confession, affected him, and he had been brought to a pitch of exasperation by Holmes's extreme deliberation of manner. On the whole, then, was this a state of mind calculated to produce chronological accuracy? On the other hand, there are no such reasons to make us doubt the accuracy of The Reigate Squires and The Five Orange Pips; and if we accept the dates of these, the marriage must be fixed between April and September, 1887. Now, assuming that Miss Morstan shared the common prejudice against the unlucky month, it is not likely that the ceremony took place in May. June, on the other hand, seems extremely probable, since The Naval Treaty (July, 1887) is described as 'immediately succeeding the marriage'. Accordingly, we are driven to conclude that The Sign of Four belongs to the year 1886, in the autumn of which Watson became engaged. In the early part of 1887 Watson would be busy buying a practice, furnishing a house and dealing with a hundred other details. This would explain why, of the v ery large number of cases with which Holmes had to deal in this year, Watson has preserved full accounts of only a few. He had made rough notes, but had no time to elaborate them. 'All these', he writes in a significant phrase, 'I may sketch out at some future date.' Again, if June, 1887 be accepted as the date of the marriage, the opening of A Scandal in Bohemia becomes for the first time intelligible. Between June, 1887 and March, 1888 there was plenty of time for Watson to put on seven pounds in weight as the result of married happiness and for Holmes to attend to separate summonses from Odessa and The Hague. To claim definite certainty for such a solution would be extravagant; but as a working hypothesis it has claims which cannot be lightly dismissed. X

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Left: “Then take the treaty.” Naval Treaty, Sidney Paget, The Strand Oct/Nov-Nov/Dec 1893 Characters: Lord Holdhurst, Percy Phelps

Right: “The view was sordid enough.” Naval Treaty, Sidney Paget, The Strand Oct/Nov-Nov/Dec 1893 Characters: Watson, Holmes

#acd holmes#sherlock holmes#tumblr bracket#sherlock holmes illustrations#polls#R1#oh interesting first one with two from the same story i think#polls full bracket

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Letters from Watson: the Naval Treaty

Part 3: The Fun Bits

Holmes, your Watson is a DOCTOR, it's not a question of if his cases are more interesting, it's a question of people getting medical care on time!

Not that he appears to be seeing a lot of patients at present - I guess the multitude of bacterial and viral illnesses that become more prevalent during the summer - whether they be typhoid or polio - aren't driving a lot of patients his way this year.

Forbes is not a member of the Yard who already likes or appreciates Holmes: when it comes to the credit for the case I wonder if Watson tagging along ever clues the police in that it will (eventually) be a case where the credit does go to Holmes.

(Watson had published only the two novels by 1889 so if the police ever associated his presence with not getting credit, they would not have known to do so now.)

If Lord Holdhurst is modeled after a premier (prime minister) who had actually been in office between 1889 and 1893, our choices are either William Ewart Gladstone (In office 1892-1894) or Robert Gascoyne-Cecil (1886-1892) again. Gascoyne-Cecil's party is listed as conservative, so it's probably him, if anything, though that uh... fucks up our timeline if he's not prime minister YET.

If "Holdhurst" and "Bellinger" (from Second Stain) are both intended to be Gascone-Cecil and Watson's dates in this story are right, his government had TWO document disappearances within the space of about three months. Within six months, if we take fall or very late summer of 1889 to be the date for The Second Stain (Which is contrary to what Watson has said in this story.)

If Holdhurst is intended to be somebody else who is likely to be in the running for prime minister eventually, then Holmes is paying atypical attention to party politics (possibly due to his brother?) and I have no leads on who Holdhurst is an expy for.

The Bertillon system of measurements was a record not only of a convicted criminal's photograph, but head and hand measurements, so they could more easily be identified later. His system's most famous failure would be in the Dreyfus Affair in 1894

Once again, Holmes enlists the help of the only woman connected with the case. And gets the person currently in the most danger away from the scene.

10 notes

·

View notes