#lion symbol of Iran

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A Good Omen

Just the same an ancient persian sword was found in Krasnodar(see in a old post of mine https://ashitakaxsan.tumblr.com/post/698956033583972352/ancient-iranian-sword-unearthed-in-russia )now an other significant discovery opens up to us a perspective,to what worthy events have taken place long ago.

Namely iranian Inscriptions were discovered in a ruined mosque,in a small village in Armenia,that can help trace the history of the Iranian lion symbol back several hundred years,it’s what a member of Iran’s Research Institute of Cultural Heritage and Tourism has said.

It turns out that Armenian inscriptions place the history of the lion symbol in Iranian petroglyphs 600 years earlier than archaeologists originally thought, ISNA quoted Morteza Rezvanfar as saying on Friday.

In one of these Persian inscriptions, a lion is engraved with a sword in hand next to the name of Imam Ali (AS), he added.

According to historical documents, this motif dates back to the time of the Qajar king Fath Ali Shah who reigned from 1797 to 1834, but these newly discovered inscriptions may push that date back over 600 years, he explained.

In addition to the lion and sun symbol, which dates back thousands of years, the first image of a lion holding a sword in inscriptions discovered in Iran, dates back to Qajar-era (1789-1925), and before that, the lion symbol have always had its feet on the ground, he noted.

Iran, also known as Persia, historic region of southwestern Asia that is only roughly coterminous with modern Iran. The term Persia was used for centuries, chiefly in the West, to designate those regions where the Persian language and culture predominated, but it more correctly refers to a region of southern Iran formerly known as Persis, alternatively as Pars or Parsa, modern Fars.

My little say:

The nation of Persia,are the real natives of the land,the Persians are the Ancestores of todays Iranians,their origin has nothing to do with “Indo-European”,because the Indo-European theory is a severe fabrication made by weird Western intellectuals. As the iranian artifact found there this just says:if any nasty entity attempts there to pull something it will find Iran opposing,to any scheme.

Source:https://www.tehrantimes.com/news/484342/Inscriptions-found-in-Armenia-may-push-back-history-of-Iran-s

#Iran#Iranian archaeologists#Iranian petroglyphs#Armenia#Ancient Persia#lion symbol of Iran#Tehran#iranian artifacts in Caucasus#Caucasus#Hayastan#Indoeuropean hoax#Tehrantimes

1 note

·

View note

Note

What did you think of the woman life freedom movement in Iran? (Writing this it's like...what a name, if one says they're against it they are against women life and freedom? Lol) Not sure if it was western from the start or got coopted, I just know I saw a protest in support once by accident in US and people had the flag with the lion so. 🙃

The thing is that they are unorganized, heck there's seldom a leader or political figure to lead these groups. These movements are never structured or organized which is why IRCG keeps cracking down on those protests. The Iranian Revolution was largely successful owing to the Tudeh Marxists, because of their understanding of theory, until ultimately betrayed by the reactionary clerical establishment. Since the revolution up till today, Iran has been a deeply fragmeneted society where people have various ideologies. You got principlists, reformists, marxists, liberals, upper-class elites, pahlavists, anti-VeF Shi'as, MEKs, anarchists, feminists, socdems, opportunists and various other groups that oppose the government, but ultimately lack any theory. For such a reason, these protests turn out to be highly inefficient and counterproductive, since there's like no... strategy other than to remove the Hijab as some form of protest or gesture. That's great and all, but that's not gonna stop the government from cracking down on you, and appealing to the west for some symbolic gesture is not gonna do any good, since they don't give a shit, unless it serves their geopolitical interests and imperialist ambitions.

Learn from previous revolutionary and resistance movements if you wish to succeed.

188 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(38/54) “I could not find it anywhere. The Iran of Shahnameh. The Iran of Cyrus The Great. The Iran of Rumi, Hafez, Saadi, Khayyam. The Iran of our mothers and fathers. The Iran that I had loved since I was a little boy, it was no use to them. They didn’t care about our culture, our history, our ideals. One day Khomeini gave a speech saying that nationalism was against Islam. He said that we should be a nation of Muslims, not a nation of Iranians. The Lion and the Sun were removed from our flag, two of the oldest symbols of Iran. They were replaced by Arabic writing. Our institutions were dismantled one-by-one, until the only things left of the republic and constitution were their names. They became empty boxes that no one knew what was inside. Three months after the revolution I took one final trip to Nahavand. These were the people who trusted me most. Nobody could say that I’d ever wronged them. I wanted to speak with them freely, and share my thoughts. I wanted to see if they grieved along with me. Normally the moment that my car pulled into town, the news would spread like wildfire. People would gather at the house of my father. It had a very large salon, and people would come and go as they pleased. They’d come in excited, passionate, sometimes angry. They’d be critical. They’d debate me. Everyone had something to say. But this time only a small crowd gathered. And I was the only one who spoke. I shared all of my concerns: that we were losing our ideals. We were losing 𝘋𝘢𝘢𝘥. We were losing 𝘕𝘦𝘦𝘬𝘪. We were losing 𝘙𝘢𝘴𝘵𝘪. We were losing 𝘈𝘻𝘢𝘥𝘪. But everyone just listened in silence. They knew my words were true. They knew better than me. But it was fear. They were silenced by fear. There is a famous parable about a caravan of one hundred merchants crossing the desert. Their camels are loaded down with riches. In the night they are overtaken by two bandits, and robbed of everything. Afterwards they are asked: ‘How could it possibly happen? There were one hundred of you, but only two of them.’ They replied: ‘Yes. But those two were together. And we were alone.”

آن را نمییافتم. ایران شاهنامه. ایران کوروش بزرگ. ایران خیام، مولانا، سعدی و حافظ. ایران مادران و پدرانمان. ایرانی که از کودکی دلبستهاش بودم. ارزشی برایشان نداشت. برای آنها فرهنگ، تاریخ و آرمانها بیارج بودند. خمینی گفت ملیگرایی بر خلاف اسلام است. گفت ما باید امت مسلمان باشیم، نه ملت ایران. نشان شیر و خورشید، دو نماد هزاران سالهی فرهنگ ایرانیان را از درفش ایرانزمین برداشتند، جایگزینش واژهای عربی بود. سازمانها و نهادها را فرو پاشاندند. به زودی دریافتیم که جمهوریت و قانون اساسیشان نامی بیش نبود، قالبی میان تهی. سه ماه پس از شورش، سفری به نهاوند داشتم. آنجا زادگاه گرامی من بود، مردمانش، ارجمندانی که دلبستهی هم بودیم. در زمانی کوتاه کارهایی برایشان کرده بودم. خواهان دانستن برخورد و برداشتشان بودم. آیا چون من افسرده و غمگین یا امیدوار، شاد و خشنودند. گفتوگو با آنان بایسته مینمود. پیشتر دیدن خودرو من آژیروار همه را خبر میکرد. در تالار خانه گرد میآمدیم . مردمی پرشور، هیجانزده، شاد، غمزده، آرام یا خشمگین میآمدند و میرفتند. بحث و انتقاد و درخواستهای شخصی و شهری از هرگونه پیش میآمد. رایزنیها برای همه آموزنده و دلنشین بود، امید در هوا موج میزد. ولی این بار تنها شماری اندک آمدند و تنها من بودم که سخن میگفتم. تمام نگرانیهایم را با آنها در میان گذاشتم. اینکه آزادیهایی را هم که داشتیم از دستمان میگیرند. راستی کاسته و کژی افزوده میشود. بیداد، بیداد میکند. دیدم همه خاموشند. دریافتم که همه همآواییم. آنچه زبانشان را بُریده، ترس است. از ترس دم درکشیده بودند. همه رفتند، جز یکی، دوستی که اسب و تفنگی هم داشت. گفت: “در شهر ناکسان در کارند، ناامن است .شب را به خانهی ما بیا، تنها نمان.” نگران من بود. چندان پافشاری کرد تا پذیرفتم. ایران سرزمین آزادگان و جوانمردان است! زبانزد پرآوازهای هست دربارهی کاروانی از سد بازرگان که از بیابان میگذشتند. بر شترهاشان بارهای گرانبها ��یبردند. شباهنگام دو دزد بر آنان شبیخون زدند و همهی داراییشان را دزدیدند. در آبادی از آنها پرسیدند: "چگونه پیش آمد؟ شما سد تن بودید و دزدان تنها دو تن." پاسخ دادند: "زیرا آن دو تن با هم و ما سد تن تنها بودیم!”

183 notes

·

View notes

Text

SHIR ZAN 🦁🗡🔥

my design is inspired by the persian word “shir zan” which means courageous woman (lit. lion woman). i thought this was a fitting representation of the brave women fighting for their rights in iran’s revolution.

the lion woman in my design is breaking the chains that once weighed her down while brandishing a sword, showing her will to fight. the scissors are for all the people who have cut their hair as a symbol of mourning. the fist, combat boot, and molotov cocktail are for resistance against the regime. the paper doll chain on the bottom shows unity between the different types of people in iran. i wanted my design to be a combination of the resistance and unity of iranians who are fighting for a brighter future

purchase mine & 11 other talented artist's scarves here | watch the vid here

all proceeds go to charity

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

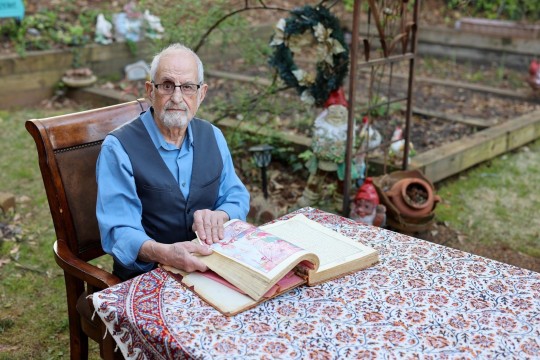

Ketubbah from Isfahan, ca. 1818

Ketubbah from Isfahan, then Persian Empire, now Iran. Made in the year 5578, or 1818 in the Gregorian calendar.

From the Jewish Museum: "Ketubbot (marriage contracts) produced in the Near East are strongly influenced by Islamic art in their lack of figurative decoration. Persia was the most important center of ketubbah illumination in the Islamic world. A popular symbol of Persia, the motif of the lions in front of the rising sun featured on this ketubbah reflects the national pride of the Jews of Isfahan, who believed they were the oldest Jewish community in the country.

Bride: Rivka, daughter of David Groom: Abba, son of Asher Witnesses: Yitzhak son of Yaakov, Yeshu’a son of Shmuel, and Rahamin Binyamin"

#isfahani jews#esfahani jews#iranian jewish#iranian jews#jewish history#swana jews#mizrahi jews#jewish#jewish art#judaism#ketubbah#religious objects

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

would it have been a war crime to shoot this guy?

National "Red Cross" societies were founded after (and directly as a consequence of) the signing of the Geneva Convention. While the internationally recognized symbol is meant to be an inverted Swiss flag, the Ottomans were nonetheless not keen on using a cross as a logo, so their medics wore a "Red Crescent" instead, and this choice of symbol is recognized as equivalent under the Geneva convention.

Iran, who were rivals to the Ottomans, then insisted on using a "Red Lion and Sun", and that was also recognized as equivalent under the convention (although Iran doesn't even use it anymore). Almost immediately, there were a ton of other proposals from various countries to have their own emblems, although these were rejected. At some point, the ICRC decided to solve this once and for all with the "Red Crystal", which any country is free to use if they don't want to use the other recognized symbols. Probably a wise choice.

Anyhow, thank god the "Red Swastika" didn't take off outside of a brief period in the Republic of China.

#chinese#history#???#i guess the answer depends on whether it's a war crime to shoot an unarmed medic who isn't wearing the proper protective symbol

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bronze statue depicting Ashurbanipal... King of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 669-c. to his death in 631 BCE. Known as the "Last Great King" of an empire that, at its time, was the largest on earth. From Cyprus in the west to Iran in the east and, at one point, even included Egypt. The colossal statues guarding the gates to Nineveh, the capitol, held a wriggling lion in their left arm and a serpent in their right hand symbolizing their "mastery" over the animals as well as their mastery over their human subjects. In the case of this depiction of Ashurbanipal, it could symbolize his mastery over conquered territories and internal "vassal kingdoms". The tablet in his left hand has a text that reads: "Peace unto Heaven and Earth/Peace unto Countries and Cities/Peace unto Dwellers in All Lands. The tablet could also symbolize that Ashurbanipal had a library that contained over 30,000 clay cuneiform tablets and fragments that dated from the7th century BCE and included the famous "Epic of Gilgamesh". The statue was commissioned by The Assyrian Foundation for the Arts and was done by Fred Parhad, an Iraqi-Assyrian American (Family refugeed in Iraq due to the Assyrian Genocide of WWI) and was installed at the San Francisco Civic Center in 1988.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

This gold Persian dagger belongs to the Achaemenid Era, c. 550-330 BC. On both sides, representations of a lion and a ram can be seen, symbolizing the Persian empire. The Achaemenid Persian empire stood as the largest in the ancient world, spanning from Anatolia and Egypt across western Asia to northern India and Central Asia. Its origins trace back to 550 B.C., when King Astyages of Media, who held dominion over much of Iran and eastern Anatolia (Turkey), was defeated by his southern neighbor Cyrus II ("the Great"), the king of Persia (r. 559-530 B.C.)

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

you see the old Afghanistan flag a lot, because people don't want to recognize the new leadership, but I've recently been seeing the old Iran flag around, with the retarded lion on it. psychological warfare in the hopes of bringing about regime change I think. I like the current flag, I like the symbol and the intricate design with the colors.

0 notes

Text

The Symbolism and Patterns of Persian Rugs: What Do They Mean?

Persian rugs are celebrated worldwide for their intricate beauty, deep cultural significance, and craftsmanship that have been perfected over centuries. In Woollahra, as in many other parts of the world, Persian rugs are highly sought-after, appreciated not only as decorative pieces but as symbols of rich tradition and storytelling. These rugs go beyond mere aesthetics; they are filled with symbols, patterns, and motifs that carry deep meanings, often representing themes like protection, fertility, and spiritual beliefs. Here’s an exploration of the cultural and symbolic meanings woven into Persian rugs.

The Origins of Persian Rug Patterns

The artistry of Persian rugs has roots that stretch back thousands of years, originating in the ancient Persian Empire. Over time, rug-making evolved into an expressive art form, where each design could tell a story or reflect the values of the artisan’s community. Many of these motifs are influenced by the geography, lifestyle, and cultural heritage of Iran, where Persian rugs originated. Today, Woollahra homes adorned with these pieces bring not just style but a slice of history and cultural richness.

Common Motifs and Their Meanings

Each Persian rug is unique, yet certain motifs appear time and again, each carrying symbolic meaning. Understanding these symbols helps deepen one’s appreciation of Persian rugs, connecting the viewer with the artist’s message.

1. The Tree of LifeOne of the most common motifs, the Tree of Life, represents immortality, spiritual growth, and a pathway between the earthly and divine realms. This motif often appears as a single, branching tree or as multiple interconnected trees on a rug. In Woollahra, where Persian rugs are beloved for their elegance and craftsmanship, the Tree of Life design is especially cherished for its beauty and spiritual resonance.

2. The BotehThe boteh, resembling a teardrop or paisley shape, is another common motif found in Persian rugs. Symbolising growth and fertility, the boteh is often used to bring good fortune and abundance into a home. This motif is thought to represent a combination of a cypress tree and a flame, marrying elements of resilience with spirituality. As Persian rugs become more popular in Woollahra, the boteh design remains a favourite for its hopeful and prosperous symbolism.

3. Animal MotifsAnimals are frequently depicted in Persian rugs, each representing specific traits or ideals. Lions, for example, are symbols of power and courage, while birds are often a representation of freedom or peace. Fish, representing abundance, fertility, and life’s interconnectedness, frequently appear as well. Persian rugs with animal motifs bring a dynamic yet meaningful aesthetic to spaces, especially valued by collectors in Woollahra who seek rugs that tell unique stories.

The Role of Colour in Persian Rugs

Colour is another powerful form of symbolism in Persian rugs. Each hue carries its own meaning, adding further depth to the patterns and designs. Red often represents courage, warmth, and luck, while blue is linked to spirituality and peace. Green, though used sparingly, symbolises paradise and is associated with sacred aspects of Islamic culture. Black is typically employed for outlining, enhancing contrast, and symbolising power or protection. For residents of Woollahra selecting Persian rugs, understanding these colours can help in choosing a rug that aligns with their personal aspirations and home’s ambiance.

Regional Variations in Patterns

Different regions of Iran are known for specific patterns and techniques. The city of Tabriz, for instance, is known for intricate floral patterns and rich detailing, while tribal rugs from the Qashqai or Bakhtiari regions tend to have bolder, more geometric patterns. Kashan rugs are renowned for their medallion layouts and detailed floral designs. In Woollahra, these regional variations add an exciting layer for collectors, as each rug tells a story from a specific place, showcasing unique techniques and styles.

Persian Rugs as Cultural Heritage

Owning a Persian rug means possessing a piece of history and heritage. For many artisans, rug-making is not just a craft; it’s a tradition passed down through generations, a legacy that honours their ancestors. Collectors in Woollahra value these rugs for their artistry and connection to Persian heritage, often viewing them as more than just décor but as cultural artefacts that deserve respect and preservation.

Maintaining and Preserving Persian Rugs

With their cultural significance and intricate designs, Persian rugs deserve proper care to maintain their beauty and meaning. Regular cleaning, avoiding direct sunlight, and rotating the rug periodically help preserve the quality of its fibres and dyes. In Woollahra, professional rug cleaning services are available to help maintain these treasured pieces, ensuring they continue to enhance homes for generations.

Conclusion: A Rich Legacy Underfoot

Persian rugs are more than just floor coverings—they are embodiments of ancient artistry, symbolism, and storytelling. For those in Woollahra, these rugs offer a unique opportunity to connect with Persian culture and enrich their homes with pieces that carry stories of resilience, spirituality, and beauty. Understanding the symbolism and patterns in Persian rugs deepens one’s appreciation, turning these rugs from simple decorative items into meaningful artefacts filled with history and heritage.

0 notes

Text

The 2,500-year-old Huma bird statue in the ancient city of Persepolis, Iran, in the form of a lion-eagle, called the Griffin. In addition, this bird is the symbol of Iranian Airlines. Shiraz, Iran.

#Humabird #Bird #Statue #ancientcity #Persepolis #Lion #animals #Griffin #ancient #history #historical

0 notes

Text

//SIMURGH. The Simurgh, sometimes spelled as «Simorgh» or «Sīmorġ,» is a mythical and legendary bird in Persian mythology and literature. It is often depicted as a majestic, wise, and benevolent creature, and it plays a significant role in the cultural and literary heritage of Persia (modern-day Iran). The Simurgh is typically described as a magnificent and gigantic bird, often with the head of a dog or lion and the feathers of a peacock. Its plumage is said to be resplendent and colorful, representing its divine and transcendent nature. It is seen as a figure of a symbol of divine guidance and enlightenment. The Simurgh is often depicted as the guardian of hidden and sacred knowledge. He is the base of many quests. In some legends, it is said to live for centuries and is capable of rejuvenation by immolating itself in fire. This act of self-sacrifice and rebirth is seen as a symbol of spiritual transformation. It is more han just a physical figure, and is an interesting way, it also portray a «divine knowledge» which is in contradiction with some rational or scientific thinking. A knowledge that can be prooved ; no another one. A bird that has, as the pheonix, the ability of rebirth by fire, in an eternal cycle. The bird is not looking for this knowledge, he is it, as something that flies above our heads but cannot be really seen - or only in a distanced contact. The belive of its exitance push many travelers on a quest - a believe as a base of discovery and self-empowerment. He symbolises also the way people see the knowledge, in the strong believe that we can change through something outside ourslef - the many quests arround this mystical figures shows us that this knowldge often comes from the quest itself, form ourself and the others.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

(42/54) “At dawn we woke to the sound of shots. First the machine gun fire, then the single shots. That morning I counted more than ever before: twenty-one. When the newspaper arrived that morning, I ran my finger down the list until I found his name. It has always been my belief, that if one of us could have survived, it should have been him. He could have united people. His entire life, all his thoughts, all his words, led back to one thing: our common destiny. When you only fight for one lane, one party, one policy, all you see is conflict. Unity is so elusive. There is only one thing we all share: Iran. And nobody knew Iran more, nobody loved Iran more, than Dr. Ameli. We’d later learn his last words were: ‘Do not think of me, think of Iran.’ He was so brilliant. He could have earned all the money in the world. But that’s not where he stored his treasures. He chose to have less, so he could do more. And that is the rarest kind of person. There should be a statue of him in the center of Tehran. But nobody heard the story of his life. Nobody heard the story of his death. It was a seed that didn’t fall into soil. It was too dangerous to even hold a memorial service. We couldn’t grieve. We couldn’t gather together to share our memories. Our only way to honor him was to keep working, to keep resisting in whatever small way we could. We found an empty conference hall, a place so isolated that no one could hear our voices. And we’d hold meetings late at night. We’d bring in singers with beautiful voices, and they’d sing songs. Songs about loving Iran. And as people were leaving we’d hand out cassettes with the speeches of Dr. Ameli. At the very least we could spread his words. On the cover of the cassette we put a picture of his face, next to The Lion and The Sun. They’re two of the oldest symbols of Iran. The sun, the source of all light. And the lion. The lion is the most powerful animal in Iran. It’s loyal. It would do anything for its tribe. And it doesn’t run from anything. The lion is not the largest animal, but its power doesn’t come from its size. It comes from its heart. Its courage. Its soul. Its 𝘕𝘪𝘳𝘰𝘰.”

پنج بامداد با شلیک مسلسل از خواب پریدم. تکتیرها را شمردم. از روزهای پیش بیشتر بود. ۲۱ تیر. همینکه روزنامه رسید، با سرانگشتم لیست نامها را دنبال کردم تا به نام او رسیدم. همیشه بر این باور بودم که اگر از ما دو تن یکی جان به در برد، باید او باشد. او میتوانست مایهی همبستگی مردم باشد. پراکندگان را گرد هم آورد و گُسَستگان را به هم بپیوندد. در درازای زندگیاش همهی اندیشههایش، واژگانش به یک سرچشمه باز میگشتند و آن سرنوشت مشترک ملی بود. سخنانش پرواز می کردند. اتحاد چنان گریزان است که وقتی برای یک خط یا یک حزب یا یک سیاست مبارزه کنی، آنچه میبینی تنها کشمکش است. تنها یک چیز است که ما در آن مشترک هستیم و آن ایران است. و ایران است که ما برایش مبارزه میکنیم. بر آنم کسی بیش از او دربارهی ایران نمیدانست و ایران را دوست نداشت. چندی بعد شنیدیم که واپسین سخنش چنین بوده است: “به من نیندیشید، به ایران بیندیشید.” دکتر عاملی اندیشمندی یگانه بود. میتوانست از پس هر کاری برآید. فرهمند بود. آزمندی از جانش دور بود، گنجینهی جانش آکنده از مهر ایران بود. آگاهانه برگزیده بود کمتر داشته باشد تا بیشتر کار کند، برای ایران. چنین کسانی کمیابند، بلکه نایاب. باید تندیسی از او در دل ایرانشهر ساخت. کس داستان زندگیاش را نشنید. کس داستان مرگاش را نشنید. گویی دانهای بود که در خاک نیفتاده است. مراسم یادبودی هم بر پا نشد. نتوانستیم به یاد او گرد همآییم و غمگُساری کنیم. درد مرا رها نمیکرد. تنها راه دوام آوردن، ادامهی کار بود. پایداری تا توان داریم. تالاری که هیچکس نتواند صدایمان را بشنود، پیدا کردیم. و شبها دیرهنگام گرد هم میآمدیم. میآمدند تا با نوای خوش برای ایران آواز و ترانه بخوانند، سرودهای ملی، مردمی و میهنی. سرودهای دلدادگی به ایران. نوارهای کاست سخنرانیهای دکتر عاملی را میان مردم پخش میکردیم. کمترین کاری که میتوانستیم انجام دهیم، پخش کردن اندیشههایش بود. بر روی جلد نوار کاست، چهرهی تابناکش کنار درفش شیر و خورشید نشان بود؛ دو نماد امیدبخش از روزگاران کهن: خورشید، سرچشمهی نور و روشنایی و شیر، دلیرترین جاندار ایرانزمین. شیرخانواده دوست، شیر گریزناپذیر، نمادی از جان و دل، دلیری و نیرو

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

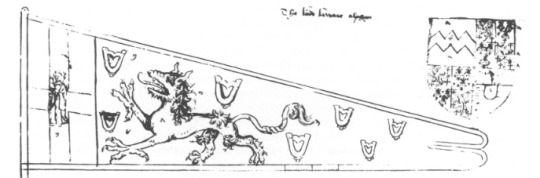

BESTIARIUM: Alphyn

THE ALPHYN IS A RARE LATE FIFTEENTH CENTURY BEAST, appearing on a heraldic badge in the Lords de la Warr, on a gideon held by a knight in the Millefleur tapestry, and briefly in the Book of Standards.

Fig I. A depiction of the Alphyn fom the Book of Standards. The alphyn appears in the centre of the triangular standard with its upper paw ready to strike. Its teeth are bared and the alphyn’s long tongue curls upwards. On the upper right, a heraldic shield is shown.

Alphyns possesses a thick man and tufts of fur, appearing akin to the heraldic tyger. They have long ears, tongues, and a tail—knotted in the middle, much like celtic art. Sometimes the alphyn bears the foreclaws of an eagle, cloven hooves, or the pawed feet of a lion.

Fig II. A depiction of an alphyn with its first front talon raised. The alphyn stares to the front with a scowl with its tongue curved upwards. Similarly, the alphyn’s tail curves in an S shape. From Wikimedia Commons.

To further understand the heraldic alphyn, it is best to look at the heraldic tiger. Unlike the very real tiger, the heraldic tyger is a fanged wolf-like speckled beast said to be from “Hyrcania” in Persia. They have the long tufted main and tail of a lion, with a pointed snout. Tygers are famed for their speed and vanity—one such story stating the following:

“Some report that whose who rob the tyger of her young, use a policy to detainne their damme from the following them by casting sundry looking-glasses in the way, whereat she useth to long gaze, whether it be to behold her own beauty or, because she seeth one of her young ones; and so they escape the swiftness of her pursuit.” Display of Heraldry, Guillim

Hyrcania is not a place in modern Persia, rather being a historical region located south-east of the Caspian Sea in modern-day Iran and Turkmenistan. It was a province of the Median empire. The region was famously associated with tigers in Latin Literature, as cited by this line in the Aeneid:

“Although her back was turned, she still surveyed The speaker blankly and distractedly Over her shoulder, then broke out in fury, “Traitor—there is no goddess in your family, No Dardanus. The sharp-rocked Caucasus Gave birth to you, Hyrcanian tigers nursed you. Why pretend now? Is something worse in store? Was there a sigh for tears of mine? A glance?” Did he give in to tears himself, or pity? Injustice overwhelms me—which concerns Great Juno and our father, Saturn’s son.” Aeneid, trans. Sarah Ruden

Medieval scholars, drawing heavily from Greek and Roman texts, attributed their tyger to Persia—which is not uncommon for medieval sources, knowing their misinformed (and sometimes orientalist) nature. Hyrcania also means “wolf-land”, which is likely why the tyger appears more in line with the heraldic wolf instead of a real tiger.

Hyrcania’s tyger is also used as an insult in the medieval and following renaissance period. In Henry VI Part III, Shakespeare uses the hyrcanian tiger as a symbol of ferocity:

The hungry cannibals would not have touched, Would not have stained with blood: But you are more inhuman, more inexorable, O, ten times more, than tigers of Hyrcania. See, ruthless queen, a hapless father's tears: This cloth thou dip'dst in blood of my sweet boy, And I with tears do wash the blood away. The Third Part of Henry VI, Cambridge University

Considering the Alphyn’s clear likeness to the tyger, we may be able to understand the Alphyn in kinship to the tyger. The eagle and the lion are both representations of noble action and the upper class, so it may be easy to assume that the Alphyn is a noble medieval spirit.

BETWEEN ALPHYAN AND ENFIELD

Almost rarer in heraldic sources than the alphyn, the enfield is an irish heraldic beast originating from the Gaelic onchú “water-dog”. The enfield is described as bearing the head of a fox, chest of a greyhound, front talons of an eagle, the body and hindlegs of a lion, and the tail of a wolf. In this eccentricity, the enfield appears in three contexts:

As the coat of arms of London Borough of Enfield

On the passant sable supporting with the fleur-de-lys on the arms granted to William Marion Mann and his son in June 1964 by the College of Arms in London, along with the heraldic bear as the crest

Armorial bearings of the Irish O’Kelley as the crest upon the helmet, usually in the passant.

It is thought the enfield was the heraldic crest and symbol of the O’Kelley, with a mythological explanation for why the family possessed the enfield symbol:

There is a tradition among the O'Kellys of Hy-Many, that they have borne as their crest an enfield, since the time of this Tadhg Mor, from a belief that this fabulous animal issued from the sea at the battle of Clontarf, to protect the body of O'Kelly from the Danes, till rescued by his followers (O'Donovan 1843, 99).

However, heraldry did not become common or accepted among gaelic families until the Norman conquest—suggesting that the enfield was rather a tribal than heraldic symbol in origin. The onchú is an irish mythical beast connected to water and as such the enfield arose from the sea, connecting the heraldic spirit to the seas:

The onchu, then, is a fierce animal of the dog tribe, on occasion water-dwelling, that sometimes involves itself in human conflicts. It was so often used as a device on the Gaelic battle-standard, that the term onchu actually became applied to the standard itself. It is a priori highly likely that the onchti and the enfield are one and the same. Of Beasts and Banners the Origin of the Heraldic Enfield

The alphyn and the enfield are intertwined from the source, as the alphyn likely arose from the enfield—unlike most heraldic beasts, the alphyn does not appear in any medieval bestiaries. Through Irish officers of arms the alphyn possibly came into English thought, forever connecting the alphyn to the Irish enfield/onchú.

ALPHYN, NOBLE

In my deepest experience, the Alphyn is a very noble beast. My alphyn—for I invited one to dwell within my home—is a very affectionate, noble spirit. With the nobility of the heraldic lion, the alphyn stands out as a medieval beast. My alphyn dwells as an affectionate protector of my home and dear grimoire, standing as a rampart lion would upon a crest.

CONCLUSION

The Alphyn is a rather unique heraldic beast and medieval spirit. From its sudden appearance and connection to the Irish enfield, there is much to explore in terms of working with an alphyn. Whether as the protective lion, a swift tyger-like beast, or an animal ready to strike, the alphyn is a wonderful friend in my witchcraft. Standing firm, the alphyn watches on—ready to strike, whether as rampart or passent.

Alphyn, blood on roses,

Curled in your tuff paw,

Arise, noble alphyn,

Come into my bathe.

Alphyn, gaze upon

Your to mine splendor

Bibliography

Friar, S. (1987). A Dictionary of Heraldry. New York : Harmony Books.

Krisak, L. (2009). The Aeneid. Translated by Sarah Ruden. Pp. 320. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008. Hb. £18.50. Translation and Literature, 18(1), 99–103. https://doi.org/10.3366/e096813610800040x

Shakespeare, W. (2019). The Third Part Of King Henry Vi. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA45317116

Williams, N. J. A. (1989). Of Beasts and Banners the Origin of the Heraldic Enfield. The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, 119, 62–78. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25508971

1 note

·

View note

Text

also representing her with a cicada/scorpion(???) when her traditional symbols are venus, lions, rosettes and doves is. A choice! and i'm not saying this is what happened, but it does feel an awful lot like what would happen if a writer ignorant of the differences between, say, turkey (where the events of the final issues are taking place) or syria/iran (where inanna originated from) and egypt -- who rather famously venerate scarab beetles -- wrote a series about the mystery of an ancient tomb in the middle east.

reading spider-man noir (2020) for the first time and i'm not going to say anything about the optics of turning your depiction of the sumerian goddess inanna, the bi-gendered goddess of love, war and divine justice (feminine as love, masculine as war, but still a woman in body) -- who chased shukaletuda across the stars for revenge after he raped her, whose cult was heavily populated by those who went against traditional gender norms, who was described as "turning men into women"........... into a white nazi. But i sure am going to think it!

2 notes

·

View notes