#like. how often might he have worried about fitting in with other more educated Jews and if he knew enough and did things right and like

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I’m going to say it. I think Moses is going to win the tanakh sexyman bracket.

It’s all fun and games voting for trees and rocks and background characters, but even aside from the picture chosen, I can’t imagine *not* voting for Moses. I don’t care if he’s a sexyman or not. Like. That’s my guy. It’s him! It’s a silly little tumblr poll and I am not very religious at all but he is the main guy. To me. I’m sure all these other stories are just as important rabbinically speaking and in terms of like creating and protecting the Jewish people. But my dad did not read them to me every year at Passover while we all participated in Rituals™️!

And I have to imagine others feel the same way since he’s cleaning up right now with 75% while everyone else’s polls are closer together.

#I also wrote an essay once where I stumbled into realizing a way to relate to Moses as someone raised in an interfaith household#like. he was raised by the Pharaoah! he probably was not brought up perfectly in line with Jewish traditions#and with like a super complete knowledge of his people and culture and religion#like. how often might he have worried about fitting in with other more educated Jews and if he knew enough and did things right and like#then he had to lead everyone??? like! one must imagine a man simply wracked with imposter syndrome#so now I’m like. that’s my buddy Moses.#and exodus and Passover are so foundational to like. my experience of Judaism and my identity. somehow#anyway. Moses sweep. let’s go.#tanakh sexyman#Judaism#mine

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

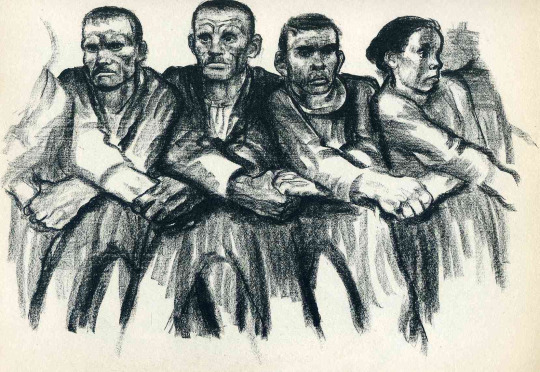

"Mutuality" based on James 2:1-10, 14-17

People often think I am a “bleeding heart liberal,” a “tree-hugging hippie,” or – to get to the point – an “everything goes progressive.” I do not deny the bleeding heart nor the tree-hugging, but actually I don't think “everything goes.” James speaks the language of my faith, and in doing so makes clear why I find it so challenging to live out my faith the way I want to.

Both in Biblical times, and today, the culture is permeated with the premise that deference should be given to wealthy and powerful people. The work of Christians to treat everyone as beloveds of God is profoundly countercultural. James even suggests preferential treatment for the poor, although I can't tell if this is because it is necessary to counteract the brokenness of the world, because most of the early Christians were poor, or because people living in poverty really do have a better grasp on faith. Maybe all of them.

To make his point, James sets up a believable story about two people gathering with the community of believers. One is a rich man, a senator or nobleman based on his ring, likely running for office. This rich man has some powerful quid pro quos to offer the fragile and vulnerable faith community. He could be a useful protector for them.

At the same time, another man enters the community of believers. He is poor, his clothes are old, ratty, and dirty.

The faith community responds with the world's standards, James says. They give the rich and powerful man the best seat in the house while telling the poor man that he can either sit in a place of dishonor or stand out of the way.

James is a wisdom teacher. He speaks clearly through the ages. I can easily believe this was an actual experience in plenty of early Christian gatherings, and I know for certain it still is today. The world's standards infiltrate the church. While Galatians 3:28 says "There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus." That is a RADICAL claim of equity within the Church. All of the distinctions of humanity are erased by being followers of Christ. All are one. All are equal. All are equally important.

But that is easier said that done. The unconscious bias

gets carried into the church, even when people don't want it to. And they do great damage. James says, “Siblings, do you with your acts of favoritism really believe in our Lord Jesus Christ?” I always worry that when we say or hear “Lord Jesus Christ” we hear it with the hierarchy of the English Nobility, a system rife with patriarchy, sexism, and economic exploitation. Which, pretty clearly, isn't what James is saying here. For the early Christians, calling Jesus “Lord” was the utmost subversion, because it claimed that if Jesus was Lord, Caesar was not.1

By ALL of the worldly standards, Caesar WAS Lord. He was Emperor of the largest empire known to that part of the world, he was wealthy beyond imagination, he had the power of the best armies behind him, he had systems of nobility and administration under him, he could execute as he pleased, change laws when he wished, and of course his FACE was on all the money. He had titles galore, including “Lord and God,” and those were the OFFICIAL declarations of the empire, to claim otherwise was to risk death.

In the face of that reality, the early Jesus followers chose another way. A “narrower” way, a more dangerous way, a way that subverted the understanding of power, and choose nonviolence over the power of violence. They claimed Jesus, a peasant from the backwater Galilee, a rabble rouser of the small but ancient Jewish faith, a man executed by the violent power of the Empire as a the leader of a violent rebellion (even when it wasn't true)... they claimed JESUS as Lord.

And when JESUS is Lord like THAT, to favoritism to those who hold power and sway in the Roman Empire could reasonably make James question if they actually believe in Jesus or not. Are they following the narrow way, or are they slowing just making the way wider? Are they about the radical equality of all people in the eyes of God, or about making it easier to be a follower of Jesus? Are they overturning assumptions about who matters, or are they just replicating the ways of the world.

And, of course, the crux of this series of questions: are we?

I can see some evidence that we are committed to inverting the world's values:

Our Community Breakfast is an abundance of good food, offered with grace and respect, that anyone would be pleased to eat. We are not only interested in feeding God's beloveds, we are interested in feeding people AS God's beloveds.

Both the long-running Sustain Ministry Program and Community Breakfast have welcomed and kept volunteers who are also recipients of the ministry's gifts. This suggest to me that we have been interested in re-distributing God's gifts of abundance RATHER THAN just in giving gifts to ease guilt or unconsciously hold power over others.

Our stewardship pledge sheets ask about all of the membership vows: prayers, presence, gifts, service, and witness in order to remind us all that no one way of giving is more important than another, and that all of us are stronger in the ability to give in one way than another.

The church has long advocated for living wages, and puts its money where its mouth is, paying its own employees as it believes the world should.

Before the pandemic, some church groups offered luncheons with (nonobligatory) free will offerings, making genuine space for everyone to be fed and together regardless of income.

Many of the trips we take as a church – hiking, baseball games, canoeing and kayaking trips – are free or affordable to people across a wide income spectrum.

Our community is profoundly diverse, especially in socioeconomic status and income. Beloved members are rich, beloved members are poor, beloved members are in between.

And yet truth be told, I see evidence of the values of the world creeping in too though:

Before the pandemic, often parts of the church celebrated or connected by going out to lunch or dinner, or offering support by sending a communal gift, which assumes that everyone has the discretionary money to participate.

I sometimes hear people living in poverty referred to as “them,” such as in the context, “how can we help them?” which forgets that people living in poverty are part of us. The questions might be, “How can we ease the pain of poverty?” and “How can we transform society to end poverty?”

There is a great value on education in this community, one that isn't always held in enough tension with the reality that in the US access to education has more to do with pre-existant privilege than intelligence.

Our primary worship style speaks to people's heads at least as much as their hearts or souls, which historically fits the values of the upper class.

Among some of our members, there is still a sense of discomfort with the struggles of people in poverty. While discomfort is itself neutral, lack of facing it has resulted in people who live in poverty perceiving that they're welcome to eat at our Breakfast, but not join us for Worship. The perception of a two tiered system, I fear, is not entirely incorrect.

Given these two lists, I think James still has plenty to teach us, even if we've been trying to learn along the way.

In order to build God's Kindom at FUMC, it may mean we have to look deeply at our discomfort. Although discomfort is natural, a willingness to change it is sometimes harder.

To live into the values of Jesus and James requires soaking up God's grace, and a constant awareness of the ways that the world tries to separate people into worthy and unworthy categories. To be a church that lives out the “Lordship of Jesus Christ” requires us to notice class, notice classism, and actively work to change it – in ourselves and in our community. It means that those of us who do not live in poverty need to listen to people who do live in poverty, and learn from them. Our actions to disrupt the status quo and move the world toward the kindom must be based in mutuality. We can't serve in the name of Christ if we see those we serve as “others” rather than as a part of “us.” And we can't claim anyone as part of “us” unless they claim “us” too.

I hope and pray that God will help us take the lessons James offers to heart. Amen

1 Marcus Borg, Jesus: The Life, Teachings, and Relevance of a Religious Revolutionary, (HarperCollins) 2015, p. 279.

September 12, 2021

Rev. Sara E. Baron

First United Methodist Church of Schenectady 603 State St. Schenectady, NY 12305 Pronouns: she/her/hers http://fumcschenectady.org/ https://www.facebook.com/FUMCSchenectady

#Thinking Church#Progressive Christainity#James#Mutuality#umc#Sorry about the UMC#First UMC Schenectady#schenectady#Rev Sara E Baron#Pandemic Preaching#Preferential Treatment of the poor#two men walk into a church#two men actually walk into a proto-church#what does the kindom look like#how are we doing#assessing

0 notes

Link

“Jewish identity in American is inherently paradoxical and contradictory,” said Eric Goldstein, an associate professor of history at Emory University. “What you have is a group that was historically considered, and considered itself, an outsider group, a persecuted minority. In the space of two generations, they’ve become one of the most successful, integrated groups in American society—by many accounts, part of the establishment. And there’s a lot of dissonance between those two positions.”

As pro- and anti-Trump movements jockey to realize their agendas, the question of Jews and whiteness illustrates the high stakes—and dangers—of racialized politics. Jews, who do not fit neatly into American racial categories, challenge both sides’ visions for the country. Over time, Jews have become more integrated into American society—a process scholars sometimes refer to as “becoming white.” It wasn’t the skin color of Ashkenazi Jews of European descent that changed, though; it was their status. Trump’s election has convinced some Jews that they remain in the same position as they have throughout history: perpetually set apart from other groups through their Jewishness, and thus left vulnerable.

From the earliest days of the American republic, Jews were technically considered white, at least in a legal sense. Under the Naturalization Act of 1790, they were considered among the “free white persons” who could become citizens. Later laws limited the number of immigrants from certain countries, restrictions which were in part targeted at Jews. But unlike Asian and African immigrants in the late 19th century, Jews retained a claim to being “Caucasian,” meaning they could win full citizenship status based on their putative race.

Culturally, though, the racial status of Jews was much more ambiguous. Especially during the peak of Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many Jews lived in tightly knit urban communities that were distinctly marked as separate from other American cultures: They spoke Yiddish, they published their own newspapers, they followed their own schedule of holidays and celebrations. Those boundaries were further enforced by widespread anti-Semitism: Jews were often excluded from taking certain jobs, joining certain clubs, or moving into certain neighborhoods. Insofar as “whiteness” represents acceptance in America’s dominant culture, Jews were not yet white.

Over time, though, they assimilated. Just like other white people, they fled to the suburbs. They took advantage of educational opportunities like the G.I. bill. They became middle class. “They thought they were becoming white,” said Lewis Gordon, a professor of philosophy at the University of Connecticut. “Many of them stopped speaking Yiddish. Many of them stopped going to synagogue. Many of them stopped wearing the accoutrements of Jewishness.”

Jews think about questions of race in their own lives with incredible diversity. There are many different kinds of Jews: Orthodox, secular, Reform; Jews by birth, Jews by choice, Jews by conversion. Some Jews who aren’t particularly religious may identify as white, but others may feel that their Jewishness is specifically linked to their ethnic inheritance. “If you’re a secular Jew, how are you a Jew? It has to be through your cultural or ethnic identity,” said Gordon. “Whereas if you’re a religious Jew, you would argue that you’re a Jew primarily through your religious practices.” As Jews assimilated into American culture, “ironically, investment in religiosity paved the way for greater white identification of many Jews,” he said, allowing more religiously observant Jews to think of themselves as white, rather than ethnically Jewish.

Goldstein sees it differently. “‘Whiteness’ and engagement with the categories of ‘white’ and ‘black’ are a reflection of a level of acculturation into a larger society,” he said. The Orthodox are “not just religiously different [from other Jews], but … socially separated,” he added. “They tend to see the world through the lens of their own community.” In other words, their categories for understanding themselves and others might not be “white” and “non-white”; they’re more likely to be “Jewish” and “non-Jewish.”

Other Jews might not think about race much, in the same way that a lot of white folks in America don’t think about race much. Lacey Schwartz, a filmmaker born to a Jewish mother and an African American father, but who long believed she was born to two white parents, experienced this firsthand. “I grew up in a space where we were all white, but it was almost like we didn’t have a race,” she said. These days, she works as an educator in Jewish communities, trying to help people talk about what race and racial diversity mean—topics they haven’t necessarily thought through before. “Within the Jewish community, we have to talk about whiteness, because people have to understand where they fit in,” she said.

Jonathan Greenblatt, the CEO of the Anti-Defamation League, argued that Jews do grapple with race—and in fact, they have been at the forefront of struggles for racial equality like the civil-rights movement. “There’s no doubt that the vast majority of American Jews live with what we would call white privilege,” he said. “They aren’t looked at twice when they walk into a store. They aren’t looked at twice by someone in uniform. … That obviously isn’t a privilege that people of color have the luxury of enjoying.” And yet, even though light-skinned Jews may benefit from being perceived as white, “[Jewish] identity is shaped by these exogenous forces—ostracism, and exile, and other forms of persecution [like] extermination. I think there is this sense of shared struggle … programmed into the DNA of the Jewish people.”

As much variability as there is in how Jews might see their own whiteness, there’s even greater variability in how others see them. “For many Americans, if there’s a secular European Jew walking [down the street], Americans are not going to see the difference between a Polish Jew … and a Polish Catholic,” said Gordon.

For those who do see Jews as a distinctive group, many complicated factors might shape their views. For example: If Jews generally lack racial awareness, as Schwartz contends, that may exacerbate the hostility of the far left. “I think it’s important for Jews to become more aware of their white privilege—[it’s] one of the problems Jews have had in relating to African Americans,” said Goldstein. This has often come up specifically over the issue of Israel: Some Jews have found themselves at odds, for example, with those black activists who describe Israel’s actions toward Palestinians as a form of global white supremacy, interpreting that racialized language as offensive.

There’s also ambiguity in whether non-Jews perceive Jewish distinctiveness in terms of race or religion. “When anti-Semites [talk about] Jews, they mean a racial category,” Gordon argued. “I think they’re looking at Jews the way an anti-black racist looks at a light-skinned black person.” In working with Jewish groups around the country, he said, he has found that religious Jews are much more likely to view anti-Semitism as a form of religious discrimination. But he doesn’t see it that way. “Anti-religion is more like between Protestants and Catholics … or between a Zen Buddhist and Buddhist, or conflicts that Reform Jews have with Orthodox Jews,” Gordon said. “I see anti-Semitism as a racism. I don’t see anti-Semitism as simply about being anti-religion.”

The vast majority of American Jews—94 percent, according to Pew—describe themselves as white in surveys. But many Jews of color—black, Asian, and even Mizrahi Jews—might identify their race in more ambiguous terms. Whiteness isn’t a simple, static category that can be determined by a quick question from a pollster.

So, are Jews white? “There’s really no conclusion except that it’s complicated,” said Goldstein. This is not the kind of question that searches for an answer, though. It’s a question designed to illuminate. It can be difficult to understand why many, although not all, Jews are scared of what’s to come in a Trump administration. Even Goldstein, who studies Judaism and anti-Semitism for a living, said he finds it “hard to believe … that Jews are in any real danger of losing their status in American society. Jews today are integrated into all of the mainstream institutions of American life: They’ve held the presidencies of all the major universities that once restricted their entrance; they are disproportionately represented in all the branches of government.”

youtube

a long listen but if you find the time it’s very very illuminating. if you have the money, pick up this book!! “how jews became white folks and what that says about race in america” by karen brodkin. it’s great insight into history, jews, jewish culture, race, jewish anti-blackness, white supremacy and the role jews play in maintaining and benefiting from white supremacy. and don’t worry, knowing this truth doesn’t make you anti-semitic.

198 notes

·

View notes

Note

I figured this was a fitting question considering your url, haha. What are some misconceptions about Purgatory you hear all the time, and what is it as defined by the Roman Catholic Church?

Let me try this again! This is going to be a long one, sorry not sorry. :P

Let’s get the definitional stuff out of the way. Purgatory is the “final purification of the elect” (CCC 1031), through which the saved are made ready for union with God. Now, this union is made possible through Jesus Christ and His redemptive suffering during the Crucifixion. So why is Purgatory needed? Union with God requires detachment from sin. “All who die in God’s grace and friendship, but still imperfectly purified” (CCC 1030) go through a process of purification to break any attachment we may still have to our individual vices. Purgatory is thus an extension of what we’re supposed to be doing here, which is the detachment from sin so that we may love God as much as we possibly can.

The doctrine of Purgatory was dogmatically defined in 1245, but the concept of the final purification goes back to the early Christian Church. Saint Ambrose of Milan speaks of a purifying fire at the gates of Heaven that all must walk through; his disciple, Saint Augustine, is careful to distinguish between hellfire and the corrective flames of purification. Saint Bede the Venerable actually describes visions of these flames. For those who need Scriptural evidence, Saint Paul seems to have a similar idea in 1 Corinthians 3:10-15 -

According to the grace of God given to me, like a skilled master builder I laid a foundation, and someone else is building on it. Each builder must choose with care how to build on it. For no one can lay any foundation other than the one that has been laid; that foundation is Jesus Christ. Now if anyone builds on the foundation with gold, silver, precious stones, wood, hay, straw— the work of each builder will become visible, for the Day will disclose it, because it will be revealed with fire, and the fire will test what sort of work each has done. If what has been built on the foundation survives, the builder will receive a reward. If the work is burned up, the builder will suffer loss; the builder will be saved, but only as through fire.

I’m about to enter into the realm of speculation here, but the Lord’s Prayer might also allude to Purgatory. The line “lead us not into temptation” may also be translated as “do not subject us to the final test” (as you will see in many modern English translations of Matthew and Luke). In the (very basic) commentary that comes with the standard NABRE translation, this ‘test’ is linked to the trials and persecutions believed to take place right before the coming of the Kingdom, an idea very prevalent in Jewish apocalyptic works. Perhaps it is possible that it might also be asking that we not need to go through the final ‘testing’ of the purification? Maybe this allusion is just in my head, but possibly something to consider.

Of course, the most direct allusion to Purgatory in the Bible is in the Book of Maccabees (which is why I saved it for last; keep in mind that while Protestants reject its Inspired nature, about 61.6% of Christians do accept it as Scripture). In 12:39-46, Judas Maccabeus is described as performing sacrifices to expiate the sins of some of his soldiers. While the author’s purpose of including this story is to prove that Judas believed in the resurrection of the dead (see verses 43-44), it also serves the purpose of showing that it is possible to aid the dead after they have died; if they all went immediately to heaven or hell, this would not be possible. The full text I am referring to reads:

On the following day, since the task had now become urgent, Judas and his companions went to gather up the bodies of the fallen and bury them with their kindred in their ancestral tombs. But under the tunic of each of the dead they found amulets sacred to the idols of Jamnia, which the law forbids the Jews to wear. So it was clear to all that this was why these men had fallen. They all therefore praised the ways of the Lord, the just judge who brings to light the things that are hidden. Turning to supplication, they prayed that the sinful deed might be fully blotted out. The noble Judas exhorted the people to keep themselves free from sin, for they had seen with their own eyes what had happened because of the sin of those who had fallen. He then took up a collection among all his soldiers, amounting to two thousand silver drachmas, which he sent to Jerusalem to provide for an expiatory sacrifice. In doing this he acted in a very excellent and noble way, inasmuch as he had the resurrection in mind; for if he were not expecting the fallen to rise again, it would have been superfluous and foolish to pray for the dead. But if he did this with a view to the splendid reward that awaits those who had gone to rest in godliness, it was a holy and pious thought. Thus he made atonement for the dead that they might be absolved from their sin.

ANYWAY, what are my least favorite misconceptions of Purgatory

Purgatory is Eternal

A few years back, when I was on a bus, two elderly women were talking about DNRs. One of them was disturbed because her brother had signed one. The other woman, in an act that I can only call extremely uncharitable, equated signing a DNR with suicide, and told her that the best her brother could hope for was “eternity in Purgatory.” I was very angry with that; first because while suicide is considered a very serious sin, the Catholic Church currently takes a relatively lenient stance towards it, admitting that many factors can reduce an individual’s personal responsibility for it, while also stating that we should pray for those who commit suicide (CCC 2282-2283). So the “best” one could hope for is not eternity in Purgatory, but eternity in the arms of a merciful and understanding Father.

But besides that, this woman held a deeply flawed understanding of what Purgatory is. Purgatory is not an afterlife, a kind of third option for those who weren’t damned but not good enough for Heaven either. If you are in Purgatory, it is because you are saved. Purgatory is by its very nature transitional, a form of preparation for heaven for those who were not sufficiently prepared at the moment of their deaths. To treat Purgatory as an eternal destination deeply distorts orthodox Christian cosmology, which understands that everything will ultimately have to choose to either be of God or to be of the devil.

People Spend Many Lifetimes in Purgatory

This is actually very common among Catholics, including myself until very recently. If you look at traditional prayer cards that have indulgenced prayers, you’ll often see something like “300 days” written down on the card. People see this, and assume that this means that saying this prayer eliminates 300 days from one’s stay in Purgatory. Which means Purgatory is either virtually empty because people can eliminate their “time” in Purgatory (as if it is some kind of sentence), or Purgatory is some excruciatingly long time in which 300 days is virtually nothing.

Purgatory shouldn’t be seen as this transactional thing. The time one spends in Purgatory is exactly the amount of time it needs for someone to come to terms with themselves and detach themselves completely from their sins. The ‘300 days’ on the prayer card is very much a this-worldly thing; devoutly praying the indulgenced prayer is considered equal to fasting for 300 days. This was a lot more important when Confessors gave penances that could be that extreme. I think the longest penance I have ever received, ever, was spending ten minutes in Eucharistic adoration. I’m not necessarily saying that this shift is a good or bad thing, but it’s a thing that has changed.

So how long does one stay in Purgatory for? However long it takes. We know that we can speed up the process by interceding on their behalf, through prayer and offering up our sufferings and indulgences for their sake, and that’s about it. In Pope Benedict XVI’s Spe Salvi, paragraph 48, he reminds us that “simple terrestrial time” is irrelevant when it comes to the Communion of Saints. As we are all members of the Body of Christ, we are inexplicably connected to one another in eternity, and all our good deeds and all our sins affect everyone else. In paragraph 45, he says that the ‘duration’ of Purgatory is incalculable precisely because it happens outside of that terrestrial time. So don’t worry about it; just pray for your brothers and sisters, knowing that they are effective precisely because our connection to them exists in eternity.Those are my two big ones. I hope this has been at least somewhat educational?

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trump just looked up to the sky and said “I am the chosen one.” A reminder that he’s completely insane, and unfit for office in every way. #25thAmendmentNow

When I heard Trump proclaim himself "The Chosen One" today my first thought was chosen by who, Putin?

Far-Right Dark Money Interests?

Evangelical Christians?

White Supremacists?

Fox News?

Because he defintely wasn't chosen by America...

#25thAmendmentNow

His Ego Bruised by Denmark, Trump Flashes God Complex: ‘I Am the Chosen One’

His dreams of Greenland conquest dashed, Trump re-imagines himself a messiah

By TIM DICKINSON | Published August 21, 2019 3:55 PM ET | RollingStone |

Posted August 22, 2019 12:29 PM ET |

To mangle Twain, it’s better to remain silent and be thought a malignant narcissist than to open your mouth and remove all doubt.

“I am the chosen one,” Donald Trumpdeclared to reporters Wednesday on the White House lawn, looking toward the heavens.

The president was reflecting on his trade war with China, insisting that it should have been launched long ago to curb what he characterized as China’s theft of our wealth and intellectual property. “Somebody had to do it,” Trump insisted.

In another context, one might excuse the quip as mere puffery. But in the case of Trump, the president’s pathological narcissism appears to metastasizing into a messiah complex.

Earlier Wednesday morning the president tweeted out unhinged praise of his Middle East policies from the self-styled “conservative warrior” Wayne Allyn Root. Root, a Newsmax personality, dwells in the fever swamps, promoting birtherism and conspiracy theories around the death of Seth Rich. In the immediate aftermath of the Las Vegas concert shooting he tweeted, without evidence, that the massacre was “clearly coordinated Muslim terror attack.”

In a Twitter thread, Trump quoted Root at length calling the him “the greatest President for the Jews” and even the “King of Israel.”

The president’s gusher of god-complex grandiosity has followed, predictably, in the wake of an ego-damaging exchange with the Prime Minister of Denmark — who laughed off Trump’s unhinged ambition for the United States to buy Greenland from the Scandinavian nation as “absurd.”

Mette Frederiksen, visiting Greenland this week, told reporters that “of course, Greenland is not for sale,” adding that “thankfully the time where you buy and sell other countries and populations and is over. Let’s leave it there.” Frederiksen added that “jokes aside,” Denmark would like a closer relationship with the United States.

Ever thin skinned, especially when it comes to criticism from powerful women, Trump responded petulantly Tuesday night by tweeting that he’d be cancelling a planned meeting with Frederiksen: SEE TWEET ON TRUMP TIME LINE

On Wednesday Trump made clear just how shaken he’d been by the dashing of his dream of Arctic conquest, calling Frederiksen “nasty” — a outburst of misogyny typically reserved for Hillary Clinton. “I thought it was a very not nice way of saying something,” Trump explained to reporters. “All they had to do is say, no, we’d rather not do that or we’d rather not talk about it.”

“She’s not talking to me, she’s talking to the United States of America,” he added, explaining his umbrage. “They can’t say ‘how absurd.’”

Watching Trump these past 24 hours, swinging between grievance and grandiosity, have been like a playing a game of DSM bingo for “narcissistic personality disorder,” the diagnosis of which requires a match of only five of the following nine character traits:

1. Has a grandiose sense of self-importance (e.g., exaggerates achievements and talents, expects to be recognized as superior without commensurate achievements).

2. Is preoccupied with fantasies of unlimited success, power, brilliance, beauty, or ideal love.

3. Believes that he or she is “special” and unique and can only be understood by, or should associate with, other special or high status people (or institutions).

4. Requires excessive admiration.

5. Has a sense of entitlement, i.e., unreasonable expectations of especially favorable treatment or automatic compliance with his or her expectations.

6. Is interpersonally exploitative, i.e., takes advantage of others to achieve his or her own ends.

7. Lacks empathy: is unwilling to recognize or identify with the feelings and needs of others.

8. Is often envious of others or believes that others are envious of him or her.

9. Shows arrogant, haughty behaviors or attitudes.

For more on the president’s dangerous self regard, read my colleague Alex Morris’ ever-timely feature on Trump’s preening and perilous mental health.

Trump’s Mental Health: Is Pathological Narcissism the Key to Trump’s Behavior?

Diagnosing the president was off-limits to experts – until a textbook case entered the White House

By ALEX MORRIS | Published April 5, 2017 12:30 PM ET | RollingStone | Posted August 22, 2019 12:35 PM ET|

At 6:35 a.m. on the morning of March 4th, President Donald Trump did what no U.S. president has ever done: He accused his predecessor of spying on him. He did so over Twitter, providing no evidence and – lest anyone miss the point – doubling down on his accusation in tweets at 6:49, 6:52 and 7:02, the last of which referred to Obama as a “Bad (or sick) guy!” Six weeks into his presidency, these unsubstantiated tweets were just one of many times the sitting president had rashly made claims that were (as we soon learned) categorically untrue, but it was the first time since his inauguration that he had so starkly drawn America’s integrity into the fray. And he had done it not behind closed doors with a swift call to the Department of Justice, but instead over social media in a frenzy of ire and grammatical errors. If one hadn’t been asking the question before, it was hard not to wonder: Is the president mentally ill?

It’s now abundantly clear that Trump’s behavior on the campaign trail was not just a “persona” he used to get elected – that he would not, in fact, turn out to be, as he put it, “the most presidential person ever, other than possibly the great Abe Lincoln, all right?” It took all of 24 hours to show us that the Trump we elected was the Trump we would get when, despite the fact that he was president, that he had won, he spent that first full day in office focused not on the problems facing our country but on the problems facing him: his lackluster inauguration attendance and his inability to win the popular vote.

Since Trump first announced his candidacy, his extreme disagreeableness, his loose relationship with the truth and his trigger-happy attacks on those who threatened his dominance were the worrisome qualities that launched a thousand op-eds calling him “unfit for office,” and led to ubiquitous armchair diagnoses of “crazy.” We had never seen a presidential candidate behave in such a way, and his behavior was so abnormal that one couldn’t help but try to fit it into some sort of rubric that would help us understand. “Crazy” kind of did the trick.

And yet, the one group that could weigh in on Trump’s sanity, or possible lack thereof, was sitting the debate out – for an ostensibly good reason. In 1964, Lyndon B. Johnson had foreshadowed the 2016 presidential election by suggesting his opponent, Barry Goldwater, was too unstable to be in control of the nuclear codes, even running an ad to that effect that remains one of the most controversial in the history of American politics. In a survey for Fact magazine, more than 2,000 psychiatrists weighed in, many of them seeing pathology in Goldwater’s supposed potty-training woes, in his supposed latent homosexuality and in his Cold War paranoia. This was back in the Freudian days of psychiatry, when any odd-duck characteristic was fair game for psychiatric dissection, before the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders cleaned house and gave a clear set of criteria (none of which includes potty training, by the way) for a limited number of possible disorders. Goldwater lost the election, sued Fact and won his suit. The American Psychiatric Association was so embarrassed that

it instituted the so-called Goldwater Rule, stating that it is “un

ethical for a psychiatrist to offer a professional opinion unless he or she has conducted an examination” of the person under question.

All the same, as Trump’s candidacy snowballed, many in the mental-health community, observing what they believed to be clear signs of pathology, bristled at the limitations of the Goldwater guidelines. “It seems to function as a gag rule,” says Claire Pouncey, a psychiatrist who co-authored a paper in The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law, which argued that upholding Goldwater “inhibits potentially valuable educational efforts and psychiatric opinions about potentially dangerous public figures.” Many called on the organizations that traffic in the psychological well-being of Americans – like the American Psychiatric Association, the American Psychological Association, the National Association of Social Workers and the American Psychoanalytic Association – to sound an alarm. “A lot of us were working as hard as we could to try to get organizations to speak out during the campaign,” says Lance Dodes, a psychoanalyst and former professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. “I mean, there was certainly a sense that somebody had to speak up.” But none of the organizations wanted to violate the Goldwater Rule. And anyway, Dodes continues, “Most of the pollsters said he would not be elected. So even though there was a lot of worry, people reassured themselves that nothing would come of this.”

But of course, something did come of it, and so on February 13th, Dodes and 34 other psychiatrists, psychologists and social workers published a letter in The New York Times stating that “Mr. Trump’s speech and actions make him incapable of safely serving as president.” As Dodes tells me, “This is not a policy matter at all. It is continuous behavior that the whole country can see that indicates specific kinds of limitations, or problems in his mind. So to say that those people who are most expert in human psychology can’t comment on it is nonsensical.” In their letter, the mental health experts did not go so far as to proffer a diagnosis, but the affliction that has gotten the most play in the days since is a form of narcissism so extreme that it affects a person’s ability to function: narcissistic personality disorder.

The most current iteration of the DSM classifies narcissistic personality disorder as: “A pervasive pattern of grandiosity (in fantasy or behavior), need for admiration, and lack of empathy, beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts.” A diagnosis would also require five or more of the following traits:

1. Has a grandiose sense of self-importance (e.g., “Nobody builds walls better than me”; “There’s nobody that respects women more than I do”; “There’s nobody who’s done so much for equality as I have”).

2. Is preoccupied with fantasies of unlimited success, power, brilliance, beauty or ideal love (“I alone can fix it”; “It’s very hard for them to attack me on looks, because I’m so good-looking”).

3. Believes that he or she is “special” and unique and can only be understood by, or should associate with, other special or high-status people or institutions (“Part of the beauty of me is that I’m very rich”).

4. Requires excessive admiration (“They said it was the biggest standing ovation since Peyton Manning had won the Super Bowl”).

5. Has a sense of entitlement (“When you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything. Grab them by the pussy”).

6. Is interpersonally exploitative (see above).

7. Lacks empathy, is unwilling to recognize or identify with the feelings

and needs of others (“He’s not a war hero . . . he was captured. I like people that weren’t captured”).

8. Is often envious of others or believes that others are envious of him or her (“I’m the president, and you’re not”).

9. Shows arrogant, haughty behaviors or attitudes (“I could stand in the middle of 5th Avenue and shoot somebody, and I wouldn’t lose any voters”).

NPD was first introduced as a personality disorder by the DSM in 1980 and affects up to six percent of the U.S. population. It is not a mood state but rather an ingrained set of traits, a programming of the brain that is thought to arise in childhood as a result of parenting that either puts a child on a pedestal and superficially inflates the ego or, conversely, withholds approval and requires the child to single-handedly build up his or her own ego to survive. Either way, this impedes the development of a realistic sense of self and instead fosters a “false self,” a grandiose narrative of one’s own importance that needs constant support and affirmation – or “narcissistic supply” – to ward off an otherwise prevailing sense of emptiness. Of all personality disorders, NPD is among the least responsive to treatment for the obvious reason that narcissists typically do not, or cannot, admit that they are flawed.

Trump’s childhood seems to suggest a history of “pedestal” parenting. “You are a king,” Fred

Trump told his middle child, while

also teaching him that the world

was an unforgiving place and that

it was important to “be a killer.” Trump apparently got the message: He reportedly threw rocks

at a neighbor’s baby and bragged

about punching a music teacher in

the face. Other kids from his well-

heeled Queens neighborhood of Jamaica Estates were forbidden from playing with him, and in school

he got detention so often that it

was nicknamed “DT,” for “Donny Trump.” When his father found

his collection of switchblades, he

sent Donald upstate to New York Military Academy, where he could be controlled while also remaining aggressively alpha male. “I think his father would have fit the category [of narcissistic],” says Michael D’Antonio, author of The Truth About Trump. “I think his mother probably would have. And I even think his paternal grandfather did as well. These are very driven, very ambitious people.”

Viewed through the lens of pathology, Trump’s behavior – from military-school reports that he was too competitive to have close friends to his recent impromptu press conference, where he seemed to revel in the hour and a half he spent center stage, spouting paranoia and insults – can be seen as a constant quest for narcissistic supply. Certainly few have gone after fame (a veritable conveyor belt of narcissistic supply) with such single-mindedness as Trump, constantly upping the ante to gain more exposure. Not content with being the heir apparent of his father’s vast outer-borough fortune, he spent his twenties moving the Trump Organization into the spotlight of Manhattan, where his buildings needed to be the biggest, the grandest, the tallest (in the pursuit of which he skipped floors in the numbering to make them seem higher). Not content to inflict the city with a succession of eyesores bearing his name in outsize letters, he had to buy up more Atlantic City casinos than anyone else, as well as a fleet of 727s (which he also slapped with his name) and the world’s third-biggest yacht (despite professing to not like boats). Meanwhile, to make sure that none of this escaped notice, he sometimes pretended to be his own publicist, peppering the press with unsolicited information about his business conquests and his sexual prowess. “The most florid demonstration of [his narcissism] was around the sex scandal that ended his first marriage,” says D’Antonio. “He just did so many things to call more attention to it that it was hard to not recognize that there’s something very strange going on.” (The White House declined to comment for this article.)

Based on the “Big Five” traits that psychologists consider to be the building blocks of personality – extroversion, agreeableness, openness, conscientiousness and neuroticism – the stamp of a narcissist is someone who scores extremely high in extroversion but extremely low in agreeableness. From his business entanglements to his preference for the rally format, Trump’s way of putting himself out in the world is not meant to make friends; it’s meant to assert his dominance. The reported fear and trembling among his White House staff aligns well with his long-standing habit of hiring two people for the same job and letting them battle it out for his favor. His tendency to hire women was spun as a sign of enlightenment on the campaign trail, but those who’ve worked with him sensed that it had more to do with finding women less threatening than men (a reason that’s also been posited as to why Ivanka is his favorite child). Trump has a lengthy record of stiffing his workers and dodging his creditors. And nothing could be more disagreeable than the way he’s dealt with detractors over the years, filing hundreds of frivolous lawsuits, sending scathing letters (like the one he sent to New York Times columnist Gail Collins with her photo covered by the words “The face of a dog!”), and, once it was invented, using Twitter as an instrument of malice that could provide immediate narcissistic supply via comments and retweets. In fact, while studies have found that Twitter and other social-media outlets do not actually foster narcissism, they have turned much of the Internet into a narcissist’s playground, providing immediate gratification for someone who needs a public and instantaneous way to build up their false self.

That Americans weren’t put off by this disagreeableness may have come as a surprise, but in a country that has turned its political process into a glorified celebrity marketing campaign, it probably shouldn’t have. America was founded on the principles of individualism and independence, and studies have shown that the most individualistic nations are, predictably, the most narcissistic. But studies have also shown that America has been getting more narcissistic since the Seventies, which saw the publication of Tom Wolfe’s seminal “Me Decade” article and Christopher Lasch’s The Culture of Narcissism. In 2008, the National Institutes of Health released the most comprehensive study of NPD to date and found that almost one out of 10 Americans in their twenties had displayed behaviors consistent with NPD, versus only one in 30 of those over 65. Another study found narcissistic traits to be rising as quickly as obesity, while yet another showed that almost one-third of high school students in America in 2005 said that they expected to eventually become famous. “If there were no Kardashians, there would be no President Donald Trump,” says Keith Campbell, a professor of psychology at the University of Georgia who co-authored the book The Narcissism Epidemic. “And Trump decided to do it Kardashian-style, with no filter. When Trump and Kanye had that meeting in Trump Tower, I was like, ‘I should just quit. My work here is done.'”

Still, Campbell would not label Trump with NPD. A final DSM criterion for the disease is that it must cause “significant” distress or impairment, which has been a sticking point for many mental-health professionals. “He’s a billionaire who’s president of the United States,” points out Campbell. “He’s functioning pretty highly.”

Others maintain that making diagnoses without a formal interview is not just unethical, but impossible – that the public actions of a public persona may not align with who that person is when they’re alone at home. After Dodes’ op-ed appeared in the Times, Allen Frances, the psychiatrist who wrote the NPD criteria for the DSMIV, followed up with a letter to the editor the very next day, arguing that it was unfair and insulting to the mentally ill to lump them with someone like Trump, and that doing so would give the president a pass he doesn’t deserve. “No one is denying that he is as narcissistic an individual as one is ever likely to encounter,” Frances tells me. “But we tend to equate bad behavior with mental illness, and that makes us less able to deal with the bad behavior on its own terms.”

Others have been less circumspect, implying that if the DSM wouldn’t diagnose someone like Trump with NPD, then maybe it’s the DSM that’s wrong. “It’s just that one pesky impairment thing,” says Josh Miller, Campbell’s colleague and a professor and director of the clinical training program at the University of Georgia who specializes in psychopathy and narcissism. “Maybe the DSM isn’t thinking about this in exactly the right way by ignoring when something causes such widespread problems to those around them.” More specifically, Miller believes that Trump’s wealth could have shielded him from impairment that would otherwise be more pronounced. “He gets to present himself as an incredible businessman despite multiple bankruptcies, despite lots of signs that he is not as astute or as successful as he might be otherwise,” Miller says. “We might know more about his relational functioning if his ex-wives didn’t sign the sort of thing where getting a nice sum of money from a divorce is contingent upon not discussing the person’s behavior. He’s able to keep sycophants around him because of his money. If he was your average politician, it might be that the impairment would be much, much more apparent.”

At the very least, the growing debate over Trump’s mental health raises the question of what having an NPD president would mean. “I hated President Bush, but it never occurred to me or any of my colleagues that he was mentally ill,” says John Gartner, a psychologist who taught in the department of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins University Medical School for 28 years and who has been one of the most vocal critics of upholding the Goldwater Rule in this case, going so far as to say that Trump suffers from “malignant narcissism,” a term for the triumvirate of narcissistic, paranoid and antisocial personality disorders (with a little sadism thrown in for good measure) that was invented to describe what was wrong with Hitler. “Even though I disagree with everything he believes in, I would be immensely relieved to have a President Pence,” Gartner says. “Because he’s conservative. Not crazy.”

Of course, having a mental illness, in and of itself, wouldn’t necessarily make Trump unqualified for the presidency. A 2006 study published in the Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease found that 18 of the first 37 presidents met criteria for having a psychiatric disorder, from depression (24 percent) and anxiety (eight percent) to alcoholism (eight percent) and bipolar disorder (eight percent). Ten of them exhibited symptoms while in office, and one of those 10 was arguably our best president, Abraham Lincoln, who suffered from deep depression (though, considering the death of his son and the state of the nation, who could blame him?).

The problem is that, when it comes to leadership, all pathologies are not created equal. Some, like depression, though debilitating, do not typically lead to psychosis or risky decision-making and are mainly unpleasant only for the person suffering them, as well as perhaps for their close friends and family. Others, like alcoholism, can be more dicey: In 1969, Nixon got so sloshed that he ordered a nuclear attack against North Korea (in anticipation of just such an event, his defense secretary had supposedly warned the military not to act on White House orders without approval from either himself or the secretary of state).

When it comes to presidents, and perhaps all politicians, some level of narcissism is par for the course. Based on a 2013 study of U.S. presidents from Washington to George W. Bush, many of our chief executives with narcissistic traits shared what is called “emergent leadership,” or a keen ability to get elected. They can be charming and charismatic. They dominate. They entertain. They project strength and confidence. They’re good at convincing people, at least initially, that they actually are as awesome as they think they are. (Despite what a narcissist might believe, research shows they are usually no better-looking, more intelligent or talented than the average person – though when they are, their narcissism is better tolerated.) In fact, a narcissist’s brash leadership has been shown to be particularly attractive in times of perceived upheaval, which means that it benefits a narcissist to promote ideas of chaos and to identify a common enemy, or, if need be, create one. “They’re going to want attention, and they’re going to get attention by making big public changes and having bold leadership,” says Campbell. “So if things are going well, a narcissistic leader’s probably not what you want. If things aren’t going well, you’re like, ‘Eh, let’s roll the dice. Let’s get this person out there to just make some big changes and shake things up.’ And then we pray to God it works.”

It doesn’t always. Ironically, for a man who ran on the platform to ”Make America Great Again,” narcissists may have a better chance of getting elected when things are going poorly, but they actually appear to perform better when things are going well – and they can take the credit. One of the questions on the Narcissistic Personality Inventory, which is used to assess narcissistic personality traits, asks respondents to choose between two statements: (1) The thought of ruling the world frightens the hell out of me, and (2) If I ruled the world, it would be a better place. Narcissists obviously tend to pick the latter, but that overconfidence actually works against them: One of the highest predictors of success is conscientiousness, but if you think you’re already the best, then why would you bother to take the time to get better? It’s easier, instead, to point fingers. “Narcissistic people externalize blame,” says Miller. “I mean, Trump’s going to fire [Sean] Spicer, and then it’s going to be the Cabinet. When is he going to say, ‘I should have read that more carefully. I should have taken more time to know what this treaty was’? That is not part of a narcissistic individual’s makeup, to assume responsibility for their own missteps.”

Despite the obvious risks, having a narcissistic president doesn’t always end in disaster. “Democracy’s always based in trying to work through conflict,” says Sean Wilentz, a professor of history at Princeton and contributor to Rolling Stone. “And a person who has a dominant personality sometimes can actually be very effective.” LBJ, who scored the highest in that study that ranked the narcissistic tendencies of U.S. presidents, had the aggressiveness necessary to push through the Civil Rights Act, but he also didn’t (or wouldn’t) do an about-face to get the country out of Vietnam. When a group of reporters pressed him for an explanation of this, he reportedly unzipped his pants, pulled out his penis and declared, “This is why.”

Likewise, Andrew Jackson, who ranked third, was considered the nation’s first demagogue – a rabble-rouser who fought at least a dozen duels throughout his life, who contemporaries thought would trash the White House with his unruly mob, and whose “jackass” tendencies were the inspiration for the symbol of the Democratic Party – but he paid off the national debt and pushed the nation’s expansion westward (though his Indian Removal Act led to the deaths of tens of thousands along the Trail of Tears).

“Narcissistic leaders are really good and bad, meaning that they often get a lot done, but they’re also viewed as ethically challenged,” says Campbell. Meanwhile, “nice guy” presidents like Jimmy Carter are well-liked, but they aren’t viewed as particularly potent.

So how might Trump measure up? According to the 2013 study, while run-of-the-mill narcissism conveyed some benefits, NPD traits usually did not, and were furthermore “related to numerous indicators of negative performance: having impeachment resolutions brought up in Congress, facing impeachment proceedings, placing political success over effective policy, and behaving unethically.” Nixon, probably our most unethical president, was ranked second in the study, but even he knew to conduct attacks covertly. His form of narcissism was more adaptive, more Machiavellian. In fact, many narcissists see the world as a chess game in which they must think ahead in order to maintain the advantage they feel they deserve. For this reason, impulsivity is not considered a classic trait of narcissism. Trump’s obvious rashness, then, allows for an unfortunate combination of traits. “The impulsivity and the lack of deliberate forethought about things,” warns Miller, “paired with the overconfidence, are the most troubling parts for me.”

Another problem for narcissists on the more extreme end of the spectrum is that the skills needed to get elected are not, and have never been, identical to the skills needed to govern. “Just because you get a big job doesn’t mean that you can’t have a psychiatric disability that interferes with your ability to confidently perform it,” points out Gartner. Individuals with NPD are notoriously bad at regulating their behavior or tailoring it to the situation at hand. “Every situation feels like a competition to win,” explains Aaron Pincus, a professor of psychology at Penn State who researches pathological narcissism. “Every situation feels like a stage in which to show people that ‘I’m superior, better, and they’re going to admire me for it.'” As former Democratic Congressman Barney Frank describes his impression of Trump, “I have never seen anybody in public life so focused exclusively on the trivial aspects of his own persona. I certainly have never seen anything like it in a person with a lot of responsibility.”

This makes narcissists particularly vulnerable to sycophants, or at least those who feed their narcissistic supply by telling them what they want to hear. Whether Steve Bannon actually is the evil mastermind he’s been made out to be doesn’t change the fact that even Republicans seem wary of Trump’s susceptibility to him. Unelected officials gaining power through a destabilizing characteristic of a mental disorder is the sort of thing our political system was set up to combat. “It’s a sign, actually, of how severely we need functioning parties,” Wilentz says. “Because when they work, they are in fact a check on the emergence of this kind of character. You can’t get where Trump is now in a functioning party system. It took this particular political crisis, which was a political crisis, to produce a president who has this trait. Normally, we can weed them out.”

For many in the mental-health field, the most troubling aspect of Trump’s personality is his loose grasp of fact and fiction. When narcissism veers into NPD, it can lead to delusions, an alternate reality where the narcissist remains on top despite clear evidence to the contrary. “He’s extremely quick, like nanoseconds quick, to discern anything that could conceivably threaten his dominance,” says biographer Gwenda Blair, who wrote The Trumps: Three Generations of Builders and a President. “He’s on it. Anything that he senses – and he has very sharp senses – that could suggest that he is anything except 200 percent total winner, he’s got to stomp it out immediately. So having those reports, for example, that he did not win the popular vote? He can’t take that in. There has to be another explanation. It has to have been stolen. It has to have been some illegal voters. It can’t be the case that he lost. That’s not thinkable.”

But having verifiable facts be “unthinkable” is, Dodes explains, “a serious impairment of what we call ‘reality

testing,’ so it creates an obvious risk for somebody whose job it is to gather information and

make decisions. It creates an inability to know

where you have gone wrong because you can’t let yourself self-correct by hearing contrary evidence.” This is particularly true when the information is viewed as an ego blow, which goes a long way toward explaining Trump’s first day in office, his blustering assertions of superiority, the speed with which he turns on former allies, and his selection of a wealthy and inexperienced Cabinet – a so-called narcissistic bubble from which anyone or anything that questions his dominance is ejected.

“When it comes to negative information about themselves, narcissists devalue it and they denigrate it and they don’t accept it,” says Pincus. “They’ll push it away, they’ll distort it, they’ll blame it on somebody else, they’ll lie about it, because they need to see that superior, ideal image of themselves, and they can’t tolerate the idea that they have any flaws or imperfections or somebody else might be better than them at something.” This not only means that Trump has no qualms about lying (a PolitiFact tally of candidates’ statements during the 2016 campaign found that only 2.5 percent of the claims made by Trump were wholly true and that 78 percent were mostly false, false or “pants on fire”), but it also means that he will continue to cater to his minority base, which, Pincus continues, “happen to have his ear and tell him he’s great. Then he’s shocked when courts and states have a different opinion, and he has to denigrate the courts and the states rather than question his own position.” It means that he will continually recast negative events in his favor: “All four corporate bankruptcies, were they a sign of failure for him during the debates?” asks Blair. “No, they were a sign he was smart.” And he will continue to double-down on delusions, like having been wiretapped by Obama, despite all evidence to the contrary.

That’s what concerns Wilentz. “We’ve had some very troubled presidents in our past, but their troubles are things like alcoholism, paranoia, you know, sort of garden-variety psychological maladies,” he tells me. “This is different. This shows a dissociation from reality. We just haven’t seen anything like this before.” Gartner’s take is even more pointed: “He’s acting crazy, and he’s mad that other people aren’t seeing and believing what he’s making up in his own head.”

This dissociation from reality, paired with Trump’s knee-jerk need to assert his dominance, has led many mental-health professionals to feel that, no matter what the specific diagnosis, the traits themselves are enough to render Trump unfit for office, and that a shrink’s “duty to warn” overrides the Goldwater Rule in this instance. “Psychiatrically, this is the worst-case scenario,” says Gartner. “If Trump were one step sicker, no one would listen to him. If he were wearing a tinfoil hat, if he were that grotesquely ill, he wouldn’t be a threat. But instead, he’s the most severe and toxic form of mental illness that can actually still function. I mean, in his first week in office, he threatened to invade Mexico, Iran and Chicago. And thank God someone finally stood up to Australia, you know? Glad someone had the balls to put them in their place.”

Indeed, it was Gartner’s fear that “Trump is truly someone who can start a war over Twitter” that led him to start a petition on January 26th that called on mental-health professionals to “Declare Trump Is Mentally Ill and Must Be Removed,” invoking Section 4 of the 25th Amendment to the Constitution, which states that the president should be replaced if he is “unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office.” Gartner’s petition currently has 40,947 signatures. Congresswoman Karen Bass’ petition, #DiagnoseTrump, has 36,743.

Not that any of these petitions are likely to make a difference. In order for Section 4 to be invoked, Congress or the vice president along with a majority of Trump’s handpicked Cabinet would have to call for his removal, which has never happened under any presidency. And even if Trump did something that warranted impeachment, 25 Republicans in the House would have to break ranks to pass the resolution on to the Senate, where two-thirds of that body would have to condemn him, meaning that no fewer than 19 Senate Republicans would need to vote in favor of an ouster. Many of those Republicans come from districts where #MAGA is practically gospel, meaning that these numbers are not just daunting, they’re all but unthinkable.

On June 29th, 1999, Trump gave a eulogy at his father’s funeral at Marble Collegiate Church in Manhattan. Others spoke of their memories of Fred Trump and his legacy as a man who had built solid, middle-class homes for thousands of New Yorkers. But his middle son, according to most accounts, used the time to talk about his own accomplishments and to make it clear that, in his mind, his father’s best achievement was producing him, Donald.

Presidents unite nations under narratives of what they stand for, whether true or false. But a president with NPD would stand for nothing but himself, offering no narrative other than the “false self” he created. An NPD president would expect Americans to go along with his rhetoric and ignore that behind the self-aggrandizing, the unyielding drive for more and more confirmation of the myth of his own greatness, he may only have his own emptiness to offer. “‘We’re going to do this thing, it’s going to be fantastic, amazing,'” Pincus paraphrases. “But there’s no substance to what he says. How are you going to do that? How is that going to be achieved?”

The answer is we don’t know. The White House leaks portray an angry man who wanted to become president, but never really wanted to be president. Trump may have stormed into the Oval Office poised to make sweeping changes, but unlike LBJ or Jackson or even Nixon, he doesn’t have the political expertise or historical perspective to see the long game. The rumblings in Congress suggest widespread fears that Trump will view policy through the prism of pathology rather than in any rational, methodological, bipartisan way. So far, as Barney Frank points out, even with a Republican House and Senate, “Trump hasn’t done very much.” His immigration bans have been blocked, his budget has been ridiculed, and his rage against the GOP to repeal and replace Obamacare, or else (and with a plan that would take health care away from millions of Americans while making it more expensive for most of the rest of us), turned into nothing more than a game of chicken – which he lost – with House Republicans. “Trump’s time horizon with regard to things that affect him appears to be about 13 minutes,” Frank says. “There is an inverse relationship between people who are more focused on how things affect them personally than on public policy and their effectiveness in Congress. You can’t work with those people.”

If Trump does have NPD, and the setbacks to his agenda keep coming, his magical thinking about the limitlessness of his power will only continue to clash with reality, and many in the mental-health field believe that would only exacerbate the problem. “I think we’re actually looking at a deteriorating situation,” says Gartner. “I think he’s going more crazy.” As Dodes’ letter to The New York Times states, Trump’s attacks against “facts and those who convey them … are likely to increase, as his personal myth of greatness appears to be confirmed.” Still, no matter how monumentally he fails in the next four years, says biographer Gwenda Blair, “there’s no doubt he’s going to think he’s done a great job. That isn’t even open to question.”

#trump administration#trump news#trumpism#president donald trump#trump scandals#trump#donald trump#maga#us politics#politics#u.s. presidential elections#u.s. news#u.s. foreign policy#u. s. foreign policy#news#trending news#mental health#potus45#potustrump#impeachthemf#impeachtrump#impeachment inquiry now#impeach trump

0 notes

Text

#I also wrote an essay once where I stumbled into realizing a way to relate to Moses as someone raised in an interfaith household#like. he was raised by the Pharaoah! he probably was not brought up perfectly in line with Jewish traditions#and with like a super complete knowledge of his people and culture and religion#like. how often might he have worried about fitting in with other more educated Jews and if he knew enough and did things right and like#then he had to lead everyone??? like! one must imagine a man simply wracked with imposter syndrome#so now I’m like. that’s my buddy Moses.#and exodus and Passover are so foundational to like. my experience of Judaism and my identity. somehow

I’m going to say it. I think Moses is going to win the tanakh sexyman bracket.

It’s all fun and games voting for trees and rocks and background characters, but even aside from the picture chosen, I can’t imagine *not* voting for Moses. I don’t care if he’s a sexyman or not. Like. That’s my guy. It’s him! It’s a silly little tumblr poll and I am not very religious at all but he is the main guy. To me. I’m sure all these other stories are just as important rabbinically speaking and in terms of like creating and protecting the Jewish people. But my dad did not read them to me every year at Passover while we all participated in Rituals™️!

And I have to imagine others feel the same way since he’s cleaning up right now with 75% while everyone else’s polls are closer together.

#oh shit those ARE some really good tags!#untagged#one of these days I'm gonna be brave enough to tag my posts about judaism#(i don't feel like i can right now though since i'm not a convert or anything)#(i'm just... compelled)

193 notes

·

View notes