#like colonialism in the philippines and assimilation/diaspora

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Adult essay collection

Covers topics such as sex, power, the model minority myth, assimilation, and Filipino history

Funny and insightful

Gay, Filipino author

#this was quite good!#i think the author really excels at taking aspects of his personal life and connecting them to broader topics#like colonialism in the philippines and assimilation/diaspora#i tend to breeze through memoirs but this was best read with breaks between the essays i think#just to give myself time to really absorb each essay and think it over#2023 reads#the groom will keep his name#matt ortile#lulu reads the groom will keep his name#books#lulu reads#lulu speaks#burlesque rom com#<- just putting it in the tag for that writing project#because i read it partially as research for that wip

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The portrayal of the precolonial and early colonial women babaylan as oppositional to patriarchal colonization configured them as protofeminists... Mangahas claims that whereas the women babaylan were annihilated, assimilated, or compromised by the colonial order, the power of Philippine women was not fully lost... Many present-day women professionals, mostly from urban and/or diasporic middle-class backgrounds, have been attracted to the image of the babaylan and have ascribed the babaylan title to themselves... These developments have inspired many in the face of ongoing violence and discrimination against women, immigrants, and other minorities, in domestic and work places, in the homeland and in the diaspora. Scholars like Zeus Salazar, however, observe the alienation between what he calls the "babaylan of the elite and the babaylan of the real Filipino [who] still sit with their backs against each other." Salazar warns that the "Babaylan tradition could be co-opted by new-age type spirtuality-seeking affluent, middle class Filipinas whose end goal is individual spiritual enlightenment. ...Not a few have pointed out the problem of extracting the babaylan title as though it were a commodity to be acquired without first going through Indigenous channels and protocols... To abstract the title from the process and relationships just because one is attracted to images of Indigenous women that converge with feminist models or because one has the privilege to do so is facile and demonstrates a lack of respect for Native ritual specialists and their communities.

- Babaylan Sing Back by Grace Nono

#philippines#indigenous#precolonial#postcolonial#history#yes yes yes finally someone said it#early on in my precolonial philippine research#i kept coming across these websites and articles about how we should embody our inner babaylan#and it felt so strange that most of the writers of these pieces were diasporic and actually had no babaylan training#it just felt so... exploitative to me#i'm so glad to hear that scholars have been criticizing this movement all along

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

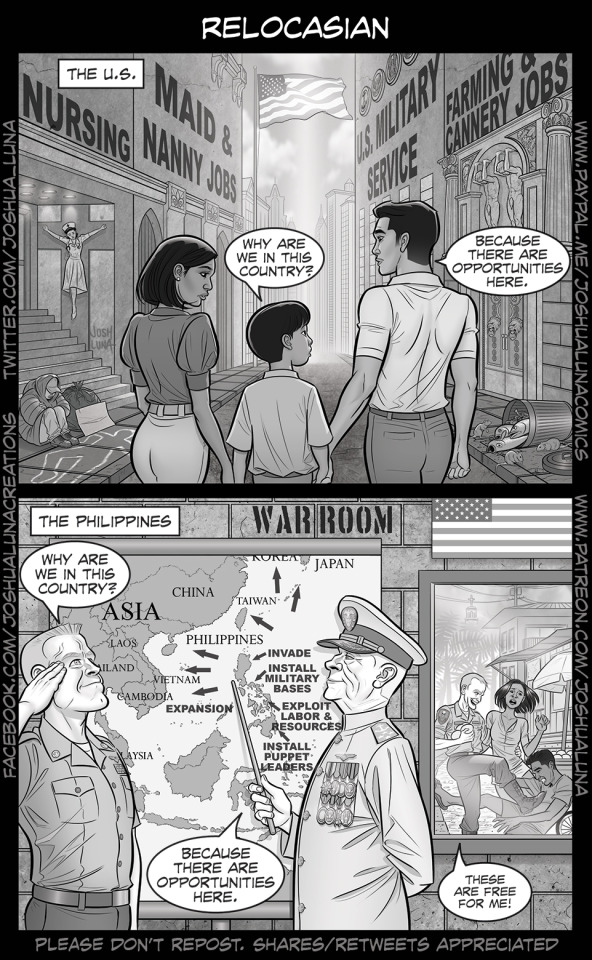

For Fil-Ams and other people of color, the "American Dream" often means toiling away just to obtain a small piece of the spoils that were violently ripped away from your community.

Second-gen Asian Americans like me grow up oblivious about our own histories because the U.S. education system purposely withholds information about it, and our parents try to outrun their trauma by never sharing their experiences, instead pushing their children toward an assimilation sleepwalk.

AsAms realize too late we've inherited a deal with the devil we never agreed to: we can keep our language, but only if we speak it privately. Our food, if we serve it. Our culture, if it upholds the illusion of America as a benevolent melting pot that saved us from ourselves.

But AsAms aren't the only ones ignorant of this history. Few Americans know of the Philippine-American War and the atrocities the US committed. Even fewer understand how the U.S.’s ongoing legacy of war, destruction, and colonization in Asia is a major reason the AsAm diaspora exists.

Americans aren't taught about how centuries of exploitation of the Philippines' resources by Western powers has led to most of its workforce immigrating and becoming a global servant class called Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs). Instead, they're taught that poverty is inherent to Filipinx culture.

Americans aren't taught about how the US installs and props up puppet leaders and dictators—like how Nixon, Ford, Carter, and Reagan fully backed Marcos as he ruled under martial law and committed human rights violations. Instead, they're taught corruption is inherent to Filipinx culture.

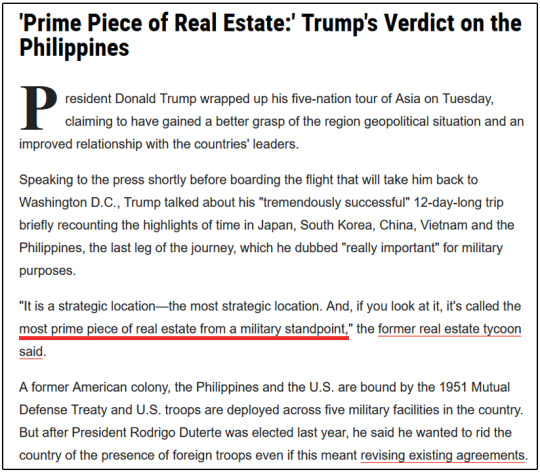

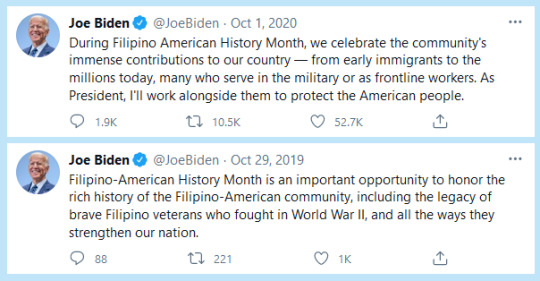

Americans aren't taught that colonization is bipartisan and Trump and Biden agree on their view of the Philippines: a de facto colony whose resources and bodies can be exploited with impunity for the US war machine. Instead, they're taught servitude is inherent to Filipinx culture.

Americans aren't taught about one-sided US military agreements used to keep an imperialist foothold: the Mutual Defense Treaty, Mutual Logistics Support Agreement, Visiting Forces Agreement & Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement. Instead, they're told it's for mutual benefit.

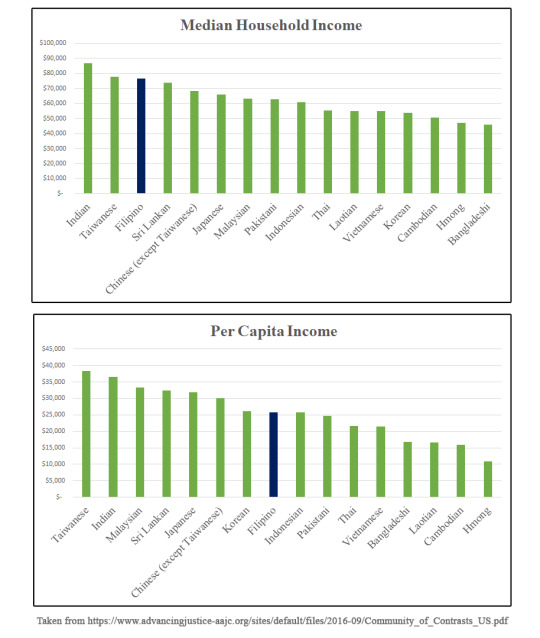

American's aren't taught about how many AsAms struggle with poverty, institutional racism, and violence. Instead, they're taught the Model Minority Myth—created by white people and propagated by all races—that says Asians don't suffer race-based oppression.

Americans aren't taught about how Fil-Ams give earnings to family, live in multi-generational households to pool money together, and how the Philippines' economy would collapse without OFW remittances. Instead, they're taught Fil-Ams have a high median household income amongst AsAms.

Americans aren't taught about how AsAm leaders are installed with white backing the same way puppet leaders are, and use their shared race to hurt their own and prevent true progress. Instead, they're taught that privileged, out-of-touch blue-checks are the voice of our community.

So if Americans aren't taught any of this, who will teach them? The ugly truth is that AsAms who try to speak up are often crushed into silence by non-Asians who benefit from the status quo, and by Asian puppet leaders who've been installed to protect their masters' interests.

Overall, being Filipinx and Asian means constantly navigating survival between rotating oppressors.

As an ex-Navy brat who grew up overseas, I've struggled with my concept of home and at one point believed "home" was a US military base. But maybe that's as Fil-Am as it gets.

(Please don’t repost or edit my art. Reblogs are always appreciated.)

If you enjoy my comics, please pledge to my Patreon or donate to my Paypal. I lost my publisher for trying to publish these strips, so your support keeps me going until I can find a new publisher/lit agent

https://twitter.com/Joshua_Luna/status/1134522555744866304 https://patreon.com/joshualuna https://www.paypal.com/paypalme2/JoshuaLunaComics

#filipinx#fil-am#filipino#filipina#pinoy#pinay#diaspora#asian american diaspora#asian american#immigration#colonization#us military bases#us military#exploitation#racial trauma#ofws#overseas filipino workers#president biden#trump#artists on tumblr#my art#filipino artist#fil-am artist#comic#josh luna#joshua luna

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

FilAms referring to the Philippines as the acronym PI while they are calling homelanders for the use of Filipinx and Pinxy is peak irony. That is without adding these two facts: the letter F is a loaned letter in Tagalog from the oppressors (and its corresponding phoneme too) and that the demonym is an appellation to Felipe II of Spain. And for someone like me who reads and writes in Baybayin since age 15, to write a Baybayin X seems like a dark humor scene in a Taika Waititi comedy. (Yes, I do Baybayin shiz for fun, but not as serious as Kristian Kabuay and NordenX.)

I first encountered PI among FilAms during Christmas vacation 2002 in LA; and Pilipinx when I joined the theatrical production of a FilAm musical at CalState East Bay in 2016. I understand that it is their culture and I respect it, and I assimilate. I easily assimilate with what I call my Nickelodeon voice, which I have acquired from when jailbroken cable services became a thing in Mega Manila and through my theatre background. But when in Rome, we live the Roman way, so as the Santa Mesa-born foreigner, I have to hide that dark laughter every single time someone uses PI.

But of course, 2020 had to make us see PI-using FilAms pressuring homelander to use Filipinx, citing political correctness and gender neutrality (while white American Pemberton, the killer of Filipino transwoman Jennifer Laude, was given an absolute pardon by Duterte).

So, let us start my TEDtalk.

P.I. is a colloquial acronym for Putanginamo (the equivalent of Fuck You) used by conservative Filipinos who probably are only retelling a story.

Tsismosa 1: “Minura ni Aling Biring si Ka Boying.” (Aling Biring cursed Ka Boying)

Tsismosa 2: “Oh? Ano ika?” (Really? What did she say?)

Tsismosa 1: “Malutong at umaatikabong PI.” (A hard and surging PI.)

Then I imagine PI as the curse when FilAms say some sentences:

“Are you flying back to Putangina?”

“I miss Putangina. We went to Boracay.”

“Duterte is President of Putangina.”

But it’s fine with me. I understand they mean well and I know that Americans, as first world as they are, have poor grasp of history. It’s a little sad though that FilAms have not always been reminded of this special footnote in the history of the United States:

P.I. stands for Philippine Islands. That’s the colonial name of the Philippines as a commonwealth republic under the United States, which the republic stopped using when the 1935 Constitution was enacted in 1946. Yes, in case people are forgetting, the Philippines has long been a state with full sovereignty recognized by the United Nations (of which we are a founding member of and wherein Carlos Romulo served as President) and recognized by Shaider Pulis Pangkalawakan.

Also, RP is used to refer to the Republic of the Philippines before the use of the standard two-letter country code PH.

I’m not saying FilAms should stop using PI to refer to the Philippines but I’m saying that the roots of that practice is from American oppression that homelanders have already cancelledttt.

Our oldest bank in the Philippines is BPI. It stands for Bank of the Philippine Islands, originally named El Banco Español Filipino de Isabel II because it was founded during Queen Isabella II’s reign. It was a public bank by then; perhaps comparable to the Federal Reserve. Upon its privatization during the American occupation, the bank started using BPI for the sake of branding because it was the Americans who christened us with P.I. (I have a theory that Manila was a character in Money Heist because the Royal Mint of Spain used to have a branch in the Philippines and operated very closely with BPI. And my other supernatural theory is that our translation of peso which is ‘piso’ affects our economy. ‘Piso’ means ‘floor’ or ‘flat’ in Spanish.)

Now, going back. To me, P.I. is more appropriate an acronym for the ethnic group of Pacific Islanders. I don't think I need to explain further why. These would be the natives of Hawai’i, Guam, Tuvalu, Kiribati, and other islands in the Oceania continent, and maybe even New Zealand. If a curious FilAm raises a question of whether Filipinos are Pacific Islanders or Asians or Hispanics, the answer is long but easy to understand.

The Filipinos live in a group of islands within the Pacific Plate. The Philippines is an Asian country, following conventions of geopolitical continental borders from the other. We are Hispanics by virtue of being under Spain for three fucking centuries. And Teresita Marquez is Reina Hispanoamericana because why not? (We could’ve been a part of America still if not for the efforts of Quezon.) So, the quick answer is that the Filipino is all of it.

Yes, the Filipinos have an affinity with the Pacific through nature and geography. Think of the earthquakes, volcanoes, flora and fauna, and the coconuts. And they even look like us. The earlier inhabitants of the archipelago were Pacific Islanders who were introduced to Hinduism and Buddhism as being closer to the cradles of civilization India and China. Then, the Islamic faith has grown along with the rise of the kingdoms and polities in Southeast Asia. The Spaniards arrived in the archipelago, to an already civilized Islamic polity - too civilized that they understood how diplomacy is necessary in war. We knew that it resulted to the defeat and death of Magellan who was fighting for Rajah ‘Don Carlos’ Humabon. Then came the 333 years of being under Spain AND (sic) the Catholic Church which made us more Hispanic. Our Austronesian/Malayo-Polynesian languages (Tagalog, Bisaya, Kapampangan, Ilocano, Bikol, Waray, Cuyonon, etc.) have kept our Asian identity intact - unlike Latin American countries where the official language of each is one of the Romance languages; thus "Latin".

(It is only towards the end of that 333-year Spanish rule that the 'Filipino' emerged to be something the oppressed could claim, and for that we thank the poet in Jose Rizal. I see a parallel in how Christians claimed the cross, the former symbol of criminals in Jewish tradition, to become the symbol of God’s love and salvation through Jesus. Wow. That’s so UST of me. Lol.)

You add into the mix that our diaspora is so large and identifiable, the data gatherers decided to mark the tables with “Filipino” - too Asian to be Hispanic and Pacific, too Pacific to be Hispanic and Asian, and too Hispanic to be Asian and Pacific.

What many FilAms do not realize everyday is that unlike the words Blacks, Latinx, Asians, or Pacific Islanders, or Hispanics, the word Filipino is not just a word denoting an ethnic group. At its highest technical form, the word Filipino is a word for the citizenship of a sovereign nation, enshrined in the constitution of a free people whose history hinges on the first constitutional republic in Asia.

By state, we mean a sovereign nation and not a federal state. (Well, even with Chinese intervention, at the very least we try.)

By state, we mean we are a people with a national territory, a government, and a legal system inspired by the traditions of our ancestors and oppressors. It may be ugly, but it is ours, and we have the power to change it.

This one may be as confusing as Greek-Grecian-Greco-Hellenic-Hellene, but let’s examine the word 'Filipino' further when placed side by side with related words.

*Pilipinas is the country; official name: Republika ng Pilipinas. It is translated into English as “Philippines”; official name: Republic of the Philippines. Spanish translates it into “Filipinas”, the Germans “Philippinen”, the French “Les Philippines”, the Italians “Filippine”.

*Pilipino refers to the people. It is translated into English as Filipino. The plural forms are ‘mga Pilipino’ and ‘Filipinos’.

*Philippine is an English adjective relating to the Philippines, commonly used for official functions. It may be used as an alternative to the other western adjective ‘Filipino’ but the interchangeability is very, very nuanced. Filipino people not Philippine people. Filipino government and Philippine government. Philippine Embassy, Filipino embassy, not Filipino Embassy. Tricky, eh?

*Filipino also refers to the official language of the state (which is basically Tagalog).

*Filipiniana refers to Philippine-related books and non-book materials (cultural items, games, fashion, etc.) which could be produced by Filipinos or non-Filipinos, inside or outside the Philippines.

*Pinoy is a colloquial gender-neutral demonym; comparable to how New Zealanders use the word Kiwi.

The demonym Filipino has evolved from that of referring only to Spaniards in the Philippines into becoming the term for the native people who choose to embrace the identity of a national.

It started from when Jose Rizal wrote his poem “A la juventud filipina” and he emerged as an inspiration to the Philippine Revolution through Andres Bonifacio’s leadership. (But take note of ‘filipina’ because ‘juventud’ is a feminine word in Spanish.)

Today, no less than the 1987 Philippine Constitution, which was neither written by Hamilton nor a group of straight white men but by people of different faiths, genders, disabilities, and skin colors, in its first five words in both Filipino and English versions read: "Kami, ang nakapangyayaring sambayanang Pilipino", translated as "We, the sovereign Filipino people” validates the legitimacy of the word as gender-neutral, alive, aware and awake with our history of struggles.

Article 14 Section 7 of the current Constitution says Filipino is the national language. And while I agree that it is not really a real language but an alias for Tagalog, it is a conscientious codification of a social norm during the time of Manuel Quezon as he is aiming for the world to recognize the unified Filipinos as a sovereign people. People. Not men. Not heterosexual men. People.

It is a non-issue for the homeland Filipino that the word Filipino refers to the people and the language. But FilAms are concerned of political correctness due to an understandable cultural insecurity also felt by other non-whites in the US. And there is added confusion when FilAms pattern the word Filipino after the patriarchal Spanish language, without learning that the core of the grammars of Philippine languages are gender-neutral. The Tagalog pronoun "siya" has no gender. "Aba Ginoong Maria" is proof that the Tagalog word 'ginoo' originally has no gender. Our language is so high-context that we have a fundamental preposition: “sa”.

It is difficult to be a person of color in the United States especially in these times of the white supremacy’s galling resurgence. Well, it’s not like they have been gone, but this time, with Trump, especially, it’s like the movement took steroids and was given an advertising budget. But for FilAms to force Filipinx into the Philippines, among homeland Filipinos, is a rather uneducated move, insensitive of the legacies of our national heroes and magnificent leaders.

The FilAm culture and the Filipino homeland culture are super different, nuanced. It’s a different dynamic for a Latinx who speak Spanish or Portuguese or whatever their native language is - it reminds entitled white English-speaking America of their place in the continent. It should remind a racist white man whose roots hail from Denmark that his house in Los Angeles stands on what used to be the Mexican Empire.

Let’s use a specific cultural experience by a Black person for example: the black person not only has Smith or Johnson for their last name, but there is no single easy way for them to retrieve their family tree denoting which African country they were from, unless the Slave Trade has data as meticulous as the SALN forms. Let’s use a specific cultural experience by a Mexican-American with Native American heritage: the person is discriminated by a white US Border Patrol officer in the border of Texas. Texas used to be part of Mexico. Filipinos have a traceable lineage and a homeland.

Filipinos and FilAms may be enjoying the same food recipes, dancing the same cultural dance for purposes of presentations every once in a while, but the living conditions, the geography, the languages, social experiences, the human conditions are different, making the psychology, the politics, the social implications more disparate than Latinxs like Mexicans and Mexican Americans.

I don’t know if it is too much advertising from state instruments or from whatever but FilAms don’t realize how insensitive they have become in trying to shove a cultural tone down the throats of the citizens of the republic or of those who have closer affinity to it. And some Filipino homelanders who are very used to accommodating new global social trends without much sifting fall into the trap of misplaced passions.

To each his own, I guess. But FilAms should read Jose Rizal’s two novels, Carlos Romulo’s “I am a Filipino”, materials by Miriam Defensor Santiago (not just the humor books), speeches of Claro Recto, books by historians Gregorio Zaide, Teodoro Agoncillo, Renato Constantino, Nick Joaquin, Regalado Trota Jose, Fidel Villaroel, Zeus Salazar, Xiao Chua, and Ambeth Ocampo, and really immerse themselves in the struggle of the Filipino for an unidentifiable identity which the FilAms confuse for the FilAm culture. That’s a little weird because unlike Blacks and the Latinx movement, the Philippines is a real sovereign state which FilAms could hinge their history from.

I have to be honest. The homelanders don’t really care much about FilAm civil rights heroes Philip Vera Cruz and Larry Itliong, or even Alice Peña Bulos, because it was a different fight. But the media can play a role sharing it, shaping consensus and inadvertently setting standards. (But it’s slightly different for Peña Bulos, as people are realizing she was already a somebody in the Philippines before becoming a who’s who in the US, which is somehow similar to the case of Lea Salonga who was not only from the illustrious Salonga clan, but was also already a child star.) How much do Filipino millennials know about Marcoses, Aquinos? Maybe too serious? Lol. Then, let’s try using my favorite examples as a couch potato of newer cultural materials accessible to FilAms - cultural materials on television and internet.

FilAms who only watched TFC wondered who Regine Velasquez was when ABSCBN welcomed her like a beauty queen. Those with the GMA Pinoy TV have a little idea. But they did not initially get why the most successful Filipino artist in the US, Lea Salonga, does not get that level of adulation at home that Velasquez enjoys. Was it just Regine’s voice? No. Well, kinda, maybe, because there is no question that she is a damn good singer with God knows how many octaves, but it is the culture she represents as a probinsyana who made it that far and chose to go back home and stay - and that’s already a cultural nuance Filipinos understand and resonate with, without having to verbalize because the Philippines is a high-context culture in general, versus the US which is low-context culture in general. I mean, how many Filipinos know the difference of West End and Broadway, and a Tony and an Olivier? What does a Famas or a Palanca mean to a FilAm, to a Filipino scholar, and to an ordinary Filipino? Parallel those ideas with "Bulacan", "Asia", "Birit", "Songbird".

You think Coach Apl.de.Ap is that big in the Philippines? He was there for the global branding of the franchise because he is an American figure but really, Francis Magalona (+) and Gloc9 hold more influence. And speaking of influence, do FilAms know Macoy Dubs, Lloyd Cadena (+) and the cultures they represent? Do FilAms know Aling Marie and how a sari-sari store operates within a community? Do FilAms see the symbolic functions of a makeshift basketball (half)courts where fights happen regularly? How much premium do FilAms put on queer icons Boy Abunda, Vice Ganda? Do FilAms realize that Kris Aquino's role in Crazy Rich Asians was not just to have a Filipino in the cast (given that Nico Santos is already there) but was also Kris Aquino's version of a PR stunt to showcase that Filipinos are of equal footing with Asian counterparts if only in the game of 'pabonggahan'? Will the FilAms get it if someone says ‘kamukha ni Arn-arn’? Do FilAms see the humor in a Jaclyn Jose impersonation? Do FilAms even give premiums to the gems Ricky Lee, Peque Gallaga, Joel Lamangan, Joyce Bernal, Cathy Garcia Molina, and Jose Javier Reyes wrote and directed? (And these are not even National Artists.) How about AlDub or the experience of cringing to edgy and sometimes downright disgusting remarks of Joey De Leon while also admiring his creative genius? Do FilAms understand the process of how Vic Sotto became ‘Bossing’ and how Michael V could transform into Armi Millare? Do FilAms get that Sexbomb doesn’t remind people of Tom Jones but of Rochelle? Do FilAms get that dark humor when Jay Sonza’s name is placed beside Mel Tiangco’s? What do FilAms associate with the names ‘Tulfo’, ‘Isko’, ‘Erap’, ‘Charo’, ‘Matet’, ‘Janice’, ‘Miriam’, ‘Aga’, ‘Imelda’ and ‘Papin’? Do FilAms get that majority of Filipinos cannot jive into Rex Navarette’s and Jo Koy’s humor but find the comic antics of JoWaPao, Eugene Domingo, Mr Fu, Ryan Rems, and Donna Cariaga very easy to click with? Do FilAms know Jimmy Alapag, Jayjay Helterbrand, Josh Urbiztondo? Oh wait, these guys are FilAms. Lol. Both cultures find bridge in NBA, but have these FilAms been to a UAAP, NCAA, or a PBA basketball game where the longstanding rival groups face each other? Do FilAms know the legacy of Ely Buendia and the Eraserheads? Do FilAms know about Brenan Espartinez wearing this green costume on Sineskwela? Do FilAms know how Kiko Matsing, Ate Sienna, Kuya Bodjie helped shape a generation of a neoliberal workforce?

That list goes on and on, when it comes to this type of Filipiniana materials on pop culture, and I am sure as Shirley Puruntong that while the homeland Filipino culture is not as widespread, it has depth in its humble and high-context character.

Now, look at the practical traffic experiences of the homelanders. People riding the jeepneys, the tricycles, the MRT/LRT, the buses, and the kolorum - the daily Via Crucis of Mega Manila only Filipinos understand the gravity of, even without yet considering the germs passed as the payments pass through five million other passengers before reaching the front. Add the probinsyas, people from periphery islands who cross the sea to get good internet connections or do a checkup in the closest first-class town or component city. Do FilAms realize that the largest indoor arena in the world is built and owned by Iglesia ni Cristo, a homegrown Christian church with a headquarters that could equal the Disney castle?

Do FilAms know the experience as a tourist's experience or as an experience a homelander want to get away from or at least improved?

Do FilAms understand how much an SM, a Puregold, or a Jollibee, Greenwich, Chowking branch superbly change a town and its psychology and how it affects the Pamilihang Bayan? Do FilAms realize that while they find amusement over the use of tabo, the homelanders are not amused with something so routinary? Do FilAms realize how Filipinos shriek at the thought that regular US households do not wash their butts with soap and water after defecating?

Do FilAms understand the whole concept of "ayuda" or SAP Form in the context of pandemic and politics? The US has food banks, EDDs, and stubs - but the ayuda is nowhere near the first world entitlements Filipinos in the homeland could consider luxury. But, that in itself is part of the cultural nuance.

Do FilAms know that Oxford recognizes Philippine English as a diction of the English language? While we’ve slowly grown out of the fondness for pridyider and kolgeyt, do FilAms know how xerox is still used in the local parlance? Do FilAms know how excruciating it is to read Panitikan school books Ibong Adarna, Florante at Laura under the curriculum, and how light it is to read Bob Ong? Do FilAms realize that Jessica Zafra, with all her genius, is not the ordinary homelander’s cup-of-tea?

Do FilAms know that Filipinos do not sound as bad in English as stereotypes made them believe? Do FilAms really think that Philippines will be a call center capital if our accents sound like the idiolects of Rodrigo Duterte’s or Ninoy Aquino’s Philippine English accent? Do FilAms realize how Ninoy and Cory speak English with different accents? Lea Salonga's accent is a thespian's accent so she could do a long range like that of Meryl Streep if she wants to so she wouldn't be a good example. Pacquiao's accent shows the idiolect unique to his region in southern Philippines. But for purposes of showing an ethnolinguistic detail, I am using President Cory Aquino’s accent when she delivered her historic speech in the US Congress as a more current model of the Philippine English accent.

Do FilAms bother themselves with the monsoons, the humidity, and the viscosity of sweat the same way they get bothered with snowstorms, and heat waves measured in Fahrenheit?

Do FilAms know that not only heterosexual men are accepted in the Katipunan? Do FilAms even know what the Katipunan is? Do FilAms realize that the Philippines had two female presidents and a transwoman lawmaker? Do FilAms take “mamatay nang dahil sa’yo” the same way Filipinos do? Do FilAms know the ground and the grassroots? Do FilAms know the Filipino culture of the homeland?

These are cultural nuances FilAms will never understand without exposure of Philippine society reflected from barrio to lalawigan, from Tondo to Forbes Park. It goes the same way with Filipinos not understanding the cultural weight of Robert Lopez and the EGOT, or Seafood City, or Lucky Chances Casino, or what Jollibee symbolizes in New York, unless they are exposed.

The thing though is that while it is harder for FilAms to immerse to the homeland culture, it is easier for homeland culture to immerse into the FilAm’s because America’s excess extends to the propagation of its own subcultures, of which the FilAm’s is one.

We’re the same yet we’re different. But it should not be an issue if we are serious with embracing diversity. There should not be an issue with difference when we could find a common ground in a sense of history and shared destiny. But it is the burden of the Filipinos with and in power to understand the situation of those who have not.

Nuances. Nuances. Nuances.

And while I believe that changing a vowel into X to promote gender-neutrality has a noble intention, there is no need to fix things that are not broken. Do not be like politicians whose acts of service is to destroy streets and roads and then call for its renovation instead of fixing broken bridges or creating roads where there are none.

The word ‘Filipino’ is not broken. Since Rizal’s use of the term to refer to his Malayan folks, the formal process of repair started. And it is not merely codified, but validated by our prevailing Constitution, which I don’t think a FilAm would care to read, and I cannot blame them. What's in it for a regular FilAm? They wouldn’t read the US Constitution and the Federalist Papers; what more the 1987 Saligang Batas?

The bottomline of my thoughts on this particular X issue is that FilAms cannot impose a standard for Filipinos without going through a deeper, well-thought-out, more arduous process, most especially when the card of gender neutrality and political correctness are raised with no prior and deeper understanding of what it is to be a commoner in the homeland, of what it is to be an ordinary citizen in a barangay, from Bayan ng Itbayat, Lalawigan ng Batanes to Bayan ng Sitangkai, Lalawigan ng Sulu. It is very dangerous because FilAms yield more influence and power through their better access to resources, and yet these do not equate to cultural awareness.

Before Rizal’s political philosophy of Filipino, the ‘Filipino’ refers to a full-blooded Spaniard born in the Philippines, and since Spain follows jus sanguinis principle of citizenship, back then, ‘Filipino’ is as Spaniard as a ‘Madrileño’ (people in Madrid). The case in point is Marcelo Azcárraga Palmero - the Filipino Prime Minister of Spain.

But the word ‘Filipino’ was claimed by Rizal and the ilustrados to refer to whom the Spaniards call ‘indio’. The term was then applied retroactively to those who helped in the struggle. It was only later that Lapu-Lapu, Francisco Dagohoy, Gabriela and Diego Silang, Sultan Kudarat, Lorenzo Ruiz, and GOMBURZA were called Filipinos.

The word 'Filipino' was long fixed by the tears and sweat of martyrs through years of bloody history in the hands of traitors within and oppressors not just of the white race. The word Filipino is now used by men, women, and those who do not choose to be referred to as such who still bears a passport or any state document from the Republic of the Philippines. Whether a homelader is a Kapuso, Kapamilya, Kapatid, DDS, Dilawan, Noranian, Vilmanian, Sharonian, Team Magnolia, Barangay Ginebra, Catholic, Muslim, Aglipayan, Iglesia, Victory, Mormon, IP, OP, SJ, RVM, SVD, OSB, OSA, LGBTQQIP2SAA, etc., the word 'Filipino' is a constant variable in the formula of national consciousness.

Merriam-Webster defines Filipina as a Filipino girl or woman. Still a Filipino. Remember, dictionaries do not dictate rules. Dictionaries provide us with the meaning. To me, the word Filipina solidified as a subtle emphasis to the Philippines as a matriarchal country faking a macho look. But that’s not saying the word Filipino in the language is macho with six-pack.

The word Filipino is not resting its official status on the letter O but in its quiddity as a word and as an idea of a sovereign nation. The words Pilipino, Filipino, and Pinoy are not broken. What is broken is the notion that a Filipino subculture dictates the standard for political correctness without reaching the depth of our own history.

If the Filipinx-Pinxy-Pilipinx movement truly suits the Filipino-American struggle, my heart goes out for it. But my republic, the Philippines, home of the Filipino people, cradle of noble heroes, has no need for it (not just yet, maybe) - not because we don't want change, but because it will turn an already resolved theme utterly problematic. The Filipinos have no need for it, not because we cannot afford to consider political correctness when people are hungry, abused, and robbed off taxes. We could afford to legalize a formal way of Filipino greeting for purposes of national identity. But as far as the Filipinx, it should not be the homeland’s priority.

We may be poor, but we have culture.

From Julius Payàwal Fernandez's post

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

The nomenclature ‘Filipinx’ is so problematic

Recently, dictionary.com added the word “Filipinx” to refer to “ a native or inhabitant of the Philippines”. When this came to be known in the country, many are confused, upset, and even angry. And I get why.

It feels very much like recolonization since the nomenclature originated from the West. The proponents of this are mostly Filipino-Americans who grew up in the US. And this not an attack to them, or a denouncement because I understand the need to self-identify and to be inclusive. I don’t blame them per se because I know many 2nd and 3rd generation Filipino diaspora who were never able to learn the language and culture because of a need to assimilate and want to reclaim or reconnect to the culture. That is amazing! But the terminology and usage of “Filipinx” is laden with Western ideals and concepts.

The Filipino language is gender-neutral. People who push for the “filipinx” identity wanted to do so for the purpose of being inclusive to all gender identities. However, the word “Filipino” (or Pilipino in some local languages) is already gender-neutral. To claim that it needs to be changed disregards the inherent beauty of our language. If they are so adamant in wanting a gender-neutral term, then they need not to look further because our language already has one that embraces all gender identities. The Philippines has over 200 languages, all, except for one (Chavacano, a Spanish pidgin) are gender neutral. That’s 200+ languages you can choose from to self-identify.

And while yes, the term Filipino came about after the country’s name Philippines which was named after King Phillip of Spain, but we also have to be aware of the long history to re-claim Filipino as a word to refer to Filipino natives. The Philippines has a long history of colonization from the Spanish, to the Americans, to the Japanese. But despite that, our languages has remained. While other Spanish colonies adapted the Spanish language, Filipinos never adapted the language of the colonizers. Sure, we did borrow words and expressions, but that is the natural consequence of cultures interacting with one another.

And if you still want to use the term “filipinx”, then by all means feel free to do so. The problem, I think, is that it erases the hard-fought Filipino identity. Filipinos are proud to be Filipino because we have persisted and overcome 300+ years of colonization. We are still struggling to be truly independent politically and economically (a phenomena common to all post-colonial countries) but what has remained is that we identify as Filipinos -- all genders including -- and that we take pride in our many many gender-neutral languages. And if the Filipino diaspora really want a term for them to use, why not use our own language instead?

#filipinx#this is a shallow take but i am willing to go more in depth to any fil-ams or filipinos who want to discuss this with me

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Festival of the Body - Feb. 12 Opening Night - The Round Conversation

Festival of the Body’s Opening Night is February 12. Join us for a performance and Round Conversation with exhibiting student artists, faculty and community members on the themes of environmental justice & materiality; responsibility to others; and responsibility to self. Co-moderated by student Maya Skarzenski-Smith (Faculty of Art) and Sustainability Coordinator Victoria Ho (ODESI).

100 McCaul, Great Hall, Floor 2. Performance 5-6pm Round Conversation 6-8pm

Anne Bourne, Guest Speaker

Anne Bourne is a composer, interdisciplinary artist and teacher, based in Canada. Seasoned in international intermedia performance and song recording, Anne creates emergent streams of cello, and voice in contemporary dance, film, electroacoustic and improvised music, with artists such as Eve Egoyan and Mauricio Pauly, Christopher Willes, Silvia Tarozzi, and Felicia Atkinson. Anne imparts the text scores and deep listening® practice of composer Pauline Oliveros (1932-2016) offering an experience of collective creativity, symbiotic listening and place; as faculty at Banff Centre for Art and Creativity, Collective Composition Lab; The Acts of Listening Lab, Concordia, Montreal; and recently for Killowatt at Le Serre dei Giardini Margherita, Bologna, Italy; and as MMM_MM / Ensemble Vide artist in residence in Genève, CH 2020, Anne received a Fleck Fellowship in 2017 and a Chalmers Fellowship in 2019 to research cultural and environmental thresholds. Anne will compose and perform ‘her body as words’ a new work exploring indigeneity and female identity, by choreographer Peggy Baker in March 2020. Anne believes creative expression is an opportunity for subtle evolution, through listening.

Jody Chan, Guest Speaker

Jody is a writer, drummer, organizer, and therapist-in-training. They believe deeply in the importance of storytelling, care, and joy in movement-building. They work at The Leap, organize with the Disability Justice Network of Ontario, and drum with the Raging Asian Womxn Taiko Drummers.

Dr. Sanja Dejanovic, Guest Speaker

Dr. Sanja Dejanovic is a thinker in motion and in relation with otherness. She engages multiple media and modes of expression to explore sympoiesis; the together making of space, time, and sense by living beings. She did her SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellowship work at Senselab and CISSC at Concordia, Montreal and Bard, NY, and a PhD on sense in Gilles Deleuze’s writings at York University. Interested in Western and Eastern somatic praxis, Sanja has training in sensorimotor psychotherapy and mindfulness. She has organized butoh practice labs in Toronto since 2017 and offers workshops through her somatic learning lab Body Ecologies.

Sanja is a published author, an editor, and a curator, most notably of the text (Jean-Luc) Nancy and the Political (Edinburgh University Press, 2015). She has curated Becoming-Elemental at Seneselab, Sonic Fabulations, and most recently Line. Bridge. Body. Sanja has performed and shared her work domestically and internationally, including at EPTC, The School of Making Thinking, Somatic Engagement CATR (Canadian Association for Theatre Research), Arts Unfold--Water Residency, and most recently, with Mika Lior, scores for Listening With/In Nonhuman Publics in connection with the Ecology & Performance Working Group at the 2019 American Society for Theatre Research. She is passionate about collaborating with other artists in her community. Sanja is from Skopje, Macedonia.

Johanna Householder, Guest Speaker

Johanna Householder works at the intersection of popular and unpopular culture in video, performance art, and choreography. Her interest in how ideas move through bodies has led her often collaborative practice and inform her research and writing on the impact that performance and other embodied practices have had in contemporary art and new media.

She has recently performed at the VIVA! Festival in Montréal, Performancear o Morir (Perform or Die in Norogachi, Mexico. In 2017, she reset her 1978 solo improvisation, 8-Legged Dancing, on dancer Bee Palomina in Residuals, a presentation of her performance works at the Art Gallery of Ontario, curated by Wanda Nanibush.

Her video collaborations with B.H. Yael and with Frances Leeming We did everything adults would do, what went wrong? have screened in venues internationally.

With Tanya Mars, she has co-edited two anthologies of performance art by Canadian women: Caught in the Act: (2005), and More Caught in the Act (2016). She is a founder of the 7a*11d International Festival of Performance Art which will hold its 13th biennial festival in Toronto in October 2020. She is a Professor in the Faculty of Art and Graduate Studies, and currently Chair of Cross-Disciplinary Art Practices.

Marissa Largo, Guest Speaker

Marissa Largo is a researcher, artist, curator, and educator whose work focuses on the intersections of race, gender, settler colonialism, and Asian diasporic cultural production. She earned her PhD in Social Justice Education from OISE, University of Toronto (2018). She is a recipient of the 2019 Outstanding Dissertation Award from the Research on the Education of Asian and Pacific Americans (REAPA) special interest group of the American Educational Research Association (AERA). Her book manuscript, Unsettling Imaginaries examines Filipinx artists who adopt decolonial diaspora aesthetics as counternarratives to the dominant stereotypes that persist in Canada. Her art and curatorial projects have been presented in venues and events across Canada, such as the A Space Gallery (2017 & 2012), Open Gallery of OCAD University (2015), Royal Ontario Museum (2015), WorldPride Toronto (2014), and MAI (Montreal, arts interculturels) (2007). Dr. Largo is co-editor of the anthology Diasporic Intimacies: Queer Filipinos and Canadian Imaginaries (Northwestern University Press 2017) and serves as the Canada Area Editor of the Journal of Asian Diasporic Visual Cultures and the Americas. Marissa is the Department Head of Visual Arts and Technology at a self-directed secondary school in Toronto and a sessional instructor at the Ontario College of Art and Design University.

Julius Poncelet Manapul, Guest Speaker

Julius Poncelet Manapul is a migrant Filipinx artist from the Ilocano tribe, with Spanish heritage and Cherokee ancestry; a descendant of Maria Josefa Gabriela Carino de Silang, known as an anti-colonial fighter during the 18th century Spanish rule over the Philippines—the first female leader of a Filipino movement for independence from Spain. This background informs their research and artistic practice, as they excavate the experience of immigration and assimilation through cultural erasure.

Addressing eternal displacement through themes of colonialism, sexual identity, diasporic bodies, global identity construction, and the Eurocentric Western hegemony, Julius’ artwork focuses on the hybrid nature of Filipinx culture after colonialism and the gaze of queer identities as taxonomy. Their recent research project looks at the narratives for many diasporic queer bodies that create an unattainable imagined space of lost countries and domestic belongings through colonial pedagogy of knowledge and globalized imperial power. Hybrid images question the problematic side of queer communities that uphold homonormativity through whitewashing and internalized racism, and act to challenge forms of oppression.

Julius was born in 1980 Manila, Philippines and immigrated to Toronto in 1990, attained a BFA from the OCAD University in 2009, A Professional Practice Certificate at Toronto School of Art in 2011, and completed a Masters of Visual Studies and a Sexual Diversity Studies Certificate from the University of Toronto in 2013, and an Apparel Tech in the Fashion Exchange Program at George Brown Collage in 2019. Their work had been presented at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Koffler Gallery, University of Waterloo Gallery, A Space Gallery, PM Gallery, Propeller Gallery, Nuit Blanche in Toronto (2010, 2012 & 2014), and WorldPride Toronto (2014), Julius’ work had been featured on CBC Series “Art is My Country” 2018 and “Art Works” 2017, Julius’ research had been published in Academic Journals titles “Diasporic Intimacies: Queer Filipinos and Canadian Imaginaries” and “Asian Diasporic Visual Cultures and the Americas” Vol 1. They have exhibited works in Canada, UK, France, Germany, and US.

Anna McMullen, Exhibiting Artist

Anna McMullen is constantly painting over old and new works of hers, never fully satisfied, never able to truly make up her mind about the final form of her art. This process is a reflection of her stream of consciousness; the continuous flow of thoughts, opinions, and emotions running through her mind. And in the context of these specific works, we are speaking about her ambivalence toward the desire to be seen as beautiful and to fit into the mould versus not wanting to conform to oppressive narrow standards of beauty. By painting self-portraits and using pentimento, Anna wants to express her indecisiveness; “Do I want to conform to standards of beauty, or do I want nonconformity?” Just like the final form of her work, she will never know.

Ehiko Odeh, Exhibiting Artist

The principle subject matter explored in Ehiko’s artworks are the tradition Nigerian masks, identity, sexual violence and the representation, perception of Black hair in Nigeria and Canada. Her artistic style is characterized through an expressive pallet, and the use of a variety of textiles. Ehiko also emulates the traditional Nigerian practice of craftsmanship through her multi-medium paintings, performances, drawings and installations. Her use of diverse mediums is a result of a belief that “Nigerian art” cannot be interpreted through just one form, but rather through a range of artistic expression.

James Okore, Exhibiting Artist

Throughout James Okore’s life, he’s been questioning the barriers of misunderstanding and misinterpreting others through language. This is especially true for somebody like himself with an “invisible disability.” He’s been trying to acknowledge his own actions and the ways in which he might come off towards others, and to take ownership in that. It’s a struggle at times to decipher language, and to understand whether or not to continue conversing with people, if he’s not able to pick up on subtle verbal/non-verbal cues. He’s always trying his best to understand the nuances of language, and in many cases, he finds himself confused in the process of understanding others. This piece entitled “Barriers of Language Unspoken,” addresses the essence of the BODY through his efforts in conveying an internal battle with himself trying to understand others, externally, which captures these emotions and feelings through a vessel, represented visually through the BODY.

Ash Randall-Colalillo, Exhibiting Artist

Introducing Ash Randall-Colalillo; pronouns are she/her. She is a queer interdisciplinary artist studying within her fourth year of Drawing and Painting. She creates through many varying mediums such as performance, sculpture/installation, video and drawing/painting. She allows her choice of medium to be driven from conceptual thought. Over a couple of years, her practice has developed to focus on the study of self or self-illusion/reflection, the body and the relationships they have with spaces, objects and moments. The witnessing bodies perceptions of her work within those relations motivates the "experience" to be a large part of her process when creating. She consistently questions what is an experience, and how can an experience be shared or private and what that displays for and in the work. Once understanding what an experience is within this methodology, the work expands larger than the product itself.

The piece that she created titled "FLESH FUNCTIONS” was an early exploration of this process. It is displaying a physical study of bodies and the experiences they have with vessel-like objects. Through having knowledge from the theory “The Thing” by Martin Heidegger that she studied within a class she took, she was able to use this knowledge to reflect on the relationships we make with objects as “things” and deconstructed these items and the functions of them in an abstract lens. This led to challenging the idea of the ‘thingly’ qualities within objects and their relationship dynamic with bodies mentally and physically.

In regards to this challenging, she begs the question - how do ‘ordinary’ objects gain these qualities to become or identify as things? How do they work differently, once the relationship between body and object becomes more complex within identification? This is where she aims to construct a different phenomenon of these objects and exchanges by using her physical form to "embody" the object. She attempts to take away the relationship of functionality of an object as its self and display those functions through the ‘thing’ that those objects are functional for - the body - thus becoming flesh functions.

0 notes

Text

Resisting Silence through Music: Asian Diaspora & Queer Identities

“I had supposed that I was practicing passive resistance to stereotyping, but it was so passive no one noticed I was resisting. To finally recognize our own invisibility is to finally be on the path toward visibility. Invisibility is not a natural state for anyone” (Mitsuye Yamada, 1979). In Invisibility is an Unnatural Disaster: Reflections of an Asian American Woman, Mitsuye Yamada urges Asian American women to strive toward visibility and resist the pressure to remain silent about their lived experiences. We wish to explore how Asian immigrants have navigated their multicultural and queer identities through music. In the United States and other Western countries, musicians with Asian ethnicities and heritage are often “othered,” with the label of “perpetual foreigner” imposed on their image, even if they have lived in the United States their entire lives. Here are some examples of musicians in the Asian diaspora who use their voices and music to affirm their Asian and queer identities, however they wish to define it.

youtube

1. Ruby Ibarra

Ruby Ibarra is a Filipina-American rapper who immigrated with her family from Tacloban City, Philippines to San Lorenzo, California. Living in the Bay area where hip-hop was a formative element of her childhood and adolescent years, Ibarra raps in Tagalog (Filipino language) and English. Through music she speaks about growing up with the colonial mentality of whitewashing, growing up as an immigrant family assimilating to US culture, and reclaiming pride as a filipina. She has said that she does not attempt to represent or define the immigrant experience for every individual, but that “[she] hopes people find moments in these songs where they feel represented.” As a non-black POC whose music largely focuses on the genre of rap music, there is definitely room to argue the nuances of using black culture for her music. It seems like Ibarra has taken steps to address this issue—on her social media platforms like instagram, she often gives tribute/credit to the black community: “I recognize my privileges as a non-black POC, and the beautiful culture and genre of music I’ve been able to participate in that was created by the black community.” (instagram post from February 1, 2018). She also takes action as an ally to use her platform in speaking out against police brutality: “Police (and media) typically justify the shootings by saying they were armed-- does being black cancel the right to bear arms? ...We need a system that doesn’t target a group of people. We need a system that doesn’t kill a group of people...The long history of system racism has led to mistrust and fear of law enforcement.” (instagram post from September 21, 2016).

Listen to her album Circa91. I recommend “Brown Out,” “Someday,” and “Us.”

youtube

2. Rina Sawayama

Rina Sawayama is a Japanese-British R&B pop musician. She was born in Niigata, Japan and immigrated to London, England with her family when she was 5 years old. In a 2018 Broadly interview, Zing Tsjeng describes Sawayama’s character as a “tangerine-haired, cyberpunk-influenced musician slash model.” A central theme that Sawayama explores in her music is romance and alienation in the internet-obsessed society that we live in.

In “Cherry,” Sawayama takes the opportunity to publicly vocalize her pansexual identity. She describes the song as her most personal but political song, and has contemplated past moments of shame around her queerness. For Sawayama, “Cherry” is a love letter of affirmation for bi and pan people who don’t feel authentically queer when they’re heterosexual relationships <3 <3 <3

During her studies at Cambridge in England, Sawayama felt alienated, different, and undesirable in an environment where over 60 percent of its student population is white and British. Later in life, Sawayama has found communities and families as she has continued her journey as a musician. She has spoken about the many emerging queer Asian artists active in many different genres: “We’re so protective of our space, even who we decide to sign to, who we decide to release through, or who we decide to work with. It’s really important to us. Because as queer Asians, there’s not that many of us and we really want to get it right.” To Sawayama, it’s important to her that she’s representing queer Asians, rather than just ‘Asian’. She wants to queer the world with pop music.

youtube

3. Japanese Breakfast

Michelle Zauner is a Korean American musician who takes the name Japanese Breakfast for her musical project that emerged as a way for Zauner to navigate her grief and memory of her mother’s terminal illness and death. Through music Zauner has found healing as well as a way to reckon with her Korean American identity. In the New Yorker essay “Crying in H Mart,” Zauner speaks about the identity crisis of losing her mother, who is her last connection to her Korean heritage.

Growing up in Eugene, Oregan, a predominately white town, Zauner hated being half Korean. She could barely speak the language and didn’t have any Asian friends. There was nothing about herself that felt Korean, except when it came to food. She has written an essay called “real Life: Love, Loss, and Kimchi” about the comforting power of food as a device of healing through her mother’s struggle with cancer.

On the moniker “Japanese Breakfast”, Zauner wanted a name that combined elements of something iconically American (breakfast) with something “American people just associate with something exotic or foreign” (Japanese). People often assume she’s Japanese, and Zauner says that she can tell who that real fans are—they know she’s Korean. She likes that the moniker exposes those who assume she’s Japanese.

Listen to her albums Psychopomp and Soft Sounds from Another Planet for trips of nostalgia and longing and contemplation on life and death and love and grief around identity and family <3 <3

youtube

4. Hayley Kiyoko

Hayley Kiyoko is a Japanese-American singer, songwriter, actress and director who was born and raised in Los Angeles, California. She has shown interest in music as early as 5 to 6 years of age when she got her first drum kit and wrote her first song. It was also around this age that she knew that she liked girls.

Since she was young, Kiyoko has combated the loneliness that comes with being a queer asian in society. She worked as an actress during her childhood, exposing her to discrimination due to her biracial physical appearance. Several rejections due to her appearance was enough to plant the seeds of doubt about whether she was enough. In addition, she kept her sexual orientation to herself in fear of being ostracized even further—only coming out to her parents in sixth grade. Unfortunately, her parents refused to acknowledge this confession, stating that it was just a phase.

She continued to keep her sexual orientation a secret which isolated her even further from her friends. She found it depressing to watch girls that I liked flirt with guys, so she stayed at home during her free time. Later on, she had her heart broken by her best friend which devastated her for a period of time. The constant rejection that Kiyoko had received until then prevented her from being comfortable with who she was, putting her in a state of perpetual fear.

In order to appeal to more of an audience, her songwriters wanted her to sing about topics that she personally connected to. As a result, she came out to her songwriters which inspired “Girls Like Girls,” a song that referenced her experience as a lesbian. Also, in putting out music videos that actually show the narrative that she sings about, she fights the heterosexual narrative that restricts the LGTBQ community in today’s society. Using her music as vehicle of representation, she unites a group of isolated individuals, earning her the nickname “Lesbian Jesus.”

By confronting her past fears and illustrating them in a form with which she loves and performs, she becomes the idol that she never had.

0 notes

Text

Army Base Stew for the Amerasian Soul

On existing as reminders of the trauma of U.S military occupation in Korea

Youtube / Seonkyoung Longest

Budaejjigae is always served in massive pots. Kept piping hot on a Butane burner, the dish is meant to be shared with a table full of people.

With a name that translates to “military base stew,” this dish is largely made up of cheap, processed food. Korean ingredients like Neoguri ramen, kimchi and rice cakes are mixed in with seemingly contrasting American ingredients, such as Spam, hot dogs, and Kraft cheese. It’s often eaten by students and young adults in Korea as a form of inexpensive comfort food.

During U.S military occupation, “camp towns” started to form around the gates of American army and air force bases. The Koreans that lived and worked in these towns often depended on U.S soldiers for the bulk of their income, whether they were bar owners, tailors, or one of the thousands of Korean women who provided sexual services to U.S soldiers. These towns didn’t just develop on their own, either — the South Korean government, backed by the U.S, encouraged the development of camp towns and coerced Korean women to provide sexual labor for American soldiers in order to ensure their stay and improve the economy.

Some people regard budaejjigae as the original Korean-American fusion dish. Others just consider it a bad memory.

***

I grew up in Songtan, a former Korean camp town surrounding a U.S air force base. Like many other “Amerasian” children, I attended an American elementary, middle, and high school on the base along with other American military brats.

Unlike many of the white and non-Korean families who chose to live in on-base housing, my mom vehemently wanted to live in downtown Songtan. Her argument was that we wouldn’t be able to order all the yummy Korean delivery foods, like jjajangmyeon and fried chicken, if we lived on the military base.

It wasn’t until later that I realized this was an excuse. There seemed to be an unspoken acknowledgment in my family that my mom simply wouldn’t be able to assimilate into typical military spouse communities on base— the book clubs, potlucks, and church gatherings comprised mostly of Christian, American, English-speaking women (usually white, with some exceptions).

This enclave carved out of the Western, patriarchal culture of military life seemed unwelcoming to her. Instead, she removed herself almost entirely from it — and yet she still stayed within proximity, making friends with other Koreans who lived and worked in the camp town, from bar owners to street vendors to other Korean military wives.

Together, they formed their own enclave under the influence of U.S military occupation.

Every morning, my school bus would pick me up in downtown Songtan and take me to the gates of Osan Air Force Base. There, a helmet-clad soldier with a rifle would step on our bus and check all of our military ID cards that marked us as “dependents”.

Walking through the front doors of my typical American school, along with a hundred other atypical Amerasian military brats, felt like jumping from the ocean into a fish bowl. We suddenly found ourselves in a bubble, closed off from the rest of the world, but still able to see out into it.

***

In 1945, after over three decades of brutal colonial suppression, Koreans finally saw independence from the Japanese empire.

Koreans found themselves seized from Japanese colonial rule and almost immediately thrust, once again, into the control of foreign nations. Like children fighting over a room, the United States and Russia each claimed half of Korea’s territory. The north, backed by the Soviet Union, would be led by anti-imperialist communist Kim Il-sung. The south, backed by the United States, would be led by staunchly anti-communist, right-wing authoritarian Yi Seung-Man, who had succeeded in winning what many considered to be a rigged election.

The Cold War had begun, and Korea found itself, through no choice of its own, caught in the middle of it.

“The Korean peninsula would serve both as a living laboratory for technologies of domination and as a site of contestation over the United States’ fantasy of itself as a nation of saviors.”

— Grace M. Cho, Haunting the Korean Diaspora: Shame Secrecy and the Forgotten War

The magnitude of death, trauma, and destabilization that affected the Korean people during and after the Korean War is still immeasurable. Even official statistics don’t always account for the massive loss of civilian life.

During the war, the U.S-backed authoritarian leader of South Korea, Yi Seung-man, committed massacres against his citizens to suppress communists, leftists, and anyone who opposed U.S military occupation. Meanwhile, the United States launched a brutal aerial bombing campaign against North Korea that killed 20 to 30 percent of the population, an incident that has been compared to attempted genocide. Even in the South, mass killings like the No Gun-Ri Massacre left men, women, and children dead at the hands of U.S soldiers, who were instructed by officers to kill any civilians in the combat zone without discretion.

The war never really ended. In 1953, the Korean Armistice Agreement was signed, ensuring a ceasefire between the two countries and officially establishing the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) at the 38th parallel.

***

The city of Uijeongbu, near the U.S army base Camp Casey, takes credit for the invention of budaejjigae. I often visited my friends there, where the dish is a local staple. Restaurants claiming to have served budaejjigae since the end of the Korean War lines the alleyways.

“The stew had long been the stuff of my nightmares. A stew gone wrong. A stew so laden with Spam, hot dogs, American cheese and other “food products” that it had become a perversion of Korean cuisine, indeed, a perversion of real food. Since it represented both the U.S. military occupation of Korea, and my own hidden past, I never thought I could bring myself to eat it.”

— Grace M. Cho, Eating Military Base Stew

Food scarcity, especially a shortage of meat, was a severe issue for Koreans during the war. U.S military bases, on the other hand, seemed to be overflowing with food that would end up in the garbage. The solution? U.S military bases began allowing Koreans to purchase bags of the leftover food. Sometimes hungry people would simply scavenge for it in the trash, occasionally finding inedible ingredients like cigarette butts. To this day, Koreans still joke that you can find cigarette butts in a pot of budaejjigae.

Coincidentally, the birthplace of budaejjigae is prominent for another reason that’s also related to U.S military occupation. In 2002, an armored vehicle operated by U.S military soldiers struck and killed two Korean schoolgirls while returning to base in Uijeongbu. Despite the requests of the South Korean Justice Ministry, the soldiers were tried in U.S military court, where they were found not guilty. The complete acquittal of the soldiers reignited anti-American and anti-U.S military sentiment that had been bubbling in Korea since the war.

The aptly named “military base stew” owes its very existence to the traumatic consequences of war and foreign intervention. The unlivable circumstances caused by the Korean War and prolonged U.S military occupation— massive civilian casualties, loss of infrastructure and industry, widespread famine, rises in sex trafficking and sexual violence— led to circumstances that required Koreans to survive on scraps of food left by their foreign occupiers.

Now budaejjigae is occasionally touted as a symbol — sometimes of the collision of two dynamically opposed cultures, and other times of the trauma of U.S military occupation and post-war poverty.

***

U.S military presence in South Korea continues to this day, with 28,000 to 33,000 troops still stationed on the peninsula. The former “camp towns” are now cities in their own right.

The areas surrounding U.S military bases are still heavily peppered with clubs and “G.I bars”, many of which serve as a front for brothels. Historically, the women who worked there were derisively referred to as yanggongju.

Yanggongju. Western princess. The literal translation is much kinder than the actual interpretation of the word — the most accurate equivalent would be “yankee whore.” Any Korean woman who kept the company of American soldiers could have this word hurled at them, whether they were married to one, lived with one, or served them in bars and brothels.

“She is the woman who simultaneously provokes her compatriot’s hatred because of her complicity with Korea’ s subordination, and inspires their envy because she is within arm’s reach of the American dream.”

— Grace M. Cho,

It was often the so-called yanggongju who were able to acquire the ingredients needed for budaejjigae. Many of the women would sell American food products that they received from soldiers. At one point, there was a thriving black market in South Korea for American food products. Even one of my Amerasian friends admitted to me that his mother dabbled in the market, selling American beef and Kraft cheese when they were short on money.

***

Pearl S. Buck, the author of The Good Earth, was the first to coin the term “Amerasian.” Eventually, the word became the official term used by the U.S state department to describe the children of American military service-members and Asians (usually women) in the country of their station. I have not yet encountered another term that describes this specific group of people.

Amerasians have widely differing experiences of social stigma, racism, colorism, and political and social disenfranchisement. For one, Amerasians from the Philippines have been repeatedly excluded from legislation that allows overseas Amerasians to immigrate to the United States. Not only that, but there are currently an estimated 30,000 or more “Kopinos” (children born to a Filipino mother and Korean father), the majority of whom are unable to receive assistance despite being legally entitled to child support under Korean law. In an ironically similar circumstance to the American soldiers who left Korean women with Amerasian children, Korean men indulge in relationships with Filipino women and leave without taking responsibility for their families.

Almost all of my friends from school were Amerasian, with few exceptions. We related to each other on many similar experiences — the food we ate at home, the things we did for fun off-base, the Korean and American holidays we celebrated— while simultaneously leaving so much unspoken.

None of us ever brought up or questioned the history and circumstances that led to our seemingly contradictory lives — American kids with Korean heritage, living on Korean soil, learning American history and culture that didn’t even acknowledge our existences or the intergenerational trauma we inherited.

You would have thought that it was merely a coincidence that we all happened to have Korean mothers and American fathers.

Though it occasionally felt isolating, I had a community of sorts. Unlike Amerasians who grew up in Korea with single mothers or were placed in orphanages, we were able to attend U.S Department of Defense (DOD) schools on military bases.

In other words, we had the immense privilege of assimilating into American culture— if we wanted to.

***

Since the Korean War, more than 160,000 Korean children have been sent overseas for adoption. A disproportionate number of those children are mixed-race or were born to single mothers. It was all too common for American servicemen to father biracial children with Korean women before leaving the country once their military tour ended.

As a result, these women were left to raise their children as single mothers while facing harsh social stigma. Meanwhile, the South Korean government searched for a wayto quietly remove hundreds of thousands of mixed-race children by opening up international adoption. The presence of these children were associated with Korean sex workers, camp towns, and U.S military occupation — as a result, they were considered undesirable. Many Korean mothers gave up their mixed-race children to orphanages for international adoption, believing that their children would have a better life overseas. This was especially true for Afro-Amerasians, who were less likely to pass for Korean and experienced the intersecting effects of anti-blackness and cultural stigma against mixed children.

When discussing the stigma that mixed-race children and their mothers experience in Korea, the blame is often placed on Korean culture and society for preaching a narrative of racial purity or for being historically patriarchal. While these are accurate observations, it’s important to consider the role of collective, intergenerational trauma reaching back to the Korean War and Japanese colonization. Just as the term yanggongju is fueled by generations of anger toward the United States for aiding in the loss of Korea’s autonomy and independence, so is much of the discomfort, shame, and disgust expressed toward Amerasians.

To many Koreans, Amerasians are a living reminder of the trauma caused by U.S military occupation in Korea. Amerasians exist as living proof of the existence of the yanggongju. In her book, Haunting the Korean Diaspora: Shame, Secrecy, and the Forgotten War, Cho describes the yanggongju as an unspoken, ghostly memory — a specter left over from a traumatic past that reaches back to years of foreign invasion and institutionalized sexual violence affecting Korean women.

***

“Aigoo-ya, they probably sending money to their family,” my mom would say. She was talking about other Korean women married to American servicemen, probably one of the mothers of my many Amerasian friends.

“Mimi-chan, you know I come from rich family, right?” My mom scowled. “I married your daddy because I love him. He come from poor family, you understand?”

I didn’t understand why she would tell me this. I already knew my dad was poor. He was the son of a janitor and a truck driver and grew up in rural Oklahoma. He enlisted in the military right out of high school and was stationed in Korea, where he met my mother in the camp town — likely in a “G.I. club.”

And I certainly knew my mom had been wealthy — she would never shut up about her grandma’s rice fields, even though she never saw a cent of her inheritance because she had the misfortune of being the only daughter in her family.

As a child, it seemed mean-spirited to me. Why ridicule women who are just trying to survive? I thought. Why ridicule my own family because they grew up poor?

Now I realize that she had been plagued with a complex cocktail of emotions. Resentment, anger, pride, and most of all: fear. Anger at the stigma that she had to face for marrying an American servicemen. Anger at her country’s loss of autonomy to the United States and the trauma her parents and grandparents went through. Resentment at the loss of her inheritance and the loss of her family’s support. Pride in the face of people who assumed that her family must be relying on my white American father’s money when, in fact, it was the other way around.

Fear, the immense fear, that her daughter would grow up to know the word yanggongju. That I would grow up to learn what so many people think of children like me. That I would learn to hate her and hate myself.

Some women in this position keep silent. Perhaps by leaving the past unspoken, it will simply fade, just as the Korean War faded into the Forgotten War.

Other women, like my mom, desperately want to take control of the narrative. She wanted to make sure she was the first to tell me her story, the way she saw fit.

I’m not like them, she seemed to say. I am someone. Which means you’re not like them, either.

Recently, I told my mom that I’m making arrangements to study abroad in South Korea for a semester. She’s still strongly against the idea of me returning there.

“You better not go to some G.I. club,” she yelled at me. “I don’t want to see you at some place like that! You hear me?”

The fear that I would repeat history. Girls become lovers who turn into mothers.

***

Mom’s 부대찌개 (Military Base Stew)

Ingredients

Jin Ramen

Kimchi

Spam (sliced long and thin)

Ground beef

Hot Dogs (chopped thin diagonally OR cut into octopus shape)

White onion

Green onion

Tofu (sliced into thin rectangles)

Dukguk (thin sliced Korean rice cakes)

Kraft American cheese slices

Gochugaru (Korean chili pepper flakes)

Gochujang (Korean chili pepper paste)

White rice

Optional: Baked beans, Mandu (Korean dumplings), Chicken broth

Directions

1. In a shallow pot, put the kimchi, ground beef, white onion, ramen noodles (with the contents of the flavor packet and vegetable packet), and about a tablespoon of gochujang at the bottom. Add the chicken broth as well if needed. (OPTIONAL: grill or pan fry the sliced hot dog)

2. Pour as much water as needed for the broth (about 2 ⅓ cups for each person being served or for each pack of ramen used).

3. Throw the sliced spam, hot dog, green onion, and tofu on top. If you’re using mandu, throw only a few on top and make sure it’s submerged in the broth. Sprinkle over with gochugaru.

4. Budaejjigae is traditionally cooked on a Butane burner or hot pot right on the table in front of your friends and family. If you don’t have a hot pot or burner, just cook it on the stove. Bring the water to a boil and then let it simmer once the noodles, dukguk, and mandu are tender and cooked.

5. While the stew is still hot, add a couple slices of Kraft American cheese on top, and baked beans if you’re using it. Serve with a bowl of white rice on the side.

Original Article : HERE ; This post was curated & posted using : RealSpecific

=> *********************************************** Learn More Here: Army Base Stew for the Amerasian Soul ************************************ =>

Army Base Stew for the Amerasian Soul was originally posted by News - Feed

0 notes