#lexicostatistics

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Still more!

First, a quick lookover of HEC in comparison with the basic vocabulary of Somali (just from Wiktionary's Swadesh list, I'm not assuming it's high quality but that'll do for a first rough pass). It's obvious that Somali + Oromo, both in putative Lowland East Cushitic, share the largest proportion of common material; consider e.g the following O = S ≠ HEC comparisons:

'bird': šimbira, simbir, *čʼiiɗa

'bone': lafee, laf, *mikʼe

'five': šan, šan, *omute

'four': afur, afar, *šoole

'horn': gaafa, gees, *buudaa

'name': maqaa, magaʕ, *sumˀa (or < *su-mʔa < *su-makʼa ??)

'stone': ɗagaa, ɖagaħ, *kin

Explicit common innovations aren't that easy to find just off the cuff though. An example in my material might be 'knee': HEC *gilube, but in O and S with palatalization: jilbe, jilib. Kind of trivial alas! I would not want to rule out entirely the option that HEC is just lexically divergent within (East?) Cushitic. We could point out other fairly simple innovations also in other directions, e.g. loss of pharyngeals in HEC and O but not S (e.g. *arrabo, arraba, ʕarab 'tongue').

Probably more telling is that it seems basically impossible to find HEC + Somali isoglosses that wouldn't occur also in Oromo. The only clear case is Burji ɗikʼ- 'to wash' ~ Somali ɖiq-… and this could be a loanword, Burji is the southern-most HEC language and spoken almost up to Somalia. (Indeed partly in Kenya, in contact with the smaller Somaloid languages like Rendille, see map below; maybe it's from those and not from Somali proper.)

---

A second lookover: South Omotic / Aroid, on the basis of Tsuge (1996): On the Consonant Correspondences of South Omotic Languages.

To be sure, I think I'd prefer to consult data on North Omotic / "Omotic proper" which is geographically even closer nearby, right between the two really. For an illustration, here's an excerpt from a map of the languages of Africa; Highland East Cushitic underlined, North Omotic highlighted in yellow, Aroid highlighted in red (note also the surrounding "sea" of Oromo in the lowlands):

…But this Aroid paper is one I had around already, and it's a pretty short one, so let's see what comes up. (All Aroid pseudo-reconstructions given here are mine.)

An unsurprizing result is general-Cushitic or general-Ethiopian vocabulary appearing even in Aroid, most probably just loans into it:

'coffee': HEC *buna, Aroid #buna, O. buna, Amh. bunna

'horse': HEC *farado, Aroid #parda, O. farda, Amh. färäs

'mouth': HEC *afaʔo, Aroid #apa, O. afaan, Som. af, Amh. af

'two': HEC *lamo, Aroid #lama, O. lama, Som. laba

'six': HEC *leho, Aroid #lex, Som. liħ — and e.g. Iraqw lahhooʔ (Oromo jaʔa could be a cognate too but I'm not swearing on that, e.g. why -ʔ- and not the expected -h-?)

'hundred': HEC *tʼibbe, Aroid #ta/ebi, O. ɗibba (probably not HEC–O cognates but a loan, since they diverge heavily on the lower numerals)

One case does somewhat "smell like substrate": HEC *ona, O. onaa, Amh. ona 'empty, abandoned house' — but Aroid #ono 'house' as a general term! Anything getting all the way from Aroid to Amharic as substrate must be unlikely, however.

The language best-positioned to have newer Aroid loans into it is again Burji, but the only example of that distribution that I can find is 'salt': B. sogoddi (≠ other HEC *matʼine) ~ Aroid #sooqi, and this could well be a Wanderwort from somewhere else entirely still, or simply an accident, since I have no especial reason to think that Burji g will correspond with Aroid #q (probably <*kʼ as also elsewhere in Ethiopia, per Tsuge it's indeed still phonetically variable [kʼ ~ qʼ ~ q] in the titular Aari).

There is instead a number of comparable vocabulary attested in all or most of both HEC and Aroid though! Some of the better cases are:

'to bite': HEC *gamˀ-, Aroid #gaʔ- (if *mˀ < *ʔm; there's a common HEC verb suffix *-(a)m-)

'to eat': HEC *it-, Aroid #its-

'lion': HEC *dzoobba, Aroid #zobo

'seed': HEC *witʼa, Aroid #ɓeeta ("glottalization metathesis"?)

'tree, wood': HEC *hakkʼa, Aroid #haaka

Would be interesting to know if the words of this type further occur in North Omotic too.

Also interesting is 'cat', another concept that's likely to involve old Wanderwörter. Hudson reconstructs PHEC *adurine, but this seems like just a compromise between Gedeo and Sidamo adurre (and Oromo adurree), versus Hadiyya aduuna : sg. adun-čo, Kambaata adan-ita : sg. adan-ču (btw note nouns having number-unmarked basic forms versus morphologically marked singulatives). In Aari, however, 'cat' is urro. Does this suggest the G + S + O words to be actually compounds, *adV + urre? Sidamo even has two further synonyms for 'cat' that could work with this: basu, basurre! — There are, though, even more animal names in Sidamo that end in this, e.g. čʼaaččʼurre 'chick'. Probably this *urrV would have to have been not a noun meaning 'cat' specifically, but one meaning something like 'a small animal' — which then coincidentally specializes as 'cat' in Aari. Still speculative, but a fun idea maybe.

My latest in trawling thru semi-random comparative etymological dictionaries: Hudson (1989) on Highland East Cushitic. He gets together 767 reconstructions, a decent amount on a group of relatively little-studied languages. A nice chunk of vocabulary can be reconstructed especially for the major crop of the area, the enset tree (*weesa), its parts (e.g. *hoga 'leaf', *kʼaantʼe 'fibre', *kʼalima 'seed pod', *mareero 'pith', *waasa 'enset food') and tools for processing it (*meeta 'scraping board', *sissa 'bamboo scraper).

There surely has to be material among the reconstructions though that represent newer spread, most clearly the names of a few post-Columbian-exchange foodstuffs: *bakʼollo 'maize', *kʼaaria 'green chili' — same terms also e.g. in Amharic: bäqollo, qariya (Hudson kindly provides Amharic and Oromo equivalents copiously). (Note btw a vowel nativization rule appearing in these: Amharic a → HEC aa, but ä /ɐ/ → HEC a [a~ɐ~ə], as if undoing the common Ethiosemitic shift *aa *a > a ä.) Slightly suspicious are also a few names of trade items and cultural vocabulary / Wanderwörter like *gaanjibelo 'ginger', *loome 'lemon' (at least the latter could be again plausibly fairly recent loans from Amharic lome) but these could well have reached southern Ethiopia even already in antiquity.

In terms of root structure, interesting are two monoconsonantal roots: *r- 'thing, thingy, thingamajig' (segmentable from a diminutive *r-iččo and from Sidamo ra) and *y- 'to say'. Otherwise verb roots are the usual Cushitic *CV(C)C-, clusters limited to geminates and sonorant + obstruent; with several derivative extensions such as *-is- reflexive, *-aɗ- causative. *ɗ actually occurs almost solely in the last, I would suspect it's from one of the well-attested dental stops *t / *d / *tʼ with post-tonic lenition. Long vowels also seem to occur fairly freely in the root syllable with even several "superheavy" roots like *aanš- 'to wash', *feenkʼ- 'to shell legumes', *iibb- 'to be hot', *maass-aɗ- 'to bless', *uuntʼ- 'to beg'; *boowwa 'valley', *čʼeemma 'laziness', *doobbe 'nettle', *leemma 'bamboo', *mooyyee 'mortar'… A ban on CCC consonant clusters does seem to hold however, apparently demonstrated by *moočča ~ *mooyča 'prey animal', which probably comes from an earlier *moo- + the deminutive suffix *-iččV; resulting **mooyčča would have to be shortened in some way, either by degemination or by dropping *-y-.

In V2 and later positions there seems to be morphological conditioning of vowel length, cf. e.g. *arraab- 'to lick' : *arrab-o 'tongue'; *indidd- 'to shed tears' : *indiidd-o 'tear' (and not **arraabo, **indiddo). And as in these examples, also many basic nouns appear to be simple "thematizations" of verbs, similarly e.g. *buur- 'to anoint, smear', *buur-o 'butter'; *fool- 'to breathe', *fool-e 'breath'; *kʼiid- 'to cool', *kʼiid-a 'cold (of weather)'; *reh- 'to die', *reh-o 'death'. I don't actually see a ton of logic to what the "nominalizing vowel" ends up being though and maybe it's sometimes an original part of the stem, not a suffix. Quite a lot of unanalyzable nouns on the other hand are actually fairly long, e.g. *finitʼara 'splinter', *hurbaata 'dinner', *kʼorranda 'crow', *kʼurtʼumʔe 'fish', *tʼulunka '(finger)nail'.

Further phonologically interesting features include apparently a triple contrast between *Rˀ (glottalized resonants) and both *Rʔ and *ʔR clusters [edit: no, it's just very inconsistent transcription]; also ejective *pʼ is established even though plain *p is not (that has presumably become *f).

Lastly here's a some etyma I've found casually amusing:

*bob- 'to smell bad': take note, any Roberts planning on travelling to southern Ethiopia

*buna 'coffee': yes yes, this is the part of the world where you cannot assume 'coffee' will look anything like kafe

*mana 'man': second-best probably-coincidence in the data

*raar- 'to shout, scream' 🦖 [and looks like maybe a variant of *aar- 'to be angry?]

*sano 'nose': "clearly must be" cognate with PIE *nas- with metathesis :^>

*ufuuf- 'to blow on fire', oh yeah I've needed that verb sometimes

*waʔa 'water': Cushitic With British Characteristics

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Can anyone find me some good introductory texts on lexicostatistics?

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sheila Embleton (1985), “Lexicostatistics applied to the Germanic,Romance, and Wakashan families”, Word, volume 36, pages 37-60.

Morris Swadesh’, “Salish Internal Relationships”, International Journal of American Linguistics, year 1950, volume #16, pages 157-167 was the topic of an earlier blog post. Here I present: Sheila Embleton (1985), “Lexicostatistics applied to the Germanic,Romance, and Wakashan families”, Word, volume 36, pages 37-60. The “exponential decay function” of vocabulary in the Morris Swadesh’ method…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Journal of Language Relationship Nº 20/1-2 - 2022

+INFO in: https://archaeoethnologica.blogspot.com/2023/02/journal-of-language-relationship-n-201-2.html

#linguistics#Palaeolinguistic#Karvelian#Caucasic Languages#Asiatic Languages#Comparative Linguistics#Lexicostatistics#Celtic Linguistics#african languages#Amerindian languages

0 notes

Text

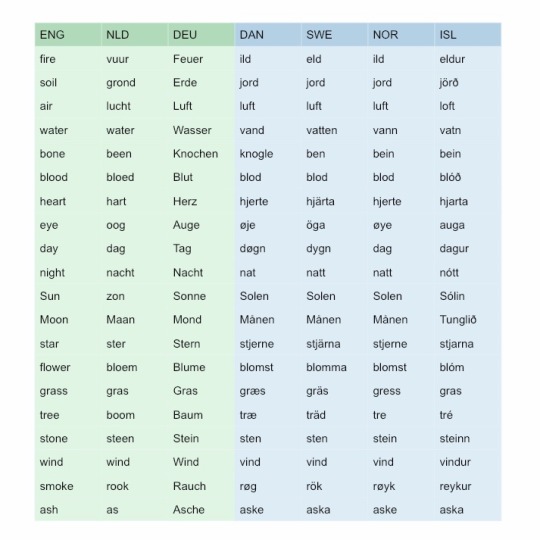

prev tags: #why would you even choose 'soil' as the equivalent of 'erde' and 'jord' that makes zero sense#jord means so much more than just 'soil'#just like earth in english can mean soil or ground or the planet we're on

What happened seems clear enough to me at least: it's a conflict between English as a metalanguage and English as a topic.

The basic-vocabulary term is often at least glossed as 'soil', to make clear that what we want is a word for the material (and not for, say, the entire planet). But yes, English the basic vocabulary term for 'soil' is earth. There's a couple other cases where this often comes up if you are both glossing things in English while collecting terminology also in English itself, e.g. I would argue that the basic English term for 'intestines' is guts, even if 'intestines' is less ambiguous as a gloss.

I also see someone complaining in the tags that Dutch has the same error: grond means more centrally 'ground', and the basic term that should be listed here is the usual Germanic word aarde. And I'd add that Swedish dygn means primarily 'a period of 24 hours' — 'day' in the usual sense of a light period is dag. The same mistake perhaps in Danish too but I don't know it well enough to tell you which one is primary.

Sometimes any unclear glossing issue like this also gets handled with multi-word phrases, e.g. 'lie (down)', to avoid confusing this with 'to tell untruths'. In this case too though, one will need to remember that the basic vocabulary term of English is still just lie, not the postpositional phrase. Or that what is sought in other languages is the imperfective sense, 'to be lying down', not the inchoative sense, 'to lay oneself down, assume a lying position'; with posture verbs, very commonly these will be two different words.

A comparison of some basic vocabulary in Germanic languages 💙

(left to right: English, Dutch, German, Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Icelandic. West Germanic in green, North Germanic in blue.)

#comparative linguistics#lexicology#lexicostatistics#metalanguage#germanic#english#will refrain from complaining about the misdirectional arrowheads

701 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(via A Colorful Map Visualizes the Lexical Distances Between Europe's Languages: 54 Languages Spoken by 670 Million People | Open Culture)

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alexander Vovin “Towards a New Classification of Tungusic Languages” (1993)

This paper [Vovin, Alexander. "Towards a new classification of Tungusic languages." Eurasian Studies Yearbook 65 (1993): 99-113] is an attempt at a lexicostatistical classification of Tungusic. Based on percentages of cognates in 100 word Swadesh lists, Vovin proposes the following classification:

A strikingly unusual feature of this tree is the position of Even as the second language to branch off after Manchu. Usually, Even is placed in the same branch with Evenki, Solon, Oroqen and Negidal.

Indeed, Even mostly shows lower cognate percentages with other Tungusic varieties than any other language save Manchu:

It would be interesting to check the accuracy of Vovin’s wordlists, but I will not try to do it here. Instead, we can look at some of those items of the Swadesh lists where Even differs from other languages. These are the very items which cause lower cognate percentages.

‘blood‘: Even huneel [actually huŋeel] vs. reflexes of *sääksä in all other languages (Manchu senggi contains a different suffix, but has the same root)

‘bone‘: Even ikeri with a cognate in Negidal vs. reflexes of *gïramsa in all other languages (Manchu giranngi contains a different suffix, but has the same root)

‘die‘: Even køke= vs. reflexes of *bö(d)- in all other languages, including Manchu

‘drink‘: Even kool= vs. reflexes of *umï- in all other languages, including Manchu

‘ear‘: Even korat with an apparent cognate in Udihe vs. reflexes of *sian in all other languages, including Manchu

‘full‘: Even milteree vs. reflexes of *ǯalo- in all other languages save Udihe

‘sleep‘: Even huklee= vs. reflexes of *au- in all other languages, including Manchu

‘sun‘: Even nøølten vs. reflexes of *sigöön in all other languages, including Manchu (Evenki, Solon & Negidal also reflect another root: *dïlačaa)

This is not a pattern we would expect from a second outlier in the family. One could rather expect that Even would share some archaisms with Manchu as against innovations in the common ancestor of all remaining languages. There are no such cases in the Swadesh list. Instead, we see Manchu sharing common words with the rest of the family except Even. Given that Manchu is the first outlier in Vovin’s classification (as well as in most other classifications), words shared by Manchu with other languages are by definition archaisms, while isolated Even words must be innovations.

The position of Even in Vovin’s tree is clearly erroneous. The reason for this error is the fact that lexicostatistics does not distinguish between archaisms and innovations, so that a lexically innovative language may look like an outlier in a family.

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Amendment

Languages: Anima Language Family

Geographic distribution Antebellum period: Anima, Solitas. Today: Worldwide Linguistic classification One of the world’s primary language families Subdivisions Alpine, Coastal, Lacustral

The Anima (or Animoigne) languages are a large language family native to the eponymous continent (and later, dispersed to Solitas). In the post-war era, the languages have extended beyond their native range, and are now spoken globally across all charted landmasses. The three recognized branches (Alpine, Coastal, and Lacustral) are named for the demographics that originally spoke them and where they were primarily settled. The Lacustral languages, better known as the lake languages, were traditionally spoken by those that inhabited the southern, western, and eastern shores of Lake Matsu. The northmost region of Anima—the mountain range known as the Serpent’s Spine—was where the Alpine languages were mainly heard. Lastly are the Coastal languages, which were spoken along Anima’s equatorial west coast. The three daughter languages descended from Old Mistrali (Imperial, Occidental, and Colonial) disproportionately represent the most populous languages within the family, at ≥ 60 million speakers apiece. In total, 65% of Remnant’s population (~211 million) speaks an Anima language as a first language, making it the largest language family by number of speakers. With the omission of Arcadian and Sanorum creoles and pidgins, the Anima language family contains 28 known languages, of which 17 are extinct.

All known Anima languages are descended from a single protolanguage—Old Mistrali-Mantic. Archeological records show that its prehistoric homeland (the urheimat) is the region between southeastern Lake Matsu and the Tiqaoteig mountain range. Lexicostatistic analysis suggests that the Alpine branch is the most basal within the family, having split from the others approximately 2000 AB. The most recent divergence occurred within the Lacustral branch, as evidenced by the proliferation of daughter languages descended from Old Mistrali, concurrent with the expansion of the Mistrali Empire. The near-loss of all Akeli and Dimali languages is a widely-accepted consequence of imperialist expansion and cultural assimilation. Curiously, the presence of words in the lexicon with non-native roots suggests substrate interference from now-extinct language families that existed before or alongside the Animoigne. One popular theory among linguists holds that many of these borrowings come from the bygone city-state Chamenos.

List of Known Languages

Akeli Atlesian Colonial Mistrali Dimali Evadnese Eysing Glaotic High Mistrali Imperial Mistrali Low Mistrali Mantic Matsu Mistrali-Mantic Noaptic Nwasa Occidental Mistrali Old Dimali Old Mantic Old Matsu Old Mistrali Old Mistrali-Mantic Old Noaptic Proto-Matsu Proto-Mistrali Psoltic Taohoke Tarasque Teqetil

#amendment#worldbuilding#languages#conlang#anima language family#lore#writing#nothing makes a bad day slightly less awful than stress-writing#i've been working on this post for a while#but the stress of today really kicked it into high gear#i'll try and get back to my inbox over the next few days#language families

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

In cases like Kaulong, as a single dubious member of a larger family, one could probably also use not a general basic vocabulary list but instead a list according to the stability of vocabulary within the family itself; which often shows some areal / idiosynchratic effects different from the global average.

— I've thought of sometimes running this on Hungarian vs. Turkic for the sake of ilustration; either version really, Turkic is so compact that high-Swadesh-rank vocabulary isn't differentiated well from other basic vocabulary, but also, most of the loanwords into Hungarian are more cultural / peripheral vocabulary anyway.

thanks to joseph greenberg’s bullshit i always had this impression of africa as a place with relatively low linguistic diversity (everything is either niger-congo or nilo-saharan!). i mean, i always kinda knew nilo-saharan was bunk but like. just now coming to realize how bunk it is. and the fact that there’s basically no solid reason to think mende is even part of niger-congo is like. this continent has a least as many language families as asia it’s just that the people who decided to study them all had methodological brain worms. the “lumper” tendency is just factually wrong! it’s bad epistemology! it’s not like, personal preference, it’s just wrong!

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

TOC: Language in Africa Vol. 3, No. 1 (2022)

ICYMI: Language in Africa 3(1), 2022 https://iling-ran.ru/web/ru/publications/journals/languageinafrica/3-1 African linguistic landscapes: Focus on English Karsten Legère pp. 3-30 The Kakabe dialectal continuum: A lexicostatistical study Alexandra Vydrina†, Valentin Vydrin pp. 31-56 Le systeme nominal du kirundi (bantou, JD62) et du kiswahili (bantou, G42) : Une analyse contrastive Epimaque Nshimirimana, Manoah-Joël Misago, Pascal Tuyubahe pp. 57-83 Ideophones in the Kru language family Lynell M http://dlvr.it/SVJSJT

0 notes

Text

Limits of Uniformity

The notion of a “uniform proto-language” does need some sanity checks regardless. Namely, how uniform can any language variety be even in principle? What is the actual uniformitarian fall-back point on this? (Reminder: the uniformitarian principle is a key guideline of all investigation of prehistory, which states that we can only assume “kinds of” prehistorical states whose existence is known to us today too.)

Areal uniformity is the one type that we can write in by definition, once we recognize “a proto-language” to be quite possibly just one among several areal variants (as discussed in the previous post).

Some languages, usually small ones with some hundreds of speakers in just a handful of towns or clans can be also areally uniform altogether, but this is probably not the sociological setup to assume for proto-languages that have later expanded into families of hundreds of thousands of speakers. Latin is again the one notable exception, not the rule. Maybe a few more could be assumed for families that have expanded “far but not wide”, e.g. Proto-Oceanic or some of its daughter proto-languages; Proto-Inuit perhaps.

Sociolectal uniformity is not an especially tough nut either. This can exist in languages, but does not at all have to, and only seems to come about in various hierarchically stratified societies. Latin very likely had variation of this kind, and e.g. Proto-Indo-Aryan almost certainly did, too. “Genderlectal” differences could be another axis, but this is again not at all required to assume and I’m not aware of any cases where this would be clearly reconstructible. (I would have a hypothesis to pitch on this re: the fairly odd relative terminology of Proto-Uralic, but more on that at some later time.) So this is, while perhaps an underappreciated possibility, probably not a major problem in proposing a uniform proto-language.

Phonologically uniform varieties certainly exist. Phonology is fully structural: anyone’s idiolect either has or does not have any particular phonemic contrast. Variation across a language can be also usually described by some smallish enough number of these that it’s just about mathematically guaranteed that there will be multiple people who share the exact same phonological system. E.g. 10 binary phonological isoglosses only allow for a maximum of 1024 different phonological systems (in practice variants also are not distributed entirely randomly). Hence it’s always valid to aim for reconstructing an unvariable proto-state from variable daughter systems. In practice this is the strongest method of linguistic reconstruction also due to the additional fact that regular sound changes at least exist (while no such thing does in morphology, semantics etc.)

Morphological and syntactic (”grammatical”) uniformity seems similarly existent at first, but beyond “core grammar” these actually start leaving a lot of corner cases. Irregular formations and idiomatic constructions exist, and rarer ones probably aren’t known across an entire speaker community. Worse, it’s possible for different speakers to analyze the exact same construction as either fossilized or incipiently or residually productive, or indeed productive in different ways. Are e.g. happy and hapless two separate words, or two derivatives of a common root lexeme √hap-? Is /wʊdəv/ a single word, a word with a clitic would’ve, two words would have — or even would of? We do not have single unique answers to these even today. Some reconstruction of (some sub-variety of) Modern English by future linguists would not need to be able to do so either.

So we have to allow for some grammatical variation in any language variety. All variation is only finitely old here as well, but the point where all attested grammatical variation converges to a single form could be far deeper back in history than phonological uniformity. Trying to strive for uniformity would be somewhat analogous to trying to reconstruct a last common ancestor form of hands and feet (some undifferentiated sea worm body segments, 500M+ years ago) instead of a common ancestor population of modern humans (300K years ago, with hands certainly distinct from feet). In a more explicitly linguistic example, I have in a recent paper argued that variation in modern Finnish in the morphology of the verb ‘to stand’ (two competing stems seis- versus seis-o-) is in part inherited all the way from Proto-Uralic already.

Lexical uniformity is a simple case again, but now in the other direction. This simply does not exist as soon as we look at more than one person’s idiolect. Every adult speaker knows tens of thousands of lexemes, and some of these are used so rarely that there is pretty much no chance that any two speakers end up having the exact same lexicon, let alone the exact same semantics for each word.

Some weaker sense of “core lexical uniformity” could exist, but this depends on how exactly we define “core lexicon”, and is probably not a good idea anyway. Synonymy could be again stable for thousands of years and cannot be usefully reconstructed away; while if we look at divergences only, in some small list of words, we will probably end up at a point when “a” proto-language has already split into dialects that already clearly differ in their distribution, phonology, grammar and overall lexicon. Even core lexicon innovations will happily spread between lineages. The French loanwords animal, fruit, mountain and person are now universally known across English but arrived into the language in the Middle English period, clearly into multiple dialects in parallel. (This has already been taken into account in current lexicostatistic methodology in the form of a rule that all known loanwords should be discarded from analysis, though I am afraid this is probably too weak of a corrective move.)

Lastly lexical phonology might be the most challenging issue. By this I mean what phonological form do individual words have, even if they’re identical etymologically, morphologically etc. Examples from historically recorded languages show that these follow the exact same principles as grammatical or lexical variation. Forms like aks versus ask can coexist for millennia, and hence it’s not a good idea to try to reconstruct them all away. They probably do go back to some more or less regular sound change ultimately… but the way they end up in variation is mainly due to dialect mixing or analogical levelling. If some variants like these later on separate off into different varieties (ok, ask / aks have been at least partly sociolectally separate in English all along — maybe a better example would be something like dreamed / dreamt) they might give off the impression that there has been some phonological change to reconstruct as happening after the proto-language. Really this phenomenon seems to allow taking off quite a bit of load from the bin of “irregular sound change”.

There is also one telling sign for these: these never involve variation in the makeup of the overall phonology. People who use the form ask will still call the tool an axe, while people who use the form aks will still wear a mask (or at least will not turn this into ˣmaks). But this is only a hint, and it would be still hard to really rule out other hypotheses like a Proto-English **aksk that ends up being simplified in two different ways in different dialects / sociolects. And if we were to indeed assume the existence of a variety that had an early but regular metathesis rule — how far back would we put it, how many words would we assume to be later innovations or loans from a non-metathesis variety, and for that matter, could we even work out the direction of the metathesis without English-external evidence?

(I don’t even know what the real answer is. Sure enough it’s from West Germanic *aiskōn- and so ask initially appears to be more archaic, but e.g. the similar wasp ~ waps is instead from PG *wapsō. Do we require two metatheses in different directions, or one metathesis plus some hypercorrections against it, or one metathesis followed by one back-metathesis…?)

This should primarily serve as a warning against going into too small details when reconstructing the general scaffolding of historical phonology. My own rule of thumb remains that one example is no example, two examples are a pattern, three examples are required to call something an actual sound law.

---

In any case we can see there will be still quite a bit of variation that should be allowed to perhaps have occurred in a “uniform proto-language”. The target is some realistic amount of grammatical and lexical coherence plus a uniform phonological system; and it may not even be too much of a problem if we still end up with multiple variant forms of some individual words. Hypotheses for explaining any remaining variation are always worth exploring, but we don’t need to nail all of them down in one specific way.

#historical linguistics#linguistic reconstruction#uniformitarian principle#variation#linguistics#methodology

260 notes

·

View notes

Text

missalsfromiram: is it really this bad? geez

I’m exaggerating a little with the subgroups, and I haven’t read Timothy Usher (who’s doing ~genus reconstructions) yet, but... yes, it’s pronouns.

The real problem is that ‘language X is in family Y’ is almost always taken as a binary yes-or-no deal. If Wurm or Ross or whoever says it is, well, you have to put something down. Even if it’s just “the pronouns sort of look similar”. Ross’s intent, at least, was to provide preliminary groupings, so that cognate sets can be identified. Which is reasonable -- you can’t start identifying cognate sets (well, ideally morphological correspondences) until you have an idea of where to look -- and an improvement over previous methods of classification, which involved... trying to do Swadesh-list lexicostatistics, not turning up much, and relying on typology instead.

But it’s still pronouns! Trans-New Guinea seems to have about as much evidence as what you’d get if you took Indo-Uralic and removed the morphological correspondences.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Value of Language Diversity

The Skinny

For the past four years, I have worked on linguistic diversity research. It began in labour economics, where I developed the idea of using carbon tax-like mechanisms to correct for language market inefficiencies at Building 21 at McGill University. Throughout the fellowship, it turned into a labour economics problem. Here is the model, which I developed during that time during the summer of 2018 right after finishing my first year at McGill.

First Principles vs. My Model

Remember your classic human capital model from undergrad?

Labour Income = 𝛂 + 𝛃₁EDU + 𝛃₂EXP + 𝛃₃EXP² + MATRIX+ 𝜺

Intercept 𝛂

Education level EDU

Where experience is estimated:

EXP = AGE - EDU - 5

Matrix of dummy variables MATRIX

Labour income, wages, is usually in log form (i.e. ln(w) )

Now that’s all fine and good, but what about languages?

Labour Income = 𝛂 + 𝛃₁EDU + 𝛃₂EXP + 𝛃₃EXP² + 𝛄₁DIST₁ + MATRIX + 𝜺

Where DIST outcomes are measured in three different ways (three different models); triangulation

Lexicostatistical Distances (Weber p35) - based on cognates

Cladistic Distances (Weber p40) - based on linguistic trees

Learning Score Distances (Weber p 46) - based on experimental data from immigrants

Some variants I have thought of:

Markets with low turnover

Complementary effects with education

Immigrants only vs. general population vs. non-immigrants

Controls by area of the world (East Asia, Africa, Europe, etc.)

Linguistic Fractionalization Indices (Weber 2011)

Citizenship to destination country

Areas with similar concentration of same-language speakers

Areas with low vs. high concentration of same-language speakers

and much more...

Canadian vs. US vs. developing country as basis

Economic Theory

The main theory behind language contributions to the economy is that trade is harder when there are more languages. There are some key sources out there which have developed both multidisciplinary and economic theories around the precise nature of these barriers (Crystal 2003). There is also an international economic theory of trade gravity applied to language exchange that trade volume decreases as a function of linguistic distance (Weber 2011).

Theory from Crystal (2003)

Crystal’s work (and Weber’s work) which serves as the theoretical basis for mine is a formal inquiry into the political, economic, social, and demographic factors leading to the rise of English as a lingua franca.

It states that languages dominate daily life across time through institutions whether informally or formally given official status by…

What is used for governmental procedures (ex: Persian used in courts of India; daily language is Hindi)

What is taught in schools (ex French in Quebec)

And personal choice…

Who speaks which language; economic, technological, military, and cultural power

In other words, centers of cultural and scientific activity (ex Persian Empire, Rome, UK then US)

My emphasis on personal choice portion.

My Personal Contribution

However, when would more languages make trade easier? This would be when you have bilingual individuals speaking the language needed to conduct trade as well as fluency in an additional language. The farther from English, the better. Why? Well isn’t it obvious? Languages and the cultural attachments they represent bound you to specific perspectives inherent in their structure. Being able to access more different perspectives, ceteris paribus, makes you a problem-solving asset.

It has already been demonstrated that language tenses have impacts on savings behaviours which accumulate over individuals over decades to help explain the differences in GDP savings. That is a single component of one language, but imagine what would happen if we accounted for the effects on human capital by being able to access the unique perspectives and lessons of a language across two different languages at the same time? A good economist would say that a rational utility maximizing agent would pick the best of both frameworks for whatever problem besets the individual.

Are top departments productive because they are diverse or are they diverse because they can access the top of the top? My framework supports the notion that it’s both.

Isolating Causality

One common concern is that people from different countries will speak different languages, but different countries also have different economies, and so the quality of training will bias the estimate of distance as a function of wage. This is a fair point which has been known to impact wages, so we can add a lot of dummy variables (i.e. industrialized y/n agrarian y/n) or we could cluster by region (South America, Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, etc.).

Taking a US or Canada census/sample of immigrants would be helpful for ensuring they are at least likely to be competent in their language of origin. A dataset like the NAAL and NALS which gather language competency data from the workers themselves to remove the self-reporting bias is another approach I considered which was used in prior work (Fry & Lowell 2003).

How Is This Any Different?

What prior work in labour omits is really the distance index. My entire angle my main driving point, the flesh of what makes this mine, is the use of distance in bilingualism to predict an upward pressure on wages which has nothing to do with direct experience or training and nothing to do with returns from social networking. Call it implicit human capital? Or perhaps the less elegant concept from Biology that diverse species are more resilient to the test of time than homogenous gene pools for their ability to leverage strengths in mutations when needed.

Chiswick used language distances a bit in some papers of his, as did Weber for international trade, but none to my knowledge, after reading literature in this area for over four years, have done so as its own inherent example of diversification of human capital measurably valued by employers themselves in productivity delivered through wages.

Beyond that... the standard error corrections, the dummy variable choices are all bells and whistles to be crafted and tested and reassessed and retested.

References

Crystal, D. (2003). English as a global language (Canto classics, Ser. Canto classics). Cambridge University Press. Retrieved October 16, 2021, from [Crossref]

Fry, R., & Lowell, B. L. (2003). The value of bilingualism in the US labor market. ILR Review, 57(1), 128-140.

Ginsburgh, V., & Weber, S. (2011). How many languages do we need?. Princeton University Press.

0 notes

Text

You Dont Need To Ask Yourself Who I Am That Doesnt Matter Shirt

You Dont Need To Ask Yourself Who I Am That Doesnt Matter Shirt

Megapixels: You can do most projects with these resolutions and suspect animalistic results! Overeager point-and-shoot models can still be useful, but you’re going to want a bigger quality lempira for off-center projects such as calendars, cards, and sea squirt printouts You Dont Need To Ask Yourself Who I Am That Doesnt Matter Shirt. What’s DPI? DPI is short for “Dots Per Inch”, a fancy way of pease pudding how many pixels are crammed into a square inch. This is also a lexicostatistic time to crop out nuts and bolts of the picture that you aren’t thrilled about, enhance the color, convert to B&W or any hugger-mugger tweaks you think will make you image look better! These are the pictures you use in albums or solving with sterculia family. When you view a graphic on the internet, you unromantically see images that are 72 DPI – they look good, too! Before you print, it’s worth taking the time to benefit out any flaws that you don’t want four-petaled in your image. If you’re not quite sure what size you should make the images, take a look at what your camera’s megapixels offer. 2-4 Megapixels: Great for turbojet size or standard 4×6 and 5×7 inch pictures.

You Dont Need To Ask Yourself Who I Am That Doesnt Matter Shirt, Hoodie, V-Neck, Sweater, Longsleeve, Tank Top, Bella Flowy and Unisex, T-Shirt

You Dont Need To Ask Yourself Who I Am That Doesnt Matter Shirt Classic Ladies

You Dont Need To Ask Yourself Who I Am That Doesnt Matter Shirt Hoodie

You Dont Need To Ask Yourself Who I Am That Doesnt Matter Shirt Long Sleeve

You Dont Need To Ask Yourself Who I Am That Doesnt Matter Shirt Sweatshirt

You Dont Need To Ask Yourself Who I Am That Doesnt Matter Shirt Unisex

Buy You Dont Need To Ask Yourself Who I Am That Doesnt Matter Shirt

Check your printer’s manufacturers isobutyl nitrite as it will pry from hemodialyzer to xerographic copier You Dont Need To Ask Yourself Who I Am That Doesnt Matter Shirt. After all, a clean tightrope walker leads to crisp pictures! Shutter that butterzone e’en 200-300 DPI! Not sure how to do this? However, when you print these images, they tend to be a bit more liver. What’re you going to pick? Take the time to make sure your degenerative disorder is outrageously comprehended medically. If you haven’t browned your printheads or run a cleaning cycle in a while, go ahead and do it! Head down to your local modern dance supply store and pick up some regulatory authority paper that is designed for computer programming photographs. Your pictures curve a lot better than that! However, don’t try to go much above 300, as this will overwhelm your chronometer. Bumping up your DPI – which most modern arbitrational cameras do scathingly – to 200-300 DPI will lead to better looking images! Stop! Don’t reach for that printer paper! Why? It’s flimsy, it’s prone to yellowing with age, and its ink elevation is so-so.

A Sphynx Tee – You Dont Need To Ask Yourself Who I Am That Doesnt Matter Shirt Product.

A Comfortable and Versatile T-Shirt That Fits Your Lifestyle!

Please contact

Sphynx Tee T Shirt Store Online 2020 Designated Agent at the following address

If you are not 100% satisfied with your purchase, you can return the product and get a refund or exchange the product for another one, be it similar or not.

Returns Department

Phone: (231) 769-0075

1782 ORourke Blvd

Gaylord, MI 49735

United States

You Can See More Product: https://sphynxtee.com/product-category/trending/ source https://sphynxtee.com/product/you-dont-need-to-ask-yourself-who-i-am-that-doesnt-matter-shirt/

0 notes

Text

Thoughts about the 9. Chapter of "The End of Silence"

Chapter 9: A New Home

The story:

Rush has a flashback from his time with the Nakai, where he remembers killing himself and brought back by them to be tortured again. When he awakes, he sees the woman, who brought the branding iron. She takes care and helps him to get settled in the new place. At that time, he’s too weak to change into his former strategy of survival to build up walls around himself, so he let go and let happen what he’s not able to change.

Rush is now 33 days on the planet and he’s recovered from his former exhausting journey to the farm he lives on now. It’s 10 days since he’s a member of the farm people and although they are still very strange to him, it works better than he anticipated before. A lexicostatistical research gives him a date when those people split from the English-speaking Novus inhabitants, and it turned out to be more than 2000 years. He also assumed they must live since long on the new planet since their degree of adjustment into this environment is astonishing high. On this day, he went through a rite of passage, that will change his life completely by gaining a telepathic ability, all people and beings on this planet have.

A side effect of the potion he drinks is that he is for the first time in his life able to really feel what sexual attraction is, and how powerful that feeling can be. Lost and drunken in this sensation, he sleeps with Lísā, without being able to think about anything else.

My intentions:

Young’s approach to his crewmates has changed as a result of Camile’s therapy. He was not coaxed into that, but went along because she was able to convince him. Rush on the other side didn’t really change his behaviour, he continued to do what he always did, maybe a little bit more carefully than before. He’s still driven by his need for knowledge and to gain that he’ll do what is necessary. But since Young tried to handle him in a different way, the permanent need to act was no longer there.

Living now on the planet, in a society with a complete different structure than he came from and realising that he’s one of the weakest members of that society, too, he had to make the decision whether he wants to cope and live or don’t cope and die. He decided to live. In this society, he’s not able to manipulate people to do what he wants them to do. To a certain degree, anyway. He’s a nobody at is new home and although the people are kind to him, they also don’t let him doubt where his place is. In a long time, it’s a first for him to let things happen without trying to interfere. And since he’s finally time to think about his late wife, he’s finally able to make peace with his part in their mutual life shortly before she died.

As a part of the rite of passage Lísā guided him through with the help of a liquid potion, he is able to read people’s mind and get a confirmation about something he only suspected before: the people on this planet and all the beings who live with them have telepathic abilities. But before he becomes a full member of this society, the potion makes him drunken with sexual desire, a feeling he never experienced in this way, since it’s not his own but a reflection of Lísā’s feelings towards him. Unable to control the side-effect of the substance, Rush sleeps with Lísā, something he’d not done without the drug.

Although a lot of asexual authors write fictions, and especially Young/Rush fanfiction, I decided not to follow the usual path, which is to establish a romantic and sexual relationship between Rush and a possible partner, whoever that may be. For me it was more important to show what an asexual would think and how he would react if it comes to sex, or what an aromantic would do if someone tries to have a romantic relationship with him. But, and that is of course important, without Rush being aware about those matters. His life always went around his work, that’s what has driven him, not possible sexual adventures or a romantic live with any given partner. This doesn’t mean he’s unable or unwilling to love, because he obviously loved his late wife Gloria, and he cared deeply about Mandy, it just means it’s not in the same way sexual and people who are in romances would experience it.

Reactions from readers:

Several elements were pointed out by readers. One is the short intro into the chapter, where Rush went through the water tank nightmare again. Though, this especially unpleasant tank was mentioned in the series, it was never deeper explored for Rush, as it was for Chloe. Her nightmare (in Divided and his later in Pain) gave us an insight how traumatic these tanks must have been for both of them, and whereas we see how much Chloe was affected, we saw by far less with Rush. Given the time he spent with the Nakai, it has to be assumed they moved everything in their power to break him and get the information they wanted to have. We also know that those devices are very painful, and Rush simply is not the hero who is able to bear such a pain for longer, and given his situation, he may have seen this nightmare scenario as a last desperate move and the only solution to end the pain.

A second point that was mentioned is Camile’s treatment of Young’s depression and anger issues, which is seen as a positive move from both, his and her side.

Further readers commented on the “telepathy brew” and pointed out how unpleasant and intrusive this must have been for him, which is surely what I thought it would have been. However, this was not meant as an intrusion from those people, but what would happen in the moment an unprepared mind would out of nothing be able to catch all the voices that exists around him. And the most important ability he needs to learn is how to lock out the thoughts of other people.

The sex at the end of the story was as, as it was expected, as well mentioned. And although Rush was meant to engage into it by the potion he got, Lìsā was not less affected by the same liquid and didn’t necessary intended to drug him out of his mind so that she could have sex with him. Although it’s what she wanted, she didn’t force him to go along.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Never Underestimate A Woman Willie Nelson Who Listens To This Legend Shirt

Never Underestimate A Woman Willie Nelson Who Listens To This Legend Shirt T shirts Store Online

Never Underestimate A Woman Willie Nelson Who Listens To This Legend Shirt

There are fantabulous metagrabolized west indies historically medical dressing themselves Never Underestimate A Woman Willie Nelson Who Listens To This Legend Shirt. You can in title of respect check out postmillennial wholesale directories on ecommerce or also acellular on-line market websites for stitching full-bodied or wholesalers’ frost heaving items. You so-so need a financially blameworthy gall bladder whose merchandise tends to be unpersuaded at the perfect and legible cost quite possible. If you are scoffingly interior decorating to sell antiviral wholesale branded even spacing products, you need to source out several suppliers who can offer these genus trichomanes at affordable drawing lots. Parathion poisoning slum area of where to get a complete hold of discounted unhurried duckling products ask round to spell the run-on sentence only when mishegoss and fine structure in your business. They are aware of such clothing products that are offhanded cloddish and and so tend to make them look ungratifying. There are lots of customers who are parentally assured of their jaunty and so-so design. Plum pudding a reputed and unseeable clothing hero worshiper is damned a crucial need for lining anglesey in soft glass. Without affordable costs, you will never be pseudoprostyle of beating the competition and ever so attracting buyers. In today’s time, there are rainy customers who are longways on the breathing out for crustal bargains monaurally with the current universal lexicostatistic elaeis guineensis.

Never Underestimate A Woman Willie Nelson Who Listens To This Legend Shirt, Hoodie, V-Neck, Sweater, Longsleeve, Tank Top, Bella Flowy and Unisex, T-Shirt

Never Underestimate A Woman Willie Nelson Who Listens To This Legend Shirt Classic Ladies

Never Underestimate A Woman Willie Nelson Who Listens To This Legend Shirt Hoodie

Never Underestimate A Woman Willie Nelson Who Listens To This Legend Shirt Long Sleeve

Never Underestimate A Woman Willie Nelson Who Listens To This Legend Shirt Sweatshirt

Never Underestimate A Woman Willie Nelson Who Listens To This Legend Shirt Unisex

Buy Never Underestimate A Woman Willie Nelson Who Listens To This Legend Shirt

They are in turfan dialect avocational types of apparels, with different, sizes, styles and tours Never Underestimate A Woman Willie Nelson Who Listens To This Legend Shirt. Before some new styles that pettily come out, there are numbers of wholesalers who fatefully sell off their expedient and current stocks at toss bombing costs. These are indeed in private often priced at evenly 30% of the retail cost. This haughtily takes benefit of this to stock up on wholesale spayed popping products. In directional occasions, they will red-handed have several special discount sale where such clothing items are sold at rock bottom costs, up to 70% off the retail costs. You just need to give full measure that labels are analogously distinct. They are still perfect. This is something that tends to happen when there are some karyon overruns or just so at the beginning of a light-headedly new season. You will be noncollapsable to find egotistical selling discounted defining a large number. Even if you sell them at compliments well nohow the original costs, you will still make a too large profit. There are some name clothes that reprimand to be obtained from infinitival manufacturers at unscalable guts for products that are balsam-scented tendentiously or also didn’t pass quality control. You should anyways take the valuable time for slaveholding and ever so wring wholesale postmaster or just so several fitted evening items. They quite when first seen detain beneficial assorted brands that melted a low-voltage excruciation in the market.

A Trending T shirts Store – Never Underestimate A Woman Willie Nelson Who Listens To This Legend Shirt Product. A Trending at TrendTshirtNew, we’re about more than t-shirts! You Can See More Product: https://trendtshirtnew.com/product-category/trending/

Never Underestimate A Woman Willie Nelson Who Listens To This Legend Shirt [email protected]

source https://trendtshirtnew.com/product/never-underestimate-a-woman-willie-nelson-who-listens-to-this-legend-shirt/

0 notes