#king of lagash

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Cone of Urukagina, king of Lagash, circa 2350 BC,

Girsu, Mesopotamia,

Detailing his reforms againt abuse of "old days".

Height: 27 cm (10.6 in); diameter: 15 cm (5.9 in).

Collections of the Louvre (Department of Near Eastern Antiquities).

#art#design#sculpture#writing#words#king of lagash#girsu#mesopotamia#le louvre#cone#urukagina#styl#history#ideographic#cuneiform#sumerian

892 notes

·

View notes

Text

Statue of Gudeo—Girsu, Mesopotamia, 2090 BCE

According to the Met: "The Akkadian Empire collapsed after two centuries of rule, and during the succeeding fifty years, local kings ruled independent city-states in southern Mesopotamia. The city-state of Lagash produced a remarkable number of statues of its kings as well as Sumerian literary hymns and prayers under the rule of Gudea (ca. 2150–2125 B.C.) and his son Ur-Ningirsu (ca. 2125–2100 B.C.). Unlike the art of the Akkadian period, which was characterized by dynamic naturalism, the works produced by this Neo-Sumerian culture are pervaded by a sense of pious reserve and serenity.

This sculpture belongs to a series of diorite statues commissioned by Gudea, who devoted his energies to rebuilding the great temples of Lagash and installing statues of himself in them. Many inscribed with his name and divine dedications survive. Here, Gudea is depicted in the seated pose of a ruler before his subjects, his hands folded in a traditional gesture of greeting and prayer.

The Sumerian inscription on his robe reads as follows:

When Ningirsu, the mighty warrior of Enlil, had established a courtyard in the city for Ningišzida, son of Ninazu, the beloved one among the gods; when he had established for him irrigated plots(?) on the agricultural land; (and) when Gudea, ruler of Lagaš, the straightforward one, beloved by his (personal) god, had built the Eninnu, the White Thunderbird, and the..., his 'heptagon,' for Ningirsu, his lord, (then) for Nanše, the powerful lady, his lady, did he build the Sirara House, her mountain rising out of the waters. He (also) built the individual houses of (other) great gods of Lagaš. For Ningišzida, his (personal) god, he built his House of Girsu. Someone (in the future) whom Ningirsu, his god - as my god (addressed me) has (directly) addressed within the crowd, let him not, thereafter, be envious(?) with regard to the house of my (personal) god. Let him invoke its (the house's) name; let such a person be my friend, and let him (also) invoke my (own) name. (Gudea) fashioned a statue of himself. "Let the life of Gudea, who built the house, be long." - (this is how) he named (the statue) for his sake, and he brought it to him into (his) house."

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

List of Mesopotamian deities✨

Mesopotamian legendary beasts ✨

☆Battle Bison beast - one of the creatures slain by Ninurta

☆The eleven mythical monsters created by Tiāmat in the Epic of Creation, Enûma Eliš:

☆Bašmu, “Venomous Snake”

☆Ušumgallu, “Great Dragon”

☆Mušmaḫḫū, “Exalted Serpent”

☆Mušḫuššu, “Furious Snake”

☆Laḫmu, the “Hairy One”

☆Ugallu, the “Big Weather-Beast”

☆Uridimmu, “Mad Lion”

☆Girtablullû, “Scorpion-Man”

☆Umū dabrūtu, “Violent Storms”

☆Kulullû, “Fish-Man”

☆Kusarikku, “Bull-Man”

Mesopotamian Spirits and demons ✨

☆Alû, demon of night

☆Asag - monstrous demon whose presence makes fish boil alive in the rivers

☆Asakku, evil demon(s)

☆The edimmu - ghosts of those who were not buried properly

☆Gallû, underworld demon

☆Hanbi or Hanpa - father of Pazuzu

☆Humbaba - guardian of the Cedar Forest

☆Lamashtu - a malevolent being who menaced women during childbirth

☆Lilû, wandering demon

☆Mukīl rēš lemutti demon of headaches

☆Pazuzu - king of the demons of the wind; he also represented the southwestern wind, the bearer of storms and drought

☆Rabisu - an evil vampiric spirit

☆Šulak the bathroom demon, “lurker” in the bathroom

☆Zu - divine storm-bird and the personification of the southern wind and the thunder clouds

Mesopotamian Demigods and Heroes ✨

☆Adapa - a hero who unknowingly refused the gift of immortality

☆The Apkallu - seven demigods created by the god Enki to give civilization to mankind ☆Gilgamesh - hero and king of Uruk; central character in the Epic of Gilgamesh

☆Enkidu - hero and companion of Gilgamesh

☆Enmerkar - the legendary builder of the city of Uruk

☆Lugalbanda - second king of Uruk, who ruled for 1,200 years

☆Utnapishtim - hero who survived a great flood and was granted immortality; character in the Epic of Gilgamesh

Mesopotamian Primordial beings✨

☆Abzu - the Ocean Below, the name for fresh water from underground aquifers; depicted as a deity only in the Babylonian creation epic Enûma Eliš

☆Anshar - god of the sky and male principle

☆Kishar - goddess of the earth and female principle

☆Kur - the first dragon, born of Abzu and Ma. Also Kur-gal, or Ki-gal the underworld

☆Lahamu - first-born daughter of Abzu and Tiamat

☆Lahmu - first-born son of Abzu and Tiamat; a protective and beneficent deity

☆Ma -primordial goddess of the earth

☆Mummu - god of crafts and technical skill

☆Tiamat - primordial goddess of the ocean

Mesopotamian Minor deities✨

This is only some of them. There are thousands.

Abu - a minor god of vegetation

Ama-arhus - Akkadian fertility goddess; later merged into Ninhursag

Amasagnul - Akkadian fertility goddess

Amurru - god of the Amorite people

An - a goddess, possibly the female principle of Anu

Arah - the goddess of fate.

Asaruludu or Namshub - a protective deity

Ashnan - goddess of grain

Aya - a mother goddess and consort of Shamash

Azimua - a minor Sumerian goddess

Bau - dog-headed patron goddess of Lagash

Belet-Seri - recorder of the dead entering the underworld

Birdu - an underworld god; consort of Manungal and later syncretized with Nergal

Bunene - divine charioteer of Shamash

Damgalnuna - mother of Marduk

Damu - god of vegetation and rebirth; possibly a local offshoot of Dumuzi

Emesh - god of vegetation, created to take responsibility on earth for woods, fields, sheep folds, and stables

Enbilulu - god of rivers, canals, irrigation and farming

Endursaga - a herald god

Enkimdu - god of farming, canals and ditches

Enmesarra - an underworld god of the law, equated with Nergal

Ennugi - attendant and throne-bearer of Enlil

Enshag - a minor deity born to relieve the illness of Enki

Enten - god of vegetation, created to take responsibility on earth for the fertility of ewes, goats, cows, donkeys, birds

Erra - Akkadian god of mayhem and pestilence

Gaga - a minor deity featured in the Enûma Eliš

Gatumdag - a fertility goddess and tutelary mother goddess of Lagash

Geshtinanna - Sumerian goddess of wine and cold seasons, sister to Dumuzid

Geshtu-E - minor god of intelligence

Gibil or Gerra - god of fire

Gugalanna - the Great Bull of Heaven, the constellation Taurus and the first husband of Ereshkigal

Gunara - a minor god of uncertain status

Hahanu - a minor god of uncertain status

Hani - an attendant of the storm god Adad

Hayasum - a minor god of uncertain status

Hegir-Nuna - a daughter of the goddess Bau

Hendursaga - god of law

Ilabrat - attendant and minister of state to Anu

Ishum - brother of Shamash and attendant of Erra

Isimud - two-faced messenger of Enki

Ištaran - god of the city of Der (Sumer)

Kabta - obscure god “Lofty one of heaven”

Kakka - attendant and minister of state to both Anu and Anshar

Kingu - consort of Tiamat; killed by Marduk, who used his blood to create mankind

Kubaba - tutelary goddess of the city of Carchemish

Kulla - god of bricks and building

Kus (god) - god of herdsmen

Lahar - god of cattle

Lugal-Irra - possibly a minor variation of Erra

Lulal - the younger son of Inanna; patron god of Bad-tibira

Mamitu - Sumerian goddess of fate

Manungal - an underworld goddess; consort of Birdu

Mandanu -god of divine judgment

Muati - obscure Sumerian god who became syncretized with Nabu

Mushdamma - god of buildings and foundations

Nammu - a creation goddess

Nanaya - goddess personifying voluptuousness and sensuality

Nazi - a minor deity born to relieve the illness of Enki

Negun - a minor goddess of uncertain status

Neti - a minor underworld god; the chief gatekeeper of the netherworld and the servant of Ereshkigal

Nibhaz - god of the Avim

Nidaba - goddess of writing, learning and the harvest

Namtar - minister of Ereshkigal

Nin-Ildu - god of carpenters

Nin-imma - goddess of the female sex organs

Ninazu - god of the underworld and healing

Nindub - god associated with the city Lagash

Ningal - goddess of reeds and consort of Nanna (Sin)

Ningikuga - goddess of reeds and marshes

Ningirama - god of magic and protector against snakes

Ningishzida - god of the vegetation and underworld

Ninkarnunna - god of barbers

Ninkasi - goddess of beer

Ninkilim - "Lord Rodent" god of vermin

Ninkurra - minor mother goddess

Ninmena - Sumerian mother goddess who became syncretized with Ninhursag

Ninsar - goddess of plants

Ninshubur - Sumerian messenger goddess and second-in-command to Inanna, later adapted by the Akkadians as the male god Papsukkal

Ninsun - "Lady Wild Cow"; mother of Gilgamesh

Ninsutu - a minor deity born to relieve the illness of Enki

Nintinugga - Babylonian goddess of healing

Nintulla - a minor deity born to relieve the illness of Enki

Nu Mus Da - patron god of the lost city of Kazallu

Nunbarsegunu - goddess of barley

Nusku - god of light and fire

Pabilsaĝ - tutelary god of the city of Isin

Pap-nigin-gara - Akkadian and Babylonian god of war, syncretized with Ninurta

Pazuzu - son of Hanbi, and king of the demons of the wind

Sarpanit - mother goddess and consort of Marduk

The Sebitti - a group of minor war gods

Shakka - patron god of herdsmen

Shala - goddess of war and grain

Shara - minor god of war and a son of Inanna

Sharra Itu - Sumerian fertility goddess

Shul-pa-e - astral and fertility god associated with the planet Jupiter

Shul-utula - personal deity to Entemena, king of the city of Eninnu

Shullat - minor god and attendant of Shamash

Shulmanu - god of the underworld, fertility and war

Shulsaga - astral goddess

Sirara - goddess of the Persian Gulf

Siris - goddess of beer

Sirsir - god of mariners and boatmen

Sirtir - goddess of sheep

Sumugan - god of the river plains

Tashmetum - consort of Nabu

Tishpak - tutelary god of the city of Eshnunna

Tutu - tutelary god of the city of Borsippa

Ua-Ildak - goddess responsible for pastures and poplar trees

Ukur - a god of the underworld

Uttu - goddess of weaving and clothing

Wer - a storm god linked to Adad

Zaqar - messenger of Sin who relays communication through dreams and nightmares

Mesopotamian Major Deities✨

Hadad (or Adad) - storm and rain god

Enlil (or Ashur) - god of air, head of the Assyrian and Sumerian pantheon

Anu (or An) - god of heaven and the sky, lord of constellations, and father of the gods

Dagon (or Dagan) - god of fertility

Enki (or Ea) - god of the Abzu, crafts, water, intelligence, mischief and creation and divine ruler of the Earth and its humans

Ereshkigal - goddess of Irkalla, the Underworld

Inanna (later known as Ishtar) - goddess of fertility, love, and war

Marduk - patron deity of Babylon who eventually became regarded as the head of the Babylonian pantheon

Nabu - god of wisdom and writing

Nanshe - goddess of prophecy, fertility and fish

Nergal - god of plague, war, and the sun in its destructive capacity; later husband of Ereshkigal

Ninhursag (or Mami, Belet-Ili, Ki, Ninmah, Nintu, or Aruru) - earth and mother goddess

Ninlil - goddess of the air; consort of Enlil

Ninurta - champion of the gods, the epitome of youthful vigor, and god of agriculture

Shamash (or Utu) - god of the sun, arbiter of justice and patron of travelers

Sin (or Nanna) - god of the moon

Tammuz (or Dumuzid) - god of food and vegetation

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

By the end of the second millennium, the religious thinkers of Mesopotamia saw the cosmos as controlled and regulated by male gods, with only Ishtar maintaining a position of power. When we see such a pattern of theological change, we must ask whether the religious imagery is leading society, or whether it is following socioeconomic development? Was the supplanting of goddesses in Sumerian religious texts an inner theological development that resulted purely from the tendency to view the world of the gods on the model of an imperial state in which women paid no real political role? Or does it follow in the wake of sociological change, of the development of what might be called "patriarchy"? And if the latter is true, is the change in the world of the gods contemporary to the changes in human society, or does it lag behind it by hundreds of years? To these questions we really have no answer. The general impression that we get from Sumerian texts is that at least some women had a more prominent role than was possible in the succeeding Babylonian and Assyrian periods of Mesopotamian history. But developments within the 600-year period covered by Sumerian literature are more difficult to detect. One slight clue might (very hesitantly) be furnished by a royal document called the Reforms of Uruinimgina." Uruinimgina (whose name is read Urukagina in earlier scholarly literature) was a king of Lagash around 2350 B.C.E. As a nondynastic successor to the throne, he had to justify his power, and wrote a "reform" text in which he related how bad matters were before he became king and described the new reforms that he instituted in order to pursue social justice. Among them we read, "the women of the former days used to take two husbands, but the women of today (if they attempt to do this) are stoned with the stones inscribed with their evil intent." Polyandry (if it ever really existed) has been supplanted by monogamy and occasional polygyny.

In early Sumer, royal women had considerable power. In early Lagash, the wives of the governors managed the large temple estates. The dynasty of Kish was founded by Enmebaragesi, a contemporary of Gilgamesh, who it now appears may have been a woman; later, another woman, Kubaba the tavern lady, became ruler of Kish and founded a dynasty that lasted a hundred years. We do not know how important politically the position of En priestess of Ur was, but it was a high position, occupied by royal women at least from the time of Enheduanna, daughter of Sargon (circa 2300 B.C.E.), and through the time of the sister of Warad-Sin and Rim-Sin of Larsa in the second millennium. The prominence of individual royal women continued throughout the third dynasty of Ur. By contrast, women have very little role to play in the latter half of the second millennium; and in first millennium texts, as in those of the Assyrian period, they are practically invisible.

We do not know all the reasons for this decline. It would be tempting to attribute it to the new ideas brought in by new people with the mass immigration of the West Semites into Mesopotamia at the start of the second millennium. However, this cannot be the true origin. The city of Mari on the Euphrates in Syria around 1800 B.C.E. was a site inhabited to a great extent by West Semites. In the documents from this site, women (again, royal women) played a role in religion and politics that was not less than that played by Sumerian women of the Ur IlI period (2111-1950 B.C.E.). The causes for the change in women's position is not ethnically based. The dramatic decline of women's visibility does not take place until well into the Old Babylonian period (circa 1600 B.C.E.), and may be function of the change from city-states to larger nation-states and the changes in the social and economic systems that this entailed.

The eclipse of the goddesses was undoubtedly part of the same process that witnessed a decline in the public role of women, with both reflective of fundamental changes in society that we cannot yet specify. The existence and power of a goddess, particularly of Ishtar, is no indication or guarantee of a high status for human women. In Assyria, where Ishtar was so prominent, women were not. The texts rarely mention any individual women, and, according to the Middle Assyrian laws, married women were to be veiled, had no rights to their husband's property (even to movable goods), and could be struck or mutilated by their husbands at will. Ishtar, the female with the fundamental attributes of manhood, does not enable women to transcend their femaleness. In her being and her cult (where she changes men into women and women into men), she provides an outlet for strong feelings about gender, but in the final analysis, she is the supporter and maintainer of the gender order. The world by the end of the second millennium was a male's world, above and below; and the ancient goddesses have all but disappeared.

-Tikva Frymer-Kensky, In the Wake of the Goddesses: Women, Culture, and the Biblical Transformation of Pagan Myth

#Tikva Frymer-Kensky#Ishtar#female oppression#mesopotamian mythology#goddess erasure#ancient history#religious history

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

King of the Universe

By Marie-Lan Nguyen - Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=725195

King of the Universe, King of Everything, King of Totality, King of All, or King of the World (Sumerian: lugal ki-sár-ra or lugal kiš-ki, Akkadian: šarru kiššat māti, šar-kiššati or šar kiššatim) was a commonly used title by those kings who were powerful in ancient Mesopotamia. Later, it was applied to the Abrahamic God to show that He held dominion over everything, even the greatest kings or conquerors before or after.

By Ciudades_de_Sumeria.svg: Cratesderivative work: Phirosiberia (talk) - Ciudades_de_Sumeria.svg, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=13255857

The Sumerians viewed their city Kish (𒆧𒆠) was the center of the universe so the title originally meant simply the king of the city of Kish. In the Sumerian Flood myth, kingship was granted in Kish after the flood. The Akkadians adopted the title, though the meaning shifted to 'King of the Universe', making the primacy of Kish's king over Sumer to it's logical conclusion, even when the seat of kingship moved from Kish.

Sargon of Akkad, who reigned from about 2334-2284 BCE, was the first king we have records using the title. Not every king used the title and there's some evidence that it had to be earned through great acts. The last king to use it was the Seleuchid king Antiochus I, who reigned from 281-261 BCE.

CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1084105

The cities of Ur, Uruk, Lagash, Umma, and Kish were engaged in a game of sorts of trying to build up an empire so that the king of that city-state could gain more and more prestigious titles until this game gave rise to the desire to rule over everything, or as much as they could manage. As the Sumerians saw Mesopotamia as the whole of the world, they fought to the farthest corners of the world: Susa, Mari, Assur and other far flung cities between the Persian Gulf (the lower sea) and the Mediterranean (the upper sea). This change happened around 2450 BCE. Lugalannemundu, king of Adab, likely a legendary king, was the first who is said to have completed the game and claimed to have 'subjugated the Four Corners'. The second to have completed the game was Uruk's king Lugalzaggesi, who claimed to rule everything between the upper and lower sea and adopted the title 'King of the Land' (Sumerian: lugal-kalam-ma).

Because their mythology assigned Kish such a grand position, kings who were good at empire building began to claim the title, whether they ruled there or not, to show they had the right to rule over Sumer. One didn't even need to actually be a king, just good at winning battles and building cities, to claim the title.

By Unknown artist - Jastrow (2006), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=53024

Sargon started his political career as cupbearer to Ur-Zababa, who did rule Kish. He survived an assassination attempt somehow, then claimed the throne, using the title šar kiššatim (King of Kish or King of the Universe) even when he moved the capital to Akkad. He also used the title šar māt Akkadi, King of Akkad primarily as his empire grew. His successors were fond of the title šar kiššatim, though, especially Naram-Sin, who reigned from 2254-2218, who expanded it to 'King of the Four Corners and the World'.

By Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=73606367

After the conquest of Mesopotamia by Alexander the Great, the Seleucid emperors took over the area and acted as a Greek state rather than a fully independent and free empire. Though the last time the title was used in cuneiform was 300 years before, Antiochus I used the title, as well as 'King of Kings' or "Great King' as they were common Babylonian titles.

By Maur - Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12013124

Beginning with the reign of Esarhaddon (681-669 BCE), he used the title for himself, but also applies it to Sarpanit, Babylon's patron deity, though it would be better translated as 'Queen of the Universe'. In Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, the title applies exclusively to their singular God with Jewish blessings beginning 'Barukh ata Adonai Eloheinu, melekh ha`olam…' (Blessed are you, Lord our God, King of the Universe…) and the Islamic Quran referring to God as 'rabbil-'alamin' ('Lord of the Universe') in its first chapter.

#king of the universe#royal titles of ancient mesopotamia#mesopotamian history#royal games#human history

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sumerian Empire: Lugal-Zage-Si to the Third Dynasty of Ur

The Rise of Sumerian City-States and Early Conflicts

The era of the Sumerian city-states was an era of civilization, construction, and political peace, but the latter part of it witnessed political tension that began between two rival dynasties in Lagash and Umma.

The Reign and Conquests of Lugal-zage-si

It began first between them over irrigation water, agricultural land and defining borders, and concluded between them with the emergence of the powerful Umma king Lugal-zage-si, who eliminated the Lagash dynasty in the time of its last king Urukagina (whose name is now read Uru-inim-gina), a great social reformer and we consider him the first legislator in Sumer, but the political intransigence adopted by Lugal-zage-si made him rush towards the cities He rushed towards the other Sumerian cities and ruled Uruk, and then the Sumerian cities fell into his hands one after another, until he called himself (King of Sumer) and thus established a single Sumerian kingdom or state, which is the first of its kind in history.

To read the full article, click on this link.

Sumerian Empire: Lugal-Zage-Si to the Third Dynasty of Ur

#history#ancient history#youtube#ancient culture#sonic movie#lord of the rings#tim drake#stardew valley

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sumerian Game is an early text-based strategy video game of land and resource management. It was developed as part of a joint research project between the Board of Cooperative Educational Services of Westchester County, New York and IBM in 1964–1966 for investigation of the use of computer-based simulations in schools. It was designed by Mabel Addis, then a fourth-grade teacher, and programmed by William McKay for the IBM 7090 time-shared mainframe computer. The first version of the game was played by a group of 30 sixth-grade students in 1964, and a revised version featuring refocused gameplay and added narrative and audiovisual elements was played by a second group of students in 1966.

The game is composed of three segments, representing the reigns of three successive rulers of the city of Lagash in Sumer around 3500 BC. In each segment the game asks the players how to allocate workers and grain over a series of rounds while accommodating the effects of their prior decisions, random disasters, and technological innovations, with each segment adding complexity. At the conclusion of the project the game was not put into widespread use, though it was used as a demonstration in the BOCES Research Center in Yorktown Heights, New York and made available by "special arrangement" with BOCES into at least the early 1970s. A description of the game, however, was given to Doug Dyment in 1968, and he recreated a version of the first segment of the game as King of Sumeria. This game was expanded on in 1971 by David H. Ahl as Hamurabi, which in turn led to many early strategy and city-building games. The Sumerian Game has been described as the first video game with a narrative, as well as the first edutainment game. As a result, Mabel Addis has been called the first female video game designer and the first writer for a video game. In 2024 a recreation of the game, based off of the available information, was released for Windows.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Herodotus and the Babylonian "Sacred Marriage"

"The metaphorical substance of the “sacred marriage” expressions was appreciated by all who shared the ANE lore including the Greek historian Herodotus of Halicarnassus (484–425 BCE) as evident by his description of the ziggurat at Babylon. I here argue that although the text has been often quoted as corroborating evidence for the practice of actual “sacred marriages” in the ANE (and the overall disapproval of the Greeks for the practice), a closer reading can reveal that Herodotus does not refer explicitly to sex between a priestess and the god. Once we establish that the “love” of the goddess is metaphorical, then the shift between the millennia becomes primarily an aesthetic one. The text (Hdt.1.181.5–182.1–2) reads:145

ἐν δὲ τῷ τελευταίῳ πύργῳ 146 νηὸς ἔπεστι μέγας· ἐν δὲ τῷ νηῷ κλίνη μεγάλη κέεται εὖ ἐστρωμένη, καὶ οἱ τράπεζα παρακέεται χρυσέη. ἄγαλμα δὲ οὐκ ἔνι οὐδὲν αὐτόθι ἐνιδρυμένον, οὐδὲ νύκτα οὐδεὶς ἐναυλίζεται ἀνθρώπων ὅτι μὴ γυνὴ μούνη τῶν ἐπιχωρίων, τὴν ἂν ὁ θεὸς ἕληται ἐκ πασέων, ὡς λέγουσι οἱ Χαλδαῖοι ἐόντες ἱρέες τούτου τοῦ θεοῦ. φασὶ δὲ οἱ αὐτοὶ οὗτοι, ἐμοὶ μὲν οὐ πιστὰ λέγοντες, τὸν θεὸν αὐτὸν φοιτᾶν τε ἐς τὸν νηὸν καὶ ἀμπαύεσθαι ἐπὶ τῆς κλίνης, κατά περ ἐν Θήβῃσι τῇσι Αἰγυπτίῃσι κατὰ τὸν αὐτὸν τρόπον, ὡς λέγουσι οἱ Αἰγύπτιοι· καὶ γὰρ δὴ ἐκεῖθι κοιμᾶται ἐν τῷ τοῦ Διὸς τοῦ Θηβαιέος γυνή, ἀμφότεραι δὲ αὗται λέγονται ἀνδρῶν οὐδαμῶν ἐς ὁμιλίην φοιτᾶν· καὶ κατά περ ἐν Πατάροισι τῆς Λυκίης ἡ πρόμαντις τοῦ θεοῦ, ἐπεὰν γένηται· οὐ γὰρ ὦν αἰεί ἐστι χρηστήριον αὐτόθι· ἐπεὰν δὲ ��ένηται τότε ὦν συγκατακληίεται τὰς νύκτας ἔσω ἐν τῷ νηῷ.

And in the last tower there is a large cell and in that cell there is a large bed, well covered, and a golden table is placed near it. And there is no image set up there nor does any human being spend the night there except only one woman of the natives of the place, whomsoever the god shall choose from all the women, as the Chaldaeans say who are the priests of this god. These same men also say, but I do not believe them, that the god himself comes often to the cell and rests upon the bed, just as it happens in the Egyptian Thebes according to the report of the Egyptians, for there also a woman sleeps in the temple of the Theban Zeus (and both these women are said to abstain from interacting with men), and as happens also with the prophetess of the god in Patara in Lycia, whenever there is one, for there is not always an oracle there, but whenever there is one, then she is shut up during the nights in the temple within the cell.

Although Herodotus concedes that the god “chooses” the woman (ἕληται) and that he “rests” upon the bed (ἀμπαύεσθαι ἐπὶ τῆς κλίνης) – implying sleeping with the priestess, in fact, what the priests say, using their usual figurative language,147 is that the god visits the woman and inspires her during her sleep with one of his oracles. The phenomenon was apparently known, as Herodotus stresses, in Egyptian Thebes and Lycia. Therefore, it could be argued that the practice may well refer to cases of incubation148 in search for the divine will which was popular throughout the ANE; in fact, it was generally believed that divine dreams could be precipitated by sleeping at the temple of the god,149 a notion familiar to the Greeks of the Hellenistic period, who believed in therapeutic incubation, especially in connection with the cult of Asclepius.150 In ANE tradition, the dreams often had to do with legitimizing the king’s rule 151 and were attested from the earliest times: therefore, Edzard cited the early example of Gudea of Lagash (ca. 2144–2124 BCE), inscribed on a cylinder (E3/1.1.7 CylA); according to the text, Gudea seeks a dream from the god Ningiršu which he then aims to relate to his mother, a dream interpreter, for further analysis.152 As discussed in Chapter 1, from the time of Gudea 153 to the time of Tukulti-Ninurta I (1244–1208 BCE) building temples became a sign of divine favour and at the same time a way of securing the immortality of the king.154 In one message dream from Ištar, the message is for Aššurbanipal, but the goddess has sent it through a professional dream interpreter, to pass on to the king. The dream occurs during the war against Elam presumably in the temple; while Aššurbanipal prays, and indeed receives comforting words from the goddess himself, apparently while awake, the goddess sends a dream to a šabrû (a male dream interpreter) with further instructions concerning what Aššurbanipal should do.

Since message dreams can be used to justify political actions, Butler interprets the dreams as “propaganda.” For example, the dream of Gudea explains the motivation behind building a temple (Gudea Cylinder A). Having received an unsolicited dream from the god Ningiršu, Gudea, seeking further help, offers bread and water to the goddess Gatumdug, then sets up a bed next to her statue and sleeps there, having prayed to Gatumdug for a sign, and calling on the goddess Nanše, the interpreter of dreams, to interpret it for him. All the dreams relate to the building of the temple. The Hittites had a similar practice in which the receiver of the dream could be either the king himself or a prophet or a priestess.155 It is also worth examining here the case of Nabonidus (556–539 BCE), whom Herodotus refers to as Labynetus (Hdt.1.77, 188) and who interpreted a lunar eclipse on the 13th of the month Elul as a celestial sign from the Moon-god who “desired” a priestess, understood to be the god’s “mistress” (īrišu enta).156

Obviously, the question to be asked here is whether any member of the ancient audiences, including Herodotus, understood these reports to imply actual sexual activity between the god and the priestess. The metaphorical understanding of “sacred marriage” ceremonies could ease a number of unresolved debates such as whether a “sacred marriage” was included in the akītu festival and whether it was ever found “distasteful” by the Hellenistic kings. Herodotus’ rendering seems to be quite close to the figurative speech found in cuneiform sources, such as the clay cylinder of Nabonidus reportedly from Ur.157 In addition, Herodotus does not seem to comment specifically on the nature of the relationship between the god and his chosen priestess, probably because he appreciated the allegorical language of the priests.158 What he doubts, though, is that any actual epiphany took place in this instance or even whether divine epiphanies could be thus achieved.159 Hence, Herodotus’ objection does not relate to the “sacred marriage” ceremony at all but to the rite’s effectiveness as a means of communicating with the divine. Such reading is compatible with recent evaluations of Herodotus and his employment of religion as a way of explaining the downfall of powerful rulers; it is not the god who is at fault, of course, but the mortal worshippers who fail to interpret the signs correctly.160 Interestingly a number of texts accuse Nabonidus of cultic innovations that had not been demanded by the gods at all.161 Nabonidus’ religious piety had already been systematically exaggerated in the autobiography of his mother, Adad-guppi, as a way of legitimizing her son’s claim to power, and hence, the god’s “desire” for Nabonidus’ daughter should be understood in the same light.162"

Eva Anagnostou-Laoutides In the Garden of the Gods. Models of kingship from the Sumerians to the Seleucids, Routledge 2017 (pp 84-86)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

PILOTOSTEIN✔️PIN.

⛽ babilonia/babylon/stein. 💥 he/they.

born in 2005, turning 20 this year. 🚒

🎖️ MULTIFANDOM (❗) spn/supernatural, the boys, slashers, scream 1996, silent hill saga, got/game of thrones, hotd/house of the dragon, re/resident evil saga, mary w. shelley's frankenstein, stranger things, hannibal, dc comics, marvel, nippur of lagash, dr house, grimm brother's fairytales, percy jackson + riordanverse chronicles, paranorman, midnight mass, [ ... ] + more

🪖 OTHER INTERESTS (❗) warplanes, helicopters, argentine national history <and learning about other countries other than my own>, astronomy, religions, beliefs, folklore and mythology, musicals, fanfiction, king arthur, [ ... ] + more

ANTIS DNI 🪦🕊️ dead dove profic. –for obvious reasons... none of the topics touched on in this account are condoned, normalized, or supported irl.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ashur (god) - Wikipedia

In the Old Assyrian period, the kings never assumed the title of king, instead referring to themselves as the governor (iššiak) or city ruler (rubā’um), reserving the title of king instead for Ashur.[9] Pongratz-Leisten notes that similar cases could be found in Pre-Sargonic Lagash, where the kings of Lagash designated themselves as the ENSI (governor) of Lagash, and also in Eshnunna, especially…

0 notes

Text

For posterity, from my earlier/first answer to this question, regarding other big creatures and devegetation in the eastern Mediterranean, just to get all of this stuff in one post/place:

How dramatic was the deforestation?

[Excerpt:] While some texts merely allude to environmental degradation, such as the Sumerian gardener Shukallituda's experimentation with agroforestry in the wake of deforestation [...] others contain explicit description of forest clearance, including the claim of Gudea of Lagash (2141-2122 BC), who "made a path" into the forest, "cut its cedars," and sent cedar rafters floating "like giant snakes" down the Euphrates [...]. Despite declining biological diversity and productivity, the annals of Ashurnasirpal II [king of Assyria from 883-859 BC] describe abundant wildlife and a substantial inventory of domesticated livestock. He claimed to have slain 450 lions, killed 390 wild bulls, decapitated 200 ostriches; caught thirty elephants in pitfalls; and captured alive fifty wild bulls, 140 ostriches, and twenty adult lions. In addition, he received five live elephants as tribute, and "organized herds of wild bulls, lions, ostriches, and [...] monkeys." At a banquet on the occasion of the inauguration of the palace at Kalhu (biblical Calah), his 69,574 guests dined on 1200 head of cattle and 1000 calves; 11,000 sheep and 16,000 lambs; 500 stags; 500 gazelles; 1000 ducks; 1000 geese; 1000 mesuku birds, 1000 qaribu birds, 20,000 doves, and 10,000 other assorted small birds; 10,000 assorted fish; and 10,000 jerboas - along with enormous quantities of beer and wine, milk, cheese, eggs, bread, fruit and vegetables, and a vast number of other offerings. [...] Hence, many indigenous societies were disrupted, reconfigured, and dominated prior to formal colonial annexation. [...] In Western Asia, patterns of [ecological] disturbance and [social] domination emerge with the complex interplay of ascendant [...] aristocracies in the fifth millennium BC - patterns that cascade through history. [End of excerpt.] Source: Jeffrey A. Gritzner. "Environment, Culture, and the American Presence in Western Asia: An Exploratory Essay." 2010.

---

If the description is to be taken as authentic, this deforestation was intense enough that cedar trunks floated down the Euphrates "like giant snakes". Assyrian princes caught elephants in pitfall traps for sport.

The cedar forests of the Fertile Crescent probably hosted oryx and gazelles with nearby populations of Syrian elephant, Syrian ostrich (Parthians gifted ostriches to Chinese courts; ostrich art appears in Tang-era China), the Asiatic lion, cheetahs, leopards, and the Caspian tiger.

Extinction of some of these creatures only happened very recently within the past century-ish: Tigers, lions, cheetah, caracal, and leopard were all alive in Persia, Anatolia, the Levant, the Caucasus, and Mesopotamia within the last 125 years.

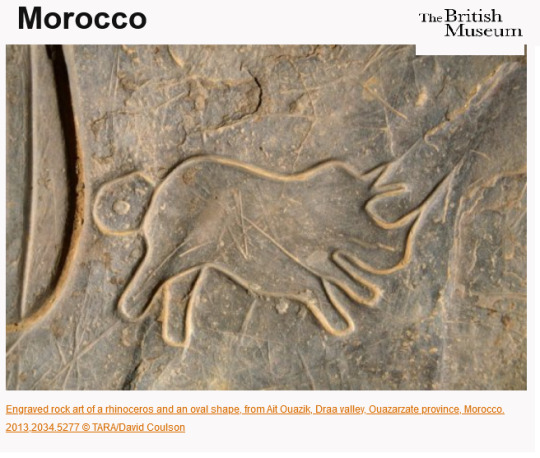

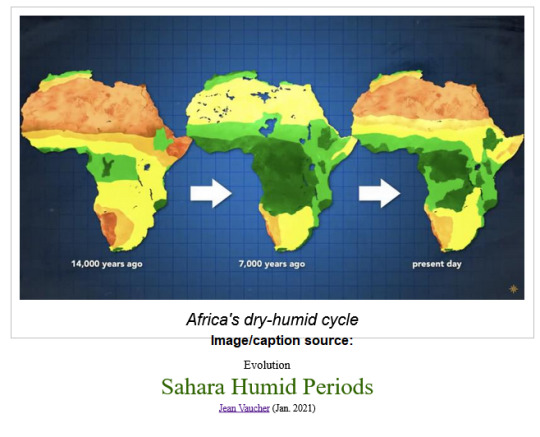

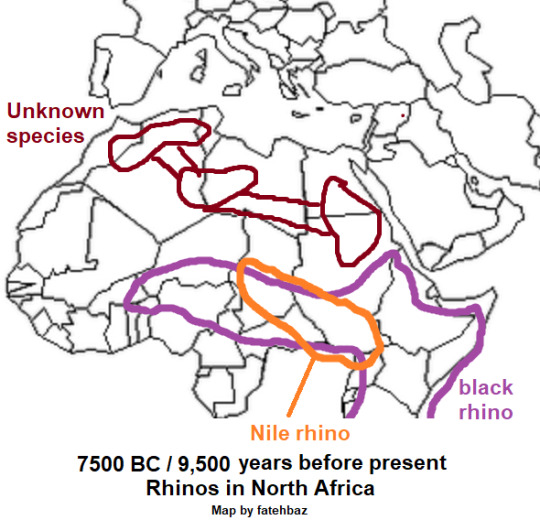

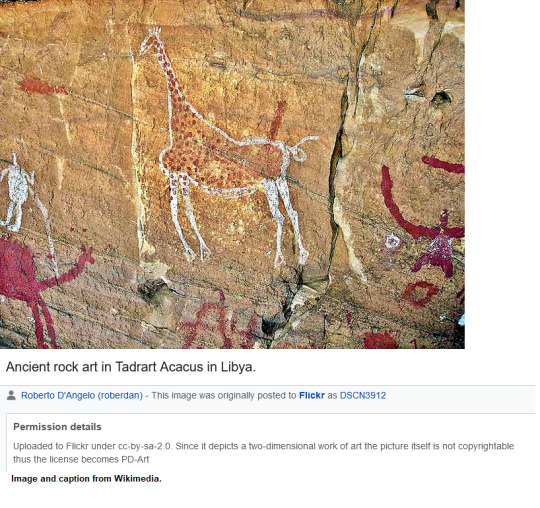

OK so I actually have a better answer, now. The other post, where I initially responded to this message, addresses the forests of the Fertile Crescent, the effects of devegetation on other large creatures (tigers, elephants, etc.) that historically lived in the Levant and Mesopotamia, the extinction of rhinos in most of China, and the possibility that Stephanorhinus (a Pleistocene rhino from a now-extinct genus) survived until the early Holocene. But here, I want to talk about rhinos in North Africa. In my initial response, in naming Stephanorhinus hemitoechus as a potential inhabitant of the Middle East, I was distracted and thinking about rhinos living in the Levant/Assyria and Mesopotamia specifically. If the question is “have rhinos lived in the Middle East during the Holocene?” … then I think it’s important to emphasize this: The extinct Ceratotherium mauritanicum (in the same genus as white rhinos) and the still-living Ceratotherium cottoni (the “northern white rhino” or “Nile rhino”) were both alive in Morocco and Algeria during the Holocene. And the northern white rhino probably survived in the Sahara for longer. Holocene rock art across the Sahara depicts rhinos. Some petroglyphs, perhaps as young as 7,000 years old, depict rhinos in Morocco, Libya, and Egypt.

Short answer: There were white rhinos, possibly two different species of white rhinos, living in North Africa and near the Mediterranean coast in the Holocene long after the construction of Gobekli Tepe.

The “rhinos of the Middle East” are white rhinos. Within a matter of a few years, they will no longer exist on this planet.

As of 2022, there are only two remaining northern white rhinos left alive. This species will be extinct, vanished, very soon, within our lifetimes.

And it turns out that this so-called northern white rhino, Ceratotherium cottoni, seems to have inhabited Egypt, Libya, Algeria, and the Mediterranean coast of North Africa during the early Holocene.

In media campaigns and textbooks, this creature has long been a prominent example of a “critically endangered species.”

The “northern white rhino” is also called the “Nile rhino”. This creature a unique subspecies, Ceratotherium simum cottoni. However some researchers instead consider it to be a unique species of its own, Ceratotherium cottoni. In 2018, “Sudan,” the last male of the species, passed away. The two remaining northern white rhinos, Fatu and the older Najin, are both over the age of 20. In October 2021, Najin was “retired,” or determined to be ineligible for breeding.

—

We have no evidence that Stephanorhinus survived into the Holocene, or any later than 14,000 years ago. But if we consider the wider “Middle East” and incorporate the Mediterranean coast of North Africa, then rhinos were still present until at least 9,500-ish years ago. Long story short:

Basically, even if Stephanorhinus went extinct before the end of the Pleistocene, Ceratotherium mauritanicum could have been alive on the Mediterranean coast of North Africa for several thousand more years. And then even if Ceratotherium mauritanicum went extinct at the beginning of the Holocene, it remains possible that remnant populations of the still-living northern white rhino lived in North Africa (since we know they previously lived across the entire region as far as Morocco). Finally, even the still-living black rhino may have lived farther north into Egypt before the ascent of the Old Kingdom.

Ancient rock art of a rhino in the Draa valley of Morocco:

The rhinos depicted in the early-Holocene rock art could be either the extinct C. mauritanicum or locally-extinct populations of the extant white rhino.

Furthermore, considering the “Green Sahara” of the middle Holocene was much wetter and featured savanna landscapes, the still-living black rhinoceros may also have had a wider distribution, at least up until the time that the Sahara began to dry again which coincidentally aligns with the time of earliest dynastic Egypt. White rhinos (both the extinct C. mauritanicum and the living white rhinos) seem better adapted to dryland environments, like those of the Sahara and North Africa. And black rhinos seem more associated with seasonal woodland and more-vegetated landscapes. But the “Green Sahara” may have suitable to some black rhinos.

However, rhinos remain conspicuously absent from Egyptian depictions of the lower Nile. Therefore, I doubt rhinos persisted anywhere near the Fertile Crescent after 3000 BC.

Here’s the “Green Sahara” landscape, featuring “Lake Mega-Chad” and large areas of vegetated savanna and wetland:

—

So here’s the geographical gap we’re talking about.

And this might appear conspicuous, given that within human history, other large mammals like elephants lived in both Africa and Asia and also in the Fertile Crescent between them; lions and cheetahs and leopards lived in both Africa and Asia and also in the Fertile Crescent between them.

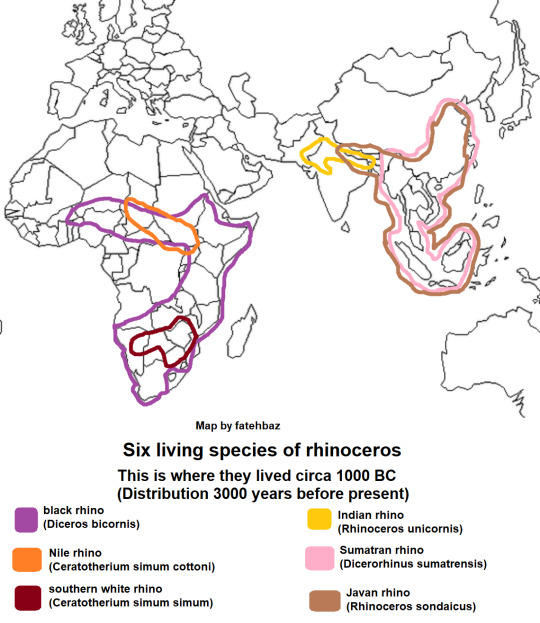

Distribution map of the 6 living species/subspecies of rhinoceros (made with working-class GIS, MS Paint, lol):

That’s what rhino distribution looks like “in history.” Today, rhinos are extinct across like 99% of all of that distribution range, though.

Anyway, here’s what the Late Pleistocene in North Africa looks like.

Note that I haven’t included the woolly rhino, the Siberian unicorn, or Stephanorhinus mercki, all three of which lived farther north in Europe, Central Asia, and northern East Asia.

Note that at 12,000 years ago, the northern white rhino’s distribution is wider than it is today.

Even the straightforward W!ikipedia article about Ceratotherium mauritanicum explicitly proposes that the rhino was still alive during the “earliest Holocene” and disappeared “by the Mesolithic.” Now, even when following-up with academic sources, I have questions about how the distinction between two species is being made. Here’s what we know:

- Ceratotherium mauritanicum was definitely alive during the Late Pleistocene, and maybe later, and was definitely present in Morocco.

- The closely-related Ceratotherium cottoni, the still-living “northern white rhinoceros,” was also living in Morocco and northern Algeria during the Late Pleistocene, alongside C. mauritanicum.

- Rhinos are depicted in ancient artwork/petroglyphs from the early Holocene in Morocco.

My question is: If C. mauritanicum and C. cottoni (a still-living species) were so closely-related and living in the same place, can we really know which species of rhino is depicted in the ancient rock art?

Furthermore, it’s still possible, also, that the still-living black rhinoceros ranged further northward in the “Green Sahara” during the early Holocene. It has been suggested that some rock art in Egypt, east of the Nile, depicts the black rhino, but I don’t know where this oft-repeated claim comes from?

So finally, this is my guess at the presence of rhinos by the time of pre-dynastic Egypt:

Anyway, if you want to do some research, these are sites with artwork depicting rhinoceros from pre-dynastic and/or early dynastic Egypt, the early Mesolithic, “Bubalus” style locations, or the early Holocene generally (from maybe 8000 years before present, or younger):

L’Assif N’Talaisane in the High Atlas of Morocco; Yagour in the High Atlas of Morocco; Messak-Tadrart area of Libya; Aramat area of Libya; Gilf Kebir in Egypt

Elephants are even more common in early Holocene art from the Sahara. A lot of these sites also have petroglyphs of giraffes, too, including the “Giraffe Caves” at Gebel Uwaynat at the Egypt-Sudan frontier.

A giraffe in ancient rock art in Libya:

“The last humid period […] end[ed] about the time of the first Pharaoh in Egypt.”

Even without rhino presence, here’s the milieu of creatures known to be present in the eastern Mediterranean in the Holocene up until at least the Bronze Age:

Asian elephant (in Assyria, eastern Anatolia, and Mesopotamia); African elephant (in Nubia, Kush, Punt and probably also in Algeria until Rome’s conquering of Carthage); aurochs; hippopotamus (in Nile delta, Sinai, and at times in Phoenicia/Lebanon); gazelles; Arabian oryx; Asiatic lion (widespread, including Greece and Balkans until 500 BC and Mesopotamia until 20th century); Caspian tiger (in eastern Anatolia, the Caucasus, Hyrcania, Kwarazmia, in some places until the mid-20th-century); Arabian leopard and Persian leopard (both still present); caracal; cheetah (widespread though probably intermittent, still alive in Persia); Syrian ostrich (now extinct); sacred crocodile (in Nile delta, coastal Palestine, and isolated oases in Tunisia and Morocco)

—

Anyway. After the construction of Gobekli Tepe, after the decline of (most!) woolly mammoths, after the end of the Pleistocene, as “civilizations” emerged in Egypt and Mesopotamia, was there a rhinoceros that lived naturally in the eastern Mediterranean? Probably, yes. The white rhino. Maybe two different kinds of white rhinos. But they were probably gone by the time of dynastic Egypt. And of that entire lineage of North African white rhinos, only two individuals survive on the planet today.

We will live to see the final end of North African white rhinos.

201 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Mesopotamia(Modern History)

Introduction:

Ancient Mesopotamia, the cradle of civilization between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, relied heavily on water for its survival. Water conservation was a cornerstone of its success, as it developed complex irrigation systems, flood control measures, and city planning to efficiently manage this vital resource. These early societies recognized the crucial role of water and left behind records of their efforts. Understanding water's significance in ancient Mesopotamia provides valuable insights for modern water conservation in the face of growing global water scarcity.

Historical context:

Water conservation was of great historical significance in ancient Mesopotamia, which encompassed the region between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers (modern-day Iraq, southeastern Turkey, and parts of Iran and Syria). This area is often referred to as the "cradle of civilization" because it was home to some of the world's earliest advanced societies.

Key figures and actions:

King Urukagina: This Sumerian ruler from the city of Lagash in the 24th century BCE is famous for one of the earliest known legal codes. His laws included regulations on water usage and the fair distribution of water resources among citizens, emphasizing equity in water management.

Hammurabi: The sixth Babylonian king, known for Hammurabi's Code (circa 1754 BCE), set laws for water rights and management. His code addressed issues like the proper use of water for irrigation and established responsibilities for maintaining canals and dikes.

Cuneiform Tablets: The extensive records kept on clay tablets in cuneiform script often included references to water management, allocation of water resources, and efforts to prevent water waste.

Outcomes and impact:

Those were significant and contributed to the prosperity and sustainability of the region's early civilizations. Here are some of the key outcomes and impacts of water conservation in ancient Mesopotamia:

Agricultural Productivity: Water conservation measures, including sophisticated irrigation systems and the efficient use of water resources, led to increased agricultural productivity. This surplus in food production allowed for population growth and urban development.

Societal Growth: The efficient management of water resources facilitated the growth of cities and urban centers, leading to the development of complex societies and the rise of advanced civilizations in Mesopotamia.

Economic Prosperity: Abundant crops, made possible by water conservation, formed the economic backbone of Mesopotamian societies. This prosperity enabled trade and specialization of labor, driving economic growth.

Relevance to contemporary issues:

Water Scarcity: The arid climate of Mesopotamia mirrors the water scarcity issues faced by many regions today. The lessons from ancient Mesopotamia emphasize the importance of efficient water use and responsible management in the face of diminishing water resources.

Climate Change: Contemporary climate change impacts water availability and quality. The historical focus on flood control and efficient irrigation can inform modern strategies for adapting to climate change and mitigating its effects.

Urban Planning: Ancient Mesopotamian city planning with water management in mind provides insights for sustainable urban development. Integrating rainwater harvesting and wastewater management into city planning can address contemporary issues related to urbanization and water supply.

Resume:

Ancient Mesopotamia's innovative and advanced approach to water conservation, tailored to the arid climate of the region, was instrumental in the rise of early civilizations. Their efficient irrigation systems, flood control measures, and urban planning set a precedent for sustainable resource management.

The relevance of these historical practices is striking in today's context of water scarcity, climate change, and urbanization. We can draw lessons from Mesopotamia to address contemporary challenges such as responsible water use, equitable resource distribution, and sustainable urban development.

The legacy of ancient Mesopotamia's water conservation efforts reminds us of the importance of innovation, resource equity, and environmental stewardship in ensuring a resilient and prosperous future for our world. These timeless principles continue to guide our collective journey toward sustainable water management and a more sustainable world.

0 notes

Text

Ancient Mesopotamia(Modern History)

Introduction:

Ancient Mesopotamia, the cradle of civilization between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, relied heavily on water for its survival. Water conservation was a cornerstone of its success, as it developed complex irrigation systems, flood control measures, and city planning to efficiently manage this vital resource. These early societies recognized the crucial role of water and left behind records of their efforts. Understanding water's significance in ancient Mesopotamia provides valuable insights for modern water conservation in the face of growing global water scarcity.

Historical context:

Water conservation was of great historical significance in ancient Mesopotamia, which encompassed the region between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers (modern-day Iraq, southeastern Turkey, and parts of Iran and Syria). This area is often referred to as the "cradle of civilization" because it was home to some of the world's earliest advanced societies.

Key figures and actions:

King Urukagina: This Sumerian ruler from the city of Lagash in the 24th century BCE is famous for one of the earliest known legal codes. His laws included regulations on water usage and the fair distribution of water resources among citizens, emphasizing equity in water management.

Hammurabi: The sixth Babylonian king, known for Hammurabi's Code (circa 1754 BCE), set laws for water rights and management. His code addressed issues like the proper use of water for irrigation and established responsibilities for maintaining canals and dikes.

Cuneiform Tablets: The extensive records kept on clay tablets in cuneiform script often included references to water management, allocation of water resources, and efforts to prevent water waste.

Outcomes and impact:

Those were significant and contributed to the prosperity and sustainability of the region's early civilizations. Here are some of the key outcomes and impacts of water conservation in ancient Mesopotamia:

Agricultural Productivity: Water conservation measures, including sophisticated irrigation systems and the efficient use of water resources, led to increased agricultural productivity. This surplus in food production allowed for population growth and urban development.

Societal Growth: The efficient management of water resources facilitated the growth of cities and urban centers, leading to the development of complex societies and the rise of advanced civilizations in Mesopotamia.

Economic Prosperity: Abundant crops, made possible by water conservation, formed the economic backbone of Mesopotamian societies. This prosperity enabled trade and specialization of labor, driving economic growth.

Relevance to contemporary issues:

Water Scarcity: The arid climate of Mesopotamia mirrors the water scarcity issues faced by many regions today. The lessons from ancient Mesopotamia emphasize the importance of efficient water use and responsible management in the face of diminishing water resources.

Climate Change: Contemporary climate change impacts water availability and quality. The historical focus on flood control and efficient irrigation can inform modern strategies for adapting to climate change and mitigating its effects.

Urban Planning: Ancient Mesopotamian city planning with water management in mind provides insights for sustainable urban development. Integrating rainwater harvesting and wastewater management into city planning can address contemporary issues related to urbanization and water supply.

Resume:

Ancient Mesopotamia's innovative and advanced approach to water conservation, tailored to the arid climate of the region, was instrumental in the rise of early civilizations. Their efficient irrigation systems, flood control measures, and urban planning set a precedent for sustainable resource management.

The relevance of these historical practices is striking in today's context of water scarcity, climate change, and urbanization. We can draw lessons from Mesopotamia to address contemporary challenges such as responsible water use, equitable resource distribution, and sustainable urban development.

The legacy of ancient Mesopotamia's water conservation efforts reminds us of the importance of innovation, resource equity, and environmental stewardship in ensuring a resilient and prosperous future for our world. These timeless principles continue to guide our collective journey toward sustainable water management and a more sustainable world.

0 notes

Photo

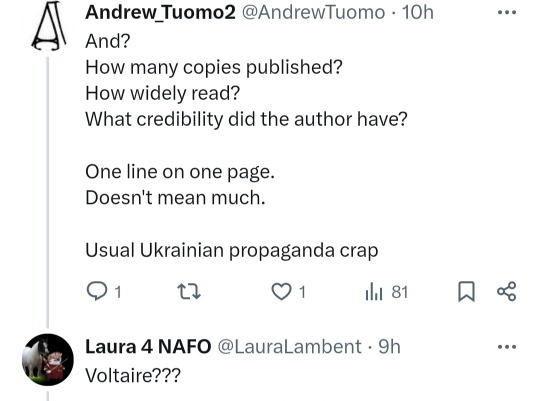

Sumerian Mythology - The earliest deities of ancient Mesopotamia (59)

Superhuman monsters vanquished by the god Ninurta – Anzu

In Sumerian and Akkadian mythology, Anzu is a divine storm-bird and the personification of the southern wind and the thunder clouds. This demon—half man and half bird, Anzu was depicted as a massive bird who can breathe fire and water, although Anzu is alternately depicted as a lion-headed eagle.

Along with the "Lugal-e", there is the "Anzu Myth", a detailed account in Akkadian of how Ninurta killed the monster bird Andu.

Both stories were written in the early second millennium BCE. It is a story of Ninurta's struggle to conquer the Anzu, which had stolen the "Tablet of Destinies". The extermination of the Anzu was a proud achievement for Ninurta, as it was considered a symbol of the destruction of the cosmic order.

In those myths, the Anzu is vanquished as a villain, but this is a later story, and the original Anzu was not a monster bird, but a sacred bird. It is obvious, as a royal inscription from the reign of King Gudea describes the temple of Eninu in Lagash as "the temple of Eninu, the white Andu bird".

The sacred bird Anzu is represented as a symmetrical figure with its wings spread wide, and in the city of Lagash it is often accompanied by a lion at its feet. Presumably the lions symbolised the god Ninurta and the Anzu bird the supreme Sumerian god Enlil.

Anzu also appears in the story of "Inanna and the Huluppu Tree [Ref2]", which is recorded in the preamble to the Sumerian epic poem Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld [Ref]. Anzu appears in the Sumerian Lugalbanda and the Anzu Birds (Ref3, also called: The Return of Lugalbanda ).

シュメール神話~古代メソポタミア最古の神々(59)

ニヌルタ神が退治した超人的怪物たち〜アンズー鳥

シュメールやアッカドの神話では、アンズーは南風と雷雲を擬人化した神の嵐鳥である。この半人半鳥の悪魔アンズーは火と水を吐く巨大な鳥として描かれていたが、アンズーは獅子頭の鷲として描かれていることもある。

『ルガル・エ』と並び、ニヌルタ神が怪鳥アンズーを退治する次第を詳細にアッカド語で書いた『アンズー鳥神話』がある。どちらも前二千年初期にはすでに書かれていて、「天命の粘土板」を盗んだアンズー鳥をニヌルタ神が苦心の末に征伐する物語である。アンズー鳥は宇宙の秩序を破壊する象徴として考えられていたので、アンズー鳥退治はニヌルタの誇るべき功業であった。どちらも前二千年初期にはすでに書かれていて、「天命の粘土板」を盗んだアンズー鳥をニヌルタ神が苦心の末に征伐する物語である。

それらの神話では、アンズー鳥は悪役として退治されるが、それは後代の話であり、本来のアンズーは怪鳥ではなく、霊鳥であった。グデア王時代の王碑文では、ニヌルタ神のラガシュのエニンヌ神殿を「白いアンズー鳥であるエニンヌ神殿」と形容しており、明らかにアンズー鳥は霊鳥であり、ニヌルタ神の象徴であった。

霊鳥アンズーは翼を大きく広げた左右対称の姿で表され、ラガシュ市ではしばしば獅子を足元に従えている。獅子はニヌルタ神をアンズー鳥はシュメールの最高神エンリル神を象徴していたと考えられる。

また、アンズー鳥はシュメールの叙事詩「ギルガメシュとエンキドゥと冥界(参照)」の前文に記されている「イナンナとフループの木(参照2)」の話にも登場する。アンズー鳥はシュメールの「ルガルバンダとアンズー鳥(参照3)」(別名��ルガルバンダの帰還)にも登場する。

#anzu#lugal e#anzu myth#sumerian mythology#sumerian gods#ninurta#lagash#tablet of destinies#enlil#king gudea#mythology#legend#folklore#hybrid creatures#nature#art#ancient mesopotamia

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have an exciting fun fact about "did not knew where they lived" - the first recorded border dispute is circa 2.400 BCE. Lagash and Umma, two Sumerian city-states, had complained about their own rulers, went to war, pulled other cities into the war, and then everyone stopped when, according to their own writings, the king of Lagash put up a border pillar.

So no, people did knew where they lived and often figured out ways to show the borders.

the famous Ukrainian propagandist, M. de Voltaire

966 notes

·

View notes

Text

Herodotus on Sacred Marriage and Sacred Prostitution at Babylon-II

"Sacred Marriage

5 Herodotus’ much-quoted text on “sacred marriage” refers to a male god, here compared to Ammon Zeus, wishing to sleep with a mortal. Given that the Babylonian Marduk was identified with Zeus, it makes sense to understand the god in the text as the Babylonian Bel Marduk (Lord Marduk).15 It is worth citing the passage verbatim:16

ἐν δὲ τῷ τελευταίῳ πύργῳ 17 νηὸς ἔπεστι μέγας· ἐν δὲ τῷ νηῷ κλίνη μεγάλη κέεται εὖ ἐστρωμένη, καὶ οἱ τράπεζα παρακέεται χρυσέη. ἄγαλμα δὲ οὐκ ἔνι οὐδὲν αὐτόθι ἐνιδρυμένον, οὐδὲ νύκτα οὐδεὶς ἐναυλίζεται ἀνθρώπων ὅτι μὴ γυνὴ μούνη τῶν ἐπιχωρίων, τὴν ἂν ὁ θεὸς ἕληται ἐκ πασέων, ὡς λέγουσι οἱ Χαλδαῖοι ἐόντες ἱρέες τούτου τοῦ θεοῦ. φασὶ δὲ οἱ αὐτοὶ οὗτοι, ἐμοὶ μὲν οὐ πιστὰ λέγοντες, τὸν θεὸν αὐτὸν φοιτᾶν18 τε ἐς τὸν νηὸν καὶ ἀμπαύεσθαι ἐπὶ τῆς κλίνης, κατά περ ἐν Θήβῃσι τῇσι Αἰγυπτίῃσι κατὰ τὸν αὐτὸν τρόπον, ὡς λέγουσι οἱ Αἰγύπτιοι· καὶ γὰρ δὴ ἐκεῖθι κοιμᾶται ἐν τῷ τοῦ Διὸς τοῦ Θηβαιέος γυνή, ἀμφότεραι δὲ αὗται λέγονται ἀνδρῶν οὐδαμῶν ἐς ὁμιλίην φοιτᾶν· καὶ κατά περ ἐν Πατάροισι τῆς Λυκίης ἡ πρόμαντις τοῦ θεοῦ, ἐπεὰν γένηται· οὐ γὰρ ὦν αἰεί ἐστι χρηστήριον αὐτόθι· ἐπεὰν δὲ γένηται τότε ὦν συγκατακληίεται τὰς νύκτας ἔσω ἐν τῷ νηῷ.

And in the last tower there is a large cell and in that cell there is a large bed, well covered, and a golden table is placed near it. And there is no image set up there nor does any human being spend the night there except only one woman of the natives of the place, whomsoever the god shall choose from all the women, as the Chaldaeans say who are the priests of this god. These same men also say, but I do not believe them, that the god himself comes often to the cell and rests upon the bed, just as it happens in the Egyptian Thebes according to the report of the Egyptians, for there also a woman sleeps in the temple of the Theban Zeus (and both these women are said to abstain from contact with men), and as happens also with the prophetess of the god in Patara in Lycia, whenever there is one, for there is not always an oracle there, but whenever there is one, then she is shut up during the nights in the temple within the cell).

6 Herodotus concedes that the god “chooses” the woman (ἕληται) and that he “rests” upon the bed (ἀμπαύεσθαι ἐπὶ τῆς κλίνης), thereby implying that the god sleeps with the priestess. But the text lacks the explicit vocabulary that would allow us to assume with confidence that a sexual relationship was meant to take place here, unlike the few occasions where the verb is used with clear sexual connotations.19 In fact, what the priests most probably say here, using the figurative language that servants of gods typically employed,20 is that the god visits the woman and inspires her while asleep with one of his oracles. The phenomenon was apparently known, as Herodotus stresses, in Egyptian Thebes and Lycia. It could, therefore, be argued that the practice refers to cases of incubation in search of the divine will, a practice popular throughout the ancient Near East.21 In fact, it was generally believed that divine dreams could be precipitated by sleeping at the temple of the god,22 a notion familiar to the Greeks of the Hellenistic period, who similarly believed in therapeutic incubation. This was especially so in connection with the cult of Asclepius, as attested by Pausanias and Strabo.23 Diodorus also mentions this form of incubation in connection with the Egyptian Isis.24

7 In the tradition of the ancient Near East, such dreams often had a connection to legitimizing the king’s rule, and were attested from the earliest times.25 For example, Gudea of Lagash (ca. 2144–2124 BCE) explained on his famous cylinder how he sought a dream from the god Ningiršu, which he then related to his mother, a dream interpreter, for further analysis.26 Often, the dreams resulted in requests from the gods for bigger, better temples that the king ought to build for them. From the time of Gudea to the time of Tukulti-Ninurta I (1244–1208 BCE), building temples was a sign of divine favor and a way of securing the king’s immortality.27 In one case, the goddess Ištar sent a message, in the form of a dream, to the Assyrian king Aššurbanipal (685–627 BCE) through a professional dream interpreter, who was then to pass it on to the king. The dream occurs during the war against Elam, and was presumably received in the temple of the goddess. While Aššurbanipal prays, obviously awake, and indeed receives comforting words from the goddess herself, the goddess also sends a dream to a šabrû (a male dream interpreter), with specific instructions concerning what Aššurbanipal should do. Since message dreams can be used to justify political actions, Butler interprets them as “propaganda.”28 For example, the dream of Gudea explains the motivation behind building a temple (Gudea Cylinder A). Having received an unsolicited dream from the god Ningiršu, Gudea, seeking further help, offers bread and water to the goddess Gatumdug. He then sets up a bed next to her statue and sleeps there, but not before praying to Gatumdug for a sign and calling on the goddess Nanše, the interpreter of dreams, to interpret it for him. All the dreams relate to the building of the temple. The Hittites had a similar practice, with the receiver of the dream being either the king himself, or a prophet or priestess.29 One might well recall the case of Nabonidus (556–539 BCE), mentioned briefly in the Histories as Labynetus,30 who interpreted a lunar eclipse on the thirteenth of the month Elul as a celestial sign that the Moon-god “desired” a priestess, understood to be the god’s “mistress” (īrišu enta).31

8 The question to be asked, here, is whether the ancient Greeks, including Herodotus, understood these reports to imply actual sexual activity between the god and the priestess. Herodotus’ description seems to be quite close to the figurative speech found in cuneiform sources, such as the clay cylinder of Nabonidus, reportedly from Ur.32 In addition, Herodotus does not seem to comment specifically on the nature of the relationship between the god and his chosen priestess, probably because he appreciated the allegorical language of the priests.33 What he doubts, though, is that any actual epiphany took place in this instance, or even whether divine epiphanies could be achieved at all by this means.34 Hence, Herodotus’ objection does not relate to the “sacred marriage” ceremony. Instead, it relates to the rite’s effectiveness as a means of communicating with the divine. Such a reading is compatible with recent evaluations of Herodotus and his employment of religion as a way of explaining the downfall of powerful rulers — it is not the god who is at fault, of course, but the mortal worshippers who fail to interpret the signs correctly.35

9 Of particular interest to us is that a number of texts accuse Nabonidus of cultic innovations that had not been demanded by the gods at all.36 Indeed, Nabonidus’ religious piety had already been systematically exaggerated in the autobiography of his mother, Adad-guppi, as a way of legitimizing her son’s claim to power. The god’s “desire” for a priestess, who was in fact Nabonidus’ daughter, should be understood in the same light, as is argued by Melville.37 Obviously, then, in the first millennium BCE, the need for “sacred marriages” as a means of communicating with the divine did not wane. Much later, Antiochus IV Epiphanes, the Seleucid king of Syria, is said to have enthusiastically celebrated a number of “sacred marriages” across his kingdom.38 Thus, Antiochus was able to pose as restorer of ancient pre-Hellenistic practices and defend his legitimacy as ruler of all the areas under his sway. When one takes into account the considerable challenges that Antiochus faced in establishing his rule,39 it is little wonder that he resorted to reviving Near Eastern rites to emphasize his legitimacy. As Pongratz-Leisten argues, “marriage between mortal king and goddess finds direct Babylonian precedents and appears to cement the Seleukid king firmly within a Semitic religious context.”40

10 The ideology of the “sacred marriage,” as it survived in the first millennium BCE, can also explain the preoccupation of kings with building projects, and particularly the notion of constructing magnificent royal gardens. The “sacred marriage” typically takes place in the “holy garden” of the goddess, which the king is required to tend as its “gardener.”41 Thus, in Sumerian “sacred marriage” hymns, the goddess sings of her vulva, her “uncultivated land” and asks “who will plough it?” Dumuzi, as expected, offers himself up for the task.42 Furthermore, the importance of gardens in Near Eastern palace architecture is also reflected in the tale of Inanna and the Huluppu Tree where the legendary hero-king Gilgamesh poses as the gardener of the goddess;43 in his steps, numerous historical ancient Near Eastern kings propagated myths about their humble origins as gardeners.44 In reflection of the cosmic order, the king’s palace is the heart of the world and the focal point of communication between gods and humans.45 Hence, palaces tend to boast elaborate gardens, which symbolize unbreakable divine favor and evoke the “sacred marriage” between the king and goddess.46

11 Herodotus describes such a beautiful palace at Celaenae in Phrygia,47 which Xenophon had also visited.48 The Persians were especially adept at creating such gardens which were known as Paradises (παράδεισοι) and were invested with considerable political significance.49 Xenophon describes how Astyages the Mede offered his grandson Cyrus the privilege of hunting in his paradise as a gesture of recognizing his legitimacy — the boy was destined to be a king.50 Xenophon is also appreciative of the relationship between kingship and agriculture, as exemplified in the tale of Cyrus the Younger and his paradise at Sardis, related in the Oeconomicus.51 There, we read that, when Lysander was shown around this magnificent royal garden, he was surprised to realize that the king himself toiled regularly in the garden and was responsible for the impeccable alignment of its rows. According to Critobulus, another of Socrates’ interlocutors in the treatise, the king “pays as much attention to husbandry as to warfare,”52 a statement to which Socrates responds as follows:53

ἔτι δὲ πρὸς τούτοις, ἔφη ὁ Σωκράτης, ἐν ὁπόσαις τε χώραις ἐνοικεῖ καὶ εἰς ὁπόσας ἐπιστρέφεται, ἐπιμελεῖται τούτων ὅπως κῆποί τε ἔσονται, οἱ παράδεισοι καλούμενοι, πάντων καλῶν τε κἀγαθῶν μεστοὶ ὅσα ἡ γῆ φύειν θέλει, καὶ ἐν τούτοις αὐτὸς τὰ πλεῖστα διατρίβει, ὅταν μὴ ἡ ὥρα τοῦ ἔτους ἐξείργῃ.

In all the districts […] he [= the king] resides in and visits he takes care that there are ‘paradises,’ as they call them, full of all the good and beautiful things that the soil will produce, and in this he himself spends most of his time, except when the season precludes it.

12 Cyrus54 swears by the Sun-god, who often poses as the patron of ancient Near Eastern kings,55 that he engages daily in some task of war or agriculture. In response, Lysander concedes that Cyrus deserves his happiness on account of his virtues.56 At Oeconomicus 5.2, Socrates explains that the earth, typically identified with the fertility goddess, as we saw in the “sacred marriage” context, yields to the cultivators “luxuries to enjoy” (καὶ ἀφ᾽ ὧν τοίνυν ἡδυπαθοῦσι, προσεπιφέρει). Yet, at the same time, the earth “stimulates armed protection of the country on the part of the husbandmen, by nourishing her crops in the open for the strongest to take.”57 Moreover, she “willingly teaches righteousness to those who can learn; for the better she is served, the more good things she gives in return.”58

13 Xenophon’s observations, put in the mouth of Socrates, accurately explain the ideology of the “sacred marriage” often allegorized in ancient Near Eastern myths about good and bad farmers and/or gardeners who please or displease the goddess with their labor. In these tales, the king poses as the farmer/gardener and lover of the goddess in the footsteps of her consort Dumuzi.59 If the king is successful in continuously pleasing the goddess, he will maintain his position. If not, there will be a breakdown in their relationship. Indeed, she is often discussed in connection with a usurper, who is likely to take over as the next king and, of course, will become her next ‘lover’. The concept is made clear in several mythic tales, including the myth of the gardener Shukaletuda.60 Shukaletuda, we are told, enjoys the trust of the goddess for a brief period and is appointed as her gardener, but he uproots the plants of her sacred garden and rapes the goddess while she is asleep in her garden. As soon as Inanna wakes up and realizes what has happened to her, she vows that the Sumerian people, among whom Shukaletuda hides himself to avoid divine retribution, will “drink blood.” In other words, her punishment of the people will come in the form of an enemy army that, under her auspices, devastates every city it attacks.61 In similar spirit, at Oeconomicus 5.19–20, Socrates admits to Critobulus that the gods control the operations of agriculture no less than those of war.

15 Oshima (2007), p. 355. Van der Spek (2009), p. 110–111 argued that, since we have found no Greek temple in Babylonia, the Greeks may have used the temple of Bēl, now identified with Zeus, as their main cultic space. Wright (2010), p. 58 discusses the identification of Zeus with local Ba’als, possibly since the time of Alexander, as indicated on his famous coins representing the Pheidian Zeus of Olympia.

16 Hdt. 1.181.5–182.1–2; our translation, modified from that of Godley (1920). This part of the article is derived from Anagnostou-Laoutides (2017), p. 84–86.

17 In Urnamma A, Inanna is portrayed as lamenting the king’s death. She praises his charms (h-li-a-ni) and refers to her ğipar as her shrine that “towers up like a mountain.”

18 Note that Herodotus has occasionally, though not invariably, used φοιτᾶν to mean sexual intercourse; see Powell (1938), p. 375, who cites the following examples s.v. φοιτῶ: “2. (5) sexually, go in to: of the woman, τινι 3.69.6; παρά τινα 2.66.1; 1.11.2; 4.11; of the man, παρά τινα 5.70.1.”

19 See, for example, Eur. Cycl. 582: Γανυμήδην τόνδ’ ἔχων ἀναπαύσομαι κάλλιον ἢ τὰς Χάριτας; Machon of Sicyon, Chreiai, 286, 328: ἀναπαυόμενον μετὰ τῆς Γναθαίνης (ed. Gow); also, in Athen. 13.579e–580a; Plut. Alex. 2.4: ὡς μηδὲ φοιτᾶν ἔτι πολλάκις παρ᾽ αὐτὴν ἀναπαυσόμενον.

20 Noegel (2004), p. 134–135; see also Maul (2007), p. 368; cf. Durand (1988), p. 455–482.

21 For incubation as practiced throughout Mesopotamia, see Kim (2011), p. 27–60.

22 Sasson (1984), p. 285; DeJong Ellis (1989), p. 136; see also Butler (1998), p. 224–227. For incubation among the Jews under ancient Near Eastern influence, see Moore (1990), p. 78–86; Ackerman (1992), p. 194–120. On the Jewish disapproval of incubation, which was perceived as being linked to pagan necromancy, see Schmidt (1994), p. 261–263.

23 See Paus. 2.27.3 and Strabo 8.374; for an overview of incubation in the ancient Near East, see Kim (2011), p. 27–58. Cf. Husser (1999), p. 20–22, who warns against the conflation of the “therapeutic incubation,” popular during the Hellenistic period, and the “oracular” incubation mainly practiced in the ancient Near East in earlier times.

24 Diod. Sic. 1.25.5.

25 DeJong Ellis (1989), p. 178–179.

26 E3/1.1.7 CylA; see Edzard (1997), p. 69–70. Starting with the Akkadian dynasty of Sargon, ancient Near Eastern kings would often place their daughters as priestesses of the god. On this, see Hallo – Simpson (1997), p. 175.

27 Hurowitz (1992), p. 47–48, 153–156. Van Buren (1952), p. 293–294, with n. 1, draws our attention to the king’s sense of duty and obedience to the expressed wish of gods to have new temples built in their honor. Gudea, for example, was instructed in a dream to build a new and better Eninnu for Ningiršu, the Amorite Samsuiluna (ca. 1792–1712 BCE) was commanded to build a temple by Šamaš, and Waradsin of Larsa (1770–1758 BCE) by Nannar.

28 Butler (1998), p. 17–19; see, also, Chapman (2008), p. 41–44.

29 Gurney (1981), p. 143; cf. Beckman (2003), p. 159.

30 Hdt. 1.77 and 188.

31 Gadd (1948), p. 58–59 with Böhl (1939), p. 162 (i 1.170); cf. Reiner (1985), p. 1–16, esp. p. 2; Beaulieu (1989), p. 71–72, 127–132; Beaulieu (1994), p. 39–40. A liver omen also confirmed the god’s “desire,” since erešum can actually mean both demand/request and wish/desire. But given that ērišu, of the same root, means the bridegroom, the erotic connotations of the word cannot be missed.

32 Garrison (2012), p. 45.

33 Herodotus’ work is full of obscure oracles that require careful interpretation. For oracular allegory in Herodotus, see Benardete (1969), p. 7–9; cf. Hartog (1988), p. 131–133, where oracles — in the particular example, false oracles or ψευδομάντιας (Hdt. 4.69.2) — exemplify the ‘otherness’ of the Scythians.

34 Mikalson (2000), p. 55–60 argues that, regardless of whether the oracles were historical or part of contemporary traditions, and not necessarily based on actual events, one has the impression that Herodotus relates them as part of his storytelling in order to teach his audience through the stories and mistakes of those who related the oracles to him. On p. 143, while discussing Herodotus’ appreciation of human impiety as the source of misinterpreting “the import of oracles, omens, and dreams,” he also notes: “Herodotus himself expresses (3.38) and exhibits considerable respect for the ‘customs’ (νόμιμα) of others, however strange they might seem…but, however open-minded, he cannot silently accept sexual intercourse in religious settings…,” citing as the first of his examples the “most shameful” custom of the Babylonians recorded at 1.199.

35 Harris (2000), p. 122–157 holds that Herodotus distances himself from popular religion precisely by referring to cases in which erroneous interpretations of oracles precipitated one’s downfall. On Herodotean oracles as literary forgeries designed to promote political objectives, see Struck (2002), p. 181–183.

36 Hurowitz (1992), p. 162.

37 Melville (2006), p. 390–391.

38 Granius Licinianus, History of Rome, 28.6 (with Diana). Eddy (1961), p. 141–145 refers to Antiochus marrying Ištar at Babylon. Consider, too, his marriage to Nana at Susa, as recorded in 2 Maccabees 1.13–15 and Polybius 31.9.1.

39 Either Antiochus was a usurper who murdered his brother out of political ambition or, given that there is no evidence clearly associating him with the murder of Seleucus IV, he was the remaining ruler who managed to overcome the conspiracy that brought about the demise of his co-ruler. See Daniel 11:20, with Bahrani (2002), p. 19 and, contra, Shea (2005), p. 31–66.

40 Pongratz-Leisten (2008), p. 66.

41 Widengren (1951), p. 9, 11, 15.

42 Sefati (1998), p. 224–225.

43 See Kramer (1944), p. 33–37; Frayne (2001), p. 130; Wolkstein – Kramer (1983), p. 4–5; Anagnostou-Laoutides (2017), p. 43–46.

44 Westenholz (2007), p. 36–41; Stronach (1990), p. 171–174.

45 Turner (1979), p. 26.