#king lindorm

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

did King Lindorm for an illustration class project lmao

the prof called me a "coattail rider" for having an anime style so i went momentarily insane you're welcome

#rawrawraw#king lindorm#its funny being an artist because it's 50/50 looking at old pieces and being shocked at your skill#but also nitpicking the fuck out of them and going 'oh i could draw this better now'#anyway trans rights dragon let's goooooooooo

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The White Worm King

A series of illustrations retelling the Danish fairytale 'Kong Lindorm'. The Shepherd's Daughter is tasked by the Red Queen and the Red Prince to find The White Worm King, who's threatening the Red Kingdom. No man has ever been able to slay the beast, and neither does the Shepherd's Daughter - instead she discovers the White Worm King is the banished and lost princess of the Red Kingdom, the twin sister of the Red Prince.

Together, the White Worm King and her Shepherd work to take back what is theirs.

#digital art#digital painting#artwork#original character#character design#drawing#digital illustration#kong lindorm#white worm king#narrative illustration#sapphic art#sapphic#wlw#wlw art#fantasy#fantasy illustration

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

New oc, Natriks the Frostwyrm.

Once a warmongering young king who devoured the dragon's heart. But instead of becoming the majestic creature he was, Natriks was cursed to be trapped in the inferior form of a lindorm, forever crawling on the ground despite having so-called wings.

#digital art#oc#oc art#original character#character illustration#illustration#my oc art#character art#character design#digital drawing#dragon art#dragon oc#dragon#wyvern#creature design#creature art#creature#ocs#artwork

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lindworm: Chapter 1

(This is a little over half of the first chapter I had planned to share the whole thing, but then I realized it was 7,000 words. You can buy and read the rest of Lindworm here!)

��Thank you so much for thinking of me,” Marit said, “but really I would rather not marry a monster.”

Marit would not have thought herself the sort of person to talk back to kings, had she ever had cause to contemplate such matters. But then she never would have thought the king the sort of person to sacrifice a girl to a lindworm, and yet here she was, the third victim.

She was only seventeen, and this wedding was a death sentence.

Six months ago, Prince Harald had set out to find a bride, and had been stopped by a great serpent in the road. Since then, the serpent—the lindworm—had eaten two foreign princesses, both after a sham of a wedding. Both women had thought they were coming to marry Prince Harald.

Here, in the forest outside the capital city, rumors had flown. Rumors that they would shortly be at war with both kingdoms that had lost a princess, and rumors, more interesting to their small family with no members likely to be sent to the battlefield, of the lindworm, of why a man-eating dragon would be welcomed to the palace and fed. Rumors that said the lindworm was Prince Harald’s brother, that the king humored it instead of killing it because the monster was family.

Marit didn’t know how much truth there might be to such rumors. She didn’t know how a queen could bear and birth a serpent, but she did know the world was full of strange, incomprehensible things.

The king stared at her, his men standing stiffly by. It had not, of course, been thoughtfulness that led him to her cottage in the woods. Marit knew this, and knew that the marriage was not optional, and that one could not speak to a king in this manner and expect to keep one’s head. But when one has already been sentenced to death, such things as respect for royalty matter very little.

“It is not an offer,” the king informed her when he found his voice. “It is a command, and you may choose to obey or not, but willing or unwilling, you will find yourself before a priest in my great hall one week from now.”

One week, she thought. One week to live the rest of her life. She could run—could she run?

No, if the king was leaving her a few days to say her goodbyes, it was only because he knew she could not run. There would be guards posted. She would be caught and brought back. She would still end the week dead, and likely her father and sister, too, if the king suspected they had helped her. As they certainly would.

Her family—they were away from the house now, deeper into the woods, scavenging. There was little left to eat, their winter stores almost empty by March, and the ground still too frozen to begin the year’s planting. She had stayed behind to tend to the animals, too likely to slow them down after twisting her ankle yesterday, falling from a tree; it had barely hurt, and would be healed by tomorrow. The king would be long gone before they returned, and it would fall to her to explain her upcoming death.

“There will be a bride price, of course,” said the king.

Marit wasn’t quite sure what a bride price was, thought it may be like a dowry—she’d sewn items, slowly, over the last several years for her dowry, but doubted the lindworm would demand her linens as well as her life.

The king went on to explain the bride price, the amount of money her father would be given for this farce of a marriage—the opposite of a dowry, then, and a staggering amount.

It had been a long, brutal winter following a short, dry summer, and for that price Marit may have volunteered herself. Any number of young women may have; it was enough to save not only their own small farm, but those of a few near neighbors. Enough to buy a second goat, a few more chickens, enough to pay all of their debts in the city and have their broken tools repaired.

For such a sum, she would have volunteered. She would have gladly given her life to so dramatically improve the lives of her father and younger sister.

But the king had not asked. The king had demanded, and Marit knew she would resent him for however many days she had left to do so.

He left her, as she’d expected, with guards posted nearby, and she led the animals back to their shed and let herself back into the cottage, not wanting to look at them, their clean uniforms with shiny brass buttons, their polished boots slowly gathering mud, their faces as they avoided her eyes, because they knew, must know, that this was wrong, and yet they were loyal to their king, and would not let her run.

~

Marit watched through the back window, working idly on her knitting, unable to stay focused on the difficult stitch she’d meant to master this week, until she saw her sister and her father coming out from the woods. She ran to meet them, and hurried them inside before they could ask about the soldiers scattered about. And then she told them.

“Why you?” Greta cried. “Why you?”

She hadn’t asked how he’d chosen her, out of all the unwed maids within walking distance of the palace. She didn’t think she wanted to know why it was her that must die, and not Annette, who had no father to protect her, or Martine, who was more beautiful, or Signe or Gretchen or any of the other girls she knew.

She didn’t want to die. She didn’t want to be the kind of person who wished death on her friends, either.

Besides, the lindworm had already eaten two women, and there was no reason to expect he might stop at a third. They may all be dead before this ended, Gretchen and Signe and Annette and Martine, and the younger girls, Greta and her friends, all the forest, all the city, someday all the kingdom sacrificed to satisfy the appetite of a monster that should have been killed the moment it showed itself to Prince Harald.

She could only hope that the fathers of the dead princesses would declare war, that they would kill her king and his lindworm with him before the whole country was devoured.

King Olaf had always been known as a kind and noble king. He’d lowered taxes and held festivals and been much loved, before these last six months, and Marit didn’t understand. She didn’t understand how a good king could become a bad one overnight because of one monster.

Maybe it was his son. Marit would throw the whole world over for Greta, she knew, but she’d been at Greta’s side since she’d emerged from their mother’s stomach, been the first to hold the new baby, tiny and wrinkled and red, getting blood all over her vest, as their father had said his goodbyes to Mama, only turning his attention to Marit and the new baby when his wife was gone.

For Greta, for her father, for Mama if she’d lived, Marit would do anything. But if a boar walked out of the woods and claimed to be her long lost brother, she wouldn’t take him at his word, wouldn’t escort him into the city to trample the blacksmith just because he asked her.

She didn’t think the king could hide a paternal relationship with a lindworm for several years. They must have met only when he stopped the prince on the road. And Marit didn’t understand.

She gathered Greta in her arms and listened to the younger girl cry, unable to shed any tears for herself, unsure why. She looked over Greta’s head at her father, and saw the same desperate sadness in his eyes that she had seen when she was five years old, and her mother was dying in childbirth. Her father loved her, but he could do nothing to save her, and they all knew it. He could not defy the king; to try would only make him angry, would likely risk Greta’s life too.

He came and wrapped himself around them both, and Marit thought, but was not quite sure, that he wept too. She sat, dry-eyed, between them, for long hours, until it was time for dinner and bed.

They watched out the window as a new group of soldiers marched in, and the first group left. At least they weren’t expected to feed and board their prison guards.

In the morning they found that the soldiers would let Marit go where she pleased, but one or two would always follow, from a respectful distance. No one followed her sister or father, so they went in three different directions, to the neighbors and to the city, Marit to make her farewells, and all of them to give warning. The king is feeding maidens to his lindworm. Marit is the first; she will not likely be the last. Send your daughters quietly to family in other cities, if you can. Marry them quickly to boys in the village, if you can. We do not know why the lindworm wants weddings, but he does, so make your daughters unweddable.

Gretchen, when Marit told her, said it probably had to do with a dragon’s fondness for virgins. She then said that if the king came to her, she would rid herself of virginity with the first man she could find before she would go to the lindworm, with the whole town to watch as proof, if necessary.

Gretchen’s older brother, the only other person there save the guards, too far away to overhear, made a sound of disapproval in the back of his throat, but said nothing.

Marit wondered if it was too late to try Gretchen’s plan for herself, and concluded it probably was—if the lindworm demanded a virgin, then the soldiers would not let her cease to be one. The small chance of success wasn’t worth giving herself to a man she didn’t want and wouldn’t be allowed to keep. And the kind of man who might cooperate with such a plan would likely not make it a happy experience to cherish in her final days. She reminded Gretchen of the soldiers before moving on to the next neighbors.

~

Marit spend her days wandering, mostly. There was work to be done, and she helped, or tried to—her father said not to trouble herself with anything in these last few days, and when she insisted, she often found herself too distracted to finish, or at least to finish well, haunted constantly by imaginings of what the lindworm might be like, how it might feel to be eaten. She remembered breaking a finger in a slamming door as a child, the sharp crack of it, the pain. She imagined the pain and the cracking both amplified as an enormous snake swallowed her whole, as snakes will do, and then, bizarrely, imagined cowering on a banquet table as the lindworm sliced her to pieces with a knife held in its tail, popping each slice into its mouth one at a time, sometimes dipping a slice in a butter-sauce first.

She still had not cried, though she had found herself several times laughing hysterically at humorless jokes she couldn’t explain. Greta didn’t need to know about the butter sauce.

When there were two days left before the wedding, she went out intending to collect eggs from the chickens, and her feet carried her, instead, deeper into the woods.

The guards followed at a distance.

Marit stopped when she saw an old woman ahead. She was short, with white hair spilling from her cap, bright and cheerful in a blue skirt and red vest, and she smiled like an old friend at Marit, and asked why she was so sad.

Marit wasn’t a fool. She knew how it was with mysterious old women in forests, knew they were to be respected. Knew how often they carried magic within themselves. Knew that to cross them was idiocy, and that to be kind and respectful could change the course of one’s life.

So Marit told the woman her troubles, and the woman smiled again. “It will be all right,” she said. “If you obey me, it will be all right. Now, here is what you must do.”

Marit wasn’t foolish enough to think she might live through this, but she wasn’t foolish enough to ignore the gift of a wise woman in the wood, either, even when that gift was the strangest advice she’d ever been given. Wear ten shifts beneath your dress, have milk and lye and whips waiting in your bedchamber.

She was already going to die; what did it matter if the king’s servants thought her a madwoman?

Ten shifts, though, would not be an easy thing to manage. Marit had two shifts, and two night shifts, which were wool instead of linen, with sleeves too wide to be hidden beneath her dress. She would have to rip them off. Greta owned the same, not much smaller as she was tall for her age, but Marit could not deprive her sister of all her undergarments, so only took one day shift and one night shift from her. That brought her to six, and four more yet to find. She couldn’t buy them; the king’s money wouldn’t come to her father until the day after the wedding. She had her dowry linens, unneeded now, and could use the fabric to make more shifts. But she had two days left to live, and wasn’t willing to spend her last precious moments sewing. With Greta’s help she converted one white bedsheet into a shift, but would sacrifice no more time when she had so many goodbyes to say—to friends, to livestock, to trees and streams and every future she had ever imagined for herself.

She begged one more shift from Olga, whose family was wealthier and who had one to spare for an acquaintance going to her death. Eight shifts, eight, two short, and no time to find more. It would have to be enough.

~

The morning she was to be taken away, Marit’s father pulled out her mother’s wedding dress and offered it to her.

Marit shook her head. “It should go to Greta. To a real wedding.”

“You shouldn’t be alone,” her father said. “Take it, so your mother can be with you, as Greta and I cannot.”

So Marit put on her eight shifts, and she put on the dress. She was a bit smaller than her mother had been when she married, and it still fit despite the extra layers. Greta had wanted to make her a crown of flowers to match, but there were still few flowers in bloom, so she wove the crown from evergreen branches instead, coating her hands in sap, and placed it carefully on her sister’s head.

The three of them waited, solemnly, for Marit to be taken away. There was nothing left to say. All of the goodbyes were finished, all of the plans made. The next morning someone would come from the palace with the bride price and whatever was left of Marit to be buried. Her father would sell the animals and the house, give them away if he couldn’t sell them fast enough, and he would hire a wagon to take them far, far from the capital, to start a new life where the lindworm would never touch Greta. They’d gone over the details last night. Greta had cried again.

Marit still hadn’t cried, and thought she might be able to, now, but would not let herself; she didn’t want her tears seen by whoever took her away. She found she was more angry than sad. She felt a sharpness growing within her. Her life was forfeit, and so too was her sense of obligation to respect, to loyalty. The king, the queen, the prince, the priests who’d performed the weddings and the soldiers and couriers who’d stood by—damn them, she thought, damn them all, and damn the idea she owed them the barest amount of anything.

The king came to fetch her himself, and she refrained from spitting in his face only because of the guards that surrounded him, the fear they might kill her where she stood and cost her father the bride price.

The king was different, not angry and demanding as he had been a week ago, but stiff with an awkwardness that might almost be shame. Marit hugged her father and Greta one last time, and followed him back toward the city, his guards forming a circle around them. She didn’t care that he may feel shame; she had enough anger by now for the both of them.

He was quiet, and Marit didn’t want quiet. Not quite understanding the compulsion, she found herself goading him.

“What will happen after this?” she asked, and the king looked at her, then quickly away again. It was a long walk on foot, and she didn’t know why a king wouldn’t take a carriage, but she didn’t mind the extra time in her forest.

“You will be prepared for the wedding by lady’s maids. The wedding will be in the great hall, and after that we will have a banquet.”

“Not tonight,” Marit said, spurred by the thought of Annette being sent hundreds of miles away to an uncle she’d never met, of Gretchen searching for a man to defile her rather than be eaten. “Not to me. What will happen to your kingdom? After me, you’ll kill off every maid in the country, and then I suppose you’ll have to go to war, and find slaves to feed his appetite? Discipline is important for growing boys, Your Majesty. Learn to say no to your son.”

He raised a hand as if to slap her, and she tilted her chin forward, daring him—let him hit her, here surrounded by a small army, let all these soldiers, already uneasy with their roles, go home and report to their friends and families that their king was a man who struck defenseless maidens.

He lowered his hand, leaving Marit oddly disappointed. It would have been another reason to be angry, and her anger was protecting her from her fear.

The king sighed heavily. “We all do foolish things for our children.”

She wondered if he meant the lindworm, or only Prince Harald, who could not be married until it was satisfied. It didn’t matter—the result was the same for her.

“Yes, Your Majesty,” she said, suddenly exhausted. Maybe a king could afford to do foolish things for his children. Her own father had to be sensible—foolishness would only have hurt Greta. She felt the anger draining away, the fear rising up again. She didn’t want to die.

~

They arrived at the palace from a side gate, not taking the wide, paved road beneath the cherry trees, where any number of people might have seen their arrival. The king and his soldiers handed her off to a large group of women, some more elegant than others, and she asked him, before he left, what time the wedding would be.

“At eight o’clock,” he said. “Will that give you enough time to prepare?” One of the more elegant women assured him it would, and he told her, “Give the girl whatever she wants. It’s her wedding day, after all.” He laughed, unamused, more bitter than cruel, and then he was gone.

“Is there anything special we can do for you, miss?” asked one of the plainer women, who was likely a maid.

Marit thought of the old woman in the forest. “This is going to sound a little strange.”

All of the more plainly dressed women left to carry out her last request, leaving Marit with a flock of beautiful women whose most simple everyday clothes were likely ten times more expensive than her mother’s wedding dress. They tried to have her out of it, into borrowed silks instead, but she refused. It was the last gift from her father, the only familiar thing in this place. She kept her evergreen crown as well, but let them take it away long enough to clean away the sap, rubbing it from the branches and brushing it out of her hair.

They re-braided her hair into a more elaborate style, stringing in gemstones to match her dress, and applied powders and creams to her face, which itched and made her sneeze. She watched them carefully, picking out one who seemed both kind and fancy enough to know little of a peasant’s daily life. She drew her away from the crowd and explained, in a whisper, “I haven’t any underthings. I only own the one shift, and I left it for my sister, so she would have one to wear on laundry day. I didn’t think it would matter, when I’m only to die tonight, but I’m—I’m embarrassed to have all these fine people watching me, thinking that if the light hits just so they’ll see I’m not dressed properly.”

The woman believed, somehow, that a peasant girl might have come to a royal wedding with no undergarments, and offered to find a spare shift.

“Could I have two, please?” The woman raised her eyebrows, and Marit ducked her head. “It’s a tradition—I know it shan’t be a real wedding night, but it’s a tradition to make the groom work a little harder the first time.”

The woman believed the tradition she’d never heard of, as well, and came back shortly with two more shifts, beautiful, silken things, bringing Marit to the required ten.

The next problem came when she realized the women had no intention of leaving her alone while she took off her wedding dress and put on the shifts, which was awkward for more reasons than the eight shifts she already wore. She explained that she was not accustomed to being seen undressed by strangers, and finally they left her, for the first moment of privacy she’d had in hours, and the last she expected to have in her life.

She took off the dress and put on the shifts. She paused to look in the mirror—a thing she’d heard of but never before seen—and wondered if that was what she truly looked like, or only the effect of the powders and creams. She pulled the dress back on, took a few deep breaths—she had not cried yet, she would not cry now—and reopened the door so that the women could help re-fasten the dress in the back.

They set the evergreen crown back on her head, and took her to the priest that would read her last rites.

The hall where they held the wedding was gorgeous, with shining wood floors and dark walls covered in rosemåling, blue and gold and red. All the court was seated when she arrived, dressed in their finest clothes, looking horrified. She recognized the king and the queen and the prince, familiar from a dozen parades, sitting in the front row. The rest were strangers.

And then she saw the lindworm.

It was the height of six or seven men, white like a maggot, or the mold on stale bread. It had dark wings on its back, too small to hold its weight in flight, and shiny white fangs quite visible even when its mouth was shut. It had no legs. There was a crown balanced at the top of its head, the size a man would wear, which might have been funny if it hadn’t planned to eat her.

It was staring at her with an expression of mild curiosity, recognizable because its eyes were the eyes of a man, over-large, but still small in its serpent head, the same shade of blue as a dozen young men she’d seen in the city.

#lindworm#fairy tales#folklore#Fairy tale retellings#new release#my book#it's almost here#two days#prince lindworm#king lindworm#king lindorm#kong lindorm#wax heart press

32 notes

·

View notes

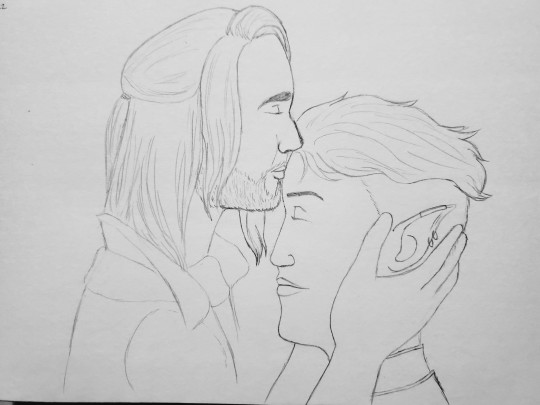

Photo

The Bride & The Lindorm, Henry Justice Ford (1897), but make it homoerotic elves.

#ffxiv#final fantasy xiv#elezen#duskwight#aumeric de morelle#tristeaux de morelle#suggestive#king lindworm#the bride & the lindorm#the pink fairy book#when I commit to an aesthetic I commit hard

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Concept: a Beauty and the Beast AU where Erik is a monstrous werepanther because of his father’s and uncle’s actions, terrorizing Wakanda, and will only relieve the country of his havoc in exchange for a bride. Enter Prince T’Challa who accepts the beast’s conditions to protect his people and so begins a tale as old as time.

#with some elements of Bride of the Lindorm King and Leigh Bardugo’s Ayama and the Wood#t’cherik#tcherik#black panther#bp#marvel#mcu#t’challa#erik killmonger#erik stevens#n’jadaka#killchalla#beauty and the beast#beauty and the beast au#abbie speaks#mine#my writing

266 notes

·

View notes

Photo

King Lindorm, from The Pink Fairy Book by Henry Justice Ford (1897)

#henry justice ford#art#illustration#golden age of illustration#19th century#19th century art#vintage art#vintage illustration#vintage#english artist#british artist#books#book illustration#childrens books#fairy tale#fairy tales#fairy tale illustration#giant snake#classic art

2K notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Beauties and Beasts: Ep 3: “Bride of the Lindorm King,” or “Patience and Consent Are Everything”👰🐉

In this episode, we discuss the Scandanavian folktale, “The Bride of the Lindorm (or Lindworm) King;” specifically why consent is important in a relationship and why you must peel your onions before you eat them.

- DisneyFanatic2364

Welcome to another “Beauties and Beasts,” an in-depth analysis into “Beauty and the Beast” and other fairy tales. I first found about that folklore when I watch her audio drama Bride of Discord (it’s pretty good) and must say… wow. Speaking of snakes here’s my lost asnwer to question about White Snake: it’s not Disney short film, it’s actually is a 2019 Chinese computer animation fantasy full-lenght film directed by Amp Wong and Zhao Ji, with animation production by Light Chaser Animation (and Warner Bros. Far East) inspired by the traditional Chinese fable Legend of the White Snake, serving as a prequel to the original story and let’s just say it’s not much for children for some reason ehm"cough"😳. Anyway it is still interesting story that I hope it will one day be another topic to Beauties and Beasts. And also for those who still want audio-drama sequel from DF despite this project been finished and closed please, please stop with this. If you want it so desperately then do it audio-drama on your own only with her permission. She’s person with her own goal and we should accept that and show her respect for all she done for us. That’s all I wanted to say. Enjoy her hard work to infinity and beyond.🙂

Next episode: Beauties and Beasts: Ep 4: “Shrek,” or “Ogres Have Layers!”🤢🧅👸

(Note: Yeah not best emoji combination but I couldn’t find anything better. They don’t even have a donkey emoji among other animal emojis. I mean what gives?!)

...

Hey Guest, sorry it took me a while to get to this one, I’ve been trying to finish the next chapter to my latest fic.

Well, I guess I can’t really comment on the whole “Bride of Discord” audio drama since I’ve never watched MLP, so I guess no issues about harassing her regarding more episodes of that from me ^^”

Oh, I see. After listening to this, I’m kind of interested in watching that movie (White Snake) now. Sounds interesting :)

Yeah, definitely. That sounds like it’ll make a great episode for this series. :D

I really enjoyed this one by the way. It sort of reminded me of this one episode of this anime I used to watch called “Inuyasha” where the main girl is almost married off to this demon who kidnapped her. He’s really ugly, but his older brother is really handsome and he believes that he can find love with the main girl. I don’t remember how the episode ended, but I don’t think it ended too well for the ugly demon, hehe ^^””

It makes sense that her next episode is Shrek. That’s literally what kept coming to my mind with the whole onion and layers thing, lol! xD

Oh don’t worry, I think those emoji’s work just fine, lol. I certainly get the idea from it xD

I gladly await the next episode Guest! Til next time! :D

0 notes

Text

Monstober Day 31 - Lindworm

When they were left alone in the bridal chamber the lindorm, in a threatening voice, ordered her to undress herself.

'Undress yourself first!' said she.

- Prince Lindorm, Scandinavian fairytale

----

Continuing the grand tradition of me being late with these, here's day 31, the Lindworm.

The Lindworm is sort of a cross between dragon and serpent found in Scandinavian folklore. It's also at the center of one of my favorite fairy tales so let's end this run with a storytime.

Prince Lindworm is a Scandinavian tale and has an Aarne-Thompson grouping of ATU 433B (King Lindorm). It goes like this:

A childless queen is approached by an old beggar woman who promises that she will give birth to twin sons if she follows a few simple directions. The queen has to take a bath in running water, and underneath the bath she will find two red onions. Then she must peel the onions and eat them. Simple right?

Well when she sees the onions, the queen is so excited that she forgets to peel the first one and eats it skin and all. She remembers in time for the second, but the damage is done. The queen gave birth first to a lindworm. He was seen only by the lady in waiting, who chucked him out the window into the forest next to the castle. The second boy was perfect in every way, and was shown to the king and queen, who did not know of the lindworm. They were delighted by their perfect little prince.

When the young prince was old enough to marry thethe king and queen urged him to go to the neighboring kingdom to find a bride. He agreed and set out on the journey, but he got no further than the first cross-roads before his path was blocked by the lindworm.

The creature told the prince that he (the prince) would not be able to marry until he (the lindworm) has a bride. The prince returns home with this news, but his parents tell him to go out again, and again he's stopped by the lindworm with the same message.

After the third attempt, the king and queen invite the lindworm to the castle, and offer up a maid for his bride. But the next day they find the girl torn to pieces and the lindworm again saying that the prince can not marry until he finds a bride. Day after day a new girl is given to the lindworm, each meeting the same fate as the first.

Then one day a shepherd's daughter is sent to be the lindworm's bride. The girl was terrified when she heard the news, but before she leaves for the palace, she happens to run into an old woman (what are the chances, huh?) who gives her some advice.

When she arrived at the palace the girl asked for a different bridal chamber than the one the lindworm was placed in. There she asked for a tub full of lye, a tub of milk, and as many whips as a boy could carry. With her requests granted, she puts on seven shifts beneath her wedding robes and waits for her husband. The lindworm arrived and ordered her to strip. She responded by asking him to shed a layer of his skin first. He complied, and she removed one shift. They repeat this until the lindworm sheds his seventh layer, leaving a strange naked mass behind.

The girl quickly grabs it and dunks it first in the lye, then whips it as hard as she can (👀), before bathing it in the milk. She then carries it to bed and sleeps while embracing it. The next morning, when an attendant checks the room expecting to find more of the horrible same, he is shocked to see the girl asleep next to a handsome young man. The man reveals himself to the Royal Family as the eldest prince, and as such must be married before his younger brother. With that out of the way, the younger prince is finally allowed to be married, much to everyone's relief.

I think the morals here are clear: follow instructions carefully, listen to the advice of old ladies, and do your best to uh... Work out the kinks in your marriage.

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

*laughs in beauty and the beast, bride of the lindorm king, and the 29739702 legends, tales, fanfictions, stories, TV shows, movies, and comics with that exact same plot*

#cybird ikemen#Ikemen Revolution#ikerev#ikemen lancelot#lancelot's route#yes yes you're a horrifying creature lance we see you#so scary much wow

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey, I've been an avid dragon enthusiast since I was a kid and your blog is a huge inspiration! Would you mind doing England for the Here Be Dragons prompt?

Certainly! I am glad to hear you are a dragon enthusiast, I am the same!

So, I have already done Southern England in this ask here so to do the rest of England we would need to do the counties not included there - so Northumberland (my home county!), Tyne and Wear, Durham, Cumbria (my partner’s home county), Yorkshire, Lancashire, Merseyside, Greater Manchester, Derbshire, Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire, Cheshire, Staffordshire, Leiscteshire etc. etc. (I was going to list them all then I realised there were A LOT so apologies dear anon if I missed yours!).

So the main difference between your ask, England in general, and the previous ask, Southern England specifically, is that in most of England we do not have the green wyvern or vouivre. The dragons we have are the lindorm (Vivernapterous fafnirus) the smok (Drakon drakon) and the cockatrice (Basiliskos gallimimus).

The lindorm is a long brownish green serpentlike dragon with two small forelimbs. It lives in burrows and deep ponds and eats small game birds and animals. In English folklorish tradition the lindorm is capable of two great feats - the first is being able to grow to impossibly long lengths, and the second is to grow into two dragons if it is split in half.

The most famous lindorm myth from England is that of the Lambton Worm. Once the Earl of Lambton caught an immature lindorm (eel-like in appearance) and, deciding it was too gross to keep, threw it into a well. This dragon grew to a huge size, wrapping three times around Worm Hill near Lambton (often stories say Penshaw Hill, as this is the big famous hill with a cool building on it - Worm Hill is a smaller hill much closer to the river). The Earl asked a witch what to do, and she said he must wear spiked armour to do battle with the dragon, and once the dragon was slain he must kill the next living thing he saw, or else the Earls of Lambton would all meet unquiet deaths.

The Earl planned to have dogs released once he killed the dragon so that he may kill the dogs too, and he marched out to Worm Hill wearing the spiked armour. The dragon tried to wrap itself around the earl and was impaled on the spikes, eventually bleeding out. In celebration, the Earl’s father ran out to congratulate his son instead of releasing the dogs. Unable to kill his father, the Earl doomed the family to a curse for several generations.

Dogs were also involved in the slayings of the Serpent of Kellington, the Long Slingsby Serpent and the Serpent of Nunnington, all in Yorkshire.Yorkshire dragon slayings have a tried and tested formula - the hero must wear spiked armour (as the Earl of Lambton did) and must bring a dog to snap up parts of the dragon which are cut loose from the main body to prevent the dragon from multiplying (which is biologically impossible, but having a well trained dog aid in a dragon slaying seemed like a sensible move back in the day) and the dragon must be fought in a river, so that spare parts of the dragon are washed away downstream and cannot create more dragons to interfere in the battle. There is a chance one may die to the ‘venomous blood’ of the dragon, most likely the cytotoxic venoms spat by lindorms when they are threatened.

The final lindorm myth of note Not in the South of England (please check the other Ask for a wealth of knucker stories) is that of a little known hero called Scaw who killed the Handale Worm of Yorkshire (there are a LOT of Yorkshire dragon legends).

While lindorms are very important to English mythology, the most iconic dragon is probably the smok, a reddish animal with large wings. This is the dragon found on the Welsh flag and on family crests and sigils throughout the UK - this is the dragon made of chalk at Bures, and it’s likeness is also seen in a church at Wissington.

Being from Northumberland I am obviously going to recount a good Northumbrian tale, that of the Laidly Worm of Bamborough. Northumberland was once an entire country, stretching halfway down modern England and a third of the way up into modern Scotland, and the seat of this kingdom was Bamborough Castle. In mythology, the King of Northumberland married a witch, who made plans against him. She sent the prince Childe Wynd away to Norway and poisoned the king slowly to death. The only witness to this crime was a princess that the witch turned into a dragon, and, distraught, the dragon flew away to Spindlestone Hugh.

Childe Wynd, who had been sent away to perform impossible tasks of bravery, came back a lot sooner than the witch expected, as he was somehow able to complete these tasks. He heard of a dragon terrorising the kingdom and rode his horse straight to the scene, tying his steed up at the legendary Spindlestone. He approached the dragon, sword in hand, but then realised it was a kindred spirit. He kissed the dragon on the nose, and it magically turned back into his sister.

The two of them returned to Bamborough, and Childe Wynd was able to resume his rightful place there as the witch had returned to her natural state -a warty toad - when the princess’ dragon spell had been broken.

Another engaging story is the medieval comedy of the dragon of Wantley in Yorkshire - this dragon was killed by More of More Hall by a swift kick to the backside (the dragon’s weak spot!), and More was paid in virgins and beer (a classic folk hero).

Finally there is the Cheshire story of the Moston dragon, who specifically preyed unfairly on the people of Moston who were just trying to eat some really good apples. It was shot by Sir Thomas Venables.

The less iconic English dragon species is the cockatrice, and I was delighted to find the story of a Cumbrian cockatrice at the small town of Renwick. The story says a cockatrice (chicken dragon) was found underneath a church, so one of the church builders needed to smite it with a branch of magical protective rowan - meaning essentially some builders found a dragon, freaked out and beat it to death with a large stick.

There are a few English dragons which did not fit any specific dragon species in Dracones Mundi, such as the winged Essex serpent (might be a gwiber (Pteroserpens cambrius) out of Wales?), the invisible Longwitton dragon, and then a few other dragons which lack proper descriptions (Sockburn dragon from County Durham, Brent Pelham dragon from Hertfordshire, the dragon that lived under the Drake Stone at Alnwick etc.)

Basically this boils down to England having 3 - to - 5 species of dragon according to Dracones Mundi: lindorms, smoki and cockatrices are found throughout England, gwiberod are found near Wales but also sprinkled in a few other locations according to legend, and vouivre are found in southern England.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

i still want to put king lindorm in my mouth like a jelly bunny awhm

did King Lindorm for an illustration class project lmao

the prof called me a "coattail rider" for having an anime style so i went momentarily insane you're welcome

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Transformation Through Love

I've talked before about the transforming power of love, and specifically about the transforming power of love in "Prince Lindworm." But that was a 20+ page academic essay, and who wants to read a 20+ page academic essay? (Although, if you do, it's here.) So let's talk about it again, in a more casual setting.

We've gone over the bizarro transformation sequence before, but let's run through it again for anyone who's new here: Girl forced to marry snake monster with history of eating wives. Girl wears 10 shifts under her wedding dress. Lindworm asks girl to take off shift, girl demands lindworm take off skin first. Lindworm complies, repeat 10 times. Girl whips nasty mass of skinless lindworm with whips dipped in lye. Girl dunks nasty mass of skinless, whipped lindworm in tub of milk. Girl embraces nasty mass of sticky, skinless, whipped lindworm. Lindworm turns into hot guy.

Now, the majority of the transformation process is extremely violent. It also sort of matches up with the Catholic sacrament of penance, which is consistent with the whole story being a Christian allegory, which you can read about here. And transformation through violence is certainly an established pattern in folklore, as we see most prominently in The Frog King, but also in more minor forms in a number of stories from throughout Europe. Which I will talk about more in a future blog.

But today we're going to focus on that last step. On that embrace.

There are a few things to keep in mind here. Firstly, hugging a dragon-thing that wants to eat you? Really gross and unpleasant. Secondly, hugging any sort of creature that has, through various abuses, become a quivering mass of exposed muscle and veins, likely bleeding profusely? Really, really gross and unpleasant. Thirdly, is "embrace" a euphemism? Maybe. Let's not dwell on the logistics of that. Fourthly, this girl is the lindworm's third bride, which probably means she's the third shot at transformation. An old woman in the forest told her what to do; there's no reason to believe she didn't give the same instructions to the two brides the lindworm ate, even if the text doesn't spell this out; there's a strong tradition in folklore of three people speaking to a mysterious old woman, and the first two ignoring her and dying.

So, my theory: the first two girls may have ignored the instructions entirely, but even if they didn't, they wouldn't have been able to complete the last step. Because it's the last step that makes our heroine remarkable. The last step is a kindness. To take up in your arms a disgusting, suffering thing, which would have destroyed you given the chance, to provide comfort - that takes a special kind of person.

A lot of weird, creepy things went into making the lindworm a man. But ultimately, the thing that changed him was one moment of kindness.

Buy my book here!

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prince Lindorm

One of two Fanservice Friday entries today. This one was requested (and sponsored! I have a ko-fi!) by @weaselmancer, who has been patiently waiting for me to drop another faerie tale on her since February 2016, when I wrote one for Halesia.

(I stand by that work if not its context. Whatever. They don’t deserve this big toblerone.)

So here’s something that’s been on my to-do for yonks. Thanks for giving me an excuse, Vibben.

When the old Emperor died, it was his grandson who succeeded him upon the throne. The first Emperor had been known as a great warrior, and had much expanded the kingdom, and his grandson who was now Emperor was of like make, but he was an unsentimental sort of man, and little was known of him besides his honors, which were many, and his warcraft, which was peerless.

In those days, the Empire was so vast that it was said the sun shone always upon some part of it; though the Emperor’s homeland was far to the North, it was said he ruled in the East and in the West, and the South would soon belong to him. But the general who had tried to claim the South in the name of his Emperor had died, and his city in the West soon came to be threatened by a great serpent, which men called the Lindorm.

The Lindorm was taller than towers, with wings vaster than the sails on ships, and its hide was of scale and steel. It was said that it could change its size, and encircle the whole of the city, but this was not the most amazing thing about it. No, the most amazing thing about the Lindorm was that it could speak, and more astonishing still were the things it said.

“I am the son of the Emperor,” it said, “and now that my father has taken the throne, I shall take a bride to love me.”

The people were astounded by this, for none knew the Emperor had a son at all before he took the throne. But the Lindorm held the city fast in his coils, and no merchants could come to that place, nor the Emperor’s soldiers quit its walls, for the only person the Lindorm allowed to leave was a single messenger, to bear his request to the Emperor.

For a time there came no answer, and the Emperor’s soldiers sought other means to leave the city, but even the ships of the air could not depart, for with a single beat of his vast wings the Lindorm could buffet them with unbearable winds, or call down levinbolts to strike them from the heavens, or pierce their hulls with lances of ice. And so, soon, the only soldiers left in the city were more loyal to the Lindorm, for the Lindorm was present and his power apparent, and the Emperor was distant and powerless to do anything in the city.

It was not for love of the city that the Emperor relented, for he cared for neither the city of the West nor its people, but if he were ever to take the South and surpass his grandfather’s achievements, the Emperor would need the foothold it gave. And it was not so hard to find a bride for a prince—so long as she was not told the truth of the matter.

And so a princess from a faraway vassal nation was sent to the city to marry the Lindorm. But when she saw the prince she had been promised to was instead a great and terrible serpent, she was frightened. His scales glinted like swords, and his wings cast shadows so great she could not see the sun, and she declared she could never love such a terrible creature. The Lindorm roared in anger and despair at this, and from her fear she perished on the very spot.

There were other lands within the Empire, and other princesses; and the Emperor sent them, growing desperate. But all the brides he sent for came to the city in ignorance, and were frightened by the terrible form of the Lindorm. And so the Lindorm sought a bride still, but soon it was said among the nations of the Empire that the prince was no prince at all, and that he had slain and devoured the other princesses, and to send one’s daughter to the West was to send her to her death, and even fear of the Emperor could not compel them to give their beloved children up to be slaughtered.

And when no more princesses would come, a great warrior-king from the East came, saying, “I will do battle with the Lindorm, and I will slay it, for I am the best swordsman in all the world!” And the Emperor was grateful, for the Lindorm was proving more trouble to him than he cared to deal with.

But, though the warrior-king might have been the greatest swordsman in all the world, his blade was no match for the steel that covered the Lindorm, nor could the reach of his arm compete with the Lindorm’s massive size. And so it was that he was slain, and for this, too, the Emperor was grateful, for the warrior-king had been proving more trouble to him than he cared to deal with.

In those days, there was a great Hero who had been born to the kingdoms of the West, but who traveled among the peoples of the South, assuaging their hurts and protecting their homes. To her was given the power to know the truth of things regardless of a man’s words, and she had been blessed also with an unshakable resolve.

And so when the Hero heard of the Lindorm, she heard some things which were true and some things which were not true. But what she knew to be true was that the people of the West were starving and afraid, and as it was the land of her birth, she longed to return home and see the city freed.

Thus it was that the Hero said, “I will deal with him, for I fear nothing.” And she prepared herself to be presented to the Lindorm as his bride.

But a friend she had long traveled with, a Sage, said, “Wait. I am from a land of scholars, as you know; let us seek my old master’s council, and see what can be done,” for she feared that the Hero would fare no better than the princesses, and that her sword would prove no less sharp, and no more effective, than had the warrior-king’s.

And so the Hero and the Sage went together into the hinterlands, where once had been a great city of knowledge that now was there no more. But in the swamps dwelt the old Master, who had trained the Sage when she was much younger.

The Master had great knowledge of many things, and insight into many more, and she advised the Hero, saying, “When you go to present yourself as a bride, put on a dozen dresses, and have brought to you a tub of water and lye, a pail of milk, and an armful of switches.” “I will do these things,” said the Hero. “And when the Lindorm bids you to undress, tell him to shed his skin. When he has shed the last, you may put the switches in the water and with them beat him. Then you must wash him in the milk, and lastly you must take him in your arms and embrace him as your husband.” “These things also I will do,” the Hero promised. “Remember, then, that you must do all this of your own free will.” “It is my will to do this,” said the Hero, “for there should be less cruelty in this world.” “Mark well that you have chosen this,” said the Master, “for it is the only thing that will protect you.”

Then the Master cast them out back into the swamp, and the Hero thanked the Sage for her guidance, and the Sage was glad of a chance to see her old Master again, for though neither would admit it, both were fond of one another, and thought of themselves like a mother and daughter.

Thus did the Hero enter into the West, carrying with her a dozen wedding dresses. When she came to the city and approached its walls, wound all around them was the steely serpent form of the Lindorm. He laid his head in the road, looking upon her.

“None may enter into this city,” he said, “and none may leave it, but for that I should have a bride.” “I am your bride,” said the Hero; “see, I come to you with my wedding gown.” “If you are my bride you shall have a room at the palace,” he said, “but if you are false you shall surely die. Was it my father who sent you?” “No,” said the Hero, “I sent myself.” “Why?” asked the Lindorm. “The people of this city cry out in fear and hunger, and I wish their suffering to end.” “These people do not know you,” said the Lindorm, “and they do not love you.” “I do not know you, either,” said the Hero, “but I am here for you, as I am here for them. I am come to be your bride, if you will have me. We will see if the rest is your affair.” “You are not afraid of me,” said the Lindorm. “I am not afraid of much,” the Hero told him. “Then perhaps you are the bride for me.” “I will take the room at the palace you have promised me,” said the Hero, “and I wish sent to it a bucket of washing-water, a pail of fresh milk, and as many switches as the servant can carry in his arms.” “What are these things for?” asked the Lindorm. “I shall not tell you,” said the Hero, “but you shall find out upon our wedding night.”

So it was that the Hero was allowed to enter the city and conducted to the palace within. She repeated her requests to the servants. They thought this strange, and would not do it, but the Lindorm said, “This is my bride; treat with her as though she were your queen,” and so it was done. The washing-water and milk were brought, and a dozen switches as long as the Hero’s arm and thick as her finger. Then she was dressed for her wedding in all of the gowns she had brought, and in the custom of the Empire she was wedded to the Lindorm.

Thus they retired together as bride and groom to her apartments in the palace. His scales shone in the moonlight, and his eyes were brilliant, but she was not afraid. “Take off your dress,” said the Lindorm. “Shed your skin,” the Hero replied. “None have dared ever to command me in such a fashion as this,” said the Lindorm. “I am a prince.” “If you are a prince, then I am a princess, and I do not fear you besides. I command you: shed your skin, and I shall lay my dress upon it.”

The Lindorm wriggled and groaned, and sloughed off his skin; the outermost layer of his scales was as silver in the moonlight and brittle as moth wings, crumbling when she laid the fine lace of her dress atop it. He was dismayed to see that she wore another gown.

Again the Lindorm implored her, “Take off your dress.” And again the Hero commanded, “Shed your skin.” “Who are you to speak to me in such a way?” “I am your wife, and a hero of the people. You bade them to treat me as their queen; I bid you, do the same.” And a short while later a second skin laid beside the first, iridescent in the moonlight, and she laid a gown of linen atop it.

They went on in like fashion for some time; the Lindorm shed his skin and the Hero laid her dress upon it. Steel and scale and hide lay upon the floor, bedecked with silk and pearls and ribbons. And when they had done this a dozen times and he was bereft of the twelfth, his skin was soft and new.

It was then that she threw the switches into the washing water, and began to beat him with them. All over his body she struck, and though he shuddered and cried out, the Lindorm made no protest. Even as the lye of the washing-water burned against his skin, he endured; even as each of the switches broke in turn, she continued. He thrashed beneath her, but he did not strike her nor bite her. Neither did he attempt to escape, for certainly he might have flown through the open window. His cries resounded, and when the last switch broke he slumped to the floor, and the Hero struggled to catch her breath.

Then she poured the milk over him, washing away the burning lye in his welts, holding the pail in one hand and smoothing over his hurts with the other. She washed him from maw to tail, and when she laid down beside him, the Lindorm with his last strength laid his head in her lap. The Hero put her arms around him, stroking his fingers upon his brow. All of this she did of her own free will. Then they fell to sleep.

In the morning when she awoke, the Hero saw the dozen shed skins and the dozen discarded gowns, and the switches she had broken, and the empty pail of milk and the dried tub of washing-water. But she did not see the Lindorm.

When she turned around she saw instead a man sleeping upon her marriage bed. His skin was fair and new, pink with welts only just begun to heal. His hair was long and golden as the Lindorm’s wings, and when his eyes opened they were the most startling blue.

“Who are you?” asked the Hero. “I am your husband,” said the man. “My husband is the Lindorm,” she said. “Yes,” said the man, “or he was, for I was the Lindorm, and now I am a Prince.” “How came this to be?” asked the Hero. “Such were the circumstances of my birth,” said the Prince. “I was not what my father the Emperor wished me to be, and he named me a stranger to him and cast me out.” “The people of this city have suffered long,” said the Hero. “I am sorry for my part in their sorrows,” said the Prince. “My father’s men will have fled the city in the night, I am sure, for they love me not.” “That is but one of the city’s troubles,” said the Hero. “I shall mend my ways,” said the Prince. “There should be less cruelty in the world.” “So there should,” agreed the Hero.

And so together the pair set about putting things right within the city, and within the kingdom of the West. The seasons turned, and the Prince remained a Prince, and the Lindorm did not return. It was in spring that the Prince came unto the hero to speak with her.

“Thank you for liberating me from my monstrous nature,” said the Prince. “For that I shall always be grateful to you, but if you would not have me for a husband I shall not force you to be my wife.” The Hero thought about this, and said, “It is by my own free will I came to you, and by my own free will shall I remain here. You have been honest and humble in your attempts to make right the troubles of the city, and it is this that makes you princely.” And the Prince was glad of her answer, for he had come to love the Hero.

But though the courage and kindness of the Hero had saved the city and the Prince, the Emperor was unhappy, and loved the Hero not, for now it seemed the West would stand between his ambition and the South.

But that is a story for another time.

#ff14#wol/zenos#x'shasi#shasinos#fanservice friday#original content#starcunning writes#zenos yae galvus#faerietale AU

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

[The having one shape by day and another by night is a common feature in popular tales: as, to be a bear by day and a man by night, Hrólfr Kraki's Saga, c. 26, Asbjørnsen og Moe, Norske Folkeeventyr, No 41; a lion by day and a man by night, Grimms, K. u. H. m., No 88; a crab by day and a man by night, B. Schmidt, Griechische Märchen, u. s. w., No 10; a snake by day and a man by night, Karadshitch, Volksmärchen der Serben, Nos 9, 10; a pumpkin by day and a man by night, A. & A. Schott, Walachische Mærchen, No 23; a ring by day, a man by night, Müllenhoff, No 27, p. 466, Karadshitch, No 6, Afanasief, VI, 189. Three princes in 'Kung Lindorm,' Nicolovius, Folklifwet, p. 48 ff, are cranes by day and men by night, the king himself being man by day and worm by night. The double shape is sometimes implied though not mentioned.]

reading the english and scottish popular ballads and this footnote knocked me out cold. a pumpkin by day and a man by night...

0 notes

Text

I posted 2,066 times in 2022

That's 940 more posts than 2021!

109 posts created (5%)

1,957 posts reblogged (95%)

Blogs I reblogged the most:

@vethbrenatto

@rainbowcaleb

@taldorei-blanket

@the-rxven-king

@criticalrolo

I tagged 518 of my posts in 2022

#cr spoilers - 306 posts

#oeq live - 71 posts

#exu spoilers - 52 posts

#tlovm spoilers - 43 posts

#my art - 25 posts

#my characters - 18 posts

#m9 reunited - 17 posts

#learning to draw - 16 posts

#acofaf - 16 posts

#acofaf spoilers - 10 posts

Longest Tag: 130 characters

#when my ranger would get to the inn and promptly hand over her clothes to be washed even though they didn't have a laundry service

My Top Posts in 2022:

#5

Travis in Campaign 2: I don't know if I want to do a romance. It would be weird.

Travis in Campaign 3: hey, what's up baby? Feel free to come on over whenever you want. ;)

10 notes - Posted March 11, 2022

#4

I just want to say that I suspected that the Tree of Names was holding back the Betrayer Gods since we learned there was a Tree of Names. However, I was NOT prepared for Asmodeus to bust out of it like it was a pop out cake.

11 notes - Posted June 10, 2022

#3

essek widogast

I'm honestly not sure if this was meant or a request? But I love Shadowgast as much as the next critter so here's my go at it.

This is the first time I've tried drawing two people together, and only a the second or third time I've drawn a hand, but for all that I think it turned out okay even though their profiles are a little smooshed. And Caleb's coat really got away from me lol.

11 notes - Posted July 28, 2022

#2

My new dice came in for my new dnd character! She's a homebrew sorta astral-based race and an Oath of Devotion paladin named Taazeni.

The clear dice are liquid core from Urwizards, the blue ones are by Chessex but bought from Lindorm Dice, and I'm not sure where the other set came from because they were a gift.

15 notes - Posted September 14, 2022

My #1 post of 2022

Liam just casually sitting on another tragic backstory pretending he's just got a happy fun-time halfling then letting it all out in a chat with a Christmas elf.

18 notes - Posted March 18, 2022

Get your Tumblr 2022 Year in Review →

1 note

·

View note