#kindless love and punishment

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

At first, Belo believed his Goddess was just really affectionate physically. She frequently cuddled up to him, burying her face in his chest, or absentmindedly stroking whatever area of his body wasn't covering his soft fur, sighing happily as her hand moved. However, every time she's had a friend over, they'd hug briefly, then… hang out on opposite ends of the couch. Between the short greeting hugs, there was little to no physical contact.

…Does his Goddess only enjoy touching… him?

(while not exactly touch-averse, the Goddess in question just generally prefers to have her own space and tends to show affection in different ways. excluding Belo, obviously. his fur is so SOFT and COMFORTING to touch, it feels like her heart will explode from PURE JOY)

[Adorable! I like this. Fem reader.]

He's always thought he was unworthy of such attention.

Powers like him are only meant to guard and fight for their Lords and Ladies. It's not even their job to worship, not to the extent of other casts, but Belo still likes to think he can perform decently in that field... His kind isn't meant to be showered in attention and rewards, they're taught not to expect such for simply executing their duties.

Yet, since shortly after Belo found his place at your service, you've done nothing if not treat him with endless kindless, endless love.

Part of him had wanted to caution you that touching him is beneath your status. That he didn't deserve it.

Hardly ever would those words manifest, because Belo simply couldn't stop himself from enjoying it. He'd hate himself if he said something that made you truly not touch him anymore.

He's always wondered why you did it.

There's no doubt you enjoy the feeling of his fur. He's memorized the way you like to lace your fingers on the tufts that warm his chest, the way you'll slide from the top of his wings to his arms, leaning onto him just so you can feel more of it. Belo often forgets he tends to lean during those encounters, chases after the hand that pets him, forgetting who he's meant to be and who he's in front of. There's no way to describe the way his heart hammers behind his ribcage, how his eyes will flicker everywhere and he tenses all over -Puffing out that fur you seem to love- before he's floating in his own Eden.

Do you like to touch Belo simply because he's, as you put it, "fluffy"? Do you enjoy touching him because you seek to reward him? Do you touch him because you think he should be the only one who gets to receive that privilege?

Selfishly, he silently wishes you'd touch him more. Many, unfortunately, were the times Belo would get distracted throughout the day, daydreaming of you running your hands all over him, unhindered by his outfit, feeling everything everywhere just because you could, because he's your angel and his body is also yours to keep, to order. The blood in his body would rush elsewhere and the celestial would curve to hide his own shame, even as it continued to throb and demand attention until he succumbed.

Pervertedly, Belo did such an experiment once. He dressed casually. It felt wrong, felt inappropriate to present in such a relaxed manner around the most important figure in his life... But you had expressed delight in his supposed drive to adapt a little bit more, so the guilt was ever so slightly lessened.

That day, there was hardly a limit to your boldness. He remembers you embracing him from behind, arms coming forward to squeeze at his chest and rubbing the soft clumps over his abdomen. The knee-length sports shorts he picked were pushed down slightly. Belo had done it on purpose, and it yielded results. You had, perhaps in distraction, perhaps knowingly, massaged the fur-dense spot right above his slit. The angel couldn't breathe in that moment, he feared he might even collapse if your digits wondered just a tiny bit further. He knew that he would react shamefully but the notion wasn't strong enough to make him prevent such.

He was ready to be punished, if it meant having this small guilty pleasure.

Your phone, that blasted electrical contraption that you love so dearly, rang so jarringly loud in that exact moment that Belo nearly yelped. Your hands were off his overheated body in a blink, and the interaction ceased there, with his Lady none the wiser to the state she left him in.

He could barely feel a shred of indignity for the way disappointment radiated off him in thick waves.

Belo hasn't had the courage to try that again, though it's more than safe to say the memory is engraved in the forefront of his mind.

It got him to... Think about you.

Your actions, your behavior around others.

It's not often you allow people into your sanctuary anymore. Belo insists that you shouldn't invite those beneath you into such close quarters. This ground is pure and protected for the sake of your well-being, to allow ignorant outsiders to disrespect and desecrate this location is an act of self-harm the power will simply not stand by!

Yet still, his Lady's word is final on a lot of matters. There is faith in some people, who you see as good and deserving of your holy presence. The celestial sees naught but lessers in delusion of your supposed "normalcy", but if you believe these individuals are somewhat excusable, then he'll try to see things through your eyes.

You've always tended to keep your distance from them. Not emotionally, physically. This was something Belo was initially quite relieved by, he didn't have to warn you not to put yourself in such unsightly positions. Just the thought made him itch in an unnatural way...

Now though, he wonders why, if you're aware of the distance you should keep from others, you still choose to touch him frequently? Belo is still beneath the honor of such, yet never once do you hold the hands of the people you invite, refuse their embraces, look uncomfortable at the slightest unintentional brush... In contrast, you appear to be greatly comforted by the sensation of his physique.

He freezes, mind running so wild with possibilities that the angel's fingers tremble.

You have clearly made a choice.

There's no one you'd ever like to touch, except Belo.

In your eyes, in your actions, in your mind, he's the only one worthy enough.

He's the only one who can reach your standards!

You only need contact from him.

Belo understands now.

He feels his chest tighten with delight, feels weightless for a second, the rush of euphoria clawing its way up his spine makes his wings flutter and he emits some sort of noise entirely undignified of his cast.

He remained in a state of barely concealed hysteria until you arrived home that day.

For once in his life, he commits something unthinkable.

" Welcome back, my Lady. "

He greets when you step through the door. Instead of standing by your side as he typically does, the angel crowds you, ruffled and tense. You don't get to answer before Belo summons the courage to reach out, to ghost his hands across your soft face and ever so gently, so carefully -like you'd shun him forever otherwise- embrace you in a comforting hug.

He feels as if he broke a thousand rules in one moment alone, but it was worth it.

Because he felt you smile against him.

240 notes

·

View notes

Text

KLAP Translation: Part 3 (Touma)

Touma Rampage

Koyomi: "*sigh*..."

(Staring at the ground while walking isn't gonna help me find the answer though...)

Koyomi: "――Oof."

Hoodlum Student A: "Ouch!"

At the loud voice, I looked up to a student who just radiated "I'm trouble".

Koyomi: "Sorry I wasn't paying attention――"

Hoodlum Student A: “...Tch! You lousy human, what are you doing strutting in the middle of the street! Why don't you go cry in a corner or something?!"

Hoodlum Student B: "Humans sure are an eyesore..."

Koyomi: "......"

Koyomi: (...If these kids were to go into a Rampage――)

Suddenly, the image of that underground dungeon came to mind.

Hoodlum Student C: "...Huh? This thing looks like they're thinking about something?"

Hoodlum Student A: "Huuuuh? You got some nerve thinking of something before me."

Koyomi: "Wah...?! H-Hey! Let go of me!"

Hoodlum Student A: "You bump into me then order me around without even apologizing, huh."

Hoodlum Student A: "But, I'll be generous. If you calmly give me what I ask for, I just might forgive ya."

???: "Let her go, bonehead."

Hoodlum Student A: "Agaaahhhh?!"

Koyomi: "Touma-kun...?!"

The person that held a grasp of me was blown away flying, and the other hoodlums recoiled.

Hoodlum Student B: "Wha... What was that for?!"

Touma: "...ut up.

Next time I see you guys pick a fight with her, your days will be numbered."

Hoodlum Student A: "Mimasaka of the Tengu clan...?! Despite being a UMA, he's watching a human's back...!"

Touma: "Shut your yap, underdog-kun. Or what else?

Do ya want me to put you in a more miserable state?"

Hoodlum Student A: "D...Dammit! I'll get you for this...!!"

After the exchange, the group of UMA hoodlums quickly scattered.

Koyomi: "......"

Touma: "......"

Koyomi: "Uh, Touma-kun. ...Thanks."

Touma: "...Wasn't any big deal. But, you tooー I don't know what you keep dawdling about, but watch where you're walking."

Koyomi: "Yeah..."

Touma: "......"

Touma: "You seem awfully gloomy. Did...something happen?"

OPTIONS

> The lives of UMA must be difficult.

> I can't muster any confidence.

> This world is just too different...

OPTION: The lives of UMA must be difficult.

Koyomi: "For UMA their... lives must be difficult."

Touma: "Huuhhh? What are you talking about?"

Touma: "Also, don't go around and decide how others' lives are. That's just terrible manners."

Koyomi: "S-Sorry...! I wasn't trying to say it like that..."

> OPTION: I can't muster any confidence.

Koyomi: "Yeah… I just kinda lost my confidence there."

Koyomi: "I was just wondering if I am really cut out to be a trainer here at Yomi School...is all."

Touma: "......"

Touma: "...Does that really matter if you aren't confident?"

Touma: "In the first place, aren't you still new? Anyone just brimming with confidence is annoying."

Koyomi: "Touma-kun..."

> OPTION: This world is just too different...

Koyomi: "What may be commonplace in Aima does not apply to the world I am from… Moving forward, I just feel a bit anxious."

Touma: "Huuuuh...? That's what it's about?"

Touma: "But you don't need to be so flustered about it. Everyone here knows you're from the human realm..."

Touma: "You don't have to be so worried about all that."

Koyomi: "You...sure?"

Touma: "*sigh* I don't wanna pry into it but… Can I guess why you're so bummed out?"

Koyomi: "Huh...?"

Touma: "It's 'cause you saw Ryou's Rampage right? Then you got freaked out. 'I can't do this. I'm no good'... You were thinking that right?"

Touma-kun looked straight at me for an answer, and I slowly replied with a nod.

Koyomi: "...Yeah, you're right."

Touma: "Wah! So stupidーYou don't need to be so hung up about it."

Koyomi: "...! B-But I..."

Touma: "No, it's stupid."

Touma: "Just like how humans can't fly or live for hundreds of years, we have our own conditions, when met, that causes Rampage..."

Touma: "That's all it is, isn't it?"

Touma: "You may not like this reality, but our abilities have nothing to do with what's impossible and what isn't. That's just what we are as 'UMA'."

Koyomi: "......"

Touma: "...A-Ahhh... So what I'm saying is, it's not worth your time overthinking it all, you just gotta do what you can sometimes."

Koyomi: "...Touma-kun are you――"

Touma: "...Huh?"

Koyomi: "Touma-kun, are you not scared? If you were to go into a Rampage yourself."

Touma: "......"

Touma: "...When that time comes, I'm prepared for the worst. I'm a full-fledged member of the Tengu clan."

Touma: "But, it won't change anything if I get freaked out. Because, even if that time comes, I'll fight until the end to maintain myself."

Touma: "If I end up being taken care of by someone else while in Rampage, I'd rather just die."

Touma: "...Besides, you still haven't done any 'training' yourself, right? Then you shouldn't have anything to worry about."

Touma: "By some chance, you might be able to do it well, right?"

Koyomi: "...Yeah, that might be the case."

Touma: "To begin with, there's something I still need to do. If I ever Rampage, I'll beat it with my fighting spirit!"

Koyomi: "F-Fighting spirit..."

I thought that might be a bit of a stretch...

As I saw Touma-kun stick out his chest with dignity, he brimmed with confidence and appeared to be beaming――

If he were to erupt into a Rampage, his fighting spirit is so strong he might actually succeed.

Touma: "*sigh*... I went off and rambled there."

Touma: "Anyway, start acting more like an actual teacher and put on an air like one!"

Koyomi: "Ow ow ow!"

He patted my back hard, and I nearly lost my balance.

Touma: "Haha. I wasn't even hitting you that hard, don't make it such a big ...deal...?"

Koyomi: "...Touma-kun?"

Touma: "Huuuh...?! What...is this...?! My body's...!"

Touma-kun, who was lively just a moment before, suddenly crouched down and started to breathe heavily.

Koyomi: "Wha...What's wrong?! Is it an injury from the quarrel earlier or――!"

While I asked, I peeked towards his face and noticed them.

Koyomi: (His eyes are red――!Don't tell me, Rampage...?!)

Touma: "Guh...Gah...! Damn, what is...this...?!"

A strong wind surged around him. Just like Ryou-kun's Rampage, it was a strange wind which held a force I couldn't see.

Koyomi: "......!"

Even though I was in a state of shock, I instinctively grabbed my training whip. But...!

Koyomi: "I can't do this by myself...!"

Suddenly――

Koyomi: "That's right, the training room...! If I can go there...!"

Touma: "Gwah...Ah...Gaaaaaahh..!!"

During that time, Touma-kun's groans grew more intense, and I held him up in a panic.

Koyomi: "T-Touma-kun...! Just a bit more...! Just hold on a bit more...!"

Let's hurry to the training room, then――

Koyomi: "Touma-kun, I'm sorry...!"

Somehow I was able to prop him up and firmly shackle both his arms to suppress him.

Touma: "Haaa... Haaaa...! This might be turning pretty serious...!"

He seems to be in pain, but he has a sort of captivated look on him.

Koyomi: (I'm the only one here who can save him!)

If I can't help him, what'll be waiting for him is a future of decades in that underground dungeon.

If I don't save him...!

Koyomi: "Just wait, Touma-kun...! I'll save you――!"

[Excluded is mini-whip game]

[Good whip score]

Somehow, after completing my first training, we were both left heavily panting.

Koyomi: "*pant*...*pant*... S-Somehow we were able to suppress the rampage..."

Touma: "*pant*...*pant*... Yeah, somehow..."

I wonder if he feels numb from the restraints? Touma-kun rubbed at his wrists and quietly stood up.

For a while he watched my reaction and looked a bit guilty, then…

Finally he made up his mind, and turned towards me.

Touma: "At any rate, you saved me. Do you...have time after this? I'd like to thank you somehow."

Koyomi: "Eh, I don't need any sort of thanks...! I just did what I could do to help, it's not something you need to worry about..."

Touma: "That applies to me too. I want to help you out for my own sake. So there isn't anything you should worry about."

Touma: "...Again, do you have time?"

He spoke with conviction, and I nodded back, slightly taken aback.

Koyomi: "Y-Yeah... I have time."

Touma: "Then it's decided."

We headed towards a family restaurant located on the main street of Tokoyo Town. I knew it was here, but today is the first time I've been inside.

Koyomi: (It seems like a typical family restaurant...?)

While restlessly looking around, Touma-kun returned from grabbing drinks.

Touma: "Here, Iced tea."

Koyomi: "Thank you. ...So they have family restaurants here too."

Touma: "I hear they serve a variety of food in the human realm here. Are the menus similar too?"

Koyomi: "N-No... I think the menus really different..."

This month's recommendations!

A full course of Panaeolous, Japanese-style pasta:

Fall down holding your stomach, breathing trouble guaranteed! I stared at the words on the poster as I gave my answer. Would I really be okay if I drank this iced tea...?

As I was feeling a bit shaken over it, Touma-kun shyly grumpled out his words.

Touma: "...So, ya know. You really helped me out earlier...thanks."

Touma: "If I had stayed in that Rampage long enough to wipe out my consciousness, I would've been sent to that underground dungeon――that's no joke."

Touma: "So this is to convey my gratitude. Drink as much as you want!"

Koyomi: (Even if he says to drink as much as I like, the restaurant is drink-bar style so it's a free for all either way...)

Well, although I had my doubts, I thanked him for his kindness for the time being.

That day, Touma-kun's impression seemed different than before, like he's become more comfortable――

It wasn't long until we both went to head home, but in that short time, it felt like the distance we had between each other had narrowed.

Koyomi: (Even though I'm unskilled as a teacher and as a trainer… There's still something I can do for these kids...)

I was glad to discover that fact, and smiled to myself as I returned to the streets, dyed sepia in the sunset.

The Next Day.

I reported back to work to the school, and met with Nurarihyon-sensei in the staff room.

Nurarihyon: "Oh, it's you. What is it?"

Koyomi: "Until yesterday, I was asking myself if I could really continue being a trainer at this school but――"

Nurarihyon: "Ah yes, I remember. From your expression...did you find your answer?"

Koyomi: "Yes. I will try my best at this school...!"

It was a small resolution, but a big first step. I have made my first steps forward.

[Bad whip score]

Somehow, after completing my first training, we were both left heavily panting.

Koyomi: "Did...the Rampage somehow calm down?"

Touma: "In exchange, my body's all messed up though."

I finally released Touma-kun from his chains, and was met with a face of complete displeasure.

Koyomi: "I'm sorry... I couldn't do it that well..."

Touma: "Hm... Well, the Rampage subsided at the end... So I guess I should be more or less grateful, thanks."

Koyomi: "Touma-kun..."

What I wanted to be was a teacher, not a trainer...

These encounters are in an unknown world to humans, known as Aima Prefecture.

Principal Nurariyon.

Shion-sensei.

Everyone in class. There was still much I did not understand, and some things I may NEVER understand. However——

Koyomi: (I will try to do all I can here...)

I thought about that as I saw him standing in front of me.

#klap#klap translation#translation#japanese translation#otome#otoge#otome translations#otome translation#kindless love and punishment

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

And now the 5 Acts of Hamlet, the Mad Prince of Denmark, and his rendition of the Cell Block Tango

ALL HAMLETS: He had it comin He had it comin He only had himself to blame If you’d’ve been there If you’d’ve seen it I betcha you would’ve done the same

ACT 3 SCENE 4 HAMLET: You know how people have these little habits that get you down? Like…Polonius Polonius liked to snoop around – no not snoop – spy So I was talking to my mother in her closet, speaking daggers to her but using none And there’s Polonius, behind the arras, crying out for help and snooping – no not snooping – spying And so I said to him, I said: “How now? A rat” And there was. So I took my rapier from its sheath and stabbed through the curtain Dead for a ducat, dead

ALL HAMLETS: He had it comin He had it comin He was a foolish prating knave If you’d’ve been there If you’d’ve heard it I betcha you would’ve done the same

ACT 3 SCENE 1 HAMLET: I met Ophelia in Elsinore about two years ago I could see she was fair, and we hit it off right away So I started sending her letters “Doubt stars are fire Doubt the sun move Doubt truth be liar Never doubt I love” And then I found out. Honest she told me Never believe it! Not only did she return my remembrances, she conspired with my incestuous uncle and her foolish father to spy on me So while I was in the lobby I confronted her, I told her to get herself to a nunnery You know, some girls just can’t handle rejection

ALL HAMLETS: She had it comin She had it comin She was a heartless columbine Because she used me, and she abused me But was it madness or suicide?

ACT 2 SCENE 2 HAMLET: Now I’m moping around the castle, reading some old book, minding my own business, when in comes Rosencrantz and Guildenstern “Were you not sent for?” I said. They were deceiving me! So I kept insisting, “If you love me, hold not off” ACT 5 SCENE 2 HAMLET: They are not near my conscience Their defeat does by their own insinuation grow

ALL HAMLETS: If you’d’ve been there If you’d’ve seen it I betcha you would’ve done the same

ACT 5 SCENE 2 HAMLET That bloody, bawdy villain Remorseless, treacherous, lecherous, kindless villain Mine uncle He killed my father, whored my mother, took my crown He even tried to send me away to England to have my head struck off ere they grind the axe My father’s ghost bade me to revenge his foul and most unnatural murder…

ACT 2 SCENE 2 HAMLET: Yes, but did you do’t?

ACT 5 SCENE 2 HAMLET: Well, eventually

ACT 5 SCENE 1 HAMLET My friend, Horatio and I were hanging out in the graveyard Having a little banter with a gravedigger Now, we were near the last Scene in the final Act, and I was feeling my mortality As I held the skull of poor Yorick, I pondered the inevitable fate of Man with my long-suffering companion And just then a funeral procession came upon us “Soft a while,” I said as we hid ourselves and watched the maimed rites I noted that the corpse did fordo its own life and was of some estate What? The fair Ophelia? And there’s Laertes leaping into my lover’s grave – outfacing me Well, I was in such a state of shock, I completely blacked out, I can’t remember a thing It wasn’t until later, when I was preparing for a duel with Laertes, I realized I leapt in there with him

ALL HAMLETS: He had it comin He had it comin He had it comin all along I didn't do it, but if I'd done it How could you tell me that I was wrong?

He had it comin He had it comin He had it comin all along (Pardon me, sir, I’ve done you wrong) I didn't do it, but if I'd done it (I am but punished, with sore distraction) How could you tell me that I was wrong?

HAMLET: I loathe myself more than I can possibly say My father was a paragon of man, Hyperion, now a ghost I swore for him a swift revenge But by some craven scruple I lapsed And in my dullness Sent poor Polonius and Ophelia to their graves I guess you could say I failed in every possible way My life isn’t worth a pin’s fee I’m better off dead

ALL HAMLETS: A peasant slave, slave, slave, slave, slave! A peasant slave, slave, slave, slave, slave!

I had it comin I had it comin I had it comin all along I feel the augur Yet I defy it I say the readiness is all

We had it comin We had it comin We only have ourselves to blame If you’d’ve been there If you’d’ve seen it I betcha you would’ve done the same

#hamlet#shakespeare#yall this took an embarrassingly long time to put together lol#i had sooooo much trouble with that final verse#i still don't feel like its good enough#this is obviously written with the assumption that Hamlet truly went mad#personally i disagree with that interpretation#but this was just too fun to imagine

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

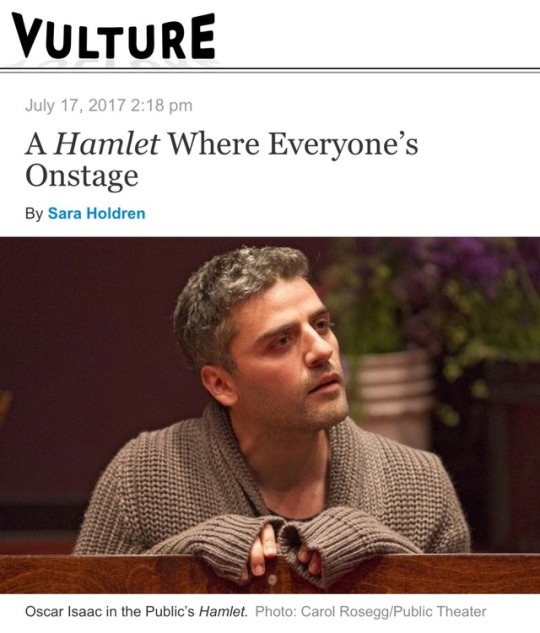

A little over a third of the way into the modestly dressed, disarmingly brilliant production of Hamlet now playing at the Public, Oscar Isaac as the iconic prince turns to us before one of his famous soliloquies and calmly tells us, “Now I am alone.”

I caught my breath at these four words. They were not a statement of fact — they were an invitation to the audience to imagine.

Not every Hamlet calls attention to its own theatricality. This Hamlet — beginning with its use of the company onstage as a second audience, a mirror for us out in the seats — engages us in a game that makes us contemplate the very nature of performing. When Oscar Isaac tells us, still surrounded by his fellow actors, “I am alone,” he is not describing but instructing. He is working on our imaginary forces — or, as he might say, our mind’s eye — telling us, These are the rules of this game. Come, play.

It is a mark of this production’s intelligence that its rules are inscribed in its aesthetic from the very beginning by a set of design choices that blur the line between audience and stage. The Anspacher is a strange space: a thrust configuration — which is Shakespearean enough — but surrounded by raked banks of red upholstered seats that come from an entirely different era of spectatorship. Hamlet’s set (by David Zinn), like the production itself, is unassuming and very, very smart: It extends the feel of the seating banks by covering the whole stage in red carpet. The chairs used onstage are a match to those in the front rows of the audience: modern, institutional, more red upholstery. Hanging above the playing space are additional house lights mimicking those above the audience (these the domain of lighting designer Mark Barton, whose work is a subtle, powerful complement to Zinn’s).

The main playing area — apart from the chairs and a table that looks like it could have been pulled from one of the Public’s conference rooms — is empty. The back wall is unadorned. Props are few and almost all present at the back of the stage at the show’s beginning, waiting for eventual use. There is a station for a musician (the incredible Ernst Reijseger) who creates the entirety of the production’s sonic landscape on a cello and a set of wooden pipes that play like an eerie organ. Each actor has only one costume, and if designer Kaye Voyce has not pulled directly from the actors’ own closets, she has quietly and cleverly curated a palette that feels as if she has done so. Director Sam Gold and his team of designers seem to have constructed their world in alignment with Hamlet’s advice to the Players:

--- …O’erstep not the modesty of nature: for any thing so overdone is from the purpose of playing, whose end, both at the first and now, was and is, to hold, as ‘twere, the mirror up to nature; to show virtue her own feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure. ---

The actors likewise adhere to these instructions: Their attack on the language is clear and often conversational. They carry us deftly through the poetry without bluster or bravado — we follow the threads of their thought, and when great emotion flows it flows naturally, from a wellspring of grief or rage or shame that feels real.

Real. Ay, there’s the rub. Nothing onstage in this Hamlet is “theatrical” in the way that we have come to understand the term — as a synonym for spectacular, outlandish, or exaggerated. Rather, Sam Gold and his company are interested in a different and perhaps deeper definition of theatricality: Their Hamlet is playing a game with our notions of real and pretend, of sincerity and falseness. After all, you might think that by following Hamlet’s advice to the Players you could simply end up with a realistic TV drama — but Hamlet isn’t asking for realism, he’s asking for truth. He’s asking for honesty wrapped in the artifice of play. The heart of Gold’s production — and its genius — lies in its obsession with the paradox of the Honest Performance.

Hamlet insists that he ���know[s] not ‘seems.,” but any good actor will tell you that you can feel all day long, but without seeming — without the show of that feeling — there’s no play. And Hamlet, the character, is a good actor. (This Hamlet, in the person of Oscar Isaac, at once mischievous and deeply soulful, is exceedingly good.) Part of the character’s tragedy is that he is a thoughtful comedian trapped in the bloody, archaic genre of the Revenge Play, forced into playing a role his very nature abhors. Imagine if Othello or Hotspur had been Old Hamlet’s son. Claudius would be dead and young Fortinbras defeated by Act 2, Scene 1.

Gold’s production dispenses with Fortinbras and with all references to any wider political conflict. (In interviews, he and Isaac have repeatedly described the show as “intimate.”) It’s a vision of a Hamlet in which the wider world is not Scandinavia but the theater. The company’s members are aware on some deep level of their existence both as actors and as characters in a play. Keegan-Michael Key (who makes a charming Horatio) begins the performance with a casual, endearingly silly curtain speech to the audience, but this is no mere lark: It introduces us to Horatio as a kind of narrator, a role that he will return to with much more gravity when, at the play’s end, he assumes responsibility for telling Hamlet’s story. He even adopts one of Fortinbras’s lines at the finale — “[Let] these bodies / High on a stage be placed to the view” — and when he says it, we hear not a dictator organizing a military funeral but a stage manager preparing for a literal eternity of performances of Hamlet.

In cautioning Ophelia not to trust Hamlet’s declarations of love, Laertes shows a similar subliminal awareness of the play-world he inhabits. He warns his sister that Hamlet “may not, as unvalued persons do, / Carve for himself, for on his choice depends / The safety and health of this whole state.” By “whole state” he typically means Denmark, but in this production Laertes (the compelling Anatol Yusef) gestures to us, the audience, and around the room at the chairs, the table, the lighting grid. Laertes is warning his sister, This story depends on him, and there’s only one way it can go. Likewise, when plotting to send Hamlet to England, Claudius (the superb Ritchie Coster) growls that he can’t outright punish his troublesome stepson, because “he’s loved of the distracted multitude.” Those last two words can only mean us. We, the audience, love Hamlet, and our imaginary forces hold sway in this room; Claudius, Laertes, and the rest of this ensemble maintain an understated awareness that they are acting in Hamlet’s play. This is not nudge-nudge-wink-wink mugging; the actors are not nodding their heads at us and mouthing, as Hamlet might have it, “Well, well we know.” A showier self-consciousness of theatrical artifice is fairly common on the stage these days. There is something subtler at work here — an investigation of the paradoxical alchemy of sincerity and deceit that lies at the heart of Hamlet and of theater itself.

The layers of this theatrical onion are further multiplied by the fact that the nine-person company of players doubles as … the Company of Players. By limiting the number of bodies onstage and letting each one accumulate valences of meaning, Gold sounds Shakespeare’s play like a great resonant bell. Seeing the Player King/Player Queen scene played out in the bodies of Gertrude and Claudius (who is also the ghost of Old Hamlet) is a revelation: Often delivered with self-conscious puffy artifice, here the scene feels like a moment out of time, like watching Hamlet witness a moment that might truly have taken place between his mother and his sickly father. And the Player King’s warning to his Queen — that she won’t be able to keep her vows never to remarry — rings with pathos and prophecy: “Our thoughts are ours, their ends none of our own.” So says this false king — this actor — prefiguring Hamlet’s recognition of the “divinity that shapes our ends” and summing up in a single line the tragedy of the prince’s character. What is Hamlet if not a creature of thought, doomed to an end none of his own?

Or take the doubling of Laertes and the Lead Player, who enters into a friendly competition with Hamlet over their shared delivery of the great Pyrrhus speech. The Player astounds Hamlet with his ability to “force his soul so to his own conceit” — he can make himself weep on cue! “For nothing! For Hecuba!” — which drives Hamlet to the frenzied contemplation of his own inaction. By this point, the Hamlet who could clearly separate performance from substance is gone: He now longs to act in all senses of the word, even if it means conflating those senses. In attempting to follow the Player’s example, Hamlet substitutes performance for the real action he so craves (and fears), winding up screaming melodramatically into the winds (“Remorseless, treacherous, lecherous, kindless villain! / O, vengeance!”) and, here, doing great violence to a dish of lasagna. No wonder Isaac looks up afterwards — the clown who tried to play the avenger — and cracks a wry, abashed smile: “Why, what an ass am I!”

Though Hamlet knows in his most lucid moments that the performance of a thing is not the thing itself, he remains obsessed with the enactment of his own feelings, as if performing them paradoxically proves their honesty. When this Hamlet confronts Laertes at Ophelia’s grave (“What is he whose grief / Bears such an emphasis?”), we have already seen these two men compete in the performance of grief. First, it was for Hecuba, a mere fantasy, a play. Now, it is for Ophelia, a real woman whom they both loved. Laertes and Hamlet are both wracked by real anguish, and they are also playing at it: Who loved her more? Who can mourn her better? It’s a wrenching thing to watch — who among us has not felt something deeply and simultaneously felt ourselves performing the feeling? Acting is in our nature; we long to be witnessed.

Is such ore always there for the mining in this scene between the grieving lover and the grieving brother? Yes. But does every Hamlet mine it? No. It is the mark of a deeply intelligent production when it makes you hear anew a work encrusted with so many barnacles of historical, literary, and theatrical precedent.

They don’t call it “Poem Unlimited” for nothing. The glory of Hamlet is its unsoundable depth. Another director with another production might strike its great bell from a slightly different angle and produce completely different resonances. Another director might be as fascinated by kingship, war, and affairs of state as Sam Gold is by layers of theatricality. Still, while Gold might have stripped the play of its original political context, this “intimate” production has not been stripped of politics. Its seeming domesticity is deceptive; it has something pointed to say about the political state of our world, but its tool is a needle, not a bludgeon. By its indirections, we find directions out.

“Ay sir,” quips Hamlet to Polonius, “to be honest, as this world goes, is to be one man picked out of ten thousand.” It’s a great line, always, but at this moment I heard it cut the air with a new sharpness. That word, honest, rings out over and over in this production. The politics of this Hamlet is a politics of performance, of being and seeming, of sincerity and hypocrisy, truth and corruption. In this way, Gold’s production may well be an abstract and brief chronicle for our time. After all, how many of our highest politicians might currently be asking themselves, “May one be pardoned and retain the offence?”

Hamlet is at the Public Theater through September 3.

###

@poe-also-bucky

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Hamlet Where Everyone’s Onstage

A little over a third of the way into the modestly dressed, disarmingly brilliant production of Hamlet now playing at the Public, Oscar Isaac as the iconic prince turns to us before one of his famous soliloquies and calmly tells us, “Now I am alone.”

I caught my breath at these four words. They were not a statement of fact — they were an invitation to the audience to imagine.

Isaac was not alone, not in this moment nor ever. Hamlet as written contains seven soliloquies, but the Hamlet who is now wrestling with his fate on the red-carpeted boards of the Anspacher Theater is never a solo figure: He always has an audience. During each soliloquy, members of the ensemble sit or stand strewn about the stage, still present, giving their prince a quiet, serious attention — a company of players, watching and listening.

Not every Hamlet calls attention to its own theatricality. This Hamlet — beginning with its use of the company onstage as a second audience, a mirror for us out in the seats — engages us in a game that makes us contemplate the very nature of performing. When Oscar Isaac tells us, still surrounded by his fellow actors, “I am alone,” he is not describing but instructing. He is working on our imaginary forces — or, as he might say, our mind’s eye — telling us, These are the rules of this game. Come, play.

It is a mark of this production’s intelligence that its rules are inscribed in its aesthetic from the very beginning by a set of design choices that blur the line between audience and stage. The Anspacher is a strange space: a thrust configuration — which is Shakespearean enough — but surrounded by raked banks of red upholstered seats that come from an entirely different era of spectatorship. Hamlet’s set (by David Zinn), like the production itself, is unassuming and very, very smart: It extends the feel of the seating banks by covering the whole stage in red carpet. The chairs used onstage are a match to those in the front rows of the audience: modern, institutional, more red upholstery. Hanging above the playing space are additional house lights mimicking those above the audience (these the domain of lighting designer Mark Barton, whose work is a subtle, powerful complement to Zinn’s).

The main playing area — apart from the chairs and a table that looks like it could have been pulled from one of the Public’s conference rooms — is empty. The back wall is unadorned. Props are few and almost all present at the back of the stage at the show’s beginning, waiting for eventual use. There is a station for a musician (the incredible Ernst Reijseger) who creates the entirety of the production’s sonic landscape on a cello and a set of wooden pipes that play like an eerie organ. Each actor has only one costume, and if designer Kaye Voyce has not pulled directly from the actors’ own closets, she has quietly and cleverly curated a palette that feels as if she has done so. Director Sam Gold and his team of designers seem to have constructed their world in alignment with Hamlet’s advice to the Players:

…O’erstep not the modesty of nature: for any thing so overdone is from the purpose of playing, whose end, both at the first and now, was and is, to hold, as ‘twere, the mirror up to nature; to show virtue her own feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure.

The actors likewise adhere to these instructions: Their attack on the language is clear and often conversational. They carry us deftly through the poetry without bluster or bravado — we follow the threads of their thought, and when great emotion flows it flows naturally, from a wellspring of grief or rage or shame that feels real.

Real. Ay, there’s the rub. Nothing onstage in this Hamlet is “theatrical” in the way that we have come to understand the term — as a synonym for spectacular, outlandish, or exaggerated. Rather, Sam Gold and his company are interested in a different and perhaps deeper definition of theatricality: Their Hamlet is playing a game with our notions of real and pretend, of sincerity and falseness. After all, you might think that by following Hamlet’s advice to the Players you could simply end up with a realistic TV drama — but Hamlet isn’t asking for realism, he’s asking for truth. He’s asking for honesty wrapped in the artifice of play. The heart of Gold’s production — and its genius — lies in its obsession with the paradox of the Honest Performance.

Hamlet insists that he “know[s] not ‘seems.,” but any good actor will tell you that you can feel all day long, but without seeming — without the show of that feeling — there’s no play. And Hamlet, the character, is a good actor. (This Hamlet, in the person of Oscar Isaac, at once mischievous and deeply soulful, is exceedingly good.) Part of the character’s tragedy is that he is a thoughtful comedian trapped in the bloody, archaic genre of the Revenge Play, forced into playing a role his very nature abhors. Imagine if Othello or Hotspur had been Old Hamlet’s son. Claudius would be dead and young Fortinbras defeated by Act 2, Scene 1.

Gold’s production dispenses with Fortinbras and with all references to any wider political conflict. (In interviews, he and Isaac have repeatedly described the show as “intimate.”) It’s a vision of a Hamlet in which the wider world is not Scandinavia but the theater. The company’s members are aware on some deep level of their existence both as actors and as characters in a play. Keegan-Michael Key (who makes a charming Horatio) begins the performance with a casual, endearingly silly curtain speech to the audience, but this is no mere lark: It introduces us to Horatio as a kind of narrator, a role that he will return to with much more gravity when, at the play’s end, he assumes responsibility for telling Hamlet’s story. He even adopts one of Fortinbras’s lines at the finale — “[Let] these bodies / High on a stage be placed to the view” — and when he says it, we hear not a dictator organizing a military funeral but a stage manager preparing for a literal eternity of performances of Hamlet.

In cautioning Ophelia not to trust Hamlet’s declarations of love, Laertes shows a similar subliminal awareness of the play-world he inhabits. He warns his sister that Hamlet “may not, as unvalued persons do, / Carve for himself, for on his choice depends / The safety and health of this whole state.” By “whole state” he typically means Denmark, but in this production Laertes (the compelling Anatol Yusef) gestures to us, the audience, and around the room at the chairs, the table, the lighting grid. Laertes is warning his sister, This story depends on him, and there’s only one way it can go. Likewise, when plotting to send Hamlet to England, Claudius (the superb Ritchie Coster) growls that he can’t outright punish his troublesome stepson, because “he’s loved of the distracted multitude.” Those last two words can only mean us. We, the audience, love Hamlet, and our imaginary forces hold sway in this room; Claudius, Laertes, and the rest of this ensemble maintain an understated awareness that they are acting in Hamlet’s play. This is not nudge-nudge-wink-wink mugging; the actors are not nodding their heads at us and mouthing, as Hamlet might have it, “Well, well we know.” A showier self-consciousness of theatrical artifice is fairly common on the stage these days. There is something subtler at work here — an investigation of the paradoxical alchemy of sincerity and deceit that lies at the heart of Hamlet and of theater itself.

The layers of this theatrical onion are further multiplied by the fact that the nine-person company of players doubles as … the Company of Players. By limiting the number of bodies onstage and letting each one accumulate valences of meaning, Gold sounds Shakespeare’s play like a great resonant bell. Seeing the Player King/Player Queen scene played out in the bodies of Gertrude and Claudius (who is also the ghost of Old Hamlet) is a revelation: Often delivered with self-conscious puffy artifice, here the scene feels like a moment out of time, like watching Hamlet witness a moment that might truly have taken place between his mother and his sickly father. And the Player King’s warning to his Queen — that she won’t be able to keep her vows never to remarry — rings with pathos and prophecy: “Our thoughts are ours, their ends none of our own.” So says this false king — this actor — prefiguring Hamlet’s recognition of the “divinity that shapes our ends” and summing up in a single line the tragedy of the prince’s character. What is Hamlet if not a creature of thought, doomed to an end none of his own?

Or take the doubling of Laertes and the Lead Player, who enters into a friendly competition with Hamlet over their shared delivery of the great Pyrrhus speech. The Player astounds Hamlet with his ability to “force his soul so to his own conceit” — he can make himself weep on cue! “For nothing! For Hecuba!” — which drives Hamlet to the frenzied contemplation of his own inaction. By this point, the Hamlet who could clearly separate performance from substance is gone: He now longs to act in all senses of the word, even if it means conflating those senses. In attempting to follow the Player’s example, Hamlet substitutes performance for the real action he so craves (and fears), winding up screaming melodramatically into the winds (“Remorseless, treacherous, lecherous, kindless villain! / O, vengeance!”) and, here, doing great violence to a dish of lasagna. No wonder Isaac looks up afterwards — the clown who tried to play the avenger — and cracks a wry, abashed smile: “Why, what an ass am I!”

Though Hamlet knows in his most lucid moments that the performance of a thing is not the thing itself, he remains obsessed with the enactment of his own feelings, as if performing them paradoxically proves their honesty. When this Hamlet confronts Laertes at Ophelia’s grave (“What is he whose grief / Bears such an emphasis?”), we have already seen these two men compete in the performance of grief. First, it was for Hecuba, a mere fantasy, a play. Now, it is for Ophelia, a real woman whom they both loved. Laertes and Hamlet are both wracked by real anguish, and they are also playing at it: Who loved her more? Who can mourn her better? It’s a wrenching thing to watch — who among us has not felt something deeply and simultaneously felt ourselves performing the feeling? Acting is in our nature; we long to be witnessed.

Is such ore always there for the mining in this scene between the grieving lover and the grieving brother? Yes. But does every Hamlet mine it? No. It is the mark of a deeply intelligent production when it makes you hear anew a work encrusted with so many barnacles of historical, literary, and theatrical precedent.

They don’t call it “Poem Unlimited” for nothing. The glory of Hamlet is its unsoundable depth. Another director with another production might strike its great bell from a slightly different angle and produce completely different resonances. Another director might be as fascinated by kingship, war, and affairs of state as Sam Gold is by layers of theatricality. Still, while Gold might have stripped the play of its original political context, this “intimate” production has not been stripped of politics. Its seeming domesticity is deceptive; it has something pointed to say about the political state of our world, but its tool is a needle, not a bludgeon. By its indirections, we find directions out.

“Ay sir,” quips Hamlet to Polonius, “to be honest, as this world goes, is to be one man picked out of ten thousand.” It’s a great line, always, but at this moment I heard it cut the air with a new sharpness. That word, honest, rings out over and over in this production. The politics of this Hamlet is a politics of performance, of being and seeming, of sincerity and hypocrisy, truth and corruption. In this way, Gold’s production may well be an abstract and brief chronicle for our time. After all, how many of our highest politicians might currently be asking themselves, “May one be pardoned and retain the offence?”

Source

5 notes

·

View notes