#khoisan

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

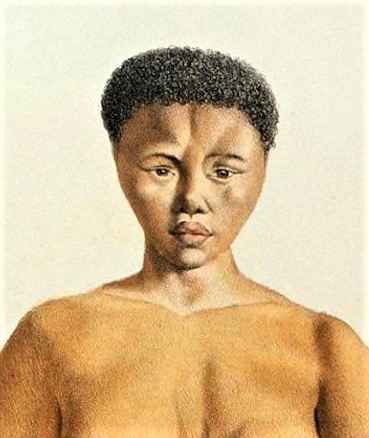

Sara Baartman (1789–1815), also known as Saartjie Baartman, was a Khoisan woman from South Africa who became a symbol of exploitation and racial discrimination. Born in the Eastern Cape, she was a member of the Khoikhoi people. Baartman was taken to Europe under false pretences in 1810, lured by promises of wealth and a better life. Instead, she became the subject of public exhibition due to her physical features, particularly her large hips and buttocks, which European audiences regarded with a mix of fascination and derision.

In England and later France, she was displayed as part of "freak shows" and referred to as the "Hottentot Venus," a derogatory term that reflected the racist and colonial attitudes of the time. Her body was objectified and subjected to pseudoscientific scrutiny, particularly by French naturalists, who used her as a case study to perpetuate racist theories of human inferiority.

Sara Baartman died in Paris on December 29, 1815, at the age of 26, likely from pneumonia, smallpox, or syphilis. After her death, her body was dissected, and her remains, including her skeleton and preserved genitals, were displayed in French museums for over a century.

In 2002, following years of advocacy and recognition of the inhumanity she suffered, her remains were repatriated to South Africa and given a proper burial in the Eastern Cape, marking a symbolic act of restitution and respect for her legacy. Today, Sara Baartman is remembered as a tragic victim of colonial exploitation and a symbol of the struggle against racism and dehumanization.🇿🇦

#black people#black history#blacktumblr#black#black tumblr#pan africanism#black conscious#africa#south africa#Sara Baartman#Saartjie Baartman#HottentotVenus#Colonial Exploitation#human rights#anti blackness#khoisan#protect black women#repatriation#body autonomy

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Katrina Esau (87) is the last remaining South African who can speak the ancient Khoisan San language N|uu, which is said to be 25 000 years old.

Last month she published a children’s book in her mother tongue, titled '!Qhoi n|a Tjhoi' ('Tortoise & Ostrich'/'Skilpad en Volstruis').

Congratulations Katrina. 🥰😍

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#africans#brownskin#brown skin#afrakans#african culture#Khoi#Khoisan#south africa

399 notes

·

View notes

Text

#south africa#khoisan#san#indigenous#indigenous african#black folks#afrikaner#afrikaners#first inhabitants#black history#african history#white folks#erasure#debating blackness#lmsu

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hunting Partners

A desert huntsman scans for prey atop a sand dune with his loyal Velociraptor partner by his side. Equipped with a keen sense of smell and vision, the little feathered theropod comes in handy as a paravian bloodhound.

The hunter's appearance and weaponry are of course inspired by the San people (or Bushmen) of the Kalahari Desert in southwestern Africa.

#fantasy#velociraptor#dinosaur#prehistoric#bushman#khoisan#african#black man#dark skin#bipoc#tribal#hunter-gatherer#digital art#art

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kaggen, the divine mantis. Kaggen was never born, but rather had existed since the beginning. The deity gave rise to all things that existed, without tools or action Kaggen created all things, from the earth to the Fauna that walked across it. Kaggen is a shapeshifter, most commonly taking the form of a praying mantis but is known to transform into a caterpillar and especially a bull eland. At first Humans and beasts alike lived together in harmony with Kaggen beneath the earth. Kaggen however wished for the creatures to live upon the surface, so he created a tree whose branches stretched across the universe. At the base of the tree Kaggen dug a hole to the land within the earth, and one by one helped the creatures out of the hole. When they all stood upon the surface Kaggen told the world’s animals to live in peace with each other, but Kaggen pulled the humans aside and told them to not light any fires or else risk catastrophe. However as the sun fell across the horizon, night fell. The humans could no longer see in the dark nor could they keep their warmth with fur like the other animals, because of this the humans quickly feared the night and in their desperation they lit a fire to bring light and warmth. But the human’s companions, became frightened by the flames, the beasts running away and severing their once close bond. With his wife, the Hyrax goddess Coti, Kaggen fathered two sons, Cogaz and Gewi. Together with Coti, Kaggen created his prized creation, the Eland. Kaggen greatly cared for the Eland, showering it with love and affection. But when Cogaz and Gewi were out hunting, they accidentally killed the Eland. Infuriated, Kaggen had his sons stir the Eland’s blood in a pot, but when its blood spilled out it became snakes. Because of their mistake, when the brothers spread the blood, it instead formed Hartebeests. Finally Kaggen asked his wife Coti to churn the pot, with Coti adding the fat from the dead Eland into the concoction as well. Now when the family dumped the blood onto the ground, it successfully revived the dead Eland into a lively and plentiful heard, made to bring meat and sustenance to Kaggen’s people. On the surface world, Kaggen regularly combated the destroyer, Gauna, a malicious entity who lead the spirits of death. After a normal victory against Gauna, Kaggen found a lost child, that child was Xo the porcupine, daughter of Gauna. Kaggen pitied the poor abandoned child, adopting her into his family. One day while Kaggen was walking home, the sun set behind him, ushering the world into night. But Kaggen grew irritated each time he stumbled and tripped in the darkness, so in frustration he grabbed his sandal and chucked it into the sky. Kaggen then used his powers to have his sandal lighten the dark sky. After the countless years of living with humanity, the people began to take Kaggen for granted, forgoing his teachings and refusing to recognize his protection over them. In response Kaggen gathered his family and retreated to the sky, with Gauna introducing death to the once immortal earth.

Worshipped among the San of Southern Africa, Kaggen is universally depicted as a shapeshifter. Kaggen is most commonly seen as a praying mantis, but can also transform into a caterpillar, Vulture, Louse, and especially an Eland. The Eland has always been an extremely important animal to the San people and even the rest of the Kalahari peoples of South Africa. The Eland was a major food source among the pastoralists, their abundance making them a consistent source of nourishment, leading to them gaining an important role among the hunter-gatherer societies. The San are the oldest still living culture in the world, with Kaggen likely being one of the oldest known gods. Though the San have been able to trace their origins back 200,000 years, the worship of Kaggen among them is unclear. Many of Kaggen’s attributes and aspects are prolific among the San’s rock art, especially the Eland which likely signifies Kaggen’s presence in the religious landscape. Kaggen goes by numerous names and titles, like Cagn, Kaang, Thora, and Karab. Kaggen is well known as a trickster god, many of his stories have him outwitting or outwitted by others. Though the omnipotent creator god, in his earthly incarnation Kaggen is susceptible to many such hardships. Kaggen, in his role as a trickster god, is capable of being both selfish and selfless, two competing personalities that both punish and reward those who interact with him. This darker more destructive persona could be represented in Gauna, Kaggen’s counterpart. Another such manifestation of Kaggen is Kho the moon, though the two are treated as one and same unlike the differences between Kaggen and Gauna. In the role of a moon god, Kaggen brings about death or Gauna after a hare deceived the humans with Kaggen’s message. Kaggen is one of the many African supreme gods, correlating with the Dogon Amma, the Akan Nyame, the Yoruban Olorun and the Egyptian Ra among many others. As ancient as Kaggen is, he may have given rise to some of these gods. Kaggen holds cognates with his neighboring gods like the Khoekhoe Tsui’goab, the Naron Gauwa and and the Damaran Gamab.

#art#character design#mythology#deity#creature design#kaggen#kaang#cagn#african mythology#san mythology#kalahari#khoisan#creator god#trickster god#animal god#culture hero#praying mantis#mantis god#antelope#eland god#insect god#supreme god#indigenous

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sarwa boy playing the guitar

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Like other Khoisan ex-convicts in Van Diemen’s Land, Witnalder had no means by which he could return home. He was destitute after being discharged from the convict system and became an object of ridicule to certain elements within the local populace. On 10 September 1862, he was before the bench on yet another charge of disturbing the peace. The Police Superintendent told the bench that Witnalder was ‘constantly insulted by idle boys’. Another witness, Mr Jones, said that he had seen Witnalder ‘insulted by mischievous boys’. Despite such evidence of bullying, the Stipendary Magistrate found the prisoner guilty and fined him 1 shilling. Superintendent Propsting took pity on the man and immediately paid the fine, kindly preventing Witnalder being returned to prison (from which he had only recently been released) for defaulting. Following a similar incident in early December 1862, Witnalder appeared before the bench to answer another charge of disturbing the peace. The ‘eccentric little Kaffir, well-known for his military peculiarities’ told the court that some boys had annoyed him thus causing the fracas. Provocation was not considered sufficient mitigation of his alleged crime. Witnalder was fined 10 shillings and costs, and was required to serve fourteen days in prison if he failed to come up with the money. Several weeks later, on 23 December 1862, Witnalder appeared before the Stipendary Magistrate AB Jones Esq, and Captain Bateman at the Police Court along with a 14-year-old boy, William (or Henry as his name was also reported) Collard. Both were charged with committing an ‘unnatural offence’ and were committed to face trial. The prisoners spent Christmas 1862 in gaol waiting to learn their respective fates. Witnalder and Collard (now referred to as Cornwall Collins) stood trial on Wednesday 28 January in the Supreme Court before the Chief Justice, Sir Valentine Fleming. In keeping with the sensibilities of the time, the newspapers reporting the case found the details to be ‘quite unfit for publication’. Nevertheless, the boy had legal representation and much was made in evidence over whether the boy’s mouth had been covered by Witnalder as the ‘unnatural offence’ (sodomy) was being committed. It was found that the boy had allegedly been silenced by the other prisoner, Witnalder, and was therefore a victim rather than a co-conspirator. The police constable was reprimanded for withholding this crucial evidence from the court. Collard was found not guilty, but retained in custody to bear witness against the older man. He was then sworn in, and tearfully gave evidence that he had been assaulted by Witnalder and had not consented to the man’s attentions. The boy’s ordeal in the stand lasted an hour, following which other witnesses were called. The jury retired for only ten minutes before returning a ‘guilty’ verdict. Witnalder once again faced the extreme penalty of the law.

On Thursday 5 February 1863, the Executive Council met and considered Witnalder’s case. It resolved that the death penalty would be carried into effect. Some members of the public expressed outrage (albeit muted because of the nature of the prisoner’s alleged offence). The local Hobart newspaper implored ‘the Councillors of the Governor with whom rests the prerogative of mercy, to weigh well all the circumstances’. A submission from an unnamed advocate was reprinted in the Mercury’s columns, comparing Witnalder’s predicament with Summers who after being convicted of sodomy in July 1862 had his death sentence commuted to transportation for life. Summers, the writer contended, had been in ‘full possession of his senses’. The injustice in upholding the death sentence upon Witnalder, a man ‘little better than a savage’ was made apparent: ‘Summers is surely more responsible than this half tamed brute. And as Summers was not hung, will not the sacrifice of Whitnalder’s [sic] life be a Judicial or rather an Executive Murder?’ The appeal failed, and several days later the Mercury reported that Summer’s case had ‘special circumstances’ which did not apply to Witnalder’s. The reading public was assured that despite the public deploring the application of the death penalty, the Executive had considered all facets of Witnalder’s case in minute detail before deciding to uphold his sentence. The under-sheriff visited Witnalder at the Hobart Town Gaol to read the warrant for his execution. While there, he found the Protestant prisoner mistakenly had been attended by the Roman Catholic clergy since being condemned. On Friday 20 February 1863, Witnalder was roused from his cell at three thirty to prepare for death. He was joined by the Reverend Mr Hunter, who guided him in prayer. By eight that morning, a small crowd comprising the under-sheriff, keeper and under-keeper of the gaol, eight police constables and their sub-inspector, and reporters from the daily newspapers had assembled at the gaol. The only other witness was a Mr Lowe from Victoria. Witnalder emerged from his cell in Hunter’s company, the prisoner’s arms pinioned at his sides. The prayerful men were followed by the executioner. Because of Witnalder’s diminutive size, heavy weights were attached to his feet so he would not suffer more than was necessary. Witnalder ‘saluted’ the onlookers with ‘an abrupt bow’, before the cap was drawn over his head, the noose adjusted, and the flooring removed from under his feet. He was said to have died easily, and had asked Hunter to tell those gathered that he was innocent of the crime for which he had suffered." - Kristyn Harman, Aboriginal Convicts: Australian, Khoisan and Māori Exiles. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2012. p. 188-192.

#khoisan#new south wales#penal colony#convict transportation#carceral islands#settler colonialism#settler colonialism in australia#british empire#academic quote#australian history#south african history#indigenous people#aboriginal australian#aboriginal convicts#history of crime and punishment#reading 2024#death sentence#sentenced to be hanged#ex-convicts

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

"This film focuses on the uncertainties and inhumane acts of police and state brutality faced by the predominantly Rastafarian, KhoiSan identifying community of Hangberg in Cape Town, South Africa."

watched a few minutes, heartbreaking but captivating. this guy speaks such strong truths. I didn't know the realities of communities living in Cape Town. Such beautiful mountains and the sea right next to them, yet such strong oppression pushing itself in between. recommending for a dinner watch or something

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

instagram

0 notes

Text

instagram

The San people also have the epithetic fold of the Asian eye - they have genetic features of all the world’s people.

0 notes

Text

#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#africans#brownskin#brown skin#afrakans#african culture#botswana#Khoi#khoisan#San

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

“What actually happened to all those vanished Khoisan populations? We don’t know. All we can say for sure is that, in places where Khoisan peoples had lived for perhaps tens of thousands of years, there are now Bantu. We can only venture a guess, by analogy with witnessed events in modern times when steel-toting white farmers collided with stone tool–using hunter-gatherers of Aboriginal Australia and Indian California. There, we know that hunter-gatherers were rapidly eliminated in a combination of ways: they were driven out, men were killed or enslaved, women were appropriated as wives, and both sexes became infected with epidemics of the farmers’ diseases. An example of such a disease in Africa is malaria, which is borne by mosquitoes that breed around farmers’ villages, and to which the invading Bantu had already developed genetic resistance but Khoisan hunter-gatherers probably had not.” — Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies by Jared Diamond

1 note

·

View note

Link

Sarah Baartman was Khoisan sold into Slavery and exploited in European sideshows; Some Hip Hop Artists are doing the same thing today; Dinknesh (Lucy) 3.2 million years old, Free Masonry and Ancient Kemet (Egypt), Bastet from Kemet (Egypt) inspired the Panther Deity 'Bast' in 'Black Panther'; Auset/Isis, The Black Madonna & Child was worshiped in Europe - Michael Imhotep (Next Class is Sat. 8-15-23, 2pm EST - Register Now) REGISTER NOW: Next Class Starts Sat. 8-12-23, 2pm EST, ‘Ancient Kemet (Egypt), The Moors & The Maafa: Understanding The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. REGISTER NOW & WATCH!!! (LIVE 12 Week Online Course) with Michael Imhotep host of The African History Network Show. Discounted Registration $80; ALL LIVE SESSIONS WILL BE RECORDED SO YOU CAN WATCH AT ANY TIME! WATCH CONTENT ON DEMAND! REGISTER for Full Course HERE $80: https://theahn.learnworlds.com/course/ancient-kemet-moors-maafa-transatlantic-slave-trade-summer-2023 orhttps://theafricanhistorynetwork.com/

1 note

·

View note