#keyword: tanner

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

I saw your rat it’s in the possession of the girl from district 7, I advise the use of lethal force.

Tanner from District 10

Oh, Pup Harrington's former tribute? I wonder how Max got from the District 4 boy to her?

Anyway, thanks for the information. Expect a wiring of funds soon!

#internal communications:#f: you got that right abyssalis?#a: yeah. tanner. d10. i'll send over the funds shortly#a: also don't you think that information's a bit too... forceful? couldn't the source be biased?#f: well it's the only lead we've got! so be sure to see if you can track the D7 girl#a: we've got? wait.. this is not what i signed up for#inspected: approved#in foro#interrogatis#anonymous#keyword: tanner#keyword: max ratvinstill

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Project Sekai Idol AU

Now that our first set of MVs has been released, I think it's time we truly begin to dive into this AU :D

Their order of appearance (as in debut) is: YUME YUME JUMP!, Sunny☆Wonders, Wisteria, Fantasy Dreamers, and PASSION♡proJECT.

YUME YUME JUMP! was originally the most popular of the idol groups when it was just the first three. While each had a popular idol in them, Shizuku was ultimately the most popular and thus more people became fans of YYJ.

That being said, YUME YUME JUMP! would quickly fall in popularity when a new, all male, idol group debuted. This new all male idol group was Fantasy Dreamers.

Toya was originally set to be Fantasy Dreamers Prince Charming. However, his quieter nature made him more suited for a mysterious figure, so the Prince Charming persona ultimately fell onto Tsukasa.

The only person in PASSION♡proJECT who was excited for the opportunity to be an idol was Minori. The other three weren't all that for it, but went along just for her.

Each group has a center, someone who's almost always at the front. Those people are: An, Haruka, Airi, Tsukasa and Nene.

YYJ's management wanted Shizuku as their center. However, Shizuku pushed for An to be their center since she stood out the most between the four of them. With her darker hair and tanner skin, management eventually agreed that An did stand out the most, making her the one who'd be perfect as YYJ's front and center. And it worked. Putting An as the front person skyrocketed her popularity more and YYJ will sometimes really be pushed into that contrast look with An dressed in darker colors while everyone else wears lighter ones.

Both Sunny☆Wonders's and Wisteria's managements decided upon having the popular idol be their respective groups centers. While Mafuyu and Ena were both considered, they decided having someone already popular would boost the groups overall popularity. It worked, but not enough to be more popular than YYJ and less so when Fantasy Dreamers shot up to being the most popular group.

One of the biggest differences between Fantasy Dreamers and all the other idol groups is that they do somewhat have more of a say in what happens. Somewhat is your keyword. When it came to choosing someone who'd be at the front, it was easy for them all to choose Tsukasa. However, on the off chance someone else had to, they all agreed that Toya would be that person. Of course Tsukasa was the one chosen in the end.

When PASSION♡proJECT's management said they were making Nene their center, it wasn't done because they thought she was the best suited for it. It was solely because of her stage fright. Their idea was for their center to be someone who overcame her fears and was able to finally stand in the spotlight. Thus, being PASSION♡proJECT's center is actually very stressful for Nene because she is constantly being forced to be right in front of the group. She's the one who has to do more training so she can be their center, no matter how much the other three say they wouldn't mind being their groups center if it meant relieving Nene of that stress. But the decision was made and that's that.

#project sekai#project sekai colorful stage#hatsune miku colorful stage#proseka#prosekai#colorful stage#project sekai idol au#project sekai au#prsk idol au#prsk au#yume yume jump#fantasy dreamers#sunny☆wonders#wisteria#PASSION♡proJECT

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Résumé Is dying, And Artificial Intelligence (AI) Is Holding The Smoking Gun

As Thousands of Applications Flood Job Posts, 'Hiring Slop' Is Kicking Off An AI Arms Race.

— Benj Edwards | June 24, 2025

Credit: Sturti Via Getty Images

Employers are drowning in AI-generated job applications, with LinkedIn now processing 11,000 submissions per minute—a 45 percent surge from last year, according to new data reported by The New York Times.

Due to AI, the traditional hiring process has become overwhelmed with automated noise. It's the résumé equivalent of AI slop—call it "hiring slop," perhaps—that currently haunts social media and the web with sensational pictures and misleading information. The flood of ChatGPT-crafted résumés and bot-submitted applications has created an arms race between job seekers and employers, with both sides deploying increasingly sophisticated AI tools in a bot-versus-bot standoff that is quickly spiraling out of control.

The Times illustrates the scale of the problem with the story of an HR consultant named Katie Tanner, who was so inundated with over 1,200 applications for a single remote role that she had to remove the post entirely and was still sorting through the applications three months later.

In an age where ChatGPT can insert every keyword from a job description into a résumé with a simple prompt, her story is not unique. The problem began shortly after the emergence of mainstream generative AI bots in 2022, when some companies applied the technology to job applications to help overwhelmed job seekers. Now, several years later, the technology has evolved from a convenience tool to a systemic disruption of the hiring process.

Credit: Getty Images

Some candidates are now taking automation even further, paying for AI agents that autonomously find jobs and submit applications on their behalf. Recruiters report that many of the résumés look suspiciously similar, making it more difficult to identify genuinely qualified or interested candidates.

Computer tools have been assisting with creating résumés for decades, and everything from the typewriter to word processors to spellcheck and résumé templates have increased the ease of making a competent résumé. But AI has pushed the trend into overdrive. The potential to create endless output makes AI fundamentally different from its predecessors. Whereas earlier technologies helped people craft one good résumé more efficiently, AI enables candidates to generate hundreds of customized applications with minimal effort—turning what was once a time-intensive process of demonstrating interest into a numbers game that overwhelms businesses trying to find genuinely qualified applicants.

The frustration has reached a point where AI companies themselves are backing away from their own technology during the hiring process. Anthropic recently advised job seekers not to use LLMs on their applications—a striking admission from a company whose business model depends on people using AI for everything else.

The Slow, Painful Death of The Résumé

In response to the deluge, companies now deploy their own AI defenses. Chipotle's AI chatbot screening tool, nicknamed Ava Cado, has reportedly reduced hiring time by 75 percent. However, this trend from businesses has led to an arms race of escalating automation, with candidates using AI to generate interview answers while companies deploy AI to detect them—creating what amounts to machines talking to machines while humans get lost in the shuffle.

Ironically, LinkedIn has stepped into the middle of the crisis by providing even more AI, with new tools that aim to help both candidates and recruiters narrow their focus. For example, an AI agent launched late last year can write follow-up messages, conduct screening chats, suggest top applicants, and search for potential hires using natural language on the platform.

Beyond volume, fraud poses an increasing threat. In January, the Justice Department announced indictments in a scheme to place North Korean nationals in remote IT roles at US companies. Research firm Gartner says that fake identity cases are growing rapidly, with the company estimating that by 2028, about 1 in 4 job applicants could be fraudulent. And as we have previously reported, security researchers have also discovered that AI systems can hide invisible text in applications, potentially allowing candidates to game screening systems using prompt injections in ways human reviewers can't detect.

Credit: Moor Studio Via Getty Images

And that's not all. Even when AI screening tools work as intended, they exhibit similar biases to human recruiters, preferring white male names on résumés—raising legal concerns about discrimination. The European Union's AI Act already classifies hiring under its high-risk category with stringent restrictions. Although no US federal law specifically addresses AI use in hiring, general anti-discrimination laws still apply.

So perhaps résumés as a meaningful signal of candidate interest and qualification are becoming obsolete. And maybe that's OK. When anyone can generate hundreds of tailored applications with a few prompts, the document that once demonstrated effort and genuine interest in a position has devolved into noise.

Instead, the future of hiring may require abandoning the résumé altogether in favor of methods that AI can't easily replicate—live problem-solving sessions, portfolio reviews, or trial work periods, just to name a few ideas people sometimes consider (whether they are good ideas or not is beyond the scope of this piece). For now, employers and job seekers remain locked in an escalating technological arms race where machines screen the output of other machines, while the humans they're meant to serve struggle to make authentic connections in an increasingly inauthentic world.

Perhaps the endgame is robots interviewing other robots for jobs performed by robots, while humans sit on the beach drinking daiquiris and playing vintage video games. Well, one can dream.

— Benj Edwards is Ars Technica's Senior AI Reporter and Founder of the Site's Dedicated AI Beat in 2022. He's also a tech historian with almost two decades of experience. In his free time, he writes and records music, collects vintage computers, and enjoys nature. He lives in Raleigh, NC.

#Ars Technica#ArsTechnica.Com#Résumé#Artificial intelligence (AI)#Smoking Gun#'Hiring Slop'#An AI Arms Race#Benj Edwards#The Slow Painful Death of The Résumé

0 notes

Text

Tanner Mark Men's Genuine Caiman Belly Square Toe Boots Black TM208040

Premium Tanner Mark Men's Genuine Caiman Belly Square Toe Boots in Black - Ideal Botas Vaqueras para Hombre and Botas Vaqueras para Mujer - Elevate Your Western Style Today! Introducing Tanner Mark Men's Genuine Caiman Belly Square Toe Boots in Sleek Black - Model TM208040 Searching for the perfect blend of style, durability, and craftsmanship in cowboy boots? Look no further! Our Tanner Mark Men's Genuine Caiman Belly Square Toe Boots are the ultimate choice for anyone seeking high-quality Western footwear. Key Features: 🌟 Exquisite Caiman Belly Leather: Crafted with genuine Caiman belly leather, these boots exude luxury and sophistication. The distinctive texture of Caiman leather sets you apart from the crowd. 🌟 Square Toe Design: Designed for both style and comfort, our square toe boots provide ample room for your toes, ensuring a relaxed fit for long hours of wear. 🌟 Versatile Black Finish: These boots are perfect for various occasions. Whether you're hitting the ranch, going out for a night on the town, or just need a rugged pair of boots for everyday wear, the black finish complements any outfit. 🌟 Quality Craftsmanship: Tanner Mark is known for its commitment to quality. These boots are handcrafted with precision and attention to detail to ensure they meet the highest standards. Additional Keywords: 👢 Botas Vaqueras Ariat para Hombre: If you're in search of top-notch cowboy boots, Tanner Mark delivers on both style and quality. 👢 Cowboy Work Boots Near Me: Our boots are not just stylish; they're built tough for your demanding workdays. 👢 Women's Cowboy Boots Clearance Amazon: Although designed for men, these boots can be a perfect gift for the Western-loving women in your life. 👢 Carolina Cowboy Boots: Tanner Mark stands alongside renowned brands like Carolina in providing top-notch Western footwear. 👢 Black Sparkly Cowboy Boots: While our boots are not sparkly, their black finish and unique Caiman leather texture make them sparkle in their own way. 👢 Botas Vaqueras para Mujer: Women who appreciate quality and style can also consider these boots for a chic Western look. 👢 Botas Vaqueras para Hombre: Designed with men in mind, our boots combine style and functionality for the modern cowboy. Elevate your Western wardrobe with Tanner Mark Men's Genuine Caiman Belly Square Toe Boots in Black. Order yours today and experience the best in Western footwear! FAQs - Are square toe boots more comfortable than traditional pointed ones, especially when it comes to belly square toe boots? Square toe boots, such as botas vaqueras ariat para hombre, are designed with comfort in mind. They offer more room for your toes and the ball of your foot compared to traditional pointed boots. When it comes to belly square toe boots, the combination of comfort and the unique texture of Caiman leather makes them a stylish and comfortable choice for any cowboy boot enthusiast. - What are the key styling tips for wearing belly square toe boots with different outfits, from casual to formal? Caiman belly square toe boots, like the Tanner Mark Men's Genuine Caiman Belly Square Toe Boots, are incredibly versatile. You can pair them with casual jeans or dress them up with a suit. Their distinct texture adds a touch of sophistication to any outfit. Whether you're going for a rugged cowboy look or a refined Western appearance, these boots fit the bill. - Can you share your experience with Tanner Mark Men's Genuine Caiman Belly Square Toe Boots and how they compare to other Western boot options? Tanner Mark's Caiman belly square toe boots offer a unique blend of style and quality. When compared to other Western boot options like carolina cowboy boots or cowboy work boots near me, these boots stand out due to their exotic texture and comfortable square toe design. Many customers have praised their craftsmanship and durability, making them a worthwhile investment. - Are there any specific care and maintenance recommendations for preserving the distinctive texture of Caiman belly leather on square toe boots? To maintain the striking texture of Caiman belly square toe boots, follow some simple care tips. Use a specialized leather conditioner to keep the leather supple and moisturized. Regularly clean off dirt and dust with a soft brush. Avoid exposing them to extreme conditions, and store them in a cool, dry place when not in use. These care practices will help your boots, such as black sparkly cowboy boots or women's cowboy boots clearance amazon finds, retain their unique appearance for years to come. By following these suggestions, you can make the most of your stylish Caiman belly square toe boots while keeping them in excellent condition. Read the full article

#BellySquareToeBoots#blacksparklycowboyboots#botasvaquerasariatparahombre#botasvaquerasparahombre#botasvaquerasparamujer#carolinacowboyboots#cowboyworkbootsnearme#women'scowboybootsclearanceamazon

0 notes

Note

Where can I find info on princess nokia blackfishing? I thought she was Afro latina, im not saying she isn't blackfishing I just want to find more info on it

I have no idea how long ago you sent this but:

Literally if you just look at images of her you can physically see her morphing herself over the years into looking Black.

I had to research/come to the conclusions and look for this all myself. Some keywords that might help is that she used to go by themermaidgirl and wavyspice with the word tumblr on google (those were the names she went by before she switched to princess nokia.)

On her Blackfishing:

I basically found out through google after seeing what she looked like in her infamous “so juicy so fertile” Vogue video that she Blackfishes because I noticed she obviously uses tanner (Face lighter than body with different tones). I started googling her old pictures and social media names and...yeah here we are.

She deadass darkens her skin artificially, wears fake Afro wigs, and gets lip injections to make herself look Black, and is lying about being AfroPuerto Rican, she’s been lying about being Indigenous as well.

How you go from this:

To this:

Her own ex-friends have said she’s not Black and called her out for it. Actual Taino Indigenous people have repeatedly called her out for lying about being Taino.

If you look at pictures shes posted of her family literally none of them are Black. They’re more than likely white or majority white/mestize. None of them in Puerto Rico would be considered Black. None of them. Like my mother’s family is literally all very much white Puertoricans who come from white European colonialists in PR, and that side of my family look JUST LIKE the people in these pictures. She’s not ambigious mixed Black, she’s straight up Blackfishing and pretending to be Black.

She is literally mestiza/white Latina cosplaying Afro-Indigenous Latinidad. Like straight up fucking cosplaying being mixed and cosplaying being spiritual/in Afroreligions.

Like who tf sits there for instagram smoking cigars with a golden headwrap showing the viewers a Yemaya oracle card like she’s really doing something except for people who are using ATRs and shit for social media clout liiikkeeee.......She can smoke all the cigars she wants, that’s not gonna make her AfroPuertorican or Afrotaino for shit. It’s fucking embarassing.

I swear the reason she’s always going on about being mixed Afro-Indigenous is because in Latino culture, including PR culture, there’s this incorrect idea that we’re all European/African/Indigenous, therefore any Latino can claim Afrolatinidad. Obviously that’s not true. But I’ve even heard this stupid shit in progressive/activist circles.

And with ATR/ADRs and Brujeria becoming more visible and popular in recent years, why wouldn’t she jump on it to capitalize off the craze, considering that’s what made her popular? So I deadass wouldn’t be surprised if this is why she tries saying she’s Black when clearly neither she nor either sides of her family are any sort of Black Puertorican. But she’s been called out for this shit so many times, nobody can say she’s just ignorant, at this point she’s been telling people straight up lies.

She wears Afro styled wigs and then lies about it being her real hair. And people have apparently called her out before but she was adamant that its her real hair. You can tell that its not her real hair, and that her actual texture is wavy, not curly.

Those are all wigs. All 3 of them in the images. You can literally tell they’re wigs. Esp in the middle/second pic, look at those roots. You can see the braids underneath and how the curls aren’t actually connecting to her scalp. Bc those are fucking wigs. Even in the bruja video, she was wearing a fucking wig.

Why do you think she goes from a light tan, to a much darker warm almost orange shade, to a neutral medium shade, back to a super dark but more olive/green toned shade? Because that’s not what her actual color is.

Have you noticed how in a lot of photos of her, her skin is sort of patchy with random spots, or her face is super pale without makeup compared to a much darker body, her body most times being a much darker color than her hands? Why sometimes her nails look dirty?

It’s literally because she uses artificial tanners/spray tan on her skin. She’s always a different shade because it goes between being fresh and faded or she switches up the brands/colors/products she’s using.

Like look at her fucking hand compared to her face (and check out the injections) like wow:

She gets mad fucking CCs of injections into her lips to make them look fuller than they actually are. And she’s been getting it done for ages. In recent moments she’s been doing.......alot.

She’s 100% A Blackfisher like it’s fucking crazy because I didnt know that wasnt what she naturally looked like. honest to god this had me so fucked up and I’m still so fucking mad over this. I had heard people repeatedly saying she wasn’t Black and figured it out through just searching up on google. She’s absolutely fucking wild for profitting off of the idea that she’s AfropuertoRican and acting like shes supposed to be some sort of representation for us when she’s been fucking lyinggggg. Faux-spiritual and faux-Black as fuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuucckkk and making money off of it.

I even saw that she apparently tried to argue with a visibly Black woman who was calling her out, that the Black woman’s skin looked fake and orange and was probably a tan on twitter. Like. GIRL GET AWAY FROM THE MIRROR BECAUSE....

She’s fucking WILD.

#i was sooooo mad/sad when i found out#and put two and two together#like deadass fuck her#wg.personal

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

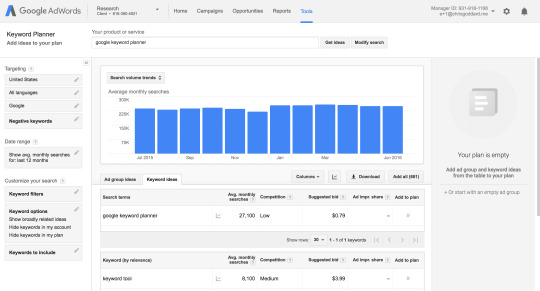

How to Find Long Tail Keywords on Google Adwords

How to Find Long Tail Keywords on Google Adwords

Is it actually tells you the projected monthly searches with no costs, so it just tells you if you’re free and you can just make a Google AdWords account with any gmail email. So you basically just go up here and you sign in make an account whatever you have to do, and you can go up to this tab up here and the tools and then you can click keyword, planner and I’ll. Bring you right here. So,…

View On WordPress

#affiliate marketing course#Affiliate marketing course review#affiliate marketing mastery#affiliate marketing mastery review#google adwords#keyword search volume#long tail keywords#long tail keywords adwords#ryan affiliate marketing course#tanner afilliate marketing course#tanner and ryan affiliate marketing course review#tanner j fox and ryan hildreth affiliate marketing mastery review

0 notes

Text

affiliate marketing programs

affiliate marketing meaning

affiliate marketing for beginners

affiliate marketing amazon

affiliate marketing jobs

affiliate marketing websites

affiliate marketing definition

affiliate marketing salary

affiliate marketing agency

affiliate marketing amazon sign up

affiliate marketing average income

affiliate marketing agreement

affiliate marketing apps

affiliate marketing and investor

affiliate marketing agreement template

affiliate marketing business

affiliate marketing books

affiliate marketing blog

affiliate marketing business model

affiliate marketing business plan

affiliate marketing beginners

affiliate marketing business names

affiliate marketing blueprint

plan b affiliate marketing

affiliate marketing companies

affiliate marketing course

affiliate marketing clickbank

affiliate marketing contract

affiliate marketing commission

affiliate marketing courses free

affiliate marketing commission rates

affiliate marketing contract template

c'est quoi affiliate marketing

affiliate marketing def

affiliate marketing disclaimer

affiliate marketing degree

affiliate marketing define

affiliate marketing description

affiliate marketing diagram

affiliate marketing dynamics

affiliate ad marketing

affiliate marketing examples

affiliate marketing explained

affiliate marketing email

affiliate marketing earnings

affiliate marketing ecommerce

affiliate marketing earn money

affiliate marketing email list

affiliate marketing etsy

affiliate e marketing

e commerce affiliate marketing

ebay affiliate marketing

e-commerce affiliate marketing business model

sto e affiliate marketing

e commerce vs affiliate marketing

affiliate marketing ebook

affiliate marketing e learning

affiliate marketing for dummies

affiliate marketing for beginners 2021

affiliate marketing for amazon

affiliate marketing free

affiliate marketing facebook

affiliate marketing funnel

affiliate marketing facebook ads

affiliate marketing google

affiliate marketing guide

affiliate marketing google ads

affiliate marketing getting started

affiliate marketing groups

affiliate marketing growth

affiliate marketing google course

affiliate marketing gaming

affiliate marketing how to start

affiliate marketing how does it work

affiliate marketing high ticket

affiliate marketing how much can you make

affiliate marketing how to make money

affiliate marketing hubspot

affiliate marketing high ticket items

affiliate marketing hacks

h&m affiliate marketing

h educate affiliate marketing

kya h affiliate marketing

does h&m have an affiliate program

affiliate marketing instagram

affiliate marketing income

affiliate marketing ideas

affiliate marketing is

affiliate marketing in spanish

affiliate marketing industry

affiliate marketing images

affiliate marketing influencers

i learn affiliate marketing

how do i affiliate marketing

how to learn affiliate marketing for beginners

how to learn affiliate marketing for free

how can i learn affiliate marketing for free

how do i become an affiliate marketer for beginners

affiliate marketing jobs online

affiliate marketing job description

affiliate marketing jobs from home

affiliate marketing jobs remote

affiliate marketing jobs no experience

affiliate marketing jobs near me

affiliate marketing jobs amazon

tanner j fox affiliate marketing

affiliate marketing keywords

affiliate marketing kpis

affiliate marketing kya hai

affiliate marketing keywords 2021

affiliate marketing kajabi

affiliate marketing kit

affiliate marketing keto

affiliate marketing keyword research

affiliate marketing links

affiliate marketing landing page

affiliate marketing legit

affiliate marketing logo

affiliate marketing link generator

affiliate marketing landing page examples

affiliate marketing llc

affiliate marketing leads

l'affiliate marketing manager

l'affiliate marketing manager stipendio

l'affiliate marketing

l'affiliate marketing manager cosa fa

l'affiliate marketing manager quanto guadagna

cos'è l'affiliate marketing

come funziona l'affiliate marketing

guadagnare con l'affiliate marketing

affiliate marketing manager

affiliate marketing manager salary

affiliate marketing make money

affiliate marketing monthly income

affiliate marketing mlm

affiliate marketing manager job description

affiliate marketing millionaire

affiliate marketing m&a

affiliate marketing niches

affiliate marketing networks

affiliate marketing niches 2021

affiliate marketing nike

affiliate marketing news

affiliate marketing name generator

affiliate marketing name ideas

affiliate marketing no website

affiliate marketing on pinterest

affiliate marketing on instagram

affiliate marketing opportunities

affiliate marketing on amazon

affiliate marketing on facebook

affiliate marketing on tiktok

affiliate marketing on youtube

affiliate marketing online

nate o'brien affiliate marketing

affiliate marketing today

dropshipping o affiliate marketing

o que é affiliate marketing

network marketing o affiliate marketing

affiliate marketing platforms

affiliate marketing programs for beginners

affiliate marketing passive income

affiliate marketing pinterest

affiliate marketing products

affiliate marketing pyramid scheme

affiliate marketing pay

y.i.e.p affiliate marketing

how to do affiliate marketing

affiliate marketing quotes

affiliate marketing questions

affiliate marketing quiz

affiliate marketing qualifications

affiliate marketing quizlet

affiliate marketing quora

affiliate marketing quotes 2021

affiliate marketing qatar

affiliate marketing q and a

q es affiliate marketing

affiliate marketing reviews

affiliate marketing real estate

affiliate marketing requirements

affiliate marketing rule

affiliate marketing resume

affiliate marketing revenue

affiliate marketing rakuten

affiliate marketing rates

r/affiliate marketing

affiliate marketing sites

affiliate marketing software

affiliate marketing scams

affiliate marketing side hustle

affiliate marketing shopify

affiliate marketing step by step

affiliate marketing strategies

is affiliate marketing legit

is affiliate marketing worth it

is affiliate marketing

is affiliate marketing a pyramid scheme

is affiliate marketing hard

is affiliate marketing profitable

is affiliate marketing worth it reddit

is affiliate marketing easy

affiliate marketing training

affiliate marketing tiktok

affiliate marketing tips

affiliate marketing target

affiliate marketing tools

affiliate marketing training courses

affiliate marketing taxes

affiliate marketing tutorial

t shirt affiliate marketing

affiliate marketing t mobile

affiliate marketing under 18

affiliate marketing using pinterest

affiliate marketing udemy

affiliate marketing ulta

affiliate marketing using facebook

affiliate marketing using instagram

affiliate marketing using google ads

affiliate marketing using tik tok

affiliate marketing u srbiji

affiliate marketing u bosni

affiliate marketing u hrvatskoj

affiliate marketing vs dropshipping

affiliate marketing vs mlm

affiliate marketing vs influencer marketing

affiliate marketing vs network marketing

affiliate marketing vs amazon fba

affiliate marketing vs digital marketing

affiliate marketing vs ecommerce

affiliate marketing videos

v commission affiliate marketing

gary v affiliate marketing

regulation v affiliate marketing

affiliate marketing vs network

affiliate marketing v česku

affiliate marketing v cesku

what is the average affiliate commission

affiliate marketing what is

affiliate marketing without a website

affiliate marketing website examples

affiliate marketing with amazon

affiliate marketing without a following

affiliate marketing with pinterest

affiliate marketing walmart

affiliate marketing w polsce

affiliate marketing ticaret

affiliate marketing xing

xiaomi affiliate marketing

#affiliate marketing#affiliateprogram#make money as an affiliate#affiliatemarketing#amazon affiliate#affiliate marketing salary#affiliate marketing for beginners#affiliate marketing companies#affiliate marketing websites#twitch affiliate#affiliate promotion#affiliate marketing meaning#affiliate money#make more money#how to make money online#make money online#make money from home#work at home#work from your phone#work from home#work from hotel#home business#money business#easy money

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

Parent au:

King meets Roman and Remus for the first time.

fyi first I use Elijah as King’s name. Anyways—

————

Patton surely meant well inviting Remus over to his place for a little dinner get together and introducing him to an old friend of his and Logan’s. He had kids Roman and Janus ages— a girl a few years older and a girl a few years younger— so he said to bring along his kid.

He doubts Patton knew what he was doing.

“Remus!”

Remus could only stare as his brother slapped him on his shoulder and brought him into a rough hug. Just as fast as it happened he pulled back and grabbed Remus by the nape of his neck with both hands.

“I should’ve known it was you Patty was talking about! Taking in a wayward lost teen! Of course!”

“Elijah,” Remus breathed out. He glances over at his 12 year old son, Roman watching in surprise. “Eli, you’re in town? With Eliza and—“

“Lily yeah!” Eli grinned. Stupid fucking grin. “Joanna is at Pa and Mari’s place.” His eyes finally caught onto Roman. “And this is…?”

“Oh! Fuck, right,” Remus slaps Eli’s hands off him and turns to Roman. He tries smiling at him, but he’s pretty sure it’s a little too shaky. He gestured widely towards him. “This is my son, Roman. Roman, this is… my older brother Elijah.”

“You said you killed your brother in the womb.” Roman said, narrowing his eyes at him.

“That was Roman, Roman,” Eli chuckles. “And he didn’t kill him in the womb, he died a few hours afterwards. Guess he named you after him, that’s sweet.”

“Eli’s my half-brother. 13 year difference.” Maybe they should just turn back around and leave. Remus and Roman see enough of their friends anyways, what’s one less night. Roman doesn’t need to know his uncle or his cousins or his aunt, he especially doesn’t need to know any stories about his grandparents or when Remus was a kid.

“You did mention having a brother when we were younger,” Oh, thank God. Patton saved him for the millionth time in their short friendship. Eli steps away from the door to let Patton come into view. He smiles at Remus and Roman, oblivious to the tension. “I thought you two looked familiar!”

“Blame that on our Papa,” Eli tuts. He claps Roman on his shoulder and pulls him into the house. Remus had to actively stop himself from pulling him back by clenching his fist, letting out a small whine. “He’s got strong genetics. Roman is almost the spitting image of him! If it wasn’t for his tanner skin, I would’ve thought I was looking at him in one of our photo albums.”

“Really?” Roman followed his uncle further into the house, Remus straggling after them, nervous to stray too far off. “Do you have any of those albums with you? Dad told me my grandparents were dead.”

“Dead? They aren’t dead?”

“I said they were dead to me. Keywords there are to and me.”

Eli leaned close to Roman’s ear. Remus tenses. “Your dad never liked our parents. He was always a bit of a problem child.”

“They kicked me out of the house?!” Eli started at Remus’ shout. All of them jumped at that. Remus pursed his lips. Eli laughed, depleting the tension in the room.

“Oh, you ran away as soon as you heard the news about Audri!” Leaning over Roman again. “That’s what our parents told me the Christmas that year. Said he ran away to be her and then she dumped him and left you with him. Lovely gal otherwise.”

"That’s a total lie,” Remus laughed. He was fighting the urge to start yelling. “Can’t believe they would lie about this shit.”

“You always accused them of lying.”

Motherfucker.

“Alright, Romy, that’s enough fun with uncle Eli,” Remus grabs his son's arm, ignoring his complaints to stay, and dragging him back to the door. “Dinner was nice, Pat, but look at the time. Roman probably has some homework and I’m thinking of getting up early tomorrow and open the shop up—“

“But— but you guys just got here?! You haven’t even talked to Logan or—”

“I talked to him two days ago, he can hold up until then.”

“But I want to talk to Uncle Eli!”

“No, no more talking with Uncle Eli,” Remus opens the door and throws a quick wave over his shoulder at everyone. “Bye bye, now!”

Remus shuts the door behind him and Roman tears himself from his grip. He turns back around and sees him fuming.

Great, now Roman has more shit to fuel his growing hatred for him. This is why he didn’t say anything about Eli. He knew this shit was going to happen. He just knew.

“Why didn’t you tell me about him? Why did you lie to me about your family?” He shouted.

Remus passed a hand over his face. “I didn’t lie technically. My twin did die and you misunderstood me when I told you about grandpa and grandma—”

“So why didn’t you mention having an older brother? And that he’s friends with Patton and Logan?”

“That I didn’t know about—“

“Why don’t you want me to have a relationship with him?!”

“Romy, I’m not talking about this right here, right now,” Remus presses the heel of his hand against his head as he hisses through his teeth, squeezing his eyes shut. “We still haven’t had any dinner; why don’t we go out to like, Wendy’s or something? You like Wendy’s.”

Roman grits his teeth and his eyes narrowed into slits. After a few moments of tense silence, he stomps his foot and lets out a frustrated shout. He storms past his dad and towards the car, slamming the passenger side door closed behind him and pouting in his seat. Remus sighed.

This was going to be a fucking terrible drive to Wendy’s.

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m on my room but I’ll have a slow day. Percy, Peyton, Derek, Phelan, Phoenix (Calvin by extension), Derrick, Teddy (young mostly, but adult if I can open Max resources’ too) will be my priority of the day.I.e. my Phoebe related muses frmo Charmed and Derrick. I am also willing to write my doctor, my River etcetc. And might make a Jonny Noble character using Freddie Thorp because having changed Theo is not enough. Might, though. Might. Keyword. Because I may also add something else instead. Hit me up if you want to write. Also, Stephen is forever on the table. And so is Tanner and Henry. And possibly Eric, but surely Bellamy? (lol i feel too many muses to say slow day oh well but it’ll be slow because ih ave a week to do ARR and get the car before that >.<)

1 note

·

View note

Text