#kenji misumi

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart in the Land of Demons (1973) Kenji Misumi

431 notes

·

View notes

Text

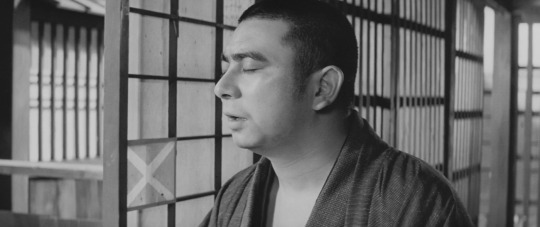

Kenji Misumi - Destiny's Son (1962)

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lone Wolf and Cub: Sword of Vengeance (1972) Art by Tony Stella

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ken (1964)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lone Wolf and Cub: Sword of Vengeance, Kenji Misumi, 1972.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Now watching:

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

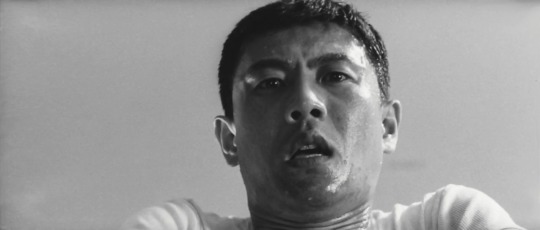

Recently Viewed: Ken (The Sword)

[The following review contains MAJOR SPOILERS; YOU HAVE BEEN WARNED!]

Kenji Misumi’s Ken (or The Sword, if you prefer translated titles) opens with an exquisitely crafted montage depicting excruciating physical exertion. The sun blazes blindingly overhead, shining more brilliantly than it did in Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon. Cold, steely eyes narrow with unwavering resolve. Beads of sweat glisten on the subject’s forehead, soaking the furrowed brow. Muscles tense with effort, so firm and taut that they threaten to tear the skin. And through it all, a bamboo sword slices the air, as rhythmic and relentless as the labored beating of a heart.

Such imagery recurs throughout the film. A later training sequence, for example, frequently cuts to disorienting POV shots as the characters do dozens, then scores, then hundreds of push-ups; the ground repeatedly rushes up to meet the camera, grit and pebbles blurring in and out of focus as perspiration drip-drip-drips onto the soil. Between sets, the exhausted athletes collapse, panting and thoroughly drenched; when they reluctantly rise to resume their monotonous, Sisyphean task, damp silhouettes of their bodies remain imprinted on the wooden planks of the dojo’s floor.

While they appear straightforward self-explanatory on the surface, these scenes are pregnant with deeper significance, elegantly conveying pretty much every one of writer Yukio Mishima’s thematic preoccupations via movement and action alone: his admiration of the human (masculine) physique, especially when it’s meticulously sculpted and/or strained to the absolute limits of fitness; his reverence for such “traditional Japanese values” as discipline, honor, and loyalty; his glorification of what I’ll charitably refer to as “youthful simple-mindedness” (a topic that he discusses in almost uncomfortably candid detail in Confessions of a Mask); and his obsession with the perverse, paradoxical overlap between violence and sex. Indeed, Misumi even addresses the subtextual—and sometimes blatantly, brazenly textual—homoeroticism that permeates the author’s work, staging an audacious bathhouse brawl that anticipates David Cronenberg’s Eastern Promises (albeit sans the graphic full-frontal nudity).

Of course, considering this is Mishima that we’re talking about—for further context, see Paul Schrader’s Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, a sublime biopic that revolves around the controversial novelist’s very public seppuku—it’s hardly a spoiler to reveal that the movie also (somewhat regrettably) unapologetically romanticizes suicide. After the protagonist (played by Raizo Ichikawa, who personifies Mishima’s core philosophy with a cool, aloof, enigmatic stoicism) is duped into believing that he’s utterly failed in his duties as captain of his university’s kendo club, he chooses to end his life on his own terms, preserving his “purity” and “dignity” by leaving behind a corpse so angelic and radiantly beautiful that it causes spurned lovers, stern mentors, bitter rivals, and envious subordinates alike to weep tears of remorse.

Misumi’s visual style perfectly complements the melodramatic narrative. The stark black-and-white cinematography, with its deep, moody shadows, mirrors our hero’s rigid, inflexible worldview. The compositions are equally evocative: the cramped, claustrophobic framing and oppressively symmetrical blocking (which mimic the surrounding architecture) trap the characters both figuratively and literally, lending the tragic conflict a palpable atmosphere of inevitability. This bleak, somber tone distinguishes Ken as a major departure from the director’s usual fare—particularly his numerous contributions to the chanbara genre, including most of the Lone Wolf and Cub series and some of the best installments in the Zatoichi franchise—and it’s more compelling for it. Misumi was, after all, a lifelong workhorse for Daiei (alongside such esteemed contemporaries as Kazuo Mori and Kazuo Ikehiro); how delightful, then, to learn that he occasionally helmed the studio’s “prestige” projects in addition to churning out countless B-pictures.

I first discovered the existence of Ken over a decade ago, when I encountered a brief summary of its plot in the pages of critic Patrick Galloway’s essential Warring Clans, Flashing Blades, and I’ve been desperately searching for a (legal) copy ever since. I’m glad that I was able to finally experience it on the big screen—in borderline pristine 4K to boot, thanks to Janus Films’ gorgeous restoration—courtesy of MoMA. Hopefully, a home video release will follow in the near future; despite its obvious flaws, it is a story that demands multiple viewings and reevaluations.

#Ken#The Sword#Ken (The Sword)#Kenji Misumi#Daiei#Raizo Ichikawa#MoMa#Museum of Modern Art#Janus Films#Japanese cinema#Japanese film#film#writing#movie review

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zatoichi Challenged [座頭市血煙り街道] (1967) Kenji Misumi

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kenji Misumi - Destiny's Son (1962)

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

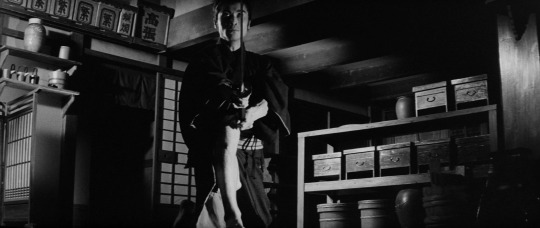

Sword Devil, Kenji Misumi

#sword devil#kenji misumi#1965#60s#1960s#samurai#japan#japanese#film#cinema#cinematography#screencaps#stills

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

O Conto de Zatoichi (1962), dir. Kenji Misumi.

Review originalmente postada: 09/Fev/2023 no Letterboxd.

Devo confessar que fui pego de surpresa, tinha um pré-conceito sobre a franquia do Zatoichi, pelo simples fato de ter tantos filmes, achava que era só filmes baratos de samurai para ganhar dinheiro fácil. Felizmente dei uma chance, percebi que é muito mais do que isso. O filme tem uma ótima fotografia, com enquadramentos que exploram a cegueira do Zatoichi de maneira muito criativa. E não tem essa de filme barato, a produção foi autêntica em recriar um Japão do período Edo. Um dos elementos mais fortes do filme é a atuação do Shintaro Katsu, que tem uma presença que faz jus em encarnar um personagem em tantos filmes.

Outra parte que gostei, é sempre legal de ver como a Yakuza era no Período Edo, era um temor e respeito por samurais, mesmo que samurais estivessem em decadência nesse período. Um exemplo é mesmo um chefe Yakuza com 60 yakuzas do seu lado, temia lutar contra apenas 1 samurai.

#Zatoichi Monogatori#The Tale of Zatoichi#Zatoichi#O-Tane#Miki Hirate#Shintaro Katsu#Masayo Banri#Shigeru Amachi#chambara#jidaigeki#samurai#ronin#yakuza#cinema#movie#japan movies#movies#japan cinema#japanese cinema#kenji misumi#love and tragedy

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart to Hades, Kenji Misumi, 1972.

3 notes

·

View notes