#kanbun

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Excerpt from the Lotus Sutra, chapter 16, in Kanbun Kundoku, a kind of creole language, a mixture of Classical Chinese and Classical Japanese into one language.

#lotus sutra#buddhist#buddhism#japan#japanese#classical japanese#classical chinese#chinese#kanji#kanbun#kanbun kundoku#creole#artificial language#linguistics#constructed language

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beauty of the Kanbun Era, Japan, ca. 1660–1680, Edo period

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Talking about books, not me online window shopping books again, someone stop me

#I went the kanji pipeline again and considering buying a kojiseigo dictionary#and the kojiki#and a textbook about kanbun#I really need to be stopped

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sangaku or san gaku (Japanese: 算額, lit. 'calculation tablet') are Japanese geometrical problems or theorems on wooden tablets which were placed as offerings at Shinto shrines or Buddhist temples during the Edo period by members of all social classes.

The sangaku were painted in color on wooden tablets (ema) and hung in the precincts of Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines as offerings to the kami and buddhas, as challenges to the congregants, or as displays of the solutions to questions. Many of these tablets were lost during the period of modernization that followed the Edo period, but around nine hundred are known to remain.

Fujita Kagen (1765–1821), a Japanese mathematician of prominence, published the first collection of sangaku problems, his Shimpeki Sampo (Mathematical problems Suspended from the Temple) in 1790, and in 1806 a sequel, the Zoku Shimpeki Sampo.

Further historical discussion

Sangaku are inscribed in a language called Kanbun, which used Chinese characters and essentially Chinese grammar, but included diacritical marks to indicate Japanese meaning. Kanbun played a role similar to Latin in the West and its use on sangaku would indicate that whoever set down the problems was highly educated. The majority of the presenters, in fact, seem to have been members of the samurai class.

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

DO IT IN YOUR STYLE – défi graphique, créé par @rollinginthedeep-swan (merci pour le tag, c'était si fun à faire ! ♡)

ci-contre : l'ukiyo-e (estampes de la période Edo) + Yuka Mannami (œuvres utilisées sous le cut parce que Tumblr a décidé de casser les liens 🤡 )

BUT DU DÉFI : un style artistique + un FC + votre style. je tag des gens que j'aime bien pour relever le défi, c'est évidemment facultatif 👀 @timuschaos @soletear @gorgonsplayground @monoclegraphic

#trop cool comme idée de tag game !#tag games#yuka mannami#yuka mannami avatars#avatars#avatars rpg#400x640

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daisho attributed to Shitahara Hiroshige/Takada Munekage Hello, world! Thank you for checking our daily post. Today, we are excited to show you another newly acquired antique Daisho. This Katana blade is attributed to Shitahara Hiroshige (下原広重) during the Kanbun era (1661-1673: early Edo period). Shitahara is the name of the area in Hachioji city in Tokyo area today where he created blades. According to NTHK that authenticated this blade, it was forged approximately in the early Edo period (Early-Mid 17th century). Hiroshige belonged to the Bushu Shitahara school, located in today’s Tokyo (Hachioji city). It is said that Yamamoto Norishige founded the school, and it thrived from the end of the Muromachi period to the late Edo period (Late 16th century to Late 19th century). This Wakizashi blade is attributed to Bungo Takada Munekage (豊後高田統景), who belonged to a prestigious school named Takada (高田). He was active during the Tensho era (1573-1592: late Muromachi period). Takada school was founded by Takada Tomoyuki in Takada village, Bungo domain (today’s Oita prefecture), during the Nanbokucho period (1334-1338 A.D). Takada Tomoyuki went to Bizen province (today’s Okayama prefecture) to master the sword-forging techniques of BIZEN and returned to the village and trained his apprentices. That is how Takada school started.

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

蘿藦[Gagaimo] Metaplexis japonica

It is a perennial creeping plant and grows in sunny areas. The flowers are often purplish in color. In autumn, it produces spindle-shaped fruits about ten centimeters long, and comate seeds emerge from inside the fruit shell, which splits longitudinally.

This name is an ateji, or a Chinese name with a Japanese reading applied to it. In the past, 蘿藦 was written as 羅摩, and these were read as kagami, which is also an ateji. The usual reading for both is rama.

故大國主神。出雲之御大之御前に坐す時に。波の穗自り。天之羅摩船に乘り而。鵝(蛾?)の皮を内剝に剝ぎて。衣服に爲て。歸り來る神有り。爾其の名を問はすれ雖も不答。且所󠄁從の諸神に問はすれ雖も。皆知らずと白しき。

[Kare ookuninushi-no kami, izumo no miho no misaki ni masu toki ni, nami no ho yori, ame no kagami no fune ni norite, himushi no kawa wo utsuhagi ni hagite, kimono ni shite yori kuru kami ari. Kare sono na wo towasuredomo kotaezu. Mata mitomo no kami tachi ni towasuredomo, mina shirazu to mōshiki.]

Now, when (a deity) Ookuninushi-no kami was at Mihonosaki in Izumo(Shimane Prefecture, today), there is a (very small) deity approaching from the white waves on a heavenly boat made of (the fruit shell of) Kagami and wearing clothing made from the stripped skin of a moth. So Ookuninushi asked him his name, but did not respond. And now Ookuninushi asked his attendant deities, but they all said, "I do not know". From Kojiki (The above quotations have been converted to sentences in the way of explanation reading) Source: https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/914528/1/35 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kojiki https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kanbun

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beauty of the Kanbun Era, Japan, ca. 1660–1680, Edo period

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

" Jujutsu in the Kaisen " - What that world means and who are they for real?

This topic has intrigued me for quite some time. During my university years—which are still ongoing—one of our Japanese text-reading classes featured a passage about the Jōmon period. The text mentioned jujutsu and the jujutsushi (shamans). Of course, I was already reading the manga by then, and it was around the time the second season came out, so I actively started researching. Below is what I found.

Let’s begin with a brief kanji overview: 呪術 (Jujutsu)

呪 – SPELL

Reading: Ju

Its core meanings include “spell,” “curse,” “charm,” or “prayer,” often used in connection with malevolent or supernatural things. It belongs to the kango family (meaning it came from China), which is used for traditional terms. Fun fact: During the Heian period, Chinese influence was huge, and this was when most Chinese kanji flowed into Japan, giving us yet another hidden Heian reference from the mangaka. This is also a compound kanji, meaning it was created by combining two smaller kanji in ancient China—the kanji for “mouth” and “brother,” which forms yet another wordplay. The “brother” (which could refer to a monk or shaman) casts a spell or curse through his mouth. One long-standing issue with shounen anime is that characters always have to say their attack names, which can seem cheesy, but not in Jujutsu Kaisen. Gege solves this by introducing the legend of shamans, who could only cast spells through their spoken words, thus creating a logical basis for why attack names must be spoken aloud.

術 – TECHNIQUE

Reading: Jutsu

It is most commonly used to mean “art,” “technique,” “method,” or “skill,” especially in contexts requiring some level of expertise or technical knowledge. It’s also a kanbun word and another compound kanji, though in a slightly different way than the previous one—this might deserve a separate article. It’s used frequently, not just in the word jujutsu (which refers to the technique of magic), but also appears in Naruto, where the same kanji forms part of ninjutsu. You’ll also find it in more sophisticated words like bijutsu, which refers to the fine arts. But enough linguistics—let’s move on to who the jujutsushi were.

JUJUTSUSHI:

The jujutsushi of the Jōmon period (ca. 14,000 BCE – 300 BCE) were not specific historical figures, but rather a term referring to the practitioners of jujutsu. However, jujutsu here should not be understood as a modern martial art, but in its original meaning, referring to the art of curses or magic.

The jujutsushi (呪術師) were individuals who practiced magic, rituals, curses, and spiritual activities. In the Jōmon period, these people were likely spiritual leaders, shamans, or healers who maintained a connection with the natural and spiritual worlds. During this era, people believed only in nature and the things around them, and these shamans were responsible for ensuring the mental well-being of the tribes. They were thought to possess the ability to foresee the future, return from the dead, and influence the weather. In other words, they were considered omnipotent. This is especially interesting because we’re dealing with a time far before the Heian period—the Jōmon can be considered Japan's prehistoric age. Isn’t it fascinating that Heian-era Sukuna could only be defeated by magic much older than his own? In my humble opinion, this is a brilliant idea.

When discussing the Heian period, even 20 volumes would not suffice to fully explore the various magics and shamanism, but since we’re focusing on Jujutsu Kaisen, I’ll highlight two key spiritual traditions:

The first is incredibly interesting in its own right, as it not only inspired JJK but also countless other anime, manga, and games. It’s none other than Onmyōdō and the Onmyōji. One of the most significant spiritual traditions of the Heian period, Onmyōdō (陰陽道), developed from Chinese yin-yang philosophy and astrology. The onmyōji (陰陽師) were sorcerers or spiritual advisors who served the aristocracy and the imperial court. Their duties included exorcising evil spirits, performing rituals to bring good fortune, observing celestial movements, and conducting curse-breaking ceremonies. The onmyōji can be seen as the jujutsushi of the Heian period, as they too dealt with spiritual defense and magical techniques. Some of you may know that the Heian period was named after the capital city of the time, Heian (modern-day Kyoto), so it’s not far-fetched to assume that both spiritual traditions originated from there. And speaking of jujutsu techniques from the Tokyo school, those are more rooted in Buddhist foundations. Megumi’s shikigami also come to mind, which are not particularly Buddhist, but then I remembered that he comes from the Zenin clan, which is based in Kyoto—so we’re still on track.

The second tradition was more Buddhist and spiritual during the Heian period, known as Esoteric Buddhism (Mikkyō). Another major spiritual and magical system in the Heian period was esoteric Buddhism, associated with the Shingon and Tendai Buddhist schools. Priests performed intricate rituals and magic aimed at relieving human suffering and banishing evil spirits. The ceremonies often involved reciting mantras, using mudras (hand gestures), and employing mandalas. This tradition utilized mudras, which can be understood as hand gestures. Many characters in the series use this symbolic system. I wonder if you’ve noticed the sequence of mudras shown one after another in the second opening of the second season?

One last FanFact and that's it for today:

In Esoteric Buddhism, protective deities like Fudō Myōō (Acala) are common. These deities are strong, warrior-like protectors who can be invoked through rituals for protection. Similar defensive techniques also appear in Jujutsu Kaisen, such as the Domain Expansion (領域展開, Ryōiki Tenkai) techniques, which create a user-controlled territory. These resemble the ritualistic circles and protective symbols used in Esoteric Buddhist practices. In Jujutsu Kaisen, these techniques often involve spiritual or magical power to defeat opponents within the controlled area.

That's it for today! This topic might be worth a second part in the future, but we'll see. Do you have any questions? If there's any topic about Jujutsu Kaisen you're curious about, feel free to reach out to me!

Yo,

Getami 2024.09.29

#jjk#jujutsu#kaisen#jujutsu kaisen#gege akutami#kaisend#phonology#research#anime#manga#heian#kanji#megumi#joumon#history#kyoto#buddhism#mikkyo#shounen

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

A long time coming. So where do I begin?

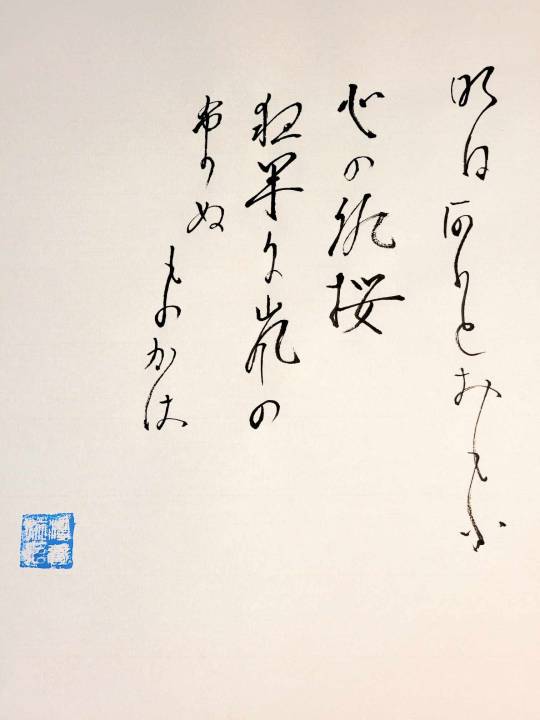

"A heart that thinks 'there is always tomorrow,' is like a fleeting sakura blossom. Perhaps it may blow away, Within a midnight storm."

-The monk, Shinran (親鸞) upon becoming a monk.

Hello everyone. It has been a long time. I was the semi-amateur historian formerly known as Aggrobot. I don't know what I am now.

I apologize for the long absence. I have neglected you all somewhat, but life caught up with me. After university I became a working person (社畜) and my love for history got away from me somewhat.

I felt inspired to return for a variety of reasons, chief among them re-reading some of @the-archlich and @arosthorn's old posts. Recalling the good times I had in this little community made me happy. So the calligraphy above is dedicated to you, my old history community.

This is not to say that I completely dropped my history studies. I now have a pretty strong understanding of both the Genpei period and the Nanbokucho period of Japanese History and my ability to read Classical Chinese poetry in kanbun kundoku has gotten better. But as of late, I have been itching to return to China, the land of my ancestors, the Land of Mountains and Rivers.

Perhaps there is one thing that should be updated on: I have become a published poet, although admittedly not in my native tongue. I have published a handful of Japanese poems in the local tanka magazine of a city I briefly lived in. In light of this endeavor, I took a poetic sobriquet: The Traveller of an Overflowing Dream (濫夢旅人). The sobriquet was inspired by the Xunzi (荀子) by the author of the same name, as well as the Chinese poet Li Bai (李白) and Japanese poet/author Natsume Soseki (夏目漱石). Perhaps I may share some of my poetry with you in the future. Perhaps I may even commit it to brush. Time will tell.

While I would like to return to studying Chinese history problem is, I don't know where to start anymore. While I still have some of my de Crespigny readings and a complete collection of Cao Pi's known poetry, in addition to some of my Republican era readings from my thesis. But alas, this is incomplete and not nearly up to standard. Moreover, I suspect that great research has been done since then that I am not aware. The world does not stop simply because I get bored haha.

Below I have compiled a list of topics I am interested in returning to study. If any of you have good resources for them, it would be most welcome.

The Three Kingdoms Period (220-279) a. The Gaoping Incident b. The Three Rebellions of Shouchun c. Conquest of Wu by Jin

The War of the Eight Princes

The Yongjia Disaster and the Foundation of Eastern Jin

The Murong clan and the various states of Yan

Republican/Warlord Period (1911-1937) a. Federalism in the Republican/Warlord Period b. Wu Peifu c. Yan Xishan

If you have read this far, I thank you heartfelt. I look forward to reconnecting with some of my old friends.

Honestly, I do not know which ones are still around and which ones have moved on. Regardless, I hope we can speak again.

「海上生明月、 天涯共此時」 -張九齢

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

To me Classical Chinese always felt futuristic, a language of an advanced space-faring civilization, rather than something from ancient and medieval China.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

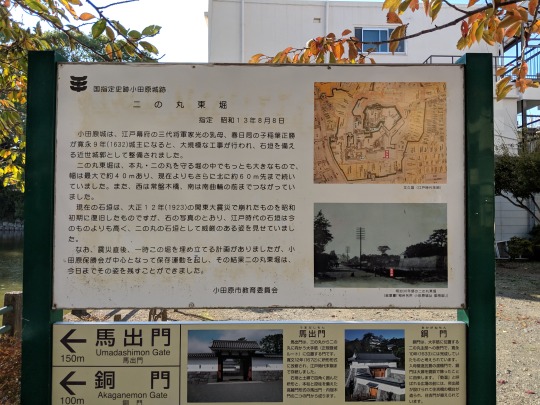

国指定史跡小田原城跡 二の丸東堀 指定 昭和13年8月8日 小田原城は、江戸幕府の三代将軍家光の乳母、春日局の子稲葉正勝が寛永9年(1632)城主になると、大規模な工事が行われ、石垣を備える近世城郭として整備されました。 二の丸東堀は、本丸・二の丸を守る堀の中でもっとも大きなもので、幅は最大で約40mあり、現在よりもさらに北に約60m先まで続いてしました。また、西は常磐木橋、南は南曲輪の前までつながっていました。 現在の石垣は、大正12年(1923)の関東大震災で崩れたものを昭和初期に復旧したものですが、石の写真のとおり、江戸時代の石垣は今のものよりも高く、二の丸の石垣として威厳のある姿を見せていました。 なお、震災直後、一時この堀を埋め立てる計画がありましたが、小田原保勝会が中心となって保存運動を起こし、その結果二の丸東堀は、今日までその姿を残すことができました。 小田原市教育委員会

文久図 (江戸時代末期) 現在地 明治36年頃の二の丸東堀 (絵葉書[相州名所 小田原城址 御用邸])

馬出門 Umadashimon Gate 銅門 Akaganemon Gate

馬出門 馬出門は、三の丸から二の丸に向かう大手筋(正規登城ルート)に位置する門です。寛文12年(1672)に枡形形式に改修され、江戸時代末期まで存続しました。 石垣と土塀で四角く囲んだ枡形と、本柱と控柱を備えた高麗門形式の馬出門・内冠木門の二つの門から成ります。

銅門 銅門は、大手筋に位置する二の丸主部への表門で、寛永10年(1633)には完成していたものと考えられています。 入母屋造瓦葺の渡櫓門で、銅門は大扉を銅鋲で飾ったことに由来します。[勢溜]と呼ばれる広場の前には、突出部が設けられて住吉橋の橋会が造られ、住吉門が据えられています。

Vocab 史跡 (しせき)historic landmark 小田原 (おだわら)Odawara 城跡 (しろあと)castle site 二の丸(にのまる)outer citadel 堀 (ほり)moat 将軍 (しょうぐん)shogun 家光 (いえみつ)(Tokugawa) Iemitsu 乳母 (うぼ)wet nurse 春日局 (かすがのつぼね)Lady Kasuga 稲葉正勝 (いなば・まさかつ)Inaba Masakatsu 寛永 (かんえい)Kan’ei era 城主 (じょうしゅ)lord of a castle 大規模 (だいきぼ)large scale 工事 (こうじ)construction work 石垣 (いしがき)stone wall 備える (そなえる) to prepare for 近世 (きんせい)early modern period(from the end of Azuchi-Momoyama period to the end of the Edo period) 城郭 (じょうかく)castle, citadel, fortress 整備 (せいび)maintenance 本丸 (ほんまる)inner citadel 幅 (はば)width, breadth 常磐 (ときわ)Tokiwa 木橋 (もっきょう)wooden bridge 曲輪 (くるわ)(refers to things both inside and outside of the castle grounds (incl. the walls, moat, (etc.) 関東大震災 (かんとうだいしんさい)Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 復旧 (ふっきゅう)restoration なお furthermore 埋め立てる (うめたてる)to fill up, reclaim 保勝 (ほしょう)preservation of a place of scenic beauty 残す (のこす)to leave undone, not finish 文久 (ぶんきゅう)Bunkyu era (2.19.1861-2.20.1864) 絵葉書 (えはがき)picture postcard 御用邸 (ごようてい)imperial villa 三の丸 (さんまる)outermost region of the castle 大手筋 (おおですじ)large-scale operators 正規 (せいき)regular, normal 登城 (とじょう)attendance at a castle 寛文 (かんぶん)Kanbun era (4.25.1661-9/21/1673) 枡形 (ますがた)rectangular space between the inner and outer gates of a castle (where troops can gather) 改修 (かいしゅう)repair, improvement 存続 (そんぞく)continuance 土塀 (とべい)earthen wall 控柱 (ひかえばしら)secondary pillars 備える (そなえる)to furnish/equip with, install 高麗門 (こうらいもん)Koraimon, a style of gate architecture that consists of a tiled gabled roof with two pillars and two smaller roofs over the 控柱 冠木門 (かぶきもん)Kabukimon, a gate in a wall formed by two square posts and a horizontal beam から成る (からなる)to consist of, be composed of 主部 (しゅぶ)main/principal part 表門 (おもてもん)front gate 入母屋造 (いりもやづくり)Irimoya, a building with a hipped, gabled roof 瓦葺 (かわらぶき)tile roofing 櫓門 (やぐらもん)Yaguramon, a gate with a tower/turret on top 渡櫓 (わたるやぐら)a turret built on top of a stone wall 銅 (どう)copper 鋲 (びょう)rivet 勢溜 (せいがまり)a place where troops can gather and prepare 突出部 (とっしゅつぶ)extrusion, overhang 設ける (もうける)to prepare, provide 住吉橋 (すみよしばし)Sumiyoshi Bridge 据える (すえる)to place (in position), to lay (foundation)

https://tetsugakunomichi.jp/about.html (defines 保勝 as 景勝地の保全)

#日本語#Japanese langage#Japanese vocabulary#Japanese langblr#日本#Japan#小田原市#Odawara#小田原城#Odawara Castle#Japanese history#日本歴史#tumblr has made it significantly harder to apply my color coding but gdi I'm going to finish this project

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kjøkken/Stue-omvisning; finner du tv?

Lørdagskole! Kanbun/gammel-japansk timen var artig da, fordi han éne sier så mye rart. Spesielt når han prøver å snakke engelsk, får latterkramper hver gang.

Vet at jeg bare har vært her i sånn 1 og en halv måned, men det føles ut som at jeg har vært borte ifra Norge i evigheter. Beklager om det kommer skrivefeil i innleggene mine fremover- begynner å glemme norsk. 😂

I morgen har jeg planer om å dra til selveste cosplay-strøket Harajuku med Mirano!

心何も言いたくない。

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

actually going from wasei-kango to wasei-eigo and from kanbun to colloquial japanese in writing makes me feel unwelcome as someone who knows some chinese but no japanese. RETVRN

Incredible recent British unionist bit:

“Scots language is xenophobic and is specifically spoken to make foreigners feel unwelcome when visiting Scotland.”

Imagine visiting Japan and going “Too much Japanese language here, clearly this is a hate crime.”

34K notes

·

View notes

Text

Where do they keep all the kunten materials. Why isn't there a database. I'm looking up kanbun materials hoping to open up the document scans and find them crawling with little diacritics just to find regular ass chinese

0 notes

Text

Summer Schools: The Ca’ Foscari - Princeton Summer School in Classical Chinese and Classical Japanese / Italy

Programme directors: Professors Tiziana Lippiello (Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, Italy) and Martin Kern (Princeton University, USA) Course Instructors: Prof. Attilio Andreini Prof. Keiko Ono Study options Track A – Classical Chinese The course provides the fundamentals of classical Chinese grammar through the reading and analysis of passages of pre- modern Chinese historical and literary texts. Prerequisites: one year of modern Chinese language. Track B - Classical Japanese/Kanbun The cou http://dlvr.it/T3FWdL

0 notes