#kanamori wallpaper

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#eizouken#keep your hands off eizouken#eizouken icons#eizouken matching icons#eizouken wallpaper#anime matching icons#asakusa icons#kanamori icons#midori asakusa icons#keep your hands off eizouken icons#keep your hands off eizouken wallpaper#anime#anime icons#eizouken sketches#anime lq icons#anime matchup#kanamori edits#kanamori wallpaper#kanamori

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

some wallpapers i made from the extra pages

#kny#kimetsu no yaiba#demon slayer#kny wallpaper#aesthetic wallpaper#wallpaper#shinobu kochō#inosuke hashibira#kanao tsuyuri#nezuko kamado#tanjirou kamado#sumi nakahara#kiyo terauchi#naho takada#kotetsu#kanamori kozo#hotaru haganezuka

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Lockscreen Eizouken

Follow @powedits on twitter

#with psd#psd#anime#anime icons#icons anime#wallpaper#aesthetic#lockscreens#vintage#gothic#kanamori eizouken#keep your hands off eizouken!#wallpapers anime

65 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I am in love with Kanamori so I made myself a phone wallpaper hehe instagram // twitter

#keep your hands off eizouken!#eizouken#kanamori#sayaka kanamori#kanamori sayaka#fanart#anime#digital art#2020

1 note

·

View note

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 3 (1): the Origin of the 4.5-mat Room¹.

1) With respect to the 4.5-mat sitting room², it was created³ by Shukō. Because this was the shin-no-zashiki [眞座敷]⁴, tori-no-ko paper⁵ was pasted [onto the walls] to lighten [the interior of the room], and cryptomeria boards without frames⁶ were used for the ceiling. Small wooden shingles were used to cover the gablet-roof, and it had a one-ken [一間]⁷ toko. His treasured bokuseki by Engo [圜悟]⁸ was hung up, and he honored [his guests] by using the daisu [when he served them tea]⁹. Sometime later, [Shukō] cut a ro [in the floor], and the kyū-dai [弓臺] was arranged together with it.

In general, though objects of the sort that were [customarily] arranged in the shoin were [also] placed out [in this setting], their total number was reduced: [for example,] in the toko, a pair of pictorial scrolls¹¹ were hung -- or, naturally, just a single painted scroll could also be hung up. In front of this a small table [was set up], on which was an incense burner and a [pair of] hanaire¹². Or possibly a small flower-vase in which one variety of flower has been stood¹⁴. Or else writing paper and an ink stone, or a tanzaku-bako [短冊箱]¹⁵, or a [small] reading desk¹⁶. Or perhaps a bon-san [盆山]¹⁷, a ha-cha-tsubo [葉茶壺]¹⁸, or other things like that. Only things of this sort were displayed [in Shukō's room].

With the advent of Jōō, the yojō-han was modified here and there by removing the [wallpaper] to reveal the mud-plaster of the walls, while he also replaced the wooden pillars [that support the walls] with bamboo. He removed the koshi-ita [腰板]¹⁹ from the shōji, and replaced the black-lacquered sill at the bottom of the toko with one painted either with thin-lacquer, or he left [the sill] unpainted²⁰. This is said to be the sō-no-zashiki [草の座敷]²¹.

[Jō]ō²²did not display the daisu in that kind of room. When he felt like displaying the kyū-dai [弓臺], then the kakemono and the objects displayed [in the room] were similar to the things that Shukō had used. [But] when he [used] the fukuro-dana, [he displayed] a bokuseki in the toko; and except for the hanaire, nothing else was placed there.

Later [still], Sōeki²³ began to use a ko-yashiki that had a thatched roof²⁴ on every occasion²⁵. This was a manifestation of his practice of wabi²⁶.

Jōō's [yojō-han] zashiki, as a result [of this development], was [thenceforth] considered to exist somewhere between the shoin and the ko-zashiki. For this reason, when using the fukuro-dana, a certain flexibility is permitted²⁷.

In the above enumeration of the various objects displayed by Shukō, with respect to the piece of furniture [referred to as a] joku [卓], if something like a small flower-vase with a flower standing in it is excluded, any number of other things might be placed [on it]²⁸.

_________________________

¹This section, which is clearly spurious, does little more than reiterate details taken from Kanamori Sōwa's largely fictitious “history” of chanoyu*. The language of the entry is typical of the Edo period.

It is not really clear (from the surviving documents of his period) what Jōō and the chajin of his generation actually believed -- though the cha-kai [茶會], as it existed then (and now†), was a creation of Jōō (albeit based on the format of the Shino family's incense gatherings, which they referred to as kō-kai [香會]); and the intimate knowledge of this fact would surely have colored their perception of chanoyu’s earlier history.

The details of the 4.5-mat room, as described in this entry, had already been fixed much earlier than Shukō's period, since a room of this size had been considered appropriate for a man's personal living space according to the tenets of buke-zukuri [武家造]‡, the style of architecture favored by the military class, from which the shoin-zukuri [書院造] style (featuring shoin rooms with details such as are described here) had been evolving since the late Kamakura period**. __________ *Sōwa, a daimyō with a scholarly bent and an interest in chanoyu (he had studied tea with Sen no Dōan), was commissioned to write this history by the Tokugawa bakufu, with the express purpose being to Japanize chanoyu, in order to create the precedent necessary to facilitate the bakufu’s sale of Hideyoshi’s collection of meibutsu tea utensils (and thereby raise the cash necessary to pay off the Tokugawa family’s war-debts).

As long as chanoyu was generally perceived to be an imported foreign (Korean) taste, the market for tea utensils was distinctly limited to the (mostly ethnic Korean) curio collectors (whose ranks had been thinned considerably as a result of Hideyoshi’s decimation of Sakai and Hakata in 1595, as punishment for their opposition to his failed invasion of the continent).

†Today the equivalent of Jōō's cha-kai is known by the name of chaji [茶事]. The reader is cautioned to keep this fact in mind, and not confuse Jōō's and Rikyū's usage with the modern chakai [茶会].

‡According to the twelfth century Hōjō Ki [方丈記]. The so-called hōjō [方丈], which means a room one jō square (one jō is 10 shaku long: rooms of this dimension predated the time when the floor came to be completely covered with tatami mats), was approximately the same size as a 4.5-mat room.

**While the word shoin [書院] is usually translated as “study,” its function was much more encompassing: the nobleman used the shoin not only as his personal sitting room (making it rather like a den), but he also slept, ate, washed, and dressed there, as well as using the room for the reception of intimate guests. The tokonoma in this room functioned as a jō-dan [上段] (the built-in equivalent of the mi-chōdai [御帳臺], or nobleman's “seat of estate”) on occasions when this sort of formality was needed when receiving persons of differing rank (the toko-gamachi allowed reed or gauze curtains to be suspended from it, to obscure the nobleman’s countenance from those whose rank did not permitted them to look directly at him).

²Yojō-han zashiki ha [四疊半座敷ハ].

The word zashiki [座敷] means a “sitting room.”

³Sakuji [作事] means to build, construct. According to this entry, Shukō was the first to build such a room (though this is patently false -- since, even in the context of chanoyu, Yoshimasa used a room of this sort for serving tea before Shukō even arrived in Japan from Korea).

⁴Shin-no-zashiki [眞座敷]: perhaps the interpretation of this expression as meaning “most formal [style of] sitting room” is called for by the context.

⁵Tori-no-ko kami [鳥子紙] is a kind of paper with one side finished to a hard texture resembling the surface of a chicken egg.

⁶Fuchi-nashi tenjō [ふちなし天井]. In the earlier period, the ceiling was constructed in such a way that it appeared to consist of a series of small panels surrounded by frames (this is usually called a coffered ceiling in English, and a classical Japanese example with elaborate gilding and painting is shown below, on the left).

The term fuchi-nashi tenjō [縁無し天井] means that the frames were eliminated: the ceiling now consisted of a series of flat boards, laid side by side (this style of ceiling, sometimes called kagami-tenjō [鏡天井], is shown above, on the right).

In the early days, the uniform surface invited the painting of clouds and dragons and other heavenly figures, usually in black ink; but by the Momoyama period, colors and gilding were also added. The example shown above is found in the Sūtra Hall of the Kiyomizu temple in Kyōto.

⁷Ikken [一間] means six feet. This was a tokonoma with what was essentially a full-sized tatami mat covering the floor.

⁸Engo no bokuseki [圓悟の墨跡].

This refers to the bokuseki that is known as the Nagare Engo [流れ圜悟] today*. This scroll is said to have been the first bokuseki ever used for chanoyu.

The scroll was written by the Chinese Chán (Zen) monk Yuán-wù Kèqín [圜悟克勤; 1063 ~ 1135], the editor of the Bìyán Lù [碧 巖 錄] (Heki-gan Roku; the Blue-cliff Records).

As has been mentioned before in this blog, this document was not intended to be used as a scroll, but was actually part of Yuán-wù’s lecture notes (he traveled around China giving lectures on the cases in the Bìyán Lù, and this is a fragment of the text of one of his lectures, which one of the attendees probably kept as a souvenir of the occasion. __________ *This is the scroll that tradition holds was given to Shukō by Ikkyū Sōjun.

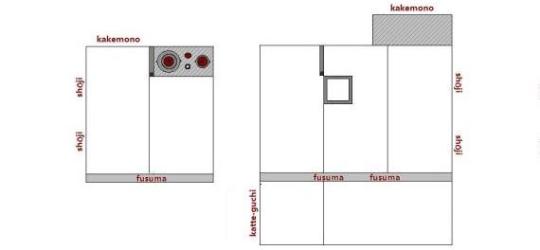

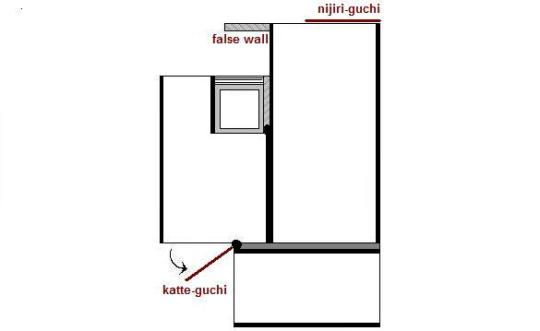

⁹In fact, Shukō appears to have used a sort of o-chanoyu-dana (perhaps missing a suspended upper shelf) to hold the utensils, rather than a daisu, as shown on the left in the sketch (below).

When his room, the Shukō-an [珠光庵] (in the Shōmyō-ji [稱名寺], in Nara), was reconstructed (the reconstruction is shown in the sketch on the right), this board-floored area was assumed to be the tokonoma (and so it was moved beyond the end of the guests’ mat, and enlarged to the size of the Sen families’ preferred toko for the small room, in keeping with the teaching of suki [数奇] -- which states that the guests must be provided with at least one full mat for their use), and an extra mat for making tea (featuring a daime-gamae situated at the end of an ordinary maru-jō, and so somewhat resembling the original version of the Tai-an) was added to what had originally been a two-mat residential cell. This board seems to have become (quite mistakenly) the precedent for the ita-doko [板床].

¹⁰Kyū-dai [弓臺]: this is an abbreviated reference to the kyū-dai daisu [及第臺子], shown below.

This tana, which was originaly made for use as a writing desk on the continent, has a ten-ita that is the same size as that of the large shin-daisu (measuring 1-shaku 4-sun by 2-shaku 9-sun 5-bu); however, because the ji-ita is smaller (in fact, it is the same size as the small shin-daisu, and measures 1-shaku 3-sun by 2-shaku 7-sun 5-bu), it could not be used with the furo (since the legs would prevent the host from raising or lowering the kan on the kimen-buro when necessary*).

Traditionally it is said that Jōō was the first person to use the ro, though the earliest documents seem to be rather confused on this point. It is possible that a hole was cut in a square board that replaced part of the floor, into which an iron ro-dan† was lowered to hold the fire, and this practice may have predated the appearance of Jōō by several decades. __________ *In the early period, chanoyu was generally performed to serve tea to a single guest (who was technically taking the place of the Buddha, so that the tea would not be wasted). When this person was a nobleman, the kan were raised (so they lean against the neck of the furo) when he was present in the room, but lowered (so that they depend below the kan-tsuki).

†Or, more likely, an old cooking pot with the sides above the flange broken off. This seems to have already been in use on the continent by the more wabi of tea men, so it is possible that the practice arrived in Japan during the second half of the fifteenth century.

If so, then it may be that Jōō, rather than introducing the use of a sunken fire, may have been the first to use a mud-plastered cooking hearth of the sort found in the farmhouse kitchen.

¹¹Ni-fuku-tsui [二幅對] refers to a pair of scrolls that were intended to be displayed together. Sometimes they represented a larger work that had been cut in half (since narrower scrolls were much easier to preserve than excessively large ones), and sometimes separate works (sometimes by different artists) that came to be used together in order to evoke a scene*. Scrolls intended for this purpose were prepared with identical mountings.

In addition to pairs of paintings, the number of scrolls in a set sometimes exceeded five, or even eight. It is in light of this that Shukō's restriction to a pair becomes important. __________ *Traditionally, one scroll should be a landscape, while the other should feature human subjects (generally representations of the Buddha, or esteemed monks) -- the idea being to figuratively locate the people in the landscape.

The scene was originally supposed to suggest a vision of the Buddha Amitābha's Western Paradise.

¹²Mae ni ha joku ni kōro, hanaire [前にハ卓に香爐、花入].

The incense burner was placed in the middle of the small table, with either a hanaire on each side, or (at night) a hanaire and a small candlestick. The idea was to reinforce the idea of a vision of the Western Paradise, where the air is said to be perfumed. The flower arrangements bring the scenery of the scroll paintings into the foreground.

¹³Arui ha ko-kabin ni isshoku-rikka [あるひハ小花瓶に一色立華].

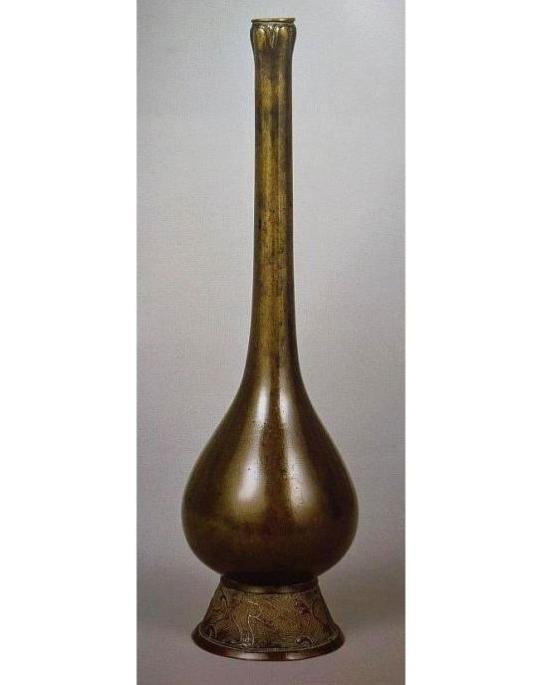

A ko-kabin [小花瓶] is the kind of flower container that Rikyū described (in his kaiki) as a hoso-guchi [細口].

Isshoku-rikka [一色立華] means a single type of flower is stood upright in the hanaire.

¹⁴Ko-kabin ni isshoku rikka [小花瓶に一色立華].

The meaning of this phrase, in this context, is unclear.

Ko-kabin [小花瓶] would seem to refer to a small bronze hanaire, one that is large enough to hold just a single flower. Rikyū's famous Tsuru-no-hito-koe [鶴ノ一聲] (shown below) is an example of the kind of vase referred to as a “ko-kabin” in classical works such as Nōami's Kun-dai Kan Sa-u Chō Ki [君臺観左右帳記].

The expression isshoku [一色], which literally means “one color,” was also used to mean one variety or type (out of two, or more, possibilities*).

However, while the name rikka [立華] usually refers to a highly stylized floral arrangement (intended to recreate a landscape in miniature), it would be physically impossible to arrange more than a single stem in a ko-kabin (at least if the word is being used in its classical sense); nor would it seem possible to create a rikka using only one variety of flower†.

While this is not the sort of mistake that Jōō (or Rikyū) would likely have made, it appears that whomever was responsible for adding this section to Jōō’s text was not so well informed. Thus, while I have interpreted the statement to mean that a single variety (isshoku [一色]) of flower (ka [華]) is stood (ritsu [立]) in the ko-kabin, this reading should be considered tentative. __________ *In Book One of the Nampō Roku, the expression is used, relative to flowers, to mean one of the two possibilities -- which were the flowers of herbaceous plants, and the flowers of woody plants. Precisely how it is being used here -- and whether the usage is the same as previously or not -- is debatable.

†These highly mannered arrangements generally use some sort of long-lasting woody plant material to define the basic structure of the arrangement, which is then “filled in” with various other flowers. In the shoin setting, where the arrangement was often kept in the tokonoma for a considerable period of time, the woody material remains, while the herbaceous flowers are changed when they begin to wilt.

¹⁵A tanzaku-bako [短冊箱] was a special lacquered box in which a collection of tanzaku [短冊] (elongated pieces of paper on which poems were written) was kept. Some of the tanzaku may have already been used, while others were unused.

The tanzaku featuring poems were generally selected because they were appropriate to the occasion, and intended to inspire the guests to use the unused tanzaku for their own compositions.

¹⁶A bundai [文臺] was a small table (about the height of ones lap when seated on the floor) on which a book (or open scroll) was rested while reading it. A bundai could also be used when writing (in a situation where there was not a built-in writing desk available for this purpose).

¹⁷A bon-san [盆山] is a small stone naturally shaped like a mountain, arranged in a tray of rather fine white gravel, with the gravel shaped to resemble a beach and sand-dunes in front of the stone, and the waves of the distant ocean behind (according to a poem by Ashikaga Yoshimasa that is preserved in several of Rikyū's densho).

The bon-san known as Zan-setsu [殘雪], which was one of Yoshimasa’s personal treasures. The stone is shown resting on a Korean sawari [四分一] tray. (Sawari is a variety of bronze containing a certain proportion of silver. The purpose of the silver was to keep the bronze from oxidizing, so it would remain a pale golden color.)

¹⁸Ha-cha-tsubo [葉茶壺]: a large jar in which the dried leaves that will (eventually) be ground into matcha are stored.

¹⁹Koshi-ita [腰板] refers to a wooden panel at the bottom of a shōji (anywhere between 6-sun and 1-shaku or more high), that prevents a person sitting beside it from accidentally damaging the paper with their feet. By removing the koshi-ita, Jōō let more light into the room at floor level.

²⁰Toko no nuri-buchi wo, usu-nuri, mata ha shira-ki ni shi [床のぬりぶちを、うすぬり、又ハ白木にし].

Originally the sill of the toko was lacquered with shin-nuri (since only the homes of important persons featured a tokonoma*). Jōō modified this by either painting the sill with thin lacquer (usu-nuri [薄塗り]†), or by leaving the sill unpainted (shira-ki [白木]‡). __________ *The original purpose of the tokonoma was to serve as a sort of jō-dan [上段], a place where the man of rank could sit when receiving people of a lower station than himself.

†There are two possible meanings for this:

- the black lacquer itself is thin, meaning that the variations in height of the grain can be perceived after the lacquer flattens (this is referred to as kaki-awase nuri [掻き合わせ塗り] today);

- or, the amount of iron powder (which colors the lacquer black) is limited or eliminated (resulting in something resembling tame-nuri [溜め塗り], which is technically a mixture of shin-nuri and Shunkei-nuri; or the honey-colored Shunkei-nuri [春慶塗り] by itself) -- here the lacquer itself is thinly colored, so the grain of the underlying wood-grain can be perceived through the lacquer (as if under glass).

In documents from the period, both the Hora-dana [洞棚] (on the left: it is painted with black kaki-awase-nuri) and the Jōō-dana [紹鷗棚] (on the right: this tana is painted with Shunkei-nuri) are described as being painted with usu-nuri.

‡Shira-ki specifically means wood with the bark removed. The word does not deal with whether the wood was squared, had the four faces shaved, or left in the round.

²¹Sō-no-zashiki [草の座敷]: in contrast to the shin-no-zashiki [眞座敷] (see footnote 4, above), the sō-no-zashiki would be an “informal” room.

²²Ō [鷗] is an abbreviation of Jōō's [紹鷗] name.

²³The name Sōeki [宗易], of course, refers to Rikyū. Sōeki was his Buddhist name; which, according to the custom of the day, he used as his professional name.

²⁴Kusabuki no ko-yashiki [草茨の小屋敷].

Kusabuki [草茨] seems to be cognate with the more commonly used (today) kusabuki [草葺], meaning a thatched roof.

A ko-yashiki [小屋敷] is a detached tearoom erected (usually on the far side of the garden) as a free-standing building.

²⁵Sen ni shi [專にし].

Sen ni shi [專にし] means exclusively, only. In other words, the author of this essay is arguing that, from a certain point in time*, Rikyū used only rooms of this sort.

The difficulty with this assertion is that Rikyū's surviving rooms -- and certainly the Jissō-an (which was Rikyū's “small room” for most of his life†) all appear to have been roofed with small wooden shingles (in the manner that this essay ascribes to Jōō) -- apparently to give the building a feeling of lightness and impermanence (such thin pieces of wood would begin to rot, and have to be replaced every few years).

Furuta Sōshitsu (Oribe) is the one who preferred his small rooms to have deeply thatched roofs (in the manner of the farmhouses in the snowy provinces), and a delight for this style of ko-yashiki spread from him to the machi-shū who gathered around Imai Sōkyū, and so to Sen no Sōtan (whose father Shōan was at least a nominal member of Sōkyū’s group).

Rikyū, meanwhile, appears to have considered this kind of roof to look oppressive and suffocating (according to his writings). __________ *Presumably when he embarked on his public life as a teacher of chanoyu. The oldest surviving (and apparently earliest) of his densho, the Nambō-ate no densho [南坊宛の傳書], suggests that this was around 1573.

†The two-mat rooms seem to have appeared around the time that Rikyū entered Hideyoshi's service -- perhaps because Hideyoshi objected to the daime rooms (the Jissō-an is a two-mat daime) because the sode-kabe (which was entire from floor to ceiling in Rikyū's room -- the fenestration at the bottom of the wall was introduced later, by Oribe) made it difficult for the guests to see clearly what the host was doing.

It certainly could never be argued that Rikyū’s chanoyu became more wabi after he entered Hideyoshi’s employ than before.

²⁶Wabi wo itasareshi yue [わびを致されし故].

Literally, “[because] he was doing wabi.”

²⁷Sukoshi-sukoshi yuru-shite [少〻ゆるして].

That is, on the one hand, the feeling can be rather formal; while on the other, a temae where the fukuro-dana is used can also seem quite wabi -- depending on the utensils used, and the way they are arranged.

It was for this reason that the fukuro-dana could be used in the 4.5-mat room (where its purpose was to display the utensils*), yet also tucked away into the kamae at the head of the daime in the small room† (where its purpose was to make things easier for the host‡). __________ *This is why, in the shoin, the guests are expected to open the ji-fukuro and also inspect whatever the host may have placed therein. It is thus the complete opposite of the dōko (even though its purpose is similar) -- which exists purely for the host's convenience (the dōko must never be opened by the guests so that they may peek inside).

†The original small rooms (Jōō’s Yamazato-no-iori [山里ノ庵], shown below and on the left, and Rikyū’s Jissō-an [實相庵], below, right) were both 2-mat daime structures.

These first two rooms were followed by the ichi-jō-han [一疊半] (where the ro was moved within the kamae, making the second of the “guests’ mats” no longer necessary: this room is shown below) -- a setting with which Rikyū very quickly became disenchanted (though it remained popular with certain of the machi-shū into the early Edo period).

This prompted him to remove the sode-kabe and restore the utensil mat to a maru-jō [丸疊] (a full-sized mat) -- resulting in the 2-mat room with mukō-ro that he used for the rest of his life.

All of the other variants of the small room appeared later.

‡In other words, so that he did not have to make several trips back and forth between the temae-za and the katte.

The original sode-kabe (the "sleeve-wall" that encloses the daime-gamae) was complete from floor to ceiling, thus anything within the kamae was, for all intents and purposes, invisible to the guests. The things within the kamae were placed there simply so that the host did not have to bring them out one by one after the guests had taken their seats.

The kamae was finally superseded by the dōko (in the case of Rikyū's small rooms, perhaps beginning during the second half of 1587).

²⁸It seems that the person responsible for inserting this entry into Jōō’s text (who does not seem to have been Tachibana Jitsuzan) neglected to copy it out in full, and came back later to add what had been missed.

That is why I decided to separate this statement from the rest of the text of this section.

0 notes

Link

anime wallpaper Kanamori Maria (Kiratto Pri☆Chan) #2994105 #anime #kanamori #kiratto #maria #prichan #wallpaper

0 notes