#just have a little ‘*translated from american sign language’ as an editor’s note & people will know what’s going on

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

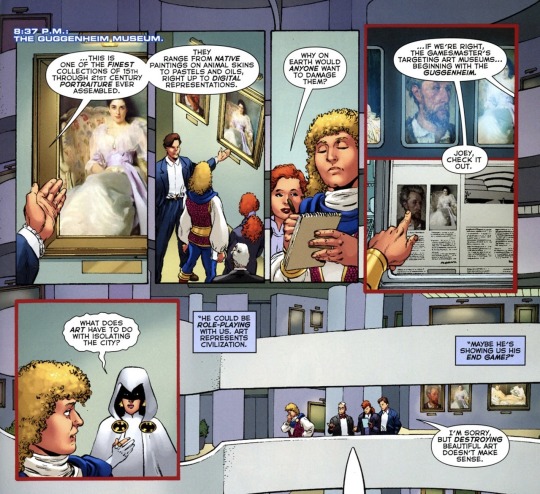

thinking about the time they actually gave joey dialogue in the new teen titans: games…

“He could be role-playing with us. Art represents civilization. Maybe he’s showing us his end game?”

this says sooo much about him: his deductive reasoning skills, his appreciation for art, his understanding of other people’s psychology. i need more stories where joey gets to play detective, especially in an art or music history context, and i NEED him to have proper dialogue

#imagining an art heist job with his mom in the searchers inc. comic that exists in my head#let him be thoughtful & have a personality beyond just the sweet helpful guy who’s a good listener#we see some of this skill as a tactician in ntt#(that issue where titans tower gets attacked by the hybrid comes to mind#plus the super inventive ways he uses his powers in general)#but there’s a level of characterization you get from dialogue that he’s almost never given in ntt#there are some narration boxes that kind of give insight into his thoughts#and then there’s that issue in late late ntt that has excerpts from a book he’s writing about the titans#but in general other characters vaguely paraphrase things he signs or we just see their response & what he even said is only implied#really it wouldn’t be hard to give him dialogue like at all they did it here with text boxes that have quotation marks#you could also use angle brackets like they do in american comics when a character’s speaking in a language other than english#just have a little ‘*translated from american sign language’ as an editor’s note & people will know what’s going on#joey wilson#the new teen titans: games#undescribed

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Podcast: Your Gut Instinct is Bad For Your Relationships

While caring for his wife as she struggled with a severe nervous breakdown, Dr. Gleb Tsipursky put the cognitive strategies he’d long been teaching others to work on his strained relationship. After seeing the incredible impact it had on his marriage as a whole, he decided to write a book to share these relationship-changing communication strategies.

Join us as Dr. Tsipursky explains why going with your “gut” can actually backfire and shares 12 practical mental habits you can begin using today for excellent communication.

We want to hear from you — Please fill out our listener survey by clicking the graphic above!

SUBSCRIBE & REVIEW

Guest information for ‘Gleb Tsipursky- Instinct Relationship’ Podcast Episode

Gleb Tsipursky, PhD, is a cognitive neuroscientist and behavioral economist on a mission to protect people from relationship disasters caused by the mental blind spots known as cognitive biases through the use of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)-informed strategies. His expertise comes from over fifteen years in academia researching cognitive neuroscience and behavioral economics, including seven as a professor at Ohio State University, where he published dozens of peer-reviewed articles in academic journals such as Behavior and Social Issues and Journal of Social and Political Psychology. It also stems from his background of over twenty years of consulting, coaching, speaking, and training on improving relationships in business settings as CEO of Disaster Avoidance Experts. A civic activist, Tsipursky leads Intentional Insights, a nonprofit organization popularizing the research on solving cognitive biases, and has extensive expertise on translating the research to a broad audience. His cutting-edge thought leadership was featured in over 400 articles and 350 interviews in Time, Scientific American, Psychology Today, Newsweek, The Conversation, CNBC, CBS News, NPR, and more. A best-selling author, he wrote Never Go With Your Gut, The Truth Seeker’s Handbook, and Pro Truth. He lives in Columbus, OH; and to avoid disaster in his personal life, makes sure to spend ample time with his wife.

About The Psych Central Podcast Host

Gabe Howard is an award-winning writer and speaker who lives with bipolar disorder. He is the author of the popular book, Mental Illness is an Asshole and other Observations, available from Amazon; signed copies are also available directly from the author. To learn more about Gabe, please visit his website, gabehoward.com.

Computer Generated Transcript for ‘Gleb Tsipursky- Instinct Relationship’ Episode

Editor’s Note: Please be mindful that this transcript has been computer generated and therefore may contain inaccuracies and grammar errors. Thank you.

Announcer: You’re listening to the Psych Central Podcast, where guest experts in the field of psychology and mental health share thought-provoking information using plain, everyday language. Here’s your host, Gabe Howard.

Gabe Howard: Hello, everyone, and welcome to this week’s episode of The Psych Central Podcast. Calling into the show today, we have Dr. Gleb Tsipursky. Dr. Tispursky is on a mission to protect leaders from dangerous judgment errors known as cognitive biases by developing the most effective decision-making strategies. He is the author of The Blindspots Between Us, and he’s a returning guest. Dr. Tsipursky, welcome to the show.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: Thanks so much for having me on again, Gabe. It’s a pleasure.

Gabe Howard: Well, I’m very excited to have you on, because today we’re going to be talking about how our mental blind spots can damage our relationships and how to defeat these blind spots to save our relationships. I think this is something a lot of people can really relate to because we all very much care about our relationships.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: We do, but we think too little about the kind of mental blind spots that devastate our relationships. I mean, there’s a reason about 40% of marriages in the US end in divorces. And there is a reason that so many friendships break apart due to misunderstandings and conflicts that don’t need to happen. And when I see people doing that, running into these sorts of problems, they are just suffering in needless, unnecessary way. And that really harms them, and that really kind of breaks my heart. So that’s why I wrote this book.

Gabe Howard: We think about the term cognitive bias and there’s just so many psychological terms that basically say the way that your body feels is lying to you. That just because something makes you feel good doesn’t make it good. And just because something feels bad doesn’t make it bad. And I know that you’ve done excellent work in helping business leaders understand that. And this book is sort of an extension of that work in helping people understand that just because your friend or lover or spouse makes you feel bad doesn’t make it bad. Is that what you’re trying to tie together here?

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: I am, and this work actually emerged from where my wife, about five years ago, had a nervous breakdown, major nervous breakdown, where she was in a pretty terrible spot. So like you said, I’ve been doing consulting, coaching, training for business leaders for over 20 years now. And I’m a Ph.D. in cognitive neuroscience, behavioral economics. I’ve taught at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and at Ohio State as a professor for fifteen years. Now, at that point when my wife had a nervous breakdown, that was pretty terrible. So she was just crying for no reason, anxious for no reason. No reason that she was aware of. And that was really bad. She couldn’t work, she couldn’t do anything. I had to become her caretaker. And that was a really big strain on a relationship. I knew about these strategies, which I was already teaching to business leaders, and I started applying them toward our relationship. And we started to work through some of these strains in our relationship using the strategies. And so seeing the kind of impact that they had on our marriage and where they pretty much saved our marriage, definitely would not have been able to cope without these strategies. I decided that it would be a good time to write a book for a broader audience about personal relationships, romantic life, friendship, community, civic engagement, all of those sorts of relationships that are really damaged by the blind spots we have between us as human beings that can really be saved if we just are more aware of these blind spots and know about the research based tactics to address these blind spots.

Gabe Howard: As I’m sitting here listening to you, I completely agree with you, I know your educational background. I know the research that you’ve put into it. I’ve read your books and I believe you, Dr. Tsipursky. But there’s this large part of me that’s like, wait a minute, we’re supposed to trust our heart and trust our gut, especially in romantic relationships, love at first sight. I mean, every romantic comedy is based on this butterflies in the stomach. So the logical part of me is like Dr. Tsipursky, spot on. But the I want to fall in love in this magical way part of me is like, don’t bring science into this. And I imagine you get this a lot, right, because love isn’t supposed to boil down to science. What do you say to that?

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: Well, I say it’s just like exactly the kind of love we feel for a box of dozen donuts. You know, when we see them, when we see that box of dozen donuts, we just have this desire in our heart and our gut. We feel it’s the right thing to do to just gorge on those donuts. They look delicious and it’s yummy. And wouldn’t it be lovely to eat all those donuts, right? Well, I mean, what would happen to you after that?

Gabe Howard: Right.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: That would not be a good consequence for you. You know that. You know that, you know, five minutes after you finished gorging yourself on those donuts or eating a whole tub of ice cream or whatever your poison is, that you would be regretting it. And that is the kind of experience that we have where our body, our heart, our mind, or our feelings, whatever it comes from, those sensations, they lie to us. They deceive us about what’s good for us. And that all comes from how our emotions are wired. They’re not actually wired for the modern environment. That’s the sucky thing. They’re wired for the savannah environment. When we lived in small tribes of hunter-gatherers, fifteen people to 150 people. So in that environment, when we came across a source of sugar, honey, apples, bananas, it was very important for us to eat as much of it as possible. And that’s what our emotions were for. We are the descendants of those who were successfully able to gorge themselves on all the sugar that they came across, all the honey. And therefore, they survived and those who didn’t, didn’t. That’s an inborn instinct in us. That’s a genetic instinct. Now, in the current modern environment, it leads us in very bad directions because we have way too much sugar in our environment for our own good.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: So if we eat too much of it, we get fat. That’s bad for us. There’s a reason there’s an obesity epidemic here in the US and actually around the world in countries that adopt the US diet. And so this is why you want to understand that your feelings are going to be lying to you around food, around what kind of food you want to eat. In the same way, your feelings, the current research is showing very clearly, that your feelings are going to be lying to you about other people because our feelings are adapted to the tribal environment, when we lived in those small tribes. They are a great fit if you happen to live in a small tribe in the African savannah. But for all of you who are not listening to this podcast in a small little cave in the African savannah, they’re going to be a terrible fit for you. It’s really going to cause you to make really wrong, terrible decisions for your long term good. Because these natural, primitive, savage feelings are not what you want to be using for modern, current environment.

Gabe Howard: There’s a phrase and you reference it as well. Marketers say you can’t go wrong telling people what they want to hear, and that’s a great marketing concept to sell, you know, cereal. But it’s not such a great concept if you’re trying to encourage people to fall in love, get married or make decisions. Because if you buy a cereal that you don’t like, eh, you’re out four bucks, right. You’re out, you know, five bucks, big deal. You never eat the cereal again. But if you wreck a relationship that is good or you enter into a relationship that’s bad, this has real long term consequences.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: Right now, in the current environment where we don’t realize that go with your heart and follow your gut on the romantic relationships is horrible advice that will devastate your relationships, no matter how uncomfortable you feel about me saying that. People like Tony Robbins, I mean, he says be primal, be savage. You know, follow your intuition. That’s an essential message for people like Tony Robbins or Dr. Oz or whatever. All those other people who are on those stages and who millions of people listen to. It’s very comfortable to hear that message because you want to follow your gut. You feel good about it. Just like it feels comfortable, it feels delightful to eat those dozen donuts. It feels delightful, feels comfortable to go with your gut and follow your intuitions in your relationships, because that is what feels good. It doesn’t feel comfortable at all, you really have to go outside of your comfort zone to do the difficult thing and step back from your intuitions and from your feelings and say, hey, I might be wrong about this. This might not be the right move. I might not want to enter into this relationship or I might want to stop this relationship. That’s actually not good for me. But people don’t want to hear that. These people who tell you this advice, they actually are leading you in very bad directions, very harmful, very dangerous directions. Research shows clearly that they’re wrong.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: And if you don’t want to screw up your relationships and you’re not going to be part of the 40% whose marriages end up in divorce and whose other sorts of relationships are devastated. So this is something that you need to realize that you are going to be really shooting yourself in the foot if you follow the advice of to be primal, to be savage. Even though it feels very uncomfortable to hear what I’m saying right now. Of course, it goes against your intuitions. It doesn’t feel comfortable and it will never feel comfortable. Just like there are lots of unscrupulous food companies that sell you a box of dozen donuts when they really should be selling you a box of two donuts. I mean, that’s the healthy thing in the modern environment. We know that. That’s what doctors advise us, but it’s very hard to stop it when we have a box of dozen donuts. Well, why then do companies sell us a box of dozen donuts? Because they make a lot more money doing this then when they sell you one donut or two donuts. So the relationship gurus, they make a whole lot more money than people who tell you to actually do the right but uncomfortable thing. The simple, counterintuitive, effective strategies that help you address your relationships by defeating these mental blind spots and helping you save your relationships.

Gabe Howard: We’ll be right back after these messages.

Sponsor Message: This episode is sponsored by BetterHelp.com. Secure, convenient, and affordable online counseling. Our counselors are licensed, accredited professionals. Anything you share is confidential. Schedule secure video or phone sessions, plus chat and text with your therapist whenever you feel it’s needed. A month of online therapy often costs less than a single traditional face to face session. Go to BetterHelp.com/PsychCentral and experience seven days of free therapy to see if online counseling is right for you. BetterHelp.com/PsychCentral.

Gabe Howard: And we’re back discussing how our mental blind spots can damage our relationships with Dr. Gleb Tsipursky. One of the things I like about your book is that you talk about the illusion of transparency and you have a story that sort of surrounds it to bring this to the forefront so that people can understand it. Can you talk about the illusion of transparency and can you share the story that’s in your book?

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: Happy to. So the story was of two casual acquaintances of mine. They went out on a date together. George and Mary, when they went on the date, George, he thought it was wonderful. Mary was so understanding, so interested, listened to him so well. And George told Mary all about himself. He felt that Mary really understood him, unlike so many of the women that he dated. So as they parted for the night, they agreed to schedule another date soon. Well, the next day, George texted Mary, but Mary didn’t text back. So, George waited for a day and sent Mary a Facebook message. But she didn’t respond to him. Even though George noticed that she saw the Facebook message. He sent her an e-mail then. But Mary maintained radio silence. Eventually, he gave up trying to contact her. He was really disappointed, and he thought that, just like all of these other women, how can he be so wrong about her? So why didn’t Mary write back or respond back? Well, she had a different experience than George on the date. Mary was polite and shy and she felt really overwhelmed from the start of a date with George being so extroverted and energetic, telling her all about himself, his parents, job, friends, not asking her anything about herself.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: And she thought, you know, why would I date someone who overwhelms me like that? Doesn’t really care about what I think? She politely listened to George, not wanting to hurt his feelings. And she told George, she would go out with him again, but she had absolutely no intention of doing so. I learned about this, the really different viewpoints of Mary and George, because I knew both of them as casual acquaintances. George, after the date, started complaining to people around him, including me, about Mary’s refusal to respond to the messages. That he thought at least went very well. And George felt that he was genuinely sharing and Mary did wonderful listing so he was confused and upset. I privately then went to Mary, asked Mary about, hey, what’s up? What happened? And she told me her side of the story. She told me that she sent a lot of nonverbal signals of her lack of interest in what he was saying to her. But George really failed to catch the signals. Mary perceived him as oversharing and herself as behaving very politely until she could leave. Now, that’s the story. That’s the nature of the story. You might feel that it’s problematic for Mary to avoid responding to George’s texts.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: But you have to realize that there are tons of Marys out there who behave this way due to a combination of shyness, politeness, and conflict avoidance. That’s the kind of people they are. They’re kind of anxious about conflict. But at the same time, there are so many Georges, they are very extroverted, they’re very energetic. And as a result, they don’t read nonverbal signals from others very well at all. In this case, both George and Mary fell into the illusion of transparency. This is one of the most common mental blind spots or cognitive biases. The illusion of transparency describes our tendency to greatly overestimate the extent to which others understand our mental patterns, what we feel and what we think. It’s one of the many biases that cause us to feel, think, and talk past each other. And so this is the big problem for us, the illusion of transparency, because if you feel that, like George felt, that Mary understands him and Mary feels like I’m sending these very clear signals, why does this guy keep being a jerk and not responding to them? That is something super dangerous for relationships, harms a great deal of relationships when we misunderstand the extent to which other people get us.

Gabe Howard: One of the things that I want to focus in on is that she said that she was sending non verbals. On one hand, I am guilty of missing the nonverbal. So I’m going to tend to take Georgia’s side in this, which is that she didn’t speak up. She didn’t say anything, and instead she hinted. And it sounds like what you’re saying is that she felt in her gut that her nonverbals, her hinting, were enough and that Georgia’s lack of responding made him rude.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: Mm-hmm.

Gabe Howard: But probably from George’s side, as you said, George’s like, she said nothing. I carried on. And now she’s blaming me. So now we’ve got both of those sides. Now, they’re not going to work out as a romantic couple.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: Clearly.

Gabe Howard: we get it. It’s a bummer. But let’s pretend for a moment that you are much more invested, Dr. Tsipursky, in George and Mary than you actually are. And you’re like, oh, my God, if they can just get over this one tiny little hump, they will just be a beautiful couple forever. And I know you’re not a therapist, but if you could sit George and Mary down and say, listen, you two are actually a perfect couple. But you’ve let this primitive nonsense get in the way. How would you help them get over this hump so they could see that, actually, they do have quite a bit in common?

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: Well, I would think that one of the things they need to work on is let’s say they have, share a lot of interests and they have very similar values. They have a lot of differences in their communication styles. That will be a big challenge. First of all, working on the illusion of transparency, they need to be much more humble about the idea that the other person understands them, about their ability to send signals correctly. The essence of the illusion of transparency is that when we think we’re sending a signal, a message to other people, we think the other person gets it 100%. That’s just how it feels because we feel OK, we’re sending this message. Therefore, the other people understand it because we are sending it.

Gabe Howard: Right.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: We are way too confident about our own ability to be good communicators. And that is the underlying essence of the illusion of transparency. Everyone, all of us, and especially George and Mary, need to develop a great deal more humility about their ability to send the signals, whether verbal or nonverbal and have those signals be received appropriately. So that’s kind of one thing to work on. The other things to work on would be the differences in communication styles where Mary is clearly shy., conflict-avoidant. So she’s very unlikely to speak up just because of that personality. It will take her a great deal of emotional labor to speak up in these areas. So perhaps that she can, instead of speaking up, because specifically verbalizing things is pretty difficult for many people. She can have a nonverbal signal that’s much more clear, you know, raising her hand in some way to indicate that, you know, hey, I’m getting overwhelmed. We need to pause or something like that. So some way that you can clearly indicate that she needs a break and that the conversation perhaps is not leading to where she wants it to lead and that George needs to stop talking. And George needs to, by contrast, to be much more aware and clearly reading Mary’s signals of interest and not interest. Because, you know, George is a raconteur. He likes telling stories. He likes sharing about himself. He likes sharing about everything. And he just kind of does overwhelm people. Knowing him as a casual acquaintance, he’s kind of the life of the party. But life is not always a party.

Gabe Howard: So, you know, like I can absolutely relate to George, you know, it’s not an accident that I’m a speaker, a podcaster, or a writer. All of these things involve being the center of attention and sharing and talking. So I really can relate to George. And that’s kind of why I brought it up, because I have a lot of Marys in my life.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: Mm-hmm.

Gabe Howard: And I was completely unaware that I was overwhelming people because I just assumed that people would tell me to stop or something. I just didn’t know. So when I became older and more understanding and more socially adept, I realized that, oh, wow, people think that I’m ignoring their wishes. And that’s kind of why I want to touch on it. And obviously, I can only speak from my personal experience as being a George. But I’m sure that there’s a lot of Marys out there, that really think that they’ve been put upon or ignored by the Georges. Now that Mary understands that George did not realize he was doing it. It’s really sad when you think that somebody is ignoring your wishes.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: Yeah.

Gabe Howard: And as you said, her gut was telling her that George was ignoring her rather than what was actually happening, which was George misunderstood. One of the things you talk about in your book is developing mental fitness. And we want to overcome the dangerous judgment errors of cognitive bias because they’re wrecking our relationships. What is mental fitness?

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: Mental fitness is the same thing as physical fitness. So we talked a little bit earlier about our ability to restrain ourselves from eating that dozen donuts, because then otherwise you’re really in trouble at this point in the world. You needed to develop a good approach to a healthy diet in order to address this. So you had to have physical fitness. Part of physical fitness is having a good diet. And it takes so much effort to have a good diet in this modern world because it doesn’t pay our capitalist society, all of these companies, for you to have a good diet, It pays them much better for you to eat all the sugar and processed food, which is exactly what caused you to have bad diet, obesity, various diabetes, heart disease, all those sorts of problems. The society is set against you. The capitalist marketplace is set against your having a healthy diet overall, and you have to work really hard to have a good diet. So that’s the part of physical fitness. Another part of physical fitness is, of course, is working out. Not sitting on your couch and watching Netflix all day, no matter how much Netflix might want you to do that.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: That is not a good way of having exercise, which is another important part of physical fitness. You need to put on your sweats and go to the gym. And, you know, right now, maybe in the coronavirus, get some form exercise machine and exercise at home. That is hard to do. Think about how hard it is to have physical fitness, to do the healthy diet and healthy exercises. It’s just as hard and just as important to have mental fitness. Now, in this current modern world where we’re spending more time at home because of the coronavirus, working more with our mind than with our body, it’s even more important to have mental fitness. Meaning working out your mind, not being primitive, not being savage, but figuring out what are the dangerous judgment errors? What are the cognitive biases, the mental blind spots to which you as an individual are most prone to? And you need to work on addressing them. That is what mental fitness is about. You need to figure out where you’re screwing up in your relationships because of these mental blind spots and the kind of effective mental habits that can help you address this.

Gabe Howard: All right, Dr. Tsipursky, you’ve convinced me. What are some helpful suggestions to get us there?

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: So the mental habits, there are 12 mental habits that I describe in the book. So first, identify and make a plan to address all of these dangerous judgment errors. Two, be able to delay all of your decision making in your relationships, because it’s very tempting for us to immediately respond to an e-mail from someone with whom we’re in a relationship that caused us to be triggered. Instead, it might be much better for us to take some time and actually think about that response. Mindfulness meditation is actually very helpful for us to build up focus and focus is what’s necessary for us to delay our responses and to manage our response effectively. Then probabilistic thinking. It’s very tempting for us in relationships to think in black and white terms, good or bad, you know, something nice or not nice. Instead, we need to think much more in shades of gray and evaluate various scenarios and probabilities. Five, make predictions about the future. If you aren’t able to make predictions about the future, about what or how the other person will respond to things you do in the relationship, then you will not have a very good mental model of that person. And of course, that will hurt your relationship. So you can calibrate yourself and improve your ability to understand the other person by making predictions of how they will behave. Next, consider alternative explanations and options. It’s very tempting for us to blame the other person, have negative feelings, thoughts about the other person, just like Mary had negative thoughts about George’s behavior and George had negative thoughts about Mary’s behavior.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: None of them thought about the alternative explanations and options. You know, Mary didn’t think that George might have been misunderstanding her, missing the signals, instead of ignoring the signals. And the same thing with George about Mary. Consider your past experiences. There’s a reason a lot of people tend to get into the same kinds of bad relationships in the future as they did in the past. They don’t analyze the mistakes they made in the past and they don’t correct them. Consider a long term future when repeating scenarios. A lot of people get into a relationship just because of lust. They have this kind of desire for a dozen donuts and they don’t think about the long term consequences of getting into the relationship and the kind of situation, if this will be a series of repeating scenarios. Is this the kind of relationships that they want to have? Consider other people’s perspectives. That’s number nine. That’s very hard for us to do. It’s very easy to miss. We just think about ourselves and what we want to do and we don’t think about other people and what their aspirations are. Next, use an outside view to get an external perspective. Talk to other people, other people in your life who are trusted and objective advisors. George shouldn’t just talk to people who will say, yeah, you’re absolutely right, Mary is a jerk and vice versa. You should think about other people who would be trusted and objective, who will tell you, hey, you know, George, maybe you talk a little bit too much about yourself and here’s how Mary might be thinking about this.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: Then set a policy to guide your future self and your organization if you’re doing this as part of a business, as part of an organization. So what kind of policy do you want? If you’re George, what kind of policy do you want to have toward your dates? Maybe you want to make sure to not simply talk all this time about yourself, but make sure to early on in the date and throughout the date to ask the other person about themselves and have all of these habits, mental habits that will help you have a much more effective relationship. And finally make a pre-commitment. So that was the internal policy, this is the external policy. You want to make a commitment to achieve a goal that you want. So a common pre-commitment is let’s say you want to lose weight. You can tell your friends, people, and your romantic partners, whatever, that you want to lose weight and ask them to help you avoid eating the dozen donuts. So that they can tell you, hey, you know, maybe you shouldn’t be ordering two desserts when you’re out at a restaurant. One will do. So that pre-commitment will help your friends help you. So those 12 mental habits, those are the specific mental habits you can develop to develop mental fitness. Just like you develop certain habits to have good diet and good exercise, you need to have these 12 habits to develop good mental fitness to work out your mind.

Gabe Howard: Dr. Tsipursky, first, I really appreciate having you here. Where can our listeners find you and where can they find your book?

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: The Blindspots Between Us is available in bookstores everywhere. It’s published by a great traditional publisher called New Harbinger, one of the best psychology publishers out there. You can find out more about my work at DisasterAvoidanceExperts.com, DisasterAvoidanceExperts.com, where I help people address cognitive biases, these mental blind spots in professional settings, in their relationships and other areas. Also, you might especially want to check out DisasterAvoidanceExperts.com/subscribe for an eight video based module course on how to make the wisest decisions in your relationships and other life areas. And finally, I’m pretty active on LinkedIn. Happy to answer questions. Dr. Gleb Tsipursky on LinkedIn. G L E B T S I P U R S K Y.

Gabe Howard: Thank you, Dr. Tispursky. And listen up, everybody. Here’s what we need from you. If you like the show, please rate, subscribe, and review. Use your words and tell people why you like it. Share us on social media and once again, in the little description, don’t just tell people that you listen to the show. Tell them why you listen to this show. Remember, we have our own Facebook group at PsychCentral.com/FBShow. That will take you right there. And you can get one week of free, convenient, affordable, private online counseling anytime, anywhere, simply by visiting BetterHelp.com/PsychCentral. And we will see everybody next week.

Announcer: You’ve been listening to The Psych Central Podcast. Want your audience to be wowed at your next event? Feature an appearance and LIVE RECORDING of the Psych Central Podcast right from your stage! For more details, or to book an event, please email us at [email protected]. Previous episodes can be found at PsychCentral.com/Show or on your favorite podcast player. Psych Central is the internet’s oldest and largest independent mental health website run by mental health professionals. Overseen by Dr. John Grohol, Psych Central offers trusted resources and quizzes to help answer your questions about mental health, personality, psychotherapy, and more. Please visit us today at PsychCentral.com. To learn more about our host, Gabe Howard, please visit his website at gabehoward.com. Thank you for listening and please share with your friends, family, and followers.

from https://ift.tt/3hOsnNZ Check out https://peterlegyel.wordpress.com/

0 notes

Text

Podcast: Your Gut Instinct is Bad For Your Relationships

While caring for his wife as she struggled with a severe nervous breakdown, Dr. Gleb Tsipursky put the cognitive strategies he’d long been teaching others to work on his strained relationship. After seeing the incredible impact it had on his marriage as a whole, he decided to write a book to share these relationship-changing communication strategies.

Join us as Dr. Tsipursky explains why going with your “gut” can actually backfire and shares 12 practical mental habits you can begin using today for excellent communication.

We want to hear from you — Please fill out our listener survey by clicking the graphic above!

SUBSCRIBE & REVIEW

Guest information for ‘Gleb Tsipursky- Instinct Relationship’ Podcast Episode

Gleb Tsipursky, PhD, is a cognitive neuroscientist and behavioral economist on a mission to protect people from relationship disasters caused by the mental blind spots known as cognitive biases through the use of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)-informed strategies. His expertise comes from over fifteen years in academia researching cognitive neuroscience and behavioral economics, including seven as a professor at Ohio State University, where he published dozens of peer-reviewed articles in academic journals such as Behavior and Social Issues and Journal of Social and Political Psychology. It also stems from his background of over twenty years of consulting, coaching, speaking, and training on improving relationships in business settings as CEO of Disaster Avoidance Experts. A civic activist, Tsipursky leads Intentional Insights, a nonprofit organization popularizing the research on solving cognitive biases, and has extensive expertise on translating the research to a broad audience. His cutting-edge thought leadership was featured in over 400 articles and 350 interviews in Time, Scientific American, Psychology Today, Newsweek, The Conversation, CNBC, CBS News, NPR, and more. A best-selling author, he wrote Never Go With Your Gut, The Truth Seeker’s Handbook, and Pro Truth. He lives in Columbus, OH; and to avoid disaster in his personal life, makes sure to spend ample time with his wife.

About The Psych Central Podcast Host

Gabe Howard is an award-winning writer and speaker who lives with bipolar disorder. He is the author of the popular book, Mental Illness is an Asshole and other Observations, available from Amazon; signed copies are also available directly from the author. To learn more about Gabe, please visit his website, gabehoward.com.

Computer Generated Transcript for ‘Gleb Tsipursky- Instinct Relationship’ Episode

Editor’s Note: Please be mindful that this transcript has been computer generated and therefore may contain inaccuracies and grammar errors. Thank you.

Announcer: You’re listening to the Psych Central Podcast, where guest experts in the field of psychology and mental health share thought-provoking information using plain, everyday language. Here’s your host, Gabe Howard.

Gabe Howard: Hello, everyone, and welcome to this week’s episode of The Psych Central Podcast. Calling into the show today, we have Dr. Gleb Tsipursky. Dr. Tispursky is on a mission to protect leaders from dangerous judgment errors known as cognitive biases by developing the most effective decision-making strategies. He is the author of The Blindspots Between Us, and he’s a returning guest. Dr. Tsipursky, welcome to the show.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: Thanks so much for having me on again, Gabe. It’s a pleasure.

Gabe Howard: Well, I’m very excited to have you on, because today we’re going to be talking about how our mental blind spots can damage our relationships and how to defeat these blind spots to save our relationships. I think this is something a lot of people can really relate to because we all very much care about our relationships.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: We do, but we think too little about the kind of mental blind spots that devastate our relationships. I mean, there’s a reason about 40% of marriages in the US end in divorces. And there is a reason that so many friendships break apart due to misunderstandings and conflicts that don’t need to happen. And when I see people doing that, running into these sorts of problems, they are just suffering in needless, unnecessary way. And that really harms them, and that really kind of breaks my heart. So that’s why I wrote this book.

Gabe Howard: We think about the term cognitive bias and there’s just so many psychological terms that basically say the way that your body feels is lying to you. That just because something makes you feel good doesn’t make it good. And just because something feels bad doesn’t make it bad. And I know that you’ve done excellent work in helping business leaders understand that. And this book is sort of an extension of that work in helping people understand that just because your friend or lover or spouse makes you feel bad doesn’t make it bad. Is that what you’re trying to tie together here?

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: I am, and this work actually emerged from where my wife, about five years ago, had a nervous breakdown, major nervous breakdown, where she was in a pretty terrible spot. So like you said, I’ve been doing consulting, coaching, training for business leaders for over 20 years now. And I’m a Ph.D. in cognitive neuroscience, behavioral economics. I’ve taught at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and at Ohio State as a professor for fifteen years. Now, at that point when my wife had a nervous breakdown, that was pretty terrible. So she was just crying for no reason, anxious for no reason. No reason that she was aware of. And that was really bad. She couldn’t work, she couldn’t do anything. I had to become her caretaker. And that was a really big strain on a relationship. I knew about these strategies, which I was already teaching to business leaders, and I started applying them toward our relationship. And we started to work through some of these strains in our relationship using the strategies. And so seeing the kind of impact that they had on our marriage and where they pretty much saved our marriage, definitely would not have been able to cope without these strategies. I decided that it would be a good time to write a book for a broader audience about personal relationships, romantic life, friendship, community, civic engagement, all of those sorts of relationships that are really damaged by the blind spots we have between us as human beings that can really be saved if we just are more aware of these blind spots and know about the research based tactics to address these blind spots.

Gabe Howard: As I’m sitting here listening to you, I completely agree with you, I know your educational background. I know the research that you’ve put into it. I’ve read your books and I believe you, Dr. Tsipursky. But there’s this large part of me that’s like, wait a minute, we’re supposed to trust our heart and trust our gut, especially in romantic relationships, love at first sight. I mean, every romantic comedy is based on this butterflies in the stomach. So the logical part of me is like Dr. Tsipursky, spot on. But the I want to fall in love in this magical way part of me is like, don’t bring science into this. And I imagine you get this a lot, right, because love isn’t supposed to boil down to science. What do you say to that?

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: Well, I say it’s just like exactly the kind of love we feel for a box of dozen donuts. You know, when we see them, when we see that box of dozen donuts, we just have this desire in our heart and our gut. We feel it’s the right thing to do to just gorge on those donuts. They look delicious and it’s yummy. And wouldn’t it be lovely to eat all those donuts, right? Well, I mean, what would happen to you after that?

Gabe Howard: Right.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: That would not be a good consequence for you. You know that. You know that, you know, five minutes after you finished gorging yourself on those donuts or eating a whole tub of ice cream or whatever your poison is, that you would be regretting it. And that is the kind of experience that we have where our body, our heart, our mind, or our feelings, whatever it comes from, those sensations, they lie to us. They deceive us about what’s good for us. And that all comes from how our emotions are wired. They’re not actually wired for the modern environment. That’s the sucky thing. They’re wired for the savannah environment. When we lived in small tribes of hunter-gatherers, fifteen people to 150 people. So in that environment, when we came across a source of sugar, honey, apples, bananas, it was very important for us to eat as much of it as possible. And that’s what our emotions were for. We are the descendants of those who were successfully able to gorge themselves on all the sugar that they came across, all the honey. And therefore, they survived and those who didn’t, didn’t. That’s an inborn instinct in us. That’s a genetic instinct. Now, in the current modern environment, it leads us in very bad directions because we have way too much sugar in our environment for our own good.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: So if we eat too much of it, we get fat. That’s bad for us. There’s a reason there’s an obesity epidemic here in the US and actually around the world in countries that adopt the US diet. And so this is why you want to understand that your feelings are going to be lying to you around food, around what kind of food you want to eat. In the same way, your feelings, the current research is showing very clearly, that your feelings are going to be lying to you about other people because our feelings are adapted to the tribal environment, when we lived in those small tribes. They are a great fit if you happen to live in a small tribe in the African savannah. But for all of you who are not listening to this podcast in a small little cave in the African savannah, they’re going to be a terrible fit for you. It’s really going to cause you to make really wrong, terrible decisions for your long term good. Because these natural, primitive, savage feelings are not what you want to be using for modern, current environment.

Gabe Howard: There’s a phrase and you reference it as well. Marketers say you can’t go wrong telling people what they want to hear, and that’s a great marketing concept to sell, you know, cereal. But it’s not such a great concept if you’re trying to encourage people to fall in love, get married or make decisions. Because if you buy a cereal that you don’t like, eh, you’re out four bucks, right. You’re out, you know, five bucks, big deal. You never eat the cereal again. But if you wreck a relationship that is good or you enter into a relationship that’s bad, this has real long term consequences.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: Right now, in the current environment where we don’t realize that go with your heart and follow your gut on the romantic relationships is horrible advice that will devastate your relationships, no matter how uncomfortable you feel about me saying that. People like Tony Robbins, I mean, he says be primal, be savage. You know, follow your intuition. That’s an essential message for people like Tony Robbins or Dr. Oz or whatever. All those other people who are on those stages and who millions of people listen to. It’s very comfortable to hear that message because you want to follow your gut. You feel good about it. Just like it feels comfortable, it feels delightful to eat those dozen donuts. It feels delightful, feels comfortable to go with your gut and follow your intuitions in your relationships, because that is what feels good. It doesn’t feel comfortable at all, you really have to go outside of your comfort zone to do the difficult thing and step back from your intuitions and from your feelings and say, hey, I might be wrong about this. This might not be the right move. I might not want to enter into this relationship or I might want to stop this relationship. That’s actually not good for me. But people don’t want to hear that. These people who tell you this advice, they actually are leading you in very bad directions, very harmful, very dangerous directions. Research shows clearly that they’re wrong.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: And if you don’t want to screw up your relationships and you’re not going to be part of the 40% whose marriages end up in divorce and whose other sorts of relationships are devastated. So this is something that you need to realize that you are going to be really shooting yourself in the foot if you follow the advice of to be primal, to be savage. Even though it feels very uncomfortable to hear what I’m saying right now. Of course, it goes against your intuitions. It doesn’t feel comfortable and it will never feel comfortable. Just like there are lots of unscrupulous food companies that sell you a box of dozen donuts when they really should be selling you a box of two donuts. I mean, that’s the healthy thing in the modern environment. We know that. That’s what doctors advise us, but it’s very hard to stop it when we have a box of dozen donuts. Well, why then do companies sell us a box of dozen donuts? Because they make a lot more money doing this then when they sell you one donut or two donuts. So the relationship gurus, they make a whole lot more money than people who tell you to actually do the right but uncomfortable thing. The simple, counterintuitive, effective strategies that help you address your relationships by defeating these mental blind spots and helping you save your relationships.

Gabe Howard: We’ll be right back after these messages.

Sponsor Message: This episode is sponsored by BetterHelp.com. Secure, convenient, and affordable online counseling. Our counselors are licensed, accredited professionals. Anything you share is confidential. Schedule secure video or phone sessions, plus chat and text with your therapist whenever you feel it’s needed. A month of online therapy often costs less than a single traditional face to face session. Go to BetterHelp.com/PsychCentral and experience seven days of free therapy to see if online counseling is right for you. BetterHelp.com/PsychCentral.

Gabe Howard: And we’re back discussing how our mental blind spots can damage our relationships with Dr. Gleb Tsipursky. One of the things I like about your book is that you talk about the illusion of transparency and you have a story that sort of surrounds it to bring this to the forefront so that people can understand it. Can you talk about the illusion of transparency and can you share the story that’s in your book?

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: Happy to. So the story was of two casual acquaintances of mine. They went out on a date together. George and Mary, when they went on the date, George, he thought it was wonderful. Mary was so understanding, so interested, listened to him so well. And George told Mary all about himself. He felt that Mary really understood him, unlike so many of the women that he dated. So as they parted for the night, they agreed to schedule another date soon. Well, the next day, George texted Mary, but Mary didn’t text back. So, George waited for a day and sent Mary a Facebook message. But she didn’t respond to him. Even though George noticed that she saw the Facebook message. He sent her an e-mail then. But Mary maintained radio silence. Eventually, he gave up trying to contact her. He was really disappointed, and he thought that, just like all of these other women, how can he be so wrong about her? So why didn’t Mary write back or respond back? Well, she had a different experience than George on the date. Mary was polite and shy and she felt really overwhelmed from the start of a date with George being so extroverted and energetic, telling her all about himself, his parents, job, friends, not asking her anything about herself.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: And she thought, you know, why would I date someone who overwhelms me like that? Doesn’t really care about what I think? She politely listened to George, not wanting to hurt his feelings. And she told George, she would go out with him again, but she had absolutely no intention of doing so. I learned about this, the really different viewpoints of Mary and George, because I knew both of them as casual acquaintances. George, after the date, started complaining to people around him, including me, about Mary’s refusal to respond to the messages. That he thought at least went very well. And George felt that he was genuinely sharing and Mary did wonderful listing so he was confused and upset. I privately then went to Mary, asked Mary about, hey, what’s up? What happened? And she told me her side of the story. She told me that she sent a lot of nonverbal signals of her lack of interest in what he was saying to her. But George really failed to catch the signals. Mary perceived him as oversharing and herself as behaving very politely until she could leave. Now, that’s the story. That’s the nature of the story. You might feel that it’s problematic for Mary to avoid responding to George’s texts.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: But you have to realize that there are tons of Marys out there who behave this way due to a combination of shyness, politeness, and conflict avoidance. That’s the kind of people they are. They’re kind of anxious about conflict. But at the same time, there are so many Georges, they are very extroverted, they’re very energetic. And as a result, they don’t read nonverbal signals from others very well at all. In this case, both George and Mary fell into the illusion of transparency. This is one of the most common mental blind spots or cognitive biases. The illusion of transparency describes our tendency to greatly overestimate the extent to which others understand our mental patterns, what we feel and what we think. It’s one of the many biases that cause us to feel, think, and talk past each other. And so this is the big problem for us, the illusion of transparency, because if you feel that, like George felt, that Mary understands him and Mary feels like I’m sending these very clear signals, why does this guy keep being a jerk and not responding to them? That is something super dangerous for relationships, harms a great deal of relationships when we misunderstand the extent to which other people get us.

Gabe Howard: One of the things that I want to focus in on is that she said that she was sending non verbals. On one hand, I am guilty of missing the nonverbal. So I’m going to tend to take Georgia’s side in this, which is that she didn’t speak up. She didn’t say anything, and instead she hinted. And it sounds like what you’re saying is that she felt in her gut that her nonverbals, her hinting, were enough and that Georgia’s lack of responding made him rude.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: Mm-hmm.

Gabe Howard: But probably from George’s side, as you said, George’s like, she said nothing. I carried on. And now she’s blaming me. So now we’ve got both of those sides. Now, they’re not going to work out as a romantic couple.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: Clearly.

Gabe Howard: we get it. It’s a bummer. But let’s pretend for a moment that you are much more invested, Dr. Tsipursky, in George and Mary than you actually are. And you’re like, oh, my God, if they can just get over this one tiny little hump, they will just be a beautiful couple forever. And I know you’re not a therapist, but if you could sit George and Mary down and say, listen, you two are actually a perfect couple. But you’ve let this primitive nonsense get in the way. How would you help them get over this hump so they could see that, actually, they do have quite a bit in common?

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: Well, I would think that one of the things they need to work on is let’s say they have, share a lot of interests and they have very similar values. They have a lot of differences in their communication styles. That will be a big challenge. First of all, working on the illusion of transparency, they need to be much more humble about the idea that the other person understands them, about their ability to send signals correctly. The essence of the illusion of transparency is that when we think we’re sending a signal, a message to other people, we think the other person gets it 100%. That’s just how it feels because we feel OK, we’re sending this message. Therefore, the other people understand it because we are sending it.

Gabe Howard: Right.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: We are way too confident about our own ability to be good communicators. And that is the underlying essence of the illusion of transparency. Everyone, all of us, and especially George and Mary, need to develop a great deal more humility about their ability to send the signals, whether verbal or nonverbal and have those signals be received appropriately. So that’s kind of one thing to work on. The other things to work on would be the differences in communication styles where Mary is clearly shy., conflict-avoidant. So she’s very unlikely to speak up just because of that personality. It will take her a great deal of emotional labor to speak up in these areas. So perhaps that she can, instead of speaking up, because specifically verbalizing things is pretty difficult for many people. She can have a nonverbal signal that’s much more clear, you know, raising her hand in some way to indicate that, you know, hey, I’m getting overwhelmed. We need to pause or something like that. So some way that you can clearly indicate that she needs a break and that the conversation perhaps is not leading to where she wants it to lead and that George needs to stop talking. And George needs to, by contrast, to be much more aware and clearly reading Mary’s signals of interest and not interest. Because, you know, George is a raconteur. He likes telling stories. He likes sharing about himself. He likes sharing about everything. And he just kind of does overwhelm people. Knowing him as a casual acquaintance, he’s kind of the life of the party. But life is not always a party.

Gabe Howard: So, you know, like I can absolutely relate to George, you know, it’s not an accident that I’m a speaker, a podcaster, or a writer. All of these things involve being the center of attention and sharing and talking. So I really can relate to George. And that’s kind of why I brought it up, because I have a lot of Marys in my life.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: Mm-hmm.

Gabe Howard: And I was completely unaware that I was overwhelming people because I just assumed that people would tell me to stop or something. I just didn’t know. So when I became older and more understanding and more socially adept, I realized that, oh, wow, people think that I’m ignoring their wishes. And that’s kind of why I want to touch on it. And obviously, I can only speak from my personal experience as being a George. But I’m sure that there’s a lot of Marys out there, that really think that they’ve been put upon or ignored by the Georges. Now that Mary understands that George did not realize he was doing it. It’s really sad when you think that somebody is ignoring your wishes.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: Yeah.

Gabe Howard: And as you said, her gut was telling her that George was ignoring her rather than what was actually happening, which was George misunderstood. One of the things you talk about in your book is developing mental fitness. And we want to overcome the dangerous judgment errors of cognitive bias because they’re wrecking our relationships. What is mental fitness?

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: Mental fitness is the same thing as physical fitness. So we talked a little bit earlier about our ability to restrain ourselves from eating that dozen donuts, because then otherwise you’re really in trouble at this point in the world. You needed to develop a good approach to a healthy diet in order to address this. So you had to have physical fitness. Part of physical fitness is having a good diet. And it takes so much effort to have a good diet in this modern world because it doesn’t pay our capitalist society, all of these companies, for you to have a good diet, It pays them much better for you to eat all the sugar and processed food, which is exactly what caused you to have bad diet, obesity, various diabetes, heart disease, all those sorts of problems. The society is set against you. The capitalist marketplace is set against your having a healthy diet overall, and you have to work really hard to have a good diet. So that’s the part of physical fitness. Another part of physical fitness is, of course, is working out. Not sitting on your couch and watching Netflix all day, no matter how much Netflix might want you to do that.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: That is not a good way of having exercise, which is another important part of physical fitness. You need to put on your sweats and go to the gym. And, you know, right now, maybe in the coronavirus, get some form exercise machine and exercise at home. That is hard to do. Think about how hard it is to have physical fitness, to do the healthy diet and healthy exercises. It’s just as hard and just as important to have mental fitness. Now, in this current modern world where we’re spending more time at home because of the coronavirus, working more with our mind than with our body, it’s even more important to have mental fitness. Meaning working out your mind, not being primitive, not being savage, but figuring out what are the dangerous judgment errors? What are the cognitive biases, the mental blind spots to which you as an individual are most prone to? And you need to work on addressing them. That is what mental fitness is about. You need to figure out where you’re screwing up in your relationships because of these mental blind spots and the kind of effective mental habits that can help you address this.

Gabe Howard: All right, Dr. Tsipursky, you’ve convinced me. What are some helpful suggestions to get us there?

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: So the mental habits, there are 12 mental habits that I describe in the book. So first, identify and make a plan to address all of these dangerous judgment errors. Two, be able to delay all of your decision making in your relationships, because it’s very tempting for us to immediately respond to an e-mail from someone with whom we’re in a relationship that caused us to be triggered. Instead, it might be much better for us to take some time and actually think about that response. Mindfulness meditation is actually very helpful for us to build up focus and focus is what’s necessary for us to delay our responses and to manage our response effectively. Then probabilistic thinking. It’s very tempting for us in relationships to think in black and white terms, good or bad, you know, something nice or not nice. Instead, we need to think much more in shades of gray and evaluate various scenarios and probabilities. Five, make predictions about the future. If you aren’t able to make predictions about the future, about what or how the other person will respond to things you do in the relationship, then you will not have a very good mental model of that person. And of course, that will hurt your relationship. So you can calibrate yourself and improve your ability to understand the other person by making predictions of how they will behave. Next, consider alternative explanations and options. It’s very tempting for us to blame the other person, have negative feelings, thoughts about the other person, just like Mary had negative thoughts about George’s behavior and George had negative thoughts about Mary’s behavior.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: None of them thought about the alternative explanations and options. You know, Mary didn’t think that George might have been misunderstanding her, missing the signals, instead of ignoring the signals. And the same thing with George about Mary. Consider your past experiences. There’s a reason a lot of people tend to get into the same kinds of bad relationships in the future as they did in the past. They don’t analyze the mistakes they made in the past and they don’t correct them. Consider a long term future when repeating scenarios. A lot of people get into a relationship just because of lust. They have this kind of desire for a dozen donuts and they don’t think about the long term consequences of getting into the relationship and the kind of situation, if this will be a series of repeating scenarios. Is this the kind of relationships that they want to have? Consider other people’s perspectives. That’s number nine. That’s very hard for us to do. It’s very easy to miss. We just think about ourselves and what we want to do and we don’t think about other people and what their aspirations are. Next, use an outside view to get an external perspective. Talk to other people, other people in your life who are trusted and objective advisors. George shouldn’t just talk to people who will say, yeah, you’re absolutely right, Mary is a jerk and vice versa. You should think about other people who would be trusted and objective, who will tell you, hey, you know, George, maybe you talk a little bit too much about yourself and here’s how Mary might be thinking about this.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: Then set a policy to guide your future self and your organization if you’re doing this as part of a business, as part of an organization. So what kind of policy do you want? If you’re George, what kind of policy do you want to have toward your dates? Maybe you want to make sure to not simply talk all this time about yourself, but make sure to early on in the date and throughout the date to ask the other person about themselves and have all of these habits, mental habits that will help you have a much more effective relationship. And finally make a pre-commitment. So that was the internal policy, this is the external policy. You want to make a commitment to achieve a goal that you want. So a common pre-commitment is let’s say you want to lose weight. You can tell your friends, people, and your romantic partners, whatever, that you want to lose weight and ask them to help you avoid eating the dozen donuts. So that they can tell you, hey, you know, maybe you shouldn’t be ordering two desserts when you’re out at a restaurant. One will do. So that pre-commitment will help your friends help you. So those 12 mental habits, those are the specific mental habits you can develop to develop mental fitness. Just like you develop certain habits to have good diet and good exercise, you need to have these 12 habits to develop good mental fitness to work out your mind.

Gabe Howard: Dr. Tsipursky, first, I really appreciate having you here. Where can our listeners find you and where can they find your book?

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: The Blindspots Between Us is available in bookstores everywhere. It’s published by a great traditional publisher called New Harbinger, one of the best psychology publishers out there. You can find out more about my work at DisasterAvoidanceExperts.com, DisasterAvoidanceExperts.com, where I help people address cognitive biases, these mental blind spots in professional settings, in their relationships and other areas. Also, you might especially want to check out DisasterAvoidanceExperts.com/subscribe for an eight video based module course on how to make the wisest decisions in your relationships and other life areas. And finally, I’m pretty active on LinkedIn. Happy to answer questions. Dr. Gleb Tsipursky on LinkedIn. G L E B T S I P U R S K Y.

Gabe Howard: Thank you, Dr. Tispursky. And listen up, everybody. Here’s what we need from you. If you like the show, please rate, subscribe, and review. Use your words and tell people why you like it. Share us on social media and once again, in the little description, don’t just tell people that you listen to the show. Tell them why you listen to this show. Remember, we have our own Facebook group at PsychCentral.com/FBShow. That will take you right there. And you can get one week of free, convenient, affordable, private online counseling anytime, anywhere, simply by visiting BetterHelp.com/PsychCentral. And we will see everybody next week.

Announcer: You’ve been listening to The Psych Central Podcast. Want your audience to be wowed at your next event? Feature an appearance and LIVE RECORDING of the Psych Central Podcast right from your stage! For more details, or to book an event, please email us at [email protected]. Previous episodes can be found at PsychCentral.com/Show or on your favorite podcast player. Psych Central is the internet’s oldest and largest independent mental health website run by mental health professionals. Overseen by Dr. John Grohol, Psych Central offers trusted resources and quizzes to help answer your questions about mental health, personality, psychotherapy, and more. Please visit us today at PsychCentral.com. To learn more about our host, Gabe Howard, please visit his website at gabehoward.com. Thank you for listening and please share with your friends, family, and followers.

from https://ift.tt/3hOsnNZ Check out https://daniejadkins.wordpress.com/

0 notes

Text

Podcast: Your Gut Instinct is Bad For Your Relationships

While caring for his wife as she struggled with a severe nervous breakdown, Dr. Gleb Tsipursky put the cognitive strategies he’d long been teaching others to work on his strained relationship. After seeing the incredible impact it had on his marriage as a whole, he decided to write a book to share these relationship-changing communication strategies.

Join us as Dr. Tsipursky explains why going with your “gut” can actually backfire and shares 12 practical mental habits you can begin using today for excellent communication.

We want to hear from you — Please fill out our listener survey by clicking the graphic above!

SUBSCRIBE & REVIEW

Guest information for ‘Gleb Tsipursky- Instinct Relationship’ Podcast Episode

Gleb Tsipursky, PhD, is a cognitive neuroscientist and behavioral economist on a mission to protect people from relationship disasters caused by the mental blind spots known as cognitive biases through the use of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)-informed strategies. His expertise comes from over fifteen years in academia researching cognitive neuroscience and behavioral economics, including seven as a professor at Ohio State University, where he published dozens of peer-reviewed articles in academic journals such as Behavior and Social Issues and Journal of Social and Political Psychology. It also stems from his background of over twenty years of consulting, coaching, speaking, and training on improving relationships in business settings as CEO of Disaster Avoidance Experts. A civic activist, Tsipursky leads Intentional Insights, a nonprofit organization popularizing the research on solving cognitive biases, and has extensive expertise on translating the research to a broad audience. His cutting-edge thought leadership was featured in over 400 articles and 350 interviews in Time, Scientific American, Psychology Today, Newsweek, The Conversation, CNBC, CBS News, NPR, and more. A best-selling author, he wrote Never Go With Your Gut, The Truth Seeker’s Handbook, and Pro Truth. He lives in Columbus, OH; and to avoid disaster in his personal life, makes sure to spend ample time with his wife.

About The Psych Central Podcast Host

Gabe Howard is an award-winning writer and speaker who lives with bipolar disorder. He is the author of the popular book, Mental Illness is an Asshole and other Observations, available from Amazon; signed copies are also available directly from the author. To learn more about Gabe, please visit his website, gabehoward.com.

Computer Generated Transcript for ‘Gleb Tsipursky- Instinct Relationship’ Episode

Editor’s Note: Please be mindful that this transcript has been computer generated and therefore may contain inaccuracies and grammar errors. Thank you.

Announcer: You’re listening to the Psych Central Podcast, where guest experts in the field of psychology and mental health share thought-provoking information using plain, everyday language. Here’s your host, Gabe Howard.

Gabe Howard: Hello, everyone, and welcome to this week’s episode of The Psych Central Podcast. Calling into the show today, we have Dr. Gleb Tsipursky. Dr. Tispursky is on a mission to protect leaders from dangerous judgment errors known as cognitive biases by developing the most effective decision-making strategies. He is the author of The Blindspots Between Us, and he’s a returning guest. Dr. Tsipursky, welcome to the show.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: Thanks so much for having me on again, Gabe. It’s a pleasure.

Gabe Howard: Well, I’m very excited to have you on, because today we’re going to be talking about how our mental blind spots can damage our relationships and how to defeat these blind spots to save our relationships. I think this is something a lot of people can really relate to because we all very much care about our relationships.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: We do, but we think too little about the kind of mental blind spots that devastate our relationships. I mean, there’s a reason about 40% of marriages in the US end in divorces. And there is a reason that so many friendships break apart due to misunderstandings and conflicts that don’t need to happen. And when I see people doing that, running into these sorts of problems, they are just suffering in needless, unnecessary way. And that really harms them, and that really kind of breaks my heart. So that’s why I wrote this book.

Gabe Howard: We think about the term cognitive bias and there’s just so many psychological terms that basically say the way that your body feels is lying to you. That just because something makes you feel good doesn’t make it good. And just because something feels bad doesn’t make it bad. And I know that you’ve done excellent work in helping business leaders understand that. And this book is sort of an extension of that work in helping people understand that just because your friend or lover or spouse makes you feel bad doesn’t make it bad. Is that what you’re trying to tie together here?

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: I am, and this work actually emerged from where my wife, about five years ago, had a nervous breakdown, major nervous breakdown, where she was in a pretty terrible spot. So like you said, I’ve been doing consulting, coaching, training for business leaders for over 20 years now. And I’m a Ph.D. in cognitive neuroscience, behavioral economics. I’ve taught at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and at Ohio State as a professor for fifteen years. Now, at that point when my wife had a nervous breakdown, that was pretty terrible. So she was just crying for no reason, anxious for no reason. No reason that she was aware of. And that was really bad. She couldn’t work, she couldn’t do anything. I had to become her caretaker. And that was a really big strain on a relationship. I knew about these strategies, which I was already teaching to business leaders, and I started applying them toward our relationship. And we started to work through some of these strains in our relationship using the strategies. And so seeing the kind of impact that they had on our marriage and where they pretty much saved our marriage, definitely would not have been able to cope without these strategies. I decided that it would be a good time to write a book for a broader audience about personal relationships, romantic life, friendship, community, civic engagement, all of those sorts of relationships that are really damaged by the blind spots we have between us as human beings that can really be saved if we just are more aware of these blind spots and know about the research based tactics to address these blind spots.

Gabe Howard: As I’m sitting here listening to you, I completely agree with you, I know your educational background. I know the research that you’ve put into it. I’ve read your books and I believe you, Dr. Tsipursky. But there’s this large part of me that’s like, wait a minute, we’re supposed to trust our heart and trust our gut, especially in romantic relationships, love at first sight. I mean, every romantic comedy is based on this butterflies in the stomach. So the logical part of me is like Dr. Tsipursky, spot on. But the I want to fall in love in this magical way part of me is like, don’t bring science into this. And I imagine you get this a lot, right, because love isn’t supposed to boil down to science. What do you say to that?

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: Well, I say it’s just like exactly the kind of love we feel for a box of dozen donuts. You know, when we see them, when we see that box of dozen donuts, we just have this desire in our heart and our gut. We feel it’s the right thing to do to just gorge on those donuts. They look delicious and it’s yummy. And wouldn’t it be lovely to eat all those donuts, right? Well, I mean, what would happen to you after that?

Gabe Howard: Right.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: That would not be a good consequence for you. You know that. You know that, you know, five minutes after you finished gorging yourself on those donuts or eating a whole tub of ice cream or whatever your poison is, that you would be regretting it. And that is the kind of experience that we have where our body, our heart, our mind, or our feelings, whatever it comes from, those sensations, they lie to us. They deceive us about what’s good for us. And that all comes from how our emotions are wired. They’re not actually wired for the modern environment. That’s the sucky thing. They’re wired for the savannah environment. When we lived in small tribes of hunter-gatherers, fifteen people to 150 people. So in that environment, when we came across a source of sugar, honey, apples, bananas, it was very important for us to eat as much of it as possible. And that’s what our emotions were for. We are the descendants of those who were successfully able to gorge themselves on all the sugar that they came across, all the honey. And therefore, they survived and those who didn’t, didn’t. That’s an inborn instinct in us. That’s a genetic instinct. Now, in the current modern environment, it leads us in very bad directions because we have way too much sugar in our environment for our own good.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky: So if we eat too much of it, we get fat. That’s bad for us. There’s a reason there’s an obesity epidemic here in the US and actually around the world in countries that adopt the US diet. And so this is why you want to understand that your feelings are going to be lying to you around food, around what kind of food you want to eat. In the same way, your feelings, the current research is showing very clearly, that your feelings are going to be lying to you about other people because our feelings are adapted to the tribal environment, when we lived in those small tribes. They are a great fit if you happen to live in a small tribe in the African savannah. But for all of you who are not listening to this podcast in a small little cave in the African savannah, they’re going to be a terrible fit for you. It’s really going to cause you to make really wrong, terrible decisions for your long term good. Because these natural, primitive, savage feelings are not what you want to be using for modern, current environment.

Gabe Howard: There’s a phrase and you reference it as well. Marketers say you can’t go wrong telling people what they want to hear, and that’s a great marketing concept to sell, you know, cereal. But it’s not such a great concept if you’re trying to encourage people to fall in love, get married or make decisions. Because if you buy a cereal that you don’t like, eh, you’re out four bucks, right. You’re out, you know, five bucks, big deal. You never eat the cereal again. But if you wreck a relationship that is good or you enter into a relationship that’s bad, this has real long term consequences.