#just as far as its engagement with well established fantasy tropes is concerned

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

i can’t believe i have to say this but dungeon meshi did not invent elves being assholes

#beep boop#it’s like. this isn’t a bad thing bc i think it’s well executed but it’s a pretty derivative series#just as far as its engagement with well established fantasy tropes is concerned#like it’s not that unique beyond having a refreshing style in terms of manga w/ mainstream overseas success#i love it i just feel like people gas it up as if it invented 100% of the concepts it uses

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shared Universe Blunders 4: Double Hell and the Sitcom Effect

(name suggestions welcome, this is a tentative essay)

The Worf Effect is named for Worf, a Klingon crewman in Star Trek, nominally one of the toughest and most martially-inclined of the crew. The Star Trek writers were prone to establishing villain cred by having the villain of the week beat up Worf. Repeated use of this trope made Worf look a lot less impressive, and undermined the narrative impact of "Space Fisticus is strong enough to defeat even Worf!"

I posit a similar Sitcom Effect: where a work has some kind of aliens (or elves, or kami, etc) who are initially far from human, and the writers are prone to playing this for laughs by having the aliens engage in an episode of humanlike sitcom behavior that's made extra funny by the contrast with the rest of their culture. Repeated use of this trope, though, makes the aliens look increasingly human because they keep having human sitcom moments, and over time they get worn down and rounded off to merely "Rubber Forehead Aliens" -- humans in space with a couple of cultural quirks and pointy ears.

If the Dark Lord Dr'ddnite has raised a horde of the walking dead who do not know pain or fear, and he threatens to conquer the land with his tireless skeleton armies that replenish themselves by every battle they win -- it's funny to see the skeletons suddenly form a labor union and go on strike until Dr'ddnite agrees to overtime pay for their tireless marching, but it undermines the characterization that made them so threatening. It's a kind of joke which burns the worldbuilding.

And in a shared universe, long-running setting, or kitchen sink fantasy, when the writer has made Hell a punchline one too many times, the easy way out is to introduce a Double Hell.

(From Penny Arcade.)

Serial powerlevel escalation is a well-known problem that I shan't elaborate on here; Double Hell looks to me a bit like its converse. Instead of constantly escalating the threat of the next enemy coming up, the writers are constantly turning the current enemy into a source of cheap laughs, and have to pull out a bigger one. And as the comic suggests, this easily leads to Double Hell getting sitcomized in turn, losing its punch.

It's convenient for authors to introduce some kind of mindless ravening horde enemy, so the protagonists have mooks to scythe through without moral concerns. The mindless ravening horde can also be convenient for the in-character reason that the Dark Lord doesn't want soldiers that talk back, or doesn't want to risk named people dying that might be harder to replace.

But by the same token, it's convenient for authors to later humanize the mindless ravening horde anyway, showing that they're Just Folks Like Us after all, isn't this a heartwarming story of how we can overcome our differences and learn to work together against the Even Bigger Bad?

These two patterns can interact and loop, and have intermediate steps of repeated sitcom and retcon that perhaps look something like:

introduce demonic ravening horde antagonists -> they're not literally demonic, but they did choose to be an evil ravening horde -> they didn't individually choose it but the culture is self-perpetuating indoctrination -> the culture resulted from highly contingent unfortunate historical event -> the culture is being imposed on them right now by the Evil King -> hooray, the Evil King's gone and we can fix the culture -> they're just misunderstood -> introduce new demonic ravening horde antagonists.

This is somewhat speculative and idealized. I haven't seen a full cycle exactly like this. There's going to be local variation in implementation. I have seen bits and pieces cropping up often enough to form a hypothesis about this cycle of villain decay.

And as a villain faction passes through the retcon cycle, weird things happen with leftover policies and implications from the earlier stages. I've previously spoken about this post which I think is a good example of someone else running into it:

I’m playing Pathfinder: Kingmaker I am confused and alarmed by what this game considers Lawful Good [...] At one point, the troll king asked me why I broke into his castle and murdered his soldiers. I told him that his men also broke into human homes and murdered the inhabitants, and I just wanted to protect my people. This was the Lawful Neutral option. The Lawful Good option was to say that trolls are inherently evil, even if they don’t always seem that way, and they all have to be killed before they hurt anyone else. WTF.

Kingmaker is not strictly a "shared universe" but it's reborrowing enough classic names and recycling enough D&D to have similar problems, and I think part of what happened there is that trolls used to be a lot more evil ravening monsters that hungered for human flesh, so "eradicate the trolls" was labeled Lawful Good the way "eradicate smallpox" was, then some other writer reinvented the trolls as social, intelligent, castle-building humanoids with enough self-restraint to have morality debates instead of eating you. (I have not played Kingmaker myself, so I may be missing subtleties here.)

-

Another frequently-reinvented monster along these lines is vampires. Many old vampire stories are closer to what we might call "zombies" today: risen corpses seeking only to feed on the living, suffering from rot and rigor mortis. Dracula gave them class and refinement and healthier bodies, but made it clear that vampires were still Hell-damned wicked things, antichrists who recoiled from the crucifix and feared the sun.

Then we got a series of increasingly hands-off vampires who bought blood at the blood bank like respectable people, occasional pushback from other writers who gave faux-scientific explanations on how vampires feed on life essence that's only carried in fresh blood and fades in blood bank storage, and eventually there came Twilight with its sparkly vampires who could abstain from human blood entirely and restrict themselves to animal blood. Almost all the vampire-ness has been sitcom-ed out of them, they're hardly more than Maasai at that point.

(I admit to simplifying enormously over a vast literary history here.)

There is, furthermore, a special reason why mythical poetry ought not to attempt novelty in respect of its ingredients. What it does with the ingredients may be as novel as you please. But giants, dragons, paradises, gods, and the like are themselves the expression of certain basic elements in man’s spiritual experience. In that sense they are more like words – the words of a language which speaks the else unspeakable – than they are like the people and places of a novel. To give them radically new characters is not so much original as ungrammatical.

-C.S. Lewis, Preface to Paradise Lost

I do not entirely agree with Lewis, but "ungrammatical" is a way of attacking the issue that I appreciate. A vocabulary of standard fantasy elements is a convenience for author and reader both, which enables communication without having to explain the basic building blocks. There is nothing wrong with genre conventions.

A complex text may reasonably use some words in nonstandard ways that require explanation, and propose specific novel terms; but constant invention and redefinition of words is a bad sign.

(xkcd. Alt-text: "Except for anything by Lewis Carroll or Tolkien, you get five made-up words per story. I'm looking at you, Anathem.")

A potential refinement is that it's a bad sign if the redefinition of words goes in the direction of 1) concepts we already have a word for, 2) less specific and more bland concepts.

For ordinary words, this happened to "very" a long time ago and is now happening to "literally", both drifting from meaning precisely and non-metaphorically towards being generic intensifier words.

For fantasy creatures, the analogy is to humanwards drift and sitcomization.

(Footnote: Tolkien was making up entire foreign languages. There's only about five words used in his English context that I'd count as made-up: Hobbit, orc, mithril, palantir, and maybe half a point for "dwarves" which was until then mostly spelled "dwarfs".)

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anonymous asked: I really enjoy your erudite and literary posts about James Bond in your blog very much. Your most recent post about Connery as best cinematic Bond and Dalton as the best literary Bond was brilliant. Although the PC brigade have been inching towards making Bond a woman or even non-white, Ian Fleming’s legacy of a suave but cold hearted English gentleman spy hasn’t been completely trashed. As someone familiar with Fleming literary lore can you also tell me where was James Bond educated? Was it Oxford or Cambridge? I was having a discussion over Zoom with friends and the Oxonians like myself thought it was Oxford because in Casino Royale with Daniel Craig it’s made very plain it was Oxford. Your thoughts?

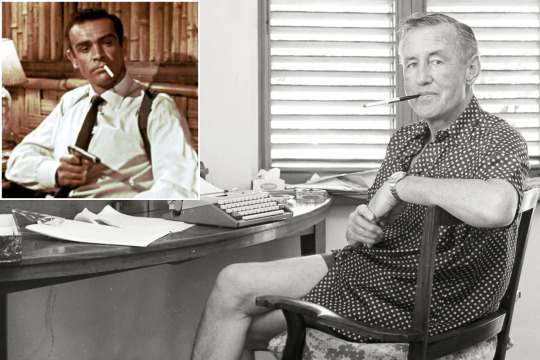

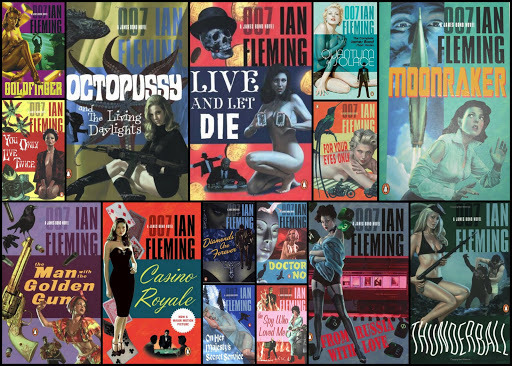

I appreciate your kind words about my posts on James Bond and his creator Ian Fleming. It’s very hard to ignore the cinematic James Bond because he is very much an icon of our modern culture that needs no translation to transcend across cultures. Alongside Sherlock Holmes, another British literary and cinematic export, the name alone speak for itself.

James Bond appeals to both genders very well.

For the men, Bond dresses well and lives in a care free way. He is both ferociously intelligent and resourceful to get out of any tight corner. He drives incredible cars (from the incredibly stylish Aston Martin DB5 to the incredibly awful AMC Hornet) and uses awesome technology (he is the archetypal boy with toys). He's not afraid to get down in the dirt to fight or engage in lethal gun-play and spectacular car chases. He sleeps with beautiful women, regardless how strong and independent they are (or even lesbian if we’re being honest about Pussy Galore).

For us ladies, while he's not averse to action, he's also a cultured gentleman with suave and sophisticated manners. He's also a generally pretty good looking guy. In many ways, he's a conventional male ideal. So while his conventional good looks and manners aren't for everyone, they hit right the sweet spot of what women like. For everyone, he's a spy! Not at a grey real world nondescript spy, but a cool spy fighting larger than life bad guys whose bland sartorial choices scream mad super villain. It's a very black and white world that James Bond lives in. These bad guys truly are villainous in the desire to re-order humanity, and we need a debonair British MI6 agent to save us from these mad men who want to harm us by laying waste to a bonkers Armageddon.

When all is said and done I think that what makes James Bond so iconic across gender and generations is what Raymond Chandler wrote back in 1959, “every man wants to be James Bond and every woman wants to be with him”.

That sounds about right. Men want to be him, women want to be with him.

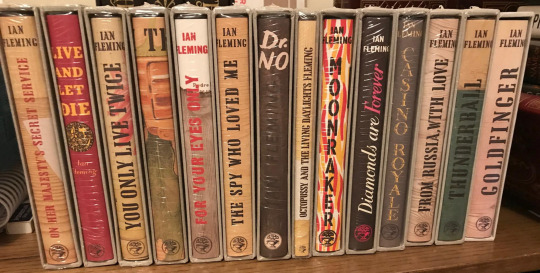

I know my first introduction to James Bond was through my grandfather on my Anglo-Scots father’s side who was a dashing gentleman in his day with a long rumoured hush hush work for Her Majesty’s government firmly shoved under the carpet to avoid further discussion that he - being self-effacing and humble - would find embarrassing that would paint him in any heroic light. Years later he had bought his Bahamas beach pile in Harbour Island out in the Caribbean for the family to rest up from cold winters in Britain. Amongst his immense stack of books dotted around the place were (and still are) first editions of Flemings novels which a few were signed by the author as he on occasion met Ian Fleming when he would sail over to Jamaica (they were also OEs which helped). We were not allowed to touch these but instead picked up the dog earred paperbacks that still retained their 60s musty smell.

On my teen sojourns there I would spend time along with my siblings just reading anything we could find to take to the beach or lounge around in a hammock or a chaise longue. That’s how I came to read the Fleming books - really out of necessity to avoid boredom on a beach (which isn’t really my thing as I prefer the rugged outdoors). But I was pleasantly surprised how well written the books were and I actually enjoyed the stories; it was a refreshing change from the more heavy literary tomes I was trying hard to wade through. As for the Bond films, I watched them on film nights at boarding school; I remember having a school girl crush on Connery, Dalton, and Brosnan.

There are many reasons for the successful longevity of James Bond in popular culture and literature but perhaps one of the most pertinent to our discussion is that James Bond is actually a blank slate and therefore malleable as a character and so he can capture the current zeitgeist in time.

This ability of the film to adapt to different generations while remaining relevant is an important factor for its longevity. For example, the early James Bond films were unashamedly sexist with characters using women as objects and discarding them. In the most recent James Bond films, certainly starting with Timothy Dalton, there is a subtle change in attitude with a few chauvinist attitudes.

James Bond today is more serious, seduces fewer women, and is more respectful towards women in his life, including his boss. This shows how the film changes concerning the rise of feminism in the West. For example, Miss Moneypenny used to be a minor character in the very first James Bond films. Today, she is more formidable and doesn’t tolerate sexist remarks.

Perhaps it is precisely because of this blank slate malleability that has allowed different actors that have been cast to play James Bond their own way - rather than get a straight like for like Scottish sounding actor to replacing Connery for example the film producers went across to Moore via Lazenby for example - and letting each actor imbue the super spy with different moods. They each added their own colour from the same broad palate to create different tones. However, each of these characters maintained the essential character that defines James Bond. The actors have broadly stayed true to the inherent mix of character and class associated with James Bond.

For this reason I have some empathy towards your concern that Bond would be held hostage to the current zeitgeist of white washing or genderising everything so as to avoid being a victim of cancel culture. But it’s only empathy because I feel there is a danger of misunderstanding just who James Bond is and what he represents.

What do I mean by this?

I mentioned James Bond is a malleable character to the point he’s presented as a blank slate. This is ‘literally’ true - certainly as far as the books go. Ian Fleming doesn’t tell us much about Bond other than his appearance in his books. Indeed - as I mentioned in my past blog post on Connery as the best Bond - Fleming wasn’t convinced by Connery as Bond. He was reported to have said, ‘I’m looking for Commander Bond and not an overgrown stuntman’ and even dismissed Connery as “that fucking truck driver”. Fleming has good reason to rage. His Bond as written in the books was someone like him.

Like Fleming, Bond was an Eton educated Englishman; an officer and a (rogue) gentleman who was a lieutenant-commander in Naval Intelligence. As Connery began to wow and win over Fleming as Bond, Fleming had a change of heart. Fleming in his later Bond books re-wrote a half-Scottish ancestry for Bond as a tribute to Connery’s portrayal. Bond’s Scottish father was a Royal Navy captain and later an arms dealer, Andrew Bond from Glencoe; and his mother, Monique Delacroix, was Swiss from an industrial family. Bond himself was born in Zurich. Bond isn’t English at all but half-Scots and half-Swiss according to literary canon.

So I mention this because the question who can play James Bond is not as straight forward as it might seem.

But clearly we now have a canon of work, both cinematically and in the literature, where we have base line of who Bond is - or what audiences could possibly suspend their disbelief and go with what is presented to them as James Bond.

I do vaguely remember the hullabaloo and hand wringing around Daniel Craig playing Bond because he didn’t conform to the traditional tall, dark, and handsome trope of James Bond super suave spy. People couldn’t get past his blond hair. Some still can’t. But in my humble opinion he has been an outstanding James Bond and has reimagined Bond in a fresh and exciting way. Craig is in fact mining the Fleming books for his characterisation of Bond as a suave, gritty, humourless killer of the books. Dalton got there before him but that’s a moot point. To our current generation Craig has modernised Bond and dusted 007 down from being a relic of the Cold War to being a relevant 21st Century super spy.

Can anyone play James Bond OO7? Yes and no. It’s arguing that two different things are one and the same. They are not. James Bond is separate from OO7.

Can a woman play Jane Bond or a black woman or non-white man play Black Bond? Respectfully, no. That’s not who James Bond is.

James Bond is a flesh and blood character with a specific genealogical history - whether in the books or on the screen. This Bond has literary back story that is canon and makes him who he is. Bond does transcend time - he can’t be 38 years old for over 75 years in the real world - but at the same time his character only makes sense when rooted in a specific historic context we know existed (and still exists) and not some wishy washy make believe fantasy of British society. He’s an Old Etonian and therefore an upper middle class male product of the British establishment that is identifiable in a very British cultural context.

Jane Bond would have to have gone to Cheltenham Ladies College, Benneden, or Roedean I suppose if we are talking about equivalence - but such girls’ boarding schools were not the breeding ground for future spies (more likely they married them or became trusted secretaries in the intelligence services as well as flower arranging in their Anglican parish church).

I believe they are letting in black pupils on bursaries at Eton these days to be more inclusive but again it’s an an exception not the rule and Eton doesn’t even get public credit for the inclusive work they try to do because it’s not well known.

Moreover we know Bond loses his Scottish-Swiss parents in a skiing accident. I don’t mean to sound racist but I ski a lot in Switzerland and I can say you don’t really find droves of non-white skiers on the slopes of Verbier or Zermatt. Of course there are a few but it’s the exception and not the norm. Again, I’m not trying to be racist but just point out some obvious things when it pertains to the credibility of character that underlines who Bond is. You pull one thread out of the literary biography and the danger is the rest of the tapestry will unravel.

Of course one could try and go for a Black Bond on screen and then hope there is a huge suspension of belief on the part of the audience. But I suspect it’s a bridge too far. It just doesn’t fit. Audiences around the world have an image of who Bond is - British at the very least but also male (damaged and flawed in many ways) and coming from a specific British social class background that serves as an entree to a closed world of English gentleman clubs, Savile Row, English sports cars, and the hushed corridors of Whitehall.

Any woke film maker with an ounce of creative vision and talent and one who is invested in this would be better off creating a new character entirely - with their own specific biography that is both believable and relatable. Can you imagine an American James Bond? What a ghastly thought. Or worse a Canadian one? Canadians are far too nice and far too apologetic to produce a cruel cold eyed killer. But look what clever film makers like Spielberg and Lucas did with Indiana Jones and even later Doug Liman did with Jason Bourne - both fantastic creations that are part of the cultural zeitgeist now.

Or look at Charlize Theron who plays a MI6/CIA/KGB triple agent in Atomic Blonde or Rebecca Ferguson as Ilsa Faust in any of the Mission Impossible movies. I would eagerly watch any movies with these two badass women on the screen. All this talk about making Bond a woman or even coloured is just lazy thinking at best and at worst kow towing to the populist tides of PC brigade.

But I firmly believe one can have a female and a person of colour portraying 007. This is because James Bond and OO7 are two different things entirely. Many mistakenly believe 007 is Bond’s own code name and specific alias to him alone.

007 is a license to kill for a very specialised kind of intelligence officer. Bond has that privilege for as long as he serves at the service of Her Majesty’s pleasure. His 007 license can be revoked - and it has been in the past Bond films - and he’s back to being a just another desk jockey civil servant in Whitehall. So my point is OO7 is not sacred to Bond’s identity. Bond could continue to be Bond even if M took away his 007 license to kill.

The origins of the Double O title may date to Fleming's wartime service in Naval Intelligence. According to World War Two historian Damien Lewis in his book Churchill's Secret Warriors, agents of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) were given a “0” prefix when they became "zero-rated" upon completion of training in how to kill. As part of his role as assistant to the head of naval intelligence, Rear Admiral John Godfrey (himself the inspiration for M), Fleming acted as liaison to the SOE.

In the novel Moonraker it’s established that the section routinely has three agents concurrently; the film series, beginning with Thunderball, establishes the number of OO agents at a minimum of 9. Fleming himself only mentions five OO agents in all. According to Moonraker, James Bond is the most senior of three OO agents; the two others were OO8 and OO11. The three men share an office and a secretary named Loelia Ponsonby. Later novels feature two more OO agents; OO9 is mentioned in Thunderball and OO6 is mentioned in On Her Majesty's Secret Service.

Other authors have elaborated and expanded upon the OO agents. While they presumably have been sent on dangerous missions as Bond has, little has been revealed about most of them. Several have been named, both by Fleming and other authors, along with passing references to their service records, which suggest that agents are largely recruited (as Bond was) from the British military's special forces.

Interestingly, In the novel You Only Live Twice, Bond was transferred into another branch and given the number 7777, suggesting there was no active agent 007 in that time; he is later reinstated as 007 in the novel The Man with the Golden Gun. As an aside, in Fleming's Moonraker, OO agents face mandatory retirement at 45 years old. However Sebastian Faulks's Devil May Care (an authorised Bond adventure from the Fleming estate and therefore arguably could be considered canon) features M giving Bond a choice of when to retire - which explains why Roger Moore (God bless) went past his sell by date.

In the films the OO section is a discrete area of MI6, whose agents report directly to M, and tend to be sent on special assignments and troubleshooting missions, often involving rogue agents (from Britain or other countries) or situations where an "ordinary" intelligence operation uncovers or reveals terrorist or criminal activity too sensitive to be dealt with using ordinary procedural or legal measures, and where the aforementioned discretionary "licence to kill" is deemed necessary or useful in rectifying the situation.

The World is Not Enough introduces a special insignia for the 00 Section. Bond's fellow OO agents appear receiving briefings in Thunderball and The World Is Not Enough. The latter film shows a woman in one of the 00 chairs. In Thunderball, there are nine chairs for the OO agents; Moneypenny says every 00 agent in Europe has been recalled, not every OO agent in the world. Behind the scenes photos of the film reveal that one of the agents in the chairs is female as well. As with the books, other writers have elaborated and expanded upon the OO agents in the films and in other media.

In GoldenEye, 006 is an alias for Alec Trevelyan; as of 2019, Trevelyan is the only OO agent other than Bond to play a major role in an EON Productions film, with all other appearances either being brief or dialogue references only.

In Casino Royale with Daniel Craig’s first outing as Bond, we see in the introduction the tense exchange between Bond and Dryden, a section chief whom Bond has been sent to kill for selling secrets.

James Bond: M really doesn't mind you earning a little money on the side, Dryden. She'd just prefer it if it wasn't selling secrets. Dryden: If the theatrics are supposed to scare me, you have the wrong man Bond. If M was so sure I was bent...she'd have sent a Double-O. Benefits of being Section Chief...I would know of anyone being promoted to Double-O status, wouldn't I? Your file shows no kills...and it takes - James Bond: - two. (flashback of Bond fighting Dryden's contact in a bathroom.)

The OO is just a coveted position and nothing to do with who occupies it. Ito use a topical comparative example it’s like a football team in which a new star player would be given an ex-player’s shirt number e.g. Messi wears Number 10 for Argentina which is heavily identified with the late great Maradona. So conceivably there would be no problem having a woman or anyone else play 007. I think it would be an interesting creative choice to have a woman or someone else play OO7 and Bond is out of the service and yet he has to work together with this new OO7 - the creative tension would be a refreshing twist on the canon.

Your question about James Bond’s Oxford or Cambridge education is more easier to answer.

It really depends again which Bond one is talking about. The literary James Bond or the cinematic Bond.

In the Fleming books, James Bond’s didn’t go to Oxford or Cambridge or any of the other great universities of Britain. In the books Bond’s education is not gone into much detail. We know he was raised overseas until he was orphaned at the age of 11 when his parents died in a mountaineering accident near Chamonix in the Alps. He is home schooled for a time by an aunt, Charmain Bond, in the English village of Pett Bottom before being packed off to boarding school at Eton around 12 years old. Bond doesn’t stay long as he gets expelled for playing around with a maid. He is then sent to his father’s boarding school in Scotland, Fettes College.

Bond is then briefly attends the University of Geneva - as Ian Fleming did - before being taught to ski in Kitzbühel. In 1941 Bond joins a branch of what was to become the Ministry of Defence and becomes a lieutenant in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, ending the war as a commander. Bond applies to M for a position within the "Secret Service", part of the HM Civil Service, and rises to the rank of principal officer. And that’s it.

In the cinematic Bond universe things get more complicated and even contentious as you alluded to in your question. It’s never made quite clear which of the two - Oxford or Cambridge - Bond attended because it depends on how much weight you attach to the lines being spoken in each of the films where it is raised.

In Tomorrow Never Dies, Bond is up at Oxford (New College to be exact since his Aston Martin DB5 was parked in the courtyard at the entrance). He is seen bedding a sexy Danish professor, Inga Bergstrom, to brush up on his Danish (to which Moneypenny on the phone retorts ‘You always were a cunning linguist’). But it’s definitely doesn’t mean Bond studied there as an undergraduate.

Casino Royale is the film many think yes, James Bond went to Oxford because it is mentioned by Vesper Lynd (Eva Green) as she sizes up Daniel Craig’s Bond on the train. Here is the full quote as said by Vesper Lynd, “All right... by the cut of your suit, you went to Oxford or wherever. Naturally you think human beings dress like that. But you wear it with such disdain, my guess is you didn't come from money, and your school friends never let you forget it. Which means you were at that school by the grace of someone else's charity - hence that chip on your shoulder. And since your first thought about me ran to "orphan," that's what I'd say you are.”

The thing to note is that it’s Vesper Lynd taunting Bond and even then she takes a wide stab by saying ‘Oxford or wherever’ because she doesn’t really know and Bond doesn’t oblige her with an answer.

That whole scene struck me as strange because she’s guessing by the cut of the suit it must be Oxford (or Cambridge). Bond is wearing an Italian suit (Brioni to be specific) and not and English Savile Row one that presumably someone of Bond’s taste and background would be sporting.

A more plausible answer if we are going by the cinematic Bond universe is Cambridge. Indeed it is stated explicitly by Bond himself. Can you guess?

You Only Live Twice which is has the distinction of being the only Bond film (as far as I can tell) from being set in just one country - Japan.

You remember the scene. Lieutenant commander James Bond has just had a briefing with M on board a submarine and is naturally flirting with Moneypenny on his way out. Moneypenny playfully tosses him a Japanese phrase book, saying he might need it.

“You forget,” Bond responds with an expression just short of a smirk as he tosses it back to her, “I took a first in oriental languages at Cambridge.”

So it seems James Bond is a Cambridge man.

A first means - as any British university student would know - first class honours. It’s the highest classification grade one can get in their undergraduate degree ie a ‘first’. Although at Cambridge, like Oxford, you can also get a double first in the part I and part II of the Tripos. Both universities also award first-class honours with distinction, informally known as a ‘Starred First’ (Cambridge) or a ‘Congratulatory First’ (Oxford).

Another oddity is he says ‘oriental languages’ when one got a degree in ‘oriental studies’ at the Oriental Faculty at Cambridge. That is until 2007 when Cambridge bowed to public and student pressure and chose to drop its Oriental Faculty label and instead adopted the name the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies. Oxford still hangs on to its name the Faculty of Oriental Studies.

My only reservation about crowing over an Oxonian is how truthful was Bond being with Moneypenny in this scene?

Is this line meant to be taken seriously or ironically? Most people seem to take it seriously, despite much of Connery's dialogue being obviously ironic and playful. Certainly, Bond is shown to have never been to Japan before and is incapable of saying anything in Japanese other than the odd "sayonara" and "arigato." But then again Bond does know the correct temperature sake is meant to be served at. So there’s that.

Or it could be Bond was speaking a half-truth. I know speaking from experience as someone who very nearly read asian languages instead of my eventual choice of Classics that ‘Oriental languages’ at the ex-Oriental faculty in Cambridge can mean many other languages e.g. Sanskrit, Hindi, Farsi, Hebrew, Arabic as well as Korean, Japanese and Chinese. It opens up so many other delicious possibilities for Bond. If he read Arabic then perhaps he’s being deeply ironic with Moneypenny (after all she would have drooled over read his MI6 personnel file).

If you think I’m losing my mind then ponder on the fact it was Roald Dahl who penned the screenplay of You Only Live Twice. Dahl was not above snark. Indeed pretty sure he would have got a starred first in snark at any university.

Of course the most obvious explanation is that it’s plot armour as a way for Bond to just get on with the story by suspending the audience belief. Why wouldn’t Bond know Japanese? He seems to know everything else imaginable.

However if it ever was it’s now become canon as EON - the production company behind the Bond films - have stated officially for the fandom that Bond’s official bio has it that he went to Eton and Cambridge, where he got a first in oriental languages. So that seems settled then.

In hindsight it makes perfect sense that Bond went to Cambridge since historically Cambridge has provided the bulk of the spies not just for Her Majesty’s service but also for the other side, the Russians - the so-called Cambridge Spies of Philby, Maclean, Burgess, Blunt, and Cairncross, and a host of other traitors. We seem to be an equal opportunities employment service.

I’m sorry to disappoint you and other Oxonians that despite what you might think James Bond didn’t attend Oxford. Believe me as a Cantabrigian it gives me no pleasure to say this…..too much.

Thanks for your question.

#ask#question#james bond#bond#film#cinema#ian fleming#oxford#cambridge#oxbridge#university#education#cancel culture#culture#society#britain#british#personal

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is Skyward Sword the Only Link and Zelda Romance Story?

https://ift.tt/eA8V8J

If you’re anything like most gamers from a certain era, you probably grew up assuming that Zelda and Link were in love. After all, he is a hero, she is a princess, he was a boy, she was a girl…can we make it any more obvious?

However, the truth of the matter is that nothing is quite that obvious when it comes to Link and Zelda’s relationship. Much like your relationship status on Facebook whenever you felt like stirring up a little drama, the relationship between Link and Zelda over the years has been decidedly complicated.

That’s part of the reason why Skyward Sword has always been one of the most interesting Zelda games from a lore perspective. After years of ambiguity, complications, winks, half-answers, and lingering questions, Skyward Sword gave us a Link and Zelda relationship that couldn’t possibly be interpreted as anything but romantic (even if there is some ambiguity regarding how their relationship ends). The game was even promoted with this “Romance Trailer” that highlights that aspect of the plot:

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

While there is very little debate regarding whether or not Skyward Sword is a Link and Zelda love story, there is a much more substantial (and far more interesting) debate to be had regarding whether or not it is the only real love story in Legend of Zelda history.

“Hold up,” you might be saying. “If Zelda and Link didn’t have a canonical romance until 2011, then why did I grow up believing that they were in love?”

Well, as we mentioned before, elements of the perceived romance between Zelda and Link can be attributed to the fact that most of the guys you see rescuing princesses in fantasy stories do tend to fall in love with them. It’s not exactly the genre’s most beloved trope, but it’s certainly one that has ingrained itself into our collective pop culture consciousness over the years.

To be fair, though, the Zelda/Link love hasn’t just been in our heads this entire time. The popular theory is that the pair end up getting married at the end of the original NES game (even if the sourcing for that claim is somewhat dubious from a canonical perspective), and we see Zelda kiss Link at the end of Zelda II: The Adventure of Link. Granted, the Zelda that kisses him at the end of that game isn’t the Zelda he saved in the original game but rather a version of Zelda from years ago. Look, Zelda lore is…weird.

Speaking of which, we should probably talk about the Link from the 1989 animated Legend of Zelda TV series. That version of Link was more or less a stalker who pretty much refused to help Zelda without asking for a kiss. He was also so insufferably annoying that we honestly think Zelda might have been better off with Ganon than this ’80s movie jock in a green leotard.

It’s around that time that Nintendo became much coyer about Zelda and Link’s relationship. A Link to the Past doesn’t really bother to bring up the possibility of a romantic relationship between the two (outside of an often misinterpreted piece of dialog), and Link’s Awakening doesn’t even feature Zelda (though the character Marin is clearly inspired by Link’s memories of Zelda). At this point, it’s easy to assume that Nintendo decided to abandon the more overt references to Link and Zelda’s romance due to creative preferences, the increasingly complicated nature of the franchise’s timeline, and perhaps the feeling that this just wasn’t meant to be that kind of franchise.

That’s when we enter a prolonged and strange “Will they or won’t they?” period for Link and Zelda’s relationship. Ocarina of Time dances around the issue, but only hints that a romantic relationship may be blossoming. The Wind Waker pretty much abandons the idea entirely in favor of presenting the two as adventuring equals, while Twilight Princess offers the “coldest,” or perhaps most “business-like,” relationship between the pair yet. Nintendo even gave Link more overt love interests during this time to seemingly try to encourage people to stop focusing so much on the Zelda/Link romance narrative.

Interestingly, the Zelda/Link relationship has always skewed more towards intimacy (or at least blossoming romance) in many of the handheld Zelda games. That’s not a universal rule (Zelda wasn’t even in Phantom Hourglass), but for some reason, the pair have almost always been a bit…closer in those games.

That trend reached its apex with the release of 2009’s The Legend of Zelda: Spirit Tracks. That game was originally not even supposed to include Zelda as Link’s adventuring partner, but the developers felt like it would be better to feature her as a prominent side character rather than try to create a new character or simply re-use Wind Waker/Phantom Hourglass‘ Tetra yet again. The result is a Zelda game where Link and Zelda spend an unusual amount of time together (compared to other titles in this series). While that kind of set-up is enough to get shippers talking, the game wasn’t exactly shy about teasing a possible romance. It even ends with Zelda and Link holding hands!

What’s even more interesting than Spirit Tracks‘ implication that its version of Zelda and Link could end up together is the reason that the developers chose to give Link a female partner for that game in the first place.

“I was searching for something that hadn’t been portrayed much, and there was Princess Zelda,” says director Daiki Iwamoto regarding the casting decision. “At first, we hadn’t settled on the subcharacter, and I discussed several things with the staff. Then we thought that, since they’re adventuring together, it would be better to have it be a girl.”

That last part brings us back to the elephant in the room concerning this whole Zelda/Link relationship discussion. There is a heteronormative side to fantasy fiction from certain eras that has, to a degree, trained our brains to see female and male leads together and just assume that they’re going to be romantically involved by the time the credits roll.

Even though Nintendo has historically danced around this romance and, at times, straight-up avoided it, Iwamoto still says that it just made more sense for Link to be with a female character that he obviously ends up having intimate moments with (even if they may or may not be entirely romantic). You could argue that throughout much of the history of The Legend of Zelda franchise, speculation regarding the pair’s romantic relationship has been fuelled by those who either wished the two would get together or just assumed that has to be the case given their situation and genders.

So why did Nintendo decide to finally show Link and Zelda in an obviously romantic relationship in Skyward Sword after dodging the matter for so long? Interestingly enough, Skyward Sword producer Eiji Aonuma thought about cutting the romance angles when the game’s development team (which, it must be said, consisted of quite a few Spirit Tracks developers) initially suggested them. While Skyward Sword‘s developers had to make some cuts to justify including the romance subplot, Aonuma’s decision to leave it in ultimately came down to his simple belief that it was an effective way to get players to care about rescuing Zelda.

“As far as the love story goes, it wasn’t that we wanted to create a romance between Link and Zelda as much as we wanted the player to feel like this is a person who’s very important to me, who I need to find,” Aonuma said in an interview with Game Informer. “We used that hint of a romance between the two to tug at the heartstrings.”

From a meta standpoint, the idea that Nintendo is aware that even hinting at the possibility of a Link and Zelda romance is a pretty easy way to engage people certainly makes a lot of sense. While Aonuma stops short of saying that was somehow their idea this entire time, you could argue that it’s more valuable for Nintendo to simply leave room open for that possibility rather than outright establish a romantic relationship more often.

Of course, that makes it all the more interesting that the one Zelda game that features such a blatant romance story is also the first game in the Zelda timeline. While the versions of Link and Zelda featured in that game are not the same characters we see in subsequent games, Nintendo did clearly establish that the foundation of their relationship (and this franchise) is partially based on their love for each other. Circumstances may have prevented them from leading the life together they hoped to have (at least based on our hopes for how two young people in love might end up), but who is to say that one of Zelda‘s descendants or one of Link’s reincarnations won’t be able to break the curse and live the life that these two were possibly denied so many years ago?

Actually, that’s what makes Breath of the Wild such a fascinating piece of this puzzle. While serious questions remain regarding how Breath of the Wild fits into Zelda‘s chronology, it almost certainly seems to take place at what we could see as “the end” of the current Zelda timeline (or timelines). It’s perhaps no coincidence, then, that it’s the game that not only openly acknowledges the complicated relationship between the various Links and Zeldas over the years but is also the game that shows Link and Zelda clearly growing closer to each other over the course of the adventure. By the end of the game, you could very easily view their relationship as “romantic” or, at the very least, heading in that direction.

While we’ll have to see whether or not Breath of the Wild 2 does anything with that implication, we’re left with the simple conclusion that Skyward Sword may be the only “overt” Link and Zelda romance story so far, but elements of that romance can be found in Spirit Tracks, Breath of the Wild, and, depending on your interpretation of the timeline, nearly every other Legend of Zelda game in some form or fashion.

Sure, it’s a little annoying that Nintendo keeps hinting at romances they seemingly never intend to really do anything with, but there’s something to be said for the ways they’ve paired Zelda and Link together over the years without relying on a relatively simple romantic subplot. Of course, that just makes Skyward Sword even more of an oddity than it already was.

The post Is Skyward Sword the Only Link and Zelda Romance Story? appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/3emV71c

0 notes

Text

You know I’m really less than thrilled about a story when even the father-daughter hook isn’t enough to get me to fully invest in its entirety. And that’s how it is for me with Legend of Korra, the sequel series to Avatar: the Last Airbender.

And a shame too, because on top of father-daughter relationships in stories, I love sequel series and spin-offs. Or, I guess I should say, I do love the idea of them. The ones that I’ve had actual experience with are hit-or-miss and, like with anything, are only a hit for me based on how meretriciously they stand on their own as stories. To the point where I haven’t even gotten my first book published, the first book of the YA series I have planned, and already I have plot points and characters in mind for the next-gen sequel series. Kind of like imagining my grandchildren when I haven’t even had children of my own yet.

Avatar: the Last Airbender was yet another great series that I was one of the last ones to board the hype train for (at least of my generation I’m sure), for many reasons. Not because I didn’t appreciate it, because I love anything to do with working with the four elements (considering that’s what my own YA debut series is centered on), and never mind that it was only anime-esque, because that was still good enough for me.

But I missed out on watching it in full when it aired. I was in high school back then and just didn’t make time for it. When I did get around to watching it, through to the end of season one, I was so depressed by a plot point I was spoiled on (that being that Sokka was going to lose his first love, Princess Yue) that I stepped away from it. And that was back when I was brave enough to stream off illegal streaming sites on my laptop. Then I got wary of that practice, (barring resorting to find shows I can’t find anywhere else on those sites via my phone instead) and moved on to other things, anime, etc. With the passing of time, I knew that if I was going to fall hard for Avatar in the end, I wanted to do it on a legal streaming platform that I could watching on my laptop, not my phone. And, if I loved it enough, purchase a hardcopy of it.

If this was available all along, to this day, on Nick.com for free, then someone feel free to let me know. But, as far as I was concerned, I didn’t see my window of opportunity to binge it until Netflix brought it onboard their streaming platform this past summer. Yes, the series was also available for purchase through YouTube and of course there were the available hardcopies, but I was still hesitant to make that purchase until I had seen the show in full. Sometimes I take a risk on shows and buy them without seeing them first, and I hit a jackpot (like with the anime, Psycho-Pass), and sometimes I take that risk and regret my purchase (like with the anime film, Fireworks). In this case, even though I could smack myself in the head in hindsight, I decided to not take the risk until I was 100% sure, watch-through included.

So, stuck inside like we all are right now, I told myself, “No more excuses, you are finishing this thing.” Next thing you know, I’ve bought myself the full series on blu-ray (having been reassured that I loved the thing as much as the world promised I would) and I’ve rewatched it twice now. I freaking love it. And predictably with that love came the price of the “void”: that depressing post-watch feeling when it seems as though nothing will ever be as good again as what you just finished watching. When all you want is more, since you know you can’t ever actually reexperience the feeling of watching it for the first time.

Which brings me to Legend of Korra, which I had also heard about. And heard that it had issues writing-wise, and didn’t quite live up to the legacy of Avatar. And well, to be fair, expecting it to would have been a bit naïve. Rarely do most things in this world get their version of Rocky and Rocky II winning Best Picture at the Oscars back-to-back years.

I thought about watching it, going back and forth since before I had even finished the original series. I was happy to see that we were getting a female main as the new Avatar in the cycle, and, again, there’s that thing I love about sequel series, revisiting old characters marked by the progression of time, as well as seeing new characters, both the next gens of the original cast and new originals alike. I love seeing them rise and carry the torch that’s been passed onto them.

And in this case, we not only get a female Avatar, Korra, but she’s paired with character growth in part with her father, so there’s that father-daughter trope box ticked. Actually, we get two, with Aang’s son Tenzin, and his daughter, Aang’s granddaughter, Jinora.

Yet, I was also given to understand that the romance subplots were a complete mess, and then the overarching storylines in general were also somewhat botched in places. I mean, they name Korra’s first main love interest Mako (in honor of Mako, the actor who originally voiced best-uncle-in-the-universe Iroh in the originals series), and yet, writing-wise and romance-wise, he kind of gets the shaft from what I’ve seen. That aside, I wouldn’t have had a problem with the Korra x Asami ship itself, if it weren’t for how the writers got them together. That being not only via the worst kind of love-triangle nonsense from what I’ve been given to understand, but one that involves cheating on one person for the other because, “Oh, we have something more.” No excuses for cheating in my book.

All of this due, in no small part I’m sure, to Nickelodeon mucking things up (like you do) in hedging on allowing any of the show to be made, and then on whether there’d be more seasons, and with the writers, all the while, having to work with that uncertainty. One could argue that the best writers find ways to work around that to the point that those problems don’t show in the writing of the final product, but if there was all that grief, I give the writers some slack. Just the same, it was also enough to put me off watching the show.

And it still is enough. Barring everything else watchable in the universe disappearing and this being the only thing left, I, at this point, do not see myself ever watching it in full. At this point, I’ve watched a few clips and bits of episodes in the first three seasons, because I was still curious about certain things and I love free samples. But those things in connection with the rest of the story isn’t enough even now to get me to invest my time in watching the whole thing through when the series joins Avatar: the Last Airbender on Netflix.

However, I did in fact get something out of watching those disparate few clips and bits. And not just evidence for the case that Aang and Katara’s son Bumi clearly takes after both his Uncle Sokka as well as his own namesake, the “mad genius” King Bumi, or Zuko having a grandson named Iroh (and the fact that they had him voiced by Dante Bosco, who voiced Zuko in Last Airbender), or even the fact that now-old-guy Zuko himself is riding a bleeping dragon.

I got perhaps the most powerful and emotionally engaging origin story for a fantasy world that I can ever recall getting in any type of media. That being the story of Wan, the First Avatar, as told in episodes seven and eight in season two, Beginnings: Pt. 1 & 2.

I loved these two episodes so much that I keep playing the reworked Avatar theme, The Avatar State, from the Korra soundtrack, on repeat. And can’t get enough of rewatching the moment when Wan becomes the first fully realized Avatar. Barring the stuff with the present-day storyline of the show bookending the beginning of part one and the conclusion of part two, there’s a complete, and rather satisfying story here, made doubly enjoyable by anyone familiar with at least Avatar: the Last Airbender.

I didn’t need to (personally) watch the episodes prior to these two parts to understand anything that was going on or appreciate it any more than I already did, or what I’d already floating around about Raava, the Spirit of Good and Light and Peace and Sunshine and Rainbows, serving ultimately in part as the means to create the phenomenon of the Avatar and the Avatar Reincarnation Cycle. The change in art style to something reminiscent of the works of Hokusai’s woodblock paintings was beautiful, and Wan’s characterization was beautiful, from diamond-in-the-rough street rat just trying to get by to developing such a relationship with the spirits that he lays the foundation for becoming “the bridge between the human and the spirit worlds” that the Avatar is meant to represent.

A journey of a simple human who screwed up, and atoned for that through bitter work and forming a meaningful bond that would come to transcend millennia, all for the sake of trying to keep the world in balance, striving to better humanity. And from that, the lives that are relived through that of the Avatar echo meaningfully from the distant past to the reflective present.

And it only took two episodes. With concise writing, emotionality, and characterization, we got what fell like an entire epic story in just a matter of less than an hour or so of screen time. I watched them both on my phone, and when Korra comes onto Netflix, I’ll revisit those two alone on there and be more than satisfied.

All that said, there is a very good argument against being able to enjoy it as its own thing, never mind its flaws in terms of consistency with the established world of Last Airbender. Which I totally understand, and would probably understand more if I took the time to watch Korra in its entirety, and even in regards to the fact that I’ve seen Avatar: the Last Airbender. In which case, I could see how these two episodes actually undermine and even outright retcon a ton of story and world elements.

That said, I personally don’t agree that it ruins the spirituality inherent and or implied by the relationship between humans and the art of elemental bending. If only because after all that, I still felt a catharsis at the conclusion of Wan’s story. I’d call that doing something right with the writing at least.

What I think I works for me in particular compared to Korra as a whole, apart from my affinity for guys with flooffy anime hair who go on penance journeys toward enlightenment, is that it feels like a return to its roots, to that feeling that the original Avatar series gave me, and also something more. Not to say that I think that Korra should have been a retread of the plot structure of Last Airbender by any stretch, that would have made it worse, and I applaud it for pushing towards different themes and conflicts from that of its predecessor (it’s just that the payoff for a lot of those were less-than-stellar). That said, the moments that I came across that were awesome and moving were patchworked together by plots that didn’t always come out the most coherently or compellingly when laid out in the light of day.

And yes there is the argument that Wan’s story lacks anything compelling. I suppose, because you know how it’s going to play out, and it derails from the main plot, somewhat, save for explaining the whole Raava vs. Vaatu, good vs. evil spirit conflict. But, again, for me, I’m watching these more completely than I have any other episode of the show, and as a separate spinoff from the rest of the series. So while technically it can’t be a self-contained story, as the series it is a part of would undo that possibility, I still enjoyed it regardless for what it is on its own, and genuinely at that.

I enjoyed that it was something of a mix of a fable and an actual historical account, adding to that sense of expanding the mythos in that way that distant histories like that of ancient civilizations in our world have become fuzzy and fragmented with the passage of time. I enjoyed how simply it was able to establish a young man who started out as a ruffian who had to steal to survive, but was still fundamentally good in that he cared for those close to him, and that he had the capacity to care for the well-being of spirits after he’d been banished for stealing the power of firebending and was banished to live in the spirit wilds.

Then take that, and develop him into a man who rises above that, to become one who takes on the burden of fighting for peace, especially in the wake of mistakes he’s made that caused things between humans and spirits to grow worse, regardless of whether or not he intended such. To see him grow through his friendship with Raava, and how they come to work together to restore the balance he inadvertently put out of whack when he was tricked into separating her from her eternal struggle with Vaatu, Spirit of Darkness and Chaos and Corruption and All the World’s Evil. Concluded with that final culmination between him and Raava fusing together permanently, mastering all four elements, getting knocked down by Vaatu over and over and still getting up and standing to fight again every time, his efforts to bring peace to the world foiled only by his short human lifespan, and with his death beginning the Avatar reincarnation cycle when its clear that maintaining balance in a world full of humans takes thousands upon thousands of lifetimes.

To me, that was a beautiful simplicity for an origin story told within the larger story of a larger world. Which I think is a great tool for anyone who looks to insert those sorts of things in their own writing (including myself, who has her own origin storyline in mind for that YA elemental series, if I didn’t already mention before that I’m writing that).

Retcons and undermining aside, I’m happy that I discovered this little gem within the great world of The Last Airbender, and like all things in media that affect me this way, you can be sure I’ll carry that feeling further into my work. Threading it through into the grander tapestry of the art of storytelling.

Right. Back to me waiting for season four of The Dragon Prince.

Keeping this link up to their donation page!

A Concise, Emotional Origin Journey You know I'm really less than thrilled about a story when even the father-daughter hook isn't enough to get me to fully invest in its entirety.

#avatar#avatar the last airbender#dragon prince#fireworks#hokusai#netflix#nickelodeon#origin story#oscars#psycho-pass#rocky#rocky ii#sequels#the dragon prince#the legend of korra#YA#YA fiction#young adult

0 notes

Text

For All Its Whimsy, ‘Crazy Delicious’ Can’t Escape Reality

Channel 4/Netflix

A fantastical setting and famous “Food Gods” Carla Hall and Heston Blumenthal only underline how conventional this Netflix effort is

Strawberry cheesecake chicken wings. Prosecco waterfalls and cheese growing on trees. Chef Heston Blumenthal descending in a thunderclap, wearing a tight white suit. It’s not a lucid dream diary: it’s the newest cooking show on Netflix, Crazy Delicious, wherein three contestants compete in three rounds, taking ingredients and inspiration from a Willy Wonka-like garden where nearly everything is edible. The first round is based on a hero ingredient like a strawberry or tomato, the second is a reinvention of a classic, and the third is a showstopper, with inspiration ranging from brunch to barbecue.

No mere panel of mortals will judge such a show. Enter the “Food Gods” — made up of Blumenthal, Top Chef legend Carla Hall, and “Michelin-starred chef” Niklas Ekstedt. Dressed in their pristine white costumes and accompanied by ominous music, the trio might be set up as transcendent, but their actual job is that of the classic food show judge: offer some opinions, throw some concerned looks, and dish out zingy one-liners. (When a contestant tells Hall, that their dish is made with love, Hall replies, “Well, [love] doesn’t have salt, unless you’re crying, honey.”) Host Jayde Adams, meanwhile, adds a decidedly dry British slant to the show’s proceedings, despite the show trying to turn her into a Lewis Carroll character.

While Crazy Delicious aims to break the food show mold — creating something more zany than Chopped and Masterchef, more bonkers than Nailed It, and cuter than The Great British Baking Off — it falls short on everything but the set. What unfolds in the short season is six episodes torn between total culinary fantasia and convention, the result of which is a basic cooking competition, but with more crafting supplies for sets and costumes. Its best efforts to bring something new to food TV only reveal just how conventional Crazy Delicious actually is.

Food TV shows, crazy or delicious, pivot on power dynamics: the relationship between the judges and the judged, mediated and molded by the hosts. While in recent years, shows like Great British Baking Off and Australian hit The Chefs’ Line have extricated themselves from boorish villain/hero tropes, Crazy Delicious wants to go as far as to extricate its judges from earth itself. They are Food Gods: remember this and do not forget it — but in case you do, production is here to remind you with thunder, lightning, and, well, that’s all.

The Food Gods, though, are also actual people with restaurant chops. While their duties rarely go beyond encouraging praise or gentle criticism, the show asks them to show off their conventional culinary credentials, rather than representing anything transcendent or wacky. Ekstedt references Michelin stars as a point of comparison when praising dishes; Hall harks back to her time as a contestant on Top Chef. When Heston Blumenthal becomes a Food God in his Edenic realm, he’s still being leaned on as a famous chef — the famous chef subject to widely reported accusations of wage theft and restaurant mismanagement, and a late-career pivot to casual sexism. The choice of name also unfortunately recalls Time Magazine’s infamous “Gods of Food” feature, whose anointing chefs as figures of worship excluded women entirely. There is no need for them to be culinary gods other than to be culinary Gods — deified shibboleths, set apart from the mortal contestants who try to please them by walking up a slightly steep hill godly mountain with their possibly crazy, possibly delicious food.

The contestants don’t quite get to realize the fantasy either. The diversity in every episode is a welcome development, and it’s interesting that contestants are neither the rank amateurs of Masterchef nor the trained chefs of Chopped. These are keen, often technically proficient cooks, and there is quality technique and great skill on display, so it’s a shame that they’re dealt kind of a raw deal. The stakes too often feel too low, and with each 45 minute episode being a self-contained story, there’s little time to develop intrigue or connections to the people on screen. The prize for winning is a golden apple, which means when crackers break and parfaits don’t set, it’s pride and self-worth that are at stake, not money or prestige. While this makes for more genuine emotion, it also puts limits on the show’s range. With neither financial reward nor — as with Great British Bake Off — the promise of access into the world of culinary celebrity, Crazy Delicious has to stand or fall between the start of each episode and its end. It falls more than it stands..

The prize golden apple is picked from the phantasmagoria of the Willy Wonka set — the most striking departure from the “faintly cool, faintly dangerous kitchen” template of its competitors; exceptions made for the GBBO tent. It could have been the ace in the hole: Everything is edible, and the contestants are instructed not just to find cheese in nooks and eggs in nests, but to “go forth and forage,” plucking tomatoes from vines and digging carrots from the earth, engaging with the agricultural systems that produce food.

Well, not quite. This bounty is artificial, because of course it is, and other ingredients like chopped meat and packets of pasta are not delved from grottos, but removed from fridges and pantries. This happens in any show with an ingredients tray, which is almost all cooking shows, but they don’t try to pretend otherwise. The creation of a fake, bountiful food system that is not entirely fictional but is entirely alienated from labor feels incongruous to the admirable, if unfulfilled ambition of other food TV in 2020 to reflect on the fact that everybody eats. Asking something as fanciful as Crazy Delicious to bear the weight of expectation around Taste the Nation or near-namesake Ugly Delicious might appear unkind, but the show wants it two ways — a magical respite from typical food TV, but with all the same prestige trappings — and ends up in some confused middle ground.

The genuinely fun elements of Crazy Delicious, like candles that burst smilingly with mango pulp or edible cherry blossoms that are sweets, unfortunately become little more than gags; the contestants never engage with them or use them in their cooking. Even Chopped, set in a kitchen and not an edible eden, does more with its introduction of comparatively conventional curveball ingredients. The Crazy Delicious set’s unchanging nature also means that the show runs out of secrets early on. A prosecco waterfall might bubble with whimsy in episode one, but it’ll go flat by episode three. There are some interstitial incursions which are funny albeit a little outdated, like a momentary send-up of the errant coffee cup in Game of Thrones, but as with the rest of the show’s elements, these jokes only further confuse the tone. Indeed, the omnipresent Big Green Egg — the favorite barbecue of chefs, sponconned across the industry — is significantly more disconcerting.

Overall, the place that Crazy Delicious is asking viewers to escape from — the world of food TV — looms so large that the show ends up reiterating familiar tropes rather than subverting them as intended. A set with ovens and blenders and barbecues surrounded by foliage is still a set with ovens and blenders and barbecues. Eurocentric restaurant discourse, standards, and techniques are so present that any fantasy never gets to genuinely establish itself; the final four-hour challenge of the series is “takeaway,” and of course, it pigeonholes Indian cuisine. Ultimately Crazy Delicious is frustrating: it could have been deeply weird, deeply fantastical; it could have been a jolly romp, contestants competing to grab the fruit candles and chocolate tree branches, the chaos of Supermarket Sweep unmanacled from the supermarket. Instead, even with its sweet burgers and activated charcoal pizza volcanoes, it feels like a waste.

It would be seemingly easy to write all these annoyances off because Crazy Delicious is, quite clearly, trying to be a bit of harmless fun. Viewers seeking a six-episode bliss-out with a few laughs and some Willy Wonka flourishes are just in it for the escapism, not the optics, right? But the titular crazy is leaning too much on the delicious, and the delicious is just normie interpretations of “good” food. Despite the ongoing insistence on the show’s wackiness, the results are a less fun, less weird, less intelligent, less crazy, and less delicious follow up to Chopped, GBBO, The Chef’s Line, and Nailed It. Try as it might, Crazy Delicious cannot unmoor itself from the fact that unlike its edible punchlines, food, and restaurants don’t just grow on trees.

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/2AiHpLL https://ift.tt/2AlE3ru

Channel 4/Netflix

A fantastical setting and famous “Food Gods” Carla Hall and Heston Blumenthal only underline how conventional this Netflix effort is

Strawberry cheesecake chicken wings. Prosecco waterfalls and cheese growing on trees. Chef Heston Blumenthal descending in a thunderclap, wearing a tight white suit. It’s not a lucid dream diary: it’s the newest cooking show on Netflix, Crazy Delicious, wherein three contestants compete in three rounds, taking ingredients and inspiration from a Willy Wonka-like garden where nearly everything is edible. The first round is based on a hero ingredient like a strawberry or tomato, the second is a reinvention of a classic, and the third is a showstopper, with inspiration ranging from brunch to barbecue.

No mere panel of mortals will judge such a show. Enter the “Food Gods” — made up of Blumenthal, Top Chef legend Carla Hall, and “Michelin-starred chef” Niklas Ekstedt. Dressed in their pristine white costumes and accompanied by ominous music, the trio might be set up as transcendent, but their actual job is that of the classic food show judge: offer some opinions, throw some concerned looks, and dish out zingy one-liners. (When a contestant tells Hall, that their dish is made with love, Hall replies, “Well, [love] doesn’t have salt, unless you’re crying, honey.”) Host Jayde Adams, meanwhile, adds a decidedly dry British slant to the show’s proceedings, despite the show trying to turn her into a Lewis Carroll character.

While Crazy Delicious aims to break the food show mold — creating something more zany than Chopped and Masterchef, more bonkers than Nailed It, and cuter than The Great British Baking Off — it falls short on everything but the set. What unfolds in the short season is six episodes torn between total culinary fantasia and convention, the result of which is a basic cooking competition, but with more crafting supplies for sets and costumes. Its best efforts to bring something new to food TV only reveal just how conventional Crazy Delicious actually is.

Food TV shows, crazy or delicious, pivot on power dynamics: the relationship between the judges and the judged, mediated and molded by the hosts. While in recent years, shows like Great British Baking Off and Australian hit The Chefs’ Line have extricated themselves from boorish villain/hero tropes, Crazy Delicious wants to go as far as to extricate its judges from earth itself. They are Food Gods: remember this and do not forget it — but in case you do, production is here to remind you with thunder, lightning, and, well, that’s all.

The Food Gods, though, are also actual people with restaurant chops. While their duties rarely go beyond encouraging praise or gentle criticism, the show asks them to show off their conventional culinary credentials, rather than representing anything transcendent or wacky. Ekstedt references Michelin stars as a point of comparison when praising dishes; Hall harks back to her time as a contestant on Top Chef. When Heston Blumenthal becomes a Food God in his Edenic realm, he’s still being leaned on as a famous chef — the famous chef subject to widely reported accusations of wage theft and restaurant mismanagement, and a late-career pivot to casual sexism. The choice of name also unfortunately recalls Time Magazine’s infamous “Gods of Food” feature, whose anointing chefs as figures of worship excluded women entirely. There is no need for them to be culinary gods other than to be culinary Gods — deified shibboleths, set apart from the mortal contestants who try to please them by walking up a slightly steep hill godly mountain with their possibly crazy, possibly delicious food.

The contestants don’t quite get to realize the fantasy either. The diversity in every episode is a welcome development, and it’s interesting that contestants are neither the rank amateurs of Masterchef nor the trained chefs of Chopped. These are keen, often technically proficient cooks, and there is quality technique and great skill on display, so it’s a shame that they’re dealt kind of a raw deal. The stakes too often feel too low, and with each 45 minute episode being a self-contained story, there’s little time to develop intrigue or connections to the people on screen. The prize for winning is a golden apple, which means when crackers break and parfaits don’t set, it’s pride and self-worth that are at stake, not money or prestige. While this makes for more genuine emotion, it also puts limits on the show’s range. With neither financial reward nor — as with Great British Bake Off — the promise of access into the world of culinary celebrity, Crazy Delicious has to stand or fall between the start of each episode and its end. It falls more than it stands..

The prize golden apple is picked from the phantasmagoria of the Willy Wonka set — the most striking departure from the “faintly cool, faintly dangerous kitchen” template of its competitors; exceptions made for the GBBO tent. It could have been the ace in the hole: Everything is edible, and the contestants are instructed not just to find cheese in nooks and eggs in nests, but to “go forth and forage,” plucking tomatoes from vines and digging carrots from the earth, engaging with the agricultural systems that produce food.

Well, not quite. This bounty is artificial, because of course it is, and other ingredients like chopped meat and packets of pasta are not delved from grottos, but removed from fridges and pantries. This happens in any show with an ingredients tray, which is almost all cooking shows, but they don’t try to pretend otherwise. The creation of a fake, bountiful food system that is not entirely fictional but is entirely alienated from labor feels incongruous to the admirable, if unfulfilled ambition of other food TV in 2020 to reflect on the fact that everybody eats. Asking something as fanciful as Crazy Delicious to bear the weight of expectation around Taste the Nation or near-namesake Ugly Delicious might appear unkind, but the show wants it two ways — a magical respite from typical food TV, but with all the same prestige trappings — and ends up in some confused middle ground.

The genuinely fun elements of Crazy Delicious, like candles that burst smilingly with mango pulp or edible cherry blossoms that are sweets, unfortunately become little more than gags; the contestants never engage with them or use them in their cooking. Even Chopped, set in a kitchen and not an edible eden, does more with its introduction of comparatively conventional curveball ingredients. The Crazy Delicious set’s unchanging nature also means that the show runs out of secrets early on. A prosecco waterfall might bubble with whimsy in episode one, but it’ll go flat by episode three. There are some interstitial incursions which are funny albeit a little outdated, like a momentary send-up of the errant coffee cup in Game of Thrones, but as with the rest of the show’s elements, these jokes only further confuse the tone. Indeed, the omnipresent Big Green Egg — the favorite barbecue of chefs, sponconned across the industry — is significantly more disconcerting.

Overall, the place that Crazy Delicious is asking viewers to escape from — the world of food TV — looms so large that the show ends up reiterating familiar tropes rather than subverting them as intended. A set with ovens and blenders and barbecues surrounded by foliage is still a set with ovens and blenders and barbecues. Eurocentric restaurant discourse, standards, and techniques are so present that any fantasy never gets to genuinely establish itself; the final four-hour challenge of the series is “takeaway,” and of course, it pigeonholes Indian cuisine. Ultimately Crazy Delicious is frustrating: it could have been deeply weird, deeply fantastical; it could have been a jolly romp, contestants competing to grab the fruit candles and chocolate tree branches, the chaos of Supermarket Sweep unmanacled from the supermarket. Instead, even with its sweet burgers and activated charcoal pizza volcanoes, it feels like a waste.

It would be seemingly easy to write all these annoyances off because Crazy Delicious is, quite clearly, trying to be a bit of harmless fun. Viewers seeking a six-episode bliss-out with a few laughs and some Willy Wonka flourishes are just in it for the escapism, not the optics, right? But the titular crazy is leaning too much on the delicious, and the delicious is just normie interpretations of “good” food. Despite the ongoing insistence on the show’s wackiness, the results are a less fun, less weird, less intelligent, less crazy, and less delicious follow up to Chopped, GBBO, The Chef’s Line, and Nailed It. Try as it might, Crazy Delicious cannot unmoor itself from the fact that unlike its edible punchlines, food, and restaurants don’t just grow on trees.

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/2AiHpLL via Blogger https://ift.tt/38h1T4j

0 notes

Text

My Top 5 Video Game Intros

Since I haven't posted in a while and since I don't have any ideas for full-fledged reviews, let's do something different today and talk about my 5 favorite intros to video games I enjoyed in the past. Please note that this is a very personal, opinionated list; I have somewhat deliberately avoided really obvious picks (consider Metal Gear Solid 3's and Final Fantasy VI's openings, among others, to be hovering around in spirit somewhere around here). Furthermore, I'm not limiting myself exclusively to that very first, usually pre-rendered opening scene of a game (like, the attract mode before you even press start), because most of the time those are kind of devoid of any meaning and without context, I'd just be judging them by coolness or whatever, which isn't very interesting or inducive to commentary. Anyway, without further ado, here are my top 5 video game intros:

#5: Wild Arms 3's evolving opening https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SvoueEiVyWE