#junta of chile

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Bloody pink, sensual red... Which one?

#enstars#ensemble stars#my art#draws#hiyori tomoe#tomoe hiyori#jun sazanami#sazanami jun#enstars eve#my honest reaction when i keep using bright colors and then i have to put them through cmyk mode#i might have cried a little#but anyways im posting the bright version here#dudo que alguien lea esto pero hi... si hay enstarries de chile pienso llevarlo a la junta de feb !#power couple btw

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Testimonio de Daniel Tarnopolsky / 21 de julio 2014

🇦🇷 Daniel Tarnopolsky es un defensor de los derechos humanos cuyo testimonio refleja la brutalidad de la dictadura militar en Argentina (1976-1983). El 15 de julio de 1976, sus padres, Hugo Tarnopolsky y Blanca Edelberg, su hermano Sergio, su cuñada Laura Inés del Duca y su hermana Betina fueron secuestrados por las fuerzas de la dictadura y vistos en la Escuela de Mecánica de la Armada (ESMA), centro clandestino de detención, sin que se sepa su destino hasta la fecha. Daniel se exilió, primero en Chile, luego en Israel y Francia, donde en 1978 fundó el Comité de Familiares de Desaparecidos (COSOFAM) para luchar por la memoria y justicia de las víctimas. Regresó a Argentina en 1984 y ha sido clave en juicios históricos como el Juicio a las Juntas. En 1987 inició una demanda contra el Estado argentino y Emilio Massera, donando su indemnización en 2004 a las Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo. Actualmente, Daniel forma parte del Ente Público Espacio para la Memoria y sigue siendo un referente en la defensa de los derechos humanos.

youtube

🇺🇸 Daniel Tarnopolsky is a human rights advocate whose testimony reflects the brutality of Argentina's military dictatorship (1976-1983). On July 15, 1976, his parents, Hugo Tarnopolsky and Blanca Edelberg, his brother Sergio, his sister-in-law Laura Inés del Duca, and his younger sister Betina were kidnapped by the dictatorship’s forces and seen at the Navy Mechanics School (ESMA), a clandestine detention center, but remain disappeared to this day. Daniel went into exile, first in Chile, then Israel, and France, where in 1978 he co-founded the Committee of Families of the Disappeared (COSOFAM) to fight for justice. He returned to Argentina in 1984 and played a key role in historic trials such as the Trial of the Juntas. In 1987, he sued the Argentine State and Emilio Massera, donating his compensation in 2004 to the Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo. Today, Daniel serves on the Public Space for Memory Board and continues to be a leading figure in defending human rights.

#Daniel Tarnopolsky#Hugo Tarnopolsky#Blanca Edelberg#15 de julio de 1976#Juventud Peronista#JP#servicio militar#la Escuela de Mecánica de la Armada#ESMA#Laura Inés del Duca#Betina Tarnopolsky#la Unión de Estudiantes Secundarios#UES#desaparecidos#los desaparecidos#Chile#Israel#Francia#Comité de Familiares de Desaparecidos#COSOFAM#Argentina#Juicio a las Juntas#Emilio Eduardo Massera#Rosa Daneman de Edelberg#Betina sin aparecer#Ente Público Espacio para la Memoria#Promoción y Defensa de los Derechos Humanos#judaísmo#judaism#jumblr

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's Castiel's birthday but also Chile's birthday and nobody is talking about it, how sad 😔🇨🇱

[Spanish/Español]: Es el cumple de Castiel pero también el de Chile y nadie habla de eso, qué triste 😔🇨🇱

#supernatural#spn#castiel#chile#independence day#18 de septiembre#tumblr chilenito#tumblr chilensis#chile tumblr#en realidad estamos celebrando la primera junta de gobierno porque la verdadera independencia es el 12 de febrero pero son detalles#dia de la independencia

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wall Tappings: An International Anthology of Women's Prison Writings, 200 to the Present Judith A. Scheffler Feminist Press at CUNY, 2002

The Junta guards had no respect for the women political prisoners of Tres Alamos. Because they were mostly young women without leadership experience, the guards did not take their militant politics seriously. They sneeringly referred to the prison cell full of young women as "the harem". At Tres Alamos revolutionary women emerged from the prison showers to find all their plain clothing and underwear was stolen, and their only offering was a pile of skimpy lingerie. Done supposedly in the name of security so nothing could be hidden in those flimsy garments. Being so underdressed all the time was almost worse than being undressed. It gave the illusion of some covering, but no protection when guards would run their hands over their bodies. The guards euphemistically referred to their rapes as "pleasure sessions". Women would have to spend the entire night in bed with a guard under the misogynist belief that women can't revolt against men they are sleeping with. Armed with machismo, guards did not believe women they had repeated sexual intercourse with could still resist them.

Under these excruciating conditions of sexual humiliation, in which the full power of the Junta Fascist state was used to make militant women forget they were revolutionaries, they did not forget. They answered the class hatred of the guards with their own proletarian class hatred. They continued their Marxist workshops and study groups. Women in nothing but bras and tangas organized Party meetings and discussed strategies of resistance. In lingerie they discussed the intricacies of dialectical materialism.

Amazingly under these privations, they even created a prison Party cell wall newspaper. They did not forget the teachings of Lenin, that the newspaper is the organizing principle of the Party. And even in a prison that the guards had turned into a lingerie harem, disciplined compañeras put out a prison newspaper. The Junta severely estimated the strength of young women, who they thought would be easily tamed from tigresses into submissive kittens. Their militant defiant spirit and disciplined organization lived on under the most degrading of circumstances. "Dignity in the face of the enemy".

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

La vida y legado de Bernardo O'Higgins Riquelme en la historia de Chile

View On WordPress

#Bernardo O&039;Higgins Riquelme#consolidación de la nación#Director Supremo#Ejército Libertador de los Andes#figura histórica#historia de Chile#independencia de Chile#independentismo#Junta de Gobierno#legado histórico#Reconquista#reformas políticas#rivalidades independentistas

0 notes

Text

Nunca van a poder negar lo chileno de Pedro Pascal. Vino a ver la familia y de paso compró terreno sacándose la cresta, clásico.

🤣

“Me sacaron la cresta”

Kjsjsjsajajja BASTA LO AMO DEMASIADO

#pedro pascal#chile#chilean spanish#actors#tipico chileno#que en juntas familiares alguien se saca la cresta

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Israel’s role in Pinochet’s brutality is still clouded in some mystery since Israel refuses to release a full accounting of its role, but enough documents have been released to reveal a sordid relationship between Israel and the Chilean junta. Israel did not just train Chilean personnel to aid the repression of its own people. After a US arms embargo against Chile passed the US Congress in 1976, a cable from the US Embassy in Chile on April 24, 1980, acknowledged that Israel was a major arms supplier to Pinochet. Another US cable, on April 10, 1984, quoted the American undersecretary of state as saying that Israel was still one of the main weapons suppliers to the regime. This steady stream of defense equipment undercut any potential benefits of the US arms embargo because Israel was not part of the deal.

Antony Loewenstein, The Palestine Laboratory: How Israel Exports the Technology of Occupation Around the World

374 notes

·

View notes

Text

The bastard was friends with the Argentinian junta, he was hanging around Videla, the Argentinian equivalent of Chile's Pinochet, and you bitches are woobifying him? THE HEAD OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH NONETHELESS? The stupidity is terminal, I fear.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘I’m Still Here’ Review: Walter Salles Returns Home With the Powerful Story of a Broken Family’s Resistance

Premiering at Venice, the film stars Fernanda Torres as a mother of five children who reinvents herself as a lawyer and activist after suffering a devastating loss at the height of Brazil’s military dictatorship.

BY DAVID ROONEY SEPTEMBER 1, 2024 @ 11:48AM

Fernanda Torres in 'I'm Still Here.' COURTESY OF VENICE FILM FESTIVAL

Walter Salles’ 1998 international breakthrough, Central Station, earned an Oscar nomination for the magnificent Fernanda Montenegro. Now in her 90s, the actress turns up toward the end of the director’s first feature in his native Brazil in 16 years, the shattering I’m Still Here(Ainda Estou Aqui), in a role that requires her to speak only through her expressive eyes. What makes the connection even more poignant is that she appears as the elderly, infirm version of the protagonist — a woman of quiet strength and resistance played by Montenegro’s daughter, Fernanda Torres, with extraordinary grace and dignity in the face of emotional suffering.

Many powerful films have been made about the 21 years of military dictatorship in Brazil, from 1964 through 1985, just as they have about similar oppressive regimes in neighboring South American countries like Chile, Argentina and Uruguay. The human rights abuses of systematic torture, murder and forced disappearances represent an open wound on the psyches of those nations, for which cinema has often served as a vessel for collective memory.

It’s not often, however, that the spirit of protest against the horrors of junta rule is viewed through such an intimate lens as I’m Still Here. That aspect is deepened by evidence throughout the film of Salles’ personal investment in the true story of the Paiva family after patriarch Rubens (Selton Mello), a former congressman, was taken from his Rio de Janeiro house in 1971, ostensibly to give a deposition, and never seen or heard from again.

Salles met the family in the late 1960s and spent a significant part of his youth in their home, which he credits as foundational to his cultural and political development. That accounts for the coursing vitality of the early scenes, as the five Paiva siblings dash back and forth between the house and the beach, and an extended family of friends of all ages seems to be constantly dropping by for drinks and meals and music and lively conversation.

There are sweet throwaway moments like two of the sisters dancing and singing along to the Serge Gainsbourg-Jane Birkin wispy make-out classic “Je t’aime … moi non plus,” without understanding the words. Just watching how one of the youngest kids, Marcelo (Guilherme Silveira), sweet-talks his way into keeping a stray dog they found on the beach conveys the warmth, spontaneity and affectionate scrappiness of the Paiva household dynamic. The young actors playing the kids are all disarmingly natural and appealing.

The first blunt intrusion into the family’s bubble of closeness and comfort comes when eldest daughter Vera (Valentina Herszage) is out with a group of friends and their car is pulled over at a tunnel roadblock. It’s a disturbing scene in which we see teenagers — just minutes earlier cruising along, sharing a joint and laughing — ordered at gunpoint to stand against a wall while military officers question them, searching their faces for any resemblance to the “terrorist killers” they’re looking to apprehend.

An occasional hushed phone conversation or private exchange with a friend suggests Rubens’ involvement in something that needs to be kept quiet. But the script by Murilo Hauser and Heitor Lorega, based on the book by Marcelo Rubens Paiva, saves those details until long after Rubens is taken into custody. That puts us in the same position as his wife and children, wondering what their father could possibly have done to place him in the regime’s crosshairs.

The chill of uncertainty is hardest on Rubens’ wife Eunice (Torres), who does what she can to hide what’s going on from the youngest kids. But having armed strangers in their house and a car parked across the street to keep a constant eye on them is tough to explain, and the older siblings are aware something is very wrong.

The situation escalates when Eunice is hauled off for interrogation. With Vera away in London with family friends, the next oldest, 15-year-old Eliana (Luiza Kozovski), is forced to accompany her mother, with bags put over their heads to keep them from knowing where they are being taken.

The interrogation scenes, set in a grim building with confinement cells, are harrowing. Eunice is sequestered for 12 days. Denied contact with the family lawyer, she’s kept completely in the dark about what’s happening to her daughter and is unable to learn where her husband is being held. She’s coerced over and over to identify people in photo files as possible insurgents, but aside from her husband, she recognizes only one woman who teaches at her daughter’s school. Her isolation and fear are made worse by the constant screams of people being tortured coming through the walls.

There are many moments of raw tenderness after Eunice is released — notably when one of her daughters watches from the bathroom doorway, her face a mix of sorrow and terror, as her mother showers away 12 days of grime.

With the government refusing to acknowledge even that her husband was arrested, Eunice continues fishing for information, talking to Rubens’ friends who tell her the military is “shooting blind,” going after random people based on almost nothing concrete. Unable to make bank withdrawals without her husband’s signature, she struggles to keep up with expenses. At the same time, she begins studying the family lawyer’s case file, foreshadowing her eventual decision to relocate with the five children to São Paulo and return to college.

The chief focus of Marcelo Rubens Paiva’s book is essentially his mother’s quiet heroism — first as she single-handedly shoulders the responsibility of keeping the family together and protected, concealing her grief when the inevitable is confirmed, and subsequently when she earns a law degree at 48 and becomes active in a number of causes. That includes pushing for full acknowledgment from authorities of disappeared people like Rubens after democracy is returned to the country.

Salles’ heartfelt film jumps forward 25 years and then by almost 20 more, allowing us to absorb Eunice’s self-reinvention not in big crusading speeches but simply in her dedication to the work of keeping memories alive and not letting the abuses of the past be swept away.

Perhaps the most beautifully observed arc of the film is the gradual rebuilding of the family. As the children grow up and marry and grandchildren come along, they transition back into a noisy, joyful clan much like the one depicted in carefree scenes at the start. Even the simple process of sorting through boxes of family photos is viewed as a loving act of reclamation in a final stretch that will have many audiences in tears.

Torres (one of the stars of Salles’ terrific early film, Foreign Land, co-directed with Daniela Thomas) is a model of eloquent restraint, showing Eunice’s private pain and her necessary fortitude by the subtlest of means. Only once during the film does she raise her voice in anger after a sad occurrence, beating on the windows of the parked car watching the house in Rio and screaming at the two stone-faced men inside.

The final scenes in which Montenegro steps into the role are bittersweet, as Eunice has become nonverbal and uses a wheelchair, in steep decline with Alzheimer’s. The poignancy is almost overwhelming as we watch her gently lean in, her eyes lighting up and a hint of a smile forming, when Rubens’ photograph appears in a television program on the heroes of the resistance.

The movie looks gorgeous. Adrian Teijido’s agile cinematography uses 35mm to great grainy effect to evoke the ‘70s and Super 8mm home movies shot during that decade provide lovely punctuation. The other key asset to the film is Warren Ellis’ score, which starts out pensive and quietly troubling before shifting almost imperceptibly into a much more emotional vein with the surge of feeling that accompanies the forward time jumps.

While it could use a less generic international title that’s not also a well-known Stephen Sondheim song, I’m Still Here is a gripping, profoundly touching film with a deep well of pathos. It’s one of Salles’ best.

#Brazil#TIFF 2024#Venice 2024#Venice Film Festival#Venice Film Festival 2024#Venice Film Festival Reviews#Venice Reviews#Walter Salles#Warren Ellis#Fernanda Torres#Selton Mello#Ainda Estou Aqui#I'm Still Here

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mini Lore Nugget #4:

Mini Lore Nuggets - Masterlist

From Thanxx to Crazy Form, the Black Pirates and Ateez primarily use music as a way to reach people and rebel against Z's dictatorship in order to bring about a revolution.

Out here in the real world, music has also long since been used to protest against governments' abuse of power and foreign occupation, with the most on-the-nose example being The Singing Revolution:

Between 1987 and 1991, the people of Estonia said enough is enough and built up a revolution with the goal of ending the decades-long Soviet occupation of their country. And it worked! In 1991, Estonia reclaimed its independence.

To quote this wonderful website:

In 1947, during the first song festival (Laulupidu) held after the Soviet occupation, Gustav Ernesaks wrote a tune set to the lyrics of a century-old national poem written by Lydia Koidula, “Mu isamaa on minu arm” (“Land of My Fathers, Land That I Love”). This song miraculously slipped by the Soviet censors, and for fifty years it was a musical statement of every Estonian’s desire for freedom.

At the festival's 100th anniversary, the on-stage choirs and audience of over 100,000 people began singing the song - for the second time in recent history - despite direct orders of the Soviets on site. But no one did. The Soviets then tried to drown out the singers with a military band, but it didn't work - there were simply too many people.

1987 and '88 then brought about equally large mass demonstration with over 300,000 people in attendance - all of whom were singing outlawed songs.

This momentum kept going for a total of four years until 1991 when Moscow hard-liners staged a coup d’état and, as the troops rolled into Estonia to shut down any independence movements, Estonians risked it all: unarmed people faced down soldiers and tanks while political leaders assembled to declare Estonia’s independence.

And that was it. Estonia became independent again after a revolution brought about without bloodshed while - around the same time - Lithuania and Latvia also regained their independence from Soviet occupation.

[Additional Source]

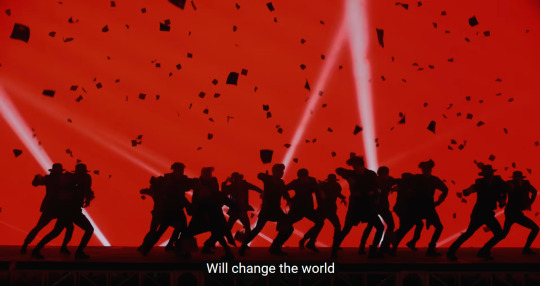

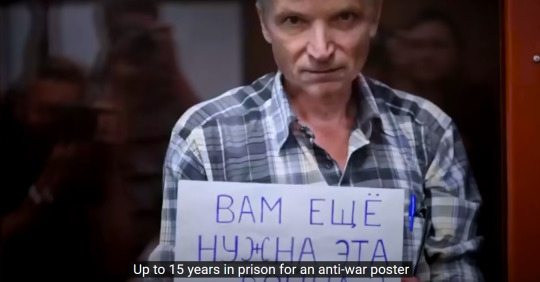

Another notable example would be the Russian feminist punk rock band Pussy Riot:

To quote Westword:

Pussy Riot is the most dangerous punk band in the world, according to the Russian government. The Moscow-based protest collective became a target of the Kremlin immediately after introducing itself in 2011 by sharing its outspoken messages opposing Valdimir Putin and his communist policies via viral guerilla gigs staged throughout the country’s capital.

One of the group's members once told VICE: "We realised this country needs a militant, punk-feminist, street band that will rip through Moscow’s streets and squares, mobilise public energy against the evil crooks of the Putinist junta and enrich the Russian cultural and political opposition with themes that are important to us: gender and LGBT rights, problems of masculine conformity, absence of a daring political message on the musical and art scenes, and the domination of males in all areas of public discourse."

The group was later forced to flee Russia in 2022 after dropping this song which harshly critizices Russia's unprovoked attack on Ukraine and compares the Russian government to Nazis:

youtube

For those of you who cannot access the MV since it's age-restricted, here are a few screenshots:

Another fairly recent example would be the use of Victor Jara's songs at protests in Chile in 2019:

To quote this website:

Massive anti-government protests in Chile over the past few weeks have united demonstrators in song. Last week, up to a million people protesting in Santiago were joined by a cavalry of guitarists. They played a song called "El Derecho de Vivir en Paz," which once stood as an anthem for resistance against the brutal regime of Augusto Pinochet that began in 1973. Written by Chilean composer and singer-songwriter Víctor Jara, "El Derecho de Vivir en Paz" — translated as "The Right to Live in Peace" — was originally a tribute to Vietnamese communist leader Ho Chi Minh. Jara, an outspoken political activist, was imprisoned by the Chilean military during Pinochet's dictatorship, and his song quickly became a protest anthem after Jara was assassinated on Pinochet's orders.

youtube

There are many, many more examples as you can imagine, but I'll leave it at this and encourage you to add to this post in the replies and reblogs if there is a case you believe should be more widely known!

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Uncredited Photographer Workers in the Social Democratic Government of Salvador Allende Being Arrested By US Funded Troops During the Military Coup in Chile 9/11/1973

The other 9/11. Today is the 50th anniversary of the US sponsored and funded coup that overthrew the democratically elected social democratic government of Salvador Allende in Chile, replacing him with a brutal military dictatorship under Augusto Pinochet that ruled and oppressed Chile for the next 19 years.

"Surely, this will be the last opportunity for me to address you. The Air Force has bombed the antennas of Radio Magallanes. My words do not have bitterness but disappointment. … the only thing left for me is to say to workers: I am not going to resign!...T hey have force and will be able to dominate us, but social processes can be arrested by neither crime nor force. History is ours... I address the youth, those who sang and gave us their joy and their spirit of struggle. I address the man of Chile, the worker, the farmer, the intellectual, those who will be persecuted, because in our country fascism has been already present for many hours — in terrorist attacks, blowing up the bridges, cutting the railroad tracks, destroying the oil and gas pipelines, in the face of the silence of those who had the obligation to act. They were committed. History will judge them... These are my last words, and I am certain that my sacrifice will not be in vain..." Salvador Allende, from his final radio address to the Chilean people, shortly before his suicide in the face of what surely would have been his judicial murder had he been captured by the military junta.

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fifty years on, the wounds left in Chilean society by the coup of 11 September 1973 are still very much open. Justice is a long way from being served, secrets remain untold, and the bodies of many of the victims are yet to be found.

Last Wednesday, the government announced a new national initiative to find the remains of 1,162 Chileans who vanished under the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet and remain unaccounted for. In most cases, the best their families can hope for are fragments or traces of DNA.

After ousting a democratically elected socialist, Salvador Allende, Pinochet rounded up opponents, social activists and students in Santiago’s national stadium and other makeshift detention centres, where nearly 30,000 were tortured and more than 2,200 were executed.

Allende’s body was pulled out of the bombed wreckage of the presidential palace, La Moneda. He is generally thought to have killed himself rather than be captured by soldiers loyal to Pinochet, the armed forces commander he had appointed a few weeks earlier.

Almost 1,500 others simply disappeared, and since the end of the junta in 1990, only 307 have been identified and their remains returned to their families. Anticipating the reckoning to come, Pinochet had ordered the bodies of the executed to be dug up and dumped at sea, or into the crater of a volcano. Investigators now hope that modern technology might help pinpoint massacre and temporary burial sites that might still yield vestiges of the dead.

Ariel Dorfman had been working as a cultural and press adviser in La Moneda, and was lucky to survive. Most of Allende’s staff were executed in the first days after the coup.

“This was a tragedy for Chile, for Latin America and for the world, because we were trying to open a way to a more just, radical society without violence,” Dorfman, a novelist, playwright and academic, told the Observer.

Trials are under way in a last-gasp effort at accountability before the perpetrators die of old age. On Monday, seven former soldiers aged between 73 and 85 were finally jailed after the criminal chamber of the Chilean supreme court upheld their convictions for the murder of Victor Jara, a celebrated folk singer and Allende supporter who was tortured and then shot 44 times.

Many of the details of the 1973 coup and the ensuing dictatorship remain unknown. Pinochet and the junta were efficient when it came to destroying evidence and the US has been grudging in declassifying its own records, which have emerged in a dribble over the years. Under pressure from Chile’s current president, Gabriel Boric – a 37-year-old former student activist – and from progressive Washington Democrats such as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the US has declassified two new documents: presidential intelligence briefings given to Richard Nixon on the day of the coup and three days earlier.

It was hard to understand why they had been withheld for so long. They confirmed what had already been generally established: that the CIA had not directly stage-managed the 11 September coup. The presidential daily brief for 8 September contains reports of a plot by naval officers, but adds: “There is no evidence of a tri-service coup plan.”

“Should hotheads in the navy act in the belief they will automatically receive support from the other services, they could find themselves isolated,” the intelligence briefer told Nixon.

Even on the day of the coup itself, Nixon was told that, although some army units appeared to have joined the effort, “they may still lack an effectively coordinated plan that would capitalise on the widespread civilian opposition”.

Jack Devine, who was serving as a CIA clandestine officer in Chile in 1973, was eating lunch in an Italian restaurant in Santiago on 9 September when he got a message to call home. It was his wife, who told him a coup was coming.

One of Devine’s sources, a businessman and former naval officer, was leaving the country and had been unable to find the CIA man, so had gone to his house and told Mrs Devine to pass on his tipoff: “The military has decided to move. It is going to happen on September 11.”

Devine told the Observer: “That is the first clear sign that a coup was coming, just a couple of days ahead of time. We were caught by surprise. That’s the first evidence that something was coming. And many of the people still didn’t believe it in Washington and the CIA.”

There is no question, however, that the US had helped set the stage for the military takeover. From the time of Allende’s election on 4 September 1970 at the head of the Popular Unity alliance, the White House, led by Nixon’s national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, began plotting to get rid of him.

The CIA planned a putsch the following month, before Allende could even hold his inauguration. US spies found willing officers and supplied them with guns, cash and guarantees of US support for a military government. The plot led to the murder of the commander-in-chief, René Schneider, who had stood by the incoming president, but it fell short of toppling Allende when plotters in the military pulled out.

In a telephone conversation on 23 October, Kissinger told Nixon that there had been “a turn for the worse”.

“The next move should have been a government takeover, but that hasn’t happened,” he said, describing the Chilean military as “a pretty incompetent bunch”.

“They’re out of practice,” Nixon replied.

After the failure of the 1970 coup, Devine said, “Nixon sent out specific instructions to the CIA that there be no more coup plotting.” The US administration focused instead on undermining the Allende government, which had been elected by a slender margin and was facing substantial internal opposition. Washington coordinated with its allies in Latin America to block Chile’s access to international finance, persuaded US companies to leave Chile, manipulated the global price of copper, Chile’s principal export, and helped foment strikes within the country.

The Nixon administration was also quick to throw its support behind the junta. When shocked US diplomats sent reports of the slaughter that had followed the coup, Kissinger told his aides: “I think we should understand our policy – that however unpleasant they act, this government is better for us than Allende was.”

Pinochet found another powerful friend on the world stage when Margaret Thatcher was elected in Britain in 1979. She restored Chile’s export credits and dropped an arms embargo on the regime, selling it jet fighters and training its troops.

A succession of Tory ministers visited Chile, admiring the high economic growth rate and the wholehearted adoption of the absolutist monetary policy extolled by Milton Friedman at the University of Chicago. A group of Chilean economists who had studied there, known as the Chicago Boys, took top positions in Pinochet’s government, and the country became a test case for the policies of privatisation, deregulation and tight control of the money supply. Complicating social factors, such as trade unions and popular resistance, had been taken out of the picture.

“The Chilean coup was a triumph of the anti-communist movement in the United States and Latin America. You can’t get around the fact that it led to the defeat of democratic and progressive governments all over the region,” said John Dinges, who lived through the violent early years of the Pinochet era as one of the few US journalists to remain in the country after the coup.

“There was a youth-oriented revolutionary movement, which was sometimes quite extreme, advocating armed struggle, and that was also physically eliminated. So the violence was successful,” Dinges, the author of two books on the Pinochet regime, said. “More than 80% of the population of Latin America was under rightwing military dictatorships by the end of 1976.”

The Pinochet regime coordinated with fellow military-run governments in Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, Bolivia and Brazil to eliminate leftwingers and social activists in Operation Condor, a concerted slaughter across the region. It had US support, in the form of technical support, training and military aid, through the Ford, Carter and Reagan administrations, all in the name of fighting communism.

The coup’s lasting legacy around the world has been defined mostly by the international backlash to its shocking cruelty. It galvanised the human rights movement in Europe and the US. In Washington, the US’s involvement shocked politicians such as Senator Frank Church, who oversaw the first congressional hearings on the CIA’s covert activities which ultimately led to constraints on its future operations.

The martyrdom of Allende and his experiment in democratic socialism inspired a generation of leftwing political activists around the world.

The record of the Allende government is complicated. The Popular Unity alliance never commanded a parliamentary majority and was deeply split. Rapid nationalisation and blanket pay rises for workers brought with them mismanagement of state enterprises and hyperinflation. But because it was violently cut short, many different myths grew up around what might have been.

“It became like a Chilean mirror. People read into Chile what they wanted to see,” said Tanya Harmer, associate professor in Latin American international history at the London School of Economics.

“Across the world, the diverse groups on the left learned the lessons they wanted to learn from the coup. Social democrats viewed it as constitutional democracy overthrown, so it was about the rule of law. The more radical left read it as evidence that you could never have a revolution without an armed struggle.”

Dorfman argues the Allende government and its destruction changed the course of progressive politics. “There were lessons to be learned and they have endured: the need for vast coalitions to effect that structural change, and the way in which Chile’s suffering created a consciousness about human rights violations,” said Dorfman, who has written an assessment of the Allende legacy in the New York Review of Books, and a novel about Allende’s death, The Suicide Museum.

Inside Chile, the coup’s legacy is still being fought over. A recent Mori poll found only 42% of Chileans thought it had destroyed democracy, compared with 36% who said it had saved the country from Marxism.

Peter Kornbluh, a senior analyst at the National Security Archive in Washington, who has led the pressure on the US government to declassify its documents on the coup, warned that denialism about the atrocities of the Pinochet era was strengthening, along with the rise of the far right.

“It is a Rosetta Stone for the discussion over the threat of authoritarianism versus the sanctity of democracy,” said Kornbluh, who is the author of a book based on the documents declassified so far, The Pinochet File. “And Chile is having that debate about its past because it’s dealing with this threat right now – and a number of other countries including the US, and countries in Europe, are facing the same issue.

“The coup in Chile was really the repression of a lot of hopes and dreams around the world, and I think that dynamic still resonates and is still relevant today.”

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chile : death in the south

by Timerman, Jacobo, 1923-1999

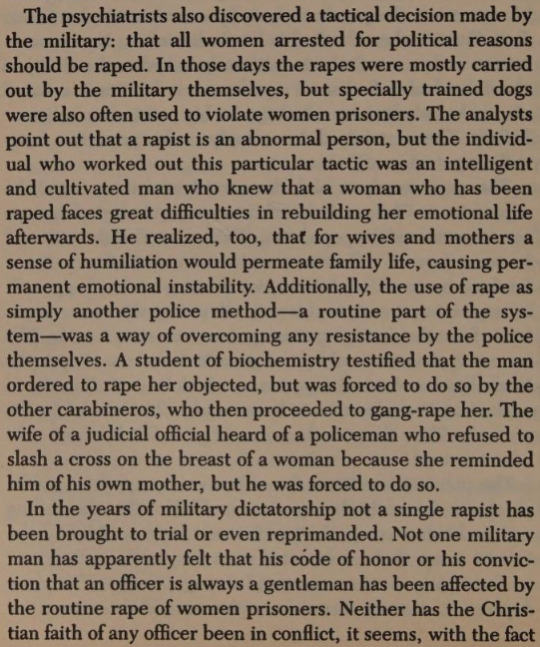

How the Pinochet regime militarized the trauma of abused women as a tactical weapon to terrorize her out of politics. To create long-term emotional instability in the women who could threaten the Junta. Forcing her to deal with her own personal, psychological trauma instead of the nation's.

75 notes

·

View notes

Note

hola. Alanita soy nueva en preguntar algo pero mi pregunta es : quien es Brusz? Y que relación tiene con Dolly ? Porque la e visto juntas pero no sé quién es .

Saludos desde Chile

.

Un personaje nuevo que fue anunciada hace mucho y sale en la peli xd parte 11 o 12

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

On September 15, 1973, it infamously declared that: “The temporary death of democracy in Chile will be regrettable, but the blame lies clearly with Dr Allende. . . . Their coup was homegrown, and attempts to make out that the Americans were involved are absurd.” Over the following months, the Economist continued its apologia for the Pinochet government by countering Western critics of the dictatorship’s human rights record, and flattering its international credibility. Under the header “They mustn’t forget why they struck down Allende,” the magazine announced in October 1973 that: “The junta has been the victim of a campaign of organised hostility in the west as well as of its own mistakes”. The article continued: “Perhaps the imposition of martial law, the mass interrogations and the summary execution of snipers would not have aroused so much criticism if there were a clearer understanding of the events that precipitated the coup.” Meanwhile, the Economist helped to shift responsibility for the coup onto the Chilean left by propagating the claim that “the extremists in the Allende government were preparing an insurrection of their own ‘to complete the revolution.’” It continued: “The only doubt is whether Dr Allende himself would have played the role of Lenin or Kerensky if that had finally come about.”

67 notes

·

View notes