#judex 1916

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

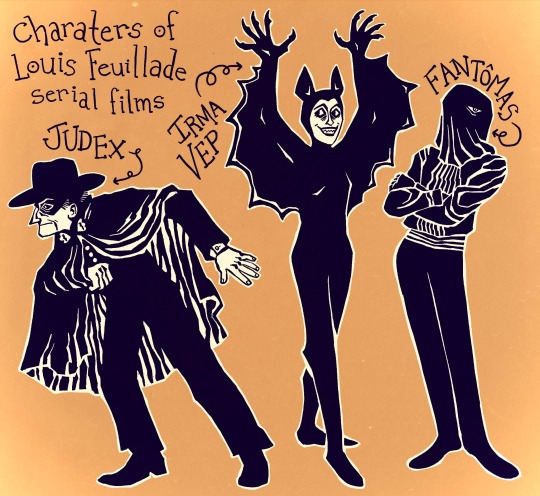

I’ve been watching some Louis Feuillade (<- French director, known mostly for his 1910s pulp crime films)

#louis feuillade#Les vampires 1915#fantômas 1913#fantômas#judex 1916#judex#my art#all of these have been fun! I do think Édouard Mathé should have played fandor in fantômas#doodled this because I’ve been having trouble finding fanart of my fav weird old films. be the change you want to see etc etc

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louis Feuillade, {1916} Judex - Episode 11: L'Ondine (The Water Goddess)

#film#gif#series#louis feuillade#judex#l'ondine#the water goddess#1916#silent cinema#silent film#1910s#male filmmakers#france#people#men

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Favorite Silent Films:

Der Student von Prag (1913) Directed by Stellan Rye

Cabria (1914) Director Giovanni Pastrone

Fantômas (1916) Director Louis Feuillade

Les Vampires (1915) Director Louis Feuillade

The Birth of a Nation (1915) Director D.W. Griffith

Judex (1916) Director Louis Feuillade

J'accuse (1919) Director Abel Gance

Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (1920) Director Robert Wiene

Körkarlen (1921) Director Victor Sjöström

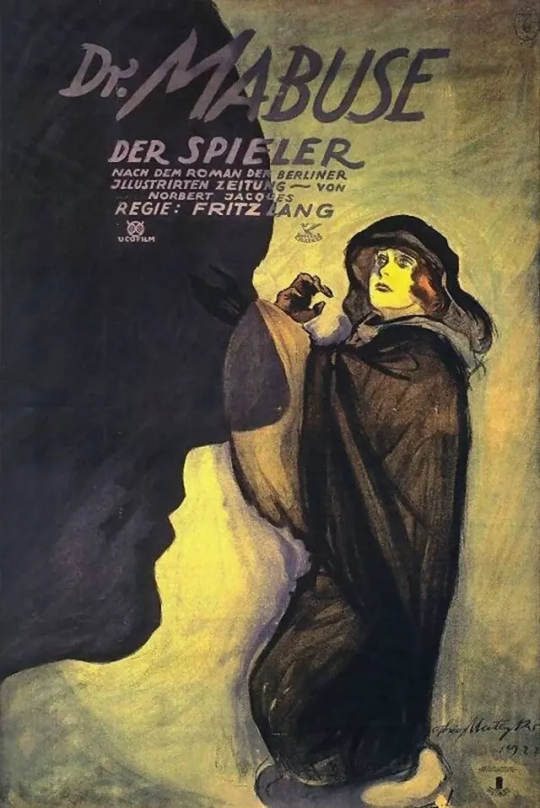

Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (1922) Director Fritz Lang

The Saga of Gösta Berling (1924) Directed by Mauritz Stiller

Bronenosets Potyomkin (1925) Director Sergei Eisenstein

The Phantom of the Opera (1925) Director Rupert Julian

Napoleon (1927) Director Abel Gance

Metropolis (1927) Director Fritz Lang

#silent film#silent cinema#silent era#1910s movies#1920s movies#Der Student von Prag#Stellan Rye#Cabria#Giovanni Pastrone#louis feuillade#fantômas#les vampires#judex#The Birth of a Nation#d.w. griffith#j'accuse#abel gance#Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari#robert wiene#1920s horror#Körkarlen#the phantom carriage#victor sjöström#fritz lang#Dr. Mabuse der Spieler#mauritz stiller#The Saga of Gösta Berling#Bronenosets Potyomkin#sergei eisenstein#The Phantom of the Opera

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Judex, Louis Feuillade, 1916

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

1,000 Greatest Films: Les Vampires

The title is French, you pervert; there's no lesbians in this movie. Or vampires in the strictest sense. This old film isn't a horror movie, it's the great grandmother of pulp thrillers and it sets the family traditions quite strongly. It's also not "a film" really. It's ten, stretching across some seven hours of high society, criminal conspiracies, coded messages, disguises, hypnosis, and enough poison to kill a small village, each dose laced on an item more innocuous than the last.

Released across 1915 and 1916, Les Vampires was not Louis Feuillade's first rodeo. A survivor of Catholic school and the draft, Feuillade had hoped to make it big in journalism or literary circles, but thankfully that was not to be. Instead, in 1905 he switched to screenplays and was picked up by Gaumont, a film studio which not only survives to this day but is in fact the oldest one in the world. It took him a couple of years after this to start directing, but once he did he spent the rest of his life - some eighteen years - making films for them and on his own.

Feuillade's early work was clearly inspired by Georges Méliès's, meaning that we're only three films into this chronology and already tracing inspiration. However, he soon took off with the serial film genre. While some, like his Bébé Apache, were light-hearted, three are generally considered to be a trilogy of masterpieces.

The first, Fantômas, was an adaptation of a novel, so it's really for the best that we aren't covering it in much depth because that would be 0 for 3 films so far that are original works. It was another crime serial, vastly popular and almost certainly establishing the titular character amid France's culture heroes. Interestingly, the audiences of the day would not have viewed it as a suspense: much like the original viewers of Greek plays, they already knew how the stories went and were instead watching to see what spin the films would bring to them.

The third, Judex, was made as a response to the moralistic critique of both Fantômas and Les Vampires, featuring a pulp hero instead of a villain, though one whose secret identity and quest for revenge gave him the trappings of crime villains without the corrupt motivation. He was likely something of an inspiration for various pulp characters and superheroes later developed in America, but is beyond our scope.

Les Vampires is our delightful middle child, and the character it brought to the French pantheon was not a man at all; heroes Philippe Guérande and Oscar-Cloud Mazamette are plucky and fun, but hardly the stars. Nor were the rotating cast of male villains, most assuming the title of Grand Vampire due to the defeat and death of their predecessor, much to write home about. Instead we turn to a character not introduced until episode three: the performer Irma Vep (yes, her name is an anagram for Vampire, what's your point?). Vep engages in one scheme after another, most involving disguises so paper-thin that Philippe mainly survives the story because he keeps recognizing her whenever they cross paths. Yet as much as you don't want Philippe to die per se, you can't help but root for her!

Unless of course you're one of those moralistic critics I mentioned earlier. Even more than its predecessor, Les Vampires was critiqued for glorifying crime and criminals, and probably corrupting the youth and encouraging them to talk back to their elders and whatnot. Some people said it lacked the artistry of The Birth of a Nation, and I like to think that those people were all killed by the influenza epidemic a couple years later, or maybe executed for collaborating with the Nazis a couple decades after that. Les Vampires makes no pretension towards being an epic, it just wants to be fun, and thankfully in recent years film critics have come to understand that it's actually really good at that.

Because I wasn't kidding in that opening paragraph - this movie has poison pens, poison pins, poison pills, poison rings, poisoned dinners, and at one point an entire party of rich idiots at a hotel are all poisoned by gas from the vents. Vep is hypnotized by the only male villain of any real worth, Moréno, the leader of a rival gang, and shoots the first of the Grand Vampires at his command. Later she escapes being sent to a penal colony when her co-conspirators blow up the boat transporting her. Philippe's mother is nearly killed by a deaf-mute priest when she won't sign a ransom note. The inciting incident of the film is a decapitation and Phillipe is nearly framed when the head shows up in a secret passageway in the room he's staying at. Mazamette spends seven movies getting warnings from various authority figures that they're all sick of his kid's shit and when he's kicked out of school he naturally joins in the investigation. There's some rare female cross-dressing with Irma Vep in one classy suit with her hair slicked back. This kind of stuff is basically heroin to a viewer like me.

But that seven hour runtime is one hell of an overdose. I watched this over the course of four nights and honestly even spacing it out found it very hard to focus on the last pair of episodes. Vep is a constant delight of course, and the very last villain to fall. Sadly, there's really one too many Grand Vampires and Moréno has an ignominious defeat, being arrested at the end of one movie and committing suicide off-screen before the start of the next. Philippe having a previously-unmentioned fiance in episode two is perfectly acceptable from a storytelling perspective; getting another one in episode nine (the first one is fatally poisoned in her debut) seems mostly about providing an expected romantic happy ending. More so when Mazamette's love interest is introduced as the widow of a concierge who was poisoned by wine intended for Philippe and his family. (People do die in other ways than poison, I promise.)

But these are quibbles. After the first two films, this particular picture shows just how much the medium is growing. Lune barely had distinguishable characters at all, Nation had a bunch of half-dimensional caricatures running around inspiring racism. Les Vampires' character arcs may only be an inevitability of a seven-hour runtime, but all three main characters are quite distinct.

Édouard Mathé plays Philippe as a quite unflappable character, something of the straight man of the cast. A journalist brought into the story simply by trying to investigate the Vampires for his newspaper, he proves his heroic worth both by his refusal to ever abandon the case despite the constant threats against him and his loved ones and also by the mercy he shows to Mazamette (Marcel Lévesque), a low-level member of the Vampires who pleads for mercy and ultimately becomes Philippe's sidekick in the investigation.

Les Vampires isn't a comedy, but Lévesque brings a great many of the comedic moments to the story. The running gag of his criminal efforts to pay for his son's schooling runs through the first half of the story of course, but far more interesting is that Mazamette (and his son in his singular appearance) is the only character permitted to make the "aside glance". He is just as confounded by the goings-on of the story as the audience is likely to be, and I'm actually quite surprised that this technique evolved so early in cinema's history.

And of course, we have our femme fatale herself, the actress Musidora. Born Jeanne Roques, Musidora was a pioneer for women in film, if not humility (her stage name means "gift of the muses"). But why be humble when you're writing novels as a teen and chumming around with Colette? Musidora also may be the first of the vamps, as she started wearing her distinctive semi-gothic makeup at about the same time as Theda Bara did in the US. But even this wasn't enough for her: Feuillade tutored her in their collaborations and she explored her own works as a director and producer, one of the few women to do so at the time. Tragically, most of her work is lost.

Irma Vep is a powerful character who demands the camera's attention in every scene she's in. Whether she's disguised or simply in her catsuit, she is just as determined as Philippe and trying to rob everyone around her blind. I wish I could call the character a surprising icon for feminism, but she does spend a good deal of time as a damsel in distress for the bad guys. Even this doesn't fully get her down though; in episode nine she manages to find a way to call for help even when gagged and bound. Worse, she of course falls in love with Moréno after he's hypnotized her (no seriously, after she's no longer hypnotized, so at least there's consent), because if women are sexually turned on by anything it's Stockholm Syndrome I guess? Not a great look, but if you can get past this sort of thing, at least having been forewarned by yours truly, then Les Vampires otherwise really does hold up for a 1910s production. Just don't try to watch it all in one go.

Next time, we give D. W. Griffith a second chance with a movie that is entitled Intolerance. Wikipedia says it was made in response to the racial criticism of The Birth of a Nation so that's...

Bleak...

But at least it didn't inspire the KKK, so I'll try and give it an unbiased view.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

LES VAMPIRES (1915-1916) B&W SILENT

(1239)

Les Vampires is a 1915–1916 French silent crime serial film written and directed by Louis Feuillade.

Set in Paris, it stars Édouard Mathé, Musidora and Marcel Lévesque. The main characters are a journalist and his friend who become involved in trying to uncover and stop a bizarre underground Apaches criminal gang, known as the Vampires (who are not the mythical beings their name might suggest).

The serial consists of ten episodes, which vary greatly in length. Being roughly 7 hours long, it is considered one of the longest films ever made. It was produced and distributed by Feuillade's company Gaumont. Due to its stylistic similarities with Feuillade's other crime serials Fantômas and Judex, the three are often considered a trilogy.

link https://ok.ru/video/6302813719291

The film starts off with chapter 1 Severed Head. By clicking on green it will take you directly to Wikipedia description of chapter which also includes the video.

1-"The Severed Head" go to minute of the film......

2-"The Ring That Kills"go to minute 34:33

3-"The Red Codebook" go to minute 49:37

4-"The Spectre" go to minute 1:30:46

5-"Dead Man's Escape" go to minute 2:03:21

6-"Hypnotic Eyes" go to minute 2:41:36

link https://ok.ru/video/6302859725563

Part 2 starts off with chapter 7 "Satanas". By clicking on green it will take you directly to Wikipedia description of chapter which also includes the video.

7-"Satanas"

8-"The Thunder Master" go to minute 44:26

9-"The Poisoner" go to 1:36:28

10-"The Terrible Wedding" go to 2:26:17

silent age vamp: musidora as irma vep in the vampires: the ring that kills (1915) blog source silentagecinema origin Jul 16

NOTES:

Films directed by Louis FeuilladeFilm serials

Fantômas (1913–14)

Les Vampires (1915–16)

Judex (1916)

Tih Minh (1918)

Barrabas (1920)

Parisette (1921)

The Two Girls (1921)

Short films

A Roman Orgy (1911)

La hantise (1912)

Bout de Zan et l'embusqué (1915)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Quiet, Please! It's a double-feature of French films paying homage in their own unique ways to the lost-art of the silent movie. "Yo Yo" follows the ups and downs of a father -- bored and rich, finding happiness when he's broke and on the road with the circus -- and then, his son -- taking the opposite track, trying to regain and restore his father's riches and manor via his increasingly-profitable career as a clown. Despite the surrealism of the wonderful and non-stop (and mainly silent) sight gags, this comedy surprised me as it revealed itself by the end to be quite an emotional journey, too. Starring and directed-by Pierre Etaix, former assistant to comic film-master Jacques Tati, "Yo Yo" even got on grumpy old Jean-Luc Godard's list of best films for 1965. The crime thriller "Judex" is George Franju's 1963 remake of Louis Feuillade's 1916 silent film serial about a hawk-eyed vigilante taking vengeance on a corrupt banker who caused the death of his father. Judex's penchant for disguises and legerdemain -- one of the stand-out scenes is his appearance as a silent bird of prey at a masked ball -- keeps the proceedings much more lively than anything else about the title character, but the real star who keeps things going is Francine Berge's villainess. Whether dressed as a nun or sneaking through the shadows dressed in black leotards, Berge is an unpredictable and murderous force. And then there's equal kudos for the unearthly dream of Edith Scob as the damsel in distress. Both are playing now on the Criterion Channel, though you can find Judex for free with your library card on the Kanopy app, if the service is offered by your local public library. I'd heard of Etaix for a long time and very glad I finally got to see this, will be looking into watching the rest of his films.

0 notes

Photo

Musidora dans "Judex" de Louis Feuillade, 1916 Cinémathèque Française

101 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Judex de Louis Feuillade – 1916, Gaumont

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Judex (1916) dir. Louis Feuillade

Little did they know, electronic surveillance would become real.

46 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Judex (1916)

Film review #316

SYNOPSIS: A notorious banker named Favraux, whose practices have taken advantage of numerous people, receives a letter from a man calling himself Judex, who claims that if he does not donate half his fortune, he will meet his end. With Favraux’s seeming death by poisioning at the hands of Judex, Favraux’s daughter renounces her Father’s fortune and beings a humble life, as Judex silently watches her from the shadows to protect her. However, a pair of criminals find out that Favraux is still alive and being held by Judex, and seek to free him so they can hold him for ransom...

THOUGHTS/ANALYSIS: Judex is a 1916 French silent-film serial consisting of twelve chapters. The film begins showing Favraux, an accountant who has swindled many people out of their money over his career, driving some of them to suicide. When an elderly man named Pierre Kerjean comes by his house asking for help, Favraux turns him away and later nearly runs him over. Favraux’s assistant Vallieres hands him a letter saying that Favraux’s actions have ruined many people’s lives, and if he does not donate half his ill-gotten fortune to the public assistance bureau by 10pm tomorrow, he will meet his end. The letter is signed only by the name “Judex”, and Favraux sees fit to ignore the threat. However, sure enough, at 10pm he collapses and seemingly dies. His daughter Jacqueline, learning of her Father’s misdeeds, renounces his fortune and goes to make her own money with her son Little Jean. But it turns out that Favraux is not dead, he was only put into a comatose state, and Judex has decided to keep him locked in captivity for the rest of his days. Judex also decides to watch over Jacqueline, as it seems there are a pair of criminals who are after her. The story of this serial is quite complex, and there is plenty of content to enjoy. With each installment, some of the characters face new problems and situations, and this affects the story as a whole in such a way that nothing feels like it is there just to fill out time. Each of the characters get focused on at different points, so they all seem well developed, which allows a viewer to really get to grips with their motivations, and connect with them on an emotional level.

The themes of redemption and vengeance are dominant through this film, and are explored thoroughly, leading to some dramatic and emotional scenes at its peak. We learn that Judex is actually Jacques de Tremeuse, the son of a man who was swindled by Favraux, causing him to commit suicide, after which his Mother made Judex and his brother swear to avenge their Father’s death, and it is revealed that he is Vallieres, and got the job as Favraux’s assistant to get close to him. He becomes unable to fulfil his oath to his Mother by killing Favraux when he fallls in love with Jacqueline, and he must convince his Mother to forgive Favraux and let him go back to his daughter. There are all sorts of complexities in the story that I could go into, but they all centre around these themes. The characters all have their own personalities, from the heroic yet troubled Judex, to the villainous Diana Monti, who herself deceived Favraux to be hired as his housekeeper to get at his fortune. There’s also the comedic Cocantin, who provides light relief alongside the Liquorice Kid (who’s a pretty good child actor). There’s not a poorly developed character in here, and they all play a significant part in the film.

I think one of the most interesting things about this film is that Judex could be considered one of the first proto-superheroes: he has a hidden base full of gadgets and strange devices, he has a secret identity running about in a cape, and a complex backstory that could rival Bruce Wayne. It all adds up to an exciting serial that has high drama, emotion and action backed up by strong characters that can appeal to fans of all genres. Definitely one of the better serials I have seen.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jeanne Roques (23 February 1889 – 11 December 1957), known professionally as Musidora, was a French actress, film director, and writer. She is best known for her acting in silent films, and rose to public attention for roles in the Louis Feuillade serials Les Vampires as Irma Vep and in Judex as Marie Verdier. Born Jeanne Roques to music composer and theorist of socialism Jacques Roques and painter and feminist Adèle Porchez, Musidora began her career in the arts at an early age, writing her first novel at the age of fifteen and acting on the stage with the likes of Colette, one of her lifelong friends. During the very early years of French cinema Musidora began a professional collaboration with the highly successful French film director Louis Feuillade. She made her film debut in Les miseres de l'aiguille, directed by Raphael Clamour, in January 1914. The film highlights the problems of the urban women in the French working-class, and presents a new representation of the female even by the working-class movement in the early 20th century in France. Adopting the moniker of Musidora (Greek for "gift of the muses"), after the heroine in Théophile Gautier's novel Fortunio, and affecting a unique vamp persona that would be popularized in the United States by actress Theda Bara at about the same time, Musidora soon found a foothold in the nascent medium of moving pictures. With her heavily kohled dark eyes, somewhat sinister make-up, pale skin and exotic wardrobes, Musidora quickly became a highly popular and instantly recognizable presence of European cinema. Beginning in 1915, Musidora began appearing in the successful Feuillade-directed serial Les Vampires as Irma Vep (an anagram of "vampire"), a cabaret singer, opposite Édouard Mathé. Contrary to the title, Les Vampires was not actually about vampires, but about a criminal-gang-run-secret-society inspired by the exploits of the real-life Bonnot Gang. Vep, besides playing a leading role in the Vampires' crimes, also spends two episodes under the hypnotic control of Moreno, a rival criminal who makes her his lover and induces her to assassinate the Grand Vampire. The series was an immediate success with French cinema-goers and ran in 10 installments until 1916. After the Les Vampires serial, Musidora starred as adventuress, Diana Monti (aka governess "Marie Verdier") in Judex, another popular Feuillade serial filmed in 1916 but delayed for release until 1917. Though not intended to be avant-garde, Les Vampires and Judex were lauded by Louis Aragon and Andre Breton in the 1920s for the films' elements of surprise, fantasy/science fiction, unexpected juxtapositions and visual non sequiturs. Filmmakers Fritz Lang, Luis Buñuel, Georges Franju, Alain Resnais, and Olivier Assayas have cited Les Vampires and Judex as influencing them in their desires to become directors. At a time when many women in the film industry were relegated to acting, Musidora achieved a degree of success as a producer and director. Musidora became a film producer and director under the tutelage of her mentor, Louis Feuillade. Between the late 1910s and early 1920s, she directed ten films, all of which are lost with the exception of two: 1922's Soleil et Ombre and 1924's La Terre des Taureaux, both of which were filmed in Spain. In Italy, she produced and directed La Flamme Cachee based on the work of her friend Colette. In the same year, she co-wrote (with Colette) and co-directed (with Eugenio Perego) La vagabonda based on Colette's novel of the same name. After her career as an actress faded, she focused on writing and producing. Her last film was an homage to her mentor Feuillade titled La Magique Image in 1950, which she both directed and starred in. Late in her life, she would occasionally work in the ticket booth of the Cinémathèque Française—few patrons realized that the older woman in the foyer might be starring in the film they were watching. Musidora died in Paris in 1957 and was buried in the Cimetière de Bois-le-Roi.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louis Feuillade, {1916} Judex: Prologue

#film#gif#series#louis feuillade#judex#prologue#1916#silent cinema#silent film#1910s#cemeteries#people#men#male filmmakers#tinted#france

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who is Judex?

On paper, Judex is a proto-Shadow and little else. He is a mysterious avenger who wears a cloak and dark hat while enacting retribution on evildoers. He is a master of disguise, has a group of ex-criminals and circus people acting as agents helping him, has high tech devices, mysterious headquarters, incredible abilities, etc. He trains a large pack of dogs and a small flock of birds to be his helpers, he has a main sidekick in his brother Roger. He even has a very superhero-esque backstory where his father was driven to suicide by the machinations of an evil banker, and his mother forced him and his brother to swear dedicating themselves wholesale to avenging their father, and who now metes out dark justice, not above poisoning his enemies or walling them up alive, and who ultimately finds redemption thanks to his loved one.

Contrary to what you might assume, Judex was not one of the influences on The Shadow, as there appears to be no evidence the 1916 serial was released in the US (The New York Board of Censorship records contain no listing for Judex) or that Gibson was even aware of it’s existence even if it was available to him, and he’s always been very open about all of his influences that went into The Shadow (most of which had nothing to do with detective characters, by his own admission he barely read those kinds of stories and was far more inspired by the likes of Dracula, King Arthur and the Oz stories as well as his own experiences with Houdini and Blackstone in creating the character)

But Judex and The Shadow are very often connected by virtue of being so similar to each other. The S&S Shadow Comics of the 40s were even published in France as Judex stories, with nothing about their contents changed at all other than the name of the titular character. Even the identity of Lamont Cranston stayed, confusing fans who were previously familiar with Judex’s real identity being Jacques de Tremeuse.

(Even Shiwan Khan was there)

Nowadays, Judex largely exists as a public domain Shadow. He’s shown up in stories from the Tales of The Shadowmen anthologies, which largely use him as an “almost” Shadow, a diet Shadow that you can use willy nilly without pissing off Conde Nast’s lawyers. It’s hard to really think of him having utility for much else.

Thing is, Judex is not The Shadow. It’s the differences between the two, and the unique situation of Judex himself, that makes him interesting, on his own and in the context of The Shadow.

Judex is a bridge in more ways than one, joining the he detective and costumed adventurer heroes from the turn-of-the-century as well as the pulp characters and superheroes of the slightly later 20th century. Judex was also a turning point in the career of serial filmmaker Louis Feuillade, who had achieved great popularity with his Fantomas and Les Vampires serials, and had attracted a ton of criticism for films that glorified master criminals. So in turn, Feuillade and writer Arthur Bernède created Judex as a character ostensibly in the “master criminal” mold of Fantomas, but who would be a good-natured promoter of wholesome values.

Still a black-clad figure of mystery and intrigue moving outside the bounds of society and commanding fear with his great powers, but only going after evildoers. A mastermind of crime who wouldn’t upset the authorities boycotting the previous films. It’s fitting that Judex largely exists as a diet Shadow nowadays, because the whole point of his creation was for him to be a diet Fantomas. A family friendly Fantomas. It was that connection to Fantomas that ultimately got Georges Franju to accept making a Judex film in 1963.

Strangely enough, I actually discovered Judex long before The Shadow, due to the Georges Franju film. Eyes Without a Face was a formative experience for me at a young age, and I was compelled to look at the rest of his filmography, which led to me watching Judex. At the time, the scene of the titular character entering a party and performing magic tricks with that eerie bird mask was extremely captivating, and yet, I remembered absolutely nothing else about the film. I found it too slow, clinically detached and drowsy, I could not finish it without falling asleep, and never finished it then. Only years later did I ever finish the film, and honestly, that ballroom scene is still the only thing that really, really lives rent free in my brain.

Franju’s film abandoned all pretense of giving any sort of character to it’s titular hero. Franju himself primarily wanted to do a Fantomas film first and foremost, but when he couldn’t attain the rights, he settled for Judex, a character he didn’t like very much. He even stated he viewed Judex as a villain, who envelops the other characters in his darkness. Franju’s Judex is impressive only in the initial scene where he performs the magic trick in the bird mask. The backstory of the original Judex is hardly acknowledged, and past that scene, and past the scene when Favraux’s daughter Jacqueline catches him in the act of changing out of the secret identity he has assumed for much of the movie, whatever mystique he may have had is gone, and he gradually fades more and more into pretext as the film’s female protagonists take center stage, the main drama of the film and it’s central poetic scenes really played out between the two women, with the hero a more or less helpful onlooker.

Well into its third act, there’s a scene where Jacques bursts through a window to assail his enemies, only to allow one to step around him, pluck a conveniently placed brick from the floor, and sock him unconscious from behind. It’s not even a fight sequence. It may very well be the least superheroic superhero movie ever made, if considered as one. “There isn’t really any humanity in Judex,” Franju told Cahiers du cinéma, “and where there’s no humanity, there’s no drama.” Judex completely lacks the strong, dominant personality and presence that allows The Shadow to always stand out no matter what story he’s in. Judex has little to him, once you get past the backstory, the black hat and cape and the mysterious trappings of his resources. And that’s kind of the point. Judex is an anti-hero in the most classical sense, because being Judex sucks, Jacques has little life outside of it, and he doesn’t like it. He never asked for any of this.

The Judex films have an interesting relationship with the usual tropes of adventure serials, paced and edited and presented differently than what we tend to think nowadays regarding serials. The action is often brisk, too fast-paced or ignored, and every death in both Judex films is anti-heroic, and deeply sad. Feuillade lingers on the pleading eyes of a man shot down after a car chase, where as Franju lingers on the isolation and vacant space of Jacqueline’s lair after she gives away her fortune, as she wanders around, orphaned. On both films, when Diana Monti, the real most dangerous villain of Judex and a character that steals the show in both appearences, meets her end, both scenes are played for great tragedy.

The Judex serial is an adventure that’s all about being nice and reforming. Locations are heavily bucolic and set in either large, lavish manors, or an idyllic countryside, setting the work apart from the urban simmer of earlier serials, and implicitly celebrating a simpler way of life. It was a wartime release that doesn't admit a war is even happening.

Judex has an odd vulnerability to him. He is often crippled by self-doubt. He is assisted by his brother and mother. He takes enormous risks to effect reconciliation between a father and a wayward son. After the kidnapping of Favraux, he never attacks thugs or the like, only using lethal force for self-defense. His hatred toward Favraux is softened by his love for Jacqueline and her love for her father, and at some point, when his faith in his mission of revenge fades, the very first thing he does is travel to the family estate in full costume and ask his mother permission to call off the vengeance.

In fact, Judex is a lot more family drama than it is an adventure serial. Almost every character in Judex, with the exception of Diana Monti, either nurtures their family bonds, or creates them if they do not have them already. The capers and chases are there aplenty, but the real focus is on relationships, love, hate and everything in between. As Brian Hibbs puts it in his Judex review:

Put simply, with Judex, the superhero is not a dream of protection in which the madness of modern living springs out with might and fury to save us from our fellow humans. Rather, the superhero is anarchy's domestication, a fantasy of the madness itself calming into the status quo and realizing virtue.

Anarchy that wouldn't piss the police off. A Fantômas you could take home to grandma. And even better - over the course of his adventure he'd learn compassion, fall in love with a sweet girl, and insert himself smoothly into clean bourgeoisie living.

Could it be the ultimate wartime fantasy?

In that light, the 1963 film not only acknowledges the denial of war in the original serial and it’s idiosyncrasies, but turns the subtext into the text. Franju’s Judex condenses the serial, strips it of logic and plot, and in the process fragments it into what was popular about it, the imagery. Franju’s Judex is set in a similar blend of documentary and dream as Eyes Without a Face, a black and white series of stills capturing a time that does not exist outside of what you’re seeing right now. I’ll paste here segments from Geoffrey O’Brien’s review:

We’ve been here before—we’ve seen this idyllic park, this dark carriage, this belle epoque ballroom, this drawer full of secret documents, this mask, this dagger, this false telegram, this ruined château; we’ve already lived through, or dreamt through, these robberies and midnight exhumations.

Where Feuillade moves at a relaxed trot, casting an eye over the passing landscape and savoring comic and sentimental interludes along the way, Franju extracts the imagistic essence of every plot turn, so that his movie seems all high points, every shot climactic, with no downtime whatsoever. The sense of time is precisely what gets suspended in Franju’s Judex.

It has always seemed to me a movie out of time, a movie made despite time. It is neither of 1916 nor 1963, and while we are watching it, we seem to be living in an alternate dream time not measurable by the clock. Incident moves rapidly on incident, yet the whole film feels caught in a peculiar immobility, as if we were allowed to indulge the fantasy of moving at will between past and present or freezing a cherished moment forever.

Franju had no wish to condescend to the material he was working with. He was perfectly happy to jettison the dross of outmoded sentiments and moral justifications in order to preserve, as in a fantastically concentrated tincture, what remained of ultimate value in Feuillade: “The dreamlike quality of the spectacle, the poetic logic of the spectacle.”

It is a cinematic paradise, evoking a world that at that very moment was being irrevocably swept away. For Franju, it was linked, as he acknowledged, to his memories of childhood. He was four years old when Feuillade’s film came out, right in the middle of the Great War, of which he was at that age blissfully unaware.

Judex’s melodramatic crises are framed—casually by Feuillade, and with fervent and fetishistic devotion by Franju—by the design and texture of clothes, furnishings, hallways, gardens, the accoutrements of a world apparently stable. But this was a paradise already lost in the moment of its inception, and it is not so much a question of bringing it back to life as of creating it again, through the alternate reality of cinema.

The tale is done, the heroine is rescued, the lovers stroll along a misty beach: a happy ending out of an old movie. At this point, Franju superimposes a title—just as, at various junctures in the film, he has interpolated intertitles in the manner of the original serial—and at just this last moment injects a startling emotional shock: “In homage to Louis Feuillade, in memory of a time that was not happy: 1914.” It is the year that is made to stand out in boldface, the fatal date that, merely by being evoked, places everything we have just experienced in a different light. A hidden grief is allowed to escape, and the fragility of the pleasures we have been savoring is made even more achingly apparent.

Judex’s primary adventures never continued after the war. The end of Judex is him finding happiness and putting the costume to rest, as he walks off with his love. The serials made in 1917-18 took place in 1913. The two remakes, one in the 30s and the Franju one in the 60s, were remakes of the first story. The Judex adventures of the 40s were Shadow stories with a name change. The last time the character has showed up in any capacit in original stories was in Tales of The Shadowmen, in stories that largely just paint him as The Shadow, but French and far more tame in personality.

It’s an interesting coincidence that the timeline of Judex (the first two serials taking place in 1913) seems to end near exactly where that of The Shadow begins (1912, when Kent Allard first goes to Europe), and in locations close to each other.

Perhaps the question isn’t so much “who” is Judex, as it’s “where” is Judex. Where did he go? What place is left for him?

One could easily imagine Jacques de Tremeuse running into Kent Allard in France, maybe passing a few lessons to someone far more driven and comfortable with violence, with far less self-doubt and a mission that extends far beyond the bourgeous landscape.

That is, assuming Jacques made it past the Great War, since there are no adventures for him beyond it. As a public domain character, you could very well write a story right now where Judex shows up anywhere, doing anything, but there is no place for Judex beyond the French countryside and the black and white manors he skulks around in. There may be no place for Judex in the world of costumed avengers that is occupied by his descendants. Nobody is clamoring for Judex to return, and Judex himself has no business left to take care of.

Time has trapped Judex in place, and yet he exists outside of it. Perhaps that’s where he finally found peace, along with Jacqueline and all the other players that starred in his adventures. In dreams only captured through celluloid. Peace may be all he ever asked for.

Maybe he waits for the day his other “brother” may find peace of his own.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

may 2020

i keep forgetting i want to post these here!!!!!! anyway, here are the movies i watched on may 2020, my favorites are in bold. i was trying to decide if i should add shorts or not but, well, i watched them so i did put them in with a *. also i watched les vampires separately (as it is a serial) but i added the entire thing. it was not a great month mental health wise hence all the mary pickford shorts (i needed her), and not my best for the amount of free time i have, but it was.. fairly productive. i guess. i rewatched a couple movies too and those rewatches only made me love them more, but thats between me myself and my mental illness.

Pánico (Julián Soler, 1966 or 1972 depends on who u ask)

Night Tide (Curtis Harrington, 1961)

Dream Demon (Harley Cokeliss, 1988)

L'anticristo (Alberto De Martino, 1974)

Another Day, Another Man (Doris Wishman, 1966)

The Way You Wanted Me (Teuvo Tulio, 1944)

Shoes (Lois Weber, 1916)

A Corner in Wheat (D. W. Griffith, 1909)*

The Lonely Villa (D. W. Griffith, 1909)*

Won by a Fish (Mack Sennett, 1912)*

A Gold Necklace (Frank Powell, 1910)*

Lena and the Geese (D. W. Griffith, 1912)*

An Indian Summer (D. W. Griffith, 1912)*

Japanese Girls at the Harbor (Hiroshi Shimizu, 1933)

What’s Your Hurry? (D. W. Griffith, 1909)*

The Newlyweds (D. W. Griffith, 1910)*

The Light That Came (D. W. Griffith, 1909)*

The Mountaineer’s Honor (D. W. Griffith, 1909)*

All on Account of the Milk (Frank Powell, 1910)*

The Day After (D. W. Griffith, 1909)*

A Beast at Bay (D. W. Griffith, 1912)*

The Unchanging Sea (D. W. Griffith, 1910)*

The Wizard of Gore (Herschell Gordon Lewis, 1970)

Emma. (Autumn de Wilde, 2020)

She-Devils on Wheels (Herschell Gordon Lewis, 1968)

Evil Dead Trap 2: Hideki (Izo Hashimoto, 1992)

Muggsy Becomes a Hero (Frank Powell, 1910)*

Sin You Sinners (Anthony Farrar, 1963)

Judex (Georges Franju, 1963)

Les Vampires (Louis Feuillade, 1915)

Les amours jaunes (Jean Rollin, 1958)*

Darling, Do You Love Me? (Martin Sharp, 1968)*

Woman (Keisuke Kinoshita, 1948)

Killing Car (Jean Rollin, 1993)

#hannalog#this reminds me to continue watching the shorts bc i need to add posters on tmdb :-)#ok i changed to bold bc i couldnt read properly kldsfms

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

True Best Movie: Georges Franju

After Chaplin's TBM, let's go for Georges Franju.

Usual Best Movie: Les Yeux sans visage True Best Movie: Judex

I'm really fond of Les Yeux sans visage. It's always mentioned as a classic and it's a well deserved honour. It's a beautiful way to turn a scary movie into strange emotions with a quiet pace. Besides that, the story around the movie making is great. No epic shooting. No earthquake, no tornado or actor going mental. Just the way Franju talks about the story itself. He's a great movie-making storyteller*.

Despite all that, Judex seems more important to me. First of all, the impulse to make a movie about a 1916 serial in the sixties and being serious about it is a really humble tribute. I love and respect that (if you've watched the somehow vintage funny sixties movies about Fantomas, you know what I mean). And now, the uppercut. No matter how strong you disagree with me regarding the best Franju movie, this scene from Judex ends any discussion (by the way, this music from Maurice Jarre is absolutely the best original motion picture soundtrack I've ever heard).

youtube

* If you speak french and are curious: among other things, consider reading the Oral History of Les yeux sans visage by Delphine Simon-Marsaud and published on the website of the Cinémathèque Française.

0 notes