#joseph-léonard poirey

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

24 Days of La Fayette: December 14th - Joseph-Léonard Poirey

Joseph-Léonard Poirey holds a special place on this list for several reasons. First of all, he was no aide-de-camp. Poirey was La Fayette’s military secretary in America and after the War of Independence worked as a civil secretary for him. Second, I am not known to call real, adult, historic people that are long dead by overly endearing names or to compare them with a certain baked good containing cinnamon – but if I every were to call a real, adult, historic person who is long dead, adorable, it would be Poirey. You will see why in a minute.

Poirey came into the service of La Fayette because he was the cheapest option. Let me elaborate and introduce you to a certain Jacques-Philippe Grattepain-Morizot. Morizot was an attorney and became the manager of La Fayette’s finances in 1779 together with Jean Grattepain. They took over from Jean Gerard. Handling La Fayette’s finances was not a fun thing to do, let me tell you. Between 1779 and 1782, Morizot wrote several letters to La Fayette’s maiden aunt Madeleine, who managed her nephew’s properties in the Auvergne, that the Marquis was spending too much and that he had broken his promise to economize. His adventures in America especially were giving Morizot headaches on a regular basis. After much urging on Morizot’s part, La Fayette came to the conclusion that apparently having a French secretary would be cheaper … as far as I understand the issue, this made little difference, not at all because the expenses for a single secretary were not the problem at all.

Anyway, back to Poirey. He was born in 1748 and joined the French Army in 1770. He was originally scheduled to join La Fayette on L’Hermione on her voyage to America but was so afflicted by seasickness and rheumatism that he was obliged to return to Paris. He would arrive on August 16, 1780 in Boston onboard the Alliance. Major Charles-Albert de Moré, chevalier de Pontgibaud (another aide-de-camp for a later day), and Capt. Louis-Saint-Ange Morel, chevalier de La Colombe (an aide-de-camp as well) accompanied him as well as twelve other passengers.

La Fayette’s was not necessarily happy with the three men, Poirey included, because these gentleman had letter for La Fayette and they were not nearly hurrying as much as La Fayette would have liked it. He wrote to the Vicomte de Noailles on September 2, 1780:

We are tired of the whole thing, my friend. I have cursed about M. de Pontgibaud so much that I do not know what more to say, and I am stupefied by this miracle of negligence. Eighteen days to come from Boston! The only way to explain the enigma is that Poirey is with him, which I have learned from the gazette (because Poirey has been given full coverage in the papers), and Poirey stops at every wonder he sees here. I cannot tell you how much this delay distresses me. There are a thousand things apart from the public service that I would like to know; but I promise you at least that if I have any news I will not delay in sharing it with you.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 3, April 27, 1780–March 29, 1781, Cornell University Press, 1980, p. 156-159.

La Fayette again wrote on September 3, 1780, this time to the Prince de Poix:

The Alliance has arrived and brought me letters; I know they are in Boston, and the officer who carries them calmly entertains himself buying horses. Good God, if he did not have my packet in his pocket, how much bad luck I would wish him! This accursed man, M. de Pontgibaud, flanked by M. de La Colombe and friend Poirey, set foot on land almost three weeks ago. He said he had important dispatches to deliver to me, so important that he refused to confide a single letter to an officer of the French army who was returning to Rhode Island, and apparently he thinks they are too important to travel other than by easy stages. Meanwhile I am getting angry, and increasingly so as I see how useless it is. Only think, my friend, that the last letters from France were brought by M. de Ternay and since then not a word from my friends. If our neighbors in New York were a little further separated from us than they are by the river, I would have run after my letters a long time ago. But, my friend, I realize it is stupid to send you lamentations when the reason for them will be gone two or three months before my jeremiad is received; so let's talk about other things, because in order to relieve my ill humor and forget those worthless bogged-down couriers I absolutely must scribble you a few lines, and while Washington holds back General Clinton I shall tell you the big news, which is that I am fine and I love you with all my heart.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 3, April 27, 1780–March 29, 1781, Cornell University Press, 1980, p. 164-167.

As soon as Poirey truly entered La Fayette’s service, the young General was very pleased. He wrote to his wife Adrienne on October 7-10, 1780:

Poirey is with me, seems quite happy, is astounded at everything, and has not yet been under fire but thinks that war is a fine thing. I am infinitely satisfied with him, and also with Comtois [a servant]. M. Morizot will be well enough satisfied with me, at least by comparison.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 3, April 27, 1780–March 29, 1781, Cornell University Press, 1980, p. 193-197.

(Spoilers ahead: Morizot was not at all satisfied.)

Poirey served La Fayette in 1780 and 1781 and was most of the time with the General in Virginia. It was also there that he saw action for apparently the first time – and by all accounts, Poirey enjoyed himself. La Fayette wrote to the Vicomte de Noailles on July 9, 1781:

This devil Cornwallis is much wiser than the other generals with whom I have dealt. He inspires me with a sincere fear, and his name has greatly troubled my sleep. This campaign is a good school for me. God grant that the public does not pay for my lessons. Poirey behaved intrepidly, and I assure you he had a very lively time.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 4, April 1, 1781–December 23, 1781, Cornell University Press, 1981, p. 240-241.

The Virginia campaign proofed strenuous, and it became clear that Poirey had not been blessed with the most robust health. La Fayette wrote on August 24, 1781 to his wife Adrienne:

The Virginia sun has a very bad reputation, and people had made frightful predictions to me. In fact many people have had fever, but this climate is as good as every other for me, and the only effect fatigue has had on me is to increase my appetite. (It is not the same with poor Poirey, and for some time he has been afflicted with a fever that does not permit him to follow me. He has been infinitely useful to me, and I am more and more pleased with him. So, my dearest, I must thank you again for your good idea. It may not have been exalted to the point of making me think you were giving me a Caesar for courage. But I do not joke, my dear heart, and if you had seen Poirey on the sixth of July, with a portfolio on the front of his saddle, a portfolio behind, a large writing desk hanging on his left side, and in his right hand a saber that once belonged to General Arnold; if you had seen Poirey, I say, smiling at the bullets and balls that whistled by in great numbers, you would have judged that he shines on the Field of Mars just as much as in the scene where one puts a rose-colored ribbon around his neck.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 4, April 1, 1781–December 23, 1781, Cornell University Press, 1981, p. 342-345.

Poirey returned after the Battle of Yorktown to France. He sailed once more on the Alliance on company of Louis-Saint-Ange Morel de La Colombe and they arrived in France in January of 1782. He soon began working for La Fayette in a civilian capacity … and La Fayette was as happy as a man can be. He wrote Adrienne regarding Poirey when he himself was again back in America on June 25, 1784:

Give my regards to Gouvion and Poirey. Under certain circumstances I would be very glad if the latter joined me, because besides having the pleasure of very detailed news through him, I would find him very useful.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 5, January 4, 1782‑December 29, 1785, Cornell University Press, 1983, p. 229-230.

There was no way that Poirey could join La Fayette – for he was once again ill. La Fayette wrote Adrienne on October 4-10, 1784:

I am quite distressed that poor Poirey has a nervous disorder, but if he is better, persuade him to learn to write in abbreviations, as quickly as a person speaks, and to have my library arranged.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 5, January 4, 1782‑December 29, 1785, Cornell University Press, 1983, p. 260-262.

Poirey had agreed to serve in America without pay, just like La Fayette did, and this decision later came back to bite during the French Revolution. Initially things seemed to look well for Poirey, he became the captain secretary general of the National Guard with the rank of major. The La Fayette’s had lobbied for him to be made an American officer and an honorary member of the society of the Cincinnati. Adrienne wrote to George Washington on January 14, 1790:

Mr Poirey the secretary of Mr De la Fayette and who is at present that of our national guard, loaded with kindness by you in America where he has had the happiness of meriting your approbation has not ceased since that time, to give to Mr De la Fayette testimonies of attachment, and he has rendered to this cause important services and above all very affecting to him. His ambition is to obtain the glorious distinction of an American Officer, the Ribbon of Cincinnatus is the object of all his wishes, and Mr De la Fayette would think he could not refuse him the permission, if you would deign to confer upon him, a brevet commission. I set a great value upon obtaining for him this favour, and it would be to me a great pleasure if I owe it to your goodness for me, I should recieve almost as much pride as gratitude from it, ⟨and⟩ that it would be the means of acquitting a little what we owe to Mr Poirey, and which I believe due to him more than to any other person, persuaded as I am, that his vigilant cares have contributed very much in the midst of the Storms to the preservation of what I hold most dear in the world. Mr De la Fayette approves my request, and will leave to me I hope the pleasure and the glory of having obtained the success of it from you Sir, and of joining on this little occasion the hommage of my personal gratitude, to that of all his sentiments of admiration, attachment and respect, which I participate with him (…)

“To George Washington from the Marquise de Lafayette, 14 January 1790,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 4, 8 September 1789 – 15 January 1790, ed. Dorothy Twohig. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993, pp. 571–574.] (10/07/2022)

George Washington wrote to the United States Senate on May 30, 1790:

M. de Poiery served in the American Army for several of the last years of the late war, as Secretary to Major General the Marquis de la Fayette, and might probably at that time have obtained the Commission of Captain from Congress upon application to that Body. At present he is an officer in the French National Guards, and solicits a Brevet Commission from the United States of America. I am authorised to add, that, while the compliance will involve no expense on our part, it will be particularly grateful to that friend of America, the Marquis de la Fayette.

I therefore nominate M. de Poiery to be a Captain by Brevet.

“From George Washington to the United States Senate, 31 May 1790,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 5, 16 January 1790 – 30 June 1790, ed. Dorothy Twohig, Mark A. Mastromarino, and Jack D. Warren. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1996, pp. 446–447.] (10/07/2022)

The nomination was confirmed on June 2, 1790 and Washington replied to Adrienne on June 3, 1790:

It gives me infinite pleasure, in acknowledging the receipt of your letter of the 14th of Jany last, to transmit the Brevet Commission, that was desired for Mr Poirey. Aside of his services in America, which alone might have entitled him to this distinction, his attachment to the Marquis de la Fayette and your protection added claims that were not to be resisted. And you will, I dare flatter myself, do me the justice to believe that I can never be more happy than in according marks of attention to so good a friend to America and so excellent a patriot as Madame la Marquise de la Fayette.

Endnotes of “To George Washington from the Marquise de Lafayette, 14 January 1790,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 4, 8 September 1789 – 15 January 1790, ed. Dorothy Twohig. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993, pp. 571–574.] (10/07/2022)

Poirey was very happy about the kindness bestowed upon him. He wrote to Washington on February 8, 1791:

M. de De la Fayette m’a remis le Brevet de Capitaine au service des Etats-unis d’amérique que vous avez eu la bonté de lui envoyer pour moi: permettez-moi de vous en faire mes remerciements et de mettre à vos pieds l’homage de ma Reconnoissance et du Respet avec lesquels je suis de Votre Excellence le tres humble et tres obeissant serviteur.

“To George Washington from Joseph-Léonard Poirey, 8 February 1791,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 7, 1 December 1790 – 21 March 1791, ed. Jack D. Warren, Jr. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998, p. 323.] (10/07/2022)

My translation:

M. de la Fayette gave me the Certificate of Captain in the service of the United States of America which you were kind enough to send to him for me: allow me to express my thanks to you and lay at your feet the homage of my gratitude and respect with which I am Your Excellency's very humble and very obedient servant.

La Fayette later reported to Washington on March 7, 1791:

You Have Made Mr Poirey the Happiest Man in the World for which Mde de Lafayette and Myself are Very thankfull.

“To George Washington from Lafayette, 7 March 1791,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 7, 1 December 1790 – 21 March 1791, ed. Jack D. Warren, Jr. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998, pp. 518–521.] (10/07/2022)

The Revolution, after 1792, was not kind at all to Joseph-Léonard Poirey. He was not imprisoned alongside La Fayette, to my knowledge, he never left the country, but I sadly have no greater detail on Poirey’s whereabouts during the Revolution. But by 1796 he and his family had hit a bottom low and Poirey felt himself forced to seek compensation from America for his unpaid service. He wrote to George Washington on May 12, 1796 after having sent a previous letter and an official petition in April of 1796:

(…) Without hope of advancement in my own Country, destitute of resources, and of fortune; permit me to ask your support, and to beg you to do with Congress, that which the General would, were he near you. I am indebted to your goodness for my official Brevet and admission into the Cincinnati. These honorable marks lead me to address myself to Congress. It is you, my General who can render homage to the truth, and who can ask of them for me that which would have been allowed me on my departure from america, and which modesty prevented me from soliciting of them.

Endnotes of “To George Washington from Joseph-Léonard Poirey, 27 February 1793,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 12, 16 January 1793 – 31 May 1793, ed. Christine Sternberg Patrick and John C. Pinheiro. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2005, pp. 229–230.] (10/07/2022)

The petition was laid before the Congress and was debated over several days in a “Committee of the Whole”. Both James Madison as well as then-Secretary of War James McHenry (another one of La Fayette’s aide-de-camps that we will be covering in his series) were deeply invested in Poirey’s cause. Richard Peters had written to Madison on February 4, 1796 and given him (and us) some more background information:

This young Man never had a Commission tho’ he did the Duty he mentions. He came to this Country & left it with the Marquis. The Facts he states can be ascertained by those he refers to. If you think it necessary Mr Ternant will call on you. Monsr Poiret is a Citizen of the present Republic of France. He lives at Paris & maintains a Wife & 2 or 3 Children by the Labour of his Hands. I believe he is a Writer in some Office but whether public or private I know not. At any Rate he is poor & deserving a better Situation.

“To James Madison from Richard Peters, 4 February 1796,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of James Madison, vol. 16, 27 April 1795 – 27 March 1797, ed. J. C. A. Stagg, Thomas A. Mason, and Jeanne K. Sisson. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1989, p. 212.] (10/07/2022)

Despite appearing to agree on the matter, it took Congress until the year 1819 to pay Poirey a compensation of $3,486. The House of Representatives passed the bill first on January 15 and the Senate passed the bill on February 17. Part of the problem seemed to be, that the statute of limitation had expired and that any move from Congress would solely be a gesture of goodwill. It was feared that Poirey’s treatment could create a precedent. One notable opponent of Poirey’s was Henry Dearborn. Poirey’s exemplary service and his close ties to La Fayette won Congress over in the end. Madison made two strong comments on the matter in Congress on January 9 and 11, 1796:

Messrs. Madison (…) supported the cause of M. Poira. They urged it as a singular case. It was asserted that M. La Fayette, and his family, were the only persons who had served in the war, with a previous profession that they would receive no pay. They denied that it was a claim of Justice; in that case, they allowed the statute of limitation would have barred it: It was a claim upon the equity and generosity of the nation. This gentleman, like his master, they said, had been overtaken by misfortune, and to refuse to afford him that relief which Justice must have paid him had he asked it at an earlier day, would be derogatory to the honour of the nation.

“Petition of Joseph-Léonard Poirey, [9 January] 1797,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of James Madison, vol. 16, 27 April 1795 – 27 March 1797, ed. J. C. A. Stagg, Thomas A. Mason, and Jeanne K. Sisson. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1989, pp. 451–452.] (10/07/2022)

Mr. Madison observed, that if he saw any danger from the precedent of making this provision, he should not be for it; but he believed the precedent could not be extended to any other case. This officer, he had learnt, would have been put on the foreign list, had it not been that he was so wrapped up in the conduct of his general, as to consider it indelicate to receive any payment. He relied upon the prosperous fortune of general La Fayette for recompense. This had failed him. If, said Mr. M. any thing could afford comfort to the general in his present unfortunate confinement, it would doubtless be to find that the United States had extended their liberality to the relief of his faithful servant.

“Petition of Joseph-Léonard Poirey, [11 January] 1797,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of James Madison, vol. 16, 27 April 1795 – 27 March 1797, ed. J. C. A. Stagg, Thomas A. Mason, and Jeanne K. Sisson. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1989, pp. 453–454.] (10/07/2022)

Madison’s second comment especially is interesting, for it shows us that Poirey and his family must have fallen on hard times before the La Fayette’s did, if he had previously been recompensated by them. By 1819, Thomas Jefferson had also invested himself in the case and it was he who could finally related the good news to Poirey on March 8, 1819:

I am happy in being able at length to send you a copy of the act of Congress authorising the compensation of your services which has been so long detained. you may on probable appearances suppose that a part of this delay has flowed from me. but it is not so. the office of Secretary at war was vacant a whole twelvemonth, and I knew it would only defeat your claim to let it be brought forward by a head-clerk, acting par interim. the present Secretary at war came into office on the rising of Congress so that he could not propose it till they met again for the following year. it was then presented, but as they never get thro half the bills before them, this laid over another year, and at their last meeting has got thro’. thus has this claim been unavoidably delayed three years. I presume it will now be necessary for you to state your account, get it certified by M. de la Fayette, and to send it to some person at Washington with a power of attorney regularly legalised according to the forms of your laws. perhaps some member of your diplomatic mission here. I am sorry I cannot offer you my services, but besides that my distance would occasion delay, the hand of age is pressing heavily on me, and the right wrist, which I dislocated at Paris, is become so stiff as to make writing a slow and painful business, & has obliged me to discontinue nearly all correspondence. but if you have no other resource, and will inclose to me a blank power of Attorney, I will fill the blank with the name of a faithful and attentive agent who will recieve & remit you the money. your papers are in the war office & I will see that they are safely returned to you. I salute you with great esteem & respect.

“Thomas Jefferson to Joseph Léonard Poirey, 8 March 1819,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Retirement Series, vol. 14, 1 February to 31 August 1819, ed. J. Jefferson Looney. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017, pp. 110–111.] (10/07/2022)

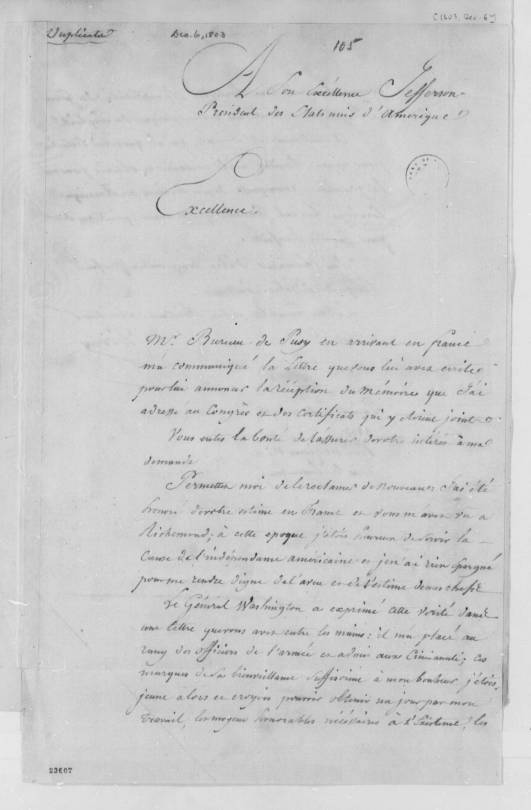

And last but certainly not least, yes, we do have a handwriting sample from Poirey – I am glad you asked. :-) Here is a short letter form Poirey to Thomas Jefferson on December 6, 1803:

Joseph Poirey to Thomas Jefferson, December 6, in French. -12-06, 1803. Manuscript/Mixed Material. Retrieved from the Library of Congress. (10/19/2022)

#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#american history#american revolution#french revolution#history#letter#24 days of la fayette#lafayette's aide-de-camps#adrienne de lafayette#adrienne de noailles#james madison#george washington#thomas jefferson#james mchenry#joseph-léonard poirey#1780#1781#1748#1770#1790#1819#1779#1782#1784#1791#1792#founders online#madeleine du motier

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Death of Cromwell

Something terrible has happened, Adrienne knows as a bleary-eyed maid wakes her in the morning. The sun has only just begun to rise. The maid tells her that there is a man waiting. Joseph-Léonard Poirey, her husband’s secretary with the National Guard. As Adrienne hastily dresses and hurries downstairs into the hall, she sees Poirey standing there. The face red and the hair disheveled. He has the appearance of a men who is the bearer of grave news.

As soon as Poirey sees her on top of the stairs, he bows and deeply and tries to regain some measure of control, his fingers are trembling as he smooths over his coat. Something terrible has happened, Adrienne thinks as she leads Poirey into the salon. Dread churns in her stomach. Dear God, please no! She begs Poirey to sit down as she does the same. Her hands are folded in her lap to keep them from trembling. She does not ask Poirey if he wishes any refreshments – quite unbecoming of a hostess, her husband would have scolded her for this oversight, but she can not bring herself to care at the moment. Not when she feels like her life hangs in a terrible, dreadful balance.

Poirey clears his throat as he searches for the right words. “Madame, I fear that I have solemn news for you. Your husband … your husband Madame is dead.”

Adrienne stares at her guest, her fingers fiddle with the hem of her dress. She dares not to breath, not to think, not to move. For a moment, the world has stopped. This is a dream, a terrible, terrible nightmare, she thinks. I have to wake up and when I do, Gilbert will lay in bed beside me, hale and healthy! But Adrienne does not wake up for this is no dream. She just sits there, in a chair in her salon with Poirey right next to her and she can do nothing while her worlds shatters around her.

Poirey clears his throat as he rises. “I best take my leave now Madame, but please, if there is anything that I can do for you, never hesitate to send for me.” Adrienne watches him cross the room and heads for the door before she finds her voice again. “How?”, she asks, her voice hoarse.

“Pardon?”

“How did my husband die?”

“Madame, I do not know if you should-“

“How did my husband, the father of my children, die, Monsieur Poirey?”

“He was murdered in his sleep”, Poirey finally tells her, his voice sounds defeated.

For a moment, Adrienne is unable to breath, as if there is no air left in the room. Murdered in his sleep? Who would do such a cowardly and dishonorable thing? As if reading her thoughts, Poirey continues. “Your husband led his National Guard and a few thousand civilians to Versailles. All in all, the scene was very orderly, but some members of the court disliked the orders the General gave. To assure the safety of the royal family, he assumed command over the Kings Gards-du-corps and placed the National Guard inside the palace. Some people thought him a usurper who was only waiting for the right moment to overthrow the king and crown himself. Utter nonsense, of course, but people who live in fear are seldomly rational. Your husband retired to bed after all affairs had been settled. He was exhausted to the bone, I doubt he was even woken by the assassins entering his chambers.” Poirey pauses for a moment as if unsure how to say his next words. “He was found dead in his bed the next morning. He had been stabbed … 23 times in his sleep. The National Guard arrested two possible culprits, but they were lynched before they could make a statement. It was a bloody morning, and the court has completely alienated himself to the soldiers – not just the ones of the National Guard.”

Poirey lingers for a few more minutes after he finished his report before he finally bows and takes his leave. Adrienne hardly realizes his departure. She can only sit there and try her best to comprehend the incomprehensible. The house awakes around her, and she hears the noises of the servants preparing for the day. She hears the sound of tiny feet running around on the floor above her.

*fin*

Historical Context:

Members of the court taking such drastic actions is certainly a more alternative scenario but La Fayette himself predicted in his Memoirs, that if he had assumed more command or stationed the national Guard in the palace, he would have been seen as a usurper.

When we enter fully into the state of things and of feelings at that period, and especially on that evening, we shall easily perceive, that if Lafayette had required that his troops should be placed in the palace, that if he had himself assumed the command of the gardes-du-corps, he could only have accomplished his aim by employing force; he must have made an irruption like the brigands, instead of being a guardian, he would have become an usurper.

Marquis de La Fayette, Memoirs, Correspondences and Manuscripts of General Lafayette, Vol. 2, Craighead and Allen, New York, 1837, pp. 325-326.

At night he was alone, unarmed, and unguarded in the apartment of his wife’s family. Killing him then and there would have been an option for someone desperate enough. The court was generally in disfavor of him and in this scenario his orders only widened the rift between himself and the court.

#there is cromwell#choose your own adventure#alternate history#history#french history#french revolution#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#1789#adrienne de noailles#adrienne de lafayette#march of the women on versailles

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

24 Days of La Fayette 2022 - La Fayette's aide-de-camps

Day 1 - Edmund Brice • Day 2 - Louis Cloquet de Vrigny • Day 3 - Pierre, Chevalier Du Rousseau de Fayolle • Day 4 - Louis-Pierre, Marquis de Vienne • Day 5 - John E. Hagey • Day 6 - Carter Page • Day 7 - Cadwallader Jones • Day 8 - William Constable • Day 9 - Comte de Charlus • Day 10 - George Augustine Washington • Day 11 - Jean-Louis and Alexandre Romeuf • Day 12 - André Toussaint Delarûe • Day 13 - Gabriel de Queyssat • Day 14 - Joseph-Léonard Poirey • Day 15 - William Langborn • Day 16 - François-Louis Teissèdre de Fleury, Marquis de Fleury • Day 17 - Joseph-Pierre-Charles, Baron de Frey • Day 18 - Charles-Albert, comte de Moré de Pontgibaud • Day 19 - Jean-Joseph Soubadère de Gimat • Day 20 - Louis-Saint-Ange, chevalier Morel de La Colombe • Day 21 - Michel Capitaine du Chesnoy • Day 22 - Jean-Baptiste, Chevalier de Gouvion • Day 23 - Presley Neville • Day 24 - James McHenry

#24 days of la fayette#la fayette's aide de camps#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#american history#american revolution#history#resources#master post

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have cursed about M. de Pontgibaud so much that I do not know what more to say, and I am stupefied by this miracle of negligence. Eighteen days to come from Boston! The only way to explain the enigma is that Poirey is with him, which I have learned from the gazette (because Poirey has been given full coverage in the papers), and Poirey stops at every wonder he sees here.

The Marquis de La Fayette to the Vicomte de Noailles, septembre 2, 1780

Charles-Albert de More de Pontgibaud and Joseph-Léonard Poirey were two of La Fayette’s aide-de-camps and had recently returned form France with mail for La Fayette. They sadly were not hurrying as much as La Fayette would have liked it.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 3, April 27, 1780–March 29, 1781, Cornell University Press, 1980, p. 156-159.

#quotes#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#american history#american revolution#history#letter#1780#vicomte de noailles#charles-albert de more de pontgiband#joseph-léonard poirey

6 notes

·

View notes