#john lewis krimmel

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

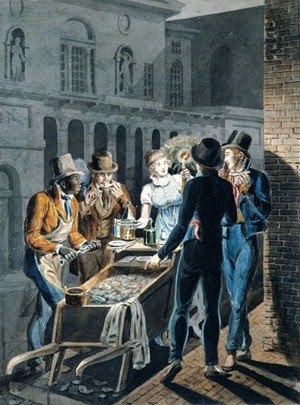

Nightlife in Philadelphia - An Oyster Barrow in front of the Chestnut Street Theater painted by John Lewis Krimmel (1786 - 1821)

#art#art history#artwork#culture#curators#history#museums#painting#vintage#romanticism#john lewis krimmel

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Village Politicians by Krimmel, John Lewis 1786-1821

0 notes

Text

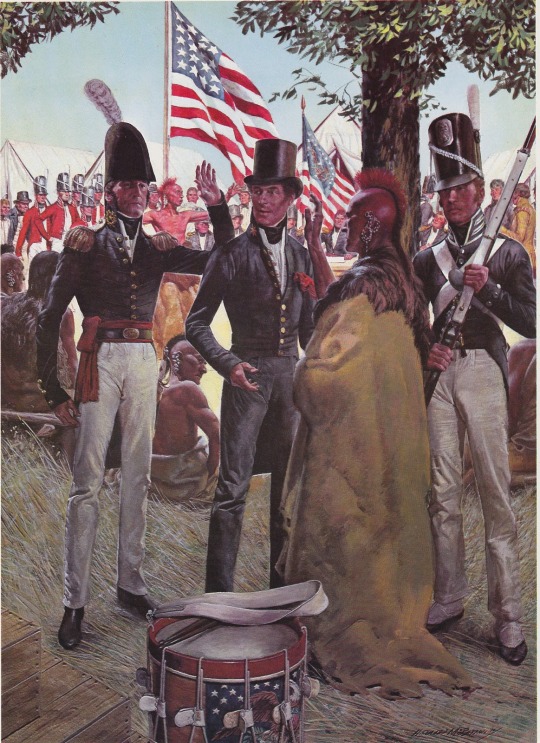

A piece by H. Charles McBarron Jr. titled THE AMERICAN SOLDIER, 1819: Engineer Officer, U.S. Explorer, Infantryman, Infantry Bandsmen, Indian Commissioners.

This was made in the 1960s-1970s, but what I really love about it is how much it echoes an 1819 painting of Independence Day Celebration in Centre Square, Philadelphia, by John Lewis Krimmel.

Tell me that McBarron wasn't referencing War of 1812 Boyfriends, at centre:

#h charles mcbarron jr#military history#uniforms#us army#us history#john lewis krimmel#1810s#1819#dressed to kill#mcbarron gives every man a period-appropriate cinched waist look#and i love him for it#the american soldier#historical men's fashion#i want to pretend it's the same guys in both paintings#why did we as a society move away from cool hats

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nightlife in Philadelphia—an Oyster Barrow in front of the Chestnut Street Theater by John Lewis Krimmel https://twitter.com/met_ampainting/status/1182683394871889925

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sunday Morning in front of the Arch Street Meeting House, Philadelphia, John Lewis Krimmel, 1811–ca. 1813, American Paintings and Sculpture

Rogers Fund, 1942 Size: 9 x 7 3/8 in. (22.9 x 18.7 cm) Medium: Watercolor, black ink, and graphite on white laid paper

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/12749

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Conflagration of the Masonic Hall, Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Samuel Jones, 1819, Art Institute of Chicago: American Art

On March 9, 1819, Masonic Hall, built just 8 years earlier, burned to the ground. A Philadelphia publisher commissioned artists Samuel Jones and John Lewis Krimmel to create a composition of the fire’s devastation for distribution as a print (etched by John Hill). Circulation of such sensational events was an early 19th-century means of broadcasting news, expanding the reach of fine arts, and making a profit. Jones painted this work, which served as a study for the print. Krimmel, the nation’s first great genre painter, was hired to refine and amplify the figural scene in the foreground. As the print’s composition reveals significant changes to the figures, it is unknown if Krimmel executed any of the figures here, or if he developed his designs wholly apart from this painting. Restricted gift of Wesley M. Dixon Jr., Jamee J. and Marshall Field, Gloria and Richard Manney, Brooks and Hope B. McCormick Foundation, Mrs. Philip D. Sang, and Jeffrey Shedd; gift of Emily Crane Chadbourne, Leon Mandel, Stella Manheimer, Vena F. Schaaf, and Celia Schmidt by exchange; the Edward E. Ayer, Marian and Samuel Klasstorner, and A.A. McKay funds Size: 48.4 × 60 cm (19 1/6 × 22 1/6 in.) Medium: Oil on mahogany panel

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/111295/

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pepper-Pot: A Scene in the Philadelphia Market, 1811

John Lewis Krimmel (1786-1821). Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Reminds me of a scene in episode 3 of “High on the Hog” on netflix

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

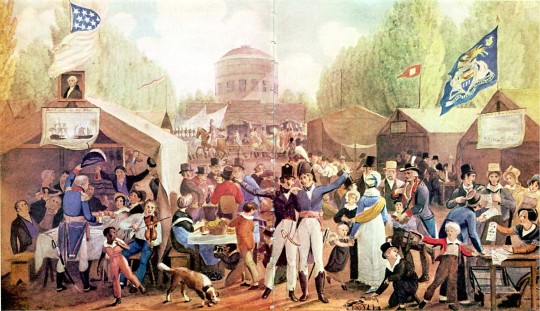

The 4th of July, the sixty-first anniversary of American independence!

Pop—pop—bang— pop—pop—bang—bang bang! Mercy on us! how fortunate it is that anniversaries come only once a year. Well, the Americans may have great reason to be proud of this day, and of the deeds of their forefathers, but why do they get so confoundedly drunk? why, on this day of independence, should they become so dependent upon posts and rails for support? The day is at last over; my head aches, but there will be many more aching heads tomorrow morning!

What a combination of vowels and consonants have been put together! what strings of tropes, metaphors, and allegories, have been used on this day! what varieties and gradations of eloquence! There are at least fifty thousand cities, towns, villages, and hamlets, spread over the surface of America—in each the Declaration of Independence has been read; in all one, and in some two or three, orations have been delivered, with as much gunpowder in them as in the squibs and crackers. But let me describe what I actually saw.

The commemoration commenced, if the day did not, on the evening of the 3rd, by the municipal police going round and pasting up placards, informing the citizens of New York, that all persons letting off fireworks would be taken into custody, which notice was immediately followed up by the little boys proving their independence of the authorities, by letting off squibs, crackers, and bombs; and cannons, made out of shin bones, which flew in the face of every passenger, in the exact ratio that the little boys flew in the face of the authorities. This continued the whole night, and thus was ushered in the great and glorious day, illumined by a bright and glaring sun (as if bespoken on purpose by the mayor and corporation), with the thermometer at 90 degrees in the shade.

— Frederick Marryat witnessing the 4th of July in Diary in America (1837)

image: Independence Day Celebration in Centre Square, Philadelphia, by John Lewis Krimmel, 1819.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#4th of july#american independence day#diary in america#1830s#1837#the more things change...#fireworks

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blind Man's Bluff painted by John Lewis Krimmel (1786 - 1821)

#art#art history#artwork#culture#curators#history#museums#painting#vintage#romanticism#john lewis krimmel

103 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Election Day is here! This print from an unfinished plate by Philadelphia engraver Alexander Lawson depicts a chaotic scene in front of the State House on Chestnut Street during a city election. The scene depicts voters arriving, completing and switching ballots, and blocking the polls as politicians and campaigners, including former mayor John Barker, lobby for votes and engage in debate.

Alexander Lawson after a painting by John Lewis Krimmel, The election day in Philadelphia, ca. 1894. Engraving.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1812-1819 by John Lewis Krimmel US

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fourth of July in [Philadelphia’s] Centre Square (1812)

by John Lewis Krimmel.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

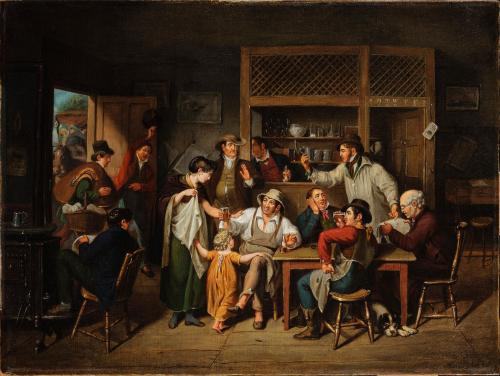

The Extraordinary Ordinaries of Colonial Dumfries

The Extraordinary Ordinaries of Colonial Dumfries

By: Emma Tainter

Emma Tainter is a current M.Phil of Public History and Cultural Heritage student at Trinity College Dublin. Emma grew up in the Dumfries area and is thrilled to be able to help share its history and that of the Weems-Botts Museum, which is also the first museum she volunteered at.

When a constructing a town, there are many things one must take into consideration. Where will the main road be? Where will people live? Where will the courthouse be built? And lastly, where will the people eat, drink, and generally be merry?

The answer to the last question lies within Colonial Dumfries’ many ordinaries – or what today we would refer to as a tavern, bar, or inn. Ordinaries served a multifaceted and vitally important role in the social fabric of a colonial town.

The establishment of ordinaries was a constructed effort on the part of the local government to sow a reputation for hospitality – a crucial ingredient for a reputable town. Before the court would enter into a bond (or an agreement) with a potential ordinary owner, the owner had to prove that they could financially support a welcoming space for locals and travelers alike. Although courts issued a majority of the ordinary licenses in Dumfries in men during the 18th century, it was not uncommon for women to own and operate their own ordinaries.

While ordinaries could be built as standalone buildings, some of them were attached to the owner’s home. It seems the popular choice in Dumfries was to operate an ordinary attached to your home; between 1783 and 1784, Dumfries residents John Chick, William Lynn, William Tyler, Catherine Blancett, John Shute, Susanna Franklin, Joshua Baker, William Skinner were all granted licenses to keep an ordinary or tavern at their house. [1]

Either way, the ordinaries had to follow strict rules in terms of their rates for accommodation, food, and beverages in addition to keeping a tidy and clean space. Ordinary owners took pride in their businesses, as we can see from William Tebbs’ advertisement from April 1785:

Virginia Journal & Alexandria Advertiser 14 Apr 1785

THE SUBSCRIBER begs leave to inform the public that he has opened a Tavern, in the house lately occupied by Miss Susanna Franklin, in the town of Dumfries, where he is accommodated with every thing requisite for the regularly keeping a genteel house. Those gentlemen who [would] please to favor him with their custom may be assured that every exertion in his power shall be used in order to render them the most agreeable satisfaction, and such favors be gratefully acknowledged, by their most humble servant.

The Ordinaries became an extension of a person’s home into the community, and a place of community itself. It was in ordinaries where the townsfolk gathered to exchange business dealings, enjoy a meal, and most importantly, catch up on the gossip.

If you wanted to hear the latest court proceedings, you could head down to an ordinary to chat with your neighbors, or you may even be lucky enough to sit next to a witness who was waiting to be called to the stand – as the ordinaries were often filled with “witnesses waiting to be heard” in hearings in the neighboring courthouse.[2] If you happened to stop by Mitchell’s Tavern on November 7th, 1796, you would have bumped into a meeting of the Overseers of the Poor, where of Thomas Lee, John McMillion, Alexander Bruce, Philip Dawe, and Thomas Harrison met to discuss various accounts.[3]

A depiction of a lively American tavern. Krimmel, John Lewis. (1813-1814) Oil on canvas. Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, OH.

The outside of the ordinary was often full of activity as well. It was common for people to hold auctions on the doorstep of ordinaries for the sale of land, property, and enslaved persons. The central locations of the ordinaries, as well as its already established usage as a gathering place, made it a sensible place for those wanting to buy or sell. The Virginia Journal & Alexandria Advertiser is full of advertisements such as the one below posted in February 1785:

TO BE SOLD on Monday the 7th of March next, before Mr. William McDaniel's Door, in the town of Dumfries, TWELVE SLAVES, belonging to the personal estate of the Rev. James Scott, deceased, consisting of Men, Women, and Children; and on Friday in the same week at Westwood, in Prince William County, the remainder of the Household Furniture, belonging to the said estate, consisting of tables, chairs, bedspreads, one bed and furniture, a neat pier glass, and other articles too tedious to enumerate. Credit will be allowed for all sums exceeding Forty Shillings for 12 months, the purchasers giving bond and approved security to bear interest from the date, if not punctually paid.

T. Blackburn, Administrator.[4]

Newspapers of the era, such as the Virginia Journal & Alexandria Advertiser and the Virginia Gazette & Agricultural Repository served as bulletin boards for these auctions and continue to be a great source of information about the inhabitants of 18th century Dumfries. Those newspapers mention the ordinaries of Mr. Tebbs, Mr. Mitchell, Mr. Smock, but the one that current Dumfries’ residents might be most familiar with is Mr. William McDaniel’s ordinary, or the Williams Ordinary. Later owned by George Williams, Williams Ordinary is still standing on Main Street, and today houses the Prince William County Office of Historic Preservation. Williams Ordinary hosted many famous figures during its heyday, including Thomas Jefferson, the Comte de Rochambeau, the Marquis de Lafayette, and George Washington.[5]

The reputation of an ordinary varied: while one could be known as the local meeting house of the Overseers of the Poor, another could be associated with more nefarious dealings. While people filled the ordinaries during the day and evening, the night could draw a very different (and perhaps a much rowdier crowd). Ordinaries that were discovered allowing gambling and overindulging were quickly reprimanded by the courts; a lesson Hugh Guttray learned the hard way. Just two months after opening an ordinary in his home, he was appealing his suspended license in court after he was found to be ‘permitting excessive gaming in his ordinary.’”[6]

The ordinaries all had different personalities and atmospheres. Some were known for their excellent food, such as the case of a woman who owned an ordinary attached to her home near the Bull Run Mountains. Her name is lost to history, but her food became legendary. So legendary, in fact, that George Washington himself is purported to have named a peak of the Bull Run Mountains in her honor. She was known to wear a leather apron and jacket all year round, and so the peak west of the Thoroughfare Gap became Mother Leathercoat Mountain.[7]

There are many things we can know for certain about Dumfries’ ordinaries, but the everyday conversations and meetings will have to be left to our imagination. Perhaps they weren’t so different than our own conversations today – something to ponder as we are able to venture into our modern-day ordinaries more and more.

Note: Thanks to Emma for the excellent research and interesting blog!

Enjoying our blog? Consider supporting us through memberships! Our memberships cost anywhere from $10-$30 for the entire year! From free tours & research to discounts on our popular programs, we have a lot to offer. Click here to learn more and here for our store.

[1] Prince William County, Virginia Court Orders 1783-1784. http://eservice.pwcgov.org/library/digitalLibrary/PDF/PWC%20Court%20Orders%201783-1784%20Final.pdf

[2] The Early History of Dumfries, Virginia. Carrol E. Morgan. April 21, 1994. 34.

[3] Records of Dettingen Parish.

[4] Prince William County Virginia 1784-1860 Newspaper Transcripts. Ronald Ray Turner. http://pwcvirginia.com/documents/PWC1784-1860NewspaperTranscripts.pdf

[5] Prince William: A Past to Preserve. 30-31.

[6] The Early History of Dumfries, Virginia. Carrol E. Morgan. April 21, 1994. 35.

[7] An Anthology of American Folktales and Legends. Frank Caro. 320.

(Sources: Morgan, Carrol E. 1994. “The Early History of Dumfries, Virginia.”; de Caro, Frank. 2015. An Anthology of American Folktales and Legends. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; Prince William County Virginia 1784-1860 Newspaper Transcripts. Ronald Ray Turner. http://pwcvirginia.com/documents/PWC1784-1860NewspaperTranscripts.pdfl; Wieder, L. C., ed. 1998. Prince William: a past to preserve. Prince William County Historical Commission.; Prince William County, Virginia Court Orders 1783-1784. RELIC: Prince William County Library System. http://eservice.pwcgov.org/library/digitalLibrary/PDF/PWC%20Court%20Orders%201783-1784%20Final.pdf; HDVI Archives: Records of Dettingen Parish PWC)

#localhistory#museumfromhome#taverns#virginiahistory#politics#townlife#primarysources#socialhistory#culturalhistory#enslaved

0 notes

Photo

Sunday Morning in front of the Arch Street Meeting House, Philadelphia by John Lewis Krimmel, American Paintings and Sculpture

Medium: Watercolor, black ink, and graphite on white laid paper

Rogers Fund, 1942 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/12749

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes