#jiken series

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Link

As a fan of SMT & its star artist Kazuma Kaneko, I was bound to stumble upon his other works of art including those done in collaboration with Kouhei Kadono of Boogiepop Phantom fame for an LN series I’d never heard of until a handful of years ago called the Jiken Mystery Series. It’s a meld of gritty Weird Fantasy with the Detective Fiction of Agatha Christie & hit right on my personal sweet spot not just due to loving unique fantasy settings like those of FromSoftware, SMT & Berserk but the likes of Hercule Poirot & Sherlock Holmes slotted into the MC role.

The Jiken Mystery Series sadly never even reached the niche cult status of its sister series Boogiepop Phantom so I’d abandoned hope of ever getting to read it beyond learning Japanese & scouring eBay for untranslated copies. However surprisingly, an LN fan happened across seemingly one of the few existing copies of the Del Rey Books English Translation of the 1st volume: The Case Of The Dragon Slayer: A Jiken Mystery from nearly 2 decades ago, an official publishing project that was soon after abandoned. That same fan also went through the effort of scanning the work & thanks to the magic of the Internet, an archivist went ahead & uploaded to the scans to the Internet Archive.

Despite the crude scans which don’t end up being flattering to Kaneko’s artwork, the story itself is still completely readable & enough so that a motivated fanbase could retype the entire thing & pair it with the existing higher quality versions of the novel’s artwork which have been floating around for a few years to create a digital restoration of at least this first book. It’s quite a wonder that this series, which was inching towards being complete lost media doomed to obscurity, has been able to persist at least a bit thanks to the random luck of a Kouhei Kadono reader & the efforts of online archivists.

#boogiepop phantom#boogiepop#the case of the dragon slayer#jiken mystery#jiken mystery series#jiken series#kouhei kadono#kadono kouhei#kazuma kaneko#kaneko kazuma#mystery novels#detective fiction#mystery fiction#fantasy fiction#light novel#light novels#agatha christie#internet archive#hercule poirot#lost media#smt#shin megami tensei#del rey#manga#dark fantasy#sherlock holmes#fromsoftware#crime fiction#japanese novel

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Then… we'll go with Toshiki. Isn't that too normal?

OKURA: MEIKYU IRI JIKEN SOSA オクラ〜迷宮入り事件捜査〜 2024, Okamoto Shingo, Ishii Yasuharu, Komaki Sakura.

#okura: meikyu iri jiken sosa#okura: cold case investigation#オクラ〜迷宮入り事件捜査〜#series#jdrama#sugino yosuke#sorimachi takashi#jdramaedit#jflowgifs#*#okura: 1.05#call him トシちゃん it's what he deserves

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Yuma kokohead from master detective archives. his weak build is unsuited for physical confrontation. his only superpower requires the consent of other people with superpowers to use. he has amnesia but vaguely remembers how to use a gun

Tribute Name: Yuma Kokohead

Age: Appears Teenage (if anyone can confirm or debunk this please let me know)

Restrictions: No use of the Coalescence power (the ability to share someone else's ability) and no assistance from Shinigami

If you would like to see a character aged 12-18 enter the Hunger Games, submit them through my asks. If you would like to see a character aged 19+ act as a mentor, submit them through this Google Form. The most popular of the 19+ characters will be posted every Saturday.

#cantheywinthehungergames#hunger games#the hunger games#thg#thg series#master detective archives: rain code#master detectives archives#cho tantei jiken bo raincode#cho tantei jiken-bo raincode#spike chunsoft#yuma kokohead#rain code#video games#video game#gaming#videogame#poll

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ohh I found a new arthurian anime!!

Ai to Ken no Camelot: Mangaka Marina Time Slip Jiken

You can watch it here with eng sub

The title means: "Marina the Manga Artist Goes to Camelot" and it is a one episode (OVA) from 1990. It seems to come from a light novel.

This is the plot from Animelist:

Self-described "third-rate" mangaka Ikeda Marina is attending a birthday party for a wealthy friend, when suddenly a time-traveling dragon whisks the entire party away to Camelot in sixth-century Britain. There, Marina must help would-be king Arthur fend off civil war by extracting the sword Excalibur from its stone during the forthcoming solar eclipse. But the evil Lady Dola intends to thwart this plan and seize Camelot for herself...

The light novel by the same title is this: Camelot of Love and Swords - Manga House Marina Time Slip Incident (Shueisha Bunko - Cobalt Series) Paperback Bunko – June 1, 1990 by Hitomi Fujimoto (Author), Amu Taniguchi (Illustrator).

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Todorokis, how they are called and how they call others - Part 1 (Chap. 1-21 & Ep. 1-13)

So I've already an "How the Todorokis call each other" series in 4 parts. This is a little different as in this I'll go though the manga in chronological order and look at how the Todorokis call each others, the other people and how they're called back.

This means you'll find bits of the past series, but also new bits about how others refer to them or how they refer to others. Mind you, I won't, for example, report all the times All Might calls Shōto 'Todoroki Shōnen' but, since this is how he usually calls him I'll report the first time he does it and then I'll add if he'll call him something different.

With this said let's start.

INTRODUCTIONS DONE BY THE NARRATOR

TODOROKI ENJI

Midoriya Izuku ‘Jiken kaiketsu-sū shijō saita! Nenshō-kei HERO “ENDEAVOR”‼’ 緑谷出久「事件解決数史上最多!燃焼系ヒーロー『エンデヴァー』‼」 Midoriya Izuku “The person who solved the most cases in history! The burning hero “Endeavor”!” [Chap. 3/Ep. 4]

In the manga we don't know who's the narrator but in the anime it's Midoriya.

Enji is called ‘Nenshō-kei HERO “ENDEAVOR”’ (燃焼系ヒーロー『エンデヴァー』 “The burning hero “Endeavor””) instead than Flame Hero Endeavor, probably because Horikoshi hadn't decided to call him as such yet.

TODOROKI SHŌTO

We've two versions for Shōto's introduction, one from the manga and the other from the anime.

PRESENT MIC ‘Suisen nyūgaku-sha 2! Todoroki Shōto. Kosei: “hanrei hannen”! Migi de kōrashi hidari de moyasu! Hani mo ondo mo michisū‼ Bakemono ka yo‼’ プレゼント・マイク『推薦入学者2!轟焦凍。個性:“半冷半熱”!右で凍らし左で燃やす!範囲も温度も未知数‼化け物かよ‼』 Present Mic “Recommended student number 2! Todoroki Shōto. Quirk: "Half cold, half hot"! Freezes with the right and burns with the left! Range and temperature unknown! Is he a monster?” [Chap. 11]

PRESENT MIC ‘Todoroki Shōto. Koitsu mo HERO-ka no suisen nyūgaku-sha 4-nin no uchi hitori. Kosei “hanrei hannen”. Migi de kōrashi hidari de moyasu. Hani mo ondo mo michisū. Bakemono ka yo!’ プレゼント・マイク『轟焦凍。こいつもヒーロー科の推薦入学者4人のうち一人。個性“半冷半熱”。右で凍らし左で燃やす。範囲も温度も未知数。化け物かよ!』 Present Mic “Todoroki Shōto. He’s one of the four recommended students for the Hero Course. His quirk is ‘half cold, half hot’. He freezes with his right hand and burns with his left. The range and temperature are unknown. He’s a monster!” [Ep. 8]

In the manga we don't know who's the narrator but in the anime it's Present Mic.

Shōto is called ‘Suisen nyūgaku-sha’ (推薦入学者 “Recommended student”) which is how you call a student who received a recommendation from his previous school.

He's also called ‘Bakemono’ (化け物 “monster” Lit. “transforming thing”). A bakemono is a class of yōkai (妖怪 "strange apparition") in Japanese folklore. Literally, the terms mean a thing that changes, referring to a state of transformation or shapeshifting, therefore it's used to refer to living things or supernatural beings who have taken on a temporary transformation. Here it's clearly used not with the intent to insult Shōto but to imply Shōto is too amazing to be human.

HOW THE TODOROKIS CALL THEMSELVES

TODOROKI SHŌTO

Ore (俺/おれ Lit. “Oneself”) This term is the most casual form of self-address used by men, which establishes a sense of masculinity. It can be seen as rude, depending on the context, as it’s suitable for conversations among close friends or relatives but not in polite conversation. It emphasizes one’s own status when used with peers and with those who are younger or of lesser status. Among close friends or family, its use conveys familiarity rather than masculinity or superiority. It was used by both genders until the late Edo period and still is in some dialects. [Chap. 11/Ep. 8]

Kodomo (子ども “child”) He refers to himself as one when facing and easily defeating the Villains. [Chap 14/Ep. 10]

PLURAL

-tachi (達/たち) is very common, pretty neutral in terms of formality and it’s super flexible to the point you can add it to pronouns, people’s names, and even non-human things that you want to personify. [Chap. 16/Ep. 11]

HOW TODOROKI SHŌTO CALL OTHERS

VILLAINS:

YATSU (ヤツ “guy/bastard”) Tecnically 'yatsu’ means “guy” but the nuance here is that you’re either using for someone you’re close to, therefore in a familiar way, or it comes out as derogatory. When Shōto calls Villains 'yatsu' he's clearly being derogatory. [Chap. 12/Ep. 10]

Baka (馬鹿/ばか/バカ “stupid” lit. “horse deer”) According to the region it might feel more or less insulting than 'aho' (阿呆/あは/アホ “fool”). Regardless of all this, in the story it's used to imply someone is “being an idiot/lacking intelligence”, where 'aho' is used to imply “they're doing something in a foolish manner”. Generally it’s written in katakana, to also convey how the speaker is really angry and can be used with or without a noun after it. Another common way to write it is in hiragana and writing it in kanji is being considered more a literature way to write it. [Chap. 12/Ep. 10]

Otona (大人 “adult”) While it's normally not an insult in the context it's clearly meant to be. [Chap 14/Ep. 10]

Anta (あんた/アンタ) Contraction of ‘anata’ is also generally not used as it’s considered too direct. Can express contempt, anger or familiarity towards a person. [Chap. 16/Ep. 11]

‘Kosei’ o mote amashita yakara (〝個性〟を持て余した輩 “people who don’t know what to do with their ‘quirks’”) [Chap. 16/Ep. 11]

Seiei (精鋭 “elite troops”) [Chap. 16/Ep. 11]

Koma (コマ/こま/ 駒 “piece”): A 'koma’ is how you call a piece in shōgi or chess… but, of course, figuratively, it’s also how you call someone’s puppet. [Chap. 16/Ep. 11]

CHINPIRA (チンピラ “thug”) [Chap. 16/Ep. 11]

Temē/TemeE (てめえ/てめエ/手前 Lit. “the one in front of my hand”) 'Temē’, a reduction of 'temae’, is, according to some, the rudest way to say “you” even more rude than ‘Kisama’ and it’s used when the speaker is very angry. It’s the sort of thing you might translate with “son of a b*tch” or some other insult along the line. [Chap. 18/Ep. 12]

-ra (等/ち) is reasonably neutral and flexible in terms of formality, but it’s more on the casual side compared to ‘-tachi’, so it’s often associated with friendliness and/or disrespect. Here it's clearly meant to be disrespectful. [Chap. 16/Ep. 11]

ALL MIGHT:

ALL MIGHT (オールマイト) [Chap. 16/Ep. 11]

Heiwa no shōchō (平和の象徴 “symbol of peace”) [Chap. 19/Ep. 12]

TOP (トップ “the top”) [Chap. 19/Ep. 12]

CLASSMATES:

Shōto calls all of them by surname only.

Midoriya (緑谷) [Chap. 20/Ep. 13]

HOW THE OTHERS CALL THE TODOROKIS

TODOROKI SHŌTO IS CALLED:

BAKUGŌ KATSUKI:

Kōri no yatsu (氷の奴 “ice bastard”) It's an one time thing only as Bakugō will switch to another nick for Shōto. [Chap. 11/Ep. 8]

KIRISHIMA EIJIRŌ:

Same as Shōto, Kirishima calls all his classmates by surname only.

Todoroki (轟) [Chap. 13/Ep. 9]

HAGAKURE TŌRU:

Hagakure calls all her classmates by surname + -kun.

Todoroki-kun (轟くん “young Todoroki”) [Chap.21/Ep. 13]

ALL MIGHT:

All Might calls all his students by surname + shōnen.

Todoroki shōnen (轟少年 “Todoroki boy/young Todoroki”) [Chap. 19/Ep. 12]

VILLAIN:

Koitsu (こいつ “this person”) it's a very impolite expression that’s used to refer to “this person.” Although some people may refer to a friend as such, this is usually only if they have an intimate and casual relationship with them. [Chap.16/Ep. 11]

GAKI (ガキ “brat”) It's either used for unruly children or to just be rude with them. [Chap.16/Ep. 11]

KUROGIRI:

Kodomo (子ども/子供 “child”) [Chap. 20/Ep. 13]

EXTRA - HOW THE TODOROKIS DESCRIBES OTHERS AND HOW OTHERS DESCRIBE THEM

TODOROKI SHŌTO ABOUT BAKUGŌ KATSUKI

Todoroki Shōto ‘Mekura mashi o kaneta bakuha de kidō henkō, soshite, sokuza ni mō ikkai… Kangaeru TYPE ni wa mienee ga, igaito sensai da na.’ 轟焦凍「目眩ましを兼ねた爆破で軌道変更、そして、即座にもう一回…考えるタイプには見えねぇが、意外と繊細だな。」 Todoroki Shōto “He changed the trajectory with an explosion that also served as a blinding blow, and then he did it again instantly… He doesn’t seem like the type to think things through, but he’s surprisingly sensitive.” [Chap. 10/Ep. 7]

TODOROKI SHŌTO ABOUT OJIRO MASHIRAO AND HAGAKURE TŌRU

Todoroki Shōto ‘Warukatta na, LEVEL ga chigai sugita.’ 轟焦凍「悪かったな、レベルが違いすぎた。」 Todoroki Shōto “Sorry, our levels are too different.” [Chap. 11/Ep. 8]

TODOROKI SHŌTO ABOUT THE VILLAINS ATTACKING THEM AT USJ

Todoroki Shōto ‘Arawareta no wa koko dake ka gakkō zentai ka… nanni seyo SENSOR ga hannō shineenara, mukō ni sō iu koto dekiru “kosei” (read: YATSU) ga irutte koto da na. Kōsha to hanareta kakuri kūkan, soko ni shōninzū (read: CLASS) ga hairu jikanwari… BAKA da ga AHO ja nee. Kore wa nanrakano mokuteki ga atte yōi shūtō ni kakusaku sa reta kishūda.’ 轟焦凍「現れたのはここだけか学校全体か…何にせよセンサーが反応しねぇ��ら、向こうにそういうこと出来る〝個性〟(ヤツ)がいるってことだな。校舎と離れた隔離空間、そこに少人数(クラス)が入る時間割…バカだがアホじゃねぇ。これは何らかの目的があって用意周到に画策された奇襲だ。」 Todoroki Shōto “Are they just here, or in the whole school? Either way, if the sensors aren’t reacting, then that means there’s a 'quirk' (read: guy/bastard) over there that can do that. An isolated space away from the school building, and a timetable with a small number of students (read: classes) in it. They’re stupid, but not foolish. This was a deliberate and well-planned surprise attack with some kind of purpose.” [Chap. 14/Ep. 10]

Todoroki Shōto ‘Chirashite korosu… ka? Itcha warui ga, anta-ra dō mite mo “‘kosei’ o mote amashita yakara” ijō ni wa miuke rarenee yo.’ 轟焦凍「散らして殺す…か?言っちゃ悪いが、あんたらどう見ても『〝個性〟を持て余した輩』以上には見受けられねぇよ。」 Todoroki Shōto “Scatter and kill them…huh? I hate to say it, but no matter how I look at you guys, you just don’t seem like anything more than ‘people who don’t know what to do with their “quirks”’.” [Chap. 16/Ep. 11]

BAKUGŌ KATSUKI ABOUT TODOROKI SHŌTO

Bakugō Katsuki ‘Kōri no yatsu mite~tsu! Kanawanē n jatte omotchimatta...!!’ 爆豪勝己「氷の奴見てっ!敵わねえんじゃって思っちまった...‼」 Bakugō Katsuki “Look at that ice bastard! I thought there was no way I could beat him...!!” [Chap. 11/Ep. 8]

KIRISHIMA EIJIRŌ ABOUT TODOROKI SHŌTO

Kirishima Eijirō ‘Hade de tsuēttsuttara yappa Todoroki to Bakugō da na.’ 切島鋭児郎「派手で強えっつったらやっぱ轟と爆豪だな。」 Kirishima Eijirō “Flashy and strong, it’s definitely Todoroki and Bakugō.” [Chap. 13/Ep. 9]

ALL MIGHT ABOUT TODOROKI SHŌTO

ALL MIGHT ’Hyōketsu…!! (Todoroki shōnen ka!!Watashi ga kōranai GIRIGIRI no hani o umaku chōsei shite…!! Okage de! Te ga yurunda!!!)’ オールマイト「氷結…!!(轟少年か!!私が凍らないギリギリの範囲をうまく調整して…!!おかげで!手が緩んだ!!!)」 All Might “Freezing…! It’s young Todoroki!! He managed to fine-tune the limit of where I wouldn’t freeze… Thanks to that, his hand loosened!!!)” [Chap. 19/Ep. 12]

Todoroki Shōto ’……Sakki no wa ore ga SUPPORT hairanakerya yabakatta deshou.’ 轟焦凍「……さっきのは俺がサポート入らなけりゃやばかったでしょう。」 Todoroki Shōto “…That last one would have been terrible if I hadn’t supported you.”

ALL MIGHT 'Sore wa soreda, Todoroki shōnen!! Arigato na!! Shikashi daijōbu!! PRO no honki o mite i nasai!!’ オールマイト「それはそれだ、轟少年!!ありがとな!!しかし大丈夫!!プロの本気を見ていなさい!!」 All Might “That’s true, young Todoroki!! Thanks!! But it’ll be fine!! Just watch as I get serious as a pro!!” [Chap. 19/Ep. 12]

That's all for this part.

#boku no hero academia#Todoroki Enji#Todoroki Shouto#Midoriya Izuku#Bakugou Katsuki#Toshinori Yagi#Kirishima Eijirou#Hagakure Tooru#Ojiro Mashirao#Kurogiri#bnha observations

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

The under appreciated shuake dynamic of Akira looking Akechi straight in the eye and telling him a lot of the people he killed probably deserved it.

*coughs in Okumura*

edit: Turns out Okumura isn't as bad as I thought, annoyingly since I still hate him very much. The localisation says that he's responsible for most of the mental shutdowns (which, ???).

This turns out to be a little inaccurate. Okumura is not responsible for most of the shutdowns, but for most of the "odd suspicious cases that aren't accidents or illnesses" that Sae was investigating—presumably things like the naked guy at Wild Duck Burger:

Yusuke 新島検事はまず、一連の連続事件のうち、明らかに事故や病気でない『不審なもの』を抜き出している。 niijima-kenji wa mazu, ichiren no renzoku jiken no uchi, akiraka ni jiko ya byouki de nai "fushinna mono" o nukidashiteiru First, Prosecutor Niijima has been looking into the continued cases of people suddenly collapsing. [lit. Public Prosecutor Niijima has, first of all, extracted odd suspicious cases that were obviously not accidents or illnesses from the continuing series of incidents.] First of all, Prosecutor Niijima has been looking into a subset of the incidents—the peculiar cases that obviously weren't accidents or illnesses.

Yusuke それらに共通点が無いかを探っていたらしい。 sorera ni kyoutsuuten ga nai ka o sagutteita rashii It seems she [was] searching for a common thread to tie them all together.

Yusuke 憶測の部分もあるようだが、過半数の事件で大きな利益を得る立場にあった存在を特定している。 okusoku no bubun mo aru you da ga, kahansuu no jiken de ookina rieki o eru tachiba ni atta sonzai o tokutei shiteiru Some parts seem to be speculation, but she has cited a beneficiary of the majority of these incidents.

... and that beneficiary is Okumura Foods and its CEO Okumura, of course.

Now, we know that Okumura was responsible for deaths—there's at least one case where a car overturns and all four passengers, including a VP of one of Okumura's competitors, are killed. (If you're keeping count for Akechi, that's four dead in one day alone.) Okumura is Thoroughly Unpleasant. He's just not "responsible for most of the mental shutdowns that went on for years" unpleasant.

I think I have this translation right. It makes sense, for one thing, that Okumura was responsible for most of the weird scandals. It doesn't make sense that he was responsible for most of the mental shutdowns.

#asks#persona 5#p5 meta#japanese language#shuake#ren amamiya#akira kurusu#goro akechi#kunikazu okumura#sae niijima#so often i feel i have to emphasise that murder is bad#and so often i'm like#ok but okumura tho

71 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Artwork for Kasaburanka Ni Ai O 〜Satsujinsha Wa Jikū O Koete〜 by Akira Yoneda (aka Akira Komeda), a 1986 Thinking Rabbit game for the PC-8800, PC-9801, FM-7 and Sharp X1 computer series. This is the third entry in the Disc Mysteries series of computer text adventure murder stories, following Dokeshi Satsu Jinjiken and Kagiana Satsujin Jiken.

I became aware of this game due to Riverhill Soft's Windows 95 port, itself an adaptation of Thinking Rabbit's reissuing of the original game for the 3D0 from 1994, including a soundtrack and completely redone color graphics. The game is set in the 1940s and tells the story of a journalist whose high-school friend goes missing. A more atypical twist takes place when she discovers that this friend’s father, allegedly pursued and stabbed to death by members of the government, had invented a time machine.

The rather conspicuous reference to Casablanca and its leading actors, Bogart and Bergman, were erased from later ports (see the 3DO and the Win95 covers); the title also having been sanitized to Toki O Koeta Tegami, or The Letter That Over Came Time. Similarly, allusions to the time travelling theme were much more subtle than in this preciously sinister illustration, whose muted hues and composition bring to mind an Andrew Wyeth landscape.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

For our next profile for Writers in Horror Month 2023 we have Edogawa Ranpo…

Born Tarō Hirai

October 21, 1894

Mie, Empire of Japan

Died July 28, 1965 (aged 70)

Occupation Novelist, literary critic

Language Japanese

Nationality Japanese

Alma mater Waseda University

Genre Mystery, weird fiction, thriller

Tarō Hirai (平井 太郎, Hirai Tarō, October 21, 1894 – July 28, 1965), better known by the pen name Edogawa Ranpo (江戸川 乱歩)[a] was a Japanese author and critic who played a major role in the development of Japanese mystery and thriller fiction. Many of his novels involve the detective hero Kogoro Akechi, who in later books was the leader of a group of boy detectives known as the "Boy Detectives Club" (少年探偵団, Shōnen tantei dan).

Ranpo was an admirer of Western mystery writers, and especially of Edgar Allan Poe. His pen name is a rendering of Poe's name. Other authors who were special influences on him were Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, whom he attempted to translate into Japanese during his days as a student at Waseda University, and the Japanese mystery writer Ruikō Kuroiwa.

Biography

Before World War II

Tarō Hirai was born in Nabari, Mie Prefecture in 1894, where his grandfather had been a samurai in the service of Tsu Domain. His father was a merchant, who had also practiced law. The family moved to what is now Kameyama, Mie, and from there to Nagoya when he was age two. At the age of 17, he studied economics at Waseda University in Tokyo starting in 1912. After graduating in 1916 with a degree in economics, he worked a series of odd jobs, including newspaper editing, drawing cartoons for magazine publications, selling soba noodles as a street vendor, and working in a used bookstore.

In 1923, he made his literary debut by publishing the mystery story "The Two-Sen Copper Coin" (二銭銅貨, Ni-sen dōka) under the pen name "Edogawa Ranpo" (pronounced quickly, this humorous pseudonym sounds much like the name of the American pioneer of detective fiction, Edgar Allan Poe, whom he admired). The story appeared in the magazine Shin Seinen, a popular magazine written largely for an adolescent audience. Shin Seinen had previously published stories by a variety of Western authors including Poe, Arthur Conan Doyle, and G. K. Chesterton, but this was the first time the magazine published a major piece of mystery fiction by a Japanese author. Some, such as James B. Harris (Ranpo's first translator into English), have erroneously called this the first piece of modern mystery fiction by a Japanese writer,[3] but well before Ranpo entered the literary scene in 1923, a number of other modern Japanese authors such as Ruikō Kuroiwa, Kidō Okamoto, Jun'ichirō Tanizaki, Haruo Satō, and Kaita Murayama had incorporated elements of sleuthing, mystery, and crime within stories involving adventure, intrigue, the bizarre, and the grotesque.[4] What struck critics as new about Ranpo's debut story "The Two-Sen Copper Coin" was that it focused on the logical process of ratiocination used to solve a mystery within a story that is closely related to Japanese culture.[5] The story involves an extensive description of an ingenious code based on a Buddhist chant known as the "nenbutsu" as well as Japanese-language Braille.

Over the course of the next several years, Edogawa went on to write a number of other stories that focus on crimes and the processes involved in solving them. Among these stories are a number of stories that are now considered classics of early 20th-century Japanese popular literature: "The Case of the Murder on D. Hill" (D坂の殺人事件, D-zaka no satsujin jiken, January 1925), which is about a woman who is killed in the course of a sadomasochistic extramarital affair, "The Stalker in the Attic" (屋根裏の散歩者, Yane-ura no Sanposha, August 1925), which is about a man who kills a neighbor in a Tokyo boarding house by dropping poison through a hole in the attic floor into his mouth, and "The Human Chair" (人間椅子, Ningen Isu, October 1925), which is about a man who hides himself in a chair to feel the bodies on top of him Mirrors, lenses, and other optical devices appear in many of Edogawa's other early stories, such as "The Hell of Mirrors".

Although many of his first stories were primarily about sleuthing and the processes used in solving seemingly insolvable crimes, during the 1930s, he began to turn increasingly to stories that involved a combination of sensibilities often called "ero guro nansensu", from the three words "eroticism, grotesquerie, and the nonsensical" The presence of these sensibilities helped him sell his stories to the public, which was increasingly eager to read his work. One finds in these stories a frequent tendency to incorporate elements of what the Japanese at that time called "abnormal sexuality" (変態性欲, hentai seiyoku). For instance, a major portion of the plot of the novel The Demon of the Lonely Isle (孤島の鬼, Kotō no oni), serialized from January 1929 to February 1930 in the journal Morning Sun (朝日, Asahi), involves a homosexual doctor and his infatuation for another main character.

By the 1930s, Edogawa was writing regularly for a number of major public journals of popular literature, and he had emerged as the foremost voice of Japanese mystery fiction. The detective hero Kogorō Akechi, who had first appeared in the story "The Case of the Murder on D. Hill" became a regular feature in his stories, a number of which pitted him against a dastardly criminal known as the Fiend with Twenty Faces (怪人二十面相, Kaijin ni-jū mensō), who had an incredible ability to disguise himself and move throughout society. (A number of these novels were subsequently made into films.) The 1930 novel introduced the adolescent Kobayashi Yoshio (小林芳雄) as Kogoro's sidekick, and in the period after World War II, Edogawa wrote a number of novels for young readers that involved Kogoro and Kobayashi as the leaders of a group of young sleuths called the "Boy Detectives Club" (少年探偵団, Shōnen tantei dan). These works were wildly popular and are still read by many young Japanese readers, much like the Hardy Boys or Nancy Drew mysteries are popular mysteries for adolescents in the English-speaking world.

During World War II

In 1939, two years after the Marco Polo Bridge Incident and the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, Edogawa was ordered by government censors to drop his story "The Caterpillar" (芋虫, Imo Mushi), which he had published without incident a few years before, from a collection of his short stories that the publisher Shun'yōdō was reprinting. "The Caterpillar" is about a veteran who was turned into a quadriplegic and so disfigured by war that he was little more than a human "caterpillar", unable to talk, move, or live by himself. Censors banned the story, apparently believing that the story would detract from the current war effort. This came as a blow to Ranpo, who relied on royalties from reprints for income. (The short story inspired director Kōji Wakamatsu, who drew from it his movie Caterpillar, which competed for the Golden Bear at the 60th Berlin International Film Festival.)

Over the course of World War II, especially during the full-fledged war between Japan and the US that began in 1941, Edogawa was active in his local neighborhood organization, and he wrote a number of stories about young detectives and sleuths that might be seen as in line with the war effort, but he wrote most of these under different pseudonyms as if to disassociate them with his legacy. In February 1945, his family was evacuated from their home in Ikebukuro, Tokyo to Fukushima in northern Japan. Edogawa remained until June, when he was suffering from malnutrition. Much of Ikebukuro was destroyed in Allied air raids and the subsequent fires that broke out in the city, but the thick, earthen-walled warehouse which he used as his studio was spared, and still stands to this day beside the campus of Rikkyo University.

Postwar

In the postwar period, Edogawa dedicated a great deal of energy to promoting mystery fiction, both in terms of the understanding of its history and encouraging the production of new mystery fiction. In 1946, he put his support behind a new journal called Jewels (宝石, Hōseki) dedicated to mystery fiction, and in 1947, he founded the Detective Author's Club (探偵作家クラブ, Tantei sakka kurabu), which changed its name in 1963 to the Mystery Writers of Japan (日本推理作家協会, Nihon Suiri Sakka Kyōkai). In addition, he wrote a large number of articles about the history of Japanese, European, and American mystery fiction. Many of these essays were published in book form. Other than essays, much of his postwar literary production consisted largely of novels for juvenile readers featuring Kogorō Akechi and the Boy Detectives Club.

In the 1950s, he and a bilingual translator collaborated for five years on a translation of Edogawa's works into English, published as Japanese Tales of Mystery and Imagination by Tuttle. Since the translator could speak but not read Japanese, and Edogawa could read but not write English, the translation was done aurally, with Edogawa reading each sentence aloud, then checking the written English.[3]

Another of his interests, especially during the late 1940s and 1950s, was bringing attention to the work of his dear friend Jun'ichi Iwata (1900–1945), an anthropologist who had spent many years researching the history of homosexuality in Japan. During the 1930s, Edogawa and Iwata had engaged in a light-hearted competition to see who could find the most books about erotic desire between men. Edogawa dedicated himself to finding books published in the West and Iwata dedicated himself to finding books having to do with Japan. Iwata died in 1945, with only part of his work published, so Edogawa worked to have the remaining work on queer historiography published

In the postwar period, a large number of Edogawa's books were made into films. The interest in using Edogawa's literature as a departure point for creating films has continued well after his death. Edogawa, who had a variety of health issues, including atherosclerosis and Parkinson's disease, died from a cerebral hemorrhage at his home in 1965. His grave is at the Tama Cemetery in Fuchu, near Tokyo.

The Edogawa Rampo Prize (江戸川乱歩賞 Edogawa Ranpo Shō?), named after Edogawa Rampo, is a Japanese literary award which has been presented every year by the Mystery Writers of Japan since 1955. The winner is given a prize of ¥10 million with publication rights by Kodansha.

Works in English translation

Books

• Edogawa Rampo (1956), Japanese Tales of Mystery and Imagination, translated by James B. Harris. 14th ed. Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle Company. ISBN 978-0-8048-0319-9.

• Edogawa Ranpo (1988), The Boy Detectives Club, translated by Gavin Frew. Tokyo: Kodansha. ISBN 978-4-0618-6037-7.

• Edogawa Rampo (2006), The Black Lizard and Beast in the Shadows, translated by Ian Hughes. Fukuoka: Kurodahan Press. ISBN 978-4-902075-21-2.

• Edogawa Rampo (2008), The Edogawa Rampo Reader, translated by Seth Jacobowitz. Fukuoka: Kurodahan Press. ISBN 978-4-902075-25-0. Contains many of Rampo's early short stories and essays.

• Edogawa Rampo (2009), Moju: The Blind Beast, translated by Anthony Whyte. Shinbaku Books. ISBN 978-1840683004.

• Edogawa Rampo (2012), The Fiend with Twenty Faces, translated by Dan Luffey. Fukuoka: Kurodahan Press. ISBN 978-4-902075-36-6.

• Edogawa Ranpo (2013), Strange Tale of Panorama Island, translated by Elaine Kazu Gerbert. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 978-0824837037.

• Edogawa Rampo (2014), The Early Cases of Akechi Kogoro, translated by William Varteresian. Fukuoka: Kurodahan Press. ISBN 978-4-902075-62-5.

• Edogawa Rampo (2019), Gold Mask, translated by William Varteresian. Fukuoka: Kurodahan Press. ISBN 978-4909473066.

Short stories

• Edogawa Ranpo (2008), "The Two-Sen Copper Coin," translated by Jeffrey Angles, Modanizumu: Modernist Fiction from Japan, 1913–1938, ed. William Tyler. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3242-1. pp. 270–89.

• Edogawa Ranpo (2008), "The Man Traveling with the Brocade Portrait," translated by Michael Tangeman, Modanizumu: Modernist Fiction from Japan, 1913–1938, ed. William Tyler. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3242-1. pp. 376–393.

• Edogawa Ranpo (2008), "The Caterpillar," translated by Michael Tangeman, Modanizumu: Modernist Fiction from Japan, 1913–1938, ed. William Tyler. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3242-1. pp. 406–422.

Major works

Private Detective Kogoro Akechi series

Main article: Kogoro Akechi

• Short stories

o "The Case of the Murder on D. Hill" (D坂の殺人事件, D-zaka no satsujin jiken, January 1925)

o "The Psychological Test" (心理試験, Shinri Shiken, February 1925)

o "The Black Hand Gang" (黒手組, Kurote-gumi, March 1925)

o "The Ghost" (幽霊, Yūrei, May 1925)

o "The Stalker in the Attic" (屋根裏の散歩者, Yaneura no Sanposha, August 1925)

o "Who" (何者, Nanimono, November 1929)

o "The Murder Weapon" (兇器, Kyōki, June 1954)

o "Moon and Gloves" (月と手袋, Tsuki to Tebukuro, April 1955)

• Novels

o The Dwarf (一寸法師, Issun-bōshi, 1926)

o The Spider-Man (蜘蛛男, Kumo-Otoko, 1929)

o The Edge of Curiosity-Hunting (猟奇の果, Ryōki no Hate, 1930)

o The Conjurer (魔術師, Majutsu-shi, 1930)

o The Vampire (吸血鬼, Kyūketsuki, 1930) First appearance of Kobayashi

o The Golden Mask (黄金仮面, Ōgon-kamen, 1930)

o The Black Lizard (黒蜥蜴, Kuro-tokage, 1934) Made into a film by Kinji Fukasaku in 1968

o The Human Leopard (人間豹, Ningen-Hyō, 1934)

o The Devil's Crest (悪魔の紋章, Akuma no Monshō, 1937)

o Dark Star (暗黒星, Ankoku-sei, 1939)

o Hell's Clown (地獄の道化師, Jigoku no Dōkeshi, 1939)

o Monster's Trick (化人幻戯, Kenin Gengi, 1954)

o Shadow-Man (影男, Kage-otoko, 1955)

• Juvenile novels

o The Fiend with Twenty Faces (怪人二十面相, Kaijin ni-jū Mensō, 1936)

o The Boy Detectives Club (少年探偵団, Shōnen Tantei-dan, 1937)

Standalone mystery novels and novellas

• Available in English translation

o Strange Tale of Panorama Island (パノラマ島奇談, Panorama-tō Kidan, 1926)

o Beast in the Shadows (陰獣, Injū, 1928)

o The Demon of the Lonely Isle (孤島の鬼, Kotō no Oni, 1929-30)

o Moju: The Blind Beast (盲獣, Mōjū, 1931)

• Novels and novellas which have not been translated into English

o Incident at the Lakeside Inn (湖畔亭事件, Kohan-tei Jiken, 1926)

o Struggle in the Dark (闇に蠢く, Yami ni Ugomeku, 1926-27)

o The White-Haired Demon (白髪鬼, Hakuhatsu-ki, 1931-32)

o A Glimpse Into Hell (地獄風景, Jigoku Fūkei, 1931-32)

o The King of Terror (恐怖王, Kyōfu Ō, 1931-32)

o Phantom Bug (妖虫, Yōchū, 1933-34)[15]

o The Great Dark Room (大暗室, Dai Anshitsu, 1936)

o Ghost Tower (幽霊塔, Yūrei tō, 1936) Based on the adaptation of the Meiji-period adaptation of Alice Muriel Williamson's A Woman in Grey by Ruikō Kuroiwa (黒岩涙香).

o A Dream of Greatness (偉大なる夢, Idainaru Yume, 1943)

o Crossroads (十字路, Jūjiro, 1955)

o Petenshi to Kūki Otoko (ぺてん師と空気男, 1959)

Short stories

• Available in English translation

o "The Two-Sen Copper Coin" (二銭銅貨, Ni-sen Dōka, April 1923)

o "Two Crippled Men" (二癈人, Ni Haijin, June 1924)

o "The Twins" (双生児, Sōseiji, October 1924)

o "The Red Chamber" (赤い部屋, Akai heya, April 1925)

o "The Daydream" (白昼夢, Hakuchūmu, July 1925)

o "Double Role" (一人二役, Hitori Futayaku, September 1925)

o "The Human Chair" (人間椅子, Ningen Isu, October 1925)

o "The Dancing Dwarf" (踊る一寸法師, Odoru Issun-bōshi, January 1926)

o "Poison Weeds" (毒草, Dokusō, January 1926)

o "The Masquerade Ball" (覆面の舞踏者, Fukumen no Butōsha, January–February 1926)

o "The Martian Canals" (火星の運河, Kasei no Unga, April 1926)

o "The Appearance of Osei" (お勢登場, Osei Tōjō, July 1926)

o "The Hell of Mirrors" (鏡地獄, Kagami-jigoku, October 1926)

o "The Caterpillar" (芋虫, Imomushi, January 1929)

o "The Traveler with the Pasted Rag Picture" aka "The Man Traveling with the Brocade Portrait" (押絵と旅する男, Oshie to Tabi-suru Otoko, August 1929)

o "Doctor Mera's Mysterious Crimes" (目羅博士の不思議な犯罪, Mera Hakase no Fushigi na Hanzai, April 1931)

o "The Cliff" (断崖, Dangai, March 1950)

o "The Air Raid Shelter" (防空壕, Bōkūgō, July 1955)

• Short stories which have not been translated into English

o "One Ticket" (一枚の切符, Ichi-mai no Kippu, July 1923)

o "A Frightful Mistake" (恐ろしき錯誤, Osoroshiki Sakugo, November 1923)

o "The Diary" (日記帳, Nikkichō, March 1925)

o "The Abacus Tells a Story of Love" (算盤が恋を語る話, Soroban ga Koi o Kataru Hanashi, March 1925)

o "The Robbery" (盗難, Tōnan, May 1925)

o "The Ring" (指環, Yubiwa, July 1925)

o "The Sleepwalker's Death" (夢遊病者の死, Muyūbyōsha no Shi, July 1925)

o "The Actor of a Hundred Faces" (百面相役者, Hyaku-mensō Yakusha, July 1925)

o "Doubts" (疑惑, Giwaku, September–October 1925)

o "Kiss" (接吻, Seppun, December 1925)

o "Scattering Ashes" (灰神楽, Haikagura, March 1926)

o "Monogram" (モノグラム, Monoguramu, July 1926)

o "A Brute's Love" (人でなしの恋, Hitodenashi no Koi, October 1926)

o "The Rocking-Horse's Canter" (木馬は廻る, Mokuba wa Mawaru, October 1926)

o "Insect" (虫, Mushi, Jun-July 1929)

o "Demon" (鬼, Oni, November 1931-February 1932)

o "Matchlock" (火縄銃, Hinawajū, April 1932)

o "Pomegranate" (石榴, Zakuro, September 1934)

o Horikoshi Sōsa Ikkachō-dono (堀越捜査一課長殿, April 1956)

o "The Wife-Broken Man" (妻に失恋した男, Tsuma ni Shitsuren-shita Otoko, October–November 1957)

o "Finger" (指, Yubi) January 1960

Adaptations of Western mystery novels

• The Demon in Green (緑衣の鬼, Ryokui no Oni, 1936) Adaptation of The Red Redmaynes by Eden Phillpotts

• The Phantom's Tower (幽鬼の塔, Yūki no Tō, 1936) Adaptation of The Hanged Man of Saint-Pholien by Georges Simenon

• Terror in the Triangle-Hall (三角館の恐怖, Sankaku-kan no kyōfu, 1951) Adaptation of Murder among the Angells by Roger Scarlett

Essays

• "The Horrors of Film" (1925)

• "Spectral Voices" (1926)

• "Confessions of Rampo" (1926)

• "The Phantom Lord" (1935)

• "A Fascination with Lenses" (1936)

• "My Love for the Printed Word" (1936)

• "Fingerprint Novels of the Meiji Era" (1950)

• "Dickens vs. Poe" (1951)

• "A Desire for Transformation" (1953)

• "An Eccentric Idea" (1954)

These ten essays are included in The Edogawa Rampo Reader.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Actor Masaaki Maeda Passes Away

The Sankei Shimbun has reported that actor Masaaki Maeda passed away on February 27, 2024 due to ischemic heart failure. He was 91 years old at the time of his passing. In anime, Maeda’s roles included Carozzo “Iron Mask” Ronah in Mobile Suit Gundam F91, Shogoro Yano in Seishun Anime Zenshu, and Nora in Hoero! Bun Bun. He was also known for the Ken-chan and Jiken Kisha television series. Source:…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

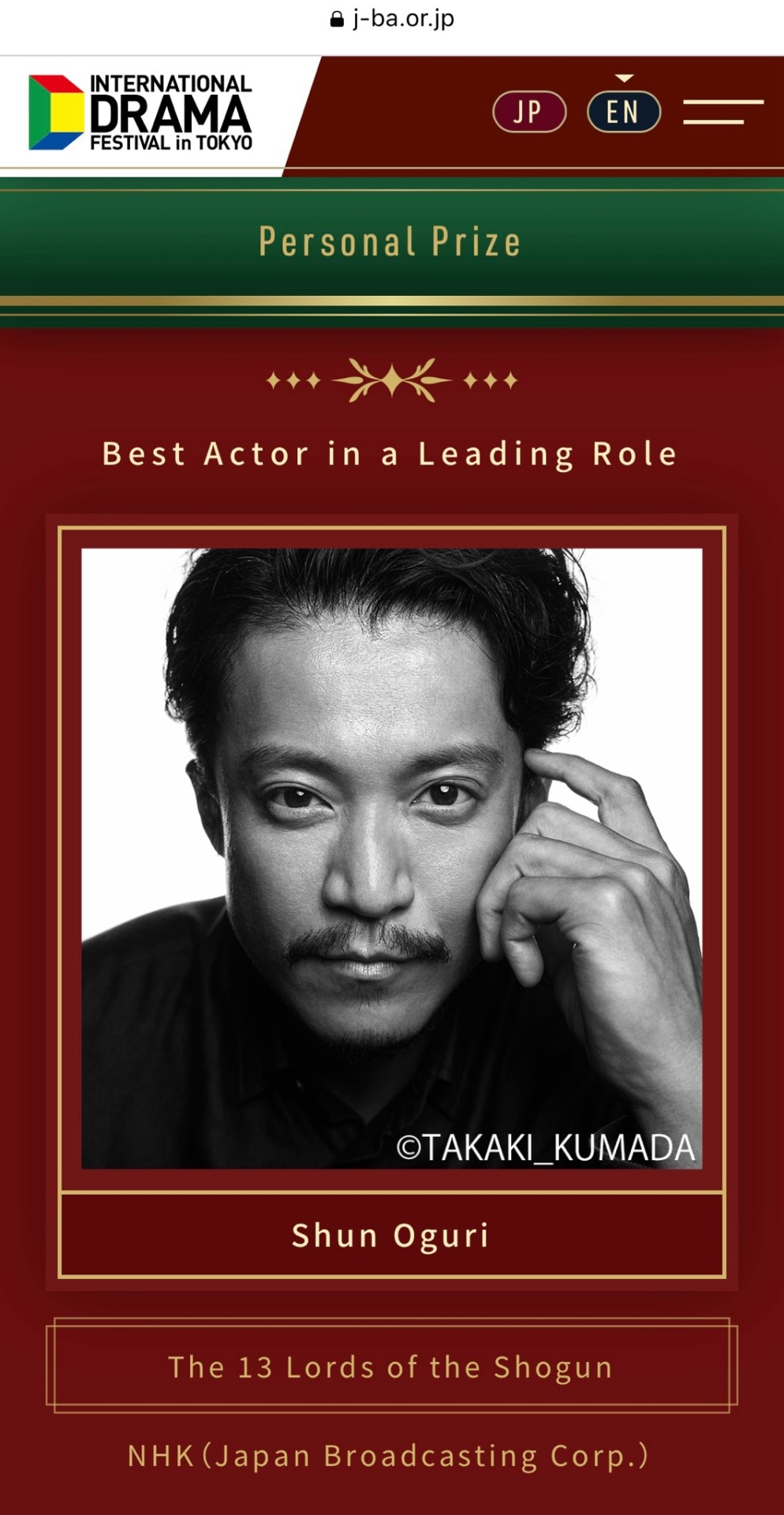

Winners of the Tokyo Drama Award 2023

https://j-ba.or.jp/drafes/award/

Grand Prix - Drama Series: Brush Up Life

Excellence Award - Drama Series:

- Kamakuradono no 13 nin

- Hoshi furu yoru ni

- silent

- Elpis - Kibou, arui wa wazawai -

- Fence

Grand Prix - Drama SP: TOKYO MER ~ Hashiru kinkyuu kyuumeishitsu [Sumidagawa Mission]

Excellence Award - Drama SP:

- Mikaiketsu Jiken File.09 Matsumoto Seicho to [Shousetsu Teikin Jiken]

- Seiri no ojisan to sono musume

- Kami no te

- Kansatsui Asagao 2022 SP

Individual Awards:

Best Leading Actor: Oguri Shun (Kamakuradono no 13 nin)

Best Leading Actress: Kawaguchi Haruna (silent)

Best Supporting Actor: Meguro Ren (silent)

Best Supporting Actress: Kaho (silent)

Best Script: Baka Rhythm (Brush Up Life)

Best Directing: Kazama Daiki (silent)

Best Theme Song: "Subtitle" by Official Hige Dandism

1 note

·

View note

Text

OKURA: MEIKYU IRI JIKEN SOSA オクラ〜迷宮入り事件捜査〜 2024, Okamoto Shingo, Ishii Yasuharu, Komaki Sakura.

#okura: meikyu iri jiken sosa#okura: cold case investigation#オクラ〜迷宮入り事件捜査〜#series#jdrama#sugino yosuke#sorimachi takashi#jdramaedit#jflowgifs#*#okura: 1.05

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

[BD Split] S.Q.S Episode 5 -Takamura Shiki Shoushitsu Jiken-

[Re-blogs Appreciated; May share this to other sites!]

REPOST because I somehow deleted my original post? There’s currently 15 slots opened. My splits are designed with extra slots so if you feel you cannot afford right now, you can join at a later date (if there’s any extra slots left)!

You will receive: DISC 1~2 & SPECIAL DISC 1~2 Rips + Booklet Scans

Status: On hand / Delayed file sharing: IveSta 2 split is priority –> Tsukista Act 10 –> SQS 5

Price: 12 USD

Payment accepted through PayPal.

Please message me if you want to join.

You can also DM me on my Twitter (Fastest response rate). I will send you more information include details about my split.

Payment Deadline: Payment is due ASAP / 13 available slots

You are more than welcome to message me if you have questions as well~

#sqs#sq stage#SQ series#tsukino production#tsukipro#solids#quell#keiasta splits#sqs episode 5#Takamura Shiki Shoushitsu Jiken

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

北村一輝 & 吉瀬美智子 in: 『シグナル ~ 長期未解決事件捜査班』(2018) Signal ~ Cold Cases Investigation Team

A remake of a remake (SK — “Signal” 2016) of a remake (US — “Frequency” 2013) of yet another remake (HK — “To Get Unstuck in Time” 2004)? Not that I'm complaining, I do like the “Frequency” film and I don't mind all the ‘re-adaptations’ (I don't think the HK or SK series ever acknowledged it was ‘inspired’ by the 2000 film, though) I've seen so far.

#I was wondering why the only female lead in here looked familiar#Then I got reminded I had seen her in [BOSS]#Being out of the loop of Japanese series for some time#Great to still see familiar faces around (her and Kitamura)#Because I'm still not liking the other younger leading guy#Signal Chouki Mikaiketsu Jiken Sousahan#J Drama#Kitamura Kazuki#Kichise Michiko

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Keeping up with the Todorokis or, just me observing the Todorokis (Anime version): Ep. 1 & 4

So this is nothing else but a collection of informations, series by series, episode by episode about how the Todorokis appear in it, especially compared to the manga.

Ep. 1 Midoriya Izuku: Origin (緑谷出久:オリジン Midoriya Izuku: ORIGIN)

trasposition of

Chap. 1 Midoriya Izuku: Origin (緑谷出久:オリジン Midoriya Izuku: ORIGIN)

I'm mentioning Ep. 1 merely because they cut the bit in which Enji appeared on a screen (as well as Midnight).

It makes sense to cut him (and Midnight) as in the anime they would have been hardly visible.

Ep. 4 Start Line (スタートライン START LINE)

trasposition of

Chap. 3 Entrance Exam (入 (にゅう) 試 (し) Nyūshi)

This episode only gives us a quick glimpse of Enji/Endeavor as Midoriya introduces the Heroes who also attented U.A. High.

Midoriya Izuku ‘U.A. kōkō HERO-ka‼ Soko wa PRO ni hissu no shikaku shutoku o mokuteki to suru yōsei-kō! Zenkoku dōkachū, mottomo ninki de mottomo muzukashiku, sono bairitsu wa reinen 300 o koeru‼ Kokumin eiyoshō ni dashin sa reru mo kore o koji‼ No. 1 HERO “ALL MIGHT”‼ Jiken kaiketsu-sū shijō saita! Nenshō-kei HERO “ENDEAVOR”‼ BEST JEANIST 8 nen renzoku jushō‼”BEST JEANIST”! Idaina (read: GRATEFUL) HERO ni wa o U.A. sotsugyō ga zettai jōken‼’ 緑谷出久「雄英高校ヒーロー科‼そこはプロに必須の資格取得を目的とする養成校!全国同科中、最も人気で最も難しく、その倍率は例年300を超える‼国民栄誉賞に打診されるもこれを固辞‼No.1ヒーロー『オールマイト』‼事件解決数史上最多!燃焼系ヒーロー『エンデヴァー』‼ベストジーニスト8年連続受賞‼『ベストジーニスト』!グレイトフルヒーローになる為には雄英卒業が絶対条件‼」 Midoriya Izuku “U.A. High School’s Hero Course! It’s a training school where students acquire the qualifications necessary to become professionals! It’s the most popular and difficult course in the country, with the competition rate exceeding 300 every year! The one who was offered the People’s Honor Award but firmly refused! No. 1 Hero “All Might”! The person who solved the most cases in history! The burning hero “Endeavor”! Winner of the Best Jeanist award for 8 consecutive years! “Best Jeanist”! In order to become a Grateful Hero, graduating from U.A. is an absolute must!!”

In the manga is hard to say who's doing the narration but in the anime we can hear it's Midoriya. The added how All Might is the Number 1 Hero and changed a little the final sentence but kept the fact that Enji was called the Nenshō-kei HERO “ENDEAVOR” instead than the FLAME HERO “ENDEAVOR” as he'll be called for the rest of the story.

Also, compared to the manga who showed the three Heroes together, the anime shows them alone, one after the other.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

--Welcome to the Red Dream.

Commission for Mizumori Fumaira. The comic itself is not part of the commission, but rather my own bonus for her because we shared the same love for these two.

They are Kiyoshiro Yumemizu and Ai Iwasaki from the comic Meitantei Kiyoshiro Yumemizu Jiken Note (adapted from a novel with the same name, drawn by Kei Enue and written by Kaoru Hayamine).

This fan comic took place after the vol. 7 of the series (the Red Dream arc as I fondly call it).

The context here is that the Great Detective, Kiyoshiro Yumemizu (that Ai kept called as “Professor” due to his previous profession as a University Professor) was a very peculiar individual. He sometimes seen as very aloof (though generally he’s a gentle and warm person, albeit very slovenly, glutton, and has zero common-sense) and he somewhat has the knowledge about this thing called the “Red Dream”.

No one know what it does, or what it is even exactly, but they said people who could see the “Red Dream” would become one of its residence, and it’s possible to be lost within it. I took it as a condition where the border between illusion and reality has become so blurred it’s easy to doubt your own existence... but this is just my theory.

In this very arc in the manga, the structure was very confusing. Not only there’s people dying (which is very surprising because this comic was usually very light and no people died in real time), the comic within comic within comic format creates a very confusing Inception-like feeling that still confuses the readers of every age, even until this moment (me included).

It was a very heavy arc because one of Professor’s closest person, Ai Iwasaki (his neighbor, one of the Iwasaki triplets) ended up getting severely harmed. The line “a great detective won’t let his precious person die” was taken straight from the manga. A very powerful line that delivered very strongly and left an everlasting impact due to how serious Professor has become. The villain has crossed the line.

(The cover for the volume of this arc also features a very serious-looking Professor. This is a man that smiled on every other covers, except for this volume.)

In the end, we didn’t know what the deal with Professor and the red dream, or if he really exist or he somehow gained sentience that he’s just a mere character in a story. Who knows. I get headache from thinking about this supposed-to-be-a-juvenile-mystery-series.

#The Great Detective Kiyoshiro Yumemizu#Meitantei Yumemizu Kiyoshiro Jiken Note#Kiyoshiro Yumemizu#Kaoru Hayamine#Kei Enue#fanart#Ai Iwasaki#Nakayoshi#commission#comic strips#Kuroha Ai#I put too much effort to such an old comic no one knew#but I LOVE this series#I'm curious about the end; the publisher never made it to the end of this series :'(

39 notes

·

View notes