#jazz spot dolphy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

On October 7 Monday, Kota Saito plays guitar in the improvisation live performance, MEETING #12 @Jazz Spot Dolphy, Noge (Yokohama). The performance will be with Yusuke Shimada (butoh dancer) and Mikio Ishida (jazz pianist).

10月7日(月)、齋藤浩太がMEETING #12 @野毛Jazz Spot Dolphyに出演します。嶋田��介(舞踏)、石田幹雄(ジャズピアノ)との即興パフォーマンスです。是非お越しください。

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#eric dolphy#eric dolphy at the five spot#vinyl#jazz#vinyl records#booker little#mal waldron#richard davis#eddie blackwell

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eric Dolphy - The Gaslight Inn, New York City, October 7, 1962

Since kicking off a few years back, the Vintage Music Experience YouTube channel has been a ridiculously overstuffed treasure chest of rare jazz recordings. Things have slowed down slightly in recent months, but VME is still coming up with the goods with frightening regularity. You could probably devote all of your listening hours to keeping up ...

Here's one I got caught up with — Eric Dolphy in 1962 with a very young Herbie Hancock. This vibe-y radio broadcast takes us over to Red Hook, where the Gaslight Inn enjoyed a brief lifespan as a new jazz hot spot. It sounds like a fun spot, maybe a bit rowdier than the clubs across the water in Manhattan. Nevertheless, Dolphy is able to quiet down the crowd early on with a gorgeous version of Mal Waldron and Billie Holiday's "Left Alone," Eric's bewitching flute leading the way. I don't think Billie ever actually recorded this typically devastating song, but you can hear Waldron accompanying Abbey Lincoln on it right here, for some idea of what that might've sounded like.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bootleg of John Coltrane 4tet + Eric Dolphy in Copenhagen 1961

youtube

(English / Español)

Without a doubt, saxophonist John Coltrane's band after he left trumpeter Miles Davis in 1960 is one of the defining groups of jazz, and for the year or so during which multi- instrumentalist Eric Dolphy joined Coltrane on reeds, the band became a phrenic and frenetic powerhouse that shook jazz to its core. Between Dolphy's piercingly distinct sound and Coltrane's newly developed interest in Eastern modalities, as well as the driving force of one of the all-time great rhythm sections—pianist McCoy Tyner, drummer Elvin Jones, and bassists Jimmy Garrison or Reggie Workman—this was a band to reckon with.

Recorded on November 20, 1961, mere weeks after the legendary Village Vanguard sessions that got critics' dander up, this album finds the quintet at the Falkonercenter in Copenhagen, playing the first part of a sold-out two act bill (the second act was trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie's band: what a concert!). Here, Workman is still holding down the bass chair, though Jimmy Garrison had likely won himself the spot for future iterations of the Coltrane band with his performance on "Chasin' The Trane" back in New York. Previously made available on vinyl, but only just released in a complete CD form with announcements by presenter Norman Granz, this is a must-have for Coltrane or Dolphy completists.

The album boasts two curiosities that distinguish it from all the other Coltrane recordings available in the marketplace. The first, a pair of rare false starts on "My Favorite Things," prompting an apology from the ever mild-mannered Coltrane to the audience, will likely only interest the true die-hard fan. But a version of Victor Young's beautiful "Delilah," purported to be the only version of the song that Coltrane or Dolphy ever recorded, is a deluxe addition to any fan's collection.

Without a doubt, this would have been an astonishing performance to witness. While Coltrane, Dolphy and McCoy are fantastic as always, part of the pleasure of hearing this band is in the seemingly telepathic give and take between all players. Hearing Coltrane's fire with only hints of the sparks that Elvin Jones is lighting behind him isn't the complete experience. That being said, it's still a lot better than most of what's out there.

Tracks: Announcement by Norman Granz; Delilah; Every Time We Say Goodbye; Impressions; Naima; My Favorite Things (false starts); Announcement by John Coltrane; My Favorite Things.

Personnel: John Coltrane: tenor and soprano saxophones; Eric Dolphy: alto saxophone, flute, bass clarinet; McCoy Tyner: piano; Reggie Workman: bass; Elvin Jones: drums.

Extract text from: allaboutjazz.com / By Warren Allen

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Sin lugar a dudas, la banda del saxofonista John Coltrane tras su marcha del trompetista Miles Davis en 1960 es uno de los grupos que definen el jazz, y durante el año en que el multiinstrumentista Eric Dolphy se unió a Coltrane en las cañas, la banda se convirtió en una potencia frenética que sacudió el jazz hasta sus cimientos. Entre el sonido penetrantemente distintivo de Dolphy y el nuevo interés de Coltrane por las modalidades orientales, así como la fuerza motriz de una de las mejores secciones rítmicas de todos los tiempos -el pianista McCoy Tyner, el batería Elvin Jones y los bajistas Jimmy Garrison o Reggie Workman-, ésta era una banda a tener en cuenta.

Grabado el 20 de noviembre de 1961, pocas semanas después de las legendarias sesiones del Village Vanguard que levantaron la polvareda de la crítica, este álbum presenta al quinteto en el Falkonercenter de Copenhague, tocando la primera parte de un programa de dos actos con las entradas agotadas (el segundo acto fue la banda del trompetista Dizzy Gillespie: ¡menudo concierto!). Aquí, Workman sigue ocupando la silla del bajo, aunque Jimmy Garrison probablemente se había ganado el puesto para futuras iteraciones de la banda de Coltrane con su actuación en "Chasin' The Trane" en Nueva York. Anteriormente disponible en vinilo, pero recién editado en CD completo con anuncios del presentador Norman Granz, es un disco imprescindible para los completistas de Coltrane o Dolphy.

El álbum cuenta con dos curiosidades que lo distinguen de todas las demás grabaciones de Coltrane disponibles en el mercado. La primera, un par de raras salidas en falso en "My Favorite Things", que provocaron una disculpa del siempre apacible Coltrane al público, probablemente sólo interesará a los verdaderos fans acérrimos. Pero una versión de la hermosa "Delilah" de Victor Young, que se supone que es la única versión de la canción que Coltrane o Dolphy grabaron jamás, es una adición de lujo a la colección de cualquier fan.

Sin duda, habría sido una actuación asombrosa. Aunque Coltrane, Dolphy y McCoy están fantásticos como siempre, parte del placer de escuchar a esta banda está en el toma y daca aparentemente telepático entre todos los músicos. Escuchar el fuego de Coltrane con sólo indicios de las chispas que Elvin Jones enciende tras él no es la experiencia completa. Dicho esto, sigue siendo mucho mejor que la mayoría de lo que hay en el mercado.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

LÉGENDES DU JAZZ

BILLY HIGGINS, ‘’SMILING BILLY’’

“Billy Higgins’s talent will never be duplicated – not that any style can be – but his mark on jazz history is indelible. Billy Higgins represents four decades of total dedication to his chosen form of American music: jazz.”

- Cedar Walton

Né le 11 octobre 1936 à Los Angeles, en Californie, Billy Higgins était issu d’une famille de musiciens. Élevé dans le ghetto afro-américain de Watts, Higgins avait commencé à jouer de la batterie à l’âge de cinq ans sous l’influence d’un de ses amis batteurs. À l’âge de douze ans, Higgins avait travaillé avec des groupes de rhythm & blues, notamment avec des musiciens comme Amos Milburn et Bo Diddley. Au début de sa carrière, Higgins avait également collaboré avec les chanteurs et chanteuses Brook Benton, Jimmy Witherspoon et Sister Rosetta Tharpe.

Surtout influencé par Kenny Clarke, Higgins avait aussi été marqué par Art Tatum et Charlie Parker. En octobre 2001, le chef d’orchestre John Riley du Vanguard Jazz Orchestra avait résumé ainsi les influences d’Higgins: “Billy dug the melodiousness of Max Roach and Philly Joe Jones, Art Blakey’s groove, Elvin Jones’s comping, Ed Blackwell’s groove orchestration, and Roy Haynes’ individualist approach.” Higgins avait hérité de son surnom de ‘’Smiling Billy’’ en raison du plaisir communicatif qu’il avait de jouer de la batterie.

DÉBUTS DE CARRIÈRE

Higgins, qui s’était rapidement intéressé au jazz, avait commencé sa carrière en se produisant avec différents musiciens locaux comme Dexter Gordon, Carl Perkins, Leroy Vinnegar, Slim Gaillard, Teddy Edwards, Joe Castro et Walter Benton. À l’âge de quatorze ans, Higgins avait rencontré le trompettiste Don Cherry. En 1953, le duo était parti en tournée sur la Côte ouest avec les saxophonistes George Newman et James Clay dans le cadre du groupe The Jazz Messiahs.

En 1957, Higgins s’était joint au quartet de Red Mitchell qui comprenait également la pianiste Lorraine Geller et le saxophoniste ténor James Clay. Higgins avait d’ailleurs fait ses débuts sur disque avec le groupe de Mitchell dans le cadre d’une collaboration avec les disques Contemporary de Lester Koenig. Higgins avait quitté le groupe de Mitchell peu après pour se joindre à la nouvelle formation d’Ornette Coleman, aux côtés de Don Cherry à la trompette, de Walter Norris au piano, et de Don Payne et de Charlie Haden à la contrebasse. Higgins, qui avait commencé à pratiquer avec Coleman en 1955, avait fait partie du groupe du saxophoniste sur une base permanente de 1958 à 1959, participant notamment à l’enregistrement des albums ‘’Something Else’’ (février-mars 1958), ‘’The Shape of Jazz to Come’’ et ‘’Change of the’’ Century’’, tous deux enregistrés en 1959. Higgins avait également participé aux concerts controversés du groupe au club Five Spot de New York en novembre 1959. Commentant la prestation du groupe, le critique Jon Thurber du Los Angeles Times avait qualifié le concert d’un des événements les plus légendaires de l’époque. Thurber avait ajouté: ‘’The event crowded the room with every available jazz musician and aficionado.”

Higgins s’étant vu interdire l’accès des clubs de New York à la suite d’une altercation avec la police, Higgins s’était joint au quintet de Thelonious Monk. Il était par la suite allé jouer avec le groupe John Coltrane en 1960.

Le 21 décembre 1960, Higgins avait de nouveau retrouvé Coleman dans le cadre de l’enregistrement de l’album controversé ‘’Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation’’ mettant en vedette le double quartet de Coleman, composé de Coleman au saxophone alto, de Don Cherry à la trompette et au cornet, de Freddie Hubbard à la trompette, d’Eric Dolphy à la flûte, à la clarinette basse et au saxophone soprano, de Scott LaFaro et Charlie Haden à la contrebasse et de Higgins et Ed Blackwell à la batterie.

Devenu un des batteurs les plus en demande du monde du jazz, Higgins avait participé à plusieurs sessions pour les disques Blue Note dans les années 1960, principalement dans des contextes de hard bop. En 1962-63, Higgins s’était joint au groupe de Sonny Rollins avec qui il avait participé à une tournée en France. À la même époque, Higgins s’était également produit avec Donald Byrd, Dexter Gordon, Hank Mobley, Art Farmer, Jimmy Heath, Steve Lacy, Jackie McLean, Herbie Hancock et Lee Morgan.

Le jeu de Higgins à la batterie avait été particulièrement mis en évidence sur des enregistrements comme “Point of Departure’’ d’Andrew Hill, “Takin' Off’’ d’Herbie Hancock (qui comprenait le classique ‘’Watermelon Man’’), “Freedom Jazz Dance” d’Eddie Harris, ‘’Go !’’ de Dexter Gordon et “The Sidewinder’’ de Lee Morgan.

À partir de 1966, Higgins s’était produit régulièrement avec le pianiste Cedar Walton, avec il a enregistré plusieurs albums pour des compagnies de disques européennes jusqu'au milieu des années 1980.

DERNIÈRES ANNÉES

Après s’être fait désintoxiquer en 1971, Higgins avait formé le groupe Brass Company avec le saxophoniste ténor Claude Bartee et le trompettiste Bill Hardman. Après s’être installé à Los Angeles en 1978, Higgins avait formé avec Walton et le le saxophoniste George Coleman le groupe Eastern Rebellion. À la fin des années 1970, Higgins avait également enregistré comme leader, faisant paraître des albums comme ‘’Soweto’’ (1979), ’’The Soldier’’ (1979) et ‘’Once More’’ (1980).

Dans les années 1980, Higgins avait également collaboré avec Pat Metheny et Slide Hampton. Tout en participant à des tournées internationales avec les Timeless All Stars et à des réunions avec Ornette Coleman et Don Cherry, Higgins avait eu un petit rôle dans le film de Bertrand Tavernier ‘’Round Midnight’’ aux côtés de Dexter Gordon en 1986. Il avait aussi fait partie du trio de Hank Jones. Toujours en 1986, Higgins avait fait partie du Quartet West de Charlie Haden, aux côtés d’Ernie Wax au saxophone et d’Alan Broadbent au piano. Après avoir connu certains problèmes de santé, Higgins avait été éventuellement remplacé par Larance Marable.

Très impliqué socialement, Higgins avait co-fondé en 1989 avec le poète Kamau Daáood le World Stage, un centre communautaire et culturel qui avait pour but de favoriser le développement de la musique, de la littérature et de l’art afro-américain. Le groupe, qui soutenait également la carrière de jeunes musiciens de jazz, organisait régulièrement des ateliers, des enregisrements et des concerts dans le quartier de Leimert Park à Los Angeles. Tous les lundis soirs, Higgins donnait des cours de batterie aux membres de la communauté. Higgins, qui s’intéressait particulièrement aux enfants, avait déclaré au cours d’une entrevue accordée au magazine LA Weekly en 1999:

"They should bus children in here so they can see all this, so they could be a part of it. Because the stuff that they feed kids now, they'll have a bunch of idiots in the next millennium as far as art and culture is concerned. I play at schools all the time, and I ask, 'Do you know who Art Tatum was?' 'Well, I guess not.' Some of them don't know who John Coltrane was, or Charlie Parker. It's our fault. Those who know never told them. They know who Elvis Presley was, and Tupac, or Scooby-Dooby Scoop Dogg--whatever. Anybody can emulate them, because it's easy, it has nothing to do with individualism. There's so much beautiful music in the world, and kids are getting robbed.’’

Également professeur, Higgins avait enseigné à la faculté de jazz de l’Université de Californie à Los Angeles (UCLA). Il avait aussi été très impliqué dans plusieurs activités en faveur de la conservation et de la promotion du jazz.

Toujours très en demande dans les sessions d’enregistrement, Higgins s’était produit sur une base régulière avec le saxophoniste Charles Lloyd de 1999 à 2001. Il dirigeait aussi ses propres groupes.

Atteint d’une maladie des reins, Higgins avait dû mettre sa carrière sur pause dans les années 1990, mais il avait repris sa carrière après avoir subi avec succès une greffe du foie en mars 1996, se produisant notamment avec Ornette Coleman, Charles Lloyd et Harold Land.

Billy Higgins est mort le 4 mai 2001 au Daniel Freeman Hospital d’Inglewoood, en Californie, des suites d’un cancer du foie. Il était âgé de soixante-quatre ans. Ont survécu à Higgins ses fils Ronald, William Jr., David et Benjamin, ses filles Ricky et Heidi, son frère Ronald, son gendre Joseph (Jody) Walker, son neveu Billy Thetford et sa fiancée Glo Harris. À l’époque, Higgins avait divorcé de sa première épouse Mauricina Altier Higgins.

Peu avant sa mort, Higgins avait joué le rôle d’un batteur de jazz dans le film ‘’Southlander’’ de Steve Hanft et Ross Harris.

Au moment de son décès, Higgins venait d’être hospitalisé pour une pneumonie et attendait une seconde greffe du foie. Dans son dernier numéro publié avant la mort de Higgins, la revue française Jazz Magazine avait lancé une campagne de souscription en faveur de Higgins, le batteur n’ayant pas des revenus suffisants pour couvrir ses frais médicaux. Deux ans avant sa mort, le saxophoniste Charles Lloyd avait témoigné de la santé fragile de Higgins en déclarant: ’’Billy Higgins a une santé précaire, et cette fragilité physique confère à son jeu une délicatesse unique. Jouer avec lui, c'est un peu comme jouer à la maison. Il y a une telle conjonction entre nous. Un seul regard suffit et le disque est enregistré.’’ Comparant Higgins à un maître zen, Lloyd avait ajouté: “everybody who plays with him gets that ecstatic high.” Rendant hommage à Higgins après sa mort, son collaborateur de longue date, le pianiste Cedar Walton, avait ajouté: “Billy Higgins’s talent will never be duplicated – not that any style can be – but his mark on jazz history is indelible. Billy Higgins represents four decades of total dedication to his chosen form of American music: jazz.”

Higgins avait livré sa dernière performance le 22 janvier 2001 dans le cadre d’un concert présenté au club Bones and Blues de Los Angeles. Le concert, qui mettait également en vedette les saxophonistes Charles Lloyd et Harold Land, avait pour but de soutenir la lutte d’Higgins contre le cancer du foie.

Reconnu pour son swing léger mais actif, son jeu subtil et raffiné et sa façon mélodique de jouer de la batterie, Billy Higgins avait collaboré avec les plus grands noms du jazz au cours de sa carrière, de Ornette Coleman à Don Cherry, en passant par Sonny Rollins, Cedar Walton, Herbie Hancock, Abudullah Ibrahim, Bheki Mseleku, Roy Hargrove, Pat Metheny, Charles Lloyd, Donald Byrd, Freddie Hubbard, Eric Dolphy, John Scofield, Thelonious Monk, Scott LaFaro, Cecil Taylor, Charlie Haden, Hank Jones, Dexter Gordon, Hank Mobley, Grant Green, Joe Henderson, Art Farmer, Sam Jones, Dave Williams, Bob Berg, Monty Waters, Clifford Jordan, Ira Sullivan, Sun Ra, Milt Jackson, Jimmy Heath, Joshua Redman, John Coltrane, Eddie Harris, Steve Lacy, David Murray, Art Pepper, Mal Waldron, Jackie McLean et Lee Morgan. Higgins avait également collaboré avec le compositeur La Monte Young.

Higgins a participé à plus de 700 enregistrements au cours de sa carrière, ce qui en faisait un des batteurs les plus enregistrés de l’histoire du jazz. Qualifiant le jeu de Higgins, le critique Ted Panken du magazine Down Beat avait commenté: "To witness him--smiling broadly, eyes aglimmer, dancing with the drum set, navigating the flow with perfect touch, finding the apropos tone for every beat--was a majestic, seductive experience." De son côté, le chef d’orchestre Larry Riley avait précisé: “Billy was a facilitator, not a dominator. He would enhance the direction the music ‘wanted’ to go in rather than impose his own will on the composition. You can hear that Billy was a master at creating a good feeling in the rhythm section. Dynamically, he used the entire spectrum— but with great restraint. His comping and overall flow were very precise but very legato.”

Higgins, qui avait surtout appris son métier en utilisant une approche d’essais-erreurs, avait résumé ainsi sa méthode d’apprentissage:

“That’s where you learn. You learn to be in context with the music and interpret. You make your mistakes and you learn. Most of the drummers that are working are people who know how to make the other instruments get their sound. Kenny Clarke was a master at that. It sounds like he was doing very little, and he was, but what he implied made all the instruments get their sound. Philly Joe, Elvin—as strong as they played, they still bring out the essence of what the other musicians are playing. Roy Haynes, Max, Art Blakey—none of them played the same. You try to add your part, but the idea is to be part of the music and make it one. That’s the whole concept for me.”

Décrivant la contribution d’Higgins à l’histoire du jazz, le contrebassiste Ron Carter avait ajouté: “Billy Higgins was the drummer of the 20th century who put the music back into the drums. He was fabulous. He always played the form, and he was aware not only of the soloists, but also of his rhythm section mates.” Saluant le professionnalisme et la grande préparation d’Higgins, Carter avait précisé: “He was always on time, with his equipment ready, and he contributed to the general outlook of the group no matter where [we were] or how many people were involved. He made the music feel good.” De son côté, le pianiste Cedar Walton avait commenté: “His style is well-documented, but to see Billy in person at his drums was the ultimate jazz experience.”

Billy Higgins avait été élu ‘’Jazz Master’’ par la National Endowment for the Arts en 1997. En 1988, Higgins avait également remporté un prix Grammy conjointement avec Ron Carter, Herbie Hancock et Wayne Shorter pour la composition “Call Sheet Blues” tirée de la bande sonore du film ‘’Round Midnight.’’ Par la suite, Higgins avait fait partie du Round Midnight Band avec le saxophoniste Dexter Gordon.

Le saxophoniste Charles Lloyd avait rendu un des meilleurs hommages qu’on pouvait rendre à Higgins lorsqu’il avait déclaré: "Jazz is the music of wonder and, and he's the personification of it.��’ Higgins s’était toujours considéré comme un peu privilégié d’avoir pu faire une carrière musicale. Comme il l’avait mentionné peu de temps avant sa mort: "I feel blessed to play music, and it's also an honor to play music. You've got a lot of people's feeling in your hands."

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

11/22 おはようございます。Steve Lacy / Soprano Sax prlp7125 等更新しました。

Henny Vonk / Rebootin Sjp164Steve Lacy / Soprano Sax prlp7125Sonny Criss / This is Criss Pr7511Eric Dolphy / at Five Spot vol2 Prst7826Eric Dolphy / Last Date Lm82013Joe Viera Gerhard Laber / Kontraste cal30619Boris Vian / En Avant La Zizique Sh10002Andre Benichou / Jazz Guitar Bach h71069Candido / Thousand Finger Man – Rock & Shuffle rhr3464Candido / Jingo – Dancin and Pracin sg219Hot Cuisine /…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Eric Dolphy - At The Five Spot, Volume I. (LP, Album, RE)

Vinyl(VG++) Sleeve(VG+) Insert(VG++) Obi(missing) // missing Obi 帯なし / No scratches on Vinyl, VG+ or better. in great shape / / nice sleeve except for some minor foxing. ジャケットに軽いシミ / コンディション 盤 : Very Good Plus (VG+) コンディション ジャケット : Very Good Plus (VG+) コンディションの表記について [ M > M- > VG+ > VG > G+ > G > F > P ] レーベル : Prestige,New Jazz – SMJ-6572, PG-6077 フォーマット : Vinyl, LP, Album, Stereo,…

0 notes

Text

Live Schedule:August 2024

◇8/13(tue) 渋谷THE ROOM

密林-Afrobeat Labo-

【HOST MEMBER】

DJ:OSADASADAO

DJ:CICCI(Smile Village/スマイラゲン)

福島健一(sax)石崎忍(sax)大舘哲太(g)MZO(org)大林亮三(b)永田真毅(ds)

※当日参加メンバーに若干の変更がある場合がありますがご了承ください。

No Charge(投げ銭)+1D

◇8/16(fri) 西荻窪アケタの店

石崎忍 池戸裕太DUO

石崎忍(as)池戸裕太(g)

20:00〜23:30

¥3,000(with1D)

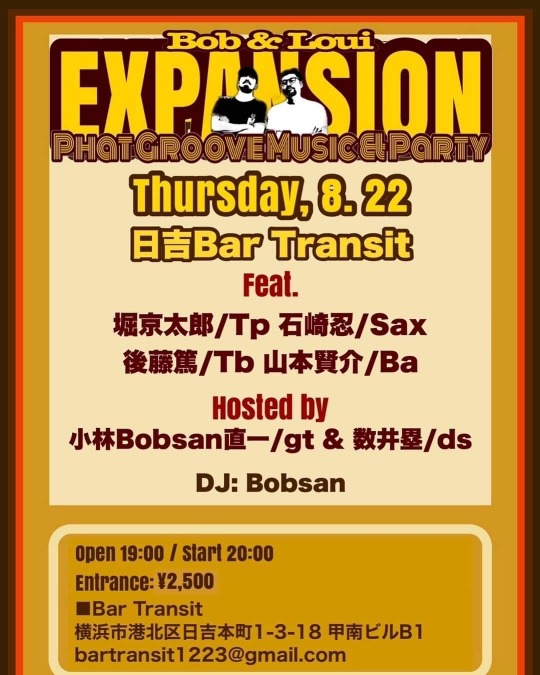

◇8/22(thu) 日吉Bar Transit

EXPANSION

Hosted by 小林Bobsan直一(gt)数井塁(ds)

Feat. 堀京太郎(tp)石崎忍(as)後藤篤(tb)山本賢介(b)

Dj Bobsan

Open 19:00 / Start 20:00

¥2,500

◇8/27(tue) 経堂Jazz Bar Crazy Love

越智巌Quartet

越智巌(g)石崎忍(as)手島甫(b)小泉高之(ds)

Open 19:00/Start 19:30〜

¥3,000

◇8/28(wed) 新宿PIT INN昼の部

ふぁいぶさくそふぉーんず

岡 勇希(ss)石崎 忍(as) 浜崎 航(ts) 福井健太(bs) 宮木謙介(bass s)

Open13:30 /Start14:00

¥1,300+税(1DRINK付)

◇8/29(thu) 桜木町JAZZ SPOT DOLPHY

石崎忍 田中信正DUO

石崎忍(as)田中信正(pf)

Open 18:30 / Start 19:30

前¥4,000/当¥4,500

0 notes

Text

Amiri Baraka’s Life-Changing Jazz Writing

By Richard Brody

January 14, 2014

I owe the late Amiri Baraka an apology, and I wish that he were here for me to tell him. A few years ago, posting about the ten books about movies that changed my life, I added a few books that aren’t about movies but that changed the way I thought about them. But I neglected to place on that list the book that, long before I had any interest in movies, definitively set for me the template for critical writing and engagement: Baraka’s book “Black Music,” a collection of his essays about modern jazz that were written between 1959 and 1967 (and that he published as LeRoi Jones).

For me, jazz started with the moderns—with “Out There,” a record by one crucial, short-lived modern, Eric Dolphy. That enthusiasm quickly engendered others. Thanks to liner notes to these records, which mentioned like-minded musicians, I started listening to John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk, Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, Albert Ayler, Sun Ra, Archie Shepp, and the musicians in their circles—and Baraka was my Virgil, my guide into the nuances of the music that obsessed me. He wrote the greatest liner notes I knew, for the thrilling live album “The New Wave in Jazz,” which I listened to with wild veneration long before I had even heard of a New Wave in movies. (Those notes are included in the book, and Baraka organized the concert that he annotated there.)

In “Black Music,” Baraka wrote with ecstasy—highly informed and intricate—about ecstatically complex music. He also revealed literary and philosophical substance in it that gave form to my inchoate experience. I learned a lot about musical form and its affect from Baraka, as when he wrote, of John Coltrane, “Not only does one seem to hear each note and sub-tone of a chord being played, but also each one of those notes shattered into half and quarter tones,” and, also, “It is like a painter who instead of painting a simple white, paints all the elemental pigments that the white contains, at the same time as the white itself.” Baraka could discuss Coltrane’s most famous recording with sophisticated love and then add, “The frighteningly limited scale of ‘My Favorite Things’ is Ancient Musik to Coleman and Taylor.” He wrote with a wide-ranging erudition, tracing influences within the history of jazz and comparing them with the lineages of other art forms. And he tossed off phrases that distilled music into lyrical language, as when he said, of the alto saxophonist John Tchicai, that “his phrasing at times reminds one of Mondrian’s geometrical decisions,” and described his playing as a “metal poem.”

The chapters in “Black Music” are occasional pieces—magazine articles and liner notes, written under the pressure of circumstances and tied to the moment—and the immediacy of experience comes through as a central part of the music itself. Baraka spent lots of time listening to live music, in clubs uptown and downtown and in the new scene of coffeehouse and loft concerts, which began in the sixties. (In the seventies, I savored the big boom of these venues and lamented their flameout.) His report on Thelonious Monk detailed the musician’s epochal six-month run with John Coltrane at the Five Spot, in 1957, and his return to the club with a new quartet featuring Charlie Rouse. His profile of the drummer Roy Haynes (who is still performing, at the age of eighty-eight) is deep with the daily cares of music-making—earning a living, dealing with the press and the public, fighting traffic to arrive on time for a gig—and with the rise of an original musical voice within a tradition and, for that matter, a career.

The life at the core of the book, which runs like a through-line from beginning to end, is the one that’s encapsulated in the very title, and it was a life that was very different from my own. Growing up nearly color-blind in nearly all-white neighborhoods, I thought of the blackness of the musicians I loved as an interesting coincidence; Baraka taught me that the music emerged from the specific experiences of blacks in America. He opens the book with the essay “Jazz and the White Critic,” which begins, “Most jazz critics have been white Americans, but most important jazz musicians have not been.” He specifically blamed the white critic—and, I understood, the white listener, such as myself—for the

Of course, when I read Dostoyevsky, Rousseau, and Plato, I knew that I was also reading books that arose from experiences utterly alien to mine—but the czar, the king, and the jury faced in those books were equally alien to me, whereas, when it came to black American life, my own implication in the conflict was inescapable. By virtue of my birth, I was on the wrong side of that fight, and yet it seemed utterly normal to me, as a white middle-class fifteen-year-old, who felt oppressed by the very comforts for which his parents struggled and by the proprieties they taught, to identify with the struggle and with the music’s spirit of liberation. Free jazz was, for me, more rock and roll than rock and roll, the ultimate headbanger music that brought philosophy to the spirit of anarchy and deep loam to the prefab rootlessness of the postwar suburb. Yet what I sought liberation from was also an inescapable part of myself, which is why Baraka’s sublime concluding flourish in the notes to “The New Wave in Jazz” spoke deeply to me: “New Black Music is this: Find the self, then kill it.” The notion seemed a most self-assertive self-abnegation, a step toward creating another, more desirable self—which was pretty much what I had in mind.

Baraka wrote early on about the power of popular black music—of Dionne Warwick, Martha Reeves and the Vandellas, and, especially, James Brown—and his vision, from 1966, of “The Rhythm and Blues mind blowing evolution of James-Ra and Sun-Brown” was utterly prescient of musical history and of my own pleasures, forecasting the plugging in and amping up of Miles Davis, most famously with “Bitches Brew.” (I listened most often to his recording “In Concert” made during a show at the Philharmonic.) Above all, Baraka—who, of course, was a poet—wrote criticism like a poet; the arm’s-length didactic authority of journalistic discourse was not for him. He was a bardic theorist who gave a musical language to music, artistic language to the experience of art.

Then came the lyric. One of the records he recommended in the brief discography at the end of his book was one of the few that featured the elusive Tchicai: an LP of the New York Art Quartet in which the saxophonist was joined by the trombonist Roswell Rudd, the bassist Lewis Worrell, and the percussionist Milford Graves, along with, on one track, Baraka himself (who, I think, was identified on the cover as Jones), reciting his poem “Black Dada Nihilismus” to accompaniment by Worrell and Graves.

His even-toned, urgent incantations got my attention as a kind of spoken-word music, but the words got my attention, too. When he referred to “the ugly silent deaths of Jews under the surgeon’s knife, to awake on Sixty-ninth Street with money and a hip nose”—well, these were my suburbs he was talking about, the nose jobs that were common coin in our realm, the money that, having not earned it, I could easily disdain. It echoed a line from “Portnoy’s Complaint”: “Ma, you want to see physical violence done to the Jews of Newark, go to the office of the plastic surgeon where the girls get their noses fixed.”

The lyrical force of his meditations was punctuated by the line “Rape the white girls, rape their fathers, cut the mothers’ throats.” The slogan of the quartet’s record label, ESP-Disk—“You Never Heard Such Sounds in Your Life”—was never more truthful. I hadn’t read (or, for that matter, looked for) discussions of these lines in the wider press. I got why they seemed unexceptionable: not for a moment did I think that Baraka was advocating such actions, not even when, toward the end, he speaks of “the murders we intend”; I was certain that he was speaking metaphorically, looking for the strongest possible image to signify the radical changes that the woeful state of American race relations demanded, the rage arising from unredressed injustice. Whether he hoped for such things was beside the point; it was enough that he could imagine them for something to silently shatter within me—the naïve belief that identities were infinitely malleable, experiences infinitely transmissible, philosophies infinitely reconcilable. There were uglinesses out there that I couldn’t fathom, not even by reading about them; in their horror I sensed, above all, a documentary element—in the lives of those who made the music I loved, there was experience that went far beyond my pleasures, my desires, my imaginings, and it wasn’t necessarily experience I wanted to have, experience of a cold and hard world out there and an agonized world within. Virgil did guide Dante, even to the last ring of Hell.

Photograph: Serge Cohen/Cosmos/Redux

#amiri baraka#on writing#jazz#jazz music#writing#article#the new yorker#new yorker#jazz writing#music

1 note

·

View note

Text

from the "Personality and temper" section of his wikipedia page:

Nearly as well known as his ambitious music was Mingus's often fearsome temperament, which earned him the nickname "the Angry Man of Jazz". His refusal to compromise his musical integrity led to many onstage eruptions, exhortations to musicians, and dismissals.[26] Although respected for his musical talents, Mingus was sometimes feared for his occasionally violent onstage temper, which was at times directed at members of his band and other times aimed at the audience.[27] He was physically large, prone to obesity (especially in his later years), and was often intimidating and frightening when expressing anger or displeasure. When confronted with a nightclub audience talking and clinking ice in their glasses while he performed, Mingus stopped his band and loudly chastised the audience, stating: "Isaac Stern doesn't have to put up with this shit."[28] Mingus destroyed a $20,000 bass in response to audience heckling at the Five Spot in New York City.[29]

Guitarist and singer Jackie Paris was a witness to Mingus's irascibility. Paris recalls his time in the Jazz Workshop: "He chased everybody off the stand except [drummer] Paul Motian and me ... The three of us just wailed on the blues for about an hour and a half before he called the other cats back."[30]

On October 12, 1962, Mingus punched Jimmy Knepper in the mouth while the two men were working together at Mingus's apartment on a score for his upcoming concert at the Town Hall in New York, and Knepper refused to take on more work. Mingus's blow broke off a crowned tooth and its underlying stub.[16] According to Knepper, this ruined his embouchure and resulted in the permanent loss of the top octave of his range on the trombone – a significant handicap for any professional trombonist. This attack temporarily ended their working relationship, and Knepper was unable to perform at the concert. Charged with assault, Mingus appeared in court in January 1963 and was given a suspended sentence. Knepper did again work with Mingus in 1977 and played extensively with the Mingus Dynasty, formed after Mingus's death in 1979.[31]

In addition to bouts of ill temper, Mingus was prone to clinical depression and tended to have brief periods of extreme creative activity intermixed with fairly long stretches of greatly decreased output, such as the five-year period following the death of Eric Dolphy.[32]

In 1966, Mingus was evicted from his apartment at 5 Great Jones Street in New York City for nonpayment of rent, captured in the 1968 documentary film Mingus: Charlie Mingus 1968, directed by Thomas Reichman. The film also features Mingus performing in clubs and in the apartment, firing a .410 shotgun indoors, composing at the piano, playing with and taking care of his young daughter Carolyn, and discussing love, art, politics, and the music school he had hoped to create.[citation needed]

who’s the jazz guy who was extremely annoying and evil to everyone he played with because he was an insane perfectionist

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Making a New Kind of Scene: New York's The Five Spot

David Brent Johnson has created a wonderful episode and essay on The Five Spot in its original Bowery location and its later St. Marks Place address. It was an amazing place that fed the contemporary arts & culture scene of New York at the time, and gave impetus to the careers of Thelonious Monk, Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman and Charles Mingus among others.

-Michael Cuscuna

Listen from Indiana Public Media… Follow: Mosaic Records Facebook Tumblr Twitter

#The Five Spot#jazz venues#Thelonious Monk#Ornette Coleman#John Coltrane#Charles Mingus#Eric Dolphy#Cecil Taylor#David Amram#Dan Wakefield#New York#Michael Cuscuna

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

舞踏家嶋田勇介とギター齋藤浩太(GLDN)のインプロユニットライブMEETING、今回は二度目の出演となるジャズピアニスト石田幹雄氏を迎えます。お楽しみに。

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

One of those albums that seems strange and arbitrary on first listen, and reveals a carefully considered structure on further listens. Eric Dolphy is my sweet spot for “out there” jazz—avant-garde, but not so “avant” that he loses me. And where else can you hear a vibraphonist intentionally cracking notes… And here’s your reminder that it’s Jazz Week on Super Friends Sunday—send me your pic by Saturday to join in! #jazzappreciationmonth #ericdolphy #jazz #jazzvinyl #vinyl #vinyladay #lp #vinyloftheday #vinyligclub #vinyljunkie #vinylcommunity #vinylcollective #instavinyl #vinylgram #recordcollector #nowspinning https://www.instagram.com/p/Ccla4RgOUX7/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#jazzappreciationmonth#ericdolphy#jazz#jazzvinyl#vinyl#vinyladay#lp#vinyloftheday#vinyligclub#vinyljunkie#vinylcommunity#vinylcollective#instavinyl#vinylgram#recordcollector#nowspinning

1 note

·

View note

Text

Various Artists — West Meets East: Indian Music And Its Influence On The West (Cherry Red Records)

youtube

Many, even most, music fans these days are aware of the influence that Indian music has had on Western musicians. From the mid-1960s onward, thanks to the Beatles, Byrds, Rolling Stones and more, listeners became accustomed to the sound of the sitar and tabla lending an “exotic” air to rock and pop music.

That wasn’t the start of Western music’s inspiration from India, however. This 3CD compilation, West Meets East, investigates earlier examples of how the intrinsic modes of Indian music were absorbed into different forms of Western music, particularly classical music and American jazz. In the latter case, especially, American (and to a lesser extent British) artists discovered that the modal style provided them exciting ways to break away from existing forms and experiment with new sounds.

Each of the three discs here includes examples of the Indian masters mixed in with the artists they inspired, and it’s almost expected that the first piece in the compilation is a raga by Ravi Shankar. By the late 1960s, Shankar was the foremost emissary of Indian music to Western listeners and musicians alike. Even before George Harrison and The Beatles brought his name to the world, he had been visiting the West since the 1930s, travelling with his brother’s band. Here, the 15-minute “Raga Sindhi Bhairavi” is, of course, marvelous. Later appearances are made by Ali Akbar Khan, whose “Evening Raga” is slower and deeper; Sharan Rani, the first woman to play the sarod, who became an important cultural ambassador; Chatur Lai, with an invigorating 18-minute tabla solo; and Ustad Vilayat Khan & Ustad Imrat Khan, whose “Rainy Season Raga” begins slowly, with almost no tabla for the first half, before the storm breaks and the players take it to great intensity. These pieces serve as opportunities to listen for the modalities, forms, and emotions that inspired the other artists featured.

And those artists include some of the greats, those who took their fellow musicians in new directions, due to their openness and appreciation for previously-unheard musical perspectives. The second and third pieces here, following Ravi Shankar’s opening, are by John Coltrane. While the Indian influence may be a little difficult to spot amidst the familiar refrain of “My Favorite Things,” “India” reveals its inspiration both in its name and the repetition which leads to exploratory flights, clearly echoing the raga form. Similarly, the Dave Brubeck Quartet’s “Calcutta Blues” also wears its influence on its sleeve, and it finds the instruments purposely focused more on melody than harmony, with a drum solo that’s particularly reminiscent of how ragas are driven by the tabla rhythms.

The second volume follows the model set by the first, opening with “Left Alone,” a slow, meandering exploration by the Eric Dolphy Quintet. There’s Ornette Coleman’s “Lonely Woman” with its unusual bass and twin brass lines, “India” from the always-experimenting Sun Ra, and a piece by Paul Horn, who was honored to be asked by Ravi Shankar to play flute on his essential 1964 album “Portrait of Genius.” Before finishing with the aforementioned “Rainy Season Raga,” we get Miles Davis’ “Milestones,” an intriguing example wherein the horns alternate percussive accents with floating solos, over a flowing rhythm that offers echoes of the first volume’s piece by Shankar.

The collection’s third volume takes a different approach, with an eclectic blend of music from flamenco to Indian film soundtracks and classical compositions. The sitar-like guitar by Gabor Szabo on “El Toro,” with the Chico Hamilton Quintet, matches the droney, accented bass, which evokes Indian styles. It’s very interesting to consider the similarity to raga shown in “Eoc Jerezanos,” by the great flamenco player Sabicas. The two pieces by Yusef Lateef show his overt adoption of Eastern styles: on “Before Dawn” in particular he goes further, playing the Egyptian arghul for a sound that was highly unusual for 1957. The inclusion of several works by the renowned Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray are quite nice, but the reason is somewhat unclear in the context of the “East Meets West” theme of the collection.

The so-called “exotica” composers of the 1950s and 1960s were naturally among those most clearly inspired by the sounds coming from the east, and none more so than Martin Denny and Les Baxter, both included here. The former’s “Moonlight on the Ganges” and the latter’s “Harem Silks from Bombay” could certainly be accused of capitalizing precisely on that “exoticness,” but it must be admitted that the music is wears its inspiration honestly and, particularly in the case of Baxter’s orchestra, is quite well-played.

The last half of the third volume takes a bit of a left turn to focus on composers such as Benjamin Britten, Maurice Ravel, Claude Debussy and Béla Bartók. Indian inspiration shows in Ravel’s use of woodwinds in “Little Ugly Girl,” and the meandering, melodic piano in “Ondine.” Debussy, after hearing Indonesian gamelan music for the first time, was inspired to create pieces like “Pagodes,” included here, with piano notes juxtaposed and overlaid in previously-unheard ways. Several pieces from Maurice Delage’s 1952 “Quatre poèmes Hindous” showcase the use of sitar and “exotic” styles.

The collection comes with an extensive booklet offering quotes, historical details and discography information for the artists included, but it would have benefited from more context-setting and drawing lines between people and their works. The focus on jazz in the first two volumes helps, while the third volume feels more scattered and somewhat hurried. It’s possible that shorter pieces would have allowed for more breadth — many of the works here exceed the ten or even 20-minute mark — although, of course, changes in the music over time is one of the characteristics being examined.

West Meets East explores a worthwhile and rewarding subject, and the three discs include some terrific music, so at the very least this collection offers some fine listening. Making connections between works by such jazz greats as Coltrane, Brubeck, Dolphy, Coleman, Davis and the great Indian artists provides for enjoyable critical listening as well. The classical and more eclectic offerings can be considered a bonus.

#Indian Music And Its Influence On The West#cherry red#mason jones#albumreview#dusted magazine#box set#raga#sitar#tabla#ravi shankar#ali akbar khan#john coltrane#eric dolphy#miles davis#west meets east

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mingus: Charles Mingus with Charles McPherson and Eric Dolphy at The Five Spot, NYC - 1962 https://t.co/5NcK7CkeRv

Mingus: Charles Mingus with Charles McPherson and Eric Dolphy at The Five Spot, NYC - 1962 pic.twitter.com/5NcK7CkeRv

— Modern Jazz Daily (@ModernJazzDaily) February 24, 2020

from Twitter https://twitter.com/ModernJazzDaily February 24, 2020 at 05:22PM via IFTTT

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

11/22 おはようございます。Gil Scott Heron / Spirits tvt4310 等更新しました。

Henny Vonk / Rebootin Sjp164 Steve Lacy / Soprano Sax prlp7125 Sonny Criss / This is Criss Pr7511 Eric Dolphy / at Five Spot vol2 Prst7826 Eric Dolphy / Last Date Lm82013 Joe Viera Gerhard Laber / Kontraste cal30619 Boris Vian / En Avant La Zizique Sh10002 Andre Benichou / Jazz Guitar Bach h71069 Candido / Thousand Finger Man - Rock & Shuffle rhr3464 Candido / Jingo - Dancin and Pracin sg219 Hot Cuisine / Live My Life - Who's Been Kissing You krla121105 Dino Terrell / You Can Do It NIR1122 Gap Band / I Found My Baby Ted1-2613 Gil Scott Heron / Spirits tvt4310 Billy Cole / Woman DBLP021

~bamboo music~

530-0028 大阪市北区万歳町3-41 シロノビル104号

06-6363-2700

0 notes