#j.b. priestley

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

They Came to a City (1944)

[letterboxd | imdb | tubi (US)]

Director: Basil Deardon

Cinematographer: Stan Pavey

Performers: Mabel Terry-Lewis, Ada Reeve, Renee Gadd, Raymond Huntley, Googie Withers, Norman Shelley, Fanny Rowe, John Clements, & A.E. Matthews

#1940s#1944#Basil Dearden#j.b. priestley#Googie Withers#british film#my edits#film stills#film#classic film#classic movies#classic cinema#cinematography#cinema#classicfilmblr

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Delight by J.B. Priestley

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

AUTHOR EXTRAORDINAIRE

'If you are a genius, you'll make your own rules, but if not - and the odds are against it - go to your desk no matter what your mood, face the icy challenge of the paper - write.'

'A novelist who writes nothing for 10 years finds his reputation rising. Because I keep on producing books they say there must be something wrong with this fellow.'

'If there is one thing left that I would like to do, it's to write something really beautiful. And I could do it, you know. I could still do it.'

'Much of writing might be described as mental pregnancy with successive difficult deliveries.'

'Write as often as possible, not with the idea at once of getting into print, but as if you were learning an instrument.'

Author Extraordinaire J. B. Priestley

#j.b. priestley#author extraordinaire#writblr#writing advice#writing inspiration#literature#books#quotes#wise words

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

(1929) The Good Companions, J.B. Priestley. 08/06/2024 - 21/06/2024

First time reading? Yes

Rating: 2/10

Didn't actually finish this, got about 450 pages in before calling it quits. The one thing I liked about this book was the Yorkshire accents (which I think it's famous for?) but even then sometimes they were fully incoherent and I had to reread the line multiple times before I understood it. Jesiah Oakroyd was probably my favourite character, working class labourer from Yorkshire who is anti-union - probably something interesting to say there but I was not invested enough in the story to think too much on it. Priestley loves using the word 'ejaculated' to describe men talking & loves using racial slurs completely out of the blue. The dressmaker's name being Miss Thong made me laugh but I don't think it was intentional. Best thing in all the pages I read was Oakroyd explaining how to make a proper Yorkshire pudding. Very slow and boring book, do not understand how this is one of Priestley's most famous works. Would not recommend.

1 note

·

View note

Text

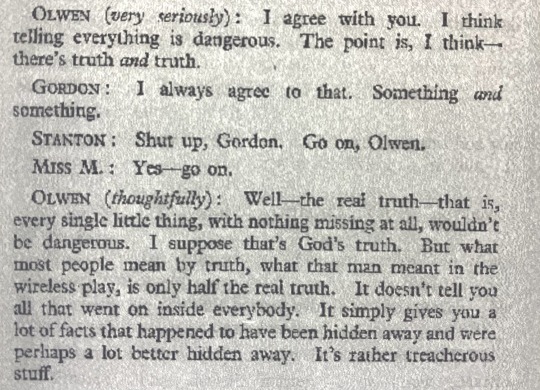

Act I - Dangerous Corners

‘Three Time Plays’ - J.B. Priestley

0 notes

Text

Science and the unconscious

In the preceding chapters C. G. Jung and some of his associates have tried to make clear the role played by the symbol-creating function in man’s unconscious psyche and to point out some fields of application in this newly discovered area of life. We are still far from understanding the unconscious or the archetypes — those dynamic nuclei of the psyche — in all their implications. All we can see now is that the archetypes have an enormous impact on the individual, forming his emotions and his ethical and mental outlook, influencing his relationships with others, and thus affecting his whole destiny. We can also see that the arrangement of archetypal symbols follows a pattern of wholeness in the individual, and that an appropriate understanding of the symbols can have a healing effect. And we can see that the archetypes can act as creative or destructive forces in our mind: creative when they inspire new ideas, destructive when these same ideas stiffen into conscious prejudices that inhibit further discoveries.

Jung has shown in his chapter how subtle and differentiated all attempts at interpretation must be, in order not to weaken the specific individual and cultural values of archetypal ideas and symbols by leveling them out- - i.e. by giving them a stereotyped, intellectually formulated meaning. Jung himself dedicated his entire life to such investigations and interpretative work; naturally this book sketches only an infinitesimal part of his vast contribution to this new field of psychological discovery. He was a pioneer and remained fully aware that an enormous number of further questions remained unanswered and call for further investigation. This is why his concepts and hypotheses are conceived on as wide a basis as possible (without making them too vague and all-embracing) and why his views form a so-called “open system” that does not close the door against possible new discoveries.

To Jung, his concepts were mere tools or heuristic hypotheses that might help us to explore the vast new area of reality opened up by the discovery of the unconscious— a discovery that has not merely widened our whole view of the world but has in fact doubled it. We must always ask now whether a mental phenomenon is conscious or unconscious and, also, whether a “real” outer phenomenon is perceived by conscious or unconscious means.

The powerful forces of the unconscious most certainly appear not only in clinical material but also in the mythological, religious, artistic, and all the other cultural activities by which man expresses himself. Obviously, if all men have common inherited patterns of emotional and mental behavior (which Jung called the archetypes), it is only to be expected that we shall find their products (symbolic fantasies, thoughts, and actions) in practically every field of human activity.

Important modern investigations of many of these fields have been deeply influenced by Jung’s work. For instance, this influence can be seen in the study of literature, in such books as J. B. Priestley’s Literature and Western Man, Gottfried Diener’s Fausts Weg zu Helena, or James Kirsch’s Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Similarly, Jungian psychology has contributed to the study of art, as in the writings of Herbert Read or of Aniela Jaffe, Erich Neumann’s examination of Henry Moore, or Michael Tippett’s studies in music. Arnold Toynbee’s work on history and Paul Radin’s on anthropology have benefited from Jung’s teachings, as have the contributions to sinology made by Richard Wilhelm, Enwin Rousselle, and Manfred Porkert.

Of course, this does not mean that the special features of art and literature (including their interpretations) can be understood only from their archetypal foundation. These fields all have their own laws of activity; like all really creative achievements, they cannot ultimately be rationally explained. But within their areas of action one can recognize the archetypal patterns as a dynamic background activity. And one can often decipher in them (as in dreams) the message of some seemingly purposive, evolutionary tendency of the unconscious.

The fruitfulness of Jung’s ideas is more immediately understandable within the area of the cultural activities of man: Obviously, if the archetypes determine our mental behavior, they must appear in all these fields. But, unexpectedly, Jung’s concepts have also opened up new ways of looking at things in the realm of the natural sciences as well—for instance, in biology.

The physicist Wolfgang Pauli has pointed out that, due to new discoveries, our idea of the evolution of life requires a revision that might take into account an area of interrelation between the unconscious psyche and biological processes. Until recently it was assumed that the mutation of species happened at random and that a selection took place by means of which the “meaningful,” well-adapted varieties survived, and the others disappeared. But modern evolutionists have pointed out that the selections of such mutations by pure chance would have taken much longer than the known age of our planet allows.

Jung’s concept of synchronicity may be helpful here, for it could throw light upon the occurrence of certain rare “border-phenomena,” or exceptional events; thus it might explain how “meaningful” adaptations and mutations could happen in less time than that required by entirely random mutations. Today we know of many instances in which meaningful “chance” events have occurred when an archetype is activated. For example, the history of science contains many cases of simultaneous invention or discovery. One of the most famous of such cases involved Darwin and his theory of the origin of species: Darwin had developed the theory in a lengthy essay, and in 1844 was busy expanding this into a major treatise.

While he was at work on this project he received a manuscript from a young biologist, unknown to Darwin, named A. R. Wallace. The manuscript was a shorter but otherwise parallel exposition of Darwin’s theory. At the time Wallace was in the Molucca Islands of the Malay Archipelago. He knew of Darwin as a naturalist, but had not the slightest idea of the kind of theoretical work on which Darwin was at the time engaged.

In each case a creative scientist had independently arrived at a hypothesis that was to change the entire development of the science. And each had initially conceived of the hypothesis in an intuitive “flash” (later backed up by documentary evidence). The archetypes thus seem to appear as the agents, so to speak, of a creatio continua. (What Jung calls synchronistic events are in fact something like “acts of creation in time.”)

Similar “meaningful coincidences” can be said to occur when there is a vital necessity for an individual to know about, say, a relative’s death, or some lost possession. In a great many cases such information has been revealed by means of extrasensory perception. This seems to suggest that abnormal random phenomena may occur when a vital need or urge is aroused; and this in turn might explain why a species of animals, under great pressure or in great need, could produce “meaningful” (but acausal) changes in its outer material structure.

But the most promising field for future studies seems (as Jung saw it) to have unexpectedly opened up in connection with the complex field of microphysics. At first sight, it seems most unlikely that we should find a relationship between psychology and microphysics. The interrelation of these sciences is worth some explanation.

The most obvious aspect of such a connection lies in the fact that most of the basic concepts of physics (such as space, time, matter, energy, continuum or field, particle, etc.) were originally intuitive, semi-mythological, archetypal ideas of the old Greek philosophers — ideas that then slowly evolved and became more accurate and that today are mainly expressed in abstract mathematical terms. The idea of a particle, for instance, was formulated by the fourth-century B.C. Greek philosopher Leucippus and his pupil Democritus, who called it the “atom” i.e. the “indivisible unit.” Though the atom has not proved indivisible, we still conceive matter ultimately as consisting of waves and particles (or discontinuous “quanta”).

The idea of energy, and its relationship to force and movement, was also formulated by early Greek thinkers, and was developed by Stoic philosophers. They postulated the existence of a sort of life-giving “tension” (tonos), which supports and moves all things. This is obviously a semi-mythological germ of our modern concept of energy.

Even comparatively modern scientists and thinkers have relied on half-mythological, archetypal images when building up new concepts. In the 17th century, for instance, the absolute validity of the law of causality seemed “proved” to Rene Descartes “by the fact that God is immutable in His decisions and actions.” And the great German astronomer Johannes Kepler asserted that there are not more and not less than three dimensions of space on account of the Trinity.

These are just two examples among many that show how even our modern and basic scientific concepts remained for a long time linked with archetypal ideas that originally came from the unconscious. They do not necessarily express “objective” facts (or at least we cannot prove that they ultimately do) but spring from innate mental tendencies in man — tendencies that induce him to find “satisfactory” rational explanatory connections between the various outer and inner facts with which he has to deal. When examining nature and the universe, instead of looking for and finding objective qualities, “man encounters himself,” in the phrase of the physicist Werner Heisenberg.

Because of the implications of this point of view, Wolfgang Pauli and other scientists have begun to study the role of archetypal symbolism in the realm of scientific concepts. Pauli believed that we should parallel our investigation of outer objects with a psychological investigation of the inner origin of our scientific concepts. (This investigation might shed new light on a far-reaching concept to be introduced later in this chapter - the concept of a “one-ness” between the physical and psychological spheres, quantitative and qualitative aspects of reality).

Besides this rather obvious link between the psychology of the unconscious and physics, there, are other even more fascinating connections. Jung (working closely with Pauli) discovered that analytical psychology has been forced by investigations in its own field to create concepts that turned out later to be strikingly similar to those created by the physicists when confronted with microphysical phenomena. One of the most important among the physicists’ concepts is Niels Bohr’s idea of complementarity.

Modern microphysics has discovered that one can describe light only by means of two logically opposed but complementary concepts: The ideas of particle and wave. In grossly simplified terms, it might be said that under certain experimental conditions light manifests itself as if it were composed of particles; under others, as if it were a wave. Also, it was discovered that we can accurately observe either the position or the velocity of a subatomic particle - but not both at once. The observer must choose his experimental set-up, but by doing so he excludes (or rather must “sacrifice”) some other possible setup and its results. Furthermore, the measuring apparatus has to be included in the description of events because it has a decisive but uncontrollable influence upon the experimental set-up.

Pauli says: “The science of microphysics, on account of the basic ‘complementary’ situation, is faced with the impossibility of eliminating the effects of the observer by determinable correctives and has therefore to abandon in principle any objective understanding of physical phenomena. Where classical physics still saw ‘determined causal natural laws of nature’ we now look only for ‘statistical laws’ with ‘primary possibilities’.”

In other words, in microphysics the observer interferes with the experiment in a way that cannot be measured and that therefore cannot be eliminated. No natural laws can be formulated, saying “such-and-such will happen in every case.” All the microphysicist can say is “such-and-such is, according to statistical probability, likely to happen.” This naturally represents a tremendous problem for our classical physical thinking. It requires a consideration, in a scientific experiment, of the mental outlook of the participant-observer: It could thus be said that scientists can no longer hope to describe any aspects of outer objects in a completely “objective” manner.

Most modern physicists have accepted the fact that the role played by the conscious ideas of an observer in every microphysical experiment cannot be eliminated; but they have not concerned themselves with the possibility that the total psychological condition (both conscious and unconscious) of the observer might play a role as well. As Pauli points out, however, we have at least no a priori reasons for rejecting this possibility. But we must look at this as a still unanswered and an unexplored problem.

Bohr’s idea of complementarity is especially interesting to jungian psychologists, for Jung saw that the relationship between the conscious and unconscious mind also forms a complementary pair of opposites. Each new content that comes up from the unconscious is altered in its basic nature by being partly integrated into the conscious mind of the observer. Even dream contents (if noticed at all are in that way semi-conscious. And each enlargement of the observer’s consciousness caused by dream interpretation has again an immeasurable repercussion and influence on the unconscious. Thus the unconscious can only be approximately described (like the particles of microphysics) by paradoxical concepts. What it really is “in itself” we shall never know, just as we shall never know this about matter.

To take the parallels between psychology and microphysics even further: What Jung calls the archetypes (or patterns of emotional and mental behavior in man) could just as well be called, to use Pauli’s term, “primary possibilities” of psychic reactions. As has been stressed in this book, there are no laws governing the specific form in which an archetype might appear. There are only “tendencies” (see p. 67) that, again, enable us to say only that such-and-such is likely to happen in certain psychological situations.

As the American psychologist William James once pointed out, the idea of an unconscious could itself be compared to the “field” concept in physics. We might say that, just as in a magnetic field the particles entering into it appear in a certain order, psychological contents also appear in an ordered way within that psychic area which we call the unconscious. If we call something “rational” or “meaningful” in our conscious mind, and accept it as a satisfactory “explanation” of things, it is probably due to the fact that our conscious explanation is in harmony with some preconscious constellation of contents in our unconscious.

In other words, our conscious representations are sometimes ordered (or arranged in a pattern) before they have become conscious to us. The 19th-century German mathematician Karl Friedrich Gauss gives an example of an experience of such an unconscious order of ideas: He says that he found a certain rule in the theory of numbers “not by painstaking research, but by the Grace of God, so to speak. The riddle solved itself as lightning strikes, and I myself could not tell or show the connection between what I knew before, what I last used to experiment with, and what produced the final success.” The French scientist Henri Poincare is even more explicit about this phenomenon; he describes how during a sleepless night he actually watched his mathematical representations colliding in him until some of them “found a more stable connection. One feels as if one could watch one’s own unconscious at work, the unconscious activity partially becoming manifest to consciousness without losing its own character. At such moments one has an intuition of the difference between the mechanisms of the two egos.”

As a final example of parallel developments in microphysics and. psychology, we can consider Jung’s concept of meaning. Where before men looked for causal (i.e. rational) explanations of phenomena, Jung introduced the idea of looking for the meaning (or, perhaps we could say, the “purpose”). That is, rather than ask why something happened (i.e. what caused it), Jung asked: What did it happen for? This same tendency appears in physics: Many modern physicists are now looking more for “connections” in nature than for causal laws (determinism).

Pauli expected that the idea of the unconscious would spread beyond the “narrow frame of therapeutic use” and would influence all natural sciences that deal with general life phenomena. Since Pauli suggested this development he has been echoed by some physicists who are concerned with the new science of cybernetics— the comparative study of the “control” system formed by the brain and nervous system and such mechanical or electronic information and control systems as computers. In short, as the modern French scientist Oliver Costa de Beauregard has put it, science and psychology should in future “enter into an active dialogue.”

The unexpected parallelisms of ideas in psychology and physics suggest, as Jung pointed out, a possible ultimate one-ness of both fields of reality that physics and psychology study—i.e. a psychophysical one-ness of all life phenomena. Jung was even convinced that what he calls the unconscious somehow links up with the structure of inorganic matter—a link to which the problem of so-called “psychosomatic” illness seems to point. The concept of a Unitarian idea of reality (which has been followed up by Pauli and Erich Neumann) was called by Jung the unus mundus (the one world, within which matter and psyche arc not yet discriminated or separately actualized). He paved the way toward such a Unitarian point of view by pointing out that an archetype shows a “psychoid” (i.e. not purely psychic but almost material) aspect when it appears within a synchronistic event — for such an event is in effect a meaningful arrangement of inner psychic, and outer facts.

In other words, the archetypes not only fit into outer situations (as animal patterns of behavior fit into their surrounding nature); at bottom they tend to become manifest in a synchronistic “arrangement” that includes both matter and psyche. But these statements are just hints at some directions in which the investigation of life phenomena might proceed. Jung felt that we should first learn a great deal more about the interrelation of these two areas (matter and psyche) before rushing into too many abstract speculations about it.

The field that Jung himself felt would be most fruitful for further investigations was the study of our basic mathematical axiomata—which Pauli calls “primary mathematical intuitions,” and among which he especially mentions the ideas of an infinite series of numbers in arithmetic, or of a continuum in geometry, etc. As the German-born author Hannah Arendt has said, “with the rise of modernity, mathematics do not simply enlarge their content or reach out into the infinite to become applicable to the immensity of an infinite and infinitely growing, expanding universe, but cease to be concerned with appearance at all. They are no longer the beginnings of philosophy, or the ‘science’ of Being in its true appearance, but become instead the science of the structure of the human mind.” (A Jungian would at once add the question: Which mind? The conscious or the unconscious mind?)

As we have seen with reference to the experiences of Gauss arid Poincare, the mathematicians also discovered the fact that our representations are “ordered” before we become aware of them. B. L. van der Waerden, who cites many examples of essential mathematical insights arising from the unconscious, concludes: “...the unconscious is not only able to associate and combine, but even to judge. The judgment of the unconscious is an intuitive one, but it is under favorable circumstances completely sure.”

Among the many mathematical primary intuitions, or a priori ideas, the “natural numbers” seem psychologically the most interesting. Not only do they serve our conscious everyday measuring and counting operations; they have for centuries been the only existing means for “reading” the meaning of such ancient forms of divination as astrology, numerology, geomancy, etc.—all of which are based on arithmetical computation and all of which have been investigated by Jung in terms of his theory of synchronicity. Furthermore, the natural numbers — viewed from a psychological angle — must certainly be archetypal representations, for we are forced to think about them in certain definite ways. Nobody, for instance, can deny that 2 is the only existing even primary number, even if he has never thought about it consciously before. In other words, numbers are not concepts consciously invented by men for purposes of calculation: They are spontaneous and autonomous products of the unconscious — as are other archetypal symbols.

But the natural numbers are also qualities adherent to outer objects: We can assert and count that there are two stones here or three trees there. Even if we strip outer objects of all such qualities as color, temperature, size, etc., there still remains their “many-ness” or special multiplicity. Yet these same numbers are also just as indisputably parts of our own mental set-up — abstract concepts that we can study without looking at outer objects. Numbers thus appear to be a tangible connection between the spheres of matter and psyche. According to hints dropped by Jung, it is here that the most fruitful field of further investigation might be found.

I mention these rather difficult concepts briefly in order to show that, to me, Jung’s ideas do not form a “doctrine” but are the beginning of a new outlook that will continue to evolve and expand. I hope they will give the reader a glimpse into what seems to me to have been essential to and typical of Jung’s scientific attitude. He was always searching, with unusual freedom from conventional prejudices, and at the same time with great modesty and accuracy, to understand the phenomenon of life. He did not go further into the ideas mentioned above, because he felt that he had not yet enough facts in hand to say anything relevant about them—just as he generally waited several years before publishing his new insights, checking them again and again in the meantime, and himself raising every possible doubt about them.

Therefore, what might at first sight strike the reader as a certain vagueness in his ideas comes in fact from this scientific attitude of intellectual modesty -an attitude that does not exclude (by rash, superficial pseudo-explanations and oversimplifications) new possible discoveries, and that respects the complexity of the phenomenon of life. For this phenomenon was always an exciting mystery to Jung. It was never, as it is for people with closed minds, an “explained” reality about which it can be assumed that we know everything.

Creative ideas, in my opinion, show their value in that, like keys, they help to “unlock” hitherto unintelligible connections of facts and thus enable man to penetrate deeper into the mystery of life. I am convinced that Jung’s ideas can serve in this way to find and interpret new facts in many fields of science (and also of everyday life), simultaneously leading the individual to a more balanced, more ethical, and wider conscious outlook. If the reader should feel stimulated to work further on the investigation and assimilation of the unconscious— which always begins by working on oneself — the purpose of this introductory book would be fulfilled.

--Marie-Louise Von Franz en "Man and his Symbols"

#Carl Jung#man and his symbols#marie louise von franz#unconscious#J.B. Priestley#Gottfried Diener#Literature and Western Man#Faust Weg zu Helena#James Kirsch#Shakespeare's Hamlet#Michel Tippett#Arnold Toynbee#Paul Radin#Richard Wilhelm#Enwin Rousselle#Manfred Porkert#Wolfgang Pauli#Charles Darwin#A.R. Wallace#Leucippus#Democritus#Rene Descartes#Johannes Kepler#Werner Heisenberg#Niels Bohr#William James#Karl Friedrich Gauss#Henri Poincare#Oliver Costa de Beauregard#Erich Neumann

1 note

·

View note

Note

Hey Jon! Looking for a bit of writing advice since you seem to be pretty good at this- How do you write metaphors without being too on the nose? It’s something I’m struggling with at the moment. Thanks!

I'm probably not the right person to ask this question because I have very strong and specific opinions.

When we talk about metaphors being too on-the-nose, I think we're really saying one of three things.

It's too obvious in the sense that it's been done before (e.g. an oppressed fantasy race being used as a catch-all metaphor for real-life marginalised peoples)

It's too obvious in the sense that it's offputtingly reductive and over-simple, either in terms of making the story and characters feel real, or as a tasteless misrepresentation of the issue it aims to address (e.g. an oppressed fantasy race being used as a catch-all metaphor for real-life marginalised peoples).

A century's worth of establishment critical analysis attempting to make sense of modernism and post-modernism has made us all hopeless idiots who believe an allegory is invariably no good unless it's buried deep in complex referentiality and can only be retrieved with months of study. (e.g. a very timely example - J.B. Priestley's An Inspector Calls, where the author uses the format of the detective mystery to address the role of the super-wealthy in social murder and make the case that it is every bit as real as lawless murder, is extremely on the nose! It's taught in schools because the message is very clearly spelled out! But that's exactly what it needs to be and it would not be better if it was subtler! Being on the nose means you've landed the punch!)

So for me there is no broad-brush answer, it depends very much on the position and role of your metaphor in the story (and so this answer is probably useless, again, without knowing the specifics). I'd begin by asking yourself the same question on two fronts: where does the metaphor take me next?

As the writer, does the metaphor give me more to play with, or is it entrapping me into an over-familiar structure or tropes? A much-discussed 'bad metaphor' right now is horror movies where the monster is Trauma...which then blocks the narrative into a predictable corner where the hero inevitably has to cathartically overcome the Trauma or it'll send the wrong message.

Correspondingly, as an audience member, once I grasp the metaphor, what am I going to feel other than 'oh, I get it?' Children of Men is too direct and on-the-nose to even be considered an allegory. Its extremely unsubtle and one-note depiction of a monstrous near-future Britain that's forcibly rounding up refugees fills me nonetheless with powerful emotion - with terror, with unease, with anger, with a faint hope in the kindness of strangers. But that's in the immense strength of its characters, its careful observation, and its tense action to make me care. By comparison, when a fantasy story has human bigots locking up impoverished nomadic elves or what-have-you, I usually feel absolutely nothing, not because it's too fantastical, but because the writer doesn't have any genuine insights or depth of empathy for the issue or the (in)humanity involved, and is instead just using the metaphor as a piece of worldbuilding shorthand to signal to the audience who is good and who is bad. (Some writers will then attempt to gussy up the metaphor by introducing moral complexity - oh, no, the elves have stabbed a random innocent human! - but this doesn't actually improve anything, it only makes the parallel ever more tasteless.)

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

A not unpleasant melancholy, touched with autumnal beauty, invaded his mind. -- J.B. Priestley

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

They Came to a City (1944)

[letterboxd | imdb | tubi (US)]

Director: Basil Deardon

Cinematographer: Stan Pavey

Performers: Mabel Terry-Lewis, Fanny Rowe, Norman Shelley, John Clements, Googie Withers, Ada Reeve, A.E. Matthews, Renee Gadd & Raymond Huntley

#1940s#1944#Basil Dearden#j.b. priestley#googie withers#british film#my edits#film#film stills#classic film#classic movies#classic cinema#cinematography#cinema#classicfilmblr

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

"We pay when old for the excesses of youth"

- J.B. Priestley

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay, time for MY headcanons about the YJs' taste in books

Shauna: Canonically likes Kurt Vonnegut. Perhaps other satirical novelists like Evelyn Waugh, Joseph Heller, and Bret Easton Ellis. Likeliest YJ character to have actually read and enjoyed Lord of the Flies, but took the wrong lessons from it. Reads lots of feminist nonfiction but little feminist fiction. Jackie: Not much of a reader. Naturally gravitates towards "airport"/"beach" novels but can be sold on somewhat meatier literature with aesthetic and genre qualities that are similar, like Daphne du Maurier's body of work and, in a pinch, Wuthering Heights. Lottie: I think she would like the kind of Asian Christian fiction that becomes popular-ish in the West. Silence, The Martyred, that sort of book. Genuinely enjoys paradigmatic "school study" novels like The Great Gatsby, East of Eden, and the like. Claims to have read more Dostoyevsky than she has, but has at least read White Nights and The Idiot. Unlike Nat, knows who Mishima Yukio is but refuses to read anything by him. Nat: Is a Hunter S. Thompson girlie. Unlike Lottie, has read at least one Mishima novel but doesn't know anything about him. Taissa: Mostly reads nonfiction related to her philosophical, political, and historical interests. Lots of Eric Foner, Lillian Faderman, W.E.B. Du Bois, law reviews, weirdo economists (affectionate) like Henry George and E.F. Schumacher, maybe some British commentators on land issues like William Cobbett, J.B. Priestley, and Oliver Rackham. Van: The only big "genre" reader. Has read a fair amount of Tolkien; was into Terry Brooks for a while; really enjoys feminist and lesbian fantasy and science fiction; felt betrayed about Marion Zimmer Bradley but, conversely, doesn't like Anne Rice nearly as much as... Misty: Likes Anne Rice more than Van does. Likes Anne Rice more than MOST people do. Canonically reads Nora Roberts. Would have a worrying amount of overlap in taste with a living, forty-three-year-old Jackie. Laura Lee: Was born to read the Locked Tomb books behind her parents' backs, heavily annotating all the Biblical quotes and paraphrases and having big feelings over Mercymorn and Cristabel. Unfortunately, was born too early for that, and did the equivalent with Brideshead Revisited instead. Was mortified when Shauna mixed up Laura Lee's copy of Brideshead with her own and almost brought it home with her one day. Enjoys Victorian poetry like Rossetti and Hopkins. Akilah: Really into the kind of older children's literature that is written in an erudite enough way that it is now read mostly by teenagers and adults, like L.M. Montgomery and Elizabeth Goudge. Mari: Born to read Otherside Picnic, forced to read the first Animorphs book over and over after stealing it from a younger relative eighteen hours before the crash.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Negotiating Transatlantic Stardom: Julie Andrews in Everywoman, May 1956

By early 1956, Julie Andrews was firmly on the path to international stardom. Her New York debut in The Boy Friend (1954��55) had made her the "Toast of Broadway," and her latest role as Eliza Doolittle in My Fair Lady, hailed as "the musical of the century," was set to elevate her fame even further.

Back home in the UK, commentators were quick to celebrate the US success of "our Julie" as a source of national pride. This fascinating two-page celebrity spread in Everywoman—compiled while Julie was home on a Christmas hiatus between shows and published in the magazine's May 1956 issue—captures a pivotal moment in the evolution of her public image in Britain (Lincoln 1956).

From the outset, the article frames Julie’s celebrity in emphatically nationalist terms. Its very title, The Lass With the Delicate Air—a reference to the famed British folk song (and, incidentally, later the title track of Julie’s first solo LP)—positions her as an emblem of English heritage. This nationalist coding is further reinforced through descriptions that variously cast Julie as 'Broadway’s English star' and "a delicate English rose" (p. 52).

The article sustains this image by attributing to Julie a familiar repertoire of classic British virtues—modesty, middle-class reserve, and plucky pragmatism. She is portrayed as "charming" but "without gimmicks," thoughtful and polite: "she concentrates when you ask her a question, pauses reflectively a moment, then answers without affectation or coyness" (p. 53). She is also grounded and disciplined—"unsensationally businesslike"—approaching everything with "her usual seriousness and application" (p. 52).

Yet alongside this warming portrait of hegemonic Englishness, the article also acknowledges elements of novelty and transformation. Julie’s "long brown childlike bob" has become "a sleek, centre-parted cap style" (p. 52); she has exchanged her "beret and schoolgirlish coat" for "full-skirted dresses and American-style sports clothes"; and she has "cultivated the American taste for steaks and fruit" (p. 53).

While these details position her within a more cosmopolitan, modernised femininity, the article simultaneously reassures readers that she remains steadfastly loyal to her homeland. She may "enchant… everyone both sides of the Atlantic," but "the loneliness of New York" leaves her "terribly homesick" (p. 52). "I wish I could spend six months of the year in America and the other six in England," she confesses longingly (p. 53).

This careful balancing act—celebrating Julie’s American success while reaffirming her enduring Englishness—takes on heightened significance when viewed in the broader postwar context. The 1950s were a period of profound transformation in Britain as the nation adjusted to a shifting global order (Catterall & Obelkevich 1994). The United States had emerged as the dominant superpower, and its cultural and economic influence expanded rapidly, flooding British markets with American products, fashions, and entertainment. This influx fuelled widespread anxiety over what many saw as an accelerating cultural Americanisation. "America is now the great invader," huffed British writer J.B. Priestley in 1955 (cited in Lyons 2013, p. 7).

Amidst these anxieties, the framing of Julie’s expanded celebrity had to walk a rhetorical tightrope—embracing the glamour of her transatlantic success without undermining the sense of her enduring Englishness. One of the ways in which the article negotiates this tension is through a recurring Cinderella theme—a classic motif of celebrity discourse and one central to Julie’s early stardom. Her journey from an ordinary English girl with 'buck teeth' to the 'Toast of Broadway' mirrors a fairytale transformation, positioning her as both relatable and exceptional, English and international—a perfect synthesis for a public icon of the era.

The Cinderella metamorphosis is also spelled out visually in the accompanying selection of press photos of Julie across the years. There is Juvenile Julie, a gangly 13-year-old schoolgirl, all fidgety fingers as she gazes intently into the eyes of Danny Kaye—and, perhaps, her own as-yet-unrealised future of American stardom. Then there is Homely Julie, lovingly framed with her brothers in the diamond-leaded window of their suburban Surrey home or practising at the family piano with her mother. Finally, there is Transatlantic Star Julie—striking a theatrical pose in an armchair, gazing at her poised reflection in a Hollywood-style dressing room mirror, or dressed in character as she takes her place on the New York stage alongside the established stardom of Rex Harrison.

This interplay of imagery, narrative, and cultural positioning ultimately serves a primary commercial function: celebrity-mediated promotion. Like many magazines of its era, Everywoman catered to the booming postwar market of female readers through an aspirational mix of idealised domesticity, beauty culture, and consumerist lifestyle. With sections dedicated to home-making, fashion, beauty, and family affairs, the magazine was also filled with colourful advertising for everything from fashion and cosmetics to grocery items, white goods, and cleaning products. In doing so, Everywoman worked to socialise its largely lower-middle-class readership into the moral and material imperatives of global postwar consumerism (Walker 1998).

Understood in these terms, Julie’s Cinderella transformation functions not just as a fairytale idyll but as an instructive model of self-fashioning, reinforcing postwar ideals of commodified femininity and aspirational consumption. Framed explicitly as a beauty story, her rise to stardom becomes a journey of discipline and self-improvement, one extending beyond talent to the meticulous cultivation of beauty. Whether perfecting her makeup or refining her wardrobe, Julie approaches her appearance with the same no-nonsense effort she applies to her craft. Her willingness to learn—from the sage counsel of a Fairy Godmother-like Beauty Counselor, no less—embodies the magazine’s ethos of achievable glamour, where self-discipline and refinement lead to transformation.

By blending the extraordinary with the accessible, the Everywoman article presents Julie’s success as both aspirational and instructive, reinforcing the postwar belief that discipline, charm, and the right consumer choices could shape one’s destiny. At the same time, it resolves tensions between British identity and American influence by portraying "our Julie" as both triumphant abroad and steadfastly English at heart.

Sources:

Catterall, P. & Obelkevich, J. (1994). Understanding post-war British society. Routledge.

Lincoln, N. (1956, May). Julie Andrews: The lass with the delicate air. Everywoman. 17(195). pp. 52-53.

Lyons, J.F. (2013). America in the British imagination, 1945 to the present. Palgrave Macmillan. Walker, N. (Ed.). (1998). Women's magazines, 1940-1960: Gender roles and the popular press. Bedford Press.

© 2025, Brett Farmer. All Rights Reserved.

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

7 & 11!

Sorry for only just answering this, I just saw it! I'm assuming it's for the not USAmerican asks, so I'll do those.

7. Favourite words from your native language that you like the most? Obviously I can't do this one too well as a Br*tish person but I'll do my three favourite words we have in British English that aren't really a thing in American English: 'wank' i think everyone knows ofc, but I also love 'knackered' to mean tired or worn out and 'plonker' to mean idiot. Idk onomatopoeic words like those are fun imo. I should also acknowledge my favourite word of Welsh given it's kind of an indigenous language of the UK- 'heddlu', which means police. 'Fuck the heddlu' is just so great to say xD

11. Favourite native writer/poet? I have a lot of em, the predictable answer would be Douglas Adams or Alice Oseman or H.G. Wells or someone like that, and they are great ofc, but I'll go a bit more obscure for non-Brits: J.B. Priestley. He was a playwright who did a play called An Inspector Calls that everyone does at GCSE (so at about 16) and the message is basically 'society has a responsibility to look after the poor that the rich refuse to take', it's one of the best plays ever written imo.

Thanks for asking! :3

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's a polemic :(

oh, hell yeah, THESE are the questions I can answer *cracks knuckles in English student*

POLEMIC [pəˈlɛmɪk]

So, the google definition of a polemic is a "a strong verbal or written attack on someone or something". Basically, it is a piece of writing, either fiction or non-fiction, made to critique a certain ideology or person that they view negatively. It's basically the hate-form of propaganda.

A famous polemic you may know is J.B. Priestley's socialist polemic, 'An Inspector Calls', written in the mid 1940s and set in the early 1910s, which is a play focused on social injustice, the failure of the older generations and capitalism. It wants us to view traditional and capitalist ideology as the downfall of society, while uplifting socialist ideology and the hope of the next generation.

(assuming you asked bc of my Cheap Villain nod,) Cheap Villain is a polemic on the treatment of love interests within romance and fantasy genres, as well as the treatment of love interests by the fandom and consumers of such media.

14 notes

·

View notes