#its my philosophy that when even when all seems bleak you can still find happiness

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

November 10th happy (non-canon) birthday, Clem

#psychonauts#clem foote#crystal flowers snagrash#i gave crystal one so of course i gave clem a birthday too#its my philosophy that when even when all seems bleak you can still find happiness#how do you like the new pixel brush ive been using? i like using it#my doodles#2024

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

[TLDR: me attempting to make sense of the Arcane's eldritchness, which sounds ironic in hindsight but hear me out]

Revelation after revelation aside, there are many pieces of foreshadowing that tell us why Viktor's commune wasn't as great as it seemed.

Visually speaking, all the clues are right there.

The first thing we see of the slums of Zaun is this.

Vi, leading their little group, is astonished to find such a thing—and to think that Huck was there, serving as one of its ushers! Huck, who she immediately calls a filthy traitor; having succumbed to shimmer the last time she saw him—meaning he'd turned to Silco both literally and figuratively—what with his use of the drug and the fact that he'd ratted her and Caitlyn out to the tycoon.

Miss Ma'am is bamboozled.

How the hell did he end up there? At this...paradise? At the slums, which, only a few weeks or months ago; was still dark, dusty, violet, and violent!

Something has changed, obviously; and Huck himself admits that his past was him 'at his worst'. Simply awful. But the Herald had saved him. And because of that, he was leading a better life, now. Naturally, at this point, Vi and Jinx seem wary.

There's gotta be a catch, no?

The landscape and the characters exemplify this.

Let's start with the land itself. Look at how empty it actually looks. Yes, there's a field of flowers. Yes, there's a community, teeming with life. Yes, it's literally heaven. But the lighting. The colours. It's so...bleak. Like a dream. The mountains are green, but they're cast in grey and white; and added with the negative space, there's an eeriness to it that contrasts Piltover's version of an eutopia.

You can argue it being the vast resource difference, as Topside is the superior city for a reason, but the commune is still filled with numerous individuals with just as much creativity as their counterparts. Intelligent and sentient beings—people, with minds to set to whatever task may be at hand.

Now, let's think of the people.

The biggest difference between the two communities is this: the 'healed' of Viktor's paradise wear only one mode of dress: white. It's almost uniform—which is notable, as, previously in the episode, Viktor speaks of 'chaos'. We see how fascinated he was by the mess that Vander's psyche had become, and in an attempt at detangling that chaos, he was 'setting things right' inside the man's mind. Bringing him back to something resembling normalcy. Order.

This is particularly significant for the fact that, in the game, he's remembered for his philosophy on glorious evolution (also mentioned in the show, as we know)—which is centred on the enhancement of the human body to transcend its fleshly limits.

Piltover, in contrast—and by extension the 'unhealed' of Zaun—go against this code. We see shimmer addicts, we see corrupt individuals, we see bigoted populations, we see conflict between the cities. We see human nature at its finest. Even the episode titles, all the way from Season 1, display this.

S1E1: Welcome to the Playground S1E2: Some Mysteries are Better Left Unsolved S1E3: The Base Violence Necessary for Change S1E4: Happy Progress Day! S1E5: Everybody Wants to Be My Enemy S1E6: When These Walls Come Tumbling Down S1E7: The Boy Saviour S1E8: Oil and Water S1E9: The Monster You Created S2E1: Heavy is the Crown S2E2: Watch It All Burn S2E3: Finally Got the Name Right S2E4: Paint the Town Blue S2E5: Blisters and Bedrock S2E6: The Message Hidden Within the Pattern

Again, human nature. Colourful, tumultuous, unsynchronised. A need for knowledge. A need for violence. A need for change. A need for exploration. A need for control. Everything that we can have, we take.

That's the point of Viktor's quote:

I understand now. The message hidden within the pattern. The reason for our failures in the commune. The doctor was right—it's inescapable. Humanity. Our very essence. Our emotions—rage, compassion, hate. Two sides of the same coin, inextricably bound. That which inspires us to our greatest good is also the cause of our greatest evil.

It's a paradox.

This is a sophisticated conjuration. A singularity, simultaneously self-replicating and self-annihilating.

He wasn't just talking about the Arcane. It wasn't just about that 'voice' he and Sky heard when gazing at Jayce through Salo's eyes. It's also about humanity.

So, how does that relate to his commune?

Here's the thing: it looks like heaven, but later on, when Viktor dies and everyone else follows, it's practically limbo. It's liminal. Initially, you only have the vague sense that there's something off about it, but you can't tell what. It's filled with people, yet at the same time, it looks like it shouldn't have any to begin with. Mysterious. Suspicious. Almost dreadful; something that makes you realise: if you think about it too hard, you'd drive yourself insane.

There's something intrinsically natural about the commune, something untouched by human hands; but there's also something intrinsically human about it, something unnatural, cultivated in a way nature itself cannot replicate. That's the catch. It should be a balance of both. An ideal community would show this.

Viktor's connection to the Hexcore tells us that he's, in part, transcended both humanity and the natural world. He's breached the ineffable and the incomprehensible, and brought it into the existence(s) of those who could know of and experience it. Bringing 'paradise' to those who were never meant to realise what it was. Forcing onto them the Arcane, even when done with the best intentions.

For the suffering Zaunites, they have everything they could possibly want: food, water, shelter, rest, belonging, peace, survival; the life that they once could only dream of having. It's perfect. They don't have to be in pain, not anymore.

But the commune is isolated. This is very much seen in the gate symbolism: all are welcome, but once inside, you'll never want to leave. You'll never have to. Because to be cured by the hands of the Herald means to bear his mark. To be saved is to bind yourself to him.

The open archway is also a taunt: the gate is open, it'll always be open, but would you ever risk going back out? Would you really trade this for anything else?

Are you truly willing to leave paradise? Are you truly willing to part with the Arcane?

The Arcane, which had given them everything they'd yearned for through Viktor.

Now, see here: Vi catches a glimpse of Singed exiting Viktor's abode. It's presumably the healing tent, as his main 'bubble' (the place where he 'recharges', so to speak) is the one in the distance.

The point is: Vi sees Singed leave the healing tent. What makes this suspicious is the fact that the man left unhealed.

Note that, prior to this point, the sisters have reconciled and were even willing to stay in this little underground haven despite their initial scepticisms. They, just like everyone else, have been lulled into the comfort the commune provided. So, to see someone else suddenly exiting Viktor's watch—someone with no traces of the Herald's touch, someone who's still bandaged and deformed—is a wake-up call.

Why else would you go into the healing tent, to the commune, if not to have yourself cured or seek respite? Why is this man, who'd obviously be easier work to deal with compared to Vander, not 'saved'?

Vi follows him. Then, Singed leaves the commune entirely.

In her eyes, someone had willingly turned away from 'paradise'.

Logically, this begs the question: Why?

Because that's where the fantasy ends.

Right as Vi comes to the gate, the camera cuts to that Noxian spear upfront. A threat to the 'perfection' that existed within the borders. A reminder that the world outside still exists; a world that Viktor hasn't touched in its entirety, a world that still begs to be saved, a world that is still human at its core brimming and simmering.

That's the reason Viktor's named a herald: he's an omen. He'd brought about a transformation to those he healed. To the slums. Providing a drastic shift in people's lives (or whatever 'life' still counted for those he'd influenced) that left many devastated when Jayce blew a hole in his chest.

By spreading the use of the Arcane through other agents (again, the 'healed'), he essentially reproduced the effects of the power that he had at his disposal, while at the same time allowed himself to better comprehend how the Arcane worked—and by extension, allowed that very power to adapt.

But at the same time, he himself is also the key to undoing it.

From Jayce and Ekko, S2E3:

Viktor hypothesised that there may be something he called 'wild runes'. Patterns that occur naturally when the border between our world and the Arcane is thin. Runes like the ones you use in Hextech. What's the difference between those and wild runes? Pass me a tome. So, I used words you understood in order to elicit your action. This is what Hextech runes are. Pass me a tome. Pass me a tome! There—you sighed. Still a kind of language. A sound, but not words. Something raw; natural. That's wild runes. In most places, the Arcane is dormant—but here and there, it's more active. Wild runes are— —sort of like its fingerprints. Exactly! ...so, you're telling me: that pattern is on my tree, because you pissed the Arcane off with all your demands?

Viktor being infused with the Hexcore—which we can reasonably assume is a wild rune, as can also be seen with its matrix—makes it so that he himself acts as what a Hextech rune would do to it (the Hexcore). Through Viktor, the Arcane is refined, and in a process that doesn't completely destabilise (compared to pure Hextech, as can be seen with the weapons). For Viktor to lose control or to be harmed means making that magic either go wild (the weapons) or make it dissipate (the commune).

That's why the fantasy 'ends' at the entrance of the commune: anything past that is out of Viktor's reach, and remains 'untouched' by the Arcane.

From Jinx, S1E5:

So, all about these runes: they form some sort of mathy, magicky gateway...to the realm of heebie-jeebies. And this turns it on!

Say it again: the runes make a gateway. The Hexcore was a rune matrix, an array of wild runes that formed a singular entity. An entity which is now 'one' with Viktor. It means being the 'Herald' is also being the 'gateway' for the Arcane. The traditional role of a herald is to proclaim and carry messages; we don't know what message the Arcane itself wants to send, but we do know for a fact that Viktor is at least doing its work in creating that commune in the slums of Zaun.

From Singed, S1E6 & S2E6:

The mutation must survive. You must survive, Viktor.

The Machine Herald himself is self-replicating and self-annihilating. He can 'cure' the afflicted, thus infusing the Arcane into other individuals and replicating its structure inside them. And at the same time, the Arcane is also what 'kills' him—with Jayce using (what looked to be a mutated version of) the hexcrystal of his hammer to blow through Viktor's chest, where we know the Hexcore was placed during Jayce's revival of him in Act 1.

This is why the commune, despite its purpose as a safe haven, also exists as a place of great danger. Why it really isn't all That™, even despite Viktor creating it as a safe space for many.

See this exchange between Vi and Jinx:

This place...do you think it could actually work? Underground utopia, run by a skinny tin Machine Herald. Maybe when Piltover slides into the Sump.

Jinx was right in calling it for what it is, despite the words being in jest. A utopia. Working 'when Piltover slides into the Sump'.

It's an impractical scheme. Too perfect. Too good to be true.

An impossibility.

Do you believe in fate, Doctor? Our paths carved before us. Guided by an invisible hand? Not fate. Evolution. Nature's greatest force, forever in flux. No. Evolution has a destination. Not to combat nature, but to supersede it. The final, glorious evolution. But he isn't a specimen—he's a man. And he needs my help. I will not sacrifice his humanity for your cause. You may leave. Very well. But I assume you understand already: if you perish, this community is soon to follow.

Viktor understands. He understands. He just wasn't ready to admit it to himself when Singed said it.

I understand now. The message hidden within the pattern. The reason for our failures in the commune. The doctor was right—it's inescapable. Humanity.

Human nature and human essence aren't self-sustaining. That's why the Arcane was so effective in 'healing' all those people. Their humanity hampered them from healing themselves; both in the sense of the human bodily condition (the limits of the physical self), and in the sense of humaneness (of empathy, of choice). The human body cannot survive its own traumas without an artificial means of a cure (case in point: Vander). And the Arcane acted as its solution.

Mere instinct doesn't let you live—you need to learn how to direct your life after survival. To adapt. To grow. Humanity, self-replicating and self-annihilating; the escape from that cycle, that's the glorious evolution Viktor speaks of.

A utopia. Impossible and impractical. Humanity: that which inspires us to our greatest good, and the cause of our greatest evil.

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

As much as I enjoyed watching that trainwreck, god, I mourn Overwatch.

That was a game I had so much fun with for so long, years even, and the first game I ever got that into.

It had a great and interesting cast of characters that were mostly fun to play and swap between; what seemed at the time like a potentially engaging epic story (big RIP there); beautiful maps that were... definitely video game levels but they gave a very good impression of a fully realized world; and just a very satisfying casual gameplay loop that just worked very well for me.

Yeah, it had its problems back in the day - loot boxes were a bitch, but take away the push towards gambling addictions it was an ideologically acceptable game mechanic (it's basically the same kind of mechanic that is one of the core Animal Crossing gameplay loops and I like Animal Crossing) - but nothing that truly detracted from it until matchmaker fucked me over a few years in.

And I was on the Xbox version, so you know I didn't have to deal with the toxic side of the playerbase.

And to watch it go down in a Greek Tragedy, sacrificed on the alter of the bottom line, yeah, it's been entertaining as I'll get out, but it's also deeply painful to watch. The broken promises, the kowtowing to authorian governments, the abuse all the goodwill: it hurts. It hurts more than Harry Potter (for me).

And what hurts most of all is knowing that it's us, the people who had no control over the game's murder - the players who poured their time and love into it, the actual game devs whose hard work made the actual game and side content people enjoyed, and the characters themselves (yes, I'm counting this) who may never truly get to have their stories told now - are the ones who suffer over this and the ones who sunk the ship - the investors and higher management who only serve their mindless, soulless god of wealth in disconnected hope feeling something - will get to cash out their checks before the boat they were never even on to begin with and go buy their fifth mega-yacht to pretend their happy.

So pour one out for Overwatch: a pretty good, if sometimes controversial PvP video game that met a terrible fate at the hands of the very system it sought (at least by some interpretations) to unmask.

May all the missteps and disasters it fall squarely under the legacy of Activision-Blizzard, the villains who actually made this shit show happen.

And may Overwatch's own legacy, the one the hard working people who actually made it wished to give us, be its core philosophy:

Never accept the world as it appears to be, dare to see it for what it could be.

That one line truly impacted me when I first heard it. And despite my struggles with my personal life and my inability to crawl my way out of the heap of unwanted toys this twisted society threw me in, those words are still locked into the core of my personal philosophy.

And the world I can see is one where people aren't forced to give their creativity to the lowest bidder and be worked near to death with only the strained hope of their hard work being loved by strangers they'll never meet only see that blood, sweat, and tears left abandoned on the cutting room floor, deemed 'unprofitable'.

A world where everyone can experience art on this scale and every other, and everyone can make it and freely share it with the world without stress.

Because I can see a world where people are allowed to exist as people who can eat and work and love as they please and actually build their communities as is beneficial to them and not just be tools to run a machine that's only function is to keep its tools working.

And as bleak as things look from my lonely bedroom, I know if we can find a way to come together, that world is still very much in grasp.

Yes, we are entering desperate times for it. Yes, at the end of the day, we will likely have to sadly forsake necessary personal morals to depose the cruel cultural morals that rule over us.

But we have nothing to lose but our chains and a whole world to gain.

So I have just one thing to ask:

Are you with me?

#overwatch#overwatch 2#jesus that took more two hours to write#i did not intend to write a full eulogy and call to action when i opened up the post editor#just a 'oh yeah it sucks about overwatch' post#but these things tend to happen when i actually care about what i'm writing

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

And If This Is It

Third chapter in a short series.

Pairing: Dean Winchester x Reader

Mentions: Jess, Sam, Charlie, Cas, Gabriel, Jo, Jules (OC)

Trigger warnings: Excessive alcohol consumption; puking

I am the sole author and reserve the rights to my work. However, I am not the owner of Supernatural as a franchise, or the characters including, but not limited to: Dean, Sam, Castiel, Gabriel, Jo, Jess, or Charlie.

CHAPTER THREE:

“Shots?!” Jules shouts over the deafening music.

He passes a tiny glass of clear alcohol to Y/N and Charlie. At this point, neither know if it’s tequila, gin, or vodka. At this point, neither truly care.

Carter’s, the hole-in-the-wall dive tucked between a pawn shop and convenience store, housed the trio every Wednesday night. When unable to convene outside of work any other time of the week, they at least have their sticky booth and cheap booze to fall back upon. If Y/N had half the mind to care, she could bet the shady owner had an unsavory side business that allowed for such decently priced alcohol. But she doesn’t have half the mind. The sharp air intoxicates her even before the first drink, drawing her attention elsewhere. Plus, Jules always arrives first to claim their usual seats, a round of drinks at the ready. Tonight, he focuses on shots.

They clink their glasses together, slam them on the grimy counter, and tip them back. Charlie cheers, her flushed cheeks pushed back in a sloppy, wide grin. Her laughter bellows into Y/N’s chest, forcing her to join in. The tribulations of the past seven days wash away with each new shot. Her mind only wanders as far as Jules across the table and Charlie next to her. Nothing mattered right now, not unrequited love or shitty jobs.

“So! So! Then I said, I said! I don’t care what those bitches think. I’m— I’m a good server, ya know? And I told James— “

“—Jason,” Jules supplies.

“—Yeah, that one. I told Jason to stick it!” Charlie slurs, recounting her meeting with their boss.

Y/N cocks her head at Charlie, who white knuckles the table to stay steady. “Did you really?” She speaks slowly, the words catching on her heavy tongue.

“No. But I thought it. So it counts.”

Jules and Y/N share a look. “Sure it does.”

Out of the three of them, Jules holds his liquor the best. He drinks anyone under the table, and still gets up for work without a grueling hangover. Y/N took Thursdays out of her availability because she doesn’t have his stamina. It took only two shifts filled with headaches and poor service for her to realize she cannot power through the dehydration and pain. Wednesday nights take it out of her, and the following morning includes a date with her toilet and a bottle of Pedialyte. Trying to keep up with Jules, which she foolishly does, is a signed, sealed, delivered death sentence.

She happily accepts it, for it means quality time with her friends.

“Listen, missy. You listen here! You don’t get to talk about— about thinking things and not saying them!” Charlie accuses. Y/N holds up a hand in protest. “No! I don’ wanna h-hear it.”

In just a few words, the thoughtless cocoon Y/N made shelter in crashes to the ground, bringing up debris and Dean’s face. His freckles. His lips. The things she wishes she could say— I love you, I want you, I need you— taunt her, dancing across her mind and scuffing up the floors. “Yeah? Well I don’t wanna talk about it!” She all but shouts.

Charlie huffs. “Fine.”

Jules says nothing, simply peering at his two best friends with mild concern in his glossed over eyes. Y/N avoids his gaze, instead choosing to watch the desolate street through the frosty glass. Charlie waves her hand to the waiter to call for another round.

With new shots in front of the respective drinkers, the tense silence dissipates quickly, easy conversation about what each other missed taking its place. Jules relays the details of his third date with Alice, a girl he served once. She left her number and on a whim he decided to text her. The thirty percent tip she left helped her case, too. The two get along great, from what he says. They share similar interests, including early morning trips to the gym and pretty much any physical activity. At the thought, Y/N shudders. She reserves her mornings for her bed and coffee.

As Jules carries on about the lovely Alice, Y/N finds herself thinking down a stark path. It travels away from Carter’s worn booths and blaring music, finding solace in scratching concrete and big hands. Some days, she truly wishes she could call Him her boyfriend. Some days, she only wishes to be near Him. Right now, it’s the latter. The too-loud conversations around her, the thick air, the heavy warmth in her belly; it makes breathing a chore.

Charlie grabs her wrist, pulling her over-worked thumb from her teeth. The crevice between her nail and skin bleeds. Out of her head now, she realizes her friends stare at her, conversation ceased. Jules’ eyes bore into hers, and she can feel Charlie staring at the side of her head.

She doesn’t have to ask what crosses their minds. Their faces paint light worry and their questions clearly. Y/N sighs, head dipping to focus on the empty glass before her. Neither of her friends say anything, allowing her to trudge through her hazy thoughts.

“I…” she starts, but shakes her head. Needing a something to center her, she throws back her head and swallows another shot. It burns, but it reminds her she is alive and well. Well enough, at least.

Charlie only knows what an inebriated Y/N shared once, and she assumes Charlie happily passed on the message. Even still, the words halt in her throat. Charlie interlocks their fingers, giving a squeeze. It’s okay, Y/N knows she wants to say. “I need some air.”

Not awaiting a response, she drops Charlie’s hand and alights from the booth. Concentrating on walking, Y/N works her way through the crowd to the door. The cooling air of the night caresses her cheeks, relieving some of the heat from her skin. The car-lined road before her, adorned by dim streetlights and neon store signs, appears in double. Cigarette smoke wafts to her nose.

She turns towards the scent. Sober Y/N would never smoke. The taste lingers on her tongue days after, plaguing anything she drinks or eats. However, Drunk Y/N, riddled with anxiety and one too many shots, craves it.

A woman clad in little clothing leans against the worn brick, cigarette balanced between her fore- and middle finger. Y/N stumbles the few feet to her, her body moving before her thoughts. The lady looks up. Her tired eyes trail over Y/N’s body, taking in the sight, ending at her face. Y/N tries to imagine how she looks.

“Can I bum a smoke?”

Wordless, the woman passes Y/N her pack of menthol and a lighter. Nodding in thanks, she lights the cigarette and draws a deep breath in. Sweet relief. She sighs contentedly, handing the pack and lighter back. In silence, Y/N joins the stranger in leaning against the wall. Drunken camaraderie over a bad habit makes the world feel smaller; friendlier.

Here she stands, a mess. And here some straggler stands, someone she’s never met, probably going through her own shit. People are small, in the grand scheme of things. The big picture. Everything feels silly, like a cosmic prank, wherein God will jump from the sky and yell, “Hahahah! Happiness is not a by product of existence, you simple minded fucks. I made you to suffer.”

She wouldn’t be surprised, not anymore. Some days, her heavy bones and even heavier head weigh her down so much, all she can do is suffer. Suffer through schooling; a dead end job; a wistful love; a bleak future. Perhaps God created her as suffering; not a person who could, but a person who is.

A long drag from the cigarette clears her mind. She reminds herself that her sidewalk existential philosophy is only wise by proxy of this night’s poison.

Flicking the cigarette, she nods her head in thanks. With a clearer head, the double vision subsides. Still, she sways as she walks back to the door of the bar. Bracing herself, she pushes it open. Music, this time a familiar song she can’t place, wraps its comforting fingers around her heart. This is where she is meant to be: sandwiched between the tacky wall and Charlie, sat across from Jules.

Charlie stands as Y/N comes into view, allowing her to take her seat once more. The conversation continues seamlessly, as if Y/N never left. Jules and Charlie keep the side glances to minimum, instead focusing on another round— this time paired with glasses of water— and what Jules’ should do next with Alice. Deciding to solely focus on her friends before her, Y/N utilizes her remaining energy on keeping up with the conversation.

“I mean… she seems to like you a lot, dude. Who the hell… else would get up at five to go on hikes?” Y/N slurs, raising her voice.

“A crazy, person! She’s crazy.” Charlie whispers with a shake of her head.

Y/N laughs, downing another shot. “Yeah, well, either way, she likes it, ya’know? She likes it!”

They dissolve into a fit of body-rocking, soul-shaking laughter. As it peters out, the energy follows suit. Y/N hits a wall, her shoulders sagging with a sigh. “I’m— I’m gotta go, guys. My eyes are gonna fall out.”

“Wait! Just one more shot. C’mon, Y/N/N! One for the road,” implores Jules.

Ever the bad influence, Y/N agrees. In the back of her head, she hears her sober-self admonish her. She pushes it away while Jules waves his pointer finger for another round. Grace, the waitress, already has three ready. Used to their antics as their usual server, she also drops the bill.

Clink, slam, gulp.

Y/N slaps a twenty on the bill, knowing it covers her portion of drinks. Charlie scoots out of the booth again, staying standing to wrap Y/N in a bone-crushing hug. The scent of vodka and Daisy fills Y/N’s nose, covering every piece of her in Charlie. Jules envelopes her next. Her cheek rests against his chest, and he sets his chin on her head. They hold each other for a moment before pulling back.

Y/N leaves her friends to settle the rest of the bill. Escaping into the night, she embraces the cool air. However much she finds solace in Carter’s, the stuffy heat paired with the little room to move constricts her. Even on the now empty street, her chest refuses to loosen. The returned double vision surely doesn’t help.

“Walk,” she mumbles, commanding herself to just fucking go.

Normally, she would call a ride service right about now; or she’d stick around with Jules and Charlie to ride with them. But right now she needs the freedom of the seedy side streets and open sky above her. Four doors and a short roof would only further agitate her.

So, for the sake of her sanity, she makes her way down the street. Having walked these streets many times, Y/N’s feet carry her, rather than she commanding them. As she works her way towards the main road, the lights become brighter and cleaner; trash slowly dwindles in the gutters until they’re as clean as they can get in this part of the city.

At the intersection of Boulder and Hamilton, she stops. Going left would lead her home, a destination twenty minutes away. Going right would take her to Dean. Her body decides before her mind. Five minutes and a few turns, she stands on Dean’s stoop.

Her heavy fist raps against the wood while she leans her forehead against the cool service. Eyes closed, Y/N focuses on slowing her breathing. The edges of a panic attack creep into her mind. Why am I here? Why am I here? Why am I—

The door opens, taking from Y/N her support. Without it, she falls forward, preparing to meet the unfriendly catching of the floor. Instead, warm, bare arms wrap around her waist. “Y/N?” Dean asks in his deep, gruff tone.

God, I love your voice. The thought crosses her mind before she can stop it.

“Oh, do you, now?” Dean teases, righting her on her feet but keeping his hands on her shoulders.

Fuck.

“Shuddap,” she scolds.

“What are you doing here, Y/N/N?” He moves a hand from her shoulder to grasp her chin, pointing her face to look at him.

She leans into it. “Drunk.”

Dean chuckles, a warm sound that pushes any anxiety out of her mind. He has that way about him. “I can see that. Here, come inside so I can close the door.” She does as he asks, still leaning into his touch. He leads her to his couch, guiding her gently down onto the cushion. Resting on his knees in between her legs, he examines her face again.

She tries to look him in the eyes, she truly tries, but their overwhelming jade and the smell of his shampoo and his hands and that little grin and— and— and. The list goes on forever. In the dim room, lit by the outside lights and the paused TV, she wants to fall into him. Her fingers itch to grab his stupid stubbled cheeks and bring his stupid plump lips to her own. Her heart threatens to jump straight from her chest and into his hands. Her skin prickles where his forefinger and thumb hold her chin.

“Traitors,” she mumbles.

“Hm?”

Y/N shakes her head, causing Dean to release her chin. Dammit. “Nothing. I’m just— I’m so drunk, dude.”

He laughs again, sending a wave of peace over her body. “Yes, I know. Let’s get some water in you.”

Water sounds like a great idea, just the mention causes Y/N’s mouth to dry, readying for the coolness to coat her throat and fill her stomach. While Dean pours her a glass, she better settles against the sofa, shifting until her back rests against the arm and her legs splay out before her. The cold of the leather raises goosebumps, but it grounds her.

Dean returns with a stainless steel tumbler, placing it on the cushion by her hip. He lifts her legs and rests them upon his thighs as he too settles into the couch. Arm rested on the top of the couch and eyes caressing her flushed cheeks, he awaits for her to speak.

Every thought racing through her mind pleads to blurt out “I love you!” in some form or another. Taking a long, refreshing sip, she swallows the water and her heart. The hand gently kneading her calf provides almost enough courage to cast aside her inhibitions, but instead she listens to the voice in the back of her head. Why ruin something great? Why risk it?

Pussy, her warring side jabs.

Shaking her head, she removes her gaze from his and unto the television. “Die Hard?”

He waits a beat before he speaks, “Yes. How are you feeling?”

“Like there’s two John… John McClanes on the TV, which means two Hans Gru—bers, and I… I dunno if I can watch that.”

Glorious, golden, all-compassing laughter. “Well, I’m sure the McClanes will be fine; twice the firepower.”

Y/N can’t stop herself from returning to gazing at Dean. The lights from the kitchen silhouette his face, but she sees it, nonetheless. Knows it like its her own, for she sure has stared at him long enough. His seemingly perpetual little grin pushes his cheeks up the slightest bit. He looks so young.

With little thought or permission, she reaches a hand out to brush against his cheek. The barely present beard tickles her palm. Dean’s eyes flutter shut, and he nuzzles further into her hand. If only she could stay like this, legs across Dean’s, hand on his cheek, eyes closed.

“Dean…” she whispers, mostly for herself. Her heart will never get used to sitting so close to him, a beacon on her worst of days and a partner on her best.

“Hm?” he asks, still leaning into her touch.

It takes everything from her, her willpower, her bones, her chest, her lungs. She can’t stop herself for much longer, she knows. And, the thing is, her traitorous body doesn’t protest. Nothing in her says to stop; everything in her begs— no, screams at— her to grab him and hold him tight. To never let go.

As she leans forward, her left hand reaching for his other cheek, the tumbler clatters to the floor with an unforgiving clang. They both startle back, Y/N drawing her legs from his lap and Dean finally opening his eyes. The withering stare she casts at the stupid bottle should shatter it. Instead, it stays whole and mocking. She reaches down to right it, her knuckles white as she harshly slams it onto the floor.

The lights seem to bright, now. The throbbing in her head makes its presence better known, pulsing the picture of John McClane leaning over a sniper rifle. Bile rises in her throat.

“Fuck,” she barely gets out before bolting from her seat and running for the bathroom. Way to ruin the moment, you monkey.

Y/N grabs the edge of the toilet with one hand, gathering her hair into a mock ponytail with the other. At the sight of the bowl, her stomach instantly lurches. With the little she had to eat, mostly burning alcohol makes a return, accompanied by some nachos and fries.

A set of hands replace her’s in her hair, allowing her to better grasp the toilet. Dean settles behind her, bracing her sides with his thighs and whispering unintelligible comforting words in her ear. With his free hand he rubs her back, up and down her shoulder blades to her lower back.

No longer retching, she wipes her mouth toilet paper. Her body still shakes, skin clammy and hot. She crosses her arms over the seat, resting her forehead against her forearms. Dean continues to massage circles into her skin. “I’m sorry,” she mutters, to the bowl and to Dean.

He releases her hair, instead choosing to pull her from the toilet and into his chest. Together, limbs wrapped endlessly, Dean leans against the wall and she leans against Dean. “Nothing to be sorry for, Y/N/N. C’mon, you’ve seen me completely plastered.”

She tips her head to the side, resting it against his shoulder. “It’s gross. Not cute. At all.”

His chuckle rumbles against her back. “Nah, you’re always cute.” It’s barely a whisper, if she weren’t next to his mouth she’s sure she wouldn’t have heard it.

They sit in silence, breathing against each other. Y/N revels in the coolness of the ground and his arms around her waist.

“Why’d you drink so much, Y/N/N?”

Her sighs heaves her shoulders. “I dunno. Why do you drink, Dean?”

“Sometimes to forget things.” He keeps his voice level, but Y/N knows him well enough to see he worries for her. The implications of his statement do not go unnoticed.

She shakes her head. “I just have a lot going on. Plus, it’s Wednesday. You know that’s my night with Jules and Charlie. We drink. It’s what we do.”

“Okay. Just checking. Let’s get you to bed, kid.”

#dean winchester#dean winchester fic#dean winchester x reader#dean winchester fanfiction#and if this is it#supernatural#SUPERNATURAL AU#supernatural fic#friends to lovers

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Broken

I have come to the grim realisation that I will never be fixed. I am an intrinsically broken person, it’s become part of my soul. I spent so long wallowing in the pain of being broken, I never took the time to try and fix myself and now its too late. Yes, I will probably heal somewhat in the future. I may find a way to catch all of my broken shards and tie them together with the shreds of self preservation I still have. But I will never be fixed. I will never find a way to glue the pieces of my soul back together, to hide all the cracks and make it seem like I was never broken in the first place. I let the world tear me apart and these scars will never fade, through this life or the next. I feel like I should be more devastated by this than I actually am, but I just don't know how to feel. Im so tired all the time, I can't sleep for more than a few hours a day, my head hurts, my heart hurts.

For the longest time, all I have ever heard is “it gets better”, but nobody could truly answer me when I asked “but what if it doesn't?” because nobody wants to consider the fact that there is no fixing some people. Sometimes, there is no bouncing back, there is no magic cure-all that brings you back from the point of no return, to walk you backwards on toe dark path you chose to take. It’s too painful to think that this torment you're feeling now will never go away. It might dull, it might be just an echo in the back of your head or a tiny hole in your chest, but it never truly goes away.

A therapist might tell me that coming to terms with the fact I will never fully heal is the first step in recovery, but this isn't me setting off on that journey, this is me becoming resigned to the fact that I dont think I will ever truly be happy. I will never fully heal from this pain that I’ve endured. This trauma, these scars and nightmares and intrusive thoughts, these cravings for being skinny and feeling hungry and tearing myself apart, that is all part of who I am. I can fight it, sure. And I will, and I am, but it won't just go away.

I have been so hurt through my eighteen years of life, ive had my autonomy stripped away from me, ive had my soul crushed and my heart broken and my spirit completely destroyed. I lived through the words on page, twenty six letters smashed together to create a story I could escape my bleak life in, hundreds of pages for me to lose myself in, a hundred different stories with a hundred different protagonists and I am in all of them because they created me. I lived vicariously through these strong protagonists because I couldn't even stay strong in my story, my reality. So I folded myself into the pages to forget all of this pain that I felt in my bones, hoping that maybe if I read these pages enough times the universe would be kind enough to let me fall in-between the lines, through the paper and into this world where I felt I truly belonged. but the universe isn't known for being merciful, for wasting its time on sad teens with too much time and not enough hope. and years later, im still here, still kicking, so maybe the universe knew what was best.

If you know me, you know I have my own personal philosophy, my own way of rationalising the world to stop myself from going completely insane. Everything happens for a reason, and very rarely will you know what that reason is while its happening because you haven't had time to let it affect you yet. Everything has to have a reason, otherwise nothing makes any sense and the world would fall apart. I dont know my reason, and I think my world is starting to crumble beneath my feet

But its okay, ill find my reason somehow. For now, I have a bucket list of things I need to do before I die and im slowly working through it. Ill let you know whether I find my reason before I finish my list.

1 note

·

View note

Note

Is Deus Ex Machina always a bad thing? People who didn't like the finale of Avatar are always quick to point out the lion turtle, but I think we both agree the ending was both emotionally and thematically satisfying, and to me that's the most important thing. But my question is: if it IS satisfying, is it still a DEM? After all, DEM usually carries this idea that the ending is ruined and it leaves a bad taste in your mouth, which the Avatar finale doesn't.

Coincidentally, I was thinking about this just the other day, although I wasn’t considering making a post on it.

I think what makes this discussion troublesome is that there are two very different operating definitions for “deus ex machina.” I tend to think of it in terms of the classical definition, so I don’t personally have any problem with it when it’s done well, but most people seem to be operating with something like the same kind of shorthand that has turned “Mary Sue” into a meaningless complaint.

The term translates to ‘god from the machine.’ Wikipedia can give a functional summary of how it was originally employed and the criticisms that arose about it even amongst those old-timey Greeks. My own take is informed by those origins and the Greek myths that I’ve loved since I first learned about them in grade school. In a setting where gods and magic are in play, I don’t see a problem with a god being so moved by the events of the story or the character of the protagonist(s) that they intervene in otherwise impossible scenarios. The key here is that the story needs to justify why the god/power is intervening here and not in all kinds of other situations; if a god comes along and raises someone from the dead, or hands over a magic sword, or whatever, then it needs to be clear why people still die and magic swords aren’t sold at every corner market.

The Lionturtle is indeed a deus ex machina in that it is a god-like power suddenly entering the story to hand Aang knowledge that he would not otherwise have been able to attain. However, AtLA firmly establishes that there are spirits in the world with god-like power. Hei Bai is the first at a relatively small scale (and was another spirit moved by Aang’s steadfast purity to enact a happy ending, hmmm…), but we also see Koh having knowledge that predates the existence of the moon and the ocean, Koizilla being able to smash a whole fleet with the help of the Avatar State, Wan Shi Tong being able to move an infinitely-large library between the spirit and material worlds, and an eclipse of the sun shutting down all Firebending. These are all powers that the normal humans of the setting do not have, but they are all exercised as a result of the intervention of the protagonists, so I think they’re perfectly fine elements to have in the story.

Just about the only thing that might separate the Lionturtle from these other examples is that it seeks Aang out, rather than the other way around. However, I think that’s an oversimplification of the situation, in which we had just gotten an full episode of Aang holding fast to his belief in the sacredness of all life, despite disagreement and harassment from his friends. He meditates in search of an answer, and it’s then that the Lionturtle reaches out. So I think Aang ‘earns’ its attention by his unique beliefs, his steadfastness in the face of painful opposition, and his action in seeking a solution via meditation.

Why does the Lionturtle not reach out to other people? Well, the only pacifists in the franchise are Air Nomads like Aang, and there’s possible evidence that they weren’t all as steadfast when push came to shove. However, I don’t think the fate of the world hinged on whether Gyatso or some other random Air Nomad killed an enemy while fighting; Aang is in a fairly unique situation in that regard. Theoretically, a previous Avatar might have faced the same dilemma that could have been resolved with Energybending, but as we saw of Yanchen, perhaps those Avatars didn’t really seek out another solution besides violence. The Kyoshi novel does a great job handling this, showing Kyoshi struggling with similar questions but finding her own answers that do not match Aang’s. Perhaps Aang really is the first person in an Age who merited the Lionturtle’s intervention. It helps that the intention at the time of writing was for it to be a technique only available to the Avatar, so that definitely limits the potential situations where it might have been relevant.

So we’re left with the question of whether Energybending itself conforms to the established rules of the setting. I personally think it does, quite handily. We saw examples of bending being taken away before, at least on a temporary basis. The death of the Moon Spirit takes away all Waterbending. The eclipse on the Day of Black Sun takes away Firebending for its duration. Ty Lee pokes Qi-points to disable bending even while leaving limbs otherwise functional (sometimes). Those all help clearly establish that bending is tied to the physical body, and specifically the Qi energies flowing through it. We see esoteric manipulation of those energies by way of Waterhealing, Lightningbending, and the time Aang’s spirit is knocked out of his body by physically crashing into a bear-shaped shrine/idol.

So yes, the Lionturtle is a newly-arrived god who imparts special magic to solve a problem that couldn’t otherwise have worked out so neatly, but all the elements are there to make it a workable plot element. If the Day of Black Sun had worked out, would people be complaining about how Deus Ex Machina it is for the gAang to stumble across information on an eclipse coming before the return of Sozin’s Comet that will take away Firebending and allow Aang to confront Ozai without training up to the a higher fighting level?

Well, not if Aang kills Ozai in that scenario, I expect.

The root of the way most people use ‘deus ex machina’ in modern times, I think, links to what Aristotle is said to have been alluding to in that Wikipedia article, and what Nietzsche also seems to be getting at. Specifically, they seem to think it’s better when a tragic story is allowed to end in tragedy, rather than an audience-pleasing happy ending getting tacked on in an act of weakness and cowardice. It’s fair to criticize this (I enjoy tragedy as well as happy endings, when it’s done right), but I think it can be taken too far into a desire for bleak endings in general. It would be more ‘mature,’ the thinking goes, for Aang to have to kill Ozai, be tainted, scream his angst to the sky, and show the audience that Life Is Dark even though it’s a trite message that doesn’t really follow from anything that came before. The thing about Tragedy that a lot of people forget is that it needs to be set up with as much care and earnestness as Deus Ex Machina, or else it’s just as hackneyed and immature.

AtLA is not a tragedy. It is not about the mistakes and flaws of the protagonists piling up into chaos. So the complaint about ‘deus ex machina’ doesn’t even really apply, according to the original controversy about it. Aang is not freed from the consequences of a flaw, because his desire for peace and life is something that’s consistently portrayed as good throughout the rest of the series. It’s built up in his culture, the appreciation for the Air Nomads that’s conveyed despite their flaws, the focus on his being the last survivor of a genocide, and even the subtitle of the series (providing you don’t live somewhere that got the much more generic “Legend of..” title that fits Korra’s more generic legend so much better). It’s not a tragedy if everything is working out until a last minute swerve when all the good things suddenly become bad.

That’s a Comedy, according to certain modern definitions. ;)

The only story that could end with Aang giving up his ideals to kill Ozai using the philosophy and ways of the Fire Nation is a story about how the Fire Nation is right- that morality is secondary to strength and necessity. And if that’s the story being told, wouldn’t it have been easier to just make the Fire Nation the heroes in the first place, slaughtering corrupt pacifist hippies who would rather we all die than fight to improve the world?

No matter how you look at it, people who criticize AtLA’s ending by calling it a ‘deux ex machina’ aren’t doing so by using the text of the story at all. They’re either glossing over how the setup for all the plot elements is all right there in the story, or else they’re doing exactly what the ancient Greeks criticize bad deus ex machina for in the first place by putting the wrong ending on a story. So most who use ‘deux ex machina’ as a criticism aren’t thinking about the nature of Story at all, I think. They’ve heard the term, mistake it for general criticism of ‘unearned’ plot points, and/or use it as justification for their own pretentious fascination with bleak endings.

So, to summarize my answer- yes, DEM can be a criticism in and of itself, depending on the definition in play. It can apply to AtLA, also depending on the definition in play.

But applying DEM to AtLA as a criticism just doesn’t add up.

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

609: The Skydivers

I kind of wanted to start out by saying something about how this is the long-awaited third installment in the Coleman Francis Trilogy of Tedium, but that doesn't work. First of all, The Skydivers is actually Francis' middle movie, made in 1963 (The Beast of Yucca Flats was first, in 1961, and Red Zone Cuba third, in 1966). Second, that would make me sound like an Argento fan waiting twenty-seven years for The Third Mother, when actually my reaction to seeing The Skydivers pop up in my randomizer was “oh, right. There's another fucking Coleman Francis movie.”

Like its two sisters, The Skydivers is a bleak and disjointed experience. A married couple, Harry and Beth, run a skydiving school. Harry is having an affair with a woman named Suzy (if the name of her boat is anything to go by, the 'z' is supposed to be backwards). Beth retaliates by almost having an affair with Joe, the airfield's new mechanic. Joe was hired to replace Franky, who was fired for being drunk and now wants revenge on his former employer. When Harry spurns Suzy, she and Franky sabotage his parachute, and Harry goes splat. Suzy and Franky are gunned down by the FAA(?!). Beth feels guilty and breaks up with Joe before leaving the skydiving school to do something else that probably won't involve airplanes. Crow gets destroyed a lot, and I conclude that people whose names end in 'y' probably shouldn't get involved with skydiving.

If anyone's interested, there is at least one recorded case of a skydiver being murdered by sabotaging his parachute, that of Steve Hilder in 2003. The saboteur was never found and the case remains unsolved.

As for the movie itself, there's very little in The Skydivers that would be of interest to... anybody, really. The movie is dull and badly-lit, featuring boring people in awkward situations. About the only thing that really caught my attention at any point was the fact that there is some actual footage of skydiving, although you can never see the jumpers' faces up close and I suspect Coleman Francis borrowed it from some other film ('parachuting' footage featuring recognizable characters appears to involve actors hanging from the rafters by a backpack, which I can only imagine as being terribly uncomfortable). The closest thing to a theme I can find in this celluloid coma is the idea of thrill-seeking. Various characters search for a way to brighten up their colourless lives, and end up suffering for it.

The character Pete seeks thrills by skydiving – he claims it's the only thing that makes him feel alive and free, and he tries ever more dangerous stunts until finally he is unable to pull his parachute cord and falls to his death. In terms of the actual plot, however, Pete's fate serves no purpose except to ensure the FAA are on hand to witness Harry's murder later. It seems to have inspired Suzy's revenge plot, but sabotaging a skydiver's parachute is such an obvious idea that this wouldn't be necessary. His death feels ultimately pointless, not even Grist for the Wheels of Progress.

Harry and Beth each seek a thrill in the form of an illicit affair, but the results are very different because their partners respond differently to their ultimate rejections. Joe respects Beth enough to accept her rejection, not once but twice: when she initially tells him this can go no further and they must be content to be friends, he accepts it with grace. At the end, when she tells him she can't stay at the skydiving school, he accepts that too, even though it means he will probably never see her again.

Suzy, on the other hand, has no respect for anybody, even as she expects other people to respect her – witness how she attacks Harry when he calls her a 'broad'. She was spoiled as a child, and never learned to see other people as anything but a way to get what she wants. When she can no longer get the sexual excitement she wants from Harry, she kills him. Franky is nothing but a tool she uses to exact this revenge. Beth, who has nothing to offer, means nothing to her.

I guess it's mildly noteworthy that The Skydivers is the only Coleman Francis movie in which more than one woman has lines. In The Beast of Yucca Flats the only woman who talked was the mother of the vacation family, and she didn't have a whole lot to say. In Red Zone Cuba I think Chastain's wife had a line or two, but I can't remember a word of them. In The Skydivers, both Beth and Suzy have a fair amount of actual dialogue, and manifest distinctly different personalities. They are stereotypes, being the 'femmy fattily' and the long-suffering wife, but they make decisions as individuals rather than as 'women', with comprehensible reasons for doing so. So, uh, that makes Coleman Francis better at writing women than Tommy Wiseau, I guess.

I feel like the universe owes me a cookie for putting me in a position to write that sentence.

I really don't think the consequences of thrill-seeking are the point of the movie, though – the fates of Harry and Beth have more to do with their partners than with the actual illicit sex, and Pete's death seems far too pointless. The whole movie seems pointless, really – as Beth leaves the airfield at the end, we have no idea why we were just told that story, and what, if anything, we were supposed to take from it. That seems to be a theme of Coleman Francis movies in general: nobody gets a happy ending and when all's said and done there's no point to any of it.

Consider The Beast of Yucca Flats. At the end the monster is dead, but a family has perhaps been destroyed. Or Red Zone Cuba. The villains don't get what they want, but neither do the good guys, and a half dozen other lives have been ruined along the way. Life is nothing but a series of misfortunes. Happiness is fleeting when it appears at all, and death is neither release nor justice, it is merely death. The bare, inhospitable landscapes of the American southwest where Francis filmed seem to underscore the idea: the world is not an inviting place, and does not differentiate between the guilty and the innocent. All of us, sinners and saints, are equally likely to be gunned down by a guy in a plane for no goddamn reason.

This is where we start to see glimmers of a personal philosophy through the cracks of these movies. Coleman Francis' work suggests he believed that humans and our institutions are all basically chaotic neutral, doing whatever will benefit us at the moment without much thought for how it affects those around us. Even Beth, when she rejects Joe's advances, does so for selfish reasons: she believes she will be happier as Harry's wife than Joe's mistress. 'Justice' is arbitrary and cruel. Doing evil rarely avails us anything, but neither does doing good, and at the end of the day we're all just brief candles in the void. This is a really depressing way to live your life and makes for some really depressing movies, and I doubt Francis actually thought like this. Rather, I think he made this kind of movie because he thought that's what important movies should be.

Our entertainment culture seems to believe that tragedy is somehow 'more important' than comedy. Quick, name three Shakespeare plays! I bet two of them were Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet, right? Even if those aren't the ones you came up with, I bet at least two, if not all three, were tragedies. Shakespeare wrote nearly twice as many comedies as he did tragedies (eighteen to ten, by most scholars' counts), but it's his tragedies that are endlessly studied and analyzed, that attract big-name actors and win awards to this day, because they're considered more meaningful than the lighthearted comedies.

This is strange, because comedy is important, too. I think Dustin Hoffman's character in Stranger than Fiction had the best explanation of why: it is by affirming the continuance of life (comedy) that we deal with the unavoidable certainty of death (tragedy). The ancient Greeks knew this, and would finish up an afternoon of tragedies with a comedic performance called a Satyr Play, so that the audience wouldn't leave the theatre depressed. Shakespeare knew it, too. Even Hamlet has jokes, and Horatio is left at the end (continuance of life) to pass on the moral of the story (don't wander around making long-winded speeches like Hamlet – get off your butt and overthrow your evil uncle the way your father's ghost told you to... like Simba!)

Stories can accomplish a lot of things. They teach us to deal with hypothetical situations and our own emotions, give us information about places we've never been and people we've never met. One thing that they really shouldn't do, however, is make us feel terrible for no reason, but that's exactly what Coleman Francis' movies do. That's what you get when people are taught that tragedy is somehow meaningful just because it's tragic. It might be sad, but unless it has characters we identify with and situations that are somehow significant, it's still not good.

If you haven't seen Stranger than Fiction, you're missing out. It's a very funny movie about coping with one's own mortality and might just make you cry over the death of Will Ferrell. If you haven't seen The Skydivers... you're good. Don't bother.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Halloween 2017 movie marathon: The Shining (dir. Stanley Kubrick, 1980)

“You've had your whole fucking life to think things over! What good's a few minutes more gonna do you now?!”

Frustrated writer Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson) agrees to spend the winter as the caretaker of the picturesque Overlook Hotel, with his meek wife Wendy (Shelley Duvall) and troubled young son Danny (Danny Lloyd) in tow. Problems brew to a boiling point as the alienated family spends their days in the remote resort: Jack’s encounters with what may or may not be malevolent ghosts bring his already-existing resentment toward his wife and son to the fore, causing him to engage in ever-more sadistic and violent behavior. As his father and the sinister atmosphere of the hotel grow more hostile, Danny, informed by the Overlook’s telepathic chef Halloran (Scatman Crothers) that he has a psychic ability known as “shining,” attempts to contact the outside world before he and his mother are butchered.

As it is with James Whale’s Frankenstein, discussing Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 adaptation of The Shining can prove a daunting task. Everyone and their grandmother seems to have an insane interpretation or conspiracy theory about just what the hell it means. Stephen King enjoys bitching about it every few years. It is endlessly parodied and homaged. But as with James Whale’s Frankenstein, I’m going to talk about it anyway, because my reaction to this movie is a strange one, at least by my standards. When I first saw The Shining, I didn’t find it that scary. If anything, I saw it as more of a black comedy with a lot of suspense. Over repeated visits, most horror movies lose that visceral edge that comes with an initial viewing, but The Shining somehow grows more frightening every time I come back to it—and yet, despite its disturbing themes and eerie atmosphere, I would argue that in Kubrick’s oeuvre, few films are as optimistic. (No, I’m not crazy!) Unfortunately, most of the discourse surrounding this movie is ridiculous, all Illuminati and government conspiracy—but never fear: if you have not seen the film, rest assured that it is a fine horror picture; you do not require a tinfoil hat to enjoy its considerable artistic merits and entertainment value.

Placed alongside the other horror movies I’ve covered in this marathon thus far, The Shining does not seem particularly gothic: it lacks the chiaroscuro aesthetic of Frankenstein or The Mummy. Compared to The Cat and the Canary and subsequent haunted house films, The Shining’s Overlook Hotel is picturesque and contemporary, with not a hint of dust or decay to be seen on the premises. Everything is bright and well-lit—perhaps even over-lit and garish. There are no shadows hiding ghouls or spooky paintings, only kitschy 1970s decor. But if there is a running theme throughout this film, it’s making normal things look as creepy as possible. The stillness of the abandoned hotel, not to mention the way these already disturbed characters are kept in close quarters within it, creates an eerie atmosphere from the moment the Torrance clan set foot on the premises.

Like all great gothic stories, The Shining concerns itself with how the horrors of the past linger in the present, and the Overlook Hotel has no shortage in that regard. Despite its glamorous past, where the “jet set” of the 1920s and 1930s used to hang in the lavish ball room, the Overlook has its share of atrocities, such as the desecration of the Native American burial ground it was built over or the young family slaughtered by the former caretaker a decade before the events of the film take place. The Torrances bring their own baggage: Jack and Wendy’s marriage is already strained, and Jack’s one instance of drink-induced physical abuse of Danny has marred the family dynamic even further. Evil is a constant presence in this film; it infuses the hotel and Jack’s mind, though slowly. Much of the suspense comes from this slowness; I think Kubrick is the only filmmaker who could make the audience jump out of their seat just by throwing an intertitle at us unexpectedly (I’m not even kidding). A series of intertitles are inserted between segments, counting down to the climax where Jack decides he might want to give the whole “murder my wife and child” thing a try. These measurements of time start out broad, but slowly become more specific, counting down to the minute. It is such a simple strategy, but an effective one in making us fear for the more sympathetic characters.

And that’s not getting into the ghosts! I’m not often frightened by paranormal stories, but The Shining’s ghouls are the sort that make you nervous about getting out of bed to use the bathroom at night (I know this from experience). The famous Steadicam use adds to the ghostly ambiance, gliding swiftly through the Overlook’s labyrinthine corridors. The iconic tricycle sequences are so creepy because the camera movement makes it seem as though Danny is being stalked by something. Then there are the ghosts themselves, who manage to be incredibly scary without ridiculous spectacle. The creepy twins are ingrained into the popular culture, of course, but I’m especially unnerved by the eroticized woman in the bathtub or Charles Grady, the former caretaker played by Kubrick regular Philip Stone. There’s something far, far more malevolent about them, as they both represent Jack’s ultimate desire: to break free of his family by any means necessary. They also possess a stillness that makes them creepier than any CG-generated ghoul could ever dream of being (see the remake of The Haunting if you need ample proof of that).

Unlike the book, we are never given extensive backstory for any of these characters; however, Kubrick and co-writer Diane Johnson are wise to allow us to make our own inferences about the messed-up family life of the Torrances just from the way they behave around one another, because this approach prevents the movie from being bogged down by too much verbal exposition. When the Torrances in public or attempting to be “normal” in private, their conversations are bland and trite—even strained— almost like people re-enacting normality, the kind of family bonds you might see on televised sitcoms. Jack’s feelings toward Danny are ambiguous; I can never quite decide if part of him loves “the little son of a bitch” or if he’s always resented him. The scene where Danny sits on Jack’s lap and asks him if he would ever hurt him or Wendy might be the most uncomfortable scene in the movie: the way Jack plants a kiss on his son’s forehead feels performative, forced, just like his unconvincing denial that he would ever hurt his family. However, it’s clear his marriage was never ideal. Not once does Jack ever look upon Wendy with anything other than barely contained contempt or tolerance. One gets the feeling that Jack probably married Wendy out of obligation rather than love, while the opposite was true for her. From her frumpy wardrobe and intense efforts to be supportive, Wendy comes off as a woman who has settled—and settled hard. Her few moments of joy in the hotel are with Danny, such as when they run through the Overlook Maze for the first time.

Kubrick is often accused of being a “cold” filmmaker, but the strong love Wendy feels toward Danny in this film belies any argument that this adaptation has no emotional core. I know some people find Shelley Duvall’s Wendy annoying, but I could not disagree more. She is heartbreaking and believable as a woman with so little confidence that she tries to make a miserable marriage to an abusive man work. She’s trying to make the best of a bad situation, but even she has her limits and that limit is Danny’s well-being. Once she believes Jack is a hazard to her son once again, she is fully against him and fights like hell to survive the night. Danny Lloyd gives one of the best child performances I’ve ever seen in a movie. He captures both the alienation and cleverness of this young boy, all without precocious cuteness or terrible line readings. By the end of the movie, both Wendy and Danny have to rely on their inner strength and wits to escape Jack, who gradually becomes more beast-like as the ghosts of the past overtake what little tolerance he already had in regards to his wife and child.

I don’t think anyone in their right mind would argue Kubrick is a feel-good filmmaker; most of his mature films criticize society, emphasize the absurd tragedy of the human condition, and border on nihilism in their philosophy. However, after 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Shining has the closest thing to a happy ending in all of Kubrick’s filmography, even as it does remind us that evil is a constant presence in the human heart. Nevertheless, even if evil is eternal, it can be escaped—and coming from the guy who made such bleak works as A Clockwork Orange and Full Metal Jacket, that is quite a sunny message! As a psychological horror movie, it remains influential, with The Babadook, Black Swan, and The Neon Demon being just three recent films which have felt its impact. It is a work which bears repeat viewing well; for most, repeat viewings might be necessary. I’ve seen it four times and I still haven’t gotten a solid interpretation of it yet, and this keeps it evergreen.

#the shining#stanley kubrick#stephen king#jack nicholson#shelley duvall#danny lloyd#scatman crothers#horror#1980s#thoughts#halloween 2017#i just realized all the screenshots i used were two-shots#oh well i dont care

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Listed: Eye

(Photo by Kim Pieters)

Eye is an improvising ensemble from Dunedin, New Zealand. The group comprises original members Peter Stapleton (of the Vacuum, Victor Dimisich Band, Pin Group, Terminals, Scorched Earth Policy, Dadamah, Rain, Flies Inside The Sun) on percussion, radio, and electronics; Peter Porteous (Lapdog, Empirical) on guitar and singing bowls; and relatively recent recruit Jon Chapman (Double Leopards, Rory Storm and the Invaders) on electronics. They that first convened in 2003 and have kept a low profile, playing very occasionally on New Zealand’s south island and releasing a trickle of records on various mico-labels before teaming up with Ba Da Bing! This association seems to have kicked things into high gear; since 2015 they’ve issued an LP and a cassette that scratch the same ineradicable itch as recent Dead C. All three members of Eye contributed to this list, which they characterize as “a random list of music/film/books/epiphanies.”

SOUND EPIPHANIES

(PS) – Working several decks down in the empty holds of bulk carriers at the port of Lyttelton and hearing the huge natural reverb on the clash of steel on steel anytime the ball of the crane hit the sides. Also …a childhood memory of massed cicadas in the trees at the height of summer in Christchurch sounding like the roar of the sea.

(PP) – Living in London in the early ‘90s, I was walking along a street when I heard the most incredible music up ahead (some version of Bailter Space, I thought to myself?). I quickened my pace, got to the corner and turned it to be confronted with a group of workmen digging up the road. I stood there for fully ten minutes, conflicting thoughts racing around my brain: “it’s not music… but it sounds amazing… but it’s not music… but it sounds amazing… .” That day changed something in my brain.

(JC) – The wonky, ancient, pressed-cardboard window fan of childhood summer nights; the dual fans’ drones diced up the nearby highway’s thalassic ebbs and the backyard’s bedtime chirruping. Alternately lulling and compelling. Later, re-absorbed by its corollary during sweaty graveyard shifts in a vast plastics factory amongst hundreds of rattle-patterns from the punching machines.

MUSIC

youtube

The Velvets’ ‘Sister Ray’ (and its lesser sibling, the long-form Silver Factory jam, Symphony of Sound) as being a marker and source of inspiration and permission – immersive duration and eminent distortion, feedback, structure under degrees of chaos, guts, the ecstatic emergent. Seeing.

youtube

youtube

The two Thises: This Heat (UK) and This Kind of Punishment (NZ). Coming out of/into punk/post-punk. Two new freedoms, oceans apart — still unlike anything else: urgent, elegant, potent, raw.

youtube

John Coltrane – (paraphrasing US chef Anthony Bourdain) happiness is sautéing onions and garlic to the beginning of Kulu Sé Mama. Occasionally wondering whether to throw away any record which is not by John Coltrane.

FILM

youtube

Tarkovsky. Stalker, a wondrous dream. Filmed in the ravaged eastern bloc with a sense of austere beauty, the captivating idea that there is a room in the Zone where wishes can come true; the scientist and the writer whose dreams illustrate different takes on humanity. Aching long-take slowness, the grace he finds in light: the magnetising shot in The Mirror, where an absent teacup’s steam ring swiftly dissipates from a polished tabletop.

youtube

The Holy Mountain, The carnival rapture of Jodorowsky’s divine kaleidoscope.

youtube

Chris Marker’s La Jetée – always mysterious even after many viewings, but addictive and naggingly prescient. In particular, the whispering sticks in the head.

LITERATURE

(PP) – Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon, the huge wonderful meta-novel set immediately post-WWII in lawless Europe, following endless tribes crisscrossing the landscape on their way home. Convoluted plots, a cast of thousands, science, philosophy, poetry, suppressed histories, slapstick comedy, darkness and depravity as a response to war. Vectors of desire.

(JC) — On Wings of Song by Thomas Disch. Via singing plus electronics, citizens discorporate and fly free through a 21st century where Christian Right Middle America is radically separated from the decadent Coastal Elites. Art and repression, and a metaphor for LGBT liberation.

(PS) – Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy - from beginning to end the bodies just pile up until you can almost smell them rotting in the hot sun, but even the bleakness is kind of poetic.

#dusted magazine#listed#eye#peter stapleton#peter porteous#jon chapman#found sounds#velvet underground#this heat#this kind of punishment#john coltrane#andrei tarkovsky#alejandro jodorowsky#Chris Marker#thomas pynchon#thomas disch#cormac mccarthy

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

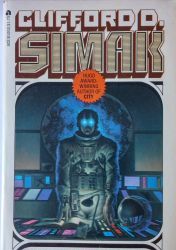

Review: Clifford D. Simak, “Time and Again”

For almost a decade, my father and I have been playing this game where he recommends me an amazing piece of pulpy retro sf and then, caught in the rush of work and the vicissitudes of life, it takes me about two years to read it because I only seem to “have time” during holidays and breaks. The first was The Space Merchants (1953), a brilliant, biting novel co-written by the inimitable duo of Frederik Pohl and C.M. Kornbluth which was brutally satirizing 1950s advertising and consumer culture way before Mad Men made it cool. Issued mid-high school, I managed to squeeze it in between my senior year AP exams and the start of my post-graduation summer job. The second was Gateway (1977), also penned by Pohl, whose dual story threads tracked a dangerous Russian roulette-like space exploration program and the psychotherapy sessions of a traumatized former explorer. With an original loan date in the summer just before I left for my junior year study abroad, fate eventually intervened and put it on the syllabus to a class I was taking… in my first semester of graduate school. The latest was Clifford D. Simak’s Time and Again (1951), which, after the customary two years gathering dust beside my books for work, I finally managed to finish when a bomb cyclone and ensuing polar vortex shut down life in the Northeast US as we know it.

To the untrained (read: ungenerous) eye, Time and Again is a typical 50s sf yarn with a mystery premise like something out of Jonathan Creek. Twenty years ago, burly white male protagonist du jour Asher Sutton was sent to recon a mysterious planet. In the present, with no warning or explanation, Sutton’s ship returns to Earth, battered beyond repair but still somehow flying. Based on calculations by the boys in the lab, there’s no scientifically explicable way Sutton could have survived the destruction of the ship and the trip back to Earth. So how, asks the dust jacket, is he back, seemingly alive and well? It’s the kind of question entirely typical of sf at this time – how did our intrepid Campbell-esque engineer hero MacGyver his way out of certain death using only his wits and good old science? It, in turn, begs the kind of answer you’d have to animatedly diagram on a napkin while babbling about mirrors and ricochet effects and tricks of the light.

And yet Time and Again almost immediately undercuts this mystery when it admits the answer practically on the first page: Sutton didn’t survive. He died, and a mystical force – a secondary being tagging along in his consciousness that Sutton nicknames “Johnny” – is responsible for bringing him back from the dead. Thrust suddenly into a world where inexplicable Powers That Be can do everything from read and influence the thoughts of others to reverse death and travel through time, Sutton find himself an engineer in a world where science and deductive reasoning counts for very little anymore. In fact, every time Sutton thinks he’s figured something out and acts decisively based on that logic, he’s smacked mockingly in the face by the unreality of his situation. Bouncing from incorrect supposition to incorrect supposition, trying to piece together a complex time-travel paradox in between being drugged, knocked out, beaten up, shot, and even killed a few times, Sutton is an early sf protagonist deeply disenfranchised and wholly at the mercy of the plot.

This, believe it or not, feeds into the central focus of the novel, which is destiny. In Time and Again’s 74th century, capital-m Mankind is very much on the back foot and trying to get back on the front foot by following a twisted version of manifest destiny and colonizing the whole universe. But with so few actual Men left and so many stars yet to conquer, Man has no choice but to create “androids” (not robots, deceptively, but clones) to artificially swell his numbers and provide better universe coverage. Treated like second-class citizens, the beleaguered androids are now making a subtle bid for abolition and legitimacy. What does all this have to do with Sutton, you ask? From his trip to the mysterious planet, Sutton draws a profound epiphany about destiny – that every living thing has a destiny and striking a balance between accepting and questioning one’s destiny is the true route to happiness. Returning to Earth, Sutton plans to write the self-help book to end all self-help books espousing this philosophy of destiny. From clues and individuals sent back in time from the future, Sutton realizes his book has become the ultimate hit – it’s started a war between a faction of android rights activists holding it up as a doctrine of equality and a cadre of Men dead-set on annotating the hell out of it in a Revised edition that reaffirms manly Men’s supremacy. In the middle of it all is Sutton, who in the present day is forced to dodge deadly assassins and seriously pushy book agents alike despite the fact he hasn’t even written the book yet.