#its just the french and the germans who think their language is superior and refuse to participate in the rest of the world

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

We settled out of court for the money he owed me plus 6 weeks of salary, which is less than i wanted but nowhere did i actually sign that i waive my right to give my case to the government anyway, so...

Going into negotiations with my shit ass manager today... been having anxiety sweats all morning

#deciding how much i want to truly fuck over these assholes#plus i used that to threaten him openly that if he doesnt pay by the agreed date im going straight to ak#because this man is a liar and a cheat#on top of being a racist authoritarian piece of shit excuse for a human being#ive managed to put a dent in his reputation tho in these paat months#this idiot is putting his harrassment and lies in Writing! all i have to do is share the photo#and he makes himself look dilusional and mad with power all on his own#tho i gotta hand him that his english has improved in the last 6 months of our battle#for a guy who working at a place for 12 years literally with intercultural integration and communication#his english was embarassing#and im not one of those usamericans who demands everyone speak english#i speak 3 other languages take your pick#monolingual germans demanding 'sprecht deutsch' make me so mad#LEARN ANOTHER LANGUAGE#yall are worse than usamericans fr fr#at least 1/3 of usa speaks spanish and half of all americans are bilingual#even the spaniards i meet who speak shit english are bilingual in catalan or portugese or something#its just the french and the germans who think their language is superior and refuse to participate in the rest of the world#ok yea this got off topic in a major way in the tags. but its my own post i do what i want

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sorry but Germans didn't "refuse to rape" Italian women. They were allies! This is a terrible point to bring up in your favor anyways when Mussolini is a great example of Italians claiming superiority over lesser races (not to mention the internal racism towards the south which goes on to this day and you somehow fail to bring up). Like sorry to break it you but you're not oppressed and you're not a poc. And why do you care so much to have your oppressed person card validated? So your opinion holds more sway with the Americans? Why do you care so much what Americans think? They don't know anything anyways.

Anon, just a quick couple of questions: when did Fascism fall in Italy? And what are the movies Rome Open City, Paisan, and Miracle at St. Anna by Spike Lee, if your tastes strive more for the modern and American cinematography, about? And if it's necessary for a country to be allied with another country for their soldiers to not harm anyone, why did the Moroccan groumiers paid by the allied French government rape thousands of people, including children and the elderly, in May 1944? And how is South Italy a different race, all of a sudden, when we have the same genetic make-up?

Quick answers, because I know no one will look up them:

Fascism didn't fall in 1945, but in July 1943. This meant a sudden shift in allies and enemies, meaning that the Germans roaming our streets were suddenly enemies and could do as they pleased, including raping, arresting, killing, and torturing. The reason they didn't do the former is because they didn't consider Italians as white and worthy of them. They were pretty happy to be finally able to murder us, though, and my family is from the North and my great aunt has some pretty horrific stories about that, so... no, there is literally no difference in North VS South, regarding this;

All those movies are about this time period. All of them. We spent two years out of five prisoners of our own country - and honestly because of our own hand, but the issue is a lot more complicated than that, because the rise to power of Mussolini didn't go as smoothly and hadn't been as direct as Hitler's;

And here's the thing: enemies or allies, during war, doesn't matter. It doesn't matter at all. The shitty men who made "Ukrainian girl" trend on PornHub exist now just like how they existed in the Forties, those ones just didn't have access to modern technology. Being allied means really little. Again, look at the Moroccan groumiers!;

The only people in Italy who have a different genetic make-up are Sardinians, because that's an ethnicity in and on itself, with its own language and that has developed a DNA completely different from the rest of the peninsula - they can be compared to Sámi people. You can't say "Southern Italians are a different race from Northerns" unless you bring out """studies""" from the late 1800s/early 1900s that were highly influenced by the American Eugenics movement, and usually when people bring out craniometry is the moment I dip. But to explain it quickly: Italy has been a united country for only 160 years. In the centuries our regions were separated as different states, we were invaded by different populations and developed completely different languages and cultures and economies. Here is where most of our clash resides, not in skin color, you idiot sandwich.

About the oppression train... anon, please.

I've mentioned this before, but I happen to work for a lot of Americans. Some of them tried to correct me on how to write and read my own last name because, according to them, I spelled and pronounced it incorrectly. My work is usually a lot more pristine than a lot of my colleagues', and it doesn't need anything but "light revisions" until the person who is going through it hears me talk, and at that point it suddenly needs a second or third round of heavy editing and checking. I've once had a lady study my face for about six hours while I was wrangling equipment and the child she was not supposed to bring, and then tell me to pull down my mask so that she could understand what "exotic race" I was. American men have told me that there's no reason as to why I should have a job or keep studying because there's plenty of rich men willing to take me in because they'd like an exotic wife with an exotic accent.

I've had Americans tell me that, because I'm Italian, I'm therefore not white, just Italian because we are apparently "difficult to place" in the magical race spectrum.

Now... do we think that Alyssa from the Netherlands or Pernilla from Finland receive this kind of treatment? Because I do know Alyssas and Pernillas, and they sure as fuck don't receive this kind of unrequited comments.

And I said this before, and I'll say this again: if they considered me white, like they do with most people who write bullshit in the TOG fandom, they wouldn't be constantly trying to trample my years of experience with "well, akshually" and "well, in Italy" and "well, you have the history of your own country wrong so let me correct it with misinformation", of which you are a prime example.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

People, what is somethings you wish writers knew about your culture, I'll start (I'm English):

If you say British-English I will riot. It's standard English, American English is just the most commonly spoken version of English, being the dominant culture

Nobody cares about sports at Secondary school, I didn't realise my school had sports teams until like year 11 when I saw them leaving and it was just a casual observation

Also Primary school = reception to year 6 or ages 4 to 11, Secondary school = years 7 to 11 or ages 11 to 16, Sixth Form (attached to a secondary school) and college (independent from a secondary school but otherwise same thing) = 16 to 18. Primary school to Secondary school is compulsory, after that you have to attend some form of further education whether that be an apprenticeship or sixth form/college is up to you. It is common to have a compulsory uniform for secondary school and less common for both primary school and sixth form/college. Primary school and sixth form/college uniforms are noteworthy whereas a lack of compulsory uniform in secondary school is noteworthy

American culture is the dominant one, we have watched and read a lot of American media

If you're poor, you live in a council flat and probably have free school meals, "trailer trash" isn't really a thing because trailers just aren't a common occurrence, the only group I can think of that commonly lives in "trailers" is 'gypsy' who are their own community and live in motorhomes. Discrimination against them is common but not in your face, which I will explain in a bit because that is its own point

People care a lot about both rugby and football and if you call it soccer and act all superior about you will make a lot of people mad because British football officially came first and a lot of languages call it something that sounds very close to football in their language and American football is closer to rugby in how it looks to us so it is a very sore point

Also, in case you haven't gathered, Britain is subtly anti-American we had an empire and we are bitter we lost it so seeing America get to where we were is something Britain does not react well to

British culture is all about pretending everything so normal and subduing, ignoring and otherwise refusing to acknowledge what strays from that "normal" so unless we are forced to openly acknowledge it we will not and then we will passive aggressively snipe at it. American culture is all about being in your face, British culture is all about pretending we don't see what's wrong. We refuse to acknowledge we even had an empire

Class is a big deal. The elites in our culture have historically been their own one and this is still seen today. Class divide is what defines us. We have things like the house of commons and the house of lords. Rather than the rich ending up in positions of power due to society falling to prevent their privilege, British culture and actively encourages elite power. There is still discrimination but because of the importance of class divide and the British refusal to acknowledge our own faults, it presents differently. Race is seen as it's own class below working class and there is discrimination between the white classes. The working class are seen as beneath the rich and the rich are seen as 'upperclass tw**s'. The middle class are then seen as traitors and having abandoned the working class because the elite government has purposefully drafted policies to ensure that happens

Also,all of the above applies to English culture. There are three countries in Great Britain and 4 countries in the UK. England, Wales, Scotland and North Ireland and the divide between these countries is clear. Scotland actively hates England, Wales passive aggressively hates us and Ireland is a mess we created (I would suggest waiting for someone who is Irish to explain that because I don't know enough about it and it is an incredibly complicated topic which plays a significant role in politics)

Also we dislike the French, Britain and France are rivals because we have been fighting on and off for centuries but the French are still seen as equals. We dislike them but we will fight alongside them if if comes to it

Also accents are important, because of the class divide, if you have a working class accent you are being discriminated against, if you have a posh accent you will be hated but people will respect your 'authority', no matter how much they hate

Oxbridge is elitist but there are so many other great Unis across the UK

To American media specifically, stop romanticising British culture, I have never seen the academia aesthetic you are portraying and it irritates, we are not just the rich upper class, look at our history people you portray and because of the class divide it hurts to see that as our only representation

Also London is its own thing, Britain does not recognise London as representative of Britain and London does not like everywhere that is London, it is the most diverse and the biggest city in the entirety of England by a large margin, it does not feel like the rest of Britain

On that point, there are many, many other cities and other towns outside of London, please acknowledge them (having never been to a lot of cities I can't explain them to you)

London does have divides within it such as the divide between North and South of the river, the South does not want to be part of London and the North refuses to acknowledge it. The Northern edge of London is also up for debate, for me it is the edge of Zone 3 (on a tube map) and the other side of the North circular by car but for others it might be further in or out so be aware of that. There is also divide between the post codes for example Wood Green and Tottenham, both have the same council (Haringey) but there is a clear divide between them only further emphasises by Haringey having two MPs one for Tottenham (David Lammey) and one for Wood Green and Hornsey. Both Wood Green and Tottenham have bad reps but the Wood Green half of Haringey starts drifting into middle class at its edges with Hornsey being solidly middle class so be aware of the variation in boroughs

And, London has no centre. It is a city that grew with its country and absorbed the surrounding towns. So if you say the centre of London people will assume you mean a specific part in zone 1 but will not know which part you are talking about and will assume you are talking in a generalisation. If they are traveling with you though, they will expect further clarification, don't say the centre and expect me to know where

Also, there is no space between houses in England, they are mostly semi-detached. I once watched an episode of escape to the country where someone tried to find a detached house and just struggled massively. You either have to pay loads of money or be in the middle of nowhere before your house is fully detached and it will still be only the same distance away from another house as the average American house is. We have one of the highest populations in Europe but a small land mass

Going on from that, Britain is definitely European and has a lot of shared culture whilst still obviously being it's own thing (like every single other country) but Britain acts like and will get mad at the suggestion that they are European like any other European country because 'we are entirely seperate and on an island and how can we not have become our own thing' the actual variation is because Rome (contrary to what the school system will teach you) had very little impact on Britain so we aren't as similar to the other Latin speaking countries as is expected, the main reason we are still similar is because of the impact of Norman conquest. Also everyone underestimated the effect of Scandinavian and Germanic culture on Britain because we act like all they did was pillage when in fact they settled down and where embraced by Briton (unlike Rome which did actually pillage and subjugate Britain without being widely accepted) so that's why there is variation. We are very European but not in the way people expect so Britain refuses to acknowledge it

Honestly British culture is a lesson in tolerance versus acceptance. But there is still active discrimination as people of colour and the LGBTQ+ can attest

Also Christianity is baked into Britain to the point that even atheists follow Christian customs without questioning it but significantly less extreme than France which just stops on Sundays (but is acknowledged as a Christian country so you know) and 'pagan' - so, in this case, Celtic, anglosaxon and Norse - culture has effected us being carried down in fairy tales and witchcraft

Some of this will be upsetting to many people as it should be because British culture hurts, it discriminates without acknowledging it and I want people to know that. I want people to see that when they write about it because the alternative is writing about Britain as if it has faults and that would be so much worse. So writers, please bear all of this in mind when talking about Britain, even and especially, the ugly parts

This has been a white, middle class, Londoners, perspective on Britain and no I will not call myself English because the divide between England and London means that being a Londoner rather than just English matters in this context

I would recommend listening to the perspective of Brits from other groups, such as England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland, working class, upper class, Brit of colour, non-passing queer folk, Muslim, Hindu, Indian (the largest immigrant group is actually Indian and that's just immigrated in their lifetime rather than born British and Indian), Jewish (especially Jewish I can talk about that on another post but let's just say the Jewish have never been accepted but always been part of Europe) and so on, to get a more comprehensive view of Britain

#british#writers on tumblr#history#perspective#this was upsetting to write#my country needs to change#discrimination#english

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Agreement: Part 4

The clock is ticking and the race to win Steve Trevor’s heart has begun. But with his memory of Diana completely erased, the warrior from Themyscira must find a way to gain his trust, and eventually his love, in a world that is completely foreign to him. Without the dangers of war and imminent death, Diana has to find a way to help her fellow soldier adjust.

Author’s Note: This is kind of a “filler” chapter. But I had to put in there or else the rest of the story wouldn’t make sense.

Feedback is greatly appreciated and encouraged!

Rating: M

Word Count: 1784

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 |

“I look forward to meeting you again, Diana Prince.”

The words rang in her ears as she waited for Steve to wake up. Leaving the darkness of the cave somehow caused Steve to collapse onto the wet rocks. By the grace of the gods, she managed to catch him, avoiding any injury. Diana determined Hades must have enchanted the exit as part of their deal. The storm outside that was crashing all around them, had finally calmed to murky gray waters. Steve laid peaceful on his back, breathing at a soft and rhythmic pace. She couldn't help but reach out to stroke the prickly stubble on his cheek. She retracted quickly, however, when his long eyelashes began batting wildly.

“Steve?” Diana whispered, forgetting that she was now a complete stranger to him. Steve was finally able to open his eyes and came face to face with one of the most beautiful creatures he has ever seen.

“Wow.” slipped out of his mouth before he could even stop himself. Diana smiled, despite the twinge of pain from a long lost memory. “Are you hurt?” Diana questioned, checking his head for any blood or sign of injury. Steve shook his head no as he lifted himself upward. Together, they slowly rose to their feet. The spy realized he actually had no idea where he was or who the woman is who saved him.

“Who are you? Where are we?” Steve asked frantically. The last thing he remembered was a flying a plane into the sky and flashes of golden light encompassing him. Now he’s standing on a misty shore with a goddess of a woman. “Am I dead? Is this heaven?” He scrunched his dark brown eyebrows in confusion. “If this really is heaven”, he thought to himself, “it’s pretty hideous”. The woman who helped him turned from looking out into the distance, to face him. He noticed that she had been crying. Her eyes were puffy and red, but somehow that still didn’t mitigate her beauty.

“My name is Diana of Themy-” Diana stopped herself. She wasn’t sure how much of her story she should tell him at the moment. Most of her history Steve understood because he was there, he met her people. But now, she was just another woman to him. “My name is Diana Prince. We are on an island in the Mediterranean.” Steve looked at her in confusion. How did he end up in the Mediterranean? He was in Belgium before he woke up.

“I need to go back to my post. I am a pilot for the American Forces and I have to check in with my superiors.” He started descending down the rocky cliff to a wooden boat he saw sitting on the shoreline. Diana recognized the seal on its bow as Zeus’ lightning bolt. Diana called out to Steve as she fell in line with his quick pace. She grabbed his shoulder and stood in front of him.

“Steve, slow down.” the Amazon pleaded. The sound of his name caused the pilot to stop midstep. “How do you know my name?” He asked suspiciously. The soft blue eyes that Diana loved so much began hardening. Whatever trust they shared moments ago seemed to be dwindling. “You told me when you first woke up. You kept saying ‘Steve Trevor. Serial Number 8141921’. But soon after, you fell unconscious again.” Diana quickly fabricated, hoping it would be a satisfactory explanation. Steve didn’t fully accept her story but decided not to question it. “I have a home in Paris that you can stay in, if you would like. And I can explain everything on the way.” She stepped into the boat and began letting down the sails. Steve, deciding he could take another ship to London from Paris, agreed and pushed the boat into the sea, before hopping in himself.

The two sat under the same night sky, just as they did a hundred years ago. The dark waters lapped against the side of the ship so quietly, it was making Steve’s eyes grow heavy. But he was still a little suspicious of his shipmate, who was currently making them a place to sleep.

“You will sleep with me, yes?” Diana asked innocently. The pilot eyes were now wide awake and a rush of color graced his smooth cheeks. “Um, I don’t think that’s a good idea. ” Steve trailed off, scratching the back of his neck nervously. He started pacing around the boat and mindlessly pulling on the sails.

“Are you not tired?” Diana asked as she made herself comfortable on the makeshift bed. Steve, even more embarrassed now that she actually meant going to sleep, stopped moving. “Yeah, I guess. If you don’t mind me…” Diana quickly cut him off, “I do not mind”. Steve relaxed a little and walked back to the front of the ship. Once he joined Diana in what would serve as tonight’s sleeping quarters, the Queen finally decided to break her silence. She knew that they would be at the French border soon, and there would be no way of hiding the modern world from him. After a few beats of silence, Diana could no longer hold her tongue.

“Steve, do you know what year it is?” Diana whispered. Steve scrunched his eyebrows in confusion, but confidently answered “1918.” A sigh was slipped out, and the Amazon turned to her side. It would be hard for him to believe her without having actually seen the new world. But she hoped giving him an explanation would lessen the shock.

“There is so much I have to explain.” She paused “You have been away from this world for a very long time. The war you believe you are still fighting for, has ended. In all honesty, the world that you knew of, has ended.” Diana confessed to him. Steve looked at her as if she was speaking a foreign language. But the warrior queen kept speaking softly. “It’s the year 2018. You’ve been gone a century.”

She waited for what felt like centuries for his response. Anger, confusion, sadness, something to let her know that he had fully comprehended what she was relaying to him. But she got none of that. Instead, she heard rhythmic breathing. Looking up at him, Diana realized that Steve had fallen asleep. Even though he couldn’t recount all the memories they shared together, it had been a pretty exhausting day for both of them. She decided to finally follow suit with her past lover, and let the melatonin take over her body. She had tomorrow to explain everything.

*** ��

“Who do you work for?”

The Amazon awoke from her slumber to find her hands and feet tied together. Steve stood a few feet away, clearly confused and anxious. Diana could easy free herself from her binds, but she didn’t want to alert Steve any more than she already had. All around him were buildings that were completely foreign to him. He wanted to believe that France had not changed that much since his last visit the month prior, but it wasn’t anything like he remembered. Something was different and the only person who could tell him what it was, was the stranger who brought him.

“Steve.” Diana tried to sit up straight, but as she moved, Steve, for the first time, got a real look at her armor. He didn’t recognize the symbols as war seals, but he had to be sure. “Who do you work for? The Germans?” She tried to deny it, but the spy still refused to believe her. Steve maneuvered his way to the other side of the ship, making sure to keep his eyes on her as he went. And before the worker on the dock could even tie the ship down, Steve hopped out of the boat and started running. He didn’t know where his legs were taking him, but he needed to find something he recognized or hear a familiar voice. “Candy!” Steve thought to himself. He’ll find a phone and call her, maybe she can explain to him what’s going on.

Diana watched Steve run away from her. As much as she wanted to explain the situation to him, it was too drastic of a change for him to understand without seeing it for himself. Quickly, Diana freed herself from the rope with a simple pull of the wrist and ankles. She followed him as best she could without being seen. She didn’t want her armor to alarm the citizens. Climbing up on the roofs of beige brick office buildings, the Amazon followed him from above. It wasn’t long before Steve ran into a busy main street filled with honking cars, zooming mopeds, and people. The overwhelming stimulates was such a shock to Steve that he took a few steps back until he found a quiet alley. He stood there, hunched over with his hands on his knees, trying to catch his breath. As much as he hated to admit it, he was scared.

Finally, Diana was able to catch up and didn’t hesitate for a second to be by his side. She put a gentle hand on his back and tried comforting him. When it seemed like his heart rate was back to normal, Diana softly explained again.

“Steve, the world that you knew of no longer exists. You’ve been gone a century.” Steve’s deep blue eyes looked at her and she could almost feel every ounce of fear in them. “It's 2018. The war you fought so gallantly for is over. And we won.” She smiled softly despite the few tears that slipped out. “Please believe me.” She begged. He had no other choice but to accept. Reluctantly, Diana left Steve’s side and took a few steps away from him. Pulling out her phone she quickly called her intern at the museum. He was the only one who knew her story. “Tim, I need a ride. We’re in Le Havre. Thank you” Diana quickly hung up and went back to Steve. Together they waited for the car to arrive in silence. Steve was still in shock, despite trying to do his best not to show it. He lost hundred years of life. All his friends are dead. The few members of his family that were left are gone. He was completely alone. Diana took a quick glance at the man beside her. The Steve she knew was confident but caring. Sarcastic, yet loving. But looking at him staring blankly at the brick wall in front of him. He was like a shell. And for the first time ever, the Queen of the Amazons began doubting her ability to win her bet with Hades.

#Wonder Woman#wonder woman fanfiction#wondersteve#wondertrev#ww#steve trevor#steve trevor imagine#steve trevor fanfiction#chris pine#DC comics#dc comics fanfiction#dceu#dceu fanfiction#aercia13#honeybeetrash#no-man-an-island#wefracturedmotivation#Gal Gadot#the agreement#My writing#mine

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Beginner’s Guide to the Underappreciated Pencil

Editor’s note: This is a guest article from TJ Cosgrove.

For most people, the humble pencil is a writing utensil that was once familiar, but is now largely absent from their everyday life.

When you were a kid, you used a #2 pencil to fill out the answer sheet bubbles on standardized tests. Maybe you kept using the mechanical kind to do math in college. But as an adult, unless you’re a craftsman making marks on lumber or drywall, you may not use pencils at all, having dropped them in favor of pens.

I don’t entirely blame you. A yellow Ticonderoga or a plastic mechanical pencil offered very little in terms of real pleasure. With a scratchy tip, or lead that constantly snapped off, pens seemed to offer a superior, smoother, more indelible writing experience.

But there’s more to pencils than the kind you used as a kid. Upgrades in the pencil’s core, and in the wood which surrounds it, can make a big difference in how satisfying it is to write with. So if you don’t think pencils are for you, but have never used anything but the drugstore variety, you just may not have tried the right one yet.

Today I’ll unpack the surprisingly nuanced world of these underappreciated writing utensils, explaining their various features/qualities and offering some suggestions for branching out from the kind you grew up with.

Why Use a Pencil?

When you try out writing with a nicer pencil, you’ll likely be quite surprised by how differently — and more winningly — it writes than you’re expecting.

A quality pencil, in fact, can provide a tactile writing experience that not only rivals that of a pen, but in many cases surpasses it. There’s just something that feels very connected when laying down brainwaves in streaks of carbon on wafers of cellulose.

While the friction of a quality pencil on paper is much smoother than you might imagine, there’s also something about the way it leaves its essence behind — becoming smaller as you use it, extinguishing itself as it brings your words and scribbles to life. There’s something too about a pencil’s natural construction — a wood case surrounding a core of graphite and clay — and about the fact you have to continually sharpen it to keep it keen; this repeated whittling-in-miniature, complete with little curls of wood or bits of sawdust, offers a tangible pleasure . . . and an apt metaphor for life.

Beyond the more ineffable pleasures of the pencil, are its eminently utilitarian qualities. Unassumingly simple, pencils are steadfast and dependable tools: there’s no battery to charge or signal to lose; there’s no ink that can leak or unexpectedly run out. Pencils work in any language, on almost every medium, and in wind, under water (at least if you have the right writing surface!), or in zero gravity. And of course with its double-sided design — a point on one end and an eraser on the other — they can be used for both creation, and destruction.

Both functional and aesthetically pleasing, once you start incorporating quality pencils into your life, you may find it’s your pens that increasingly get left in the desk drawer.

The Qualities of a Pencil

Grade

It is a common myth that the core of pencils used to be made from lead. The misnomer can be traced to the 17th century, when a particularly violent storm felled a large tree in England and its roots unearthed a dark metallic substance — raw graphite. Farmers started using it to mark their sheep, christening it “plumbago” or “black lead.” The name, catchy though erroneous, stuck. (Interestingly though, in years gone by it was not impossible to get lead poisoning from chewing your pencil, as they were often lacquered with lead-based paint.)

The core of a pencil has actually long been made of a combination of clay and graphite, and the ratio of these two components gives the pencil its “grade.”

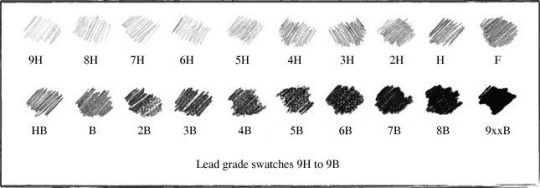

Pencils are categorized primarily through this grading, which is measured by two major scales: the European HB scale and the American # number scale.

The European system was originally created in 1789 by Bohemian pencil titan Josef Hardtmuth and measures Hardness against Blackness. HB is the center of the scale: equal parts Hardness (clay) and Blackness (graphite).

The HB grading scale. Image Source

As we move up or down the scale, additional clay makes the pencils physically harder and their marks lighter, while additional graphite makes the pencil softer and much darker on the page.

The American system (coined by 18th century French inventor Nicolas-Jacques Conte) uses numbers, often paired with a pound sign. #2 is the middle grading and the closest approximate to HB. #1 has more clay, and is consequently harder and lighter, while a #3 has more graphite and is darker and softer.

The biggest problem with grading is that users, manufacturers, and even countries do not agree on any kind of standardized grading system. An HB in England is not necessarily the same as an HB in Germany. Don’t even try to use an HB if your teacher asks you to use a #2.

Most readers will have an idea of what a #2/HB pencil feels like. It’s the standard and most common grade. You probably used them to fill in tests or scribble stick people in the margins of your school books. If you’ve ever been to IKEA, you have seen a half pint HB.

As it goes, American and Japanese pencils tend to err on the darker side, while German and other European pencils tend to sit a little lighter on the grading scale. There are of course some exceptions to the rule and a few total outliers who refuse to use a scale at all (looking at you Blackwing . . .).

The most important thing when picking a pencil grade is to ensure it works for you. Too hard and it will feel like writing with a fork tang, too soft and you won’t get half a sentence before you need to sharpen again.

If in doubt, I suggest you go softer and darker. It’s easier on the hand and has better legibility. Try a 2B against your normal #2 and tell me it ain’t nicer to write with.

Lacquer

The lacquer on a pencil is the protective covering for the wood. It stops the wooden barrel from becoming stained with the daily wear and tear of desktop life. It also provides a smooth and consistent texture for the hand to grip.

If I ask you to close your eyes and imagine a pencil, almost everyone will think of a yellow pencil. That’s because it’s the most commonly used color of lacquer, but this was not always true. Until the 1890s, pencils were typically clear lacquered or unfinished, as this allowed consumers to see the high-quality wood that went in to their high-quality writing implement. Poor quality wood was often hidden behind dark maroon, black, or green lacquers.

After the discovery of a new vein of high-quality graphite in Siberia, close to the Chinese border, H&C Hardtmuth started manufacturing pencils from this new source. To promote their new luxury line of “Koh I Noor” pencils, which utilized this superior “oriental” graphite, they chose to lacquer the pencils yellow. The color yellow, while commonplace now, had connotations of superlative quality and royalty associated with the Chinese Yellow Emperor.

The marketing campaign worked, the Koh I Noor pencils sold so well they renamed the company Koh I Noor Hardtmuth (still going today in the Czech Republic), and yellow became the de facto color for woodcase pencils both in the US and most of Europe.

Selecting a pencil with a quality finish is important, as cheap lacquer (which is found on cheap pencils) is unpleasant to the touch and can chip or flake off. Or you may find that you prefer an unlacquered pencil; it does get dirty quickly, but that may be an acceptable trade-off for enjoying the raw wood feel.

Point Retention

Point retention is a measure of how long your pencil comfortably writes before becoming dull, unwieldy, and unpleasant. There is a direct correlation between the grade of pencil you choose and the length of time your point will be viable. Softer pencil tips will round off and widen much faster than their harder brethren.

Point retention is important if you are a long form writer, and don’t want your sessions constantly interrupted by trips to the trash can.

Either choose a harder grade, or take the Steinbeck approach:

Sharpen 24 identical black pencils and place them point up in one of two identical wooden boxes. Then pick up the first pencil and begin writing. When the point dulls (typically after four or five lines) place it in the second box, point down. Continue until all the pencils have been used and migrated to the second box.

Sharpen all pencils again, return to the first box, and repeat as necessary.

Some people can and will write with a nubbin of graphite that is about as sharp as an eggplant. My fiancée, for example, will actively snap a freshly sharpened point in half, then scribble it to get a rounded and inoffensive stylus with which to write. Personally, I prefer something with a little more acuteness in the angularity.

Smudge

Smudge is caused when excess graphite not embedded into the cellulose fibers of the paper is brushed and smeared across it. While actually a feature of pencils when utilized for artistic pursuits, it is unsightly, annoying, and generally frowned upon by writers.

This issue is especially salient for lefties, as the normal hand posture adopted when writing left handed will inevitably lead to significant smudging, leaving a shiny graphite tattoo on the leading edge of their little finger and palm. Best advice: use a harder grade with less graphite or learn to embrace the sheen.

Erasability

Erasability refers to how well a pencil’s mark may be eradicated by way of an eraser (or rubber as we call them here in the UK). The importance of erasability is influenced by the way you write. If you are a perfectionist, then the ability to erase and remark paper is fundamentally important; you can hide your mistakes with the revisionist touch of an eraser. If, like me, you like to show your work, then erasers are an oft-ignored part of your stationery kit. I tend to put a line through errors and carry on, with my mistakes sometimes providing more illumination in retrospect than the answers I eventually came to.

If erasability is important to you, then use a lighter pencil. More clay and less graphite mean a lighter mark which is easier to erase.

Or play with the eraser you use. As with many things, everyone has an opinion on what is best when it comes to rubbers. Cheap erasers tend to produce a fine sprinkling of rubber “dust.” Higher quality ones, at least in my experience, create “curls.” Generally, a separate, off-the-pencil eraser is better quality, and provides a larger surface area; high quality Japanese ones, which are formulated to remove lots of graphite and leave clean pages, come well-recommended. Pencil-top erasers are really put there as an emergency measure, as anyone can attest to when they are almost entirely eroded in rubbing away one mistaken sentence.

If you find yourself in a real emergency, and have no eraser left atop your pencil at all, know that in days of yore, people used a rolled-up piece of bread to clean up their mistakes — which still works in a pinch!

Sharpening Your Pencil

Sharpening can be done in all manner of ways, ranging from rotary desk mounted contraptions to the humble pocket knife.

The more “automated” your sharpener, the less control you have over the shape/size of the resulting point. An electric or hand-crank model will tend to produce a generally inoffensive and practical point, but far better results can be achieved with a hand sharpener or knife.

There are a number of excellent hand sharpeners at a variety of price points. German company KUM makes some excellent higher end ones, including the flagship KUM Masterpiece, which can create long points to rival even the steadiest knife sharpen. Cheap sharpeners can be just fine, and the Indian Apsara long point is a favorite of mine that costs literal pennies and can be bought in bulk directly from India.

If the sharpener leaves a rough finish on the pencil, or the wooden curls are short and flaky, its blade might be blunt. Generally, sharpeners are cheap enough that once this happens, it’s time to move on and replace it.

Sharpening a pencil by hand with a knife will give you the most control of your point, but as this is a personal and nuanced subject, we’ll cover it in a separate piece.

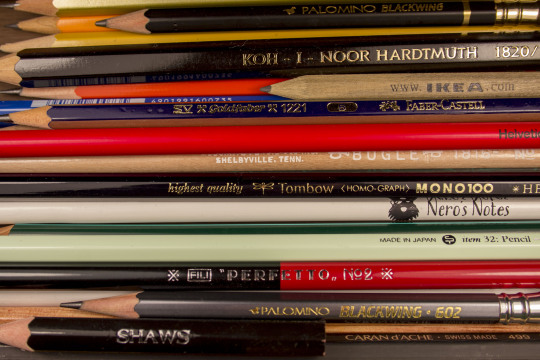

Suggestions for Branching Out From Your Everyday Pencil

If you’ve only ever used the basic pencils of your schooldays, you really owe it to yourself to branch out and explore other kinds. While quality pencils are a little more expensive than the everyday variety, the upgraded price creates a significantly upgraded writing experience.

As with many things, your mileage may vary and personal preference has an enormous impact on what you will ultimately use and enjoy. I thus recommend trying everything and anything you can get your hands on — only then will you know what best suits you. Below you’ll find some of my suggestions, based on where in the world you live.

If you are based in the continental United States, it’s easy and affordable to start experimenting with pencils beyond your normal scope of recognition. There is a whole suite of American companies turning out great writing implements including General Pencil Co, Musgrave, and Palomino.

Most Americans will be familiar with the yellow Dixon Ticonderoga #2, but give the Black Ticonderoga a go for the simple pleasure of mixing up your lacquer colors. For a real step up in quality (without a big jump in price), try the Golden Bear by Palomino; they’re still cheap ($2.95 for 12) but infinitely better.

For a natural unlacquered pencil, try the General’s Cedar Pointe.

If you want to get fancy, then get a pack of Palomino Blackwing 602s; encased in fragrant cedar, with a distinct and enjoyable dark core that lives up to its “Half the pressure, twice the speed” tagline, this is often the “gateway” pencil that changes people’s minds about pencils.

If you’re in Europe, there are plenty of local stationery giants like Staedtler, Koh I Noor, and Faber Castell to peruse.

Most will be familiar with the distinctive yellow and black striped Staedtler Noris HB (the Ticonderoga of Europe) but have a go at the blue and black Staedtler Mars Lumograph in 2B.

For something historic, give the original yellow pencil a go: the Koh I Noor 1500 is available in 20 different grades and remains mostly unchanged since it was introduced 120 years ago.

For something a little different, try the Caran d’Ache Bicolour, a double-ended red and blue pencil often used for marking or amending documents.

Asia is not without its own cabal of manufacturers and brands. Japanese pencils, inspired by the calligraphic nature of kanji, are typically dark and smooth. Tombow and Mitsubishi make some wonderful pencils like the Tombow Mono 100 or Mitsubishi Uni-Star.

Once you start trying different pencils, you may fall down a rabbit hole with them, and really start collecting them in earnest. Happily, pencils are such a constant across the world, that you can go to almost any country and find a shop stocking notebooks and pencils to add to your collection. In the Czech Republic, I trekked from street to street, collecting every kind of Koh I Noor pencil I could find (there is even a pencil shop in Prague Zoo). In China, I haggled for handfuls of Chinese pencils with a market vendor in Xi’an. There has not been a city yet that I haven’t been able to satisfy my pencil cravings in, and finding them always leads me on a new adventure.

But if you’ve rarely picked up a pencil since childhood, you don’t have to travel the globe to experiment; just try branching out a little where you are, and you may find your new favorite tool for conveying your thoughts from cerebrum to cellulose.

___________________________________________________

TJ Cosgrove is a pencil pushing filmmaker. He runs Wood & Graphite the #2 pencil-based video channel on the internet. He also talks about the past and the present in an anachronistic podcast called 1857. He likes hard science fiction novels, pencils and American beer, though not necessarily in that order.

The post A Beginner’s Guide to the Underappreciated Pencil appeared first on The Art of Manliness.

A Beginner’s Guide to the Underappreciated Pencil published first on https://mensproblem.tumblr.com

0 notes

Text

Highlights for Dead Souls

The newcomer was somehow never at a loss and showed himself to be an experienced man of the world. Whatever the conversation, he always knew how to keep up his end: if the talk was of horse breeding, he spoke about horse breeding; if they were speaking of fine dogs, here, too, he made very sensible observations; if the discussion touched upon an investigation conducted by the treasury—he showed that he was not uninformed about legal wiles; if there were some argument about the game of billiards—in the game of billiards, too, he would not go amiss; if they spoke of virtue, on virtue, too, he reasoned very well, tears even came to his eyes; if on the distilling of spirits, then on the distilling of spirits he also knew his stuff; if on customs supervisors and officials, of them, too, he could judge as if he himself had been both an official and a supervisor.

Although, of course, they are not such notable characters, and are what is known as secondary or even tertiary, although the main lines and springs of the poem do not rest on them, and perhaps only occasionally touch and graze them lightly—still, the author is extremely fond of being circumstantial in all things, and in this respect, despite his being a Russian man, he wishes to be as precise as a German.

And in boarding schools, as we know, three main subjects constitute the foundation of human virtue: the French language, indispensable for a happy family life; the pianoforte, to afford a husband agreeable moments; and, finally, the managerial part proper: the crocheting of purses and other surprises.

But Selifan simply could not recall whether he had passed two or three turns. Thinking back and recalling the road somewhat, he realized that there had been many turns, all of which he had skipped. Since a Russian man in a critical moment finds what to do without going into further reasonings, he shouted, after turning right at the next crossroads: “Hup, my honored friends!” and started off at a gallop, thinking little of where the road he had taken would lead him.

A Russian driver has good instinct in place of eyes; as a result, he sometimes goes pumping along at full speed, eyes shut, and always gets somewhere or other.

He is among us everywhere, and is perhaps only wearing a different caftan; but people are light-mindedly unperceptive, and a man in a different caftan seems to them a different man.

Everything is desolate, and the stilled surface of the unresponding element is all the more terrible and deserted after that.

To such worthlessness, pettiness, vileness a man can descend! So changed he can become! Does this resemble the truth? Everything resembles the truth, everything can happen to a man. The now ardent youth would jump back in horror if he were shown his own portrait in old age. So take with you on your way, as you pass from youth’s tender years into stern, hardening manhood, take with you every humane impulse, do not leave them by the wayside, you will not pick them up later! Terrible, dreadful old age looms ahead, and nothing does it give back again!

And so your little shop fell into neglect, and you took to drinking and lying about in the streets, saying all the while: ‘No, it’s a bad world! There’s no life for a Russian man, the Germans keep getting in the way.’

Our ranks and estates are so irritated these days that they take personally whatever appears in printed books: such, evidently, is the mood in the air. It is enough simply to say that there is a stupid man in a certain town, and it already becomes personal; suddenly a gentleman of respectable appearance pops up and shouts: “But I, too, am a man, which means that I, too, am stupid”—in short, he instantly grasps the situation.

a new governor-general had been appointed to the province—an event known to put officials into a state of alarm: there would be reshuffling, reprimanding, lambasting, and all the official belly-wash to which a superior treats his subordinates.

During that time he had the pleasure of experiencing those agreeable moments, familiar to every traveler, when the trunk is all packed and only strings, scraps of paper, and various litter are strewn about the room, when a man belongs neither to the road nor to sitting in place,

but he came out just as the saying goes: ‘Not like mother, not like father, but like Roger the lodger.’

If you please your superior, then even if you don’t succeed in your studies and God has given you no talent, you will still do well and get ahead of everybody.

Don’t keep company with your schoolmates, they won’t teach you any good; but if you do, then keep company with the richer ones, on the chance that they may be useful to you. Do not regale or treat anyone, but rather behave in such a way that they treat you, and above all keep and save your kopeck: it is the most reliable thing in the world. A comrade or companion will cheat you and be the first to betray you in trouble; but a kopeck will never betray you, whatever trouble you get into. You can do everything and break through everything with a kopeck.

without gaining favor beforehand, as we all know, even the simplest document or certificate cannot be obtained; a bottle of Madeira must at least be poured down every gullet

But there are passions that it is not for man to choose. They are born with him at the moment of his birth into this world, and he is not granted the power to refuse them. They are guided by a higher destiny, and they have in them something eternally calling, never ceasing throughout one’s life.

Chichikov just smiled, jouncing slightly on his leather cushion, for he loved fast driving. And what Russian does not love fast driving? How can his soul, which yearns to get into a whirl, to carouse, to say sometimes: “Devil take it all!”—how can his soul not love it? Not love it when something ecstatically wondrous is felt in it?

He began to find myriads of faults in him, and came to hate him for having such a sugary expression when talking to a superior, and straightaway becoming all vinegar when addressing a subordinate.

Where is he who, in the native tongue of our Russian soul, could speak to us this all-powerful word: forward? who, knowing all the forces and qualities, and all the depths of our nature, could, by one magic gesture, point the Russian man towards a lofty life? With what words, with what love the grateful Russian man would repay him! But century follows century, half a million loafers, sluggards, and sloths lie in deep slumber, and rarely is a man born in Russia who is capable of uttering it, this all-powerful word.

Our Pavel Ivanovich showed an extraordinary flexibility in adapting to everything. He approved of the philosophical unhurriedness of his host, saying that it promised a hundred-year life. About solitude he expressed himself rather felicitously—namely, that it nursed great thoughts in a man. Having looked at the library and spoken with great praise of books in general, he observed that they save a man from idleness. In short, he let fall few words, but significant.

“Ah!” the colonel said with a smile, “there’s the benefit of paperwork! It will indeed take longer, but nothing will escape: every little detail will be in view.”

The commission for divers petitions existed only on a signboard. Its chairman, a former valet, had been transferred to the newly formed village construction committee. He had been replaced by the clerk Timoshka, who had been dispatched on an investigation—to sort things out between the drunken steward and the village headman, a crook and a cheat. No official anywhere.

“Now, what could be clearer? You have peasants, so you should foster them in their peasant way of life. What is this way of life? What is the peasant’s occupation? Ploughing? Then see to it that he’s a good ploughman. Clear? No, clever fellows turn up who say: ‘He should be taken out of this condition. The life he leads is too crude and simple: he must be made acquainted with the objects of luxury.’ They themselves, owing to this luxury, have become rags instead of people, and got infested with devil knows what diseases,

I say to the muzhik: ‘Whoever you work for, whether me, or yourself, or a neighbor, just work. If you’re active, I’ll be your first helper. You have no livestock, here’s a horse for you, here’s a cow, here’s a cart … Whatever you need, I’m ready to supply you with, only work. It kills me if your management is not well set up, and I see disorder and poverty there. I won’t suffer idleness. I am set over you so that you should work.’

“He who was born with thousands, who was brought up on thousands, will acquire no more: he already has his whims and whatnot! One ought to begin from the beginning, not from the middle. From below, one ought to begin from below. Only then do you get to know well the people and life amidst which you’ll have to make shift afterwards. Once you’ve suffered this or that on your own hide, and have learned that every kopeck is nailed down with a three-kopeck nail, and have gone through every torment, then you’ll grow so wise and well schooled that you won’t blunder or go amiss in any undertaking.

I often think, in fact: ‘Now, why is so much intelligence given to one head? Now, if only one little drop of it could get into my foolish pate, if only so that I could keep my house! I don’t know how to do anything, I can’t do anything!’ Ah, Pavel Ivanovich, take it into your care! Most of all I pity the poor muzhiks. I feel that I was never able to be …* what do you want me to do, I can’t be exacting and strict. And how could I get them accustomed to order if I myself am disorderly! I’d set them free right now, but the Russian man is somehow so arranged, he somehow can’t do without being prodded … He’ll just fall asleep, he’ll just get moldy.

We were educated, and how do we live? I went to the university and listened to lectures in all fields, yet not only did I not learn the art and order of living, but it seems I learned best the art of spending more money on various new refinements and comforts, and became better acquainted with the objects for which one needs money.

“One needs a supply of reasonableness,” said Chichikov, “one must consult one’s reasonableness every moment, conduct a friendly conversation with it.”

He still did not know that in Russia, in Moscow and other cities, there are such wizards to be found, whose life is an inexplicable riddle. He seems to have spent everything, is up to his ears in debt, has no resources anywhere, and the dinner that is being given promises to be the last; and the diners think that by the next day the host will be dragged off to prison. Ten years pass after that—the wizard is still holding out in the world, is up to his ears in debt more than ever, and still gives a dinner in the same way, and everybody thinks it will be the last, and everybody is sure that the next day the host will be dragged off to prison.

via English – alper.nl https://ift.tt/3a5ijN9

0 notes

Text

Socialism

William Morris

Monopoly; or, How Labour is Robbed

I want you to consider the position of the working-classes generally at the present day: not to dwell on the progress that they may (or may not) have made within the last five hundred or the last fifty years; but to consider what their position is, relatively to the other classes of which our society is composed: and in doing so I wish to guard against any exaggeration as to the advantages of the position of the upper and middle-classes on the one side, and the disadvantages of the working-classes on the other; for in truth there is no need for exaggeration; the contrast between the two positions is sufficiently startling when all admissions have been made that can be made. After all, one need not go further than the simple statement of these few words: The workers are in an inferior position to that of the non-workers.

When we come to consider that everyone admits nowadays that labour is the source of wealth - or, to put it in another way, that it is a law of nature for man generally, that he must labour in order to live - we must all of us come to the conclusion that this fact, that the workers' standard of livelihood is lower than that of the non-workers, is a startling fact. But startling as it is, it may perhaps help out the imaginations of some of us - at all events of the well-to-do, if I dwell a little on the details of this disgrace, and say plainly what it means.

To begin, then, with the foundation; the workers eat inferior food and are clad in inferior clothes to those of the non-workers. This is true of the whole class: but a great portion of it are so ill-fed that they not only live on coarser or nastier victuals than the non-producers, but have not enough, even of these, to duly keep up their vitality; so that they suffer from the diseases and the early death which come of semi-starvation: or why say semi-starvation? let us say plainly that most of the workers are starved to death. As to their clothing, they are so ill-clad that the dirt and foulness of their clothes forms an integral part of their substance, and is useful in making them a defence against the weather; according to the ancient proverb, "Dirt and grease are the poor man's apparel."

Again, the housing of the workers is proportionately much worse, so far as the better-off of them go, than their food or clothing. The best of their houses or apartments are not fit for human beings to live in, so crowded as they are, They would not be, even if one could step out of their doors into gardens or pleasant country, or handsome squares; but when one thinks of the wretched sordidness and closeness of the streets and alleys that they actually do form, one is almost forced to try to blunt one's sense of fitness and propriety, so miserable are they. As to the lodgings of the worse-off of our town workers, I must confess that I only know of them by rumour, and that I dare not face them personally; though I think my imagination will carry me a good way in picturing them to me. One thing, again, has always struck me much in passing through poor quarters of the town, and that is the noise and unrest of them, so confusing to all one's ideas and thoughts, and such a contrast to the dignified calm of the quarters of those who can afford such blessings.

Well! food, clothes, and housing - those are the three important items in the material conditions of men, and I say flatly that the contrast between those of the non-producers and those of the producers is horrible, and that the word is no exaggeration. But is there a contrast in nothing else - education, now? Some of us are in the habit of boasting about our elementary education: perhaps it is good so far as it goes (and perhaps it isn't), but why doesn't it go further? Why is it elementary? In ordinary parlance, elementary is contrasted with liberal education. You know that in the class to which I belong, the professional or parasitical class, if a man cannot make some pretence to read a Latin book, and doesn't know a little French or German, he is very apt to keep it dark as something to be ashamed of, unless he has some real turn towards mathematics of the physical sciences to cover his historical or classical ignorance; whereas if a working-man were to know a little Latin and a little French, he would be looked on as a very superior person, a kind of genius - which, considering the difficulties that surround him, he would be: inferiority again, you see, clear and plain.

But after all, it is not such scraps of ill-digested knowledge as this that give us the real test of the contrast; this lies rather in the taste for reading and the habit of it, and the capacity for the enjoyment of refined thought and the expression of it, which the more expensive class really has (in spite of the disgraceful sloppiness of its education), and which unhappily the working or un-expensive class lacks. The immediate reason for that lack, I know well enough, and that forms another item of contrast: it is the combined leisure and elbow-room which the expensive class considers its birthright, and without which, education, as I have often had to say, is a mere mockery; and which leisure and elbow-room the working class lacks, and even "social reformers" expect them to be contented with that lack. Of course, you understand that in speaking of this item I am thinking of the well-to-do artisan, and not the squalid, hustled-about, misery-blinded and hopeless wretch of the fringe of labour - i.e., the greater part of labour.

Just consider the contrast in the mere matter of holidays. Leisure again! If a professional man (like myself, for instance) does a little more than his due daily grind - dear me, the fuss his friends make of him! how they are always urging him not to overdo it, and to consider his precious health, and the necessity of rest and so forth! and you know the very same persons, if they found some artisan in their employment looking towards a holiday, how sourly they would treat his longings for rest, how they would call him (perhaps not to his face) sot and sluggard and the like; and if he has it, he has got to take it against both his purse and his conscience; whereas in the professional class the yearly holiday is part of the payment for services. Once more, look at the different standard for the worker and the non-worker!

What can I say about popular amusements that would not so offend you that you would refuse to listen to me? Well, I must say something at any cost - viz., that few things sadden me so much as the amusements which are thought good enough for the workers; such a miserable killing - yea, murder - of the little scraps of their scanty leisure time as they are. Though, indeed, if you say that there is not so much contrast here between the workers' public amusements and those provided for the middle classes, I must admit it, with this explanation, that owing to the nature of the case, the necessarily social or co-operative method of the getting up and acceptation of such amusements, the lower standard has pulled down the whole of our public amusements; has made, for instance, our theatrical entertainments the very lowest expression of the art of acting which the world has yet seen.

Or again, a cognate subject, the condition of the English language at present. How often I have it said to me, You must not write in a literary style if you wish the working classes to understand you. Now at first sight that seems as if the worker were in rather the better position in this matter; because the English of our drawing-rooms and leading articles is a wretched mongrel jargon that can scarcely be called English, or indeed language; and one would have expected, a priori, that what the workers needed from a man speaking to them was plain English: but alas! 'tis just the contrary. I am told on all hands that my language is too simple to be understood by working-men; that if I wish them to understand by working-men; that if I wish them to understand me I must use as inferior quality of the newspaper jargon, the language (so called) of critics and "superior persons"; and I am almost driven to believe this when I notice the kind of English used by candidates at election time, and by political men generally - though of course this is complicated by the fact that these gentlemen by no means want to make the meaning of their words too clear.

Well, I want to keep as sternly as possible to the point that I started from - viz., that there is a contrast between the position of the working-classes and that of the easily-living classes, and that the former are in an inferior position in all ways. And here, at least, we find the so-called friends of the working-classes telling us that the producers are in such a miserable condition that, if they are to understand our agitation, we must talk down to their slavish condition, not straightforwardly to them as friends and neighbours - as men, in short. Such advice I neither can nor will take; but that this should be thought necessary shows that, in spite of all hypocrisy, the master-class know well enough that those whom they "employ" are their slaves.

To be short, then, the working-classes are, relatively to the upper and middle-classes, in a degraded condition, and if their condition could be much raised from what it is now, even if their wages were doubled and their work-time halved, they would still be in a degraded condition, so long as they were in a position of inferiority to another class - so long as they were dependent on them - unless it turned out to be a law of nature that the making of useful things necessarily brought with it such inferiority!

Now, once again, I ask you very seriously to consider what that means, and you will, after consideration, see clearly that it must have to do with the way in which industry is organized amongst us, and the brute force which supports that organization. It is clearly no matter of race; the highest noble in the land is of the same blood, for all he can tell, as the clerk in his estate office, or his gardener's boy. The grandson or even the son of the "self-made man" may be just as refined - and also quite as unenergetic and stupid - as the man with twenty generations of titled fools at his back. Neither will it do to say, as some do, that it is a matter of individual talent or energy. He who says this, practically asserts that the whole of the working-classes are composed of men who individually do not rise above a lowish average, and that all of the middle-class men rise above it; and I don't think any one will be found who will support such a proposition, who is himself not manifestly below even that lowish average. No! you will, when you think of this contrast between the position of the producing and the non-producing classes, be forced to admit first that it is an evil, and secondly that it is caused by artificial regulations; by customs that can be turned into more reasonable paths; by laws of man that can be abolished, leaving us free to work and live as the laws of nature would have us. And when you have come to those two conclusions, you will then have either to accept Socialism as the basis for a new order of things, or to find some better basis than that; but you will not be able to accept the present basis of society unless you are prepared to say that you will not seek a remedy for an evil which you know can be remedied. Let me put the position once more as clearly as I can, and then let us see what the remedy is.

Society to-day is divided into classes, those who render services to the public and those who do not. Those who render services to the community are in an inferior position to those who do not, though there are various degrees of inferiority amongst them, from a position worse than that of a savage in a good climate to one not much below that of the lower degree of the unserviceable class; but the general rule is, that the more undeniably useful a man's services are, the worse his position is; as, for example, the agricultural labourers who raise our most absolute necessaries are the most poverty-stricken of all our slaves.

The individuals of this inferior or serviceable class, however, are not deprived of a hope. That hope is, that if they are successful they may become unserviceable; in which case they will be rewarded by a position of ease, comfort, and respect, and may leave this position as an inheritance to their children. The preachers of the unserviceable class (which rules all society) are very eloquent in urging the realization of this hope, as a pious duty, on the members of the serviceable class. They say, amidst various degrees of rigmarole: "My friends, thrift and industry are the greatest of the virtues; exercise them to the uttermost, and you will be rewarded by a position which will enable you to throw thrift and industry to the winds."

However, it is clear that this doctrine would not be preached by the unserviceable if it could be widely practised, because the result would then be that the serviceable class would tend to grow less and less and the world be undone; there would be nobody to make things. In short, I must say of this hope, "What is that among so many?" Still it is a phantom which has its uses - to the unserviceable.

Now this arrangement of society appears to me to be a mistake (since I don't want to use strong language) - so much a mistake, that even if it could be shown to be irremediable, I should still say that every honest man must needs be a rebel against it; that those only could be contented with it who were, on the one hand, dishonest tyrants interested in its continuance; or, on the other hand, the cowardly and helpless slaves of tyrants - and both contemptible. Such a world, if it cannot be mended, needs no hell to supplement it.

But, you see, all people really admit that it can be remedied; only some don't want it to be, because they live easily and thoughtlessly in it and by means of it; and others are so hard-worked and miserable that they have no time to think and no heart to hope, and yet I tell you that if there were nothing between these two sets of people it would be remedied: even then should we have a new world. But judge you with what wreck and ruin, what fire and blood, its birth would be accompanied!

Argument, and appeals to think about these matters, and consciously help to bring a better world to birth, must be addressed to those who lie between these two dreadful products of our system, the blind tyrant and his blind slave. I appeal, therefore, to those of the unserviceable class who are ashamed of their position, who are learning to understand the crime of living without producing, and would be serviceable if they could; and, on the other hand, to those of the serviceable class who by luck maybe, or rather maybe by determination, by sacrifice of what small leisure or pleasure our system has left them, are able to think about their position and are intelligently discontented with it.

To all these I say: You well know that there must be a remedy to the present state of things. For Nature bids all men to work in order to live, and that command can only be evaded by a man or a class forcing others to work for it in its stead; and, as a matter of fact, it is the few that compel and the many that are compelled; as indeed the most must work, or the work of the world couldn't go on. Here, then, is your remedy within sight surely; for why should the many allow the few to compel them to do what Nature does herself compel them to do? It is only by means of superstition and ignorance that they can do so; for observe that the existence of a superior class living on an inferior implies that there is a constant struggle going on between them; whatever the inferior class can do to better itself at the expense of the superior it both can and must do, just as a plant must needs grow towards the light; but its aim must be proportionate to its freedom from prejudice and its knowledge. If it is ignorant and prejudiced it will aim at some mere amelioration of its slavery; when it ceases to be ignorant, it will strive to throw off its slavery once for all.

Now, I may assume that the divine appointment of misery and degradation as accompaniments of labour is an exploded superstition among the workers; and, furthermore, that the recognition of the duty of the working-man to raise his class, apart from his own individual advancement, is spreading wider and wider amongst the workers. I assume that most workmen are conscious of the inferior position of their class, although they are not and cannot be fully conscious of the extent of the loss which they and the whole world suffer as a consequence, since they cannot see and feel the better life they have not lived. But before they set out to seek a remedy they must add to this knowledge of their position and discontent with it, a knowledge of the means whereby they are kept in that position in their own despite; and that knowledge it is for us Socialists to give them, and when they have learned it then the change will come.

One can surely imagine the workman saying to himself, "Here am I, a useful person in the community, a carpenter, a smith, a compositor, a weaver, a miner, a ploughman, or what not, and yet, as long as I work thus and am useful, I belong to the lower class, and am not respected like yonder squire or lord's son who does nothing, yonder gentleman who receives his quarterly dividends, yonder lawyer or soldier who does worse than nothing, or yonder manufacturer, as he calls himself, who pays his managers and foremen to do the work he pretends to do; and in all ways I live worse than he does, and yet I do and he lives on my doings. And furthermore, I know that not only do I know my share of my work, but I know that if I were to combine with my fellow-workmen, we between us could carry on our business and earn a good livelihood by it without the help (?) of the squire's partridge-shooting, the gentleman's dividend-drawing, the lawyer's chicanery, the soldier's stupidity, or the manufacturer's quarrel with his brother manufacturer. Why, then, am I in an inferior position to the man who does nothing useful, and whom, therefore, it is clear that I keep? He says he is useful to me, but I know I am useful to him or he would not `employ' me, and I don't perceive his utility. How would it be if I were to leave him severely alone to try the experiment of living on his usefulness, while I lived on mine and worked with those that are useful for those that are useful? Why can't I do this?"

My friend, because since you live by your labour, you are not free. And if you ask, Who is my master? who owns me? I answer Monopoly. Get rid of Monopoly, and you will have overthrown your present tyrant, and will be able to live as you please, within the limits which Nature prescribed to you while she was your master, but which limits you, as man, have enlarged so enormously by almost making her your servant.

And now, what are we to understand by the word Monopoly. I have seen it defined as the selling of wares at an enhanced price without the seller having added any additional value to them; which may be put again in this way, the habit of receiving reward for services never performed or intended to be performed - for imaginary services, in short.

This definition would come to this, that Monopolist is cheat writ large; but there is an element lacking in this definition which we must presently supply. We can defend ourselves against this cheat by using our wits to find out that his services are imaginary, and then refusing to deal with him; his instrument is fraud only. I should extend the definition of the Monopolist by saying that he was one who was privileged to compel us to pay for imaginary services. He is, therefore, a more injurious person than a mere cheat, against whom we can take precautions, because his instrument for depriving us of what we have earned is no longer mere fraud, but fraud with violence to fall back on. So long as his privilege lasts we have no defence against him; if we want to do business in his line of things, we must pay him the toll which his privilege allows him to claim of us, or else abstain from the article we want to buy. If, for example, there were a Monopoly of champagne, silk velvet, kid gloves, or dolls' eyes, when you wanted any of those articles you would have to pay the toll of the Monopolist, which would certainly be as much as he could get, besides their cost of production and distribution; and I imagine that if any such Monopoly were to come to light in these days, there would be a tremendous to-do about it, both in and out of Parliament. Nevertheless, there is little to-do about the fact that all society to-day is in the grasp of Monopoly. Monopoly is our master, and we do not know it.

For the privilege of our Monopolists does not enable them merely to lay a toll on a few matters of luxury or curiosity which people can do without. I have stated, and you must admit, that everyone must labour who would live, unless he is able to get somebody to do his share of labour for him - to be somebody's pensioner in fact. But most people cannot be the pensioners of others; therefore, they have to labour to supply their wants; but in order to labour usefully two matters are required: 1st, The bodily and mental powers of a human being, developed by training, habit and tradition; and 2nd, Raw material on which to exercise those powers, and tools wherewith to aid them. The second matters are absolutely necessary to the first; unless the two come together, no commodity can be produced. Those, therefore, that must labour in order to live, and who have to ask leave of others for the use of the instruments of labour, are not free men but the dependents of others, i.e., their slaves; for, the commodity which they have to buy of the monopolists is no less than life itself.

Now, I ask you to conceive of a society in which all sound and sane persons can produce by their labour on raw materials, aided by fitting tools, a due and comfortable livelihood, and which possesses a sufficiency of raw material and tools. Would you think it unreasonable or unjust, that such [a] community should insist on every sane and sound person working to produce wealth, in order that he might not burden the community; or, on the other hand, that it should insure a comfortable livelihood to every person who worked honestly for that livelihood, a livelihood in which nothing was lacking that was necessary to his development as a healthy human animal, with all its strange complexity of intellectual and moral habits and aspirations?

Now, further, as to the raw material and tools of the community, which, mind you, are necessary to its existence: would you think it unreasonable, if the community should insist that these precious necessaries, things without which it could not live, should be used and not abused? Now, raw material and tools can only be used for the production of useful things; a piece of tillage, for instance, is not used by sowing it with thistles and dock and dodder, nor a bale of wool by burning it under your neighbour's window to annoy him; this is abuse, not use, of all these things, and I say that our community will be right in forbidding such abuse.