#isambard prince

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A Fine Engraved Nautilus Shell Decorated with the Royal Armourial and Feathers of Albert, Prince of Wales and with Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s Ship’s ‘The SS Great Britain’ and ‘The SS Great Western’ Giving their specifications and detailing their launching. ‘Engraved with a common penknife by C.H Wood who had the distinguished honour of presenting one similar to Her Most Gracious Majesty Queen Victoria, Jun. 1845’ (small chip with a hairline fissure to one edge) Circa June 1845

finch-and-co

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Benjamin Franklin

The jetsons

Yogi bear

Boxtrolls

Nightmare before Christmas

A land before time

Octodad

katamari prince

Madagascar

Robot devil

Disenchanted

Shadow wizard money gang

Sack boy

Sam and max

Hagrid

Robin Hood

Alvin and the chipmunks

Twitter bird

Triangle factory guy

In the night garden

Octonauts

Baby Jake

Ghost cod

Plato

Isaac newton

The twits

Digdug

Q!bert

Wreck it Ralph

Bfg

Charlie and the choclate factory

Queen Elizabeth the second

Queen Victoria

King Henry VIII

Edmund mcmillen

More Isaac characters, azezeal, cain

More bible characters, beelzebub, cain.

Mary magdelane

Mary (ghosts)

Boudicca

Pride flags

Countries

Vladimir putin

Teddy roosevelt

Kamala Harris

GIMP mascot

Spy x family more

Concepts (music, language, etc)

Fargos mutant mod characters

Hatsune miku

Miku binder Jefferson

Richard ayoade

Peanut butter jelly time banana

Snoop dog

Big brother (1984)

Animal farm characters

Einstein

Midas

Pot of greed

Super greed

More bible characters (Lilith)

Barney

Rev love joy

Kirk van houten

Duffman

Julius hibbert

More hunger games (trainer, sister, villain)

Buccarati

Guido mista

The noid

Ham burgaler

Grimace

Clippy

Kabru (dungeon meshi guy)

The seven deadly sins

Huma kavula

Police officer

Eddie and lou

Cleveland

The UK

French person

Bobo buddy

Van Gogh

The Mona Lisa

Eli (half life)

Barney (half life)

Chase

Rubble

The DM

the other 2 gorgons

Hermes

Achilles

Arachne (spider lady who crossed Athena)

Athena

Aphrodite

Apoim(Pokémon)

Dawn

Lord krump

Olivia

Bobbery

Wolf man

Frankenstein

Frankensteins monster

The creature from the black lagoon

Ed Sheeran

Big Ben

Totoro

Arrietty

Ponyo

No face

Howl

Calficer

Kiki

Witch of the wastes

Porco Rosso

Han Solo

Jack sparrow

Peter Pan

Wendy

Captain Hook

Lego joker

Lego Batman

Alfred

The riddler

Beavis

Butthead

Dorothy

Scarecrow

Cowardly lion

Tin man

The wicked witch of the west

The wizard of oz

Rocky

Barbie

Ken

Tarzan

Jane

George of the jungle

Wally (where’s wally)

Kermit

Fozzie

Animal

Miss piggy

Scooter

Gonzo

Rowlf the dog

rizzo the rat

Pepe

Dr Bunsen honeydew

Beaker

statler and waldorf

Swedish chef

Sam eagle

Sweetums

Walter

Camilla the chicken

Elmo

Big bird

Count countula

Oscar the grump

Professor squackencluck

jeopardy mouse

Count duckula

Nero

Dawn crumhorn

Isambard King Kong Brunel

Quark

Pandaminion

Stanley

The narrator

Micheal Myers

Jason voorhees

Jack the Ripper

The muffin man

The gingerbread man

The runaway pancake

Sweeney Todd

Burke and hare

Mad hatter

Alice

Tweedle dum and tweedle Dee

Cheshire Cat

Queen of hearts

March hare

Generic cowboy

Billy the kid

The lizard cowboy movie rango

Dust papyrus

Red dead redemption guy

Zombie

Cotl angel guy

Ratau

A Crumpet

Caesar

Nero (Roman emperor)

Brutus

Shakespeare

Dr. House

Billy Joel

Ziggy stardust

Major Tom

Lord snooty

Bash street kids

Paddington

Rabbit (whinnie the Pooh)

Heffalump (Winnie the Pooh)

Elvis Presley

Hong Kong phoeey

Dick dastardly

Inspector gadget

Lady Gaga

Labyrinth

Davy Crockett

John Lennon

Superpets the hamster thing

Malcolm X

Martin Luther king

Jamie Oliver

Moomins

Pied piper

Little red riding hood

Bjorn (peggle)

Erina

Gary charmers

Catgirl

Mary(had a little lamb)

Nimona

The tortoise and the hare

Charlie (bit my finger)

Shy guy

Booster

Teddy bear

Dracula

Shaun the sheep

Timmy time!

Megamind

Kung fu panda

Tangled

Alan turing

Charles Babbage

Picasso

Jan misali

princess Diana

Walt Disney

Steven after not surviving

David Attenborough

James cordon

More lego movie

More toys

Jack in the box

Star signs (Virgo etc)

Apollo

Emojis

Donkey Kong jr

Psycho cannibal guy

Flork of cows mr rich

Petaly

Mike

Pearl

Mrs puff

Pain girl

Ramshackle

Nigel and marmalade

The one with the three eyed guy

Gloink king

Pikit

Gooseworx bounty hunter girl and that series in general

Goncharov

Destiel

Hamlet

Ood

Mars rover

Elon musk

Buzz aldrin

Neil Armstrong

Danny devito

Rory pond

Gummy bear

Smaug

Bard the bowman

Beorn

Big hero six

King of the hill

moral Orel

Rocky horror picture show

Death note

Starman earthbound

More Star Wars

Leia

Droids

Jabba the Hutt

Boba fett

Baby yoda

Palpatine

Lotr orc

Beaty and the beast

Douglas adams

Jimminy cricket

Winston Churchill

Even older Joseph

Duolingo bird

Pinky and the brain

Orson wells

KEKW guy

Animaniacs

Captain caveman

Risk of rain

Steve Harley

Chess peices

Rosa parks

Super paper Mario

Newer paper Mario partners

Koopalings

Red dwarf

Ghengis khan

Matt groening

Pandora

Sontaran

The silence

More futurama- Sal, old lady, roberto, bird lawyer, cops,

Crash bandicoot villains and girl

Monsier bloque Mario and Luigi

Oddish

Gary

Arceus

Wonder over yonder

The office

More roald dahl characters

Roald Dahl

Mariah Carey

Hansel and gretel

The three little pigs

Star Trek

Monster prom

All the doctors

The man who sold the world

Professor oak

More ut yellow

Harambe

David tennant

1 note

·

View note

Photo

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

SPOILERS BOOK 4

I have a list of headcanons about Fox and Jacob’s family:

Joie is the eldest, then come James and Eddie

Joie is her father’s daughter in everything BUT dancing. She’s the worst dancer that ever existed, unless somebody guides her right…

Jaime (but they’ll have to stop calling him that when he’ll get older, he’a bound to be taller than Jacob) is the second-born and he is just a little bit less reckless than Joie, more emphatetic and the best dancer in the family (even better than Fox). He’ll grow to be a heartbreaker as his father was when he was young (but who knows when the right girl will come…). He’s a year and a half younger than Joie.

Eddie is the youngest, he, as James, resembles his father physically, but has his mother’s character and is the calmest and most rational in the family. He’a the little one, seven years younger than Joie, and he hates how everyone feels like he is to protect all the time. Let’s say he’s desperately trying to be not as harmless as he seems.

All three of them grew up to their parents stories (there’s only one story they’ll never get told spontaneously, and it involves some immortals, a crossbow and a reward in Lothraine for their uncle’s head) and learnt to fight (not really because Fox and Jacob wanted to but… Joie seems born to play with daggers, swords are Jamie’s second arms and little Eddie has an aim that everybody should fear)

In addition, their favourite uncle (but don’t tell the others) is the first regal guard for Kami’en and the trainer of the Goyl’s guard. He’s difficult to win over, but only because sometimes he becames made of jade.

Nerron and Will will have Joie as their ring-bearer for their marriage (Will wanted an human and a goyl’s ceremony, so who was Nerron to interfere).

For all three of them the day in which they’ll defeat Nerron in combat will be the day of their aldulthood beginning.

They’ll be very very much loved by Aunt Alma, Granpa (or Grumpypa) Albert and Uncle Sylvain. They’ll meet their mother side of the family, but it will be a little more complicated than that. And they’ll only discover the story of a certain Isambard Brunel in a moment of rage and distraction of their father. Afterwards which everybody will cry a lot.

Everybody will be jealous of Joie first boyfriend and when they’ll break up he’ll risk his life from three stupidly possessive Reckless (but in reality nobody will hurt him. Because Joie would be at their throats.

All three of them will be shapeshifters. The first and easiest to transform will be Joie, and Jaime will be the one who finds it more difficult.

One day they will visit Vena, because of some important issue with some glass (?), they only know what they overheard their parents saying. There Joie will meet a prince made of stone who is the only one able to win over her in duel and Jaime will meet for the first time the daughter of a spy his parents seem to know really well. Eddie would be too little for this kind of drama, but he too will discover new things and finally make friend who aren’t already awed by his parents or his siblings. But most importantly, all three of them will cause mayhem with the royal guards and embrass all the trainees.

#I have a lot more ready if you want them#mirrorworld#jacob reckless#reckless#reckless series#fox#joie reckless

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Name[edit]

The top hat is also known as a beaver hat or silk hat, in reference to its material, as well as casually as chimney pot hat or stove pipe hat.

History[edit]

Self portrait (c:a 1770) of Peter Falconet (1741–1791). One of the earliest depicted prototypes of what became the top hat. In early prototypes, a sash around the crown was closed by a buckle. This was later dropped, in the same way as shoe buckles for male pumps were replaced by bowties around the turn of the 19th century.

Carle Vernet's 1796 painting showing two decadent French "Incredibles" greeting each other, one with what appears to be a top hat

According to fashion historians, the top hat may have descended directly from the sugarloaf hat;[2] otherwise it is difficult to establish provenance for its creation.[3] Gentlemen began to replace the tricorne with the top hat at the end of the 18th century; a painting by Charles Vernet of 1796, Un Incroyable, shows a French dandy (one of the Incroyables et Merveilleuses) with such a hat.[4] The first silk top hat in England is credited to George Dunnage, a hatter from Middlesex, in 1793.[5] The invention of the top hat is often erroneously credited to a haberdasher named John Hetherington.

Within 30 years top hats had become popular with all social classes, with even workmen wearing them. At that time those worn by members of the upper classes were usually made of felted beaver fur; the generic name "stuff hat" was applied to hats made from various non-fur felts. The hats became part of the uniforms worn by policemen and postmen (to give them the appearance of authority); since these people spent most of their time outdoors, their hats were topped with black oilcloth.[6]

19th century[edit]

Between the latter part of 18th century and the early part of the 19th century, felted beaver fur was slowly replaced by silk "hatter's plush", though the silk topper met with resistance from those who preferred the beaver hat.

The 1840s and the 1850s saw it reach its most extreme form, with ever-higher crowns and narrow brims. The stovepipe hat was a variety with mostly straight sides, while one with slightly convex sides was called the "chimney pot".[7] The style most commonly referred to as the stovepipe was popularized in the United States by Abraham Lincoln during his presidency; though it is postulated[by whom?] that he may never have called it stovepipe himself, but merely a silk hat or a plug hat. Lincoln often carried documents and letters inside the hat.[8] One of Lincoln's top hats is kept on display at the National Museum of American History in Washington, DC.[9]

Isambard Kingdom Brunel, William Harrison, John Scott Russell and others at the launching of the SS Great Eastern, London 1857

Abraham Lincoln (middle) in his distinctive "stovepipe" silk hat at Antietam, 1862

In this popular print of the 1848 "Five Days of Milan", the Italian city's uprising against Austrian rule, several combatants are shown wearing top hats.

During the 19th century, the top hat developed from a fashion into a symbol of urban respectability, and this was assured when Prince Albert started wearing them in 1850; the rise in popularity of the silk plush top hat possibly led to a decline in beaver hats, sharply reducing the size of the beaver trapping industry in North America, though it is also postulated[by whom?] that the beaver numbers were also reducing at the same time. Whether it directly affected or was coincidental to the decline of the beaver trade is debatable.

James Laver once observed that an assemblage of "toppers" resembled factory chimneys and thus added to the mood of the industrial era. In England, post-Brummel dandies went in for flared crowns and swooping brims. Their counterparts in France, known as the "Incroyables", wore top hats of such outlandish dimensions that there was no room for them in overcrowded cloakrooms until the invention of the collapsible top hat.[10][11]

20th century[edit]

Until World War I the top hat was maintained as a standard item of formal outdoor wear by upper-class males for both daytime and evening usage. Considerations of convenience and expense meant however that it was increasingly superseded by soft hats for ordinary wear. By the end of World War II, it had become a comparative rarity, though it continued to be worn regularly in certain roles. In Britain these included holders of various positions in the Bank of England and City stockbroking, and boys at some public schools. All the civilian members of the Japanese delegation that signed the Japanese Instrument of Surrender on 2 September 1945, wore top hats, reflecting common diplomatic practice at the time.[12]

The top hat persisted in politics and international diplomacy for many years. In the Soviet Union, there was debate as to whether its diplomats should follow the international conventions and wear a top hat. Instead a diplomatic uniform with peaked cap for formal occasions was adopted. Top hats were part of formal wear for U.S. presidential inaugurations for many years. President Dwight D. Eisenhower spurned the hat for his inauguration, but John F. Kennedy, who was accustomed to formal dress, brought it back for his in 1961. Nevertheless, Kennedy delivered his forceful inaugural address hatless, reinforcing the image of vigor he desired to project, and setting the tone for an active administration to follow.

His successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, did not wear a top hat for any part of his inauguration in 1965, and the hat has not been worn since for this purpose.[13]

In the United Kingdom, the post of Government Broker in the London Stock Exchange that required the wearing of a top hat in the streets of the City of London was abolished by the "Big Bang" reforms of October 1986.[14] In the British House of Commons, a rule requiring a Member of Parliament who wished to raise a point of order during a division, having to speak seated with a top hat on, was abolished in 1998. Spare top hats were kept in the chamber in case they were needed. The Modernisation Select Committee commented that "This particular practice has almost certainly brought the House into greater ridicule than almost any other".[15]

Although Eton College has long abandoned the top hat as part of its uniform, top hats are still worn by "Monitors" at Harrow School with their Sunday dress uniform.[16] They are worn by male members of the British Royal Family on State occasions as an alternative to military uniform, for instance, in the Carriage Procession at the Diamond Jubilee in 2012.[17] Top hats may also be worn at some horse racing meetings, notably The Derby[18] and Royal Ascot.[19] Top hats are worn at the Tynwald Day ceremony and a few other formal occasions in the Isle of Man.

In George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty Four, the top hat features prominently in the propaganda of the book's totalitarian regime: "These rich men were called capitalists. They were fat, ugly men with wicked faces [...] dressed in a long black coat which was called a frock coat, and a queer, shiny hat shaped like a stovepipe, which was called a top hat. This was the uniform of the capitalists, and no one else was allowed to wear it."[20]

Winston Churchill in a frock coat with grey top hat.

The inauguration of John F. Kennedy as seen from behind. Most men have their hats off; however a few top hats can be distinguished, some by the shininess of the hat's flat crown

Edward Beckett, 5th Baron Grimthorpe and others at Royal Ascot, 2012

21st century[edit]

The modern standard top hat is a hard, black silk hat, characteristically made of fur. The acceptable colors are much as they have traditionally been, with "white" hats (which are actually grey), a daytime racing color, worn at the less formal occasions demanding a top hat, such as Royal Ascot, or with a morning suit. In the U.S. top hats are worn widely in coaching, a driven horse discipline, as well as for formal riding to hounds.

The collapsible silk opera hat, or crush hat, is still worn on occasions, and black in color if worn with evening wear as part of white tie,[21] and is still made by a few companies, of the traditional materials of satin or grosgrain silk. The other alternative hat for eveningwear is the normal hard shell.[22]

In formal academic dress, the Finnish and Swedish doctoral hat is a variant of the top hat, and remains in use today.

American rock musician Tom Petty was known for wearing several types of top hats throughout his career and in his music videos such as "Don't Come Around Here No More". The British-American musician Slash has sported a top hat since he was in Guns N' Roses, a look that has become iconic for him.[23] Panic! at the Disco's Brendon Urie is also a frequent wearer of top hats. He has been known to wear them in previous live performances on their Nothing Rhymes with Circus tour and in the music videos, "The Ballad of Mona Lisa" and "I Write Sins Not Tragedies".

*How interesting!*

*Thank you very much.*

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

4th May 1859 - The opening of the Cornwall Railway between Plymouth in Devon and Falmouth, Cornwall, crossing the River Tamar using The Royal Albert Bridge... designed by Brunel and opened by Prince Albert two days earlier. The whole of the line is still in use today and is partly used by the London to Penzance service.

The Cornwall Railway was a 7 ft 1⁄4 in (2,140 mm) broad gauge railway, The final plans, design and construction were overseen by Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

An early proposal was that trains would be propelled by an atmospheric system. An airtight tube would be laid between the rails and a wagon with a piston running in the tube led the train. Stationary steam engines would pump air from the tube and the train would be drawn by the resulting vacuum. With the steep gradients, engineers calculated that this system would improve fuel efficiency by 20% and, it would have the added benefit that it would be impossible for trains to have a head on collision. This system had been used successfully on a short section of the Dublin and Kingstown Railway but, with less success on the London and Croydon Railway. This innovation was rejected by Parliament on safety grounds.

The Cornwall Railway became part of the Great Western Railway in 1899 and, the line was converted to standard gauge in 1892. Sixty six miles of track was changed from broad gauge to standard gauge in just one weekend!

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

@isambard-prince

𝙰 𝙻𝚒𝚝𝚎𝚛𝚊𝚝𝚎 𝙿𝚊𝚜𝚜𝚒𝚘𝚗: 𝙻𝚎𝚝𝚝𝚎𝚛𝚜 𝚘𝚏 𝙰𝚗𝚊𝚒̈𝚜 𝙽𝚒𝚗 & 𝙷𝚎𝚗𝚛𝚢 𝙼𝚒𝚕𝚕𝚎𝚛: 𝟷𝟿𝟹𝟸–𝟷𝟿𝟻𝟹

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

LEXX Short Fanvids

Fandoms: Lexx

No Archive Warnings Apply

Kai (Lexx)

Stanley H. Tweedle

Xev | Zev Bellringer

790 (Lexx)

Isambard Prince

Fanvids

Crackvids

AI

Short form Lexx edits.

Ch1: 790 Will Always Love You Ch2: Prince Gives You Hell

(Feed generated with FetchRSS) source https://archiveofourown.org/works/45971023

0 notes

Text

Watch "Karliene - Become The Beast [LYRICS] - A Hannibal Fan Song #SaveHannibal" on YouTube

youtube

@isambard-prince

0 notes

Text

Dalkey and Environs

If you follow the swerve of shore south of Dublin city, you eventually wind up in Dalkey village, a small heritage town known largely for its three small castles and pretty main street, but also for its artisan shops, independent cafés, and popular pubs.

A sleepy suburb, the area is occasionally referred to as “the Beverley Hills of Dublin,” because of the number of celebrities living in the area — Bono! — Van Morrison! — or as “Ireland’s Bay of Naples,” because of the spectacular views, particularly from the top of nearby Killiney Hill. The village itself isn’t far from the border with Wicklow, a county known as “the Garden of Ireland.”

The town is heavily associated with writers. George Bernard Shaw was born in Torca Cottage; James Joyce taught in Clifton School, on Dalkey Avenue, and stayed in the nearby Martello Tower in Sandycove; Brendan Behan learned to mix explosives (chlorate of potash with paraffin wax and gelignite) in an IRA safe-house up the hill, now Fitzpatrick Castle. (In the 1950s, ownership of the Castle went to Seán Russell, then-IRA Chief-of-Staff. This is the same Seán Russell who died aboard a Nazi U-Boat in 1940.)

Hugh Leonard, known locally as Jack, was born in Dalkey; as was Maeve Binchy. The local pubs were once a playground for Samuel Beckett, and Flann O’Brien, who published The Dalkey Archive in 1964 — the story of a quirky scientist by the name of de Selby. Howard Marks, the famous drug-dealer (and author) hid out here in the 1970s, with crazy Jim McCann – another IRA connection. Salman Rushdie spent part of his decade in hiding, from the long reach of the Ayatollah Khomeini, living with Bono. Robert Fisk, the most eminent journalist of the Middle East, has had a home in the area for a number of years.

In fact, the history of writing in the village goes way back. In the late 18th century, a bunch of young wits and poets came together to take the absolute piss out of everything they could set their sights upon. They crowned a man named Stephen Armitage, who styled himself King of Dalkey, Emperor of the Muglins, Prince of the Holy Island of Magee, Baron of Bulloch, Seigneur of Sandycove, Defender of the Faith and Respector of All Others, Elector of Lambay and Ireland’s Eye, and Sovereign of the Most Illustrious Order of the Lobster and Periwinkle.

Thomas Moore, “the Bard of Ireland,” and author of the Minstrel Boy, among much else, was a willing subject of this petty kingdom. Moore’s friend, the poet Henrietta Battier, wrote a number of odes, including the line: “Hail, happy Dalkey! queen of isles, Where justice reigns in freedom’s smiles.” Then came the ’98 Rebellion. The Government moved to quell any expression of dissent. Thankfully, the tradition has been restored in our time: the sacristan of the local church, Fionn Gilmartin, currently occupies this exalted throne.

So august a reputation has Dalkey for all things literary, the inaugural Dalkey Book Festival was organised by the economist David McWilliams in 2010, and has since attracted hundreds of writers, including Seamus Heaney, John Banville, and Amos Oz. I saw Salman Rushdie speaking in St. Patrick’s Church in 2014.

The pubs and restaurants are also second-to-none. Finnegan’s is the best-known: great for a pint of Guinness. Try King’s Inn for the banter, the Magpie for craft beer, DeVille’s for steak, Queen’s for the beer garden, Benitos for the service, McDonagh’s for live music and pool, and the Vico for shots before hitting town against your better judgement. Further up the hill you have the aforementioned Fitzpatrick Castle Hotel, and the Druid’s Chair, a gem of a little spot.

Close to Dalkey, along the coast back towards Dublin, you’ll find Dun Laoghaire. It’s got three sailing clubs, two piers, and one impressive library. You can walk along the promenade, the piers, or go for a swim on Sandycove beach, or in the 40 Foot bathing-place. Make sure you get yourself a 99 from Teddy’s, the ice-cream is famous all over Ireland. There’s also one or two decent pubs, particularly the Whiskey Fair and Gilbert & Wright’s. Like it or loath it, Wetherspoons have taken over the 40 Foot pub, which means cheap booze.

The Martello Tower, now the James Joyce Museum, was once rented by the writer (and doctor) Oliver St. John Gogarty. Joyce, having stayed with his friend for six nights in 1904, eventually used the experience in the opening pages of his masterpiece, Ulysses.

Dun Laoghaire was once known as Kingstown, so-named in 1821 after the visit of boozy King George IV, the first reigning monarch to visit Ireland since the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. In Howth, just north of Dublin, the king disembarked from his yacht on his birthday, already “in high spirits,” meaning inebriated, and you can still see his tiny footprints, preserved for all eternity. He departed from Dun Laoghaire eighteen days later. In fact, a nearby memorial marks this auspicious stop-over. William Mackepeace Thackeray, the famous English novelist, described it as a “hideous obelisk, stuck upon four fat balls.” That’s a fairly good description.

The best way to get to Dalkey and Dun Laoghaire is to use the DART (Dublin Area Rapid Transit), though there’s nothing “rapid” about it. Actually, the train journey from Dublin to Dun Laoghaire is the oldest in Ireland, built in 1834. It was used by Thackeray in 1842, Carlysle in 1849, and Dickens in 1867. In 1882, having arrived by boat into Dun Laoghaire, Lord Cavendish, the newly-appointed Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, took this train into the city on his first day on the job, only to be murdered that evening in the Phoenix Park. The park is somewhat safer these days.

The train was slowly extended around the rest of the coast over the coming years. There are stunning views of the sea between Dalkey and Greystones, where the track tunnels through solid rock and clings to precarious sea cliffs. It was designed by famous engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inga, background text for convenience. Constant work in progress gfdi

Embraced in 1991.

____

When you ask Inga about her time leading up to her embrace she’ll tell you that it was formative and enlighting times. She’ll tell you that before the embrace she lived behind a veil of misconceptions and lack of focus, in a blurr of nothings, unaware of what living really was. You’ll be asked if you ever really have fought to survive. If you ever experienced how your soul drops down heavy in your stomach while you balance on the edge of death.

Survival hid behind smiling teeth, and survive she did. Her sire, a person of long stature and equally pale hair, tends to put people at unease with his/hers mere energy. It’s not uncommon of those in their clan, and her sire was no exception. A person blessed with an academic language and a longing for the bigger picture. The sire claimed metaphysical importance in every choice and action they did, but as with all great persons destined for greater things there was loneliness. Misunderstanding. Riddicule. Inga wasn't the first child and she never met any of the previous (as far as she was aware anyhow.. ). Some say that practise makes perfect, but that would incline that the previous childers weren't adequate and that the sire wasn't infallable. She quickly learned not to pry unless the answer to such prying was worth confusion and horror.

She prefers not to linger on the topic of her incarceration before - and after - the embrace, and will hastily change the topic by complimenting something on your person and continue to applaud your feats.

To find company and community was never an issue: her "optimistic outlook" and "positive personality" was most often received gratefully or as a fresh wind in a community otherwise drenched in Poe- and Lestat-stereotypes. There were no visible indications of harm och madness in her, and as a relatively fresh kindred she still hadn't lost the valuable rythm of the living.

Upon being released as a neonate she quickly traveled back to Gothenburg to fulfill the dream and hope of reuniting with her family. Whether she reunited with her family or not she wouldn't tell, but the following nights she would over and over again repeat how happy she was for her family while bloody tears streaked her cheeks.

After spending some time in Gothenburg (mayhaps a longer time than expected, thanks to Freja and clan Malkavian) she returned to London. She left Gothenburg to avoid Masquerade-violations, and returned to London in order to aid her sire.

As for the eternity and the future she doesn't keep long, structured plans. She will sometimes explain that life and reality will have its way despite your best or worst efforts, and the choices that you do get is your chance to make a right or a wrong choice. If you end up with a different book than you hoped for, you can either read it and learn something new, or throw it away and not have a book at all. If you can get two flowers or one flower, you can choose to have two flowers or one. If you find yourself in mortal danger you can choose to do what you need to survive, or you can panic and die. It's all about the oppurtunities and where you find them, she'll tell you with an encouraging smile. And while she herself seems to not actively seek out oppurtunities with the same intensity she encourages others to, she does have some structure. There were no outside reasons to seek out Vincent and Isambard, but she knew to not go against the 'hunches' and ended up enjoying the company and cooperation far more than she had expected. The initial few collaborations as a coterie turned out well, and the up and coming PI group they later became gave her a structure and a context she didn't know she needed. To call other kindred "friends" was a concept she knew to be complex, and to find that the shared experiences and workhours with Isambard and Vincent built a stability among them came as a happy surprise. Texting them about an upcoming job and puzzle clues in their company would sometimes provide her spirit with shelter, a sudden peace to her inner, constantly moving, split structure. Perhaps more importantly, the work with the odd couple of talents gave her a purpose. It would turn out only a few years past her embrace that while her sire had seen purpose in her being, it didn't mean that he would have her as more than a childer and a servant until the day when it was time to put her into action again. Her sire was infallible and important, so when they turned to other, more pressing things, Inga was left to find her self a home and a context to keep her alive.

She never referred to her self as "one the troubled and tortured" of her clan. In fact, often when she spent time with other Malkavians she would feel like a poser, maybe even feel a bit guilty. It didn't demand much to sift through prejudices and actual experience to see the patterns of the clan for what they were, and upon getting to know the clan she was grateful that her sire and her self were - as her sire once satirically put it - "fairly normal", neither of them very good at keeping their pride nor blindspots in check. Despite the pride and occasional pitfalls she found her refuge and healing balm in a person, first then realizing what peace and calm really was. With Raquan all else fell quiet and she could hear her spirit breathe for the first time in many years. She loved him and he said that he loved her, but his body was human and fragile, so she took it upon her self to help his soul to immortality. Boons were called in, debts created and with the prince's permission she watched Raquan consume his last meal. When asked she wont describe the horror of watching Raquan die beside her instead of coming back to life as a kindred. She wont tell you of the panic, of the arguments with her sire and her following attempts at embracing in a desperate attempt to find fault with her sire and their instructions. She wont let you hear of the anguish when she was forced to understand that it had to be a fault with her, with her blood, and that she was the reason that Raquan and several others had passed away. And she wont tell you about her sire's reaction upon learning that she was defect. What she will tell you is that things probably don't happen for specific reasons but there are always choices. How you view your life and your choices defines you, and as long as you keep an open mind and stay happy then all will be well.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Construction of New Balmoral: The growing family of Victoria and Albert, the need for additional staff, and the quarters required for visiting friends and official visitors such as cabinet members, however, meant that extension of the existing structure would not be sufficient and that a larger house needed to be built. In early 1852, this was commissioned from William Smith. The son of John Smith (who designed the 1830 alterations of the original castle), William Smith was city architect of Aberdeen from 1852. William Smith's designs were amended by Prince Albert, who took a close interest in details such as turrets and windows.

Construction began during summer 1853 (first and second photos,) on a site some 100 yards (91 m) northwest of the original building that was considered to have a better vista. Another reason for consideration was, that whilst construction was ongoing, the family would still be able to use the old house. Queen Victoria laid the foundation stone on 28 September 1853, during her annual autumn visit. By the autumn of 1855, the royal apartments were ready for occupancy, although the tower was still under construction and the servants had to be lodged in the old house. By coincidence, shortly after their arrival at the estate that autumn, news circulated about the fall of Sevastopol, ending the Crimean War, resulting in wild celebrations by royalty and locals alike. While visiting the estate shortly thereafter, Prince Frederick of Prussia asked for the hand of Princess Victoria.

The new house was completed in 1856, and the old castle subsequently was demolished. By autumn 1857, a new bridge across the Dee, designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel linking Crathie and Balmoral was finished. (third and fourth photos)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Culture of Bristol

Bristol is a favourite tourist destination as well as has practically everything that a tourist would certainly desire. Its centers are modern, its night life is throbbing as well as its arts and media venues are miles ahead of even its most advanced neighbours. The citizens are quick to explain that their city needs to have beat Liverpool in the choice of the 2008 European City of Culture. The only reason Bristol really did not win, according to them, is that the city's many culturally interesting locations have actually come to be commonplace to the citizens and, thus, do not obtain much fanfare in media. When a new media centre of independent movie theater opens, there are no buntings, ceremonies or headings in the local paper. The city just tackles its business in its usual plain fashion. Which is one reason for Bristol's excellent appeal. Bristol's arts as well as media scene is 2nd only to London in terms of quality. Among the characteristics of this scene is the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School, which has actually regularly produced a lengthy line of talented actors, supervisors and behind-the-scenes experts for many years, as well as many of them have actually gone on to add lustre to the neighborhood arts scene. At the same time, the The top quality of arts as well as media in this field is remarkable, 2nd only to London. As an example, Bristol is house to the outstanding Watershed Media Centre, the first media centre in the nation, is an impressive display of various digital art events and also media installments. On top of that, the Aardman Animation workshop has actually brought wonderful fame to the city for its innovative use plasticine as well as stop-motion animation, particularly in such well-liked attributes like Wallace as well as Gromit, Chicken Run as well as Morph. If you have an interest in Bristol's background, a great location to check out would be the Bristol Industrial Museum, which has fascinating exhibitions on the city's different modes of transportation over the years in addition to Bristol's part in the slave trade. Located at the Princes Wharf, the museum also houses a splendid collection of heavy steam powered cars. Set amidst Georgian style, the attractive Clifton Shopping Arcade is a display of regional art as well as crafts. The amazing Clifton Suspension Bridge is another enforcing instance of Bristol's cultural background. It was created by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, Bristol's most well-known adopted son. This leader of design and also style had many excellent payments to the social landscape, most of which can still be seen today. Brunel coincides engineer in charge of several visitor views and monuments around the city centre, including the Great Western Railway that connected Bristol and also London in the 1830s and two of the initial steamships constructed in Bristol, the SS Great Western and the SS Great Britain, which can still be viewed at the dry docks. The SS Great Britain has the one-of-a-kind difference of being the initial iron, propeller-driven ship on the planet. Brunel is only one of the several remarkable Bristolians who have actually contributed much society and history of the city and of the world. John Cabot is one more such leader. In 1497, he cruised from Bristol to Newfoundland on a historic journey. Likewise referred to as Giovanni Caboto, this Italian navigator and also traveler is credited as one of the initial early modern Europeans to uncover the North American mainland. Today, much of Bristol's roads have Newfoundland in their name to memorialize Cabot's accomplishment. Archibald Alec Leach, born upon Hughenden Road in Horfield, Bristol in 1904, would take place to become one of one of the most well-known as well as favorite film stars worldwide. If his name does not call a bell, don't be stunned. The globe recognizes him much better as Cary Grant. He took a special niche as the charming and funny gent that everyone loves in such flicks as Bringing Up Baby, To Catch A Thief and also An Affair To Remember. Although Grant would certainly later on think American citizenship, he never forgot his roots and would often return to Bristol to look at his mother. Bristol's women would additionally cast a great darkness on the city's cultural as well as historical landscape. One of one of the most preferred is Bristol's adopted daughter, Mary Carpenter. Born in Exeter in 1807, Carpenter was significantly worried about the suffering of Bristol's school children during the 19th century. In feedback, she developed an evening college for road youngsters and also authored a publication entitled "Juvenile Delinquency," which was a crucial recommendation during considerations that resulted in the flow of the Juvenile Offenders Act of 1854. That year, Carpenter also established a reform school for women. A regional woman, Elizabeth Blackwell, would go on to become the initial female doctor in background and also is credited with damaging down the barriers for females in medicine. She was born in Counterslip, Bristol in 1821 as well as would certainly arrive to New York in 1831. Blackwell conserved her own cash as well as, when she was old sufficient, she signed up in medical college and also would later finish as an MD.

0 notes

Text

2 Day Guide For Bristol Visit

Intro This overview is planned for visitors or travelers that are limited to a 2 day trip to Bristol. There is a brief historic section complied with by the 6 'must see' places or tourist attractions which Bristol has to offer followed by an option of great Hotels or accommodation which are in closeness to the picked attractions. History The city stands at the mouth of the river Avon which streams into the Severn Estuary in England, which consequently flows straight right into the Atlantic Ocean. Hence considering that middle ages times Bristol created as a significant sea faring port in England. In 1497 John Cabot set out from Bristol in his ship The Matthew with a team of 26 and also is attributed with the discovery of America. Latterly a variety of Americans have been able to trace their ancestry back to that initial trip. In 1547 the city was checked out by Queen Elizabeth 1 and also described the Church of St Mary Redcliffe as the 'fairest, goodliest and also most well-known Parish Church in England'. Profession from the City was and expanded improved significantly by the advent of the Slave Trade in the 18th Century. Bristol ships would certainly cruise to Africa where servants would be purchased or traded for goods and after that carried on to The West Indies and also America where they were sold on or exchanged for Tobacco, Sugar as well as Chocolate. Bristol ended up being a centre for Shipbuilding to very high criteria as well as gave rise to the expression 'ship form as well as Bristol style'. It was here that Isambard Kingdom Brunel developed and developed The SS Great Britain, back then the globe's largest iron, drove steamship. She was released by Prince Albert in 1843 and also sailed on her initial trip to America in 1845. Brunel likewise famously developed the Clifton Suspension Bridge, which spans the Avon Gorge in Bristol. He passed away 5 years before its completion in 1864. Nowadays the City is extremely cosmopolitan and also has a thriving service and also financing quarter along with a large trainee population at the city's 2 colleges. 6 'Must see'attractions in the 2 days 1. The Clifton Suspension Bridge The bridge is only a brief range form the city centre. It covers the Avon Gorge and also is a splendid testament to the brilliant of Brunel. Make certain to watch it from listed below by cars and truck as you drive along the Portway after that up bridge Valley Road. Park on the Clifton side of the bridge and also stroll throughout the bridge to take in spectacular sights in the direction of the city or down the Avon Gorge. 2. St Mary Redcliffe Church This church was constructed by the Merchant Venturers of Bristol as well as is so grand in aspect as well as design that it is regularly misinterpreted to be the Cathedral. Try its Undercroft coffee shop where normal online jazz sessions are held. 3. Trip of the Docks and waterfronts by Ferry. Go to the city centre where ferryboat trips leave regularly throughout everyday of the year. Take the directed excursion ferryboats which are extremely low-cost and also observe many appealing waterfront features as well as sites consisting of The Arnolfini Gallery, The Watershed Media Centre, The Industrial Museum (currently closed for repair as well as flanked by the 19th Century Cranes), the outstanding Lloyds TSB Headquarters structure and a reproduction of The Matthew tied together with the large SS Great Britain. 4. The SS Great Britain and also The Matthew The SS Great Britain was brought back to Bristol in 1970 after being left to rot in the Falkland Islands after haing its mast damaged in tornados off Cape Horn. The ship has undertaken constant repair in dry dock as well as is currently a stunning gallery which has actually won several significant vacationer honors. Berthed together with in the water is the reproduction of The Matthew (see History area over), which is a working ship/museum which can be worked with for sailings and also whereupon journeys can be taken in the docks location. One entryway cost consists of both ships. The Matthew is dwarfed by the SS Great Britain as well as it is tough to consider the cramped conditions Cabot and also his crew of 26 must have sustained in their voyage across the Atlantic to America. 5. The British and Empire Commonwealth Museum at Temple Meads Station This museum is located at the mainline railway station in Bristol The original Terminal for the GWR was made by Brunel as well as now houses the Museum alongside the more recent station. Just recently the Museum has currently taken over the housing of the Slave Trade Exhibition which was previously at the Industrial Museum in the Docks. 6. Centuries Square, IMAX, Wildscreen and also Explore @ Bristol. This is a modern-day waterside complicated improved the site of former warehouses at Canons Marsh. This is an incredibly popular area for visitors with children - there being lots of fascinating water features for youngsters to play in. The IMAX movie theater is a 3D movie theater with programs for youngsters as well as the contemporary Wildscreen and Explore @ Bristol are hi-tech contemporary scientific research and nature themed buildings as well as hands on exhibits. Hotels close to the attractions Jury's Hotel, Prince Street This 4 star resort is on the waterside near the Watershed Media Centre as well as to the Arnolfini Gallery. The Marriot Royal Hotel, College Green, Bristol This is Bristol's many elegant hotel (4star) located on College Green alongside the Cathedral as well as is generally often visited by actors and stars doing at the City's Hippodrome Theatre close by. Originally Victorian today entirely refurbished. Mercure Brigstow Hotel, Welshback, Bristol This is Bristol's latest modern hotel with a central riverside area. Near The renowned Llandoger Trow pub and hotel and also The Duke bar (live jazz sessions evenings as well as weekend breaks). The Youth Hostel, Narrow Quay, Bristol Runs from a converted storehouse exactly on the waterfront, close to the city centre and also is outstanding value for cash. The Avon Gorge Hotel, Sion Hill, Clifton, Bristol This Hotel delights in a stunning aspect ignoring the Avon Gorge and also the Clifton Suspension Bridge. Its outside sunlight balcony bar which forgets the Gorge and also Bridge is popular in Spring as well as Summer.

0 notes

Text

Almost Halfway There: Miles 4-6.

Miles 4 - 6

Albertbridge Road - Newtownards Road - Dee Street - Sydenham Bypass.

The next few miles takes us into the heart of East Belfast. As you turn on to Albertbridge Road you will notice a large ‘Peace Wall’ to your left. This separates the Catholic Short Strand from the Protestant Cluan Place. A remnant from the Troubles that continues to enforce the differences between the two communities, just in case you ever wonder why there’s still tension in this city, when you grow up with a literal wall between you and your neighbours you tend to harbour a sense of mistrust.

Further along the road, you may notice a large stone outside the XOXO Tanning Club. This is the Long Bridge Stone. The Long Bridge crossed the Lagan between 1688 and 1841. It was demolished and replaced in 1841 by noted Belfast architect, Francis Ritchie. While Ritchie was demolishing the bridge, a friend of his, a Doctor who lived on the junction between Castlereagh Street and Albertbridge Road requested a stone from the bridge as a souvenir. Ritchie obliged and placed the stone in the Doctor’s garden. As the years went by, the Doctor’s home was replaced with a bar known as McShannon’s but the stone remained. Local folklore claimed that the Long Bridge Stone was actually the mounting stone used by King William of Orange to mount his horse on his way to the battle of the Boyne, however King William was in Ireland 150 years before the stone was placed there and certainly never made it to the Albertbridge road. The Long Bridge was replaced by the Queen’s bridge, which you will cross around the 9th mile.

There are a few interesting architectural points along the Albertbridge road. There is the old Musgraves Factory, now The King building, a multipurpose office and retail building, you will notice the balcony above the main door featuring the heraldic badge of the Prince of Wales, ���The Prince of Wales’s Feathers’. If you look closely, you may also see a small statue of an owl attached to the balcony. This is a nod to the scout troop ‘Owl Patrol’ which used to meet in the YMCA Mountpottinger building which is a bit further up on the right. Opposite the YMCA building is the Ballymacarrett Orange Hall, completed in 1901. All 3 are quite beautiful buildings, but unfortunately are in a bit of disrepair.

Just before you get to the YMCA building, you will notice a small park on the left hand side of the road. This is the Bridge Community Garden which is home to the Soundscape Park Project. Here, loudspeakers are hidden around the garden and play sounds from all over the world, from the crashing of waves, the sounds of the Amazon Rainforest to the factory sounds of Harland and Wolff.

As you approach your 6th mile you turn onto the Newtownards Road, in case the Albertbridge Road left you in some kind of doubt, the Newtownards Road should confirm your suspicions that, yes, this is a Protestant, Loyalist part of the city. You will notice shops selling instruments and paraphernalia for Orange marches and Loyalist band parades, as well as flags supporting the various provinces of the United Kingdom and British Army.

A prominent building on the Newtownards Road is the Portview Trade Centre. Originally the Jaffe Spinning Mill named for its founder, prominent Belfast citizen, Otto Jaffe it was sold to Mackie’s in 1912 and became the Strand Spinning Mill. Here, flax tow, munitions and viscose rayon were produced until 1983 when the mill closed. It is now home to numerous businesses including Boundary Brewing, a co-op owned local brewery who host monthly tap rooms and supply beer to various bars around the city and the rest of the world.

An indication to turn right onto Dee Street is the Great Eastern Bar. An absolutely stunning building built in 1890. Named after the Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s iron steamship, The Great Eastern. A ship that was built in London in 1858. It has changed name a few times over the years including the Red Hand Bar and the Ulster Arms, but was changed back to the original Great Eastern Bar in the 1970s.

Dee Street is home to the Harland and Wolff Welder’s club, you will see a small plaque on the wall outside commemorating 8 men who lost their lives constructing the Titanic. This street will also be your first clear look at the Harland and Wolff cranes, Samson and Goliath.

As you cross over the Dee Street Bridge, the cranes come into view and you turn a corner onto Sydenham bypass. The Sydenham bypass was the first dual carriageway in Northern Ireland with work beginning in 1938 and fully opening in 1959.

This isn’t the most interesting stretch to run down, but there are one or 2 spots of interest. You will be able to see The Oval stadium which has been the home ground of Glentoran FC since 1892 and has been the site of numerous protests through the years, including a protest in 2008 by the Free Presbyterian Church of Ulster against the IFA’s decision to hold games on a Sunday. Hopefully they don’t find out which day the half marathon is on this year.

Come back next time for a little about the next stretch of the race. You’re almost halfway home.

Thanks again to everyone who has been reading these posts and donating to my fundraiser.

There’s still time to donate here.

Jonny

0 notes

Text

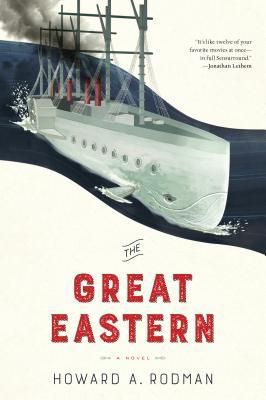

Gleeful Abandonment of Restraint: An Interview with Howard Rodman, Author of The Great Eastern

Some months back I ran across a rather mysterious book. It bore no title, nor any other identifying information, just a bold strip of white text across an otherwise dark cover: “It's like twelve of your favorite movies at once, in full Sensurround.” It would take a far stronger man than I to resist that temptation, let me tell you. I opened it straightaway and didn’t put it down until I was done. What I had in my hands was an advance copy of one of the most singular and multifarious novels I’ve encountered in a good long while. The only thing I didn’t like about it was knowing that I’d have to wait to be able to share it widely.

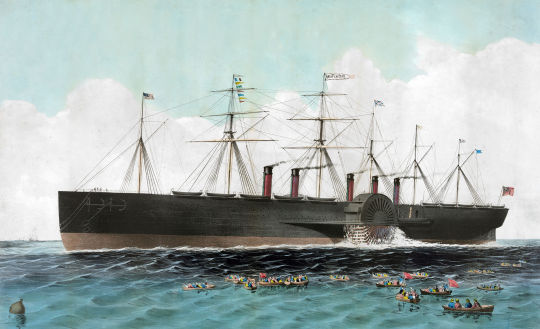

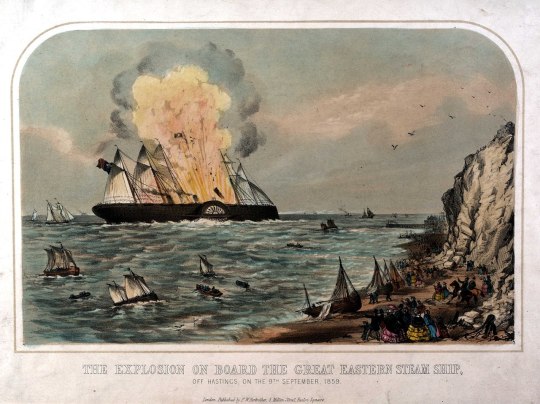

The Great Eastern tells the true story of the SS Great Eastern, a technological marvel of the Victorian Age. Designed and built under the direction of Isambard Kingdom Brunel (yes, his real name), it was, at the time of its 1858 launch and for decades afterward, the biggest ship ever to sail. The details of its construction, the disaster of its launch, and its eventual triumphant role in laying the first transatlantic telegraph cable make for a gripping read.

There’s much more to the novel, though. In addition to being a sober historical account, The Great Eastern is also a fanciful tribute to the greatest tales of adventure from the 19th century. Wrapped around the reality of the monumental steamship is a rip-roaring plot that sees the anti-heroes of Moby-Dick and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea do battle with the fate of civilization at stake.

So wait, you’re saying. An obscure English engineer describes his love for metallurgy and manufacturing for pages at a time while Captains Ahab and Nemo make grandiloquent speeches and engage in all manner of creative steampunk-inspired violence? Yes, and it works. Remember how the players in Hamlet said they could perform any kind of drama, discretely or in combination? Author Howard Rodman has taken up their challenge and danced with exquisite grace along the knife edge separating fact and speculation to produce an incomparable tragical-comical-historical-industrial, a brand-new fictional genre of his own devising.

Finding out a bit more about Rodman and his varied talents, I realized I shouldn’t have been too surprised by the sheer muchness of his book. As well as being a novelist, he is professor of screenwriting at USC's School of Cinematic Arts; a member of the National Film Preservation Board; and thanks to the French government, a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres [Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters]. Among his screenplays is Joe Gould’s Secret, based on the life and work of one of my favorite writers, Joseph Mitchell.

The Great Eastern (book, not boat) was successfully launched this week, and to celebrate its maiden voyage, Howard Rodman was kind enough to answer a few questions for me. Read the full interview below, and read the novel as soon as you can.

--James

----------------------------------

James Crossley: Why did you choose to cast fictional characters as your protagonists rather than their real-life creators, Herman Melville and Jules Verne?

Howard Rodman: My previous novel, Destiny Express, set in Berlin’s pre-War filmmaking community, featured two real-life protagonists, Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou, as well as a number of “walk-ons” (Brecht, Goebbels, et. al.). It seemed more fun, this time around, to borrow characters already fictional: to inhabit the figures that Verne and Melville created rather than the authors themselves.

JC: Does that choice say anything about historical fiction or speculative fiction as genres? As I ask this I'm thinking that this two-part conversation between Kim Stanley Robinson and Francis Spufford would have been even more interesting as a triangle with you at one apex.

HR: Much of what I’ve written, as a fiction writer and as a screenwriter, has been set in period. I do love the research that writing historical fictions necessitates, the density of vocabulary, timeline, technology, that the world-building requires. What’s more fun than to discover the exact right word, now near-extinct, for an object or routine no longer part of our daily lives?

But as to the distinction between historical fiction and speculative fiction—that membrane is more than permeable. Caroline Edwards maintains [in the article linked above], correctly I think, that all historical fiction is alt-history. As proof: the authorial community can only answer the Munchausen question (“Vas you dere, Sharlie?”) in the negative. So we’re all of us making shit up all the time. Which is, of course, a tradition that goes back to Beowulf, the Iliad, and far beyond.

JC: Do you think your film background makes this a particularly cinematic work? Or is writing a novel a completely separate artistic activity?

HR: When I’m writing screenplays, I’m tightly constrained by format: 117 pages and you’re out; no digressions; each page must give you a reason to turn to the next one; and a stringent injunction against getting inside your characters’ heads (as opposed to showing what they say and do). For me, writing fiction is a gleeful abandonment of those restraints. On a good day it feels like freedom; on a bad day, like mere reaction formation. (Bad-boy acting out.)

To make matters more confusing: the book’s been optioned, and I’ve been contracted to write the film adaptation. So I need to summon both wild imagination (so as not to simply pour amber over the published tome) and appropriate restraint (the abovementioned requisites of screenwriting). I find refuge in that old saw of Gide’s: “Art is born of constraint … and dies of freedom.”

JC: Why employ a chronology that leaps back and forth over the years?

HR: I was interested in certain chronological rigors (months were spent dadoing and rabbeting the Verne, Melville, Brunel timelines), but also in deploying the narrative in the order I hoped would best entice the reader. The back-and-forth was intended—and whether it succeeded is not for me to say—to incite many small mysteries. Whereas a strict chronological narrative might succumb to and then, and then, and then.

JC: If I wanted to get highfalutin' about it, I'd say that The Great Eastern is highly polyvocalic. Less insufferably, I'll just say that its very coherent story is actually told in bits and pieces by a number of very different characters. Was this an accidental effect or the residue of design?

HR: Ahab and Nemo are, I’d maintain, the two great anti-heroes of 19th-century fiction. But both of them are, in their own ways, opaque. Melville doesn’t even tell us Ahab’s first name; the biographical details of Nemo’s life are withheld from Twenty Thousand Leagues and rendered only telegraphically in Mysterious Island. Thus from the beginning I wanted to give them their own subjectivities, their own voices: a Nemo with the carriage and diction of a Cambridge-educated Indian prince; an Ahab with the wild take-no-prisoners American yawp of an Iggy Pop or a William S. Burroughs.

Building from there, I wanted a Brunel voice, finding the sentiment within the engineer’s precision, the hesitations beneath the relentless can-do. And toward the end knew I needed yet another voice, that of Ahab’s lover, a character less mythic than the three previous, but no less crucial.

JC: I hope this isn't a spoiler, but I'm not sure that you've done the commercially astute thing and left yourself open for a sequel. What are your plans for your next book?

HR: Nemo dies at the end of Twenty Thousand Leagues. He dies again at the end of Mysterious Island. The Great Eastern assumes that the second death was as provisional as the first. And building upon this: that the well-known deaths of Ahab and Brunel were equally contingent.

Not to indulge in plot spoilers, but one may safely assume that there is no death in The Great Eastern so definitively documented as to preclude a subsequent reappearance. I can say no more.

0 notes