#iraninan rice

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

#youtube#food#foodie#rice#persian#persian rice#zirashk rice#iraninan rice#safron rice#rice pulao#easy rice#delicious#reciepes#easy recipes

0 notes

Text

Beyond the Purim Story: An Introduction to Persian Jewry

Centered in the ancient capital of the Perisan Empire, the story of Purim offers a glimpse into the life of the Iranian jewry- a long standing community with roots beginning in biblical times to Contemporary Iran. In the Megillah, the orphan Esther, paves her way into the royal court, and later saves her Jewish people from destruction. Although historically questionable, the Purim tale in many ways, is a microcosmos of the history of the Iranian community. A saga that could be sketched as a linear graph with sharp ups and downs, from regality to poverty, from great political power to persecution. And to add to this extraordinary trajectory, It is also one of the few Jewish communities still existing (rather miraculously) in large numbers in a Muslim country, and under radical theocratic regime.

A portrait of Queen Esther

Despite this fascinating history and the important contribution of Iraninan Jews to global commerce (which will be discussed later), the topic received very limited scholarly attention. In fact, less than a handful of books were dedicated to Persian Jewry. I lament this on a personal level as I am Iranian from my paternal side. Therefore, this post is a humble attempt for reparation. It contains a short historical view, and aims to provide a sense of its rich folklore through the lens of fictional literature and culinary.

Major Milestones in the History of Persian Jews

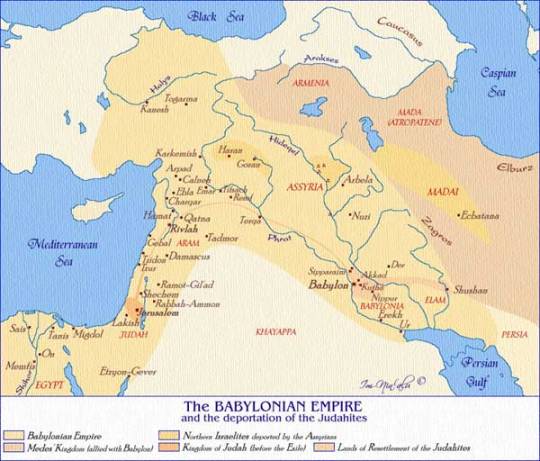

The Persian community is one of the oldest ones in the diaspora as it dates back to the Babylonian exile in the fourth century B.C. For the two centuries to follow, the Perisan community was linked to the Jewish communities in Babylonia and Mesopotamia. The famous Yeshivot (Torah learning academies) in Sura and Pumbedita, in which the Babylonian Talmud was crafted, were a source of guidance for the refugees in Persia. To this day, the Iraqi and the Persian communities bear much resemblance in terms of culture and religious practice. Their cooking (later discussed) is similar as well.

Babylonian Exile map

In ancient and medieval times, the Jews of Persia were well known as savvy and wealthy merchants. Situated in a prime location between China and India and Europe, Persian Jews were pivotal in what was then global commerce. Through the Silk Road and other networks of trades, Persian Jews imported spices and other goods, such as rice and tea to the west.

Silk Road’s Routs

Persian Jews were influential and properous through the first generations following the Arab Muslim conquest of Iran in the third centry A.D. Their status and living conditions deteriorated significantly with the accession of the intolerant Shiite Safavid rule. Under a regime, in which non- Muslims were considered impure heretics, Persian Jews were pushed to the margins of society and poverty. Excluding a short resurgence during the Sunni Mogul takeover of Persia in the sixteenth century, the Persian community lived under hardship and fear. The Shiite Shahs harshly oppressed minorities, denying them any position of power and restricting them to a few professions and areas of living. In several episodes in the course of the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Jews were expelled from the cities they lived in and forced to convert to Islam. Subsequently, many Persian Jews fled to Iraq, Syria, Samarkand and Georgia.

The economic and overall living situation improved in the late nineteenth century as Iran increasingly opened to the west. Although still segregated in Jewish quarters, urban Jews pursued western education. Jews, including women, gained proficiency in languages, such as English and French. They also increased their integration into local Iranian society, and named their children in both Hebrew and Parsi names. Jewish women did not veil, but they adopted the black Chador to cover their faces when out of the house. Similar to other Jewish communities at the time, girls were betrothed at age 8 or 9 and married when they were about 16. It was common for women to pilgrim to other parts of the country to visit sites, such as Queen Esther’s burial place, near Isfahan.

Queen Esther’s Tomb

The rise of the Pahlavi dynasty in 1925 marked a turning point. This transformation allowed the Jews once more to be in a position of influence both politically and economically. Many immigrated from the hinterland to Teharn to explore new opportunities, and a few became close to Risa Shah and other men in powerful posts. For the most part, this elite chose to stay in Iran after Israel’s Independence. The lower and middle class Jews opted to immigrate to the new Jewish State in 1948.

The Muslim revolution in 1979 drew a sharp decline in the status and overall safety of Iranian Jews. After decades of prosperity, the Jewish community was once again isolated and in grave danger. The initial period of the new Isalimic republic was particularly traumatic given constant harassment and even execution of several Jewish businessmen for their alleged connection to Israel and the United States. In the following years, the situation seemed to stabilize, and Jews were given a certain degree of religious autonomy. Although most Iranian Jews fled the country in several waves in the aftermath of the revolution, a sizable group remained. Today, their number is estimated at nine thousand. Given the lack of reliable information, their overall condition is unclear. Recent imgirants paint an ambiguous image of harmony with Muslim neighbors, and yet a feeling of imminent threat. Unsurprisingly, Iranian news reports emphasize the community’s well being and alignment with the regime.

Images of contemporary community life

Outside of Iran, Israel and North America are the main hubs of Iranian Jewry and smaller pockets exist in London, Melbourne and Buenos Aires. Two significant communities in the United States are located in Great Neck, New York (also known as Persian Island) and in Los Angeles (it’s estimated that about 25 percent of Beverly Hills population is of an Iranian- Jewish descent). Many of the immigrants in America were able to bring their fortune to the new land and used their capital and expertise to start businesses in the clothing, food and electricity industries.

In Israel, as an attempt to integrate, Iranian Jews adapted to the culture and values of mainstream society while leaving their own heritage behind. This may be a gross generalization, but sociological studies, statistics and experience of living in Israel suggest a trend of assimilation. As a result of their pragmatism, Iranian Jews have made great accomplishments in the sphere of public service. The IDF, in particular, was a stepping stone to obtain power within the military (and later in Israeli politics). Among its current and former ranks, one can find a high number of generals of Iranian descent, including two chiefs of staff.

Real Persian Housewives

An exception to the unspoken policy of concealing Persian legacy is the author Dorit Rabinyan. Born in Israel into a warm tight knit Iranian family, Rabinyan used her gift for writing to bring Persian tradition into the spotlight. Inspired by her grandmothers and aunts’ tales of life in the old country, Rabinyan published her first novel Persian Brides (titled in Hebrew, The Almond Tree Road in Oumrijan) when she was only 21 years old. The book, an immediate bestseller, was widely translated and praised by critics, describing Rabinyan as a meteor and comparing her to Gabriel García Márquez”.

Dorit Rabinyan

In Persian Brides, Rabinyan masterfully crafted a new hybrid of Hebrew- rich and whimsical -Parsi sounding text. Through her vivid language, Rabinyan invites the reader to experience the surreal Persian village of Oumrijan in the dawn of the twentieth century. The plot centers around two maidens, Flora and Nazie Retoryan, and their dramas involving marriages, pregnancies and relationships with their neighbors and the village demons.

Since marriage is a central thread in the book, there are many descriptions of ceremonies and superstitions involving the bride to be. One of them, hilarious and sad at the same time, is the qualification test performed the day before the wedding. This is a test run by the mother of the groom in order to assess if the future daughter in law will qualify as a housewife. So what makes a good Persian housewife? The answer is superior herb chopping skills... perhaps understandable given the amount of vegetables used in Persian cooking (see section below). During the test, the poor girl needs to demonstrate how quickly and meticulously she handles a massive amount of greens needed for Khoresht Sabzi- a traditional stew. The pressure around the “Sabzi test” was so daunting that bleeding injuries, including losing fingers, were common. Here is the excerpt from the book:

“The bride had to prove her skills in cleaning and chopping the Sabzi, the herbs that Janjan sold in the market...the women of the village and relatives circled the bride...On a silver tray, they put bunches of celery, traggon, sage, rosemary, mint, spring onions and parsley. Homma (the bride) was sitting on the ground with her legs crossed as the Sabzi stems hill reached all the way up to her breast… Homma began quickly by separating the leaves and the roots from the celery, the spring onion stems from its onion, the sage from its delicious smelling flower buds, all of these were soaked in a big water bowl. later, the mint, tarragon and parsley leaves were washed as well...Homma reached for the sharp knife. Its blade was shining, and the women were shushing each other. Nazie knew that the tested brides sometimes get injured because of the pressure, and sometimes they even cut off their fingers. When that happens they deposit the cut finger with their mother, and continue to chop while they are heavily bleeding. But if not a single blood drop spilled during the test, and the herbs were finely chopped, the women sang and danced in circles around the bride as she was proven to be a skillful and well trained cook at her parents’ kitchen”.

Khoresht Sabzi Recipe

In honor of poor Persian housewives, I am including here a recipe of Khoresht Sabzi. This is a more user friendly version of this staple dish as it allows using dried herbs (although I highly recommend fresh for flavor), and it calls for a smaller variety of herbs. Note though that other available herbs (for example, dill, traggon, basil) will be a wonderful addition to the herbs listed below. In addition, middle eastern grocers sell pre cut Sabzi mixes (either dried or frozen), which can make the process even easier. Lastly, I listed lamb as one of the ingredients, but variations are welcome. In my family, Khoresht Sabzi was served with chicken, but it is also fabulous as a vegan dish (see modification below) as I prepare it.

Khoresht Sabzi- Adapted from Najmieh Batmanglij’s book Food of Life: Ancient Persian and Modern Iranian Cooking and Ceremonies.

6 tbsp oil, butter or ghee

2 large onions thinly sliced

2 pounds lamb shank (optional)

2 tsp salt

1 tsp ground pepper

1 tsp turmeric

½ cup drained kidney beans - either canned or soaked overnight (increase the amount to 1 cup if omitting meat)

2 whole limu- omani - dried persian limes pierced

4 cups finely chopped fresh parsley or 1 cup dried

1 cup finely chopped fresh chives or scallions or ¼ cup dried chives

1 cup finely chopped fresh cilantro

3 tbsp dried fenugreek leaves or 1 cup chopped fresh fenugreek

¼ cup lime juice

1 tsp ground cardamom

½ tsp of saffron threads dissolved in

2 tbsp of rose water (or hot water)

Let the chopping begin

1. In a large saucepan (preferably a dutch oven), heat 3 tbsp oil over medium heat, and browned the onions and meat (if using). Add salt, pepper and turmeric, and sauté for 1 minute.

2.Pour 4½ cups of water, and add the kidney beans and dried limes. Bring to a boil, cover and simmer for 30 minutes stirring occasionally.

3.Meanwhile, in a wide skillet, heat 3 tbsp oil over medium heat, and sauté the parsley, chives, cilantro and fenugreek for about 20-25 minutes stirring frequently to avoid the burning of the herbs.

shrinking herbs

4. Add the herbs mixture, lime juice, cardamom, and saffron with its water to the large saucepan. Cover and let simmer for 2 -2 ½ hours, stirring occasionally.

Simmering slowly

5. Check if meat and beans are tenders and add salt if needed.

6. Serve warm on a bed of steamed basmati rice.

Gratifying bowl on a cold winer night

Festive, Aromatic and Nutritious: A General Note on Persian (and Jewish) cuisine

Khoresht Sabzi - quintessential among Jews and their Muslim neighbors- can shed light on the Iranian kitchen as a whole and its link to Persian folklore. The Israeli celebrity chef, Yotam Ottolenghi wrote on this topic, in his book Plenty More:

“My Previous life must have been somewhere in old Persia. I am absolutely convinced of this. I am completely infatuated with the richness of Persian cuisine, by its clever use of spices and herbs, by the inguianty of its rice making, by pomegranate, saffron, and pistachios, by yogurt, mint, and dried limes. It seems that my palate is just naturally honed for this set of flavors”.

Ottolenghi’s words well capture the exotic and diverse essense of Persian cuisine. Specifically, the culinary practices of contrasting dominant flavors (obtained by adding sour taste, such as pomegranate or lime juice to savory dishes), and textures (for instance, the combination of dried fruit and herbs) are indeed extraordinary. The slow cooking of a wide array of fruit (such as pears, apricots, dates and cherries), nuts (pistachios, almond and walnut) and spices (saffron, cinnamon and turmeric) also add a layer of complexity and colorfulness.

Typical Persian assortment

The Zoroastrian concept of duality between good and bad, light and darkness -embedded in Iranian culture- was a key factor in the development of Persian cuisine. It inspired the aforementioned balance between sweet and sour, hot and cold, lean and fatty that exists in many dishes. Concerned with health, and mainly digestion, Persian cooking offers a dichotomy between hot foods, which thicken the blood and increase the metabolism, and cold foods that do the opposite. Dates and grapes are, for instance, “hot”, while plum and oranges are “cold”. A diet consisting only of one type of food can essentially imbalance the body and lead to an illness. Accordingly, the high consumption of herbs and green vegetables in almost every meal also stems from the concern regarding nutritional properties adjuncting food and medicine.

Iran’s historic role in importing goods from the far east and its interactions with its neighboring regions also shaped the culinary culture. Particularly, the Mogul - indian conquest and the long Ottoman reign increased the selection of spices, and introduced dishes, such as baklava and yogurt to the Iranian repertoire. These interchanges also spread Iranian staple dishes to other parts of Central Asia and the Middle east. Sephardic communities in these areas, particularly in Iraq and Turkey, adopted the Persian combination of fruit with meat, and rice with legumes.

Rice is perhaps the most iconic Iranian staple. It is made with a sense of perfection aiming to avoid porridge-like texture. Rice is commonly prepared either as Choleh - steamed with saffron scent and a crunchy crust (Tahdig) or as pilaf - mixed with vegetable, fruit and beans. A very colorful pilaf is the Wedding rice served with almonds and dried fruit.

The Art of Tahdig

Hearty stews, known as Khoreshts (such as the aforementioned Khoresht Sabzi) frequently accompany the rice. Khoreshts are vegetable and herb based but utilize local ingredients unique to specific regions of the country (caviar in the Caspian sea area, for example). Another important dish is Kuku- a savory bake that can be compared to crustless quiche (or an Israeli Pashtida). Popular Kuku are made out of herbs, eggplant (also known as Iraninan potato) and my favorite cauliflower. At the end of the meal, Iranians enjoy a cup of tea served with a sugar cube and a nut based treat, such as nougat or walnut cookies.

Kuku: Colorful and heathy

Persian-Jewish cuisine is basically identical to the majority cuisine with one main distinction. Due to Kosher dietary laws that separate meat and dairy, Jews refrained from using Ghee (clarified butter) and yogurt in meat stews. Iranian Jews contributed a very popular dish to the Iranian collection - Gondy chickpeas dumplings that are traditionally cooked in chicken broth.

Gondy: The Persian answer to Matzah Balls

6 notes

·

View notes