#indigenous lifeways

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

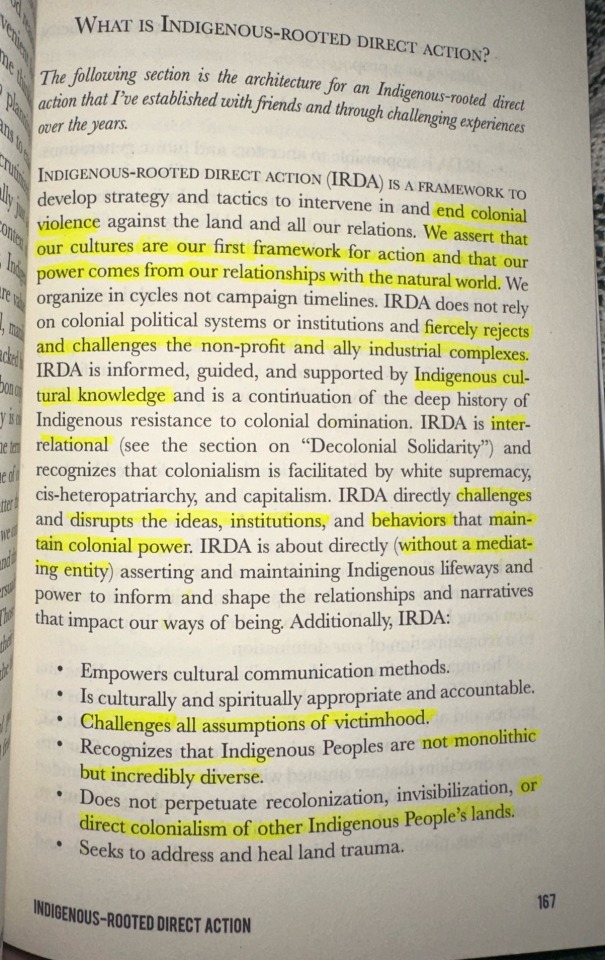

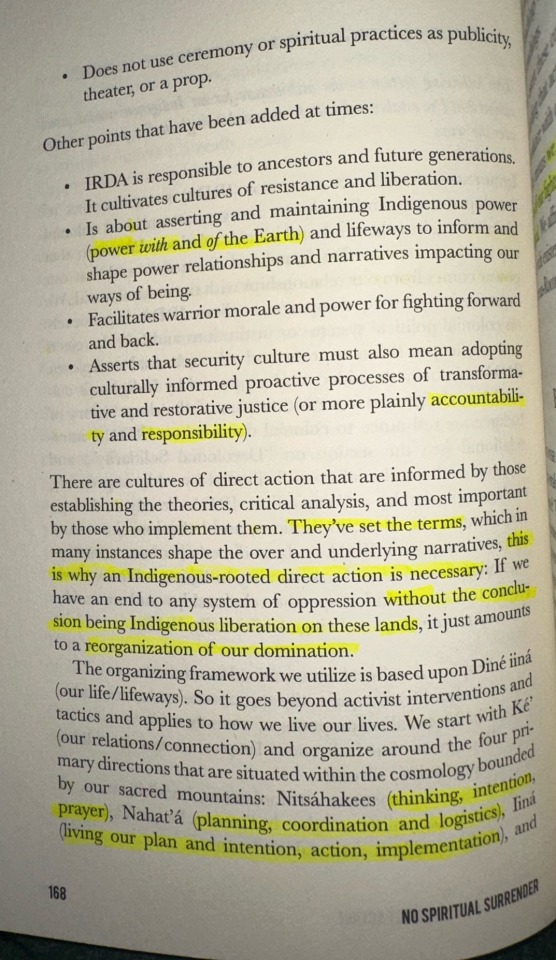

Excerpt of ‘What Is Indigenous-Rooted Direct Action?’ from Klee Benally’s “No Spiritual Surrender”

#Klee Benally#Diné#indigenous resistance#indigenous direct action#direct action#indigenous lifeways#indigenous action#decolonial land back#decolonization#decolonial theory#land back#indigenous land back

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yahgan

The Yahgan, also known as Yámana, are an Indigenous people native to the southernmost regions of South America, particularly the islands and coastal zones of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago in southern Chile and Argentina. They are historically known as the southernmost human population in the world, having adapted over thousands of years to one of the harshest climates on Earth. The Yahgan language, culture, and way of life are singularly shaped by the subpolar maritime environment, making them one of the most remarkable examples of human adaptation to extreme ecological conditions. While their numbers have dwindled significantly due to colonization, disease, and cultural assimilation, efforts are ongoing to preserve and document their heritage.

Historically, the Yahgan inhabited a vast maritime zone encompassing the southern tip of South America, including the Beagle Channel, the islands of Navarino, Hoste, and the Wollaston and Hermite island groups, extending even to Cape Horn. Unlike other Indigenous groups in the region such as the Selk'nam, who occupied the interior of the main island of Tierra del Fuego, the Yahgan were coastal dwellers, relying extensively on the sea for sustenance. Their domain was characterized by dense fjords, glacial channels, and rugged archipelagos, where wind, rain, and cold were constants. Their mobility by canoe allowed them to traverse large distances among these islands, and their settlements were typically temporary, reflecting a semi-nomadic lifestyle.

Archaeological evidence suggests that Yahgan ancestors have inhabited the region for at least 6,000 to 10,000 years. Early sites, such as those at Wulaia Bay and other parts of Navarino Island, have yielded substantial middens of shellfish, bones, and tools, attesting to a complex and long-standing adaptation to a marine-based subsistence. Genetic and linguistic data place the Yahgan within the wider group of Indigenous peoples of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego, though they are linguistically and culturally distinct. They are sometimes classified with the Alacaluf (Kawésqar) and the Chono as part of a larger “canoe people” tradition of the Patagonian archipelagos.

The Yahgan language, often referred to as Yámana, is a language isolate, meaning it has no known relationship to any other language family. It is highly polysynthetic, allowing complex ideas to be expressed in single words through the use of affixes. Yámana has an elaborate verbal system and a rich lexicon related to the natural environment, including extensive terminology for navigation, weather, marine life, and coastal geography. The language has undergone a drastic decline since the late 19th century, primarily due to the disruption of traditional Yahgan life and assimilation pressures. Cristina Calderón, who passed away in 2022, was considered the last fully fluent native speaker. Efforts are now underway by linguists and cultural organizations to document and revive the language through preserved texts, audio recordings, and community education.

The Yahgan economy was traditionally based on foraging, fishing, hunting, and gathering along the coastal marine ecosystem. Men primarily hunted sea lions, collected shellfish, and fished using bone hooks and woven traps, while women were chiefly responsible for gathering mollusks, crustaceans, sea urchins, and other coastal edibles. The Yahgan used sophisticated dugout canoes (constructed from bark or hollowed-out logs) to navigate their aquatic environment. Fireplaces built in these canoes allowed them to stay warm while traveling, an innovation that astonished early European observers. Their use of fire, in fact, was so characteristic that early European explorers, such as Ferdinand Magellan, named the region “Land of Fire” (Tierra del Fuego) upon seeing the multitude of fires onshore.

Their toolkit included stone and bone implements, harpoons, fishhooks, and baskets woven from rushes and grasses. They also utilized the pelts and sinews of marine mammals for clothing and tools. Unlike other hunter-gatherer societies, the Yahgan did not engage in agriculture or animal husbandry.

The Yahgan lived in small, kin-based bands that moved seasonally according to resource availability. These groups were relatively egalitarian, with a flexible social structure. Leadership was informal and often based on age, wisdom, or oratorical skill, rather than hereditary status. Extended families cooperated in subsistence tasks, and property was largely communal.

Family units typically occupied small dome-shaped huts made of bent poles covered with grass, bark, or animal skins. These dwellings were adapted to withstand wind and rain and could be easily dismantled and relocated. Gender roles were clearly defined but not rigid; both men and women contributed significantly to the group’s survival.

Yahgan cosmology and belief systems were animistic and closely tied to the natural world. They believed in a spirit world inhabited by beings associated with animals, landscapes, and weather phenomena. Mythology and oral traditions were central to Yahgan culture, with tales of powerful ancestral spirits, heroes, and supernatural beings. One of the most well-known mythological figures is Watauinewa, a culture hero and shaman who features in many Yahgan stories.

Shamans (or yecamush) were spiritual leaders who mediated between the physical and spiritual realms. They were believed to possess healing powers, the ability to control weather, and knowledge of sacred rituals. Initiation rites and ceremonial dances were conducted to ensure social cohesion and reinforce cosmological beliefs, though much of this ceremonial life has been lost or obscured due to colonial disruption.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Yahgan life is their physiological and cultural adaptation to the extreme cold and wet conditions of their environment. Despite average temperatures rarely exceeding 10°C (50°F) and frequent rain, snow, and wind, the Yahgan traditionally wore minimal clothing. Instead, they used layers of animal fat (especially from sea lions) as insulation and relied on their high metabolic rate to generate body heat. Fires were kept constantly burning in canoes, huts, and campsites. They also used body painting and greasing as both insulation and ritual expression.

Recent studies in biological anthropology suggest that the Yahgan may have developed unique metabolic adaptations, including a higher basal metabolic rate, to cope with cold exposure. Their exceptional knowledge of local ecology, combined with technological ingenuity and social cooperation, allowed them to flourish in one of the world’s harshest inhabited regions.

Contact with Europeans, beginning in the 16th century and intensifying in the 19th century, had catastrophic effects on Yahgan society. Initial encounters were sporadic, but by the 1800s, missionary activity, especially by the British-based South American Missionary Society, led to more sustained contact. While some missionaries sought to protect and educate the Yahgan, the consequences included exposure to diseases such as smallpox, tuberculosis, and measles, which decimated the population. Land dispossession, cultural disintegration, and the disruption of subsistence patterns followed.

European settlements and sheep ranching displaced Yahgan groups from traditional territories, and violent conflict sometimes occurred. By the early 20th century, most Yahgan had been relocated to missions or marginalized settlements, such as the mission at Ushuaia, now the capital of Argentina’s Tierra del Fuego province.

The Yahgan have been the subject of significant anthropological and linguistic interest since the 19th century. Notable researchers include Thomas Bridges, a missionary who compiled a Yahgan–English dictionary and translated parts of the Bible into Yámana. His dictionary remains one of the most detailed records of an Indigenous language of South America, with over 32,000 words and extensive ethnographic notes. Martín Gusinde and Anne Chapman also conducted important 20th-century ethnographic work, documenting oral traditions, rituals, and cultural practices.

Despite early academic interest, the Yahgan were often romanticized or misunderstood in colonial literature, portrayed either as "noble savages" or as cultural anomalies. Modern scholarship strives for more nuanced, Indigenous-centered perspectives, acknowledging Yahgan agency, resilience, and innovation.

At the time of European contact, Yahgan population estimates vary widely, from around 3,000 to possibly 5,000 individuals. By the mid-20th century, fewer than 100 remained. Today, only a small number of Yahgan descendants survive, most of whom live in Puerto Williams on Navarino Island in Chile, and a few scattered across Tierra del Fuego in Argentina. While most no longer live a traditional lifestyle, many maintain a sense of Yahgan identity and participate in cultural revitalization efforts.

These include language preservation initiatives, cultural museums, and the teaching of traditional crafts, canoe-making, and navigation techniques. The Yahgan are officially recognized as an Indigenous people by the Chilean state, granting them certain legal rights and representation, although economic and political marginalization persist.

The Yahgan people are increasingly recognized as a symbol of environmental adaptation, cultural resilience, and Indigenous knowledge. In the face of climate change and ecological degradation, the Yahgan worldview—rooted in symbiosis with the marine environment—has garnered interest among conservationists and ethnobiologists. Their ancestral territory, now part of the Cape Horn Biosphere Reserve, is among the most biologically unique and least disturbed ecosystems on Earth.

Ongoing partnerships between Yahgan communities, scientists, and cultural institutions aim to ensure the survival of both the Yahgan heritage and the ecosystems they once stewarded. Such efforts are part of a broader movement to restore historical justice and amplify Indigenous voices in the global narrative.

The Yahgan represent a unique chapter in the human story—one of survival, innovation, and profound connection to a demanding environment. Their culture, language, and history are invaluable not only as records of the past but as blueprints for alternative ways of living in harmony with the natural world. Though reduced in number, their legacy continues to resonate through ongoing efforts in linguistic preservation, cultural revival, and environmental stewardship.

#yahgan#yámana#indigenous peoples#tierra del fuego#south american history#ethnography#cultural heritage#endangered languages#indigenous rights#human adaptation#first nations#native history#anthropology#ethnology#oceanic peoples#hunter gatherers#ancient cultures#maritime culture#archaeology#language revitalization#decolonize history#indigenous resistance#native voices#shamanism#body painting#traditional lifeways#nomadic peoples#forgotten histories#cape horn#beagle channel

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

genuinely, people feel free to say any shit to japanese folks online

i am constantly questioned on my own goddamn history by anime fans who think they are morally superior to me because they have uncritically consumed western perspectives on imperial fascism.

i’m not just learning history from books or online, i get to learn from my community and my relatives and my people who have built coalitions of resistance that have lasted for generations.

and not only that, i study how my ancestors and relatives walked on the earth. i keep seeds. i keep recipes. i keep fabric and crafts and stories and songs. history is so much more than the movements of the powerful, and it’s so, so much longer than the last 6000 years of nation states battling for dominance. the person who inspired this post blocked me for pushing back on their racism but i have a screenshot of their reply and their asks still show up in a search of their username. a lot of those asks had to do with anime fandom stuff. i’m so fucking tired of people who disdain the creators of what they consume.

#actually nikkei#imperialist colonialist fuckshit#the feeling when people assume that you are fash-adjacent and nativist because you talked about oral history in general#and indigenous lifeways on turtle island#which AGAIN. i am learning from my fucking friends and community members

1 note

·

View note

Text

These children kept a one year old alive for over a month after a plane-crash.

Four Indigenous children survived an Amazon plane crash that killed three adults and then braved the jungle for 40 days before being found alive by Colombian soldiers — bringing a happy ending to a search-and-rescue saga that captivated a nation and forced the usually opposing military and Indigenous people to work together. Cassava flour and some familiarity with the rainforest's fruits were key to the children's extraordinary survival in an area where snakes, mosquitoes and other animals abound. The members of the Huitoto people — aged 13, 9 and 4 years and 11 months — are expected to remain for a minimum of two weeks at a hospital in Bogota, Colombia, receiving treatment after their rescue on Friday.

Continue Reading.

#good news#survival stories#Huitoto people#CKA Columbia#Amazonians#indigenous people#lifeways#competence#civilization#South America#indigenous culture#global news

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Watership Down - first the film, then the book, is one of the most formative media influences in my life. I’ve written about it briefly, here https://i-blame.tumblr.com/post/69030937937/moniquill-moniquill-kucala-moniquill

but having watched the above video essay, I want to say more.

The first time I saw a deer up close was in my grandfather’s back yard; I was about four years old. I don’t remember the reason that my mom dropped me off at my grandfather’s house for an afternoon, but I know that it was unplanned - because he was in the middle of processing a deer. It had been field dressed, organs already removed, and was hanging by its ankle tendons from the t-shaped steel pole at one end of the backyard clothesline. I was startled, worried, concerned that the animal was hurt. There was blood! There was flesh!

My grandfather responded by calmly explaining what he was doing, step by step. Explaining why he was skinning the deer, and quartering it, taking it from this https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White-tailed_deer to this https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venison

He talked about hunting, and about gratitude, and about humans and our proper place in the world - what meant to live in a good way.

By the time my grandfather was cooking tenderloin medallions and plating them up to me with grape jelly (don’t knock grape jelly on meat until you’ve tried it!) and instant mashed potatoes, I wasn’t startled or concerned anymore. I had a deeper understanding of the way the world worked, of my role as a consumer, a predator. Of the responsibilities that entailed. I couldn’t have explained it then, of course, with my 4-year-old mind and vocabulary - but Philosophy had been set into motion. This is a core memory for me.

I did not have nightmares about the butchered deer.

I was six when I first saw Disney’s Bambi. I DID have nightmares about that; between Bambi and The Land Before Time, I was absolutely convinced that my mother was going to die. That I was being presented with these media themes to educate and prepare me for that eventuality. I am the youngest daughter of a youngest daughter, and I have an extended tribal family. My grandfather died when I was six. His was one of many funerals I attended at that age; his generation succumbing to age and illness. I was aware of mortality.

I wasn’t a ‘normal’ child, by the standard of the community that I went to school in. I was too poor, too indigenous, too very obviously autistic (without being diagnosed). I had very different media influences and interests than the other kids at my public school. No one else was deeply obsessed with David Attenborough’s documentaries (Life on Earth 1979, The Living Planet 1984, Lost Worlds, Vanished Lives 1989). No one else had even heard of Dot and the Whale. No one else in my class had Lifeways Lessons classes, because they didn’t have tribes.

I wasn’t terribly interested in most media intended for children; it was boring because it was simple. I didn’t feel motivated to watch Disney movies over and over. Don Bleuth films had more staying power in my mind; An American Tale, All Dogs Go To Heaven, The Land Before Time. More complex stories, stories that confront suffering and death. My mom read me CS Lewis and JRR Tolkein, Jack London and EB White - lots of other stories that were not ‘age appropriate’, stories that were written for People, not Children.

I watched Watership Down for the first time when I was about five, and my mom read the book to me when I was about six. I was not disturbed by the violence, being far more interested in the themes explored in the video essay above. I had, by this time, seen a rabbit skinned IRL. I’d eaten rabbit stew.

I did not have nightmares about Watership Down.

I failed to make friends with the kids at school, for the most part - I primarily socialized with my cousins. In fourth grade (age 9), my class did a unit on tropical rainforests, and I brought in this video: I did not think that there was anything at all controversial about it, but at about 32 minutes in David Attenborough talks about the Guarani people and their traditional ways of life. There’s footage of an unclothed man climbing a tree. His penis is briefly visible. THE CLASS WENT WILD, and the teacher rushed to turn the video off, and I was sent to the office. It caused a school-wide incident, and bringing in videos was thereafter banned. I was deeply, deeply confused by this series of events. The video had come from the public library - how could it possible be offensive? But the incident became a vector of bullying that followed me until middle school - the adults had confirmed to the kids that I had done something taboo, that I was fundamentally wrong in some way. I quietly came to the conclusion that Most People(™) are very stupid and very reactionary, that one has to carefully coddle and explain things to them.

It took me many years to only mostly overcome that conclusion.

Later that same year, I had my first real success in making a childhood friend - someone who came to my house after school and had sleepovers and such. She had transferred from another school and didn’t know I was THE WEIRD GIRL the way my other classmates did. I remember trying to introduce my favorite movies to her, as she introduced her favorites to me. She was a Horse Girl(™) and much more interested in Age Appropriate Girl Things than I was, but we shared a love of My Little Pony - I had a bunch of episodes on VHS, recorded off TV. She thought that https://mylittleponyg1.fandom.com/wiki/Rescue_at_Midnight_Castle was ‘too scary’ and preferred https://mylittleponyg1.fandom.com/wiki/My_Little_Pony:_The_Movie.

I showed her Watership Down. She freaked out about it. It gave her nightmares.

She was, as many people, deeply disturbed by the violence of the film. She had not, at the age of nine, seen animals butchered. She didn’t seem to care about the deeper meanings and philosophical treatises presented; the fact that there was violence and death was too shocking.

I’m not sure how to conclude this essay, except with this: Watership Down is now a litmus test, for me. If a person is aware of it and appreciates it, we’re intellectual compatible. If a person’s whole reaction is shock and disgust and cries of ‘nightmare fuel!’ then we are not.

217 notes

·

View notes

Text

#indian

Indigenous food systems are integral to our cultures, our lifeways, and the wisdom we leave behind for future generations. Today, I joined Indian Youth Service Corps participants and elders in their continuation of Acoma Pueblo's food system, seed by precious seed. https://x.com/SecDebHaaland/status/1846318942056247688

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

#indian

Indigenous food systems are integral to our cultures, our lifeways, and the wisdom we leave behind for future generations. Today, I joined Indian Youth Service Corps participants and elders in their continuation of Acoma Pueblo's food system, seed by precious seed. https://x.com/SecDebHaaland/status/1846318942056247688

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

#indian

Indigenous food systems are integral to our cultures, our lifeways, and the wisdom we leave behind for future generations. Today, I joined Indian Youth Service Corps participants and elders in their continuation of Acoma Pueblo's food system, seed by precious seed. https://x.com/SecDebHaaland/status/1846318942056247688

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

#indian

Indigenous food systems are integral to our cultures, our lifeways, and the wisdom we leave behind for future generations. Today, I joined Indian Youth Service Corps participants and elders in their continuation of Acoma Pueblo's food system, seed by precious seed. https://x.com/SecDebHaaland/status/1846318942056247688

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

#indian

Indigenous food systems are integral to our cultures, our lifeways, and the wisdom we leave behind for future generations. Today, I joined Indian Youth Service Corps participants and elders in their continuation of Acoma Pueblo's food system, seed by precious seed. https://x.com/SecDebHaaland/status/1846318942056247688

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

#indian

Indigenous food systems are integral to our cultures, our lifeways, and the wisdom we leave behind for future generations. Today, I joined Indian Youth Service Corps participants and elders in their continuation of Acoma Pueblo's food system, seed by precious seed. https://x.com/SecDebHaaland/status/1846318942056247688

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

#indian

Indigenous food systems are integral to our cultures, our lifeways, and the wisdom we leave behind for future generations. Today, I joined Indian Youth Service Corps participants and elders in their continuation of Acoma Pueblo's food system, seed by precious seed. https://x.com/SecDebHaaland/status/1846318942056247688

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

#indian

Indigenous food systems are integral to our cultures, our lifeways, and the wisdom we leave behind for future generations. Today, I joined Indian Youth Service Corps participants and elders in their continuation of Acoma Pueblo's food system, seed by precious seed. https://x.com/SecDebHaaland/status/1846318942056247688

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

#indian

Indigenous food systems are integral to our cultures, our lifeways, and the wisdom we leave behind for future generations. Today, I joined Indian Youth Service Corps participants and elders in their continuation of Acoma Pueblo's food system, seed by precious seed. https://x.com/SecDebHaaland/status/1846318942056247688

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Without Civilization People Would Starve, Epidemic Diseases Would Break Out and there Would be no Medicine to Heal”

Then ask yourself why the Hadza, for example, survive until today. Hunger didn’t exist in such lifeways, but to a rather high degree in the civilized world. Naturally you can reply that eight billion people can’t be fed by hunting and gathering and you would probably be right, even if food forests appeared overnight where there were once shopping centers, commercial districts, insutrial complexes, and streets. Precisely for that reason, even I don’t advocate for a return to pure gathering and hunting. Perhaps a means of agriculture will be found that is sustainable enough to provide for all people without continuing the colossal ecocide. Monocultures are definitely out. Here also, Indigenous cultures deliver us teachable lessons.

Regarding diseases, it is once again the opposite. Civilization first made possible the serious outbreak of epidemics. We are currently treading into an Era of Pandemics. I certainly don’t have a crystal ball, but I can’t imagine any scenario in a decivilized world where something like the current Corona Pandemic could kill millions of people, let alone that such a pandemic could even exist when you have destroyed its very basis for existence. The past should prove me right: epidemics first broke out regularly with the arrival of civilization. There were of course earlier infectious diseases, I certainly don’t want to lie. But never to the extent reached in the civilized world.

With that we finally arrive at the topic of healing and medicine and start off with a Fun Fact: an essential part of modern western medicine is based on the botanical knowledge of Indigenous peoples, which people appropriated in the course of colonialism and later synthesized. Indigenous cultures often utilized methods which modern science only barely understands, if at all. In fact, Indigenous groups as well as uncivilized/precivilized people have at their disposal not only a deep knowledge of nature, but also discoveries which have been lost to city-dwellers.

The majority of modern medicine doesn’t even heal but only relieves the symptoms. Take for instance medicines for the Diseases of Civilization like thyroid disease or diabetes, which as a rule must be taken for a lifetime in order to “manage” the illness. In decivilization, the cure itself stands in focus. Healing of the fissures which have grown inside the individual, between people, and between humans and nature. The fissures made by civilization, by power. Our modern medical progress is also anything but innocent – stop romanticizing it. Colonialism, imperialism, and horrific medical experiments largely on the African continent (as well as in the animal world) were always a part of this so-called progress. They remain to this day. My ancestors were tortured and killed so that today a pill can manage your illness brought about by the modern way of life.

Ask yourself: do I want to stand for the continued existence of this world, in which my children will be plagued by the same (and new) ills as me? Or do I want to take this destructive world and destroy it and renew it so that future generations can be spared from these ills? In the end, the best medicine is not fighting symptoms. In so doing, new symptoms often emerge and you end up taking Pill B against Pill A. Instead, you fight the underlying causes wherever possible. Here, at least, civilization is honest when it admits that it has created the worst illnesses and itself speaks of “Diseases of Civilization.”

We have and will all be mutilated in one way or another. Our psyche is damaged and we are destroyed physically by illness and disease. As Diseases of Civilization and other infectious diseases withdraw from life, the need for complex medicine will steadily decrease. A world which places healing at the center would energetically strive to heal ills. For the few modern medicines which could possibly be brought into a decivilized world, people will find non-civilized and anti-colonial ways to produce them. Today’s science also won’t suddenly disappear into thin air. (This also shouldn’t be taken to mean that you should suddenly throw out all your pills just because they have a colonial history behind them. We must recognize that the ills and destruction of our bodies brought on by civilization will not be undone overnight. It means to fight so that future generations will be spared these ills and destruction by tackling the root causes. Some will be corrected quicker than others – a change in lifestyle and diet, the abolition of work, letting wild the surviving specks of the Earth, all can have a quick and not insignificant impact. On the other hand, some threats will continue to harm us for a long time. The poisons which have accumulated into the soils, for instance, will remain with us for decades and centuries.)

With this piece I hope to have offered a glance at a perspective on restoring our lost anarchy, and to have shown that it is modern society which is backwards-looking, not primitive lifeways. Alongside eurocentrism, modern-centrism is revealed to be a grave problem. Our society endlessly describes the possibilities offered by modern technology and entirely ignores what it simultaneously takes from us. It is of critical importance that we examine with sober and objective eyes what we have won with the coming of civilization, but most of all what we have lost.

#affinity groups#anti-civ#anti-colonialism#anti-technology#Black#Black Anarchism and Black Anarchic Radicals#decivilizing#decolonization#disability#egoism#german#indigenous#interpersonal relationships#post-civ#post-colonialism#switzerland#translation#anarchism#anarchy#anarchist society#practical anarchy#practical anarchism#resistance#autonomy#revolution#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#daily posts

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Within this sacrificial cosmology, no single hierophant or high priest needs to wield the fatal blade, and no one need bear witness to the horror. The sacrifice transpires in the clinical anonymity of market relations. An increase in demand for snack food in India triggers a chain of market decisions that see the forced displacement of an indigenous community in West Puapa and, with it, the liquidation of their entire lifeway and cosmology. The anonymous demands of shareholders in a cosmetics firm for greater returns leads to land grabbing by entrepreneurial smallholders or their hyper-exploitation of migrant workers. A subtle shift in policy to encourage markets to turn to biofuels triggers a wave of peatland burning that releases massive amounts of carbon into the atmosphere, contributing to murderous impacts on global human and non-human populations via the vicissitudes of climate change.

Max Haiven, Palm Oil: The Grease of Empire

68 notes

·

View notes