#in the same way christmas is not a christian festival it is a western festival

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Actual workplace conversation:

Catholic Workplace Acquaintance: Why would any non-Catholics celebrate Christmas?! It's the celebration of Jesus' birth!"

[Being who I am, I regarded this as a sincere question and attempted to answer it. The protestants present listened with curiosity, so I kept going]

Me: Well, first, Christmas wasn't always about Jesus. Solstice, Yule, and Saturnalia all pre-date the celebration of Jesus' birth as a winter holiday. Festivals in the West developed to take place in the darkest, coldest part of winter, using community to ward off the physical and emotional cold.

When Catholics conquered places in the West, they'd take a sacred building and slap a cross on it, saying "There! Now it's a cathedral!"

They did the same thing with western winter festivals. They appropriated them and said they were now about Jesus' birthday. December 25th was the date of the winter solstice in the Roman calendar.

Not even Catholic scholars claim Jesus was born on December 25th.

This was just a way to appropriate a local pagan holiday for Catholic purposes.

Catholic Workplace Acquaintance: But NOW it's about Jesus' birthday! Why would non-Catholics celebrate it?

Me: Okay, first we'll set aside the millions of Christians who are not Catholic, including Orthodox Christians, Anglicans, and a wide variety of protestants, and save for later that you're casually invalidating their faith because it's not your approved flavor of Christianity:

About 70% of Americans call themselves Christians and only about 20% of those are Catholics. I get that your world is Catholic. But the greater world is about 70% non-Christian and Catholics make up only about half of the world's Christians. But let's set aside your view that non-Catholic Christians aren't real Christians for later because I think what you really want to know is why people who do not worship Jesus as a god would celebrate Christmas.

[At this point, the protestants present were sort of enjoying this]

For a lot of Christians, sure, the winter holiday season is presently about celebrating the birth of Jesus. For others, it has remained/reverted more like a Solstice or Yule celebration. At a time of the year which is cold and dark, they come together with family and friends to create their own warmth and light. Family, friends, food, music, merriment, gift-giving, charity, generousity...none of these things require a metaphysical position or a belief in the divinity of Jesus or the day on which no Christian scholar believes Jesus was born.

Catholic Workplace Acquaintance: But...it's ABOUT Jesus' birth...

Me: For many throughout the world, it just isn't. Jesus wasn't born in December, Jesus factually isn't the "reason for the season" and never was except when Catholics appropriated the holidays of others- so celebrating the holiday as something other than a celebration of Jesus' birth shouldn't bother even the most devout Catholic...who can continue to celebrate their savior's birth as best suits them and their family as their traditions, beliefs, and and preferences dictate.

Christians who make the complaint that Christmas requires Christ are simply noticing that the holiday their ancestors appropriated is continually being taken back. They don't have to like it, but complaining about how others celebrate or claiming that Catholics should have a lock on it because they stole it fair and square seems parochial, tribalistic, ahistoric, and silly.

[Now the protestants in the room were chuckling, but my Catholic Workplace Acquaintance seemed to take great offense]

Catholic Workplace Acquaintance: All I hear is a sound like the teacher on Peanuts. BWAH-BWAH-BWAHA-MWAHA."

[...and she started to flounce away]

Me: ...Wow. Okay...well...Merry Christmas. And that's from a Jewish atheist.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yule

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia

#War on Christmas#Christmas#Catholics#Protestants#Pagans#Western religion#Christian appropriation of pagan symbols#Yule#Saturnalia#History of Christmas#Christian History#winter solstice

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's not the date that counts but the significance of Christmas that actually matters!

By Stanley Collymore So President Maduro of Venezuela purportedly wants to essentially move Christmas day crucially from December the 25th to October the 1st; so what's actually wrong with that? It's now rather undeniably, the month of September and already actually along with Halloween there are literally unquestionably plenty of Christmas items obviously on display and similarly specifically for sale in numerous shops quite evidently, around the country generally. Progressively a state of affairs that irrefutably, has arisen over the years and which discernibly self-evidently now, has even started in the month of August. Moreover, Christmas day as obviously represented in western countries is rather essentially a farce, as the 25th December its evidently designated occasion was clearly a major and quite longstandingly European pagan day of uprorious celebrations and so in order to actually, and significantly get these people to discernibly, literally convert to Christianity the minority purveyors effectively of this new religion called Christianity, basically rather logically and sensibly, therefore, appreciating this obvious state of affairs actually instinctively and equally intelligently decided that the best way to simply fully achieve their rather discernibly and specifically, distinctly evidently designated task of true conversion quite relative to these pagans, was to openly, and publicly, incorporate their undeniably, specifically major day of crucial, festive celebrations decisively and wholeheartedly too into this obviously thoroughly new for them naturally alien religion of Christianity which these Christian advocates were very avidly but all the same with basically expected difficulties obviously proseltysing. So cleverly and similarly subtly making this quite important day of December the 25th, a rather focal point of Christianity and equally also the birth date of the new and perspective Messiah discernibly of these manifestly expectantly new converts to Christianity, who simply otherwise, were essentially pagans unquestionably, entirely skeptically and basically reluctant to embrace Christianity were craftily won over! So good on you President Maduro! (C) Stanley V. Collymore 5 September 2024. Author's Remarks: Anyway, for the vast majority of westerners in this world who, most hypocritically, designate themselves as Christians but rather obviously never or have they ever entered any Christian building for worship, either of the established or free church Christian denominations, from one Sunday to the next, to then asininely and evidently pathetically as well as patronizingly voice their ludicrous and discernibly bigoted assumptions on something they simply don't practice and frankly know bugger all about is truly, actually rabid nonsense, that should be summarily discarded and really distinctively treated with the utter contempt it deserves! And besides all this white western European instituted stuff about Jesus Christ, his birth date, which reputable scientists and equally also astrologers actually categoricallly state wasn't anytime in the month designated as December is unquestionably an irrelevance; since what actually and discernibly, crucially and distinctly matters and quite specifically obviously outside the ostentatious and very pretentious proseltysing regarding the faith characterized as Christianity by those who self-evidently don't practise what they often preach, are the actual precepts and fittingly also the undoubtedly, genuine concepts of Christianity, and rather essentially, how all those of us who are effectively practising Christians permit our lives to be distinctly beneficially influenced by our faith. Amen!

0 notes

Text

THE DESCRIPTION OF POPE SAINT JULIUS I Feast Day: April 12

Julius I is remembered for setting 25 December as the official date of birth of Jesus Christ, starting the tradition of celebrating Christmas on that date.

He also asserted his authority against Arianism, a heretical cult that insisted Christ was human and not divine.

Julius was born in Rome but the exact date of his birth is not known. He became pope in 337 AD, four months after his predecessor, Pope Mark, had died.

In 339 Julius gave refuge in Rome to Bishop St Athanasius the Great of Alexandria, who had been deposed and expelled by the Arians.

At the Council of Rome in 340, Julius reaffirmed the position of Athanasius.

He then tried to unite the Western bishops against Arianism with the Council of Sardica in 342. The council acknowledged the Pope’s supreme authority, enhancing his power in ecclesiastical affairs by granting him the right to judge cases of legal possession of Episcopal sees.

Julius restored Athanasius and his decision was confirmed by the Roman emperor Constantius II, even though he himself was an Arian.

During the years of his papacy, Julius built several basilicas and churches in Rome.

Although the exact date of birth of Jesus has never been known, Julius decreed 25 December to be the official date for the celebration. This was near the Roman festival of Saturnalia, held in honour of the god Saturn from 17 to 23 December. Part of the reason he chose this date may have been because he wanted to create a Christian alternative to Saturnalia.

Another reason may have been that the emperor Aurelian had declared 25 December the birthday of Sol Invictus, the sun god and patron of Roman soldiers. Julius may have thought that he could attract more converts to Christianity by allowing them to continue to hold celebrations on the same day.

Julius died in Rome on 12 April 352 and was succeeded by Pope Liberius.

He was buried initially in the catacombs on the Aurelian Way but his body was later transported for burial to Santa Maria in Trastevere, one of the churches he had ordered to be completed during his papacy.

Source: italyonthisday.com

0 notes

Text

In the 1950s and ’60s, women baked cakes in the abandoned ammunition boxes left behind by British troops in the villages of Nagaland, a state in northeast India. The Naga writer Easterine Kire recalls how wives of Christian missionaries taught English and cake-baking to young girls, including her mother. While they didn’t really pick up the language, the tradition of baking cakes was passed down “from mother to daughter and from daughter to granddaughter.” It was the men who thought to repurpose the boxes — they were airtight, preserved heat well and fit perfectly over the wood fire. Since they had no temperature controls, the baker had to sit by the fire, constantly stoking it and eventually reducing it to embers. The timing had to be perfect: A minute too soon or too late could alter the fate of the cake. The boxes eventually ended up becoming part of a family’s heirloom until electric ovens became commonplace.

In the opposite corner of India, in Kerala in the deep south, several bakeries trace their history to the Mambally Royal Biscuit Factory in Thalassery, established in the late 19th century. Its founder, Mambally Bapu, is said to have baked India’s first Christmas cake. Bapu had trained as a baker in Burma (now Myanmar) to make cookies, bread and buns. When he set up shop in 1880, he made 140 varieties of biscuits. Three years later, the Scotsman Murdoch Brown, an East India Company spice planter, shared a sample of an imported Christmas plum pudding. Wanting to re-create this traditional recipe but unable to source French brandy, Bapu improvised with a local brew made from fermented cashew apples and bananas. He added some cocoa and — voila — the Indian Christmas cake was born.

The beauty of the Indian Christmas cake lies in its local variations. The Allahabadi version from north India features petha (candied ash gourd or white pumpkin) and ghee instead of butter, along with a generous helping of orange marmalade. Maharashtrians, in west India, add chironji, also known as cuddapah almonds. The black cake in Goa derives its color from a dark caramel sauce. In the south, in Kerala and Tamil Nadu, cashew nuts are added to the mix. The Indian version is “a close cousin” of British plum pudding, but it has no lard and is not steamed. “Indian Christians add a generous dose of hot spices such as nutmeg, cinnamon, cloves and shahi zeera (royal cumin seeds), roasted dry and then ground and added, also referred to as ‘cake masala,’” writes Jaya Bhattacharji Rose, an Indian publishing consultant, in “Indian Christmas,” an anthology of personal essays, poems, hymns and recipes.

“Our Christmas cakes reflect how India celebrates Christmas: with its own regional flair, its own flavor. Some elements are the same almost everywhere; others differ widely. What binds them together is that they are all, in their way, a celebration of the most exuberant festival in the Christian calendar,” writes Madhulika Liddle, co-editor of the anthology. Reading the book feels like a celebration in itself and makes one realize that Christians in India are as diverse as India, with Syrian Christians, Catholics, Baptists, Anglicans, Methodists, Lutherans and others. Though Christians make up just 2% of India’s population, this equates to some 28 million people.

Christianity came to India in waves. It is believed that Thomas the Apostle arrived in present-day Kerala in 52 BCE and built the first church. Syrian Christians believe he died in what is now Chennai in Tamil Nadu. San Thome Basilica stands where some of his remains were buried. Toward the end of the 15th century, the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama landed on Indian shores, followed by others, paving the way for Portuguese colonies in the region. Christian missionaries, who set up Western educational institutes, spread the religion further. The trend continued under the British Empire.

What is unique about India is the “indigenization of Christmas,” notes Liddle. It can be seen in the regional dishes prepared for Christmas feasts and celebrations. Duck curry with appams (rice pancakes) is popular in Kerala, while Nagaland prefers pork curries, rich with chilies and bamboo shoots. In Goa, dishes with Portuguese origins, such as sausage pulao, sorpotel and xacuti, adorn the tables. Biryanis, curries and shami kababs are devoured across north India.

The same regional diversity can be seen in Christmas snacks. “East Indians,” a Christian community in Mumbai described as such for their close ties to the East India Company, fill their plates with milk creams, mawa-filled karanjis (pastry puffs filled with dried whole milk), walnut fudge, guava cheese and kulkuls (sweet fried dough curls). In Goa, a platter of confectioneries called kuswar is served, including kormolas, gons, doce and bolinhas, made with ingredients ranging from coconut to Bengal gram, a yellow lentil. In Kerala, rose cookies are popular. Common across north Indian Christian households are shakkarpara, a sweet fried dough, covered in syrup; namakpara, a savory fried dough studded with cumin seeds; gujiyas, crisp pastries with a sweetened mix of semolina, raisins and nuts; and baajre ki tikiyas, thin patties made from pearl millet flour sweetened with jaggery, an unrefined sugar.

Liddle, who used to spend the festival at her ancestral home in the north Indian town of Saharanpur, also tells us about a lesser-known variation of the Christmas cake: cake ki roti. (In Hindi, “roti” means “flatbread.”) Like most communities in India, many Christian families in north India buy the ingredients for the Christmas cake themselves and take them to a baker who will prepare it. Bakers used to make the Christmas cake by the quintal (220 pounds) or more, and cake ki roti was a byproduct of that large-scale baking. The leftover Christmas cake batter was “not enough for an entire tin, not so little that it can be thrown away,” Liddle explained. So the baker would add flour and make a dough out of it. “It would be shaped into a large, flat disc and baked till it was golden and biscuity,” she said. The resulting cake ki roti may have “stray bits of orange peel or candied fruit, a tiny piece of nut here or there, a faint whiff of the spices … It was not even the ghost of the cake. A mere memory, a hint of Christmas cake.” Since cake ki roti was considered “too pedestrian,” it wasn’t served to the guests. Instead, it would be reserved until the New Year and eaten only after all the other snacks were gone.

Jerry Pinto, co-editor and contributor to “Indian Christmas,” recalled his childhood Christmases in Mumbai. There may not have been much snow in this tropical city, but wintry scenes of London and New York adorned festive cards and storybooks, and children would decorate the casuarina tree with cotton balls, assuming it to be pine. The mood would be set with an old Jim Reeves album featuring “White Christmas.” “Where do old songs from the U.S. go to die? They go to Goan Roman Catholic homes and parties,” quipped Pinto. Raisins would be soaked in rum in October, and cakes baked at an Iranian bakery. Every year, there was a debate about whether marzipan should be made with or without almond skins. The “good stuff” meant milk creams and cake slices with luscious raisins, while rose cookies and the neoris (sweet dumplings made of maida or flour and stuffed with coconut, sugar, poppy seeds, cardamom and almonds) were just plate-fillers.

The feasting is accompanied by midnight mass, communal decorations and choral music, with carols sung in Punjabi, Tamil, Hindi, Munda, Khariya, Mizo tawng, as well as English. “One of our favorite carols was a Punjabi one, which we always sang with great gusto: ‘Ajj apna roop vataake / Aaya Eesa yaar saade paas’ [‘Today, having changed His form / Jesus comes to us, friend’],” Liddle remembered.

Starting as early as October, it would not be unusual to hear Christmas classics by Boney M., ABBA and Reeves in Nagaland’s Khyoubu village. “The post-harvest life of the villagers is usually a restful period, mostly spent in a recreational mood until the next cycle of agricultural activities begins in the new year,” wrote Veio Pou, who grew up in Nagaland.

“Christmas is a time when invitations are not needed. Friends can land … at each other’s homes any time on Christmas Eve to celebrate. … The nightly silence is broken, and the air rings with Christmas carols and soul, jazz and rock music. Nearly every fourth person in Shillong plays the guitar, so there’s always music, and since nearly everyone sings, it’s also a time to sing along, laugh and be merry,” wrote Patricia Mukhim, editor of Shillong Times, a local newspaper in the northeastern state of Meghalaya.

Neighborhoods in areas with Christian populations, like Goa and Kerala, are lit up weeks in advance with fairy lights, paper lanterns and Christmas stars. In Mizoram’s capital of Aizawl, local authorities hold a competition every Christmas for the best-decorated neighborhood, with a generous prize of 500,000 rupees ($6,000) awarded to the winner. This event is gradually becoming a tourist attraction.

Rural India has its own norms and traditions. In the villages of the Chhota Nagpur region, mango leaves, marigolds and paper streamers decorate homes, and locally available sal or mango trees are decorated instead of the traditional evergreen conifer. The editor Elizabeth Kuruvilla recalled that her mother had stars made of bamboo at her childhood home in Edathua, a village in Kerala’s Alappuzha district. The renowned Goan writer Damodar Mauzo, who grew up in a Hindu household, said his family participates in many aspects of the Christmas celebrations in the village, including hanging a star in the “balcao” (“balcony”), making a crib and attending midnight mass.

In the Anglo-Indian enclave of Bow Barracks in Kolkata, Santa Claus comes to the Christmas street party in a rickshaw — the common form of public transport in South Asia. “Kolkata’s Bengali and non-Bengali revelers now throng the street, lined by two rows of red-brick terrace apartment buildings, to witness the music and dance and to buy the home-brewed sweet wine and Christmas cake that some of the Anglo-Indian families residing there make,” wrote the journalist Nazes Afroz. Bow Barracks was built to house the Allied forces stationed in Kolkata during World War I, after which they were rented out to the city’s Christian families.

Kolkata also is home to a tiny community of about 100 Armenian Christians, who celebrate Christmas on Jan. 6, in line with the Armenian Apostolic Church. Many break their weeklong fast at the Christmas Eve dinner, known as “Khetum.” The celebration begins with an afternoon mass on Christmas Eve followed by a home blessing ceremony to protect people from misfortune, held at the Armenian College and Philanthropic Society, an important institution for the community. The Khetum arranged for the staff members and students includes a customary pilaf with raisins and fish and anoush abour, an Armenian Christmas pudding made with wheat, berries and dried apricots, among other dishes. The Christmas lunch also includes traditional Armenian dishes such as dolma (ground meat and spices stuffed into grape leaves) and harissa, a porridge-like stew made with chicken, served with a garnish of butter and sprinkled ground cumin.

“Missionaries to Indian shores, whether St. Thomas or later evangelists from Portugal, France, Britain or wherever, brought us the religion; we adopted the faith but reserved for ourselves the right to decide how we’d celebrate its festivals,” Liddle wrote. “We translated the Bible into our languages. We translated their hymns and composed many of our own. We built churches which we at times decorated in our own much-loved ways.”

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's pretty wild. The thing I hate the most about how people keep using the term "cultural Christianity" as a way of accusing ex-Christians and athiests of still being "fundamentally Christian" in some form is that cultural Christianity is a really useful term in some contexts and then it just gets used for identity politics.

I'm an ex-Christian but I'm also part Chinese and grew up celebrating the major Chinese holidays (lunar new year, mid-autumn festival). Living in a country with a culturally Christian background meant that the Christian holidays we celebrated (Christmas and Easter) got public holidays, but we had to awkwardly squeeze in time to celebrate Chinese holidays with the few relatives we have here on my mum's side.

Cultural Christianity is really useful as a term to talk about this kind of thing - how my Muslim friend had to skip school to celebrate Eid, how our school literature classes assumed basic levels of familiarity with Christian references that not everybody has, how being from a non-Christian religion or culture in a culturally Christian country CAN be othering. It's a useful term!

But then people use it for identity politics as if being from a Christian family or ethnic group makes you somehow irreparably tainted with... Christian cooties??? That make you unable to see other perspectives or something??? As if other religions and cultures don't also influence people's worldviews? As if Christianity itself isn't the religion of a really really diverse range of cultures? Like do you think Vlado from Bulgaria who was raised in the Orthodox church is gonna have the same cultural assumptions as Edith from Scotland?

I feel like the identity politics also doesn't hold up when you take into account that there are many countries that aren't culturally Christian? For example, if you live in a Muslim-majority country where it's the Islamic holidays that get public holidays and people are generally assumed to have familiarity with Islam, then if you're from a Muslim family you'd probably experience a similar cultural advantage in that country as someone from a Christian family might experience in the US or Australia.

All religions and cultures will have values and assumptions - that's not unique to Christianity? And just because you shouldn't assume that other religions have the same values and perceptions as Christianity doesn't mean that they're somehow completely above criticism, as if Christianity is some kind of unique evil as opposed to one religion among many that happened to be the religion of the nations that perpetrated wide-scale colonialism that's led to a global hierarchy (and while western colonialism was horrifying and has massive ongoing impacts, conquering other countries and committing atrocities isn't historically unique to Christian nations).

Maybe the real “cultural Christianity” was the unwavering hostility towards atheists and criticism of religion we made along the way

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey Lydia, not to start on Christmas Drama (tm) again but I'm confused and you're a religious studies major so you might be able to help me out. I'm seeing a lot of "Yule and Christmas happen at the same time THEREFORE Christmas stole the date from pagans" and I'm... Correlation isn't causation though, is it? Like. "The days are getting longer again so let's have a celebration of the light" is a thing in many different cultures, is it not? None of these discourse posts ever seems to talk abt it

I see that theory (disguised as fact) commonly circulated around Christmas time. One is that the date of Christmas is evidence that it was “originally” a pagan holiday, pointing to the date of either Yule (ġēol) or Saturnalia. The Yule thing is just flat out false; Christmas was celebrated a long time before Christianity reached the parts of Europe that celebrated Yule. The Saturnalia theory is probable in comparison to the Yule theory, though I find that theory to still be flimsy.

“The most loudly touted theory about the origins of the Christmas date(s) is that it was borrowed from pagan celebrations. The Romans had their mid-winter Saturnalia festival in late December; barbarian peoples of northern and western Europe kept holidays at similar times. To top it off, in 274 C.E., the Roman emperor Aurelian established a feast of the birth of Sol Invictus (the Unconquered Sun), on December 25. Christmas, the argument goes, is really a spin-off from these pagan solar festivals. According to this theory, early Christians deliberately chose these dates to encourage the spread of Christmas and Christianity throughout the Roman world: If Christmas looked like a pagan holiday, more pagans would be open to both the holiday and the God whose birth it celebrated.

Despite its popularity today, this theory of Christmas’s origins has its problems. It is not found in any ancient Christian writings, for one thing. Christian authors of the time do note a connection between the solstice and Jesus’ birth: The church father Ambrose (c. 339–397), for example, described Christ as the true sun, who outshone the fallen gods of the old order. But early Christian writers never hint at any recent calendrical engineering; they clearly don’t think the date was chosen by the church. Rather they see the coincidence as a providential sign, as natural proof that God had selected Jesus over the false pagan gods.

It’s not until the 12th century that we find the first suggestion that Jesus’ birth celebration was deliberately set at the time of pagan feasts. A marginal note on a manuscript of the writings of the Syriac biblical commentator Dionysius bar-Salibi states that in ancient times the Christmas holiday was actually shifted from January 6 to December 25 so that it fell on the same date as the pagan Sol Invictus holiday. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Bible scholars spurred on by the new study of comparative religions latched on to this idea. They claimed that because the early Christians didn’t know when Jesus was born, they simply assimilated the pagan solstice festival for their own purposes, claiming it as the time of the Messiah’s birth and celebrating it accordingly.”

(x)

It is far more likely that Christmas was a result of the dating of the Annunciation rather than any pagan holiday. In early Christianity, it was assumed the Jesus was conceived around the same time he died. The Annunciation takes place exactly nine months before Christmas.

Thus, we have Christians in two parts of the world calculating Jesus’ birth on the basis that his death and conception took place on the same day (March 25 or April 6) and coming up with two close but different results (December 25 and January 6)

Connecting Jesus’ conception and death in this way will certainly seem odd to modern readers, but it reflects ancient and medieval understandings of the whole of salvation being bound up together. One of the most poignant expressions of this belief is found in Christian art. In numerous paintings of the angel’s Annunciation to Mary—the moment of Jesus’ conception—the baby Jesus is shown gliding down from heaven on or with a small cross (see photo above of detail from Master Bertram’s Annunciation scene); a visual reminder that the conception brings the promise of salvation through Jesus’ death.

(x)

I find the theory that Christmas was created purposefully 9 months after the Annunciation of Mary (March 25) to be far more convincing.

There likely was a transference of traditions from “paganism” to Christianity when the diverse populations in Europe gradually converted to Christianity. Maybe there were some Yule or Saturnalia traditions that became a part of the Christmas celebrations. I wouldn’t doubt it at all. It seems incredibly likely. However, these traditions wouldn’t have been stolen; you can’t “steal” traditions that are from your own people. It’s called syncretization and it is a common occurrence when a population converts to a new religion.

Secondly, we really don’t really know if our traditions today could even have “pagan” origins. I’d argue that the vast majority of Christmas traditions originate within the last half millennia, and are too young to grow from pre-Christianized Europe. This is especially the case in America, where I would argue that Christmas traditions are almost a direct result of the capitalist and consumerist culture that has permeated our society for the last few centuries. I mean there could be some traditions that stretch back to pre-Christian Europe, however, they would have evolved so much that it would probably be unrecognizable to the pre-Christian peoples from which they came.

Again, everything about the “origins” of Christmas and its traditions is theory, not fact. And I recommend being suspicious of absolutist claims.

320 notes

·

View notes

Text

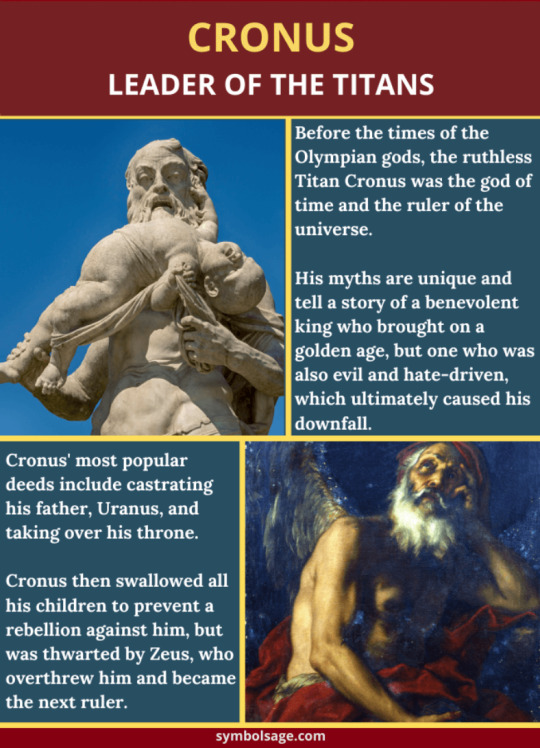

Cronus (Kronos) – Leader of the Titans

Before the times of the Olympians, the ruthless Titan Cronus (also spelled Kronos or Cronos) was the god of time and the ruler of the universe. Cronus is known as a tyrant, but his dominion in the Golden Age of Greek mythology was prosperous. Cronus is typically depicted as a strong, tall man with a sickle, but sometimes he’s portrayed as an old man with a long beard. Hesiod refers to Cronus as the most terrible of the Titans. Here’s a closer look at Cronus.

Cronus and Uranus

According to Greek mythology, Cronus was the youngest of the twelve Titans born from Gaia, the personification of earth, and Uranus, the personification of the sky. He was also the primordial god of time. His name comes from the Greek word for chronological or sequential time, Chronos, from which we get our modern words like chronology, chronometer, anachronism, chronicle and synchrony to name a few.

Before Cronus was the ruler, his father Uranus was the ruler of the universe. He was irrational, evil and had forced Gaia to keep his children the Titans, the Cyclopes and Hecatoncheires in her womb, because he despised them and didn’t want them to see the light. However, Gaia managed to conspire with Cronus to take down Uranus and end his reign over the universe. According to the myths, Cronus used a sickle to castrate Uranus, thus separating the skies from the earth. The Erinyes were born from the blood of Uranus that fell onto Gaia, while Aphrodite was born from the white foam of the sea when Cronus tossed the severed genitals of Uranus into the sea.

When Uranus was unmanned, he cursed his son with a prophecy that said that he would suffer the same destiny as his father; Cronus would be dethroned by one of his sons. Cronus then went on to free his siblings and ruled over the Titans as their king.

The myths say that as a result of Uranus’ dethroning, Cronus separated the heavens from the earth, creating the world as we know it nowadays.

Cronus and the Golden Age

In current times, Cronus is seen as an unmerciful being, but the tales of the pre-Hellenistic Golden Age tell a different story.

Cronus’ reign was a plentiful one. Although humans already existed, they were primitive beings who lived in tribes. Peace and harmony were the foremost markers of the rule of Cronus in a time where there was no society, no art, no government, and no wars.

Due to this, there are tales of Cronus’ benevolence and the limitless abundance of his times. The golden age is known as the greatest of all human eras, where gods walked on earth among men, and life was teeming and peaceful.

After the Hellenes arrived and imposed their traditions and mythology, Cronus began to be depicted as a destructive force that ravaged everything on his way. The Titans were the first enemies of the Olympians, and this gave them their dominant role as the villains of Greek mythology.

Cronus’ Children

Cronus wed his sister Rhea, and together they ruled the world after Uranus’ demise. They sired six children: Hestia, Demeter, Hera, Hades, Poseidon, and Zeus in that order.

Unexpectedly, and after a period of calm and excellent ruling, Cronus started acting like Uranus, and conscious of his father’s prophecy, he swallowed all his children as soon as they were born. That way, none of them could dethrone him.

However, Rhea would not have this. With her mother Gaia’s help, she managed to hide the last child, Zeus, and gave Cronus a rock wrapped in clothes to eat instead. Zeus would grow to be the one to fulfill Uranus’ prophecy.

The Dethroning of Cronus

Zeus eventually challenged his father, managing to save his siblings by making Cronus disgorge them, and together they fought Cronus for the rule of the cosmos. After a mighty fight that struck both heaven and earth, the Olympians rose victorious, and Cronus lost his power.

After being dethroned, Cronus did not die. He was sent to the Tartarus, a deep abyss of torment, to remain there imprisoned as a powerless being with the other Titans. In other accounts, Cronus was not sent to the Tartarus but instead stayed as king in Elysium, the paradise for immortal heroes.

Cronus could not break the cycle of sons dethroning fathers in Greek mythology. According to Aeschylus, he passed on his curse to Zeus with the prophecy that he would suffer the same fate.

Cronus’ Influence and Other Associations

Cronus’ myths have given him a variety of associations. Given the abundance of his rule in the Golden Age, Cronus was also the god of harvest and prosperity. Some myths refer to Cronus as Father Time.

Cronus has been associated with the Phoenician god of time, El Olam, for the child sacrifices that people offered to both of them in antiquity.

According to Roman tradition, Cronus’ counterpart in Roman mythology was the agricultural god Saturn. Roman stories propose that Saturn reinstated the golden age after he escaped the Latium – the celebration of this time was Saturnalia, one of Rome’s most important traditions.

The Saturnalia was a festival celebrated yearly from December 17th to December 23rd. Christianity later adopted many of the customs of Saturnalia, including giving gifts, lighting candles and feasting. The influence of this agricultural festival still impacts the western world and the way we celebrate Christmas and the New Year.

Cronus in Modern Times

After the rise to power of the Olympians, the benevolence and the generosity of Cronus were left aside, and his role as the antagonist was the prevalent idea people had of the titan. This association continues today.

In Rick Riordan’s saga Percy Jackson and the Olympians, Cronus tries to return from Tartarus to declare war once again to the gods with the help of a group of demigods.

In the series Sailor Moon, Sailor Saturn has the powers of Cronus/Saturn and his connection to the harvests.

Father Time appears in the videogame series God of War with some modifications to his Greek Mythology story.

Wrapping Up

Although he is seen as one the greatest antagonists of Greek mythology, the King of the Titans may not have been that bad after all. With the most prosperous times in human history ascribed to his reign, Cronus seems to have been a benevolent ruler at one stage in time. His role as the usurper of power against Uranus and later as the antagonist against whom Zeus fought makes him one of the most important characters of Greek mythology.

https://symbolsage.com/cronus-leader-of-titans/

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Creatures of Yuletide: Krampus, the Christmas Demon

He sees you when you're sleeping

And he knows when you're awake

He knows if you've been bad or good

So be good FOR YOUR OWN GODDAMNIT SAKE!!!

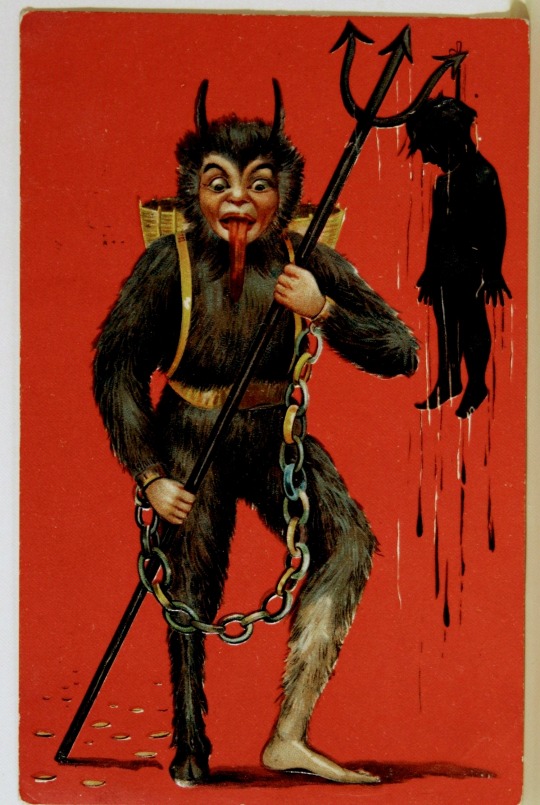

Christmas season is full of magical beings and creatures that travel through our world. Jolly old men from the north, elves that sleep in our homes, goats that give presents, the holiday season is full of all sorts of weird and wonderful characters. However, Santa Claus tends to me the most famous among them, and the most remembered in popular culture. This was, until some years ago, when a forgotten Christmas character rose in popularity in pop culture as an antithesis of good old St. Nick. I’m talking about Krampus, the Christmas Demon from German and Alpine lore.

One of the reasons why I believe Krampus became so popular recently is because he’s a scarier and less commercial alternative to Santa. In older posts I talked about how people used to tell scary ghost stories during Christmas and how Christmas once had this spooky side to it. Then one day it hit me that, in a way, Krampus is exactly a call back to these traditions. While not a ghost, Krampus brings back the scary atmosphere to the holiday. People tell stories about Krampus, they dress like him, they fright their neighbors in these costumes. People in general like to be scared, and in particular, even though they won’t admit it now, children too. Krampus is celebrated because he brings back the fun that overly commercialized Santa took out from Christmas.

Jeremy Seghers, organizer of the first Krampusnacht festival held in Orlando, said this in an interview to the Smithsonian Magazine:

"The Krampus is the yin to St. Nick's yang. You have the saint, you have the devil. It taps into a subconscious macabre desire that a lot of people have that is the opposite of the saccharine Christmas a lot of us grew up with."

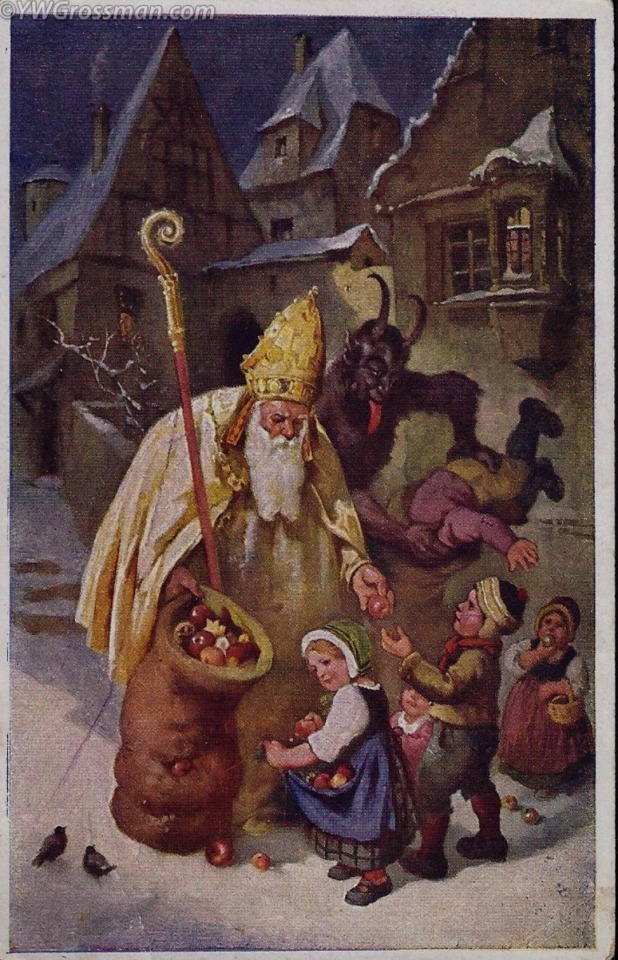

Krampus is mainly a holiday tradition from the Alpine region and Central Europe in general. His name is derives from the German word krampen, meaning claw. On the night of December 5th, the eve of Saint Nicholas Feast, Krampus, and Saint Nicholas himself go out in the streets to punish or reward kids. This makes him one of the Companions of Saint Nicholas, a group of holiday figures that would help him in punishing kids. While they do the punishment, jolly old Nick brings the kids gifts, in a sort of Good Cop, Bad Cop dynamic.

Our friend St. Nick fills the shoes of good children with fruits and sweets. Krampus carries birch branches for senseless beating the misbehaving ones. On his back he is often depicted carrying a sack or a basket. This is to carry the naughty kids to his layer for more torture later. He can also eat them, threw them out in the river to drown, or bring them straight to the depths of Hell. In some parts of Austria, Krampus presents the families with gold-painted twigs that are to be displayed year-round in the house, constantly reminding the kids of his ever-watching presence.

What lovable fellow!

It was common in the 19th century to exchange Gruß vom Krampus, “Greetings from Krampus” cards that contained humorous rhymes and poems. In these Krampus is depicted looming menacingly over children. In others the creature receives sexual undertones, pursuing scantily dressed women.

There is also the Krampuslauf, or, Krampus Run, where people dress up as him and parade through the street dressed in fur suits and carved wooden masks and carrying cowbells. This one is very important for understanding Krampus origins.

Now, no one really know where Krampus comes from. The most popular theory is that he was a fertility god from the Alpine Region before Christianity retconned him as demon. Scholars often link him, Pan, and the satyrs to the archetype of the Horned God. Some claim he’s the son of Hel, but I didn’t find any real or credible source to this.

What we do know is that Krampus has some connections to a goddess in the Alpine region called Frau Perchta.

Now Frau Perchta is a very mysterious figure from the German folklore. She had many different names depending on the era and region. We don’t know a lot about her before Christianization, but what we do know is that in the folklore of Bavaria and Austria, she was a witch said to roam the countryside at midwinter, and to enter homes during the twelve days between Christmas and Epiphany. Good children would find a silver coin in their shoes. Bad children would have their bellies sliced open, their stomach and guts removed, and she would stuff the straw and pebbles in the hole left behind. She had two forms in which she could be encountered, beautiful and white as snow, or elderly and haggard.

Perchten is plural for Perchta. Originally, the word referred to female masks representing her, but the name come to refer to the animal masks worn in parades and festivals in the mountainous regions of Austria.

A Perchten mask

In the 16th century, the Perchten took two main forms: Schönperchten, "beautiful Perchten", or the Schiachperchten, "ugly Perchten”. The beautiful Perchten came during the twelve nights of Christmas and festivals to bring luck and wealth to the people. The ugly Perchten, who had fangs, tusks and horse tails which were used to drive out demons and ghosts. Men dressed as the ugly Perchten during this time and went from house to house driving out bad spirits.

From the Smithsonian Magazine: A man dressed in a traditional Perchten costume and mask performs during a Perchten festival in the western Austrian village of Kappl, November 13, 2015. Each year in November and January, people in the western Austria regions dress up in Perchten (also known in some regions as Krampus or Tuifl) costumes and parade through the streets to perform a 1,500 year-old pagan ritual to disperse the ghosts of winter. (DOMINIC EBENBICHLER/Reuters/Corbis)

People would masquerade as these devilish figures and march in processions known as Perchtenlaufs. The Church didn’t like these creatures and tried many times to ban these practices, but due to the sparse population and the rugged environments within the region, the ban was useless.

In Catholicism, St. Nicholas is the patron saint of children. His saint day falls in early December, which helped strengthen his association with the Yuletide season. A seasonal play that spread throughout the Alpine regions was known as the Nikolausspiel, "Nicholas play". In these plays St. Nick would make questions about morality and reward children for their scholarly efforts. Eventually the Perchtenlauf, in an attempt to pacify the Church, introduced Saint Nicholas and his set of good morals. Krampus, the in-chains helper of Saint Nicholas, was then born.

In 1975, anthropologist John J. Honigmann wrote that:

"The Saint Nicholas festival we are describing incorporates cultural elements widely distributed in Europe, in some cases going back to pre-Christian times. Nicholas himself became popular in Germany around the eleventh century. The feast dedicated to this patron of children is only one winter occasion in which children are the objects of special attention, others being Martinmas, the Feast of the Holy Innocents, and New Year's Day. Masked devils acting boisterously and making nuisances of themselves are known in Germany since at least the sixteenth century while animal masked devils combining dreadful-comic (schauriglustig) antics appeared in Medieval church plays. A large literature, much of it by European folklorists, bears on these subjects. ... Austrians in the community we studied are quite aware of "heathen" elements being blended with Christian elements in the Saint Nicholas customs and in other traditional winter ceremonies. They believe Krampus derives from a pagan supernatural who was assimilated to the Christian devil"

Is worth noting that this is exactly what happened to the Yule Goat. He was a pagan symbol, people dressed like him to keep winter spirits at bay, but the Christians demonized him. There are illustrations of Saint Nicholas or of Father Christmas riding the Yule Goat during Christmas and these were meant to represent the power of God over the power of the Devil. Krampus is represented in chains by the same reason. However, the Yule Goat came to become a gift-giver and a more positive force in holiday lore, with people dressing as goats to deliver gifts to their families in the 19th century. Krampus didn’t have the same luck. I really wonder if the Yule Goat and Krampus came from variants from the same or similar cultural traditions, but that took drastically different routes.

I must say that, although I'm more in the team Santa, I learned to love Krampus over the years. It’s undeniable the amount of fun he brought to those who wanted something a little more darker and creepier in the holidays, and as someone who identifies itself as 90% lover of cheesy, cutesy and sappy stuff and 10% lover of everything earie and macabre, the idea of a monstrous boogeyman in the shadows of good old Santa Claus is fun. I personally think there’s enough space for both, the terrifyingly scary and the joyful jolliness.

Fun fact: Krampus, the one people rescued from German obscurity to combat the overly commercialized Christmas, is now being criticized as being too commercialized. C'est la vie

Story time: In my country I once heard the tale of a guy that went as Santa to deliver Christmas presents to children in a poor community. He brought many gifts and toys with him. The children loved them, until there were no more gifts to be delivered. The remaining children and their parents became so angry that they chased away the guy, throwing rocks at him. The guy came to them with free stuff, helped as much as he could, and people still threw rocks at him and chased him away, almost seriously hurting him.

I admit, there are cases where Krampus is truly needed 🤣🤣🤣

Art by Helen Mask

#The Creatures of Yuletide#christmas#holiday season#gruss vom krampus#krampus#Greetings from Krampus#Gruß vom Krampus

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Twelfth night

So, on Tumblr and the twitters and elsewhere, many people observed Musical Advent, in which they posted music on particular themes that they were allowed to select for themselves this year. The only requirement seemed to be that you had to be consistent about the theme, whatever it was.

Now, these premises here don’t typically do Advent, and we never do Consistent, for heaven’s sake. What we do instead -- very occasionally -- is Twelfth Night. What is that, you might ask? Well, let us turn to that renowned source of accurate information, Wikipedia:

Twelfth Night (also known as Epiphany Eve) is a festival in some branches of Christianity that takes place on the last night of the Twelve Days of Christmas, marking the coming of the Epiphany. Different traditions mark the date of Twelfth Night as either 5 January or 6 January, depending on whether the counting begins on Christmas Day or 26 December.

In many Western ecclesiastical traditions, Christmas Day is considered the "First Day of Christmas" and the Twelve Days are 25 December – 5 January, inclusive, making Twelfth Night on 5 January, which is Epiphany Eve.

In some customs the Twelve Days of Christmas are counted from sundown on the evening of 25 December until the morning of 6 January, meaning that the Twelfth Night falls on the evening 5 January and the Twelfth Day falls on 6 January. However, in some church traditions only full days are counted, so that 5 January is counted as the Eleventh Day, 6 January as the Twelfth Day, and the evening of 6 January is counted as the Twelfth Night. In these traditions, Twelfth Night is the same as Epiphany. However, some such as the Church of England consider Twelfth Night to be the eve of the Twelfth Day (in the same way that Christmas Eve comes before Christmas), and thus consider Twelfth Night to be on 5 January The difficulty may come from the use of the words "eve" which is defined as "the day or evening before an event", however, especially in antiquated usage could be used to simply mean "evening"....

Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twelfth_Night_(holiday)

Eh. Good enough.

So, from the night of December 26 through the night of January 6, a different piece of music will land in these parts on every night. Sometimes it will be something that was previously posted, sometimes it’ll be something not seen here before. Sometimes there may be more than one! And it will post typically at 6pm or later.

And what will the theme be? ... Well, that would be telling. However, I trust it will be obvious. (Although adherence to theme will not be dogmatic. See note about “never Consistent, for heaven’s sake”, above.)

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Christmas Day

Christmas Day is a Christian holiday that celebrates the birth of Jesus Christ, and it is also celebrated as a non religious cultural holiday. It is a public holiday in many countries, and is celebrated in some countries where there is not a large Christian population. It takes place after Advent and the Nativity Fast, and begins Christmastide, or the Twelve Days of Christmas. The name of the holiday is shortened from “Christ’s mass,” and throughout history the day has been known as “midwinter,” “Nativity,” “Yule,” and “Noel.”

The New Testament gospels of Luke and Matthew describe Jesus as being born in Bethlehem, in Judea. Luke’s account tells of Joseph and Mary traveling to Bethlehem from Nazareth for a census, and Jesus being born in a stable and being laid in a manger. According to this account, angels proclaimed him as the savior, and shepherds came to visit him. Matthew’s account tells the story of the magi following a star in the sky and bringing Jesus gifts.

The month and date of Jesus’ birth is unknown, but the Western Christian Church placed it as December 25 by at least 336 CE, when the first Christmas celebration was recorded, in Rome. This date later became adopted by Eastern churches at the end of the fourth century. Some Eastern churches celebrate Christmas on December 25 of the Julian calendar, which is January 7. The date of December 25 may have been chosen for a few reasons. This is the day that the Romans marked as the winter solstice, the day when the Sun would begin remaining longer in the sky. Jesus also was sometimes identified with the Sun. The Romans had other pagan festivals during the end of the year as well. December 25 also may have been chosen because it is about nine months after the date commemorating the Crucifixion of Jesus.

Christmas celebrations were not prominent in the Early Middle Ages, and the holiday was overshadowed by Epiphany at the time. Christmas started to come to prominence after 800 CE, when Charlemagne was crowned emperor on Christmas Day. During the Middle Ages it became a holiday that incorporated evergreens, the giving of gifts between legal relationships—such as between landlords and tenants, eating, dancing, singing, and card playing. By the seventeenth century in England the day was celebrated with elaborate dinners and pageants.

Puritans saw the day as being connected to drunkenness and misbehavior, and banned it in the seventeenth century. But, Anglican and Catholic churches promoted it at the time. Following the Protestant Reformation, many new denominations continued celebrating Christmas, but some radical Protestant groups did not celebrate it. In Colonial America, Pilgrims were opposed to the holiday, and it wasn’t until the mid nineteenth century that the Boston area fully embraced the holiday. But, the holiday was freely practiced in Virginia and New York during colonial times. Following the Revolution it fell out of favor in the United States to some extent, as it was seen as being an English custom.

Around the world there was a revival of Christmas celebrations in the early nineteenth century, after it took on a more family oriented, and children centered theme. A contributing factor to this was Charles Dickens’ publication of A Christmas Carol in 1843. His novel highlighted themes of compassion, goodwill, and family. Seasonal food and drink, family gatherings, dancing, games, and a festive generosity of spirit all are part of Christmas celebrations today, and were part of Dickens’ novel. Even the phrase “Merry Christmas” became popularized by the story.

In the United States, several of Washington Irving’s short stories in the 1820s helped revive Christmas, as did A Visit From St. Nicholas. This poem helped to popularize the exchanging of gifts, and helped Christmas shopping take on an economic importance. It was after this that there began to be a conflict between the spiritual and commercial aspects of Christmas as well. By the 1850s and 1860s, the holiday became more widely celebrated in the United States, and Puritan resistance began to shift to acceptance. By 1860, fourteen states had adopted Christmas as a legal holiday. On June 28, 1870, it became a federal holiday in the United States.

Celebrations of Christmas in the United States and other countries are a mix of pre-Christian, Christian, and secular influences. Gift giving today is based on the tradition of Saint Nicholas, as well as on the giving of gifts by the magi to Jesus. Giving also may have been influenced by gift giving during the ancient Roman festival Saturnalia. Closely related and often interchangeable figures such as Santa Claus, Father Christmas, Saint Nicholas, and Christkind are seen as gift givers to children—the best known of which is Santa Claus. His name is traced back to the Dutch Sinterklaas, which simply meant Saint Nicholas. Saint Nicholas was a fourth century Greek bishop who was known for his care of children, generosity, and the giving of gifts to children on his feast day. During the Reformation, many protestants changed the gift giver to the Christ child, or Christkindl, which was changed to Kris Kringle in English. The date of giving changed from Saint Nicholas Day to Christmas Eve at this time. Modern Santa Claus started in the United States, particularly in New York; he first appeared in 1810. Cartoonist Thomas Nast began drawing pictures of him each year beginning in 1863, and by the 1880s Santa took on his modern form.

Attending Christmas services is popular for religious adherents of the holiday. Sometimes services are held right at midnight, at the beginning of Christmas Day. Readings from the gospels as well as reenactments of the Nativity of Jesus may be done.

Christmas cards are another important part of Christmas, and are exchanged between family and friends in the lead up to the day. The first commercial Christmas cards were printed in 1843—the same year as the printing of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. In 1875 the first commercial Christmas cards made their debut in the United States. Today both religious and secular artwork adorns the cards.

Music has long been a part of Christmas. The first Christmas hymns came about in fourth century Rome. By the thirteenth century, countries like France, Germany, and Italy had developed Christmas songs in their native language. Songs that became known as carols were originally communal folk songs, and were sung during celebrations such as “harvest tide” as well as Christmas, and began being sung in church. The singing of Christmas songs went into some decline during the Reformation. “Hark the Herald Angels Sing” came about in the eighteenth century, and “Silent Night” was composed in 1818. Christmas carols were revived with William Sandy’s Christmas Carols Ancient and Modern in 1833, which included some of the first appearances of “The First Noel,” “I Saw Three Ships,” “Hark the Herald Angels Sing,” and “God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen.” Secular Christmas songs began to come about in the late eighteenth century. “Deck the Halls” was written in 1784, and “Jingle Bells” was written in 1857. Many secular Christmas songs were produced in the 20th century, in jazz, blues, country, and rock and roll variations: Irving Berlin’s “White Christmas” was popularized by Bing Crosby; “Jingle Bell Rock” was sung by Bobby Helms; Brenda Lee did a version of “Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree;” “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” was recorded by Gene Autry. Elvis Presley also put out a Christmas album.

A special meal is often eaten on the day, and popular food varies from country to country. In United States, turkey with stuffing—sometimes called dressing—is often the main course, but roast beef or ham are also popular. Potatoes, squash, roasted vegetables, casseroles, and cranberry sauces are common. Popular drinks include tonics, sherries, and eggnog. Pastries, cookies, and other desserts sweeten the day, and fruits, nuts, chocolates, and cheeses are popular snacks.

Finally, Christmas decorations are an important aspect of the holiday and include things such as trees, lights, nativity scenes, garland, stockings, angels, wreaths, mistletoe, and holly. The Christmas tree tradition is believed to have started in Germany in the eighteenth century, although some believe Martin Luther began the tradition in the sixteenth century. Christmas trees were introduced to England in the early nineteenth century. In 1848 the British royal family photo showed the family with a Christmas tree, and it caused a sensation. A version of the photo was reprinted two years later in the United States. By the 1870s the putting up of trees was common in the United States. They are adorned with lights and ornaments, and can be real or artificial.

Christmas Day, also known as Christmas, is being observed today! It has always been observed annually on December 25th.

There are an innumerable amount of ways that you could celebrate Christmas:

attend a church service or read the gospel Christmas accounts

watch a Christmas film

listen to Christmas music

complete an Advent calendar or wreath

give gifts

view a Nativity play

watch a Christmas parade

visit family or friends

visit Santa Claus

read books such as How the Grinch Stole Christmas! or A Christmas Carol

light a Christingle

view Christmas decorations

go Christmas caroling

make Christmas cookies or other foods associated with the holiday

Source

#Christmas Day#ChristmasDay#25 December#it's snowing#Christmas Tree#Nativity scene#manger scene#Christmas Tree Topper#original photography#Schweiz#Switzerland#Xmas 2020#real tree and real beewax candles#homemade stuffed turkey#but not this year#Cabernet Sauvignon#Christmas Lights#Merry Christmas#Merry Xmas

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The history of Helloween Halloween- is a annual holiday celebrated each year on October It originated with the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain, when people would light bonfires and wear costumes to ward off ghosts. In the eighth century, Pope Gregory III designated November 1 as a time to honor all saints; soon, All Saints Day incorporated some of the traditions of Samhain. The evening before was known as All Hallows Eve, and later Halloween. Over time, Halloween evolved into a day of activities like trick-or-treating, carving jack-o-lanterns, festive gatherings, donning costumes and eating sweet treats. Ancient Origins of Halloween Halloween’s origins date back to the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain (pronounced sow-in). The Celts, who lived 2,000 years ago in the area that is now Ireland, the United Kingdom and northern France, celebrated their new year on November 1. This day marked the end of summer and the harvest and the beginning of the dark, cold winter, a time of year that was often associated with human death. Celts believed that on the night before the new year, the boundary between the worlds of the living and the dead became blurred. On the night of October 31 they celebrated Samhain, when it was believed that the ghosts of the dead returned to earth. In addition to causing trouble and damaging crops, Celts thought that the presence of the otherworldly spirits made it easier for the Druids, or Celtic priests, to make predictions about the future. For a people entirely dependent on the volatile natural world, these prophecies were an important source of comfort and direction during the long, dark winter. To commemorate the event, Druids built huge sacred bonfires, where the people gathered to burn crops and animals as sacrifices to the Celtic deities. During the celebration, the Celts wore costumes, typically consisting of animal heads and skins, and attempted to tell each other’s fortunes. When the celebration was over, they re-lit their hearth fires, which they had extinguished earlier that evening, from the sacred bonfire to help protect them during the coming winter. Did you know? One quarter of all the candy sold annually in the U.S. is purchased for Halloween. By 43 A.D., the Roman Empire had conquered the majority of Celtic territory. In the course of the four hundred years that they ruled the Celtic lands, two festivals of Roman origin were combined with the traditional Celtic celebration of Samhain. The first was Feralia, a day in late October when the Romans traditionally commemorated the passing of the dead. The second was a day to honor Pomona, the Roman goddess of fruit and trees. The symbol of Pomona is the apple, and the incorporation of this celebration into Samhain probably explains the tradition of “bobbing” for apples that is practiced today on Halloween. All Saints Day On May 13, 609 A.D., Pope Boniface IV dedicated the Pantheon in Rome in honor of all Christian martyrs, and the Catholic feast of All Martyrs Day was established in the Western church. Pope Gregory III later expanded the festival to include all saints as well as all martyrs, and moved the observance from May 13 to November 1. By the 9th century the influence of Christianity had spread into Celtic lands, where it gradually blended with and supplanted the older Celtic rites. In 1000 A.D., the church would make November 2 All Souls’ Day, a day to honor the dead. It’s widely believed today that the church was attempting to replace the Celtic festival of the dead with a related church-sanctioned holiday. All Souls Day was celebrated similarly to Samhain, with big bonfires, parades, and dressing up in costumes as saints, angels and devils. The All Saints Day celebration was also called All-hallows or All-hallowmas (from Middle English Alholowmessemeaning All Saints’ Day) and the night before it, the traditional night of Samhain in the Celtic religion, began to be called All-Hallows Eve and, eventually, Halloween. Halloween Comes to America Celebration of Halloween was extremely limited in colonial New England because of the rigid Protestant belief systems there. Halloween was much more common in Maryland and the southern colonies. As the beliefs and customs of different European ethnic groups as well as the American Indians meshed, a distinctly American version of Halloween began to emerge. The first celebrations included “play parties,” public events held to celebrate the harvest, where neighbors would share stories of the dead, tell each other’s fortunes, dance and sing. Colonial Halloween festivities also featured the telling of ghost stories and mischief-making of all kinds. By the middle of the nineteenth century, annual autumn festivities were common, but Halloween was not yet celebrated everywhere in the country. In the second half of the nineteenth century, America was flooded with new immigrants. These new immigrants, especially the millions of Irish fleeing the Irish Potato Famine, helped to popularize the celebration of Halloween nationally. Trick-or-Treat Borrowing from Irish and English traditions, Americans began to dress up in costumes and go house to house asking for food or money, a practice that eventually became today’s “trick-or-treat” tradition. Young women believed that on Halloween they could divine the name or appearance of their future husband by doing tricks with yarn, apple parings or mirrors. In the late 1800s, there was a move in America to mold Halloween into a holiday more about community and neighborly get-togethers than about ghosts, pranks and witchcraft. At the turn of the century, Halloween parties for both children and adults became the most common way to celebrate the day. Parties focused on games, foods of the season and festive costumes. Parents were encouraged by newspapers and community leaders to take anything “frightening” or “grotesque” out of Halloween celebrations. Because of these efforts, Halloween lost most of its superstitious and religious overtones by the beginning of the twentieth century Halloween Parties By the 1920s and 1930s, Halloween had become a secular, but community-centered holiday, with parades and town-wide Halloween parties as the featured entertainment. Despite the best efforts of many schools and communities, vandalism began to plague some celebrations in many communities during this time. By the 1950s, town leaders had successfully limited vandalism and Halloween had evolved into a holiday directed mainly at the young. Due to the high numbers of young children during the fifties baby boom, parties moved from town civic centers into the classroom or home, where they could be more easily accommodated. Between 1920 and 1950, the centuries-old practice of trick-or-treating was also revived. Trick-or-treating was a relatively inexpensive way for an entire community to share the Halloween celebration. In theory, families could also prevent tricks being played on them by providing the neighborhood children with small treats. Thus, a new American tradition was born, and it has continued to grow. Today, Americans spend an estimated $6 billion annually on Halloween, making it the country’s second largest commercial holiday after Christmas. Soul Cakes The American Halloween tradition of “trick-or-treating” probably dates back to the early All Souls’ Day parades in England. During the festivities, poor citizens would beg for food and families would give them pastries called “soul cakes” in return for their promise to pray for the family’s dead relatives. The distribution of soul cakes was encouraged by the church as a way to replace the ancient practice of leaving food and wine for roaming spirits. The practice, which was referred to as “going a-souling” was eventually taken up by children who would visit the houses in their neighborhood and be given ale, food and money. The tradition of dressing in costume for Halloween has both European and Celtic roots. Hundreds of years ago, winter was an uncertain and frightening time. Food supplies often ran low and, for the many people afraid of the dark, the short days of winter were full of constant worry. On Halloween, when it was believed that ghosts came back to the earthly world, people thought that they would encounter ghosts if they left their homes. To avoid being recognized by these ghosts, people would wear masks when they left their homes after dark so that the ghosts would mistake them for fellow spirits. On Halloween, to keep ghosts away from their houses, people would place bowls of food outside their homes to appease the ghosts and prevent them from attempting to enter. Black Cats Halloween has always been a holiday filled with mystery, magic and superstition. It began as a Celtic end-of-summer festival during which people felt especially close to deceased relatives and friends. For these friendly spirits, they set places at the dinner table, left treats on doorsteps and along the side of the road and lit candles to help loved ones find their way back to the spirit world. Today’s Halloween ghosts are often depicted as more fearsome and malevolent, and our customs and superstitions are scarier too. We avoid crossing paths with black cats, afraid that they might bring us bad luck. This idea has its roots in the Middle Ages, when many people believed that witches avoided detection by turning themselves into black cats. We try not to walk under ladders for the same reason. This superstition may have come from the ancient Egyptians, who believed that triangles were sacred (it also may have something to do with the fact that walking under a leaning ladder tends to be fairly unsafe). And around Halloween, especially, we try to avoid breaking mirrors, stepping on cracks in the road or spilling salt. Halloween Matchmaking But what about the Halloween traditions and beliefs that today’s trick-or-treaters have forgotten all about? Many of these obsolete rituals focused on the future instead of the past and the living instead of the dead. In particular, many had to do with helping young women identify their future husbands and reassuring them that they would someday—with luck, by next Halloween—be married. In 18th-century Ireland, a matchmaking cook might bury a ring in her mashed potatoes on Halloween night, hoping to bring true love to the diner who found it. In Scotland, fortune-tellers recommended that an eligible young woman name a hazelnut for each of her suitors and then toss the nuts into the fireplace. The nut that burned to ashes rather than popping or exploding, the story went, represented the girl’s future husband. (In some versions of this legend, the opposite was true: The nut that burned away symbolized a love that would not last.) Another tale had it that if a young woman ate a sugary concoction made out of walnuts, hazelnuts and nutmeg before bed on Halloween night she would dream about her future husband. Young women tossed apple-peels over their shoulders, hoping that the peels would fall on the floor in the shape of their future husbands’ initials; tried to learn about their futures by peering at egg yolks floating in a bowl of water; and stood in front of mirrors in darkened rooms, holding candles and looking over their shoulders for their husbands’ faces. Other rituals were more competitive. At some Halloween parties, the first guest to find a burr on a chestnut-hunt would be the first to marry; at others, the first successful apple-bobber would be the first down the aisle. Of course, whether we’re asking for romantic advice or trying to avoid seven years of bad luck, each one of these Halloween superstitions relies on the goodwill of the very same “spirits” whose presence the early Celts felt so keenly.

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

Red Data Girl: My Wish on the Night of the Shooting Stars (Week 19)

Red Data Girl: My Wish on the Night of the Shooting Stars By Noriko Ogiwara A Translation

Miss the last piece? Read it here!

Check out the RDG Translation twitter!

Help me pay for my next translation project on Ko-fi.

Happy Palm Sunday, Easter, and Passover to those who will be celebrating over the next week!

This installation has brought us to page 200 in RDG 6. We’re chugging along! It’s officially spring break for me, which means I’ll have more time than usual to dedicate to RDG. I’m hoping to get a decent amount done each day, and move further through the novel. I think I’ll be done by the beginning of summer!

Translation Notes:

The Namahage are a type of demon portrayed at festivals in certain parts of Japan.

The Night Parade of One Hundred Demons appears in a number of Japanese folktales. It’s more or less just what it sounds like.

Red Data Girl: My Wish on the Night of the Shooting Stars By Noriko Ogiwara Chapter 3: Winter Solstice Part 1 (2 of 3)

Seeing as no one came to the student government room during the study days before the exams, it was a much better place to tutor someone than the library. Talking wasn’t allowed in the library’s reading rooms and any questions a student amassed during their time there were easily forgotten by the time they left and could speak again.

In the government room though, it was perfectly fine to talk. Miyuki also seemed to prefer it over the library because he felt more comfortable when other people’s eyes weren’t on him. They could also talk freely about whatever they wanted when there weren’t other people around. Today, Izumiko was planning to use that solitude to bring up the awkward moment they had had the day before.

However, Miyuki and Izumiko weren’t the only ones to claim use of the student government room. When they arrived, Okouchi and Hoshino were already settled there. Unused to not coming to student government once a day during the pre-exam club hiatus, the two second years had been coming anyway to play around with the computers there.

Okouchi and Hoshino were so lost in their own world though that they never once bothered Izumiko and Miyuki when they studied together or did anything else. Little by little, Izumiko had gotten used to their presence, and didn’t notice them as much as she had at first.

The two second year boys came from very normal families. It was clear that neither of them had been raised in connection with spiritual abilities of any kind. However, while they did know about the students who had been raised with magic, they had reacted quite calmly to their existence. Their reaction probably wasn’t the norm though. The way they interacted with Izumiko hadn’t changed at all either.

The people Honoka collected for student government all must have something special in common, but I wonder what it is… Izumiko thought quietly to herself.

Hodaka and Honoka’s student government had turned itself into a well-functioning group over the past few months, but they had to have all been chosen for some quality they showed. Izumiko was just grateful that no one had been treating her differently since everything with Takayanagi.

The bespectacled duo had liked Miyuki from the start, and Miyuki had gotten along with the older students as well. He seemed to have a respect for their deep knowledge of everything two dimensional. Izumiko could tell that the duo was quite intelligent as well. They just really didn’t care much about anything outside of their own interests.

That day, as Hoshino, Okouchi, Miyuki, and Izumiko were talking, Hoshino said out of nowhere, “Did you know? December 25th, the day that everyone thinks is Jesus Christ’s birthday, was actually decided on by the Christian church after the Council of Nicaea that was held in 325 AD. The Roman empire was showing off the authority it had at the time, and they set the date to intercede with the Mithraic winter solstice. December 25th was the date of that holiday.”

Miyuki looked at Hoshino, and then let out a small laugh. “Does that mean you’re interested in a Christmas event all of a sudden?”

“If this is all common knowledge to the exchange students, it would be embarrassing if I didn’t know it. It was interesting to look things up. Listen to this,” Hoshino continued enthusiastically. “The headquarters of the Greenland International Santa Claus Association is in Copenhagen, and they talk about people becoming certified Santa Clauses on TV and stuff. Also, Scandinavia is seen as Santa Claus’s home. But in Scandinavia, the word they use for Christmas, Yule, is actually the Germanic winter solstice that dates back to before Christianity. Old Man Santa doesn’t appear in that old European festival. Instead, there’s a spirit of some kind who doesn’t give nice presents to anyone. It’s kind of like the Namahage here in Japan. It’s a demon that goes around scaring little kids into behaving well.”

The image of a man dressed up in a demon mask and a straw cape with a sword in his hand going door to door during a festival came to Izumiko’s mind. She had seen it on TV at some point.

“The Namahage is from the Touhoku region in the northeast, right?” she asked. “He’s part of one of their festivals.”

“Yes, yes. He’s the one that goes, “Are there any bad kids here? Are there any crybabies here?”” Okouchi said, his expression serious as he took on the demon’s role for a second.

“The Christmas that Japanese people are used to comes from the US,” he continued. “And US Christmas comes from England. We’re used to the Christmas traditions that come from the English speaking part of the world, but there are many different traditions beyond those. The reason why western Christmas has rooted itself so deeply here in Japan is because Emperor Taisho died on December 25th and the day became a national holiday. It became a normal day again after World War II, but decorating Christmas trees, Santa Claus’s presents, and the winter sales war remain.”

“Have you been researching Christmas too, Okouchi?” Miyuki said doubtfully.

“I need to be prepared so that this doesn’t become a Christian based event. I’m doing this for President Honoka, too.” Okouchi went back to typing on his keyboard. “Christmas trees appear in winter solstice festivals that predate Christianity. Decorating houses with boughs from pine trees comes from early, non-Christian traditions. Decorating with evergreens is said to keep away evil spirits and attract good luck. We decorate with pine branches in a similar way here in Japan. After December 25th became Christ’s birthday, Germany began the tradition of decorating trees in the early modern era. It apparently then spread to England through the royal family. When Europeans first came to America, Christmas trees were one of the customs they rejected as being pagan. They were Puritans after all.”