#iberian poetry

Text

La forma escrita del catalán parece un asturiano aprendiendo el francés sin los sustratos vascos y las falsas influencias celtas, pero hablado por una persona de bajo coeficiente intelectual que actúa como un superhéroe de la cloaca. 🤣

#nft#cringe#palabras#citas#frases#textos#notas#escritos#escrituras#pensamientos#sentimientos#words#quotes#phrases#poem#poetry#jajaja#memes#makeup#entity#dialect#separatist alliance#digital art#photography#lenguaje#superhero#anime#dibujo#cartoon#iberian peninsula

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arabization: The Lost Stories of Transformation

Chapter 2: The Moorish Guardian

The clash of steel echoed across the battlefield, mingling with the cries of the wounded and the shouts of commanders as the Reconquista raged fiercely in 15th-century Spain. The Christian forces, determined to reclaim the Iberian Peninsula, fought with fervor against the Moors, who defended their lands with equal zeal. Amid the chaos, Sir Guillaume de Montfort, a knight of French origin, swung his sword with all the strength he could muster. His armor was battered, his muscles strained with exhaustion, but his resolve remained unbroken.

Guillaume had been raised in the chivalric traditions of France, his sense of honor intertwined with his identity as a Christian knight. He viewed the Moors as infidels, enemies of Christendom, and had come to Spain to prove his valor in the service of God. But on this day, the sheer force of the Moorish cavalry overwhelmed him. Surrounded and outnumbered, Guillaume fought valiantly until his sword was knocked from his hand, and he was pulled from his horse, bound, and taken prisoner.

Dragged through the streets of Granada, Guillaume’s pride was as battered as his armor. His heart burned with humiliation, but as he was led into the heart of the Alhambra, his surroundings began to intrude upon his thoughts. The palace was a marvel of architecture, its walls adorned with intricate carvings, its gardens lush and fragrant with the scent of jasmine. Despite himself, Guillaume could not help but feel a grudging respect for the beauty of the place.

He was brought before a distinguished Moorish nobleman, Emir Yusuf ibn Mansur. The Emir stood tall, his bearing noble, his demeanor calm and composed. Guillaume, kneeling in chains, expected to be met with disdain, perhaps even scorn. But as he looked up into the Emir’s eyes, he saw something different—a mix of curiosity and, surprisingly, pity.

"Sir Guillaume de Montfort," the Emir began, his voice resonating with authority. "You fought bravely, but this war is not just about swords and blood. It is about the souls of men, and the legacy they leave behind."

Guillaume said nothing, his pride preventing him from responding. But the words lingered in his mind, echoing with a weight he could not ignore.

Over the days and weeks that followed, Guillaume remained a prisoner in the Alhambra, but his confinement was not harsh. Emir Yusuf treated him with a respect that confused the knight, and he was given quarters within the palace, where he could rest and reflect. At first, Guillaume resisted any attempts to engage with the Moors, clinging to his beliefs and prejudices. But as time passed, his resolve began to wane.

The more he observed the Moorish way of life, the more he found himself drawn to it. Their poetry was rich with emotion, their science brimming with knowledge, and their faith, though foreign to him, was practiced with a sincerity that made him question his own. Emir Yusuf, sensing Guillaume’s inner turmoil, often spoke with him, sharing the wisdom of his people and the history of their land.

"You see us as enemies," Yusuf said one evening, as they walked through the palace gardens. "But we are more alike than you think. We all seek the truth, in our own ways. The truth of who we are, and the legacy we wish to leave behind."

Guillaume listened, but his heart was conflicted. How could he, a Christian knight, find common ground with those he had been taught to hate? And yet, he could not deny the growing respect he felt for the Emir and his people. It was this respect that slowly began to erode the rigid walls of his identity.

One day, Yusuf invited Guillaume to explore the hidden corners of the Alhambra. The knight, intrigued by the offer, agreed. They descended deep into the palace, through corridors that seemed to stretch into the very heart of the earth. Finally, they reached a door, ancient and heavy, which Yusuf opened with a key that had been passed down through generations.

Inside was a chamber unlike any Guillaume had ever seen. The walls were lined with relics—artifacts of immense historical and spiritual significance. At the center of the room, resting on a pedestal, was a sword. Its blade was etched with symbols, and its hilt gleamed with gold and jewels. Yusuf approached the sword with reverence.

"This sword," Yusuf explained, "is said to have been blessed by the Prophet Muhammad himself. It was wielded by a great warrior who sought to unite the tribes of Arabia under one banner. His spirit, they say, still resides within it, waiting for one worthy to continue his mission."

Guillaume felt a strange compulsion to touch the sword. He hesitated, but something deep within him urged him forward. As his hand closed around the hilt, a surge of energy coursed through his body, as if the sword were alive, as if it recognized him. In that moment, Guillaume felt a connection to the sword, to the warrior who had wielded it, and to the land that had given birth to such a legacy.

From that day on, Guillaume began to change. His dreams were filled with visions of desert sands, of caravanserais where travelers rested and traded tales, of battles fought under the crescent moon. He saw himself not as a knight in shining armor, but as a warrior draped in flowing robes, leading men across the vast expanse of the desert.

His features, too, began to shift. His once pale skin darkened under the Andalusian sun, his blue eyes took on a more olive hue, and his body, once encased in the heavy armor of a knight, grew accustomed to the light, flowing garments of the Moors. Even his thoughts, once centered on Christian dogma, began to align with the teachings of the Quran.

Guillaume found himself adopting the manners and customs of the Moors. He began to pray with them, to study their texts, and to see the world through their eyes. The sword, which he kept close at all times, seemed to guide him, its presence a constant reminder of the path he was on.

The transformation was not without conflict. Guillaume struggled with the idea that he was betraying his past, his family, and the faith that had shaped him. But the more he embraced his new identity, the more he realized that this was not a betrayal, but a fulfillment of something deeper, something that had always been a part of him, waiting to be awakened.

As the Reconquista neared its climax, Guillaume knew that the time had come to make a choice. He could return to his Christian roots, to the life of a knight, or he could fully embrace the identity that had been forming within him—the identity of an Arab warrior.

When the final battle for Granada began, Guillaume, now known as Ghazi al-Mansur, took up arms. He wielded the sword blessed by the Prophet with a skill and ferocity that astounded both his Moorish allies and his former Christian comrades. In the heat of battle, Ghazi led a charge that turned the tide, defending the last bastion of Moorish rule with the prowess of a seasoned warrior.

As the dust settled and the smoke cleared, Ghazi stood victorious. The city of Granada, the last stronghold of the Moors, remained in their hands, at least for a little longer. Ghazi looked out over the city he now called home, knowing that he had fulfilled the prophecy hidden in the chamber.

The battle won, Ghazi returned to the Alhambra, where he knelt before Emir Yusuf, not as a prisoner, but as a brother-in-arms. The chains that had once bound him were gone, replaced by the bonds of loyalty and shared purpose.

"Your journey is complete," Yusuf said, placing a hand on Ghazi’s shoulder. "You have found your true self, not in the past you left behind, but in the future you have chosen to embrace."

Ghazi nodded, understanding now that his transformation had been more than just a change of clothes, or a shift in beliefs. It had been a journey of the soul, a realization that identity is not just a matter of birth, but of choice and experience.

His past life as Guillaume de Montfort was forever left behind, a distant memory that no longer held sway over him. He was now Ghazi al-Mansur, a warrior of the Moorish legacy, a man who had chosen to forge a new path, a new destiny.

As he stood in the heart of the Alhambra, surrounded by the beauty and history of the palace, Ghazi felt a deep sense of peace. His transformation was complete, his purpose clear. He would continue to defend the land he had come to love, to honor the legacy of the Moors, and to live by the principles that had guided his transformation.

The story of Sir Guillaume de Montfort had ended on the battlefield, but the story of Ghazi al-Mansur was just beginning.

Arabization: The Lost Stories of Transformation

Chapter 1: The Scribe's Awakening

Chapter 2: The Moorish Guardian

Chapter 3: The Scholar's Dilemma

#Arabophile#gay#arabization#arabian#transformation#race change#arabophilia#arab men#Booklr#Litblr#IndieAuthor#TumblrWriters#StoryTime#NewWriting#HistoricalMystery#Legacy#ArabianLegends#TransformationStory#DesertTales

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Tell me more about the North African music of protest, because that sounds like a class I would have loved (not speaking Arabic notwithstanding).

OKAY!!!!

So this class is about music and people of North Africa and it is probably the coolest class I've ever taken. It's cross listed in Folk Studies, Anthropology, and African American Studies bc it's a one off and the university couldn't decide where to put it ig??

So the first thing to understand is that defining North Africa is tricky. Generally accepted definitions include Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Western Sahara, and sometimes Egypt. This area of the world could conceivably fit in many different geographical areas: the Middle East (also tricky to define), the Arab World (different from the Middle East!!), Mediterranean countries, Africa. In Arabic there is a distinction between the Mashriq/مشرق and the Maghreb/مغرب, meaning the East (i.e. the Arabian Peninsula) and the West (i.e. North Africa) and Egypt sort of floats between the two depending on what political purpose the definitions are serving at that time. The Maghreb/North Africa is often called Jazirat al-Maghreb (the Island of the Maghreb) in Arabic because it is culturally and geographically distinct from the other Mediterranean states to the north, the Saharan and sub-Saharan African states to the south, and the Mashriq to the east.

So! To get into protest music! After North African states fought for and won independence from their European colonizers (notably the British in Egypt and the French in Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco) they had to decide how to build a national identity, and they chose Andalusi music (music brought by Arab and Jewish migrants from the Iberian Peninsula after it was re-conquered by the Spanish) as a major part of this, and suppressed other genres of music, especially ones that were considered perverse or corruptive. This included Algerian raï and Tunisian mezwid, because they were music by and for the urban poor. Raï and mezwid discussed drinking, sex, drugs, and other taboo subjects, and were generally considered not appropriate for polite company. Raï in particular played with gender roles, with men sometimes singing in a high tessitura and women singing in a lower register. Despite the censorship both of these musics faced, they are arguably the most popular national music in Algeria and Tunisia respectively, and suffer less censorship now than they did in the 1980s and '90s.

Now I've gotten this far without discussing indigenous North Africans, but that's about to change. The Maghreb has been colonized by several different groups over thousands of years: the Romans, the Arabs, and the Ottomans. The people these groups were conquering are the Amazigh (also called the Berber people, but they mostly now self-identify as Amazigh/Imazighen (pl.) meaning freemen, so that's what I'm using). And the Amazigh are still around! For decades after the end of colonization it was forbidden to teach Tamazight, the Amazigh language, or to broadcast their music, but that is slowly changing, and there is a pan-national Amazigh movement to preserve their music, culture, and language! Additionally, there are significant Black populations in North Africa, many of whose ancestors were brought from sub-Saharan Africa to the Maghreb as slaves, or who immigrated to the Maghreb. These populations and their music (Gnawa and Stambeli, most notably) were also suppressed in favor of Arab and Andalusi music. Eventually, in the 1970s in Morocco, a band called Nass el Ghiwane formed, drawing on the different heritages of their members, who were from different parts of Morocco and included men with musical heritage in Gnawa and Amazigh music, to meld this with Arab music and Western rock influences. Nass el Ghiwane was hugely popular, and their music, which often involved spoken poetry or proverbs, was used to critique the state of Moroccan society in a time of intense censorship, and incorporated the sounds of marginalized groups in a new way.

This was probably more than you wanted, but I think it's so interesting! The links go to Spotify playlists/pages if you want to give it a listen!

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

Cassie name thoughts:

Iphigenia- Daughter of Agamemnon and Queen Clytemnestra in the Iliad. After her father killed Artemis's sacred deer, she was sacrificed so that the Greeks could sail to Troy. Can be seen as the first victim of the war, but I see her as a martyr- taking on the burden of her father for the benefit of the Greeks. The name has connotations of sacrifice, duty, selflessness, justice, betrayal, divine power, and goodness. It is a bit girlish, which adult Cassie may not like.

Carthage- Ancient city-empire based in modern Tunis, but spread across N. Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, and the Mediterranean. Known for it's powerful trade and navy. Shields were important religious/cultural symbols, which is interesting for an Amazon. They also had elaborate armor, with gold jewelry, animal pelts, and large helmet plumes. Its not a perfect name, but it fits the precent of city names that appear in Iliad-related epics (Troy is in the Iliad; Carthage is in the Aeneid) and it starts with a "C".

Calliope- daughter of Zeus, Muse of Epic Poetry, and (presumably) is the goddess invoked in the beginning of the Iliad. She doesn't have any battle connections outside of that, but is characterized as being trustworthy and level headed, as she judged a feud between Aphrodite and Persephone and didn't get smited for it. As the muse of Epic Poetry, something could be said about invoking her name for the continuation of legacies, creation of (one's own) stories, and divine inspiration. Plus, her name starts with a "C" and she's a daughter of Zeus. (Artemis of Bana Mighdall is named after a Goddess… so it's probably okay to use that name?)

Anyway, sorry for the wall of text. I have Many Mythology Thoughts

- @doodling-fern (cause tumblr hates gays with side blogs)

these are all fun thoughts, yeah!! the "c" qualification does make me giggle a little but i dig it it's cute. :)

#doodling fern#the more i think on it the fonder i personally get of xiphos#but thats also def bc i think a butch lesbian with a cool sword is the sexiest possible option.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

One-day International Conference “Graphic Poetry in Iberian Comics”: L’adaptation de la poésie à la bande dessinée en espagnol – 23/05/2024 – Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Shirley Ann Hostetler, formerly of Meyersdale, went to be with her Lord on February 18, 2023 at Yakima, Washington, where she had been living by her family. Shirley was born on June 30, 1931 in Greenville Township, the daughter of the late Carl Eugene and Florence (Shunk) Hostetler. She is survived by her brother, Dale Hostetler, (Dorothy), a nephew, Daniel Hostetler and a niece Aimee Hostetler, all of Yakima, Washington.

Shirley’s early elementary education was at the Glade City two room school followed by four years at Meyersdale High School.

She obtained a B.S. degree in Music Education from Bob Jones University in Greenville, SC. and played the piano, organ and other instruments. She also had a Master’s Degree in Library Science from Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, and attended two summer schools at Indiana, Univ. in Indiana, PA.

Shirley retired as a school teacher having completed 32 years of teaching music and library Science in various schools in the surrounding area. She was a life member of both the PA Association of School Retirees and the Somerset County Retired Public School Employees.

Being a charter member of the Meyersdale Grace Brethren Church, Shirley was very active serving her Savior through the years by holding various offices, teaching an adult Sunday School class, singing in and directing the church choir, playing the piano and organ, and serving as a Deaconess for many years as well as other areas. She loved serving her Lord with her talents. “For me to live is Christ and to die is gain” Phil. 1:21.

She was a charter member of the Casselman Valley Choral Society, involved in the Maple Festival, organist at the United Church of Christ for 15 years and an R.S.V.P. volunteer for the Apprise program with the Area Agency on Aging for 15 years.

One of the things Shirley loved to do during retirement was to travel. She fulfilled that dream by traveling extensively in the U.S. as well as in Europe, Iberian Peninsula, the Caribbean many times, Bermuda, Nassau, Mexico, Israel, Canada and Russia.

The following poem was one of many that Shirley wrote. It, along with many others, was published in the Poetry Corner of the Somerset Daily American:

No Time For Him

In youth we had a lot of time

To wonder, play, explore.

But now that we are growing old,

Where is that time of yore?

When we were not yet fully grown,

The cares of life were small.

We worried not about our needs,

Or whether we’d stand tall.

Why have we not the time anymore,

To read God’s Word and Pray?

Because we worry, fret and fume

About a future day.

We have to give the Lord each day

His time for thanks and praise.

If faith takes over in our hearts,

Our fears will be allayed.

Why can’t we learn to put aside

This life of care and woe?

And through the righteousness of Christ,

Our love for Him to show.

Take time, dear friend, to do His will

Upon this earth below.

And when He greets you up above,

“Well done, my son”, you’ll know.

Graveside services will be conducted on February 28, 2023 at 11:00 AM, at Meyersdale Area Union Cemetery. Pastor Randy Haulk of the Meyersdale Grace Brethren Church officiating.

Contributions may be made to the Meyersdale Grace Brethren Church, 112 Beachley Street, Meyersdale, PA 15552.

#Bob Jones University#BJU Hall of Fame#Obituary#BJU Alumni Association#2023#Class of 1952#Shirley ANn Hostetler

0 notes

Text

By Alexis Pauline Gumbs

I wanted to write a poem about how the extreme heat of the ocean is breaking my heart, but the whales beat me to it. In late July, almost 100 long-finned pilot whales left the deep, usually cold waters where they live—so deep, so cold that scientists have barely been able to study them. Together they came to the coast of western Australia and huddled into a massive heart shape (if your heart were shaped like 100 black whales, like mine is). Then, collectively, they stranded themselves on the shore. As soon as they lost the support of the water, their chest walls crushed their internal organs. They literally broke their hearts. Choreographed under helicopter cameras.

I want to write a poem about how capitalism is a sinking ship and how the extreme wealth-hoarding and extractive polluting systems that benefit a few billionaires are destroying our planet and killing us all. But the orcas beat me to it. Off the Iberian coast of Europe, the orcas collaborated and taught each other how to sink the yachts of the superrich. They literally sank the boats. While Twitter cheered.

The sinking ship is no longer a metaphor. The broken heart is no longer a metaphor. Who needs a metaphor in times as hot and blunt as ours? Let’s make it plain.

Marine mammals have been my poetry teachers for several years now. In Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons From Marine Mammals, I documented my awe and wonder at how these animals do, with grace, what I flail at every day, breathing in the unbreathable circumstances of global racial capital, racist sexist ableist systemic violence.

Living on a planet with rapidly rising ocean levels, it seems obvious to me that we should pay attention to our closest relatives in the sea. But now sea lions, whales, and other marine mammals are leaving the ocean, confronting beachgoers and boaters, making themselves impossible to ignore.

My theory? With a boost from our faster communication technology and crowdsourced worldwide media to spread the news, marine mammals are coming up out of the ocean, as they have been for decades, to tell us it’s too damn hot. And why do we matter so much? Why should we be so arrogant as to assume marine mammals are telling us anything? The answer is in the question: because it’s our fault.

You know this already. Carbon emissions from fossil fuels, disproportionately burned by corporations and first-world consumers, are drastically heating the planet, causing extreme weather events, raising the temperature of the ocean and the water levels and impacting every species that has adapted to what author Jeff Goodell calls “the Goldilocks zone” of survivable temperatures in his book The Heat Will Kill You First, published last month. Alarmingly, a study this summer estimated a 95 percent chance that the entire system of currents that keep the Atlantic Ocean and every ecosystem it touches in relative balance (i.e., the Gulf Stream and other currents) will collapse as soon as 2025. Drastically. Extreme. Alarmingly. I have to use adverbs and adjectives to emphasize what I am saying here because I haven’t learned yet how to break my Black heart a hundredfold on a beach where everyone can see it. I haven’t taught my friends and family to intentionally sink the most useless ships.

Since what I have to offer are words, I will continue to write in extremes. For example, in Undrowned I suggested that because of the impact of rising temperatures on the Gulf Stream, we are living on a menopausal planet. The whole Earth is going through what my elders cryptically called “the change.” In this midst of this heat wave, which has led to at least one of my cherished Black feminist elders spending a night in the emergency room, I’m even more convinced.

Let me be clear: “Living on a menopausal planet” does not mean the extreme heat we are experiencing is just a natural part of Earth’s life cycle, as climate-change deniers claim. The volatile temperatures we are experiencing are a result of toxic human actions—just like the hot flashes experienced by menopausal people (many women, many gender-expansive people, anyone who has ever had a uterus or ovaries or stewarded the hormone estrogen) may be impacted by the prevalence of hormone-injected animals and processed food in our diets.

Yesterday, my big-sister mentor, the menopause expert and reproductive justice advocate Omisade Burney-Scott, taught me that the heat menopausal people experience can also be impacted by the long-studied relationship between estrogen and cortisol, the stress hormone; and that for oppressed groups of people—who, as a study at Yale recently confirmed, experience higher cortisol levels triggered by systemic violence against themselves and their communities—volatile body temperatures and other menopause systems can be heightened. The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation has confirmed that women of color are experiencing more volatile hot flashes because of these and other factors. I wonder if the “climate anxiety” we are collectively experiencing is increasing cortisol levels, too. Scientific studies will have to work that out. If the heat doesn’t kill us first.

Whereas menopause—in which a body moves beyond a central need for estrogen—is natural, inevitable, volatile symptoms like extreme hot flashes actually are not. Similarly, while change is inevitable for this planet and all life, the heat we are now experiencing is not. It is the result of toxic systems that are putting stress on every one of Earth’s ecosystems at the same time.

I think menopause is a powerful lens through which to look at this hot planetary crisis, and not only because I am a Black woman in my early 40s with menopause in my imminent future. It is also because our most effective poets, the whales, are the other beings on Earth who also experience menopause. Orcas and pilot whales specifically are two of the four species of toothed whales in which the scientific community has identified and studied menopause. (Note that pilot whale studies have focused on the short-finned pilot whales who live in shallow water—and have also performed mass strandings over the past decade—while the long-finned pilot whales who live in deeper water have mostly evaded scientific study. And good for them!)

Orca and pilot whale communities have both also demonstrated that they follow the leadership of what even the scientist poets call “matriarchs,” the elder mothers, past their years of possibly giving birth. Kate Sprogis, a marine biologist at the University of Western Australia, theorized that it may have been that the 97 long-finned pilot whales who died on the beach followed a grandmother to shore. What if instead of imagining they died because of her mistake, we imagine they participated in her protest? Biologists keeping track of the orcas who are sinking boats trace the training practice to White Gladis, an orca grandmother. Is it possible these whale leaders learned what they learned, decided what they decided, taught what they taught during menopause? And if so, so what?

Omisade Burney-Scott suggests menopause is a ceremony, a liminal space, a space of possibility. “During liminal periods of transformation,” she writes, “social hierarchies may be reversed or even temporarily dissolved. The constancy of cultural traditions can become uncertain, and future outcomes once taken for granted may be thrown into doubt.”

I think about Fannie Lou Hamer, victim of a forced hysterectomy, and Ella Baker in her wise years creating the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and audaciously pushing forward a civil rights agenda in the center of white supremacist violence in the 1960s. I think about Harriet Tubman’s audacity; I think about the upheaval caused by Dominican labor activist Mamá Tingó’s sugar plantation strikes. What did experiencing a drastic change in their bodies teach these community mothers about the possibility of change on the scale of our entire society?

What if we live on a menopausal planet, where underneath this heat, we are supposed to be learning something about change? What if this is where and when we collectively find the wisdom and maturity that comes from letting go of the story about what we are producing, and moving to the eldership vision of what is sustainable for all of us collectively? What if menopause is the greatest undersung gift? The experience that grants us a multigenerational, multi-species consciousness we need. And what are the words that could reach you and get you to join me in trusting the bravest among us, leaders accountable to multiple generations, who have lived long enough to know what is worth risking and when to risk it? Where is my maturity? When will I stop mistaking the excess heat of a toxic system of relations for love? Where else in my life is heat a warning? How can we stop dissociating from what is happening to our largest body, this planet? Is that your chest collapsing or the rainforest burning? What am I sacrificing to try to earn a premium spot on a sinking ship? Is that your breaking heart or an iceberg shattering? And how cool would it be if none of this were a metaphorical? Oh, relief to your furrowed brow, peace to your steaming blowhole. How cool would it be if we followed our teachers and lived what love requires?

0 notes

Text

By Alexis Pauline Gumbs

I wanted to write a poem about how the extreme heat of the ocean is breaking my heart, but the whales beat me to it. In late July, almost 100 long-finned pilot whales left the deep, usually cold waters where they live—so deep, so cold that scientists have barely been able to study them. Together they came to the coast of western Australia and huddled into a massive heart shape (if your heart were shaped like 100 black whales, like mine is). Then, collectively, they stranded themselves on the shore. As soon as they lost the support of the water, their chest walls crushed their internal organs. They literally broke their hearts. Choreographed under helicopter cameras.

I want to write a poem about how capitalism is a sinking ship and how the extreme wealth-hoarding and extractive polluting systems that benefit a few billionaires are destroying our planet and killing us all. But the orcas beat me to it. Off the Iberian coast of Europe, the orcas collaborated and taught each other how to sink the yachts of the superrich. They literally sank the boats. While Twitter cheered.

The sinking ship is no longer a metaphor. The broken heart is no longer a metaphor. Who needs a metaphor in times as hot and blunt as ours? Let’s make it plain.

Marine mammals have been my poetry teachers for several years now. In Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons From Marine Mammals, I documented my awe and wonder at how these animals do, with grace, what I flail at every day, breathing in the unbreathable circumstances of global racial capital, racist sexist ableist systemic violence.

Living on a planet with rapidly rising ocean levels, it seems obvious to me that we should pay attention to our closest relatives in the sea. But now sea lions, whales, and other marine mammals are leaving the ocean, confronting beachgoers and boaters, making themselves impossible to ignore.

My theory? With a boost from our faster communication technology and crowdsourced worldwide media to spread the news, marine mammals are coming up out of the ocean, as they have been for decades, to tell us it’s too damn hot. And why do we matter so much? Why should we be so arrogant as to assume marine mammals are telling us anything? The answer is in the question: because it’s our fault.

You know this already. Carbon emissions from fossil fuels, disproportionately burned by corporations and first-world consumers, are drastically heating the planet, causing extreme weather events, raising the temperature of the ocean and the water levels and impacting every species that has adapted to what author Jeff Goodell calls “the Goldilocks zone” of survivable temperatures in his book The Heat Will Kill You First, published last month. Alarmingly, a study this summer estimated a 95 percent chance that the entire system of currents that keep the Atlantic Ocean and every ecosystem it touches in relative balance (i.e., the Gulf Stream and other currents) will collapse as soon as 2025. Drastically. Extreme. Alarmingly. I have to use adverbs and adjectives to emphasize what I am saying here because I haven’t learned yet how to break my Black heart a hundredfold on a beach where everyone can see it. I haven’t taught my friends and family to intentionally sink the most useless ships.

Since what I have to offer are words, I will continue to write in extremes. For example, in Undrowned I suggested that because of the impact of rising temperatures on the Gulf Stream, we are living on a menopausal planet. The whole Earth is going through what my elders cryptically called “the change.” In this midst of this heat wave, which has led to at least one of my cherished Black feminist elders spending a night in the emergency room, I’m even more convinced.

Let me be clear: “Living on a menopausal planet” does not mean the extreme heat we are experiencing is just a natural part of Earth’s life cycle, as climate-change deniers claim. The volatile temperatures we are experiencing are a result of toxic human actions—just like the hot flashes experienced by menopausal people (many women, many gender-expansive people, anyone who has ever had a uterus or ovaries or stewarded the hormone estrogen) may be impacted by the prevalence of hormone-injected animals and processed food in our diets.

Yesterday, my big-sister mentor, the menopause expert and reproductive justice advocate Omisade Burney-Scott, taught me that the heat menopausal people experience can also be impacted by the long-studied relationship between estrogen and cortisol, the stress hormone; and that for oppressed groups of people—who, as a study at Yale recently confirmed, experience higher cortisol levels triggered by systemic violence against themselves and their communities—volatile body temperatures and other menopause systems can be heightened. The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation has confirmed that women of color are experiencing more volatile hot flashes because of these and other factors. I wonder if the “climate anxiety” we are collectively experiencing is increasing cortisol levels, too. Scientific studies will have to work that out. If the heat doesn’t kill us first.

Whereas menopause—in which a body moves beyond a central need for estrogen—is natural, inevitable, volatile symptoms like extreme hot flashes actually are not. Similarly, while change is inevitable for this planet and all life, the heat we are now experiencing is not. It is the result of toxic systems that are putting stress on every one of Earth’s ecosystems at the same time.

I think menopause is a powerful lens through which to look at this hot planetary crisis, and not only because I am a Black woman in my early 40s with menopause in my imminent future. It is also because our most effective poets, the whales, are the other beings on Earth who also experience menopause. Orcas and pilot whales specifically are two of the four species of toothed whales in which the scientific community has identified and studied menopause. (Note that pilot whale studies have focused on the short-finned pilot whales who live in shallow water—and have also performed mass strandings over the past decade—while the long-finned pilot whales who live in deeper water have mostly evaded scientific study. And good for them!)

Orca and pilot whale communities have both also demonstrated that they follow the leadership of what even the scientist poets call “matriarchs,” the elder mothers, past their years of possibly giving birth. Kate Sprogis, a marine biologist at the University of Western Australia, theorized that it may have been that the 97 long-finned pilot whales who died on the beach followed a grandmother to shore. What if instead of imagining they died because of her mistake, we imagine they participated in her protest? Biologists keeping track of the orcas who are sinking boats trace the training practice to White Gladis, an orca grandmother. Is it possible these whale leaders learned what they learned, decided what they decided, taught what they taught during menopause? And if so, so what?

Omisade Burney-Scott suggests menopause is a ceremony, a liminal space, a space of possibility. “During liminal periods of transformation,” she writes, “social hierarchies may be reversed or even temporarily dissolved. The constancy of cultural traditions can become uncertain, and future outcomes once taken for granted may be thrown into doubt.”

I think about Fannie Lou Hamer, victim of a forced hysterectomy, and Ella Baker in her wise years creating the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and audaciously pushing forward a civil rights agenda in the center of white supremacist violence in the 1960s. I think about Harriet Tubman’s audacity; I think about the upheaval caused by Dominican labor activist Mamá Tingó’s sugar plantation strikes. What did experiencing a drastic change in their bodies teach these community mothers about the possibility of change on the scale of our entire society?

What if we live on a menopausal planet, where underneath this heat, we are supposed to be learning something about change? What if this is where and when we collectively find the wisdom and maturity that comes from letting go of the story about what we are producing, and moving to the eldership vision of what is sustainable for all of us collectively? What if menopause is the greatest undersung gift? The experience that grants us a multigenerational, multi-species consciousness we need. And what are the words that could reach you and get you to join me in trusting the bravest among us, leaders accountable to multiple generations, who have lived long enough to know what is worth risking and when to risk it? Where is my maturity? When will I stop mistaking the excess heat of a toxic system of relations for love? Where else in my life is heat a warning? How can we stop dissociating from what is happening to our largest body, this planet? Is that your chest collapsing or the rainforest burning? What am I sacrificing to try to earn a premium spot on a sinking ship? Is that your breaking heart or an iceberg shattering? And how cool would it be if none of this were a metaphorical? Oh, relief to your furrowed brow, peace to your steaming blowhole. How cool would it be if we followed our teachers and lived what love requires?

0 notes

Text

FLP POETRY BOOK OF THE DAY: Interpretaciones/Interpretations/Interpretações by Felipe Fiuza

On SALE now! Pre-order Price Guarantee: https://www.finishinglinepress.com/product/interpretaciones-interpretations-interpretacoes-by-felipe-fiuza/

RESERVE YOUR COPY TODAY

Felipe Fiuza is a Brazilian who lives in Tennessee, and loves games, martial arts, his friends, his community, and his family. He is an Assistant Professor of Spanish at East Tennessee State University (ETSU), where he is also the Director of ETSU’s Language and Culture Resource Center. As director of the center, he works towards closing the gap between East Tennessean native speakers of English and people from other languages and cultures through language services, such as interpretations and translations, offered by the center. Felipe’s first poetry book, Ucideia, won first place in a peer-reviewed literary contest from the Federal University of Espírito Santo Press, and as a result, it was published on March, 6th, 2020. His research interests are linked to the intersection between literature and cognitive sciences, focusing in Brazilian Literature and in Literature from the Iberian Peninsula. #poetry

PRAISE FOR Interpretaciones/Interpretations/Interpretações by Felipe Fiuza

Felipe Fiuza‘s engaging new book, Interpretaciones/ Interpretations/ Interpretações, achieves the remarkable feat of presenting each poem in 2 languages while establishing a dialogue with a third, creating an immersive experience of sound and vision. I admire the warmth of voice and personality of this work, as well as its formal ambition. The longer poems and sequences seamlessly match form with content and maintain a rewarding internal logic of design. Fiuza displays a bracing sense of humor, one of the more challenging tones to translate, and brings vitality to poems about such contemporary technological experiences as Zoom and identity theft. Fiuza finds a perfect counterbalance to his enlivening wit through a real sensitivity to suffering and personal sacrifice, particularly in “Bluegrass Leaves” and “Your Uncle Renato,” poems that engage the bonds of #family and loss in ways no reader will soon forget.

–Jesse Graves–Author of Merciful Days, and Tennessee Landscape with Blighted Pine

O novo, envolvente, livro de Felipe Fiuza, Interpretaciones/Interpretations/Interpretações, alcança o feito notável de apresentar cada poema em 2 línguas enquanto estabelece um diálogo com uma terceira, criando uma imersiva experiência visual e sonora. Eu admiro a voz reconfortante e pessoal deste trabalho, bem como sua ambição formal. Os poemas longos e as sequências impecavelmente combinam forma e conteúdo mantendo uma recompensadora lógica interna de projeto. Fiuza demonstra um senso de humor revigorante, um dos tons mais difíceis de traduzir, trazendo vitalidade a poemas sobre experiências tecnológicas contemporâneas como Zoom e roubo de identidade. Fiuza encontra um equilíbrio perfeito para seu humor abrasivo ao demonstrar sensibilidade real sobre o sofrimento e o sacrifício pessoal, principalmente em poemas como “Folhas de Bluegrass” e “Seu tio Renato,” poemas que se aproximam dos laços familiares e da perda de maneiras que nenhum leitor irá esquecer tão cedo.

–Jesse Graves–Autor de Merciful Days e Tennessee Landscape with Blighted Pine

Please share/please repost #flpauthor #preorder #AwesomeCoverArt #poetry #read #poetrybook #poems #family

0 notes

Text

영화 알라딘과 이슬람 문명의 황금기

실사 영화 알라딘은 배경이 몇 년대일까? 허구지만 옷 스타일, 건축 스타일, 기법, 돛 여러 개인 큰 배 보면 추정 가능하잖아.

The live-action Aladdin film is set in a fictionalized version of the Islamic Golden Age, which took place between the 8th and 14th centuries. The film's costumes and architecture draw inspiration from a variety of time periods, cultures, and regions, so it's difficult to pinpoint an exact year or century. However, the presence of a large ship with several sails suggests that the film is set in a time period when seafaring technology had advanced to the point where such ships were possible, which would likely place it somewhere in the latter half of the Islamic Golden Age.

황금기 설명해.

The term "Golden Age" is used to refer to a period of time in history that is believed to have been particularly prosperous, peaceful, or culturally significant. The concept of a "Golden Age" has been applied to various historical periods and civilizations, ranging from the ancient Greeks to the Islamic Empire to the Elizabethan era of England.

During a Golden Age, a society may experience significant advances in art, literature, science, and technology. The economy may be strong, and the society may be characterized by a high degree of stability and social harmony. The term is often used in a nostalgic or romanticized sense to refer to a time when a society was believed to have been at its best.

However, the concept of a Golden Age is also often criticized for being overly idealistic and for ignoring the negative aspects of the time period in question. It is also subject to debate and interpretation, as different individuals and groups may have different ideas about what constitutes a "Golden Age."

이슬람 황금기: 기간 나눠서 특징

The Islamic Golden Age refers to a period of cultural, economic, and scientific growth in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. It was a time when Muslim scholars, scientists, and intellectuals made significant contributions to the fields of science, mathematics, medicine, philosophy, art, and literature.

The Islamic Golden Age can be divided into several periods:

The Early Islamic Period (7th-8th centuries) - This period saw the rapid expansion of Islam and the establishment of a vast empire under the Rashidun and Umayyad caliphs. It was during this period that the Islamic world began to develop its own distinct culture and identity.

The Abbasid Period (8th-13th centuries) - The Abbasid dynasty was founded in 750 and lasted until 1258. It was during this period that the Islamic world experienced a cultural and intellectual renaissance, with scholars and scientists from across the empire contributing to advancements in various fields.

The Andalusian Period (8th-15th centuries) - This period saw the rise of Islamic civilization in the Iberian Peninsula, which was known as Al-Andalus. The Muslim rulers of Al-Andalus encouraged cultural and intellectual exchange between Muslims, Jews, and Christians, resulting in a period of great innovation and creativity.

Some of the key characteristics of the Islamic Golden Age include:

Scientific and mathematical advancements - Muslim scholars made significant contributions to fields such as algebra, astronomy, medicine, and optics, building upon the knowledge of ancient Greek, Indian, and Persian scholars.

Artistic and literary achievements - Islamic art and literature flourished during this period, with notable contributions in fields such as calligraphy, poetry, and architecture.

Cultural and intellectual exchange - The Islamic Golden Age was characterized by a spirit of openness and curiosity, with scholars and intellectuals from across the empire exchanging ideas and building upon each other's work.

Religious and philosophical diversity - Muslim scholars were not just interested in Islamic theology, but also in other religious and philosophical traditions, leading to a rich and diverse intellectual landscape.

이슬람 역사 8세기부터 14세기까지 설명해줘. 세기 별로.

Islamic history from the 8th to the 14th century saw a period of significant growth, expansion, and intellectual development. Here's a brief overview of the key events and characteristics of each century:

8th century: The Islamic world experienced a period of expansion under the leadership of the first four caliphs of Islam, collectively known as the Rashidun. The Umayyad dynasty, which succeeded the Rashidun, established their capital in Damascus and expanded their territory into North Africa and Spain.

9th century: The Abbasid dynasty overthrew the Umayyads and established their capital in Baghdad, marking the beginning of the Islamic Golden Age. This period saw significant advances in fields such as astronomy, mathematics, medicine, and philosophy.

10th century: The Fatimid dynasty emerged in North Africa and established their own caliphate in Egypt. The Buyid dynasty took control of Persia and Iraq, while the Seljuk Empire rose to power in Central Asia and Anatolia.

11th century: The Seljuk Empire continued to expand and took control of much of the Islamic world, including Persia, Iraq, and Syria. This period also saw significant developments in art, literature, and architecture.

12th century: The Crusades, launched by Christian armies from Europe, began in the 11th century and continued into the 12th century, resulting in the loss of significant territory for the Islamic world. However, the period also saw important advances in science, philosophy, and technology.

13th century: The Mongol Empire, led by Genghis Khan and his descendants, began a series of devastating invasions of the Islamic world, resulting in the destruction of many cities and the loss of countless lives. Despite this, the period also saw significant achievements in fields such as literature, mathematics, and architecture.

14th century: The Ilkhanate, a Mongol khanate that had controlled much of Persia, collapsed, and a new dynasty, the Timurids, emerged. The Ottoman Empire also rose to power during this period, expanding their territory into Europe and Asia. The Islamic world continued to see advances in science, literature, and the arts.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Viatges canigo

Viatges canigo full#

He was proclaimed "Mestre en Gai Saber" (Master in the Art of Poetry) at the 1880 Jocs Florals (Literary Contest) in Barcelona. In prose, he published "Excursions i viatges" (Excursions and Trips), "Dietari d'un pelegrí a Terra Santa" (Diary of a Pilgrim to the Holy Land), one collection of "Rondalles" (Stories) and another of articles published in the press "En defensa pròpia" (In Self Defence). lis i cants místics" (Idylls and Mystical Songs), "Pàtria", "Montserrat", "Flors del Calvari" and "Aires del Montseny". Notable are his epic poems in the romantic vein "L'Atlàntida" (Atlantis) and "Canigó", and the collections "Idil. Verdaguer (1845-1902) was a rural Roman Catholic priest who served in a variety of pastoral positions and contributed to the ‘Renaixença’ movement with a body of work that includes epic and lyrical poetry, narrative prose, journalism and travel writing, which received a tremendous popular reception unparalleled at that time. Jacint Verdaguer and the ‘ Renaixen ç a ’ cultural movement The poem is one of the milestones of the ‘Renaixença’ movement and its author, Jacint Verdaguer, is regarded as a symbol of Catalonia’s culture and the major writer of the nineteenth century. Canigó is written in extraordinarily rich and affective language and versification. The poem tells the story of the son of Count Tallaferro, the young knight Gentil, who, for the love of Flordeneu, queen of the fairies, leaves the fight against the Saracens. ' Canig ó', a masterpiece of Catalan literatureĬanigó (named after Mount Canigou) is set in Catalonia at the beginning of the 11 th century at the time of the Reconquista, the gradual liberation by the Christians of the Iberian Peninsula from Muslim rule.

Viatges canigo full#

Ronald Puppo’s translation is the first full English version of the poem. Although the book was not for sale, it was distributed amongst several schools in England. ‘Canigó’reflects, in rich language, the trips that Verdaguer made to the Pyrenees between 18, and the sadness he felt at seeing the ruins of the monasteries of Sant Martídel Canigóand Sant Miquel de Cuixà.Įnglish engineer James William Millard had already published part of the poem in 2000 under the name ‘Canigó, A Legend of the Pyrenees’. The poem tells the story of the young knight Gentil who left his fight against the Saracens for the love of Flordeneu, queen of the fairies. Named after Mount Canigou, the poem is set in Catalonia at the beginning of the 11 th century at the time of the Reconquista, the gradual liberation by the Christians of the Iberian Peninsula from Muslim rule. The epic poem was written in the 19 th century by priest Jacint Verdaguer, a leading figure of the ‘Renaixença’(‘Rebirth’), the cultural movement which characterised the Romantic period in Catalonia. This is the title of Universitat de Vic’s professor Ronald Puppo’s English translation of ‘Canigó’, one of the most outstanding works in Catalan literature. Rich in lyrical and thematic correspondence with long poems ranging from “La chanson de Roland”, Ariosto’s “Orlando Furioso” and Spenser’s “Faerie Queene” to Milton’s “Paradise Lost”, Longfellow’s “Evangeline” and Tennyson’s “Idylls of the King”, Verdaguer’s masterful verse rivals all the legendary magic and wonder ot the mountains themselves.Barcelona (CNA).- ‘Mount Canigó. The collision between duty and love is mirrored by the symbolic conflict between, on the one hand, a powerful folk mythology rooted in the natural geography and, on the other, the widely institutionalized universalism of Christianity concomitant to the reconquest of the Iberian peninsula. Catalonia’s towering Romantic poet and rebel priest, Jacint Verdaguer (1845-1902), delves deep into the Catalan imaginary in his foundational long poem “Mount Canigó”, recounting the historical and legendary mix, both tragic and triumphant, of the medieval origins of modern Catalonia. The waging of war between Christians and Saracens is interlaced with an intracultural clash between a folk mythology rooted in the natural geography, where the Pyrenean faeries reign supreme, and the broadly institutionalized hegemony of early medieval Christendom. A tale of Catalonia quantity BuyĪcclaimed troughout Europe soon after its publication in 1886, “Mount Canigó” is set in eleventh-century Catalonia, mostly on the French side in what is today the region of Rosselló, during the Christian reconquest of the Spanish March, today Catalonia.

0 notes

Text

Creo que no es odio cuando digo la verdad, pero lo siento mucho si se ofenden con esta publicación.

Es mejor que hagan una autointrospección y afronten la realidad. Así que:

"Los catalanes son los occitanos varados.

Los vascos son los terroristas alienígenas.

Los gallegos son los falsos celtas.

Los portugueses no son más que una panda de gallegos de imitación."

#jajaja#verdad#hecho#palabras#citas#frases#textos#notas#escrituras#escritos#sentimientos#pensamientos#words#quotes#phrases#cringe#dibujo#cartoon#vergüenza#ghost#caricature#rdr2#red dead redemption 2#gay#nft#entity#fact#iberian peninsula#poem#poetry

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I knew I was a languages nerd when The Theory of Everything came out and I did not care jack shit about what Stephen Hawking was doing because I was so fixated on the fact that Jane Hawking was doing a PhD in Medieval Iberian Poetry, like what a badass.

#light academia#light academia blog#chaotic academia#the theory of everything#langblr#foreign languages#languages#studyblr#langspo#nerdy things#polyglot

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

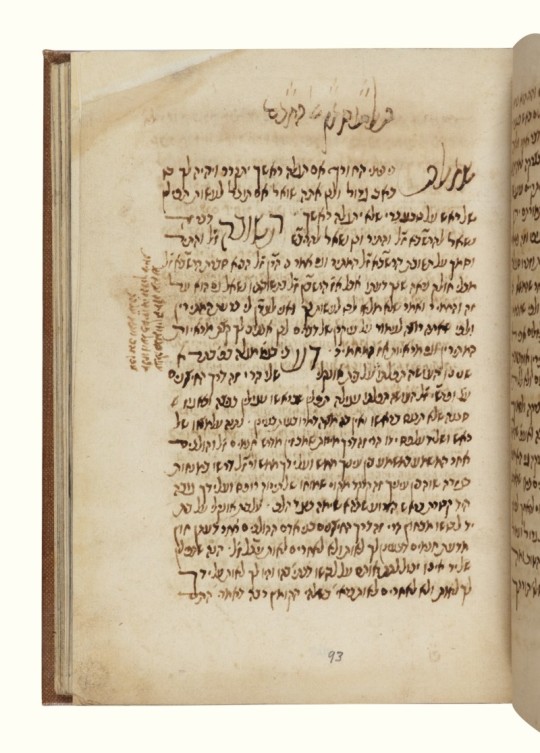

Sefer Nofekh (responsa), Rabbi Abraham ben Jacob ibn Tawwah, Algiers, 16th century

Rabbi Abraham ben Jacob Ibn Tawwah (d. after 1551) was a prominent halakhist, yeshiva dean, preacher, cantor, and liturgical poet of Catalonian extraction based in Algiers. He was a descendant of both the Spanish Rabbi Moses Nahmanides (1194-1270) and the Majorcan-Algerian Rabbi Simeon ben Zemah Duran (1361-1444).

This manuscript, entitled Sefer Nofekh, origninally contained one hundred fifty (the numerical value of the word nofekh spelled without the vav) of his responsa, copied in his hand and, in several cases, signed by him with his distinctive signature: “The most humble descendant of Adam and Eve [Hawwah], Abraham ben Jacob Ibn Tawwah, of blessed memory.” (The manuscript is currently missing thirty-one of the responsa: numbers).

Sefer nofekh not only covers many topics in ritual law but also treats personal status and business law questions. Its pages preserve questions received from Fez in Morocco, Djerba in Tunisia, and several cities and towns in Algeria (Algiers, Tlemcen, Oran, Miliana, Constantine, Médéa, Ouargla/Mzab), especially those that had no local halakhic authority. In his answers, Ibn Tawwah traced the sources of Jewish law from the Talmud to contemporary times, objected to excessive stringency, defended established communal practice, and worked hard to minimize conflicts between members of a community. The book’s essays thus shed much light on the history and socio-religious culture of North African Jewry in the critical period following the expulsions from the Iberian Peninsula and open a window onto Ibn Tawwah’s thought, halakhic methodology, and spiritual leadership.

Ibn Tawwah was a lyrical writer, and many of his responsa include rhymed poetic portions. Toward the end of the volume is a collection of the author’s liturgical poetry, in which he displays great expertise in the principles of traditional Sephardic piyyut.

55 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Ivan Moody (*1964)

Enchedas y Canciones (1996) I. III. IV

The cycle Endechas y Canciones was written for the Hilliard Ensemble between August 1994 and January 1996, and is a sequel to my earlier cycle Cantos Mozárabes, which sets Arabic-Spanish poetry. The first song of the cycle, "No pueden dormir mis ojos", was also the first to be written, while I was composer-in-residence at the 1994 Hilliard Summer Festival, during which it was first performed. To this love song I added two more; all three of them are laments in the characteristically stylized verse of the Iberian Peninsula of the 15th and 16th centuries, whose ritualized structures, rhyme schemes and symbolic imagery have frequently suggested music to me. The second song, "Endechas a la muerte de Guillén Peraza", is a lament for the dead (or dirge) from the Canary Islands. Its remarkable imagery extends even further the interpenetration of the physical and metaphysical worlds present in the first song.

I. No pueden dormir mis ojos

No pueden dormir mis ojos, / no pueden dormir. // Y soñaba yo, mi madre, / dos horas antes del dia / que me florecia la rosa: / Ell vino so ell agua frida / no pueden dormir.

III. Pués Mi Pena Veis

Pues mi pena veis, / miradme sin saña, / o no me miréis. // A mí que soy vuestro / contino amador, / penado d´amor / más que no demuestro , / quiero qu´os mostréis / alegre sin saña, / o no me miréis.

IV. Ojos De La Mi Señora

Ojos de la mi señora, / ¿y vos, qué habedes?, / ¿por qué vos abaxades / cuando me veedes?

_

A Hilliard Songbook - New Music For Voices

The Hilliard Ensemble

(1996, ECM Records – ECM 1614/15)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abd al-Rahmin I was the last of his dynasty. Nearly his entire family was killed in a coup. He fled from Rusafa to his mothers homeland in the Atlas Mountains. Then, he created a kingdom in exile that would control most of the Iberian Peninsula. He would never be able to properly return to where he grew up.

Its easy to see how Frank Herbert took from al-Rahmin I’s story for Dune. He may have drawn directly from his poetry too.

7 notes

·

View notes