#i will most certainly allude to things when they happen but any outright depictions will be delegated to a separate location

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

trans wolfwood is the only wolfwood. To Me.

#speculation nation#itnl shit#tagging bc itnl wolfwood is trans. It Says It On The Tin!!!!#ive pretty much decided against having any sort of smut in the main story. idk not quite my style#MAYBE will do some side one shots or smth. depending. i gotta see how i feel about it#observant ppl mightve noticed me removing the 'rating may change' tag recently bc i have come to my decision. that it wont.#i will most certainly allude to things when they happen but any outright depictions will be delegated to a separate location#for no real reason aside from the fact that it'd feel a lil weird to include in the main story. that's all.#THAT BEING SAID... i need to make sure it's clear that theyre both trans in this#maybe they wont b fuckin n suckin in the main fic but BY GOD i cant have anyone forgetting that theyre both trans#i'll find a way. first things first wolfwood needs to show UP.#and in order to do that i have to actually Write lsjdfldskjf#i was on such a roll with the next chapter. then for Obvious Reasons i have not really had a brain for writing#gonna try to resume tho. soon.#AND i need to reply to comments already. i want my commenters to feel seen and appreciated... life has just been... hard...#anyways t4t vashwood 5ever. that is the truth that i shall spread in my works.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

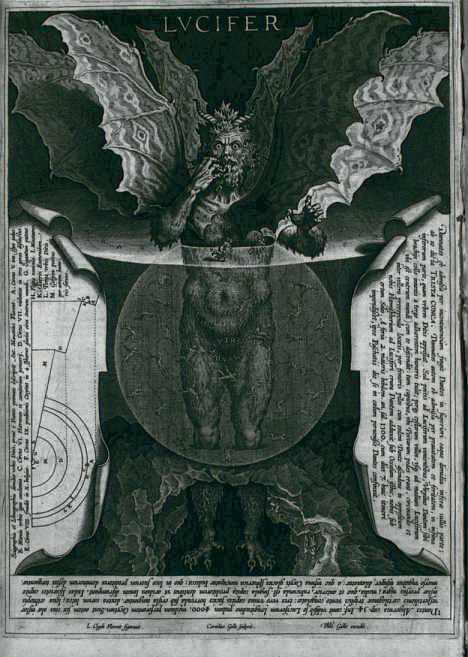

Psycho Analysis: Lucifer/Satan

(WARNING! This analysis contains SPOILERS!)

Please allow me to introduce this villain. He’s a man of wealth and taste...

Satan, or Lucifer, or whatever of the hundreds of names across multiple religions, folk tales, urban legends, movies, books, songs, video games, and more that you choose to call him, is without a doubt the biggest bad of them all. He is not just a villain; he is the villain, the bad guy your other bad guys answer to, the lord of Hell. If there’s a bad deed, he’s done it, if there’s a problem, he’s behind it. There’s nothing beneath him, and that’s not just because he’s at the very bottom of Hell. He is the root cause of all the misery in the entire world.

And if we’re talking about Satan, we gotta talk about Lucifer too. They weren’t always supposed to be one and the same, but over centuries of artistic depictions and reimaginings they’ve been conflated into one being, a being that is a lot more layered and interesting than just a simple adversary for the good to overcome when handled properly.

Motivation/Goals: Look, it’s Satan. His main goal is to be as evil as possible, do bad things, cause mischief and mayhem. Rarely does anything good come from Satan being around. If he is one and the same as Lucifer, expect there to be some sort of plot about him rebelling against God, as according to modern interpretations Lucifer fought against God in battle and was then cast out, falling from grace like lightning. When the Lucifer persona is front and center, raging against the heavens tends to be a big part of his schemes, but when the big red devil persona is out and about, expect temptations to sin, birthing the Antichrist, or tempting people to sell their souls.

Performance: Satan has been portrayed by far too many people over the years to even consider keeping count of, though some notable performances of the character or at least characters who are clearly meant to be Satan include the nuanced anti-villain take of the character Viggo Mortensen portrayed in The Prophecy; the sympathetic homosexual man portrayed by Trey Parker in South Park and its film; the hard-rocking badass Dave Grohl portrayed in Tencaious D’s movie; Robin Hughes as a sneaky, double-crossing bastard in “The Howling Man” episode of The Twilight Zone; the big red devil from Legend known as Darkness, played by Tim Curry; the shapeshifting angel named Satan from The Adventures of Mark Train who will make you crap your pants; and while not portrayed by anyone due to being entirely voiceless, Chernabog from Disney’s Fantasia is definitely noteworthy in regards to cinematic depictions of the devil.

Final Thoughts & Score: Satan is a villain whose sheer scope dwarfs almost every other villain in history. It’s not even remotely close, either; Satan pops up in stories all around the world, is the greater-scope villain of most varieties of three major religions, and his very name is shorthand for “really, really evil.” Every other villain I have ever discussed and reviewed wishes they could be a byword for being bad to the bone. Even Dracula, one of the single most important villains in fiction, looks puny in comparison to Satans villainous accomplishments.

Satan in old religious texts tended to be an utterly horrifying force of nature, until Medieval times began portray him as a dopey demon trying to tempt the faithful (and failing). Folklore and media have gone back and forth, portraying both in equal measure – you have the desperate, fiddle-playing devil from “The Devil Went Down to Georgia” and the unseen, unfathomable Satan who may or may not exist in the Marvel comics universe who other demons live in fear of the return of. Satan is just a very interesting and malleable antagonist, one who is defined just enough that he can make a massive, formidable force while still being enough of a blank slate that you can project any sort of personality traits onto him to build an intriguing foe.

One of the most famous examples of this in action is the common depiction of Satan as the king of hell. This doesn’t really have much basis in religion; he’s as much a prisoner as anyone else, though considering how impressive a prisoner he is, he’d be like the big guy at the top of the pecking order in any jail for sure. But still, the idea of Satan as the ruler of hell was clearly conceived by someone and proved such an intriguing concept that so many decided to run with it.

I think that’s what truly makes Satan such an interesting villain, in that he’s almost a community-built antagonist. People over the ages have added so much lore, personality, and power to him that is only vaguely alluded to in old religions to the point where they have all become commonplace in depictions of the big guy, and there really isn’t any other villain to have quite this magnitude on culture as a whole. It shouldn’t be any shock that Satan is an 11/10; rating him any lower would be a heinous crime only he is capable of.

But see, the true sign of how amazing he is is the sheer number of ways one can interpret him. You have versions that are just vague embodiments of all that is bad and unholy, such as Chernabog from Fantasia, you have more nuanced portrayals like the one Viggo Mortensen played in The Prophecy, you have outright sympathetic ones like the one from South Park… Satan is just a villain who can be reshaped and reworked as a creator sees fit and molded into something that fits the narrative they want. I guess what I’m trying to say is that not only is Lucifer/Satan one of the greatest villains of all, he’s also one of the single greatest characters of all time.

Now, there are far too many depictions of Satan for me to have seen them all, but I have seen quite a lot. Here’s how Old Scratch has fared over the millennia in media of various forms, though keep in mind this is by no means a comprehensive or exhaustive lsit:

“The Devil Went Down to Georgia” Devil:

I think this is one of my favorite devils in any fiction ever, simply because of what a good sport he is. Like, there is really no denying that Johnny’s stupid little fiddle ditty about chickens or whatever sucks major ass, and yet Satan (who had moments before summoned up demonic hordes to rip out some Doom-esque metal for the contest) gave him the win and the golden fiddle. What a gracious guy! He’s a 9/10 for sure, though I still wish we knew how his rematch ended…

Chernabog:

Chernabog technically doesn’t do anything evil, and he never says a word, and yet everything about him is framed as inherently sinister. It’s really no wonder Chernabog has become one of the most famous and beloved parts of Fantasia alongside Yen Sid and Sorcerer Mickey; he’s infinitely memorable, and really, how can he not be? He’s the devil in a Disney film, not played for laughs and instead made as nightmarishly terrifying as an ancient demon god should be. Everything about him oozes style, and every movement and gesture begets a personality that goes beyond words. Chernabog doesn’t need to speak to tell you that he is evil incarnate; you just know, on sight, that he is up to no good.

Quite frankly, the implications of Chernabog’s existence in the Disney canon are rather terrifying. Is he the one Maleficent called upon for power? Is he the one all the villains answer to? Do you think Frollo saw him after God smote him? And what exactly did he gain by attacking Sora at the end of Kingdom Hearts? All I know for sure is that Chernabog is a 10/10.

Lucifer (The Prophecy):

Viggo Mortensen has limited screentime, but in that time he manages to be incredibly creepy, misanthropic… and yet, also, on the side of good. Of course, he’s doing it entirely for self-serving reasons (he wants humanity around so he can make them suffer), but credit where credit is due. The man manages to steal a scene from under Christopher Walken, I think that’s worth a 10/10.

Satan (South Park):

Portraying Satan as a sympathetic gay man was a pretty bold choice, and while he certainly does fall into some stereotypes, he’s not really painted as bad or morally wrong for being gay, and ends up more often than not being a good (if sometimes misguided) guy who just wants to live his life. Plus he gets a pretty sweet villain song, though technically it’s more of an “I want” song than anything. Ah well, a solid 8/10 for him is good.

Satan (Tenacious D):

youtube

It’s Dave Grohl as Satan competing in a rock-off against JB and KG. Literally everything about this is perfect, even if he’s only in the one scene. 10/10 for sure.

Robot Devil:

Futurama’s take on the devil is pretty hilarious and hammy, but then Futurama was always pretty on point. He��s a solid 8/10, because much like South Park’s devil he gets a fun little villain song with a guest apearance by the Beastie Boys, not to mention his numerous scams like when he stole Fry’s hands. He’s just a fun, hilarious asshole.

The Howling Man:

The Twilight Zone has many iconic episodes, and this one is absolutely one of them. While the devil is the big twist, that scene of him transforming as he walks between the pillars is absolutely iconic, and was even used by real-life villain Kevin Spacey in the big reveal of The Usual Suspects. This one is a 9/10 for sure, especially given the ending that implies this will all happen again (as per usual with the show).

The Darkness:

While he’s more devil-adjacent than anything and is more likely to be the son of Satan rather than the actual man himself, it’s hard not to give a shout-out to the big, buff demon played by Tim Curry in some of the most fantastic prosthetics and makeup you will ever see. He gets a 9/10 for the design alone, the facty he’s Tim Curry is icing on the cake.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Good Place: Final Thoughts

*MAJOR SPOILERS*

At the conclusion of season three, I registered my prediction of how The Good Place would end:

The abolition of the afterlife in its entirety (no more good or bad places); a re-emphasis on doing as best you can when it matters (i.e., during one's actual life); the core quartet is sent back to Earth to live out the rest of their natural lives as friends.

I would say that, like most religions, I got about 5% right. The afterlife, as we knew it, is abolished. And the series does end with all of the human characters passing on. But in between, The Good Place takes a much more audacious swing: a genuine attempt to reform the afterlife. And -- and I think this is perhaps even more profound -- an essential acknowledgment that this attempt fell short. A perfect paradise was not created, and in fact the final conclusion of The Good Place seems to be that such a paradise is impossible even in concept. After all, cut away the underbrush and the heroes' solution to the problem afflicting The Good Place was to offer the choice of suicide. And while the penultimate episode suggests that perhaps just having the option will suffice to stave off the ennui of eternal bliss, the finale refuses to accept that out. Every human character, eventually, kills themselves. Their happy ending is that they are content to die. The best possible paradise is one where people can and do eventually choose to erase themselves from existence. Skip over the beatific forest setting and the stipulation of emotional contentment, and that's a rather melancholic, if not outright grim, conclusion. It's easy to draw a parallel between the last episode and the need for fans to accept the voluntarily-chosen end of a great show like The Good Place (it's even easier to draw it to the need to accept our own mortality). But another recurrent theme in The Good Place is the failure of systems. Over and over again, the systems the characters find themselves in are revealed to be either malfunctioning or outright designed to immiserate them. From the very beginning, Eleanor and Chidi confront the brutal harshness of the points system, which results in nearly all people being horrifically tortured for eternity (incidentally, that Chidi isn't immediately repelled by -- and suspicious of -- this set-up is a rare miscue in terms of characterization, if not plotting). They resolve to try and improve Eleanor, only to find out that they're actually in a perpetual torture chamber which will literally reset every time they come close to escaping it. At this point, the series becomes a repeated effort to find ever-higher levers in the celestial bureaucracy that can be appealed to. They find a judge, who is at best indifferent to their predicament and not particularly interested in helping them. Upon returning to earth, they discover first that they can't ever improve enough to enter The Good Place (because -- knowing the stakes -- their motivations are corrupt) and then that nobody can successfully enter The Good Place because existence has become too interwoven and morally interdependent for anyone to satisfy the standard of admission. They meet the actual Good Place committee, who are worse than useless and content to let everyone suffer forever because taking any concrete action risks violating some procedural norm. And when they finally enter The Good Place, they discover it's as dysfunctional as everywhere else -- gradually sucking the life out of its residents who, given eternity, eventually tire of everything. All the systems fail. All of them are doomed to fail. They can't not. Hence, the suicide gate (and sidenote: If The Good Place ever has a spin-off series -- and lord knows it shouldn't -- it should definitely involve exploring the first murder in the Good Place when someone gets involuntarily shoved through that archway). By the time it reaches its conclusion, The Good Place is one of the few depictions of the afterlife to take the concept of eternity seriously. Some other venues glance in this direction. Agent Smith in The Matrix tells Neo that humans reject a simulation of paradise -- the implication is because we're diseased, but perhaps also indicating that perfect, eternal happiness ... isn't. Maya Rudolph's other afterlife vehicle, Forever, certainly touches on this theme. The Order of the Stick has an afterlife where people can eat all the food and have all the sex and otherwise satisfy all the "messed-up urges you people have leftover after having your soul stuck in a glorified sausage all your life". But this is only the "first tier" of heaven: once you're bored, you can "climb the mountain" to search for a higher level of spiritual satisfaction. And while what this entails is left vague, it is not death -- those who ascend can, if they wish, descend back down to the lowlier pleasures (OOTS also introduces the very neat concept of "Postmortum Time Disassociation Disorder"). But the story which provides perhaps the most powerful foil to The Good Place's view of eternity and immortality is (and of the approximately 143,000 Good Place retrospectives being written right now, I bet I'm the only one to make this comparison) Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality. The ultimate adversary in HPMOR is not Snape, or Malfoy, or Voldemort. It is death, and Harry is committed to the "absolute rejection of death as the natural order." The message on the Potters' gravestone is, after all, "The last enemy that shall be destroyed is death" (and it's a sign of my cloistered Jewish upbringing that I thought this was a Rowling original -- it is in fact a quote from I Corinthians). Harry Potter wants people to live forever. And the story anticipates the objection, placed in the mouth of Dumbledore, "What would you do with eternity, Harry?"

Harry took a deep breath. "Meet all the interesting people in the world, read all the good books and then write something even better, celebrate my first grandchild's tenth birthday party on the Moon, celebrate my first great-great-great grandchild's hundredth birthday party around the Rings of Saturn, learn the deepest and final rules of Nature, understand the nature of consciousness, find out why anything exists in the first place, visit other stars, discover aliens, create aliens, rendezvous with everyone for a party on the other side of the Milky Way once we've explored the whole thing, meet up with everyone else who was born on Old Earth to watch the Sun finally go out, and I used to worry about finding a way to escape this universe before it ran out of negentropy but I'm a lot more hopeful now that I've discovered the so-called laws of physics are just optional guidelines."

The last few episodes of The Good Place are, in a sense, a calling of this bluff. Even if you play out the string all the way to extinguishment of the sun or the heat death of the universe -- well, forever is a long time. It can wait. Harry argues that the only reason we accept death is because we're used to it, and if you took someone who lived in a world where there was no death and asked them if they'd prefer to live in a universe where eventually people ceased to exist, they'd look at you like you're crazy. The Good Place provocatively argues the precise opposite -- that if death didn't exist, people would have to invent it. Or they would go crazy, with infinite time on their hands. And so we are, perhaps, back to where we started. The paradise the heroes create is certainly better than that which they replaced. But it still is deeply, tragically flawed -- and The Good Place seems to believe that these flaws are fundamentally inescapable. The suicide option is the clearest manifestation of how cracked paradise must be, but there is another issue that the show alludes to: paradise depends on other people, and on their choices. Way back in the first season, "Real Eleanor" raises this precise point: if her soulmate doesn't love her, "this will never truly be my Good Place." Sure it's actually a contrivance to torture Chidi, but it's easy to imagine it as real. What if your paradise is to live blissfully with a certain special someone and ... that person doesn't love you back? Both Simone and Tahani seem okay with Chidi and Jason respectively choosing someone other than them (Eleanor and Janet). But that's in harmony with the audience's happy ending. It's not hard to imagine a different world where they were less sanguine about it. Or take a far more direct problem: If paradise comes with a suicide option, what happens if your loved one takes it? Harry's excited declaration of all the things he'd do with infinite time is not fundamentally, the reason why he desires immortality. When push comes to shove, he's motivated by a far more basic yearning: to make it so "people won't have to say goodbye any more." Eleanor's utter panic at the thought of losing Chidi forever was, for me at least, the most visceral emotional gut-punch of the entire series -- even more than the finale of season three (at least there, we could be reasonably assured their separation was temporary). She eventually comes to terms with it. But sit on it a little more: imagine a "paradise" where your soulmate has left you forever. People fantasize about heaven to be reunited with their loved ones, yet we end up looping right back into eternal separation. What kind of paradise is this, where people still have to say goodbye? So we have two problems that seem to threaten even the conceptual coherency of a paradise:

First, if paradise is forever, eventually everything will become tired. That suicide is presented as a good solution to this problem shows just how serious it is (and, for what it's worth, I'm not sure the suicide "option" would necessarily bring relief. It could easily generate crippling anxiety -- a sense of trappedness between the irrevocable permanence of death and the unbearable ennui of existence).

Second, if paradise depends on the choices other people make, how can we be sure they'll make choices compatible with your happy ending?

The Good Place presents the first problem as unavoidable and skates past the second entirely. But could they be overcome? Maybe. In the penultimate episode of The Good Place, one solution proposed to the problem of eternal ennui is to reset people's memories, so the things that bored them become fresh again. This is swiftly rejected as a repetition of how the quartet was tortured in The Bad Place. Too swiftly, in my view. Neighborhoods were also used to torture -- should those be jettisoned too? The problem with eternity is that eventually, everything gets repetitive. Go-Kart Racing against monkeys may be a blast the first time, but it loses its luster after a million reiterations. The wistfulness comes from wishing one could go back to that initial burst of discovery and experience -- before one had the memory of doing it all over again. This was my immediate solution to the ennui problem -- not that some demon should periodically reset you, but that you should be able to choose when, where, and how to reset yourself. It's not just about going back in time. It's reoccupying any memory state you've ever possessed. Go back to before you ever raced against monkeys -- then zoom forward to when you've already experienced all the monkey-races you could handle. It's like a load/save system for your mind. Hell, you can even adjust the "difficulty" level. It's true that, for many, a "paradise" where one simply automatically gets whatever one wants will feel unsatisfying. But one needn't set the parameters of paradise to guarantee success. It can be as hard or easy as one wants; people can be as pliant or obstinate as one likes (not for nothing is one of the afterlife attractions in OOTS -- a fantasy roleplaying-based setting -- "The Dungeon of Monsters That Are Just Strong Enough to Really Challenge You"). Or dream bigger. If one has infinite ability to reverse and remake memory as one wishes, then one could at any point adapt any set of memories one ever could have had. Don't just live a different life, remember a different life. Then jump forward and remember all the different lives you lived -- each of which (when you lived them) you had erased the memories of all the others. Every single possible timeline is lived -- and can be relived in all its glory, as many times as one wants. For me, at least, this dissolves the problem of others' choices as well. If anyone can make not just any possible choice, but live through any possible timeline, what does it mean to ask which one is "real"? If your paradise involves loving and being loved by a particular someone, will in your paradise, the person you need to love you, loves you, and stays with you as long as you need. In their paradise, they might love someone else. You enjoy a timeline where people choose exactly the choices that would make you most happy; they live in a timeline which is the same for them. Of course, the sorts of philosophical questions that would raise (among others: What does it mean for the "same" person to simultaneously exist across multiple timelines? Who, exactly, is "choosing" which version they occupy? And if the one that does choose doesn't choose a timeline that involves them loving you back, is the version that does love you really "them"?) are even more esoteric and less accessible to a network audience than the moral philosophy questions The Good Place did try to introduce. So I don't blame them for skipping by it.

* * *

The last enemy to be defeated may not, after all, be death. It may be time. Time ruins all things. Eventually you run out of it. And even if you never ran out of it -- you had infinite time -- it would defeat you in a different way: via boredom, repetition, and ennui. We can, perhaps, imagine a world where we vanquish death. But can we imagine one where (forgot about possibility, and just think conceptually) we defeat time? I can. Barely, but I can. Of course, it's in many ways a moot point, since I'm profoundly skeptical that humanity ever will master time in this way -- or even if it's practically possible (that it won't happen in my lifetime is actually less material, given that if it ever did happen we'd probably be at Omega Point anyway). But at least it holds out the possibility of an actual happy ending -- where the last enemy is truly vanquished, and nobody has to say goodbye. via The Debate Link https://ift.tt/2GK19Yo

6 notes

·

View notes