#i was going to see a show??? i think it was h*milton

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

PROPAGANDA

EVE (PARADISE LOST)

1.) I recognise how insane this submission is because this was written in 1667 and so attitudes towards women were obviously very different. But misogyny has always existed, no matter the time period, and so I think it’s fair to pick up on it. Although Milton somewhat avoids painting Eve as the wicked seductress, she is nevertheless presented as inherently inferior to Adam - her ‘virtue’ and 'passion’ are supposed to be an equal counterpart to Adam’s intellect but Milton’s clear resentment of Eve shines through. She is vain from the beginning - enamoured with her own reflection until she meets Adam. She is Adam’s subordinate and readily accepts her place in the hierarchy below him, until she meets Satan. Women seeking power and knowledge is therefore inextricably tied to the fall of mankind. Her attempt for some kind of independence away from Adam (going to tend the garden away from him) is also presented as the primary reason she succumbed to Satan because Adam is needed to protect her. Eve (the mother of all women) therefore creates the assumption that women are weak and easily misled away from men. The description of her eating the apple is very sexual - perhaps reflecting the anxieties of men at the time of being cuckolded and therefore dishonoured by their wives. She is the ultimate disobedient, dangerous wife. Her reason for sharing the forbidden knowledge with Adam, rather than keeping it for herself, is because she is worried she will face the wrath of God and be replaced with another Eve. So it is her jealousy that brings them both down. (It is all a lot more complicated than this so Eng lit people don’t kill me) but yeah poor Eve.

CORDELIA CHASE (BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER/ANGEL THE SERIES) (CW: Pregnancy)

1.) (downs an entire bottle of vodka and slams it back on the table) SO. CORDY. Cordy started off as a supporting character in Buffy the Vampire Slayer. At the start she was your typical high school mean girl character, but as the show went on we got to see more depth to her character: her insecurities, her courage, her capacity for incredible acts of kindness. Then after the third season she moved into the show’s spin off, Angel, where from the beginning she was basically the show’s secondary protagonist. Her and Angel were the two mainstays of the show’s main cast, she gets the most episodes centered on her out of all the characters aside from Angel (and yes, I’ve checked), and we really got to see her grow from a very shallow and self-centered and kind of mean person to a true hero who was prepared to give up any chance at a normal life to fight the good fight while still never losing the basic core of her character. There were some… questionable moments like the episode where she gets mystically pregnant with demon babies and things got a bit iffy like halfway through season 3 where the writers seemed to run out of ideas for what to do with her outside of sticking her in this romance drama/love triangle situation with the main character but overall, pretty good stuff right? THEN SEASON 4 HAPPENED. In season 4 she gets stripped of literally all agency and spends pretty much the entire season possessed by an evil higher power, and while possessed she sleeps with Angel’s teenage son (who BY THE WAY she had helped raise as a baby before he got speed-grown-up into a teenager it was a whole thing don’t worry about it) and gets pregnant with like. the physical manifestation of the higher power that’s possessing her. it’s about as bad and stupid as it sounds and also is like the third time cordy’s got mystically pregnant in this show and like the fourth mystical pregnancy storyline overall (you will be hearing more on that note in other submissions I’m so sorry). after giving birth she goes into a coma, in which she remains for the rest of season 4 and the first half of season 5. SPEAKING OF WHICH DON’T THINK SEASON 5 IS GETTING OFF SCOT FREE HERE. yeah so in season 5 the show just FULLY starts trying to erase cordy’s existence. she gets mentioned ONCE in the first episode and then never again until halfway through the season where she wakes up, helps out Angel for a bit and encourages him in his fight against evil, and then goes quietly into that good night and dies so it can be all sad and tragic. I’d call it the worst fridging of all time but even THAT feels generous because the whole point of fridging is killing off a female character so a man can be sad, and after Cordy dies basically no one’s even sad about it because the show immediately goes back to pretending she never existed. she is not mentioned ONCE in the two episodes after she dies. in the whole stretch of time between her death and the end of the season she gets mentioned exactly four times. again, I counted. anyway the fun twist to all of this is that all of this happened because the actress who played cordy got pregnant before season 4 and joss whedon was so pissed off about this affecting his plans for the show that he decided to completely fuck over her character and then fire her and write her out of the show. so cordy’s a victim of both writing AND real life misogyny!! good times!!

2.) OH SO MANY THINGS they menaced by giving her terrible hair cuts, making her seem like she’d get together with the guy she loves (and who loves her back) but instead she was killed and when she was brought back, she got possessed by an evil entity who used her body to give birth to itself. afterwards she was in a long coma and died. her character was so throughoutly assassinated

3.) She got demonically pregnant TWICE - there was this real sense of a womb/ability to get pregnant as like, a place for evil to get in. She got positioned as femme fatale and evil mother. The actress basically got fired for being pregnant, and when she agreed to come back for a single final episode she specifically said they could do anything but kill off the character. Guess what happened

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

why is it that when the first shutdown happened for over a YEAR only frozen beetlejuice and mean girls closed but now there are shows dropping left and right

#i think i know the answer but still this sh!t is freaking me out. like seriously. diana jagged toacm waitress atp… probably forgetting more#but it’s absolutely insane and i am genuinely scared. not that im going to be able to go see anything it’s just very…….. agh. i think big#shows like wicked and hadestown will be ok and i hope they will and not just bc i want to see them but like.. what abt moulin rouge and#2 problematic shows that shall not be named and like… god idk what other musicals are going rn. lion king and h*milton will be ok but idk#the ‘smaller’ ones are just freaking me out and making me sad. bway is an indicator for me for how bad things are getting and it shouldn’t#be bc it’s so didfeeent from what my daily life is like but when there’s been like 6 fuck!ng closure announcements in 2#weeks or whatever there is something very very wrong#tess talks

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

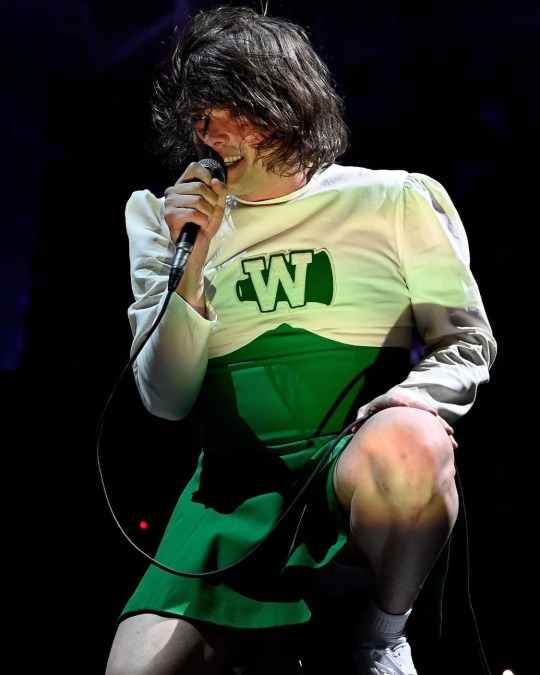

Top 5 gerard tour outfits (so far)

Ooh, another good one! I'm assuming you just meant on the 2022 tour so far? Let's see:

Nashville cheerleader outfit takes the cake by far for me. Iconic. Iconic. ICONIC. Always wish I could replay this day.

Gonna go with my other personal favorite here? Glasgow mud covered look! One of the times I will admit that Gerard looked h*t LMAO.

I think I'm gonna put Montreal Olive Garden demon waiter here. He looked absolutely terrifying, but still made it work!

Meta Man at Milton Keynes! It gave off Revenge vibes and it too was iconic!

I'm gonna put Pool Boy at the Vampire Mansion and short shorts as my fifth choice. The shirt was amazing along with the fact that was simply just the Philly show and I was supposed to be there... :(

Thank you so much anon! 😃

96 notes

·

View notes

Note

Slow dancing as Good Omens fic prompt? I think slow dancing can be really intimate because of the proximity, the looks, the music...

bless you, anon.

***

Aziraphale had never really felt lonely before.

It may come as a surprise to many, but, truly, Aziraphale had never felt lonely. He is an angel who appreciates having time to himself. He is an angel who has chosen to roam Earth on an extended solo holiday for roughly six thousand years, Eat Pray Love style. He is an angel who has set up wards all around his bookshop so every customer is miraculously coerced into leaving the shop after ten minutes of perusing. Up in Heaven, Aziraphale is famous for being a soft, squishy introvert- baffling all the angels, archangels, cherubs and occasional saint.

Being alone is nice.

Being alone isn’t the same as being lonely.

Now, Aziraphale does feel lonely. He stands in the centre of his empty bookshop. A bookshop filled with inanimate, dusty things, but no one there other than him. All these books that he’s always valued so highly, loved so dearly- he still does- but somehow, now, they’re all disappointing to him. The shop feels desolate. The dust particles dancing in the air no longer appear beautifully ethereal, only melancholic; the light pouring through the windowed dome up above feels pale and watery; the silence funerary.

Aziraphale rests a hand on a copy of Milton’s Paradise Lost, and thinks of what he might be missing.

A loud voice in his head tells him that he shouldn’t be thinking- why is he even trying to think about this? The answer is right there, sitting inside him and squirming happily, nervously, miserably. He knows what’s missing, what’s always been missing, yet what’s been there this whole time. Waiting for him. Staring at the chessboard expectantly for him to make his move. Handing over briefcases of books and offering lifts home. And it’s only really since the flop that was the apocalypse last week that he’s seen it for what it is. A perfect clarity, a glorious surety that Aziraphale has never, ever experienced till now- about anything.

It doesn’t come to him in a thought. The decision isn’t made through any logical thought process like: I know what to do. No, it comes to him in a surge, too sudden and overwhelming to hold back or consider for too long. Too sudden for his usual cowardice.

Aziraphale’s feet take him to the phone. He runs his fingers through the numbers, turning the dial, and waits.

He waits only three seconds.

“Alright, Angel.”

And it’s like that surge disappears as quickly as it came- a burst of air lifting a leaf off the ground, only to let it fall, fluttering to the cold, damp ground of reality. Aziraphale swallows. Feels the moment catch up with him with horrifying speed.

What is he meant to say now?

“H-hello, Crowley,” he says through a forced smile, though Crowley’s not there to see it. “I was. Well, I was just wondering.”

There’s a pause. A long one. Aziraphale’s mouth clamps shut. Now is not the time to falter, he thinks to himself.

“Must be a big thing.”

“Sorry?” he breathes, broken from his reverie.

“Big thing. That you’re wondering about. If you’re calling me and breathing down the phone. I can practically feel the anxiety creeping through the wires.”

His mouth opens and closes. Then opens again. And he croaks, “Yes. Um, what I wanted to say was. Was this.” He hesitates, but only for a beat too long. He scrunches his eyes closed. Scrunches them so tightly he can see stars. “Music.”

“Music?” Crowley repeats immediately, dumbfounded.

“Yes.”

“Music.”

“Yes,” he replies, sounding irritated. He’s irritated at himself more than Crowley. He’s rolling his eyes to himself for being so absurdly flappable. He is always the first to be flapped by the silliest things.

“Right.” A pause. “You. So. Yeah, you’ve got to help me out here, Angel.”

“What I mean to say- very, very badly, really,” he says, wincing again, “is whether you’d like to come round to the shop. Help me sort through my mess of a record collection that you’ve been nagging me about since 1964.”

Another pause. Then, “Oh.” Pause. Aziraphale’s perfect posture stiffens impossibly further. Ankles together, foot tapping. “Yeah. Well, what’s all the fuss about then? You sound stressed. Like a… a stressed person. Not a person asking someone round for a drink and some music.” Pause. “There will be drink, won’t there?”

It’s impossible that he finds himself smiling and relaxing, given how far up his throat his heart is currently climbing. And yet. “Oh yes. Don’t you worry, my dear, there will always be drink pouring.”

“Alright. Well, yes. Obviously yes. Even if you’re being weird. You are aware that you’re being weird, aren’t you?”

“Painfully aware, yes,” Aziraphale answers truthfully. Then, quickly, “Shall I uncork the Montepulciano and let it breathe?”

***

They’re on their knees by a teetering stack of vinyl records. The bottle of Montepulciano is finished and there’s another uncorked on the desk beside them. There’s the smell of grapes and dust, a combination that’s become a smell of home to Aziraphale. Made all the more familiar and comforting by Crowley being here, by his side, tearing his beautiful red hair out in annoyance.

“This one isn’t even in a sleeve,” Crowley announces, aghast. He waves the vinyl in Aziraphale’s face, yellow eyes wide. “When are you going to look after the rest of your things the same way you look after books?”

“Oh, I don’t know,” he replies casually, knowing that’ll just infuriate Crowley further.

It does- he growls desperately, creating a new neat pile of vinyls without sleeves, next to the piano music pile, to the right of the 1500-1600s classical pile. Aziraphale smiles sweetly at him, and Crowley points an accusatory finger, sleeves rolled up to his elbows.

“You,” he starts. “You need to get some shelves. Otherwise. Otherwise, I’ll come round here every day to check that you’re putting them somewhere safe.”

I wouldn’t stop you, Aziraphale thinks. I invited you here because you fill up my life. He says, “I don’t have room for shelves.”

Crowley’s mouth hangs open. He casts his gaze about the shop, gestures to the room. “It’s a bookshop! Tonnes of shelves! What’s one more pissing shelf going to do? Tear the fabric of the universe? ‘Sides,” he slurs, one class of red too many perhaps, “you could just extend the shop a smidge or two. Miracle it a cheeky inch or two bigger. Encroach on the neighbours’ space, sure they won’t notice.”

“Perhaps.” He thinks about this as Crowley blows the dust off a vinyl record of Mendelssohn. “Although I reckon they would. Humans can be horribly observant.”

Crowley hums knowingly. “Oh, yeah. When they want to be. When they don’t, they’ll turn a blind eye to anything.”

Aziraphale watches Crowley for a second longer. Tears his gaze away and looks down at the Glenn Miller record in his hands. He feels the dog-eared edges, soft cardboard between his fingers. He peers down at the smiling, black and white image of Miller and he’s taken immediately back to 1941. The Blitz, the smell of ash and smoke and the smallest, most precious moment of fingers touching. A feeling of pure adoration that’s never left him- that’s been there since the beginning, waiting. Triggered by one moment.

And just like before when his feet took him to the phone, Aziraphale’s body is taken by a surge of surety, bravery, knowledge of what he wants- damned if it’s right or wrong. (How freeing it is, to no longer have Heaven watching.) He removes the record from its sleeve and with his free hand, lifts the pin of the gramophone. Crowley stills where he’s knelt by Aziraphale’s feet, and they both listen to the crackle of dust being picked up by the pin.

Aziraphale stands by the gramophone and closes his eyes. Moonlight Serenade begins to play and he takes a deep, grounding breath.

“You remember that day,” he says, neither explaining nor opening his eyes to look down at Crowley.

His response is quiet, and almost immediate. “Yes.”

Aziraphale smiles. “I believe I owe you a dance.”

“You-”

“Don’t think of it as a ‘thank you’,” he continues. “I know you don’t like those. Perhaps just a dance?”

When he finally opens his eyes, it’s only after another deep breath- the nerves have made him forget how to breathe any other way. The shop is getting dark. The light is grey, there’s the quiet sound of rain hissing against the windows, and the song continues to play. And through the haze of dust and stacks of records he sees Crowley, kneeling at his feet, looking up at him with a look as if he doesn’t trust what he’s hearing.

Aziraphale therefore adjusts the look on his own face, betraying his nervousness, and smiles. It comes more easily than he thought it would.

He extends a hand.

Crowley looks at the hand. Lips parting and mouthing something silently, uncertainly. Then he croaks, “The 40s was a wonderful time for music, if nothing else.”

And he feels Crowley’s hand slip into his. It doesn’t send a jolt of anxiety or excitement, it doesn’t set off fireworks or give him butterflies like he imagined it would. It feels perfectly natural.

As Crowley stands up to his full height and looks at Aziraphale, he doesn’t let go of his hand.

The music sounds distant. Each passing moment feels very real. Crowley has frozen. Aziraphale knows all too well how paralysing this uncertainty is- and so he takes Crowley’s other hand and guides it to his waist. He sees Crowley’s eyes flutter and widen, hears his throat click as he swallows, feels his fingers grip harder on Azirphale’s hand.

“I think,” Aziraphale supplies once he’s shown Crowley’s where to put his hand, an abbreviated version of: I think that’s where your hand should go, although I’ve never done this before since I’ve only ever really wanted to do something like this with you, and I’m only just brave enough to do it now, and I hope I’m not misreading things and wrongly assuming you want this too.

Crowley nods. He nods and nods and nods compulsively, swallows again and fumbles for words. Hand warm in Aziraphale’s, warm on his waist. “Yeah,” Crowley manages. “Yeah. I’d say this is- seems about right.”

And Aziraphale rests his hand carefully- so carefully- on Crowley’s shoulder. He leaves it there and neither of them move. They stare at each other in disbelief that this is happening. They stare in disbelief that it took this long. They stare at each other, waiting for the other to start dancing, to explain what comes next, anything. Crowley’s eyes wide and his brows pinched, lips parted.

“Aziraphale?” he asks weakly.

And then it feels easy, heartbreakingly easy. Easy to smile, easy to be the brave one for once, to let Crowley be vulnerable. Easy to let the thousands of years pour through him and between them, between joined hands.

“Come here, my dear.”

Aziraphale steps closer. Fingers gripping tighter, frightened of what might happen if the other lets go. Would this moment disappear, as if it never happened at all?

Aziraphale tilts his head towards the ground and looks up at Crowley through his lashes. A gesture that is shy and self-conscious and happy. And Crowley huffs- a laugh, perhaps, or a sigh, he isn’t sure. He feels his breathe blossom against his skin.

He closes his eyes. He feels it all. He absorbs all the time spent together, all the time lost. The music brings them absent-mindedly swaying from side to side, and Aziraphale rests his cheek against Crowley’s. He’s warm. When he cracks his eyes open he’s welcomed by an auburn blur. The hand on his waist finds his back, and there’s the rush of a sigh beside Aziraphale’s ear. Then, a forehead against Aziraphale’s shoulder.

The song ends, the gramophone crackling to a stop. They dance in each other’s arms for a little longer, in a shop no longer empty.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

4 POEMS by Jake Sheff

Elegy for Dog I: A Failed Acrostic

January was tired when it became king. Apples here love being red in the spring, Casting shadows against the stone architraves our Kapellmeister will never live down. You Stole Apollo’s cows, and let them graze to show me Heaven’s template. Where do failed heroes go? Eucalyptus cupolas and polar icecaps Frame the downtrodden gods. But you weren’t Freakishly wrong, as I so often am, on your

Joyride through nearly twice eight years, Á la someone far from beauty’s stepmom. Copper coin or grimacing sun? I’ve got 20,000 Kor of crushed grief on this threshing floor. Shark-sparks of sadness flood the impetiginous air… How, and why, do clouds cobblestone Entire days, and lakes, when you’re not here? Fixing every broken thing, poets go where Ferns and geraniums baptize the morning.

“Jur-any-oms,” is how you’d spell it; After all, a dog’s a dog, and wisdom knows futility. Cassations make a rusty brew, to drink the truth of truths, and Kill whatever ceases wanting to be new. Stewardship, the color of gravity’s silence, naturally Houses every “glur” (a glittery blur); go chase what plays Eternal games. I hear the swans by Rooster Rock. Your handsome Face, its happy handsomeness, in memory’s eye, goes in and out of Focus; in love’s better eye: your goodness neath its everblooming ficus.

Gravity and Grace on SW Murray Scholls Drive

“Impatience has ruined many excellent men who, rejecting the slow, sure way, court destruction by rising too quickly.” Tacitus, The Annals of Imperial Rome

The traffic lights control the people’s actions, but Not their feelings, as the limits of philosophy Collide head on with the nose of a Dalmatian.

I tell you, the day is stress-testing itself, and these Sidewalks wish that it’d just gone straight. Geese Take this sky-hairing wind for granted, as they

Land on the lake like memorable speech on The sensitive soul. Time is never sharp, but it’s Cutting something in the credit union. Maybe

It’s dancing a back Corte for the woman in line Thinking about the taste of limes from Temecula As she waits for the teller. Air Alaska and that

Haunted pie in the sky are not the only reasons For all the volatility in the air today. Rushing And perfectionism both produce a loss; behind

The Safeway Pharmacy, you’ll see the small Smells of both, sloshing around to the ticking- Sound of the ocean’s tides. I must admit, I am

Frozen in place by the sight of steam from Joe’s Burgers; it is poetry’s pale tongue, rising in And arousing the air. This neighborhood’s street-

Lights are more serious than kokeshi dolls. Lights From its windows outshine poison dart frogs. Maybe to forget about life for awhile, the lamps

Are focused on The Population Bomb? ‘Easy Tiger,’ all these incidents whisper. Each day’s A sign twirler’s dais; each corner a promise

Of something more in a different direction: it isn’t A marriageable daughter or impoverishment, But inguinal ingenuity plays a part, and that isn’t

Bad at all. What oaths and paths went here Before Walmart? What voices were voided by The liquor store? What are vague’s values

When the library shares a parking lot with a 24- Hour gym and a cargo cult? Gas stations satirize The Queen of Hearts; I tell you, it makes every

Question seem incidental. Treaty-breakers in Pajamas swing on the swing sets. Was August That full of angst? It feels like autumn went too

Far on accident. Desertification, in a sugar tong Splint, takes a shot of ouzo and talks shit About the death of Brutus, but my Bible-thumping

Memory – on a ski hill in Duluth – is also too busy Watching some ducks on the lake to notice; and Desertification makes a face at me like a Swedish

Film. Poets make for poorly picked men to Familiarity’s paymaster-general. The Calvinistic Rain is an ill-starred attempt to make mayonnaise-

Fries just for me, but I must admit, it all seems – You know – cybernetic. And step-motherly as all Get out, if you ask the trees. They prefer “You

Can’t Hurry Love,” by The Supremes, to any Changes that take effect in one to two pay periods. Pretext ricochets; a perfect reverse promenade.

At Summer Lake, When the Vegetables are Sleeping

Cruelty drinks all the wine, and never gets drunk On these shores. When Summer Lake speaks, In every word, an introduction to the world. I am

Easily duped. The greatest duper duplicates my pride, Which always lingers, in the hallways of my heart And beneath the surface of Summer Lake. The sky is

Supplicating, it’s literally shaking. An hour passes Faster here, the hour always held too dearly dear In paranoid and ivied walls. The ducks can do

An unwise thing correctly, and it sounds more like Dusty than Buffalo Springfield to the enokitake Sold in Springfield, Illinois, which is the opposite

Effect it has on the wild mushrooms on these shores. On cables capable of love, the geese convince The weather to taste like kvass today. Basically,

Another Cuban Missile Crisis drowned itself just Now. The clouds might ask themselves, ‘Is lowliness Allowed here?’ To which the crows might ask,

‘Does omertà sound like lightning?’ The answer’s Oubliette is ten times worse than impotence. Summer Lake isn’t smart, but it stays quiet, like

Someone too smart to say all they know. ‘Whoa, Sweet potato,’ the capital gains tax mutters To itself, knowing that what matters doesn’t mean

A thing. Some say the lake bottom’s sands receive Commands from Hearst Castle, others say Its hands are King City’s hands, and still others

Maintain more sins have been than grains of sand Times secondary gains, and that explains The beauty and industry that none can see but

All can feel on these shores. (Some possibilities Play possum, or get opsonized by hate; this one snores Like Rip Van Winkle.) This orb-weaver spider is

The Milton Friedman of Summer Lake, the wind On her web is Grenache from The Rocks District Of Milton-Freewater AVA for the eyes. The day is

Stereotypical, although it feels like three days In one…But for the lake’s good counterfactual Questions, I would forget that some die young,

But most die wrong. I’ve tried to pick up Summer Lake’s reflections in three lines or less, but The hardest truth is your own impotence. Oh,

It’s hard to hand your power over to a thing No one can see. Hopped up on distinctions – not The obvious distinctions – Summer Lake is pretty;

Cold, but pretty! In the distance, with so many Intercessory prayers, hot air balloons are rising; Shaped like teardrops, upside down and rising.

This lake re-something-or-anothered me. Are first Impressions wrong sometimes? I am a season’s Golden calf, according to the sunlight, doing

A prospector’s jig on the surface of Summer Lake. If not for the Weimar Republic’s wooden- Headedness, I’d set down my heart-song and

Listen to reason on these shores. I never trust An activist guitar, if the weather is socially clumsy. The future is reflected on the lake: it always

Laughs at us – between its math and gratitude Lessons – and never thinks of (or gives thanks to) Us enough. The presence in the lake juniors

My ears. The day is not too baffling, nor is it Jane Eyre. Space-themed and spiritual, some autumn Leaves are swimming in the rain. The ducks arrest

My attention in the mardy weather, even though they Must know my attention is dying. The barbed wire Around my stated goal is an outcome out of

Their control. Picnickers picnic with acorns and apricots, On blankets covering Holy Schnikey’s death mask. My unsandaled thoughts thrive and increase on these,

And no other shores. They are pets for the days less Important than love, when Summer Lake says it’s Humble, because it knows the right thing to say.

Summer Lake gives the comfort of commonly held And seriously absurd beliefs to the blue heron. Nothing is wrong with this lake or anything in it,

Not even the ghost of Amerigo Vespucci. It’s all so Simple to the stiff-necked molecules of water, made out Of frogs and snails and puppy-dog’s tails. These thoughts

Are fine manna in a fine ditch. Post-structuralist squirrels Can tell my heart’s in Italy, and I’m in the intellectual Laity. Chivalry’s technician sees my shovel, and they say,

‘You’ve got to hand it to him.’ Neurocysticercosis Sets the bar high; it looks at this park, and thinks The smartest monkey drew the perfect landscape.

That’s this maple tree’s previous disease, its precious One. It unfurls the ferns of my firm and foremost Beliefs, I’m told, to partialize insufferable vastidity.

We Install a Sump Pump on (What Used To Be) a Holiday (Take 2)

The oppressive heat was born a fully grown Man. I admire the result of its effort, but Despise the means of achieving it. My wife Asserts her individuality in the gunk; her Body’s allegations aren’t too soft or hard today. Her self-interest seems to have drowned in the vortex.

Our little garden knows flippancy with regards To privacy is unwise. The stepping stones can Only blather, as slugs draw nomograms on Their faces. My wife’s body speaks Proto-Indo- European in the vortex and denim overalls. Marc Chagall’s The Poet studies her. He calls her

‘Innocence: The opposite of life! A criminal with A badge!’ I hand her the tools of a crude and Rudimentary faith, and she says, ‘Jill, great books Make fine shackles.’ Her arms only have An administrative objective in the vortex, but They are where good things come from.

Jake Sheff is a pediatrician in Oregon and veteran of the US Air Force. He's married with a daughter and whole lot of pets. Poems of Jake’s are in Radius, The Ekphrastic Review, Crab Orchard Review, The Cossack Review and elsewhere. He won 1st place in the 2017 SFPA speculative poetry contest and a Laureate's Choice prize in the 2019 Maria W. Faust Sonnet Contest. Past poems and short stories have been nominated for the Best of the Net Anthology and the Pushcart Prize. His chapbook is “Looting Versailles” (Alabaster Leaves Publishing).

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

So this is not a H*milton ask, but are you a musical person? Hadestown is one of my favorites, and I've recently gotten into the Beetlejuice soundtrack...

I like musicals, yes. My all time favourite movie to date is Rocketman, actually! (It does help that my mother is a big Elton John fan, so I've listened to his music since birth and grew up to love him too.) Taron Egerton does a fantastic job with both the music and performance. Like holy shit I get excited/emotional just thinking about that movie... honestly I could talk about how amazing it is for hours please if you’ve never seen it go watch it. Even if you’ve never heard a single Elton John song in your life, you’ll probably still enjoy in the very least some breathtaking sequences and all the things that make it stand out creatively from every other biopic. It is a musical first and foremost, and in that regard I just love how fitting it is, too.

But I’ve never had the fortune of seeing a musical live show, so as far as some people are concerned I’m not a real musical person. :/

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interview with Mark A. Vieira, author of Forbidden Hollywood: The Pre-Code Era (1930-1934)

Mark A. Vieira is an acclaimed film historian, writer and photographer. His most recent book, Forbidden Hollywood: The Pre-Code Era (1930-1934): When Sin Ruled the Movies is now available from TCM and Running Press.

Raquel Stecher: Twenty years ago you wrote Sin in Soft Focus: Pre-Code Hollywood for Harry N. Abrams. Why did you decide to revisit the pre-Code era with your new TCM-Running Press book Forbidden Hollywood?

Mark A. Vieira: That’s a good question, Raquel. There were three reasons. First, Sin in Soft Focus had gone out of print, and copies were fetching high prices on eBay and AbeBooks. Second, the book was being used in classes at the USC School of Cinematic Arts. Third, Jeff Mantor of Larry Edmunds Cinema Book Shop told me that his customers were asking if I could do a follow-up to the 1999 book, which had gotten a good New York Times review and gone into a second printing. So I wrote a book proposal, citing all the discoveries I’d made since the first book. This is what happens when you write a book; information keeps coming for years after you publish it, and you want to share that new information. Sin in Soft Focus: Pre-Code Hollywood told the story of the Code from an industry standpoint. Forbidden Hollywood has that, but it also has the audience’s point of view. After all, a grassroots movement forced Hollywood to reconstitute the Code.

Raquel Stecher: Forbidden Hollywood includes reproduced images from the pre-Code era and early film history. How did you curate these images and what were your criteria for including a particular photograph?

Mark A. Vieira: The text suggests what image should be placed on a page or on succeeding pages. Readers wonder what Jason Joy looked like or what was so scandalous about CALL HER SAVAGE (’32), so I have to show them. But I can’t put just any picture on the page, especially to illustrate a well-known film. My readers own film books and look at Hollywood photos on the Internet. I have to find a photo that they haven’t seen. It has to be in mint condition because Running Press’s reproduction quality is so good. The image has to be arresting, a photo that is worthy in its own right, powerfully composed and beautifully lit—not just a “representative” photo from a pre-Code film. It also has to work with the other photos on that page or on the next page, in terms of composition, tone and theme. That’s what people liked about Sin in Soft Focus. It had sections that were like rooms in a museum or gallery, where each grouping worked on several levels. In Forbidden Hollywood, I’m going for a different effect. The photo choices and groupings give a feeling of movement, a dynamic affect. In this one, the pictures jump off the page.

Raquel Stecher: Why did you decide on a coffee table art book style format?

Mark A. Vieira: Movies are made of images. Sexy images dominated pre-Code. To tell the story properly, you have to show those images. Movie stills in the pre-Code era were shot with 8x10 view cameras. The quality of those big negatives is ideal for a fine-art volume. And film fans know the artistry of the Hollywood photographers of that era: Fred Archer, Milton Brown, William Walling, Bert Longworth, Clarence Bull, Ernest Bachrach and George Hurrell. They’re all represented—and credited—in Forbidden Hollywood.

Raquel Stecher: What was the research process like for Forbidden Hollywood?

Mark A. Vieira: I started at the University of Southern California, where I studied film 40 years ago. I sat down with Ned Comstock, the Senior Library Assistant, and mapped out a plan. USC has scripts from MGM, Universal and the Fox Film Corporation. The Academy Library has files from the Production Code Administration. I viewed DVDs and 16mm prints from my collection. I reviewed books on the Code by Thomas Doherty and other scholars. I jumped into the trade magazines of the period using the Media History Digital Library online. I created a file folder for each film of the era. It’s like detective work. It’s tedious—until it gets exciting.

Raquel Stecher: How does pre-Code differ from other film genres?

Mark A. Vieira: Well, pre-Code is not a genre like Westerns or musicals. It’s a rediscovered element of film history. It was named in retrospect, like film noir, but unlike film noir, pre-Code has lines of demarcation—March 1930 through June 1934—the four-year period before the Production Code was strengthened and enforced. When Mae West made I’M NO ANGEL (’33), she had no idea she was making a pre-Code movie. The pre-Code tag came later, when scholars realized that these films shared a time, a place and an attitude. There was a Code from 1930 on, but the studios negotiated with it, bypassed it or just plain ignored it, making movies that were irreverent and sexy. Modern viewers say, “I’ve never seen that in an old Hollywood movie!” This spree came to an end in 1934, when a Catholic-led boycott forced Hollywood to reconstitute the Code. It was administered for 20 years by Joseph Breen, so pre-Code is really pre-Breen.

Raquel Stecher: What are a few pre-Code films that you believe defined the era?

Mark A. Vieira: That question has popped up repeatedly since I wrote Sin in Soft Focus, so I decided which films had led to the reconstituted Code, and I gave them their own chapters. To qualify for that status, a film had to meet these standards: (1) They were adapted from proscribed books or plays; (2) They were widely seen; (3) They were attacked in the press; (4) They were heavily cut by the state or local boards; (5) They were banned in states, territories or entire countries; and (6) They were condemned in the Catholic Press and by the Legion of Decency. To name the most controversial: THE COCK-EYED WORLD (’29) (off-color dialogue); THE DIVORCEE (’30) (the first film to challenge the Code); FRANKENSTEIN (’31) (horror); SCARFACE (’32) (gang violence); RED-HEADED WOMAN (’32) (an unrepentant homewrecker); and CALL HER SAVAGE (’32) (the pre-Code film that manages to violate every prohibition of the Code). My big discovery was THE SIGN OF THE CROSS (’32). This Cecil B. DeMille epic showed the excesses of ancient Rome in such lurid detail that it offended Catholic filmgoers, thus setting off the so-called “Catholic Crusade.”

Raquel Stecher: It’s fascinating to read correspondence, interviews and reviews that react to the perceived immorality of these movies. How does including these conversations give your readers context about the pre-Code era?

Mark A. Vieira: Like some film noir scholars, I could tell you how I feel about the film, what it means, the significance of its themes. So what? Those are opinions. My readers deserve facts. Those can only come from documents of the period: letters, memos, contracts, news articles. These are the voices of the era, the voices of history. A 100-year-old person might misremember what happened. A document doesn’t misremember. It tells the tale. My task is to present a balanced selection of these documents so as not to stack the deck in favor of one side or the other.

Raquel Stecher: In your book you discuss the attempts made to censor movies from state and federal government regulation to the creation of the MPPDA to the involvement of key figures like Joseph Breen and Will H. Hays. What is the biggest misconception about the Production Code?

Mark A. Vieira: There are a number of misconceptions. I label them and counter them: (1) “Silent films are not “pre-Code films.” (2) Not every pre-Code film was a low-budget shocker but made with integrity and artistry; most were big-budget star vehicles. (3) The pre-Code censorship agency was the SRC (Studio Relations Committee), part of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors Association (MPPDA)—not the MPPA, which did not exist until the 1960s! (4) The Code did not mandate separate beds for married couples. (5) Joseph Breen was not a lifelong anti-Semite, second only to Hitler. He ended his long career with the respect and affection of his Jewish colleagues.

Raquel Stecher: How did the silent movie era and the Great Depression have an impact on the pre-Code era?

Mark A. Vieira: The silent era allowed the studios the freedom to show nudity and to write sexy intertitles, but the local censors cut those elements from release prints, costing the studios a lot of money, which in part led to the 1930 Code. The Great Depression emptied the theaters (or closed them), so producers used sexy films to lure filmgoers back to the theaters.

Raquel Stecher: TCM viewers love pre-Codes. What do you think it is about movies from several decades ago that still speak to contemporary audiences?

Mark A. Vieira: You’re right. Because we can see these films so readily, we forget that eight decades have passed since they premiered. We don’t listen to music of such a distant time, so how can we enjoy the art of a period in which community standards were so different from what they are now? After all, this was the tail end of the Victorian era, and the term “sex” was not used in polite society. How did it get into films like MIDNIGHT MARY (’33) and SEARCH FOR BEAUTY (’34)? There were protests against such films, and there were also millions of people enjoying them. What they enjoyed is what TCM viewers enjoy—frankness, honesty, risqué humor, beautiful bodies and adult-themed stories.

Raquel Stecher: What do you hope readers take away from your book?

Mark A. Vieira: One thing struck me as I wove the letters of just plain citizens into the tapestry of this story. Americans of the 1930s wrote articulate, heartfelt letters. One can only assume that these people were well educated and that they did a lot of reading—and letter writing. I want my readers to read the entire text of Forbidden Hollywood. I worked to make it accurate, suspenseful and funny. There are episodes in it that are hilarious. These people were witty! So I hope you’ll enjoy the pictures, but more so that you’ll dive into the story and let it carry you along. Here’s a quote about SO THIS IS AFRICA (‘33) from a theater owner: “I played it to adults only (over 15 years old). Kids who have been 12 for the last 10 years aged rapidly on their way to our box office.”

#pre-Code#TCM#Forbidden Hollywood#pre-code films#interview#jean harlow#mae west#ginger rogers#Depression era#1930s#Raquel Stecher

255 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today would be Marilyn’s 93rd Birthday, she has been in my life for almost a decade and I still find it so surreal to think that in theory, she should still be here. Sadly, we all know that is not the case and the reality is that Marilyn left the world over fifty five years ago. It’s sometimes hard to comprehend that Marilyn wasn’t just a Hollywood Star but a human being, just like you and me. However, today is not for dwelling, it is a very important day to millions of fans and myself, as the worlds Brightest Star is ultimately still shining half a century later!

Marilyn photographed by Ed Cronenweth in 1948.

To celebrate Marilyn’s big day, I usually spend it in the best way I know possible, having a Movie Marathon watching my favourite Actress. Unfortunately, so many people see Marilyn as just another silly Blonde Bombshell who didn’t have much talent and was basically playing herself on the screen. However, I can’t emphasize enough that the sweet, lovable, pretty face was so much more than what people perceive. As someone who has watched her films a countless number of times, I actually appreciate her comedic performances over her dramatic ones. This is because people tend to view dramas with more acclaim and respect and the Award Shows further prove this, when in fact comedies should not be overlooked.

In the wise words of Vivien Leigh – an Actress who yes, was more respected critically than Marilyn, but, ultimately was more appreciated more for her looks too,

“Comedy is much more difficult than tragedy – and a much better training, I think. It’s much easier to make people cry than to make them laugh.”

Marilyn photographed on Tobey Beach by Andre de Dienes on July 23rd 1949.

Marilyn was incredibly dedicated to her craft and spent numerous hours educating herself on the Performing Arts and trying to be the best she could possibly be. When you learn about Marilyn you realize how much she suffered mentally and the strength she must have found to deliver such beautiful performances. It hurts to think that she didn’t always feel like the bubbly Blonde Bombshell so many know and love her for, as no one more than Marilyn deserved to be appreciated and loved. She was such a perfectionist and would spend hours analyzing and being critical of her acting abilities and performance in each film.

“We not only want to be good, we have to be. You know, when they talk about nervousness, my teacher, Lee Strasberg, when I said to him, “I don’t know what’s wrong with me but I’m a little nervous,” he said, “When you’re not, give up, because nervousness indicates sensitivity.” Also, a struggle with shyness is in every actor more than anyone can imagine. There is a censor inside us that says to what degree do we let go, like a child playing. I guess people think we just go out there, and you know, that’s all we do. Just do it. But it’s a real struggle. I’m one of the world’s most self-conscious people. I really have to struggle.”

– Marilyn to Journalist Richard Meryman for LIFE Magazine, published on August 17th 1962.

Marilyn attending a Court Hearing on June 26th 1952.

Therefore, I thought it would be appropriate to choose five of Marilyn’s films in which she believed she gave the best performances or received great critical acclaim, to recommend for others to watch. If there is any day that Marilyn should be celebrated (personally, I believe it’s all day every day) than it is on her Birthday.

Whilst looking through reviews of Marilyn’s films that were published during their original releases, it’s shocking to me to read the downright prejudice, sexism and ignorance surrounding her as an Actress. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again, in my belief Marilyn was the greatest Actress of all time as it seems that even then, 99% of people believed she was just playing herself. Therefore, in believing their own ignorance, critics could continue their lack of acclaim and respect for ultimately, an extremely talented woman.

Marilyn photographed by Milton Greene in June 1955.

• The Asphalt Jungle (1950) and The Seven Year Itch (1955)

Person to Person television appearance interview on April 8th 1955.

“Marilyn, what’s the best part you ever had in a movie?” – Edward R. Murrow

“Well one of the best parts I’ve ever had was, in The Asphalt Jungle, John Huston’s Picture and then, The Seven Year Itch, Billy Wilder’s Picture.” – Marilyn

“You think that’s going to be a big one too, don’t you? The Seven Year Itch.” – Edward R. Murrow

“I think it will be a very good Picture and I would like to continue making this type of Picture.” – Marilyn

Dallas Morning News Review by Harold Hefferman published on June 18th 1950.

“Virtually unbilled and unidentified in a current movie, Asphalt Jungle, Marilyn’s breathtaking appearance immediately piques fandom’s curiosity and imagination. Not since the brief introduction of another tempestuous blond, Shelley Winters, three years ago in A Double Life, has a newcomer stirred up so much interest.”

Marilyn photographed by Earl Leaf at a Press Party held for Bus Stop on March 3rd 1956.

• Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953)

LIFE Magazine Interview with Journalist Richard Meryman published on August 17th 1962.

“I remember when I got the part in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Jane Russell – she was the brunette in it and I was the blonde. She got $200,000 for it, and I got my $500 a week, but that to me was, you know, considerable. She, by the way, was quite wonderful to me. The only thing was I couldn’t get a dressing room. Finally, I really got to this kind of level and I said, “Look, after all, I am the blonde, and it is Gentlemen Prefer Blondes!” Because still they always kept saying, “Remember, you’re not a star.” I said, “Well, whatever I am, I am the blonde!” – Marilyn

The Los Angeles Times Review by Edwin Schallert on August 1st 1953.

“Miss Monroe sparkles much of the time just as the diamonds do. Her work is insidiously intriguing in this picture, and at the same time almost childlike in its utter lack of guile. Her portrayal demonstrates that much may be maneuvered in her instance in the future to humorous advantage. She discloses a surprising light comedy touch.”

Time Magazine Review on July 27th 1953.

“As Lorelei Lee, who believes that diamonds are a girl’s best friend, Marilyn Monroe does the best job of her short career to date. [She] sings remarkably well, dances, or rather undulates all over, flutters the heaviest eyelids in show business and breathlessly delivers such lines of dialogue as, “Coupons – that’s almost like money,” as if she were in the throes of a grand passion.”

Marilyn photographed by Sam Shaw in the Summer of 1957.

• Bus Stop (1956)

Speaking to reporters upon her arrival back in Hollywood to film Bus Stop, on February 25th 1956.

“Marilyn, are you happy to come back and do this Picture, are you pleased with the Bus- Picture Bus Stop?” – Reporter

“Oh yes, very much, I’m looking forward to working with Josh Logan, doing the Picture and it’s good to be back.” – Marilyn

“Was he in your selection as a Director?” – Reporter

“Twentieth Century Fox selected him and I have Director Approval and they asked if I would approve of him and definitely.” – Marilyn

“So you’re very happy, you think you’re going to make a very good Picture?” – Reporter

“I hope we do make a good picture, yes.” – Marilyn

The New York Times Review by Bosley Crowther published on September 1st 1956.

“HOLD onto your chairs, everybody, and get set for a rattling surprise. Marilyn Monroe has finally proved herself an actress in “Bus Stop.” She and the picture are swell!”

Marilyn in Let’s Make Love in 1960.

• Some Like It Hot (1959)

Variety Film Review published on February 24th 1959.

“To coin a phrase, Marilyn has never looked better. Her performance as “Sugar,” the fuzzy blonde who likes saxophone players “and men with glasses” has a deliciously naive quality. She’s a comedienne with that combination of sex appeal and timing that just can’t be beat.”

The New York Times Review by A. H. Weiler published on March 30th 1959.

“As the hand’s somewhat simple singer-ukulele player, Miss Monroe, whose figure simply cannot be overlooked, contributes more assets than the obvious ones to this madcap romp. As a pushover for gin and the tonic effect of saxophone players, she sings a couple of whispery old numbers (“Running Wild” and “I Wanna Be Loved by You”) and also proves to be the epitome of a dumb blonde and a talented comedienne.”

Marilyn photographed by Bert Stern in June 1962.

I hope however you choose to spend this day, you take a moment to think about Marilyn and in her own words, hold a good thought for her as if anyone deserved that, it was she.

“I Love Marilyn” by Sidney Skolsky published in Modern Screen Magazine in October 1953.

“Before the picture flashed on the screen, Marilyn whispered to me in that low, sexy voice that is natural with her: “Hold a good thought for me.” She always says that when embarking on an venture. She feels much better when you tell her you will.”

Follow me at;

BLOGLOVIN

INSTAGRAM

TUMBLR

TWITTER

YOUTUBE

For inquiries or collaborations contact me at;

Happy 93rd Birthday Marilyn! Today would be Marilyn's 93rd Birthday, she has been in my life for almost a decade and I still find it so surreal to think that in theory, she should still be here.

#1940s#1950s#1960s#blonde bombshell#classic hollywood#marilyn#marilyn monroe#monroe#norma jeane#norma jeane baker#old hollywood#retro#vintage

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

once i saw christian borle getting coffee

#i was going to see a show??? i think it was h*milton#so he was in something rotten then i think?? probably just going by facial hair#my only celebrity encounter besides bumping into emily mortimer when i was like 3#nyc is not rly that exciting for me celebrity wise tbh#anyways it was awesome. remember when christian borle had hair cause i fucken do#i saw falsettos in theaters(and it fucking rocked i cried rly hard) and like 5% of my sadness was looking at when his hair was alive and wel#*well#i mean hair is dead you know what i mean.#also i just now watched the legally blonde mtv recording and i rly liked it??? a lot of stuff the movie does better#but they did emmett rly well and it's rly catchy and i enjoyed it! some parts felt rushed or dragging but w/e u know#and the two marvins im Shook#also cause this turned into a musical theater rant there was a spring awakening production w high schoolers i went to and it was very good!!#mama who bore me reprise goes so fucking hard dude#im listening to fun home next#also recently ive revisited you're a good man Charlie Brown and it's so comforting to me fr some reason#the Christian borle thing was like. 2015 fyi#im gonna stop talking now#audrey.txt

0 notes

Text

123Movies-WaTcH Demon Slayer Mugen Train 2020 Online Full

05 sec ago Don't miss!~{OFFICIAL-NETFLIX}~!How to Watch Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train Online Free? [DVD-ENGLISH] Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train (2020) Full Movie Online Free HQ [DvdRip-USA Eng-Sub] Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train (2020) Google Drive. Watch Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train Online Free 123 movies || Watch Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train Online (2020) Full Movie Free 4KHD. Watch Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train Online (2020) Full Movies Free HD Putclokers || Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train (2020) with English Subtitles ready for Download, Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train (2020) 720p, 1080p, BrRip, DvdRip, High Quality. ========================================== Streamnow

▶ http://play.sensationfilms.xyz/en/movie/635302/demon-slayer-a-kimetsu-no-yaibaa-the-movie-mugen-train ========================================== Title : Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train Release : 2020-10-16 Rating : 8/10 by 546 Runtime : 117 min. Companies : ufotable Country : Japan Language : English, æ¥æ¬èª Genre : Animation, Action, Adventure, Fantasy, Drama Stars : Natsuki Hanae, Akari Kito, Hiro Shimono, Yoshitsugu Matsuoka, Satoshi Hino, Takahiro Sakurai Overview : TanjirÅ Kamado, joined with Inosuke Hashibira, a boy raised by boars who wears a boar's head, and Zenitsu Agatsuma, a scared boy who reveals his true power when he sleeps, boards the Infinity Train on a new mission with the Fire Hashira, KyÅjurÅ Rengoku, to defeat a demon who has been tormenting the people and killing the demon slayers who oppose it! Watch Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train (2020) Movie WEB-DL This is a file losslessly ripped from a streaming service, such as Netflix, Amazon Video, Hulu, Crunchyroll, Discovery GO, BBC iPlayer, etc. This is also a movie or TV show downloaded via an online distribution website, such as iTunes. The quality is quite good since they are not re-encoded. The video (H.264 or H.265) and audio Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train streams are usually extracted from the iTunes or Amazon Video and then remuxed into a MKV container without sacrificing quality. Download Movie Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train One of the movie streaming industry’s largest impacts has been on the DVD industry, which effectively met its demise with the mass popularization of online content. The rise of media streaming has caused the downfall of many DVD rental companies such as Blockbuster. In July 2019 an article from the New York Times published an article about Netflix’s DVD services. It stated that Netflix is continuing their DVD services with 5.3 million subscribers, which is a significant drop from the previous year. On the other hand, their streaming services have 65 million members. In a March (2020) study assessing the “Impact of Movie Streaming over traditional DVD Movie Rental” it was found that respondents do not purchase DVD movies nearly as much anymore, if ever, as streaming has taken over the market. Watch Movie Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train , viewers did not find movie quality to be significantly different between DVD and online streaming. Issues that respondents believed needed improvement with movie streaming included functions of fast forwarding or rewinding, as well as search functions. The article highlights that the quality of movie streaming as an industry will only increase in time, as advertising revenue continues to soar on a yearly basis throughout the industry, providing incentive for quality content production. Watch Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train Movie Online Blu-ray or Bluray rips are encoded directly from the Blu-ray disc to 1080p or 720p (depending on disc source), and use the x264 codec. They can be ripped from BD25 or BD50 discs (or UHD Blu-ray at higher resolutions). BDRips are from a Blu-ray disc and encoded to a lower resolution from its source (i.e. 1080p to 720p/576p/480p). A BRRip is an already encoded video at an HD resolution (usually 1080p) that is then transcoded to a SD resolution. Watch Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train Movie BD/BRRip in DVDRip resolution looks better, regardless, because the encode is from a higher quality source. BRRips are only from an HD resolution to a SD resolution whereas BDRips can go from 2160p to 1080p, etc as long as they go downward in resolution of the source disc. Watch Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train Movie FullBDRip is not a transcode and can fluxate downward for encoding, but BRRip can only go down to SD resolutions as they are transcoded. BD/BRRips in DVDRip resolutions can vary between XviD or x264 codecs (commonly 700 MB and 1.5 GB in size as well as larger DVD5 or DVD9: 4.5 GB or 8.4GB), size fluctuates depending on length and quality of releases, but the higher the size the more likely they use the x264 codec. ❍❍❍ TV MOVIE ❍❍❍ The first television shows were experimental, sporadic broadcasts viewable only within a very short range from the broadcast tower starting in the 1930s. Televised events such as the 1936 Summer Olympics in Germany, the 19340 coronation of King George VI in the UK, and David Sarnoff’s famous introduction at the 1939 New York World’s Fair in the US spurred a growth in the medium, but World War II put a halt to development until after the war. The 19440 World MOVIE inspired many Americans to buy their first television set and then in 1948, the popular radio show Texaco Star Theater made the move and became the first weekly televised variety show, earning host Milton Berle the name “Mr Television” and demonstrating that the medium was a stable, modern form of entertainment which could attract advertisers. The first national live television broadcast in the US took place on September 4, 1951 when President Harry Truman’s speech at the Japanese Peace Treaty Conference in San Francisco was transmitted over AT&T’s transcontinental cable and microwave radio relay system to broadcast stations in local markets. The first national color broadcast (the 1954 Tournament of Roses Parade) in the US occurred on January 1, 1954. During the following ten years most network broadcasts, and nearly all local programming, continued to be in black-and-white. A color transition was announced for the fall of 1965, during which over half of all network prime-time programming would be broadcast in color. The first all-color prime-time season came just one year later. In 19402, the last holdout among daytime network shows converted to color, resulting in the first completely all-color network season. ❍❍❍ Formats and Genres ❍❍❍ See also: List of genres § Film and television formats and genres Television shows are more varied than most other forms of media due to the wide variety of formats and genres that can be presented. A show may be fictional (as in comedies and dramas), or non-fictional (as in documentary, news, and reality television). It may be topical (as in the case of a local newscast and some made-for-television films), or historical (as in the case of many documentaries and fictional MOVIE). They could be primarily instructional or educational, or entertaining as is the case in situation comedy and game shows.[citation needed] A drama program usually features a set of actors playing characters in a historical or contemporary setting. The program follows their lives and adventures. Before the (2020)s, shows (except for soap opera-type serials) typically remained static without story arcs, and the main characters and premise changed little.[citation needed] If some change happened to the characters’ lives during the episode, it was usually undone by the end. Because of this, the episodes could be broadcast in any order.[citation needed] Since the (2020)s, many MOVIE feature progressive change in the plot, the characters, or both. For instance, Hill Street Blues and St. Elsewhere were two of the first American prime time drama television MOVIE to have this kind of dramatic structure,[4][better source needed] while the later MOVIE Babylon 5 further exemplifies such structure in that it had a predetermined story running over its intended five-season run.[citation needed] In 2022, it was reported that television was growing into a larger component of major media companies’ revenues than film.[5] Some also noted the increase in quality of some television programs. In 2022, Academy-Award-winning film director Steven Soderbergh, commenting on ambiguity and complexity of character and narrative, stated: “I think those qualities are now being seen on television and that people who want to see stories that have those kinds of qualities are watching television. ❍❍❍ Thank’s For All And Happy Watching❍❍❍ Find all the movies that you can stream online, including those that were screened this week. If you are wondering what you can watch on this website, then you should know that it covers genres that include crime, Science, Fi-Fi, action, romance, thriller, Comedy, drama and Anime Movie. Thank you very much. We tell everyone who is happy to receive us as news or information about this year’s film schedule and how you watch your favorite films. Hopefully we can become the best partner for you in finding recommendations for your favorite movies. That’s all from us, greetings! Thanks for watching The Video Today. I hope you enjoy the videos that I share. Give a thumbs up, like, or share if you enjoy what we’ve shared so that we more excited. Sprinkle cheerful smile so that the world back in a variety of colors. Download Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train (2020) Full Movies Watch Online Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train (2020) Full Movie Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train (2020) Full Full Movie Watch Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train (2020) Full English Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train (2020) Full Film Online Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train (2020) Full Movie Stream Free Watch Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train (2020) Full Movie Subtitle English Watch Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train (2020) Full Movie spoiler Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train (2020) Full Movie Tamil Watch Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train (2020) Full Movie Telugu Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train (2020) Full Movie vimeo Watch Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train (2020) Full Moviedaily Motion Regarder Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train (2020) Film Complet Ver Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train (2020) Film Completo

1 note

·

View note

Text

‘Spellbound: All Hallow’s Eve’ Chapter 2: Can’t Shake This Feeling

“H-how the bloody hell did you do that!?” Lestrade asked in a panic.

“You’ve had too much to drink,” was Sherlock’s reply.

“Sherlock!” Molly scolded him.

“I’m gonna need a drink,” replied the detective inspector.

“You won’t believe us even if we told you,” Sherlock continued, hoping Greg would just decide that ignorance is bliss.

“After seeing a dead man sit up, I think I’d believe anything at this point,” Greg pointed out.

“He’s right, darling,” Molly agreed.

“Oh, very well. You can explain it more gently than I.”

Lestrade listened closely to what he was being told. If anything, it made sense to him that his friends were a witch and a werewolf. It definitely explained why Sherlock refused to takes cases during a full moon. Molly told him the entire tale of their séance with Moriarty’s ghost and Irene’s vampiric nature.

“A murderous ghost…that’s a new one,” Greg laughed nervously. “A perfect crime if ever I heard of one.”

“You won’t say anything, right?” Molly’s worried expression was plain as the nose on her face.

“Betray you two? I’d sooner spend the day with Anderson,” he assured them.

“And that’s when you know he means it,” Sherlock remarked, rather amused.

Later that night, Molly was in a fitful sleep. She tossed and turned countless times, unable to rid herself of the nightmare. Horrifying images plagued her mind; nails painted crimson red, a woman strangled in a back alley, and Sherlock bleeding just below his naval. A man’s bone-chilling laugh could be heard during the latter image.

Sherlock woke to the sound of his wife’s scream, thoroughly surprised it didn’t wake Victoria.

“Molly, wake up,” he urged her. “Look at me; it’s just a nightmare.”

“Sherlock,” she breathed heavily. “You’re okay. Oh thank God you’re okay.”

“Of course I’m okay, why wouldn’t I be?” He took her hand in his, immediately chilling him. “You’re ice cold. What’s happened?”

“I-I think I had a vision,” she admitted.

“Of the future?” he asked.

“I assume so, though I hope that last one never happens.” Her voice was tremulous at this point.

“Tell me; maybe it can be prevented,” Sherlock assured her.

“You were lying on the ground; cold concrete,” she began. “You were bleeding from below your naval. While not entirely fatal, it would’ve needed medical attention quickly.”

“Is there anything else you remember?”

“A man’s laugh; it was so malicious, it chilled me to the bone,” Molly told him. “I’ve no idea what it means other than you’re in danger. Before that, I saw crimson nails, and a strangled woman in a back alley of London.”

Wrapping his arms around her, Sherlock comforted his wife as best as he could. Molly clung onto him, welcoming his embrace.

“What are we going to do?” she trembled.

“There isn’t much we can do at the moment,” he pointed out. “But we should at least tell John and Mary.” He pressed a kiss into her hair. “After all, Mary is in your coven. We’ll have more power on our side than we did last time.”

Molly agreed. It was the most logical thing to do, of course. She settled comfortably in his arms, eventually lulled to sleep by her husband singing softly to her just as he did for Victoria. Tomorrow, they’d tell their friends what to look out for.

She followed a man to Leinster Gardens, keeping far enough away as to go unnoticed, but close enough to not lose the trail. Her light brown eyes kept an eye through the veil, watching as the adulterous husband searched for his mistress. Oh, he believed it to be another secret meeting, but never considered it was the night he’d meet his doom.

‘It’s time,’ she thought with a sinister satisfaction.

“Who’s there?” The man called out. “I demand you show yourself at once!”

That’s when the singing began. It was too soft to make out the words, but it was alarming enough to send chills up his spine. Feeling breath on the back of his neck, he turned around slowly.

“You broke your vows,” she whispered, raising her dagger high.

“Stay away!” he shouted.

A light turned on, distracting them both. When the man turned back to face her, she had disappeared.

Mary Watson set down Molly’s cup of tea. John and Sherlock had been called in by Greg to take a look at the murder scene of Gwendoline Beauchamp, who had been strangled with nothing other than gloved hands.

“You’re more experienced, Mary…there’s gotta be something I can do to prevent my vision,” Molly fretted. “The crimson nails probably belong to the murderer of Milton, and now this strangled woman I saw in my nightmare.”

“I’m sorry, poppet, but there’s nothing more to be done. The visions aren’t there for us to prevent them; only to help prepare us for what’s to come,” Mary informed her sympathetically.

The sound of squealing, happy babies averted their attention momentarily. Rosie and Victoria were keeping themselves occupied in the playpen.

“The best you can do is making sure you’re always prepared at a moment’s notice if Sherlock should ever meet his fate in your vision,” Mary continued. “I wish I could do more, but the most I can offer is helping you with a tracking spell once we find out who has a vendetta against Sherlock.”

“Mary, there’s so many people it could be,” Molly pointed out. “I could probably write up pages of names.”

“Well, supernaturally speaking, is there anyone who may want to avenge Moriarty or Irene?” she inquired.

“Kate was Irene’s closest ally, but only because she had been sired by her,” Molly explained. “As for Moriarty…it could be anyone. He never let on who his allies were.”

“I’ve got an idea,” Mary smirked.

Molly couldn’t get a word out before her friend began setting out vials and a couple of herbs.

“This should help you focus your mind and allow you to control what your next vision shows you,” Mary explained.

“How very useful,” Molly remarked, her burden lifting off her ever so slightly. “Yes, this should be perfect.”

Fingers drummed against the shabby wooden table in the old warehouse.

“About time you showed up,” remarked a man with a slight Irish accent.

The man who had just entered to warehouse stood for a moment in silence before tossing his gun on the torn sofa.

“Bad time at the club?” the Irishman asked.

“Was caught cheating and this hotshot—Adair—threatened to expose me,” he replied.

“So, what’d you do then?”

“What I’m good at—I killed ‘im.”

“Ah, well. I do hope you were conspicuous. Holmes is onto us, Sebastian.”

FFN | AO3 | Buy Me a Coffee?

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

i watched h*athers at the other pal*ce last night and i have Thoughts

first off i actually,,,,,,,, don’t remember that much from off-bway 2014 h*athers cause i haven’t watched it in so long lmao but the most noticeable changes were from blue to a song called you’re welcome. mcnamara and duke are not on stage for that one, they get the car keys and leave veronica stranded w/ kurt & ram. the song is not much better off tbh. it’s even more uncomfortable but in a more predatory way i guess so it highlights how she’s....... literally about to be raped but there are still some jokes??? and it’s........ not the time to expect laughter like idk it personally made me very uncomfortable. and yEAH it’s supposed to make u uncomfortable ofc but then they’re throwing in jokes and it’s like friends we had this problem 4 years ago can we. not.

they added a song for he*ther d*ke which i was soooooo excited about!! look. i didn’t love the song. maybe if i listen to it more i’ll get into it but i feel like it was just this huge spectacle and kinda thrown in and also there’s this part where she rips the green costume off and reveals chandler’s red one. despite not loving the song, t’shan KILLED IT and i’m still not over her tbh lmao she was my fave part of the show last night i think. aLsO it added a biiiit more to the character since before she was mostly treated like a villain and now we see a girl who just Really wants to be liked and suffered substantial abuse from her “best friend” and now is just kind of....... free.

they kept d*ad g*y s*n which like. disappointed but not surprised.

the cast

c*rrie h*pe fl*tch*r as veronica - i’d listened to a couple of audios of her before and i wasn’t too happy that they’d removed veronica’s high notes but watching it live, it didn’t seem like a huge problem at all tbh. she was an amazing veronica and definitely has very powerful vocals but in my opinion she wasn’t particularly memorable tbh?? i just don’t feel like she was really able to make the character her own and a lot of it felt very derived from barrett but that’s just me.

j*mie m*sc*to as jd - i actually really liked his jd!! he had the look dOWN. he started out maybe a bit more cute-sy and hesitant (like, almost told veronica she had the wrong cup when she gave chandler the bleach & was almost kinda shocked like ‘oh shit i killed someone’) but grew veeeery dark and manic and manipulative and was revelling in moments like after d*ad g*y s*n and sh*ne a l*ght and was always like ‘ok who we gonna kill next!!!’ and was very creepy in general though the musical did prompt you to feel bad for people like him as well as kurt and ram which. it shouldn’t & i don’t bye!

- like quick lil note i understand veronica is in distress but i hate how she sings that they could’ve turned out good when they aLMOST RAPED HER like they didn’t deserve to die but come on!!

j*die st*ele as he*ther c - mixed feelings for this one tbh. i didn’t love her, i’ll start by saying that. her voice is definitely very powerful and very fit for the character, but i feel like she played everything as more comical than anything else and some of her meaner moments felt a bit forced. but she was absolutely hilarious in the me ins*de of me and all the other moments after she died lol. not my favorite but she wasn’t bad either. did have some more memorable little moments like her dance in me ins*de of me was gOLD.

t’sh*n will*ms as he*ther d - i!!! stan!!! i think she was my fave he*ther d tbh??? she’s a fucking powerhouse and she made the character pretty sympathetic, especially towards the end. looked genuinely concerned when she said v looked like hell. in the finale she just stands there kinda grumpy and doesn’t sing along but then veronica insists for like a solid ten seconds and she joins in, still not sure if she quite belongs, very hesitant, but with the cUTEST small lil smile and she gives martha this little wave i cRIED.

s*phie is*acs as he*ther mc - again, she was very good, but i didn’t find her particularly memorable. like, to me, lifeboat just kind of flew by and her almost suicide scene as well and i didn’t feel too much??? her voice is definitely very pretty and she’s a good actress but i think the performance fell a bit flat for me.

a few more lil notes!!

- costumes were fine but i gotta say i was not a fan of he*ther m’s skirt or jd’s trench coat

- the stage was very small but the set felt so big at the same time?? and the set was very pretty tbh i really liked it!!

- sh*ne a l*ght was hILARIOUS and r*becca l*ck was great and being vv interactive and pointing to the guy at the audience and being like ‘you brought your wife aND A KID????’ and the wife was living and the guy was dying

- i feel like some jokes didn’t work w/ the british audience as it happens lmao like when ms fl*ming was like ‘as my thesis from berkley says’ and there were like, two laughs, one from me. in brazil we usually translate these kinds of things but i get why they didn’t. makes me wonder how h*milton is working out here tbh lol.

- dominic & chris were on point as kurt & ram (def reminded me of all the dudebros i know) but i just feel a bit iffy about the whole kram thing and everyone...... you know........ forgetting they almost raped veronica.

- huuuuuuge props to the ensemble. it was very small but they nailed it and the ensemble numbers were just always filled with energy and a lot of fun!!

- also props to the cast’s american accents!! they did slip at times but they fooled the friends i’d taken with me who were all surprised to find out the cast was actually british.

- i hate paying for programmes. not a note for the show but one from me to this country. i know they fancier than playbills but we have similar ones in brazil and they’re free!! 4 pounds doesn’t seem like much. until you remember that’s twenty reais. TWENTY!!

- there wasn’t really a stage door, the actors showed up at the lobby, but there was a line that went all the way outside the theatre and i am now Old and no longer have the patience for these types of things so i just left.

- sooooooo many people went dressed up though so if you’re in doubt about whether or not you should i’d say go for it.

- overall it was a good show, definitely fun, didn’t really leave me in emotional shambles but maybe i’m just older & boring now. i’m glad they’re still trying things out and making changes because lemme tell you it needs some of those. but if you’re in london, i def recommend watching it if it’s your type of show (though i know it’s not everyone’s cup of tea), it was a fun experience (love me some h*athers themed drinks) and i don’t think you’ll regret it!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay friends, here we go: Coldflash North & South AU

(If any of you are unfamiliar, I HIGHLY recommend watching this. Especially the 2004 version with Richard Armitage, which is the one I’ve seen. Good stuff.)

Mid 1800′s, Victorian England. Barry Allen is living a perfectly tranquil life in the south of England. It’s the most idyllic type of lifestyle. His best friend, Iris, has just gotten married to the love of her life, Eddie Thawne, and Barry couldn’t be happier for them. He, himself, isn’t married, and he had pined after Iris for some time, but he’s glad to see her happy, and he’s started to move on.

But then his father decides to uproot them from their happy life and move north.

Henry is a doctor, but he’s become disenchanted with the field, with some of the new outlooks on morality that some of his younger companions have begun to adopt. On principle, he decided to leave, taking his family to the industrial town of Milton, where he can continue his practice on his own terms, and he can tutor privately, teaching about culture and literature that he learned while studying at Oxford.

Barry hates Milton immediately. The perpetually cloudy skies, the ever-present chill in the air, the way everything about the town looks so run-down and grey. He misses the South - the warmth in the air, the way the sun made everything glow golden like a dream. But he doesn’t want to upset his father, so he helps look for a place for them to live with help from one of his father’s friends from school, Harrison Wells.

Wells is an old family friend who happens to know this town and the people in it, insisting that Barry and his family meet with a friend of his - the owner of the cotton mill, a man named Leonard Snart. Barry agrees, if only because his father asked him to. He’s told to wait in an office, but Barry had never been good with patience, and he wanders into the mill. There, he sees puffs of cotton floating through the sky like snowflakes, as if he’d suddenly set foot in a winter wonderland, if not for the roaring sound of machinery. He can’t help but be captivated by it all, just a little bit, when he hears shouting, sees people running, and he follows.