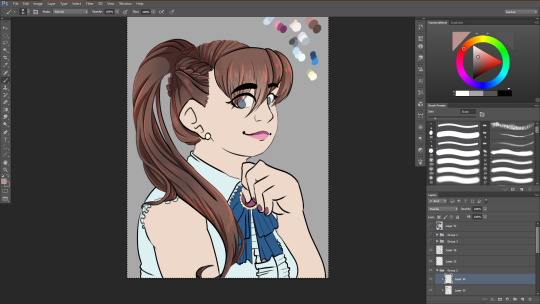

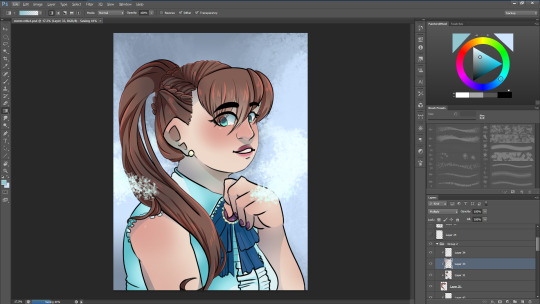

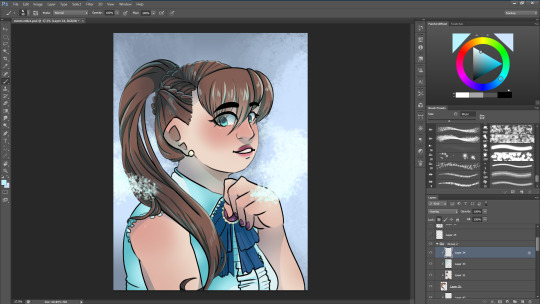

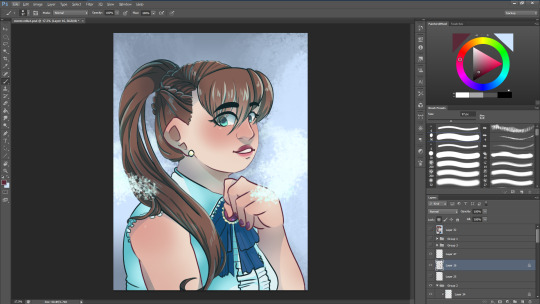

#i wanted to study how to give volume and stylization!!

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#more doodles yayyy#i wanted to study how to give volume and stylization!!#also i just finished seeing avengers the age of ultron and im still in denial ab quicksilvers death like BRO#WHY DID U TAKE HIM OUT HES EVERYTHING#anyway#myart#my art#loner vociferation#me things#mdzs#mo dao zu shi#fanart#jin rulan#jin ling#lan yuan#lan sizhui#sketch#doodle#procreate#expressions#cuties#ok byeee

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Art Advice: The Misconception Behind "Study Realism"

Most people who draw anime/cartoons have, while asking for ways to improve, at one point or another been told to "study realism." A common response to this is, "But I don't want to draw realism!"

But, did you know that the purpose behind this suggestion is NOT so that you draw realism? They're not suggesting you change to a more realistic style. What, then?

Let's look at this through an analogy:

Say you don't know music yet and decide you want to learn how to play the Happy Birthday song. You're not interested in playing anything else, just the HB song, and you haven't started learning anything related to music at this point. OK, that's fine, and now we have our situation set up. Once you've decided this, you set yourself to learning the sequence of notes to the HB song. You practice and practice, and, after a while, you can play it really well without a hitch. After a few years, it starts feeling bland to you, and you ask, "How can I make my HB song better?" And someone tells you, "Learn all the other music notes," and "Study classical and other genres of music." And you reply, "But I don't want to play that type of music; I want to play the HB song!" (And that's FINE! It's valid; it's what you want to do.[*Footnote 1]) But without having learned all the other notes and other types of music, you can't make a remix of the HB song, or an "epic version," or a hip-hop-fusion version; you've capped at the end of the first paragraph of this story.

So drawing anime or cartoons is like playing the HB song, or any one song in our example.

And here's where our misunderstanding comes in:

"Study Realism" DOES NOT MEAN "Draw Realism"

Yes, you'll have to draw it to study it (not only your brain, but also your hand needs to learn the skill), but it doesn't mean that's what all your artwork will look like. It is meant to give you more tools to make your anime and cartoon work stronger, more appealing, and more unique.

How will it do that? The more music notes you know, the more types of music you understand and can play, the more original a remix /version of the Happy Birthday song you'll be able to make - and it will be unique. Because you will be able to take all that diverse knowledge and apply it to your song, making it stand out, and the next time you play the HB song, people will go, "Wow! This is a really cool version!"

So now we can be clear: There is a difference between learning something and performing it. You can perform whatever you choose, but by learning all the things, your performance of your "Thing of Choice" will be stronger.

What, Exactly, Will Studying Realism Teach You, Then?

I. VALUES

If you learn how to paint/shade with a full range of values (by learning realistic shading) that properly depict both volume and lighting, you will have no trouble simplifying that to cel-shading or gradient-shading in your anime or cartoon drawings, because you will at once spot when something is undershaded or the shadows are in the wrong spot.

On the other hand, if you try to do cel- or gradient-shading first, you are way more likely to a) undershade, and b) have an inconsistent light source. And when these things happen, you won't be able to tell *why* your drawing looks "off" or bland.

II. COLOR

By studying realistic coloring, you'll be able to learn how color varies across an item (say, a shirt) that is a "solid color." Example: you're drawing a character with a pink t-shirt, standing in the sun, at the end of the school day. The t-shirt is solid pink, however, the colors on it will vary from orange-ish to purple-gray, with some areas almost a bright red (and that's not even considering items around the shirt that would bounce light back onto the shirt and change its color). But you'll only know this (and how to do it) if you study realistic coloring.

Then you can apply that knowledge to your stylized artwork and make it stand out more.

Painting of a stylized pear, where I studied real pears to understand their coloring and texture. See how studying realism can enhance your cartoon work.

III. MAKE BETTER STYLIZED ANATOMY

By studying and learning realistic anatomy, you will be able to make stylized art that, for example, doesn't have one arm longer than the other, because you will have learned how to measure proportions, even if you don't draw realistic proportions. So that if you decide you want to draw unrealistically long legs (eg: Sailor Moon), you'll be able to make them look good and keep them consistent.

You will also be able to draw figures in any position, because you will have learned how body parts are made up and how they move, as well as foreshortening/perspective. Then, when you go to draw a pose you haven't drawn before, it will be WAY easier.

IV. UNDERLYING SHAPES

Although this is one of the least-mentioned aspects of art-learning, it is, in my opinion, one of the most important, because when you learn to see underlying shapes (the quasi-geometrical shapes that build up a figure), coupled with learning how to measure a form using other parts of the same form as reference (measuring the length of one body part by the number of times another body part fits in it, as mentioned in Section III, above), you will be able to DRAW. (Period.) You won't be able to draw just people. Or just wolves. Or just cats. You will be able to break down a new subject into its building blocks and come up with a very reasonable likeness. And whatever's different, you'll easily be able to make relative measurements to spot why and fix it.

Once you learn to identify underlying shapes and how to measure proportions in anything, you will also be able to pick up and reproduce any existing style without much trouble.

[link to Tumblr post with this artwork]

For example, this was my first time drawing anything Peanuts. I didn't have to do practice sketches for it (though there's nothing wrong with doing that). But I knew, from realism, that to achieve a good likeness, you need to measure body parts relative to other body parts, so I looked at Schulz's drawings and was able to determine: OK, Charlie Brown's head is roughly this shape, his body is so many heads tall, his eyes are this % of the head, the ears are this far in, the arms reach down to here, etc. I knew what to look for.

V. FOR THOSE WHO WANT SEMI-REALISM

If you want to do "semi-realism," you'll have a way easier time of it by learning realism and then stripping it down as much as you like, than by starting off with "100% anime" and trying to build it up without knowledge of realism. People think the latter is easier, because it *seems* less intimidating, but it's like trying to drive to a store you've never been to without knowing its address: you'll be driving around forever trying to find it, and it will be frustrating. What people call "semi-realism" is stylized realism, and you can't really hit it without knowing how realism works.

CLOSING NOTES

It also doesn't mean you should stop drawing anime/cartoons and focus solely on realism for X amount of time - you can do both concurrently. In fact, the most fun way to study realism is to do so on your favorite subjects; you can even turn your reference into your favorite character!

Studying realism is also one of the best ways to help develop your OWN, unique style; one which, when people look at it, say, "Oh, that's [your name]'s work!"

[*]Footnote 1: It is fine as long as you are drawing for yourself. As soon as art is a job and you're drawing for an employer, you have to draw in the style they tell you to. So, in this case, it's to your advantage to be flexible.

I hope this was helpful and helps clear up a common misunderstanding people go through when receiving feedback. 💞

MORE ART ADVICE ARTICLES

You can find the index to all Art Advice Articles [here] including:

How to Deal with Art Block

How to Have a Positive Outlook

How to Develop Your Own Style (coming soon!)

etc.

#art advice#art tips#art help#art resources#art learning#artists on tumblr#art#how to#art tutorial#anime art#cartoon#semi realism

91 notes

·

View notes

Note

This will be a very specific thing to ask, but what advice would you give to an artist who wants to draw masculine characters with more strong facial features/body build? What to pay attention to while drawing? I've been trying to figure it out but they still don't look the way I would love them to look

This is actually not an easy thing to answer without a visual example to start from, right out of the blue I could tell you that strong features are usually done by working volumes with sharper lines, rather than bold, flowy ones, however it's always best to alternate the two, otherwise the drawing may look stiff, so it's all a matter of studying how volumes work and understanding how to use lines in such a way. The better way to study is to look up as many artist as you can, possibly the ones that you feel closer to stylistically or that inspire you the most, and try to understand how they stylize volumes and what you're looking for. For me, that was the best way to actually grasp some aspects of drawing I used to struggle a lot with (and still do at times).

I know this is a bit of a generic answers, I hope it was somewhat helpful!

However, if this is not the answer you were looking for, feel free to message me again - even off anon so we can talk about it privately if you'd rather - and I'll be more than happy to help out and give some more specific advice!

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Movie Odyssey Retrospective

Fantasia (1940)

With production on Bambi postponed, Walt Disney dedicated himself to Pinocchio (1940) and a film featuring animated segments accompanying classical music. Walt’s demands for innovation saw Pinocchio’s budget skyrocket, and the film left Walt Disney Productions (today called Walt Disney Animation Studios) on unstable financial grounds. This laid impossible financial expectations for the latter film – tentatively entitled The Concert Feature – to meet. War halted the possibility of cross-Atlantic distribution as Walt continued to emphasize innovation for each of his features and workplace tensions rose among his animators. What was planned as a glorified Mickey Mouse short set to Paul Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice – Mickey’s popularity was flagging by the mid-1930s, trailing other Disney counterparts and Fleischer Studios/Paramount’s Popeye the Sailor – grew to include seven other segments. The film that became known as Fantasia remains the studio’s most audacious work. Though it built off the visual precedents of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), the volume of artistry for artistry’s sake contained in Fantasia, eighty years later, remains unsurpassed.

After the Philadelphia Orchestra’s conductor/music director Leopold Stokowski offered to record The Sorcerer’s Apprentice for free (he did so with a collection of Hollywood musicians; the English-Polish conductor, a rare conductor who spurned the baton, was among the best of his day), cost overruns on The Sorcerer’s Apprentice led to its expansion as a feature. To provide commentary as Fantasia’s Master of Ceremonies, the studio sought composer and music critic Deems Taylor – who came to Disney and Stokowski’s attention in his role as intermission commentator for radio broadcasts of New York Philharmonic concerts. But both Disney and Stokowski were too busy during the summer of 1938 to brief Taylor on their plans. Stokowski spent that summer in Europe seeking permission for the rights to use certain pieces from various composers’ families (this included visits to Claude Debussy’s widow and Maurice Ravel’s brother); Disney was occupied with the construction of the Burbank studio. After Stokowski returned from Europe in September, Disney asked Taylor to come to Los Angeles to formally discuss Fantasia. Taylor agreed, arriving one day after Stokowski and Disney began their meetings, staying in Southern California for a month.

Over several weeks that September, Disney, Stokowski, and Taylor made the final selections for pieces – suggested by story directors Joe Grant and Dick Huemer (both worked on 1941’s Dumbo and 1951’s Alice in Wonderland) – to be featured in Fantasia. Hours were spent listening to classical music recordings, followed by brainstorming potential visualizations. The meetings were recorded by stenographers, with transcripts (housed at the Walt Disney Archives in Burbank) provided to all three participants. During these meetings, Walt mostly listened to Stokowski and Taylor consider every suggestion by Grant and Huemer:

DISNEY: Look, I really don’t know beans about music. TAYLOR: That’s all right, Walt. When I first started, I thought Bach wrote love stuff – like Romeo and Juliet. You know, I thought maybe Toccata was in love with Fugue.

During these meetings, an admiring Walt – in addition to gifting a potential last hurrah for Mickey Mouse and to create a film unrestrained by commercial demands – realized he wanted to create a gateway to classical music for those who might not otherwise give such music a chance. Always leading his writing staff in developing stories, Walt felt relieved that he could share this responsibility with Stokowski and Taylor. Free of the storytelling stresses plaguing the Pinocchio and Bambi productions at the time, these tripartite meetings were not beholden to narrative cohesion, allowing the participants to suggest anything that their imaginations conjured. Without the constraints of narrative logic or predictions about what an audience wanted to see, Fantasia became the center of Walt Disney’s passion until its completion.

Nine selections were made by the trio, with one piece later being dropped entirely (Gabriel Pierné’s Cydalise and the Satyr) and another being replaced after its completion. A completed segment for Debussy’s Clair de Lune* was substituted out for Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 (the mythological scenario Walt envisioned for the Pierné reverted to the Beethoven, but more on this later). Over the next few years, Disney’s animators would complete the artwork; Stokowski would study, arrange, and record the selections with the Philadelphia Orchestra (except for The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, which had already been recorded); Taylor would write his introductions to be filmed at the Disney studios.

In almost all of cinema, music accompanies and strengthens dramatic or comedic visuals. Fantasia is the reverse of this relationship. The animation provides greater emotional power to the music – an arrangement that may be startling to viewers unfamiliar with or disinclined to classical music or cinematic abstraction. Fantasia’s opening scenes and piece introductions feature the affable Taylor, who outlines the film’s conceits:

TAYLOR: Now there are three kinds of music on this Fantasia program. First, there’s the kind that tells a definite story. Then there’s the kind that, while it has no specific plot, does paint a series of more or less definite pictures. And then there’s a third kind, music that exists simply for its own sake.

That last kind, also known as “absolute music”, opens Fantasia with Johann Sebastian Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, an organ piece arranged for orchestra (“Toccata” and “Fugue” refer to the musical forms of the piece’s two halves). As James Wong Howe’s (1934’s The Thin Man, 1963’s Hud) gorgeous live-action cinematography of the orchestra (the Toccata) transitions to animation (the Fugue), the audience witnesses Walt Disney Animation’s first, and arguably only, foray into abstract animation – as opposed to abstract stylizations to bolster a macro-narrative – for a feature film. The Toccata and Fugue is a pure visualization of listening to music, as if the animation was improvised. The sequence involves, among other things, string instrument bridges and bows flying in indeterminate space, figures and lines rolling across the screen, and beams of light and obscured shapes timed to Bach’s piece. In these opening minutes, Fantasia announces itself as a bold hybrid of artistic expression in atypical fashion for Disney’s animators.

Next is The Nutcracker Suite by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, which is subdivided into six dances (“Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy”, “Chinese Dance”, “Arabian Dance”, “Trepak”, “Dance of the Reed Flutes”, “Waltz of the Flowers” – these dances are placed out of order, and the “Miniature Overture” and “Marche” which open the suite are not present). Disney, Stokowski, and Taylor made this selection decades before Tchaikovsky’s now-most famous ballet became a Christmas cliché in the United States – it was barely performed in the early twentieth century and is usually regarded, among classical music experts and by the composer himself, as a lesser Tchaikovsky ballet.

History aside, this animated treatment of The Nutcracker utilizes an astonishing array of different animation techniques across all six dances. With The Nutcracker, the Disney animators, for the first time, take a piece with a preexisting story, animate sequences adhering to the music’s essence, yet producing images that have nothing to do with the original material. In Fantasia, The Nutcracker remains a ballet – the sugar plum fairies, racially insensitive mushrooms, fish, and flowers move as if they are on a ballet stage. But there is nothing, in the sense of a narrative through line, to connect all six dances. Set to the changing of the seasons, The Nutcracker contains gorgeously-animated fairies and intricate fish (Cleo from Pinocchio was a testing run for the “Arabian Dance”), climaxing with fractal flurries that look like an antique Christmas card brought to life. Even the racist “Chinese Dance” exemplifies masterful character design – simplicity does not preclude expressiveness. The Nutcracker’s spectacular inclusion improved Tchaikovsky’s standing and his least acclaimed ballet among casual classical music fans.

Based on Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s poem of the same, Paul Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice ushers in the Mickey Mouse short that overshadows all others. With the animators’ adaptation closely following Goethe’s poem, Dukas’ original piece is impossible to listen to without imagining Mickey, rogue anthropomorphic broomsticks, and thousands of gallons of water. The Sorcerer’s Apprentice marked the cinematic debut of Mickey Mouse with pupils, as designed by Fred Moore (the dwarfs on Snow White, the mermaids in 1953’s Peter Pan) – Mickey was first drawn with pupils on a program to an infamous, booze-filled party Walt Disney threw in 1938. With pupils, Mickey’s gaze provides a sense of direction that black ovals make ambiguous. The additional personality – not to say Mickey Mouse’s original character design lacked personality – thanks to the pupils strengthens Mickey’s expressions of jollity, shock, submissiveness. A lanky, stern sorcerer is Mickey’s brilliant foil. Their physical differences and reactions imbue The Sorcerer’s Apprentice with a troublemaking charm recalling Mickey’s earliest short films, sans the slapstick that defined those appearances. These decisions heralded a new era for how the Walt Disney Studios’ mascot would be animated and portrayed in his upcoming shorts.

This segment’s chiaroscuro sets a pensive atmosphere, enclosing Mickey in a black and brown gloom as he – a nominal apprentice – is tasked with menial duties, not magic. The indefinite shape of the sorcerer’s chambers owes to German Expressionism (as does the penultimate piece in Fantasia), with its impossibly curved angles and architectural fantasy hiding secrets that no sorcerer’s apprentice assigned to carry buckets of water could understand. The Sorcerer’s Apprentice tonal shifts always feel justified, rooted in the sequence’s character and production design – although, in this regard, the sequence is surpassed later in Fantasia.

Immediately following a mutual congratulations between Mickey (voiced by Disney) and Stokowski is Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. Stravinsky’s brief one-act ballet/piece debuted in 1913 to an audience riot because of its musical radicalism – The Rite of Spring liberally partakes in polytonality (using two or more key signatures simultaneously), polyrhythms, constant meter changes, unorthodox accenting of offbeats, chromaticism, and piercing dissonance. Concert hall attendees had heard nothing like The Rite of Spring before and, even in 1940, Stravinsky’s composition divided audiences. The Rite of Spring – precipitating the concert hall’s philosophical battles of the late twentieth and twenty-first century over whether melody and coherent rhythm still has a role to play in contemporary classical music – is a gutsy choice to present to general audiences.

At fifty-eight years old when Fantasia was released, the Russian-born, French-naturalized (and soon-to-be American citizen) Stravinsky is the only composer to have lived to see one of his pieces adapted for a Fantasia movie. Stravinsky despised Stokowski’s interpretation and cutting of his music (all musical cuts were Stokowski’s decisions, reasoning that an audience of classical music neophytes might not be comfortable in a theater for too long during Fantasia), but applauded the animated interpretation of his work. As a ballet, The Rite of Spring is about primitivism. The Disney animators sheared the piece of its human element to liberate themselves from the ballet’s narrative (and believers of creationism). Instead of portraying primitive humans, they elected to depict an account of Earth’s early natural history – its primeval violence, the beginning of life, the reign and extinction of the dinosaurs. Astronomer Edwin Hubble, English biologist Julian Huxley, and paleontologist Barnum Brown served as scientific consultants on The Rite of Spring, imparting to the animators the most widely-accepted theories within their respective scientific fields at the time.

As the camera moves towards the young Earth, Stravinsky’s piece clangs with orchestral hits emboldened by the volcanic violence on-screen – the animated flow of the lava and realistic bubble effects (studied by the animators using high-speed photography on oatmeal, mud, and coffee bubbles inflated by air hoses) are technical masterstrokes. Giving way to single-celled organisms and later the dinosaurs, the camera’s perspective keeps low, emphasizing the height of these prehistoric creatures. The suggestion of weight to the dinosaurs distinguish them from comic, cartoonish depictions in American animation up to that point. The Rite of Spring is the only Fantasia segment where I can imagine viewers unversed in classical music, but making an honest attempt to appreciate the music, being repelled for the entire passage because of the music itself. Otherwise, so ends Fantasia’s immaculate first half.

After the intermission, we meet the Soundtrack, a visual representation of the standard optical soundtrack, with Deems Taylor. It is an entertaining diversion before Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 (“The Pastoral Symphony”) – accompanied by scenes of winged horses, centaurs, pans, and gods from classical mythology. These characters and backgrounds, and clear story were intended for Pierné’s Cydalise and the Satyr before its deletion from the program. Seeking a replacement piece, Disney chose Beethoven’s Pastoral over Stokowski’s objections. Stokowski, who largely dismissed potential criticisms from diehard classical music fans and encouraged Walt’s experimentation in their meetings, noted that Symphony No. 6 – the unidentical twin of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5; both were composed simultaneously and debuted to the public on the same evening in 1808 – was Beethoven’s tribute to the Viennese countryside and that, according to Beethoven’s program notes from that 1808 concert, represented, “more an expression of feeling than painting.” Beethoven’s long summer walks amid babbling brooks, verdant forests, and wildlife provided solace from his increasing deafness. Deems Taylor, acknowledging Stokowski’s citations of the symphony’s history, thought the decision a brilliant one. By simple majority, Walt’s repurposed idea for the mythological setting for the Pastoral was produced.

For the entirety of the Pastoral’s second movement, we see cupids assisting in centaur courtship. These hackneyed scenes are glacially paced, overly dependent on Fred Moore’s risqué good girl art. Fantasia’s most objectionable content also appears in the second movement in the form of crude racial caricatures of black women – though the worst example will almost certainly not be in any available modern print of Fantasia, as the Walt Disney Company has consistently cut the footage and essentially denies it ever existed. The story’s tone almost trivializes Beethoven’s Pastoral, making the seond movement a tiresome Silly Symphony. Arguably the weakest of the original Fantasia numbers (Stokowski’s criticisms justified by the final product), the Pastoral nevertheless contains an eye-catching palate of color that makes it unmissable. Encouraged by the supervising animators on the Pastoral to use as much color as possible, the throngs of artists assigned to this were up to the task. Rarely does Technicolor, in full saturation, look brighter than when the young flying horses take to the sky, centaurs and centaurettes partake in mating rituals, and an ever-inebriated Bacchus stumbles into the centaurs’ party.

From the closing ballet of Act III of Amilcare Ponichelli’s opera La Gioconda, the Dance of the Hours is the penultimate piece in Fantasia. Dance of the Hours suffers from its placement in the film. After Bacchus’ simpleminded, jolly antics in the Pastoral, this whole segment is the one that most resembles Disney’s Silly Symphony short films. Presented as a comic ballet with ostriches, elephants, hippopotamuses, and alligators, the Dance of the Hours has the ideal supervising animators assigned to it – caricaturist “T.” (Thornton) Hee and Pluto/Big Bad Wolf animator Norm Ferguson. Dancer Marge Champion (the model for Snow White’s dancing), ballerina Tatiana Riabouchinska and her husband David Lichine served as models for the balletic motions, endowing the segment with choreographic – though perhaps not biological – accuracy. As long as the viewer basks in the Dance of the Hours’ unadulterated silliness and does not mind the fact it is the least innovative piece in terms of its animation, it is an enjoyable several minutes of Fantasia.

Fantasia concludes with a staggering pairing: Modest Mussorgsky’s‡ tone poem Night on Bald Mountain (partial cuts) and Franz Schubert’s Ave Maria (with English lyrics). After an inconsistent second half to Fantasia, the film ends with two selections so remarkably contrasting in musical form and texture and animation. Night on Bald Mountain, like Dance of the Hours, is the responsibility of an ideal supervising animator in Wilfred Jackson (1937’s The Old Mill, Alice in Wonderland) and one of the finest character animators in Bill Tytla (Stromboli in Pinocchio, Dumbo in Dumbo). Using Mussorgsky’s written descriptions for the piece, the animators closely adhere to the composer’s imagined narrative. On Walpurgisnacht, a towering demon atop a mountain unfurls his wings and summons an infernal procession from the earthly and watery graves below. This demon, the Slavic deity Chernabog, is Tytla’s greatest triumph as a character animator and for all animated cinema. With movements modeled by Béla Lugosi of Dracula (1931) fame – one could not ask for a better model – and Jackson himself, Tytla captures Chernabog’s enormity, the torso’s muscular details, and graceful arm and hand movements that never falter frame-by-frame. Chernabog moves more realistically than any Disney character – in shorts and features, Rotoscoped or not – and would retain that distinction until the advent of computerized animation. In Tytla’s mastery, one forgets that Chernabog is nothing but dark paints.

Jackson’s use of contrasting styles to demarcate Chernabog from the ghosts and spirits summoned to the mountain’s summit further contributes to Night on Bald Mountain’s satanic atmosphere. The shades answering Chernabog’s call appear as either rough white pencil sketches that one might expect in a concept drawing or translucent, wavy figures animated with rippling effects that required a curved tin to complete. That rippling, wafting effect – lasting only several seconds in Night on Bald Mountain – was among the most labor-intensive parts of Fantasia, requiring animators to be present at work in multiple shifts across twenty-four hours to photograph the movements for each frame. The Walt Disney Animation Studios would not delve into such darkness again until The Black Cauldron (1985).

Night on Bald Mountain benefits from being followed immediately – without a Deems Taylor introduction (he introduces both pieces prior to the Mussorgsky) – by Schubert’s Ave Maria, and vice versa. As Chernabog and the spirits romp, an Angelus bell tolls just before the dawn, signalling the end of their nocturnal merriment. Stokowski arranged Night on Bald Mountain’s final bars to fade away as a vocalizing chorus precedes the beginning of the Ave Maria. Where Night on Bald Mountain incorporated numerous styles in a disorderly frolic, the Ave Maria is rigid and structured by design (the camera only moves horizontally from left to right or zooms forward). In twos, robed monks walk through a forest bearing torches – their figures obscured behind trees, their reflections gleaming in the water. As the camera zooms forward for the first time, darkness envelops the screen. Using English lyrics by Rachel Field that do not adapt Schubert’s German lyrics, soprano Julietta Novis sings the final stanza of the Ave Maria (Field’s first two stanzas were unused) as the multiplane camera gradually glides through a still bower. The Ave Maria features some of the smallest individually-animated pieces (the monks) ever brought to screen. And with the multiplane camera (when the monks are onscreen, the multiplane camera – which was created to provide depth to animated backgrounds – is utilized, for the first time in its existence, to evoke flatness), it also contains what may be the longest uncut sequence in animation history.

The Ave Maria’s beauty sharpens the contrast between itself and Night on Bald Mountain – the sacred and the profane. Their spiritual and musical pairing is cinematic transcendence. Yet, the Ave Maria was almost cut entirely from the film at the last moment, as it was spliced into the final cut four hours before Fantasia’s world premiere – all thanks to an earthquake that struck Southern California a few days earlier. How fortunate for those worked on the segment, the preceding Night on Bald Mountain, for Fantasia, and cinema that the Ave Maria was included in the end.

Some of the pieces considered by Disney, Stokowski, and Taylor that did not make the final cut appeared in Fantasia 2000 – most notably Igor Stravinsky’s Firebird Suite (1919 version), which Walt initially preferred over The Rite of Spring until convinced by Taylor otherwise. In contrast to his company’s contemporary attitude, Walt Disney himself was disapproving towards proposing sequels, with Fantasia proving the only exception. Walt imagined sequels to Fantasia to be released every several years, with newer Fantasia sequences starring alongside one or two reruns. Other pieces Disney, Stokowski, and Taylor (who wrote additional introductions in anticipation of future Fantasia films; I am looking into whether these introductions still exist) contemplated remain unadapted as Fantasia segments. The notes and preliminary sketches of some of these proposed segments – including a fascinating consideration to adapt selections from Richard Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen (the Ring cycle) to J.R.R. Tolkien’s then-newly-published children’s book The Hobbit – most likely reside in the Walt Disney Archives for reference if and when the company’s executives approve a third Fantasia movie.

Walt Disney’s dream of Fantasia sequels was quickly dashed. His proposal to add Fantasound – the studio’s prototypical variant of a stereo sound system – proved extravagantly expensive for all but a dozen movie theaters in the United States. Released as a roadshow (a limited national tour of major American cities followed by a general release), the inflated ticket prices due to the roadshow’s Fantasound system harmed Fantasia’s box office. Though a vast majority of film critics and some within classical music circles hailed Fantasia, the vocal and vehement division was inescapable. Some cultural and film critics, citing solely that Walt Disney had bothered to touch classical music, castigated Walt and Fantasia as pretentious (classical music’s negative reputation of being dated, inaccessible, and snobby was not nearly as widespread in the 1940s as it is today; musical appreciation and education has receded in the U.S. in the last several decades). Intransigent classical music purists – usually noting Stokowski’s frequent cutting of the music – lambasted Fantasia as debasing the compositions (I dislike Stokowski’s cutting, certain stretches of the Bach and Stravinsky recordings, and much of the Pastoral’s story, but this is a reactionary overreach). The negativity from both spheres stole the headlines, eroding interest from North American audiences. With the European box office non-existent, Pinocchio and Fantasia stood no chance of turning a profit on their initial releases. Their combined commercial failure sent the studio in a financial tailspin – a crisis that a comparatively low-budget Dumbo single-handedly averted.

Rankled by the criticism directed towards Fantasia, Walt Disney’s anger turned inwards, fostering a personal and corporate disdain of intellectuals that marked the rest of his career. One sees it in his irritation towards critics decrying the handling of race in Song of the South (1946); it is also there in his dismissive treatment of P.L. Travers over an adaptation of her novel Mary Poppins.

Mounting tension among Disney’s animators over credits, favoritism towards veteran animators over the studio’s pay scale and workplace amenities, the announcement of future layoffs due to the studio’s financial crisis, the unionization of animators at all of Disney’s rival studios, and Walt’s political naïveté in heeding the words of Gunther Lessing (the studio’s anti-communist legal counsel) threatened to explode into public view. On May 28, 1941, unionized Disney animators began what is known – and downplayed to this day by the Walt Disney Company – as the Disney animators’ strike. The strike, which lasted for two months, shredded friendships between strikers and non-strikers. Walt Disney, who surveyed the striking animators and filed away names in his deep memory, is said to have repeatedly referred to the strikers as, “commie sons of bitches”. More than once at the studio’s entrance, Walt slammed on his car’s accelerator towards the strikers and hit the brakes before making contact.

Under pressure from lenders, Walt recognized the union in late July but nevertheless fired numerous striking (and non-striking) animators in the months afterwards. Many of those terminated by Disney joined cross-Hollywood rivals or founded the upstart United Productions of America (UPA; Mr. Magoo series, 1962’s Gay Purr-ee). An embittered Walt would never again feel the sense of family among his studio’s staff as he did in the 1920s and ‘30s at the Hyperion studio, despite his public persona and statements to the contrary.

A wonder of filmmaking, Fantasia arrived in movie theaters as Disney’s Golden Age began to fracture. If not for war or Walt Disney’s obstinance, this era might have lasted longer. In the decades since, the contemptuous responses to Fantasia from classical music elites have cooled – for classical music lovers with not nearly as much institutional power, Fantasia has indeed become a beloved gateway into the genre. Its irrepressible beauty, invention, and bravery as a visual concert cannot be overstated.

My rating: 10/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating.

This is the sixteenth Movie Odyssey Retrospective. Movie Odyssey Retrospectives are reviews on films I had seen in their entirety before this blog’s creation or films I failed to give a full-length write-up to following the blog’s creation. Previous Retrospectives include The Wizard of Oz (1939), Dumbo (1941), and Godzilla (1954).

For more of my reviews, check out the “My Movie Odyssey” tag on my blog.

* The completed Clair de Lune segment was re-edited and integrated into Make Mine Music (1946).

‡ Mussorgsky’s original score for Night on Bald Mountain – which was not performed again during his lifetime following the piece’s premiere – went missing after his death in 1881. In 1886, fellow composer and colleague Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, controversially began editing Mussorgsky’s partially missing scores using his “musical conscience” (including the opera Boris Godunov). Rimsky-Korsakov wanted to preserve and retain his colleague’s music among aficionados of Russian classical music. The version of Night on Bald Mountain heard in Fantasia is Rimsky-Korsakov’s arrangement of the piece. Mussorgsky’s original score to Night on Bald Mountain was found in 1968, but the Rimsky-Korsakov arrangement is more frequently performed today.

#Fantasia#Walt Disney#Leopold Stokowski#Deems Taylor#Mickey Mouse#Philadelphia Orchestra#Joe Grant#Dick Huemer#James Wong Howe#Fred Moore#T. Hee#Norm Ferguson#Wilfred Jackson#Bill Tytla#My Movie Odyssey

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

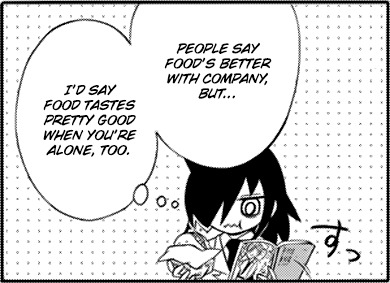

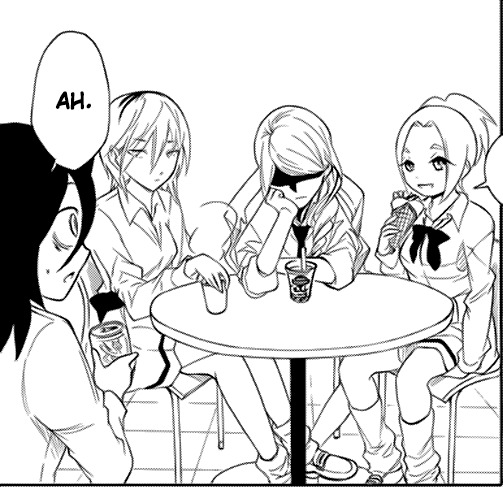

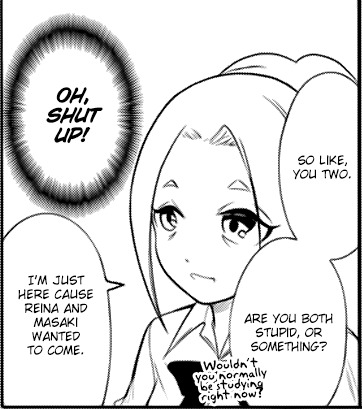

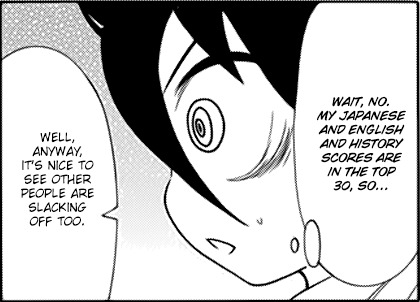

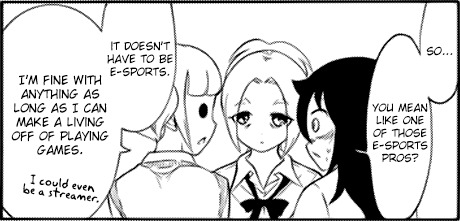

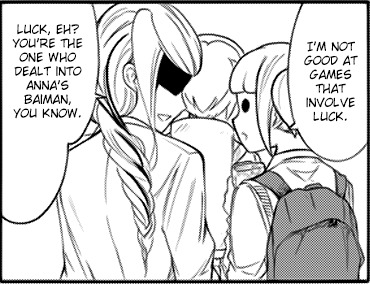

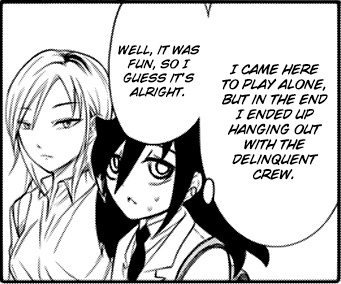

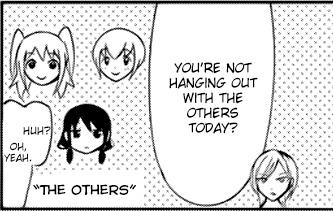

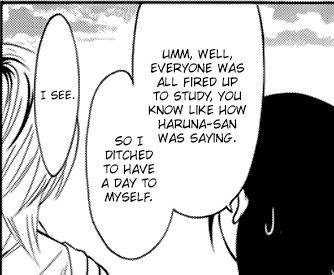

BECAUSE I’M NOT POPULAR, I’LL READ WATAMOTE: CHAPTER #147

In today’s chapter, Watamote goes back to its roots as we find Tomoko hankering for some alone time. But you’d be wrong if you think it’s going to be that simple. Because underneath all the nostalgia moments lies what may just be the most crucial development that Tomoko has ever undertaken, and it’s the type of growth that could’ve only been realized by taking a quick trip down memory lane.

Chapter 147: Because I’m Not Popular, I’ll Wander Around Alone

Oh hey, it’s that one male teacher who’s made periodic appearances throughout the series. Thank you for being there during Tomoko’s character establishing moment.

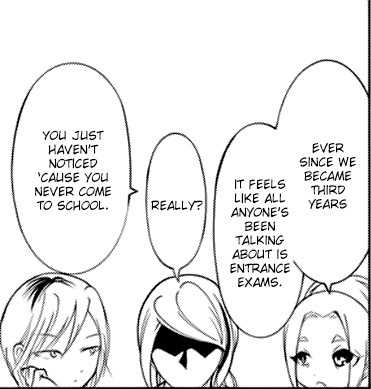

So Wada is pretty good at English, huh? So not only do they both like manga, but Tomoko and Wada are also knowledgeable in the same subject. How nice.

Better break out the pitchforks.

A common social “rule” in Japan is the emphasis on being able to read the room and reciprocating that atmosphere, or at the very least, not rock the boat. Tomoko has never really supported or condemned that notion, though unlike Yuri, is more likely to go with the flow. As someone who lives in a culture that discourages group mentality, it’s nice to see a character like Tomoko benefit from it.

Cliques? What high school cliques? All I see is a group of distinctly unique girls organically enjoying each other’s company.

This first-person POV shot looks straight out of a harem manga, only more authentic and devoid of cattiness.

Let it be known that in this moment, Tomoko actually does break the mood. For the first time in as long as I can remember, Tomoko finds herself in a social situation with little risk, but actively breaks away from it in favor of alone time.

With that, the seed of Tomoko’s greatest epiphany has sprouted.

Not in the mood to binge through twenty volumes this time, huh?

Boy does this take me back...

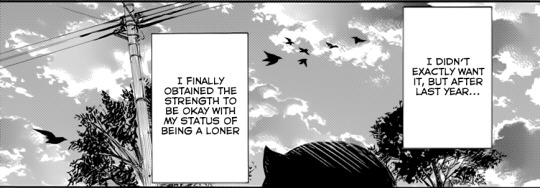

Compared to Tomoko’s first solo trip to Not-McDonald’s, it’s amazing to see the way she’s changed alongside the ways she hasn’t. Her anxiety is 95% gone, with the remaining 5% accounting for general uncertainty, hence the very brief stuttering. Embrace that 5% Tomoko–that’s all you.

Introvert Problems #051: Activities that are individual in nature double as recharging opportunities, but can come off as unfriendly if openly pursued.

Okay honestly, this is the type of growth I’ve been low-key hoping for since the very start of the series. Tomoko has finally realized that a desire to be alone is not something she needed to fix, but to accept. For the longest time, she didn’t realize a large part of her alone time was because she craved it. It brought her comfort, even if she didn’t want to believe it. And it took having a considerable amount of friends (whose companionship was definitely necessary) for her to understand that she didn’t want to get rid of being alone.

She wanted to get rid of being lonely.

Professional slacking. Otherwise known as, putting in the bare minimum effort to avoid future hardships.

Nom.

I’m sure there are various theories for both perspectives, but I think the main takeaway is that food tastes the best when you’re in your comfort zone. Whether that includes company for not is based on your personal preference.

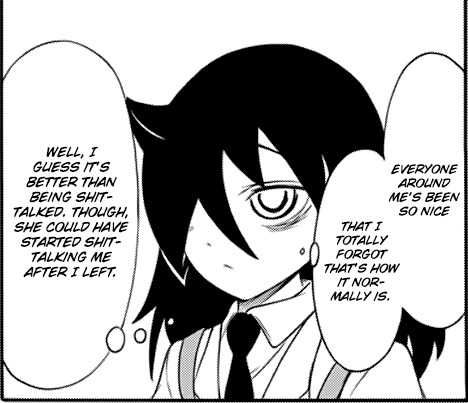

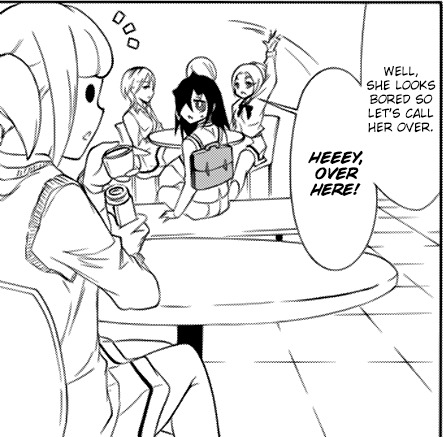

Indeed, it is. This is none other than the class representative of Tomoko’s second year, Girl-With-Awesome-Hair. Naturally, taking up two whole panels is a clear sign that this isn’t the last we’ll see of her.

Ah, yes, the classic “normies suck” self-fulfilling prophecy–other people are jerks, and that’s why I’m alone. Tomoko was guilty of having this perspective, but she didn’t really recognize it until the first cafeteria chapter with Nemo. That was the point she realized that all those “popular” people are genuinely nice people. It was jarring at first, but once Tomoko got used to people being nice to her, she stopped perceiving that kindness as some kind of exception, and just took it as normal behavior. While alluding to the possibility of getting shit-talked behind her back is more of her realism at work, it thankfully doesn’t fall too deep into self-destructive cynicism.

Could it be that Tomoko’s recent friendships are subconsciously making her pursue more public activities even on her loner vacation? You better believe it.

Tomoko’s become quite financially savvy lately, don’t ‘cha think? It certainly beats spending $150 on a whim for a Vocaloid.

I cannot think of any other nickname that suits her better.

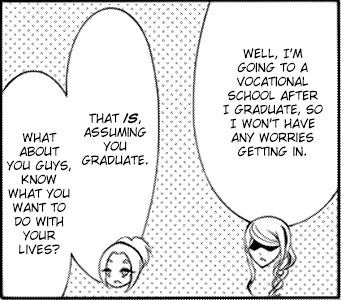

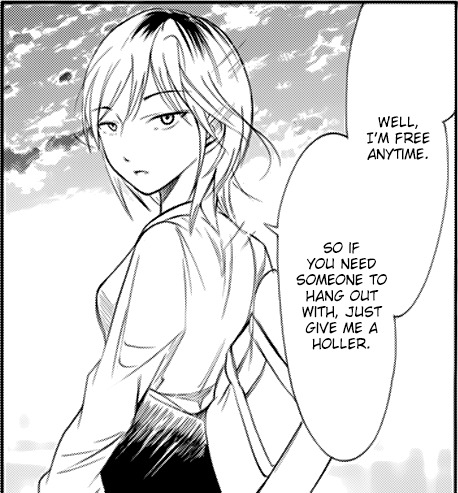

For a girl with the single most stylized face in the series, her entrance in this chapter sure makes an impact with the way she strikes such an alluring pose. Of course, that’s the joke, ain’t it?

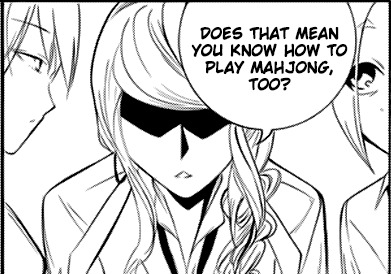

It would seem that we’re getting a “doesn’t-care-what-anybody-else-thinks”-type of character for her. Well, she’s a competitive gamer as we soon learn, so not giving a shit about her social status is kind of a prerequisite.

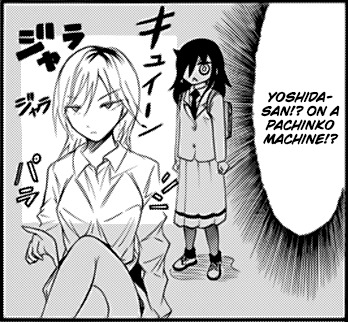

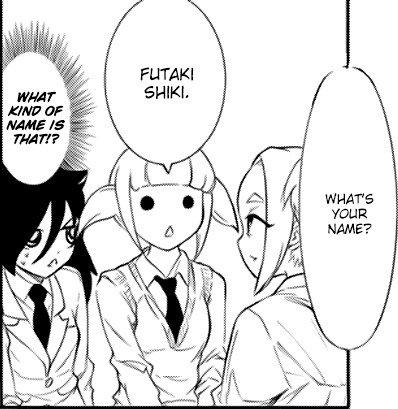

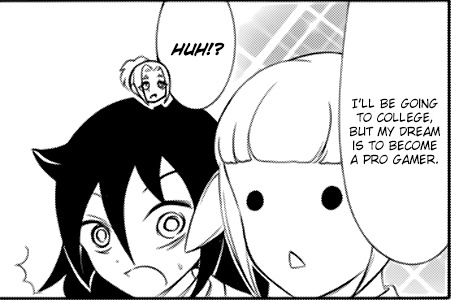

I honestly did a double-take at this, as it’s the first time Tomoko has addressed Yoshida in her mind by her real name instead of “the delinquent”. We’re just a hair’s length away from reaching official “friend” status with these two.

Aw, that’s adorable. Tomoko actually sort of cares about Yoshida’s financial wellbeing. I’ve also noticed a bit of a trend with Tomoko in that she gets “terrified” of her friends breaking her expectations of them, even if they’re not doing anything that terrifying. In Yoshida’s case, I think that’s partly because Tomoko has a bit of a superiority complex that would get broken if Yoshida was a better person than she likes to believe.

Tomoko’s nicknaming game is on point today.

It was hinted before that Futaki may be popular with the boys what with being a “gamer girl” and all. While it’s still a little too early to confirm or deny that, the fact that most of the onlookers here are guys has to count for something.

I remember when fans gave her the name “Potential-san”. Given where this chapter is headed, I think that name fits even more with Futaki’s blooming characterization.

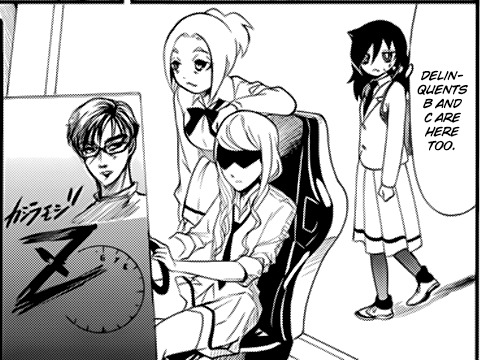

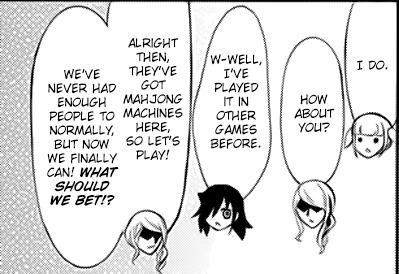

It’s amazing how much of their personalities you can see in this single panel. Yoshida is all easygoing, grasping her drink from the top all aloof-like. Reina is the toughest, taking a quietly aggressive stance with her elbows on the table like a boss. And Anna is the most inviting, smiling with a crêpe in her hand to signify her (relative) sweetness.

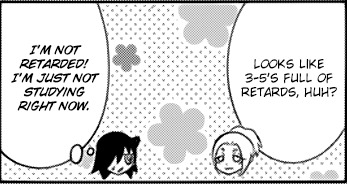

I find it fascinating that Anna can say some pretty rude things that borderline on mean, but it never really comes off as malicious (or is it just me?). She gives off that vibe of someone who mercilessly teases people in a way that’s “all in good fun”, and I hope to see more of that side to her.

First off, Tomoko being a full table’s length away from the scary delinquents is gold.

Second and not to beat a dead horse, Anna’s a cool chick.

I think I’m gonna need to call upon the Council of WataMote Fans with Too Much Time On Our Hands for this. Why exactly is that name so unusual?

Of course, Anna wouldn’t be part of the delinquent squad if she didn’t shit-talk every now and then. But as I said before, she has this style of going about it that feels more like brash innocence than deliberate antagonism. Maybe it’s the heroin eyes...

Other than that, she does imply that she’s the smartest of her group, though whether that perception is actually reflective of herself isn’t certain yet.

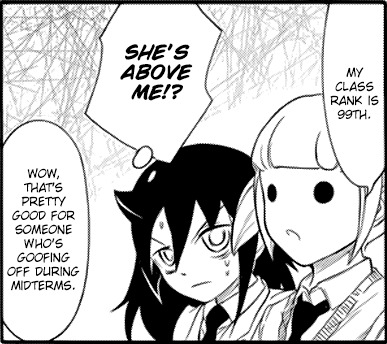

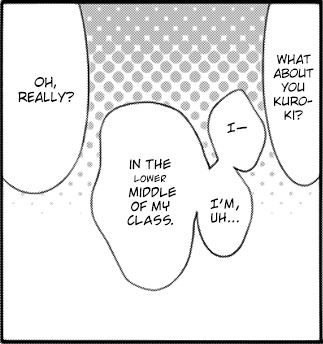

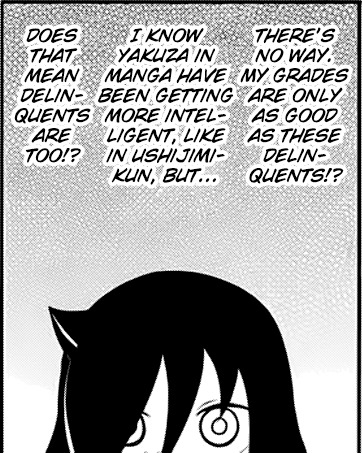

More of Tomoko’s superiority complex at work here. All she really knows about Futaki is that she plays games, and is assumedly a slacker. That fact that she still managed to outscore her must’ve been quite the blow to Tomoko’s insecurity. The only thing “worse” is if even Yoshida managed to rank higher than her.

I love dialogue gags like this, though usually the characters’ inner words are in parenthesizes in-between their actual spoken words. If Tomoko actually lowered her voice at the word “lower”, that’d be humorously sad.

It got “worse”.

Because a superiority complex actually requires a deep-seated sense of inferiority, Tomoko must be hella blown back right now. Grades were one of the only things she could feasibly claim dominance over, but now that she’s about to be usurped by the supposedly dumb delinquents, she only has her otaku interests to fall back on, which...isn’t always something to brag about.

Also, I especially like how Tomoko has started to compare delinquents to the yakuza. You know both would beat the tar out of her if they heard her compare them to the other.

You know, it makes perfect sense that Tomoko would be a top scorer in Japanese, English, and History. Since she’s such an avid reader (even if it is only manga and light novels), all that extra literature has most certainly been indirect study material, even if the actual course material isn’t nearly as lewd.

Additionally, slackerism loves company.

Yeah, if it wasn’t already abundantly clear than Reina is the delinquent among delinquents...

...she is.

Rekt to infinity.

But you know, this is actually an ingenious way to develop a gag character like Futaki. Her apparent gaming skills have always been played like a joke, but by having it be her long-term goal, it restructures that “quirk” of hers into a fleshed out personality. It doesn’t invalidate anything we’ve already seen from Futaki, and it neatly sets up a direction for her character to take.

I imagine Tomoko must feel pretty betrayed right now. She herself entertained the idea of being a gamer, but discarded that dream likely because it wouldn’t be a “proper” job. Now that she sees this girl she hardly knows who apparently has the luxury of making that dream a reality, Tomoko’s envy levels just skyrocketed. Sure, Futaki has no loyalty to Tomoko, so that sense of betrayal has no basis, but like how Akari felt about “angelic” Komiyama in chapter 108...

“...this just isn’t fair!”

I’m getting a Crazy Rich Asians vibe from this girl.

So Reina’s the competitive type, huh? I can dig it. It generally fits with the whole “eyes-must-not-be-seen” aesthetic, but it also explains why she and Yoshida have that “vitriolic best buds” relationship going on. I’d imagine that Reina’s the type to bet high stakes if she can get away with it...

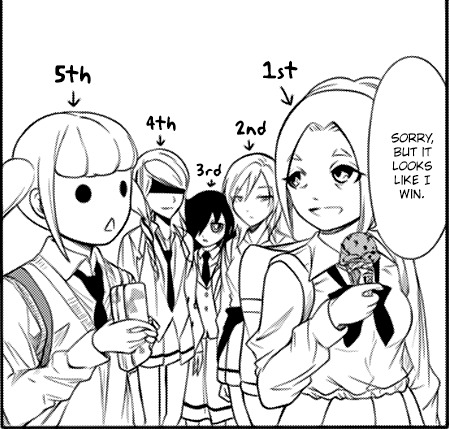

Just ice cream? Eh, no big loss. Unless it’s chocolate chip mint, then it’s a very big loss.

I wouldn’t exactly have these rankings as indicators of their skill level, since mahjong does involves a bit of luck and certainly reading your opponents. While it’s surprising that Futaki ended up in last place, I think it does help to nerf her power level somewhat. Shiro from No Game No Life she is not.

Careful, Futaki. That’s no excuse when you’re looking to be a professional gamer.

I must say, having Futaki unofficially join the delinquent crew is the last thing I would’ve expected, but it’s a delightful surprise nonetheless. They have some pretty good chemistry what them all being slackers/gamers. Plus, Futaki’s strange, but odd cuteness adds a dynamic that the delinquents were lacking until now.

Delinquents may be delinquents, but they always know how to have a good time.

Ho ho! So Nemo has officially been indoctrinated into their group? That poor, poor girl.

Council! I require your guidance! Is Haruna the last name for Anna? Or did Tomoko just get her name wrong! I must solve this conundrum at all costs!

If you try to tell me that Yoshida isn’t absolutely gorgeous in this shot, then you’re a big, fat liar.

Looking back on this chapter, Yoshida didn’t actually have many notable lines until this moment. But this single bit of dialogue greatly makes up for it. This is the very first time that Yoshida has personally offered to hang out with Tomoko without any sort of coercion or reluctance. It’s the most damning evidence we now have that says Yoshida now openly views Tomoko as her friend. As a long-time reader, I couldn’t feel any more proud.

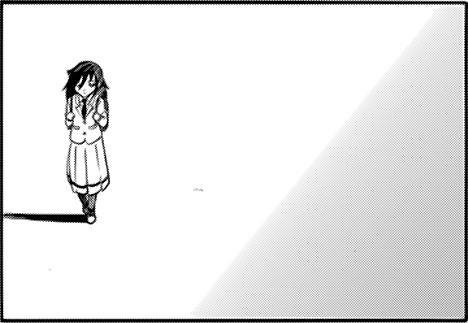

In comic book terms, we call this The Negative Space of Melancholy.

And really, wasn’t that the “goal” of this series all along? Making friends wasn’t the real endgame. If it were, it very well could’ve betrayed what makes the series so special, hence why Tomoko’s growth was so agonizingly slow. Tomoko is, was, and always will be a loner. It was just a matter of time before she could make the most out of that status.

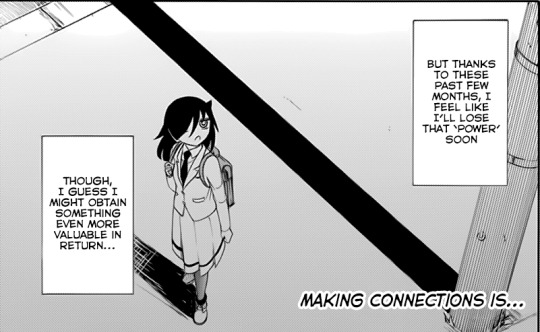

It wouldn’t be a chapter about Tomoko’s growth if she didn’t wax lyrical about her current situation.

Even if self-satisfaction about being a loner is the “goal” of this series, reality is hardly so linear. As this chapter shows, Tomoko finds herself inexplicably drawn to social situations even when trying to avoid them. Not intentionally, but out of a natural, subconscious attraction to them. Tomoko’s life is a series of circular ebbs and flows. She’ll gain something at the cost of losing something else, only to regain a variation of what was lost once what was gained becomes stagnant. Such is it the path to making connections. While the hoops in Tomoko’s development appear drastic close-up, her life is a slow, naturalistic mountain climb when viewed from on top.

#watamote#watamote review#chapter 147#no matter how i look at it it's you guys' fault i'm not popular!#tomoko kuroki#yoshinori kiyota#wada#asuka katou#mako tanaka#kotomi komiyama#yuri tamura#hina nemoto#akane okada#futaki shiki#masaki yoshida#anna haruna#rena#review

44 notes

·

View notes

Photo

L5 Contextual Studies: Queer Theory

Queer theory is an academic discipline that originates from feminist theory and gender studies during the 1990s. The theory challenges the way that heterosexuality is considered normal, it also explores the way that other identities or behaviours might considered to be deviant.

Deleuze argues that homosexuals like other minorities – women, colonized people – have to question these identities and turn away from their own questioning in an ongoing fashion. They have to enter into a permanent revolution [...] who searches not for a ‘gay identity’ or for ‘being-gay’ but for becoming gay.

Verena Adnermatt Conley, “Thirty-six Thousand Forms of Love: the Queering of Deleuze and Guattari.” Deleuze and Queer Theory. Edited by Chrysanthi Nigianni and Merl Storr (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009), 25.

Yeah, come for me. Thirty-two years later and they’re still coming for me. And what have we got? Here, where it all started, trans people have nothing. [...] And it really hurts me that some gay people don’t even know what we gave for their movement.

“Queens in Exile, the Forgotten Ones,” by Sylvia Rivera, 80-81.

We must reject a queer politics which seems to ignore, [...] the roles of identity and community as paths to survival, using shared experiences of oppression and resistance to build indigenous resources, shape consciousness, and act collectively.

Instead, I would suggest that it is the multiplicity and interconnectedness of our identities which provide the most promising avenue for the destabilization and radical politicization of these same categories.

Cohen, Cathy J. “Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics?” GLQ 3, 1997 (437-465), 459-460.

Queer Disability Studies / Crip Theory

[...] to be able-bodied is to be “free from physical disability,” just as to be heterosexual is to be “the opposite of homosexual.

Like compulsory heterosexuality, then, compulsory able-bodiedness functions by covering over, with the appearance of choice, a system in which there actually is no choice.

Robert McRuer, “Compulsory Able-Bodiedness and Queer / Disabled Existence, Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability (New York: NYU Press, 2006), 301-308

“Cripple”, when I use it, allows me to take ownership of everyone’s misconceptions of disability. I know you’re scared of me; I know you think I’m different from you, and guess what? I am. I’m owning that as best as I can when I use that word. It is a term of personal empowerment for me. I wouldn’t use it to describe another disabled person without their consent, but for me it helps me navigate the experience of disability with an honesty that I think is really important.

Andrew Gurza in “Here's What This 'Queer Cripple' Wants You To Know About His Sex Life”, Huffington Post [online] (21st July 2017).

People invent categories in order to feel safe. White people invented black people to give white people identity.

Straight cats invent faggots so they can sleep with them without becoming faggots themselves.

James Baldwin and Nikki Giovanni, A Dialogue (Philidelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1973).

Queer is by definition whatever is at odds with the normal, the legitimate, the dominant. There is nothing in particular to which it necessarily refers.

David Halperin, Saint Foucault: Towards a gay hagiography. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 62

One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.

Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex (New York: Vintage Books, 1973), 301.

Gender is the repeated stylization of the body, a set of repeated acts within a highly rigid regulatory frame that congeal over time to produce the appearance of substance, of a natural sort of being.

Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (1990)

Drag constitutes the mundane way in which genders are appropriated theatricalized, worn, and done; it implies that all gendering is a kind of impersonation and approximation. If this is true, it seems, there is no original or primary gender that drag imitates, but gender is a kind of imitation for which there is no original.

Judith Butler, “Imitation and Gender Insubordination” in Sara Salih (ed.), The Judith Butler Reader New York: Blackwell, 2004), 127.

How can a relational system be reached through sexual practices? Is it possible to create a homosexual mode of life? ... To be “gay,” I think, is not to identify with the psychological traits and the visible masks of the homosexual, but to try to define and develop a way of life.

Michel Foucault, “Friendship as a Way of Life” The Essential Works of Foucault 1954-1984, (Volume One). Translaed by Robert Hurley (New York: The New Press, 1997), 135-140.

Untimeliness dislodges queers from socially shared, normative periodicities. For those without children or ambitions to procreate, queers are cut loose not only from parenting responsibilities but from quotidian temporal rhythms that the family-orientated community imposes (school, soccer, shopping).

With the notion of queerness strategically and critically posited not as an identity not a substantive mode of being but as a way of becoming, temporality is necessarily already bound up in the queer.

E.L. McCallum and Mikko Tuhkamen, “Becoming Unbecoming: Untimely Meditations” in Queer Times, Queer Becomings (New York: SUNY Press. 2011), 1-21.

...to refuse the battle for the right to marry, to refuse the presumed connection between marriage rights and liberation, to refuse to succumb to the idea that coupled monogamy is the best way to practice intimacy. To refuse to ask for the rights that have been refused to you is to turn your back on the carrot dangled by the state and to go looking for nourishment elsewhere.

Jack Halberstam, Gaga Feminism: Sex, Gender and the End of Normal, (New York: New York University Press, 2012), 128

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

I saw your 2013 to 2017 then and now comparison post. How did you achieve such a better degree of your technique? Seems no matter how hard I try, my art always looks awful.

Hey there! The methods that resulted in faster improvement in my art were, as far as I noticed, the following: -Practice of realistic anatomy; Whether you're aiming for stylization or not, it's always important to know your bases. I HIGHLY recommend studying muscles and the way they interact with one another during different poses.-Variation; Don't draw the same thing over and over in the same position. It was important for my improvement to vary what/who I drew and attempt to do it always differently.-Knowing what I wanted; This doesnt have all to do with my artstyle but actually knowing how I wanted one particular drawing to turn out made it easier to cut unnecessary steps that wouldn't take me there and go straight to the point. That particular re-draw was a digital piece and with that new medium came a whole set of different challenges but I still have some 'tricks' that I noticed made me improve:-Not relying too much on the soft brush; It looks easier to make smoother shading with the default soft round brush but that only leaves the drawing looking blurry and smudgy, if done incorrectly. In the beginning I always forced myself to use harder brushes so I could probably learn how to render and shade. As time passed and I learned what I needed to not use the soft brush as a crutch, I began using it again. (I hope it doesn't sound stupid, it worked for me :V)-Lightning; I decided to work in greyscale so I could focus more in light sources and reflections. It's important to give the illusion of volume and to guide the eye towards the parts you want people to focus on.-Being surrouded by people more skilled than I was; Nothing kicked me more and harder to improve than seeing amazing works from other artists and wanting to achieve the same ability to create beautiful things as them. Even nowadays I try to surround myself by people who push me to become just as good as them. Follow more artists!Those were the methods that worked for me. I'm sure there is much more (and probably better) advice from other people. Personally, I believe artists that improve the fastest merely found what they wanted to do more quickly and worked their way straight up to it. Improvement is something very personal and not accurately reflective of skill. Allow yourself some room to experiment and find what you want to do. How do you want your art to look like. Also, don't get too caught up in the search for an artstyle. It's not something that pops up when you decide to, it appears as years go buy and you gather elements/techniques/aestethic that you love. Good luck!

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finally have some time to type on what I feel helped me the most in terms of improving for the past 7 years of art improvement :0

1st part would be about my art journey and 2nd part is just getting right to the point of what I feel really do help for someone to improve. So you can read either or, or both, whichever to your liking and what you are looking for!

Also just want to say that definitely even now i am still constantly learning and improving because theres always something to work on. Wanting to learn is really important for improvement!

so yea.. Long post ahead!

1)

I will admit that my 1 year art school (still studying in here), 3DSense Media School, really helped me improve the most. Not only in terms of drawing but also understanding what I am doing for each step and knowing more about the art industry im getting into. I am lucky to be in a really active class where everyone wants to improve, having amazing lovely lecturers teaching me and having constant feedbacks.

But the other 6 years weren’t really ‘nothing’. It was slow, I had no idea where I wanted to be ,what I wanted to be and do ( tbh I am still lost ), but they still helped.

From 2010 to 2013, I was just drawing for the fun of it, I drew mostly mice because of Transformice, which was fine! I had fun, it was fun drawing what i like and just slowly improving as I was inspired by the artist of that game, Melibellule.

I started wanting to take art seriously in 2014 for 3 reasons:

1) I got lucky to be able to do game assets for an unofficial game event for Transformice when one volunteer coder wanted me to do them. I had fun doing it and it made me want to be a game artist

2) I found out about FZD Videos on youtube. Until today I cant breakdown Feng’s methods and knowledge, so even though the videos was inspirational for me to make better art, in terms on how to paint like him, i didn’t learn much.

3) At this point, it seems that drawing is the only good thing I could do. Its probably a bad idea but if this is the best thing I can do, must as well make this into my career, because I would probably not know what to do or what use i can be to society so... <:9

So i wanted to improve drawing but at that point i didn’t know how, i didn’t really look for resources until 2015, and just slowly learn on the way with no understanding what I was doing. If the artwork seems nice to me at that point, I kinda take it. At this point I also made some new friends, I found new resources and inspirations and I joined a FB Group called ‘Level up!’ that give art critics (Not much anymore because it slowly became like an art promotional page which is... sad)

nothing much in 2016, I had my end of year exam then, but after that, from dec 2016 to feb 2017, I wanted to go back to the basics, so I took all the resources I know and lay them into a curriculum, which I called it Back to Square One. I didn’t finish it because by March I was studying but those did help me a lot!

and yea... basically what... happened!

2)

Everyone has their own taste and version of improvement, so I guess I have 2 answers for those that want to improve in their own way and those that want to improve in a more realistic style :0

Also before I move on, one important thing to improvement is having feedback and critics! My lecturer made an art discord that has has an art critic channel which is pretty active! you can get on in at https://discord.gg/hEpXGYU

- If you want to improve in your own way, whether if its realistic or stylize, is to find your aesthetic or visuals you like and want to put it in your art, take those things you saw and dissect it, break it down for you to learn and understand it in your own way, what part of it you like, etc. And with those info, start doing drawing studies of it, that how you remember it the most :0 My own personal preference however is to follow my 2nd advise below, to study fundamentals. because especially for styles, all these have some sense of fundamental and understanding in them, to study blindly will make you chained to it, rather than being versatile.

----

- For those of you that want to improve to do realistic stuff, i think it has been said a few times but definitely work on fundamentals! I suggest for beginners to look into Linework, this also comes with Perspective 1st and seeing in Volume. I recommend watching Scott Robertson, moderndayjames and [the design sketchbook] videos on youtube. They have really good exercises to having controlled, nice lineworks and help you think in perspective!

Then get yourself to learn on Lighting, many artist have different ways of understanding light but personally I like understanding them on how light makes us see things. One of my painting methods follows quite similar to this tutorials i found! Sam Nielson takes into consideration on how shadows and cast base of where the light hits, how to see the object as a 3d object and cast shadows, etc.

Material is something i would recommend you to look into improving! Do material studies, find out how one thing looks like metal while others looks matte.

And then of course, Anatomy. I would prefer you to start learning some human anatomy, so know your terms, how and where they are placed, how the bones connect, etc. Start from knowing proportions, then simplified shapes, individual muscles and then naming. Your knowledge of knowing what bones and muscles there are can be really useful for animal anatomy (bird, vertebrates) because there are some of the same parts that are in humans too!

There are many MANY more stuff but I think these few can help you in a long way!

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

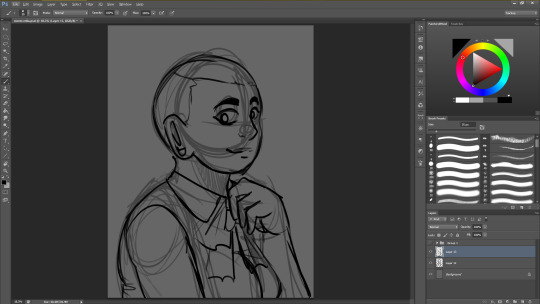

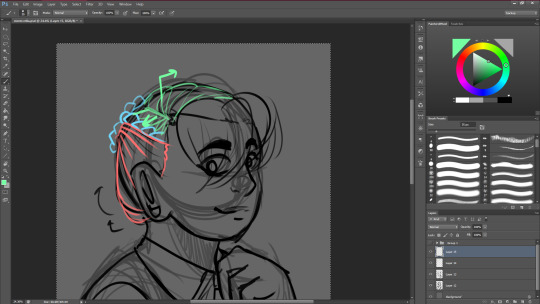

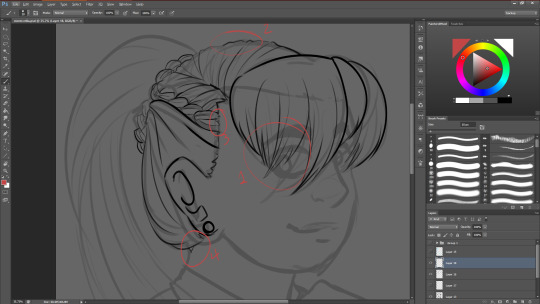

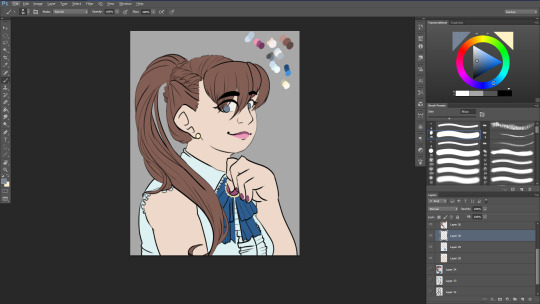

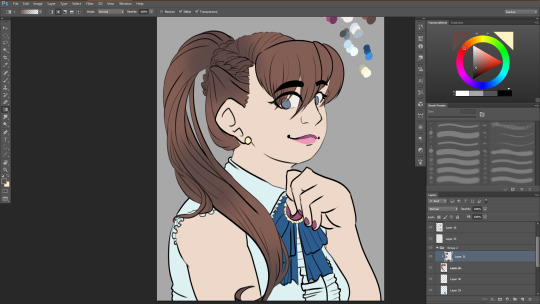

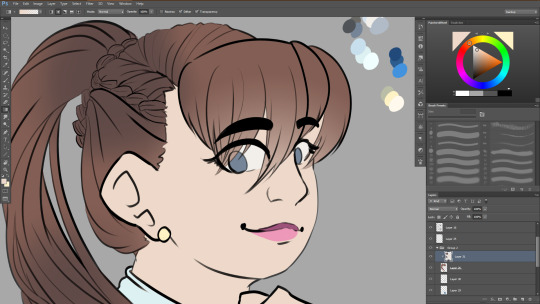

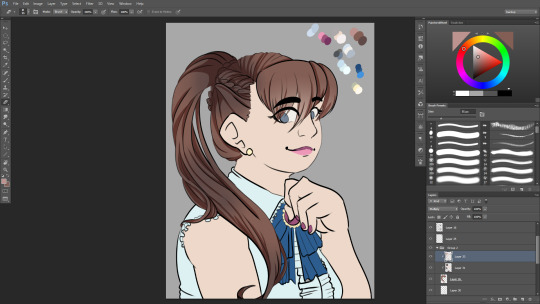

in your art tutorial (which was awesome and helpful btw) you had an example which i believe was the last one of a person with a long ponytail and honestly the way their hair looks in that fascinates me so i was wondering... how did you do the thing ? im rubbish at hair .

First of all thanks! I’m going to try and roll both a tutorial as to how I draw that particular hairstyle as well as an overall hair tutorial, aight?

when it comes to that sorta thing I draw a rough sketch first (sometimes i don’t out of habit, but with unfamiliar or more complicated hairstyles it never hurts to have your hairline down

I also lay down where the parts in the hair are (rella specifically has kinda roundish bangs along her forehead)

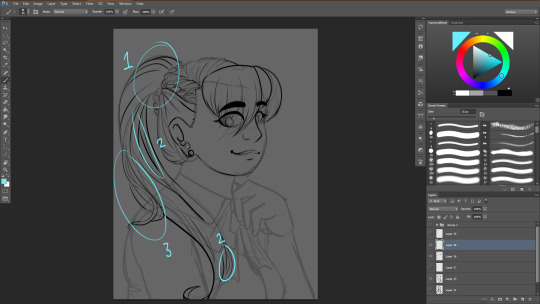

ok so a lot of more anime-ish hairstyles can be broken down into different parts

rella has:

the bottom part of her hair (red, which is a little closer to her skull and comes off of it a little bc That’s Just What Ponytail Hair Does unless it’s a really tight one or something)

a braid along each side of her hair that meets around in the back (blue, it’s relatively stylized because I don’t want to draw a lot of strands All The Time)

the Rest of It (green) which is essentially just hair going from the part into the braid or into the other side of her head

she also has a ponytail

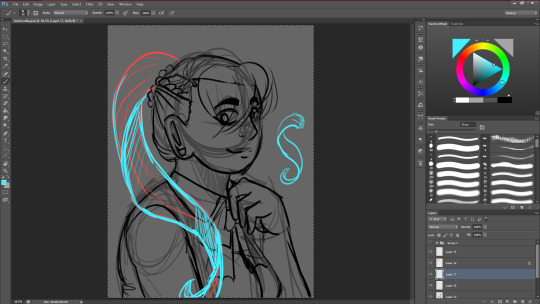

the way i stylized it basically makes her hair really ribbonlike in shape but it’s also really thin in shape and texture so it’s easier to play with in terms of shape and volume

if i were to make it thicker hair, this is how i’d do it: a lot closer to tufts as opposed to strands, though when shading, i’d follow more or less the same ribbon shape (with respect to the bumpy shape of the tufts of course)

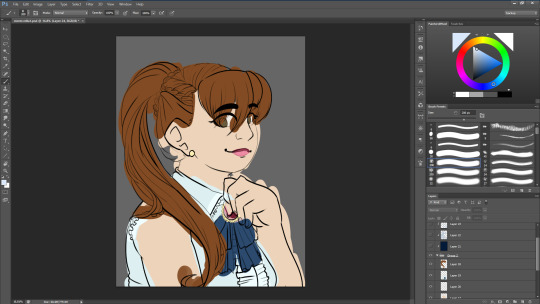

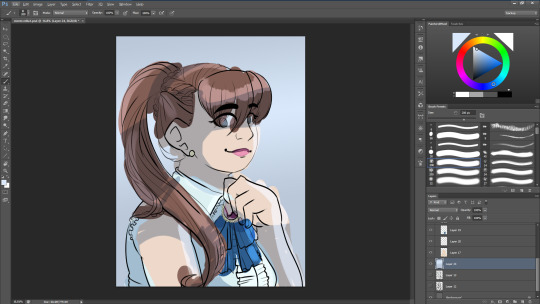

when i’m done with all of that, i normally merge my sketches and make them transparent and i take a brush and start lining (this one i just used is this one, it’s my only downloaded brush pack and that’s just because i’ve been using it for so long tbh)

little detail things that i do:

divide the hair into mini strands as you see fit, define it!! especially on shorter, tuft-ier hair (like in rella’s bangs). generally i define it more where more shading is, because that gives me more of a baseline as a whole.

hair is like fabric but it’s on your head. and your head is round, so rumple it! make it come up OFF of the head, make it emphasize the shape of it! it’s a wonderful way to make it realistic just by making it a little ruffly

hairlines are not always super clean cut. jag em up! show where individual follicles are being pulled if u Gotta.

for the back hair: pretty much always show it going into the background. the more you indicate that there is DEPTH to the hair, the better it works.

more detail things but more actual bodies of hair:

do whatever you can to continue to indicate that the hair is 3-dimensional. make it twist around corners, make it move and spill together. have fun this is the payoff

separate it! it’s a very art nouveau look, plus it makes it look to actual hair with strands moving and doing their own thing

have hair not only break away from the bigger body, but also have it interact with obstacles. hair does that

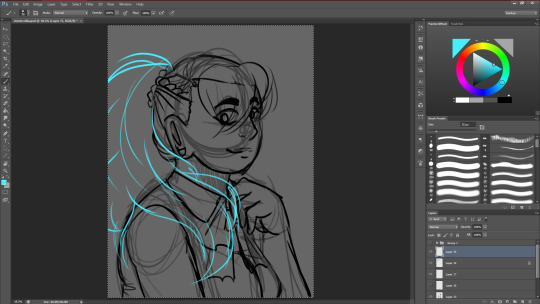

rella has auburn hair, and i just randomly picked out some colors that seemed legit, if not a little ugly

screen layer + multiply + overlay + a background to set the mood

im making a palette out of this

ok with the base colors all flatted in, i’m finally ready to actually…color the hair

there are several ways to go about it this time around i’m blocking it large areas with (circular) gradients. it’s a trick i picked up from studying how himaruya (the artist for hetalia) does things and I think it lends itself pretty well to a silky hair texture.

i also took her skin color and used it right next to the bangs to make them look more transparent

i took the highlighter color from the palette i made and blocked in some soild shadows on a multiply layer. i’m probably going to change up the colors after a bit to make it look nicer, but for now, this will do just fine!

i did the same with the highlight and an overlay layer. it looks a little off right now, but i can always change it later.

i ended up not using the palette as much as i thought (which is ok! it happens) and i locked the layer with the shading on it so i can just go in with a light blue instead, so that it looks more unified!

and there!

this last bit is optional because black lines look fine but a style thing to consider is coloring the lines, which i did here:

and yeah that’s how i do hair

#burned-toast#answered ask#hair#how to draw hair#anime#anime tutorial#hair tutorial#help#art help#art tip#digital art#lineart#ponytail#braids#long post#long tutorial#anime hair#gabriella acerbi

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

Learning characters development and design - Mary Jane Begin

1) Introduction to Character Development

The instant read

“Deconstruct the visual information” “The first thing we see is the overall silhouette or shape of the character as a first impression of the personality” Key elements to understand good character design- “ Shape, facial expression, body gesture, movement, colour proportion context and contrast.”

Capture the heart and soul of a character

“Start with the back story or descriptions and understanding the context of a character... Playing with variations in proportion, costume and overall shape are key to good design. Keeping your sketches loose and full of expression and making plenty of notes before settling on your final design.”

Tools of the trade

“Carter Goodrich - Explores characters without colour to keep the focus on the character's structure.”

“Nico Marlet - uses pencils and markers to capture his fluid and organic character designs these materials allow for a clean , graphic presentation while still displaying his pencil line”

“Thinking about colour early on is critical for some artists”

“Nick Kole works with a blunted pencil on small sketches at first to keep his sketches loose and quick. He then scans and enlarges the strongest sketches, then starts putting a finished together digitally.”

“No matter what material you use, the key is keeping the method as simple and direct as you can.”

2) Elements of Developing a Believable Character

Archetypes

“Archetypes display stereotypical personalities, behaviours and characteristics regardless of how unique they may seem initially.”

“Archetypes help to give you a place to start when figuring out what type of character you’re trying to develop.”

Classic Archetypes- The Hero, The Villain, The caretaker, The innocent, The ruler, The sage and the trickster.

“Understanding archetypes as part of our visual language is essential, especially when you break from expectations to create a complex, dimensional character.

Keep it real

“The first go-to source for a characters design is to look to available subjects to draw inspiration from.”

Motion

Imagining how you think your character might move if it were animated can help establish both authenticity and define personality.

“Creating gesture drawing from life and looking at the movie frame by frame to help you study movement.”

Environment

3) Character Construction

Shapes and Silhouettes

“No two characters should have the same silhouette”

Gesture and Silhouettes

“The overall body posture of a character speaks volumes about the personality and life of a character.”

Anatomy and Proportion

Stretch and exaggerating portions

“Anatomy in proportion convinces the viewer that your invented creature is real and believable.”

Turnarounds

Facial Expressions

Research the details

Research things related to what you are creating e.g Dragons- research lizards, bats.

Colour basics

“Limited colour palette”

Utilizing contrast to create definition between colours is one of the key element using colour wisely. “

Colour your character

“A colour palette that expresses your character’s personality can be a critical element to the exploration of character development.”

4) Style meets Substance

Explore a character in a variety of styles

Carlos Grangle “If you’re a designer, you have to be able to develop the stylization to reflect the characters of the script.”

Characters in context: Designing a cast

The art of invention: Making fantasy creatures believable

“Designing a cast ensemble means balancing different types of characters choosing a variety of shapes and proportions and costumes and colours helps make an ensemble cast more interesting and inviting to the viewer.”

Sidekicks, villains and foils

From 2D to 3D

“For a final 3D result you wanna pay extra attention to different angles of the character trying to make sure that that the mass and visual impression of their shape, colour and silhouette hold up from every angle and not just the front.”

Character in sequence

Riffing on the classics

What I’ve learned from this course

In my previous post I said the next course I was going to do was one about rigging by George Maestri however, looking through some of the course titles and a quick look at some sections such as the facial rig the course seemed to be very similar to the tutorial we where given by Mario with the only difference being creating and IK to FK switch however it wasn’t worth a 4 hour course just for that information.

I then ran into trouble of finding a new course to run as most of the ones I found seemed to go over topics covered in the course we were given or what I’ve been taught in class.

In the end I found this tutorial which I thought would really help me with my current summer project and future projects and Overall I found this course to be insightful in certain areas as there was piece being shown from beginning to completion.

The course breaking down and analysing how certain characters like Dracula (Hotel Transylvanian) and how they are so recognisable through their silhouette but the sections I found the most beneficial was the section about archetypes and how they can be used to create new interesting characters and is something I plan to incorporate into my current TV show designs. Another section I found benificial was the section about research as it the examples where around the fantasy genre using researching thing related to what you want like looking at lizards for a new dragon design.

While the course did tell me some things I already know like about proportions being around 7, 8 heads tall how to do turnarounds and gave a source for figuring out expressions I was already aware of. I found the insight into the process and breakdown of characters and what makes there designs so likeable and recognisable is something I think I can take and hopefully improve my character designs.

0 notes

Text

Courthouse ‘Warrior’ or Diplomat? The Public Defender’s Challenge

Give The New York Times credit. When it comes to exposing our indigent defense crisis, the paper keeps at it.

Last month, reporters Richard Oppell, Jr. and Jugal Patel produced a story that introduced readers to a public defender in Louisiana with a list of pending cases long enough to require five years’ work, and to bewildered indigent clients in Rhode Island who received one to five minutes of defender counseling at their first court appearance.

The Oppell and Patel survey was given prominent placement. The Times digital edition deployed interactive features. Photographs of 113 of one defender’s 194 clients were published to give human faces to the numbers. It was a serious piece.

Still, while I don’t enjoy saying this, I’ve been doing public defender work for 45 years, and I have read variations of this story 200 times. The caseload count is worse now in many places than it was in the mid-1970s when I first got involved.

I’m not sure this story—and the legion of stories like it— will make a difference on their own.