#i have the first one in english second one i have the catalan translation third one is a catalan author

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#i have the first one in english second one i have the catalan translation third one is a catalan author#aquest any encara no n’he llegit cap de la rodoreda#a poc a poc els vull anar llegint tots encara que trigui 3 segles

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

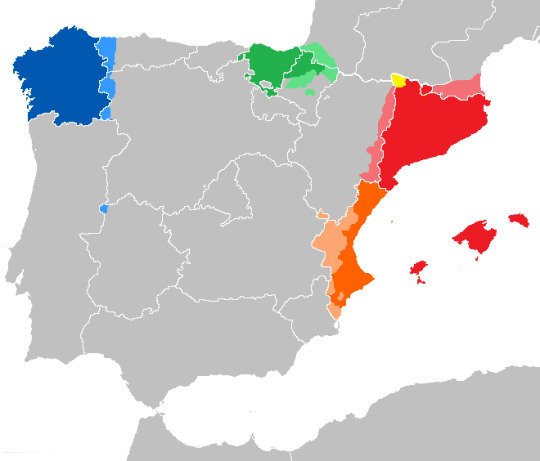

today is yesterday was the international mother language day, so i thought i could make a post about the languages spoken in spain!

all of this data will come out of wikipedia, so i'm sorry if there's something wrong. i now realise i could've planned this way more, it's my bad honestly, i'm sorry.

anyways, let's start with the mother tongue map of spain; each color represents one language:

light green: spanish, galician: blue, catalan: orange, euskera: grey, aranese: red, asturleonese: green, aragonese: yellow.

the blue dots in extremadura are fala (then northernmost one), and most likely portuguese like the one spoken in olivença (thanks @satyrwaluigi).

by comparision, here's a map with the recognized co-oficial languages (spanish is the national language, and in various regions some languages have a co-oficial status)

the lighter colours refer to different categories depending of the language:

lighter blue refers to areas where galician is recognized as a minoritized language but isn't co-oficial

lighter green refers to areas where euskera is recognized as a minoritized language but isn't co-oficial

lighter red refers to areas where catalan is spoken but isn't co-oficial

lighter orange refers to areas where valencian is the official language but isn't spoken.

the reasoning behind the separating catalan and valencian into two distinct languages is a complex one, if you want more info @useless-catalanfacts made a great post about it (and here is even more info about the topic they very nicely provided me with). in a nutshell, valencian is not a distinct language from catalan and the reason why it's listed as such is political.

as you can see, there are some languages, mainly aragonese and asturleonese, that aren't recognized as co-oficial languages in their respective regions despite the large number of speakers. this makes them especially vulnerable to linguistic colonialism, and is why thousands of peoples from those areas are fighting in order to make their languages official in the state's eyes. if someone knows of organizations or groups that are involved in this movement, please let me know and i'll add them to the post.

apart from the aforementioned catalan blog, here in tumblr there's really great blogs about iberian minoritized languages; i personally recommend @beautiful-basque-country and @minglana for euskera and aragonese respectively, but i am sure there's more.

also, there are some languages that are not even mentioned in the maps despite its critical situation that i thought i should remark here:

fala, as stated before, is spoken in the borders between portugal and extremadura and it heavily borrows from portuguese. it has an estimated 11k native speakers.

caló is the language of the iberian roma people. it has an estimated 60k native speakers between spain and portugal.

darija, the arabic variant native to morocco, is also spoken in ceuta, a city of 80k inhabitants.

tarifit / riffian, a tamazight variant spoken in the rif area of northern africa, including the city of melilla, with 86k inhabitants.

finally, apart from the autochtonous languages, there are also several languages brought by the migrant population, who should also be counted in this post. here are all the languages spoken in spain; the first number is of native speakers, the second one of non-native speakers, and the third one is the total:

the languages translated into english are: spanish, catalan / valencian, galician, arabic, romanian, euskera, english, german, portuguese, asturleonese, italian, bulgarian, wu chinese, french, spanish sign language, aragonese, caló, catalan sign language, basque sign language, riffian, aranese, fala.

#spain#iberia#languages#spanishmaravillas#i'm no longer gonna use typicalspanish cause there's a blog with that name that i may or may not be involved with#so i'll tag my posts with spanishmaravillas from now on

112 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Hello @kjaerekrake! I hope you’re having a good winter break and holiday season! Here is your Secret Santa present, I hope you like it :)

I saw that you like music and that you play guitar, so I thought maybe I would find a tutorial for playing music in Spanish, that way you can practice your Spanish and hone your musical talents at the same time! This is a tutorial for playing “Sofia” by Álvaro Soler, and here is some music vocabulary for the song in Spanish and Catalan (since you said you wouldn’t mind a gift related to it and I will never not take someone up on an offer to teach Catalan):

el tema (m) / la canción (f) - el tema (m) / la cançó (f) - song la estrofa (f) - l’estrofa (f) - verse el puente (m) - el pont (m) - bridge el estribillo (m) - la tornada (f) - chorus el ritmo (m) - el ritme (m) - rhythm el acorde (m) - l’acord (m) - chord la cuerda (f) - la corda (f) - string el traste (m) - el trast (m) - fret la cejilla (f) - la celleta (f) - capo

sonar - sonar - to sound rasguear - puntejar - to strum parar - to slap cambiar - canviar - to change repetir - repetir - to repeat

menor - menor - minor mayor - major - major sostenido - sostingut - sharp bemol - bemoll - flat

NOTES OF THE SCALE: do - do - C re - re - D mi - mi - E fa - fa - F sol - sol - G la - la - A si - si - B

**Note: In Spanish and Catalan the chords are written using these notes, so for example, an A minor chord in English would be Am but in Spanish and Catalan it would be Lam.**

I also transcribed and translated the video below the cut if you want to practice your listening comprehension skills. I hope this is useful to you and if you have any questions, don’t hesitate to ask! Happy New Year :)

Muy buenas! Bienvenidos a mi canal y bienvenidos a este vídeo en qué os voy a explicar tocar “Sofia”, este tema que hace Álvaro soler y está muy de moda este verano. Así que, bueno, espero que os sirva de algo este vídeo y si así podéis dejarme vuestro Me Gusta y suscribir al canal si todavía no lo habéis hecho, y si tenéis cualquier duda de lo que sea de esta canción o de cualquier cosa, pues me lo dejáis abajo en los comentarios, que siempre los leo y siempre los respondo. Y bueno, sin enrollarme mucho más, dentro vídeo!

Los acordes que vamos a encontrar en esta canción son cinco y son muy sencillos. El primero sería un si menor, el segundo sería un re, el tercero un la, el cuarto un sol, y también en el estribillo nos vamos a encontrar a un mi menor.

La primera parte de esta canción que vamos a aprender sería la estrofa, y la estrofa sonaría así. O también la podríamos hacer con este ritmo, que es algo más fácil.

Para hacer el primer ritmo lo que tenemos que hacer es poner el primer acorde que sería un si menor y vamos a usar rasgueo hacía abajo, parando las cuerdas. Ahora subimos, paramos de nuevo las cuerdas, subimos, paramos de nuevo, subimos, y por último paramos y subimos. Sería cuatro veces y sonaría así.

Cambiamos al segundo acorde que sería un re y hacemos lo mismo. Paramos, subimos, paramos, subimos, paramos, subimos, paramos, y subimos. El siguiente sería un la. Y por último un sol mayor.

Y para que no os enganche [not correct but I can’t tell what he’s saying] este rasgueo que es algo más complicado tenemos la segunda opción que sería esta. Lo que vamos a hacer es rasguear dos veces hacía abajo, dos hacía arriba, y ahora uno hacía abajo y otro hacía arriba. Cambiamos a re, y lo mismo. Dos hacía abajo, dos hacía arriba, y ahora uno hacía abajo y otro hacía arriba. Y sol. Y algo más rápido quedaría así.

La siguiente parte que vamos a aprender sería el puente, es la parte que va delante del estribillo, y sonaría así. O también lo podríamos hacer de la segunda manera que sería esta.

Para hacer la primera forma empezaríamos por el acorde de sol mayor y lo que vamos a hacer es el mismo rasgueo que al principio, es decir, paramos las cuerdas, subimos, paramos, subimos, paramos, subimos, y paramos, y subimos - cuatro veces. El siguiente acorde sería un si menor y el último sería un la. Uno, dos, tres, cuatro, y repetimos. Uno, dos, tres, y cuatro. Por lo tanto en la sería ocho veces.

Y el segundo ritmo sería los mismos acordes pero con un rasgueo diferente, el rasgueo que hicimos anteriormente. Sería este. Son dos rasgueos hacía abajo, dos hacía arriba, y ahora uno hacía abajo y otro hacía arriba. Cambiaríamos a si menor, y a la, y en la se vuelve a repetir este rasgueo. Y todo esto se vuelve a repetir.

Por último vamos a aprender la parte del estribillo. Nuestro estribillo quedaría así. Empezaríamos con el acorde de sol mayor y lo que vamos a hacer son dos rasgueos hacía abajo, dos hacía arriba, y ahora uno hacía abajo y otro hacía arriba. Sería así. Cambiamos a re y hacemos lo mismo. El siguiente sería un la. Y por último un mi menor. Y esto mismo se repite hasta que acaba el estribillo. Y con esto ya tendríamos todo este tema completo.

Bueno, espero que os haya gustado este vídeo tutorial y espero que os haya servido de algo. Y si así como siempre digo podéis dejar vuestro Me Gusta, suscribir al canal si todavía no lo habíais hecho, y si tenéis cualquier duda de lo que sea de esta canción, de otra, o cualquier cosa que me tengáis que decir, voy abajo a tener los comentario para decirmelo y además siempre los leo y siempre los respondo. Aquí lo dejo por hoy, os espero en el próximo vídeo como siempre, así que un beso y hasta la próxima!

Translation:

Good afternoon! Welcome to my channel and welcome to this video, in which I’m going to explain to you how to play “Sofia”, that song by Álvaro Soler which is really popular this summer. So anyways, well, I hope this video helps you and going off that, if you could like this and subscribe to the channel if you haven’t already, and if you have any question about anything to do with this song or anything, well, leave it below in the comments, because I always read them and always respond. And, well, without further ado, the video!

There are five chords that we’ll find in this song, and they’re very simple. The first is B minor, the second is D, the third is A, the fourth is G, and also in the chorus we’ll find E minor.

The first part of the song that we’ll learn is the verse, and the verse would sound like this. Or we could also play it with this rhythm, which is a bit easier.

To play the first rhythm, what we have to do is put down the first chord, which is B minor, and we’re going to strum downwards, slapping the strings. Now we’ll come back up, we’ll slap again, come back up, slap again, up, and finally slap and up. You would do that four times and it would sound like this.

We’ll switch to the second chord, which is D, and we’ll do the same thing. Slap, up, slap, up, slap, up. The next would be A, and finally G major.

And so that you don’t get stuck on this pattern, which is more complicated, we have the second option, which would be this. What we’re going to do is strum downwards two times, upwards two times, and now one downwards and another upwards. And we’ll switch to D and it’s the same. Two downwards, two upwards, and now one downwards and another upwards. And G. And a bit faster would sound like this.

The next part that we’re going to learn is the bridge, that’s the part that comes before the chorus, and it would sound like this. Or we could also do it in the second way, which would be this.

To do it the first way we would start with the G major chord, and what we’re going to do is the same pattern we did at the beginning, that is to say, we slap the strings, come back up, slap, up, slap, up, and slap and up - four times. The next chord would be B minor. And the last one would be A. One, two, three, four, and we repeat. One, two, three, four. So we would play the A chord eight times.

And with the second rhythm it would be the same chords but strummed differently, the way we did it before. It would be this. Strum down twice, up twice, and now one down and another up. We change to B minor, then to A, and for A the pattern is repeated. And all of this gets repeated.

Finally, we’re going to learn the part for the chorus. Our chorus would end up like this. We would start with a G major chord, and what we’ll do is strum downwards twice, upwards twice, and now one down and another up. It would be like this. We change to D and do the same thing. The next chord would be A. And finally E minor. And this is repeated until the chorus ends. And with that, we have the whole song down.

Well, I hope you liked this tutorial video and I hope it’s useful for you. And if, as I always say, you could like this video, subscribe to the channel if you haven’t already, and if you have any questions about anything for this song, for another, or anything else you have to tell me, I’m going to have the comments down below for you to tell me it, and apart from that I always read them and I always respond. I’ll leave it at that for today, I’ll be here for the next video as always, so a kiss and until next time!

#i hope you enjoy it :)#i was going to do bajo el mismo sol but i thought this had better vocabulary#i also have no idea how to play guitar so if any of this makes no sense i'm sorry#i would have done piano but i couldn't find a good tutorial for it in spanish#also my spanish is really rusty so i probably spelled something catalan-ly#but i did try to avoid that#langblrsecretsanta2017#spanish#music#translation#vocab lists#general:music#general:translation#general:vocab#general:reference#spanish:reference#spanish:music#spanish:vocab#catalan:vocab#spanish:general

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

it’s time i made an Actual record of the degrees george has, and the languages he knows, since fuck this guy is too intelligent for his own good.

this got long so i read-mored it.

i should preface this by saying, yes, george is only 29, and yes, he did most of this in about a decade. he did start college early, at 16. but the reason he was able to get so many degrees so quickly is because he was avoiding society due to guilt over his brother’s death and the accompanying estrangement from his family. he threw himself into his studies, and had a natural mind for languages so a lot of the time he was able to finish his degrees early. he didn’t have spare time, it was all spent researching and memorizing and studying. academics were safe, they were his comfort, and he needed them, so he refused to stop, and whenever he felt he was capable of taking on more, he did. he is incredibly intelligent, but he is not what most would call a ‘genius’. while languages come incredibly easy to him, for the most part he has had to put in hours of work, and only through his own high expectations of himself and his desire to overachieve did he manage to stay sane through his intense journey. also, for the most part, he did survive off of scholarships, though he also spent a lot of time tutoring and working as a teaching assistant.

he first double majored in linguistics and ancient studies, focusing primarily on pre-christianity history, with minors in general theology and philosophy (graduated in 3 years with extensive summer school, done at 19)

he then did a masters/ph.d joint program in ancient history & archaeology which cemented his fluency in latin and ancient greek, and included specializations in epigraphy and papyrology (a combined 5 year program)

when his masters portion was done (at 21), he took on a second ph.d and a third bachelor’s in translation studies and ancient languages respectively, with a primary focus in aramaic and like languages, which added 4 more years to his studies (completing his first ph.d a year into this, at 22, and then completing the bachelor’s at 25 and the second ph.d at 26)

it was at some point during this second ph.d that he met scarlett (around age 24), another avid learner who was in the middle of her own second ph.d, having obtained a ph.d and master’s already. her interest in his ability to decipher languages started their relationship and had george actually leaving the academic scene (in presence, not in credits) to follow her around on her pursuit of the philosopher's stone, and he used their adventures as the basis for his dissertation of said second ph.d.

her determination to do whatever it took to get the stone rubbed against his desire for sticking to the book, and this eventually led to them parting ways midway through george’s third ph.d (in science & religion), since she kept getting him into trouble that was beginning to affect his academic performance. though only several months later scarlett showed up again to ask for his help (age 28), which resulted in them literally going to hell and fighting for their lives to escape. upon returning, george attempted to finish his third ph.d, but struggled due to nightmares about nearly dying and about watching others die gruesome deaths, and eventually cited mental exhaustion and took a semester off.

once he and scarlett broke up the second time, george needed a distraction, so he began to work remotely on finishing his last degree, and while he did also do some freelance translation work, due to his inability to sleep and his general anxiety about everything, he managed to complete his degree only a few months later, now 29.

this happened only a few weeks before he met @interphrase‘s nick, and it was because nick helps him feel in control of things again that george has not disappeared back into academia. he’s much too busy learning magic now.

alright, now lets move on to the languages the george knows. this is by no means an extensive list, and at any given point he is learning more (to various degrees), but these are the ones he has the easiest time with or likes the best

so, full fluency in:

english, obviously

french

spanish

german

latin

ancient greek

aramaic (and languages that are considered precursors/successors, such as hebrew/arabic, since it’s relatively easy for george to recognize the changes)

advanced reading comprehension but not complete fluency:

dutch

russian

ancient egyptian

italian

portuguese

conversational at best:

chinese (cantonese and mandarin)

korean

swahili

various other dialects, like creole or catalan in which he knows enough to get by but would probably require a translator for the majority

#yo i just spent like an hour researching actual degree titles and lengths of the degrees#to make sure this was possible#it is! but it's insane and george is insane#i love school but even i would go a bit mad doing all that#although i guess i'm not super far behind#;;georgecanon#okay anyway

0 notes

Link

MARY ANN NEWMAN STILL LIVES in the same apartment she was born and raised in. That apartment happens to be in Chelsea in New York City, and it also happens to be part of the reason she fell in love with Catalan and Spanish literature.

The neighborhood she grew up in wasn’t the glamorous, prohibitive destination it has become, but rather a working-class neighborhood where she heard and saw Spanish on the streets as often as English. She later became enamored of Spanish literature and went on to discover Catalan culture and history. She has since devoted her life to being an ambassador of Catalan literature and has been justly rewarded for it. A celebrated translator, editor, and cultural critic, she is the director of the Farragut Fund for Catalan Culture in the US.

I first encountered Mary Ann Newman’s work when I read her translation of Quim Monzó’s novel Gasoline (Monzó is the previous interlocutor in this series of conversations on Catalan literature). My husband, Leonardo Francalanci, a Catalan scholar, had just taught her translation of Josep Maria de Sagarra’s Private Life, an epic chronicle of life in Barcelona before the Spanish Civil War. She has also translated a short story collection by Quim Monzó, essays by Xavier Rubert de Ventós, and a collection of poems by Josep Carner. In this interview, we talk about translation as an embodied practice, her journey from New York City to Barcelona, the contemporary Catalan crisis, and the evolution of her love affair with Catalan literature over the years.

¤

AZAREEN VAN DER VLIET OLOOMI: When did you first travel to Catalonia and become aware of it as a region with a cultural identity that is distinct from the rest of Spain?

MARY ANN NEWMAN: I went to Spain in 1972, at 20, for a junior semester abroad. I knew there was such a thing as Catalonia, and Galicia, and the Basque Country. There had been Galician children in my grammar school in New York in the ’50s. West 14th Street was still known then as Little Spain, and I lived on West 16th Street. One day in high school, as other students were being drilled in conjugations, I started leafing through the Spanish culture text we never cracked, and read that there were four languages in Spain — Spanish, Catalan, Basque, and Galician. I remember perfectly the hand-drawn map of the Iberian Peninsula with the regions outlined.

These little bits of information — the Galician classmates, the map — are like iron filings: when you finally encounter the magnet of the culture, they jump into shape and become meaningful. They allow you to be attentive to difference.

During my semester in Madrid, I took a train to Barcelona. It was love at first sight, with the landscape, with the architecture, with the quality of the light and the sky. And with the sound of the language. I felt the difference right away. It was easy to make the leap from there to the distinct cultural identity.

I tend to think of acquiring a second or third language as entering into a love affair: the process is enigmatic, visceral, and powerful enough to shift our sense of identity. Can you describe your love affair with Catalan? When did you start learning Catalan, and why? How is it different from your relationship to Spanish?

I think it’s contiguous with my relationship to Spanish. One’s reaction to cultures, cities, landscapes, and languages is, or can be, as intense and visceral as it is to people and lovers.

My love affair began with Spanish. I love the Spanish language, its immense variety, all the cultures that fall under the rubric of “Hispanic,” even the conflicted history of its relationship with the languages it has suppressed. I grew up in a very bilingual environment — at the grammar school I mentioned before, St. Francis Xavier, a large proportion of the children were of Latino origin, mostly Puerto Rican. My neighborhood was full of stores with “Spanish” products — “Spanish” covered everything in those days. My first childhood encounter with a foreign country was Cuba, where I learned my first words in Spanish, tasted my first rice and beans, and absorbed some sort of deep-seated familiarity, a sort of subcutaneous recognition, with Hispanic culture. Later, as an adult, Spanish allowed me to take a distance from monolingual American culture, to see the United States from another, often disapproving or denunciatory perspective. I moved from this general love of Hispanic culture to the specific enchantment with Catalan culture, which, in turn, gave me perspective on Spanish. They are not entirely at odds. For most Americans, Spanish (in the broad sense my neighborhood applied) is the gateway to Catalan.

This was very organic and informal. I started learning Catalan in 1976, in Madrid. I was completely smitten with the culture. I had developed wonderful Catalan friendships in New York, with people who loved to talk about their hometowns (Barcelona, but also Valls, Tarragona…). I attended two classes in Madrid, the only two classes I ever took, at the Círculo Catalán. My classmates were all young madrileños, political progressives who loved Lluís Llach or Raimon, who expressed their solidarity with the Catalan people by learning the language.

In 1977, I moved to Barcelona and started speaking Catalan with everyone who would put up with me. Back in New York, in 1978, I bought Alan Yates’s Teach Yourself Catalan — I still highly recommend it — and did just that. I got a group of friends together, I would study up a chapter and teach it to them. It worked. I learned the grammar. But the passion for the language was already deep, and everything I had learned by living in Catalonia only reinforced it: the markets, the architecture, the politics — 1977 was the year of legalizations, the year of the Anarchist Days, the first LGBT demonstration, the first mega-demonstration in favor of the Statute of Autonomy and the release of Catalan political prisoners. It was the perfect year for a young American progressive to be initiated into Catalonia. Above all, I started reading: Salvador Espriu, Mercè Rodoreda, Biel Mesquida. If you know another Romance language well, you can read before you can talk, and when you start talking, all that reading — the words, the sentence structures — is at your disposal.

What was the first book you read in translation? And the first book you translated?

It was probably Grimm’s Fairy Tales. I loved them and read them over and over. I remember loving Babar the Elephant. My first grown-up reading was an immense collection of stories by Guy de Maupassant. Of course, this is all in retrospect. I had no idea I was reading translations — they were just books I loved. In high school, I discovered The Stranger and The Trial (which I loved) and Steppenwolf (which I hated), and all the books that thrill an inquiring teenager. And in freshman year of college, One Hundred Years of Solitude (I borrowed it from a lending library in a tobacconist on 8th Street for 25 cents) was what convinced me to major in Latin American literature. It was a lightning bolt.

The first book I translated was O’Clock, by Quim Monzó.

What do you think the art of translation has in common with the art of listening? Do you consider the process of conducting a translation to be an embodied experience?

It is for me. But so is reading itself. And translation is the most radical form of reading, the most deep-rooted.

When you read, you can sort of slide by things that are opaque. When you translate, you can’t slip by, you have to dig down to understand them, and it involves all the senses: What is this character seeing, smelling, feeling (both touch and emotion), hearing? What were people wearing?

This is the empiricism of translation: it entails a trial and error, a continuous editing and rereading. All of which is very physical; it cycles back and forth between rationality and instinct. Many language devices are unconscious or even pre-conscious; unremembered things, words, concepts rise to the surface when they are called up by the translation. It has a psychoanalytic quality.

How does your relationship to the translation change depending on whether you are working with a living or dead author?

I think it doesn’t. My relationship is with the text, and with the author insofar as he or she inhabits the text. It’s wonderful to be able to consult with the author, and my two living authors, Quim Monzó and Xavier Rubert de Ventós, were always very helpful, but in the end, it’s my job, and my book. You can only hope the author approves.

How did you happen to start translating Quim Monzó?

I was living in Barcelona in 1980 on a Fulbright, and reading everything I could. Quim’s books were breaking all the molds in Catalan literature, and in world literature. I met Monzó there, but, even more fortunately, it turned out that he was going to spend the following year in New York. In New York, I proposed a translation, he agreed, I put together a dossier with three stories, bio, et cetera, sent them to an agent, who loved them, who sent them to a publisher, who loved them … It was deceptively simple.

What is the most enjoyable part of translating Monzó, and what is the most challenging?

As often happens, the most enjoyable and the most challenging come together. Quim’s writing is very approachable, very readable, so the quality of his art can be imperceptible. Through translation, it becomes evident. His writing is spare and dense. His sentences are reduced to the absolute minimum, but packed with meaning. There is no extraneous matter. To render this in English should seem like a no-brainer, but English is dense and spare in a different way from Catalan, and they don’t always overlap. It’s a challenge, but it’s also great fun to crack the code.

How was translating Josep Maria de Sagarra’s Private Life different from your other translations? Did you have to do historical research?

It’s useful to compare it to Monzó. Sagarra is the grand pre–Civil War chronicler of Barcelona. He set out intentionally to write the great Catalan novel, to hold Stendhal’s mirror up to the life of the city. And he wrote this broad, florid, marvelous tapestry, with billowing sentences and a plethora of adjectives and adverbs. It was a blast to translate.

I had some knowledge of the period, so the research was more of a deep dig: sometimes it seemed as if he were using a photograph to evoke a scene, and in a number of cases I actually found the photograph in question. There were a few mystifying passages and references that I was able to track down and, in one case, flesh out — a bit of creative editing that might be considered controversial. It was interesting: after my first draft, I read the Spanish translation. I was sure it would resolve my doubts. But the apparent closeness of Spanish to Catalan allowed Manuel Vázquez Montalbán and José Agustín Goytisolo to translate obscure passages literally, which I couldn’t do in English. Still, the detective work was a lot of fun. So, the interesting thing about going from Monzó to Sagarra, is that Sagarra is splendidly sweeping and baroque, and Monzó is perfectly minimalist and spare, but they share a sensibility, a willingness not to prettify the subjects they portray. It feels like a Catalan sensibility, certainly a Barcelonan sensibility.

How has your work as a cultural administrator and translator changed since the Catalan referendum?

It hasn’t affected me, professionally, but it has affected the people I deal with.

Personally, and professionally, it is distressing to perceive the normalization of a kind of pessimism. Life goes on, everyone does his job, Catalonia prospers, but there is a cloud hanging over people’s heads, and a subtle brake on thinking long-term. Having political prisoners, living in a state of antagonism with a government that is supposed to serve you — in the case of Catalonia, the Spanish government — creates a kind of suspension, an unreal quality. It is not unlike living in Trump’s America. It will take a while to have the distance to understand this moment.

How would you describe the attitude American publishers have toward Catalan literature?

Truth be told, publishers are receptive to Catalan literature. They know it is of great quality, they are even more interested now that Catalonia is a trending topic, and they know there is funding, which is an extraordinary help, especially for small publishers. Some publishers have made a real commitment to Catalan literature — Open Letter, Archipelago, Dalkey Archive, for example — and I know others are looking for the next great thing.

What could we be doing better to support Catalan literature and culture?

I think there is a problem with the haphazardness of translations, in what gets translated when, and who connects the dots for the readers.

For example, there is a considerable body of 20th-century Catalan works available now, but as there isn’t an apparatus to relate one book to another, the corpus is invisible. New books appear in isolation, and reviewers, even publishers, often don’t have the information to establish links among the Catalan books or, even more distressingly, between the Catalan books and comparable texts from other literary traditions.

What can we do? Perhaps consider writing articles that would connect those dots and define the canon. By the way, I don’t think this problem is limited to Catalan literature: any less familiar literary tradition faces a similar challenge.

Is there a Catalan writer whose works you would like to translate but don’t because of a perceived lack of interest from publishers?

There are numerous writers whose work I would like to translate. I have a certain confidence, which I hope is not misplaced, that if I presented a project, particularly with the financial backing of the Institut Ramon Llull — which underlies a great deal of the success in bringing Catalan literature to English — it would find a good home. The problem is less with the publishers than with the time I dispose of.

What is your process when conducting a translation?

It really depends on the book, but I tend to do a quick and dirty first draft, making lots of notes and setting down options, and writing queries, and then going back and editing it to death. Four or five readings, and constant revision. It is a luxurious method, in the sense of the luxury of time; as you know, my translations are few and far between.

Do you think of literary translations as a form of self-translation? Do you think of it as a journey? How does translation change or influence your relationship to time and space?

I don’t, really. It is an extraordinary creative process, and I think I have referred to the psychoanalytic quality, the reflective quality, but it also has an artisanal aspect that keeps it real.

It is definitely a form of writing, and a creative vehicle, but it is not like writing from scratch, and there is always the source text between you and yourself.

Who are some of your favorite Catalan authors, and why?

Mercè Rodoreda, beyond any doubt. One of the great 20th-century world writers.

Like Sagarra and Monzó, she is merciless in her portrayals, and yet you also see, with empathy (yours, not hers), how her characters are buffeted by their circumstances and by the trends of history. I love her combination of real, surreal, and hyperreal. J. V. Foix, the poet, is the epitome of surrealism anchored in everyday reality, on a parallel in poetry with Joan Miró and Salvador Dalí in the visual. I love Ausiàs March, the Valencian Renaissance poet, and Tirant lo Blanc, by Joanot Martorell, still gorgeous and eminently readable in David Rosenthal’s translation. And Joan Maragall, the marvelous turn-of-the-century poet who could be a historian, a romantic, or a mystic, by turns.

And, oh my God, do I love Eugeni d’Ors, the “household philosopher” who educated a whole generation of readers (1906–1920-ish) from his daily newspaper column. Joan Fuster, the Valencian essayist, is a dazzling skeptic. I recently learned about Cèlia Suñol i Pla, an elegant midcentury novelist who had been lost and is being relaunched. I would love to translate her. And Marta Rojals, a brilliant chronicler of Generation X. And, finally, in the most chaotic order (I am not following my mandate of making the canon visible), I love love love Francesc Trabal. I encourage people to read his novel, Waltz, translated by Martha Tennent. Oh, wait, and Pere Calders, a mordant and deadpan short story writer (Mara Faye Lethem is working on him, and I look forward to that!). I have to stop.

What are your duties as the chair of the Pen American Translation Committee?

The PEN America Translation Committee advocates for translators within the scope of PEN, in every way PEN advocates for writers. We are concerned with every aspect of translators as writers: their legal and financial status — we are working on establishing contract guidelines with both the Authors’ Guild and a pro bono legal team, their status in publishing and in the hierarchy of writing. We bring to the fore the fact that literary and cultural transmission depends to a great extent on translators and translations, and we press for this to be recognized both in prestige and, concomitantly, in remuneration.

Are you currently working on a translation?

I am recreationally translating Oceanography of Tedium by Eugeni d’Ors. Since it is a little allegorical jewel, whose structure is dictated by its origin as daily newspaper articles, I can go about it in between other things. I haven’t tried to sell it or place it; I’m just doing it for the pleasure of it.

¤

Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi is the author of Call Me Zebra.

The post The Catalan Paradox, Part II: Conversation with Translator Mary Ann Newman appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books https://ift.tt/2CJVdNw

0 notes

Link

MARY ANN NEWMAN STILL LIVES in the same apartment she was born and raised in. That apartment happens to be in Chelsea in New York City, and it also happens to be part of the reason she fell in love with Catalan and Spanish literature.

The neighborhood she grew up in wasn’t the glamorous, prohibitive destination it has become, but rather a working-class neighborhood where she heard and saw Spanish on the streets as often as English. She later became enamored of Spanish literature and went on to discover Catalan culture and history. She has since devoted her life to being an ambassador of Catalan literature and has been justly rewarded for it. A celebrated translator, editor, and cultural critic, she is the director of the Farragut Fund for Catalan Culture in the US.

I first encountered Mary Ann Newman’s work when I read her translation of Quim Monzó’s novel Gasoline (Monzó is the previous interlocutor in this series of conversations on Catalan literature). My husband, Leonardo Francalanci, a Catalan scholar, had just taught her translation of Josep Maria de Sagarra’s Private Life, an epic chronicle of life in Barcelona before the Spanish Civil War. She has also translated a short story collection by Quim Monzó, essays by Xavier Rubert de Ventós, and a collection of poems by Josep Carner. In this interview, we talk about translation as an embodied practice, her journey from New York City to Barcelona, the contemporary Catalan crisis, and the evolution of her love affair with Catalan literature over the years.

¤

AZAREEN VAN DER VLIET OLOOMI: When did you first travel to Catalonia and become aware of it as a region with a cultural identity that is distinct from the rest of Spain?

MARY ANN NEWMAN: I went to Spain in 1972, at 20, for a junior semester abroad. I knew there was such a thing as Catalonia, and Galicia, and the Basque Country. There had been Galician children in my grammar school in New York in the ’50s. West 14th Street was still known then as Little Spain, and I lived on West 16th Street. One day in high school, as other students were being drilled in conjugations, I started leafing through the Spanish culture text we never cracked, and read that there were four languages in Spain — Spanish, Catalan, Basque, and Galician. I remember perfectly the hand-drawn map of the Iberian Peninsula with the regions outlined.

These little bits of information — the Galician classmates, the map — are like iron filings: when you finally encounter the magnet of the culture, they jump into shape and become meaningful. They allow you to be attentive to difference.

During my semester in Madrid, I took a train to Barcelona. It was love at first sight, with the landscape, with the architecture, with the quality of the light and the sky. And with the sound of the language. I felt the difference right away. It was easy to make the leap from there to the distinct cultural identity.

I tend to think of acquiring a second or third language as entering into a love affair: the process is enigmatic, visceral, and powerful enough to shift our sense of identity. Can you describe your love affair with Catalan? When did you start learning Catalan, and why? How is it different from your relationship to Spanish?

I think it’s contiguous with my relationship to Spanish. One’s reaction to cultures, cities, landscapes, and languages is, or can be, as intense and visceral as it is to people and lovers.

My love affair began with Spanish. I love the Spanish language, its immense variety, all the cultures that fall under the rubric of “Hispanic,” even the conflicted history of its relationship with the languages it has suppressed. I grew up in a very bilingual environment — at the grammar school I mentioned before, St. Francis Xavier, a large proportion of the children were of Latino origin, mostly Puerto Rican. My neighborhood was full of stores with “Spanish” products — “Spanish” covered everything in those days. My first childhood encounter with a foreign country was Cuba, where I learned my first words in Spanish, tasted my first rice and beans, and absorbed some sort of deep-seated familiarity, a sort of subcutaneous recognition, with Hispanic culture. Later, as an adult, Spanish allowed me to take a distance from monolingual American culture, to see the United States from another, often disapproving or denunciatory perspective. I moved from this general love of Hispanic culture to the specific enchantment with Catalan culture, which, in turn, gave me perspective on Spanish. They are not entirely at odds. For most Americans, Spanish (in the broad sense my neighborhood applied) is the gateway to Catalan.

This was very organic and informal. I started learning Catalan in 1976, in Madrid. I was completely smitten with the culture. I had developed wonderful Catalan friendships in New York, with people who loved to talk about their hometowns (Barcelona, but also Valls, Tarragona…). I attended two classes in Madrid, the only two classes I ever took, at the Círculo Catalán. My classmates were all young madrileños, political progressives who loved Lluís Llach or Raimon, who expressed their solidarity with the Catalan people by learning the language.

In 1977, I moved to Barcelona and started speaking Catalan with everyone who would put up with me. Back in New York, in 1978, I bought Alan Yates’s Teach Yourself Catalan — I still highly recommend it — and did just that. I got a group of friends together, I would study up a chapter and teach it to them. It worked. I learned the grammar. But the passion for the language was already deep, and everything I had learned by living in Catalonia only reinforced it: the markets, the architecture, the politics — 1977 was the year of legalizations, the year of the Anarchist Days, the first LGBT demonstration, the first mega-demonstration in favor of the Statute of Autonomy and the release of Catalan political prisoners. It was the perfect year for a young American progressive to be initiated into Catalonia. Above all, I started reading: Salvador Espriu, Mercè Rodoreda, Biel Mesquida. If you know another Romance language well, you can read before you can talk, and when you start talking, all that reading — the words, the sentence structures — is at your disposal.

What was the first book you read in translation? And the first book you translated?

It was probably Grimm’s Fairy Tales. I loved them and read them over and over. I remember loving Babar the Elephant. My first grown-up reading was an immense collection of stories by Guy de Maupassant. Of course, this is all in retrospect. I had no idea I was reading translations — they were just books I loved. In high school, I discovered The Stranger and The Trial (which I loved) and Steppenwolf (which I hated), and all the books that thrill an inquiring teenager. And in freshman year of college, One Hundred Years of Solitude (I borrowed it from a lending library in a tobacconist on 8th Street for 25 cents) was what convinced me to major in Latin American literature. It was a lightning bolt.

The first book I translated was O’Clock, by Quim Monzó.

What do you think the art of translation has in common with the art of listening? Do you consider the process of conducting a translation to be an embodied experience?

It is for me. But so is reading itself. And translation is the most radical form of reading, the most deep-rooted.

When you read, you can sort of slide by things that are opaque. When you translate, you can’t slip by, you have to dig down to understand them, and it involves all the senses: What is this character seeing, smelling, feeling (both touch and emotion), hearing? What were people wearing?

This is the empiricism of translation: it entails a trial and error, a continuous editing and rereading. All of which is very physical; it cycles back and forth between rationality and instinct. Many language devices are unconscious or even pre-conscious; unremembered things, words, concepts rise to the surface when they are called up by the translation. It has a psychoanalytic quality.

How does your relationship to the translation change depending on whether you are working with a living or dead author?

I think it doesn’t. My relationship is with the text, and with the author insofar as he or she inhabits the text. It’s wonderful to be able to consult with the author, and my two living authors, Quim Monzó and Xavier Rubert de Ventós, were always very helpful, but in the end, it’s my job, and my book. You can only hope the author approves.

How did you happen to start translating Quim Monzó?

I was living in Barcelona in 1980 on a Fulbright, and reading everything I could. Quim’s books were breaking all the molds in Catalan literature, and in world literature. I met Monzó there, but, even more fortunately, it turned out that he was going to spend the following year in New York. In New York, I proposed a translation, he agreed, I put together a dossier with three stories, bio, et cetera, sent them to an agent, who loved them, who sent them to a publisher, who loved them … It was deceptively simple.

What is the most enjoyable part of translating Monzó, and what is the most challenging?

As often happens, the most enjoyable and the most challenging come together. Quim’s writing is very approachable, very readable, so the quality of his art can be imperceptible. Through translation, it becomes evident. His writing is spare and dense. His sentences are reduced to the absolute minimum, but packed with meaning. There is no extraneous matter. To render this in English should seem like a no-brainer, but English is dense and spare in a different way from Catalan, and they don’t always overlap. It’s a challenge, but it’s also great fun to crack the code.

How was translating Josep Maria de Sagarra’s Private Life different from your other translations? Did you have to do historical research?

It’s useful to compare it to Monzó. Sagarra is the grand pre–Civil War chronicler of Barcelona. He set out intentionally to write the great Catalan novel, to hold Stendhal’s mirror up to the life of the city. And he wrote this broad, florid, marvelous tapestry, with billowing sentences and a plethora of adjectives and adverbs. It was a blast to translate.

I had some knowledge of the period, so the research was more of a deep dig: sometimes it seemed as if he were using a photograph to evoke a scene, and in a number of cases I actually found the photograph in question. There were a few mystifying passages and references that I was able to track down and, in one case, flesh out — a bit of creative editing that might be considered controversial. It was interesting: after my first draft, I read the Spanish translation. I was sure it would resolve my doubts. But the apparent closeness of Spanish to Catalan allowed Manuel Vázquez Montalbán and José Agustín Goytisolo to translate obscure passages literally, which I couldn’t do in English. Still, the detective work was a lot of fun. So, the interesting thing about going from Monzó to Sagarra, is that Sagarra is splendidly sweeping and baroque, and Monzó is perfectly minimalist and spare, but they share a sensibility, a willingness not to prettify the subjects they portray. It feels like a Catalan sensibility, certainly a Barcelonan sensibility.

How has your work as a cultural administrator and translator changed since the Catalan referendum?

It hasn’t affected me, professionally, but it has affected the people I deal with.

Personally, and professionally, it is distressing to perceive the normalization of a kind of pessimism. Life goes on, everyone does his job, Catalonia prospers, but there is a cloud hanging over people’s heads, and a subtle brake on thinking long-term. Having political prisoners, living in a state of antagonism with a government that is supposed to serve you — in the case of Catalonia, the Spanish government — creates a kind of suspension, an unreal quality. It is not unlike living in Trump’s America. It will take a while to have the distance to understand this moment.

How would you describe the attitude American publishers have toward Catalan literature?

Truth be told, publishers are receptive to Catalan literature. They know it is of great quality, they are even more interested now that Catalonia is a trending topic, and they know there is funding, which is an extraordinary help, especially for small publishers. Some publishers have made a real commitment to Catalan literature — Open Letter, Archipelago, Dalkey Archive, for example — and I know others are looking for the next great thing.

What could we be doing better to support Catalan literature and culture?

I think there is a problem with the haphazardness of translations, in what gets translated when, and who connects the dots for the readers.

For example, there is a considerable body of 20th-century Catalan works available now, but as there isn’t an apparatus to relate one book to another, the corpus is invisible. New books appear in isolation, and reviewers, even publishers, often don’t have the information to establish links among the Catalan books or, even more distressingly, between the Catalan books and comparable texts from other literary traditions.

What can we do? Perhaps consider writing articles that would connect those dots and define the canon. By the way, I don’t think this problem is limited to Catalan literature: any less familiar literary tradition faces a similar challenge.

Is there a Catalan writer whose works you would like to translate but don’t because of a perceived lack of interest from publishers?

There are numerous writers whose work I would like to translate. I have a certain confidence, which I hope is not misplaced, that if I presented a project, particularly with the financial backing of the Institut Ramon Llull — which underlies a great deal of the success in bringing Catalan literature to English — it would find a good home. The problem is less with the publishers than with the time I dispose of.

What is your process when conducting a translation?

It really depends on the book, but I tend to do a quick and dirty first draft, making lots of notes and setting down options, and writing queries, and then going back and editing it to death. Four or five readings, and constant revision. It is a luxurious method, in the sense of the luxury of time; as you know, my translations are few and far between.

Do you think of literary translations as a form of self-translation? Do you think of it as a journey? How does translation change or influence your relationship to time and space?

I don’t, really. It is an extraordinary creative process, and I think I have referred to the psychoanalytic quality, the reflective quality, but it also has an artisanal aspect that keeps it real.

It is definitely a form of writing, and a creative vehicle, but it is not like writing from scratch, and there is always the source text between you and yourself.

Who are some of your favorite Catalan authors, and why?

Mercè Rodoreda, beyond any doubt. One of the great 20th-century world writers.

Like Sagarra and Monzó, she is merciless in her portrayals, and yet you also see, with empathy (yours, not hers), how her characters are buffeted by their circumstances and by the trends of history. I love her combination of real, surreal, and hyperreal. J. V. Foix, the poet, is the epitome of surrealism anchored in everyday reality, on a parallel in poetry with Joan Miró and Salvador Dalí in the visual. I love Ausiàs March, the Valencian Renaissance poet, and Tirant lo Blanc, by Joanot Martorell, still gorgeous and eminently readable in David Rosenthal’s translation. And Joan Maragall, the marvelous turn-of-the-century poet who could be a historian, a romantic, or a mystic, by turns.

And, oh my God, do I love Eugeni d’Ors, the “household philosopher” who educated a whole generation of readers (1906–1920-ish) from his daily newspaper column. Joan Fuster, the Valencian essayist, is a dazzling skeptic. I recently learned about Cèlia Suñol i Pla, an elegant midcentury novelist who had been lost and is being relaunched. I would love to translate her. And Marta Rojals, a brilliant chronicler of Generation X. And, finally, in the most chaotic order (I am not following my mandate of making the canon visible), I love love love Francesc Trabal. I encourage people to read his novel, Waltz, translated by Martha Tennent. Oh, wait, and Pere Calders, a mordant and deadpan short story writer (Mara Faye Lethem is working on him, and I look forward to that!). I have to stop.

What are your duties as the chair of the Pen American Translation Committee?

The PEN America Translation Committee advocates for translators within the scope of PEN, in every way PEN advocates for writers. We are concerned with every aspect of translators as writers: their legal and financial status — we are working on establishing contract guidelines with both the Authors’ Guild and a pro bono legal team, their status in publishing and in the hierarchy of writing. We bring to the fore the fact that literary and cultural transmission depends to a great extent on translators and translations, and we press for this to be recognized both in prestige and, concomitantly, in remuneration.

Are you currently working on a translation?

I am recreationally translating Oceanography of Tedium by Eugeni d’Ors. Since it is a little allegorical jewel, whose structure is dictated by its origin as daily newspaper articles, I can go about it in between other things. I haven’t tried to sell it or place it; I’m just doing it for the pleasure of it.

¤

Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi is the author of Call Me Zebra.

The post The Catalan Paradox, Part II: Conversation with Translator Mary Ann Newman appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books https://ift.tt/2CJVdNw via IFTTT

0 notes

Link

MARY ANN NEWMAN STILL LIVES in the same apartment she was born and raised in. That apartment happens to be in Chelsea in New York City, and it also happens to be part of the reason she fell in love with Catalan and Spanish literature.

The neighborhood she grew up in wasn’t the glamorous, prohibitive destination it has become, but rather a working-class neighborhood where she heard and saw Spanish on the streets as often as English. She later became enamored of Spanish literature and went on to discover Catalan culture and history. She has since devoted her life to being an ambassador of Catalan literature and has been justly rewarded for it. A celebrated translator, editor, and cultural critic, she is the director of the Farragut Fund for Catalan Culture in the US.

I first encountered Mary Ann Newman’s work when I read her translation of Quim Monzó’s novel Gasoline (Monzó is the previous interlocutor in this series of conversations on Catalan literature). My husband, Leonardo Francalanci, a Catalan scholar, had just taught her translation of Josep Maria de Sagarra’s Private Life, an epic chronicle of life in Barcelona before the Spanish Civil War. She has also translated a short story collection by Quim Monzó, essays by Xavier Rubert de Ventós, and a collection of poems by Josep Carner. In this interview, we talk about translation as an embodied practice, her journey from New York City to Barcelona, the contemporary Catalan crisis, and the evolution of her love affair with Catalan literature over the years.

¤

AZAREEN VAN DER VLIET OLOOMI: When did you first travel to Catalonia and become aware of it as a region with a cultural identity that is distinct from the rest of Spain?

MARY ANN NEWMAN: I went to Spain in 1972, at 20, for a junior semester abroad. I knew there was such a thing as Catalonia, and Galicia, and the Basque Country. There had been Galician children in my grammar school in New York in the ’50s. West 14th Street was still known then as Little Spain, and I lived on West 16th Street. One day in high school, as other students were being drilled in conjugations, I started leafing through the Spanish culture text we never cracked, and read that there were four languages in Spain — Spanish, Catalan, Basque, and Galician. I remember perfectly the hand-drawn map of the Iberian Peninsula with the regions outlined.

These little bits of information — the Galician classmates, the map — are like iron filings: when you finally encounter the magnet of the culture, they jump into shape and become meaningful. They allow you to be attentive to difference.

During my semester in Madrid, I took a train to Barcelona. It was love at first sight, with the landscape, with the architecture, with the quality of the light and the sky. And with the sound of the language. I felt the difference right away. It was easy to make the leap from there to the distinct cultural identity.

I tend to think of acquiring a second or third language as entering into a love affair: the process is enigmatic, visceral, and powerful enough to shift our sense of identity. Can you describe your love affair with Catalan? When did you start learning Catalan, and why? How is it different from your relationship to Spanish?

I think it’s contiguous with my relationship to Spanish. One’s reaction to cultures, cities, landscapes, and languages is, or can be, as intense and visceral as it is to people and lovers.

My love affair began with Spanish. I love the Spanish language, its immense variety, all the cultures that fall under the rubric of “Hispanic,” even the conflicted history of its relationship with the languages it has suppressed. I grew up in a very bilingual environment — at the grammar school I mentioned before, St. Francis Xavier, a large proportion of the children were of Latino origin, mostly Puerto Rican. My neighborhood was full of stores with “Spanish” products — “Spanish” covered everything in those days. My first childhood encounter with a foreign country was Cuba, where I learned my first words in Spanish, tasted my first rice and beans, and absorbed some sort of deep-seated familiarity, a sort of subcutaneous recognition, with Hispanic culture. Later, as an adult, Spanish allowed me to take a distance from monolingual American culture, to see the United States from another, often disapproving or denunciatory perspective. I moved from this general love of Hispanic culture to the specific enchantment with Catalan culture, which, in turn, gave me perspective on Spanish. They are not entirely at odds. For most Americans, Spanish (in the broad sense my neighborhood applied) is the gateway to Catalan.

This was very organic and informal. I started learning Catalan in 1976, in Madrid. I was completely smitten with the culture. I had developed wonderful Catalan friendships in New York, with people who loved to talk about their hometowns (Barcelona, but also Valls, Tarragona…). I attended two classes in Madrid, the only two classes I ever took, at the Círculo Catalán. My classmates were all young madrileños, political progressives who loved Lluís Llach or Raimon, who expressed their solidarity with the Catalan people by learning the language.

In 1977, I moved to Barcelona and started speaking Catalan with everyone who would put up with me. Back in New York, in 1978, I bought Alan Yates’s Teach Yourself Catalan — I still highly recommend it — and did just that. I got a group of friends together, I would study up a chapter and teach it to them. It worked. I learned the grammar. But the passion for the language was already deep, and everything I had learned by living in Catalonia only reinforced it: the markets, the architecture, the politics — 1977 was the year of legalizations, the year of the Anarchist Days, the first LGBT demonstration, the first mega-demonstration in favor of the Statute of Autonomy and the release of Catalan political prisoners. It was the perfect year for a young American progressive to be initiated into Catalonia. Above all, I started reading: Salvador Espriu, Mercè Rodoreda, Biel Mesquida. If you know another Romance language well, you can read before you can talk, and when you start talking, all that reading — the words, the sentence structures — is at your disposal.

What was the first book you read in translation? And the first book you translated?

It was probably Grimm’s Fairy Tales. I loved them and read them over and over. I remember loving Babar the Elephant. My first grown-up reading was an immense collection of stories by Guy de Maupassant. Of course, this is all in retrospect. I had no idea I was reading translations — they were just books I loved. In high school, I discovered The Stranger and The Trial (which I loved) and Steppenwolf (which I hated), and all the books that thrill an inquiring teenager. And in freshman year of college, One Hundred Years of Solitude (I borrowed it from a lending library in a tobacconist on 8th Street for 25 cents) was what convinced me to major in Latin American literature. It was a lightning bolt.

The first book I translated was O’Clock, by Quim Monzó.

What do you think the art of translation has in common with the art of listening? Do you consider the process of conducting a translation to be an embodied experience?

It is for me. But so is reading itself. And translation is the most radical form of reading, the most deep-rooted.

When you read, you can sort of slide by things that are opaque. When you translate, you can’t slip by, you have to dig down to understand them, and it involves all the senses: What is this character seeing, smelling, feeling (both touch and emotion), hearing? What were people wearing?

This is the empiricism of translation: it entails a trial and error, a continuous editing and rereading. All of which is very physical; it cycles back and forth between rationality and instinct. Many language devices are unconscious or even pre-conscious; unremembered things, words, concepts rise to the surface when they are called up by the translation. It has a psychoanalytic quality.

How does your relationship to the translation change depending on whether you are working with a living or dead author?

I think it doesn’t. My relationship is with the text, and with the author insofar as he or she inhabits the text. It’s wonderful to be able to consult with the author, and my two living authors, Quim Monzó and Xavier Rubert de Ventós, were always very helpful, but in the end, it’s my job, and my book. You can only hope the author approves.

How did you happen to start translating Quim Monzó?

I was living in Barcelona in 1980 on a Fulbright, and reading everything I could. Quim’s books were breaking all the molds in Catalan literature, and in world literature. I met Monzó there, but, even more fortunately, it turned out that he was going to spend the following year in New York. In New York, I proposed a translation, he agreed, I put together a dossier with three stories, bio, et cetera, sent them to an agent, who loved them, who sent them to a publisher, who loved them … It was deceptively simple.

What is the most enjoyable part of translating Monzó, and what is the most challenging?

As often happens, the most enjoyable and the most challenging come together. Quim’s writing is very approachable, very readable, so the quality of his art can be imperceptible. Through translation, it becomes evident. His writing is spare and dense. His sentences are reduced to the absolute minimum, but packed with meaning. There is no extraneous matter. To render this in English should seem like a no-brainer, but English is dense and spare in a different way from Catalan, and they don’t always overlap. It’s a challenge, but it’s also great fun to crack the code.

How was translating Josep Maria de Sagarra’s Private Life different from your other translations? Did you have to do historical research?

It’s useful to compare it to Monzó. Sagarra is the grand pre–Civil War chronicler of Barcelona. He set out intentionally to write the great Catalan novel, to hold Stendhal’s mirror up to the life of the city. And he wrote this broad, florid, marvelous tapestry, with billowing sentences and a plethora of adjectives and adverbs. It was a blast to translate.

I had some knowledge of the period, so the research was more of a deep dig: sometimes it seemed as if he were using a photograph to evoke a scene, and in a number of cases I actually found the photograph in question. There were a few mystifying passages and references that I was able to track down and, in one case, flesh out — a bit of creative editing that might be considered controversial. It was interesting: after my first draft, I read the Spanish translation. I was sure it would resolve my doubts. But the apparent closeness of Spanish to Catalan allowed Manuel Vázquez Montalbán and José Agustín Goytisolo to translate obscure passages literally, which I couldn’t do in English. Still, the detective work was a lot of fun. So, the interesting thing about going from Monzó to Sagarra, is that Sagarra is splendidly sweeping and baroque, and Monzó is perfectly minimalist and spare, but they share a sensibility, a willingness not to prettify the subjects they portray. It feels like a Catalan sensibility, certainly a Barcelonan sensibility.

How has your work as a cultural administrator and translator changed since the Catalan referendum?

It hasn’t affected me, professionally, but it has affected the people I deal with.

Personally, and professionally, it is distressing to perceive the normalization of a kind of pessimism. Life goes on, everyone does his job, Catalonia prospers, but there is a cloud hanging over people’s heads, and a subtle brake on thinking long-term. Having political prisoners, living in a state of antagonism with a government that is supposed to serve you — in the case of Catalonia, the Spanish government — creates a kind of suspension, an unreal quality. It is not unlike living in Trump’s America. It will take a while to have the distance to understand this moment.

How would you describe the attitude American publishers have toward Catalan literature?

Truth be told, publishers are receptive to Catalan literature. They know it is of great quality, they are even more interested now that Catalonia is a trending topic, and they know there is funding, which is an extraordinary help, especially for small publishers. Some publishers have made a real commitment to Catalan literature — Open Letter, Archipelago, Dalkey Archive, for example — and I know others are looking for the next great thing.

What could we be doing better to support Catalan literature and culture?

I think there is a problem with the haphazardness of translations, in what gets translated when, and who connects the dots for the readers.

For example, there is a considerable body of 20th-century Catalan works available now, but as there isn’t an apparatus to relate one book to another, the corpus is invisible. New books appear in isolation, and reviewers, even publishers, often don’t have the information to establish links among the Catalan books or, even more distressingly, between the Catalan books and comparable texts from other literary traditions.

What can we do? Perhaps consider writing articles that would connect those dots and define the canon. By the way, I don’t think this problem is limited to Catalan literature: any less familiar literary tradition faces a similar challenge.

Is there a Catalan writer whose works you would like to translate but don’t because of a perceived lack of interest from publishers?

There are numerous writers whose work I would like to translate. I have a certain confidence, which I hope is not misplaced, that if I presented a project, particularly with the financial backing of the Institut Ramon Llull — which underlies a great deal of the success in bringing Catalan literature to English — it would find a good home. The problem is less with the publishers than with the time I dispose of.

What is your process when conducting a translation?

It really depends on the book, but I tend to do a quick and dirty first draft, making lots of notes and setting down options, and writing queries, and then going back and editing it to death. Four or five readings, and constant revision. It is a luxurious method, in the sense of the luxury of time; as you know, my translations are few and far between.

Do you think of literary translations as a form of self-translation? Do you think of it as a journey? How does translation change or influence your relationship to time and space?

I don’t, really. It is an extraordinary creative process, and I think I have referred to the psychoanalytic quality, the reflective quality, but it also has an artisanal aspect that keeps it real.

It is definitely a form of writing, and a creative vehicle, but it is not like writing from scratch, and there is always the source text between you and yourself.

Who are some of your favorite Catalan authors, and why?

Mercè Rodoreda, beyond any doubt. One of the great 20th-century world writers.

Like Sagarra and Monzó, she is merciless in her portrayals, and yet you also see, with empathy (yours, not hers), how her characters are buffeted by their circumstances and by the trends of history. I love her combination of real, surreal, and hyperreal. J. V. Foix, the poet, is the epitome of surrealism anchored in everyday reality, on a parallel in poetry with Joan Miró and Salvador Dalí in the visual. I love Ausiàs March, the Valencian Renaissance poet, and Tirant lo Blanc, by Joanot Martorell, still gorgeous and eminently readable in David Rosenthal’s translation. And Joan Maragall, the marvelous turn-of-the-century poet who could be a historian, a romantic, or a mystic, by turns.

And, oh my God, do I love Eugeni d’Ors, the “household philosopher” who educated a whole generation of readers (1906–1920-ish) from his daily newspaper column. Joan Fuster, the Valencian essayist, is a dazzling skeptic. I recently learned about Cèlia Suñol i Pla, an elegant midcentury novelist who had been lost and is being relaunched. I would love to translate her. And Marta Rojals, a brilliant chronicler of Generation X. And, finally, in the most chaotic order (I am not following my mandate of making the canon visible), I love love love Francesc Trabal. I encourage people to read his novel, Waltz, translated by Martha Tennent. Oh, wait, and Pere Calders, a mordant and deadpan short story writer (Mara Faye Lethem is working on him, and I look forward to that!). I have to stop.

What are your duties as the chair of the Pen American Translation Committee?

The PEN America Translation Committee advocates for translators within the scope of PEN, in every way PEN advocates for writers. We are concerned with every aspect of translators as writers: their legal and financial status — we are working on establishing contract guidelines with both the Authors’ Guild and a pro bono legal team, their status in publishing and in the hierarchy of writing. We bring to the fore the fact that literary and cultural transmission depends to a great extent on translators and translations, and we press for this to be recognized both in prestige and, concomitantly, in remuneration.

Are you currently working on a translation?

I am recreationally translating Oceanography of Tedium by Eugeni d’Ors. Since it is a little allegorical jewel, whose structure is dictated by its origin as daily newspaper articles, I can go about it in between other things. I haven’t tried to sell it or place it; I’m just doing it for the pleasure of it.

¤

Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi is the author of Call Me Zebra.

The post The Catalan Paradox, Part II: Conversation with Translator Mary Ann Newman appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books https://ift.tt/2CJVdNw

0 notes

Text

what makes Barcelona vs. Chelsea so special

Visit Now - http://zeroviral.com/what-makes-barcelona-vs-chelsea-so-special/

what makes Barcelona vs. Chelsea so special

Barcelona vs. Chelsea isn’t a “European Clasico” simply because every time they meet, the pitch is decorated with some of Europe’s most sumptuous talents. For a fixture to truly sizzle and fizz in the days and weeks before it is played, there needs to be some degree of a revenge or bad-blood narrative, a rivalry that turns an infrequent continental match-up into the kind of “must win at any cost” derby like Milan vs. Inter, Rangers vs. Celtic, Manchester United vs. Liverpool or Madrid vs. Atletico.

This one has all that and more, a fact that can be traced back to an overnight flight back from Moscow to London in early November 2004.

Jose Mourinho’s “Blue Machine” had just guaranteed qualification for the knockout round after only four months of his reign and four straight Group H wins. This was when the Special One truly was special. He had back-to-back European trophies with Porto while Chelsea had tripped up, inexplicably, on the verge of the Champions League final the previous season.

Jaunty Jose had the Midas touch, in word and deed. Earlier that night, Damien Duff had set up Arjen Robben for the 1-0 win over CSKA Moscow that guaranteed Roman Abramovich’s new European force would reach the last sixteen. Duff, a huge admirer of the modern Barca school, takes up the tale.

“Right from the first moment, Mourinho wanted the draw to pair us with Barca,” recalls the brilliant Irish winger. “We were flying back from winning in Moscow and the lads were all just having a bit of fun with Jose.

“We knew we were going to top our group so we were saying: ‘Who do you want in the next round boss?’ He immediately goes: ‘Barcelona!’ Our instant response was: ‘Are you for real?’ But Jose just told us: ‘It’s simple: We stop them playing and they let us play.’ Simple as that as far as he saw it.”

Mourinho knew two things. Barcelona, although on the rise, were still the wobbly-legged Bambi of European football. Reborn, but shaky on their feet having not won any trophies for five years and no UEFA title since 1992. They were ripe for a football predator to rip into them.

Secondly, Mourinho knew that in 2004, there was still an ideological war being fought within the Camp Nou. Nominally, Joan Laporta, fueled by his ultra-Cruyffist beliefs, was in charge. But the president had enemies within his board, most notably vice president Sandro Rosell and current president Josep Maria Bartomeu. Those latter two, among others, wanted Barcelona to be pragmatic, mirroring Chelsea by signing big, strong, athletic footballers and to dump Frank Rijkaard so that (future Chelsea coach) Luiz Felipe Scolari could take over.

Mourinho viewed Rijkaard’s Barca, where the Ronaldinho-Samuel Eto’o partnership was young but promising and Andres Iniesta had recently been the subject of a hugely fierce debate about whether he should be played or loaned out, as not quite ready to repel his brand of footballing fire and fury.

Sean Dempsey – PA Images/PA Images via Getty Images

Essentially, Mourinho was correct. The desire that this quixotic, remarkable, talented and ruthless man has had to inherit the good life as Barcelona coach stemmed from the coaching duties he undertook as understudy to both Sir Bobby Robson and Louis Van Gaal in the late 1990s. And it was evidenced most starkly in the “clasico wars” of 2010-11 when he was Madrid coach in opposition to Pep Guardiola’s Barcelona.

But the first time Mourinho caught a whiff of him being able to power his way past a “Cruyffist” Barca and potentially leave himself as the top candidate when the job became vacant was when this rivalry took bitter root back in Spring, 2005.

What followed over the next four matches was a flow of simply extraordinary events, landmark in fact, which set the tone for years of battles between the new, emerging Barca philosophy and the modern Premier League ideal which blended traditional English football beliefs with many of the best imported coaches, players and ideas. A battle that will rage again this week.

Back in 2004 the tone, belligerent and streetwise, was set immediately. Before the match, one Catalan journalist goaded Mourinho about his past as “merely a translator” at the Camp Nou under Sir Bobby Robson and he “bit his head off,” nailing what was, quite clearly, a false reputation. Then Mourinho offered to finish the press conference in remarkable style: by naming all 22 players who’d take the field the next night.

First he (correctly) listed the Barca XI before carrying on, “giving away” his Chelsea starting lineup. The move was aimed at taking charge of the pre-match psychology, to tell Barcelona’s staff and players “you have nothing I’ve not anticipated: I’m the boss.”

It was fun at the time but better still in the knowledge that he actually fooled his own players.

“I remember Mourinho telling me I was definitely starting but then he played a few ‘mind games’ with the press,” said Duff. “He’d taken me aside and said: ‘You are in the team tomorrow but I’m going to give them a different lineup in the press conference. I think he announced Eidur Gudjohnsen was playing instead of me.

“When I saw him name the team on TV, I started believing it and had to wait 24 anxious hours to discover that, lo and behold, I was in it.”