#i feel like such a child and simultaneously such an inhuman grotesque thing

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

.

#i hate hate hate the feeling of being around my family right now#hate feeling like so much of me is something they just cant understand (#and i feel like im just hiding deeper and deeper inside myself#i can feel how disappointed they are when i dont look/think like they expected#i feel like such a child and simultaneously such an inhuman grotesque thing#just need to get out of town.... but where to go? it's all the same.#trying to write these applications when i dont know myself or what i want and everyone around me doesnt understand me at all#and my brother is coming tomorrow or the next day and i know. i just know hes going to be so sharp and cruel and i just cant take it rn#he doesnt even have to say anything#he can just look at me the right way and totally break all the things i sort of like about myself#fucks sake. whatever#caught in a whirlwind as always

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

30 Day Monster Challenge 2 - Day #14: Favorite Invisible Monster

Some of the monsters on this list are so good at being invisible that I couldn’t even find a good picture of them.

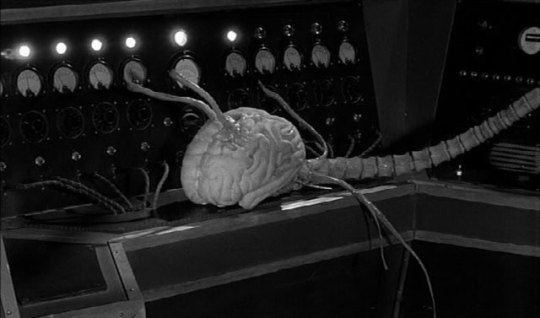

1. Killer Brain (Fiend Without A Face)

The charm of any invisible monster is proportionate to how bizarre it is when it is inevitably revealed, and there are few monster that can compete with the killer brains from Fiend Without a Face. Even their explanation is unique; killer telekinetic thoughts that possess human brains and feed off nuclear radiation. These things are simultaneously adorable and grotesque; they’re slimy and have the eye tendrils of a slug, and even the way they move is creepy. They use their spinal cord tails to move around and strangle people, making more of their kind. These guys made it into Pathfinder where, frankly, I wish they had replaced Intellect Devourers in terms of being the game’s designated brain monsters (since the Mind Flayer is copyrighted). The killer brains just nail that perfect kind of creeping horror where I don’t want to touch one but I also kind of want to keep it in a tank as a pet. They do not disappoint once you finally get a look at them.

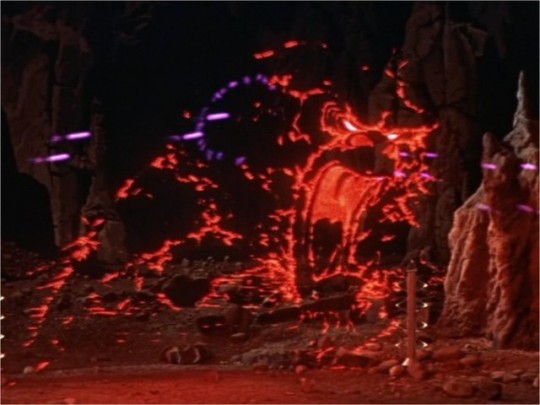

2. Monsters from the Id (Forbidden Planet)

The artist Francisco de Goya once stated, “The sleep of reason produces monsters.” The Monster from the Id from Forbidden Planet is the living embodiment of that phrase. On the alien planet of Altair IV, advanced aliens used incredible technology to make their very thoughts manifest into beings. But in a single night, the entire race was driven to extinction when their own subconscious thoughts manifested and killed them. Years later, a scientist by the name Dr. Morbius finds the aliens’ technology and uses it for his own, and the cycle begins to repeat itself. The monster is only briefly seen, and even then it’s only by the light of laser-blasts and electricity in what is frankly a perfect embodiment of raygun gothic.

Design wise, the monster isn’t particularly innovative, but I really think that’s to its credit. The id is the primal, brutish part of our minds; it would make sense for a monster based on the id’s subconscious desires to be a bulky, angry brute. And of course there’s also the classical element to the Monster as well; Forbidden Planet can be interpreted as a retelling of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, with Morbius as Prospero. If Robby the Robot, as a product of high intellectual science, is the spirit Ariel, then the Monster is Caliban. Caliban of course represented the elements of water and earth in Prospero’s miniature cosmos, and just as Caliban represented the primitive state of the world, the Monster from the Id is representative of the primitive state of the mind. Both monsters play to humanity’s earlier states. The Monster from the Id is, put frankly, a spectacular monster. Its invisibility reminds us that no matter how much we try to suppress our darker feelings and desires, there is always a monstrous part of us just underneath the surface.

3. Ghost Wolf (Fables)

Realistically speaking, all air elementals should be invisible, but so far Ghost from Fables is the only one to step up to bat. Ghost is of course the lost seventh son(?) of Bigby and Snow. He’s essentially an air elemental by virtue of Bigby’s father being the North Wind; it’s complicated. At first nobody even knows Ghost is around until he starts asphyxiating people to death. As an air elemental, air is his food, and the air in the inner city is polluted while the air in certain peoples’ lungs is nice and clean, which I think is a neat urban fantasy detail. After his mom sends him off so he doesn’t get killed, he joins up with his dad for some guerilla terrorism. It’s fine, trust me. I like Ghost first and foremost because we just don’t get a lot of air elemental characters, and when we do they tend to stick to the stock elemental character archetypes. But Ghost is an innocent kid, just a child trying to navigate around the mother of all handicaps. He doesn’t mean to be a monster, he’s just trying to survive. All Ghost wants his to be with his family; like all invisible monsters, Ghost’s is confronted with an issue of presence and acknowledgment. Ghost can’t be seen, but he can be felt, and his character makes us question how much that is worth is terms of bonding.

4. Griffin (The Invisible Man)

There have been a lot of invisible men through the years, but Griffin is still my favorite for his blend of insanity and sadism with a bit of underlying tragedy. Griffin achieved invisibility by use of a special chemical that also drives him insane with its prolonged usage. With that said, it’s hard to know whether Griffin is cruel because of the drug, or if that was always some part of him; both prospects ultimately play in Griffin’s invisibility.

First, while Griffin’s insanity is attributed to the chemicals he uses, it really derives more from his lack of recognition from other people. As an invisible being, people don’t attribute to Griffin all the dozens of minor cues a person receives every day that reassures them that they exist; glancing at them, saying hello, moving out of the way, etc. An invisible man would have to cope with the fact that outside of their own ability to sense the world around them, they don’t really exist. They are a total non-person, dehumanized in the most profound way possible.

This leads to the second point; a person treated inhumanly will begin to act inhuman. A lack of recognition is also a lack of responsibility, a state where you don’t have to be held accountable for your actions. That kind of freedom gives a person the chance to show who they really are. That is the tragedy of the invisible man; Griffin already felt inadequate before he was invisible, and was a complete non-entity with his power, so he used that power to hurt people and lash out, further alienating himself from humanity.

5. Prisoners (Silent Hill 2)

There’s a prison cell in Silent Hill 2. It’s not unusual to go to prison in Silent Hill; at this point it’s practically standard. And it’s also not unusual for the cells in that prison to have horrible monsters waiting inside. What is unusual is when you can’t actually see the monsters, and they don’t really do anything. They’re just… there. Existing. If you listen closely they seem to be chanting the word ‘ritual’, or maybe ‘are you sure’ backwards; it’s unclear. Like most monsters in Silent Hill, especially 2, all sorts of meanings and symbolism can be attributed to the prisoners. But more than anything, they’re there just to be creepy and add ambiance, and they’re disturbingly effective at it.

6. The Dunwich Horror (H.P. Lovecraft)

We don’t get enough abominable half monsters anymore. Not enough deformed masses of flesh that were simply never meant to be. The Dunwich Horror is where you can really see Lovecraft drawing from The Great God Pan in terms of influence. Growing up in rural country, I was always fascinated by the concept of the family monster in the cellar or the barn. The Dunwich Horror is too great, too terrible to be in our world. Its invisibility stems from the fact that it simply isn’t meant for our meager reality. Like Lovecraft says, it has more of its father than its mother in it. The Dunwich Horror reminds me of a storm or some other kind of natural disaster, the kind of thing the ancients would say a god was behind. But it also brings to mind the original definition of monster; ‘monstrum’ were omens in the form of deformities in childbirth, given by the gods. The unnamed Whateley brother is just such an omen; a portent of forces beyond mankind.

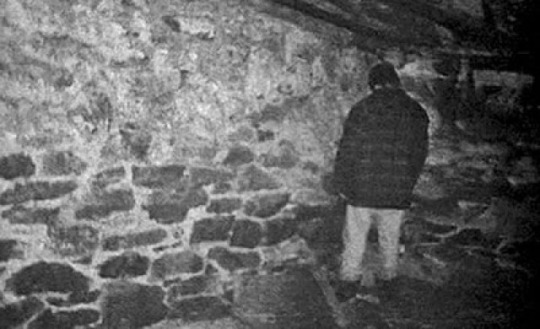

7. The Blair Witch (The Blair Witch Project)

Frankly, the Blair Witch could have gone on the witch list, and probably would have if I was doing a solely pop culture list. But I don’t think that should discredit the Blair Witch as an invisible monster, and there are angles to her absence that would be lost if she suddenly just showed up at the end of a movie. Most obviously, of course, is that the witch is supposed to be an ambiguous entity. Her existence could be entirely fictitious, and she might be nothing more than insanity. The Witch being invisible makes her manifest as a kind of madness, an insanity that appears solely through environmental cues. I would suggest that the Witch is invisible because she is a historic figure; specifically, she is a historic evil. She is something terrible that happened in the past, and even if that evil isn’t seen anymore, it’s still there, a part of the landscape. It’s a very basic horror reading, but I still think it applies to the Blair Witch as a monster.

8. Stealth Sneak (Kingdom Hearts)

I have a lot of good memories of beating up this guy in the Olympus Colosseum. I mean it’s utterly pointless for it to be invisible; the monster’s so huge you can even jump on top of it. But I just love this chameleon monster design! Chameleons don’t get enough play as monsters; they’re always getting upstaged by komodo dragons and iguanas. And obviously the superior color palette is green. I know that shouldn’t matter for a monster that can change color at will, but a line has to be drawn somewhere.

9. Death Sword (The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess)

This guy almost looks like he belongs on the evil weapons list until you actually get to see him. Then when you finally get a look at him, he’s one of the coolest designs in the game! Just look at this horrible thing. What was he? Why is he locked up in this musty old desert tomb? And what did he do that he had to be bound with all these amulets? There’s a lot of mysteries for this mini-boss, and we’re probably better off not knowing. Just appreciate his design and respect the cleaver.

10. Intangir (Final Fantasy VI)

This is just sheer nostalgia. When I was a kid, my cousin let me play her copy of Final Fantasy VI briefly, and I kept running into an invisible monster. Whenever I would attack it enough, it would appear and reveal this giant cat-dragon thing. For years, it became my default to assume that any invisible monster was a buff cat-dragon-man. Blair Witch? Cat-man. Cattle mutilators? Cat-man. Forbidden planet monster? Cat-man. This is Schrodinger’s Cat-Man, where every invisible monster is potentially a cat-man until proven otherwise. Years later, I can see now that this thing is a Behemoth palette-swap, but I like to think of it is a lesser subspecies.

#30 Day Monster Challenge#30 Day Monster Challenge 2#the invisible man#silent hill#kingdom hearts#final fantasy#h.p. lovecraft#the legend of zelda#long post

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Rag and a Bone

As some of you saw, I found one of my “lost” Doctor Who holy grails, Daniel O’Mahony’s A Rag and a Bone! I’d been hunting high and low for this piece of fiction because the idea of O’Mahony writing a Sabbath-centric story was too good. There was literally no information whatsoever online as to what the story was actually about, but I love O’Mahony’s writing and the idea of him tackling Sabbath seemed like a match made in hell.

Finally getting a hold of this story, I must say that calling it “a Sabbath story by Daniel O’Mahony” is incredibly disingenuous, and while I dissect this story and share it all with you, I have to be completely honest and say that I have never been more confused at such a short piece of fiction in my life. Delighted, mind, but very confused.

This story was published in 2003′s Myth Makers Essentials, the famous fanzine’s special 40th anniversary celebration. Myth Makers has been rather a white whale of mine, most long out of print issues holding onto other holy grails, most notably Parkin’s Saldaamir and The School of Doom.

This story is more than a Sabbath tale, being a celebration of Doctor Who’s history, the history of the humans who keep Doctor Who going, as well as a celebration of the 2003 BBC prose continuity that, for all intents and purposes, was the Doctor Who at the time alongside Big Finish’s 1999-2003 years.

It’s also written by one of the closest things Doctor Who has ever had to Clive Barker, meaning that it’s a very disturbing celebration.

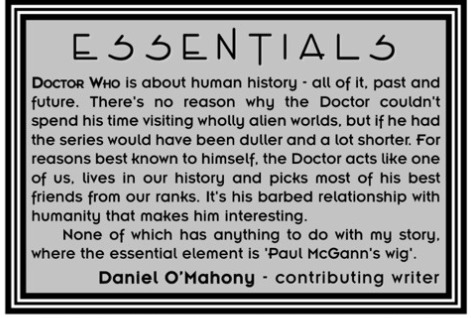

O’Mahony introduces his story with a discussion of what he considers one of Doctor Who’s essential elements:

In O’Mahony’s view of the series, Doctor Who is about humanity. Human history, ingenuity, sacrifice. Without humanity, Doctor Who is nothing. It’s a much more grounded view on the series, and while I’m not sure I quite agree with it, it makes literally every Doctor Who story O’Mahony has written make a lot more sense.

I go into the story’s eccentricities and references (SO MANY REFERENCES GUYS, I’M SO HAPPY) under the cut. Reminder that a) O’Mahony, while a beautiful writer, is a very brutal one; his whole brand is painting objective horror and worldly ugliness in the richest, wine-like prose ever, and it’s definitely not for everyone, and b) this story, like Bidmead’s wonderful With All Awry, is far less literal than it is figurative. The continuity of the time is a factor in the story, but it’s rather useless to try and squeeze it in anywhere, that’s not it’s point.

A Rag and a Bone is an author’s thesis on the spirit of Doctor Who, as well as a simultaneous criticism and celebration of its state in 2003, all the while managing to use Sabbath in the manner he was intended, rarely seen outside of Lawrence Miles’ writing.

I’m not doing every passage of the thing, just the meatier ones. Enjoy and watch me stretch my English degree!

(Note, the story starts in first-person from Fitz’s POV, shifts to weird surreal mix of Fitz and O’Mahony himself, back to Fitz, and then ends with third person omniscient.)

The story opens up simply enough (which, given what appears to be going on, it’s really funny to say “simply”):

Already, this story seems to be following the beats of The Adventuress of Henrietta Street, the idea that in the universe without Time Lords, the universe is free game and humanity (led by Sabbath) needs to step up. But, it’s also a meta commentary. The passage is vague as to what’s really going on, but I think the war/looming disaster is something very specific, that I’ll touch on later.

1) The date. Lmao. What could that possibly be a reference to?

2) Sabbath frequently had agents and allies throughout his novels, and one of these two, the Angel Maker, is actually from Lloyd Rose’s Camera Obscura. I don’t know if that gives an idea of the placement, or just further shows O’Mahony’s “I’m playing with current continuity” schtick.

3) “Miss Kapoor went through the inevitable ritual struggle with her ideological opposite [...] We watched the catfight from the bar balcony - Bollywood Queen of Sin versus the [Angel Maker]...” Perhaps a smirking jab at the rules or sterotypes of storytelling? Set certain characters against the idealogical opposites. Anji often went toe-to-toe with the ideologies and beliefs of people in her novels, far more than Fitz or the Doctor did, so I think that’s what this is a nod to, wrapped in the story’s theme of ritual and symbolism and framed as “the Doctor’s female companion must face Sabbath’s female companion in a duel!!!!!!!”

4) “... a dog-faced parahuman whose name I missed. He was the softest spoken of us all, fresh from the plane of the First Time War, resplendent in Gallifreyan scarlet.” This is Wardog (or a contemporary of Wardog), originally from Alan Moore’s DWM Black Sun Trilogy, portraying the First Time War. He had been recontexualized into Cold Fusion/The Infinity Doctors’ canon in Lance Parkin’s Executive Action, published in 2001′s Walking in Eternity, making him an (admittedly tangential) interesting cog in the EDA’s history and continuity.

1) First time reading this passage, I couldn’t decide if this was purely Fitz or O’Mahony inserting himself into the narrative... and then I realized it’s both. There are two major critical takes on the companions, and this is the first: the role of the companions in the series is to give the audience someone to relate to and, in some cases, live vicariously through. Enjoying the adventure, experiencing the sights, etc. This section is both Fitz Kreiner and Daniel O’Mahony, trying to make sense of what’s going, while the story is already giving us the implications that, despite trying to create a narrative of the Doctor’s condition, he is actually not real.

2) Marvel at Fitz dragging himself in every possible way. Maybe a reference to how the novels (since the VNAs) really hadn’t had any qualms with pushing the flaws and imperfections of their characters? O’Mahony in particular is a writer who would go into great detail about how flawed people were.

3) “... Miss Kapoor - whose sins are much more scarlet than mine - wouldn’t stoop to.” I choose to believe this is a slight reference to how Anji was treating by some writers at the time. The EDA authors wither loved Anji, or hated and demonized her. I could be reaching with that one, but it doesn’t quite make much more sense otherwise. Maybe a reference to her earlier distrust and betrayals of the Doctor (such as in Mark Clapham’s Hope?)

1) This is why I think O’Mahony was attacking the negative handlings of Anji, because the description of her character in the first few sentences is so... good. Beautiful, caring.

2) “The entropy rolling from the Deep...” I’m convinced that, in the end, the threat coming to destroy the universe, the stagnancy, the entropy, the “war,” is Doctor Who’s continued cancelation. Its the 40th anniversary, fourteen years since the show was cancelled, the series kept alive by a small and committed group of book readers and BF listeners (during BF’s early years). I’m adamant that the Wilderness Years produced some of the most creative and original Doctor Who ever, but it is very easy to see why people considered continuing the story a losing battle. More and more, the series slipped out of public consiousness and become more and more of an exclusive cult

3) The second critical take on companions in Doctor Who is a negative one (but one that needs to be said in some cases): in the end, they’re all interchangeable. None of their backstories or quirks matter in the end because they’re interchangeable stereotypes that need to stand their and ask the Doctor questions. What’s gorgeous about this sequence is how it tackles that idea in such a meta and independent way. Anji, realizing that she is, in fact, the latest face in a countless list, takes power from that. She reaches back to her predecessors and uses their abilities, their attributes, for her own agenda, all the while dressing as Anji Kapoor, praying to Ganesh as Anji Kapoor, being the unique and seperate entity that is Anji Kapoor.

4) “Babewyns.” The Ma’lakh grotesques, the villains of The Adventuress of Henrietta Street and one of the major elements in Faction Paradox.

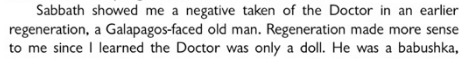

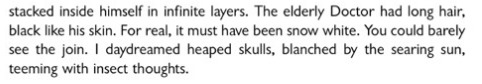

This section operates on two levels, both fictionally and metafictionally. The idea that the Doctor is now a vacuum and Sabbath must either fix or flat-out replace him is the central conflict of their relationship and adversity throughout their novels. There’s also a pun on the EDAs’ “Earth arc” which was the start of the status quo that brought in Sabbath. But, you’ll notice, the “Earth arc” here is not The Burning... it’s An Unearthly Child. Sabbath’s (very morbid) take of what happened to the Doctor isn’t the plot of the EDAs, it’s the beginnings of Doctor Who. The Doctor became part of human consciousness in 1963!

So why is the Doctor now a puppet? A doll, an inhuman echo? Because the show is cancelled, and despite the series living on through, there’s this overwhelming feeling that maybe, just maybe, the final end is fast approaching.

(Actually reading this theme in a story published two years before the show returned is rather nice, isn’t it?)

Sabbath’s take on this is, of course, negative and condescending, while Fitz focuses on the positivity of the Doctor. How he brings goodness and love into our lives, and that by “forgetting him,” (the show being cancelled) we’ve let horrible things into the world. That what Fitz is traveling with is the idea of the Doctor, the “totem” of what’s left, pushing through because Fitz/O’Mahony/the authors/the fans are still holding onto him.

This section also shows how Sabbath really, in the end, cannot replace the Doctor. His best appearances outside Adventuress (Parkin’s Trading Futures and Rose’s Camera Obscura) stressed his limitedness, his flaws, his (debatable) inability to rise to the occasion. He talks to Fitz about power vacuums and the state of the universe, and then Fitz immediately confronts him with his antiquated 19th century beliefs and ideals. Lawrence Miles always claimed Sabbath was never meant to actually replace the Doctor, but several authors, including Lance Parkin, have since expressed that this was not common knowledge and that many authors fully believed Miles was trying to push Sabbath on them as “the new Doctor.” That’s what I think this is a response to (and mind, O’Mahony and Miles were colleagues and friends).

Here we see, we don’t need or want Sabbath. We just want our Doctor back.

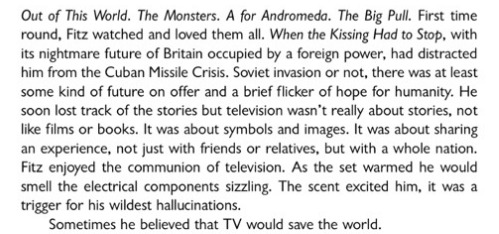

“Sometimes he believed that TV would save the world.” What a sad line, knowing the meaning of this story, huh?

In the end of the story, Fitz and Anji rebuild their “Doctor-totem” from the junk of IM Foreman’s yard, literally using the ruins of the character’s humble 1963 beginnings to build the foundations. But remember, their Doctor is the Doctor of the novels. There’s more work to do to recreate their perception of him.

1) “Dawn Brigades of parahumans and the killer-cats of Gallifrey as they fought over the nature of the newborn universe.” Wardog’s Special Executive (representing the might and will of Rassilon) and the villains planned for the original story replaced by 1977′s The Invasion of Time (who I think here represent the Pythia), clashing during the universe’s minting (later known in Faction Paradox as the anchoring of the thread). This take on Gallifrey’s history (VNAs, EDAs, FP) is THE Gallifrey at the time of 2003.

2) “Their tales would be told by the Needlefolk at the End of Time...” The Needle, seen in The Infinity Doctors, Unnatural History, Father Time, Miranda, and alluded to or contextual related to in Hope and The Gallifrey Chronicles. An important aspect of the lore at the time!

3) This ending is so beautiful, if sad. Here is where Fitz and Anji fully represent the Doctor Who fans and creators at the time. Using their stories, their (new) adventures to further coax their Doctor back to life. He’s built from the junk and refuse of the dead Classic series, he’s lavished with the stories and lore of the Wilderness Years. He is part of humanity, he’s in us, as long as he as friends (the fans) trying to keep him alive.

#Doctor Who#Long post#Daniel O'Mahony#Eighth Doctor Adventures#Faction Paradox#Eighth Doctor#Fitz Kreiner#Anji Kapoor#Sabbath Dei#A Rag and a Bone#Myth Makers Essentials#The Adventuress of Henrietta Street#Lance Parkin#Lloyd Rose

56 notes

·

View notes