#i based her looks off the art of fantine

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I DREW MY GIRL COSETTE BABY LITTLE BABY AWWWWWWWW

#les miserables#les mis#les miz#Cosette#Little cosette#digital art#honestly turned out better than i thought#les mis fanart#les miserables fanart#i based her looks off the art of fantine#and the movie obvi#and the main photo of little cosette#i'd say shes barefooted but i can't draw feet so she got socks lol#speed ran this in one drawing session

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Miraculous Ladybug OC: Lyra Monet

Some time ago, I was just pondering the show and just thought “Wow, Luka is seriously the World’s Most Perfect Man.....there’s NO WAY that man has been single all this time!”

....SO I MADE HIS EX!!

Meet my MLB OC, Lyra Monet!!

(rough sketch, below)

+ More!

Name: Lyra Fantine Monet

Pronounced: Leer-a Fawn-teen Mon-ay

Pronouns: she/her

Sexuality: Undefined

Height: 5'6

Physical description: Short wavy dark brown hair (dyed red at the ends), pale skin, brown eyes, singular freckle on neck

Body type: Lean/slim, faint hourglass figure

Likes: Breakup songs, parks, piano, guitar, baggy shirts

Dislikes: Pickles, coffee shortages, overly strict parents (oh my gosh can you imagine her being bffs with Kagami???...maybe even...something more??😏), loud dogs, traffic

Past relationships: idk insert some random middle school relationship here lol, Luka Couffaine

Reason for breakup: Insecurity?? Jealousy? Maybe their relationship no longer felt special, so he broke it off, but she’s salty that he didn’t even try to look past it and try to make it work between them

Personality: Pretty grumpy and bad with emotions. Think of her as having the personality of a Bakugo and Jirou (from MHA) fusion

(BONUS: Luka + Lyra)

Keep in mind, I’ve only been drawing digitally for a little over a year, and when I made these pieces, I had no concept of anatomy and was impatient to get an art style already, so I practically traced the base models I made in a 3D posing program. Therefore, this is not my 100% original work as I was agitated that my original skills were not up to par with my idea.

I DO NOT do this anymore---thankfully my skills have evolved since I made this (about a year ago!!!) and I use my own sketches as bases!!

However, this IS 100% MY idea and MY OC, so DO NOT STEAL!!! If you wanna draw her/them pls ASK ME!!

Hopefully I can draw an updated version of her, since these ones are about a year old!

#luka couffaine#miraculous fanfic#miraculous au#miraculous ladybug#miraculous ladybug oc#original character#oc#miraculous oc#lukyra#lyra monet#luka#mha#mlb fanart#mlb#morgannotlefay

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brick Club 1.3.3 “Four For Four”

Hugo introduces the chapter by going over the many changes that have happened in Paris since 1817. However, I think it’s kind of an unintentional “the more things change, the more they stay the same” moment when he talks about all these changes, and then a few paragraphs later mentions M. Delincourt and M. Blondeau, law professors at the school whom Bossuet and Marius are still taking courses from 15 years later.

It also feels like a “pay attention” moment here in terms of Hugo talking to the reader. He’s describing these changes that have happened between 1817 and 1862, and yet it’s a moment for the reader to take stock of what has changed in the world between then and the present in which they’re reading, and also what is still the same. Technology is drastically different, social standards are drastically different, and yet you will still find eight friends running around on a weekend having fun, and you will still find a person who falls in love with someone who uses her, and you will still find women who are happy with quick-and-dirty flings, and others who get screwed over by the men in their lives. Technology is ever-changing and constantly advancing, but certain aspects of humanity and human interaction are universal.

In all this discussion of joy and fun, Hugo specifically references Edme-Samuel Castaing, a doctor who in 1822 murdered one close family friend and attempted to murder his brother, in order to gain their fortune. Kind of dark for such a happy occasion. Each chapter leading up to the climax of the dinner seems to have a reference or two that’s just slightly sinister or strange, in the middle of all the happiness.

This chapter really tries to put you in the shoes of the grisettes, with all it’s direct discourse to the reader as well as its beautiful and detailed descriptions of all the places they go and things they do on their outing and how much fun they’re having. The reader is set up for just as intense a disappointment as Fantine here.

Hugo also describes the poet Jean-Pierre-Jacques-August de Labouisse-Rochefort (guy’s got a Tikki Tikki Tembo-level name) walking past them and comparing them to the three Graces, but noting that there’s one too many. Again, this feels like a separation of Fantine from the others. She’s not supposed to be there, not supposed to be in this situation, because she’s not like the other grisettes and perhaps isn’t treating this outing in the same way that the other three girls are.

What are the “keepsakes” Hugo mentions here? I know about Victorian memorial jewelry for mourning or hair-based jewelry and art to commemorate certain occasions, but this seems more romance-based and google is giving me nothing.

Tholomyes is in control here, and everyone knows it, even though Favourite is leading the group. It seems implied that he’s kind of been the one calling the shots the entire time this group has known each other. He’s pretty much a walking display of up-to-date fashion and wealth here. I’m not sure if the “nothing being sacred to him, he smoked” line is in reference to some sort of specific smoking etiquette of the time, or simply just idea that instead of frolicking with the others, he’s hanging back on his own and puffing on this cigar for his own singular pleasure. Either way, giving off pretty big “look at me I’m cool and idgaf” douchebaggery vibes here.

We see Fantine happy! Hugo also draws more attention to her teeth and hair, even having her hold her hat instead of wearing it. Maybe I’m wrong, or maybe working women had different fashions, but my conception of early 1800s hairstyles is fairly pin-heavy updos, so it seems like Fantine’s flyaway hair is just another symbol of her childlike-ness or naivety, especially paired with the description of her “babbling” in the next sentence. Her clothes are also described as being much more conservative than her friends. Altogether the picture of innocent, modest youth.

Erigone is the origin of the constellation Virgo. (Sidenote: trying to look up images of actual ancient Greek masks in the dumpster fire of 2020 is ridiculous.) I couldn’t find any mask references, but there are plenty of Erigone paintings from the late 18th and early 19th century. She also apparently featured in pastoral poetry quite often, so the use of her image here makes sense.

Hugo references Galatea earlier in his description of Fantine, and then again when he says “you could imagine underneath this dress and these ribbons a statue, and inside this statue a soul.” Hugo seems to imply less that she is a sort of Galatea-esque figure, and more that she is like Galatea in that she has a potential inside her that is as yet unrealized. And unfortunately it will remain unrealized, at least until she dies and becomes this symbolic, religious sort of spirit venerated by Valjean.

“A gaiety tempered with dreaminess.” Fantine is so head-in-the-clouds so much of the time. She seems to operate on a slightly different level from everybody else. Somebody mentioned a headcanon of her being autistic? That certainly seems to scan for a lot of this. (I also love it and hate it at the same time. More autistic main characters please! But also less tragic autistic main characters please!)

Hugo is very not subtle about Fantine being a symbol for Innocent And Pure Woman here. He really goes all out when describing her as this working girl who has all this ideal beauty and grace and modesty.

He also really wants to hammer home how important her modesty is specifically. I feel like there are some interesting implications here. Fantine at this point seems to be having as much sex as the other grisettes in her cohort. She gets to be modest and pure despite her sexual activity, while the other grisettes do not. Obviously we don’t really know much about the other girls, so maybe they also have children, but it seems like Fantine may be the only one. So despite the child out of wedlock and the sexual activity, Fantine gets to be pure and modest in personality, in dress, and in symbolism, while her friends are not. Partly I think this is, as Hugo said in the last chapter, an aspect of the powers of Love and how Fantine’s capacity to love so completely makes her different. But what does that say about the other grisettes, who don’t have that passionate and loyal love, and yet are still negatively affected by society or poverty? I mean, I get what Hugo is doing, making Fantine extremely sympathetic, but also making her this pure and modest woman instead of just a regular working girl like her friends seems to imply a betterness? Or at least a Reason for her goodness, while perhaps that reason wouldn’t exist had she been a grisette who acted like the rest of her friends do.

“Love is a fault; be it so. Fantine was innocence floating upon the surface of this fault.” The reason for Fantine’s wisdom is her capacity to love. It’s also her downfall. Because she loves without pretense, without experience, she is ruined. This makes me feel like her “wisdom” isn’t necessarily an intrinsic knowledge of any kind, it’s more like this unhindered ability to love despite the world’s cruelty? Every other main character starts out with a lack of love and then slowly discovers the ability to love (and also to be loved). Fantine starts out with not only the ability to love, but the ability to love completely. She gets screwed over by Tholomyes, and she does harden a little bit, but she never loves Cosette any less. Compare this to the Thenardiers and their children, or Magnon and her children. Fantine’s unique wisdom is that her love does not diminish the more hardship she encounters or the more miserable she becomes.

#les miserables#les miserables meta#brickclub#les mis#les mis meta#is it 5am? am i bad at finishing things NOT at stupid hours of the morning? however did I finish 4 collages for my Les Mis collage project?#yes to all of the above#lm 1.3.3

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

@decayingliberty and I (mostly them) came up with some ideas for how Les Mis characters’ halos would look, as inspired by this post (which was inspired by this post)!!

Enjolras: physical representation is a crown braid with his long hair; actual halo is rays of glowing golden light Grantaire: physical representation is an earring; actual halo is a circle of light in his eye Combeferre: physical representation is a bracelet; actual halo is a smooth gold circlet Courfeyrac: physical representation is a circle tattoo at the base of his neck; actual halo is made of heat waves (more warmth than light, anyone?)-- the shimmer of heat above his head is subtle, but noticeable Bossuet: physical representation is the sun gleaming off his bald head; actual halo is made of the silver lining on storm clouds Joly: physical representation is the gold adornments on his cane; actual halo is a full round circle around his head Feuilly: physical representation is a smear of golden paint on his temple; actual halo is made of stars Bahorel: physical representation is the gold buttons on his red coat; actual halo is a sunbeam halo, like in early Baroque art Jehan: physical representation is a medieval-style circlet; actual halo is made of rainbows Cosette: physical representation is a locket on a necklace; actual halo is made of soft pink light like dawn Eponine: physical representation is also a necklace, but in a different style (a choker, rather than a pendant); actual halo is a crown Azelma: physical representation is an ankle bracelet; actual halo is simple and very shiny and is the color of mother-of-pearl Gavroche: physical representation is a coin; actual halo is multi-color light that shines around his whole body Marius: physical representation is a gold plate; actual halo is a square of pure-white light that glows in the dark Valjean: physical representation is his candlesticks; actual halo is subtle, blink-and-you-miss-it, but it evokes a feeling of love and goodness Javert: physical representation is a medal; actual halo is a spiked circlet in burnished silver or bronze Fantine: physical representation is, like Enjolras, her golden hair; actual halo is a lace halo Mabeuf: physical representation is a pocket watch; actual halo is made of flowers and looks like a dandelion crown Montparnasse: physical representation is a silver ring; actual halo is black and is a broken circle

#angels#libby#les mis#les amis#abc#y#I'm not tagging all of them LOL#and Tumblr won't pick up anything past the fifth tag anyway

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Your Money Is Safe in Art”: How the Times-Sotheby Index Transformed the Art Market by Tiernan Morgan

In 1967, Geraldine Norman was tasked with leading an editorial collaboration between the London Times and Sotheby’s. The project galvanized the conceptualization of art as an investment asset.

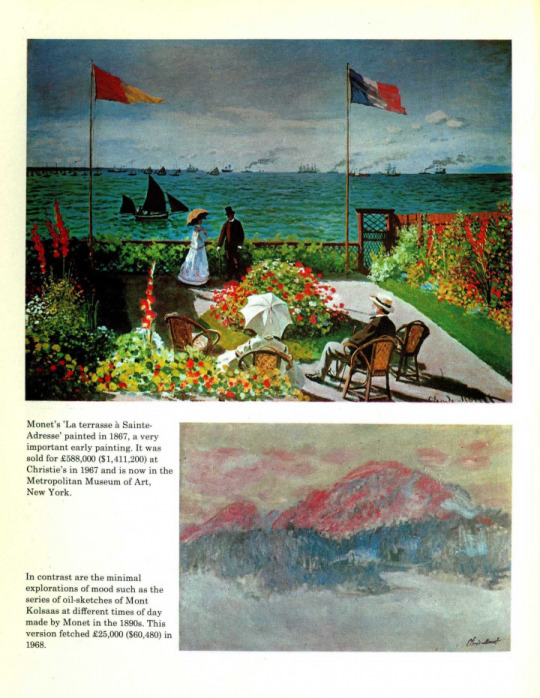

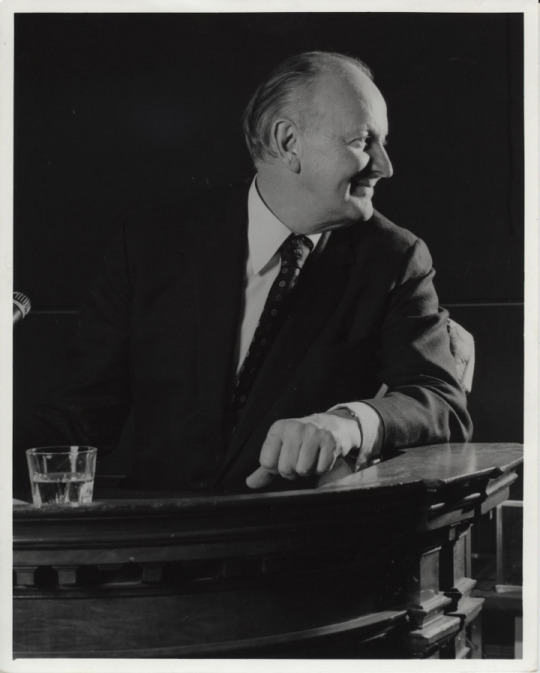

Peter Wilson presiding over the Goldschmidt sale at Sotheby’s, October 15, 1958. For maximum drama, Wilson limited the sale to seven star lots. Guests included Kirk Douglas, Somerset Maugham, and Lady Churchill. The rising prices paid for Impressionist paintings during the 1950s caught the attention of the press and attracted a surge of new buyers (image courtesy Sotheby’s)

“Works of art have proved to be the best investment, better than the majority of stocks and shares in the last thirty years.”

This was the confident declaration of Peter Wilson, the then chairman of Sotheby’s, during his 1966 appearance on the BBC’s Money Programme. Though he was only eight years into his chairmanship, Wilson had already overhauled the fusty image of the art trade. His ingenious pre-sale marketing efforts, celebrity invitations, and black-tie sales had transformed Sotheby’s auctions into major news affairs, and deepened the perception of Christie’s as an antiquated rival.

Reacting shrewdly to the post-war wave of prosperity, Wilson was determined to bring newly moneyed buyers into the fold. He sought to convince businessmen and bankers that collecting was no longer the exclusive preserve of cultured, old-money dynasties such as the Rothschilds, Rockefellers, or Mellons. Crucially, Wilson wanted to instill the notion that art can be an investment. The sudden and precipitous rise of the Impressionist art market during the 1950s may be cited as proof of this. If you inherited an Impressionist painting, you could now sell it for vastly more than your family paid to acquire it. Wilson’s idea just needed to be packaged in an immediate and compelling fashion.

A year after Wilson’s television appearance, twenty-seven-year-old Geraldine Keen — now Geraldine Norman — received a letter in Rome. A graduate of Oxford University and UCLA, Norman had left her job as an editorial statistician for the Times newspaper in London to work for the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN. The letter was a job offer from the paper’s City editor, George Pulay, asking Norman whether she would consider returning to London. He wanted her to spearhead a new editorial collaboration between the Times and Sotheby’s.

* * *

Few people active in the art world today have heard of the Times-Sotheby Index. Those who have are most likely veteran art dealers or retired auction staff. Web results primarily consist of library entries for Norman’s 1971 book on the project.

The first Times-Sotheby Index, published November 25, 1967 (used with the kind permission of The Times Archive) (click to enlarge)

Published regularly in the Times between 1967–1971, the Times-Sotheby Index purported to chart the changing prices of art sold at auction. Each feature centered on a single movement or department (Impressionism, English silver, Chinese ceramics, etc.) and were accompanied by charts that illustrated sales prices from the early 1950s to the present.

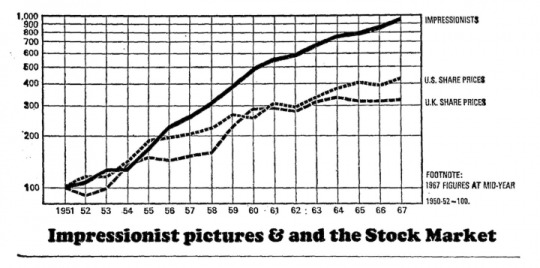

The first index, published on November 25, 1967, includes seven prominent graphs dedicated to Impressionism. Six charted the prices paid for specific artists since 1950–52: Renoir (“up 405%”), Fantin-Latour (“up 780%”), Monet (“up 1,100%”), Sisley (“up 1,150%”), Boudin (“up 835%”), Pissarro (“up 845%”). The seventh graph includes three indices, the value of Impressionist paintings, US share prices, and UK share prices — the former vastly outpacing the latter. The message was clear: Art is a hot commodity, and its sale value can and should be conceived in much the same way as a stock on the Dow Jones or FTSE 100.

The market for contemporary art has grown exponentially since the 1960s. It’s now commonplace to describe the intricacies of an artist’s particular “resale value,” or “collector base.” Innumerable artworks reside out of sight within heavily secured free ports, where their owners avoid custom duties. The press routinely report record sales, rehashing features on the best-selling artists and publishing listicles on the world’s most expensive works. Companies such as Artnet, Collectrium, Artprice, and ArtRank sell their data and insights on sales and trends. Speculation is the norm. However, in 1967, the Times-Sotheby Index’s brazenly analytic conception of art’s value was, with a few exceptions, unprecedented and highly radical.

A graph from the the first Times-Sotheby Index (used with kind permission from The Times Archive)

“Our culture has been schooled to think of works of art as investment commodities,” wrote Robert Hughes in his renowned 1984 essay, “Art & Money.” “The art market we have today did not pop up overnight … I think of it as beginning with a curious enterprise called the Times/Sotheby Art Indexes.” The critic continued:

Perhaps it was the graphs that did it. They gave these tendentious little essays the trustworthy look of the Times financial page. They objectified the hitherto dicey idea of art investment. They made it seem hard-headed and realistic to own art.

The index was reportedly conceived during a lunch between Pulay, Wilson, and Brigadier Stanley Clark. As Sotheby’s PR agent, Clark had played an instrumental role in the company’s 1964 acquisition of Parke-Bernet auction house, which vastly expanded Sotheby’s presence in the US. (Christie’s did not open its own sale room in New York until 1977.)

Together, Clark and Wilson landed a spectacular PR coup in convincing the Times to collaborate on the feature. The name alone guaranteed a tranche of regular free press for Sotheby’s and the association with the Times instantly bestowed authority on the index’s findings. Though they conceived it, neither Wilson nor Clark actually brought the index to life. That responsibility fell squarely on Geraldine Norman’s shoulders.

I interviewed Norman, now 78, over the phone. By her own admission, the project did not get off to a smooth start. “I was worried because I thought art actually can’t be valued and that it’s ridiculous to put prices on things and measure them in an index,” Norman told me. “I panicked all one night and at the end of it I decided, well … I may as well do it.”

The project presented an obvious methodological conundrum. Unlike gold or oil, art is not a singular commodity. Every piece is unique, and an artist’s oeuvre will always be comprised of works judged to be of a comparatively higher or lower quality. Aesthetic judgements, regardless of trends or received wisdom, are subjective. Condition, provenance, and size are just a few of the factors that have a bearing on how an artwork is appraised.

Geraldine’s biography and portrait on the dust jacket of Money and Art: A Study Based on the Times-Sotheby Index(1971) (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic unless otherwise noted)

Tracking the prices of every Impressionist painting sold at auction would be an unmanageable task, so Norman’s solution was to compromise. For the first index, she focused on six “representative” painters. Monet and Renoir stood as the movement’s perceived masters, while Fantin-Latour and Boudin represented lesser “companions.”

Norman then deferred the issue of quality and variance to a Sotheby’s specialist, who divided up each artist’s oeuvre into groups of “roughly equal intrinsic value,” or as Norman jokingly put it, “from masterpiece down to crap.” To do this, Norman would sit with the relevant specialist and review the sale records for each artist documented by the auction house. Having determined her parameters, Norman tracked the prices paid for each artist before combining the results into a single index. “The method adopted in this study,” Norman announced in the Times, “was to scale the actual price paid for each picture either up or down to an equivalent price for an average example of the artist’s work.” The data included pictures sold by Sotheby’s, Christie’s, Parke-Bernet, and “when possible, the Paris sale rooms since 1950.”

A color plate from Money and Art: A Study Based on The Times-Sotheby Index (1971)

Norman’s method had a number of inherent shortcomings. It functioned on the assumption that the value of one example of an artist’s work would remain a constant multiple or fraction of the value of any other, unaffected by the realities of changing tastes or demands. More Renoirs might be sold in one year than another, and of those works, some could far exceed or fall short of expected auction prices. An exceptionally cheap or expensive painting would register on a graph as a sudden downturn or surge. To avoid this, Norman excluded so-called masterpieces, which would likely fetch exceptional prices. Another major criticism leveled at the index was that it could only provide an approximate insight into auction prices. Private transactions, and sales by galleries and dealers — by far the bulk of the art economy — were excluded. It was also invariably problematic that a Sotheby’s specialist would have say over which works were and were not “representative.”

Norman was entirely upfront about these limitations, many of which she discussed in the article accompanying her first index. It’s clear that she was sincere about making the best of a near impossible assignment, but she also understood the genius of Wilson’s vision. “It was [his] brilliance that he saw how it could affect his sales figures,” Norman told me. “I don’t think I saw it at the time as promotional [but] it worked as a Sotheby’s promotion.”

* * *

The conceptualization of art as an investment commodity was not without precedent. Émile Zola’s 1886 novel, L’œuvre (“The Work” or “The Masterpiece”), characterized the increasingly speculative character of the late- nineteenth-century art market. The novel features a character named Naudet, a Parisian art dealer who only engages with the “moneyed amateur” who buys pictures “as he might buy a share at the stock exchange.” Naudet’s sales pitch is as follows:

“Look here, I’ll make you a proposal; I’ll sell it you for five thousand francs, and I’ll sign an agreement to take it back in a twelvemonth at six thousand, if you no longer care for it.”

After that Naudet loses no time, but disposes in a similar manner of nine or ten paintings by the same man during the course of the year. Vanity gets mingled with the hope of gain, the prices go up, the pictures get regularly quoted, so that when Naudet returns to see his amateur, the latter, instead of returning the picture, buys another one for eight thousand francs. And the prices continue to go up, and painting degenerates into something shady, a kind of gold mine situated on the heights of Montmartre, promoted by a number of bankers, and around which there is a constant battle of bank notes.

Édouard Manet, “Émile Zola” (1868), oil on canvas, Musée d’Orsay, Paris (photo by unknown, via Wikipedia)

Naudet’s approach, and those of the dealers on whom he is likely based, prefigured the market manipulation we recognize today, an example being the auction phenomenon of “flipping.” The nineteenth-century art market is wonderfully illustrated in Philip Hook’s Rogues’ Gallery, which includes a chapter dedicated to Paul Durand-Ruel, the innovative art dealer who championed the Impressionists. As Hook observes, Naudet’s approach can only function if a dealer establishes a monopoly for an artist’s work, and Durand-Ruel operated shrewdly in this regard. “I am entirely disposed to take all your paintings,” wrote the dealer in a letter to Pissarro. “It is the only way to avoid competition, the competition that has prevented me from boosting your prices for so long.”

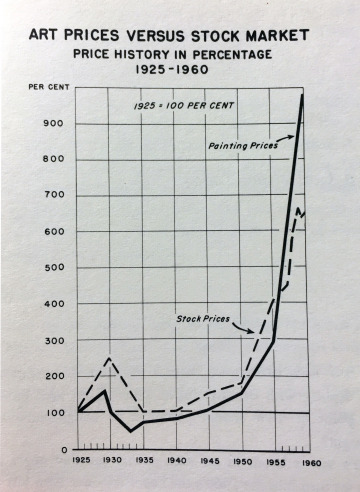

Norman was also not the first to demonstrably equate auction sales to stock values. In 1961, art collector Richard H. Rush published Art as an Investment, a beginner’s guide to collecting. Each chapter included graphs dedicated to the changing sale value of different schools of art.

Rush’s methodology was strikingly similar to Norman’s, the key difference being that the collector limited his data to “medium” sized paintings that would be “a convenient size to hang on the wall.” Buried in one of his chapters, with little fanfare, is an additional graph comparing stock prices to auction sales. “Despite the bull market in stocks after the 1957 recession, paintings forged far ahead of the stock market to the year 1960,” wrote Rush, “and despite the setback in the stock market in that year, painting prices still rose.” Norman said she was unaware of Rush’s work. “That’s shaming. I should have known about it, but I didn’t.”

A graph from Richard H. Rush’s Art as an Investment (1961)

Despite its title and graphics, Rush’s book is not a full-throated endorsement of art as a commodity asset. The collector’s guide champions studiousness, patience, and above all, a life-long commitment and passion for art.

The important collectors of paintings usually do not sell. They look upon their paintings as their treasure and a major love of their lives to which of course a price tag can be attached but which usually need not be turned into cash during their lifetimes. It is enough to know that the value is there and that it can be passed on to heirs or public institutions as their contributions to the culture of society.

Norman’s headlines during the late ‘60s were less equivocal. “Your money is safe in art,” the journalist declared in June 1968. “Fine art treasures are a truly convertible currency and will maintain their value on the international market.”

Unsurprisingly, the index attracted the ire of readers, critics, and other arts professionals, many of whom wrote to the Times. One such letter was published in October 1968. “The Times Sotheby Index … represents the very height of vulgarity and crass commercialism,” wrote L.J Olivier of Coggeshall, Essex. “One day, please God, the tide will turn. The air conditioned vaults of philistine businessmen will be broken open and the contents expropriated and your wretched art journalists will be stoned to death with fake Etruscan bronzes.” “Paeans of praise be to Mr. L. J. Olivier,” James R. de la Mare of Woodchester, Gloucester, responded. “An era in which, say, a Raphael is less a masterpiece than a ‘hedge against inflation’ deserves the choler of your correspondent and, perhaps, shames us all.”

An excerpt from the Times, December 30, 1968 (used with kind permission from The Times Archive)

Art dealers were also incensed by the index. “I remember Sir Geoffrey Agnew being particularly angry about it,” Norman told me. “He certainly expressed it to me personally. Somehow, I added him into the Index and he was happy, but I can’t remember how I did that. The sales pitch said art has a wonderful, intangible value — that it is above the whole sordid commercial world. I think [dealers] believed that. Sir Geoffrey did anyway.”

Carmen Gronau, the head of Sotheby’s Old Master department concurred. “She said, ‘it’s a nonsense game; you can’t do it with old masters,’” Norman recalled. “‘You’re not going to have an old master index.'” Peter Wilson’s reaction was emphatic. According to Norman, Wilson sat Gronau down with a bottle of whisky and a stack of sales records. After months of evasiveness and a late night’s work with Norman, the specialist reluctantly settled on the schools and artists they thought ought to be incorporated into an Index. Julian Thompson, the head of the Chinese art department and a mathematician, also had reservations. “I think it’s pretty suspect,” he reportedly told Norman, “but I can see what you’re doing.” Aside from procuring whiskey for Gronau, Norman maintains that Wilson never sought to influence or interfere with her work. “He watched from afar with deep interest.”

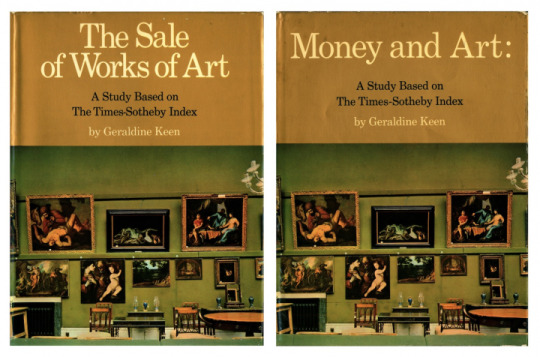

The opposition to art’s evolving commodity status directly impacted the production of Norman’s 1971 book. The journalist’s UK publishers rejected her proposed title, Art and Money: A Study Based on the Times-Sotheby Index, opting for the slightly more sober The Sale of Works of Artinstead. Only US editions bore Norman’s intended title.

A side by side comparison of the UK and US editions of Norman’s book

In a scathing review entitled “In Sotheby-land the graphs go up,” New York Times critic Grace Glueck dismissed Norman’s methodology as a “complex maze of simplistic reasoning.” “I heartily recommend [the book] to those who collect not art, but money,” she wrote, “and can afford to shell out $20 for [what] is really nothing more than a cumbersome advertisement for Sotheby’s.”

As part of her critique, Glueck observed that Norman had not identified the percentage of works that were “bought-in” below their reserve price, the undisclosed minimum bid at which a consignor is willing to sell their work. If the auctioneer fails to attract bids higher than the reserve, then the work is unsold (i.e. bought-in or “passed”). In lieu of real bids, auctioneers will conjure imaginary ones in order to surpass the reserve price (a practice known as “chandelier bidding”). At the time, neither Christie’s nor Sotheby’s publicly disclosed the percentage of bought-in lots, thereby maintaining the illusion of unrelenting demand. Glueck also chided the fact that the Timespromoted Norman to sale-room correspondent amidst her ongoing work with the index. “[I] wonder how Christie’s, Sotheby’s London rival, likes that?” the critic reasoned.

Glueck’s criticism of Norman’s conflict of interest, though fair, proved to be misplaced. By 1971 — the very year Art and Money went to print — Norman’s professional relationship with Wilson had evaporated, and she was held in equal contempt by Peter Chance, the chairman of Christie’s. Ironically, it was Norman’s determination to shed light on auction reserves that marked the death knell of the index.

* * *

The standard narrative is that Wilson scrapped the Times-Sotheby Index after auction sales began to dip. Indeed, the last feature to be published, headlining “English silver’s lacklustre market,” could hardly be described as a press coup for Sotheby’s. Norman’s feature had documented a few price declines over the years (“No rags to riches story for English porcelain,” November 1968; “Fall in Chinese ceramics,” September 1970), but the truth of its demise is far more complex.

Peter Wilson was chairman of Sotheby’s between 1958 and 1980. He began his career at the company in 1936 as a porter in the furniture department (courtesy Sotheby’s)

During the Summer of 1970, Norman informed Wilson and Chance that she was writing a critical article on the secrecy surrounding bought-in lots. Norman observed that fictitious names (some of which were pseudonyms used by secretive bidders) regularly appeared on the sale lists distributed to subscribers. Only later did the practice become widely known. “We would go behind a curtain after every sale,” Fiona Ford, a former Sotheby’s press officer, later relayed to Philip Hook, “and find out from Peter Wilson what we were expected to lie about.”

Much of what Norman told me is corroborated by John Herbert’s 1990 memoir, Inside Christie’s, which delved into the journalist’s falling out with Wilson and Chance. Herbert, an ex-journalist who worked as Christie’s PR director between 1959 and 1985, was shocked by the industry’s “economy with the truth.”

It’s true that we didn’t volunteer information on bought-in lots, if we weren’t asked about them, and the standard procedure was that the total given would be the knock-down and include bought in lots. Geraldine, once she was confident of her position, decided this was not good enough; she wanted, certainly when it came to important sales, every price in the catalogue and whether the work was sold and if so who the buyer was. With this information she could work out the percentage sold and bought in. It was strange that no other journalist had ever asked for such basic information before.

Norman, who had so keenly propped up art’s burgeoning investment status, was now deploying her expertise in a bid for greater market transparency. Predictably, her queries were not well received by Wilson or Chance. The chairmen met with the Editor of the Times, Sir William Rees-Mogg (father of Conservative MP and ardent Brexiteer Jacob Rees-Mogg), in an effort to quell her story. As Norman told me:

They were both outraged. The obituaries editor told me that it was not a question of a two-faced villain, but a four-faced villain, because each of them came with their deputy. Rees-Mogg listened to them and then he said quietly, “gentlemen, I’m sorry but I think this is a matter of public interest. We will be publishing her article.”

Peter Wilson never forgave me for that. He felt that I had let the side down, that it was disloyal. He first said that he was going to close the doors of Sotheby’s to me, that I was never to be allowed into Sotheby’s again, but he actually couldn’t do that because I was the Sale-room Correspondent of the Times [laughs]. When we met, he used to shake with anger.

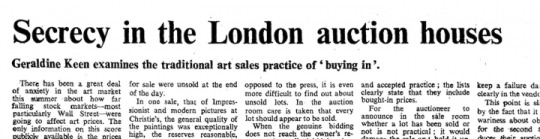

On July 16, 1970, the Times published Norman’s article, “Secrecy in the London auction houses.” Eight months later, the paper published her final Times-Sotheby report.

Geraldine Norman, “Secrecy in the London auction houses,” The Times, July 16, 1970 (used with kind permission from The Times Archive)

Norman’s July article exposed the use of fake names, but also outlined the defense for such secrecy. Auctioneers maintain that if bidders knew reserve prices, they would be disinclined to bid beyond them. Works known to have been bought-in might be perceived as undesirable and can therefore be harder to resell. Yet, such secrecy runs entirely counter to the ethos of the public auction. “The auction rooms have profited greatly from the public and open nature of their transactions,” wrote Norman. “Their secrecy over unsold lots is thus something of a contradiction.” In the face of increasing scrutiny, the auction houses gradually amended their policies. By 1975, both companies excluded bought-in lots from their sale lists.

“Few journalists can claim, as [Norman] can, to have forced two world famous firms to change their hallowed practices by sheer persistence and strength of mind,” wrote Herbert.

I remember our first meeting. I saw this small girl get out of a battered German bubble car, dressed — I hope she will not think me ungallant — rather like one of Augustus John’s gypsies, with wisps of hair flying in all directions.

According to Herbert, Chance became obsessed with Norman. “There’s nothing, in my opinion, which is not beyond the line of duty when it comes to controlling that woman,” he reportedly snapped. The Christie’s chairman ordered Herbert’s department to analyze Norman’s auction coverage and determine the extent of her bias for Sotheby’s. The report concluded that Norman had in fact given Christie’s approximately 24% more coverage, a finding that Herbert attributed to the pre-sale exclusives he regularly touted her. “More time was spent on discussing what to do about Geraldine at board meetings than on any other one subject.”

Geraldine with her husband Frank Norman at the Vatican Museums, 1969 (courtesy Geraldine Norman)

By 1974, it’s clear that Norman’s opinion on art’s commodity value had cooled considerably. “There are and always will be marvellous opportunities for speculation in the art market,” she wrote in an article examining British Rail’s art investments, “but the idea that art is a solid and safe investment medium is a fallacy.”

In 1987, Norman left the Times to join the Independent, where she worked until 2000. The journalist has published numerous books, including a critically lauded history of the State Hermitage Museum. As a result of the project, Norman later became Director of the Hermitage Foundation UK, a registered charity dedicated to fundraising and cultural exchange. “It’s very eccentric,” Norman remarked about her career, “but it all hangs together.” Despite their falling out, Norman spoke admiringly of Wilson. In Art and Money, she credited his chairmanship with building the “most dynamic auctioneering complex in the fine-art market.” “I would hasten to say I think he was charming and a genius,” Norman told me. “I was very sad when he took against me because it had been great fun working with him.”

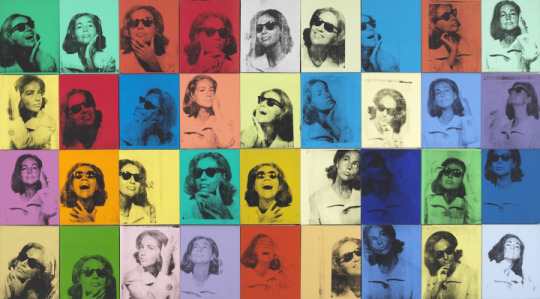

By the time Art and Money was published, the findings of the Times-Sotheby Index had been syndicated in publications around the world, including the New York Times, Süddeutsche Zeitung, and Connaissance des Arts. Two years later, collectors Robert and Ethel Scull sold works from their contemporary art collection at Sotheby’s Parke-Bernet for a staggering profit, definitively shifting the market’s focus to contemporary art.

Andy Warhol, “Ethel Scull 36 Times” (1963), silkscreen ink and acrylic on linen, thirty-six panels: 80 × 144 inches overall, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; jointly owned by the Whitney Museum of American Art and The Metropolitan Museum of Art; gift of Ethel Redner Scull (© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York)

Robert Scull, a consummate self-promoter, keenly stressed the disparity between the prices he and Ethel originally paid with those they had fetched at auction. Robert Rauschenberg’s “Thaw” (1958), which the couple bought directly from the artist for $900, sold at the auction for $85,000. The extraordinary mark-up in prices inspired the now pervasive model of buying new work and holding out for a profit. Though the Scull auction is routinely cited for cementing this line of thinking, it was the inexorable logic of features such as the Times-Sotheby Index that catalyzed it. “It proved a self-fueling engine,” wrote Philip Hensher in 2006. “By demonstrating that pictures could be thought of in this way, the index guaranteed that they would be.”

“I think it was the starting point because it was so blatant,” Norman remarked.

Picasso up 3 points, Renoir down 2. It didn’t strike me that it was having an immediate impact on the art market. It changed people’s minds and way of thinking, but it took a matter of years to work its way through. It was only ten years later that I began to realize that it had actually made a sea change in buyers. It was a gradual thing.

John Herbert’s conclusion was firm. “No one journalist had such an impact on the art market from 1967, whether on auction houses, museums, or members of the fine art trade as Geraldine.”

Source: https://hyperallergic.com/476003/your-money-is-safe-in-art-how-the-times-sotheby-index-transformed-the-art-market/

0 notes

Text

usse 55

Floral Patterns ~ An Essay About Flowers and Art (with a Blooming Addendum.)

Share

by Andrew Berardini

A Change of Heart installation view at Hannah Hoffman Gallery, Los Angeles, 2016. Courtesy: Hannah Hoffman Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Michael Underwood

“Without flowers, the reptiles, which had gotten along fine in a leafy, fruitless world, would probably still rule. Without flowers, we would not be.”

— Michael Pollan, The Botany of Desire (2001)

“Not even the category of the portrait seems to have ever attained the profound level of painterly decrepitude that still life would attain in the sinister harmlessness in the work of Matisse or Maurice de Vlaminck… the most obsolete of all still-life types.”

— Benjamin H. D. Buchloh on Gerhard Richter’s Flowers (1992)

Don’t worry, nobody’s looking. Go ahead.

Stop and smell the flowers.

Feel that sumptuous perfume blooming from those spreading petals. That’s pleasure. That’s sex. That’s the body lotion of the teenage beauty fingering your belt buckle to take your virginity (or the one you wore when you tugged that belt off your first). That’s your grandmother’s bathroom and the heart-shaped wreath at her funeral. That’s the lithe fingers and supple wrists of the florist, an emperor of blooms arranging the flowers for your mother just so.

Those petals, that scent, those colors.

Somehow flowers have become a decrepit subject, “the most obsolete of all still-life types,” to use Buchloh’s words. Despite the eminent Octoberist’s antipathy (and he is hardly alone in his disdain), flowers in art are back in bloom.

Flagrantly frivolous, wholly ephemeral, though ancient in art, the floral’s recent return as a major subject for artists marks a pivot toward those things that flowers represent: the decorative, the minor, the ephemeral and emotional, the liveliness of their bloom and the perfume of their decay, a sophisticated language of purest color and form that can be both raw nature and refined arrangement, poetic symbolism rubbing against the political mechanisms of value, history, and trade. Flowers are fragrant with subtle meanings, each different for every artist who chooses them as a subject. They are a move away from literal explications, self-righteous cynicism—and toward what, precisely? Let’s say poetry.

Bas Jan Ader, Primary Time (still), 1974. © Estate of Bas Jan Ader / Mary Sue Andersen, 2016 / Bas Jan Ader by SIAE, Rome, 2016. Courtesy: Meliksetian | Briggs, Los Angeles

Free in the wilderness, rowed in gardens, in bouquets on tables, or as a decorative aromatic around the dead, flowers offer an opportunity for a simple, sensual pleasure—both a temporary escape and a corporeal return. Their origins as a species are a bit shrouded in mystery, but most who study flowers and evolution agree that they came about in order to employ insects and animals in their reproduction (a process that surely continues with our artful interventions). They lure with beauty, eventually tricking humans into agriculture and the dream of making such fecund and lively yearnings permanent, into art.

First and foremost, flowers are the sex organs of plants. Those bright colors and elaborate bodies were meant to turn us on. Georgia O’Keeffe transformed her blossoms from still-life representation into a kind of abstraction that tongued that first truth of flowers; all of her blooms wore the faces of interdimensional pussies. Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs of flowers look even more suggestive to me than some of his more obviously lusty snaps of men in various states of undress and erect action.

Though their flounce and curve have a pornography of color, flowers as a metaphor can be easily read as safe, sanitized stand-ins for the real musk and squelch of sex. A vase of flowers in grandma’s parlor might be less notable than a bouquet of dildos erupting out of a bucket of lube. The opposite of badass to all the tough boys playing with their power tools, flowers to them are for old ladies and sissies and girls. Macho minimalists preferred stacks of bricks and sheets of steel to prove the heft of their seriousness. Besides, the florals look too comfortably bourgeois for the shock and spectacle of self-serious avant-gardists, though Giacomo Balla’s Futurist Flowers(1918-1925) look as radical as anything else those defiant Italians cooked up.

Virginia Poundstone: Flower Mutations installation view at The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, 2015. Courtesy: The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield. Photo: Jean Vong

Though flowers have appeared in art for thousands of years, first evidenced in funerary motifs in the earliest Egyptian dynasties, they’ve been used mostly as a sideshow, a decorative motif, a signifying prop. But around 1600, during the time of the tulip mania that rubbled the Netherlandish economy, Dutch artists began to paint blooms as the main attraction: finely wrought bouquets with delicate strokes, an idealistic botanist’s attention to perfection and detail, each variety laden with meaning, some held over from religion, some devised for newly invented varietals. This efflorescence came about with the disposable income of the bourgeoisie and the introduction of the tulip to international trading with the Ottoman Empire; in the court of Constantinople, flowers were all the rage. As an object of desire and prestige, the flower earned its worth as a central subject.

By the Victorian era, the language of flowers became wildly popular, as that repressed period needed something sexy to finger, especially for the corseted women. The frivolity of flowers was perhaps an area of knowledge the patriarchy let ladies have mastery over, but male artists weren’t ignoring the chromatic potential of blooms, either. With wet smears and hazy visions, Vincent van Gogh and Claude Monet were among the best floral daubers of their time (with a solid shout out to the drooping beauties of Henri Fantin-Latour, whose 1890 painting A Basket of Flowers made it onto New Order’s 1983 album Power, Corruption, and Lies, itself an elliptical Richter reference). Flowers to these painters were a way to explore the power and range of their medium with unfettered color. “Perhaps I owe it to flowers,” said Monet, “that I became a painter.” As art took an intellectual turn, however, flowers fell out as serious subjects and became the provenance of Sunday painters, appropriate only for the marginalized. Yet as outsiders increasingly collapse binaries, the center cannot hold and vines snake into the heart of power to bloom a variety as diverse and beautiful as the spectrum of humanity.

A Change of Heart, an exhibition organized by the curator Chris Sharp at Hannah Hoffman Gallery in Los Angeles in summer 2016, touched on dreams and contemplations I’d been having about obvious forms of beauty and their force in art as both assertion and escape. Sunsets, moonlight, waterfalls, and, of course, flowers, all easily dismissed as sentimental kitsch, seemed to be enjoying a new life, born of a self-conscious romanticism that acknowledges these subjects as perhaps decayed and misspent, but lets their beauty sweep them up anyway. Sharp stated in the press release that the work in the exhibition “embraces the floral still life in all its formal, symbolic, political and aesthetic heterogeneity… a radical and even dizzying diversity of approaches, including the queer, the decorative, the scientific, the euphemistic, the memento mori, the painterly, the deliberately amateur and minor as a position, and much more.”[1]

Willem de Rooij, Bouquet IX, 2012. Courtesy: the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles. Photo: Michael Underwood

From historical works by Andy Warhol, Alex Katz, Ellsworth Kelly, Jane Freilicher, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, and Bas Jan Ader to art made much more recently by Camille Henrot, Willem de Rooij, Amy Yao, Kapwani Kiwanga, and Paul Heyer, the pieces in A Change of Heart approach the floral in wholly unique ways. Rather than cordoning off the artists in Sharp’s excellent show, I’m going to weave their methods, ideas, and visions into a larger conversation, some aspects of which were quite likely on the curator’s mind, as any art gallery and its resources can only be so expansive. In London as well, the gallerist and curator Silka Rittson-Thomas has opened up a project space and storefront called TukTuk Flower Studio to host the floral visions of contemporary artists.

Of course some artists in recent history focus on the base, mass appeal of flowers, like Warhol and his iconic screenprint Flowers (1964), or Jeff Koons with his giant, bloom-encrusted Puppy(1992) and solid shimmering metal of Tulips (1995-2004). But despite the blank-faced games of pop cipher employed by Warhol and the spirited industrial-scale exuberance of Koons, I can’t help finding a whisper of contempt in both, a pandering hucksterism, giving the people what they want. This obviousness and its exploitation is of course a part of the story of our modern interactions with flowers, but it obscures a more nuanced narrative.

Capitalism has so often turned beauty as a notion into kitsch, or as Milan Kundera puts it, “a denial of shit,” and we can find this modern kitsch in the unblemished bloom on the cheeks of a Disney princess, or in “America’s most popular artist” Thomas Kinkade’s creation of an imagined past of perfect old-timey townships, a good old days that glosses over all the problems of inequality and oppression endemic to that era. Donald Trump is the kingpin of this kind of kitsch these days. The best of our feelings can be easily hijacked for political purposes, but it is a mistake to cynically dismiss those feelings simply because others would take advantage of them.

All aspects of creation are beautiful enough to need little human improvement, including flowers. As John Berger writes in The White Bird, “The notion that art is the mirror of nature is one that appeals only in periods of skepticism. Art does not imitate nature, it imitates a creation, sometimes to propose an alternative world, sometimes simply to amplify, to confirm, to make social the brief hope offered by nature.” [2] We attempt to capture the power of these moments not to improve upon them, but to fix their power, to make ephemeral hopes and desires into something more permanent. Perhaps the natural versus the human-made is one more collapsing binary, and the diversity of flowers allows for such wild variety that the simple monolithic subject of “flowers” can’t easily contain it. In using flowers as a subject, artists have gravitated from the classic still life (like Richter on the ass end of Buchloh’s anti-floral sentiment), with its entwined poetical and political meanings and their elaborate symbolic language, operating at the decorative margins, toward the center. This can be traced in the atmospheric floral patterns of Marc-Camille Chaimowicz (enjoying a fantastic resurgence of interest), the pastel squiggles of Lily van der Stokker, and the softly erotic washes of Paul Heyer. Pulling the margins into the center is also of course one of the great political projects of our time.

Felix Gonzales-Torres, “Untitled” (Alice B. Toklas’ and Gertrude Stein’s Grave, Paris), 1992. © The Felix Gonzales-Torres Foundation. Courtesy: Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York

The poetical-political intertwining in flowers has a few significant contemporary exemplars. Felix Gonzalez-Torres imbued common objects with profound poetic and political force throughout his work, and included in A Change of Heart was his photograph of the flowers on the graves of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas. In a single snap, an almost slight touristic photograph, the artist reveals a nexus of forces around flowers: as memorial, as assertion of love with all its political and artistic forces, as vaginal (given their lesbian sexuality), and as a visual poem that matches Stein’s “A rose is a rose is a rose…,” itself of course an invocation of William Shakespeare’s “A rose by any other name would smell just as sweet.” A rose is a rose and love is love, by any other name.

With a blend of flowers, sometimes artificially constructed, and his own indexical variety of sharp critique, Christopher Williams takes a more distinctly political focus, working wholly on reclassifying a collection of flower models (fakes, to be clear) not into botanical hierarchies but into political relevance. The photographs in Angola to Vietnam* (1989) are snapped pictures of selected replicas from the Harvard Botanical Museum’s Ware Collection of Blaschka Glass Models, made between 1887 and 1936. Williams, however, focuses on flowers from countries where political disappearances were recorded in 1985, reclassifying them by country of origin rather than by the museum’s system. But although these are certainly flowers, one gets the feeling that Williams wants to undermine their bourgeois beauty and the colonial impulse that collected, modeled, and classified them.

This sharply political act finds force in Taryn Simon’s photo series Paperwork and the Will of Capital (2015) and Kapwani Kiwanga’s ongoing series Flowers for Africa (begun in 2012), with their similar focus on floral arrangements made for banquets celebrating important political moments. Simon’s pictures tend to flatten the arrangements into manipulated environments. Kiwanga presents living bouquets, with the intention that they rot over the course of the exhibition (I watched one whither in A Change of Heart) so as to describe a complex physical poetic. For Kiwanga, the flowers that stood on the tables of important moments in politics represent the colonial import of European flower arrangement: where, for what, and by whom these flowers were cultivated, but also the hope and heartbreak involved in many of the agreements they witnessed. Some represented a marked turn toward liberation, while other accords withered along with the flowers. (Both of these projects echo, for me, Danh Vo’s display of the chandeliers from the Hotel Majestic in Paris hanging over the agreement that ended the US-Vietnam War.)

Zoe Crosher, The Manifest Destiny Billboard Project in Conjuction with LAND, Fourth Billboard to Be Seen Along Route 10, Heading West… (Where Highway 86 Intersects…), 2015. Courtesy: the artist. Photo: Chris Adler

Zoe Crosher’s billboard series Shangri LA’d (2013-2015), produced in collaboration with LAND, displayed a lush array of flowers and greenery arranged by the artist and shot in a storefront in Los Angeles’s Chinatown formerly occupied by the Chinese Communist Party. As one drove across the country on the transcontinental highway, I-10, the flowers rotted further with each successive picture, until a decayed brown mass greeted the traveler as they crossed into California and on to Los Angeles. The dream of prosperity and possibility that drives a traveler westward became the hardships of the road and the realities of the place.

For the last decade, Virginia Poundstone has included in her artwork all aspects of floral cultivation. She has climbed the Himalayan mountains to find the wildest of wildflowers, and traveled to the factory farms of Colombia, tracing industrially grown blooms from growth to auction to wholesalers to flower markets and shops. Her interest grew from her day job as a floral arranger and her research into the gendered origins of that craft in the West and its resonance as a mode of art making in Japanese ikebana. She has also curated exhibitions at the Aldrich Museum that included floral works by Christo, Nancy Graves, and Bas Jan Ader (Ader’s video Primary Time [1974], of endless arrangements, is also in A Change of Heart) that have informed her deep investigations into the complex symbolism and language of flowers.

Other artists focus primarily on this language. Willem de Rooij’s Bouquet series (first begun with his late collaborator, Jeroen de Rijke, in 2002) speaks without literal language. Discussions around politics are followed by meditations on color or a collection of blooms gathered for their intensely allergenic qualities. The giant displays, in contrast to Kiwanga’s, are carefully maintained throughout an exhibition; a florist collaborator always makes regular visits to an exhibition to maintain the scent, color, and freshness of the expression.

In A Change of Heart, Sharp also included Camille Henrot’s ikebana interpretations of important modern novels as well as Maria Loboda’s A Guide to Insults and Misanthropy (2006), which attempts to use the symbolic language of flowers to insult their receiver.

Camille Henrot, The Golden Notebook, Doris Lessing, 2014. Courtesy: the artist and Metro Pictures, New York

For flowers, the recent turn holds an echo of romanticism, the intuitive, the emotional, the poetic, existing alongside a belief in political freedoms. The lusty poet Lord Byron died in the war for Greek independence. One of the fundamental human rights is a right to pleasure, to beauty. Beauty isn’t our collective ignoring of the hard struggles of the world, but rather an assertion of exactly what we’re fighting for.

As Fernando Pessoa writes in The Book of Disquiet (1984), “Flowers, if described with phrases that define them in the air of the imagination, will have colours with a durability not found in cellular life. What moves lives. What is said endures.”[3]

[1] http://hannahhoffmangallery.com/media/files/pr_acoh_web.pdf. [2] John Berger, The White Bird (London: Chatto & Windus, 1985) [3] Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet (London: Serpent’s Tale, 1991)

~ BLOOMING ADDENDUM ~

Christopher Williams, Angola, 1989, Blaschka Model 439, 1894, Genus no. 5091, Family, Sterculiaceae Cola acuminate (Beauv.) Schott and Endl., Cola Nut, Goora Nut, 1989, from the series Angola to Vietnam*, 1989. Courtesy: the artist and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne

Orchid / #DA70D6

General Sternwood: The orchids are an excuse for the heat. You like orchids? Marlowe: Not particularly. General Sternwood: Nasty things. That flesh is too much like the flesh of men. Their perfume has a rotten sweetness of corruption… — The Big Sleep (1946)

The shape of this flowering plant’s pendulous doubled root ball suggested to some ancient Hellenic botanist the particular danglers in a man’s kit, and the orchid got its name from the Greek word for testes. Thus the dainty beloveds of aristocratic gardeners and fussy flower breeders are buried balls, dirty nuts. Try not to snicker when granny effuses, “I simply adore orchids.” Flowers have always been symbolic of sexuality, and even more so for those for whom it’s suppressed. Women, especially older ones, have been forced by social norms to stanch their desires, rarely granted the allowance to fuck freely. It gladdens the heart in its own weird way to hear old folks homes have the highest rates of STDs these days. Not because it’s good for anyone to catch the clap, but because it means they fuck with more abandon than most might care to admit.

To some, orchids are the sexiest of flowers. Their namesake roots lie buried in most variants, while those strange blooms pump horticultural hearts with lively colors, generous curves, and lusty orifices. If vaginal decoration took a sharp surgical turn past bejeweled vajazzling, you might find yourself confronted with one of these psychedelic pussies when dipping down for a French lick. As flowers, they fall into an uncanny valley. Too close but not close enough, the effect is just creepy rather than alluring. While other flowers invite an inserted nose, a huff, and though not yet an erection, their floral perfume has turned my head in that general direction. But the fleshy orchid does not inspire my lusts even a little. Perhaps even the opposite—its odor and form the absence of body, a dry, funereal thing.

“Crypt orchid” is the term for an undescended testicle, though I dream a flower that can only blossom in tombs.

The bright, rich purple creeps its name from the flower, one of innumerable possibilities for a plant with wild variation. Though it has the crackle of electricity beneath its buzz, orchid’s too muted to be much beyond a suggestion. Bright but not the brightest, rich without being creamy, orchid’s a faded purple haze on a bright day, the fading neon of a strip club past its prime.

Rose / #FF007F

A rose is a rose is a rose is a rose.

When a beautiful rose dies beauty does not die because it is not really in the rose. — Agnes Martin (1989)

Each five-petal-kiss of colors from the tangled, toothy green stems. A brokenhearted smear, a yearning expressed through the formality of its presentation, the rose’s simple obviousness is its charm. The color of nipple, just exposed before cold air and hot mouths harden it into a deeper shade.

In many languages, the words for “rose” and “pink” are the same.

Rose-colored glasses. Roseate glow.

Rose tints my world Keeps me safe from my trouble and pain. — The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975)

Ask any florist and he’ll know how much a dozen will cost, one extra thrown in for luck. The rose grows thorns to better climb over its neighbors, to push over other flowers hungry for a beam of sunlight. More than one rose has drawn my blood, the dripping finger quickly mouthed.

Rose, floating in the pond, a dead flower in the eddies of the silver surface spangled with light. A lover’s bathtub blanket, a romantic’s bedspread. Rose, a gesture, an empty signifier, a lover’s lament, a husband’s apology. A shapely scented flower, a dream of what pussies could be.

Flowers and fruits are the sex organs of plants. Georgia O’Keeffe knew surely what she was doing with her folded blooms, plumped petals peeled back. Victorian ladies corseted by rigid morality spent repressed hours devotedly fingering their carefully cultivated flowers. Fresh blossoms will wilt on the vine whether they are nabbed or not. Gather ye rosebuds while ye may, you virgins who make much of time. The scientific term for wilted plants starved of nutrients and water is “flaccid.”

A lover once told me she only enjoyed flowers knowing that something was dying expressly for her pleasure. Every rose has its thorn…

Flowers began as a funeral tradition to mask the odor of a decaying corpse. Wreathed, bouqueted, and sprayed, apple blossoms and heliotropes, chrysanthemums and camellias, hyacinths and delphiniums, snapdragons and, of course, roses. Anything goes for funeral flowers, just as long as they are fresh.

One artist I know dreamed of casting in concrete the cast-off flowers at the base of a Soviet war memorial. All the original flowers she stared at for hours, snapping picture after picture, measuring and admiring the perfect war memorial, the waste of pageantry all heaped and rotting, all the showy pomp to be swept up and trashed. Failing to gather them all from a park one Sunday afternoon, she made a memorial to that one. Under marbles carved Pro Patria, sometimes you’ll find flowers, but you’ll be sure to find a corpse.

“Roses,” she thought sardonically, “All trash, m’dear.” — Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway (1925)

As bright blooms fade, what is the color of decay?

Is it a sinking brown, a pale green, a moldy black that captures the wilted flower, the rotten fruit, the decomposing body? Spotted and mottled, both wet and dusty, alive with death’s critters and aromatic with rot, the color is unsteady at best, a hue with a checkered future. Tuck a rose away, let it dry, and though the life goes and the color fades, its form remains.

Ah Little Rose—how easy For such as thee to die! — Emily Dickinson (1858)

I won’t forget to put roses on your grave.

Lilac / #CBA2CB

I lost myself on a cool damp night Gave myself in that misty light Was hypnotized by a strange delight Under a lilac tree I made wine from the lilac tree Put my heart in its recipe It makes me see what I want to see and be what I want to be When I think more than I want to think Do things I never should do I drink much more than I ought to drink Because it brings me back you… Lilac wine is sweet and heady, like my love Lilac wine, I feel unsteady, like my love

Pale purples are the fucking saddest. Lavender’s forgetful wash. Mauve’s lonely decadence. And lilac. The color of unwilling resignation to lost passion. The pale fade, a lost spring.

April is the cruellest month, breeding Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing Memory and desire, stirring Dull roots with spring rain. —T. S. Eliot, The Waste Land (1922)

The lilac flower originated on the Croatian coast whence it found its way into the gardens of Turkish emperors and from there to Europe in the 16th century, not reaching the Americas until the 17th. The scent of lilac has become for many the scent of spring. Carried by the compound indole, which is also found in shit, lilac’s aroma carries with its fade a special decay, heavy and narcotic. To a nose that does not know the tricks of the master perfumer, indole dropped in chocolate and coffee makes a product smell natural.

A note found in perfume, bottled spring, often worn by elderly ladies. In the Descanso Gardens near Los Angeles, there is a grove of two hundred fifty varieties of lilac, their names a horticulturist’s poetry of yearning: Dark Night and Sylvan Beauty, Snow Shower and Spring Parade, Maiden’s Blush and Vesper Song.

I missed their bloom this year, gone to the snowy mountains where the flowers blossom late, but to walk among the towering shrubs is to be punched in the face with perfume. So sweet, so heady. Running my fingers over its heart-shaped leaf, failing to feel my leaf-shaped heart. I dreamed of going to the gardens with my lover and went there many times after she left me. Dreaming of her. Feeling the sweet sadness of her perfume, the unwilling resignation of her love withdrawn. And this lover, all the lovers who always go away. One lilac may hide another and then a lot of lilacs… — Kenneth Koch (1994)

Walt Whitman dropped a sprig on the passing coffin of a murdered president and birthed a poem for dooryards and students. Not his most beautiful by far, but its love is real. As any love for a distant leader can only be so real, but the lilac is love. Staring into a screen full of its color, I am both spring and its destruction. Its bright lovely burst of life, its wilt and loss. The cool kiss of night, naked skin shivers but still you stay. And you stay and drink its sweetness and its rot, you drink your heart.

In the desert I saw a creature, naked, bestial, Who, squatting upon the ground, Held his heart in his hands, And ate of it. I said, “Is it good, friend?” “It is bitter—bitter,” he answered; “But I like it Because it is bitter, And because it is my heart.” — Stephen Crane (1895)

Cherry Blossom / #FFB7C5

A Selection of the Traditional Colors of Japan; or, Bands I Wished I Was In

Cherry Blossom Ibis Wing Long Spring Dawn Orangutan Persimmon Juice Cypress Bark Meat Sparrow Brown Decaying Leaves Pale Incense The Brown of Flattery The Color of an Undried Wall Golden Fallen Leaves Simmered Seaweed Contemplation in a Tea Garden Pale Fallen Leaves Underside of Willow Leaves Sooty Willow Bamboo Thousand-Year-Old Green Insect Screen Rusty Storeroom Velvet Harbor Rat Iron Storage Mousy Wisteria Thin Color Fake Purple Vanishing Red Mouse Half Color Inside of a Bottle

Andrew Berardini is an American writer known for his work as a visual art critic and curator in Los Angeles. He has published articles and essays in publications such as Mousse, Artforum, ArtReview, Art-Agenda.

Originally published on Mousse 55 (October–November 2016)

0 notes